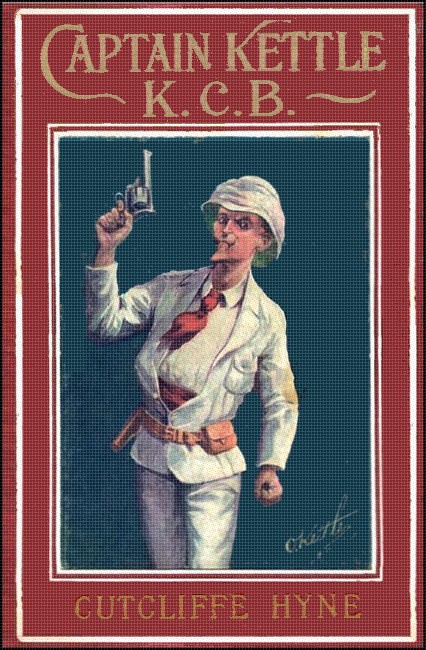

RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Captain Kettle, K.C.B., 1903,

with "The Submarine Boat"

"FUNNY name—Kettle," said the fat man with the glass eye.

"Shouldn't advise you to tell him so," snapped little O'Hagan. "He takes himself pretty seriously, and if some of us followed his example in that respect we should get through a lot more business. I've no use, personally, for making myself ridiculous."

Burke, the man with the glass eye, reddened with fury.

"You know I only meant it as a joke, and the joke didn't come off, that was all. How was I to guess they'd be such abject fools as to stop the ship, and send a diver down, and find there was no gun-cotton in the thing after all? Any other navy with a cent's worth of sense would have taken it for granted the thing was a torpedo and skipped. But those fool English were too dull to think they might get hurt, and they are as curious as monkeys. But"—he thumped the table—"I'll have no more of this. I may have made an error, but I have been twitted about it sufficiently. There was nothing criminal in what I did. No one ever suggested yet that I wasn't true to Ireland. No one has ever chucked out hints that I was an informer."

"What!" the frail O'Hagan stamped to his feet.

"Gentlemen, gentlemen!" The girl at the end of the table, who had sat still, biting her lip, during all this wrangle, interrupted them sharply.

They broke off and faced her with some confusion.

"I used to be cold and contemptuous," she said bitterly, "when I read in the English papers of some great Irish meeting described as 'the usual Donnybrook.' But now, when I see that taunt, it makes me hot with shame, because I know it is true. Can't we even here learn to control ourselves, and stick to the business we've come about? Is there some curse on the race that always makes us behave like fractious children?"

O'Hagan bit his lips. "Miss Ffrench is right. We seem born with an unfortunate knack of riling one another. Burke, I beg your pardon. Let's please consider all these last remarks eliminated, and get back to Captain Kettle. I don't see what's wrong with having him up right now."

"That suits me," said Burke, "unless Miss Ffrench wants to give us any more pointers first. No? Then I'll go and fetch him."

Presently Captain Kettle stepped briskly into the room, and bowed politely to the lady. "Most pleased to make your acquaintance, miss," said he, on being presented. "Mr. Burke did not tell me this was a yachting job. I thought it was business."

Captain Kettle observed that the lady rebel was deliciously pretty, and put on his pleasantest manner. He had always had an eye for a good-looking woman. Indeed, Mrs. Kettle herself had first attracted him by her outward person, and it was not till after long acquaintanceship with her across the bar where she did business that he found those deeper qualities which brought him into her service, and held him there with such unwavering faithfulness.

Kettle smiled pleasantly. He always had an eye for a pretty girl.

Miss Ffrench knew her power, and used it to the full. She gave the spruce little sailor the kindest of looks, but it was the bitter O' Hagan who thrust himself out as spokesman.

"The employment we offer you, Captain, is not to conduct a yachting cruise, nor yet could it be exactly described as business. But until we learn your definite decision as to whether or not you are going to enter our employ, there are reasons why we should not be too precise. I'm putting the matter frankly, you see, and if you're offended I hope you won't trouble to conceal it."

"If I'm offended, sir," said Kettle, with acid politeness, "people usually know it without delay. But in this particular instance I'm not a man that can afford to pick and choose employment. As I told your Mr. Burke here, I'm in severe financial difficulties for the moment. You see, owing to agricultural depression, we've not been doing as well as could be expected, and there's a mortgage on the farm."

"You are interested in agriculture?" said the girl. "Then you will be able to sympathize with poor Ireland."

