RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Captain Kettle, K.C.B., 1903,

with "The Battle Of The Bees"

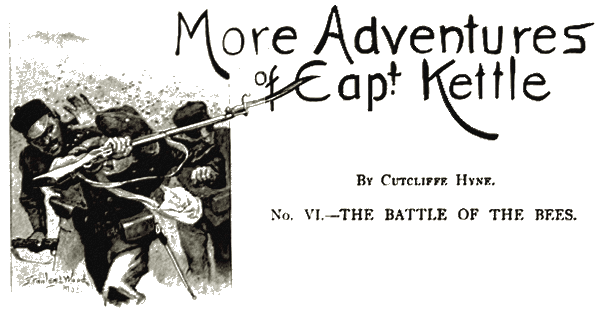

A BULLET splashed noisily through the soft flesh of a dusty aloe in the wayside hedge, and Captain Kettle felt the wind of it as it whop-whopped past his cheek. It was the fourth attempt on his life that day, and he allowed himself to use the language of irritation. Afterward, the crack of the shot came to him from the direction of a thick green cork-wood which ran unbroken up the mountain-side, till it appeared to prop the hot blue sky above.

The little sailor faced this assassin's eyrie savagely. "Fat lot of good it would do for me to go and look for one rifleman in all that timber. He'd run like a hare just as the others did if he saw me start, and I should have all my sweltering run for nothing again. They seem pretty feeble kind of skunks, these Carlists. Well, it's a fool's game for me to be standing out here in the middle of Spain to be made a cock-shy of."

Captain Owen Kettle possessed all of the old-fashioned fighting man's distaste for cowering in cover, and he carried, moreover, the knowledge gathered from infinite experience of how many are the bullets which do not carry out their sender's intentions. But there are moments when even the bravest of men can scurry to shelter without detriment to their honour, so the sailor uttered a few further remarks derogatory to the parentage of the man who was sniping at him, and a few strong hopes against his future salvation, and then left the hot, dusty centre of the road and jumped down into a stone-lined wayside culvert.

Great ragged edges of aloes bristled above the culvert on either side. The floor and walls of it were neatly faced with stone. It was quite dry, and unpleasantly warm, and Kettle had frequently to take the perspiration from his brow with a forefinger. A little further on the aloe clumps were more than ordinarily thick, and their heavy bayonet leaves arched overhead and made a patch of shade. He considered a moment, went to this, sat down, and lit a crisp, frayed Spanish cigar to assist his meditation.

"It's a poor sort of thing, this, to suck at," he commented. "Why they dry out all the juice and flavour from their tobacco here is a crank I never could understand. It's like their preferring aguardiente to Christian whiskey. Spain's a poor sort of country anyway.

"Now, those beggars in that cork-wood will have seen me jump down into this drain and I suppose they'll imagine I'm frightened and will run. I guess they don't fancy I'm just sitting here thinking unkind things. They'll suppose I've either run forward or back, and the odds are the two ends of this road are cleverly guarded. What's more, they've seen enough of my fancy shooting not to try to hold me up with any more of their silly corporal's guards. They'll post a lot of men this time, and I don't undertake to fight through a regiment."

He licked a loose leaf of the cigar back into its place and nodded to it thoughtfully. "This trip's got to be run on patent safety lines, and that's the truth of it. Here are the dispatches in my pocket, and I said I'd carry them through ten times the trouble these greasy Carlists can give, and, by James, I'll do it! There's the pay waiting at the other end for delivery, and it's good pay, and I want it for the poor missis and the farm. I'm not here for fun. I'm not here just to tickle my dirty pride by handling a gun. I'm here for hard cash—or the best equivalent that can be got for it out of depreciated pesetas—and it will be sheer selfishness of me to forget it."

The little man sighed heavily. "I've got to put down my own beastly nature, and have more recollection for those depending on me, and that's a fact."

It was acting on these pious resolutions, then, that Captain Kettle, after exploring the culvert for a hundred yards each way, came upon the course of a stream which fed it, and up the dry bed of this, under a shelter of foliage, retreated rapidly from the dangerous neighbourhood of the cork-wood, in a direction which lay at right angles to the hot, white, dusty, road which he had been originally following.

