RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

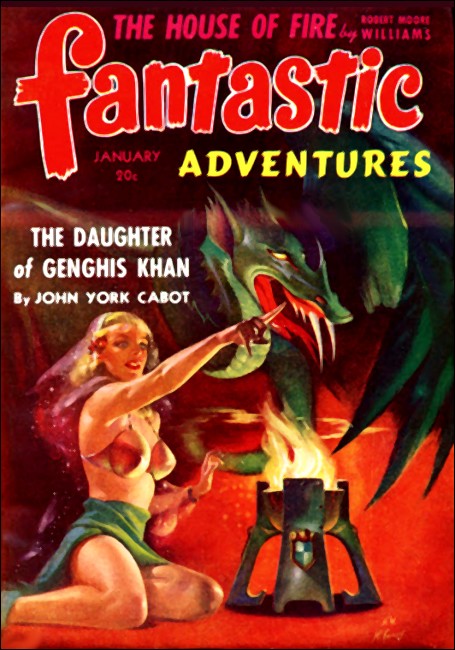

Fantastic Adventures, January 1942, with "The Daughter of Genghis Khan"

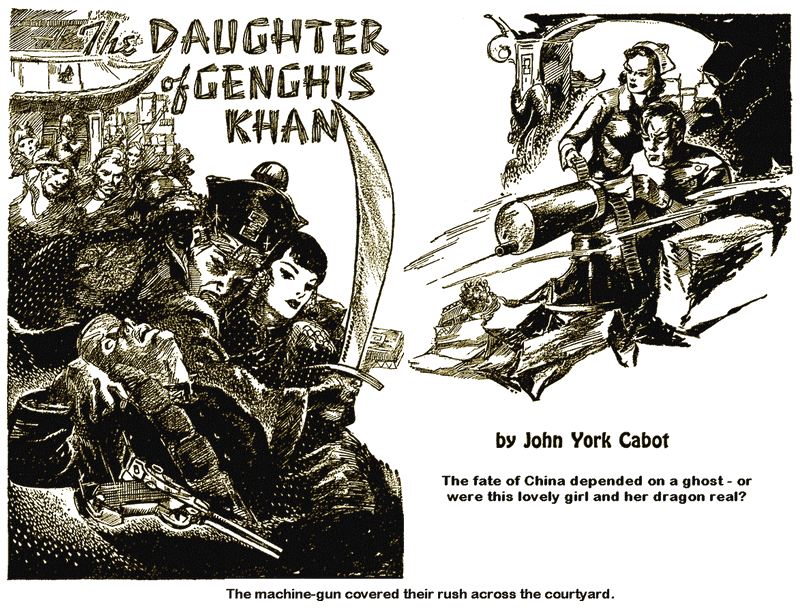

The fate of China depended on a ghost—or was this lovely girl and her dragon real?

"DOCTOR," a ragged, ill-uniformed messenger from General Wong's Chinese Nationals appeared at my shoulder and gave a half salute.

"Doctor," he repeated, "the General wishes to see the American Doctor outside."

A shell burst somewhere within a four hundred yard radius of our hospital. There was a prolonged staccato of rifle-fire immediately after it. I had to raise my voice for him to hear my answer.

"Tell him I am at work," I shouted. "Tell him to come in here if he wishes to see me!"

The ragged soldier looked dubious. He had the flat face and wide nose of a peasant from the outer provinces. He half saluted once more and left.

I went back to cauterizing the slashed leg of an old crone on my right. I had to use raw alcohol to sterilize the wound. But her faded old eyes were expressionless as I swabbed the fluid into the deep slash. There would be little I could do to prevent gangrene from setting in.

The little village of Tinchan had been under Jap bombardment for twenty-four hours now, but the ramshackle building we were using as a hospital was still somehow unscathed.

I was working in the main dormitory. The main dormitory, that is, if you can call a louse-ridden barn covered with straw matting in lieu of beds a dormitory. There must have been several hundred victims, all of them non-combatant peasants, lying along the walls of this main room in various states of mutilation and near death.

There was no whimpering, no moaning, even though our scant supply of pain-dulling sedatives had given out ten hours ago. In China the wounded and dying carry their stoicism even into death.

It was already dark, and so I had to administer what little medical attention was in my power by the flickering unsteadiness of smoky kerosene lamps hanging from the rafters.

I had a little cheap rum left, and I gave it to those who needed it most—those on whom I would have operated speedily if we'd still had our operation equipment.

Linda Barret was over on the other side of the room, changing the bandages on the bloody stump that had once been a child's arm. Her face was white and drawn from fatigue, and one cheek was smudged from the soot of a lamp she'd filled a moment before. Her red hair was disordered and her tunic torn badly at the elbow.

She looked nothing like the Boston Back Bay debutante who'd joined my Red Cross unit in Shanghai four months before.

I bandaged the crone's leg then, and when I stood up I saw General Wong entering the place. He wore a faded blue uniform that fitted his squat, fat frame too snugly. There was a black Sam Browne belt to embellish his attire. A huge automatic hung holstered from his side. He glanced unemotionally at the wounded, saw me, and started over toward me.

"Doctor," he said in his deep voice when he was four feet from me, "Doctor, I must advise you to leave Tinchan. The enemy will arrive inside of a half hour."

General Wong had been a despot war lord, a typical hill bandit, until the invasion. Then he'd thrown his military force in on the side of the Nationals. His face was deeply pockmarked, round and moonlike, and his eyes had the glaze of one who enjoys opium. Like Chiang Kai Shek, he'd risen from the ranks of the peasantry. But unlike the leader of the Nationals, Wong had risen by force rather than brains.

I shook my head.

"Sorry, General Wong. I'm staying here." I waved my hand to indicate the wounded lying all around us.

General Wong's moon face registered annoyance.

"The enemy forces will have the village in another half hour," he insisted. "You leave. Come with me."

I wasn't certain, but I thought I saw his eyes flick toward Linda Barret.

"Must you lose Tinchan?" I asked. "Your forces far outnumber those of the enemy troops besieging the village."

"Doctor Saunders," Wong snapped angrily, "you will please leave military decisions in my hands. Your field is medicine."

I nodded.

"That's why I'm staying," I said. "Here."

General Wong sucked in his breath.

"As you want it," he said. "My troops have already started withdrawing. You will have our protection if you join us. If you remain here I will not be responsible."

"I will remain here, General," I repeated.

General Wong started to wheel, then turned back.

"The American girl. Will you permit her to risk her life?" He pointed at Linda.

I raised my voice.

"Linda!" I called.

Linda Barrett looked up quizzically, then came over to us.

"The General," I said, "is evacuating Tinchan. He wishes us to leave with him. I told him I was staying. He's offered you the protection of his armies if you care to go along."

Linda has blue eyes. They examined the squat, fat figure of General Wong indignantly.

"Of course not," she snapped. "I'll stay right here with Doctor Saunders. Thank you just the same, General."

Wong's lips went flat against his teeth.

"Very well!"

He saluted and left.

"So General Wong is giving up Tinchan to the enemy?" Linda said. There was contempt in her voice.

"There might be some risk in your staying here, Linda," I said. "It would be safer with Wong."

"Wong can run in the face of the Nipponese," Linda said, "but I won't, Cliff. You should know that by now." Her tone was reproachful.

I nodded.

"Yes, I know, Linda. I've a lot to be grateful for in the help you've been. I don't know what I'd have—"

"Enough of that," Linda cut in swiftly. She was suddenly all woman of steel again. Then she asked me some question about our rapidly diminishing store of bandages.

"We've enough for the moment," I answered. "But when we're finally out of it, I don't know what we'll do."

"Perhaps the Japs will—" Linda began.

I shook my head.

"You've been in China only six months, Linda," I reminded her. "I've been here better than four years now. We can expect no help from the invaders. In fact we'll be lucky to be permitted to continue, if their effort to close up the Burma Road is successful."

Linda sighed.

"I guess you're right, Cliff."

I was speaking half to myself now. "And if Wong keeps pulling his forces away in retreat, they'll be able to cut the artery on the Burma Road within a month."

Linda's jaw set.

"Why did he retreat from Tinchan, Cliff? Why did he retreat when his forces outnumber the advance Japanese units by at least two to one?"

I shrugged.

"I asked him that," I answered. "If he had a reason he wasn't giving it out."

Linda shook her head dubiously.

"I don't like General Wong. And it isn't because of his bad breath, which seems to be the result of too much rice wine and opium."

