RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

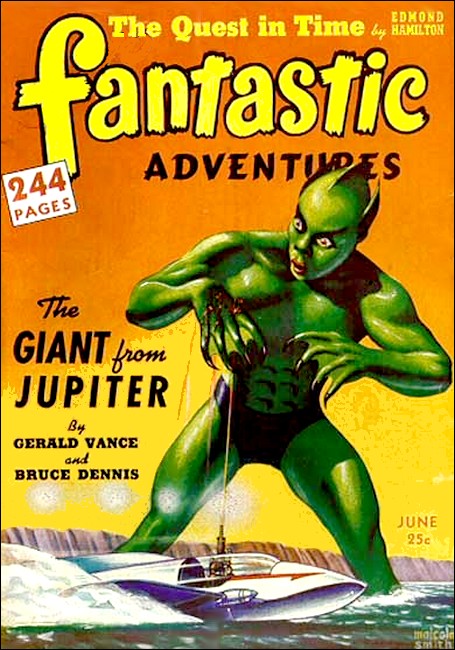

Fantastic Adventures, June 1942, with "Mr Hibbard's Magic Hat"

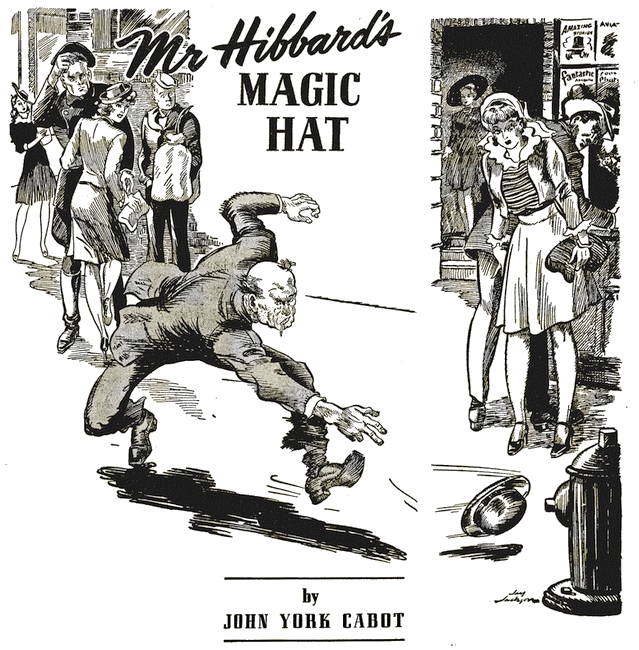

"C'mere, dang ya!" snarled Hibbard, in pursuit of the hat.

Mr. Hibbard, bum, became quite a different

man when he wore this

new hat. It seemed to have a magic quality that gave him new powers!

THERE were some people who called Herbert Hibbard a bum, and it is just quite possible that they were right. Certain it was, that Mr. Hibbard's fondness for hard toil and honest employment could not compare to love of leisure and bottled delights.

And even in Herbert Hibbard's neighborhood, which was most certainly a squalid and poverty ridden section of town, he was not considered a successful, or even respectable, man.

Mr. Hibbard lived in a small, poorly heated flat with a large, overworked wife. And aside from the wife and the flat—the rent of which was constantly in arrears—Herbert Hibbard's worldly possessions consisted of an unquenchable thirst and three children.

It might have been that Mr. Hibbard was not ambitious, or it might have been that he had no dreams. The social workers who occasionally came prying around Herbert Hibbard's section of town were always at a loss to explain the reasons for his peculiar position in the social scheme of things. Unable to find any place for him on their long lists and charts and graphs, they generally gave up in defeat and made a check mark beside the heading of "Habitually drunk."

Which was not at all the truth. Herbert Hibbard was a thirsty man, indeed. But he never had quite enough nickels and dimes to stay habitually intoxicated, and very often would go weeks without taking a drink. On what poor Mrs. Hibbard referred to as "Herbie's bad weeks," he would, of course, be gloriously drunk.

