RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Captain Kettle, K.C.B., 1903,

with "A Cup Of Tea"

The Sheik

"EL reis seria," the door guard announced first of all, but when Kettle turned on him with a furious prohibition against ever again describing him as "the little captain," the man bawled out "El Reis Keetle" as a further introduction. He did not seem to consider the pink-cheeked, panting Fenner worthy of any comment whatever.

The Sheik Hadj Mohammed Bergash, seated on the Sus mat at the further end of the room, welcomed the pair with unruffled composure, and bowed his head and said "Slamma alikum" with fine dignity.

"Slamma," said Kettle, and went up and seated himself cross-legged on the mat. He beckoned Fenner to his side, and that young man doubled himself up awkwardly, and then was half-strangled by a fit of coughing. "I am very pleased to make your acquaintance at last, Hadj Mohammed."

The Sheik Bergash touched palms with Kettle's, and kissed his own. "May your enemies die painfully, and your family increase," said he in flowery Arabic.

"I'd like you to tone down those good wishes just a trifle," said the little sailor. "The present family's about all I can support. More of them would make me a bit too active. But while we are passing compliments, I should like to say that this hilltop town of yours is a mighty strong place, but riding up here from the beach is one of the hottest jobs I've struck for many a long day. I'm not much of a jockey any time, perhaps, but that red stallion you sent me down was a fair circus. He danced up nine-tenths of the way on his hind legs. As a consequence I've got a good four-dollar thirst on me."

"I do not quite understand."

"Well, Sheik, if you aren't T.T., I guess now's the exact moment to bring out the whiskey and soda. Let me introduce my young friend, Mr. Martin Fenner. He's thirsty, too."

"I have only the drinks allowed by my religion," said the Sheik, and clapped his hands and ordered them.

"Oh, bad luck," coughed Fenner, and Kettle clicked a dry mouth. "Now, I made sure, Hadj Mohammed, that a Moor who'd the taste you have for steamers and Lee-Metford rifles would have been civilized up to gaiour drinks as well. But you say you aren't, and I don't know that I like you any the worse for it. You stick solid on your own religion, and I'd rather deal with a hard-shell Mohammedan than with a man who's half that and half nothing."

The Sheik bowed gravely.

"Besides," Kettle went on, "Mr. Fenner here wants to learn all about Morocco, and he can't do better than begin on a tumbler of hot green tea, with a sprig of mint in it, and as much sugar as it will dissolve. I'm glad to see the trade isn't blowing you a sandstorm here. We'd very strong trades as we steamed down coast, and off Mogador the sand was coming aboard as thick as a channel fog, and filling the very marrow in your bones with grit. Mr. Fenner here is a bit touched in the lung, and I thought the dust would have killed him.... Here's luck, Hadj Mohammed—I mean, slamma. It's many a long year since I drank green tea as sweet as this."

"Slamma alikum. This town, the other towns, the country near, the tribes of the Atlas, and Sus beyond, will regard you as their father, Reis Keetle. I am their spokesman to say it."

"I'm sure that's very kind of you, and gratifying to me. Perhaps, as we are on such friendly terms, you won't think it indelicate of me to remind you that there's a little bill outstanding between us."

"Oh, that!"—Sheik Bergash waved a small muscular hand. "It is not for us chiefs to talk of these mean matters of commerce. Solomon, my agent in Jebel-al-Tarik, will settle all these things with your agent."

"Not being in a position to keep a large staff just now," said the little sailor drily, "I am acting as my own agent. As for Solomon, he's got the usual Gibraltar Scorpion's failing. He's very slippery. So I just brought him along on my steamboat, and for reasons of safety I've locked him up in his room, and he's there this minute. Funny thing about Solomon is, he's complaining that you have landed him in for making a bargain which he now finds he hasn't the means of carrying out."

"I do not completely understand. You speak too tangled for me," said the Sheik.

"I don't completely understand. You speak

too tangled for me," said the Sheik..

"Well, I know my Arabic isn't yours. Mine's East-country Arabic, and not Moorish; and as for Berber, which is, I suppose, your other tongue, I don't speak it at all. However, I'll try to explain more clearly. That vessel that's lying at anchor off your beach belonged to self and partners. She was surrendered to us by some measly underwriters instead of lawful salvage price. We had her there in Gibraltar Bay open to offers, and your particular Scorpion came along. I'll admit she was not a packet for everybody's money; fire had burned most everything in her that would burn; and, besides, she was a good deal buckled, and in most ways had lost her looks. But then the price was low to correspond, and I guess it was the price that brought Solomon along like a rat after a well-kept cheese."

