RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

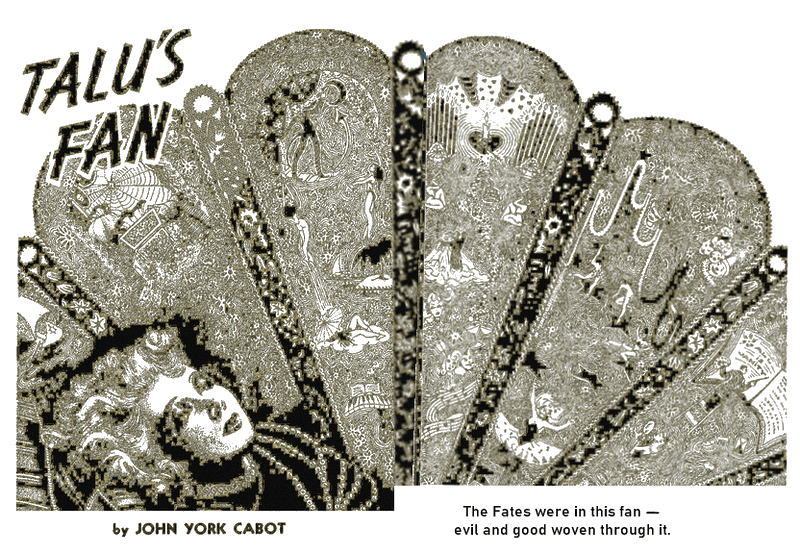

Fantastic Adventures, November 1942, with "Talu's Fan"

Robert Wetton's life became very interesting when

he received the

gift of a strangely evil but amazingly beautiful and cabalistic

fan.

YOUNG Robert Weston, eager and excited at his first taste of diplomatic service, arrived in Hong Kong very early in December of 1941. At the time of young Weston's arrival, that seething cauldron known in newspaper language as the "far eastern situation" had not quite bubbled over to scald an already badly burned world.

Fresh from that eastern seaboard college which so admirably trains young men for diplomatic service, Weston had the blond, athletic scrubbed appearance of a collegiate oarsman. He had, too, an amiable, disarming guilelessness about him which was evident in the candor of his clean blue eyes and the heartiness of his handshake.

He was the perfect man for the task which lay ahead of him; even though he hadn't the slightest idea of what it was all about.

His orders, which he was not permitted to open until his ship had left San Francisco, were extremely simple ones. They stated that he was to take residence in a certain Hong Kong hotel and spend his first week in that city as he pleased. By no means, his instructions stated, was he to communicate with his diplomatic superiors in Hong Kong until the end of his first week there.

Young Weston had read the orders, frowned briefly, then shrugged. With all the excitement in the air, he decided, they would probably have no time for him right off at the Hong Kong consulate. Too, perhaps they wanted him to spend the first week on his own so that he could acclimate himself comfortably to his new surroundings before settling down to work.

At any rate, he figured, it would be fun to have that week in which to prowl about on his own and observe first hand the mysteries and glamor of that legendary city. Hong Kong—the very color of the word itself thrilled him!

IN one respect concerning his orders, young Weston had been

right. His immediate superiors on the diplomatic staff at Hong

Kong were indeed extremely busy. One of the focal points of a

seething international situation, they worked like madmen night

and day. Red-eyed, yet not daring to tire, they drove themselves

endlessly at the tremendous tasks which confronted them

hourly.

But they were not too busy for Robert Weston. In fact, had it not been for the task they'd already selected for him, they would have welcomed his addition to their overworked staff immediately on his arrival.

"It's best that we do it this way," Martin Holliday, gray-haired official of the staff told his trusted assistant. "Young Weston's casual arrival, his week without so much as coming within a mile of this office, and the fact that he will undoubtedly behave like a naive and wild-eyed tourist, will all serve to throw any suspicion away from him."

His assistant nodded at this.

"We've a man ready to send us word the instant young Weston checks in at his hotel," he said. "Do you think it wise that we keep someone detailed to watch him—just in case the youngster should wander into trouble?"

Martin Holliday shook his head wearily.

"No. We can't afford even to run that risk. Our men are all under careful watch. If it were known that one of them was keeping track of young Weston's movements the first week, Weston, too, would fall under suspicion. His value then would be utterly destroyed."

The assistant nodded again. "Now about that Washington cable," he began.

Holliday ran a tired hand through his gray hair, sighed, and rested fully twenty glorious seconds before driving himself back into the avalanche of work ahead ...

IN another section of the island metropolis, young Weston's

arrival was also tensely expected. But the reasons behind this

anticipation were somewhat conflicting with Martin Holliday's.

The reasons were of quite immediate personal concern to a dapper,

gold-toothed yellow complexioned little man with slanted eyes and

sibilant speech. His name was Mr. Shido, and the lithe, cat-like

grace with which he strode back and forth in the woman's

apartment, belied the brutality and treachery for which he had

become notorious in certain Manchuko espionage assignments. Mr.

Shido was in Hong Kong precisely because of matters concerning

the arrival of young Robert Weston. It was his first assignment

in this metropolis, and he was most eager to please the Son of

Heaven by his handling of it.

"The moment the young American arrives at his hotel I will send you word," Mr. Shido told the woman, "Certain leaks in their stupid consular office lead me to believe his arrival will be of this afternoon."

The woman was blonde, and almost incredibly beautiful. Her skin was ivory tinted and her brown eyes not quite almond in their loveliness. She wore an occidental afternoon dress, the clinging lines of which did little to conceal the voluptuous promise of a god-moulded body. Asia had given to her all the exotic allure of sensual incense; Europe had lent an occidental piquancy, and the result of both had made her the most dangerous woman of all castes—the Eurasian tigress.

Mr. Shido paused in his pacing.

"Is it all quite clear, Talu?" he demanded.

Talu's graceful golden fingers lifted a long cigarette in a jade holder briefly to her lips. She caressed the filmy blue pattern of smoke she exhaled with rich, moist lips.

"It is all clear," she said. "Within eight hours of this young American's arrival I will have become acquainted with him." She smiled to herself at the verb she had chosen.

Mr. Shido sucked back his breath in the manner of his race.

"Good," he declared. "From that moment we can make all plans in accordance with necessity." He strode to a teakwood table and picked up his panama hat. He paused at the door a moment before leaving, his slant eyes regarding the sensual allure of the woman reclining on the heavily cushioned divan.

"I think we shall have little trouble," he decided. "I will talk to you again tomorrow. Sayroonerah."

"Goodbye," Talu said.

When he had gone, Talu lovingly lifted a small, exquisitely fashioned oriental fan from the low table beside the divan. Flicking it open, she gently swept it back and forth before her face. Such pigs, these little Japanese. But then, she shrugged mentally, they paid so handsomely for what they wanted...

THE well-informed Mr. Shido had been correct as to the

time of young Weston's arrival. His boat docked that afternoon,

and inside of an hour the young man was comfortably settled in

his hotel quarters. And ironically enough, within five minutes of

each other, both Martin Holliday's man and Mr. Shido's observer

had communicated the fact of the arrival to their utterly alien

employers.

Robert Weston was, of course, aware of neither interest in him. And had the communications been made under his very nose it is not likely that he would have noticed them. He was far too enthralled with this first taste of oriental glamor.

From the moment that his ship had docked and discharged him into the arms of the exotically reeking metropolis, Weston had moved like a man in a daze.