But drunk or sober, Herbert Hibbard was always utterly happy. Which in itself was enough to give him a permanently peculiar position in the social scheme of things.

And on that bright, May afternoon when Mr. Hibbard leaned comfortably against the wall outside Joe's Tavern, placidly baking in the spring sunshine, he was just as happy as he had ever been in all his blissful life.

Unperturbed by the fact that he was standing outside of Joe's Tavern because Joe Himself would no longer allow him inside until he paid up an eighty cent bar bill, Herbert Hibbard gazed fondly at the ragged little urchins playing tin can hockey on the dirty tenement street.

It was an unusually windy day. One of those stiff, spring winds common to the season, that sent dirt and dust and yesterday's newspapers swirling up and down the avenue in constant miniature cyclones. Mr. Hibbard, who had tilted his battered derby forward over his eyes to keep out the sun, suddenly found his old and trusted headgear swept up and off his head by a particularly strong gust.

WITHOUT foolish haste, Mr. Hibbard reached

up, touched his bald head, realized his derby was

gone, and then looked calmly down the street to see it

pinwheeling along at a merry rate almost a block away

by that time.

Not being a man of quick and impetuous decision, Herbert Hibbard watched his derby roll all the way to the corner intersection before he decided to go after it.

He started down the street unhurriedly, keeping his eye firmly fastened on the fugitive headpiece as it hesitated, in a counter gust of wind, on the edge of the intersection curb.

Herbert Hibbard hadn't covered another five yards before the derby decided to go directly along as before and skewed out into the center of the intersection.

And it was five seconds later when a long, black limousine, chauffeur driven, rolled across the intersection and directly over Herbert Hibbard's headpiece.

Even though still fifty feet away from the scene of the tragic accident, Mr. Hibbard heard the squash and saw the resultant mess of his derby seconds after the limousine's tires crushed mercilessly over it.

But—probably because he had started in that direction and saw no reason now for stopping—Herbert Hibbard continued toward the intersection, noting that the luxurious limousine which had destroyed his headpiece had come to a halt.

And when Mr. Hibbard reached the intersection, the chauffeur was already getting out of the front seat to come around and ascertain what he had hit.

Mr. Hibbard arrived beside the forlorn remnants of the derby seconds before the chauffeur had stooped to pick it up. The uniformed gentry spoke harshly:

"That your hat, buddy?"

It was characteristic of Herbert Hibbard that he had already adjusted himself to the change in the situation. He straightened up, holding the crushed remains tenderly in his hands as a nature lover might hold a fallen bird.

"That was my hat," Mr. Hibbard corrected him with some dignity.

The chauffeur, his sadism tickled to the quick by the sad appearance of the derby, laughed unpleasantly.

It was then that the Man In The Striped Pants stepped out of the rear of the limousine to see what was going on. Actually, he was wearing considerably more than striped trousers. There was a double breasted black coat, an ascot tie, gates-ajar collar, patent leather shoes and gray spats. He also wore gray gloves, carried a cane and, coincidentally enough, sported an expensive black derby hat.

The Man In The Striped Pants took in the situation with a glance, then he bowed apologetically to Herbert Hibbard.

"I'm frightfully sorry, old boy," he declared. "My car seems to have demolished your hat utterly."

"S'all right," said Herbert cheerfully. "Don't see how it could have been avoided." He stared, fascinated by those striped trousers.

"But it isn't all right," protested the Man In The Striped Pants firmly. "I have ruined your headpiece. Naturally I will make repayment." He fished into his back pocket.

Herbert Hibbard caught the implication of the gesture. He shook his head negatively.

"It wasn't a new hat," said Mr. Hibbard, "even when I first got it. And I've had it close to ten years."

THE Man In The Striped Pants seemed surprised.

His eyebrows notched up in wonder. Then, suddenly, he

grinned warmly.

