RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

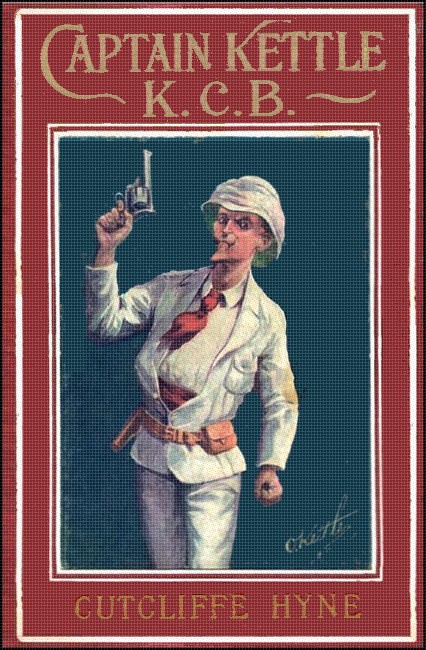

Captain Kettle, K.C.B., 1903,

with "An Exchange Of Legs"

THE Moor who brought the news of the disaster to Fenner in his office in Casadir had never seen a wild animal behind bars, but his description of Captain Owen Kettle in that horrible prison far away in the heart of the Sus country, had much in it that was pathetic as well as terrible.

This man, Mazelle, was the only creature that had escaped alive out of the ambush. Others—men, camels, mules and horses—had straggled, but these had all been cut off as in their panic they headed back for the Sus river up whose valley the caravan had made its way from the Moroccan coast. Mazelle, with a fanatical devotion to his Reis Keetle, had followed him and his captors into that unmapped town of the far African interior, and had there killed a water-carrier, and taken up his water-skin and business through the single desire to be near his N'zaranee chief.

Said Mazelle: "I been fighting man all my life, Excellency. I seen plenty fine men, great sheiks, great kaids. But I never saw one with more man in him than Reis Keetle. That is why I went back to be his follower still, even though he had fallen."

His picture of the common prison, into which the wounded sailor was thrown, was sufficiently horrible, and Fenner remembered with grim dismay that this same Mazelle had been an inmate of more prisons than one himself, and so had grown callous to many of their abominations. The man went on to tell how for three months he had lain in this town, travelling daily between the river and the soks with his skin of earth-reddened water, waiting with a fine Oriental patience for a chance to come at Kettle, and gain speech with him.

The danger of death and torture which hung over him all this time was so obvious that he did not mention it. He recounted only his various attempts to get Kettle to that wicket in the prison through which the inmates were accustomed to thrust out skinny hands for daily alms, and to sell their miserable wares.

At length, after that three months of infinitely dangerous waiting, he saw his man. An emaciated Kettle came to the wicket, a man gaunt and fierce-eyed beyond description, yet carrying a certain spruceness still in spite of the unspeakable squalor of his surroundings. He was offering a mat he had made, sailor-fashion, out of a chance found piece of old rope, either for sale, or in barter for food.

For this poor furniture Mazelle gravely bargained, in competition with other purchasers of prisoners' wares, and in the meanwhile, Kettle, who had recognized the man, and guessed his errand, wrestled with his poor diplomacy to find some message which would sound unsuspicious in the ears of bystanders.

At the same time he was forced, after the custom of the land, to cry up his wares. "Look well at the mat, O purchasers, a mat woven by the arts of the sea, a mat fit to honour the butt end of kaids." To which Mazelle would reply: "Observe this cous cousoo, made from the finest barley and the fattest sheep, and flavoured with butter at least seven years of age. Observe when I stir it with my finger, thus. Observe how splendid is the fatness of that joint of tail. Smell at it, unbeliever, smell!"

At last the purchase was made, and the mat was handed over for the consideration of a bowl of rancid-smelling stew, and the little sailor, in his scanty Arabic, delivered himself thus:

"O purchaser, may Allah's favour increase on you! If you have a master, tell him quickly of the mat that he may come here and himself feel desire for another like it."

"O prisoner," said Mazelle, giving a final twist up to his turban before going away, "O prisoner, I will seek my master, and tell him—and with that, O Excellency-with-the-great nose," he added, on reporting this account to Fenner, "I left the town and ran down the great valley to you here in Casadir above the sea, eating from the country as I came."