The dockside coolies, the shrieking vendors and beggars, the brown and olive and black-skinned parade of humanity streaming everywhere around him, the chatter of a hundred dialects, a million voices, the parasols and pith helmets, the rickshaws and market spices—all these swam before his excited senses in dizzying panorama.

The hotel, too, from the moment young Weston entered its lobby, was like the setting for some tremendous international drama such as even Hollywood had never staged.

Uniformed Hong Kong Home Guards passed smartly attired British officers. Fashionable and alluring occidental women from every nation on the continent mingled and chatted with sloe-eyed oriental beauties of grace and charm and picturesqueness. Chinese and Japanese, Russians and Germans, Hindus and Mongols, English and American and French and Spanish. There was no race or creed or rank in the vast swarm of the earth's population not represented.

Quite possibly Robert Weston's gaze included Mr. Shido's brown-skinned informer and Martin Holliday's man. Certainly there was little in external visual stimuli that missed his wide-eyed attention. Hong Kong—1941! It left him breathless.

In his room, Weston bathed and changed to fresh whites. And then he sat for a while with the drink he'd had sent up, thinking and marveling and trying to comprehend the vastness of this exciting new world in which he found himself.

There was no one he knew here. That is, no one with whom he could communicate under the orders he had received. But the realization that he would have this week alone only served to heighten his excitement and make him feel even more keenly the rich adventure of the explorations ahead of him.

It would be far better this way, he decided. He would have the thrill that comes only in being completely on your own, unguided and unchaperoned in an exciting and alien world. Of course Weston had better than a standard guidebook knowledge of the city. His specialized training at college had included an intensive study, from maps and charts, of the geographical nature of every large city on the face of the earth.

But the geography and the descriptions in the text books had failed utterly to catch any of the incredibly exotic allure of the East. And just in these first few hours in Hong Kong, Weston was clearly able to see why mere words would never have sufficiently described the place.

After a bit, when Weston had finished his drink and his resavoring of his first taste of the orient, he began to think about suitable amusement for the evening.

In his mind he could count off the names of innumerable restaurants and cafes of which he had heard or been advised to try. But all of them, somehow, seemed to lack precisely the ingredients for what he wanted from his first night in Hong Kong.

He decided at last to let chance take his footsteps where it would. In that there would be more sport, and besides, some inner loathing made Weston rebel against acting strictly the guidebook tourist. He would not follow the beaten path; he would find, "discover" a place of his own...

TALU had chosen her wardrobe for that evening with care. With

a picture of the young American in mind, she had been exacting in

the gown she chose. And when finally she had dressed she was an

exquisite ivory goddess, swathed in ermine-soft, white satin.

She waited then, until she received word of the young man's choice for a dining place. And then, smiling a little to herself at his callow brashness in selection, she rode by rickshaw to the place. It was rather a small, sidestreet cafe; none too respectable, almost within the shadow of the law.

Talu saw him almost immediately on entering. He was seated at a side table, reflectively sipping a tall drink, obviously waiting for his food and swallowing atmosphere in great wide-eyed gulps.

A waiter appeared, seemingly surprised at the sight of one so lovely as Talu gracing this nefarious establishment. She told him that she wished a booth, secluded, meanwhile observing the young American from the corner of her eye and making certain that he heard her request.

The waiter, after a single preliminary raising of eyebrows, bowed and smiled and turned to lead her toward the booths, which were just beyond the young American's table, curtained off by closely hung strings of gaily colored beads.

Talu was consummately unknowing when her fan slipped from the folds of her wrap and fell a few feet from the young American's table as she passed. She hesitated not an instant as she moved on behind the waiter, and even as she turned into the booth she heard the quick scraping of the young American's chair as he rose from the table to retrieve the fan. Talu was extremely experienced in these affairs.

She smiled to herself, then, giving the order for the drink she wanted to the waiter and telling him that she would order food after a few moments.

The waiter had scarcely left Talu's curtained booth, before the young American swept in past the beaded hangings holding her fan in his hands.

The expression on his face was one of slight embarrassment mingled with pure delight. And Talu knew from the moment she smiled up into those guileless, clean blue eyes that she would have little trouble with this one.

"Your fan," Robert Weston said, almost stammering. He colored, nevertheless unable to tear his eyes from her beauty. "I mean, pardon me, but you dropped this fan. It fell from your wrap." He paused, searching for words, and was unable to find them. For substitute, he grinned disarmingly and extended the fan in his hand.

Talu held his eyes with her own, yet made no effort to reach for the fan. It seemed to Weston that a section of eternity slipped by as he was held half hypnotized by that glance.

And then she smiled, a smile that was like nothing Weston had ever experienced before.

"Thank you," Talu said simply. "It was very kind of you to bring it to me." She reached for the fan.

Weston handed it to her.

"It is an extremely lovely thing," he said. "I couldn't help but notice it as I picked it up."

Talu flicked it open with a gesture of her graceful hand. She held it out to Weston.

"You may inspect it more thoroughly if you like," she told him. "There are many curious designs in its folds. It is quite old."

WESTON found it hard to keep his gaze on the exquisite

oriental curio. He found himself wanting to repeat that long

moment in which he had looked into the lovely creature's eyes.

But he forced his attention to the many quaint designs on the

fan.

"The characters and symbols here seem to represent many emotions," Weston said at last. "They are all beautifully drawn."

"The fan was my mother's," Talu said truthfully enough. "She was Chinese. When she died—in Russia, some years ago—she left it to me. It has a curious history, and there is an ancient Chinese legend concerning it."

Then suddenly Talu seemed to be aware of the circumstances of Weston's presence for the first time since his entrance. At least the expression she donned for his benefit suggested her realization that a breach of formalities had been made.

She smiled politely, dismissingly, and reached for the fan.

"Thank you again," she said.

Weston colored, reacting as the girl had known he would.

"I—I'm Robert Weston," he blurted. "I'm an American. This is my first time, in fact my first night, in Hong Kong. I hope you wouldn't think me too rude if I asked if I might, might stay—to hear the legend of that fan," he concluded lamely.

Talu feigned surprise. Her eyebrows lifted, and then her expression softened. She smiled once more, holding his eyes again with her own glance.

"I think perhaps that once formalities are broken unconsciously they are broken lastingly. Yes, you may join me." She paused. "Perhaps you had better tell the waiter to send your food in here when it arrives. Sit down, my young American."

Robert Weston had regained some of his composure with the invitation, and he managed to seat himself across the table from the exotically beautiful Eurasian girl without any of the awkwardness that had marked his entrance.

"Hong Kong is a thrilling place," he murmured half audibly.

"What did you say?" Talu asked.

The waiter entered then, and with true oriental composure had Weston's drink in his hand. He had brought it in from the table which the young man had occupied.

Weston broke into a grin.

"Well I'll be—," he began. Then he laughed. "How did he know I'd be here for the rest of the meal?"

Talu joined in his laughter.

"The oriental mind," she said, "is sometimes many jumps ahead of circumstances themselves." But while Weston bent his head in a search of his pocket for cigarettes, the glance Talu gave the imperturbably smiling waiter was venomous. The glance he returned was the consummately all-knowing glance of the East ...

CONSIDERABLY later, Robert Weston and Talu left the cafe

together. They were laughing gaily, as people laugh who have the

mixed excitement of too much wine and mutual attraction.