"You are unusual indeed, sir. An honest man." He paused. "We seem to be about the same size, generally. It wouldn't surprise me if this," he paused to remove his own derby, "would fit you."

As a look of protest crossed Herbert Hibbard's features, The Man In The Striped Pants said quickly: "This is not a new hat either. So it will be quite an even exchange."

Herbert Hibbard eyed the extended derby doubtfully. "It looks new to me," he said.

"Well," the other admitted, "it is new as far as I am concerned, but as soon as it passes from my hands to yours it will be second hand."

Mr. Hibbard considered this gravely an instant. Then he smiled.

"That sounds right," he said. He took the proffered derby, gazing in awe at the bright and glittering newness of it. He had never seen anything that looked quite so expensively luxurious.

The Man In The Striped Pants said: "Try it on. See if it fits."

Mr. Hibbard placed the derby cautiously on his bald head. He smiled tentatively at the Man In The Striped Pants, who grinned back, indicating that it looked well.

"There you are," he told Herbert Hibbard. "It fits perfectly. I hope you enjoy it as much as I have. Good day, and good luck."

And then, before he knew it, the Man In The Striped Pants was back in the car, and the limousine was roaring away, leaving Mr. Hibbard standing proudly in the center of tooting traffic in his new derby hat.

Stepping over to the curb, Herbert Hibbard shifted his new hat around his head experimentally. It did fit perfectly at that. More perfectly, in fact, than his old one.

He cocked it jauntily a little over his right eye as he started back up the block. There was class about this derby, and no question about it.

In a store window, Mr. Hibbard took a sidelong peek at his reflection. Undeniably, his new possession made him look almost prosperous.

And then he realized that, even though he'd cocked it over his right eye, the derby had now slipped back to a decorous, churchish, even keel.

Mr. Hibbard frowned faintly, cocking it back over his right eye.

But in the next window that he passed, Herbert Hibbard saw that the headpiece had again assumed a dignified, solid set on his bald pate.

He paused, removing the derby to look for a concealed spring inside of it. He found no spring, but his eyes did see the edge of a ten dollar bill protruding from the inner sweat band.

Whistling in surprise, Herbert Hibbard extracted the ten dollar bill from the hat. Then he turned and looked back at the intersection; but of course the limousine had long since gone.

He scratched his bald head reflectively. Mr. Hibbard was not a stupid man, and so of course was aware that people—even rich people who wear funny striped pants—are not in the habit of carrying cash around in their hats.

And so Herbert Hibbard arrived at the logical conclusion that the bill was placed there deliberately by the hat's former owner, in the knowledge that it would be discovered by Herbert.

MR. HIBBARD tried to remember how long it had

been since he had seen so much money in one hunk. Then

he gave it up and smiled happily, pocketing the bill

and popping the derby back jauntily on his head and

over his right eye.

He had really reason to peek slyly at his reflection in the next store window he passed. For not only did he now look prosperous, but he was prosperous.

Even though the derby had again rebelled against the cocking over the right eye and had asserted itself with balanced dignity on the middle of his head.

Mr. Hibbard sighed. "All right," he murmured, "if that's the way you want to ride, go ahead."

The derby seemed to nestle closer to his skull, after that. And when Herbert strode in through the doors of Joe's Tavern a few minutes later, it still rode in balanced splendor.

Joe Himself was behind the bar, and when he saw Mr. Hibbard in the new hat, a look of surprised speculation entered his eyes. Surprised speculation and a faintly grudging respect. He didn't even yell his usual stay-out-until-yuh-can-pay-me routine.

The idlers in the bar were also shocked into a slightly awed silence. A silence that reached its dramatic peak when Herbert Hibbard reached into his pocket and casually flipped a ten dollar bill across the surface of the bar.

"There Joe," said Mr. Hibbard with casual indifference, "take the eighty cents I owe you outta that."

