RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Captain Kettle, K.C.B., 1903,

with "The Command Of The Sea"

"THE TROUBLE, you see," said Mr. McTodd, "is coals. That argan oil they've sent off is too light for cylinder lubrication, as I've said, but now you tell me there's a pinch, Captain, I think I can manage by mixing it with what I have left. But the coal question's a fair knock-out. The bunkers are nearly swept; it would be all I could do to steam her to the Grand Canary Coaling Company's transporters at Las Palmas, and that's the nearest for rebunkering; and if you stay on here for any more naval manoeuvres off this South Morocco coast, it will simply mean putting sail on her again, and blowing to the Islands down the Northeast trades. I don't know whether you like steamer sailing, Skipper, but it's too slow for me."

"I've had quite enough of sailing this old Frying-pan already," said Captain Kettle. "But if we don't stay, the Sultan's steamer will come in and blow Casadir into brickbats. She's got a long gun, it seems."

"Looks as if we were in a regular hat," coughed Fenner.

The engineer stepped out of the shabby charthouse, and stared across the water at the white town of Casadir on its conical hill, and at the great mountains beyond, with their patches of timber. He waved a black-nailed hand toward them. "I could burn wood at a pinch. Our furnaces here are no' adapted for it, like they are in the Mississippi trade, and Mobile, and those places, but you say it's a pinch, Skipper, and I've had unwonted civilities from ye o' late, and I'm anxious to oblige."

"Wood?" said the little sailor bitterly. "You might as well ask for best Welsh steam coal at once. There are 30,000 of the Sultan's troops between Casadir and those forests, and although they don't show from here, we'd soon have their bullets singing among any wood-cutting party we sent ashore."

"Weel," said McTodd thoughtfully, "I never found a few bullets flickering about do me any harm. I'm a man o' property now; I'm a man so enormously rich that I could rebuild the kirk in Ballindrochater, which my father so long ornamented with his ministry, without feeling it; but still in spite of that I'm keen not to miss this offer of the Sheik Bergash's. Man, think of it! I'm worth now all o' twenty-five hundred pound, besides what I have settled on my mither from an adventure or two in the Arctic."

"Yes," said Kettle, with a sigh. "We've been pulling it in, all of us. I'm ready to pay off that mortgage on my farm now, and get my eldest daughter taught the harmonium by the best professor in Skipton, and have money in the bank besides. That is, when the money's got home. At present you must recollect the most of it is here on the ship in hard gold louis."

"It's the way with us millionaires like it is with the others of the breed; we're just bitin' to get more. Man, Kettle, but money's an awful responsibility."

"Also, I don't want the Sheik of Casadir to have his end knocked in. That man got his tail up against the Sultan of Morocco, and he told me why, and I respect his reasons, and want to see him through with his trouble if it can be managed. I have seen," the little man added simply, "trouble myself, and know what it means."

"I suppose it amounts to piracy," said Fenner, "if we whack into the Sultan's ship as things now stand?"

"It does," said Kettle, "but notwithstanding, if I was alone I should risk it. Down here in South Morocco we are a long distance from international law courts, and there are ways," he added grimly, "of keeping people from talking. But there's you to be considered. I'm not going to drag you with your bad lung into complications like these."

"I wish," said Fenner testily, "you'd leave my lung alone, or at any rate, look at it the right way. Ordinary men can take things as they come; I want to pack the experience of a lifetime into about two years, see? Also, I particularly want to save Casadir from that blackguard Sultan, and, moreover, to make Casadir exceedingly grateful to its salvors."

"Oh," said Kettle, "they'll give us gratitude enough, if that tickles you. They'll kill sheep for us, and half choke us with perfumes, and then show us a powder-play to finish up."

"I want something much more prosaic than that," coughed Fenner. "I want a trading concession. Casadir is the natural outlet of the Sus country at the back there, and, thanks to the paternal rule of the Sultan, the Sus trade has been as nearly strangled as it could be. There's not a single blessed port or exit anywhere. Make one, and you'll have oil, almonds, gum, barley, wheat, maize, hides, gold, metals, and ten other things pouring down to the coast as fast as you can ship them. The country's as rich as blazes; it only wants a chance."

