RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

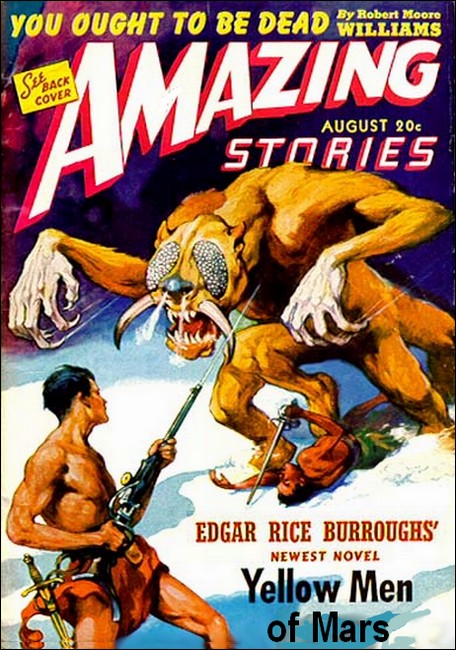

Amazing Stories, August 1941, with "The Man Who Got Everything"

There was real power in this little box. Its

possessor

could literally ask for the world on a plate and get it!

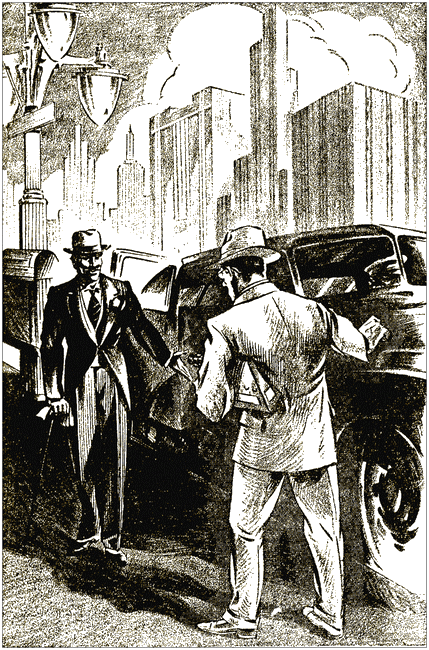

"Take it," he said with amazing generosity. "I give you the car as a gift."

WHEN Mr. Gluge rose, he peeked out from behind the shade of his bedroom window and saw that the day promised to be a gloomy one. This filled him with infinite satisfaction, and he went about his dressing almost cheerfully. On gloomy days people couldn't very well smile and simper. Mr. Gluge detested smiling, simpering people. Mr. Gluge was a bill collector.

Where most bill-collectors looked upon their calling as nothing more than a job—a means of earning a living, to Mr. Gluge the daily tracking down of debtors was as strong whisky to a drunkard. He collected bills because he loved to. Mr. Gluge exulted every time he could make one of his harassed victims pay, and pay, and pay.

The apartment to which Mr. Gluge went for this morning's collection was far in the rear of a ramshackle tenement dwelling. Mr. Gluge was forced to climb a four-flight walk-up to reach the dirty little room; and by the time he knocked on the paint-peeled door, he was determined that this fellow would get a double-barreled collection treatment.

A white-faced old man, wearing horn-rimmed glasses, opened the door and stuck his head out.

"Yes?" he asked. His voice was as thin as his face.

Mr. Gluge shoved his way into the room, his sharp eyes noting everything in the tiny hovel. A dirty, unmade bed; an electric stove on which sat an empty pot; and on the other side of the room, a long table filled with chemicals, wires, and tubes. Mr. Gluge turned to the white-faced old man.

"You Doctor Homan?"

"I am."

"You owe a bill, long overdue. Allied Chemical Company. Amounts to over a hundred dollars!" Mr. Gluge was glorying in the particularly harsh note he had placed in his voice. Glorying in the trembling that suddenly seemed to affect the old man. The old man sat down on the edge of his bed, as though his legs would no longer support him.

"Well?" Mr. Gluge demanded. He was very good with his emphasis on that word. A question of long practice.

"I... I," began the old man, faltering.

"You can't pay, eh?" Gluge broke in.

He looked meaningly around the desolate little room. "Seems obvious," he added.

The old man nodded, swallowing hard.

"No," he admitted. "I'm afraid I can't. If I had a little time, just a few weeks, perhaps a month, I—"

Mr. Gluge snorted.