In silent awe, Joe rang up eighty cents and fumbled in the cash drawer until he had assembled Herbert Hibbard's change. And when he passed the bills and silver back over the bar to Mr. Hibbard, he said respectfully.

"What'll yuh have, Herb? On the house, acourse."

Herbert Hibbard opened his mouth to reply, and caught a reflection of himself in the greasy mirror back of the bar. The new derby was too much above these definitely sordid surroundings. He looked far too dignified to be ordering cheap whiskey in a cheap bar. In spite of his thirst, he closed his mouth.

"I'll take a rain check on that, Joe," Herbert heard his own voice replying. "But nothing now."

And with that he pocketed his change and strode casually from the shocked silence of the barroom. His derby hat rode like a crown atop his skull...

CURIOUSLY enough, people's minds are such that

they meet with bland indifference even the most superb

accomplishments of those they have long known to be

standardly capable. Yet, should a long acknowledged

idiot add two and two and make four, or a lowly knave

give up petty larceny for Lent, the idiot is suddenly

raised to the status of a genius and the knave

canonized a saint.

So it was with Herbert Hibbard.

Mr. Hibbard, whose garments had always caused even the old clothes brokers to move to the other side of the street when they sighted him, had been seen by the residents of his neighborhood in an incredibly expensive new derby hat.

Also, Herbert Hibbard, who avoided his creditors as cunningly as a fly avoids a swatter, had of his own volition walked into Joe's Tavern and casually wiped out a debt.

Lastly, the same Mr. Hibbard, who had only to prick any one of his veins to tap a supply of straight alcohol, had passed up the offer of a free drink and strolled out of the bar with clear eyes and a dry gullet.

Gossip being what it is, and neighborhoods like Herbert Hibbard's being what they are, it took a scant fifteen minute for these startling bits of information to fly throughout his square block.

And these circumstances, which would have merited no notice had they been observed of an ordinary, respectable citizen started the previously mentioned curious reaction in the minds of Mr. Hibbard's neighbors.

Herbert Hibbard was not an idiot, so they didn't call him a genius. Neither was he a knave, and so, consequently, placed on a pedestal. But being a no good, an aimless idler, an unproductive member of society, the effect of Mr. Hibbard's transition on his neighbors, through the magical power of their tongues, was to raise him in their astonished eyes to the status of exemplary citizen.

The fact that he had apparently reformed over night, only served to heighten the respect in which they held him.

At four o'clock that May afternoon Herbert Hibbard had been a bum. At four thirty on the same afternoon, through the strange power of a derby hat and the not so strange power of a ten dollar bill, he was an esteemed man.

And at five o'clock, when Mr. Hibbard, who had been but faintly aware of this reversal of popular opinion, arrived at his dingy flat, he was very much amazed to find his large wife, tears of joy in her eyes, waiting for him at the door with open arms...

MRS. HIBBARD'S first words were even more

bewildering to Herbert. For even as she wrapped her

steamy red arms around him, she sobbed joyously:

"Oh, Herbert—they told me!"

"Did they, now?" Mr. Hibbard asked, cautiously noncommittal. He wondered what in the hell accounted for this outburst.

Mrs. Hibbard released him and stepped back, eyes aglow with watery admiration.

"You look so fine!" she exclaimed.

Herbert Hibbard smiled in sudden realization. He cocked the splendid derby hat over his right eye, and stepping back permitted his wife to view the wonder of it all.

"Like it?" Mr. Hibbard asked self consciously.

"You look so, so," Mrs. Hibbard fought to find the word, "so dignified!" she concluded ecstatically.

Accepting the compliment, Herbert Hibbard turned to view his reflection in the cracked hall mirror. And then he frowned in slight irritation. Once again the rebellious derby had settled back with smug respectability to a sedate, dead center position.

It was then that Mr. Hibbard caught the pungent odor of roasting duck coming from the dingy kitchen in the rear of the flat. Roast duck—his favorite dish.

