RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

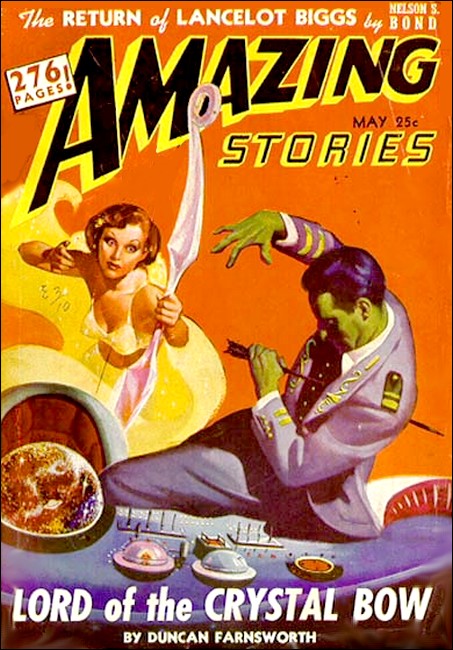

Amazing Stories, May 1942, with "Lord of the Crystal Bow"

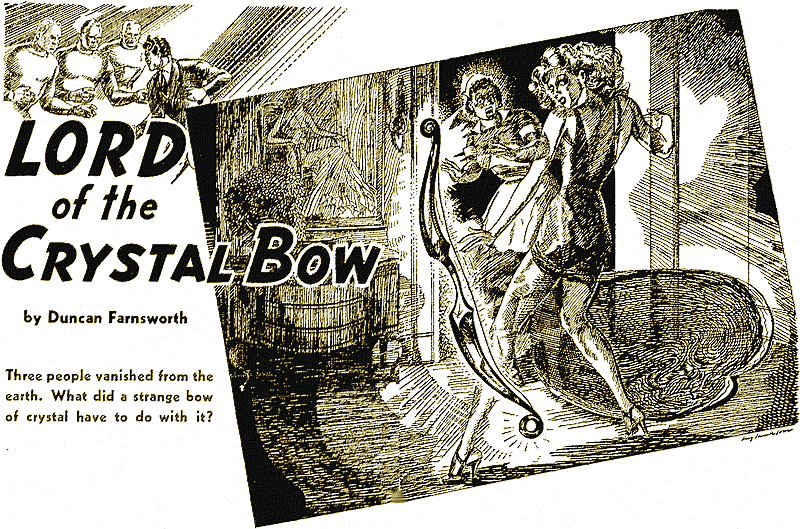

Three people vanished from the earth. What did a strange bow of crystal have to do with it?

Miss Madeline plucked the bow, and vanished right before my very eyes.

IT was close to midnight, and of all the offices of the fifty some floors that comprised the massive, towering structure of the opera building, mine was one of the few whose windows still blinked pinpoints of light out into the black, starless night that shrouded the huge city.

It was still Monday, however, and I had another hour before my copy was due in the offices of the Chicago Blade, where I held the titular position of Music and Dramatic Critic. It was generally this way after a Monday night opening. Frantic, last- minute efforts to knock out a review in time for the third metropolitan edition.

I crushed out another cigarette, stuffed my second page into the typewriter and picked up where I'd left off.

And the scintillating brilliance of Madeline Trudeau's glorious voice was doubly heightened by her unequalled dramatic ability and her striking, dark-haired beauty.

Leaning back in my battered chair, I lighted another cigarette and deliberated for a minute. Rigoletto might have been performed with lovelier voices than Madeline Trudeau's singing the role of Gilda, but never had I seen such a dazzling combination of voice, beauty, and emotional magnificence as tonight's performance by the raven-haired soprano. There was no exaggeration in the lines I'd just written. And my laudatory criticism was totally uninfluenced by the fact that I was very much in love with the little operatic star.

I got back to work. I was to meet Madeline at one o'clock. I didn't want to keep her waiting, even though I was supposed to pick her up at an after-the-opera party on Lakeshore Drive. There would be far too many other eager escorts waiting to step into my place if they got the chance. Madeline's loveliness was never lacking thronged male admiration.

This thought alone was enough to speed my efforts as I went about finishing up my copy. And precisely twenty minutes sooner than I had hoped, I'd finished my review and was stepping out of the opera building and hailing a cab.

When I turned in my copy at the offices of the Blade, Hendrick, my city editor, looked up at me sharply.

"Get any late dope on the disappearance of Frederick Loche?"

I looked at Hendrick bewilderedly. Frederick Loche, veteran in musical and operatic fields, was a well-known composer and the ex-conductor of a symphony orchestra. He was also director of the opera company which had performed Rigoletto less than three hours ago.

"Loche?" I blinked. "Disappeared?" I shook my head. "I hadn't heard a damned thing about it, Hendrick. What's the story?"

Hendrick threw up his hands.

"I'd certainly hate to run a news paper that depended on news from you music critics," he snorted. "You mean to tell me that you were covering tonight's performance and never had an inkling of the story that broke right under your nose?"

"Look," I was getting a little sore at his attitude. "I cover the opera, the music, the voices. That's my job. If an usher happened to stab a contralto on the middle of the stage, I'd see it. But as for covering an opera like a police beat, that's not my line."

Hendrick shrugged.

"Well whether you know about it or not, your pal Fredrick Loche is gone—missing. He was last seen about the middle of the performance. People backstage saw him go out for a breath of air. He never returned."

"Maybe he wasn't feeling too well. Perhaps he went home," I said. "Loche invariably has a case of jitters when it's opening night. He's not so young any more, you know."

"His apartment has been checked," Hendrick said, "and he didn't go there. He didn't even have his hat or coat with him when he left. They're still around."

I began to get a little worried.

"When did they realize he was gone too long?"

"When he didn't come back," Hendrick said with sarcastic patience.

"Perhaps he went right to his apartment, forgetting his hat and coat, picked up a coat there, and left again," I suggested.

"Don't ever," Hendrick said disgustedly, "try to get a job as a police reporter on this sheet, Lannister, you're too naive. Everything was checked, including the fact that he didn't return to his apartment since he left for the opera tonight at seven."

"Anyone see him when he stepped outside for some air?"

Hendrick nodded affirmatively.

"One of the property men. He saw a uniformed messenger come up to Loche when he was about ten yards away from the stage door and hand him a long package. He says Loche seemed surprised, and that the messenger beat it immediately."

"What happened then?" I asked.

"The property man had to get back in for a scene change. He didn't see anything after that."

I was worried more than before, now. But there was still the chance that Hendrick, ever seeking to blow up an incident into a five-hour headline, was making too much of this purported disappearance of Frederick Loche. But the old man was one of my closest friends. I owed him a lot. It was he who got me my first musical reporting job. And if there was anything to Hendrick's suspicions, I wanted to find out.

"Why don't you see what you can pick up on the story?" Hendrick asked. "You knew the old guy pretty well, didn't you?" He must have been reading my mind.

"That's just what I intend to do," I declared. I turned and started away.

"Give us a ring the minute you learn anything," Hendrick shouted after me. "Anything at all, understand?"

I CAUGHT a cab outside the office of the Blade. It

was just a five-minute ride over to the Lakeshore Drive apartment

where the after-opera party was being held, and where Madeline

would be waiting for me, surrounded, I strongly suspected, by a

convoy of admiring males.

I suppose I might have worried more about Fredrick Loche's supposed disappearance, if I hadn't been more than half-convinced that Hendrick, stuck for local news, was merely hoping to make a few columns to carry until the home editions came out. I had noticed that he hadn't played up the Loche disappearance in any of the first metropolitan editions as yet. He was too smart an editor to stick his neck out on the block unless it had been absolutely established that the old director had disappeared. Hendrick was just building a hunch around the circumstances which must have come to his attention by a semi-frantic tipoff from a reporter who'd been backstage when Loche turned missing.

But I knew Loche well enough to realize that a situation such as this, to him, was not particularly unusual. If he hadn't been the brilliant genius that he was, people would have tagged him as eccentric long ago. He really wasn't eccentric, however. His habits, like his great mind, differed vastly from the ordinary human pattern.

A butler let me into the twelve room suite on the Drive where a wealthy patron of the opera—I can't recall his name now—was entertaining for as varied a group of guests as you could imagine.

There was wealth there, much of it stuffy and dull, some of it clever. There was also talent, and charm, and intelligence gathered in that array. Champagne was being served by stripe- shirted caterers, and I'd no sooner removed my coat than I was taking a glass from a broad silver tray.