Captain Kettle retreated rapidly from the dangerous neighbourhood.

For a mile he progressed under this cover, and then, topping a rise, found himself in the open. The stream bed tipped into a little lake, now low with the drought of summer.

He had seldom seen a spot that so thoroughly pleased the eye. The water flashed and smiled at him with a million dimples. The rocks were of a warm and comely pink. Even the patch of waste ground where he stood carried for its weed crop graceful palmetto scrub.

But it was the little farm at the further side which most thoroughly appealed to him. The stout walls of the house were so delicately white; the curled tiles of the roof were so pleasantly red; the bougainvillea which hung to one of its gables offered such exquisite purples. And then beyond were wine grapes on espaliers in full bearing, and field after field of grain ripened under the fine Spanish sun to an entrancing yellowness. Even the dark green ilex forest at the back was musical with the sound of pigs.

He half drew paper from his pocket and a stub of pencil. Pictures like these were rare to him, and always moved him to the composition of verse. But with a sigh he put these back again, and remembered his more immediate business. The envelope he had taken from his pocket contained the precious dispatches.

But he made a compromise with himself. He required food, and might as well requisition it here. He could sit at the farmer's door, and, during the eating of a meal, might still without neglect of duty continue to feast his eye.

With this scheme in mind, he stepped jauntily down a winding path made by the pigs, avoiding with care the sharp hooks of the palmettos which were so anxious to tear his clothes. The circuit of the little lake was long, and Kettle was tempted a thousand times to stop and enjoy new vistas which were lit up so pleasantly by the generous sun. With the side of his mouth which was unoccupied by the peeling cigar, he hummed little tunes as he walked. With his fingers he drummed out the rhythm of sonnets.

The house, when he came to it, was more ample than he had thought. It was perched on a queer little knoll of rock, which had hitherto been hidden from him by a roll of the ground, and it gave one the idea that in some remote era the site had been picked as a fortress. Here Christianity might well have discussed theological points with Islam in chain armour, with every argument punctuated with arrow-shot, and driven home by whistling battle-maces.

But there was no suggestion of the redoubt as Kettle viewed it then. The place was redolent of peace, of coolness and rustic charm.

Bees buzzed round him as he made his way up the last little steep ascent. On the low wall of the terrace, which flanked the house, straw-made hives stood in a generous row.

Laden and empty bees left their trade routes for a moment to inspect Captain Kettle as he advanced. They were a big colony, and therefore powerful and jealous. He was a stranger, and so a creature full of suspicion. It was their custom to fall with blind rage now and again on strangers whose odour and appearance pleased them not, and cause these to leave the place and return no more. They were arrogant, as befits a bee colony which is so large as to consider itself a nation.

Their only master was the farmer, who held the power of life and death over them, and was overlord of their hives and honey, and, in fact, treated them as he saw fit. But the farmer made no attempt to check these occasional excesses by refraining to breed from the more savage hives. He was, in a way, rather proud of them; the bees formed a hedge of defence between him and possible enemies; and he was careful always to mark and preserve the queen bees which would rear the finest fighting stock.

A swarm then of buzzing insects inspected Captain Kettle, and, though he was not exactly comfortable under the ordeal, he did not flinch, and received no hurt. It was his pride always to show an adaptability to rural circumstances.

The escort kept round him as he marched briskly across the terrace to the cloistered front of the house. An appetizing smell and the rustle of frying met his nose as he turned the angle of the house.

The cloisters were heavy and deep, and provided no lengthy view, but, under the shade of the middle one, Kettle suddenly came across a man in a split-cane rocker. The man was enormously fat, and had small, gleaming eyes which stared unwinkingly like a bird's. To him Captain Kettle made a polite bow, and passed the time of day in his best Spanish.

Kettle suddenly came across a man in a split-cane rocker.

"Oh," said the man in English, "you're a Britisher. I was told—well, never mind what I was told. Perhaps you'd like to be rid of that halo of my workpeople?" He flipped a fat hand backward twice, and said, "Sho!" The cloud of bees thinned. "Sho!" he said, "sho!" and the rest of the swarm buzzed away into invisibility. "And that," said he, "is the way we manage bees in Spain, Captain. We are ahead of your English methods. But I suppose bee mastery is outside your line?"