And standing there outside the cafe, looking for rickshaws, Weston, feeling courage from the warmth of what he drank, slipped his arm gently around Talu's slim waist.

She turned her face up toward his, then, no protest on her lips, a question in her eyes.

"Hong Kong at night is even more beautiful than I had ever imagined," Weston declared. His voice was husky, and he knew that the alcohol he'd consumed, though great enough, was not completely responsible for the quickened tempo of his pulse and the trembling of his knees.

"There is a place," Talu said softly, "in the hills, from which you can see the island spread beneath you like twinkling jewels of a necklace. You shall have to see Hong Kong from there some night."

Weston nodded. "I certainly shall. And would you be my guide?" He looked down into her eyes and again felt the quickened, breathless hammering of his pulses.

Talu smiled softly. She nodded her golden head ever so slightly.

"If you would like me to," she promised.

Weston suddenly bent to kiss her red, moist, inviting lips. But before he was conscious of the gesture, she laughed coquettishly and brought her fan up to her face.

"You Americans are very impulsive," she murmured, her eyes smiling.

Weston blushed and felt suddenly like a schoolboy.

"I—I am sorry," he stammered. Quickly, he withdrew his arm from her slim waist.

Talu's eyes were still smiling. She lowered the fan slightly.

"And you are also very strange. You apologize for your wishes." Her hand found his, soft and fragile and cool in his big palm. She squeezed his hand ever so slightly.

"Now I am afraid you must take me home," she said.

Weston looked woebegone. "But the evening is young!" he protested. "This is my first night in Hong Kong—"

"But not your last," she cut in. Her voice was a promise.

"Then I may see you again?" he asked eagerly.

Talu nodded. "I see no harm."

"Tomorrow," Weston said swiftly. "Tomorrow for breakfast in the Hong Kong Hotel."

Talu laughed at him; laughter like tinkling bells. She shook her head.

"Not tomorrow morning," she said.

"Tomorrow afternoon?" Weston demanded.

Talu shook her head again. "I have an appointment," she declared.

"Then surely tomorrow evening for dinner," Weston pleaded. "We can meet early and cross to Kowloon. We can dine at the Peninsula Hotel there."

Talu seemed to debate a moment. Then her laughter tinkled again.

"Very well," she promised. "Perhaps there is something in the impulsive technique. Americans must believe in persistence."

Again Weston found himself fighting to resist the temptation of her lovely lips. The fan caught his eyes and suddenly he smiled.

"I never did hear the legend of your fan, Talu," he said. "Remember? You were going to tell me."

The girl seemed suddenly serious again.

"I had forgotten," she said somberly. "It is a curious legend. This fan once belonged to a courtesan in the court of a great mandarin. She was a famous woman of her day—long, long ago, of course. Her name," the girl paused an instant, "her name was, strangely enough, the same as mine, Talu. I believe my mother named me after that original possessor of the fan."

"And this, this other Talu was beautiful?" Weston asked, looking gently at the girl beside him.

Talu nodded. "She was sung by the poets of the dynasty. Her beauty beggared the poor verses that were written about her. The mandarin was madly in love with her. But he was old, and evil, and she cared nothing for the jewels and attention he lavished on her."

Talu paused, looking up at Weston peculiarly. "Do you wish me to continue?"

Weston nodded eagerly. "Yes. Please do."

Talu seemed to reflect. Then she went on.

"The courtesan was in love with a young artist. Even in those days in China, artists were impoverished wanderers of no consequence in the political scheme of things. This Talu, however, cared nothing for the fact that her young artist was not measured in the worldly attainments of those about her. Secretly, she arranged to have her lover brought to the mandarin's court, and saw to it that he received subsidy from the dynasty." Talu paused.

"Please go on," Weston begged.

"For many moons," Talu continued, "the courtesan and her artist were able to live this way, having one another's love and companionship even in the shadow of the evil mandarin's throne. But the young man found this more and more to his dislike, and again and again tried to persuade this Talu to flee the court with him. He vowed that they could find peace and lasting happiness together far from the evil influence of the mandarin. But the girl was afraid. She knew that the wrath and vengeance of her evil sponsor would follow them no matter where they tried to flee. The young artist persisted in his pleas, however, and finally, against her better judgment, she agreed on a plan with him whereby they would escape together. The fan, this fan, was to serve as their means of signal when the hour for their scheme arrived."

Weston was puzzled. "The fan? How was it a signal?"

Talu smiled. "It was the custom of the court artists to paint the fans of the courtesans and great lords. They vied with each other, these court artists, to create the most beautiful symbols on the fans they painted. Talu's artist lover had painted most of her fans for her, and on each of them had depicted scenes known only to the two of them in their symbolism. On this fan it was agreed that the young artist would inscribe certain symbols and use prearranged colors if the time were ripe for their escape. If not, he would indicate as much by the lack of the agreed colors and symbols on the fan."

"Very clever," Weston marveled.

Talu nodded. "Yes. It was extremely clever, except for one thing. The evil mandarin had learned of his courtesan's love for the young artist. He suspected that they would try to flee his court. And he had learned that they would communicate through means of this fan and its inscriptions."

"Ah, so it wasn't a happy ending?" Weston asked.

Talu shook her head, a sad little smile at the corners of her lovely mouth.

"No," she sighed. "It was not a happy ending. The mandarin arranged to intercept the fan. He read on it the symbols the young artist had inscribed, ordered the courtesan brought to him and demanded of her the truth."

"Did she admit to it?" Weston asked.

Talu shook her head. "No. She wanted only to save her lover's life. After showing her the fan, a masterpiece of art and color, tinted an exquisite gold, he tried to force her to admit her plan. She refused, hoping that the young artist would have time to flee the court alone and seek safety in the hills. She didn't know that the mandarin had already ordered her young lover seized and was holding him for execution at that moment. This Talu was tortured, but still would not admit to the identity of her lover. The mandarin kept her fan before her eyes, taunting her with it, until at last he wearied of his sadism and ordered the young artist slain."

Weston shuddered. "How horrible."

Talu nodded. "And the moment that the young artist died, the courtesan knew instantly of it. She knew from the fan itself."

"From the fan itself?" Weston frowned.

"It's gorgeous colorings and golden tint changed, miraculously, before the courtesan's eyes. The colorings faded to a dried brown, and the tint became a sheen of black—the color of death. The courtesan wanted life no longer, then, and died before she could be tortured any more."

Weston was silent for fully a minute. At last he said: "And this is the same fan?"

Talu extended the fan to him, nodding her head. "Yes. See the dried brown hues, and the sheen of black. It is the same fan."

Weston shook his head, rubbing his hand across his eyes. "A very tragic legend," he remarked.

"Many of the legends of China are tragic," Talu said.

Weston suddenly smiled. "But they are no more than legends," he declared.

Talu, too, smiled. "Yes. They are no more than legends. But I sometimes wonder about this fan and the original Talu. My mother would never tell me more."

"Perhaps," Weston said, "like all legends there was a happy ending to it in the hereafter."

"Perhaps," Talu said. Then she smiled at him. "But it is time that I am taken home."

"Of course," Weston said. "I don't mind taking you home now that I know there will be tomorrow."

Talu's almond eyes regarded him curiously. "In the East there is always tomorrow," she said....

TALU had not lied to Robert Weston about her appointment the

following afternoon. She quite definitely had one—with Mr.

Shido. His quick tattoo knock sounded on her apartment door

precisely at the minute on which he had said he would arrive.