"Certainly, miss; I've never been in Ireland myself but once, and that was under rather distressful circumstances. But I made poetry about the country that seemed to me to carry both tune and truth with it. There was one set of verses which began 'Peaceful isle of simple green,' which appeared to me at the time singularly chaste and original. If you like, miss, and these gentlemen will excuse me, it would give me sincere pleasure to repeat them to you."

The girl's lip quivered, and Burke blew his nose and wiped a tear out of the corner of his glass eye. O'Hagan frowned aside the interruption. "Come now, Captain, we're wasting your time. Do you agree to join, and what's your figure?"

"You can have me as low as £14 a month, sir, and if the job looks like a permanency I might do it for even a trifle less. I'm very anxious for those at home to have a steady half-pay of mine to draw upon."

"Ah, I see." O' Hagan looked at him queerly. "What should you say now to £30 a month?"

"I should say there was something fishy about it."

"There'll be some risk."

"Any sailor man expects that."

"There'll be fighting, too. I suppose that will put you off?"

"If," said Captain Kettle unpleasantly, "you'd done one-twentieth of the fighting I've put in at one time and another, you'd retire into private life."

O' Hagan laughed and flushed with self-contempt.

"I'm not a fighting man, and I admit it. I've a weak heart, and a weak nerve; but I can plan, and I can invent, and what we want is a man capable of carrying out the result of my plans and inventions. Come now, Captain, you must give us a plain answer. Do you join or not? It seems to me the job looks a bit too troublesome for your appetite, and we don't want to have you refuse, and then go away and be able to talk."

"I've no choice about the matter, sir. I've got to have employment. I join, certainly."

Burke wavered an eye over him. "Isn't there some story about the police rather wanting you? I don't want to be rude, you know. It's a thing that might happen to anybody."

Captain Kettle pulled at his red torpedo beard. "I'll not deny, sir, that I've been in trouble. But I've heard of no warrant being out, and it wouldn't surprise me if none was issued. They'd nothing to be proud of. There was just me—one man—and I very sick at the time, and hadn't so much as a gun to help things along with. On their side there was a whole army of them, with certainly one pistol fit for business, and a whole ship stuck full of belaying pins. It doesn't matter what the difference was about, but there's the odds, and when we had our scrap I came out on top, yes, and, by James! could do it again. They let me crow over them from start to finish, and you don't tell me they'd want to reel out a yarn like that before a stipendiary, which they'd have to do before they could get a warrant."

The girl's face glowed as she listened. She stood up and shook Captain Kettle's hand. "You are just the brave man we want," she cried. "I can see it. The justice of our cause you will come to appreciate later. But to begin with, you are a man who loves a fight for a fight's sake."

Kettle dropped the lady's hand and sighed heavily. "That's true, miss. Heaven knows it's true, and that it's my greatest weakness. Ashore in England I try to live a Christian life, and have met with considerable success in the attempt. You may have heard of the Wharfedale Particular Methodists? I'm founder of that sect, miss, and we've probably got a more sharply defined creed than any other religious body on earth. But when I'm away from England, or when I'm at sea—well, circumstances have always been too strong for me."

"I don't know," said O'Hagan unpleasantly, "whether a gentleman with such powerful convictions as these won't want to press them upon our notice at inopportune moments."

Captain Kettle stiffened at once. "My shore convictions need be no concern of yours, sir. They were brought out entirely for the lady here. You offer £30 a month, and I take it, and will carry out my orders. I'm loyal always to the owner who pays me, and that's all a shipmaster's conscience has to trouble itself with when he's on service. If there's anything dicky, or if there's anything wrong done, that's the owner's lookout."

Burke blinked cheerfully with his glass eye.

"You're quite a theologian, Captain. Well, call that settled, then. Here are three fivers, by way of your first month's half-pay, in advance. You're at the same temperance hotel, I suppose?"

"Yes, sir. If you think I ought to move to more respectable quarters, I can afford it now."

"Not at all. Great thing is to keep inconspicuous. Go and enjoy yourself for the rest of the day, Captain. I'll call upon you about 11.30 to-night."

Now the three people who remained behind in that room were conspirators who were straining every nerve to be dangerous. O'Hagan was an inventor; the sardonic Burke was a clever agitator of the underground type; and the girl, with her good birth, her magnificent beauty, her splendid voice, and her passionate eloquence, was one of those rare orators that the centuries now and then bring forth with power to win great audiences over to any cause. Ireland was their country, and a blind ecstatic hatred for England formed their motive power. But this last point they did not yet bring to the notice of Captain Owen Kettle. They preferred to have their recruits thoroughly involved before they trusted them in any way deeply.