"Everything connected with a country life is of interest to me, sir, and as for ruling bees, well, as I like to be boss of everything that breathes that I'm brought in contact with, I suppose bees count in."

"Admirable sentiments," said the fat man. "Will you honour me by taking lunch? My people will contrive an excellent tortilla, and there is always an olla. As to the wine, I grow it myself and take a pride in my cellar."

Captain Kettle settled himself luxuriously on a green-painted bench. "Sir," he said pleasantly, "you have hit off to a nicety the very things I'm wanting. And may I add that you speak a very excellent English?"

"I learned it in Grand Canary, Captain. I kept a small osteria in Las Palmas."

"Out at the port?" inquired Kettle, with polite interest.

"No, in the town. In a street at the back of the B. and A. office, which you may recall. I see you do not remember me. But a man who has once seen Captain Kettle, and heard his tongue, does not forget either. You used some very injurious language to me in my wine shop in Las Palmas, Captain. Padura was my name."

Captain Kettle rose stiffly to his feet. "I am sorry I cannot recall it. But that being so, you must please understand that I do not apologize. What I said once, I stick to. Under the circumstances you will not want me to stay to your meal?"

"Sit down again, Captain; I will not deprive a hungry man of his lunch, or myself of your company. I do not pay off old scores in that way."

And then, as he saw that the little sailor still hesitated—"Oh, if you are afraid-"

Kettle clapped promptly down on to the bench.

The fat man, without moving in his split-cane chair, called out for Manuela, and in some local patois commanded her to increase the quantity for the meal. Something was said also about a certain Pepe being sent to tell Don Somebody something about an illustrious guest, of which Kettle could barely catch the drift. However, with the memory of his recent resolutions still strong on him, he made interruption.

"If you're sending for more company, Mr. Landlord, please don't do it on my account. I'm travelling very private, and must be off again as soon as I've had a snack."

"Oh, pardon. If you're afraid, Captain-"

"You can send for the whole of the parish," snapped Kettle, "if you think that."

"Just like your old self," said the fat man placidly.

"I despise any one who changes."

Padura let it rest at that. He seemed singularly indisposed to promote further friction, and singularly content with existing circumstances. He did nothing to hurry along the dejeuner. Indeed, from the diminution of the hiss of the frying-pan, and the dying away of its heralding smell, Kettle half guessed that for some reason it had been postponed.

With difficulty the portly host got a hand into his pocket, and produced a case of dry cigars, which he passed across. "I remember how much you used to like those moist black Canary cigars, Captain. But they are not to be got in this quarter of Spain. I can only offer you my best."

"I'm sure you are very polite, Mr. Padura, and I wish I could remember you and your public at Las Palmas, but I can't, and that's a granite fact. I know you wouldn't think it to look at me, but owing to circumstances I've seen trouble in so many places up and down the world, that I can't on the spur of the moment recall all the occasions. So what I said to you in Grand Canary, or did, must stand. But I'm glad we start fair on a level footing now. What hour did you say lunch was?"

"Presently, Captain. It is overdue now. But unpunctuality is one of the things we have to put up with here in this country."

"You have scenery to make up for it. I daresay you'll not have the society here you were accustomed to while you bar-kept in Las Palmas, but the scenery round this spot makes up for all. I could sit and make poetry over it by the hour together."

The fat man's bird's eyes glittered still more brightly. "You still turn out verse, then? I remember they said you were great at it before. I remember your concertina playing myself."

"Accordion playing it was," Kettle corrected civilly. "I really wish I could recall the circumstances of our scrap. By the way, Mr. Padura, did I get to handling you out there, or is it only a mouthful of hard words you've got to complain of?"

"I leave it to your memory," said the fat man with the least possible shrug. "Here comes the lunch. If you can stand full-flavoured oil, I think you will commend the omelette."

Kettle sniffed. "I'm sure I shall. It's the same old smell. I learned to like my cooking done with rancid oil at the other Palma in Majorca. Excuse me a moment." He shut his eyes and said a grace.

"You English," said his host, "are a surprising nation."

"That, Mr. Padura, is the grace used by the Wharfedale Particular Methodists, of which sect I am the founder. I composed the grace myself, and if you ask me I will write you out a copy. It's a race that can be said over any meal. Whether you like the grub or not, you can always be thankful that it is no worse: that's where true piety comes in."