He stood there in the door, dressed in his precise, faultless whites, holding his panama hat in his small yellow hands. His gold teeth glittered in a grimace which he fondly believed to be a smile.

"Eeekonadee cozeymahcah?" Mr. Shido greeted her.

"Come in," Talu said a trifle distastefully. Mr. Shido's habit of foisting his native language on her was annoying. It implied a union which Talu resented.

"You have met the young American and arranged for future meetings?" Mr. Shido asked, taking a place on the divan and putting his hat carefully on a teakwood table beside it.

Talu lighted a cigarette, still standing, and nodded.

"Everything went off as scheduled," she said. "You really haven't any cause for worry. He's a lamb waiting for the shearing."

Mr. Shido regarded her humorlessly. "Worry is essential in a scheme as important as this. Never make the mistake of underestimating your quarry, Talu. The British and Americans at this moment make the mistake of underestimating my government."

Talu turned her back on him, paced to the end of the room, and wheeled to face him again.

"I am meeting him tonight," she said. "We are going across to the Kowloon side, to dine at the Peninsula Hotel."

"Excellent," said Mr. Shido, showing his pleasure by sucking his breath through his gold teeth.

"Have you anything else you want to tell me?" Talu asked.

Mr. Shido raised his eyebrows in surprise. "You are most abrupt," he said. "I sense something almost bordering on hostility in your attitude, Talu." He hissed in reverse and gave another one of his imitations of a smile. "I had thought that we might talk a while."

"Our relationship goes only as far as matters such as that of the young American," Talu said tightly. "I spend my social hours as I wish."

"Talu!" Again there was that lifting of eyebrows and surprise. "I had heard that you were an excellent agent in matters such as this. That is why I engaged you. Please show no more impertinence. You would be wise not to draw my disapproval."

"I have worked with other agents of your country," Talu said angrily. "They showed none of the veering from duty which you seem to display. It would be best for you to confine your attention to this immediate problem on which your government has placed you."

Mr. Shido's golden smile vanished. His mouth went tight, and he rose stiffly, clutching at his panama hat with both hands.

"You are not being sensible," he declared. "If you were aware of my power, my importance in my government, perhaps you would be a little more amiable!"

Talu crushed out her cigarette, jamming it into a shell tray viciously with her jade holder.

"I have worked for many governments," she said in evenly controlled rage. "They mean nothing to me, any of them. The money they pay me is all that matters. In my work with their agents I have considered only one element—the job at hand. I hope that clears the situation for you, my friend Shido!"

Mr. Shido moved to the door. The expression on his mouth was again that imitation golden smile. But the smile never left his teeth. It stopped there. The expression in his slanted eyes was that of an angry brush snake.

"I will be back tomorrow, to check further on your progress, Talu," he declared. "You will please forget this unpleasant conversation. We will go on as if it had never occurred. Nothing must interfere to disrupt our plans. Nothing. Sayroonerah."

AFTER Mr. Shido had gone Talu paced nervously, angrily back

and forth across the room. She lighted several cigarettes in the

course of the next twenty minutes, crushing them out, however,

after a few short draughts.

At last she was able to regain control of herself, and then she smiled. She had been stupid to become so annoyed at the golden toothed little fool. She could have warded off his unwelcome ideas much more smoothly than she did. Such unpleasantness in her work had occurred before, and always her infinite experience had enabled her to sidestep such advances with nimble dexterity. She wondered what had made Shido's unspoken ideas so particularly annoying, and found herself puzzled for an answer.

"Perhaps it is because he is Japanese," she reasoned aloud. "They have become so increasingly smug, those yellow monkeys, these past few months. Their bluff and shouting has been heeded too seriously. It has gone to their heads. They grow arrogant, and much too bold."

And then, for no reason she could explain to herself, Talu thought of young Robert Weston. She remembered his hearty, honest laughter and scrubbed, friendly face.

"He is a child," she murmured, "and yet a man. Naive—that is the word which best describes him."

She strode to the teakwood table and picked up her fan, flicking it open a moment to gaze at it.

"An oriental legend," she smiled. "I really think the young fool believed my hastily improvised tale."

Closing the fan, Talu stood with it in her hands, looking almost absently at it. Her mind was still concerned with young Weston...

IN his hotel room late that afternoon, young Weston stood

before a long mirror adjusting a black cummerbund around his

waist. He was clad in fresh white drill and had already gone

through this entire process of grooming at least four times. And

as he went through the ritual again, Weston sang softly to

himself the words of the ballad that had been running through his

mind ever since his arrival in Hong Kong.

"Take me somewhere east of Suez—wheeerrre the best is

like the worrrrrest.

Where there ain't no ten commandments and a man can raise a

thirrrrest!"

And for the tenth time in an hour, Weston glanced quickly at his watch. He sighed. Not quite time. Talu would not be waiting for him for another fifteen minutes.

He concluded his grooming with a stately mock bow at his mirrored reflection. Then he went to his dresser where there was a tall, cool drink waiting half finished.

Weston found a chair, then, and with his drink in one hand expertly lighted a cigarette using only the other. He leaned back, savoring the smoke, the drink, and his thoughts. The latter were, of course, chiefly concerned with the glorious, glamorous Talu.

Again and again, Weston relived the moment of their meeting. And on each occasion he could again hear the sound of her soft, liquid voice, musically tinged with the faintest of strange accents.

He wondered, of course, who she was, and what she was. He had dared not ask on taking her to her apartment the night before. But the very lack of knowledge concerning the beautiful Eurasian gave additionally glamorous mystery to her.

Talu—her name was exquisitely in keeping with her loveliness.

Weston smiled, lifting his glass and thinking of the week of adventure that lay ahead of him.

"Here's to the boys in the Hong Kong consular office!" he toasted. "May they be responsible for my meeting more and more creatures as lovely as Talu!"

THE boys in the consular office, however, could scarcely have

been expected to answer to young Weston's toast. They were far

too frantically busy with other matters.

Martin Holliday, official of the staff who had been responsible for Weston's arrival, took time from his duties only to check on the fact that his observer, waiting in the lobby of the hotel where the young diplomacy cub was staying, reported the youth as returning from a tour of the island at approximately eleven thirty that previous evening. Young Weston had seemed acclimated and in good spirits, the observer went on to state.

"That's one less anxious day," Holliday commented to a trusted aide. "Now if the youngster can only go along with his sightseeing and keep out of trouble for another five days, we'll be all right."

"Wouldn't it be wise to make certain he stays out of trouble by having a man on his tail constantly?" the aide suggested.

Martin Holliday, nerves worn raw from his days and nights of tension and never ending work, snapped his answer irritably at his aide.

"I've explained that before! We don't dare put a man on Weston to follow him. All our men are known, possibly followed themselves by hostile agents. It would give Weston away immediately!"

The aide gave Holliday a grieved glance and left the office. Quite possibly he would have forgiven his superior's irritation had he realized—as no one did—that Jap bombs were scheduled to fall on Hong Kong within a week...

YOUNG Weston and Talu dined at the Peninsula Hotel in Kowloon,

directly across from the island of Hong Kong proper. And after

they had eaten there was champagne and dancing, moonlight such as

only the East can furnish, all against the romantic background of

tropically flowered gardens.

Later, they crossed Victoria Bay back to the island and drove to the peak of one of the smaller hills. There they sat silently, looking down at the glittering lights of the island beneath them. The first hilarity and gaiety of the evening had left, to be replaced by something akin to an unspoken communion of silence. This, at least, was what young Weston imagined it to be.

