RGL e-Book Cover©

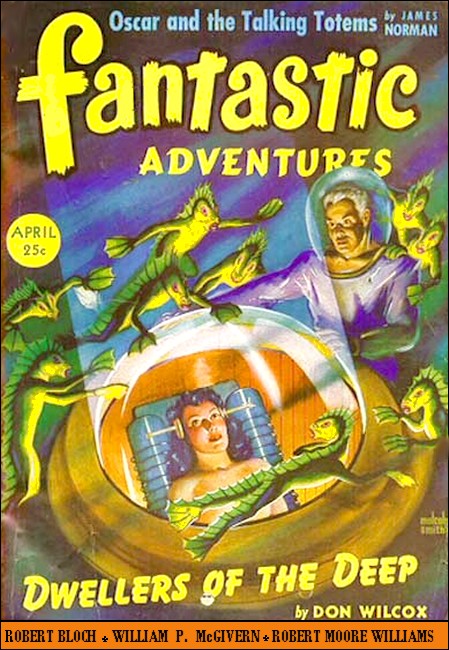

First published in Fantastic Adventures, April 1942

This e-book edition: Roy Glashan's Library, 2018

Version Date: 2022-08-05

Produced by Matthias Kaether and Roy Glashan

All original content added by RGL is protected by copyright.

Click here for more books by this author

Fantastic Adventures, April 1942, with "The Legend of Mark Shayne"

"You must write more songs! You've got to!"

These songs were really ghost-written—and

Mark Shayne sold them as his own creation.

TO those who know anything about that stretch of Mid-Manhattan called Tin Pan Alley, and even to those who dance, sing, and listen to the tunes that pour forth weekly from that madhouse of American melody—the name and legend of Mark Shayne must certainly be familiar.

Shayne, composer of Baby, Why Do I Care?, Heartbreak Melody, Just Ask Your Heart About Me, and countless other hit songs far too numerous to mention, was as much a part of musical America as Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, or George Gershwin.

He was, in fact, looked upon along the Great White Way as not only a top-notch tunesmith, but a sensationally stellar success story. Broadway wise men could recount to you, even to the date and year, the thrilling episode in the first rung of the ladder in Shayne's career—the "break" that took him from the ranks of obscure publicity men and started him toward the proverbial Fame and Fortune he was later to attain as a Great Composer.

The "break" occurred a little over ten years ago, just about the time that the depression had settled over the nation to stay a little while. The financial gloom that had blanketed the United States was felt everywhere, and—as Variety can tell you—nowhere more than on Broadway.

Only the most venturesome producers were risking their bank rolls in the theater, and the majority of those who did wound up inevitably in the poor house. The darkened theatrical palaces along the Main Stem were like mausoleums in a cemetery, and the lightless signs outside them were as markers to grave plots.

Actors, agents, singers, dancers were starving to death with what became monotonous regularity. Theatrical productions, as rare as flowers that bloom in the fall, became coveted plums over which thrushes and thespians alike were only too eager to knife one another.

In Mark Shayne's racket—publicity—conditions were no better. And if it hadn't been for Shayne's very early training in the art of cutting a friend's throat, he might never have landed the job to publicize the small musical comedy, Yipeee!, which opened rehearsals bravely in the face of conditions.

The cast for Yipeee!, even to the chorines, were all working on a when-and-if basis. In theatrical parlance, when-and-if meant that they would get paid for their efforts only when, and if, the show made money. This was, of course, in blatant disregard of the wishes of Equity—that worthy organization designed to protect the rights of show people. But with times as they were, Equity occasionally closed its eyes in such matters and breathed a prayer for the good luck of its children.

Needless to say, the publicity services of Mark Shayne were secured on such a when-and-if agreement. This was all right with Shayne, however, for he was working while the rest of his colleagues were subsisting on canned dog food.