"You don't seem to have thriven very much on it," said Fenner, looking at the man's thin, worn face and ragged, stained jelab.

"I earned six wounds on the way," said Mazelle simply, "from those who would have forbidden me food. Had the message been from another, and to another, I should not have found spirit to carry it through."

"Honour shall be done you for this," said Fenner warmly, "in a way that will surprise you. In the meanwhile, take this rifle which will throw eight bullets further than a man can see, and that without reloading."

Mazelle eyed the weapon doubtfully.

"May your Excellency's cough be eternally relieved. But the gun has a long English stock, and I could not use it for powder play."

"I will send the gun down to an armourer in the bazaar, and he shall fit to it a short stock to your liking, with a heel-plate a span and a half in length, and decorate it choicely with ivory and metals."

"Slamma," said Mazelle, brimming over into many smiles. "May your Excellency sit hereafter upon happiness, and have children more in number than the hairs of your servant's beard."

"There, there," said Fenner testily, "that will do," and went out to there and then arrange about a punitive expedition. Any reference to children always irritated him. He was a man who yearned for the joys of domesticity, but consumption forbade him ever to think of marriage.

This capture of Captain Kettle, though entirely unexpected, was by no means untypical of the general restlessness of Southern Morocco. With the assistance of Kettle, Fenner, and—in a less degree—of Mr. McTodd, the Kaid of Casadir, Hadj Mohammed Bergash, had brought his rebellion against the Sultan to a successful end. The imperial troops had been driven away, killed, or induced to change allegiance; caravan trade had come in with a rush; the port had been declared open; and the three assisting British had got a monopoly of the carrying trade overseas, and a large merchanting business in London and Europe. Success had apparently arrived all in a day's time.

But presently the usual Oriental hinderers began to assert themselves with grim, red persistency. With the restarting of the caravans, there was a resurrection of those who lived by looting them. The local robber barons in their hilltop castles sent word to the camel trains that they had recruited their garrisons, and demanded tolls for keeping the peace of the road; the confidence men, the beggars, the saints, and the other parasites dropped the various kinds of work they had been forced into during the days the caravans were interrupted, and with sighs of relief took up again the lighter task of sponging on travellers; and local highwaymen again sat beside each his old section of road, to point out to the solitary wayfarer how much safer he would have been as a unit of one of the larger convoys.

In the souk outside the walls of Casadir men talked these things over in high-flavoured Arabic, not, be it observed, pointing them out as a scandal, but merely as an unfailing evidence of good, sound trade.

It was over this nicety that Captain Kettle made his mistake. Said he, after the particularly atrocious cutting-up of one camel train: "This has got to stop. Til make this Sus valley as safe as Wharfedale, where I live when I am at home, and where my missis and girls are to-day."

The Sheik Bergash spread out two elegant, small, brown hands. "It is the custom, and it always has been the custom with these Berbers. Even the Romans could not stop it when they were here. Moreover, if these fighting men now spread out by handfuls in the castles, and singly along the road, were put out of employ by an armed force, they would presently gather together to assert their rights, and perhaps attack Casadir."

"Those we handle," said Kettle grimly, "will cause very little further trouble to anybody."

"They'd take an awful lot of catching," said Fenner, "and it might lead to complications. Much better wink at things till we're a bit more firmly established here."

But Kettle stuck doggedly to his point. "I've seen the chap that didn't get killed in this last cutting-up. The brutes had lopped the hands and feet from every mother's son of them, and left them to crawl in here as best they could. I don't say anything about these road-agents ruining them; I've been ruined myself heaps of times, and always pulled through somehow; but mutilation's another tune, and I'm going to stop it. By James, yes! I don't ask you two to chip in. Anyway, Sheik, you're wanted here to run the show, and you, boy, must stay to have cargoes ready for McTodd, when he brings the steamboat round. Besides, there's your soft lung to consider. No, I'm the man to arrange these funerals, and we'll call that settled, please, and change the subject."

In this determination then, Captain Owen Kettle had set out from Casadir, and leaving the seacoast behind him, had worked his way up the valley of the Sus River. He had with him a band of men so nicely regulated in size that in the first place they did not attract conspicuous attention, and in the second, they would be able to turn the tables on any attack. Moreover, they were armed with Marlin rifles, which could fire eight shots in eight seconds, and as the local long-barrelled flintlock only fires its eight shots per hour, this gave them a fine advantage.