Talu, of course, was playing her hand with admirable finesse. She knew well that the young American could best be kept fascinated by constant and subtle variances of mood.

And still later, as he took Talu homeward, Weston asked the girl to tell the legend of the fan to him once more. In the darkness Talu smiled; but she managed to remember her fabrication of the previous evening. In the telling of the tale this time, however, she elaborated somewhat on the general line of the "legend," adding small new details which only seemed further to please the young American.

"But why are you so interested in the fan and its legend?" Talu asked Weston when they arrived at her door.

The young American's expression was serious, his answer what might have been expected of him.

"Why," he stammered, "if it hadn't been for your fan, Talu, we might never have met." He blushed then, and in confusion added: "It's always been an idea of mine that life is concocted of such little things. I—I mean, sometimes the most important events are caused by trifles."

Talu looked at his clean, honest eyes, and the smile on her lips trembled slightly. For an instant—and only that long—she wished that somehow their meeting had been truly caused by the fan, and that she were someone other than—But she drove this thought from her mind as swiftly as it had entered.

"Good-night, my young American," she said. "It has been lovely." She turned to enter her apartment.

Weston was conscious only of his impulse. He didn't remember moving swiftly beside her, dropping his hand lightly on her arm so that she turned. He only knew that somehow he had found courage to sweep Talu into his arms, and that her lovely red lips were pressed against his own.

When he stepped back, releasing her, Weston was breathing heavily, and his senses reeled. The fragrance of jasmine from her golden hair was sheer intoxication.

And for once even Talu was surprised.

She touched her hand to her lips, her eyes wide, a curious expression in them.

"Impulsive young American," she whispered softly, "I—I am at a loss for something to say."

Weston swallowed, a dull flush coming to his scrubbed young cheeks. The smile he ventured was uncertain, boyishly awkward.

"I will see you tomorrow?" he begged.

Talu nodded wordlessly. Then she turned away and was gone...

THEY lunched the following afternoon on the other side of the

island, at the lavish Repulse Bay Hotel. Talu wore an afternoon

dress of white chiffon, and Weston found himself marveling at the

varied and infinite changes, in the girl. The first night he'd

met her she was the langorous, exotic siren of the east. The next

meeting had made him feel as if she were the smart, sophisticated

sort of young woman he'd squired so often in Manhattan. But this

day found her displaying the ingenuous charm and fresh allure of

a college girl.

"You laugh so much more today," Weston observed as they sipped martinis. "You seem gayer, happier—almost like a small girl at a circus."

Talu smiled at this.

"Perhaps laughter is an infectious thing. Perhaps youth is the same. Perhaps it is you who makes me feel as I do today," she said.

Weston shook his head. "Today I feel a hundred years older than you—and so much more wise. Really, Talu, I wish there were some foam candy to buy for you, and a ferris wheel to take you on." And then he laughed, coloring a little in embarrassment. "Although I must confess that for several glorious moments last night I felt as if you had taken me to the very peak of some glittering ferris wheel."

Talu's laughter tinkled again like tiny bells.

"You caught me totally by surprise," she said.

Weston smiled, but his eyes were suddenly serious. "And was it a terribly unwelcome surprise?" he asked.

"I am still trying to decide," Talu countered lightly.

"Perhaps the sample has evaporated by now," Weston said. "You might need another to refresh your memory and give you a better chance to make your decision."

Talu's lips were half parted in answer when her expression suddenly froze in something akin to sudden fright or annoyance. She seemed to be gazing intently past Weston's shoulder.

"What's wrong?" Weston demanded instantly. He half turned in his chair, trying to discover what had taken the girl's attention.

Talu put her hand swiftly on his.

"Nothing," she said rapidly. "Nothing at all. I thought for a moment that I'd seen a person I used to know. Someone I disliked intensely."

Weston was still turned slightly in his chair. There were only four or five other tables behind them in the section of the veranda where they were seated. But two of these tables were occupied. One by a party of middle-aged women, another by a solitary, dapper, white suited little Japanese.

None of the women were paying the slightest attention to them, and Weston had the impression somehow that the little Jap had been gazing intently at them and had just turned his eyes away as Weston had swiveled about to see what was up.

Weston turned back to Talu.

"Who was it that you thought you knew?" he demanded.

Talu shook her head. "She's gone, now. A woman. She passed up the walk behind those women at that table."

Weston smiled. "Evidently people whom you dislike, you dislike with utter thoroughness. You look positively pale, Talu."

Talu managed to smile.

"I don't think it was she—the woman I saw," she said, "But for a moment it gave me a terrible start. I—I'll tell you about her some time."

WESTON didn't press her further, and as their luncheon was

served Talu seemed to regain most of her composure, though her

laughter was less frequent and something in the mood they had

reached seemed to have been destroyed. It was after their

luncheon was over and they had ordered cocktails that the little

Jap in the white suit and spotless panama passed their table and

strolled leisurely into the hotel lobby. He didn't give them the

briefest glance, but if the idea hadn't been so utterly idiotic,

Weston would have sworn that Talu seemed to relax only after he

was gone.

Talu's gaiety returned then, though Weston was far too intent in the loveliness of her beauty to notice that there was a sharp, almost forced, edge to it now. And when he at last returned her to her apartment he had no idea enroute of what was to occur as they parted.

A rickshaw waited in the street, and Weston stood holding both Talu's hands in his own.

"I don't believe I've ever had such an afternoon," Weston said. "We can't spoil it now by waiting until tomorrow for another meeting. What about dinner again tonight across Victoria Bay in the Peninsula Hotel?"

Talu's lovely mouth smiled, but there was something close to pain in her eyes.

She shook her head, the smile on her lips trembling ever so slightly.

"No, Robert," she said softly. "I have an engagement tonight. I am very sorry, of course. You must remember that all of this—our meeting as we did—was most unexpected. I had had plans before that. I changed some of them; I could not change them all."

Weston's disappointment was but partly hidden behind his grin and light reply.

"That's right," he admitted. "Yet I feel as if I'm the only one who has a right to know you, to sit with you, to laugh with you. You will have to forgive that possessive streak. I'm afraid it's also very much American."

"I will forgive it, Robert," Talu said quietly, unsmiling.

"But there is tomorrow," Weston said. "I can have tomorrow to look forward to, can't I?"

Talu hesitated an instant. Her voice was almost muffled when at last she answered.

"I'm afraid I have another engagement for tomorrow, Robert."

"Not the entire day?" Weston protested.

Talu nodded slowly.

"But—" Weston began.

Talu touched his arm with her fingers. "Why don't you call me here at the apartment?" she asked.

Weston seemed uncomprehending. "Yes," he mumbled. "Yes, I certainly will call. But I thought that—"

Again Talu cut him off. "I must hurry, Robert. This has been a day I shall long remember. Do you wish to, to refresh the sample—as you called it—from last night?"

Weston grinned suddenly.

"The conversation strikes a happy note," he said lightly. "Yes. I would most certainly like to refresh that sample of last night. For myself, as well as for you."

But his hands, as he put them on the girl's slim shoulders, were unsteady, and no amount of effort at casual levity could stem the sudden wave of weak excitement that flooded his veins.

Weston was looking down into Talu's upturned lovely face one moment, his hands lightly on her shoulders. And in the next, his arms were tightly around the girl and his lips were hard against the ripe softness of her mouth as her body unresistingly drew close to his.