Herbert Hibbard wondered how his wife had managed to afford the delicacy. It was, after all, little enough that she made taking in washing. Perhaps, he thought pleasantly, one of the kids had landed a newspaper route.

Mrs. Hibbard had seen the quiver in her husband's nostrils. And now she beamed.

"I went out an got it special," she explained, "as soon as I heard. We'll be able to afford things like that more often, with the extra money coming in now." She sighed. "I'm so proud, Herbert. You with a fine job!"

And suddenly the horrible truth crashed in on Herbert Hibbard. It left him quite definitely, breathlessly stunned.

IT was all too tragically apparent.

The sight of his new derby hat, the fact that he'd paid a bar bill with a ten dollar note, and the damning evidence that he'd strolled from a saloon perfectly sober, had started an incredibly vicious rumor, namely, that Herbert Hibbard had got himself a job and sworn off liquor!

And somehow this malicious gossip had carried to Mrs. Hibbard!

Herbert Hibbard opened his mouth to protest, to deny this infamous misconception before it went any further. However, two things prevented this.

One was the overwhelming sense of respectability his new hat filled him with. A respectable man couldn't confess to being unemployed. Not a man in possession of a hat such as this.

The second was the look in Mrs. Hibbard's watery eyes. Always Herbert Hibbard had been able to look into the weary orbs of his spouse and find there affection and patient tenderness. But as far back as he could remember, this was the first time he had ever seen pride, and its accompanying emotion, respect, in her gaze. And in spite of himself, he couldn't destroy her delusion.

So Mr. Hibbard sighed, and removed his new derby and walked into the dining room. Trouble, for the first time in countless happy years, now rested heavily on his furrowed brow...

A wise man once declared that fate is never willing to let well enough alone. And fate, which had this day given Herbert Hibbard an aura of respectability and an overload of trouble, could no more retire from the scene than a drunk can leave a bar. Fate was busily having a hell of a time for itself.

It sent the reporter from the Daily Banner into Herbert Hibbard's neighborhood. And the neighbors sent the reporter to the Hibbard doorstep.

The reporter was a smiling chap, and quite pleasantly he explained the purpose of his call to Mr. Hibbard who met him at the door.

"You've heard of the Daily Banner's 'Citizen of the Day' contest, of course," said the reporter. And then, in case Herbert Hibbard hadn't, he went on to explain.

"Each day of the week for the next two weeks, the Banner is scouring the metropolis for some man who, although not prominent in the newspaper sense of the word, is an important figure in the tiny community he lives in."

Wisely, Mr. Hibbard continued to listen and say nothing.

"We picked this neighborhood by chance, and canvassed the block, punching doorbells and asking everyone we talked to who, in their present opinion was an outstanding person in the block. Almost unanimously, Mr. Hibbard, they named you," the reporter concluded smilingly.

Mr. Hibbard's wife had come up behind him during the bulk of the explanation, and her eyes were again aglow with watery pride. Herbert Hibbard, however, shuffled his feet uncomfortably.

"Aren't you pleased, Mr. Hibbard?" asked the reporter. Then he added, "There's a hundred dollar prize attached to your being selected, you know."

Behind her husband, Mrs. Hibbard gasped.

Another man came climbing up the stairs behind the reporter at that moment, and the reporter, glancing back, explained.

"My photographer," he said. "We'll want Mr. Hibbard's picture for tomorrow morning's edition."

"Ohhhhh, Herbert!" Mrs. Hibbard squealed.

MOMENTS later, Herbert Hibbard, derby hat

resplendent on his bald head, arms folded grimly

across his chest, posed for the photographer in the

living room.

"Uncross your arms, please," the photographer asked.

Mr. Hibbard uncrossed his arms, and instinctively reached up to cock his derby over his right eye. But he had no more completed the gesture, than the hat rebelliously shot back to its even keel of dignity.

