RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

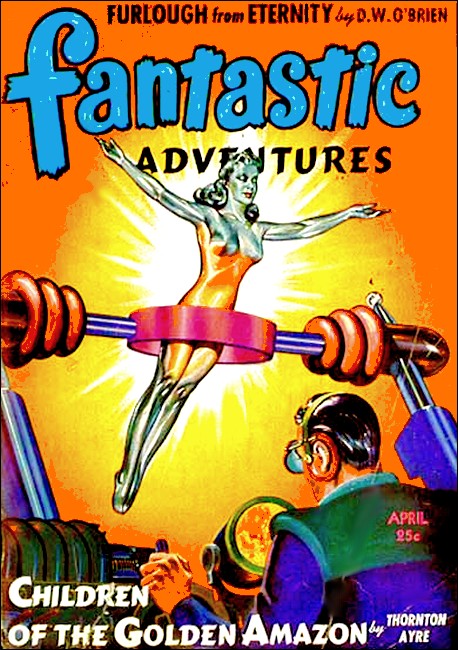

Fantastic Adventures, April 1943, with "Where In The Warehouse?"

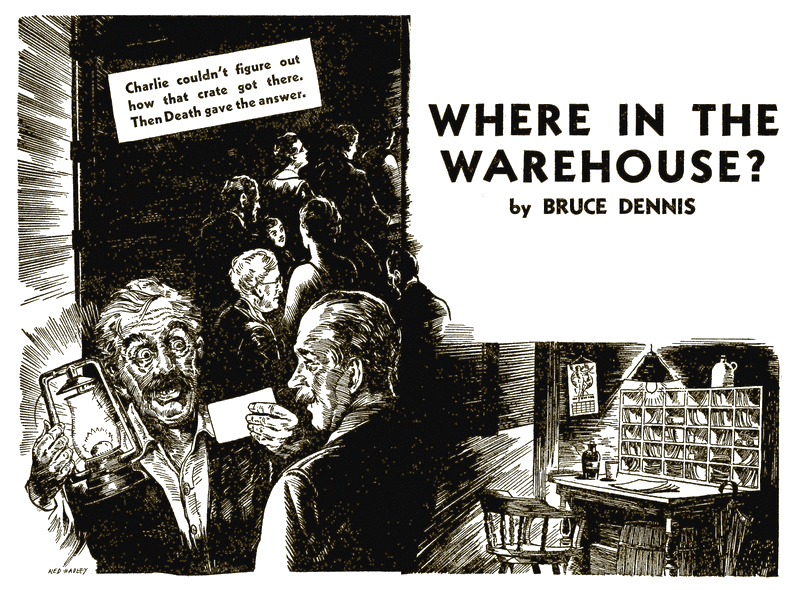

The amazed watchman examined their cards and let them pass.

IT was on a perfectly ordinary winter afternoon in early December that Lucius Fowler, owner and manager of the vast and gloomy Western Scenery Warehouse, received the dapper, middle-aged, rather handsome Mr. Santospedros in the warehouse office.

Fowler had appraised his prospective customer even before that gentleman had taken a seat before his desk.

Looks theatrical, Lucius Fowler thought to himself, but perhaps a little too much the gentleman-type to be stage show. Maybe he's representing some touring stock opera company. Seems Italian, or Greek, from his name.

"And what, sir," said Lucius Fowler aloud, "can I do for you?"

"I'm here," said the gentleman who'd announced himself as Mr. Santospedros, "to inquire about your warehouse."

"Certainly, sir. Certainly," Fowler beamed. "What do you wish to know about it? Are you inquiring about the prospects of renting stage or opera scenery? If so, we still have much on hand that has not been used by the opera and stage companies already playing here in the city. I think we could fit any requirements you'd like."

Mr. Santospedros smiled and shook his head in a gentle negative.

"No. Not precisely that, Mr. Fowler," he said. "I wish to inquire about the possibility of renting some space in your warehouse for a short time. I, ah, realize you have a tremendously large warehouse—naturally, since you store and rent stage and opera scene sets—and that at this time of year, with the stage and opera troupes in the city for long runs, you must have considerable space vacant at present."

Lucius Fowler frowned and rubbed his bald head reflectively. It was true that, with so much of his stock scenery rented out to stage and opera companies in the city at that time, he had a considerable yardage of vacant storage in his warehouse. But a request to rent such space, rather than rent stock scenic sets—which were after all the sole reason Fowler operated the warehouse—was distinctly unusual. True, the Civic Opera Company rented space between seasons to store their scenery. But the Civic Opera Company was the only organization permitted to do so, and that permission was given by Fowler merely because the Opera Company didn't rent scenery, but made its own at great expense.

So Lucius Fowler rubbed his head and frowned.

"Your request is somewhat unusual," he admitted.

Mr. Santospedros smiled his suave, handsome smile and agreed that it was probably an unusual request.

"However, Mr. Fowler," he added, "your warehouse is the only storage place with enough loft to suit my needs. There isn't another warehouse in the country, as far as I know, that would fit my specification demands. Although I am not in the theatrical business and don't want to rent scenes from you, I can pay you whatever price you set on whatever storage space you can let me have."

MR. LUCIUS FOWLER stopped rubbing his bald head and asked, with a little more interest, how much space Mr. Santospedros thought he would need.

"Every inch of loft space your warehouse can afford," Mr. Santospedros replied. "The, ah, item I intend to store is exceedingly tall. I inquired about the height of your warehouse before coming to you. It will just fit. As for width, I'd need perhaps fifty yards. The length," and Mr. Santospedros smiled, "would mean about five yards all the way along the fifty yard width of the, ah, object."

Lucius Fowler closed his eyes and tried to visualize an object of the dimensions his prospective customer had stated. It wasn't easy, and the closest Fowler could come in his visualization was something resembling an enormous and unusually thick stage back-drop. But there wasn't any stage in the world, to his knowledge, which could use a backdrop as lengthy as the distance from the floor to the ceiling in his huge warehouse. Neither was there ever a backdrop of that length and width which was five yards thick. Lucius Fowler gave it up and expressed his curiosity vocally.