Van Evans Garth was the Producer of Yipeee! Undoubtedly you've read of Garth in the history of the theater. Called the Grand Old Man of the stage, he had been at the peak of his career in the middle Twenties. And during the year in which Yipeee! was staged, the Grand Old Man was definitely riding a sled to oblivion. You'll recall that he died three years after Yipeee!.

Unfortunately, Van Evans Garth was thinking in terms of the gay Twenties when he produced Yipeee! The musical comedy was as dated as your morning coffee. The costumes were behind times, the story had been told too often to seem fresh, the songs and lyrics were equally, or perhaps especially, lousy.

The cast was faintly aware of all this as rehearsal weeks droned on. But their loyalty to the Grand Old Man, and the fact that they had nothing else, kept them plugging along. Even Mark Shayne stuck by the show, although he had never won prizes in school for loyalty.

But while Shayne stuck by, Shayne looked around and privately arranged to sue the Grand Old Man for back salary just in case. There is no doubt that Shayne would eventually have sued, except for what occurred four days before Yipeee! was to open.

IT was after a dismally frantic rehearsal that Shayne

buttonholed the Grand Old Man. They were alone in the theater

when Shayne spoke his mind.

"Listen, Van," Shayne said sharply to the tired old man, "this thing stinks. No matter what you do to it, or try to do with it, it smells up the stem. You'll close in a night."

Van Evans Garth winced at the brutality of the criticism. He shook his white head wearily from side to side.

"Don't say that, my boy. There are still three rehearsals. Other shows I have produced have seemed as tedious before the opening. It is just your nerves."

Shayne's sharp features twisted nastily.

"Nerves, hell," he spat. "It stinks no matter how you look at it."

"You are to publicize it, not criticize it," the old man reminded him wearily.

"What stinks more than anything else," Shayne went on, ignoring him, "is the music—plus the lyrics. And that's what I'm talking to you about. You're gonna throw out the music and the lyrics!"

"What?" the old man looked at Shayne as though he had lost his mind. "Three nights before the show opens you want me to throw out the lyrics?"

"And the music," Shayne reminded him. "You are going to use my music and my lyrics."

The Grand Old Man shook his head sadly.

"You are delirious, my boy. You are not a musician, and you know nothing of lyric writing. You have not been eating enough. You are delirious. Here," he fished into a worn wallet in which there reposed two five-dollar bills, "I have but ten dollars. Take five of it, my boy. Get a good meal today and tomorrow. Opening night I will have something for all of you."

Shayne took the bill.

"Thanks," he said. "But you are going to use my songs and my lyrics in this show—no matter what it does to the last three rehearsals. And if you don't," he paused significantly, "I think I can give the newspapers something in the way of a story about an ex Big Time Producer who has a wife in the nut house."

The color drained from Van Evans Garth's face. He stared in wordless horror at his publicity man. His hands began to tremble visibly. The muscles in his mouth twitched.

Shayne brought forth a portfolio.

"I have the new music and lyrics here," he said. "Suppose you start going over them now?"

The Grand Old Man's hands were still shaking badly as he reached for the portfolio....

THUS, the Broadway wise men will tell you, Mark Shayne got

his first "break." But of course there are certain elements, such

as the threatened shame the publicity man held over Van Evans

Garth's head, that never came to light. The Broadway wise men

knew nothing of this, and their Shayne Legend recounts only that

the brilliant young composer, seeing the weakness of the music

and lyrics in Yipeee!, persuaded the Grand Old Man to

substitute the Shayne epics at the last minute. And the sages of

the Main Stem are also sadly lacking in another bit of

information concerning this first episode in the Shayne Legend.

They didn't know—as the Grand Old Man had known—that

Mark Shayne was definitely not a musician, and that he knew

nothing of lyric writing.

They do not know that on the same night Shayne "persuaded" Van Evans Garth to use new music and lyrics in Yipeee!, he made a later visit to another white haired old man. This second old man was an Austrian professor of music, starving in a New York tenement flat. His name was Johann Gelder, and he was pathetically, breathlessly, on edge when Mark Shayne burst into his dirty little room....