"Neither do I," I agreed. "But the Nationals have to depend on him to carry the fight in this sector for another month."

Another shell burst close to the hospital—a little too close for comfort this time. Linda turned and went back to her patients. I got busy also. The shelling grew heavier during the next fifteen minutes, and now and then I paused long enough to take an anxious glance up at the swaying kerosene lamps hanging from the rafters.

IT must have been about five minutes after the shelling had

reached its most violent pitch that it suddenly stopped. I knew

what that meant. The last of General Wong's troops had left

Tinchan, and the Japs were entering the town. They'd stilled

their artillery fire. Now there was only the occasional outbreak

of rifle volleys, which came nearer and nearer to the hospital,

to indicate that the Japs were mopping up on whatever small

sniping nests Wong had left behind to cover his retreat.

I finished dressing the wounds of the last patient along the aisle on which I'd been working. I went down to Linda, then, who had also been busily rushing through the changing of the dressing on a youngster's foot.

She straightened up, speaking in Cantonese to the youth.

"It is all right now. You must try to rest. Don't move it."

"Linda," I said.

She turned around.

"That should be an amputation, Cliff. I don't suppose it can be done, however."

I shook my head.

"Not without the proper instruments. I took a look at the boy's foot an hour or so ago. Look, Linda, the Jap troops are already in the village."

"Yes," Linda said coolly. "I heard them mopping up."

"Don't you think you'd better go up into the supply room on the second floor?" I asked. "I'll handle them when they come into the hospital. If they saw a young white woman here—"

"No," Linda said, breaking in and shaking her head emphatically. "I'll be quite all right."

I pointed to the holstered snub automatic that hung from her waist.

"You've that to use if anything goes wrong," I reminded her. "There's always a bullet left, remember."

Linda touched my arm.

"I know, Cliff. A bullet for myself. But cheer up, I don't think there'll be trouble."

I forced a smile.

"Probably not. At any rate you're safe as long as I'm around. I just reminded you in case something might happen to me." Inwardly I shuddered at the recollection of the plunder and ravaging I had seen on one horrible occasion in the village of Hoyang about a year ago.

And suddenly Linda's mouth went straight and she was looking fixedly over my shoulder.

"Here they are, Cliff!" she whispered.

I wheeled, and saw three short, helmeted soldiers of Nippon, rifles held in readiness, striding into the hospital through the front entrance!

Briefly I squeezed Linda's arm.

"Stand here," I said. "I'll talk to them." Quickly I went toward them.

THEY saw me almost immediately, their eyes sweeping over me in

hostile suspicion. I realized I had an automatic pistol strapped

in a holster around my waist. I took a deep breath. These Japs,

depending upon whether or not they were of average intelligence,

might just take a pot shot at me because I was armed. But there

was the American flag and the Red Cross emblem on the outside of

the ramshackle hospital. They must have seen that.

All three had stopped dead, and stood waiting indecisively, their fingers flexing around the stocks of their rifles restlessly.

I shouted to the foremost of them.

"American Hospital. Red Cross. American Hospital. Neutral!"

The foremost soldier was shorter than the rest. He had a small black scrub of a moustache that was barely discernible under the grime that covered his yellow features. I saw him glancing over my shoulder at Linda. My spine stiffened in sudden chill.

"Bring your commander," I shouted. My Nipponese was very faulty at best, but I tried a little of it, repeating my previous words and the final request.

The black-moustached Jap frowned, nodded. He turned to his two companions and said something in a Jap dialect unfamiliar to me. Then he turned back to me.

"Commander," he said with a little difficulty. He turned away then and started for the entrance to the hospital, leaving me facing the two remaining soldiers. I breathed a mental prayer that he was off to find his commanding officer.

I could see the two companions of the moustached Jap soldier looking past me at Linda, and from the manner in which their eyes shifted I knew that she was moving around, tending to the wounded. Finally, after what seemed an eternity of waiting, the little Jap who'd gone to get his superior officer returned. Behind him, in an immaculate uniform, was a brusque, bespectacled, slightly taller Jap. His insignia showed him to be a captain in the emperor's army.

The bespectacled Jap captain wore highly-polished field boots which somehow hadn't been caked by mud. He shoved past his underling and marched up to me.

"I am Captain Yokura, Japanese Imperial Army," he announced in perfectly flawless English.

"I am Doctor Saunders, American Red Cross unit here in Tinchan," I replied. I extended my hand.

The little officer shook my hand briefly, lightly, seeming to study me from behind the thick lenses of his spectacles. Then he looked around the hospital room.

"Tragically unnecessary," he said. "Slaughter always is."

I nodded.

"Yes, I know."

Captain Yokura shook his head.

"They will never learn, these Chinese, that we are here for their own good."

That was ironic. It was my turn to look around the room.

"Are you?" I asked.

"You Americans can't seem to understand either," Captain Yokura said, catching the sarcasm in my tone. "And the sooner you do so, the better it will be for all of Asia." A sharpness had entered his voice.

"Perhaps our ideologies differ," I said.

"Not to a great extent," Yokura said. "I was at Princeton, in the States, for four years. I had plenty of opportunity to study your democratic philosophies."

THIS conversational sparring wasn't helping things any. I got

to the point.

"Will our Red Cross unit be allowed to continue in this sector?" I demanded.

Captain Yokura shook his head.

"I am very sorry, but all we can offer you, Doctor Saunders, is safe conduct to another sector. You cannot remain here."

"But—" I began indignantly.

"You cannot remain here," Captain Yokura repeated with finality. "We will escort you and your assistant, the young lady back there, to another and less, ah, dangerous sector. You should be grateful for that."

"And if we refuse to leave?" I demanded.

"It would be troublesome," Captain Yokura promised ominously, "to all of us, but especially to you and the young lady. You would be wise to question my order no further, Doctor."

"And what about these poor devils?" I gestured to indicate the wounded who filled the room.

Yokura swept a glance over the Chinese peasants. A glance that held no sentiment, no pity.

"Our medical staff will take care of them," he declared.

"The same way that your medical staff took care of wounded peasants in the Hunang sector?" I asked. That incident, which occurred less than five months before, had been brutal butchery.

Captain Yokura shrugged.

"That is up to us."

I felt a surge of futile rage sweeping over me.

"Then I am not leaving this hospital, Captain," I said hotly.

The captain merely turned and barked something to his three soldiers. Their gun points were instantly trained on my forehead.

"You will call the young lady," Yokura said, "and then the two of you will leave. I'll personally escort you to the adjoining sector."

I must have been trembling slightly from the rage I felt. I looked at the muzzles of the guns that pointed at me. Captain Yokura must have read my mind.

"Please don't do anything silly," he said. "Remember the young lady. Call her, please, and we'll get started."

Reminding me of Linda, as he'd done, served as a dash of cold water on my rage. I gave in. There was nothing else I could do. Captain Yokura was smiling unpleasantly at his minor victory. I turned and called to Linda....

THE night along the rutted roadside was pitch black. No stars were out, and the moon was hidden deep behind a thick gray bank of ominous storm clouds.

Far behind us was the little village of Tinchan. By looking back over my shoulder, I could see the tiny fires that had already been started there by the invaders. I tried not to think of the pillage and carnage that was probably under way by now. I also tried very hard not to think of the "attention" the poor peasant casualties who'd been my patients were receiving from the Jap "medical staff" of Captain Yokura.

Linda was beside me, and the two of us sat in the rear of an open touring car of European military make. Beside us was Captain Yokura, and in the small seats facing us, two armed soldiers whose purpose was evidently to see that neither Linda nor I attempted any stupid effort to return to Tinchan. Another two soldiers sat in front, one of them driving.

I had explained the situation to Linda, of course, and she'd readily understood that there'd been nothing else to do. Her rage at our treatment, however, had been as great as mine. She'd made no secret of the contempt she'd had for Captain Yokura and his forces.

But that had all seemed to heighten Yokura's efforts to keep the proceedings on a tone of exquisitely hypocritical cordiality. He kept up a constant stream of chatter to us from the moment we'd left the burning village of Tinchan in his motor escort.

Now, two hours away from the village, his chatter hadn't lessened. He'd told us about his Princeton experiences, told of his opinions on various matters pertaining to American government, and laid a great deal of emphasis on clarifying what he seemed to consider our "American lack of understanding" concerning Japan's "Great Mission in China."