"Solomon knew how much we could afford. He understands my affairs."

"He may think he did; they're a slippery crew, these Scorpions, and I never trust them overmuch, Sheik. But just now Solomon says he's clean fogged over your and his finance, and for once, in a way, I believe he's speaking the truth. We put in at Mogador, you know, for him to consult with some of his co-religionists, and he came out waving arms of despair like a windmill."

Hadj Mohammed Bergash threw out an elegant hand. "By Allah's mercy I am not a Jehudi, and so do not understand business. I am a Moor, and a true believer. You have brought me the rifles and the repeating cannon? You have brought also the heavy cannon to defend your steamer from the Sultan's steamers when they come to interrupt your trading?"

"There were certain cases," said Kettle very drily, "in number three hold, which were entered in the manifest as machinery, that might contain rifles and a machine gun or two. I didn't break them open to make sure. There was also a case marked Grand Piano in number two hold which might very possibly be convertible into a big gun. Indeed, your Mr. Solomon was very anxious to have them lightered off here first thing."

"But they have not come!" said the Moor, wrying his face.

"You never spoke squarer truth. You see, there was that trifle of a balance between us, and I wanted that settled first."

"Tut, tut, tut. They must be brought ashore at once. The machine guns and rifles may be wanted any minute to defend the town. The Sultan's army is all round us, and each time they have attacked, our defence has been weaker. I tell you, Reis Keetle, my weapons must be brought ashore at once."

Captain Kettle bristled. "Come, now, Hadj Mohammed, don't you try that tone with me. I'm a man (as you've seen) that's all for civility if it can be managed; but if you choose to show ugly, there's not a man more capable of handling you between here and somewhere hot."

The Sheik's thin face darkened.

"Do you think, Reis, that I am what I am without having learned how to take care of myself? If you do not choose to give orders to have the guns brought off, they must be fetched without. I shall give orders for a kherb to put off from the water port at once."

"You may send not only one lighter, but ten, if you choose," said Kettle contemptuously, "but you'll get nothing you want out of my ship without my written order. I suppose you've had word brought off that the mate's soft; and that's right, he is. But the ship's not left in charge of Mr. Mate. That packet, till I get back to her, is in the care of my chief engineer, a Mr. McTodd, who's also part owner till you've finished buying us out: and the Moors that get foul of McTodd during my absence will be damaged Moors. I believe the creature to be a poor engineer, and he's certainly unqualified; in religious matters he tends toward I don't know what damnable Scotch heresies; but as a fighter—well, there are no flies on McTodd when it comes to a scrap. I've seen him at it a score of times now, and I may even go so far as to own that I have had a turn-up with him more than once myself. You see that cut that's just healing on my cheekbone? Well, that's McTodd's signature, and let me tell you, Sheik, there are many a score of men who would give an ear and two fingers to be able to boast that they had written as much."

"Half a minute," broke in Fenner, "and don't look round. I don't understand Arabic, but from the tone of your talk, and the ugly look that's growing round his Excellency's mouth, I gather that you've been pulling his gallant leg."

"We don't seem to agree just yet."

"Well, he's a primitive man, and he evidently sees much to approve of in primitive ways. Skipper, I say, don't turn round. There are four rifle barrels covering us, and if you move too suddenly they may go off. I caught sight of them just now when I reached down for my hanky. They're behind that green lattice-work window at the back of you, in the dark. Somebody opened a door there just for a second, and let the light in, and that's when I got my glimpse."

"You frightened?"

"I'll take my cue from you," coughed Fenner. "When you begin to shiver and shake, I'll consider about doing the same. No, I shouldn't say I'm scared, merely a bit thrilly, you know. Gives you heaps of pluck, of a kind, only to have one lung."

"What are you talking about?" asked Hadj Mohammed suspiciously. He pressed a shapely, thin hand against his brow, as though to sharpen his sight.

Captain Kettle waved an airy cigar. "Mr. Fenner was merely letting me know that you had followed out your dog's instinct, and were preparing to have us murdered while we were partaking of your hospitality. Go ahead, Sheik, and tell your chaps to loose off. You won't get your guns, but you'll gain a distinguished reputation. Even the kids will point at your beard, and say, 'There goes the coward who was so frightened of two Englishmen that he even had to smudge his hospitality before he dared to murder them!"