JOHANN GELDER had been working on some musical

arrangements when Shayne's knock sounded on the door. Heart

hammering in excitement, the old man rose and crossed the room.

Shayne was standing there grinning when he opened up.

"You have seen him?" Johann Gelder asked excitedly.

Shayne entered, threw his hat on the clean, ragged, little bed, and nodded.

"Yeah, I talked to him. I convinced him that he ought to use the new tunes and lyrics. They'll be in the show when it opens."

There were stars in Johann Gelder's eyes. There was overwhelming gratitude in his heart. This was his chance—at long last!

"But there's one condition, of course," Mark Shayne declared. "Since no one in this country knows anything about you, and especially since your name means nothing on Broadway, those tunes and lyrics will have to be presented under my name."

Johann Gelder looked at Mark Shayne uncomprehendingly.

"But why am I not to be given credit for my songs, my lyrics?"

Shayne gave the older man a look of intense exasperation.

"It's like I told you," he blazed. "Names mean a lot. Yours is unknown. To put the first few tunes of yours over, it'll be smarter to use a name that's known a little around the Main Stem—my name!"

Johann Gelder shook his head sadly.

"But it is so strange."

Shayne turned toward the door.

"All right. I'll tell Van Evans Garth that you don't want the tunes in his show."

"No! No!" Johann Gelder cried. "I do not mean that, Mr. Shayne. Do as you see best, of course!"

Shayne turned back, grinning.

"Now you're using your head," he said. "There's a little agreement here I had drawn up, just a gentleman's contract, really. I'll want you to sign it. It'll be sort of a partnership affair. You'll write the tunes, I'll handle them for you."

Johann Gelder nodded docilely, as he was to nod in much the same manner during the decade that followed.

BACK numbers of Variety will tell you that the

musical comedy, Yipeee! didn't fold after its first night

opening. Actually, it lasted five performances. The cast and Van

Evans Garth were left penniless for their efforts after expenses

had been met. But four of the songs from the show were picked up

by bright-eyed music publishers and contracted for with their

"composer" Mark Shayne.

Of these tunes, all made money, and two fell into the category of "smash hits." Mark Shayne's name as a composer was born over night. And Johann Gelder was especially pleased with the hundred-dollar check Shayne bestowed on him. It kept the old Austrian composer for six weeks, during which time he turned out another song.

Shayne moved from his cheap lodging house into a terraced apartment on Park Avenue. Those were the days when terraced apartments were being given away with newspaper subscriptions, of course. But even at that, Shayne wasn't living beyond himself. After all, the songs were bringing in close to a thousand dollars a month.

For the remainder of the year, Mark Shayne contented himself with two more hit songs. One of them, Baby, Why Do I Care?, is still sung today. You began to see Shayne's name in all the Broadway columns, and his home town, a tiny hamlet in Iowa, proudly advertised on a billboard beside the state highway that ran through the village that it was the birthplace of the celebrated Mark Shayne.

In January, Mark Shayne took Johann Gelder out of his dingy tenement house and placed him in a tiny country cottage. The old man was pleased to the point of tears of gratitude. He had fresh air, and rolling hills, four rooms, and a piano. It cost Shayne fifty dollars a month—seventy-five for food and incidentals. But after all, he was wise enough to know the value of keeping his investment out of sight and healthy.

Two years passed, bringing with them three more hit songs from Shayne. He had turned down three Hollywood offers to do the scores for musical comedy films. It was at the end of the third year that Van Evans Garth died. The record on the coroner's ledger stated that the Grand Old Man had passed away from malnutrition. Mark Shayne was one of his pallbearers.

And the stone heart of Broadway was touched to see the young composer choking back his tears as he assisted the man who gave him his first break to his final resting place. The Shayne Legend has it that the successful young composer's greatest grief was that he had known nothing of Garth's plight, and could easily have saved him if it hadn't been for the Grand Old Man's fierce pride.