"Well," said Kettle impatiently, "everybody knows that, and so's the moon rich, if what I read on that Chest Reviver patent medicine circular of yours the other day is true. The only trouble is, we've just as much likelihood of doing trade with one as with the other."

"The moon I'll give you, but I want to have a hard try for Casadir."

"The moon?" said McTodd with a puzzled look, "I do not see how you could possibly get anything from the moon. Ye must know by the latest astronomical-"

"Oh, dry up," said the passenger. "Look here, Skipper, I want to know what's wrong with the Casadir scheme. The Sultan will object, and I'm calculating on war with the Sultan. That we've got already, and are prepared for, and presently we'll lick him off the face of the local land and water. But who else will interfere?"

"The British Government for one."

Fenner's keen, haggard face showed plain surprise. "Do you really mean that?"

The grim head nodded assent.

"But what's the game?"

"Ah, now you're asking me a prize conundrum, that's quite beyond me. But I can give you a few plain facts about the British Government if you care to listen."

"Go ahead."

"To begin with, the Sultan of Morocco is a rather bad egg, and they know it. He'll do nothing for his country, and does his best to prevent anybody else doing anything, and they know that, too. The Germans and the French are pressing in and getting all the trade (that used to be ours), and all the influence (which we used to have), and if our Government don't know that as well, it isn't for want of telling. But will they help a Britisher to get a finger in the pie? Not they. More than that, if they catch him trying, they twist his tail. They're what McTodd here calls a humorous lot."

"But what's the game?"

"I don't know. I've often occupied myself by trying to wonder if they knew themselves. But," the little man added with a sigh, "they are too deep for me. As a shipmaster I've used the seas for a considerable number of years now, and the British Government have sat down and spent a regular amount of hours each week in giving me annoyance. They're a rum lot."

Fenner brought a lean fist down hard on to the end of the settee. "It's the most amazing thing in the world. Here's Britain with an enormous empire over seas, and it's all been got in spite of her Governments. Clive, Hastings, Cromer, Rhodes, and the rest, they've all been fought against most bitterly by the very people they were trying to serve. Well, I suppose it's that which gives the final relish to the occupation, and so produces the men who carry it out. The other nations would be only too pleased to help their chaps if they would get them new kingdoms, but no men come forward. Our dear folks at home oppose, thwart, blackguard, imprison, and do everything they can to make the game awkward, and so there are plenty of us ambitious fools who want to play it, out of sheer delight at its hardness."

"I've read yon book of Jules V erne's about a voyage to the moon," said McTodd, "and it's scientifically incorrect. I'm no' decided myself just at present what means ye'd have to employ to get there."

"Let me understand this," said Kettle, leaning forward. "I've heard a lot of these 'schemes' of yours, boy, but I haven't understood much about them, so far. Isn't this your own row you're hoeing?"

Fenner laughed and flushed. "Isn't it very simple to understand? I'm full of energy and ambition, and very empty of health. I'm a wretched consumptive, and so I can't look forward to founding a family, which is what nearly all other ambitious men do when they start on their ambitions. I'm the one in the million, and my fad goes in another direction. I've got the land-hunger on me, the national landhunger, and I'm going to gratify it."

"But, boy, you're a pauper. You told me so yourself."

"Oh, ways and means remain to be found. Incidentally I shall have to get rich; first you must have tons of money if you want the power to work this game; and because I have very little time, I've got to get rich quick. If I'd got a long life ahead of me, for instance, I should say let this Casadir scheme slide, and look out for a more favourable opening. Want of coals is the thing that proposes to trip us up just now, I gather."

The sailor pulled angrily at his red torpedo beard. "That's the trouble, boy, and I don't see any way of getting to windward of it."

"And the Sultan steamer will have lots?"

"Sure to have as much as she can stagger under. She'll have put across to Gibraltar for bunkers before she started down here. That's her way."