The meal lingered in its courses. It was served by the comely Manuela on a small round table which she brought out into the cloisters, and set between them. Whenever a bee came near her Manuela put down suddenly whatever she carried in her hand and tucked her skirts round her ankles till the creature buzzed away. This, as well as the slowness of the cooking arrangements, tended to hinder matters.

In the long waits between the dishes Padura nibbled olives, sipped wine, and talked placidly on the virtues of each. Captain Kettle fidgeted. He wished to tread once more along his journey. The dispatches had been given him in Ferrol with instructions to hurry. He had guaranteed quick delivery. He wanted badly to receive the pay which would be due to him at the other end.

The dispatches had been entrusted to him under peculiar conditions. He had made his arrival in Ferrol under very remarkable circumstances. As a recognition of one of his exploits there, he might well have been shot or strung up to the modern equivalent of a warship's yard-arm. But, instead, he had been most civilly treated, and had thereafter been set ashore with many ironic expressions of goodwill by some of Her Britannic Majesty's naval officers.

A period of financial depression followed, and lo, one of these same officers came to his relief. A messenger was wanted, it appeared, by the Spanish Government, to carry a very important letter through the Carlist lines to a body of Government troops, whose lines lay at the further side of the Asturias. The country between was frankly owned to be in a state of revolution. Telegraph wires were cut or tapped; the railway line was blown up in a dozen places; and the ordinary postal arrangements were wiped away into chaos. There was nothing for it but to send the letter by hand.

There was not the least chance (so said those who offered the employment) of a Spaniard slipping through the cordon. But a Britisher, if he was sufficiently determined, could get across unquestioned, as the Carlists favoured that extraordinary nation for selfish reasons of their own.

When the question of determination was raised, Kettle took over the job with uncivil promptness. He wanted to thank the British naval man for giving him a "chance of showing these Dagos how we do things," but that officer drily refused to accept his gratitude; and when the spruce little mariner started off on his journey, he took leave of all those concerned in sending him with a good deal of stiffness.

His course had been roughly mapped for him, and he had followed it (as has been recorded above) through some peril, and though he did not happen to know it, he had left the main road only to march into what were but the day before Carlist headquarters.

Captain Owen Kettle was a man always on the alert, and one also who could change from the easy seat of peace into active and aggressive war with incredible swiftness. He was suspicious, moreover, of Padura from the very first mention of that mysterious "trouble" in the wineshop in Las Palmas. He had too much self-pride to make an early retreat, but at the same time he was keenly alive to the ad-vent of possible danger.

The meal dragged its way slowly through several courses. Baccalhao followed the omelette, fragrant of anything but the sea. Then the olla came, exhaling garlic, suspicious in composition, powerful in seasoning, and Captain Kettle wiped his knife and fork on a crust, and attacked a plateful with gusto. Thereafter, at intervals, Manuela brought them a roasted chicken, polenta with caramel sauce, and cheese, and over each course she made at least three false starts, and stopped to tuck her skirts tightly round her ankles through fear of her enemies the bees.

Kettle did well by the meal all through, gave every eulogy to the wine, and drank a bottle of it; and then at the conclusion, feeling pleasantly replete, he said another elaborate grace, and lifted his head from his hands, and words of thanks and farewell ready on his tongue. But a glance at his fat host kept these back. Padura was struggling to his feet, and was obviously disturbed.

"Hullo!" said Kettle, "what's broke?"

Padura broke into a little cackle of laughter.

"The cigars," he gasped breathlessly. "The Canary cigars! I have a box of them inside—fine, black, moist ones that you'll just love. And I was going to let you go off without tapping them. Hind-leg-of-a-saint! What forgetfulness!"

He shuffled clumsily across the cloister toward the heavy oaken house door, and Kettle watched him with a puckered brow.

"There's more than full-flavoured cigars in your mind just now, my man," he muttered. "I wish I could remember something about that row in Las Palmas. Perhaps that will help me to see the bottom of things. By James, what do you mean by that now?"