Several people had already nodded to me, smilingly calling my name, but I answered with the briefest of greetings, moving through the confusion of cigarette smoke, conversation, and laughter toward the largest drawing room of the place.

I caught sight of a group of black dinner jackets, formed in a circle almost two deep, and grinned to myself. Madeline was in the center of that circle, I wagered mentally.

She was. And it was several minutes before I could get her off by herself out onto the glass-enclosed terrace of the swank apartment.

"Finally," I said at last, taking her tiny hands in mine, "I can talk to the great soprano alone."

Madeline laughed, and it was like tinkling music, beautiful music. She was wearing a silvered gown that set off her raven- haired five feet and one inch of incredible loveliness like a lustrous jewel.

"Did you like me tonight, Tommy?" she asked.

Madeline's question was what you could expect from any star to a critic, and yet there was something else in her voice. Something honest and open and sincere.

I grinned, shaking my head from side to side.

"You'd never believe me," I said. "Read my review tomorrow. But," I added, "I'll apologize here and now for suddenly finding myself woefully short of adjectives. I didn't use enough of them. Few critics could have."

Madeline took her hands from mine and squeezed my arm lightly.

"You say wonderful things sometimes, Tommy. Aren't you afraid they'll go to my head eventually?"

I shook my head.

"I have an antidote if they ever do."

"What's that?" Madeline demanded.

"I'll marry you," I grinned. "No woman could ever remain conceited with a lout like Tom Lannister for a husband."

"You aren't as bad as all that," Madeline protested in mock horror. Then, expression jokingly judicial, she stepped back a pace.

"You have nice eyes," Madeline decided, putting a finger to her chin and pursuing her lovely red lips contemplatively. "They're gray, and clean, and somehow a person knows that their owner will be decent and honest."

"Thank you," I made a half-bow, like a symphony conductor.

"You're rather short, however," she went on.

"Five feet eight inches," I broke in. "And what right have you, my celebrated soprano, to speak of lack of height?"

"But you're sturdy," Madeline resumed the game. "Your shoulders are wide, and your hands are strong, and you walk with the assurance of a trained athlete."

"How flattering," I laughed. "This is fine, go right on. My college coach would be pleased to know he made a man of me."

Madeline shook her head. She sighed.

"Ahhh," she added in mock despair, "but look what football did to your features."

"Quarterbacks," I sighed ruefully, "always get the worst of the beating. Go ahead, I can take it."

"Your brows," she said, "are just a trifle beetled, bumpy. It's a wonder all those kicks on the head didn't jar your brain."

I made a gibbering face.

"Sometimes I think they did, haw!"

"I agree with that diagnosis sometimes myself," she went on. "But I can't ignore your nose. Adonis would never have lasted a minute with a nose like that."

"Adonis," I reminded her, "never tried to bring down Nagurski in an open field."

"But it isn't so bad," Madeline decided. "Just a trifle flattened at the bridge. And anyway your smile is nice. It's so white and even I'm sure you see your dentist three times a year instead of two."

"And now that I've been taken apart and put back together again," I declared, "what about you?"

"I am a small girl with a big salary and black hair," Madeline said quickly, "plus a terrible craving at the moment for a glass of champagne. Anything else you might add would never be believed."

I sighed disappointedly.

"Very well, discourage me just because I'm not tall and handsome."

"I despise handsome men," Madeline said. "They're all so dull."

"That's something in my favor then," I said. "And just for those kind words, spoken generally, I'll take your hint about the thirst for champagne and scout up a couple of drinks."

Madeline made a mock curtsy.

"Mistah Lannister, suh, youah sooo gallaant!"

"Just call me Rhett," I answered. "You know, Rhett Butler. Then I'll be gone with the wind."

"Offfoo!" Madeline made a face of sharp pain. "That was quite terrible. If there's one thing worse than a pun, it's a bad pun. Run for those drinks before I throw something!"

AS much as I hated to leave Madeline for even an instant,

I found myself threading my way through the crowded drawing room

toward the bar a minute later. Of course it took a little time.

Things always take time when you're in a hurry. People had things

to chat about as I passed, and other people wanted to shake

hands. And when I finally reached the bar, it was just in time to

see Geno Marelli, the very temperamental and exceedingly famous

tenor, staggering drunkenly away from it.

I don't think he recognized me. He was muttering thickly under his breath, and his heavy, almost purple marceled hair was tumbled down over his forehead. His handsome, swarthy features were a mask of rage.

I called for a couple of champagnes, and stood there watching Marelli's back disappear amid the groups in the drawing room. Vaguely, I wondered what was eating him. His performance that night in Rigoletto had been dashingly brilliant—a fact which I hadn't omitted in my review—and so superbly done that I suspected he was definitely trying to outdo Madeline's magnificent work. Certainly he couldn't have been disgruntled over anything concerned with his work.

One of the musicians in the opera orchestra tapped me on the shoulder. His name was Bostwick—a round, dumpy, bald little man—and I'd known him several years.

"You'd better watch it, Lannister," he grinned. "The World's Greatest Tenor is muttering about getting your scalp."

"Geno Marelli?" I blinked in surprise.

Bostwick nodded.

"No less. The Great Voice seemed jealous of the fact that you were out on the veranda with Madeline. And he was also mumbling something about 'having it out' with Frederick Loche."

This time I looked at Bostwick sharply.

"What about Loche?" I demanded. "Has anyone located him since he left the opera house tonight?"

"Not yet. He's probably down on the lower level of the Michigan Avenue bridge, looking at the Chicago river wend by. Tricks like that aren't unusual for the old man."

I frowned.

"I suppose you're right," I said. "I hope so."

"I think Marelli was headed for the veranda," Bostwick said. "Maybe you'd better get back to Madeline. When Geno is nasty, he's poisonous."

I picked up the glasses of champagne.

"You're right," I nodded. "Thanks."

IT didn't bother me that a lot of the champagne spilled

over the edges of the glasses as I hurried back through the

crowded drawing room.

And when I stepped out onto the veranda it was deserted save for two people locked in furious embrace.

Those two people were Madeline Trudeau and Geno Marelli!

I dropped the glasses I held in either hand. Dropped the glasses and took three swift steps in their direction. Then I was yanking hard on Marelli's shoulder with my right hand, and swinging him around into a smashing hook delivered with my left. I put every last ounce of weight and sinew into that punch.

Marelli caught it flush on the chin.

I stood back, watching him drop like a newsreel run slow motion. He slid to his face on the veranda flagstones, directly between Madeline and me.

Madeline's face was white, terrified. Her mouth was half open as if she'd been trying to scream and no sounds came. The shoulder strap on her gown was half torn. And the marks of Marelli's paws on her white shoulders had left red marks.

She was breathing in quick gasps.

"You shouldn't have done that, Tommy," she said. "You should never have done that. He'll kill you for it. He's killed other men before, and now he'll kill you!"

I looked at her in astonishment. Her voice was low, husky, shaking with terror.

IT was noon when I woke up the following morning in my bachelor apartment at the club. I wouldn't have wakened if it hadn't been for the constant ringing of my telephone beside the bed.

When I picked the instrument out of the cradle my vision and senses were still blurred from sleep. But the voice on the other end of the wire snapped me out of my fog immediately.

"Lannister!" it barked. "What in the hell have you been doing, eating opium?"

It belonged to Hendrick, that voice. Hendrick, my city editor.

"What's up?" I growled. "I'm in no mood for wise cracks."

"I don't suppose you've seen the extra editions of the Blade," he said. Hendrick would be lost without sarcasm.

"I went to bed at five. I never read the papers until I get up."

"Fredrick Loche has disappeared," Hendrick said. His voice underlined the "has."

"Are you certain?" I demanded. "Sometimes he roams for a day or so."

"I'm certain," Hendrick snapped. "So certain I want you to get right over to the apartment of Geno Marelli, the temperamental tenor, and accuse him of Loche's murder."

"My God," I gasped, sinking back weakly on the pillow. "Now who's been eating opium!" Then I said, "You're out of your mind. Have you found a body?"

"No," Hendrick began, "but—"

"Have the police found Loche's body?"

"Of course not," Hendrick snapped. "I'm playing a hunch. Loche has disappeared. I've reason to believe he's been murdered. He and Marelli had a terrific verbal tangle backstage before the curtain went up on the opera opening last night. Marelli threatened in front of five people to cut Loche's heart out. Now Loche can't be found."