Another piece of the Shayne Legend recounts how, just before Garth's casket was closed, Mark Shayne quietly placed a gold-mounted five-dollar bill in the old producer's clasped hands—symbolizing the aid which the Grand Old Man once extended to Mark Shayne. It was all very touching, and was the subject of conversation for weeks along the Main Stem.

But the tide moved on, and Van Evans Garth soon became forgotten, while Mark Shayne went on to greater and greater successes. His musical comedy, This Is the Life, became the most talked of show since the turn of the New Deal.

JOHANN GELDER, happy with his fresh air and rolling hills and

hundred dollars every month—Shayne had upped the ante

twenty-five dollars after the musical comedy hit—continued

to turn out some of the catchiest songs of the nation.

People mentioned Mark Shayne in the same breath with Victor Herbert and Johann Strauss. And the young composer modestly admitted to being one of the greatest musical figures of the century. In 1937, Mark Shayne paid income tax on five-hundred-thousand dollars. And in the following year that figure was doubled.

Then, for the first six months of the next year, Johann Gelder didn't write a single piece of music. Shayne, who had contracts calling for three songs a year, was positively furious with the old man. He made a special trip to see him.

Johann Gelder had aged considerably and showed it. Even the fresh air and sunshine hadn't been able to stay the ravages of what ailed him. His wrinkled features were torn with anxiety, grief, and torment as he faced Mark Shayne.

"It is not that I do not try, Mr. Shayne," the old man said pleadingly. "It is not that I am ungrateful for all you have done for me. But music I no longer feel. Gay tunes no longer come from my heart. My people, in Austria, surely you read of the misery that has engulfed them!"

Shayne's sharp features were wrathful.

"To hell with that noise!" he snapped. "We have a contract that your damned slop sentiment can't break. How'd you like to go back to the gutters where I found you, eh?"

Johann Gelder sat down beside his beloved piano, head in hands.

"I cannot," he sobbed. "I cannot."

Ice was beginning to form in Mark Shayne's veins. He felt a terror which he was wise enough not to reveal before the old man. Changing his attitude a little, he put his hand on Gelder's shoulder.

"Turn out a tune around that, then," he said desperately. "Put all you feel into music."

Johann Gelder looked up slowly. Behind the pain in his old eyes there was a glowing fire.

"You are right," he said softly. "I know you are right. I shall try!"

Mark Shayne drove back to New York two days later with another song, and grave misgivings. He went immediately to the office of his publishers.

"Look," Mark Shayne told John Colder, head of the publishing organization, "it's like this, John."

And then Shayne went on to say, with much dramatization, almost exactly what Johann Gelder had said.

"There's no more real happiness in the world today, John," Shayne said, while the sweat rolled down the neck-band of his twenty-five dollar shirt. "There's no real laughter. People are being killed, oppressed. Nations are being overrun. I can't find it in me to write the light, happy stuff anymore, John."

It may be said much to John Colder's favor, that the round little music publisher had no particular liking for Mark Shayne. Now he eyed him rather coldly.

"But you've got a contract, Mark," he reminded him. "We have money, plenty of it, tied up in the advance plugging of your next tune. We have to have it. No matter how you feel."

"Have your boy play this," Mark Shayne said, extending the music manuscript and holding his breath. "It was all I could find to write."

An employee played the song, and Colder listened. He asked that it be played again. He looked over the lyrics, then he looked up at Mark Shayne dubiously.

"You've never written a tune like this before," he said.

Mark Shayne felt cold all over.

"You mean it's not—" he began.

"I mean it's magnificent," Colder said quietly.

IT was magnificent. It was a sensation. Undoubtedly you

heard it. It was called, Now They Are Left Behind. It was

Johann Gelder's peak, his masterpiece.

It was Johann Gelder's last song. He died, from grief and old age, two weeks after its publication. And Mark Shayne, riding on the crest of the masterpiece he hadn't composed, came close to going insane.