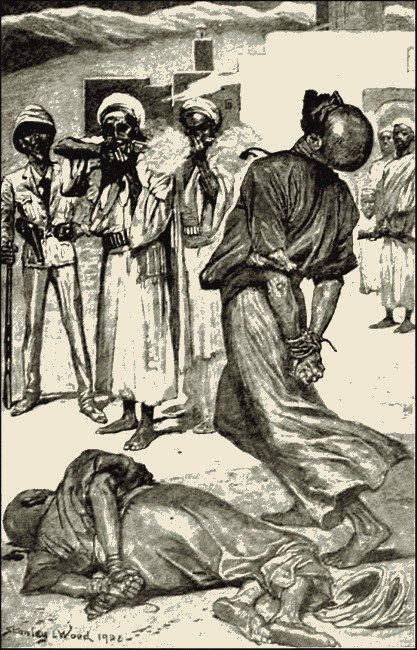

With the help of this following Kettle swept the trade routes with a merciless severity. The men he caught were a hindrance to the development of the country, and incidentally they were murderers. They expected execution, and he gave it them; but to provide them with a better chance of the hereafter, he offered to each the consolations of religion as prescribed by the Wharfedale Particular Methodists. It was a cause of chronic sorrow to him that these should be uniformly rejected.

They expected execution, and he gave it them.

Indeed, had he come across one who promised conversion, I believe the little sailor would there and then have presented him with a plenary pardon out of sheer respect to his faith. But the Moor in this thing is consistent. He renounces his creed for no persuasion, human or divine; and the detail of being killed is always so near to him that it fails in convincingness as an argument.

Captain Kettle's men, then, divided head after head from their corresponding trunks, stuck these on posts beside the trails at about the height of a camel-rider's face, and with their Moorish humour wrote beneath each—"The above has gone out of business."

The wit appealed to the wayfarers' sense of fun, but with that curious Oriental inversion of ideas which the Northerner finds it so hard to follow, the act did not touch their gratitude. Indeed, from his very first interference in the valley of Sus, Captain Kettle made himself disliked. In England they have grown out of sympathy with the professional highwayman, but in Southern Morocco they recognize him as an institution. Periodically, of course, they shoot him themselves, or mutilate him, or avoid him as the chance arises; but there is no doubt that they take a melancholy pride in their local dangers. They are a conservative people.

Finally, Kettle set the crown on his blunders by shooting out of hand a certain Hossein, whom he caught in the act and article of crucifying a comparative stranger. The said Hossein was an old-established nuisance of the roads, and Kettle had been after him for some time; indeed, they had more than once been in close enough touch to exchange messages of defiance; and anyway his culminating atrocity, in which Kettle caught him red-handed, was quite ugly enough to warrant any punishment.

Remained the objection that Hossein was both Hadj and Sidi. Of course to Kettle the mere fact that the man had done the Mecca pilgrimage was nothing in his favour, and the accident of his descent from an ancestor who once had been named saint by the Mohammedan creed, was a trifle worthy of no consideration at all. But to the country at large here was sacrilege. The man was shot accurately enough, but even Kettle's own immediate following refrained from elevating his head on the usual pole; indeed, buried the body undecapitated, after the due washing which ritual ordains; and would have built a shrine above it if Kettle had not angrily interfered and struck camp forthwith.

But other eyes were watching, and other hands did the building, and when he came by that way a month later, there was the shrine, dome-roofed and glittering under the sunshine in its new suit of whitewash. Inside was a tenant, half priest, half trader; a couple of criminals were already in sanctuary; and a knot of business men from the neighbourhood squatted round the walls, and boasted that they had made Sidi Hossein a geographical name, and the site of a weekly market.

Captain Owen Kettle felt annoyed. There is very little use in executing a criminal if the very people you are trying to protect treasure his memory in this way, and raise a sainthouse above him, largely for the protection of other criminals. So for half an hour he let his bitter tongue have full play upon everybody within reach, and in that space of time stirred up some unnecessary enmity.

As a consequence, those who called themselves honest men lent a good deal of practical sympathy to the thieves who were already banded together against him, and the Sus valley became for the little sailor a more dangerous place than even he imagined it.