Padura had passed through the door into the house, had slammed it after him, and Kettle heard the snap of shooting bolts. At the same time another sound fell upon his ear—a sound that was quiet and persistent, a sound that he had got to know by heart during the last two days he had been on the road with these dangerous dispatches. It was the soft pad-pad of rope-soled sandals, not of one pair, either, but of many.

He stepped out into the open sunshine. A company of thirty ragged soldiers had come out from the ilexes, and were fixing bayonets to their rifles as they marched. They were heading for the path up to the terrace. "Now, this," Kettle remarked to himself, with grim appreciation of the trap, "this is Mr. Padura's idea of hitting back. These are the Don Somebodys he told Manuela to send Pepe for. Well, I can't get at Padura just now, because of the front door, and I suppose he's due for something over that old row I can't remember; but it will rile me badly if I don't contrive to twist his tail by way of receipt. In the meanwhile, good-by to this farmhouse. I'm taking no extra risks this trip."

He started off at a quick run round the buildings to look for another path down to the cultivated plain below, and by the time he had made the circuit, found to his disgust that the road by which he had entered was the only one for departure. The face of the cliff on which the house stood varied in height from sixty feet to, at the lowest, twenty-five, and he could come across neither ladder, rope nor spar to help an escalade. Already the soldiers were coming up the winding path, and shouting and making suggestive movements with their weapons as they caught sight of him.

To most people it would have seemed a moment for surrender. But Captain Kettle was a man of resource. A thought came to him, and he ran across the terrace toward the house, and out of the soldiers' range of vision. Then, crouching, he went back again, and stooped behind the parapet till they were just below him. Then, with infinitely quick sweeps of both arms, he sent the straw beehives toppling over on to the troops, half a dozen at a time, and then he very hurriedly left. Captain Kettle was fond of a fight, but he was no man to battle against infuriated bees.

He left these small venomous fighters to do their vengeance on the soldiers, and, judging from the yells and squeals and language that came up, and the buzzing which spread through it all like the diapason of an organ, they smote and spared not.

"Now for a rope or spar to help me down," thought Kettle, and ran away and began to hunt among the outbuildings for these, or substitutes for them, with frantic haste.

He searched a reeking wine-press, he searched the honey store; in the dark he blundered into a place where the corpses of swine lay in the usual embalming mixture, and shuddered in spite of his hurry as his fingers swept the cold, clammy flesh. In the torment of bees behind him the soldiers were still shouting and screaming, and presently an angry, vicious buzz or two round his own head, warned him that the petard he had launched was very uncontrollable, and still effective.

"I must go and get what I want in the house," he told himself, "and then clear out, or else these small warriors will leave the soldiers and start in to eat me up next."

He ran from the outbuildings and sprinted round the house till he found a place where a wooden spout jutted from the wall. With a run he got a hand on to this, and quickly craned himself on to it. More bees were coming up to hasten his movements. He stood on the spout, balancing himself by outstretched palms on the wall, and when he was erect, he could just reach the coping above.

He scrambled quickly on to this, and ran across the flat, concrete roof. The bees were whirling round him in a crowd now, and from two or three he got fiery stings. A door stood before him invitingly. He snatched it open, jumped through on to the head of a stairs, and slammed the door behind him.

Simultaneously with the slam of the door, some one shot at him from below. The bullet missed its mark completely, but brought down a great slab of plaster and whitewash, which sent the little sailor into a fit of coughing and choking. His own revolver, that inseparable companion, was out on the instant, and he charged down the stairs; but what with eyes that were dazzled with the brightness of a Spanish mid-day sun outside, the present darkness of the stairs, and the billowing clouds of dust and smoke, he made a very bad judgment of direction, and went smash into a blank wall, where the stair turned at right angles.

A lumbering step made itself heard beneath him.

"That's Padura," Kettle commented, as he pulled himself together. "I'd like to know exactly what I did to him that time in Las Palmas. He doesn't seem satisfied that he's scored sufficiently even yet."

He ran on again down the stairs as soon as he had got his direction, but he did not come across the fat man. The house was old and big, and it was full of doors and passages, and the number of its rooms was bewildering. It was a perfect warren of a place. Kettle searched it and searched it, listening for sounds, peering quickly round corners, and with pistol always ready for quickest shooting. But he found neither Padura, nor a rope, nor anything that by ingenuity could be made into a rope which would help him down the cliffs.