"And so I'm supposed to trot over to Marelli's and accuse him of murdering Loche and doing away with the body, eh?"

Hendrick's voice came back excitedly.

"That's it. Good God, Lannister—don't you see what a helluva headline we'll have if we scoop everyone including the cops on that?"

"Sure," I said, "I can see the headline. Killer of director stabs music critic to death when confronted with guilt. Exclusive story in the Blade. Read all about it. Two cents a copy. Go to hell!"

I slammed down the receiver and lay back.

THE telephone was jangling again in another minute. I

picked it up.

The voice squawking on the other end might have been an enraged Donald Duck, or it might have been my city editor Hendrick. Reason led me to assume it was the latter.

"When you finish ranting," I said calmly, "I'll be able to understand you."

Hendrick became intelligible. Hang up on him, would I? I was a lousy, blank, blank so-and-so, and my ancestry was lurid and rife with scarlet shame. Who did I think was paying me more than I was worth every week? Did I forget that I wasn't just working for the managing editor, and that the city editor could also give me orders which I'd damned well better follow out—or else?

A job was a job.

"All right," I said, when Hendrick was running the length of the field again. "All right. I'll bare my throat to his damned stiletto. I'll call you back as soon as I've seen him. I'll give you his reactions. But if he pulls a knife, or a gun, or even bites me in the ankle, I get a two-hundred dollar bonus, understand?"

"Listen," Hendrick screeched. "I got a nephew just outta high school. He can play a piano and write fairly intelligible English. He'd love your job as music critic."

"All right," I said. "All right. You can skip the bonus if that's the way you feel about it." I paused. "But about this talented nephew of yours," I added, "if he wants my job there's one other qualification he'll have to have."

"What's that?" Hendrick demanded.

"He'll have to be able to take orders from a screw-loose moron," I said. Then I hung up.

MOST of the opera celebrities were staying at the

swankiest Loop hotels. But Geno Marelli preferred to live apart,

and was quartered in a modest ten-room suite in the ritziest

hotel on the north side of town.

I gave the cabbie the address of that hotel, when I caught a yellow just outside the door of my club. I'd picked up a copy of the Blade from the desk in the lobby on my way out, and now I settled back to scan Hendrick's lurid suppositions about the Fredrick Loche disappearance last night.

It yelped about a lot, with two-column cuts of Loche, Madeline, and other stars of the old man's opera company. It yelped about a lot, but it didn't say much. Hendrick had put out his neck, but not awfully far. He was no dummy, even if he did love to play hunches. The story made sensational reading, but when you put the paper down you couldn't remember exactly what it said. One of those yarns.

I gave my attention to the passing scenery on the Outer Drive. The morning was cold, but bright and sunny and brisk. An exhilarating morning, or I should say an exhilarating early afternoon, for it was about a quarter to one by now.

We pulled up in front of the north side hotel at exactly one.

I got Marelli's room number at the desk, and three minutes later I was pressing the buzzer at the door to his apartment. After what must have been about thirty seconds, the door opened and a head peered out. A swarthy, Latin-looking head.

"Is Geno Marelli in?" I asked.

The brown eyes in the Latin head regarded me dubiously. Then the fat lips moved.

"I am sorry, sir. Senor Marelli seems to have left the suite in my absence. He was not here when I returned. Do you wish to leave your name?"

I shook my head.

"Never mind," I declared.

The door closed and I went back to the middle of the hall and pressed the elevator button. On the way down, since the elevator was deserted, I asked the boy a question.

"Did the opera singer, Geno Marelli, leave his apartment yet?" I don't know what prompted me to ask that.

The elevator boy shook his head.

"Not by this elevator, sir."

There were three other elevators, and when I stepped out into the hotel lobby again, I waited around until each of them came down. None of the elevator boys had taken Marelli downstairs. His suite was on the fifteenth floor. It was unlikely that he'd walked. Marelli was a lazy lout and he'd sooner have jumped.

I stepped into another elevator and went back up to Marelli's apartment again. This time when I pressed the buzzer and the Latin head stuck itself out of the door again, I pushed hard against it and found myself standing inside Marelli's apartment, confronting a spluttering valet who was babbling excitedly and indignantly in Italian.

"Are you going to get your boss out of bed and tell him he has a visitor, or am I going to wake him?" I demanded loudly, flicking a hand at my coat lapel.

OF course I had no badge under my lapel, but the gesture

was so swift and significant that Marelli's valet seemed to get

the idea I'd wanted him to.

"But Senor officer," he protested, "my master is not here—I swear it!"

I pushed past him, walking swiftly through the luxurious rooms. It took me four minutes to convince myself that the valet was telling the truth. Marelli wasn't around.

Then I went back to the living room. The valet had followed me, muttering bewilderedly in his native tongue. I turned on him.

"When you left, was he still here?"

The valet nodded excitedly.

"Yes, Senor officer. That was perhaps twenty, twenty-five minutes ago. I have been back only ten minutes."

"Then, at the most, you were only gone fifteen minutes, eh?"

The valet nodded.

"Yes, Senor."

I frowned.

"And he was here when you left?"

"Yes, Senor. He was sound asleep. He was feeling ill. He came in about four o'clock this morning. His eye was badly bruised and his jaw was swollen."

I hid a grin, rubbing the fist that had done that neat little job. Then the significance of what the valet had said hit me.

"You said he was asleep when you left?" I demanded.

"Yes, Senor. Soundly. It seemed strange to find him gone when I returned. He was never one to leave without breaking fast. In addition to that, his morning toilet generally consumed half an hour while he selected the apparel he would wear that day."

That sounded like Geno Marelli, all right. And it made everything increasingly puzzling.

I went back to Marelli's bedroom. The valet was following.

"Look through his closets and see if any of his wardrobe has been removed."

This took the valet several minutes. Then he shook his head bewilderedly.

"No, Senor. Nothing has been removed."

"Then he walked out in his purple pajamas," I said. "How very interesting."

I WENT to the rear of the apartment, opened the kitchen

door that led out into a back hallway. There was a freight

elevator door in the middle of the hallway. I pressed the button

on it. A janitor in blue coveralls opened the doors and looked

out at me when the elevator came up to our floor.

"Taking something down?" he asked.

I shook my head.

"You been operating this elevator all morning?"

He nodded affirmatively.

"Take any passengers down in it from this floor?"

He thought a minute.

"One," he said.

"Who?"

He shook his head.

"How should I know. He was just a messenger. He brought a long package up to this floor, told me to wait, rang the back doorbell, and give the package to Mr. Marelli, the opera fella. Marelli closed the door and went back inside. I remember he was sleepy and cross and in his pajamas. He looked like he'd been in a fight somewhere the night before. The messenger got back in the elevator and left. That's all.

"Say," and his voice took on a high querulous, suspicion, "why do you wanta know?"

"I'm running a contest," I said. "Put what you just said in fifty words, send it in to us with the top of your elevator, and who knows but what you'll be the winner of a thousand dollars a year for the rest of your life."

I went back into Marelli's apartment. The valet was still trailing wonderingly behind me.

I stood there in the kitchen, thinking out loud.

"A long package," I said. "And now he disappeared. Gone right in broad daylight. Lovely." I was frowning.

The valet disappeared and returned a moment later.

"There is no trace of such a package in the apartment, Senor," he said.

I snapped my fingers. I had one of those flashes of inspiration that are usually pictured in newspaper comics by a light bulb bursting above a character's head.

"That's it," I muttered. "Of course that's it! Loche was seen taking a package—a long package—from a messenger. Then, in the middle of a city of four million people he disappears completely. Both disappearances are positively alike!"

The valet looked at me uncomprehendingly.

"Where's the telephone?" I asked him. "I got a call to make!"

HENDRICKS sat still in his editorial throne long enough to listen to the entire story. This time I told him everything I knew—not all of it for print—including the fact that I'd bopped Marelli in the face the previous evening when I'd caught him making wild advances at Madeline.

"Well I'll be—" Hendricks exclaimed. "It's a cinch that those two disappearances are alike. Unless," and he slapped his palm down hard on the desk to emphasize his doubt, "Marelli really did away with Loche, and then got his own hide out of the way by faking this coincidental disappearance."