"An old whine. Won't work. Had plenty of time." He moved, as he spoke, over to the long table on the other side of the room. The old man was watching him fearfully.

Gluge looked at the mess of wires, tubes and chemicals on the table.

"What's this hodgepodge?"

There was a frayed, faint fragment of pride in the old man's voice as he answered.

"My work. My experiment. That's why I say, a few weeks, perhaps a month. It will be completed then. It will—"

He was cut off sharply as Mr. Gluge broke in again.

"This junk?" His voice was scornful. He ran his hand through a litter of papers, then pulled it swiftly away, as though it might be contaminated. "Bah!"

There was really no reason for Gluge to remain. On finding that the fellow couldn't pay, he should have let it go at that. But Mr. Gluge was enjoying himself, immensely. He tarried.

"That little box," the old man said suddenly, "that small square machine on the end of the table. Please let me tell you about it. I hope to make much mon—"

Mr. Gluge's eyes shot to the end of the table. He moved to the box, picked it up.

"This thing?" he scoffed. "Valuable?" Then, suddenly, a crafty gleam came into his eye. "Valuable, eh?" he repeated.

The old man nodded, like a child eager to please a brutal teacher. He got up and moved over beside Gluge.

"Yes, yes it's very valuable. Oh, if you could just give me an extension. I'm sure—"

But Mr. Gluge had tucked the box under his arm. He was smiling unpleasantly.

"For a while," he said, "you had me fooled. I thought you didn't have any possessions. I'll just take this along. We'll hold it for thirty days. At the end of that time it'll be sold, unless you pay up your bill!"

The old man looked suddenly very sickened. His thin hands clung to the edge of the table, as if to keep him from falling. His eyes were wide with horror, and his mouth opened and closed while he tried to find words.

"No," he managed finally, "no, you can't take that!" His voice squeaked hysterically. "It's all I have! I'd never be able to pay you if you took that!"

But Mr. Gluge, smiling a tight smile of triumph, was writing out a receipt. He left the old man with his head in his hands, muttering inaudibly, sitting on the bed. The box was under Mr. Gluge's arm as he stepped out into the street.

IN less than half a minute after that, Mr. Gluge collided

heavily with another pedestrian—a fellow who had been

walking along, unnoticing, reading a newspaper.

It was all Gluge could do to keep from dropping the box under his arm, all he could do to retain his balance. His face purpled in instant wrath. Here was a perfect way to begin the morning—an exchange of sharp words with a fellow human!

"Damn you, Sir!" Mr. Gluge exploded. "Might pay some attention to where you're going!"

The person with whom he had collided was a short, dapper, moustached fellow. He blinked at Mr. Gluge, and then, suddenly, smiled.

"Sorry, old boy. Wasn't looking, must admit." He fished into his hip pocket, drawing something forth. "Here," he pressed a flat object in the startled Mr. Gluge's hand. Then, before Gluge could open his mouth, the fellow bent his head once more over his paper and moved off down the street. For fully a minute, the puzzled Mr. Gluge watched the man until he was out of sight in the crowds.

Then Mr. Gluge, who had momentarily forgotten it, gave a startled cry and looked down into his hand at the object the other fellow had placed there.

It was a wallet!

For an instant, Gluge was about to shout, to light out after the fellow. But then, his natural instincts getting the best of him, he opened the thing. It was crammed full of bills!

Mr. Gluge swallowed hard, his button eyes sparkling with greed as he counted out the money. Two hundred dollars. Then Gluge fished through the wallet for identification cards. There were three or four. Gluge changed the bills from the wallet in his hand into his own wallet. He had to put the box on the sidewalk to do so. Then he dropped the other wallet, empty but for the fellow's cards, on the sidewalk. He picked up the box and moved on, looking hastily over his shoulder with every ten steps, fearful lest the fellow return.

Two hundred dollars, just like that. Given to him by an utter stranger, a chap he had snarled at! Mr. Gluge, who had collected enough money to have developed an inordinate love for it, was greatly excited.

He was looking over his shoulder for the eighth time, stepping down from the curb to cross the street as he did so, when a deafening, blasting, frightening noise split his ears. Gluge was conscious of brakes screeching protestingly, and then, heart in his heels, he saw that a huge limousine had almost crushed him to the pavement, had stopped less than three feet from his back!