I hadn't bothered to say much, and neither had Linda. However, that hadn't dampened Captain Yokura's conversational leanings in the slightest. He was in the middle of his explanation about the military strategy he employed in the taking of Tinchan when, suddenly irritated beyond bounds, I broke in.

"Your capture of Tinchan, Captain," I said, "was a farce. Your armies were greatly outnumbered by General Wong's forces. He could have held the city indefinitely, except for what seemed to be a peculiar willingness to turn over the place to you."

Captain Yokura's mouth had been half open to speak. He paused, giving me a suspicious glance.

"Apparently, Doctor Saunders, you are not much of a military observer. General Wong's troops lost the town because of my superior strength in artillery."

"General Wong had more artillery than you did. However, it was never in proper range to be effective. In addition to that, the general killed a junior officer for suggesting that he change the range. The general called the suggestion 'insubordination under fire,'" I concluded.

MUCH of Captain Yokura's hypocritical affability vanished. The

corners of his mouth went tight.

"For a neutral, Doctor Saunders, you seem to possess a great deal of military information."

"I'm not completely a damned fool," I answered.

"I don't think your attitude is particularly healthful, Doctor."

"Neither am I a coward," I snapped.

Captain Yokura sucked in his breath regretfully.

"I shall be forced to turn you over to our Military Intelligence when we reach the adjoining sector," he said. "You are too full of, ah, erroneous information."

And suddenly Linda broke in.

"Please include me in that party, Captain Yokura," she blazed. "I'm awfully anxious to see how far you can fly in the face of our consular officials. I don't think you'll be pleased by the counter-action they take. Your government is trying rather hard to avoid what might be classed as an 'incident' at this particular moment."

Captain Yokura sucked in his breath again, sharply. It was obvious that his dignity had been ruffled by the intrusion of a woman. However, he said nothing in reply. He leaned forward and barked something in Japanese to the soldier driving in the front seat. Then he sat back, looking out at the countryside, keeping his gaze fixedly from either Linda or me.

There was a pass ahead. It was a twisting turn that ran along between the side of a small hill and a huge boulder that was part of the first foothill of a large mountain. The stars were still hidden, and the night was still black. We were driving rather slowly, without the use of headlights. Yokura seemed a trifle anxious and looked back over his shoulder several times to make certain that the small column of some fifty horsemen he'd brought along as a rear guard were within earshot. I could hear the clumping of hooves but faintly, and judged that the horsemen must have fallen about a half-mile behind us.

I looked at Captain Yokura and smiled contemptuously.

Our eyes met and locked for a moment. And if the little Jap officer had had any intention of waiting for our rear guard to come up before venturing through the pass ahead, his awareness of my scorn suddenly made him change his mind. His jaw went tight and he didn't look back again.

Then we were bumping along deeper ruts in the roadway which marked the start of the twisting entrance to the pass. It grew darker as the sides of the pass threw heavy shadows over our automobile. The only sound now was that of the motor.

We turned abruptly, following the twisting course of the road. Then we turned again. I looked down at Captain Yokura. His face was strained.

And then it happened.

TWO sharp rifle shots came. Our car suddenly careened into the

granite side of the pass, driverless as the soldier at the wheel

slumped forward dead. Captain Yokura was snarling, pulling at the

automatic pistol in his belt and trying to reach for the wheel in

the same motion. The soldiers who sat facing us were on their

feet, and suddenly were thrown into our laps by the collision of

the car into the wall of the pass.

I was pushing bodies away from me and trying to get to Linda's side. The car had stopped, motor killed. Yokura had been thrown heavily to one side as one of the soldiers tumbled off balance against his legs.

Then they were all around the car. More than a dozen of them, all carrying rifles.

In the darkness it was hard to make out their faces or uniforms. But they weren't Japs. They wore the tall fur caps of Mongol bandit warriors. I could see Captain Yokura climbing to his feet. He was raising his automatic to fire.

One of the Mongol warriors clubbed him over the head with the stock of his rifle. Yokura sank grotesquely to his knees. I heard his pistol drop to the floor.

The two Jap soldiers tried to leap from the car and take to flight. They were also clubbed down. The bandits were opening the doors of the cars, dragging Captain Yokura's limp form out. Two of them climbed in from the other side. Their rifles were pointed at Linda and me, ordering us out.

"Be very calm, Linda," I muttered inanely. "Be very calm until we see what this is all about." I had my arm around her.

We climbed out of the car, and suddenly arms wrapped around me from behind, and heavy cord was looped around my body. Linda had also been seized. I tried to struggle. It was useless. The cord drew in. With incredible swiftness I was bound and gagged. Then I was being carried like a child up the steep side of the path. I tried to twist and turn, tried to see where Linda was and what had happened to her.

There were horses. The rugged, squat, swift Mongol breed. I was thrown across the back of one of these. Then I saw Linda. She was also bound and gagged, also thrown across the back of a horse.

Another rifle shot, then a sudden pounding of hoofbeats and we were off, racing along a tangled path up the side of the cliff. My eyes and ears and nose were filled with dust. The Mongol bandit who rode the horse to which I was strapped, gripped the bonds along my back roughly with one hand so that his burden wouldn't fall off. I was choking as the bandage across my mouth filled with the dirt kicked up by the horses. I shut my eyes and braced myself as best I could against the tremendous jarring my body was taking.

I don't know how long we rode. I lost all track of time or direction. Occasionally the horses slowed to a walk. Again they galloped furiously. Sometimes I was aware that we climbed up along steep paths, other times I knew we raced along broad plateaus. But it was growing harder and harder to fight off the fog that seemed to be pressing in against my brain.

Working at the hospital I hadn't slept in over fifty hours. I wasn't a physically rugged person. Another man might have remained conscious through this beating. But finally blackness closed in around me and I remembered no more...

THERE was a humming sensation in my brain, and my head ached

dully. I opened my eyes, blinking in the glare of torch-lights.

Unconsciously I moved, and then I realized I was no longer gagged

and bound.

I was lying on a clean grass matting, amazingly soft in spite of the aching I felt in every muscle of my body. There was the pungent smell of food in the room, and rising on my elbow I saw that the small cell in which I was confined contained another grass matting in the far corner. Linda was lying there, asleep, breathing easily.

The odor of food came from four or five rice and chicken bowls in the center of the floor. They were still steaming and must have been recently placed there. Four torches, each in a niche in each corner of the room, provided the illumination.

I realized then that my hands and face had been bathed, and oil apparently applied to the bruises around my wrists and ankles made by the bonds. I sat up, wondering where we were and recalling that the Mongol bandit warriors had probably brought us here.

Rising to my feet, I stretched my aching muscles carefully. Then I went over to Linda. I shook her gently four or five times before she opened her eyes. It took a moment for her to recognize me.

"Cliff," Linda began, looking bewilderedly around the little room. "Cliff, where are we? What's happ—"

I cut in.

"Take it easy, Linda. We seem to be all right for the present. I'm not certain where we are."

"The Mongol bandits," Linda asked, "they brought us here?"

I nodded.

"As far as I can remember. Are you all right?"

Linda started to rise, and I helped her to her feet. She stood there, swaying a little dizzily for a moment. Her face was white and she was obviously a little shaky.

"Yes," she said. "I'm all right. I just feel a little groggy. That was the roughest ride I've ever had."

I pointed to the food in the center of the floor.

"Could you stand a little nourishment?"

Linda shook her head.

"Not at the moment, Cliff. I feel too shaky."

I walked over and picked up some chicken and rice. There were chopsticks with which to dig in. I was famished and badly in need of the strength the food would give me.

"We'd both better have some, like it or not," I said.

"It, it might be poisoned, Cliff," Linda said.

I shook my head.

"If they'd wanted to kill us they'd have done so a lot more easily than by poisoning us now." I offered some to Linda, who accepted dubiously.

"Where do you suppose the little Jap captain, Yokura, is?" Linda asked suddenly.

I shrugged.

"He was still alive when I saw him last. They'd dragged him senseless from the car. I imagine he's probably still alive. They'd have shot him there in the pass if they'd wanted to kill him. Instead they knocked him out."

"Do you suppose this will be a ransom kidnaping?" Linda asked.

That was exactly what I was beginning to believe. But I shook my head.

"No. I don't think so." There was no sense in further alarming Linda. "It occurs to me that the bandit Mongols wanted Yokura more than they wanted us. Otherwise why would they have known that a Japanese officer was traveling through the pass in an automobile?"

"Perhaps they're Nationals?" Linda wondered. I shrugged.