THEN they had both stepped back, and Talu was looking up at

him.

"Call me, Robert," she said faintly. "Goodbye, and thanks for—for everything."

She turned away, and Weston watched her leave. It wasn't until minutes had passed that he realized the rickshaw still waited in the street behind him.

He turned quickly, then, almost stepping on the small fan that lay at his feet. He stepped back, bent, and picked it up. It was Talu's fan, undoubtedly. In her haste in leaving she had dropped it.

Weston held it in his hand, staring at it. For a moment he thought of following her, returning it to her at once. He flicked it half open, gazing at the faded brown hues of the characters beneath the black sheen that covered it.

Then, as if on sudden resolve, he snapped it shut and put it in his pocket. He would return it to her the following day, he decided. It provided a perfect excuse for seeing her again tomorrow ...

When Talu let herself into her apartment, she was still unconscious of the fact that she no longer carried her fan. And the discovery of its loss was forestalled for the moment due to the shock she received on seeing the slant-eyed Mr. Shido sitting there waiting for her.

She had just closed the door behind her and was removing her hat when she saw him. He hadn't spoken, and even now was staring wordlessly at her.

Talu's hand went to her mouth to stifle her involuntary cry of alarm. And then her momentary fright vanished to give way to anger.

"How did you get in here?" she snapped. "What do you want?"

Mr. Shido smiled his golden smile.

"I took the liberty of using a key which works most admirably on the sort of lock you have on your door. I expected you would return here before rejoining the young American fool for the evening."

"You take numerous liberties," Talu said angrily. "I like none of them. Please state your business and get out."

Mr. Shido's golden smile remained mechanically fixed. In his slant eyes there was anger.

"You are forgetting yourself, Talu," he declared. "And I have reason to believe that you might almost be guilty of forgetting your task with that young American ass."

"What do you mean by that?" Talu demanded.

"When I lunched at the Repulse Bay Hotel this afternoon it was not by chance. I went there when I learned that was where you and our young fool would be."

"Then you were spying on me!" Talu said, white with anger.

Mr. Shido nodded.

"You might call it that," he said. "However, I found it extremely interesting, and somewhat worrying. Your enthusiasm for the young American seemed completely genuine. I suspected you had to do little acting to appear so completely enthralled by his presence."

TALU'S anger changed to an emotion akin to sudden fear. She

tried to hide this from his eyes, striding swiftly to a table

where she took a cigarette and holder from a box.

"That is ridiculous!" she snapped.

Mr. Shido raised his eyebrows. "Is it?" he inquired.

"Of course," Talu said. She lighted her cigarette with fingers that trembled ever so slightly.

"You are seeing him again tonight?" Mr. Shido asked casually.

Talu took a deep draught from her cigarette. She turned to face Mr. Shido.

"No," she said. "I am not seeing him tonight."

Mr. Shido did not seem surprised. "And why not?" he asked.

"I have something else to do," Talu said quickly.

"What?" Mr. Shido's question snapped like a whip, and the golden smile left his face.

"Something that is of no concern of yours," Talu said.

"And you are going to let the young American fool wander loose from your influence?" the Jap demanded.

Talu shook her head. "I thought it wise that I let him pine tonight. He is to call tomorrow. I can handle these things very capably without interference."

"There has been a necessity to alter plans somewhat," Mr. Shido said. "I came here to tell you that. We will have to work more quickly than I first imagined. Through a leak in their diplomatic office, I learned that the Americans have decided to use young Weston sooner than they intended. Tomorrow night the stupid young American will be given certain papers to take to a British official on the outskirts of Kowloon. They contain information as to plans for evacuation of the more important officials in Hong Kong, should such action became necessary. We will get those papers from young Weston—through you."

"Evacuation?" Talu was unable to keep the startled surprise from her voice.

Mr. Shido smiled. "Certain measures will be taken soon by my government which might make evacuation of all whites from Asia extremely necessary."

Talu stared at the little Mr. Shido as if he had gone suddenly insane.

"I see you are surprised," Mr. Shido said. His golden smile widened. "Many others will be surprised, also."

"But the Japs don't intend—" Talu began.

Mr. Shido broke in. "Japan is becoming increasingly irritated by the stupidity of American and British attitudes toward her. Unless many drastic reversals in their policies are made, or agreed upon, within the next several days, she will show her claws to those white-faced devils."

TALU seemed suddenly relieved.

Mr. Shido was but repeating the time-worn Nipponese bluff and boast. His talk was nothing more than talk. Actually, Talu felt sure again, the Japs would not dare to show their hand. But what of this talk about evacuation plans?

"Are you certain of what young Weston will be carrying?" Talu demanded.

Mr. Shido looked all-knowing. "I see that you cannot appreciate the present terror of the Americans and British. You cannot comprehend that they would think in terms of evacuation. They are even trying to conceal their close collaboration with one another here in Hong Kong. Hence the secrecy with which young Weston's task has been cloaked."

"And is it tomorrow night when young Weston will be given the papers?" Talu demanded.

Mr. Shido nodded. "Precisely. The seventh day of December,* one night from tonight." His additional elaboration was obviously meant for sarcastic emphasis, for he added: "Just to make certain you do not slip up on your part in our plan."

[* 7th of December, in Hong Kong, due to international date line, is equivalent to 6th of December in U.S.A. —Ed.]

Talu crushed out her cigarette. "I see. When he calls tomorrow I shall arrange to have him here tomorrow evening."

"You will arrange to have him spend the better part of the entire day with you, Talu," Shido corrected. "We must not risk his discharging his mission sometime during the day—even though it is now planned for the evening."

Talu nodded. "Very well, then."

Mr. Shido rose. "Please do not let any feeling for the stupid youth betray your mission at the last minute. It would be decidedly unwise for you to do so. Then both of you would die."

"Both of us?" Talu's shock was too strong to conceal. "You mean that you plan to kill this boy?"

Mr. Shido smiled. "Naturally," he said. "We must complete our task thoroughly. You have led others to their deaths; surely you have no qualms about this youth."

"But—but is it necessary?" Talu asked whitely. "Merely to get his papers?"

"I have planned it as necessary," Mr. Shido declared. "He might be stupid enough to resist. It is better to kill him before he suspects anything. It will, ah, facilitate matters greatly."

Mr. Shido moved to the door, displaying his golden smile again.

"I shall warn you again to comply with every detail as I have arranged it. Do not get any ideas at this late hour. You would regret it." Then he was gone. ...

WHEN Weston returned to his hotel he found the envelope lying

casually on his dresser. It was addressed to him, and when he

opened it puzzledly, he found it contained a single sheet of

white paper on which was typewritten a curious message.

Man from consular office will meet you tomorrow in your room. He will give you portfolio and instructions as to where to deliver it. He will be there promptly at six p.m. Destroy this message. Holliday.

Weston reread the message several times, frowning. Then he

crumpled it lengthwise, carried it over to a wastebasket and

touched a match to it. He held it as it burned, dropping it in

the basket only after the part on which the message had been

written was destroyed.

As he prepared to change for dinner he wondered at great length as to what the message meant. Holliday hadn't wanted him to report at the consular offices until a week had passed. And now this message.