"Nothing like being regular, so that people may know your habits. The plain thing to do then is to get the Sultan's coals. That bags two birds with one stone: it leaves him helpless, and gives us plenty more string; I know it's a large order, but—"

"By James!" rapped Kettle, "we'll do it. As for the how, that will bear a bit of thinking out. She's got a big gun that will shoot a long distance. Our big gun, thanks to Solomon's economies, is a second- hand relic, with the threads of the breechblock halt stripped, and the rifling all rusted away. The odds are it would burst in the firing, and it certainly wouldn't throw to any useful distance. It seems to me a case for strategy."

"But look here," said McTodd. "With regard to the moon, I've been thinking-"

"Oh, blister the moon!" said Fenner. "Let's get a boat into the water, Skipper, and nip off ashore, and fix things up with the Sheik. Hurry will be very useful just now."

"You're right," said Kettle. "We've got to get a move on us if we're going to come out top side. Mac, I leave you in charge of the ship, and I'll tell that putty-headed mate he's to take his orders from you. If the Sultan's ship gets here while I'm away, and looks ugly, heave up, and steam off down coast. We'll join you somehow."

"Man, but running away's a thing I don't like. I thought the arrangement was we were to get hold of this Sultan's ship and take the coal from her."

"Kindly carry out the orders that are given you," snapped Kettle. "You can't argue with a ship that carries a gun which will shoot four miles, and which she will use as soon as she's within range. Can't you remember that Casadir's a closed port, and that our being here is bang against treaties and laws and everything? And there's another thing. Just you pull yourself together and keep off the drink. There's only one bottle of whiskey left, and I want to keep that for a special celebration."

"My good Captain Kettle," said the engineer solemnly, "the responsibility of this great fortune I'm possessed of has changed me to a different man. Besides, what's the use of one single bottle for a man with my coefficient of absorption to sit down to start a bout at?"

A boat presently left the Frying-pan (as the steamer had now come to be firmly nicknamed) and pulled off parallel to a beach that was littered with a noisy surf. The northeast trade was blowing strongly and the swell ran high, and Kettle passed a malediction on the sand which would be filling the atmosphere ashore. "It's disagreeable for any one," said he, "but with your sick lungs, boy, it's more than dangerous. I shall leave you in the boat and go up and do my bit of business with old Hadj Mohammed, and then come back for you. You won't have so much sand blown down your throat if you stay by the boat."

"Don't keep harping on my decimal of a lung. To begin with it's bad taste, and to go on with it tends to make me hurry things unduly."

"But, my good boy-"

"Now, Skipper, kindly dry up."

The little sailor sighed, but for a wonder did not persist. This tall wreck of a young man, with his hollow cheeks and great beak of a nose, had come strangely to dominate him. At first it was Fenner's bodily weakness that had appealed to him; but then the glamour of the man's magnificent ambitions began to fascinate him; and presently here was Captain Kettle, a fellow with an overweening love of power himself, and one who never took an order civilly, allowing himself to be quietly ordered about.

The beach offered no chance of landing that day, so Kettle took his boat through the noisy spouting flurry of broken water which marked the river bar to the southward, and for a short time came within range of the besiegers' lines, from which the Sultan's troops promptly favoured them with an erratic fire. The oarsmen of his boat said they had not been hired to be shot at, and wished to return. But the application of the little sailor's venomous tongue, and the threat of a clubbing from the oaken tiller, reduced them very quickly to sullen obedience, and presently a bluff gave them shelter from the gun- fire.

Beyond a half mile of flat the town reared up on its hill, deliciously white under the sunshine, graceful with minarets, and delicately pleasing to the eye. The great encircling wall below dished it up with all possible neatness. Kettle gazed upon it appreciatively.

"Yes," said he; "forget the smells inside those walls, and the garbage in the streets, and you could write poetry about Casadir that even a fat-headed magazine editor could see the beauty of."