"But there would have been no sense in their taking us along if they were Chinese Nationals," Linda went on thoughtfully. "They'd have known we were neutral members of a medical unit. And besides, those weren't the uniforms of Nationals they wore. They looked more like bandits to me."

I didn't say so, but our captors had looked neither like bandits nor soldiers to me. They looked somehow incongruously fitted to the locality, the circumstances, and the situation. But I kept my doubts from Linda.

"I'm fairly certain they're Nationals. Marauders, perhaps, with a mission to harass and delay the Japanese advance until the Nationals could make another stand at the next town."

Linda shook her head. "I wonder," she said reflectively.

So did I. And then, suddenly, there was a sound outside our little cell that indicated our doubts on the matter would be cleared up pretty shortly one way or another—footsteps, then the rattle of a key in the lock of our door!

I looked at Linda. She managed to smile.

"Now we'll know," she said.

I nodded, unable to take my eyes from the door. Suddenly it opened, swinging inward, and a tall, thick-shouldered figure stood framed in the doorway. A figure dressed in thick sheepskin boots, a furry, peaked Mongol hat, and a long, black mandarin gown. He was swarthy-complexioned, with black, shaggy eyebrows, a long, thick, drooping black moustache, a flat wide-nostriled nose, and a square, solid chin. He smiled at us, revealing yellowed, jagged teeth.

"You feel somewhat better after dining?" he asked. His English was without a trace of foreign accent.

I nodded stupidly.

"That is good," he said. "I hope our humble fare did not disgust you too much."

I just stood there, jaw agape, trying to make this out.

"Who are you?" Linda asked suddenly. "And where are we?"

The huge, thick-shouldered, droop-moustached fellow smiled again.

"I am General Moy," he said. "My soldiers unfortunately implicated you two in their raid on the invader scouting automobile. As for where you are at the moment, let us say that you are in our small, but well-hidden city."

I was frowning. Moy. General Moy. There was no General Moy in this sector. And as far as I knew there was no General Moy within three provinces of this sector. In addition to that, his costume was also puzzling. Most oriental war lords affected western military uniforms, no matter how small their command.

General Moy saw my frown.

"I see I am somewhat of an enigma, eh?" He smiled affably. "No matter, I can understand your bewilderment. You were probably equally uncertain as to the origin of my soldiers." He touched his long, drooping, black moustache. "The Japanese captain Yokura was also exceedingly baffled by it all."

"When can we expect release, General?" I demanded. "Obviously your soldiers weren't aware of it, but I'm sure you realize that we're members of an American medical unit working among the war-torn cities of your people."

General Moy nodded pleasantly.

"I am aware of that. You are Doctor Saunders. The young American girl is Miss Barret. I am sorry to say, however, that we must detain you here for several days. But you will be extended the full courtesies at our command."

"Several days?" I asked.

General Moy nodded again.

"Until one of my, ah, contemporaries arrives here. I believe you've met him. I speak of General Wong, in command of the Nationals in this sector."

"You are working with General Wong?" I asked.

General Moy smiled.

"Not exactly. But General Wong will be here shortly, thanks to some very valuable information we, ah, extracted from the Japanese captain, Yokura."

I WAS beginning to get some slight idea of what was going on.

General Moy apparently had a hunch about Wong's probably

deliberate effort to allow the Japanese to take control of this

sector. Perhaps General Moy was sent here especially to take over

Wong's command. But why in this fashion? Why so circuitously?

General Moy again read the bewilderment I felt. He smiled.

"In a little while," he said, "you will probably understand more about this situation. In the meantime, providing you have eaten enough, I will ask you to come with me."

I looked at Linda.

"Miss Barret also," General Moy assured me.

"Very well," I said, and with Linda beside me, and General Moy leading the way, we stepped out of the room. There was a corridor just outside the door of the room in which we'd been held. And we walked down this for perhaps fifty yards to a door at the end.

General Moy opened this door, and a sudden chilling blast of cold night air sent a shiver up my spine. We were out in an open court. An open court perhaps two hundred yards long and a hundred yards wide. There were soldiers and Mongol horsemen off in the far corner in front of what seemed to be a long row of buildings resembling barracks. And straight across from us, in the direction General Moy was leading us, was a tall stone structure built in pagoda style.

"This is the heart of our little city," General Moy said. "We are sheltered by high stone walls on all sides. There is a central gate back beyond those barracks. It's the only entrance. The walls, incidentally, are manned by our finest marksmen."

"But how large is the, ah, city?" I asked.

General Moy waved his hand.

"About a square mile in all. We're on a mountain plateau, you see."

I looked at the construction of the buildings around the court, particularly the construction of the pagoda-like palace toward which the general led us. There were unmistakable signs of antiquity in the design, color and condition of the stone structures.

"If you don't mind my asking," I said, "how far are we from Tinchan?"

General Moy seemed perfectly at ease to answer.

"Less than a night's ride," he replied.

This was another enigma. Tinchan was close to the mountains, I knew. But with all the knowledge I'd thought I'd had about the vicinity, I had never heard anything about another city, ancient or occupied, being within such a short distance.

"These buildings seem to date back to ancient Mongol vintage," I remarked.

"Many things around here do," General Moy answered with a peculiar smile.

WE were less than fifty feet from the pagoda-like structure

now, and two Mongol soldiers appeared at the entrance, holding

rifles. They saw General Moy and brought their weapons to a

peculiar posture of attention.

We passed through the entrance and into a small hall, lighted only by a single torch before another door. But in passing the soldiers who stood guard at the entrance I'd had time to observe two more peculiarities. The faces of the soldiers were of distinctly Mongol strain, and the weapons they held were over half a century old.

We paused before the second door. General Moy opened the door and stepped back.

I gaped foolishly. We were staring down a wide, brilliantly torch-lighted aisle of pure white marble. It was all of a hundred yards long, and the center of a palace room that must have been fifty yards wide. The torches were placed every few feet along the side of the aisle, making it a blazing pathway of dancing light.

Somewhere a gong, deep and echoing, sounded forth. There was a sudden almost overpowering scent of heavy incense in the air. Linda grabbed my arm.

"Cliff," she whispered excitedly, "Cliff, at the end of the aisle—"

And then I saw her—the creature at the end of the aisle. The beautifully-costumed woman on the exquisitely-carved throne of jade. From where we stood she looked like a miniature model of a priceless Chinese carving. She was garbed in mandarin robes of rich gold and purple texture. On her head she wore a tiara of pearls, a crown worthy of a Chinese princess.

I shot at glance at General Moy. He was bowing low, head almost to his knees, arms crossed.

"Our princess," he murmured softly.

WE moved down that aisle almost in a trance. Linda still had my arm. Our steps were faltering, uncertain. The scent of the heavy incense grew stronger. It was as if we walked in an ancient and long forgotten world. And the woman on the throne of jade was more beautiful than music.

She was smiling when at last we stood before her throne. And it was with a start that I realized she was a girl of no more than twenty. The head-dress she wore concealed her hair. But the delicate almond oval of her features, the exquisite line of ripe, red loveliness that was her mouth, and the veiled centuries of mystic knowledge in her eyes gave her a splendor and magnificence that was utterly timeless.

"You are welcome here in the city of Khan," she said. Her voice was quiet, yet musical, like the tinkling of tiny bells. There was no trace of flaw in the liquid English she spoke, and yet I detected the faintest sing-song reed to her inflections.

I stood there stupidly, thinking of something to say. "I am Tangla Khan, daughter of the Conqueror, Genghis Khan," she said.

"Descendant of Genghis Khan?" I blurted.

"Daughter of Genghis Khan," the incredibly beautiful creature corrected me.

I couldn't say a word. I was too stunned. This was too incredible, much along the pattern of a Chinese fairy tale. This girl, scarcely a young woman, calling herself the daughter of China's ancient conqueror!

"You seem incredulous," the girl who called herself Tangla Khan smiled. "In China it is wise never to be incredulous." Again there was that century-old wisdom in her eyes. She waved an exquisite hand in light and graceful dismissal of the topic. "But that is of no great importance."

Of no great importance. As simple as that. But I believed her. Looking down at Linda I saw that she also believed this strangely glorious girl. There was something in her eyes, in her voice, in her every gesture that made doubt of what she said utterly impossible. It was beyond my ken, and far beyond the realm of occidental knowledge, but I had to believe. There was no explaining it, but I knew as I stood there looking up at her, knew the moment the first flash of disbelief had passed, that this indeed was the daughter of Genghis Khan!

