RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

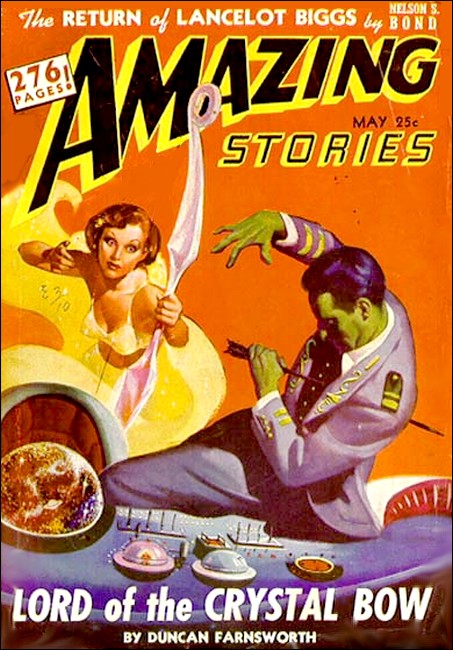

Amazing Stories, May 1942, with "Twenty-Four Terrible Hours"

Suddenly, an expression of terror crossed the professor's face.

Professor Campbell loved his wife, but he was aware that she didn't love him. This led him to a strange act—he gave her the freedom she wanted, via a time machine!

ON the morning of July 1st, Professor Calvin Campbell rose at five o'clock. He had slept with the alarm beneath his pillow, and its ringing had been loud enough to wake him but soft enough not to wake his wife, who still slept soundly in the twin bed on the other side of the night table.

Professor Campbell dressed quietly, quickly. A few moments later he stood over his wife, looking down at her gravely. This was a sort of farewell. He'd never see Kathleen alive again, except for one last moment when he'd be beside her yesterday.

Kathleen was much younger than Professor Campbell. All of twenty years younger. And in her sleep she never looked more youthfully lovely.

Campbell sighed. He deeply regretted what was to happen. But the situation as it was had finally become unendurable. He couldn't stand it any longer. Loving Kathleen the way he did, it was impossible to go on like this.

Kathleen sighed in her sleep and turned over on her side. Her blonde hair glistened against the white pillow like golden webs of silk.

Kathleen had been out with young Vickers until three in the morning. Campbell had been awake when his wife came in. He hadn't let her know that, however. Young Vickers had taken Kathleen to that meeting in Marshall Township, just on the other side of the mountains. They'd wanted Campbell to come, of course, or said they did, but the older Professor had excused himself, pleading work to be done.

Campbell couldn't find it in him to hate Vickers. Vickers was a pleasant enough chap. He was handsome, youthful, around Kathleen's age. And in his daily contact with Vickers at the College Laboratory, Campbell was aware that the young man had a brilliant future in store for him; knew this, also knowing that Vickers was in love with Kathleen.

Vickers had come to teach at the college over a year ago. He'd started as an instructor. Campbell had been responsible for his rise to a professorship; had made sort of a protege of him until he finally realized what was going on.

Campbell even found it hard to blame Kathleen for liking the handsome and personable young Vickers. He himself was neither young nor handsome. He was just a rather old professor in a somewhat obscure college, holding down a young and beautiful wife.

Kathleen had never complained. She wasn't the sort to complain. But Campbell had realized that it wasn't working out, that it could never really work out. And when Vickers joined the staff of the College, Campbell had calmly faced the inevitable.

THREE months ago Campbell had made up his mind. That had been the

week when the older professor learned that young Vickers was

slated to take the head professorship from him at the start of

the following term.

Campbell had been bitter. But he kept his knowledge to himself. He didn't even let Vickers in on the fact that he knew. But Vickers had been told. The fact that it made the younger man sincerely and sickly unhappy, didn't alter the circumstances for Campbell. This was the final blow.

And Vickers had gone to Kathleen, had told Kathleen that he'd been elected to replace her husband. Kathleen, also, hadn't found the courage to bring it up before Campbell. She felt sorry for him, terribly sorry, Campbell knew. But he didn't want pity from her. He'd never told Kathleen that he knew.

