RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

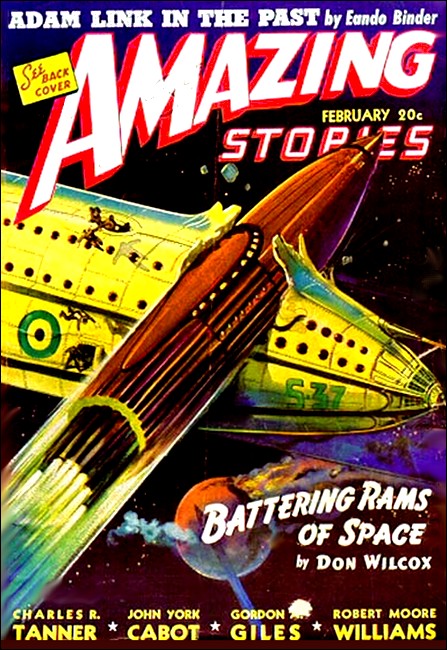

Amazing Stories, February 1941, with "The Last Analysis"

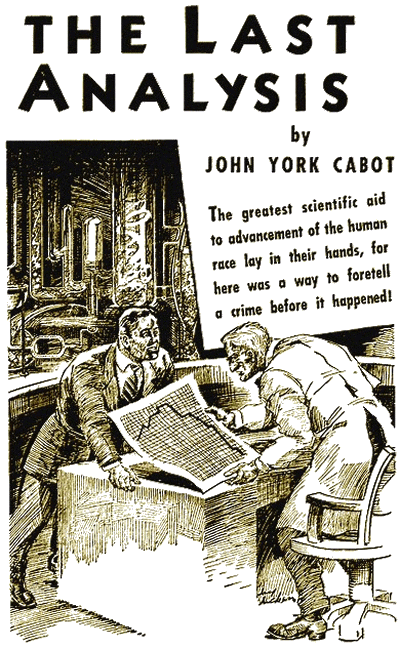

"I hope you got this sample from the morgue!" said Forbes.

BOTH men were exhausted. It was evident from the sharply etched lines of fatigue that marked their features, the gray-black circles that ringed their eyes. But beneath the exhaustion of them both, there burned a feverish excitement.

The vast white laboratory in which they worked was littered with the evidences of their intensified efforts. Tubes bubbled with liquid compounds and tables were covered with a maze of papers and graphs. Compasses and pencils lay strewn about.

Forbes—he was by far the older of the two—leaned over one of these tables, a tall, gaunt, white-haired skeleton of a man. In his stained chemical smock he looked like some weird necromancer out of some long-forgotten legend. The pencil in his thin, strong hand moved rapidly over the papers before him. His every motion, every gesture, was cool, swift, efficient. He seemed to radiate assurance.

Before the line of bubbling tubes, checking the variance of the multicolored liquids, Barton—the younger of the pair—paced excitedly back and forth. He couldn't have been more than thirty, this young assistant in research, and like Forbes, he wore a once-white chemically stained smock. His hair was lank and dark, and hung over his forehead. His features, but for the stamp of fatigue on them, were strong, even, almost handsome. But in his movements there was none of the calm assurance that marked his older superior. Barton's actions were jerky, nervous, seeming to indicate the terrific mental tension that tingled through the vast laboratory.

Impatiently, Barton moved up and down the line of tubes, brushing his lank, black hair off his strong forehead now and then, and making swift jottings on the notes he held in his hands. Then he turned from the tubes and moved over to the table where Forbes stood. Silently, the young man placed his tabulations on the table, and the gaunt, white-haired old man drew them closer with his thin hand. After studying them swiftly for a moment, Forbes turned to his assistant.

"Good enough, Barton," declared the old man calmly. "It seems to check. We can take time enough for a cigarette if you like." The tall, gaunt scientist fished into the pocket of his stained smock as he spoke, and brought forth a crumpled packet of cigarettes, offering one to the younger man with a friendly gesture.

Barton took a cigarette with hands that trembled slightly, and the old man, noticing this, smiled. "There now, boy," he said softly, "calm down a bit. We've still more work to do before this thing is completed. Try to relax as best you can."

The young assistant ran a hand across his face, shaking his head slightly. "I'm sorry," he said. "But you can understand how I feel about this, sir." He was trying to smile now, and was succeeding to a small degree.

Forbes nodded, exhaling blue smoke between the words he spoke. "I know," he admitted. "I was the same when I was your age, Barton. Even the smallest experiments used to work me into a lather of excitement. I don't know if I would have reacted as well as you're doing now, had I ever been engaged in anything as important as this."

Barton smiled self-consciously at the compliment.

"For this is an experiment of great importance," Forbes went on. "I'll be the first to admit as much. I was very careful in choosing you as my assistant, Barton. Very careful, as you'll remember. I was in need of someone with youth, someone with energy. You had both, in addition to knowledge far beyond your years and experience." He reached forth to place a thin hand on his young assistant's shoulder. "I'm well pleased with you, boy. Well pleased. I'd never have shared credit for my findings with anyone other than you."