"Blister the poetry!" said Fenner irritably. "Tell me how we are going to get there. The water port's shut, but I suppose if we went up and knocked they'd open it. If we could run, it would be all right. Those marksmen over there have got muzzle loaders, and don't loose off at moving targets. But I can't run—at least not half a mile. And if we walk, we shall be jugged for an absolute certainty."

"I don't think it, and anyway, as I shall walk on the weather side, you'll have the benefit of my doubt."

"Fat lot of good that would be to me. Do you think a man of my length could get under the lee of a shrimp like you?"

Kettle turned on his friend with a sudden acidity.

"Now, look here, my lad, you make one more remark upon my personal appearance, and you'll feel the heft of my fist, lungs or no lungs."

"I beg your pardon. I'd forgotten it was a sore subject, and I really did not mean to rile you. But a fix like this is maddening. I can't afford to wait, because there is so little time for things; I don't want to get killed, because there are so many things to do; and here we are at a rather bad kind of deadlock. Isn't there another way of climbing into this blighted town? Can't we get back over the bar again to sea, and have a try at running through the surf for the old landing place?"

"Not a cat-in-oven chance—what's that you're doing now?"

"Waving to those jokers on the walls. It's too far off to see if there's any one we know, but they'll guess who we are right enough, and I don't see what's wrong with their hammering out the fact that we're here for business, and not merely to pay a polite call. By Allah, they've tumbled! Look there!"

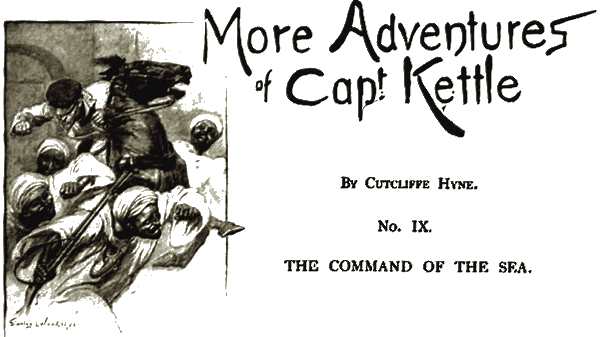

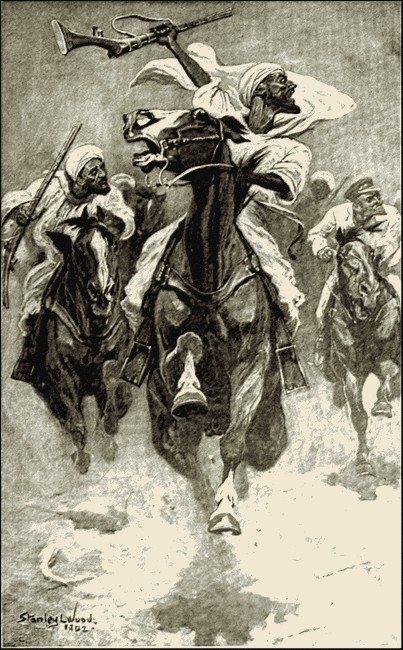

Of a sudden the valves of the water port were flung open, and the archway emitted a gush of horse- men. With much crackling of guns these galloped across the plain and brought up momentarily on the river bank with a swirl of draperies. They had with them two led horses, and ten seconds later these were mounted by riders, and the sortie returned through a whistling hailstorm of home-made slugs. Two horses dropped and their riders jumped clear, and ran on, each clutching a friend's stirrup-leather, and three horses came in riderless.

The sortie returned through a whistling

hailstorm of home-made slugs.

"It was written," said the captain of the water port, as he let them in, and the great doors swung shut again, "it was written that three fortunates who rode out from here ten minutes ago, unsuspicious of fate, should now be smiling on their brides in Paradise. Here you, take Reis Kettle and the man with the great nose (on both of whom be much honour) to the carpet of the Sheik Bergash, and do you other dregs of the sok refrain from crowding these truly great men."

Their progress thence to the Sheik's house would have been an unbroken ovation, but for Kettle's dislike for one particular catch-word. The crowd, with the desperation of a long-besieged people, leapt at any chance of succour, wove a thousand stories of relief from the return of these two Europeans, and shouted their encouragements with Oriental effusiveness and imagery.