There had been planning, then; careful and thoughtful planning. The other thing had worked in admirably. He'd thought that the other thing would some day reap for him the rich reward of everlasting scientific fame and fortune. He'd never told a soul about the other thing, even Kathleen. He'd wanted to keep it from her until he was certain. He'd planned to tell her when the experiments were positively completed. It would have been what he'd always wanted to give her—riches and success. He'd been certain that it would have compensated to her for the fact that he was an older and more drab man.

It all changed, however, even to the other thing, when Campbell discovered that Kathleen and Vickers had found one another. It made the other thing too late. It made it worthless. For what was fame and fortune when he didn't have Kathleen?

And so he'd planned to use the other thing as an instrument of a different kind of compensation. For Campbell determined that if he couldn't have Kathleen, no one else could have her.

Vickers couldn't have her.

NOW Campbell bent over his wife and kissed her gently on the

cheek. It was better, this kind of a goodbye. He could think for

a moment, this way, that she was still fully his wife, that she

still loved him completely.

Then Campbell turned and left the bedroom.

There was no one around the campus but the watchman when Campbell turned his automobile up the driveway that led to the college laboratories. Campbell had been with the college almost as long as the watchman had, and he stopped his car beside the old man and leaned out.

"Up early this morning, aren'tcha, Professor Campbell?" the watchman smiled.

Campbell forced a smile.

"Up very early, Mike. But then there's a lot of work I have to catch up on."

Mike nodded and said something else.

Campbell waved his hand and threw the car into gear. Two minutes later he parked behind the science building and was climbing out of the car.

"This will all change," Campbell told himself. "I must remember that."

Then he had his keys out of his pocket and was fumbling at the rear entrance to the science building. The door swung inward and Campbell flicked on a light switch that illuminated a locker-lined corridor.

Campbell walked along the corridor, and at the end he flicked another light switch. Then he marched up the three flights of stairs that led to his own laboratory.

He let himself into his personal laboratory and turned on the lights. He methodically began to change into a clean white smock. Moments later and he was rummaging around through a maze of equipment in a closet.

When he brought what he needed out of the closet, Campbell went over to his work bench in the corner. There was a long, almost oval object under a white sheet atop the table. Campbell removed the sheet and looked down at the machine of steel and glass that lay there. This was the other thing. This was the object over which he had labored these many years. This was his secret.

This was a Psychotrans Time Machine.

This would project the mind of a man into the past or into the future. This would open to man the undreamed-of possibility to travel through Time. Through this machine the mind of a man in the present could be placed in the body of a man in the past or the future. It was the culmination of Campbell's scientific genius. It was the dream of achievement which every scientist from Pythagoras to this modern day had groped for.

And it was Campbell, the drab, obscure, aging professor of a small western college who had finally conquered Time.

BUT Campbell wasn't thinking of this as he set about to work. He

wasn't thinking of anything but the task he had at hand. He was

going to project his mind into the past. He was going to project

his mind into Yesterday. This was July 1st, Campbell was going

back a scant space in Time to June 30th.

And Campbell was going to send his mind into the body of young Vickers.

Campbell sat down at the bench before his work table. He busied himself over a series of charts and graphs for an instant, arrived at the calculations he wanted, then rose again.

Now Campbell tinkered with the delicate dials on the face of the steel and glass machine that would send his brain back into Time.

According to Campbell's calculations Kathleen and young Vickers must have left the meeting at Marshall Township sometime around eleven o'clock last night. That was a scant seven hours.

Campbell was going to send his brain back seven hours into the past. There, at that time, his brain would take possession of Vicker's body.

Vickers and Kathleen would be leaving Marshall Township in the young chap's car at that time. Ahead of them would be the sheer twisting, dangerous roads that lay along the mountain between Marshall Township and the college.

An automobile, roaring through the night, might very well hurtle off the side of one of those twisting roads. Hurtle off the side—

There were jagged rock beds at the bottom of those gruesome drops. An automobile, twisting, falling through the darkness down to these rocks—

Campbell sorted his equipment carefully. There was a round, glass and metal headpiece. Wires led from it. Campbell plugged the ends of this wire into his Time machine.