"I thought you said you'd checked Marelli's actions from seven o'clock until four a.m.," I said. "His time is accounted for straight through those hours, without a break. He couldn't have had the chance to remove Loche, let alone hide him."

"An accomplice, or two of them, couldda done the job for Marelli," Hendrick said. "That's easy enough. But even so, I've a new theory on this. And the new theory is that the two of them were spirited away and slain, or vice versa."

"Because they've disappeared," I said, "you got to make them dead." I shook my head despairingly. "You haven't a single fact to show that either one of them is dead. Take it easy on that angle. Let it go that they've disappeared until you're able to prove the rest of your theory."

"The trouble with you," Hendrick declared sympathetically, "is that you've got no imagination. You'll never be an honest-to-God newspaperman."

"Like you?" I asked.

"Like me."

"Thank God for that," I said. I left then, to get back to the club for a spot of lunch and perhaps a short nap. It was while I ate my lunch that I went over the scene that had occurred on the veranda of the Lakeshore Drive apartment the night before. In the light of Marelli's addition to this growing enigma, what happened there might have been important.

Hell, after those two disappearances, anything that happened might be important.

I recalled that after I'd slugged Marelli, he'd been unobtrusively removed from the scene to a bedroom where he came to and received treatment for his eye. At Madeline's request, I'd taken her home right after that.

My efforts to find out what she'd been so horribly afraid of when I'd knocked Marelli cold were unavailing. She wouldn't talk about it, and nothing I could say would persuade her to do so. She was stubborn, yet trying to get me to understand that she'd let me know whenever she felt it was safe to do so.

Even the warmth we'd shared during the brief period together on the veranda, seemed to have vanished in that cab ride to her apartment. I had the feeling that she was keeping me away from her mentally. Not as if she wanted to do so, but more as if she felt she had to—as funny as it sounds—for my sake.

And of course I recalled her words: "He's killed other men before, and now he'll kill you!"

THAT was incredibly strange. Aside from a more or less

vague and mutual dislike for one another, Geno Marelli and I were

scarcely more than acquaintances. Why should he want to kill

me?

A punch in the jaw didn't seem to be motivation enough. His hot Latin blood, in a moment of drunken jealousy, might motivate him to knife a rival for Madeline's affections. But the cold light of reason would keep him from doing such a senseless thing once the rage flashed past him.

It was definitely a tough nut to crack. No matter how I went at it, there seemed to be no tip-of-the-fingers solution. I gave it up, then, resolving to get in touch with Madeline before the second performance at the opera this evening.

This last thought made me realize, in a flash, that if Geno Marelli wasn't found before evening, there'd be another tenor in the leading role. I'd never thought of it that way before.

But thinking of it from that angle produced no more than any other approach. So I left the remains of my luncheon no further ahead in the snarl. I decided to go upstairs for a quick nap.

Which proved to be a good idea, for when I entered my apartment the telephone was ringing. Hendrick was on the other end of the wire.

"Look," he said when I picked up the receiver, "I'm calling you about this because you know more about the opera crowd, the singers and all, than any man on our staff—but not because I value your opinion."

"I wish you'd let a man sleep. Just because you don't value his opinion is no reason to drive him to insomnia," I snapped. "What's up now?"

"There's an old maid in Marelli's hotel," Hendrick said, "who occupies an apartment across from him. She used to watch through her window, since he's been in town, for glimpses of him moving around the apartment. She's got a case of hero worship for all singers, especially handsome ones, I guess. Anyway, one of our smart reporters got into Marelli's apartment, saw that it faced one other apartment in the entire hotel, and took a chance that someone in the other apartment had been looking in on Marelli about the time he disappeared, see?"

"It sounds terribly involved," I yawned.

"Our reporter talks to this old maid, and she admits that she was just glancing casually across at his window—undoubtedly she was actually peeking—when she saw him in his blue pajamas about the time he disappeared."

This got a little more interesting.

"Go on," I said.

"Evidently Marelli had just gotten outta bed. He was rubbing his eyes and swaying a little as he walked through the drawing room—that's the room the old maid can see—and headed for the kitchen."

"To answer the back bell," I broke in excitedly. "Go ahead."

"WELL," Hendrick's voice resumed, "that must have been it.

For he came back into the drawing room carrying a long package.

He was opening it, tearing the wrapping away, while the old maid

across from his apartment looked on." Hendrick's voice poised

dramatically. "Guess what he pulled out of the package."

"Three complimentary tickets to the Mudville Choir Practice?" I asked.

"Smart guy, huh?" Hendrick snorted. "He pulled out a long bow, sort of a crystal bow."

"A bow?"

"Yeah, like the Indians used to use," Hendrick said. "You know, bow-and-arrow."

"Arrows, too?"

"No, just a bow. This funny looking crystal-like bow," Hendrick said impatiently. "Now here's what I want to ask you, was Marelli interested in archery or anything like that?"

"No," I said.

"Did he collect strange weapons?"

"Not to my knowledge," I answered. "Unless you can call blondes weapons."

"That's what I thought," Hendrick's voice declared. "The old maid told our reporter that Marelli was looking at it in complete astonishment. Then he shrugged, puzzledly, sort of, and turned and walked back to the bedroom, slowly, turning the bow around in his hands as if he was trying to figure out what he was supposed to do with the damned thing."

Hendrick's voice had stopped talking.

"And then what?" I asked.

"Then he was in his bedroom and she couldn't see him any more," Hendrick said.

"That's a helluva note," I exclaimed. "He must have disappeared minutes after that. A crystal bow, eh? Have you seen it yet?"

"Seen it?" Hendrick's voice was disgusted. "It wasn't around the apartment anywhere. You didn't see it around when you were there, did you?"

"No," I admitted. "No, I didn't."

"If those two long packages that Marelli and Loche both received were identical, then Loche probably got a bow too," Hendrick said.

"Yes," I said sarcastically, "the chances are very strong, especially if they were, as you say, identical."

"So he wasn't interested in archery?" Hendrick asked again.

"No," I told him once more.

"Was Loche?"

"I could say almost positively that Loche wasn't either," I answered.

"Then it was probably unexpected and unfamiliar to Loche, too," Hendrick said.

"If it was a crystal bow that he got, yes," I agreed. "But supposing it wasn't."

"It was a bow, all right," Hendrick said, "and probably a crystal one. I just got a hunch."

"Just so long as your hunches don't keep me awake," I said, "it's all right with me."

"I'll wake you up again if it's necessary," Hendrick snapped.

"You didn't wake me up," I said. "I'm just getting down to sleep. Now I lay me—" I began lazily.

Hendrick said a nasty word, almost knocking my eardrum loose with the noise he made hanging up. I put the receiver into the cradle and sat down on the edge of my bed.

SOMETHING new had been added—a crystal bow.

And instead of serving to clarify the mystery, it had only filled in as an additionally tangling knot. For five or ten minutes I sat there on the edge of my bed, trying to turn back through the pages of my mind in an effort to recall anything pertaining to a crystal bow.

If there was anything there I was too tired to think of it. Finally I realized that a fresh brain could tackle the problem a little bit more successfully. And a nap would freshen my brain. I sank back, and was putting my head to the pillow with deep and luxurious satisfaction.

Brrrrriiiinnnnggg!

It was the damned telephone again. I clenched my teeth and tried to shut out the sound with my pillow. To hell with it. Let it ring itself out.

Brrrrriiiinnnnggg!

Hendrick, no doubt, with something inane to ask me. Probably the next thing he'd be asking was what I knew about the Indian Rope Trick. Let him look in the encyclopedia.

Brrrrriiiinnnnggg!

It was no go. My nerves weren't strong enough to stand a battle with that telephone. And even if my nerves held out for a short spell, my curiosity was bound to win out.

I took the receiver off the cradle.

"Hello, Tommy," said the voice on the other end of the wire. "I didn't rouse you from a sound sleep, did I?"

I didn't have to ask who was speaking. Madeline Trudeau was the only girl I knew who spoke like silver, tinkling bells.

"Madeline!" I didn't try to hide the surprised elation in my voice.

"I just wanted to thank you for what you did last night, Tommy," she said. "I know I must have acted strangely to you, and I'm sorry I was such a chatter-knees. I don't know what ever made me say what I did when you pried Geno away from me."

This was daylight. What had happened was done. Madeline had time to think it over, and now she wanted me to forget it all, just like that. But the terror that had been in her eyes and voice hadn't been synthetic. It had been hard, real. Listening to the bells tinkle in her voice now, however, it was hard to keep that in mind. She was the Madeline I'd talked to on the veranda before I went for the champagne.