"You are both Americans," Tangla Khan went on in her tinklingly musical voice, "and I am sorry that circumstances delivered you here. However, within the next several days you will be allowed your freedom. I should like to grant it sooner, but the wait is necessary."

Somehow I'd found voice, and instinctively I was again trying to pierce the veil of this now incredibly staggering mystery.

"We must wait until General Wong is delivered into your hands?" I asked.

FOR an instant the warmth left Tangla Khan's cheeks and her

eyes flashed fire. It must have been the mention of Wong's name.

For suddenly her composure returned. She nodded slowly,

gravely.

"I see that General Moy has told you we are expecting the arrival of the venomous General Wong. Yes, that is true. My soldiers have already arranged a rendezvous with the traitor."

"But—" I began.

Tangla Khan held up her graceful hand, cutting off my words.

"There is much about China that the occidental will never understand, Doctor Saunders. You find yourself tangled in a web of baffling circumstances. But do not endeavor to untangle the web too strongly. There are mysteries which you could never unveil. It is probably just as fortunate." She smiled again.

Somewhere a gong sounded, its muffled echo drifting faintly to us. The scent of perfumed incense seemed to be drifting away.

"Before you leave us," Tangla Khan declared, "I shall see you both once more."

This was a dismissal, I realized. And then Linda and I were moving dazedly down the long aisle of marble, through the brilliant archway of torch-light, back to the door by which we'd entered.

General Moy stood there, head still lowered, waiting for us. As we approached him he raised his head. Then, gravely, he stepped to the door, holding it as we went out.

In the hallway General Moy closed the door of the palace room behind us. Then he turned. Silently the three of us went past the sentries at the outer door.

We were out in the courtyard again. The chill night air was suddenly fresh and invigorating. I felt as though I'd been hypnotized, mesmerized into another world. Now the spell was broken.

Linda was the first to speak.

"I can't help but believe," she said softly, half-incredulous at her own words.

"We who follow the leadership of the daughter of Genghis Khan can believe," General Moy said quietly.

"But she was just a girl," I murmured bewilderedly.

"With centuries of knowledge, centuries of wisdom," the general added. I turned to look at him. His mouth was grave, and in his eyes there burned the flame of fierce fanaticism. "And all put to the aid of China," he concluded.

I felt a sudden chill. It wasn't from the dampening cold.

I turned again to General Moy.

There were some questions I wanted to ask him. Questions as to why we had been permitted this audience with Tangla Khan, why, in fact we were so unhesitatingly permitted the freedom of this mysterious city of Khan. After all, we were foreigners, unknown foreigners at that, even though our sympathies had been obvious.

I was about to ask this of the general when the silence of the courtyard was suddenly broken by a swift clatter of hoof beats in the distance.

General Moy cocked an ear.

"My horsemen," he observed, "at the gate to the city."

Through the night there came a weird, half-human cry.

Moy nodded.

"They signal the password to the gatemen."

Moments later the hoofbeats took up again, growing louder and louder. Then riding single file into the court in which we stood, came a party of ten soldiers astride Mongol mounts.

They halted about fifteen yards from us.

"Look," Linda cried, pointing to the lead horseman's saddle. I looked, and saw a fat human burden, tied and gagged, strapped crosswise over the pommel of the saddle. Even from that distance and in the half-darkness of the courtyard I could recognize the prisoner General Moy's Mongol scouts had brought with them. It was the Nationalist general, Wong!

Soldiers were hurrying out of the buildings that looked like ancient barracks. Some carried torches, and soon the courtyard was well lighted and teeming with General Moy's troops. The general had left our side and advanced to meet his returned scouting party.

The Mongol warrior who'd ridden the horse to which General Wong had been lashed was unstrapping his captive and dragging him quite unceremoniously off, letting the fat, uniformed body tumble to the ground.

And now the mandarin-costumed General Moy stood towering above the trussed and helpless figure of the traitorous captive.

"Welcome, esteemed general," Moy said loudly.

The ring of soldiers pressing around him laughed loudly at this. Then Moy barked something in Chinese, and several soldiers were bending over the fat figure of General Wong, untying his bonds and helping him roughly to his feet. In the flare of the torch-light I could see General Wong's moon face, flushed with wrath and covered with grime. His faded blue uniform was tattered and badly soiled.

He stood there in the middle of his captors, facing General Moy uncertainly and yet with a certain bluster of braggadocio, a desperate effort at front to conceal the terror he undoubtedly felt.

"You had an appointment with a certain Japanese captain, Yokura," General Moy was saying. "We have seen to it that you will not miss that appointment, Wong. Captain Yokura is here."

GENERAL WONG seemed suddenly to sag. He looked helplessly from

face to face in the ring that encircled him.

"The two of you, Captain Yokura and yourself, can keep your rendezvous in the Temple of the Dragon," General Moy went on coldly. "It will be fitting."

General Wong's face went ashen beneath his pockmarks. Stark terror filled his eyes. He opened his fat lips, seeming to strangle on the words he was trying to say.

"No," he choked in Cantonese, "No! It is not so! It cannot be so! By the graves of my ancestors I swear that I am an innocent man!"

General Moy touched his drooping black moustache. Contempt was in his voice.

"Your ancestors were dogs, Wong. They died unburied!"

Wong was shaking his head from side to side like some squat grotesque rag doll.

"No, no, no," he kept repeating.

"Prepare the pig for the Temple of the Dragon!" General Moy suddenly barked. Then the circle of Mongol warriors closed in around General Wong, dragging him off toward the barrack buildings at the other side of the court. Moy stood there watching them for a moment. Then he turned and came back to us.

"A traitor," he remarked almost conversationally, "is a most unhappy person in China."

"Then Wong was a traitor?" I asked.

General Moy nodded.

"He had been taking silver from the invader forces in this sector for some time. We knew that. Captain Yokura of the Japanese was to meet him tonight in a mountain rendezvous. We extracted that information from Yokura and met him ourselves instead. Quite a surprise party for General Wong."

"You will execute Wong?" I asked.

General Moy gave me that peculiar smile again.

"You might call it that," he said.

I could feel Linda's arm near mine. She was trembling visibly. The strain had been too much. General Moy saw this also.

"It might be wise to take the American Miss to her quarters. She is badly in need of rest," he said. "You will not be locked in, this time, and our small community will be at your service." He bowed slightly from the waist. "If you will excuse me," he begged. Then he turned away and started toward the barrack building to which Wong had been taken.

I put my arm around Linda's waist, and she seemed grateful for support as we crossed the courtyard to the building where we'd first been quartered by General Moy's forces.

"You've gone though a great deal in the last few hours, Linda," I said solicitously.

Linda shook her head gamely, red hair glinting in the torchlight of the hallway as we entered the building.

"Not so much," she said. "I guess I haven't got much of what it takes, Cliff. I could stand the shells and the gunfire and the hospitals and blood. But this mystical whatever-or-other-it-is coming on top of all the rest is a little too much. That girl—she was beautiful, wasn't she, Cliff?"

"You believe that she is the Conqueror's daughter?" I asked.

Linda nodded.

"Don't ask me why, Cliff. But I do. I can't help it. I know it's impossible, but—"

I nodded.

"Yes, I know what you mean. I feel the same way." I paused. "The daughter of Genghis Khan, fighting for China's freedom. It's more than incredible."

WE were at the room to which we'd first been taken. I opened

the door.

"We should be freed tomorrow," I said. "Wong has been captured, and that was all they were waiting for."

Linda looked up at me.

"Yes," she said faintly, "tomorrow."

"Good-night, Linda."

"Good-night, Cliff."

I looked down at her. At the lovely little nose, into her clear, clean, blue eyes. Her lips were half-parted. I felt something akin to dizziness. Then, without intending to, my arms were around her and my lips were against hers. I stepped back after a moment, shaken.

Linda was looking solemnly at me.

"You're a strange duck, Cliff," she said. "Brilliant medico with nerves of steel. Nothing seems to affect you, even the situation in which we now find ourselves. I think you're even too preoccupied to be aware of what's happening in your heart." She closed the door of her room softly.

I stood there, still shaken, staring dumbly at the door. Wondering at what I had done, trying to get sense out of what she had said. There was another room down the hall, and the door was slightly ajar. I stepped inside. It had been prepared for me. There was fresh grass matting on the floor, and food and water and a package of American cigarettes.