Mr. Hibbard frowned in stern dissatisfaction at this renewal of the rebel streak in his derby. And at that instant the flash bulb popped white.

"Thank you, Mr. Hibbard," said the cameraman, already repacking his equipment.

"What do you do, Mr. Hibbard?" asked the reporter, notes and pencil ready.

Herbert Hibbard was not a liar by nature. He peeked out of the corner of his eye and saw his wife still present, ears avid for details. He cleared his throat.

"I ah, ahhh," desperately he racked his brain, "am a watcher," he said swiftly.

"A watchman?" the reporter repeated.

"You might call it that," said Herbert Hibbard evasively. In his mind he was telling himself that he did watch things, after all, even if they might only be in the passing panorama of the life that passed Joe's Tavern.

And then the reporter was asking Mrs. Hibbard questions, such as how long had they been married, how long had they lived here, how many children did they have, and the like.

And finally, as he was leaving, the reporter scratched Mr. Hibbard's name on a hundred dollar check and presented it to him.

Herbert took the check with a smile of thanks and an inward feeling of misgivings. Without a qualm he turned it over to Mrs. Hibbard, for didn't he have nine dollars and twenty cents in his pocket? And wasn't that all the money a man would need for quite a spell?

Ecstatically, Mrs. Hibbard disappeared into the kitchen. Mr. Hibbard heard her shouting the glad tidings to the neighbors from the window a few minutes later.

Sighing a grave and troubled sigh, Herbert Hibbard sat down in a leaky overstuffed horsehair chair. Then he recalled he still wore the derby.

Removing it, Mr. Hibbard regarded its splendor and dignity with a worried frown and growing distrust...

HIS wife woke him at six the next morning.

This was in itself a catastrophe, for previously Mr.

Hibbard had always snoozed as long as it pleased his

fancy.

"I wasn't sure what time you'd have to leave for work, Herbert," Mrs. Hibbard explained. "I was so excited I forgot to ask."

Jaw set, Herbert Hibbard made no reply.

"Aren't you going to work today?" Mrs. Hibbard asked anxiously. "Doesn't the job start today?"

"No," answered Herbert Hibbard with utter truth. "No, the job doesn't start today."

Mrs. Hibbard backed respectfully and apologetically out of the room. "If you'd only have told me," she declared, "I wouldn't have woke you. I didn't know you wasn't supposed to start until tomorrow."

Burying his head under the sheets, Mr. Hibbard wondered how much longer people were going to put words in his mouth he never said...

IT was ten o'clock when Herbert Hibbard

finally woke and breakfasted. His wife had, by that

time, secured a copy of the Daily Banner,

and while he ate, read the feature story beneath his

picture aloud.

Mr. Hibbard only looked once at the picture. It showed him frowning righteously, and the splendid derby set in the exact center of his head served only to make him look thoroughly, solidly respectable.

At ten thirty Herbert Hibbard was striding down his block in the bright sunshine of the May morn. Striding, mind you, where once he used to amble unhurriedly. The derby, of course, after defying his efforts to cock it rakishly, sat loftily and levelly on the middle of his bald head.

But bright though the morning was, there was no sunlight in Mr. Hibbard's once unfettered soul. Responsibility, like a leaden weight, rode heavily beside the awe inspiring hat.

People who once passed him with a casual, friendly wave, now nodded respectfully, almost distantly, in their efforts to acknowledge his new stature.

Even the little kids, who always laughed and chattered and tugged at his tattered coat, crossed the street as he approached, watching him from the other side with the suspicion and cautious deference they generally held for Kennedy, the beat copper.

And inside of half a block, the weight and worry of the world was on Herbert Hibbard's shoulders. He frowned for the same reason that he walked as if he were going some where. The damned hat seemed to demand it.

No longer did Mr. Hibbard glance proudly at his reflection in the store windows that he passed.