"That's all right," I said. "And about the rescue scene, don't mention it. Any of the Rover Boys could have come through as nobly in the pinch as I did."

Madeline laughed. Maybe it was only my imagination that led me to believe that laugh wasn't as natural, as genuine, as it might have been.

"Seen the papers yet, Madeline?"

THERE was a silence. She knew I meant the Fredrick Loche

disappearance yarn in the Blade. Her voice was casual, too

casual, when she answered.

"It's not true, is it, Tommy?"

"The suppositions, you mean?" I asked.

"Yes."

"No, I don't believe they're true. Hendrick, the city editor, draws heavily on his imagination in such stories. I'm pretty sure Loche is off somewhere, looking at paintings in an obscure gallery, or sunning himself conspicuously on the lawn of Lincoln Park. He's done things like that before."

"Yes, that's true. I'm glad to hear you think that, Tommy," Madeline said. She seemed vastly relieved, in spite of the casual reference to it at the start. Of course there were a lot of reasons why she might be vastly relieved. The first was that few people who were connected with music or opera didn't know and love old Fredrick Loche.

I was wondering if it would be smart to mention anything about the Marelli disappearance, or anything about the increasingly snarled mystery that was piling up.

"Just a moment, Tommy," Madeline said. "There's someone at the apartment door making an awful racket with the buzzer. The maid is out and I'll have to answer it." Her voice faded away.

I sat there waiting, still wondering if I should mention the Marelli mess. Perhaps a minute passed. Then her voice came through to me.

"Strange thing," she said conversationally. "That was a messenger delivering a long package addressed to me. I haven't opened it yet, but I'm terribly curious to see what's in it!"

TIME hung motionless as the significance of Madeline's words hit me.

Then a thousand wild premonitions raced crazily around in my mind. A long package. Loche and Marelli had both received packages of the same description before they'd mysteriously vanished. And now Madeline. This could be coincidence, of course, sheer coincidence. But there was an ominous hunch crawling along my spine. Too ominous.

"Madeline!" I barked. "For God's sake listen to me carefully, Madeline!"

I heard her gasp in surprise, start to say something. I cut in on her swiftly.

"That package you just received," I began.

There was a sudden click and a buzzing static in my ear. It was as if someone had cut in on the wire.

"Hello!" I shouted. "Madeline—do you hear me?"

A voice came lazily into my ear.

"So sorry, sir. I'm afraid I cut you off accidentally."

It was the voice of the switchboard operator in the lobby. I cursed steadily while I heard her fiddling with plugs and switches. Moments trickled by. Sweat stood out on my forehead. The switchboard operator's voice came in lazily once more. She spoke through a mouth full of chewing gum.

"What was the number you were calling, Mr. Lannister?"

I started to tell her. She cut me off again.

"That's right, sir. I almost forgot. The call was an incoming one. If you just hang up, I'm certain your party will call back in a minute or so."

I scorched the wires with my reply, concluding: "And damn your vacant little blonde bean, get that number in a hurry!"

The operator's voice was pained.

"Yes, Mr. Lannister. After all, Mr. Lannister, mistakes—"

"Get that number!" I blazed.

I heard the connections being made again. Then there was a buzzing, loud, sharp, evenly spaced.

The operator's voice broke in again.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Lannister. Your party seems to have a busy wire at the moment."

I slammed the telephone back into the cradle, cursing. In the interim between the time the fuzzy-headed, red-lipped, gum- chewing moron at the switchboard had messed up the connections in my talk with Madeline, someone else had probably called that apartment.

I stood up, lighting a cigarette. Madeline's apartment was about ten minutes by cab from the club. I had no idea of how long she'd be on the telephone with whoever had called her just now.

Grabbing my coat, I made for the door.

TWO minutes later the club doorman was hailing a cab for

me. And when I jumped inside I barked Madeline's address to the

driver. He threw the car into gear and I leaned forward anxiously

shouting:

"Make it in five minutes and it'll be worth your while!"

The cabbie nodded, and immediately jammed hard on the accelerator. We whipped around a narrow corner and shot for Michigan Boulevard just in time to beat a red light. Madeline's apartment was on the south end of the Loop. And the cabbie handled his hack like a halfback swivel-hipping through a broken field toward a touchdown. He was in and out of traffic snarls like an elusive ghost. But we made time.

In exactly four minutes after we'd pulled away from the curb at my club, the taxi rolled in front of the Michigan Boulevard hotel at which Madeline was staying.

I threw the driver a five-dollar bill and rushed past the startled doorman into the lobby of the place. There was an elevator line at the other side of the lobby, and the operator was just about to shut the doors before going up.

My bellowed "Hold it!" must have startled the operator and all the sedate residents of the hostelry in the lobby out of many years growth. But he held it.

There were three floor stops made before Madeline's floor number was reached. And during the interval it took to make those stops and discharge passengers—scant seconds though each one was—I died a million deaths of anxiety and frantic impatience. But at last I was out of the elevator and dashing down the twenty-fifth floor hallway toward Madeline's suite.

I pushed hard on the buzzer of her door with one hand and knocked loudly and insistently with the other.

The door was opened almost immediately. Opened by the fat person of Frieda, Madeline's South African, coffee-colored personal maid.

Her face, through all that coffee-color tan, was ghastly white. Her thick lips were twitching, and her usual cheerful smile of greeting was replaced by a grimace of sheer terror. Her big brown eyes were wide and filled with horror and unmistakable hysteria.

"Mister Lannister!" she gasped. "Mister Lannister, oh I am glad, so glad, you are here!"

"Frieda," I blurted, moving past her into the apartment, "where is Miss Madeline?"

I was in the drawing room by now, looking frantically around. And two things were immediately apparent. Madeline was not there, and on the center of the living room floor there lay, amid several sheets of brown wrapping paper, a bow of curious crystal composition!

"Madeline!" I shouted, fighting off the ominous terror that assailed me. "Madeline—where are you?"

FRIEDA came up behind me. Now she was sobbing

uncontrollably. I wheeled to face her, placing my hand on her

shoulder in a gesture that was meant to steady her.

"Frieda," I demanded. "Frieda, for the love of God, tell me where your mistress is!"

Frieda made choking noises that should have been words. She was trying desperately to say something, but she was reverting to a mixture of South African that was unintelligible.

"Frieda!" I shouted, "for God's sake, tell me what this is all about!"

Her eyes rolled, glazed, then closed. She toppled toward me in a dead faint. I caught her as she fell, lifting her in my arms and carrying her over to a chair, cursing as I did so.

I left Frieda propped there in the chair and swiftly started through the other rooms in the house. There was no sign of Madeline in any of them. In the bathroom I ransacked the medicine cabinets, got a bottle of ammonia, a cold towel, and returned quickly to the drawing room.

It took several minutes to bring Frieda back to consciousness, and another two minutes before she was able to say anything. Her eyes fell on the curious crystal bow still lying in the center of the room, and she shuddered involuntarily.

"Where is Miss Madeline?" I demanded again. "What has happened?"

"She is gone," Frieda said faintly. "I saw her go."

"Where?" I demanded. "Where has she gone?"

Frieda began to shudder again, and her eyes grew wider, fixing themselves in horrified fascination at the crystal bow lying on the thick red rug.

"Where, Frieda?" I repeated. "Where has she gone?"

"The Lord would know," she shuddered, "I do not."

"But you said you saw her go!" I insisted. "For God's sake, girl, speak up!"

Frieda suddenly seemed to go into a trance. She said nothing, merely continued to stare in hypnotic fascination at the crystal bow. I shook her shoulder gently.

"Tell me what happened," I begged, "right from the beginning."

This seemed to be a better approach. It was as if she were able to talk of anything that was not immediately related to that crystal bow and whatever had happened to Madeline.

"I was out, Mr. Lannister," she whispered huskily. "I had just gone to make arrangements with her hairdresser. A matter of minutes, you understand, I was away."

She hesitated again for an instant.

"Go on," I demanded.

"When I was coming down the hallway, after just stepping from the elevator, I saw a messenger turning away from the door of the suite. I do not notice him as he passes me. I was just concerned that I was not there to receive whatever package he left."

Again a pause, and again the terrified glance at the crystal bow lying ominously on the rich red rug.