Picking up the latter I opened them mechanically, lighted one. But thoughts of sleep or rest were impossible. I decided to get some air. I felt as though I needed it badly.

There was no one in the courtyard when I stepped outside. I walked along, smoking and trying to throw this strange quilt-pattern into a semblance of regularity. This mysterious city, the baffling enigma of General Moy and his leader, the beautiful Tangla Khan. None of it would fit properly.

I was a doctor. My life, since I'd been in China, had been filled with nothing but the unceasing grind of my work in the war sectors. This was the first time I'd been thrown out of pattern in four years. And now there was Linda. For the first time Linda appeared as a woman to me. Before that she'd been nothing more than a valuable aide in my all consuming work. That was out of pattern, too.

And so I walked along, scarcely noticing where I was going, trying to set the confusing series of events straight in my mind, trying to argue myself into a logical state of mind.

Before I realized it, I was at what must have been the end of the little city. There was a tall stone wall before me. It was the protection General Moy had mentioned. I looked along the wall for the entrance. I couldn't see it. Probably at the other side of the city.

I started to turn away, was fishing for a cigarette, when my foot struck something in the shadows. Something solid. Something like a body. I bent down, then gasped.

A Mongol warrior, obviously one of the wall guards, lay there with a knife in his ribs, definitely dead!

I felt the fellow's hand immediately. It was still warm. My fingers found the wound. The blood was still warm. This guard had been killed less than fifteen minutes ago!

A thousand and one conjectures flooded my mind. Had one of General Moy's captives, say Wong or Yokura, escaped? Or had someone stealthily entered the city?

I didn't know. But there was one thing to do. Tell Moy immediately. I looked around. There were no Mongol warriors in sight. I began to run toward the center courtyard. I was breathless when I arrived there. There were no soldiers in the court. I dashed toward the line of barrack buildings. There seemed to be no one there. The pagoda-like building across the courtyard: Moy and his troops must have gone there for some reason. I dashed back across the courtyard. The first door of the pagoda was open slightly. I stepped inside.

Thin, eerie, reed-like music suddenly came to my ears from behind the second door: the door to the palace room of Tangla Khan. And then I heard a low, almost whispered, chanting. Many voices seemed to be providing a background for the reed-like music. I tugged at the door. It seemed locked, or stuck.

The music inside was louder, and so was the chanting. A great gong sounded dashingly. The music grew stranger, faster, the voices catching the beat and rising in pitch. I tugged frantically at that door. It suddenly opened, almost throwing me off my feet.

General Moy's warriors were in Tangla Khan's throne room. They filled the place on either side of the long marble aisle, sitting in the darkness. They were the chanters.

But at the end of the long aisle was no longer the jade throne of the daughter of Genghis Khan. In its place there was now a wide marble platform almost twenty yards in diameter. At the front of this platform, and crouched below it, were the musicians whose instruments were producing the eerie music.

And on the platform itself, centered by the brilliance of the torchlights all around her, was Tangla Khan, daughter of the Conqueror!

She knelt beside a vase, swaying and undulating to the rhythm of the music and the chanting. Instead of the heavy trappings of the mandarin costume she had worn before, Tangla Khan was now clad in the briefest of barbaric sacrificial costumes, displaying a body that was more beautiful than a cutting in jade.

And now the music was swelling, the voices rising even higher, and for the first time I noticed that the vase beside which the daughter of Genghis Khan knelt was emitting a greenish vapor that writhed toward the ceiling.

I stood there frozen, hypnotized by what I saw and heard.

Tangla Khan undulated her glorious body in a manner that was like flowing liquid, her graceful arms tracing patterns through the greenish vapor of smoke coming from the throat of the vase.

And suddenly I noticed for the first time that two men, the general, Wong, and the Japanese captain, Yokura, were tied to pillars of marble in the darkness just off to the right of the platform!

The chanting was almost at a frenzy pitch, and Tangla Khan continued to sway, as if actually moved by the force of the swelling music. And the greenish vapor of smoke was taking a tangible form!

I saw the green head and blazing eyes at first, then the winged part of the smoke-spawned Thing. A dragon, a green monster from hell, was materializing from the vase!*

[* Cliff Saunders was watching the ancient Chinese Rite Of The Dragon, a ceremony dating back in Asiatic history to the days of Genghis Khan, the Conqueror. The Rite Of The Dragon, banned by the ruling Chinese dynasty in the year 1100, was a ritual designed to seek the help of the worshipped dragon in gaining victory for China over her enemies. The offering of a traitor as a sacrifice to the dragon god was deemed essential to the ceremony, for it was only after feasting on the blood of one who had betrayed China that the dragon god was supposed to hear the plea of its supplicator.

Records of this ancient ritual can be found in the 12th volume of Copperling's History of China. The exact nature of the sacrifice, even to the incantations of the rite, is most fully elaborated on, however, in the historical tomes of Chinese legend to be found in the Tibetan monasteries. There, preserved by the venerable monks for many centuries, the complete record of the dragon rite was made known to Marco Polo in his famous journey. Mention of the dragon rite has been found in Polo's writings. —Ed.]

And from the darkness at the side of the platform, where Yokura and Wong were tied, there rose above the wild chanting and wilder music the most hideously soul-piercing scream a man has ever uttered!

For the monstrous dragon hovered directly over General Wong, hanging suspended there for a horrible instant, and then wrapped its hideous wings around the traitor, enveloping the poor devil completely!

I saw that Yokura, tied to the next pillar, was slumped limply in his bonds. Undoubtedly he'd fainted.

The voices in the throne room were raised to screaming frenzy. Tangla Khan was rising from her knees, now, still dancing, a savage, primitive fury in her rhythmic writhings.

And suddenly a deafening explosion shook the pagoda to its very foundations. Then another explosion, followed by a staccato of machine gun and rifle fire.

The chanting faltered, stopped. On the platform, Tangla Khan stood transfixed. The materialization of the dragon had vanished the moment the chanting had faltered. A small wisp of green smoke rose from the vase. But in the shadows the remnants of what had been General Wong splattered the white marble of the pillar, to which he'd been tied. A grizzly reminder that the Thing had been more than a materialization!

The deafening explosions were increasing now. There was shouting in the courtyard, and the soldiers in the throne room were on their feet, swarming toward the door, milling past me, crushing forward in an effort to get outside.

And I suddenly recalled why I'd come here. The knifed guard by the wall and this confusion outside meant that attackers were inside the gates of the little city of Khan!

Sickly, I recalled that Linda was alone and unprotected across the courtyard. I hurled myself against the swarm of bodies pressing toward the pagoda exit. I had to get out. I had to reach Linda!

WILDLY I fought and clawed my way through the press of bodies all around me. Suddenly I was out in the courtyard. There were more explosions. Somewhere a machine gun was chattering. And then I noticed that Mongol warriors on every side of me were falling.

The machine gun was directed by the attackers at the pagoda exit. General Moy's men were being slaughtered as they swarmed out into the courtyard. Tiny spurts of dust flicked everywhere around my feet.

But I was running, heedless of this, along the side of the court, trying to work my way around to the building in which I'd left Linda. I stumbled and fell sprawling across the body of a Mongol warrior. My hand touched a sack at the fellow's side as I rose.

Grenades!

I bent down quickly, fishing in the sack. They were the old pin-type grenades. But they were weapons. Weapons this Mongol would never throw now. I waited beside the body, listening, peering through the flashing darkness until I located the position of that machine gun.

Then I pulled the pin, hurling the grenade across the court. There was another deafening explosion. The machine gun was silent. Only rifle fire barked now.

I waited, crouching low, listening to see in what direction the rifle fire was centered. Then I dashed forward again to the concealment of a short stone watering trough less than fifty feet from the building I wanted to reach. There was a dead soldier behind the trough. A Jap. So the attackers were all, or a part, of Yokura's regiment who'd trailed his captors to here!

The slain soldier of Nippon had a rifle he'd no longer need. I grabbed it up, waiting for a pause in the staccato of rifle fire.

Then I was dashing across the fifty feet of courtyard that lay between the trough and the building where Linda was. I could hear the zinging of rifle bullets whining past my head. I was at the door, tugging it open.

Something struck me in the shoulder, flattening me against the door. I felt warm stickiness trickling down my skin. But that was the only other sensation. No pain. I hadn't time to think of pain. I had the door open now, was inside the corridor, slamming it behind me.