"Just what is this object you intend to store, Mr. Santospedros?" Fowler asked.

Mr. Santospedros smiled charmingly, revealing his flashing teeth, and in his liquid smooth voice and cultured tones gave Fowler no satisfaction.

"I'm sorry," said Santospedros, "but I cannot tell you that, Mr. Fowler."

Having the balloon of his curiosity so neatly punctured made Lucius Fowler suddenly a bit indignant and more than a little snappish. He rose abruptly behind his desk.

"I am very sorry, Mr. Santospedros," he said, crisply reproachful, "but under those circumstances your request for storage space becomes extremely unreasonable. How can you expect me to accept for storage anything about which I am totally ignorant, is beyond me. After all, sir, being entrusted with the warehousing of your property it is only reasonable that, to protect myself and your goods, I should know what they are. Good day, Mr. Santospedros."

Mr. Santospedros didn't rise. He smiled, and reached into his inner overcoat pocket and pulled forth an exquisitely tooled wallet of some silken leather. He opened it, still smiling, took forth a sheaf of crisp, new, one hundred dollar notes, and tossed them carelessly on Fowler's desk.

"You will find that sheaf contains five thousand dollars, in hundred dollar bills, if I'm not mistaken," said Santospedros in his dulcet voice and charming persistence. "I, ah, feel that the extra reimbursement should compensate for what I am unfortunately unable to tell you regarding the object I wish stored. And as for your responsibility in the matter of the object's safety, I'll sign any waiver of such responsibility you might wish. All I am after, Mr. Fowler, is storage space. I shan't need it for long. Certainly not longer than a month. I will see that it is stored in your warehouse, and will provide men for its removal."

LUCIUS FOWLER, eyes bugging at the currency Santospedros had so casually flipped onto his desk, sat down as abruptly as he had risen.

"I, ah. I, that is—" began Lucius Fowler. His voice cracked, and he was unable to tear his eyes from the money.

"You accept my offer?" Santospedros asked pleasantly.

Lucius Fowler cleared his throat and managed at last to take his eyes from the five thousand dollars.

"You say you'll only need the space for a month?" he asked his would-be customer incredulously.

"At the very most," said Mr. Santospedros. "Perhaps not that long."

"But—but," Fowler stammered, "you don't mean to say you are willing to pay five thousand dollars for storage for a month or less—especially when my warehouse won't be responsible for protection of the, ah, object?"

Mr. Santospedros smiled. "That is precisely what I mean to say," he agreed. "As I said before, your warehouse is the only one suitable for my purposes. It is worth five thousand dollars to me to get that storage space for that length of time. Is it worth the same amount to you to let me have the space?"

Again Lucius Fowler looked at the money. He found a handkerchief in his hip pocket and mopped his brow.

"Yes," he said at length. "Of course it is, Mr. Santospedros. Five thousand dollars is a lot of money. A lot of money indeed."

"Indeed," Mr. Santospedros agreed, rising. He smiled amiably, charmingly.

Lucius Fowler wet his lips.

"Ah, incidentally," he said, "I wish you'd give me your word, Mr. Santospedros, that there is nothing, ah, er, dishonest in your desire for that storage space. After all," he added hurriedly, placatingly, "I have to protect the integrity of my business and reputation."

Mr. Santospedros smiled more widely than before.

"I give you my solemn assurance, Mr. Fowler, and my fervent pledge of word, that there is nothing dishonest in my intent concerning the storage space or anything else. Does that satisfy you?"

Lucius Fowler picked up the five thousand dollars with hands which, blamelessly, shook with eagerness. He smiled contentedly.

"Perfectly," Fowler answered.

"Good," said Mr. Santospedros, moving toward the door. "Then there is one thing more I must arrange with you." He paused. "I shall have workmen in the warehouse from time to time, during the evening. They will bear passes which will identify them as being in my employ. I want your night watchman to be informed of this, and informed, also, that he is not to bother them, or try to watch them after they enter the warehouse."

"Workmen?" Fowler blinked in surprise.

"Yes," said Santospedros with his ready smile. "I am merely storing the, ah, object, to enable me to make certain repairs on it. That's why I rented the space. Since the entire transaction is of a necessarily secret nature, I feel that it will be better if they enter at night. That, too, is why I don't want your watchman to get too curious about the object or the men who enter on my pass."

LUCIUS FOWLER gripped the five thousand dollars in his hands tightly, uneasily. This whole thing got more and more curious. There was something about it—but he remembered the five thousand dollars in his hands. Well, it was only for a month at the most. And if anything got out of hand, he could take care of it. He gave his customer an uneasy smile.

"Very well, Mr. Santospedros. I'll inform Charlie—he's our elderly night watchman—to expect such occurrences. When do you expect to bring the, ah, object to the warehouse?"

"Tonight," said Mr. Santospedros. "My men will handle it. You merely tell your watchman to expect the object's arrival. Incidentally, what space will be available? You'd better let me know right now."

Fowler looked down at the warehouse map under the glass top of his desk. It showed clearly the vacant spaces in the storage sections. He rubbed his bald head professionally, pursing his lips in contemplation.

"There's a section open in the rear which is of perfect size for your, ah, object, Mr. Santospedros," he said. "It's section 25, you can tell your men that. Charlie will direct them to it."

"Twenty-five, eh? Good. I'll remember that," said Mr. Santospedros. "Then everything is settled. That five thousand pays me up for a month, right?"

"Absolutely," said Fowler warmly. Then he added: "Incidentally, I meant to ask you how Charlie will be able to identify the men you send to the warehouse after the, ah, object is installed?"

Mr. Santospedros reached into his wallet pocket and pulled out a small, engraved business card. He stepped from the door to Fowler's desk and handed it to Fowler.

"Give him this card," said Santospedros, speaking of Fowler's night watchman. "He can compare it with the cards presented by the men who come there. I'll see that they each have a similar identification card."

Lucius Fowler took the card. "Fine," he said. "An excellent idea." He dropped it into his pocket, then extended his hand to Mr. Santospedros. "Well, sir. Everything is set. The deal is closed. I hope you find everything satisfactory."