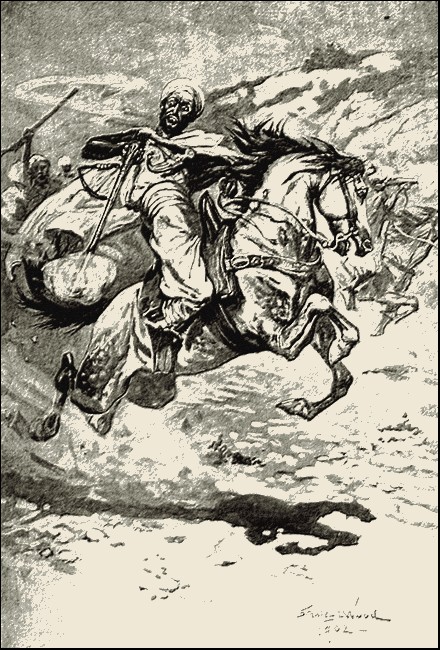

The method of his final undoing was simple and ingenious. A sham fight was got up between a band of the country farmers and one of the fortified robber castles, whose garrison, under the guidance of their chief, Ayoob Bushaib, was notorious for its raids on the merchandise trains. The men of agriculture were by arrangement the victors, and down they came with much firing of guns and display of horsemanship to a dry wad where Kettle was encamped in the shade. They hailed him as Protector of all Merchants; told him how his example had spurred them to a little effort of their own; told further how their attempt had met with brilliant success; and, finally, invited him to come and take over their prisoners, and execute them according to his own tastes.

They came with much firing of guns and display of horsemanship.

As though to give full colour to their story, heads were produced, newly severed, though, of course, this to an Oriental would have gone for little. Any one who knows Southern Morocco can bear evidence that human life is horribly cheap, and that the Moor sticks at little to put the full ingredient of reality into his play. But Captain Kettle; in spite of his vast education, was still a Northerner, and the dripping heads convinced him.

"You'll understand clearly," said he, "that I don't approve of you outsiders taking the law in your own hands, especially when I'm around. You'll please notice also that I've undertaken to keep order in this section of Morocco, and any one who looks on can see I'm doing it. You ought to have come down here to my camp and laid your complaint, and then I'd have mopped up Ayoob Bushaib and his castle-load of rogues before they could think. However, as you have interfered, I'll just ride up and see what sort of muddle you've made of it. No, you may take away those heads and bury them. I've no use for another man's bag."

Presently then, at the head of his own men, with a flanking escort of jubilant farmers, Kettle rode out of the dry watercourse, and up through the argan forest above, skirting the green patches of barley, and making always for the high ground where the castle stood on a knoll.

He held along, entirely unsuspicious of the trap. He noted the frequent rootlings of pigs, and chided the farmers for not keeping them down; he watched with delight the lizards and butterflies, and once picked up a slow-moving grotesque chameleon, and set it to ride on his bridle-rein; and when now and again clouds of gleaming blue pigeons swept over him with a flicker of jewelled breasts, a verse or two of poetry came to his mind and gratified him exceedingly.

Ayoob Bushaib's castle, when they came to it, sprawled ungainly walls on the head of a steep knoll. It was built of amber-collared stone, and showed the usual specimen of patchwork piece-meal architecture. The outer gate, when they arrived up the last slope, lay open, and one of its valves, which was split with gunpowder, still smouldered on the ground. Within, the place was split up into the usual maze of courtyards and houses, tangled with camels, mules and cattle, creepy with the shrill cries of a ruffled harem. Here and there bodies lay—less the beforeseen heads. To a man whose recent months had been filled with the taking of similar strongholds, the evidences of a storm were plain enough.

But as they went through the alleys and courtyards, their escort insensibly dwindled, shouldered aside, as it seemed, by Kettle's own truculent following; and when at last they poured out into the central courtyard of all, which was also littered with the red debris of recent fighting, all the farmers had left them.