They clapped on Fenner a catch name and attributes from his big nose which would probably have made him blush if he could have understood the flowery Arabic, though as it was he rode on only placidly tickled. But Kettle they unfortunately acclaimed as el reis seria—the little captain—and let loose upon themselves a squall of that mariner's bad temper.

The sailor was acutely sensitive on the subject of his inches, and already that hot morning Fenner had touched him on this sore spot. For the united dregs of the Casadir bazaars and soks to take up the cry behind him was too much. Again and again he spurred his horse into the mobs, trampling on slippered feet, and (worst insult he could think of) knocking off turbans and slapping the shaven heads beneath them.

At the first moment the pair were within a hair's breadth of annihilation. Life is always perilously cheap in those towns of Southern Morocco, and in Casadir just then, after a year's siege and its accompanying atrocities, the value of a life had come down almost to the vanishing point. The Moor is a man with a very nice and touchy honor, and the cry arose of "Infidel'! Infidel! Kill! Kill!"

But on one of the bald pates so rudely exposed, some wag of the sok suddenly discovered the clawings of female nails, and in that poetical Arabic, which clothes all these things so delicately, yelled out some ribald reference to domestic infelicity. The Moor has also among his many other attributes a quaint and frisky humour. With laughter twisting one side of the mouth, and murder curling on the other, the crowd swayed for a moment, and then took the brighter view.

"El reis seria," they yelled, "seria! seria!-" and when again and again Kettle charged viciously among them, it was with laughter that they warded off his buffets, not with the up cut they could so neatly deliver with the curved dagger.

At length two heated Europeans, one much shaken with laughter, and the other with indignation, were admitted to the great house of the Governor, and after walking through courtyards, and gardens, and many corridors, were ushered to the place where the great man himself sat smoking keef on his carpet.

"Slamma." said Kettle. "I have never been so much insulted in my life, Hadj Mohammed. Every son of a dog in your town seemed to think he'd a right to yap at me as I rode up."

"Slamma alikum," said the Sheik Hadj Mohammed Bergash. He took one of the long five-foot guns from his guard, withdrew the ramrod, and handed this to Kettle. "Reis Keetle, an insult to you touches very nearly myself. To-morrow I will send to you the tongues of these talkers, who are, as you truly say, sons of dogs. If the tongues when threaded on that ramrod do not fill it, with a dishful over, I give you leave to call me a niggard, and further permission to come here and tear out my tongue also."

Captain Kettle stirred uneasily in his seat. "I didn't want you to rub it in quite as hard as that," he said rather haltingly, but the Sheik put away his objections with a wave of his small brown hand. "You may consider the thing as done," said he. "I wish I could do more to show my consideration for you. To say the truth, we men are cheap here in Casadir just now, and if the Sultan's troops break in, which they assuredly must when the ship comes with her gun to help the army below there, why then it will matter little when all heads are cut off whether or not there are tongues left to wag in them."

"Don't apologize," said Kettle pleasantly. "You've told me something I very much wished to know. You've owned up to being desperate, and therefore you won't grudge me a lot of men to help me carry out a scheme Mr. Fenner and I have set our hearts on. We're going to mop up that Sultan's steamer for you when she shows herself here."

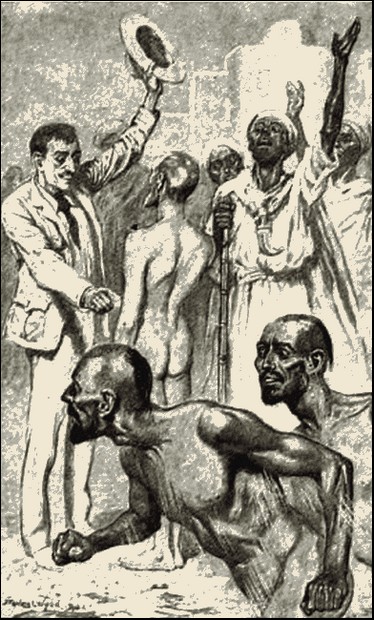

"You may have half the men in the place to use if you need them, and if all are lost it cannot be helped. There is no other hope to save the rest—and our women, and the children, who will otherwise be taken as slaves. Slarmma, Reis Keetle, I kiss your hand. You are a brave and generous man. Does his Excellency Fenner take command with you?"