His handsome customer smiled again and took his hand. He shook it briefly, nodded, turned for the door and left the office with lithe, swift grace, the door closing soundlessly behind him.

For fully a minute Lucius Fowler stared at the door, his expression one of pleasure mingled with doubt and suspicion. Then he sighed bewilderedly and resumed his seat at his desk.

Carefully, Lucius Fowler spread the money out across his desk. Fifty one hundred dollar bills. Crisp and fresh. Just as if they'd rolled off the presses in the Mint. Fowler looked at them for a minute or more, mopping his brow with his handkerchief. Then, as if he suddenly realized the danger of his present situation, he sat bolt upright and grabbed the telephone at his elbow.

"Hello," he said a few moments later. "Is this the National Bank? Send over a messenger to the Western Scenery Warehouse. I have a rather large amount of cash I want deposited to my account. What? Oh, five thousand dollars. Yes, that's right. Will you send your messenger right over? Thank you."

MR. LUCIUS FOWLER replaced the telephone in its cradle with considerably more calm. The danger in having all that money around was now off his mind. He gathered it together and dropped it into a drawer in his desk until the messenger should arrive.

Then Fowler put his elbow on his desk and his chin in his open palm, assuming a contemplative attitude in order to meditate more seriously about the rather mysterious Mr. Santospedros and his extremely mysterious object for storage.

Fowler wondered at great length what the object could be. Then he gave up this procedure and began to wonder if it would be wise for him to be on hand that evening when the mysterious object was brought to the warehouse. No, he finally decided. He'd better not be hanging around. For all he knew, Santospedros might personally supervise the installation of the precious object of storage. And in that case, Fowler's ill-concealed curiosity wouldn't look well.

"I'll just hold my curiosity for tonight," Fowler decided aloud. "After all, if I got Santospedros sore he might demand his money back and take his mysterious whatever-it-is to some other place. I'll have plenty of time to look in on it, and unless I'm an absolute fool, I should be able to guess what it is no matter how well it might be crated or packed."

Having thus made up his mind, Lucius Fowler tried to get back to work. But it wasn't that easy. For the life of him he couldn't keep his mind from straying back to speculations concerning the mysterious storage object. It presented definitely intriguing speculations....

OLD Charlie Cooper, night watchman at the Western Scenery Warehouse, uncorked his bottle of "tonic" and took a short but thoroughly satisfying swig. He smacked his lips, recorked the bottle, and returned the "tonic" to the pocket of his frayed overcoat.

It was a derned chilly night, he reflected. Nuff to freeze a man into one of them icicle statues you read about.

Old Charlie reached forward and poked with a stick of wood at the coals inside the tiny stove before him. Then he put the stick aside and sat back on the wired-together chair which was his prized "at-work" possession.

Charlie took the turnip watch from his pocket and peered nearsightedly at its hands, holding it close to the glow of the stove to see it better.

Derned near ten o'clock, it was. Late. Derned late. Too derned late fer men in their right minds to be a-carting stuff to a warehouse fer to store, Charlie decided.

But ole' Fowler had told him that they wuz coming.

"Don't know when they'll arrive," Fowler had told Charlie. "Sometime tonight, though. You show them to section 25, and if there's anything to be done to help them, do it."

"Won't be coming now," Charlie figured. Too derned late fer to be a-dragging things into a warehouse. Nosir. Too derned late.

Charlie sighed. The glow of the fire was warming, or maybe it was the "tonic" taking effect. At any rate it made him drowsy. He decided that he might just as well grab off a little snooze before his next inspection trip around the outside of the vast warehouse. The old man closed his eyes.

His soft, regular snore began almost instantly....

LUCIUS FOWLER hadn't had a good night's sleep at all. As a matter of fact, almost all of his slumber that night was limited to fitful catnaps between ponderings over Mr. Santospedros and his mysterious object of storage.

Consequently, it was eight o'clock, an hour ahead of his usual schedule, when Fowler arrived at the office of his warehouse the following morning. He was red-eyed and irritable from his lack of rest, but he was definitely brimming over with curiosity concerning the unknown possession of Santospedros which now undoubtedly occupied section 25 in his huge warehouse.

Molkov, the big Russian laborer who served as warehouse roustabout during the morning, and who relieved old Charlie Cooper's night watch shift at four o'clock every morning, was asleep on the office table, and obviously surprised by his employer's early and unexpected arrival.

But to Molkov's great relief, Lucius Fowler seemed not to notice that he had been sleeping on duty, and only demanded the warehouse keys in a voice ragged with impatience.

"Did the new storage consignment get properly stored last night, Molkov?" Fowler demanded, taking the keys.

Molkov, sleep still in his eyes, blinked and shook his head.

"No. It is not arriving. Cholly tell me when I am taking over his shift that the storage you expect and tell him expect do not come at all."

Fowler stopped short in amazement. "Didn't arrive?" he demanded. "You say Charlie said it didn't arrive?"

"That," said Molkov indifferently, shrugging his massive shoulders, "is what old Cholly is telling me."

"But—but," spluttered Fowler indignantly, "the man who rented that space said specifically that the stuff, the, ah, object would arrive last night!"

Molkov picked his teeth unconcernedly with his thumbnail, shrugging again.

"Why you no look see," he suggested, "if you no believe?"

"I'll do exactly that!" snapped Lucius Fowler, turning away and striding off in a jangle of keys to the warehouse doors.

A minute later Fowler was striding quickly through the high ceiling warehouse where an incredible array of stage and operatic scenery of every description was stored.

And minutes after that he turned a corner in the block-long building and found himself in section 25, the section to which he had assigned Santospedros' storage consignment.

The section was filled with an enormous object. And the identity of the enormous object was concealed by careful crating and wrapping. But from the incredible height of the object, and the width and thickness, there was no doubt left in Fowler's mind that this was the mysterious, ah, thing, for which Santospedros had rented space.

Fowler stood there staring at it in amazement.

It reached almost completely to the top of the warehouse ceiling; in other words, almost three hundred feet high. It was easily fifty yards wide, and certainly five yards thick.