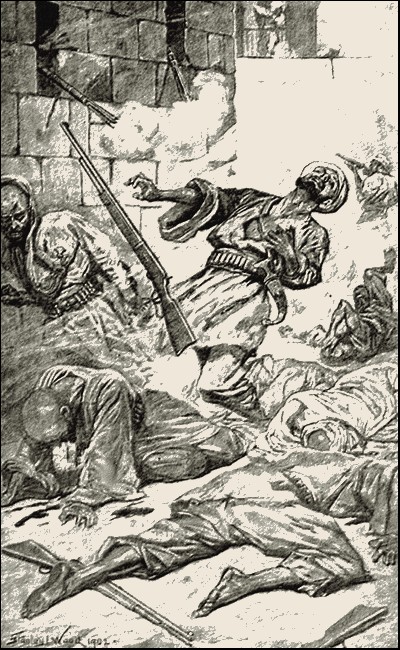

Then there was a quick snapping of shots, and promptly every open door around them was slammed by hidden janitors, and bars ground noisily into the stone sockets. From the loopholes of the walls, from the iron-latticed windows, from behind the parapets of the roofs above, of a sudden there bristled forth the brass-strapped barrels of long Moorish guns, which belched their uncouth missiles with deadly aim, and men were shot dead at such close range that their haiks and jelabs were set on fire by the discharges.

Kettle went down, hit in the head by the first volley, and the rest was massacre. Again and again the guns of the castle's garrison were reloaded and fired, till at last the frenzied survivors below piled bodies together, escaladed the roof, and so won a temporary escape. But a merciless hunt followed on the heels of these, and one by one they were cut down, or surrendered into slavery. Their animals also and camp furniture were captured. Of all the company the man Mazelle was the only soul who kept his life and freedom.

The rest was massacre.

Then came the hour of triumph, and Ayoob Bushaib was far too good a Moor to refrain from making the most of it. Many of his own friends had passed through Kettle's hands, and had been associated with those grim Arabic notes which told that "the above had gone out of business." Well, Ayoob Bushaib had spikes above his own gateways and corner towers, and these were quickly emptied of former occupants, and as quickly dressed with fresher trophies.

"There is exactly one prophet," said Ayoob Bushaib, as he meditated over the grisly array, "and he looks carefully after us, who are his own! These men belonged to the Sheik Hadj Mohammed Bergash of Casadir, but their sending was none of his. The Sheik knows the ways of the road, and respects old customs. Their coming was due to the swine of Inglees, who are now his advisers. They are good men, these Inglees, but they are not perfect, and that is because they are of the N'zaranee faith. None can be perfect who does not acknowledge a single Allah and his one Prophet. But where is this Reis Keetle that fell to-day? I do not see his red beard among these other ornaments."

He went carefully over the heads again, but could not find the one he looked for among them, and was just about to diagnose witchcraft and get uneasy, when word was brought to him that the man lived.

"I was just about to strike his head off, Excellency," said the messenger, "when the infidel opened his eyes and swore at me; and such was the power of his eye that I—I came to ask if your Excellency had any further orders concerning him."

"Is the man heavily wounded?"

"I am no hakim, but I should say not. A shot ploughed the side of his temple and stunned him, but he is a man of spare habit, and moreover a fighting man, and his flesh will know how to make for itself a quick cure."

"He shall be cured," said Ayoob Bushaib, with a wave of the hand, "and presently he shall acknowledge that Allah is Allah, and that Mohammed is his prophet. After that he shall stay among us and tell here of the cleverness of the N'zaranees, which he learned when he was a dog of a N'zaranee himself. In the meanwhile, as he knows nothing of the joys of Paradise which will await him after conversion, leg-irons, wrist-irons and a chain to the waist will keep him from escaping, and keep him also at peace."

Now Ayoob Bushaib was a man of some intellect, and though he had taken every precaution lest any of Kettle's following should escape, and, not knowing about Mazelle, thought he had done this effectively, still from old experience he knew how news will leak out. He took it for granted, then, that the tale of Kettle's overthrow would in time drift to the Atlantic coast of Morocco, and reach Casadir, and a campaign of rescue and revenge would promptly follow. He knew that his own isolated fortress could never hold out against the strong attack of a big force, and so he preferred to insure its safety by sending the prisoner to a town in the next valley, which was better prepared, both in population and defences, for a heavy attack.

It was to this town, then, that Mazelle had followed his late leader, and had taken over the business of the water-carrier, and though he had seen and reported on the weight of poor Kettle's fetters, the squalor of the common prison, and the straits to which he was put to avoid actual starvation, he had not even guessed at the greatest of all the little man's dangers and discomforts.