Sheik Bergash let off a long sentence in explosive Arabic, and finally came down to a mere calm explanation. "The men are my usual guard. We live here in troublous times, just now, Reis Keetle, and a guard is necessary. But if they make you frightened they shall be removed."

"Oh, not at all," said the little sailor, with acid politeness. "Don't let me interfere with any of your tribal customs. We each have our own little ways. For instance, of course, I have my own gun with me. It's in the side pocket of my coat, as you can see by the outline when I press it sideways. I hate to carry a pistol there, because if you are obliged to shoot, it sets fire to your clothes and makes a nasty untidy mess. But there are occasions when you haven't time to pull your fire-iron out of the sly pocket of your pants, and I guessed that one of them might occur up here in this whitewashed sitting-room of yours, Hadj Mohammed. As a consequence, I've been quite ready all the time we've been squatting here to drill you through the bowels at less than half a second's warning. I suppose you took me for something different, eh?"

"Allah is very great," said the Sheik, and gave orders for his men behind the green lattice to retire. "Reis Keetle, you and I will call a truce for the time being." Again he wryed his face, and was obviously in pain. He loaded a thimble-sized pipe with keef, and took up its contents in three deep puffs of smoke. "I am not well, and men such as you and I cannot talk and treat at an even balance with fire and throbbings at work among their interiors. In the evening I will have a cous cousoo made, and while we eat that we will come to a settlement. As the hand lifts food to the lips, it sweeps away many disagreements."

"You have my permission to depart," said Captain Kettle quickly. He felt pleased with himself at slipping in this customary phrase before the Sheik could use it. "We'll look in again about supper time. You don't look well, Hadj Mohammed, and that's a medical fact. You've probably eaten something that's disagreed with you. Best thing you can do is to turn in on your mat and sleep it off. Mr. Fenner and I will amuse ourselves by looking round the town, if the dust isn't too much for his cough."

Captain Kettle's meeting with the consumptive Fenner had been curious, and at first sight they had by no means taken to one another. His vessel lay in Gibraltar Bay, which does not always contain the smoothest water in the world, and on that particular morning, what with tide, swell, southwesterly squalls, and one thing and another, it was more than usually lively. He had ordered steam for 6 a. m., and here it was 9.30, and still the agent, Solomon, had not come off with final instructions, in spite of many urgent messages and signals. Captain Kettle had several times consigned the Rock and Rock Scorpions to a climate even hotter than their own highest recorded summer temperature, and he bit off the end of his eighth cigar with an energy that was savage.

But as he raised his cupped hands to light a match, he saw a boat coming from the direction of the water-port mole, and heading directly for the ship.

She was a small boat pulled feebly and wetly by two oars, and Kettle cursed Mr. Solomon's economies in not choosing a larger and speedier craft. "But there's one comfort," he grumbled, as he watched the boat tuck her nose into three consecutive seas, "he'll get a jolly good pickling for his pains. What's more, if he doesn't take to baling presently, I should say they'll be swamped before they're alongside."

But the passenger in the stern of the boat made no attempt either to bale or to steer; sat limp and huddled instead; and crouched incognito under a mackintosh and a hat with a generous brim. On to the foot of the ladder (when they arrived there) this person was pitched by the unceremonious boatmen, who, by way of proving that they had already received payment, rowed off promptly back for the shore. And there he huddled while the steamer rolled into three consecutive swells.

"Drunk or not," commented Kettle from the rail above, "I don't have you drowning off my front doorsteps," and sent down a pair of deckhands, with sharp orders. In the rude clutch of these the caller was dragged up to the deck level, and here displayed, not the well-known lineaments of Mr. Solomon, but the blood-tinged lips and hectic face of an entire stranger.

"Hullo," snapped Kettle; "who in the tropics might you be?"

"Fenner," choked the visitor. "Sorry for this display, but it's seasickness that brought on the haemorrhage again. I heard you were going to the South Morocco coast, and wanted to beat a passage. If only some one here knew a little about doctoring...."

"Eh, what's that?" asked Kettle, stooping down.

"Ignorant looking lot," gasped the visitor, with closed eyes. "What a beastly nuisance; got to peg out now! All those beautiful schemes ahead and nothing done."

"What is it you want to do?"

"Queer gamble, health is," murmured the visitor, and forthwith leaned over into unconsciousness.