THIS time I didn't have to prompt her to go on, however,

for she hesitated only a moment before resuming.

"When I was entering the apartment, coming through the drawing room, Madeline was just leaving the telephone. She smiled at me and asked for what time I have arranged her appointment with the hairdresser. She added that she had just been talking to you and that the connection was somehow interrupted. She said she expected that you will call back, Mr. Lannister, and would I please notify her when you do so."

Frieda paused again, this time keeping her eyes from the crystal bow. When she resumed, she seemed to be fighting for self control.

"Madeline then went into the drawing room where she had left the recently delivered package. I was in another room, and I could hear the sounds of paper wrappings being torn away as she opened it. My curiosity is strong, of course, Mr. Lannister, and I was about to enter the drawing room when the telephone rang. I went to answer it. The person on the other end of the wire said he was a reporter from a newspaper, that he had some questions he would like to ask Miss Madeline and would I call her to the telephone. I told him to wait, and put the telephone to the side while I went to the drawing room to inform my mistress that there was a call waiting."

The pause in the narrative of Frieda was longer now, and her fight against the impending terror in it was more difficult. There was nothing I could do but wait, while she closed her eyes and squeezed her nails hard into the flesh of her palms while her thick lips went flat against her white teeth.

"She was standing there in the drawing room," Frieda said huskily now. "The package she had already unwrapped. In her hands she had the bow of shining crystal—" She broke off, shaken by violent shudders. Then stumblingly she went on.

"She was holding it—so." Frieda made an illustrative gesture with her hands. "Holding it and gazing at it like, like, ohhh, how you say—a rabbit gazing at a snake!" Tears welled in Frieda's large brown eyes now. "There was a light shining from that damnable instrument, that weapon of crystal death. A light reflected in its shimmering string as the sunlight pouring through the window struck it. It was horrible!"

I looked swiftly at the crystal bow, then back at Frieda.

"Miss Madeline," she whispered huskily, "was staring at the bow as if she hadn't heard me come into the drawing room. And then something—I, I, could never describe it to you, caused me to cry out sharply, in fear. Miss Madeline had been just in the act of plucking the string on the bow, in fact she did so just as I cried out."

"And then?" I blurted, leaning anxiously forward.

"The bowstring, it sang zeeeeeiiiing, so, its vibrations ringing through the room like the cry of a wild beast. My scream must have come at the same moment, for I recall Miss Madeline turning, open-mouthed in astonishment, toward me. The shock of my cry caused her to drop the bow to the floor, as she vanished, disappeared completely, into thin air but a second later!"

FRIEDA had scarcely finished before she collapsed completely, sobbing wildly, shuddering brokenly, and all the while mumbling incoherently to herself in a combination of English and African dialect.

I was stunned, shocked, incredulous. The coffee-colored maid was out of her mind. She had to be. What she had described was more than humanly believable, more than humanly possible. There must have been something else, something that had brought about this temporary hallucination from which she suffered.

But no matter what the truth of the matter happened to be, one fact remained. Parts of her tale were indisputable; and other parts fitted into perfect coincidence with what had happened to Frederick Loche and Geno Marelli. The facts that fitted were two. Madeline had received the mysterious crystal bow. For it was lying before me on the rich red rug of the drawing room that very moment. Secondly, Madeline was gone.

I stood up, then, lifting Frieda in my arms like a child. I carried her over to the divan, placed her there, then went to a telephone and called the house physician of the hotel. The poor girl was more than merely distraught. She needed a doctor and a sedative badly. Then, perhaps, after she had rested, I would be able to obtain more coherent information from her.

When I returned from the telephone, Frieda was lying on the couch in a dazed, almost uncomprehending state. Her eyes stared dully almost glassily, at the ceiling. Her body was limp from utter nervous exhaustion. She was breathing heavily, like a person sleeping through an unpleasant dream. I didn't try to talk to her.

Then, for no reason I was sure of at the moment, I picked up the mysterious crystal bow and the wrappings that had covered it. I carried the bow and the wrappings to the kitchen where I disposed of the latter in the incinerator.

I stood there for several minutes, then, examining the crystal bow.

It was a strange, weirdly constructed weapon, fashioned—as I stated before—of a smooth, translucent, crystal substance that felt as soft as silk to the touch of my fingers. The center section of it was flanged slightly, yet rather narrow, while the sections on either end of the instrument were of wider flanges. It had about it the style of an ancient Mongol, or perhaps Persian, design. The bowstring, stretched tightly from end to end, was a thin strand of what seemed to be a solid silver thread.

I was turning the weapon around in my hands, examining it with more than curiosity, when the buzzer to the front door of the apartment sounded sharply several times.

There was a cupboard on my left, and I opened it hastily. The bow would just fit in there—it was perhaps five feet long—I found as I hastily placed it on a shelf. I still wasn't certain what prompted me to conceal it, or what had prompted me to destroy the wrappings moments before.

WHEN I went to the door the house physician, carrying the

ever present black bag, was standing there impatiently. He was a

little man, old, with thinning gray hair and pince-nez

glasses.

"In there," I said, pointing toward the divan where Frieda lay in the drawing room. "Miss Trudeau's maid has had a severe shock. I arrived here a few moments ago to find her practically incoherent. I think she'll need a sedative."

The doctor looked at me a moment curiously.

"Where is Miss Trudeau?" he asked.

"She's out," I said. "I expect her back shortly." Again I knew that I was concealing information, evidence of this mystery. And again I wasn't certain what prompted me to do so.

"And you are...?" the doctor asked.

"I am Thomas Lannister," I said. "A friend of Miss Trudeau's. I'm waiting for her."

"Oh yes," the Doctor said. "Music critic chap from the Blade, eh?"

He went into the drawing room, then, and I went back into the kitchen, lighting a cigarette. For the next several minutes I paced back and forth, taking deep draughts from my cigarette and trying to find some way to pierce the cloud of mystery and foreboding terror that lurked around the strange circumstances of the past twenty hours.

My anxiety for the safety of Madeline was foremost in my thoughts, of course, and it was only the almost obvious connection between her disappearance and that of Loche and Marelli that kept me returning to the circumstances of those other two mysteries. I was vaguely aware that—whatever was behind all this—the three occurrences were definitely linked to one another.

But every idea I had met inevitably against a stone wall in the blind alley of deduction. And before I knew it the doctor appeared in the kitchen.

"I would like you to help me move Miss Trudeau's maid to her bedroom," he said crisply. "You were right in presuming that she's had a severe shock of some sort. I gave her a hypo. She should sleep for five or six hours. After that time I'll be in to see her again."

I nodded vaguely, and went with the little medico back to the drawing room. There we both lifted Frieda gently from the divan and carried her into her bedroom. I found a heavy quilt comforter and placed it over her, while the doctor arranged the pillow beneath her head.

"I'll be back about the time she should be waking," he said.

"Thank you," I told him. "If you should be needed sooner I'll have Miss Trudeau call you."

The doctor left, then, and I closed the door of Frieda's room behind me and started back to the kitchen.

IT was while I was moving through the small hallway

leading to the kitchen that I passed the telephone table there.

There was a loud, static buzzing issuing from the receiving end

of the telephone, and I saw instantly that Frieda had left it out

of the cradle when she'd gone to call Madeline in the drawing

room. After what had happened then she had quite naturally

forgotten all about it, and left it as it was.

I stopped to put the telephone back into the cradle, realizing as I did so that here was the explanation for Madeline's line having been busy for so long. Obviously, right after my connection with her had been broken, the reporter from the newspaper Frieda'd mentioned had called. Frieda had then left the telephone momentarily to call Madeline and had never returned to it, thus leaving the line open and busy.

And quite suddenly another thought occurred to me. A reporter had been on the other end of the wire. And unless I was very much mistaken that reporter had probably been calling on Hendrick's advice from the offices of the Blade. With the wire open, and with the chap waiting for Madeline to answer him, he'd have been able to hear Frieda's sharp cry, or scream, and the ensuing commotion that followed when I arrived at the apartment.

Obviously, then, unless the staff of the Blade had lost its nose for news completely, a reporter would soon be over here to see what was going on. I hadn't figured on that. I hadn't figured on that any more than I'd figured on calling Hendrick to tip him off on this last disappearance. What the hell, newspaperman or not, this last occurrence was something for me and me alone to handle. And until I found out just what was what, Madeline's name wasn't going to be dragged across the front pages of Hendrick's Blade. Even if I hadn't been in love with the girl, I'd have thought too much of her for that.