But what in the hell was it?

Fowler stopped gaping and stepped toward it. And then the voice sounded almost at his ear.

"Uh-uh, old man. Sorry. You'd better run along. This isn't here for display, you know," said the voice.

FOWLER wheeled to face the owner of the voice which had so startled him. He found himself confronting a handsome, clean-jawed, exceedingly muscular young man with blond hair that was silken and clothing that was obviously expensive.

The young man was smiling cheerfully. Smiling in a way to remind Fowler for a fleeting instant of the way Mr. Santospedros had smiled the day before.

"Who a-are you?" Fowler demanded.

The extremely muscular young giant smiled amiably, courteously, and answered in a voice that was soft, yet positive.

"It doesn't make any difference who I am," he said. "But my job is to keep people from nosing around this object here."

"But—but I'm Lucius Fowler," Fowler protested. "I own this warehouse!"

The muscular young giant smiled his handsome smile.

"I'm aware of that," he said. "I recognize you from Mr. Santospedros's description of you. He said your curiosity might possibly get the better of you."

"Why—why—" Fowler spluttered.

"Move along now, Mr. Fowler," said the young giant pleasantly, putting his massive hands gently on Fowler's shoulders. "My boss has rented this space, and for the duration of the rental it belongs to him and not to you. I have my orders, and my job is to keep people from prying around the object we have stored here."

Lucius Fowler took the subtle hint provided by those massive hands resting ever so gently on his shoulders. He moved along, and paused for a moment, out of range of the young man's hands.

"This—this is highly irregular!" he snapped indignantly.

The handsome young giant smiled.

"It most certainly is," he agreed cheerfully. "Good day!"

"Humph!" snorted Fowler, turning and stalking off. But it was occurring to Fowler as he stomped back to the front office of the warehouse, that there was something else in the picture which was highly irregular.

Molkov had told him that Charlie had insisted the storage object hadn't arrived last night. If it hadn't, how was it there now? And since, obviously, it had arrived last night, in spite of what old Charlie told Molkov, it would have been impossible for the old fool to have missed it. Utterly impossible. Why, an object of that size would probably result in waking up the neighborhood getting it into the warehouse.

Back in the office, Fowler questioned Molkov again. But the big Russian merely shrugged and repeated what old Charlie had told him. At least there was nothing to do but decide that old Charlie, for some obscure and senile reason, had been pulling the Russian's leg in lying to him about the object's not having arrived.

Through the rest of the day Fowler contented himself with this explanation. And during the day, also, Fowler tried to find the name and address of Mr. Santospedros in the telephone book. He failed in this effort, then tried a few of the swankier hotels to find out if they had a Mr. Santospedros registered with them. None of them had, a fact that increased Fowler's irritation and impatience. For he wanted to thresh certain matters out with Santospedros at the first opportunity. He wanted to demand to know what was the reason for that gentleman having employed a guard to keep him—Lucius Fowler—away from the mysterious storage consignment. It was ridiculous. It was worse than that, it was insulting.

However, having been unable to locate Mr. Santospedros through the telephone book and other similar checks, he gave up that idea and said a small prayer that the middle-aged, well-dressed, handsome customer would drop in some time that day to see that his stored object was all right.

SEVERAL times thereafter, in the forenoon and after lunch, Lucius Fowler took quiet, almost stealthy trips back through his warehouse in an effort to have another look at the huge, mysterious, crated object in section 25. But on each occasion the smiling, polite, blond giant had stepped up to him from some darkened corner to suggest courteously that Fowler get back to work and cease his efforts to pry forth the secret of the storage item.

The second time it had happened, Fowler made a quick mental resolve to return to his warehouse that night and have a look at it. And then, to Fowler's somewhat shaken astonishment, the young man apparently read his mind.

"I wouldn't advise coming back this evening, Mr. Fowler," he said amiably. "I'll be here. Or if I'm not, there'll be another guard. It's really quite pointless of you to hope for a chance to pry around this crate. Why don't you forget it?"

Fowler had gotten back to work, flushed and even more indignant than before. But he didn't forget the mysterious crate for an instant. Now it was a burning question in his mind more than ever before. A burning question which had to be cooled off by the satisfaction of knowledge before he went slightly daffy from the terrible curiosity that gripped him.

By five o'clock that afternoon, Fowler gave up the idea that Mr. Santospedros might drop in to inspect the object in section 25 by daylight.

And when Fowler closed up the office to go home, half an hour later, it was even more difficult for him to reconcile himself to the fact that there'd be little sense in his going back to the warehouse later in the evening in an effort to learn something about the mysterious object occupying section 25. Undoubtedly the smiling young man's warning against trying to do so had been anything but a bluff. Fowler felt glumly certain that there would probably be a guard on duty in front of that enormous whatever-it-was night and day. And, too, hadn't Mr. Santospedros mentioned that people would be coming to the warehouse to work on it?

Fowler sighed, therefore, and bitterly resigned himself to make the best of checking his curiosity until the chance presented itself for him to find out what this was all about....

OLD Charlie Cooper was somewhat surprised when he arrived for the night watch. Surprised not to find a note from his employer, ole' Fowler, telling him that the shipment for section 25 would be in tonight, on account of being delayed or something last night.

But when Charlie made his first round of the evening, and peered through the window at the rear of the warehouse, the window right off section 25, he was more surprised.

For section 25 was filled with the biggest derned something or other Charlie had ever seen.

It never entered Charlie's old head that the something or other wasn't some weird piece of stage or operatic scenery. All the other stuff in the warehouse was scenery, wasn't it? Course it was. So this new stuff must be scenery, too. Although Charlie couldn't guess what kind.

"Hmm," mused old Charlie, peering in through the warehouse window, and holding his lantern high to see better, "musta been a-carted in today. Yessir. Musta been. No wonder ole' Fowler didn't leave no note. No wonder."