A man was climbing wrathfully out of the back of the long, sleek automobile. A man dressed in a homburg hat, cutaway coat, striped trousers and spats. A big man, with a red face and an impressive gray moustache.

Mr. Gluge stood there stupidly, rooted to the spot by the sudden fear that had numbed him. The box was still clutched in his arm. Gone completely from his mind was the two hundred dollar gift. He was conscious only of the fact that he had just escaped certain death.

The man in the cutaway coat was speaking explosively, wrathfully, his voice bellowing.

"Damned fool. Watch where you're going, why don't you. Blank-blank dob-jazzsted moron!"

BENEATH such obvious superiority in station, Mr. Gluge was the

type to quail instantly. And he was doing so, white-faced and

trembling, when the red-faced man's tone and manner changed. He

had approached within three feet of Mr. Gluge, and the hand he

raised wrathfully, dropped. He smiled.

"Sorry, Sir. Must have been my chauffeur's fault. Must have frightened you half to death. Terribly sorry."

Mr. Gluge could only gasp for breath, sure that this was some mad hoax.

"Can you drive?" asked the cutaway-coated gentleman. Gluge managed to nod. The cutaway-coated gentleman moved to where his chauffeur sat behind the wheel of the car.

"Get out, John," he commanded. The chauffeur got out obediently.

Mr. Gluge was backing away, box still beneath his arm. He sensed attack. The red-faced tycoon halted him.

"Tut, tut," he admonished. "Don't leave. Here, the car. Take it!"

"Take it?" Mr. Gluge echoed the words in a bewildered bleat.

"Yes," the cutaway-coated gentleman insisted firmly. "Take it. A present. All yours. From me to you. You'll find the keys in the car." He turned to his puzzled chauffeur. "Call us a taxi, John. We no longer have a car."

Flabbergasted, Mr. Gluge watched them move to the sidewalk. Then suddenly hearing a raucous tooting of horns behind the limousine, and realizing that traffic was piling up behind the deserted automobile, he moved mechanically over to it and climbed in behind the wheel.

For three blocks, Mr. Gluge drove his newly acquired limousine dazedly, his face a blank mask of frozen stupor. The square box was still with him, on the seat alongside. Finally, he began to come out of the fog. Two hundred dollars and a magnificent automobile—gifts, from strangers!

Mr. Gluge's sharp mind could be dulled for just so long, and now it was whittling away at this mad enigma. This, he told himself, establishing a basic premise, was not natural, not normal. In fact it was utterly incredible. But deep inside the mind of Mr. Gluge, a certain insatiable avarice was asserting itself, swelling even above the very mystery of the situation.

Whatever had happened, Gluge was wondering, would it continue to happen? Excitement pounded in his veins. If it was not mere chance, the million-to-one odds of running into two idiots in succession, then it must have been caused by something. And if he could retain that something, these phenomenal circumstances would continue!

Something—Mr. Gluge frowned. Something—but what?

Mr. Gluge was shifting gears in the limousine, frowning in intense concentration. He threw the car into third speed, and his hand slipped down, touching the square box beside him.

And suddenly Gluge realized—the box!

Why not? Why couldn't it all be blamed on the box, he asked himself. What had happened already was too fantastic to make such a premise out of the realm of possibility. And the old man had said he would have money!

EXCITEDLY, Mr. Gluge whipped the limousine over to the curb,

stopping it there. Then he turned his attention to the box,

picking it up and examining it carefully for the first time. It

was very possible, Gluge realized, looking at the thing, that the

little old man had been working on this box without realizing

that he had already perfected it. His hands trembled as he opened

a sliding panel on the edge of the top of the box.

Looking inside, Mr. Gluge saw wires and batteries and one or two liquid-filled, capped tubes. Just that. He frowned, turning the box over on the other side. There was another panel, a button beside it. The button was in a position that indicated "on." Gluge slid back this second panel, revealing a tiny inner compartment containing—small slips of paper!

Hastily, Gluge withdrew these papers. Bending over, he saw that they were arranged in order, and had been written in a fine, precise hand. Evidently by the old man.

"By psychological ray production... should be able to bring out all... better elements in man's makeup... should clothe the individual in an aura which would make people 'want to do things for him' sheerly because of the... overwhelming impression his personality... would make on them. As yet, unable to change the basic nature of the person... this can only result in having just the best elements of his nature made apparent... every such person having such elements, submerged or otherwise... cannot change real character, as yet... just makes it appear as if all is splendid in so far as the personality of the man involved is concerned."