I tried to calculate approximately how long it had been since the reporter from the Blade had called and gotten suspicious of his reception on the telephone. Fifteen minutes, perhaps. Maybe twenty. But at the outside, twenty minutes would just about give him time to be arriving here now.

Still debating mentally about the advisability of being on hand when the reporter from the Blade arrived, I went back into the kitchen. I took the crystal bow from the long cupboard in which I had concealed it, and again the very weirdness of its design, its appearance, reached out for my fascinated inspection.

There was an exit to a rear hallway from the kitchen. It would lead, I knew, to a freight elevator, and flights of fireproof stairs. If I wanted to leave, I'd better do so now, before Hendrick's snoop would arrive on the scene.

I thought for a moment of waiting him out, letting him sound the buzzer until his finger wore off. After all, aside from Frieda—who was now definitely "out" for the next few hours.—I was the only one present. If I didn't let him in, he wouldn't get in.

False reasoning, of course, and I realized it an instant later. No answer from this apartment would only further arouse the newshawk's suspicions. He'd go to a bell captain, or a day manager, and under the guise of grave concern, get them to force an entry to the apartment.

And yet I couldn't walk out now, leaving Frieda holding the bag on the entire ghastly mystery. It wouldn't be fair, especially since she was on the verge of a complete breakdown. And then, if she had had wild hallucinations, Madeline might very well return to the apartment.

My faith in the last presumption, however, was growing weaker with every passing moment. For something in the back of my subconscious was busily weaving an inner conviction that possibly Frieda's story of the disappearance into thin air was actual fact. My mind knew better, of course. That is, my active, thinking conscious mind knew better. But deep at the core of the soul of every man there lies a hidden, primitive, unrecognized factor that psychologists call sixth sense and gamblers term a hunch. And that hidden factor that sorts all unknown factors and arrives at an unspoken conclusion was pushing my mind eerily toward the conviction that there was more than hallucination and hysteria to Frieda's terrified account of what had happened.

And if what she had described had actually occurred—

I lingered over the implications of this thought an instant, turning it around in my mind as I turned the strange crystal bow unthinkingly in my hands.

Madeline had been in the act of plucking the bowstring when Frieda—strangely set to terror by the very sight of the weapon and the consuming fascination of Madeline's regard for it—had cried forth. Simultaneously with Madeline's plucking of the bowstring, Frieda's cry had rent the air.

Obviously, it had been the cry of horror that had startled Madeline into releasing her grasp on the crystal bow. Perhaps, too, it was her reaction to the weird sound set up by the plucking of the bowstring.

I recalled that Geno Marelli, although he had been seen with the bow in his hands minutes before his disappearance, had not left it behind him when he vanished. As for Frederick Loche, I could assume that he too had been given the package containing the bow. And if he had left it behind him it hadn't been found.

Could this bow in my hands, this weird crystal weapon, be the same one that was delivered to Loche, Marelli, and Madeline in turn?

And was it an actual instrument involved in the disappearances of the three, or just a symbol, an indication of what was to happen to them?

Evidence pointed toward its being the former. And yet, aside from the somewhat unique design of the weapon, it appeared to have no potential power. The bowstring was silver. That in itself was, of course, exceedingly strange. The crystal substance of which the actual strangely shaped staff of the bow was made seemed to be nothing more than glass. Unusually well processed glass, of course, but still nothing more mysterious than glass. So the very elements from which the bow had been constructed were not in themselves unfamiliar.

And yet the strange combination of the silver and glass in a bow of such weird design could, purposely perhaps, be a catalyst that gave an entirely foreign result.

I HAD continued to turn the weapon around in my hands as I

pondered these confusing mazes of speculation, and suddenly I was

aware that my right hand seemed subconsciously itching toward the

silver bowstring. I shifted the stock of the bow into my left

hand, held it up half as an archer might, reaching out the

fingers of my right hand to pluck the silver bowstring.

The impulse to follow through my gesture became at once almost unhumanly overpowering. And it was an instinct born of something stronger and deeper than natural reflex action. It was almost as if I had received a command from some mind stronger than my own. An almost irresistible command to place my fingers around that silver bowstring, draw it back, and release it.

My fingers reached forward, and I felt an inexplicable sensation of giddying weakness, chilling helplessness.

As if from a great distance, an evenly spaced ringing came to my ears. Vaguely, I was aware that it was the telephone in the hallway of the apartment.

The ringing continued, still as if from a distance, while I stood there posed like a futile archer without an arrow, my hand reaching for the silver bowstring.

I was conscious of that fact that every instinct seemed to tell me to answer that telephone. I was aware, also, that whoever was on that wire might have some connection with Madeline's disappearance.

It is impossible to describe the sensations that held me frozen in the same position while the telephone kept ringing. It was just as if—as I said before—some force, some power, some mind stronger than the resistance I could offer, was fighting back my natural reactions to break away from the overpowering command that urged me to pluck that bowstring.

I felt as if I were standing off at a distance, watching myself, witnessing my struggle to break the grip of that steel band of fascinating hypnosis. Watching the cold sweat on my forehead, the shaky uncertainty of my knees. Watching myself succumb to a terrifying power that was crushing my very instinct, my will itself in an ever closing fist of iron.

It was the sound of the telephone that gave me my last grasp on the straws of reality. It was something to cling to desperately, frantically, while I fought to keep from being drawn off into a wild, fearsome sea of black, unknown forces.

Then the telephone stopped! My grip was gone. My hand inched closer and closer to the bowstring. My fingers circled around it. My arm bent slightly, and I drew the bowstring back.

There was no stopping the irresistible compulsion to release the string. My fingers opened, my mind an agony of revulsion. The string twanged...

I WAS conscious, instants later, that every last material fibre of my being seemed engulfed in an overwhelming explosion of blinding electrical force.

Vaguely, in the chaos of sound and concussion that swept me into blackness, I could hear a strange, eerie zziinnng that I suspected dimly to be caused by the vibration of the bowstring I'd released.

The sound grew louder, louder, like circles spreading in a pool of water into which a pebble has been dropped. The blackness became a suffocating mantle which I was no longer able to thrust from my head and shoulders. The ringing of the explosion was still in my ears, shutting out further sensation as the blackness did the light. My right hand was clenched fast to the center of the crystal bow, fingers numb. And then I knew no more...

ETERNITY might have passed unnoticed in the interval

before I opened my eyes again. I know that I had no sensation

that time had passed. No realization, immediately, of what had

happened.

I was clutching hard to an object, like a straw in a turbulent sea. Gradually the bright white lights all around me were coming into clearer focus. My head was aching badly, and my body tingled weirdly. I was sprawled on a hard, warm, smooth floor. The crystal bow was still clenched in my right hand—the straw in the sea of dizziness.

And quite suddenly, then, my consciousness returned fully. I had plucked the silver bowstring. I had been standing in Madeline's apartment, and then—

Dazedly, I raised myself on my fore-arms. But this place in which I now found myself was—was certainly not Madeline's apartment! It was a huge, high domed room of tremendous proportions. It was fully a mile in length, a quarter of a mile high. It was white and crystalline, and utterly bare of anything save the walls and the floor and the vast ceiling!

And the source of strong white light that made me blink and peer dazedly at what I saw was nowhere visible.

Instinctively, my heart began to pound in the ominous excitement of the unknown. My mouth was suddenly dry, and I ran my tongue across my lips tentatively, climbing to my feet.

There was no sound in this vast room save the sound of my own labored breathing. There was no sign of life about me, anywhere. The floor, the walls, the incredibly distant ceiling—all these were signs of life if you like. Signs, at any rate, of human activity, human ingenuity and construction prowess, but not of human presence.

And now I realized that the bow was still in my hand. I gaped at it foolishly, as if I'd never seen it before.

I WAITED there, for what I don't know. Waited there, while

the sound of my own breathing came softly to me as if in echo

thrown down from that vast white ceiling. The excited beating of

my heart refused to still.

Some of the shakiness had left my limbs. The tingling in my body had stopped. My temples throbbed with aching monotony.

Something instinctive, some stray fragment of knowledge, had been at the back of my mind from the instant I'd opened my eyes in this incredible room. And now I realized what it was. Everything around me—the floor, the walls, the ceiling, was constructed of precisely the same crystal substances as the mysterious bow I held in my hand!