"You look pretty sick, and that's a fact," soliloquized Kettle. "You're feeling nervous. You don't seem to think I look much like a doctor, my lad, and other men before you have made that same mistake. If you could hear, I should like to point out to you that there are few people who know more about drugs than I do, and, what's more, I've got a bottle on board that will get to work on your complaint right from the first dose you swallow. It says so on the label. By James, I'll cure you, just to prove to you your blessed mistake. Here, you, take this gentleman up to my room, and tell my steward to get the clothes off him, and rig him in some clean, dry pajamas."

Out of so uncompromising a commencement, then, a friendship sprang up between these two that was very real. Fenner increased in strength and soundness every day, either because of Captain Kettle's patent medicine, or in spite of it, and the shipmaster found in him a companion entirely to his taste.

"I heard of you ashore in Gib.," said Fenner, as soon as he could speak, "and I heard of you before from a fellow called Cortolvin I met at St. Moritz, and you've been the one man I've always wanted to have life enough to meet and to deal with. I've only got schemes. You've got health and vigour. It does me good, even to look at you." Indeed, so thoroughly did the invalid give himself up to that subtle form of flattery, hero worship, that not even the most austere of men could have avoided being gratified.

By the time the steamer had worked her slow way down the Atlantic coast of Morocco to Mogador, Fenner was on his feet again, full of vigour of mind, but weak still in body; and by the time she had brought up to her anchor off the port of Casadir, which the Sultan has so long closed, and the Sheik ashore proposed to open, he was so far recovered, that he was able to go off to the shore in Kettle's company.

"Bit of pretty bad luck finding his Excellency with stomach-ache," said Fenner, as they left the Governor's house. "Speaking as an expert on the matter, a man can't help cantankering when he's feeling sick. My aunt, Skipper, but this place does carry a hairy great stink with it."

"If it were six times as strong, I'd feel happier. It's the smell of the skins they're drying in the streets, and it's skins that ought largely to pay the money that's owing to me and McTodd. But as it is, the sok outside's closed."

"The what's closed?"

"Sok—market outside the walls. The traders from Sus and the country round bring their camel loads there, and the Jews and Moors of Casadir buy. At one time Casadir used to be an open port, but the Sultan found he couldn't collect his customs—the Governor froze on to all the cash, I suppose—and so he closed it, and the stuff had to be carried along on more camels to Mogador for shipment. That didn't suit this town of Casadir, of course. It spelt busting for Casadir. So the Moors here, with Hadj Mohammed at the top of them, got their tails up, scragged the Governor, and sent word to the Sultan of Morocco that his beard was about the most ridiculous piece of asses' hair that ever wagged on a decaying chin. You don't know Arabic, Mr. Fenner, but you can take it from me that for putting real poetry into cast-iron hard language, there's no tongue on earth that can equal it."

Fenner laughed. "Well, I back you for being a good judge of both. Also of fighting. So the Sultan's repartee was to send an army to batter the place down?"

"He sent the army fast enough, but there was no battering. There's no such thing as a wheel road in Morocco, and the bridle tracks are far too bad for artillery. It's as much as you can do to get mules over the bad places. So the army came, living on the country as they marched, and finally got here and sat down in front of the place. You've seen what it is: the cone of a steep hill ringed round half-way down with high, strong walls, and the town built on the apex. It would be a grand mark for long-range artillery, of course, but that's what they haven't got. They've no appetite for storming the place, and there, I don't blame them, either. So they've simply sat down to starve it out, and that's going to be a slow job, too. Hadj Mohammed's no fool. He'd got three years' barley and oil and provision generally in the place before he began commenting on the appearance of the Sultan's beard, so as to give himself time to turn round and make his moves without being forced."

"The Sultan has a navy, though, hasn't he? I had some sort of a rattle-trap belonging to him pointed out to me at Tangier."

"That old tub! Why, she hasn't got a gun mounted. With half a dozen rifles I'd send her steaming away even with our Frying-pan. I told Solomon that when he first approached me about buying our packet for the job. But I did think there was better prospect of our getting paid. You know these Moors don't believe in banking. They change their money into French gold louis, and hide them in big stone jars. Solomon solemnly assured me that the balance of the purchase price should be handed over here in Casadir, and for once I believed him. I was figuring on those jars of louis. As it is, the Sheik has no notion of parting with a peseta. Well, I've not only got Solomon's deposit as security, but I've also got a good cargo of somebody's guns and ammunition, not to mention the steamboat."