Ayoob Bushaib, when not acting the robber baron in his hilltop castle elsewhere, was a considerable man in this town away in the depths of Southern Morocco, a farmer of lands on its outskirts, an owner of camels, the lord of Warehouses, and a dweller in a great substantial house, with enclosed gardens and a spacious harem. He was a man of the world—his own small world, that is—and a man, moreover, who understood men—that is, men of the type he lived among. Also, like all Moors, he had a high appreciation of the horrors of the Moorish prison system.

He had taken Kettle's measure with some accuracy. As the prisoner dragged his chains along beside the camels, Ayoob Bushaib had noted his strong, masterful face, and decided that here was no convert to take up the comforts of the Koran on a first invitation. So he made up his mind to mortify his captive's flesh pretty thoroughly before beginning upon him.

Into the common prison then the little sailor was thrown. There were as many innocent men there as rogues, but yaws, fever, dysentery, beri-beri, and the other diseases of the country smote among them all with an impartial hand. From one filthy tank all could drink—or thirst. There was no prison ration. All were gaunt with starvation, and each day saw a death. Only the ingenuity of despair made the poor wretches produce the humble handiwork, which now and again they were able to peddle at the prison wicket for squalid bowls of broken food.

For four horrible baking months Ayoob let these discomforts sink in, watching his man narrowly the while, and at the end of that he fetched him out, and left him chained for half a day to a pillar in one of the garden courtyards of his house. Then he came and interviewed him.

"Thus we deal with dogs," said Ayoob Bushaib, "N'zaranee dogs."

"Then more shame to you for not knowing how to treat animals properly," said Kettle.

"I see that I have brought you out of prison too soon. You are not ready for a comfortable life again yet. I must send you back again for another four months till your brain ripens into intelligence."

Now I think it is nothing to poor Kettle's discredit that he quailed almost visibly at this. The horrors of that ghastly prison had nearly killed him as it was; another four months of them would be unendurable; and, besides, there was a very small chance of his surviving such a spell. So with an effort he got his bitter tongue under control, and spoke to the Moor civilly.

"If you have any offer to make, sir, please let me hear it. I'm not very well just now, so you must kindly excuse my temper!"

"If you are reasonable, Reis Keetle, and do as I wish, presently you shall have a house of your own, and slaves, and, if you wish, wives; and, in fact, every comfort, and be nursed into health again."

The little man bit back his temper with an effort.

"If marrying a lot of Moorish women is part of the contract, you can stop right there. I've got one wife at home on the farm in Wharfedale, and she's all I shall ever want, God bless her. So I'll trouble you not to make any more of your nasty bigamous propositions to me."

Ayoob Bushaib shrugged his shoulders. "That is not essential, and if it please you we will drop that point. I did but offer you what most men want. But, as I say, once you are free, you may suit yourself entirely on that matter."

"You'd better get to the point, sir, and let me know your conditions. You've got me in a tight place, I know, and are able to ask big terms. I suppose you're wanting an order on my firm in Casadir for cash. Well, within reason I will pay. But, mind you, don't ask too much. I've made a bit of money lately, I'll grant. But I've the missis and the girls to think of, and sooner than bring them down to beggary again, where they've been so often before, I'll just refuse to pay you a single peseta, and let you do your ugliest."

"Tut, tut, you're taking me quite wrongly. I'm not asking you to ruin yourself. I'm not asking for a ransom at all. Indeed, I'm offering you a boon, if you will accept it with your freedom conjointly."

"You make me tired. Get your offer out and let me be off back to jail."

Ayoob Bushaib smiled blandly. "You refuse to believe in my good faith, but I assure you it is quite genuine. Throw off your cursed N'zaranee superstition, turn Mussulman, and once you have been to the mosque and said the appointed prayers, you shall be free, rich, prosperous, and can look forward with steady assurance to one of those high seats in Paradise hereafter which are specially set apart for those who see the pitfalls in their old ways."

"What, you deliberately ask me—me—to turn Mohammedan?"

"And I think that, being a sensible man, and having tasted prison, you will do it."

"I'll see you in hell if I do," snapped the little man fiercely. "And that's not swearing. It's a solid theological fact. Send for your niggers to cast off this chain, and let me get back to jail. The stink there is pretty bad, but I prefer it to here. Your breath's just poisonous."