Shayne had made millions from Gelder's songs, but he had thrown most of it around like rice. Even Now They Are Left Behind, although it was minting money, wouldn't take care of Shayne's style of living for long. There had to be more tunes, other songs. And where was he going to get them?

Johann Gelder had taken Mark Shayne's talent with him to the grave.

He had money, fame, he could hire another ghost writer perhaps. Shayne thought desperately about this angle. There should surely be another starving composer around New York who would be only too glad to ghost songs for Shayne. But he knew of none. And the successful composers, naturally, couldn't be touched. Shayne couldn't even risk hiring a starving composer, for if that ghost's songs were bad—and Shayne had little ability to tell a good song from a poor one—it meant a staggering loss in prestige.

Shayne began to drink more heavily than before. Perhaps he drank in an effort to find a way out of his dilemma. Or perhaps he drank to shut out the songs of Johann Gelder which came to him wherever he went.

He tried to compose himself. He had learned to play the piano during his decade of fame. But his efforts were miserably futile. And another four-month period was running out. A four-month period which would mean another song.

John Colder gave him two additional months to get a song to him. Two months beyond contract stipulations. And then he was forced to break the contract. The word was around the Main Stem that Shayne was slipping, drinking himself into oblivion.

And then there was the night that Shayne got roaringly drunk in a small dive in Greenwich Village. Somehow he ended up in a tiny, unknown cafe. There was a woman there. Not the type of blonde beauty that Shayne was used to having around him. This woman was old, thin, gray, and haggard. Shayne found himself buying her drinks and babbling drunkenly about his troubles. Shayne, of course, was hardly conscious that he was revealing as much as he was until the old crone's voice came reedily to him.

"Then it is this man who has died you'd like to see?" she asked.

Shayne laughed in dismal drunken morbidity.

"Thash right. I'd like to see my ghost. But I can't, 'cause he'sh a ghost—get it?"

"Perhaps he can be called," said the old crone.

SHAYNE blinked at her wearily.

"Thash a hot one. Sure, leave a call for 'em. Tell 'em the guy that picked him up outta the gutter wansh full payment on hish contract."

The juke box started up as someone put a nickel in it. Now They Are Left Behind, was the record. Foggily, the now too familiar strains came to Shayne like an eerie answer to his drunken request. He wheeled on his bar stool.

"Turn that damned thing off!" he screamed.

Someone laughed. Shayne grabbed the bottle at his elbow, rose from the stool and staggered over to the machine. With one vicious gesture he hurled the bottle through the glass panel of the juke box, smashing the contents inside. The record, of course, ceased. The silence was chilling.

"That'll cost you plenty," the bartender's voice came to Shayne. "Or I'll call the cops."

Shayne threw a fifty dollar bill across the bar. The old crone was at his side, plucking at his sleeve.

"You would like to see your friend again?" she whined.

Shayne broke into a fit of laughter.

"Shure, shure thing. Lead me to him!"

The old crone took his arm, and the cold night air hit Shayne's cheeks as they went out the door. The rest was a blur until he was climbing worn and creaking stairs in a darkened, musty hallway. Then they were in a small, incense-stinking, poorly-lighted room.

He could see the crone removing her coat, going to a table, pulling up chairs.

"Sit here," said the crone, indicating one of the chairs before the table.

Giggling drunkenly, Shayne staggered over to the table and sat down. The crone sat opposite, looking at him.

"What is it worth to see your friend?" she whined.

Shayne pulled out his wallet and threw his remaining bills on the table. The crone picked them up eagerly, eyes lighting. She stuffed them between her dirty blouse and wrinkled throat.

"Before we start," she said. "What is his name?"

"Johann Gelder," Shayne muttered sleepily. He weaved slightly on his chair. The stifling air of the place was making him foggier.

"Now we must have silence," the old crone whispered.

"No glassh ball?" Shayne muttered.

"Concentrate on silence and your friend," the crone whispered.