He was aware that, as a man whose picture was being viewed this morning by close to a million people, he was definitely in the public eye and that his behavior should indicate as much. And even had he been able to forget the picture, the presence of the luxurious derby on his bald head would have been enough to sober him to the realization of the respect that was his due.

Much against his better judgment, Herbert Hibbard passed by Joe's Tavern at a swift pace, even though he was once again allowed inside.

And it was a block later that Mr. Hibbard encountered Mike Fagin.

Mike Fagin was a small man in a seedy suit who, at the moment, was smoking a big cigar. Fagin's smile was swift, his voice too shrilly cordial. Of course he was the organization political precinct captain.

"Hello, Herbie old mug!" Fagin chattered. "How's the wife and kids? Like a cigar?"

Mr. Hibbard looked at him with faint surprise. Fagin's attitude toward him seemed unchanged. And then he realized that Fagin had not even glanced at the splendid derby. Fagin's eyes never went above a man's chin, for years ago he had found it much easier to talk politics to voters if he didn't have to look them in the eye.

Maybe Fagin hadn't noticed the hat, Herbert Hibbard decided, but surely he must have seen—

"Did you see this morning's Daily Banner?" Mr. Hibbard asked, putting his thoughts into words.

"Never read the rag," said Fagin. The Daily Banner, as one of the city's most honest and crusading newspapers was ever seeking to throw Fagin's political bosses out on their pants. Therefore, for his bread and butter, Fagin had long ago boycotted that sheet.

Mr. Hibbard seemed to feel his derby pressing inward, as if in an effort to force him to walk on past this objectionable person.

Fagin was still holding forth a cigar, smiling falsely.

Herbert Hibbard reached out to take the cigar, when the hat seemed suddenly much too tight, hurting him sharply. He drew back his hand as if he'd been burned. The hat felt comfortable again.

"Doncha feel like a smoke?" Fagin asked.

Mr. Hibbard shook his head. "Not now," he lied.

"We're having a free blowout at Joe's tonight, just for the bunch in our precinct," said Fagin. "Be sure to drop in, woncha?"

Cigars, cordiality, and free drinks came from Mike Fagin only once a year, Herbert Hibbard knew, and that was always a few days before elections.

"I'll try to make it," Mr. Hibbard lied the second time.

"See yuh there," said Fagin, slapping him resoundingly and disrespectfully on the back. Then he moved off.

Mr. Hibbard sighed as he walked on. Obviously Fagin had not noticed the hat or seen the picture in the paper. He'd probably been so busy buying votes for the elections that he hadn't heard the lies that had grown around Herbert Hibbard.

THEN Mr. Hibbard was aware of something in his

right hand. Several somethings, in fact, which Fagin

had placed there in saying goodbye. Herbert Hibbard

opened his palm.

He looked down at two huge political campaign buttons. Each had the picture of one of Fagin's nefarious sponsors. There was the usual "Vote For" plus the names of the candidates.

Mr. Hibbard sighed, thinking of the days when he'd been a free soul, worn such buttons, sopped up Fagin's liquor, and then satisfied his inner sense of decency by voting for whomever he damn pleased. It had always pleased him that no one could buy the things he believed in. And his minor tricking of Fagin had always seemed symbolically important.

But those free days were gone, Herbert Hibbard realized again. Now he was somebody. He had dignity. He had responsibilities. He had a hat. He had worries.

"Oh hell!" Herbert Hibbard said in sudden savage revolt. And then a thought struck him and he grinned.

With deliberate antagonism, he placed both big political buttons on the band of his hat, conspicuously, as he used to do with his old and undignified derby.

"There," said Mr. Hibbard. "That'll hold you."

There was no breeze in the air. It was a warm, humid day. And yet, suddenly, as if caught by a swift gust of wind, Mr. Hibbard's hat flew from his head and started rolling down the street!

Herbert Hibbard realized he had gone too far.

"Hey!" he shouted in sudden alarm, starting out after the swiftly rolling derby. "Hey, I'm sorry!"