I was breathless and a little weak. My white shirt was red at the shoulder. A soldier of Nippon appeared in the corridor, staring at me in surprise. I fired the rifle I held from the hip. He pitched over on his face and the corridor rang from the explosion of the shot.

The door of the room in which I'd left Linda was ajar. I reached it and a helmeted head suddenly appeared. I fired point blank into the face. The Jap didn't even have time to scream. He fell backward as if in slow motion, both hands covering the gruesome red smear that was blotching over his features.

Linda was in the room, standing back against the far wall, eyes filled with terror. There was no one else.

"Cliff, oh Cliff," she cried.

I had my arms around her. "Are you all right?" I kept demanding. "Are you all right?"

Linda nodded, sobbing, holding close to me, burying her face against my bloody shirt.

"Cliff," she sobbed, "you're hurt."

WE were out in the corridor again. There was no one there but

the Jap I'd killed as I entered. He lay face downward on the

floor. Then I saw the machine gun. The two of them, the Jap

soldiers, had entered this building to place the gun here to

cover the courtyard. They had encountered Linda accidentally. I'd

arrived in time.

The gun was mounted on a tripod. The Jap had been standing before it when I'd entered. There were ammunition feeding belts. I dragged the gun to the doorway. Then I went back for the Jap soldier I'd shot in the face. I dragged him from the room and placed him by the door. I got the other body and placed it on top of the first. It was the only barricade I could think of.

I had the machine gun ready behind them, snout pointing over the buttress of bodies.

"Linda," I said. "Get back in the room!"

But she had dropped to her knees on the floor of the corridor beside me. She was already inserting the ammunition belts into the gun.

"Two comprise a gun crew," she said.

I looked at the set of her lovely jaw. There'd be no forcing her to take shelter in a room.

"Okay, honey," I conceded. "But for God's sake keep your head down."

I reached forward and swung the door open. We had perfect command of the entire courtyard. I'd taken my position behind the gun. But I waited an instant or two. I could see General Moy's Mongol forces firing from the pagoda. The panic and disorder that had swept them as they'd piled from the temple was now gone. They'd organized a firing line from the pagoda itself. The men they'd lost lay sprawled in the center of the courtyard.

The Japanese troops were firing from a battle line on the other side, before the barrack buildings. Their flank was exposed to the muzzle of my machine gun.

"All right, Linda," I said. "Here we go!"

I triggered the gun, blazing forth at the Jap line. The fire was devastating.

THE machine gun chattered, eating smoke lines of death along

their ranks. Soldiers tumbled sprawlingly in every direction.

Panic-stricken, those left in the firing line rose and dashed for

the shelter of the barracks buildings.

I cut them down as they ran, mowing their legs from under them. It was sickening carnage, but it was our lives or theirs.

And then there was an increased volley of fire from General Moy's Mongol warriors in the pagoda. Ten of them dashed down to the front of the temple, kneeling there, firing at the barracks buildings. Ten more tumbled out, dashing past their comrades who were covering their movements. They stopped about fifteen yards on, dropping to their knees and opening fire in the same manner as the first group.

The first group rose, dashing on some twenty yards beyond the second, who now covered their action. Then they dropped on their stomachs and picked up the fire. They were working toward our building. Now I understood what was afoot. Moy had ordered this retreat from the pagoda the moment he realized that a machine gun had opened fire on his enemies from our building.

The pagoda was a dangerous battle line. General Moy's men were leaving it and moving to our building, which was a much more strategic location. Our building commanded the entire courtyard, the pagoda hadn't had that advantage. Moy was moving his ranks.

More Mongol warriors were leaving the temple, covered in the protective fire of their comrades. I kept triggering the machine gun, giving them all the additional advantage I could. The Jap soldiers hadn't reorganized their firing line as yet. They were still too panic-stricken. Their dead lay everywhere about the courtyard. There was a veritable pathway of them leading to the barracks buildings—all sprawled in various postures of death.

And then I checked my machine gun fire, for the first of the Mongol warriors reached our building. They deployed around the sides of the door, then, keeping up their fire to give their comrades a chance to come up.

I began firing again, and from the corner of my eyes saw the last of the Mongols dash from the temple. General Moy was with them, and a small, slim, uniformed figure that could be no one but Tangla Khan.

Linda fed the cartridge chains endlessly into the machine gun all this time. And mentally I was thanking God that the Japs hadn't reached us with their retreating fire. She was completely contemptuous of the danger she risked, utterly disregarding my warning to keep out of range.

THE gun was beginning to smoke now, and the barrel was almost

red-hot to the touch.

Two Mongol warriors came from the firing line before the door, signaling me that they'd take over the gun. I relinquished it gladly, for now I'd be able to get Linda out of the way.

I picked up the two outdated rifles the Mongols had dropped, gave one to Linda.

"Come on," I told her. "We'll get back until Moy reaches us." She hesitated. "Those two will know what to do with the machine gun if it gets too hot," I told her. "I couldn't manage it, and there's no sense in burning it out."

Linda nodded, stepping back with me into the corridor. She was breathing heavily, and her face was smudged with the soot of gun powder. She took me by the arm.

"Come, Cliff. We're going to bandage that shoulder right now."

I started to protest, but it was something that would keep her out of danger for a little while. I nodded.

We went into the room where I'd found her. She turned her back on me for a minute and when she turned around again she had four swatches of silk which she'd torn from her slip.

"For once the doctor is the patient," she said. She tore away the shirt from my shoulder.

"Linda," I said, "forgive me. It's all my damned stupidity that got you into this mess."

"Stop talking, Cliff, and stand still. I wanted to be here. I wanted to be with you. Never thought I'd have to tell you that, but there it is." She was busily swabbing the wound.

I didn't know what to say.

"You're a strange duck, Cliff. I said it last night and I'll say it again," Linda declared. I didn't know whether she was talking to keep me from noticing the fact that my shoulder was badly creased, or actually trying to tell me something.

I didn't know how to answer that. But I had to say something. I told her about finding the Mongol guard by the wall. I glossed lightly over what had happened in the temple—the part about the monster and the hideous fashion in which it had eliminated Wong. I omitted that.

Linda had slept after I'd left her, she told me. The firing at the edge of the city had roused her. She had just dressed when the first explosions started. It was shortly after that that the Japs had entered the building to mount their machine gun. In prowling about the place to make certain they were safe from a rear attack they'd burst into Linda's room.

It must have been terrible for the girl. But her recounting of the incidents was brief. I had broken in just as the Jap I'd shot in the face was starting after her.

The thought of what a few seconds delay in my arrival would have meant made me sick and shaky inside.

FOOTSTEPS were clumping into the corridor, now. Linda finished

dressing the wound.

"I think you'll live, Cliff," she smiled. Linda Barret wasn't lacking in nerve when the going got tough.

General Moy appeared at the door. He was breathing heavily. He held a mean-looking automatic pistol in his large hand.

"For a doctor," he said, "you made a magnificent machine gunner. And the young lady deserves our thanks also."

"I tried to warn you of the attack, General," I said. I didn't mention the fact that I'd witnessed the ancient and horrible rites in the pagoda.

"Our stupidity," General Moy declared. "Stupidity that cost us several hundred men. We're taking the machine gun up to the roof of the building. There's what amounts to a small fortress up there. We should be able to mop up the rest of the enemy. I've hand grenade hurlers approaching the barracks where the enemy has taken refuge. They'll approach the place from the rear and blow the devils back into hell."

"I'll get up on the roof, then," I began.

"We'll get up on the roof," Linda broke in.

General Moy looked at her in admiration. I shot her a glance of annoyance. But Moy shook his head.

"You'll both remain here. There'll be much you can do when the shooting is over, Doctor."

It seemed strange to hear that last word under these circumstances. I'd been used to being called Doctor for ten years now. A man of medicine, sworn to save lives. And in the last half hour I had taken hundreds of lives.

And then another figure was standing in the door—Tangla Khan, looking as beautiful and imperious in a blue uniform as she had ever been in her temple!

"Is everything in readiness, General," she asked in her musically tinkling tones. She seemed not to notice Linda and I.

General Moy bowed from the waist.

"Everything, Empress."

Tangla Khan looked at Linda and me then, as if she'd just noticed us.

"We owe you great gratitude," she said. "China will not forget what you have done for us."

She turned, then, and left.

"The uniform," I stammered, "wha—"

General Moy was grave.

"Wong is dead. His forces at the foot of these mountains are leaderless, in grave peril. The road of supplies is threatened by the invaders."