They had reached the gate which gave on the outer sok by this time, and through a wicket looked out upon the trenches of the besiegers, with their tents and horse lines at the foot of the slope. Tall, clean Moors, with tall, short-stocked guns squatted round them under the shade of the port, and passed with Kettle coarse, good-humoured jests on the chances of the day. The Moor of Morocco is always in a genial temper with the savour of war, or hunting, or even of a small vendetta under his nostrils.

A peddler pressed among them with cakes and sweetmeats on a tray. A water-carrier shot a fine stream of water from his slung goat skin between bearded lips for an infinitesimal fee.

"All this doesn't seem to amuse you?" said Kettle to his friend.

"Why, no. At the present moment I'm poor, and for my schemes that I told you about, I must have money, lots of money. Therefore, now I'm commercial, first, last and all the time. You said you wanted money, too, for the mortgage on that farm of yours in Wharfedale. So, why not see if we can't turn a penny while we are waiting for His Whiskers to pay off his debt on the Frying-pan? I've been thinking. Leaving the Sheik out of the question for the time being, here's the simple plan—"

But on this topic, confidences were abruptly stopped. Down the narrow, twisted street which led to the sok port, there came a growing roar of shouts; then the spattering of shots, with which the Southern Moor always punctuates his higher emotions; and presently a solid phalanx of white jelabs, with yellow and red slippers twinkling in and out beneath, with a crop of turbaned heads carried along with them above.

"The Sheik Bergash is dying," they yelled. "He has been poisoned by the N'zaranees. Death to them, death! death! death!"

"Hullo," said Fenner; "this looks like pulling down the curtain before our play has begun."

"I'll thank you not to associate me with anything to do with theatres," said Kettle sharply. "You must know quite well they are bang against my religious convictions. If these swine are looking for trouble, by James, they shall have it." He backed into a doorway and pulled Fenner to his side.

"You're no good with a gun, I know, so when it comes to shooting, aim at your man's stomach, and you'll about get him in the chest. That revolver of yours will throw up like a semaphore."

"I don't think," coughed Fenner, "that we can mop up the entire population of Casadir to our own cheek, but if you give the word, I don't mind having a try. How about when my pistol's empty?"

"Use the butt. Fill your other fist with coppers to give it weight, and slug with that as well. Use your feet, and your knees, too, if they get near enough. It's going to be 'all in' for this scrap. Don't waste your wind."

"My wind!" chuckled his friend, "I like that. As if I ever had any wind to spare."

"By James!" groaned Kettle, "I forgot that. You mustn't exert yourself to fight, or you'll bring on your haemorrhage again and spoil all my physicking. By James!" he snapped out, as Fenner broke into a roar of choking laughter, "if you don't stop that fool's noise, I'll knock you down myself to keep you quiet."

But that uncanny laughter had a distinctly unlooked-for effect. The crowd, after being boxed up for so long in a beleaguered city, were naturally ripe for a little killing, and if some of them were killed in exchange, why that would make so many less mouths to fill. But the sight of that thin, gaunt man, doubling himself up with such unexpected mirth, daunted them altogether.

But that uncanny laughter had a distinctly unlooked-for effect.

They wavered, and at first did not know what to make of it. Then some one murmured "Madman," and the idea grew; and the crowd shrank back shuddering, because they had been very near to slaying one whom Allah had especially smitten and protected.

"Hullo!" said Fenner, "I wish I understood Arabic; what are they frightened of, now?"

"You," said Kettle sourly. "They've got it into their heads that you're dotty. I call it a piece of beastly impertinence."

"Oh, don't call for a general apology on my account. Perhaps they're merely a guard of honour come to see us back to the Governor's house."

"Guard of skittles. They say we have poisoned the chap. I daresay he is poisoned right enough, too. That would explain all those wry faces he was pulling. Well, we shall be in a tight place if he pegs out, that's all. We shall never persuade them we hadn't a finger in it. I wonder if there was poison in that tea, and he intended it for me, and got the glasses mixed. Shouldn't wonder."

"What sort of poison strikes the popular fancy here?"

"Arsenic. Ties them all up in knots, like a fishing line with an eel on it."

"An emetic's the only thing for him, and then milk. Let's go back to the palace and try and doctor him. It will show willing, anyway."