The silence held for perhaps two minutes. Then the crone's voice, as if from a great distance, whined, "Johann, Johann Gelder. From your tomb, Johann—arise!"

Shayne, drunk as he was, felt a chill caress his spine.

"Johann, Johann Gelder," the crone's voice came faintly, eerily. "Rise from the nameless mists and come to us."

The silence stretched for an eternity, now, and the very unnamed terror Shayne felt was penetrating his drunken fog. There was the faintest murmur of a whine in the darkened room, and a voice floated weirdly through the blackness.

"Shayne. Mark Shayne," whispered the voice. "I hear the calls."

MARK SHAYNE was suddenly ghastly white. He tried to stand,

but his knees would not support his weight. He sank back.

"I am Garth, Shayne," the voice came to him. "I am Van Evans Garth."

"Thash's not Gelder!" Shayne choked. "Send him away!"

The voice grew fainter, and the crone's thin arm stretched across the table and her hand closed over Shayne's tightly.

"Silence," she hissed.

There was still a fainter murmuring whine in the blackness of the room. This was growing louder.

"Shayne?" a faint whisper sounded. "Shayne? This is Johann Gelder, come to you. What is it you want of me?"

There was no mistaking the eerie half-whisper that floated through the darkened, stinking little room. It was the voice of Johann Gelder.

"Songs," Shayne choked. White beads of sweat stood out on his brow. His throat seemed horribly constricted. It was all he could do to speak. "I want songs, Gelder."

The crone withdrew her withered paw from Shayne's wrist. The murmuring whine grew louder. Johann Gelder's voice came more strongly.

"Take... this token... from one in the Shades who knew you."

Something was pressed into Shayne's moist palm. He looked across the table, but the crone had her arms folded and her eyes closed.

"Take this token... and hear the songs... Shayne... I leave." The voice of Johann Gelder evaporated into silence. Shayne felt like screaming after him, but he could only close his fist tightly against the object in it. More seconds of silence. Then the crone's voice came sharply.

"That is all. It is finished. They have left," she said shrilly.

Shayne rose, dropping the object into his pocket. He looked wonderingly around the room, almost uncomprehendingly. He swept his hand across his damp forehead. Then he shuddered and cursed. He staggered toward the door lurchingly through an alcoholic haze, never looking back at the crone. Somehow he got down that musty hallway. A cab driver brought him back to his terraced apartment hours later—sickeningly drunk. The elevator boy carried him into his place and put him to bed.

WHEN Shayne awoke, he could hear someone playing the piano

in the drawing room outside his door. Vaguely, he remembered the

events of the previous evening. Shakily he got out of bed,

slipped into a robe, and staggered into the drawing room to see

who the person was he had brought home with him.

The piano—a luxurious concert grand—faced his bedroom, and Shayne had to move around to the side of it to see who was playing so concertedly at this time of morning.

The keys were moving. The music filled the room. But no one sat at that piano.

It took Shayne fully a minute for him to comprehend that much. And in that minute the keys continued to move fluently, and the music continued to fill the room.

Then Shayne gasped, backing away, face whiter than before.

"What is this?" Shayne groaned.

The music continued. The keys rippled onward.

Shayne suddenly stepped to the piano, viciously jerking down the top that covered the keys. The music continued uninterruptedly. And then it came to Shayne, through the sickness and terror that he felt, that this was a composition unfamiliar to him. A song he'd never heard before. And it was played again and again, in a style that was positively that of Johann Gelder!

And then the gaps in Shayne's memory of the previous evening filled in completely. His features went from white to gray.

"Gelder!" Shayne croaked; "My God! You're ghosting again!"

The piano reached the end of the number, hesitated, and started it up again, repeating the same unfamiliar song.

And Shayne recalled Gelder's voice floating eerily through the gloom of that unholy room. Hear the songs, Gelder's voice had said. Hear this song, it meant!

Shayne's jaw was tight, his lips compressed, as he fought back the significance of this fantastic music pouring from his piano. He was sure now that Gelder was giving him another song. Why, or how, was a matter Shayne pushed from his mind.