Manuela he did certainly come across, seated in a kitchen chair with skirts drawn tightly round her ankles and her apron up over her head and hands. She might have looked to the uninitiated like the trussed and mutilated victim of some outrage; but Kettle knew better than this.

He asked sharply for the whereabouts of the patron, and Manuela replied with calmness that she didn't know a bit, and would the senor kindly tell her if there was such a thing as a bee just then in the cocina.

"I'm too busy just now to look, my lass," he said drily, "so you just keep your head wrapped up, and as likely as not it will save you from damage. Are there no more residents to this interesting house but just you and the boss?"

"There is Pepe, of course," said the muffled handmaid, "but he went off for an errand, and he hasn't returned."

"H'm," said Kettle, "I rather fancy Pepe has returned and brought along the errand with him. I only hope those blamed bees have not recognized Pepe as a friend and been easy with him. Well, good-by, Manuela, I'm too busy to stand here making light talk."

He turned away, and once more ransacked every corner of the rambling house for Padura and for a rope. The place was bare enough. A few straw-bottomed chairs and abundance of whitewash made up the furniture of most of the rooms; only three contained beds; and nowhere could he find a cranny where even a rope could lie hidden, much less such an ample bulk as the Senor Padura. Captain Kettle was getting annoyed. He hated to be beaten.

It occurred to him to look out from one of the grilled upper windows, and what he saw there disquieted him further. The troops had given up trying to storm the rock in the face of its bee defenders, and had withdrawn to a distance. Others had come to their help, and the place was now so ringed round that to climb down the cliff side in daylight would be merely to offer oneself as a target for thirty rifles.

A tall, thin, eye-glassed man on horseback had joined the main body, and seemed to be directing operations. The men were busy with something just inside the edge of the ilex wood.

Presently thin streams of smoke arose from that quarter, and then the soldiers again came out into the open, each with rifle in one hand and a smoking, sputtering torch in the other. Kettle watched them advance between the yellow fields of Padura's grain, till they were eclipsed from his view by the angle of the cliff, and he began to recognize that he was in a very awkward position. There was nothing for it but to stay where he was and take his chance; to attempt an escape could only mean being shot down at long range without chance of retaliation; final terms would have to be a matter of arrangement.

But, even in these ugly circumstances, Captain Kettle's loyalty to his employers—or his personal pride—were still uppermost. Whatever happened to himself, he had no mind that the dispatches should fall into Carlist hands. He peered about him for a while anxiously, and then, spying a roof-beam which had warped away from the concrete flooring above, he balanced two chairs one on the other, and stood on the uppermost, and slipped the precious envelope into the gap.

"And now, you beggars," quoth he, as he dragged the chairs back again to the flanks of the room, "I've diddled you that much, anyway, and what I've got to see to now is, first, that you don't shoot me out of hand; and, second, that you don't torture me to get them. Torture!" he repeated to himself. "By James, no! I must see it doesn't come to that. And they're equal to it, the brutes, so Eve heard. If there's a doubt on the matter, I must just peg out—scrapping."

The advance of the troops this time was unopposed by either man or insect, and presently fierce faces and rifle muzzles were peering in between the bars of the lower windows. But these were too strong for easy displacement, and a great beam was fetched from the wine-press, and with it the oaken front door was battered from its hinges. Then a gush of bayonets, with savage men behind them, swept into the house, and sent through all the rooms and stairways the din of their shouts and the reek from their smoking torches.

Then a gush of bayonets, with savage

men behind them, swept into the house.

Kettle sat in an upper room smoking the last cigar he had in his pocket, and waiting upon events. He wished the invaders to get the first edge off their tempers before he engaged their attention. He could hear the pad-pad of their rope-soled sandals all over the house. He could smell also a scent of warm humanity and garlic which seemed to make their presence very real.

But as has been said, the house was large and rambling, and the way to many of its rooms was not easy to find. Kettle heard the soft pad-paddings and the blows of searching gun-butts on three sides of him, and also above and below; but for fully half an hour he sat and smoked undisturbed. Then a man came into his room, saw him, started, and tried to get his bayonet to the charge. But Kettle was upon him before he could do this, and had crammed a revolver muzzle against his throat.