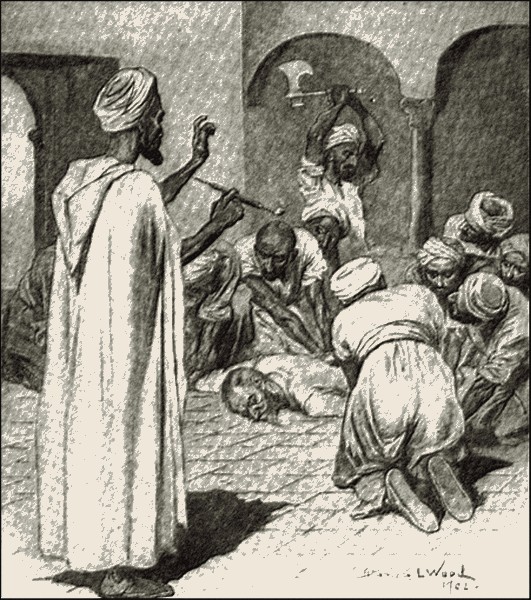

"I give commands here," said Ayoob Bushaib placidly, and clapped his hands. "You must not suppose that the choice of everything will rest with you. Indeed, the matter may turn out quite unexpectedly for you." Servants came, and he gave several orders. Presently they returned. One filled and handed to his master a pipe of keef, which another lit. Others brought an axe, a block, and a dish of glowing charcoal, with searing irons in it. Others unchained Captain Kettle from the pillar, stretched him on the floor—three to each limb—so that there was no possibility of struggling.

Then one slipped the block below his right leg, and another stood by with axe upraised.

Ayoob Bushaib took up the smoke from the keef in two pleasurable whiffs, and for awhile seemed to detach himself from the day's affairs. Then he came back to them again, and addressed Kettle in his usual placid tones.

"In Paradise the houris look askance at a man whose limbs are mutilated. Now I am going to convert you, Reis Keetle, to the true faith, and I am a man of much patience. If you refuse me now, presently I shall lop off a limb. Then I will give you a while to consider while the stump heals. Then will come another offer, and, if there is another refusal, off will go another limb. And so on. You take me?"

"Yes, I do, you son of a dog, and you may cut me up into bits an inch square before I'll so much as think of taking over your blighted religion. Do you know who you're talking to? Do you know I'm the man that founded the Wharfedale Particular Methodists? Do you think that after going to the trouble and expense of making up a creed for them, and being, so to speak, their head organizer when at home, I should change my membership with them for any other bally religion under the sun? No, sir, I'm in Morocco for business, and lately you may say I've been doing police work, and the affairs of the W. P. M. have been in abeyance. But I'm a member of that sect all the time, and its principal missionary, and don't you forget it."

Ayoob Bushaib signed for another pipe of keef, and took its two whiffs slowly. "Is that your last word?" he asked.

"It is, unless you'll let me offer you a prospectus of a religion that will take you up to heaven when your time comes without any mistake or error. W. P. M. is a sure guarantee. May I tell you about it?"

Ayoob Bushaib gave a sign, and the axe fell, cutting through bone and flesh with one sharp crunch. Then the man at the brazero took out his searing irons and dressed the stump.

Ayoob Bushaib gave a sign, and the axe fell, cutting

through bone and flesh with one sharp crunch.

A WEAK and shattered Kettle was being slowly nursed to health by a specially appointed slave. He was still in the prison, but not now in the common courtyard. He was given a small room of his own, with a space of roof to take the air upon. This was the arrangement of Ayoob Bushaib, who was a persevering man. He wanted Kettle as an assistant and co-religionist, and thought that with patience he saw his way to attaining these matters, if he could keep the patient alive while the process of persuasion continued.

But Kettle, though weak in body, was still very active in mind. His leg was lost beyond recovery. But life remained, and other limbs were also his, and he did not intend to be deprived of any of these if it could be avoided. So before the attendant slave he let the lethargy of illness be plainly shown, and his thin, drawn face was a very effective mask for the active brain which lay behind.

Up till now he had despised his fellow prisoners, and failed to see how they could be of use to him. But now a scheme came to him, and he dragged himself among them and to one after another told his plot. They, poor wretches, were as desperate as he, but they were uninventive. Any leader always appealed to such as they if only he offered revenge, and this one promised more besides. They were a large force; presently they would gather malcontents from the town and be larger; and then when the town was theirs they would loot it, oh, so enjoyably. They licked their lips at the prospect.