"Here, I say, Skipper," Fenner interrupted, "just translate a bit. I hear the pair of you using my name, but I can only pick up one word in ten from the rest of your Arabic. What's this about half the men in Casadir?"

"I reckon it will take that amount to mop up the Sultan's steamer. Don't you make any error, boy. It's going to be an uncommon tough job."

"And what's the pay, what's the reward?"

"I haven't bargained for that yet."

"Very unbusinesslike of you, then. Tell him that if we clear away this steamer for him that the investing army at the inland side of the town will retire from lack of supplies, and so Casadir will be practically an open port, and he himself will be an independent chief, and clear, at any rate for the time being, of that feeble scoundrel of a Sultan. Rub it into him that although this is what he's been aiming at all along, he hasn't been able to get it without our help, and then just tell him that we want our fee."

"Oh, you've settled in your mind, then, what it's to be?"

"What you and I want—and are going to have—is a concession of the whole of the shipping from Casadir after trade is opened again."

"But what's the use of getting him to agree to it? He'd give us his promise fast enough, but, even if we had it all written out, and the names signed to it across a sixpenny charter party stamp, it wouldn't be worth the paper it's written on if he chose to show slippery. You can't pin these sort of foreigners, boy, with anything short of a gun. The only way to boss this town is to turn out Hadj Mohammed altogether when we've mopped up the Sultan's army, and for me to be Sheik in his place. Then anything that I say is concessed will remain so."

"It will very probably come to that, or something like it. But, in the meanwhile, you get the agreement down in black and white, Skipper, and then afterward when the Powers begin to ask questions—which they will—we shall have something to wave in their faces."

"Oh, very well, boy!" said Kettle, "anything to oblige," and put the condition before the Sheik, by whom it was promptly accepted. Indeed, the poor man was in so desperate a plight just then that he had no alternative; and, besides, with repudiation always at the back of his mind, it really seemed to him to make very little alteration in the odds whether he signed ten such documents.

The Sheik Bergash in his then condition has struck many of his observers as a figure of pathos. He was a man of much capacity on the lower scale, and chance, mistaking him for something bigger, had pitchforked him into a position which a Napoleon might well have shirked.

In one of the most barbarous and powerful empires of the modern world, he was set up, with ridiculously small resources, as the head of a body of seceding rebels. If, as seemed probable, his amiable sovereign put him to rout, a comprehensive massacre and the sowing with salt of all his desolated territory would be prompt award. And if, on the other hand, he was lucky enough to maintain a sturdy independence, promptly there would descend upon him the net of European diplomacy, and in the meshes of that he would merely struggle himself into exhaustion.

But Mohammed Bergash did not look so far ahead as this. Let the Sultan's army be cleared away, and the Sultan's ship be sunk, and he saw only prosperity.

Captain Kettle, too, was more man of action than far-seeing diplomatist. The new four-point-seven gun on the Sultan's steamer seemed to him the one and only key to the situation, and once it was taken, at whatever expense to the attacking force, then the future would run on easy machinery.

But Martin Fenner had the power to look upon things more with a statesman's eye. As he sat there in that heated room, he remembered his previous gleanings on the subject, and put these together.

He remembered that the Great Powers of Europe, always as jealous as cats of one another, looked upon Morocco as the next slice of Africa to go to one or another of them in the general scramble. He recalled that each was firmly determined to make war on any other which did the actual grabbing; and so as a result they all sat around and watched the Empire crumble; but at the same time all showed nervousness and suspicion if the crumbling process in any one district took place with any unseemly rapidity.