"That's just what they're suggesting. They're offering a sort of guarantee, too, that they'll let us get there all in one piece. Not that I care much for their guarantee. If I had been alone, I could have fought my way through the crowd—yes, and not have disliked the job, either." He put this last sentence into contemptuous Arabic, and very nearly had the whole crew of them on to the top of him again.

The Southern Moor is a fighting animal, and has, moreover, a gracefully high opinion of his own dignity. But the idea that the N'zaranees, if they had poisoned, could undo their work, was growing stronger in them. If the Sheik Bergash died, they could still deal with his poisoners later; and if, on the other hand, the victim recovered, they remembered, with grim chuckles, that the Sheik was quite competent to mete out justice to those who had tampered with his interior.

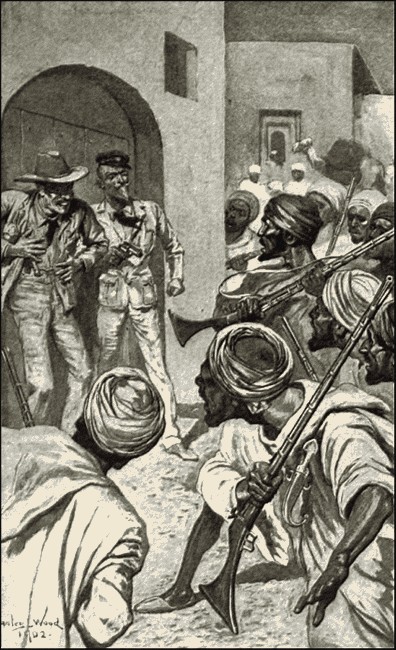

So presently Kettle and Fenner found themselves being escorted back whence they came by a crowd which, though talkative, was not actively interferent, and though Kettle's bitter tongue lashed freely in fluent Arabic, they reached the Governor's house without either being touched, or being forced to draw in their own defence.

Kettle and Fenner found themselves being

escorted back whence they came.

It seemed they were expected. The Sheik's son met them at the inner door of the courtyard, and the outer doors clashed in the faces of their escort. The street outside hummed with their clatter. The house inside was full of armed men, and rustled with the whispers of unseen women. In the middle of the first courtyard was something covered with an untidy heap of draperies.

"That," said the Sheik's son, "was a woman sent by the Sultan (whose name I spit upon) to my father. We knew her to be a spy, but kept her to find out through her who were the other spies. Her use is ended to us, and as she to-day gave my father a cup of tea, she is now that. As for the other spies, they are found too, and their heads will to-night be thrown down the hill into the Sultan's camp where they belong."

"You don't lose time, and that's a fact," said Kettle. "May I ask who it was that spread the report through the town here that it was we who gave your dad that cup of tea?"

The Sheik's son spread his hands. "I cannot tell you. These common people are very ignorant. If the heads of six of them would appease you, I will see that they are sent off to your steamer."

Kettle translated this last offer to his friend. "Nice of him," said Fenner. "Sort of local equivalent for a photograph, I suppose. But, so far as I am concerned, the gentlemen can wear their portraits a little longer. I say, just ask if anything's being done to his Excellency? The longer that arsenic is left alone, the deeper holes it is digging in his inside."

Kettle asked, and the Sheik's son shook his head. What was written was written. His father had made the Mecca pilgrimage, was a Haji, and, in fact, felt himself to be a very holy man, and refused to tamper with the Fate that was dealt out to him. Moreover, neither he, nor any of his household, nor the local hakim knew of any further prescription. A verse of the Koran, written on paper, burnt to ash, and swallowed in a mouthful of water was a remedy for most ailments, but it was no antidote for a cup of tea prepared by the Sultan's woman—late woman, rather—and may dogs eat the Sultan, as they certainly would what was left of his spy that very night.

"That's all very natural and filial, I guess," said Kettle, "but it doesn't seem to me to get Hadj Mohammed any forwarder. He's just fumbling out for the handrail to the bridge of El Sirat this minute, and if you don't look out he'll be dodging the pitfalls and walking over into Kingdom Come. (Heaven forgive me for talking this brand of theology, but I must make the pagan understand.) You needn't regret trying to drag him back. I guess the Prophet will keep his share of green-petticoated ladies unfaded till he's ready for them (and at any rate that's sound theology, because, of course, there aren't any ladies at all.) Come, now, my lad, do you give Mr. Fenner here and myself a free hand to try what we can do?"