And then Charlie remembered that there might be people coming, then. People like ole' Fowler said. People to be admitted to the warehouse so's they could go back to section 25 and work on whatever that big object was. Ole' Fowler had said they'd only come at night. Derned funny, it was. Old Charlie had had half a mind to tell Fowler that he thought it a mite curious people should be stomping into a big ole' warehouse in the dead of winter and at night too. But he'd held his tongue, and figured his employer knew what he was about.

Then Charlie dug into his pockets until he found the card Fowler had given him.

"You aren't to let them in until they can show you a card just like this one," Fowler had told him emphatically. "Remember that, now!"

Charlie held the card—now grimy from residence in his pocket—to the light of his lantern. Slowly, he spelled out the letters of the name engraved on it.

"S-a-n-t-o-s-p-e-d-r-o-s," Charlie mumbled "Santispeederos, eh?" he muttered. "Eyetalian, I'll bet. Or Greek."

Charlie put the card back in his pocket and hurried over the rest of his first inspection. When he got back to his stove and wired-together chair, however, he was just in time for the first of the arrivals about whom he'd been told.

This arrival was a quiet young man in a big thick overcoat that had the collar pulled up around his chin. Leastways, Charlie figgered the young fella was quiet. He didn't say a word. He just handed Charlie a card, and it turned out to be just like the card Fowler had given Charlie. The one with the Eyetalian, or Greek, name on it.

The young man watched, hat brim pulled low over his eyes, while Charlie compared the two cards. He still didn't say a word. Satisfied that the two cards were pretty nigh identical, old Charlie opened the warehouse door and instructed the young man at great length on how to find section 25.

The young man never said a word. He just set off the way Charlie had told him to. Charlie was prompted to follow. But ole' Fowler had told him not to pry into anything the people who came at night would do. So Charlie sat down in his wired-together chair and pulled out his "tonic" bottle.

This night was going to be the long shift. The Roosian, Molkov, wouldn't arrive until nine in the morning to relieve Charlie. Then, the next week, it would be the Roosian's turn to take the long shift. Charlie sighed and uncorked the bottle, taking a long pull from it. He smacked his lips. Big help, tonic. Kept a feller warm. Specially when a feller wasn't getting any younger or spryer.

CHARLIE sat there for about fifteen minutes more, thinking how nice it'd be if he could retire some day. Funny thoughts fer a feller to be thinking at eighty or better. If a feller ain't retired by eighty there's slim chance of his ever losing his harness.

The old ticker wasn't getting any stronger, Charlie knew. Nosir. There'd been a mite of a dizzy spell just this morning and everything had gone black and whirling fer a few seconds while the ticker hurt and Charlie felt as if the wind was squeezed outta him.

Charlie's thoughts were interrupted by the arrival of two more people who were evidently seeking admittance to the warehouse to work on the thing in section 25. Neither of them said a word, which was funny, since one of them was a woman.

The other one, a middle-aged man, handed his card to Charlie first. It was just like the card Charlie had. And then the card that the woman, also middle-aged, handed to him also passed the comparison inspection.

Charlie was puzzled by the pair. They seemed to be together but they didn't even speak to each other, let alone Charlie. He let them into the warehouse and gave them directions on how to find the section, and went back to his wired-chair and coal stove.

Women workers, eh? Charlie mused. Mebbe war work, eh? He'd heard tell of women workers now, since war and all. This was the first he'd seen. And it was then that Charlie realized the first three arrivals hadn't carried tools or lunch buckets or anything workers might carry.

He puzzled over this surprising detail for a while until the next arrival. This was an older man. A man about Charlie's age. But he wore the clothes of a rich man and looked like nothing more than a financial tycoon stepping out of an international economic conference.

Like the others, he didn't talk. And like the others he didn't carry any work tools or a lunch pail or anything to indicate he was going to work on anything.

Charlie took the card he presented, saw that it was okay, and admitted this richly dressed old man to the warehouse. He gave him directions like he had the others.

And then they began to come in steady succession. One after the other, occasionally in twos, very occasionally in threes, and once in fours. They came at the rate of about one arrival every five minutes, and Charlie was kept plenty busy for the ensuing hours.

By midnight he had admitted almost eighty of them. And they had been of all ages, both sexes, and all stations in life. Old Charlie found his head aching from the strain of figuring out what those people were going to work on or with when not a single one had come with tools or seemed prepared for work. None said a word.

It was the derndest thing old Charlie had ever experienced. Nosir—it was even worse—it was the gol-dernedest!

Charlie had been surprised that there had been so many so old. Some of them even older than himself. Charlie was so surprised and on edge, in fact, that he skipped his doze completely that night. He stayed wide awake straight through, even though no other arrivals presented themselves after midnight.

AND it was along about seven o'clock in the morning when Charlie began to figure they were all about due to knock off work in there and head for their homes.

But another half hour passed and none of them came out. That was when Charlie figured that maybe they didn't have watches and would be glad to have someone tell 'em what time it was getting to be.

So Charlie got out of his wired-through chair and went into the warehouse to tell them. He went all the way back to section 25 to tell them.

But they weren't there. Not one of them was there. Not one of the close to eighty who'd entered. There wasn't a soul in section 25. Nosir, nary a soul!

Charlie looked all around the warehouse and called out as loudly as his old voice could. But his only answer was a feeble echo to his feeble shout.

"Wall, I'll be derned!" Charlie exclaimed.

It occurred to him that none of them could have left without passing the same way they came in. Which would mean that, had they left, they'd have had to pass Charlie.

"But I'm derned if they did, ary one of 'em!" Charlie pondered with indignation and no little bewilderment. "An', consarn it, they jest couldn't sneak out by me!"

Muttering this way to himself, Charlie gave the towering object in section 25 a suspicious and baleful glance, then shuffled back to the front of the warehouse and his stove and wired-through chair. He'd have to report the consarn derned mystery to ole' Fowler. Yessir. Report it first thing. Good he was on late shift, otherwise he'd leave too early to catch his employer....

IT was undoubtedly unfortunate that Lucius Fowler had spent another restless, sleepless night when old Charlie Cooper, the night watchman, buttonholed him that morning with his tale about the eighty people who went in but never came out of the warehouse. Unfortunate, that is, for poor old Charlie.