It was with this charming country, then, that Captain Kettle still kept his fortunes, though he might well have retreated from it with a decent competence. But there was that lively condition which he always spoke of as "trouble" in the air, and this was a state of things which habit had made to him an almost necessary ingredient of his existence.

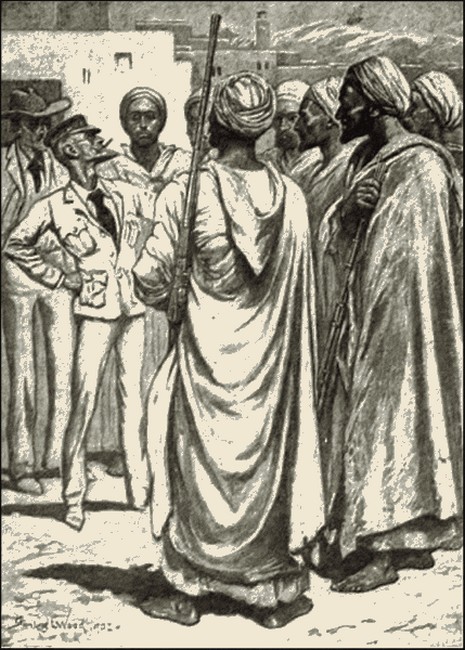

The white sunshine of the streets outside the Governor's house was cooled by a strong trade, which blew with it a burden of sand, that irritated Fenner's throat, and made him cough and swear. But they had small enough leisure to give attention to these minor discomforts. In the space of the next few hours it was more than probable that one or both of them would be killed, and in the meanwhile there was abundant necessity to make all In one of the open market spaces of the town men were collected by criers, ranged into line, and told that presently when night came they would be formed into a forlorn hope to give their lives for the safety of the town.

Most of them heard the news without emotion; a few, indeed, showed placid satisfaction; not one offered an objection.

Most of them heard the news without emotion.

"By Jove, but they're a plucky lot!" said Fenner admiringly.

Captain Kettle's brow darkened.

"They think, according to their misguided religion, they're booked for Paradise, but according to my theology, they'll be badly surprised at the climate they do bring up in on the other side. If I'd time, I should much like to convert some of them to the true fold before they start."

"Wouldn't it be better if we could keep them this side of the Styx a bit longer? They're fine men, and it seems such a pity to waste them. Besides, once we've got Casadir in running order again we shall want all the men we can get."

"It can't be helped. When the Sultan's boat comes and has brought up to her anchor, we must just pack men into all the kherbs they've got down there in the river—lighters, that is, you know—pull out across the bar, and take that steamer with our hands."

"I don't see that such a scheme would have a chance."

"I do," snapped Kettle. "I've tried the same sort of thing before, and brought it off all right. It's only a question of having enough boats and enough men. They can't sink all before you come up alongside."

"H'm," said Fenner thoughtfully. "D'ye think that courier from Mogador that the Sheik's fellows grabbed with the message to the Sultan's army here was genuine?"

"He got killed fast enough, and as for the chit he carried, I had that read out to me, and it sounded all right. Their steamboat put into Mogador to mend up machinery. They'd broken down three times in the engine-room since leaving Tangier, had lost one anchor and fifty fathoms of chain, but expected to get on here by the late afternoon of to-day. All those breakdowns sound too natural for a faked message. Of course, the clumsy fools may pile her up between Mogador and here, but that's hardly an event for us to reckon on."

"Not a bit. No, Skipper, she'll come, and we'll make use of her. That loss of one anchor simplifies things very much. We'll grab her for the new kingdom of Casadir, and with that four-point-seven gun we'll hold command of the local seas. Now just put your ear close. I don't want the whole world here to listen."

Martin Fenner whispered twenty words, and then Captain Kettle stepped back and looked at him admiringly. "Well, of all the blasted impudence!" he said.

"I believe it could be carried through."

"I'll do it for you on one condition. You're not to try and come too. It would be just suicide for you with your sore lung to risk the exposure."

"I can't come possibly," said Fenner, "I can't swim a stroke."