Barton lowered his eyes in embarrassment. "Thanks, sir," he mumbled.

"It will be quite a feather in your scientific bonnet," the old man went on. "Quite a feather. I doubt if you'll ever accomplish anything of greater magnitude."

"The Forbes-Barton Equation," the young assistant said, face shining. "Damn, sir. I don't see how there could ever be a discovery of greater magnitude!"

Forbes smiled tolerantly. "We're but laying the foundation, lad, the groundwork, for scientific strides that will far outdistance our own. What we are doing will totally eliminate sociological ills in the world. Totally eliminate them."

Barton shook his head. "A world without hate, without murder, without crime, without war. It's almost impossible to grasp the scope of it all."

"You've forgotten, Barton, that what we accomplish here tonight is just the beginning," the old man cut in. "To prove our equation to our own satisfaction is one thing. To prove it to the world is another. Our announcement is going to be greeted with skepticism, intolerance, lack of understanding. The sneers of the world will not be easy to take."

The young assistant's eyes glowed feverishly. "Damn them, sir! We'll put it across whether they like it or not. Surely the men of science, the men of medicine, will see the value of our equation."

Forbes nodded. "They will haggle over it, probe it for inaccuracies, quibble over its theory, while the world looks on at it all as sort of a novelty, yes." He smiled. "But it will take them time to see what we're driving toward."

"We're driving toward the elimination of crime. The elimination of crime by scientific equations. Certainly they—"

Forbes shook his white head, his thin features fixed in calm amusement. "They'll listen to us when we prove that the physical equations, the chemical components, of each man are as separate as fingerprints. They'll listen to us when we say that each man's chemical components can be classified—individually—to label that man specifically by an equation peculiar to himself, an equation possessed by no other man. They'll listen when we tell them that we can identify any man by the resultant chemical equation of the matter that goes to make his body—yes."

"But they'll listen, too, when we tell them that—" Barton began.

"Tell them that we can classify them as criminal or non-criminal types, just by their chemical equation?" Forbes cut in. He shook his head. "No. I don't think they will listen. You can't tell the world that some of them, whether they know it or not, are positive criminal types. You can't take the chemical equation of a banker, for example, and tell him that his equation makes it absolutely unavoidable that he will, at some time or another, commit a ghastly crime."

"But they will have to realize that!" Barton broke in, face flushed feverishly. "They will have to realize that, before we can sociologically adjust the world!"

Forbes shook his head. "It will take time, lad, much time. Perhaps neither of us will live to see the day when our equation will be accepted. We can merely tell the world what we have found, give our findings to science, as a record, something to work on. Something to believe when the time comes."

"But why won't they be able to see, just as we have seen, that every man, from the time of infancy, has a set chemical equation that will determine his status, sociologically, for the rest of his life?" Barton's voice was edgy. Obviously the strain of the experiment was causing his exasperation.

"That," Forbes replied kindly, "is another thing that will take time. Can you picture trying to tell a mother that her infant has definite criminal equations, that her infant is destined to murder at some time in the future? And that, for the sake of the world, her infant must immediately be eliminated from existence?" He shook his head. "No. You can't. But that is the inevitable result toward which our findings point, the day when the world will be sociologically harnessed by just such methods." He put his hand on Barton's shoulder again, shaking him slightly. "No, boy. Our task is but to prove this equation. In that alone, we should be satisfied."

"I had almost forgotten that," Barton nodded. "I'm sorry. I guess the strain must have had something to do with this outburst." He shook his head, as if to clear it. Then, dragging deep from his cigarette, he dropped it to the laboratory floor, crushing it out.

"Certainly," Forbes agreed, digging his thin hand into the young man's shoulder. "We can be satisfied in merely our part, eh, Barton?"

Barton nodded, then smiled. "Right."

The old scientist crushed out his cigarette on the laboratory desk, took a deep breath, stretched.

"Well," he said. "We might as well get back to work, eh, lad? Our final checkings should see this thing through. Have you got the lists, the equation findings?"

BARTON stepped over to a tube, took it off a bunsen

burner, and brought it back to the table. "This is the first," he

announced. "You have the component readings on those slips I gave

to you."

Forbes set the tube on a rack before him, reaching for a large cardboard chart as he did so. Then, while his young assistant looked on breathlessly, the old man began a series of rapid calculations. There was a tiny vial of blue liquid at his side, and as he worked, he added drops of this to the tube which he'd placed on the rack. At length he looked up at the tube.

"Green-amber," he muttered. "Right?"

"Correct," Barton answered. "Exact shading."

The old man ran his thumb down the chart, stopped, cleared his throat. "Sociologically perfect, usual human inaccuracies, but quite on the non-criminal scale. A slight tendency toward deceit." He looked up at Barton. "Where did you get this component?"

The young man smiled. "I knew the District Prosecutor's physician. He made the chemical analysis for me."

"Then this belonged to the District Prosecutor?" asked the old man, grinning. "Good work, Barton. We seem to have tagged him correctly. Give me another."