"The Burma Road?"

Moy nodded.

"If the troops that were formerly Wong's are massacred, China's lifeline will be in the hands of her enemy."

"But the Japanese forces here—" I began.

"They are but one division of the enemy strength in this sector. They were under the command of Captain Yokura. They fight in our city for a twofold purpose, to release their leader and hold off our brigand brigade until the main body of Nationals are chopped to bits."

"But Tangla Khan?" I asked. "Will she—"

"She will take Wong's command. I am going with her. It is our only chance to repair the damage done by the traitor, Wong. The enemy is closing in on his troops at this moment."

"But the risk you'll run," I said. "It might mean your own destruction."

"China is imperiled," was General Moy's answer.

Moy's words made me redden in embarrassment, realizing the stupidity of my own statement. It was obvious that China's fate hung in the balance, and that for Moy there was no questioning what was to be done.

"But you must break through the Jap division that has you hemmed in your own city," I reminded him.

"I said that hand-grenade hurlers, my best, are flanking the enemy troops in the barracks buildings at this very moment," General Moy reminded me.

There was a sudden explosion. Then another, and a third. The machine gun began chattering furiously. There was a fourth explosion. General Moy stepped into the corridor. From where he stood he had a clear view of the courtyard. I stepped out beside him, Linda with me.

The barracks buildings were a shambles of debris. Smoke hung heavily over the ruins. The grenade men had done their work well. Moy's Mongol warriors had ceased firing. There was only the sound of a few feeble volleys from the Japs still alive in the wreckage of the barracks buildings.

Moy turned. Tangla Khan stood behind us.

"We are ready, Empress," Moy said. "The horses are at the rear."

"You will be safe here," Moy told Linda and me. "The enemy resistance is almost completely wiped out. I'm leaving a superior force to take care of the remainder of them." He shoved his huge automatic into the holster at his belt.

I put my hand on his arm.

"Good luck," I said.

General Moy smiled.

"China will remember," he said.

He turned away, following the slim, uniformed figure of Tangla Khan.

WE watched them step through a door at the end of the

corridor. They were followed by four stalwart Mongol soldiers.

The shooting out in the courtyard was still sporadic.

Occasionally Moy's men on the roof let loose with a staccato of

machine gun fire, and intermittently the remainder of the Japs in

the barrack building ruins replied with sharp rifle volleys.

There was a clatter of hoofbeats on the cobblestones in the rear of our building. The machine gun on the roof began a steady chattering spray of death down at the barracks building across the courtyard.

Then suddenly, past the door that looked out on the courtyard, General Moy, Tangla Khan, and their escort of the four Mongols all mounted, raced past, under the shield of machine gun fire from the roof.

"They're racing toward the gate!" Linda cried.

I held my breath. The machine gun on the roof kept up its steady hail of leaden death. The Japs weren't being given time to pick out targets on the flying steeds. Then General Moy, Tangla Khan, and their guard were out of sight. The machine gun kept streaming lead across the courtyard, giving them plenty of time to get a start.

I relaxed a little. They'd made it.

And then Linda grabbed my arm, sharply, fingers digging into my flesh.

"Cliff," she gasped, "Cliff, good heavens—look!"

I turned in the direction she pointed, peering across the court to the other side, to the pagoda building.

"My God," I gasped.

Captain Yokura, begrimed, unsteady, and bloody, stood swaying at the entrance to the pagoda! In his hand was an automatic pistol. He looked dazedly around the courtyard.

I couldn't believe my eyes. Yokura—still alive!

How he had been spared by the Mongols of Tangla Khan was more than I could imagine. I recalled that he'd escaped the hideous death in the dragon rite when his troops had taken the courtyard and opened fire on the pagoda. But he'd still been tied to the marble pillar in the temple, beside the horribly mutilated body of the traitor, Wong.

Perhaps, in the confusion and tumult that followed the discovery of the Japanese attack on the village, he'd been left there, temporarily forgotten in the effort at organizing a defense. Perhaps he'd freed himself in the excitement, possibly waiting until General Moy's men and Tangla Khan had left the pagoda for the safety of our building.

But he was alive, and the gun in his hand indicated that he was still fighting.

The machine gun on the roof was still spraying the buildings in which the Japs had taken refuge. Obviously the Mongols in command of the gun on the roof hadn't seen Yokura as yet. And obviously the troop of riflemen in front of our building hadn't seen him, for all the fire was being directed toward the beleaguered barracks buildings.

And now Yokura was dashing across the courtyard—dashing toward his troops in the barracks!

It was a distance of less than a hundred yards. Yokura covered more than half the distance, in amazing speed, before the first Mongol riflemen noticed him.

They had to shift position to train their fire.

That gave Yokura another thirty yards. Fifteen left—the little Jap captain running like a deer!

The first shots from the Mongol rifles blazed out. Dust spurts kicked up everywhere about him. But he still ran, apparently untouched. And his men in the barracks were now giving him a sort of covering fire. It wasn't much, but it was all that he needed.

Five yards—and Yokura was hit, fell sprawling to the ground!

He moved on, dust still kicking up all around him. Moved on on his hands and knees, covering that extra five yards as best he could. Three Jap soldiers suddenly dashed out to him, forming a screen of flesh around their captain.

One of them got a bullet squarely in the center of his forehead. The other two closed in the gap, keeping that screen. A second fell, shot in the stomach, and the third was suddenly cut to the ground as the machine gun on the roof opened a belated fire.

But Yokura was inside the barracks building, still alive. The desperate heroics of three of his men had saved his life, and now he was with his troops once more. There was no way of telling how badly he'd been wounded.

Three lives given for the life of their leader; only in a Japanese division would you see such sacrifice!

Linda's face was white.

"My God, Cliff," she said softly.

I shook my head in awe.

"You can call those little yellow devils almost anything, and they'll deserve most of it, but they aren't cowards."

There was a lull in the firing, such a pronounced lull that everything seemed so eerily silent you wanted to scream. The Mongols were holding off rather than waste their fire now, and the Jap troops were probably getting a back-stiffening by Yokura—if he were still alive.

There was an itchiness, an unpleasantness, to the silence.

"What do you suppose they're up to over there?" Linda said, and instinctively she whispered.

I shook my head.

"There isn't much they can do," I answered. "Moy's forces have the upper hand. The Japs must have lost half their division in that grenade assault by Moy's men. Perhaps Yokura will make a retreat. It's the smartest thing to do."

Suddenly, out of the silence, came a muffled, throbbing roar. It issued directly from behind the barracks building. It could come only from there. It was the roar of an automobile motor! And then I realized. Of course Yokura's division had one, or two, scout cars. Perhaps they were armored, perhaps not. But now I had an idea of what was up.

"Cliff," Linda said, "will they—"

"Yokura's probably been told of Tangla Khan and General Moy's flight to the side of the Nationals," I answered, thinking swiftly out loud. "Ten to one he plans to go after them, in a scout car, banking on the very good chance that he'll be able to overtake a party on horseback!"

I'D hardly spoken the last words when an increased throbbing

from the car behind the barracks arose, and the snout of a

gray-and-black open scouting car appeared around the building's

edge.

They had a scout car, but it wasn't armored and was heading for suicide. For there was only one way to the gates of the village, and that lay in a direct path of fire through the courtyard. Yokura must have been insane. General Moy, Tangla Khan, and the rest of their mounted party had been able to make it through the courtyard because of the advantage they'd had in having machine gun fire to protect them from counter volleys by the Japs. But Yokura and his men didn't have a machine gun to cover their dash.

And not only did they lack this strategic necessity, but they were making their desperate escape through a hail of enemy machine gun fire—something else Moy's mounted dash hadn't had to face!

"God knows they aren't cowards," I exclaimed in awe.

And then the scout car—widely exposed to the Mongol fire—thundered out into the open courtyard, turned sharply, and started in the direction of the village gates.

I had only time to see that three Jap soldiers sat in the front of the car. Three more in the back, one of them in an officer's uniform—obviously Yokura.

Then the machine gun on the roof opened fire, followed by the volleying blasts from the riflemen before our building. It was red, gruesome carnage. They didn't have a chance.

The soldier behind the wheel got it after less than three seconds. The soldier next to him, as if he'd been expecting it, grabbed the wheel and carried on. He lasted two more seconds. Then the third soldier in the front climbed across the bodies of his dead comrades and seized the wheel. There was no effort from those in the back of the car to fire defensively.