Then Kettle turned to the men drawn up in the square, and in his broken Arabic informed them that before their forlorn hope set off, a still more forlorn hope would precede them, and for this he asked for six volunteers who were to be swimmers. The whole five hundred stepped forward, and he picked his half dozen. Finding, however, on cross-examination that none of these could swim a yard, he beat them over the head for deceiving him, and made a fresh selection. Then he told the rest that there was no chance of Paradise for them that evening, and that on another occasion, when he had a little more time, he would give them a more accurate description of their destination. He added that they had his permission to depart.

That night Martin Fenner sat on a housetop in Casadir, and coughed, and watched, and sweated with weakness and anxiety. Over the sea below the town was spread a black curtain of night, unbroken by either moon or star—vast, empty, achingly untenanted. And yet somewhere in that void before him was Kettle and his six men in desperate ambush.

Into this blackness about midnight there slid the lights of a steamboat, coming slowly in from the north. Presently the steamboat stopped, but the sounds of her anchoring did not reach him. The roar of the beach below and the whistle of the trade drowned all lesser noises. Then the blackness snapped over the steamboat's lights, one by one, till all were eclipsed.

Fenner rubbed his lean hands and tried to think that the watch she kept was slatternly, and waited and waited on through the drearily dragging hours of half the night.

It was not till the dense black of the scene was turning to gray that the hint was given him that Captain Kettle had put his plan into action. The steamer showed in dim outline on a heaving sea, white-crested. From the forepart of her, low down near the water's edge, came a sudden snap of flame, which was gone in a moment. In the growing light men showed on her decks, running about like white-sheeted ghosts, and presently dawn sprang up behind the great crags of the Atlas inland, spread over the sea, and in another minute it was glaring day.

Fenner put a hand over the bridge of his great beak of nose, and peered out at the bright-lit waves. Yes, there were one, two, six, seven dots of heads swimming in hard for the shore. Other eyes saw them at the same time, and from the steamer broke out an ill-aimed crackle of musketry.

The Sultan's steamer was plainly adrift. The flash that had shown through the end of the night was the firing of a cake of gun-cotton which had cut through her riding cable. Plainly also she was out of command. Captain Kettle and his men had contrived to swim off the heavy chain with its floats all right, and had wound it round propeller blades and rudder, and had shackled the ends, and made the Sultan's steamer into a helpless hulk. Her people had tried to get her under weigh. Steam shot from her escapes, and oozed from the engine-room skylight. Evidently also they had achieved another of their breakdowns.

Then boom went the four-point-seven gun on her main deck, and from somewhere above him in the town came the crash of masonry.

The steamer drifted in rapidly toward the surf under the push of the brisk trade wind, and seeing destruction before her, fired with vicious energy. Out of thirty-four shots she made six hits, and did an inconsiderable amount of damage, and then she took the ground, and the men of Casadir went down to the brink of the surf to pay what attention was due to her people.

But half an hour before this final event took place, the sea decanted on to the beach Captain Owen Kettle and his two remaining men, and him Fenner greeted as a man who has looked on victory from afar greets the actual conqueror.

The sea decanted on to the beach Captain

Owen Kettle and his two remaining men.

"Skipper," he said earnestly, "I believe you're one of the greatest Englishmen of the day."

"I'm Welsh by birth all the same, if you don't mind, boy, though most people forget it. Here, for James' sake let me find my clothes. A man can't keep his respect unless he's properly dressed. Then we'll take a boat to the Frying-pan and see about hauling this other packet off the ground when the Sheik's men have done handling her people."

They did this, and were met at the head of the ladder by a very smiling McTodd. "Man, Fenner," said he, "I see now what ye meant by yon reference to the moon. With regard to a journey to it, my father, who was minister at Ballindrochater, took up mathematics at Aberdeen University before he studied theology, and I mind in one of his sermons about the moon-"

"Oh, to blazes with the moon!" said Kettle. "Come into the chart-house and let's split that last bottle of whiskey. When that's down, we shall have a sweet job in pulling the other half of the Casadir navy off the ground there. We shall want both steamboats if we're to keep command of the sea round here."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.