Fowler, ordinarily and kindly and decent enough man, was not at all himself that morning. His nerves, doubly overwrought by the gnawing curiosity concerning the object in section 25 of his warehouse, were trebly frayed from lack of sleep over a two-night period.

He listened to the rambling, bewildered plaint of poor old Charlie Cooper with a feverish gleam in his eye.

"So the workers went in and never came out, did they?" Fowler asked harshly, when Charlie's tale finally took on a little clarity to him.

"Yessir," said Charlie, "that just how it happened. They jest plumb disappeared, seems like!"

Fowler's voice grew harsher.

"Just disappeared, eh?" he snapped. "Into thin air, eh?"

"Yessir," Charlie maintained. "Inter thin air!"

The gleam in Fowler's eye flickered more angrily. He was aware, of course, that Charlie kept "tonic" with him on the job and warmed his old bones with it on cold nights. Fowler had never objected to this as long as Charlie stayed sober. He suspected that old Charlie did considerable sleeping before the stove fire, but had never objected to that particularly, so long as the old man made the regular two-hour checks.

"Did you have to help them get the stuff into section 25 the night before last?" Fowler demanded.

Old Charlie blinked dazedly.

"How's that? Don't rightly git you. They didn't bring no stuff into section 25 that night, even though you said they was gonna. Nosir, they didn't, noways. When I seen the stuff in that section on my first round last night I said to myself that it musta come in that very day."

Fowler put his hands on his hips and glared wrathfully at old Charlie.

"So the stuff never came in, as far as you're concerned, eh? So what you told Molkov about the object for storage in 25 not arriving was the truth as far as you knew it? So that tremendous, eh, whateverthehellitis, was moved into the warehouse and you never even knew it, eh?" His voice rose to a sarcastic, blistering crescendo. "It couldn't have been that you were asleep or drunk, or both, could it?"

Old Charlie looked shocked and reproachful and a little guilty.

"Now, Mister Fowler, you know I don't git drunk on the job. An, as fer sleeping, waal, I coulda dozed a mite, that night. But I'da sure heard 'em if they moved in that big whatchamacallut!"

But Fowler wasn't to be stopped. He was on the rampage.

"You don't drink on the job to the point where you get drunk, eh? Is that your story, eh? Oh, no. Like hell you don't! You get so drunk you walk in here and tell me eighty people just disappeared into thin air!"

OLD Charlie started to protest this injustice. But Fowler cut him off.

"God knows I've tried to be decent and tolerant with my help around here, Charlie," Fowler raged. "But, by God, when I'm taken advantage of, and made a jackass of, when I'm told by a drunken night watchman that eighty people disappeared into thin air after entering the warehouse—and then expected to believe it—it is TOO much!"

This time Charlie got a word of protest out.

"But—" he began.

Fowler cut him off. "I've got every right in the world to fire you, Charlie, and I think I might at that. You go home and take a week off. Come back here at the end of that time, and if I go crazy I'll hire you back. A week layoff should make you adopt a few reforms. It depends on those reforms if I take you back or not."

Old Charlie looked at the still-angry glint in his employer's eyes, mentally deciding that there wasn't anything he could do or say in defense of his actions in the face of Fowler's present mood. The old night watchman sighed. Once before, ole' Fowler had fired him for a week. It had had something to do with a small fire in the back of the warehouse. Old Charlie had dozed through the blaze until it was reported by the inhabitants of a building across the street. Yep, ole' Fowler had been sore that time, awright. But he'd hired old Charlie back after a few days or so.

"Yup. Yup. If that's the way you feel about it, Mr. Fowler, guess there ain't nothing I kin say," old Charlie declared sadly.

"Now, for the love of God, get out of my sight!" Fowler snapped despairingly.

Fowler heaved a sigh of relief as old Charlie shuffled out of the door. Then, running a badly trembling hand through the place where his hair had once been, Fowler wiped the tiny beads of perspiration from his bald dome.

Everything was getting out of control. Everything—including Fowler's sanity. The two sleepless nights Lucius Fowler had already spent as a result of Mr. Santospedros and the mysterious object of storage, were capped, so to speak, by crazy old Charlie's drunken babbling and inefficiency.

Of course Fowler was aware that the persons Charlie had admitted to work on the object in section 25 had not, could not, have disappeared into thin air. They had all undoubtedly gone out just the way they'd entered—past Charlie. And they had probably gotten much amusement from the old night watchman's drunken snoring.

It occurred to Fowler, then, to wonder if he could trust his ex-night watchman's estimate of the number of people who'd presented cards from Mr. Santospedros to admit them into the warehouse. Almost eighty sounded like an awful lot. What would eighty people possibly have to do on the object in section 25?

And yet once again, what in the hell was the object?

For the first time since receiving the money from Mr. Santospedros, Lucius Fowler found himself wondering if all this excruciating mental torment was worth five thousand dollars.

LUCIUS FOWLER took a deep breath, squared his shoulders, and started into his warehouse storage rooms. He was sick and tired of all this. Damned sick and tired. He was going to find out what it was all about, or else.

The steady, determined measure of his tread sounded his indignation in the echoes through the warehouse. And, by the time he had gone the length of the huge storage room, it had signaled his arrival to the blond, handsome young giant who guarded the object in section 25.

When Fowler saw him step out into the aisle, his heart sank, his determination ebbed. He'd forgotten about this angle.

"Good morning," said the young man pleasantly enough.

"Humph," snorted Fowler. "Can't say that it is."

"Something I can do for you, Mr. Fowler?" asked the blond young giant cordially.

"You can get out of my way and permit me to have a look at that what-ever-it-is stored on my property in my warehouse," snapped Fowler.

The young man smiled. "You insist on forgetting that my boss, Mr. Santospedros, has rented section 25 from you, Mr. Fowler. It isn't your property until the rental expires. The rental won't expire for a month."

Fowler really hadn't expected to be permitted to pry into the strange object occupying section 25. But there hadn't been any harm in trying. Now something else occurred to him, and he glared at the blond young giant suspiciously.

"Say, when did you get here this morning? I didn't see you arrive, and neither did my watchman," Fowler declared.