Weston realized that the instructions to destroy the note were, in times and under situations such as this, standardly routine. He was not, therefore, disturbed by that part of it. But as to the papers that would be given him, and the delivery that would be necessary, Weston was distinctly bewildered. What could it be about? Weston couldn't bring himself to believe that the mission which was being assigned to him was one of any great importance. He knew that he was too inexperienced, too untried, as yet, to be of any value on important matters.

Perhaps this, then, was just a baptism. Sort of—and he grinned ruefully at the thought—breaking him into his work as an unofficial messenger boy. Weston shrugged and gave it up. It was only too easy to turn his thoughts back to Talu, for he was still in the throes of bitter disappointment over not being able to see her this evening.

"Of course she'd have other things to do besides spend all her waking hours in my company," Weston admitted to himself. "I could have expected this. But—" and he frowned, recalling Talu's inflections, expressions, as they had parted. It began to be clear to him that she had seemed somewhat different, almost troubled, in their parting.

"Why dammit!" Weston exploded, shocked at the thought. "She acted quite as if she never expected to see me again!"

Instinctively, Weston started for the telephone. Then he stopped, taking his hand back from the instrument. No. He was acting ridiculous. She had said to call her tomorrow. And if she hadn't expected to see him or hear from him again she wouldn't have told him that.

But Weston was unable to put the matter completely from his mind. And its weight settled over him like a heavy shroud. He felt suddenly blue, very lonesome, and inexplicably uneasy.

"Tonight," Weston promised himself, "I shall find a bar and get stinking drunk." He sighed and ran a hand through his hair.

"Talu, Talu," he muttered, "I'm afraid you have me quite on the ropes, my girl."

Weston lifted the telephone from the cradle and called for a drink...

ON the morning of the following day young Weston woke with a

shattering headache and innumerable regrets. He could recall

fuzzily a drinking bout that began in a waterfront saloon with

several sailors from British merchant ships. He remembered the

exhilaration of the first drinks, the singing and the shouting,

and several hilarious passages from one bar to another via

rickshaw. His memory of returning to the hotel was almost

completely a blot.

And then he remembered that he was to call Talu.

Weston rose from his bed and made his way unsteadily to the shower. He stood for perhaps ten minutes under a steaming spray, feeling some of the life returning to his numbed body from the hot spray along the nerves of his neck and shoulders. Then he turned the shower on cold and suffered for five minutes under a frigid, stinging lash. When he emerged from the shower toweling himself briskly, he felt considerably better.

He was able to call Talu, then.

The operator had at last been forced to remind him that there was no answer, and that if he would ring off they would try the number for him again after a little while.

Glumly, Weston put the telephone back and went about dressing.

The clock on the dresser told him it was a little after ten, and he found himself wondering where the girl could be at this hour of the morning. She had told him to call, and this seemed to be a reasonable hour at which to expect a call from him—so where was she?

When Weston had dressed, impatiently he tried again to call her. There was still no answer, and again the operator promised to try the number a little later.

Weston had his breakfast sent up to his room, deciding that Talu might possibly try to call him, should she be out somewhere. He didn't want to run the risk of missing her, should she do so.

But Weston received no incoming calls.

It was after eleven when he finally crushed out his fourth after-breakfast cigarette and walked to the telephone again. But as before, he was still unable to reach Talu.

Cursing, Weston slipped into his coat and started toward the door. It was then that Talu's fan, lying atop the dresser where he had left it the night before, caught his eye.

He turned back to get it, deciding to take it with him, and was suddenly aware of the incredible transformation in its coloring.

For a moment, as Weston stared at it, he felt certain that it was some other fan, that it couldn't possibly be the same that Talu had dropped.

But the characters, the size and shape of it, everything save the coloring, seemed identical to Talu's fan. And the tinting, instead of being the dried-brown, black-sheened color that it had been, was now an incredibly gorgeous combination of rose, saffron, and rich amber—all sheened by a glossy covering tint of beautiful gold!

Weston stood there, turning the fan in his hands, jaws agape, too stunned by this incredible transformation to fully comprehend it.

"Good God," he muttered hoarsely. "Good God—this is impossible!"

It occurred to Weston then that this might well be a curio he picked up during his drunken spree the evening before. Perhaps he had stumbled into some small shop, attracted by this fan's similarity to the one Talu owned.

Swiftly, Weston began a search for another fan. Five minutes passed and he had rummaged through all his possessions. He hadn't found another one.

Weston knew he hadn't taken Talu's fan with him when he'd left the hotel the night before. So it should still be here in his room. And there was no fan but this gorgeously colored, golden tinted masterpiece.

That left him with but one conclusion. This was the same fan that Talu had had. There could be no other. His first supposition, impossible as it was, was nonetheless correct. Talu's fan had changed, had come alive with color!

AND then Weston recalled the legend of the fan, the strange

little tale Talu had told him of its history.

"I'm out of my mind," he muttered. "It's too fantastically impossible. It's just a silly ancient legend."

Weston tried hard to convince himself of this. He tried hard and kept his mind as far afield from the actuality of the transformation as he could.

"It couldn't be," he told himself again and again. "It just couldn't be possible."

Nevertheless, he had the fan in his pocket when he left his room. And in his heart there was a tingling excitement, a sensation of incredibly thrilling unreality. He felt as if something alive had taken possession of that fan. And his impatience to reach Talu was now a frantic urgency. He determined to go directly to her apartment. To wait there until she came back to it. He left a message at the hotel desk that he would call in regularly and to hold any communications for him...

WESTON had never imagined, of course, that Talu was actually

in her apartment all the time that he'd been trying to reach her.

It could never have occurred to him that she'd been listening to

the incessant ringing of her telephone with iron-willed

determination not to answer it.

For Talu was quite certain that young Weston was the one who was so urgently trying to reach her. And she was equally certain that she had seen him for the last time. Sickly certain, perhaps, for Talu was now too well aware that she loved Robert Weston.

She expected, too, as she paced tensely back and forth smoking innumerable cigarettes, that Weston would come directly here to her apartment after his efforts to reach her by telephone had failed.

"But I cannot see him," she told herself again and again. "I dare not, even though I know what that will mean."

Tonight was the night. The night Mr. Shido had planned the death of young Weston and the theft of the papers he carried with him. And if Weston came here to her apartment after receiving those papers, he would be sauntering straight into the arms of eternity.

Talu was afraid, horribly, terribly afraid. Not for herself so much as for Weston. Weston, the clean, scrubbed, honest-eyed young American. Weston, the athletic, eager, naive child who had been such easy prey for the long practiced lures of Talu.

It was not enough that she evade Weston, Talu knew. It was not enough that she failed to see him, failed to arrange a meeting. For Shido would, in a very short while, be aware of her double-dealing. And Mr. Shido, under such circumstances, would be capable of anything.

It was Shido's coming that Talu dreaded.

Through the slatted blinds of her windows, Talu could watch the street. She saw Weston when he first arrived. And she waited through the endless ringing of her apartment bell until at last he left. Hours passed, and Weston returned again and again to try unsuccessfully for admission. It was shortly after five thirty, when Weston left for the tenth time, that Mr. Shido entered the apartment noiselessly.

TALU hadn't even seen the little Jap coming up the street. And

she whirled from the window, gasping her terror, as he entered

her apartment.

Mr. Shido wasn't smiling now. His slant eyes were fired with venomous hate.

"Talu!" he spat the word.

Talu didn't try to answer. She stared in fascination at him; the rabbit hypnotized by the snake. Fear almost suffocated her, her lovely breasts rose and fell swiftly in her fight for breath.