Barton moved over to the line of tubes, taking another one from its bunsen burner. Forbes placed it on the rack beside the first, and while his assistant watched, he repeated his previous operations. Then he was looking at the chart again. After a moment he looked up.

"Hmmmmm," Forbes mused. "Criminal type, positively. Possesses an almost bestial lust for blood, touched by insanity." He frowned. "Where did you get this?"

Barton grinned. "Hit it on the head again, sir. I made the component test in the morgue. That was the tube of a certain Geno Sparelli, a local gangster who was shot down in a battle with the police just yesterday. I also knew a young interne at the morgue. He let me make the component from the body."

The old man smiled. "This seems to be quite in order, then. Get me the third."

Again Barton brought back a tube, and again the old man went through the same processes. At last he looked up. "This is easy. Obviously, this component belongs to the non-criminal equation. Mild to the point of temerity, almost introverted in desire to avoid violence of any type. Would never have even the slightest criminal leanings. To whom does this equation belong?"

"A maiden school teacher. My aunt, to be exact," Barton chuckled.

Forbes smiled. "These are all too easy. Bring me another."

IN a moment Barton had returned with the fourth tube. He

gave it to Forbes, grinning expectantly while the old man placed

it on the rack and began his computations. Forbes seemed to be

taking a little longer over this. He looked up once, remarking,

"I hope you got this from the morgue, Barton."

Then at last the old man pushed aside the chart. "This," he said, "is different than the others. Criminal type, yes, but of a subtle nature. The equation shows greed, a touch of insanity, which makes violence an inevitable result. Violence and probably murder."

Barton's grin had slid from his face, and a growing horror was visible in his eyes.

"What's wrong, lad?" Forbes said quickly. "To whom does this equation belong?"

Barton's only answer was a shudder.

"Come, lad, speak up!"

"Try it again, sir!" Barton said at last, huskily. "For God's sake try it again!" He seemed to choke. "You must have made an error!"

Frowning, Forbes bent over the chart again, and laboriously, slowly, began to recheck his findings. At the far end of the vast laboratory a clock seemed to tick with the loudness of hammer falls. Beads of sweat stood out on the young assistant's brow, and the horror was still in his eyes.

After minutes that seemed as hours, Forbes looked up. He gazed intently at his young assistant, then cleared his throat. "I made no mistake," he said. "The findings are exactly as I first stated they were!" Then, in a softer tone, "Come lad, tell me whose equation this is. Someone you know?"

"Can't it be wrong, sir?" Barton's voice was hoarse.

Forbes shook his head. "No. There is no margin for error. This component reading, this equation, is that of a killer, a person driven to violence through greed and an unstable mind!" He paused, then more sharply: "To whom does it belong?"

BARTON'S face had gone chalky white. "I don't want to

tell you, sir. It's wrong. It has to be wrong. That person has

never been guilty of the slightest criminal tendencies.

I—that person, would never think of violence of any sort."

Forbes was looking at his young assistant with dawning apprehension. "The person to whom this equation belongs," the old man said, "might not have committed any crime as yet, lad. But the evidence is here. He will do so, just as definitely as two and two will add to four!" He cleared his throat. "The findings are certain."

"But, sir," Barton began. "Greed and violence, I—"

Suddenly the old man paled. "Good Lord, Barton! You don't mean that you—?" he broke off meaningly.

"It must be wrong!" Barton burst forth.

"Greed, ending in violence!" The old man's voice was aghast, "it can't be, but," he paused, "the only greed you would have would center around the most important thing in your life—this experiment!"

Barton was trying to find words to protest, but the old man hurried on. "The only greed you could have would be for credit on this discovery, and the only violence which could attain it, satisfy it, would end in my death!" He stood up now, trembling, composure gone.

"But, sir," Barton's voice was near hysteria, "I can't—"

"The tube you gave me, the component, was your own!" the old man was saying, as if to himself. He was looking aghast at his young assistant, not hearing the words that were clogging in Barton's throat.

"I—I..." Barton gurgled, his face red in torment.

"You would kill me," Forbes breathed in horror. "You would kill me to gain the honor of our findings!"

"Professor Forbes—" Barton began.

"But you won't!" the old scientist said suddenly. And his hand, which had been exploring in the drawer behind his back, came forth with an automatic pistol. "You won't," he said hoarsely, while the gun spat and kicked in his hand.

Barton was sliding slowly to the floor, his stained smock splashed red above the heart, his glazing eyes fixed on Forbes as he dropped to the laboratory floor. -

"I—I tried to tell—you ... I tried...." He coughed horribly, blood gushing from his mouth. His head sank to his chest, then with an effort, he raised it again.

"I—thought it—couldn't... You didn't make a mistake... That tube was—"

Forbes stared down at the fallen man, his face suddenly going ashy gray.

Barton's dying eyes stared straight up into Forbes'.

"Professor... Forbes," he uttered through blood-flecked lips. "That tube... was your... own!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.