"I know you Inglees N'zaranees have wonderful remedies. But there must be no cutting. It is against our faith, and it would annoy my father to enter Paradise with wounds other than those a soldier could boast about."

Captain Kettle formally stroked his red torpedo beard.

"On my head be it. There shall be no cutting. Show us now your father, and send men who shall bring all things that Mr. Fenner here thinks he may want. If emetics can do it, and he's not too far gone to use them, we'll have him scoured out down to the bare bone before you can tell off a chaplet of beads."

Of the remedies that were applied to the Governor of Casadir, and of the results they gave, there can be no more detailed mention in a polite record such as the present. For all the rest of that afternoon and for the succeeding night they wrestled for him (as his son said) with the angel Azrael with every art that occurred to them, and he very nearly slipped through their fingers.

For the next two days, also, it was touch and go, and Mr. McTodd, who was in charge of the S.S. Frying-pan, then rolling to her anchors in Casadir Roads, sent off a much-thumbed note, which stated that if he was expected to keep steam for full speed, as ordered, Captain Kettle had better send off coals per bearer; also a bottle of whiskey, if undersigned was not to faint in the exhausting heat of engine-room, after thumping mate's head at intervals, as per instructions.

In a week's time the Sheik was out of danger, and the Frying-pan in the roads lay with drawn fires. From her at intervals Mr. McTodd sent notes which grew more insolent as their writer's thirst increased. But Kettle saved these up for later reckoning. For the present, he had the Sheik and the Sheik's debt to attend to, and also to spare an ear for the fine schemes of commercial aggrandizement which Fenner was constantly pouring into his ear.

It was no feeling of gratitude on the part of Sheik Bergash that finally made him disburse the moneys that were owing. It was due to an accident. During one of the worst spasms of his disease, Kettle had noticed a small string round the patient's neck, which threatened to choke his last gasping breath. He cut this adrift, and, seeing a small notebook attached, put it in his pocket, and there forgot it. During the early part of the Sheik's convalescence he missed this book, asked for it, and had it surrendered to him at once. Then he favoured the little sailor with a stare that showed behind it anything but a grateful mind.

"It is the custom of Moors, Reis Keetle, to write down in such booklets as these all the principal events of their lives, and then, when the Prophet takes them to his own place, their sons take the book and read it, and profit by what it contains. But, as frequently happens, other hands than a son's get the book, and one profits to whom the dead man was no kin."

"B'ismillah," said Kettle, seeing that he was expected to comment.

The Sheik moistened his lips. "There have accrued to me from time to time certain stores of coin, which I have poured into jars, and (as they filled) hid them, one by one, there and here. The places of hiding are written in the book for my son."

"Oh, are they?" said Captain Kettle.

"It was always my intention to pay you honestly for the steamer, and for the weapons you have brought me. So you may take my men and dig for the jars which are hidden under the middle walk of the garden in the further courtyard. You will find there the sum complete."

"I'm sure I'm much obliged to your Excellency, and when I get the coin on board I'll make you out a receipt with a stamp all complete. But did you imagine I went through that book I took from your neck?"

"Assuredly."

"Then you are wrong, my buck. I can't read a letter of Arabic."

Sheik Bergash thumped a fist on to the mat beside him, and used the only word in English that he knew.

Sheik Bergash thumped a fist on to the mat beside

him, and used the only word in English that he knew.

Kettle grinned. "After all, that little word does ease you better than all the flowery Arabic that was ever invented. Well, there's no time like the present, and I know you wouldn't wish for a chance to change your mind. I'll just settle up these little matters and go on board again. So long, for the present."

He left the room then, called men, and set about these new duties; and two hours later was being rowed off with Fenner to the steamer.

"By James!" said he, patting the tiller, "won't Solomon's and McTodd's eyes fairly bulge when they see the cargo of louis we have brought off. But there are those letters to square for first. You stand by, boy, and watch me settle up with McTodd. The dissolute mechanic! I'll teach him the polite art of letter writing."

"I wish," said Fenner regretfully, "I'd your strength or McTodd's for a friendly turn-up of this kind. I've all the appetite for it; but as it is I can only stand outside the ring and look on. Don't you think it's rather hard to tantalize me?"

"Oh, well," said Kettle, "if you put it like that! Now, I tell you what. We'll tap a bottle of whiskey instead. I've got one hidden, and McTodd will like it just as well."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.