There was more, written on the succeeding slips of paper,

concerning the box and the old man's work on it. But Mr. Gluge

paged hastily through these, his mind thinking of other things.

So this was it! The old man had been working out this

scientific psychological hodgepodge which had somehow been

successful. This something-or-other would make people "want to do

things" for those affected by the box!

Suddenly Mr. Gluge laughed. The old man could have minted himself a fortune through this, but he hadn't used it because he considered it still imperfect, since it couldn't change basic personality outlooks as yet! And Mr. Gluge laughed again, long, loudly, and most unpleasantly. Somehow, in carrying the box around—possibly when he had been jarred in colliding with the pedestrian—the switch on the side of the box, the little button, had been turned to "on."

And in the middle of Mr. Gluge's laughter, someone opened the door to his car. Opened the door and pushed a dirty, emaciated face inside. It was, Gluge saw instantly, an old woman, her head covered by a ragged shawl. Her voice came piteously to him, muffled, almost inarticulate.

"Please, Mister, I'm hungry. A few pennies—" she trailed off embarrassedly. Gluge saw that she must have been well over eighty, saw her tattered dress and thin, shivering body. He put his hand on the square box, as if to gain reassurance from it.

"Look up," he snapped, "and stop muttering."

The old woman raised her watery eyes, blinking suddenly. Then, a strange expression wreathing her features, the old crone essayed a smile. Her claw-like fingers dug into a frayed purse she carried under her arm, brought forth three pennies.

"Here, Sir," she begged. "Please, please take them!"

Mr. Gluge's laughter was uproarious. He reached out and took the pennies from her trembling hand, shoving her back and slamming the car door shut. Then, as she stood on the curb, smiling bewilderedly, he threw the limousine into gear and roared away.

HIS laughter had died after a block.

He felt better, however, than he did before. The incident with the old crone had bucked him up considerably, reminding him of his job and the joy that it had daily held for him.

The bill collecting—there would be no more need for that now. Not that Mr. Gluge hadn't enjoyed it. But pleasurable or not, it had only paid a scant wage. And now he was on his way to millions.

Millions! The word jarred his senses pleasantly. There would be much he could do to enjoy himself with millions. And from this box, he could attain a fortune in no time at all. Ask for things, that's all he'd have to do. Ask for money, ask for fame, ask for great power. The possibilities were unlimited!

Mr. Gluge's greed was itching inside his heart, and he began to think about some immediate acquisition he might make—something by which he could try this new personality power again, profitably. He knew that everything he wanted was waiting for him whenever he cared to take it, and figured that he'd wait until the following morning before really setting out to accomplish his ends.

But as for now, Mr. Gluge was aware that it would be nice to have a little more cash than he had at present. Two hundred dollars and three cents, wasn't enough for a man of his status. Of course there was the automobile, but there was no need to turn it in for anything. Why, he could get all the money he wanted—at a bank!

Mr. Gluge knew of a bank that was less than five blocks away, and turning the limousine around, headed in that direction. It was, he recalled, a rather small bank. It probably wouldn't have a great deal of money on hand. However, he wouldn't want much. Just enough to throw around a bit until the following day. Mr. Gluge's brain was already buzzing with plans for the following day. He would have to make a list, more than likely, of the most important things to ask for. Couldn't waste time asking for trifles.

A little over two minutes later Mr. Gluge parked his limousine in front of the little neighborhood bank he had selected. He took irritable delight in parking before a fire plug, knowing that there would be nothing to fear from the policeman who'd be waiting when he returned.

Climbing out of the car, box beneath his arm, Mr. Gluge marched majestically into the bank. For an instant, as he stood in the white marble lobby, he debated as to whom to ask for the money. He could ask the president.

That would be sport. But back in the inner recesses of his brain, Gluge had a deep-rooted fear of important people. His life having been a penny-ante masquerade as a Big Shot, Gluge was rather in awe of the Real McCoy.

And then he had a brainstorm, an idea that was delightful in every respect. He would ask some quailing clerk behind the cages. Not only would he stand a better chance of getting the money, but there was additional appeal in the idea because it would catch the poor devil in a terrible hole when the cash was missed!