The blond young man grinned. "I didn't arrive this morning. I've been here ever since this object was placed in section 25."

"You mean to say you've been staying here straight through?" Fowler demanded. "You mean to say you were here last night, the night before, yesterday, and now today?"

The young man smiled and nodded.

"That's ridiculous!" Fowler snapped. "Look at you. Clothes neatly pressed, clean shirt, not a trace of a need for a shave. Don't tell me you've been living in a dirty warehouse for almost three days without getting mussed up and dirty!"

The young man continued to grin, shrugging.

Fowler suddenly had another idea. He'd find out about last night.

"Did almost eighty people come here last night to, ah, work on that what-ever-it-is there?" Fowler demanded.

The young man nodded. "Seventy-five was the exact number, I believe. Your night watchman admitted them."

Fowler was taken slightly aback. "What could that many people find to work on in that, that tall thingamajig behind you?" he demanded bewilderedly.

The young man grinned even more broadly. "Nothing," he admitted. "Nobody said they worked on it. The person who's to work on it should arrive tonight. Mr. Santospedros has finally located a man he thinks capable of fixing it."

Lucius Fowler digested the words. Then he bleated: "What?"

The young man nodded. "That's right. The chap will probably be here to fix it tonight."

"I don't mean that," Fowler snapped. "I mean the seventy-five people who came here last night. The seventy-five people who, by your own admission, didn't work on the thing." He took a deep, indignant breath. "What about them? Why did they come here?"

The blond young giant grinned.

"Maybe they just wanted to look at it," he suggested. "Or maybe Mr. Santospedros wanted them to look at it. And maybe it's about time that you stop asking questions and get back to your office where you belong."

"Listen here—" Fowler began.

The smiling young man put a massive hand gently on his chest.

"Run along," he said amiably.

Sickly, Fowler realized that there was nothing to do but run along. Without another word, or a backward glance, he turned and stalked off. He thought he heard the young man's amused chuckle follow behind him....

THE rest of the day passed torturously for Lucius Fowler. For not only was his mind beset with plaguing, unanswerable questions of the most tantalizing variety, but his suspicions were now busily at work.

"I might be playing right into the hands of a ruthless gang of cutthroats," Fowler thought worriedly. "How do I know that they aren't gunmen? Or even saboteurs? I ought to call the police. I ought to do something."

But as the day passed, Lucius Fowler didn't do anything except worry perhaps even more. He arranged to have another night watchman come on that evening to take old Charlie's place. The man who agreed to this temporary job was Pete Passondo, the day hamburger man at a lunch counter in the neighborhood.

"Whatsa matta with Cholly?" Pete had demanded. "He'sa no work no more?"

"Not this week, anyway," Fowler explained. "I'll probably hire him back next week, when he's resolved to go a little easier on that yocky-dock he swills."

"Okay," Pete said. "As long as I'ma not hurt Cholly. I'lla be there. Justa for a week, though."

"Just for this week," Fowler agreed. Then he told Pete when he was to start, and told him about the people who would probably present cards bearing the name of Mr. Santospedros. "You let them in, understand?" Fowler said.

"Sure, they gotta a card like that, I letta them in," Pete agreed. "Whattsa the name again?"

Fowler told him the name again, and Pete agreed to report at the correct time. That was that. Now Fowler was free to return his worries to the matter of the mystery in section 25. This he did completely, doing no further work until five thirty and time to go home.

As he left his office Fowler realized that he hadn't come any nearer to making up his mind about what to do concerning his worry. And he resolved determinedly to have it out, somehow, the following day. It was little consolation to him to realize that he'll probably spend another sleepless night over it again....

FOWLER'S contemplated sleepless night became a thing of more tragic significance when he arrived at his apartment around six o'clock. The telephone was ringing insistently as he entered the hallway.

When he answered the phone, a completely unfamiliar voice demanded to know if he was the Lucius Fowler who owned the Western Scenery Warehouse which employed a night watchman named Charlie Cooper.

"Yes," Fowler answered, frowning. "I'm the same person. Why?"

"Well, you seemed to be the only one we could notify, Mr. Fowler," said the strange voice. "He had no living relatives, it seems. We don't know any of his friends, and we found your name in his wallet on his paycheck. We figured you might know what to do."

Fowler had a sick sensation in the pit of his stomach. He knew what was coming. But he asked: "What's this all about? What's wrong?"

"I'm his landlord," said the voice. "We found him in his room this afternoon, dead. He was in bed and had died peacefully. It must have been a quick heart attack."

"You mean," Fowler gasped quickly, "that old Charlie Cooper died this afternoon?"

"That was the coroner's verdict. Heart attack," said the voice. "What'll we do about him?"

"Take him," Fowler said miserably, "to a nice funeral home. Don't worry about the bill. I'll take care of all his expenses. Try to find out if he's got any relatives. I'll pay for that search. I'll be at my office tomorrow morning. Call me there and let me know what you've done."

"Sure, Mr. Fowler," said the voice. "I'll do that. Thanks. He was a nice old guy."

"Yes," Fowler admitted wretchedly. "He was a nice old guy."

As Fowler walked morosely into his living room to pour himself a drink, he knew even more certainly than before that there would be no sleep for him this night.

He almost filled the glass with scotch, and fizzed in barely a jigger of soda. But he knew that strong liquor wasn't going to help much....

WHEN his telephone jangled again, it was almost midnight. Fowler had consumed a considerable number of drinks, but he was far from being unsteady. His mind was still perfectly clear, too perfectly clear.

He answered the telephone, and the instant the voice on the other end of the wire sounded, Fowler knew his caller was Pete Passondo, the fellow he'd gotten to take Charlie's shift while the old night watchman was being disciplined.

Pete was volubly excited.

"Mister Fowler," he said. "You gotta get down here righta way. I don'ta like whatsa go on around thisa place a bit!"

"What's wrong?" Fowler demanded, trying to keep his voice calm.

"I'ma let fifty, sixty people into the warehouse," Pete said. "They alla gotta cards like you tole me about. And then, justa little while ago, I'ma let another one in. He'sa gotta bag is foola tools. None of the others isa have tool bags. But this guy's gotta bag fool, see?"