Mr. Shido held an automatic pistol in his hand. It was pointed at Talu.

"You have reacted as I was afraid you would, Talu," Shido said. "You will pay for it. Young Weston will be given the papers at six. I have learned that. You will call his hotel, leaving a message that he come here to your apartment at six-thirty. He will have the papers with him, since he is to deliver them at seven o'clock. They dare not tell the young fool the urgency of his mission for fear he might make a misstep under the strain. He will think nothing of delaying the delivery of his portfolio. Perhaps, by keeping him away today you have increased his urgency to see you and played into my hands."

"I will not call him," Talu said.

Mr. Shido nodded. "You are right. I shall call and leave the message for him. I would not think to trust you to do so."

Talu stared hypnotized at the gun. Mr. Shido read her thoughts.

"Do not be foolish," he advised her. "Your death at this moment would not complicate my plans at all. If you wish to live a little longer, please sit down there—," he waved the gun toward the divan, "and we will wait the coming of young Weston. In the meantime," Shido stepped to the telephone, "I shall call his hotel and leave, ah, your message for him."

Weakly, Talu slumped to the divan. She still stared in horrified fascination at Shido as he began the call...

YOUNG Weston arrived at his hotel scarcely five minutes before

six. And he had hardly removed his coat, once in his room, when a

knock sounded on his door.

The man who stood there when he opened it was Chinese, dressed in quite occidental tweeds. He was small, middle-aged, and unsmiling. He carried a portfolio with him.

"I am from Holliday," he said softly, entering.

Weston stared at him guiltily, realizing that he had almost completely forgotten his assignment.

"Please sit down," Weston said hastily.

The Chinese shook his head. "I have no time," he apologized, handing the portfolio to Weston. "These contain the papers you are to deliver to British officials on the outskirts of Kowloon. The specific instructions are inside this envelope." He pulled forth a manila envelope from his pocket, handing it to Weston with the portfolio.

"It is urgent?" Weston asked. He suddenly felt foolish for his question, but before a flush of embarrassment came to his cheeks, the little Chinese had shrugged.

"They must be delivered within hour or two," he said. "No time for Holliday to get another to carry them."

The little Chinese spoke with almost casual indifference, and Weston found himself feeling pleased over how closely he had called this assignment when he first learned of it. Nothing more or less than a glorified messenger task.

He took the portfolio and the envelope. The Chinese turned toward the door.

"Tell Holliday that I'll be in at the office the day after tomorrow," Weston said. "As he instructed," he added.

The Chinese nodded and left. Weston closed the door, and a moment later his telephone rang. He picked up the instrument from its cradle.

"This is the desk, Mr. Weston," a voice said. "Message left for you while you were out."

Weston's heart suddenly started to pound.

"Read it, please," he asked.

"Unable to see you today. Sorry. See me at my apartment at six-thirty tonight. I will explain. Talu."

"Is that all?" Weston demanded.

"That is all."

Weston hung up. He glanced at the clock on his dresser. A few minutes after six. He'd have time to make it. He could take the papers—he paused to tear open the manila envelope and scan his instructions briefly—to the Kowloon outskirts after seeing Talu. Perhaps she could come with him, and when he was done with his message-carrying they might dine at the Peninsula Hotel.

Weston shrugged into his coat, stuffing the envelope into his inside pocket and shoving the portfolio under his arm. For an instant his hand touched his pocket, and he felt the fan lying there. He brought it forth briefly to marvel again at the incredible color transformation. His eagerness to show the fan to Talu, to learn if she would have any explanation for its astonishing change, was even greater now. Weston forced himself to tear his eyes from the fan and placed it again in his pocket. Then he left the room ...

TALU sat white faced, rigid in fear on the divan in her

apartment. Her eyes were fixed alternately on the small clock

atop the teakwood table to her left and the motionless Mr. Shido,

who sat stiffly in a chair by the door, automatic resting on the

white crease of his trousers at his knee.

It was almost six-thirty.

Mr. Shido hadn't spoken in over fifteen minutes. For perhaps five minutes after he had called Weston's hotel to leave the message, Talu had sobbed sickly, uncontrollably, in terror.

But her tears were over now; her eyes were dry. There was no emotion left in her but the terrible tension that came with waiting.

Twice it had seemed that Weston was outside. Talu had been certain that she recognized his step. But the sounds had moved on past the apartment.

Talu was realist enough to know that her despairing hope that Weston might be somehow prevented from arriving at the apartment was an impossible one. He would come. Nothing would prevent it. He would arrive within the next few minutes.

Footsteps sounded in the street once more. Talu's eyes widened. Her swift glance at the clock showed that it was precisely six-thirty.

Shido had seen her sudden reaction to the steps, her glance at the clock. Now he rose from his chair.

"It is Weston?" he demanded. "You know his walk?"

The steps had paused, apparently before the apartment.

Talu rose from the divan. Shido whipped up the automatic and trained it on her instantly.

"It is Weston!" Shido hissed in satisfaction.

Talu stood beside the teakwood table. A small, soapstone cigarette box was within reach of her hand. Talu took a deep breath. The footsteps outside sounded nothing like Weston's. But she said:

"Yes. It is Weston."

That split second, in which Shido turned involuntarily toward the door, was all that Talu needed. With lightning swiftness, she swept up the soapstone box and in the same gesture hurled it straight at the side of Shido's skull.

The Jap had time only to turn halfway back toward her. The box crashed into the side of his skull a fraction of a second before his finger triggered the automatic twice.

The noise of the gun blasted deafeningly through the small room, the sound of the shots so close together as to be one.

And then Shido was sinking to the floor, dazed, semi-conscious, the gun slipping from his fingers as an ugly splotch of blood oozed darkly from the side of his crushed skull.

But Talu, too, was sinking slowly to the floor, a crimson blotch inking the white tunic of her blouse. Both of Shido's shots were buried in her breast.

Shido was struggling, clawing at the rug with talon-like fingers in an effort to retrieve his gun. It was Talu who reached the gun first, dragging herself across the floor with the last of her ebbing strength. Her hand closed around the weapon and she managed to bring it up long enough to spend the remainder of its bullets into what was left of Mr. Shido's skull...

YOUNG Weston arrived at the apartment some ten minutes later.

Of course he was unable to gain admittance. There was no one

alive to let him in. For some fifteen minutes he rang futilely.

And then, bewildered and bitterly despairing, he left to carry

out his "messenger duty" at the outskirts of Kowloon.

Weston had no way of ever knowing what became of Talu. For the Jap bombers struck at Hong Kong in all their treacherous fury the following day. The day, incidentally, on which they duplicated that cowardly attack over Pearl Harbor.

The apartment in which the bodies of Talu and Shido lay was decimated along with other civilian dwellings, and though Weston saw the tangled debris he dared hope that somehow Talu was with the refugees who had escaped on the first day of the attack.

Weston was able to escape before the insular metropolis fell to the hordes from Nippon. Managed, incidentally, because his own "messenger duty" was successfully carried out.

It is ironic that Weston still swears he shall find Talu again when this great horror has ended. And it is doubly ironic that he still carries her fan, and is utterly bewildered by the fact that the gorgeous colorings it assumed are no longer in evidence. The colors of love and youth and beauty, rose and saffron, tinted golden, are gone. The fan is once again a dried brown hue. And the black lacquered sheen covers the faded characters. Black—the color of death...

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.