Mr. Gluge had a pleasant mental picture of the poor creature trying to explain that he had given, say, five thousand dollars, away to a man who merely asked for it. So looking about, Gluge selected a likely cage and strode over to it. There was no one at the window, so Mr. Gluge stepped up to the clerk without a wait.

THE clerk was a bespectacled, pink-cheeked, earnest young man.

Mr. Gluge put a snarl in his voice.

"Hello, my stupid looking young dolt!"

For an instant the clerk seemed astonished, then, as Gluge caught his eye, the young man grinned happily.

"What can I do for you, Sir? Just name it, Sir. Anything at all." The clerk was eager to please. He seemed almost trembling in the fear that Gluge would not let him help.

Mr. Gluge encircled his right hand more firmly around the precious box.

"I want money, you snivelling nincompoop. All you have in your cage!"

The youth beamed.

"Yessir. You bet. I was just about to suggest that maybe you'd like some money!" He laughed foolishly, and swiftly began to toss stacks of currency into a paper bag beside his elbow. At last he shoved the bag through the grill-work to Gluge.

"That's all I have here. There's more, though. I'd be only too glad to—"

"Go to the devil!" Gluge broke in with intense satisfaction. "I have all I need!" He looked frostily down his nose at the clerk and wheeled triumphantly away from the cage.

And at that moment commotion broke forth!

It came from the far end of the bank, almost a hundred feet from where Gluge stood. Loud shouting, and one or two shots. The noise of the gunfire was still ringing in the vault-like lobby, and Mr. Gluge stood rooted in fear, currency clutched in one hand, the box under the other arm.

Three men in dark coats, light fedoras, and with handkerchiefs over their faces, were backing away from the far cages. Backing away toward Mr. Gluge and the door.

Bandits!

Mr. Gluge's heart was pounding wildly enough to serve as a motor for an ocean liner. His money—what if the bandits saw it. Desperately, he tried to conceal the package behind his back. He would have dashed for the door, but his knees refused to respond to his brain commands. And the bandits were still backing toward him!

It was while he was trying to stuff the paper bag of currency beneath his coat, that Mr. Gluge suddenly stopped short. Why, there was no need for fear. He had been acting on inborn greed rather than common sense. He could always get more money—just by asking for it.

And for the first time in the past minute, Gluge remembered the box beneath his arm. And as he remembered it, an inspiration flashed upon him irresistibly. The box—why, with it he could route the bandits. There was nothing to fear. He would have complete power over them!

Mr. Gluge thought of the beautiful irony of it. He could make himself a hero. He couldn't resist the temptation. Everything was happening too rapidly for further decision. He stepped up behind the closest of the bandits, who was now less than four feet from him. The robber was, with his two companions, backing rapidly toward the door, gun covering everyone in front of him. They hadn't noticed Gluge, yet.

In the split-second that it took Mr. Gluge to act, he realized that the holdup men undoubtedly had someone covering the front of the bank. But he could attend to that fellow later.

Mr. Gluge knew that the eyes of every frightened bank worker and customer were upon him, and he made his voice loud enough to warrant the heroic occasion, tapping the bandit on the back as he bellowed a single strident sentence.

In less than two seconds later, while three guns blasted deafeningly, Mr. Gluge felt hot lead searing through his entrails, and felt himself falling, falling. He was dead before he hit the floor...

THE car in which the bank bandits were speeding along the

highway took a sharp turn. The man at the wheel spoke over his

shoulder to the three in the back.

"Yuh wasn't smart, bumping that guy. Every cop this sidda hell will be on our tail now!"

The bandit in the center of the back seat answered for the other two.

"Jeeeze, we couldn't help it. The guy musta been a loony. Five grand inna paper sack, and we pick it up off his body when he hits the floor."

"What did he look like?" the driver asked over his shoulder.

"Didn't get no chance to see his face. Wasn't time," said the hood in the center of the rear seat. "We just hear his voice, and what he sez—and we turn and plug him," he explained. "It was just like we couldn't help ourselves."

"Yeah?" The driver sounded skeptical. "What did he say?"

The hood in the back frowned, trying to remember exactly.

"Oh yeah," he said finally. "He sez 'let me have it, yuh swine!'"

"And yuh let him have it, eh?" the driver said caustically.

The hood in the back nodded.

"Yeah," he agreed. "We sure did. Both barrels!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.