"Sure, sure," Fowler said. "For Heaven's sakes, get on with it!"

"Well, I'ma mind my own bizzinuss, see. I'ma not go back there to section twent'a'five, see? I'ma think old Cholly can take care of anything whatsa come up back there."

Fowler cut him off. "Old Charlie? What do you mean, old Charlie?"

"He'sa one of the peoples who comes witha card likea you tole me about. I'ma surprised, and ole' Charlie isn'ta say a word to me. He'sa justa hand me the card an' it reads like the others. So I letta him in."

A cold sweat stood out on Fowler's forehead. Old Charlie came there. With a card from Mr. Santospedros, just like all the other people with cards. But, but it was impossible that old Charlie could be in that warehouse now. Utterly impossible!

With a voice that cracked, Fowler demanded, "How long ago did old Charlie arrive?"

"Justa 'bout an hour ago," Pete answered.

An hour ago! But that was—No! It wasn't possible. Old Charlie was dead. Charlie had died sometime that afternoon. It was now almost midnight. He had died in the afternoon. He couldn't be at the warehouse at eleven. It was preposterous. It was—

But Pete was babbling on.

"But that'sa not important," he said. "What'sa important isa the Beeg Light!"

"Big Light?" Fowler croaked hoarsely. "What Big Light!"

"The Beeg Light that'sa light up alla back of the warehouse like it was fire, or something," Pete said excitedly. "Thisa Beeg Light scare me, and I runna back along the outside of the warehouse until I can look inna the windows. I think maybe fire isa break out. But it isa no fire. It'sa the thing in section twent'a'five. The beeg theeng that'sa stored there."

"The—the object in section twenty-five?" Fowler choked.

"Yes. That'sa what'sa make the Beeg Light. It'sa so bright I'ma not able to see it. It'sa just one beeg glare."

"What was it?" Fowler gasped.

"That'sa what I'ma say. I'ma not able to tell what's it is. It'sa too bright!"

"But what," Fowler implored, "about the people you let in? What about the people who showed you the cards? Were they around the thing?"

"No. That'sa nother things which isa scare me," Pete exclaimed. "They'sa alla gone. Not one of them isa there, It'sa like they's disappeared!"

"How long ago did all this come to your attention?" Fowler managed.

"Justa four, five minute ago," Pete said. "I'ma get scared. So I run to drugstore anna call you right queek!"

"Hang on!" Fowler begged. "Go back there to the warehouse and stand by. I'll be right down!"

THE cab which brought Fowler to the warehouse screeched up in front of the place exactly fifteen minutes after Pete's telephone call. Leaping from the vehicle almost before it had completely stopped, Fowler threw the startled driver a five dollar bill.

The lights of the warehouse office were on. But Pete Passondo was standing out in front, obviously waiting for Fowler.

"Get out your keys, Pete!" Fowler gasped. "We're going back to section 25!"

As they hurried through the front office, Fowler paused long enough to throw the central lighting switch which illuminated the entire length of the warehouse storage rooms. Pete's sigh of relief at this was lost in the jangle of keys which Fowler had taken from him.

Then they were in the warehouse and dashing down the block-long aisle toward the back of the place and section 25. Behind him, Fowler heard Pete's breathless and startled exclamation.

"The Beeg Light, she'sa gone!"

Fowler had already noted this much. If there'd been a light of the intensity described by Pete over the telephone, he'd have noticed it even as he entered the warehouse front office. But he held his breath and hurried on.

At section 25, they came to an abrupt and startled halt.

Section 25—the place where the mysterious whatever-it-was had been stored—was totally vacant.

Pete muttered a brief prayer. Fowler was too shocked to gasp. He could only stare gawpingly at the vacant sector.

"Looka, there'sa the bag foola tools!" Pete suddenly exclaimed.

And then Fowler saw it. A small tool bag, open and on the floor at about the center of where the mysterious storage object had been. Just the open tool bag, and nothing more.

Slowly, Fowler moved over to the bag. Pete followed cautiously behind him. Fowler stooped and peered into the bag. Save for a small locksmith's bore, there was nothing else inside.

Stooping down beside the bag, Fowler suddenly saw the small deposit of white, glistening dust. It was scarcely more than a handful, but its glitter was amazing.

Fowler picked up a little of it. He held it in his hand and let it sift through his fingers. It seemed like the dust that pearl shavings, mother-of-pearl shavings, that is, would make. Fowler straightened up, the expression on his face unreadable. He was thinking of old Charlie Cooper who had died that afternoon, and yet was here this evening. He was thinking of the single locksmith's tool left in the bag. He was thinking of Mr. Santospedros, and the Big Light that the mysterious storage object had made. A glitter that must have been that dust magnified a thousand times as it appeared on the surface of the huge object in section 25.

Locksmiths, locks, doors, gates.

Dust, pearly dust. Dust that had been scattered by the locksmith's bore.

Locks, bores, doors, gates? Dust, pearly dust.

Pearly Gates!

Chill fingers softly stroked their way along Fowler's spine. He was thinking of old Charlie Cooper again, and of the others, considerably more than a hundred of them, who had come to the warehouse with a card like the one Pete said old Charlie brought.

A card that bore the name Santospedros.

Santospedros. Santos Pedros. In Latin, Santos Pedros was a name. The name of the keeper of the Pearly Gates—Saint Peter.

Fowler realized that whatever minor repair job which had been necessary on the Pearly Gates, had probably been taken care of by the locksmith. And he realized, fuzzily, why Saint Peter, or Mr. Santospedros, had stored them while he sought for the right locksmith to do the job. Stored them here in the Fowler warehouse.

The job was done. The gates were gone. But while they'd been here in the warehouse, their utility couldn't cease. Hence the people with cards admitting them to the warehouse, and the Pearly Gates.

In spite of the utter nervous breakdown which he already felt descending on him, Lucius Fowler managed to smile faintly. Old Charlie had come with the card. Old Charlie Cooper had been admitted. Fowler was glad the old duffer had made it....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.