Almost insanely he began to laugh. Then he seized up paper and pencil, strode to the piano bench, threw up the lid, and began to write swiftly on the sheets he placed before him.

Two hours later Shayne was still at it. A small stack of filled music paper lay at his elbow, and the piano tinkled on. He had three songs, and was transcribing the fourth. The lyrics came automatically, as if another hand were guiding his own.

AN hour after that, utterly exhausted, Shayne had

finished. The piano, the moment he'd transcribed the last note

and lyrics, had ceased also. Shayne took three stiff highballs to

straighten himself up, and then he dressed hurriedly. He wasted

no time shaving or bathing.

In the taxi on his way to mid-Manhattan, Shayne smoked cigarettes intermittently, nervously, fighting back the almost hideous hammering of his heart. The cab took him to the offices of the Midtown Music Company. A secretary, looking curiously at his disheveled appearance, at the portfolio he carried under his arm, and seeming startled when he gave his name, ushered him promptly into the offices of the publisher, one Mike Morrison.

Morrison was more than surprised to see Mark Shayne. It had been months since Shayne had appeared in the publishing centers. Months since his contract with John Colder had been broken.

Shayne came immediately to the point.

"It's broken, Mike. That dry spell is through. I got four of the damndest tunes you ever heard, right here with me. They're yours to publish, Mike."

"What about John Colder?" Morrison asked suspiciously. "It would be a good chance to clean up that contract mess with him if you gave him the tunes."

Shayne snarled something unclean.

"That louse couldn't have the dirt from my shoes. They're yours, Mike."

Morrison, eyes speculative, punched a button. A pianist came in a moment later. Morrison gave him the music manuscripts Shayne had put before him. The pianist went over to the scarred piano in the corner and ran through the first bars of the first song. Morrison lighted a cigarette and sat back.

Shayne paced back and forth nervously as the music began. When the first number had been played, the pianist looked up puzzledly at Morrison.

"Hell, Boss," he began.

Morrison waved his hand.

There was a peculiar glint in his eye. Ten minutes later, when the pianist had finished the last note on the last number, Morrison turned to Shayne.

"This," he pronounced grimly, "is just what the music business has been waiting for."

"You mean?" Shayne choked hopefully.

"I mean you're through, Shayne. Washed up. We've enough dope on you from this to blackball you in the music industry for the rest of your life. Get out of here, you damned skunk, and don't poke your nose around again. Those tunes, all four of them, are due to be published by John Colder's outfit in two weeks. They were written by Colentze and Bardine. I don't know how in the hell you stole them, or who sold them to you, but you've bitten off sucker bait. Beat it!"

Dazedly, strickenly, Mark Shayne left the office. His eyes were slightly glazed, his mouth half agape, as he rode back to his terraced apartment. Alone, he entered his suite. The piano in the drawing room was playing. The tune was Now They Are Left Behind.

Shayne didn't approach the piano as it played. He knew no one would be sitting before it.

He went to his bedroom, found the discarded coat he had worn the night before. Fishing into the pocket he pulled forth a hard, square object. It was the gold-mounted five-dollar bill that he had placed in the cold hands of Van Evans Garth before his burial.

Like a man hypnotized, Shayne walked through his drawing room and opened the French doors that led out to his terrace. Down below him, some thirty floors, New York shimmered in the afternoon dusk.

Through the French doors that led to the drawing room, Shayne could hear the piano still playing Now They Are Left Behind. He climbed atop the parapet railing and stood teetering on the wind-swept perch. Then he swayed forward, and down.

In the apartment, the piano stopped playing...

No one ever mentioned the afternoon Shayne spent with Mike Morrison. Not even John Colder, who learned of it shortly after Shayne had left. And the gold-mounted five-dollar bill must have been lost in Shayne's downward plunge. For after his death it never became a part of the Mark Shayne Legend.

THE END

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.