I was perhaps a dozen yards from the wall on my right, and I moved over to it, running my hand along the almost silky surface of it. There was about it the feeling of something akin to vibrancy. It seemed somehow alive to my touch. A ridiculous idea, of course. But nevertheless I took my hand from it swiftly.

My brain, all this time, had been working with increasing speed as I tried to sort the strange series of events that had led me to this weird room under such strange circumstances.

Knowledge as to precisely where I was, of course, was lacking. As far as I knew this could be Siam or Salt Lake. A week could have passed since I was in Madeline's apartment, or a month, or an hour. I had absolutely no idea of the time element.

How I had gotten here was something else as yet unfathomable. The forces that had brought me here were also beyond my ken. I recalled the swimming blackness that had engulfed me almost at the instant that I plucked the silver bowstring.

Apparently, shortly after my loss of consciousness, a person or persons had delivered me to where I now found myself. That much seemed evident—except for the fact that the person or persons seemed nowhere about.

This had happened to Madeline. I knew that much. She had then disappeared. Undoubtedly it had happened, too, to Marelli. Loche, also, had evidently undergone the same experience. The bow, the terrifying compulsion to draw the silver bowstring, the exploding blackness—and oblivion.

I wondered, suddenly, if they, too, had been brought to this vast and incomprehensible room of crystal and white light. And then I wondered how they had vanished. Perhaps by now I was also on the list of those who had "vanished." I cursed the wave of darkness that had deadened my senses and thus prevented my forming the haziest notion of how I had been brought here.

If the pattern were not to be broken—that is the pattern as I had imagined it until now—I was undoubtedly standing in a room in which Loche, and Marelli, and Madeline had stood before me.

But there was no trace of others having been here before. And the maddening, vast silence of my surroundings seemed to mock my effort to pierce their mystery.

THERE was a small door at the far end of this room, and

now I started for it. For some reason of which I was unaware at

the moment, I still carried the crystal bow.

My footsteps, strangely enough, made no sound in the vast hall. And yet my breathing continued to echo softly back to my ears. As I moved on doggedly toward the door, a cold sweat suddenly beaded my forehead and at the same instant I had the sensation that eyes were watching me from some invisible vantage point.

Several times I stopped, looked to the right and left and behind me. But there was still no sign of human presence. I felt those eyes more strongly after each such instance.

The door was not far away now, perhaps several hundred yards, and I found myself moving faster, as if trying to evade some unseen forces following behind me in that naked hall.

I could make out the general structural detail of the door more clearly now. It, too, was of crystal substance. It seemed to have no knobs or grasping points, but otherwise resembled a standard door in size and appearance.

The distance left to the door was now less than a hundred yards. I was wondering, of course, what lay beyond it. Wondering, when it opened quite swiftly, unexpectedly.

I stopped, my fist tightening around the bow in my right hand. A man stood outlined in the door frame. He was of medium height, with unusually wide shoulders, unusually thick arms, extraordinarily stocky legs. These physical characteristics were easily discernible, since he was attired in a tight-fitting costume of a grayish leather tunic top, and ankle-length breeches of the same leather and tightness.

He was staring at me—not hostilely, not cordially. He had gray eyes that seemed utterly devoid of any capacity for emotion. His face was round, rugged, and struck me as being a remarkable composite of all the peasant stock features of all races. There was no flicker of intelligence in the muscles of that face. It was neither pleasant nor unpleasant.

He had paused there momentarily in the doorway, staring at me. Yet I swear there was not even a trace of appraisal in that stare. There was nothing in his look that could be classified as human or unhuman. Yet, physically, this person was undoubtedly human. And now he started toward me.

I had been frozen, rooted by the shock of his sudden, startling entrance. Now I found voice.

"Who are you?" I demanded shakily. "Who are you, and what is this place?"

THE man in the grayish leather tunic continued to advance

toward me. His facial muscular reaction to my words were

unchanged, unblinking. He continued toward me. Instinctively I

stepped back, although there seemed to be nothing you could

interpret as menace in his advance.

"What is this all about?" I demanded hoarsely. This time there was a definite crack in my voice.

The creature in gray moved closer, less than five yards away now. His eyes were still fixed on mine, unwinkingly, unemotionally. I could read nothing in those impassive features.

But there was one positive indication in his advance that belied his outward lack of emotional display. The tight breeches he wore were snug enough to reveal the fact that his thigh muscles were bunching into readiness for swift action. I saw this the instant my eyes flicked to his legs. An old backfield trick, that leg watching. With it I'd been able to elude numerous would- be tacklers on the college gridirons in my student days. The very stance of a man advancing on you betrays his intentions.

This time I backed no further. I stood there waiting, watching on the balls of my feet, catching my timing from the rhythm of this fellow's stride.

He was four feet from me when I dove headlong at his muscular legs, pitching the crystal bow sideward as I did so.

I felt the solid crunch as my right shoulder drove into his thighs. Then my feet were stabbing the smooth floor, driving hard, picking up momentum as my arms wrapped around the back of his legs. It was close to a perfect tackle, and my adversary hadn't expected it.

We spilled to the floor an instant later as I jerked his legs up from under. I was on top, and my palm had come up against his forehead, slamming his head back onto the floor, but hard, as we hit. The solid clack of skull hitting floor surface was grimly, swiftly satisfying. Then his legs went limp. He was out cold.

I stood up quickly, untangling myself from the inert lump of emotionless humanity that lay at my feet.

Stood up to see the man I had just knocked unconscious coming through the door at me once more!

I stepped back in amazement, then looked again at the figure lying at my feet. No—the creature coming through the door was not the same chap who lay at my feet. Not the same chap at all—merely his twin!

The same medium height, the same unusually wide shoulder, unusually thick arms, incredibly stocky legs, and the same grayish leather tunic top and breeches of the same material. The facial similarity was also identical to the fellow lying at my feet. Even to the lack of emotion stamped on the newcomer!

If two people were ever stamped from the same mold, they were the man who lay at my feet and the other who was now advancing toward me from the door!

And the second chap seemed not to notice his counterpart lying unconscious at my feet. The gaze he had fixed on me was identical to the gaze the other had directed at me when he'd first entered. No curiosity, no hostility, no friendliness—absolutely no emotional reaction of any sort.

Except the same bunching, tightening, of the thigh muscles to indicate that he possessed the same intent as his predecessor.

THIS time I didn't wait. Perhaps I'd forgotten that timing

was everything. Or perhaps my easy victory over his counterpart

had made me too confident. I just drove in, bent low, head down,

arms swinging like sledges at this second adversary. The mistake

was mine, I knew it the instant my first punch had flattened my

knuckles against the solid wall of granite-like muscle that

should have been his solar plexus.

And then an open-handed swipe from a hard palm against the side of my head sent the world spinning and my knees buckling. I recall that I wondered foggily why my head hadn't parted company with the rest of my body after such a tremendous wallop. And I remember, too, that I kept throwing punches into the incredible muscle-armor of this new adversary. And then there was another solid, even more terrific open-palmed swipe, thrown down this time, down on the base of my skull. A sledge couldn't have done the job more neatly. I felt the floodgates of my will open wide as my knees turned to water and refused to support me any longer. A myriad of stardust whirled giddily around against a rich purple backdrop of utter darkness.

I felt as if I were falling through a million miles of space. Falling—while an incredible number of faces, all of them exactly alike, all of them the same as my adversary's, peered unemotionally down at me from a million miles above...

THERE was an immediate sense of luxurious comfort in my every muscle when I opened my eyes again.

I felt as buoyant and refreshed as a man who has slept fifteen hours with an easy conscience. Under me there was a mattress of some sort of down which I suspected to have been gathered from the wings of angels. Covering my body were silken sheets, and beneath my head a silken pillow of the same angel-down.

There was no ache in my head, no uneasy sensations in my limbs or stomach. I had the sensation of never having felt better in years. My waking had been caused by nothing of which I was immediately conscious. And now there was no foggy, fuzzy aftermath of sleep to cloud my mind. The first thing I remembered distinctly, almost instantly, on waking was my recent unsuccessful struggle with the emotionless humans in the hall of crystal.

I felt the side and back of my head in instinctive wonder. It should have been throbbing horribly. But as I said before, physically I was utterly refurbished, completely atuned. And now, sitting up in my luxurious bed, I turned my attention to my new and strange surroundings.