Thanks to the laxity of Moorish prison arrangements, arms could be bought at the wicket as readily as food, provided one had the wherewithal to pay, and so some weapons came in this way, and others were manufactured.

But the programme, whatever it might be, was suddenly put on one side by another. Ayoob Bushaib came to the prison to see for himself how matters went with his would-be proselyte.

He had with him an armed guard, certainly, of two men, but these, anticipating no danger from the cowed wretches in the prison, walked carelessly. As a consequence, when the wicket was shut, and the word given, they were disarmed and stunned with the same ease with which Ayoob himself was gagged and bound.

It grieves me a great deal to break the continuity of the story at this point, but, on what followed next, Kettle himself flatly refused to give me details; and Mazelle, my other informant, could not. Certainly there was some talk between Kettle and Ayoob of religion, "a N'zaranee religion"—and I somehow guess this to be "W. P. M."—and the rest of the rebellious prisoners demurred. But Kettle rode over their objections with a high hand.

I fancy also that Ayoob Bushaib was given the alternatives of Vert or lop. But of this I can get absolutely no confirmation. The only thing that leads me to imagine that affairs so befell, was the undoubted fact that Ayoob's right leg came off in the prison on that particular date. I should very much like to have been certain on this point, but Kettle was not to be drawn. To tell the truth, he snapped at me.

Anyway, there was Ayoob a captive and disabled, and the prisoners suddenly converted into a body of very desperate men, holding an immensely strong fortress right in the middle of the town. And to make matters worse, there were strong rumours that another, and far more dangerous, enemy, was marching against the town from the outside.

The prisoners as a first demand asked for food, and, as they held out the alternative of setting fire to the prison and incidentally to the town, they got it. Then they declared their rebellion as Heaven-guided, asked for recruits, and got these also. And after this they would have been quite content to sit quiet, and experience the unwonted pleasure of having a full meal. But here that energetic person, Kettle, asserted himself more pointedly, and sent out a demand for tribute in cash or negotiable goods. Here the townspeople drew the line (as might have been expected); a siege was started; and with mad hate to spur either side, there were ugly casualties. But by degrees, as those who held the prison were not taken, public opinion, an easy thing to sway in these Oriental towns, swerved round to their side. Men flocked to them, turning their backs on the legitimate Governor, coming over to Kettle merely because they discerned in him the rising power. And all this time, the rumours of an invader appearing before the gates became more strong.

At last the desperate street fighting came to a sudden end. A truce was called. The other side were open to negotiations. A common enemy had approached from outside, and the only hope of salvation was to amalgamate. And the opposite party offered entire command to this successful rebel, this conquering prisoner, el Reis Keetle.

He took over the command with the truculent remark that he would have helped himself to it if it had not been offered, and then proceeded to tell that the army which even then was sitting down before the walls and commencing siege operations, was sent by his own friends. He pointed out the Excellency-with-the-great-nose, Fenner of the cough; he showed them McTodd, the famous fighting man, and Mazelle, who had slipped through their fingers and carried the news to Casadir; and then he told them that there should be no sack of the place, and that all should be forgiven on their promise to amend their ways and stick strictly to business.

After that he went to have another private interview with Ayoob Bushaib.

"Now, my man," said he, "you've had the creed of the Wharfedale Particular Methodists explained to you, chapter and verse, sufficient times. Has my preaching gone home to you, or do you wish to shed another leg?"

"One question," said the placid Ayoob. "Do you expect to go to your heaven yourself?"

"Such is my trust."

"As you stand?"

Kettle flushed. "On one leg do you mean, you skunk?"

"Yes."

"Certainly I do."

"Then one leg makes no difference in your heaven?"

"Not an inch."

"Then I will come, too. In the Moslem Paradise a man with one leg is not sought after by the houris. I am your convert."

"Well," said Kettle judicially, "you're not a very promising specimen, but you are the only one I have gathered in all Morocco, so far, and so I must make the best of you. I'll attend to the rest of your spiritual needs later on. For the present I must go outside the walls and talk to my friends." He sighed rather sadly. "It will be pretty bad to have to tell them that I shall never kick any one with my right leg again."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.