But Mr. Hibbard's hat kept rolling swiftly along, taking a sudden sharp turn at the first corner it came to. Breathlessly, Herbert Hibbard, quickened his pursuit.

The few passing pedestrians who paused to watch him chase after the indignantly fleeing headpiece, gaped in astonishment as they realized that there was no wind to carry the hat along at that pace whatsoever.

Turning at the corner, Herbert Hibbard's wild gaze saw his expensive hat wheeling sharply to roll down an alley. And when he came to the alley, the derby had just cleared the fence of a dirty back yard.

And then Mr. Hibbard was unable to find the exact back yard into which the hat had leaped. He searched all the back yards of the alley frantically for the next half hour, but to no avail.

His wonderful derby, in rage and humiliation, had left him!

Herbert Hibbard, during the ensuing five hours in which he wandered dejectedly, forlornly, about the streets of a nearby neighborhood, was undergoing the second major transition in his previously tranquil existence.

For there had been a fascinating attraction in the mind of Mr. Hibbard toward his but recently acquired derby. In the brief hours in which he had owned and worn the headpiece, painful though the results of the wearing had been, Herbert Hibbard had become almost fatally attached to it.

Mr. Hibbard had felt, somehow, that the hat and what it brought for him was not for him. Nonetheless, like the cinema hero who is fatally ensnared by the luscious but evil siren, Herbert Hibbard had hated to lose the beautiful cause of his troubles.

But unlike the hero, Mr. Hibbard didn't blow out his brains in the last reel. He just walked, mentally stifling the pangs of loss, telling himself, with absolute candor, that already he was beginning to feel like his old and happy-but-unrespected self again.

And when he returned to his own neighborhood minus the splendid headpiece, he was treated, much to his delight, as he had been always treated in the pre-hat era. He went directly to Joe's Tavern.

NO one at the bar looked up when Herbert

Hibbard entered the saloon. There was a considerable

crowd there, and Joe himself was behind the bar. In

the center of festivities was Mike Fagin, his shrill

laughter cutting through the smoke like a knife.

It was Joe himself who first noticed Mr. Hibbard.

"Hey, there's Herbie," he called.

Mr. Hibbard smiled amiably and moved over to the bar to get in on some free liquor.

It was then that Joe himself brought the splendid derby hat out from behind the bar.

"Here, Herbie," he said. "I found this in an alley on my way over, and I said to myself I'll bet this is Hibbard's hat. Is it?"

Joe handed the hat across the bar to Herbert Hibbard.

Mr. Hibbard looked at the hat. The political buttons were gone from the band, but there were tiny pinholes to mark where they'd been. The smooth nap was roughed all over, and quite instinctively, Herbert began to brush it back carefully in place. One side of the brim was slightly dented. It smelled smokey—no doubt from the hours it had been behind the bar. There were several whisky and gin stains on the crown. On the front brim there was a slight burn, as if someone had flipped a match away that had fallen there before going completely out.

Herbert Hibbard quietly, and with the dignity he felt compelled to assert, did what little he could for the damaged derby. Then he placed it carefully on the exact center of his head.

"What'll you have, Herbie?" Fagin called.

Mr. Hibbard was about to shake his head negatively, about to turn and stride resolutely from the saloon in his battered but still obviously expensive derby, when quite of its own volition, his hat slid rakishly forward over his right eye.

Startled, Mr. Hibbard placed the derby on an even keel, and again it slipped to a rakish angle over his right eye.

Mr. Hibbard took a quick glance at his reflection in the greasy mirror behind the bar. He grinned, and suddenly had the very definite impression that the hat was grinning also.

A hat, reflected Herbert Hibbard, can learn an awful lot in a short time.

"What'll you have?" Fagin repeated. Mr. Hibbard grinned out at him from under the rakish slant of his expensive though battered hat.

"The usual, Mike, of course," said Herbert Hibbard with all his old time good cheer....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.