"El Ingles," stuttered the man.

"An Englishman," corrected Kettle civilly, "and one that requires decent treatment."

The man dropped his rifle, as though to show pacific intentions, and turned his head and bawled through the doorway: "El Ingles, acqui!"

"Better tell your friends not to try any tricks," suggested Kettle, "or your mother's son will only be a dead hero." But the fellow seemed satisfied, and made no further struggle; and presently up came the tall, lean officer who had been riding the horse.

He settled his eyeglass, and looked at Kettle's small, spare form with obvious surprise.

"So you're the man who's been setting the countryside a-boil, are you?"

"You flatter me, General."

"I heard you'd left Ferrol."

"Most of Spain seems to have been let into that secret."

"Pff! Well, give me your dispatches, man."

"Not one look. They're hidden where you'll not find them, so you'd better take things easy and not try. It was to General Dupont I was paid to take them, and it's to him they're going, or to no one."

The tall man laughed. "May I ask whom you take me for?"

"The Carlist boss, I suppose."

The tall man laughed again. "A fellow named Pepe made the same mistake. We'd taken a Carlist camp up at the back there this morning, and were occupying it. He thought we were the rebels, and invited us here. Well, we have strung up Mr. Pepe, but we accepted his invitation all the same, and a rough time some of my fellows had of it. I wish I could catch the ruffian who capsized those bee-hives."

Kettle made no interruption. His pride urged him to claim credit for the strategy, but his new prudence forced him to hold his tongue.

"However, we came in here at last, and found the bulky ruffian who owns the place-"

"By James, did you now? I've looked for that man all through the old barrack myself. I've an account to square up with him."

"Then you didn't look in the right place. There's a well in the floor of the kitchen here, and the fellow was in the well. There was a maid-servant sitting on the top of the trap-door. However, we soon had him out of that, and I'm afraid we've anticipated your private vengeance. The man's, as you English say, expended."

"Dash!" said Kettle thoughtfully, "and I've got something very particular to ask him."

"I'm sorry, but I couldn't know that or I'd have waited. As it is—" the tall man waved an explanatory palm and dropped his eye-glass on to the end of its string. "And now you may as well give me those dispatches, as there seems no chance of your carrying them further. I am General Dupont."

But Kettle's mind was not yet rid of all its suspicions. "I'm sorry, sir," he said doggedly, "but I've only your word for it that you are the gentleman you say you are. I'm taking no risks. Confidence-trick men are as thick as wayside aloes in this country, and I understand my responsibilities. General Dupont is said to be in Hijola, and that's where I'm taking him the letter."

"As you please. It's hard, perhaps, to have to say it to you, but the dispatches were intended to fall into Carlist hands, and to me they are valueless."

He went to the grilled window and shouted down—"Hola, you men, what is my name?"

"General Dupont," came the reply from twenty lips in varying tones of surprise.

"Then I have been made a common tool of?" snapped the little sailor.

"I suppose you have been paid," said the general, rather more coldly.

Kettle climbed up and got the envelope from under the beam. "That puts me on to the ground floor at once. I have not been paid. The letter is marked 'cash on delivery,' and I will trouble you for three hundred pesetas. Your clever friends in Ferrol measured me with their own tape, and I've shown myself a bit too big for them, that's all. If they'd told me what they wanted done, they should have had it. But as it is, their little game's failed, and you've got to pay for it all the same. I'll trouble you for cash, please, at your early convenience. I've business to attend to further on in this sweet country, and at the same time I'm free to tell you flat that the neighbourhood you happen to be in offends my personal taste."

"I will see that you have the money at once," said the General curtly, and turned on his heel.

Ten minutes afterward Kettle was leaving the farm, with the notes in his pocket, and another lit cigar crumbling in the corner of his mouth. His eye wandered over the cornfields and the pink boulders, and the pleasantly dimpled lake. His ear listened appreciatively to the pigs which rooted among the ilexes. But his thoughts were still back in the white farmhouse on the top of the knoll. "I'd give a lot," he muttered to himself, "to know what I really said to the late Padura in his osteria at Las Palmas. I wonder if I used my hands to him as well as talked. But it will be all guessing now. I don't suppose I shall ever really know for sure."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.