He made some more adjustments, consulted his charts again, and nodded in satisfaction. Everything was in order. Everything was ready. Campbell paused a moment.

"I must remember," he told himself, "that everything will be different. Everything will change."

Yesterday would change, of course, for Campbell. Last night would change for Kathleen and young Vickers. When you tamper with what has passed it is wise to remember that certain elements in the present also change. Campbell was prepared for this.

He was prepared to receive the shocking announcement that his wife and young Vickers had been killed when the car plunged off the cliff side. It would be a few hours anyway before it was discovered. It was good to remember not to mention having left your wife home; asleep, when she died the night before.

Campbell donned the headpiece.

NOW he reached forward and made the final adjustments on the

dials of the time machine.

On the right of the machine was a switch which Campbell hadn't touched. Now he threw the switch forward. His body suddenly began to tingle with electrical vibrations.

The dials on the time machine flickered for an instant, then climbed slightly and stopped. On Campbell's face was an expression of desperate concentration. He felt himself growing weak. His knees would no longer support him. He sat down on the bench. The dizziness was growing, the room wheeling...

Campbell was suddenly aware that he was looking out through the windshield of an automobile roaring through the night along a narrow, twisting mountain road. His hands were gripped to the wheel of the car.

"Not so fast, Vick," a voice said beside him. "These roads are tricky."

It was Kathleen's voice. Kathleen was beside him, and he was in control of Vickers' mind, in Vickers' automobile, for an instant, in Vickers' body!

He turned to look at Kathleen. The last he'd see of her before she died. She looked gloriously beautiful in the faint glowing reflection of the dashboard.

"Not so fast, Vick," Kathleen repeated worriedly. "I'd like to get home alive."

Campbell looked ahead. There was a sharp turn up there, a very dangerous turn. It was a long drop to the rocks below if you didn't make that turn. He mashed his foot down hard on the accelerator pedal. The turn rushed up at him.

Kathleen's scream pierced into his ears.

Campbell saw the cliff's edge looming up to him, blackly, terrifyingly. He was seized by an overwhelming frenzy of fear. He felt his heart pounding madly.

"Vick!" Kathleen screamed again. "Vick, for God's sake!" She was reaching over toward the wheel, trying to get his fingers from it.

Campbell hung on, frozen in horror, the cliff edge was very near...

IT was half an hour later before young Vickers was able to

light a cigarette, his hands trembled that badly. His face was

still ashen. Kathleen was driving. They were just entering the

little college town.

"I still can't figure out what possessed me, Kathleen," young Vickers said shakily. "It was just as if I was asleep. My mind was in a fog, a complete blank. If you hadn't grabbed that wheel—" He didn't finish the sentence. He put his hand over his eyes and shuddered.

"I know, Vick," Kathleen said. "It was the most horrible thing. I looked at you and it was just as if you were in a trance. I'll still never know how I managed to grab that wheel in time. You were frozen to it."

"God!" Vickers shuddered. "Ugh!"

They drove on in silence. When the girl stopped the car before the residence of Professor Campbell, she turned and said:

"Won't you come in, Vick? Clive will fix you up a drink. I think you need it badly."

Young Vickers shook his head.

"No thanks, Kathleen."

Kathleen got out of the car. Vickers said good night shakily and drove off. Campbell's wife let herself into the house. She called out to her husband. No one answered. She went upstairs wearily. He was probably still working at the laboratory...

THEY notified the young wife of the elderly Campbell the

following morning. It was the morning of July 1st. They broke the

news as gently as they could.

He had been tinkering with some unknown experiment. An electrical shock of tremendous force—similar almost to a sudden terrible fright in intensity—had stopped a heart that was none too strong. He was found dead, sprawled across a shattered machine on his work table.

Later, after the coroner had placed the time of her husband's death, Kathleen was aware that he must have died just about the time the car in which she and Vickers were riding almost plummeted off the edge of the mountain cliff. Everyone agreed that it was the "strangest thing."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.