As a cloak to their larger object Burke and Miss Ffrench addressed frothy meetings (when they could not contrive to get these suppressed by the police), and in other ways contributed to keep up in Ireland that social atmosphere which has existed there ever since political explosives were first invented. The little O'Hagan worked as a fitter in an engineer's shop, and earned there a steady three pound ten a week.

Miss Ffrench was interviewed by the papers, had her photographs (very lovely photographs) published, and was commented upon by the public prints in varying degrees of kindness. Burke, strive though he might, could never bring himself into prominent notice without an accompanying spell of jail, which, being a man of tender tooth, he detested.

O'Hagan kept out of the public eye entirely. He was a fellow of infinite disappointments. He was a clever inventor who lacked commercial aptitude. Nine-tenths of his patents were never taken up, and the remaining tenth were stolen from him by urbane employers; and somewhat naturally he bit against fate. A chance speech of Miss Ffrench pointed out to him clearly that the other name for fate was England, and he jumped eagerly at the chance of doing that country harm. Especially did the opportunity please him, since here at last was a chance of displaying the value of his adored inventions.

To evolve from these ingredients, then, the scheme for building a submarine torpedo boat designed to blow up the ships of the British navy, one by one, till that proud nation submitted to the sister island, was the easiest kind of effort imaginable. Getting the thing put into practical shape offered no very great difficulties. O'Hagan resigned his fitter's bench, and the income therefrom, to live on sixteen shillings a week, and take over the drawing office and oversee construction. O'Hagan bubbled with vindictive invention. Miss Ffrench addressed great meetings of the Irish with silver tongue, hinted at an enormous weapon that was being forged for England's overthrow, and drew in abundant subscriptions; and Burke, who disliked settled work, made a great display of toil, and did nothing very effectively.

Only on one point had this committee of three any difference of opinion, and that was over the site of the projected shipyard. Burke was all for America. "You can build what you like in the States," he said, "and no one will interfere. There will be no question of jail for any of us in America, and there might be here. Some one's bound to inform. Besides, we'd get heaps of subscriptions from our folks in the States, and we'd be able to live a bit better than we can here in Dublin."

"I hate America," said the girl bitterly, "and our renegade émigrés over there. They froth, and they talk, and make themselves ridiculous, and in effect they do less than nothing for Ireland. I want to see the boat built here. Surely we have not sunk so low that we cannot build our own avenger in our own country?"

"Might try Harland & Wolff," said Burke, "but I doubt if they'd take on the contract. Belfast's Orange, you see."

"You laugh, but I don't see that it's at all impossible. The West Coast is lonely enough. Surely we could find some lonely island off Connemara, or County Mayo, or some great cave in the cliffs where we should be undisturbed."

"That's like they do in novels," said Burke, "but unfortunately in practice it would be impossible. You've got to get your materials from somewhere, and the steamer people would talk, let alone having to reckon with the inevitable informer against your own workpeople. The brute Government would know all about the game from the word 'go.'"

"Of course they would," said O'Hagan. "They always do, you know, although sometimes it suits them to play the thickhead and make out they don't. But do you think they'd interfere? Not a bit. They're too beastly contemptuous. Why, if we set up a works in Liverpool, and the crowd got to know, and tried to lynch us, they'd give us police protection till we'd the thing launched and were ready to proceed against them. I hate the idea of going out of Ireland. The sea makes me so horribly ill. I'd rather have an arm amputated than cross to Holy-head. But that's what it's got to be. I'm speaking as an engineer, and I tell you plainly this thing's going to be built in no amateur workshop. The States would be best. They've got the best machine tools in the world over there; but I flatly refuse to cross the Atlantic under any consideration what-ever. So if you want my help—and you can't do without me—it's got to be England or nowhere."

It was this choice of a site for their building yard more than anything else which put poor needy Captain Kettle off the scent of the end to which his new employment trended. A man more aggressively patriotic it would be impossible to find, but beyond the marches of Great Britain his sympathies were narrow. He had wandered widely, and (through bitter experience) had gathered a vast dislike for other nationalities. He was one of those aggressive Islanders who would as soon fight as shake hands with any foreigner.

Once hired, Kettle was his owner's man to keep the peace or make war, entirely as orders directed, and (except for this end) he took no private conscience to sea with him, Severe critics, who for one reason or another have no sword to sell, sneer at the trade of the mercenary, though there have been honourable men in the one occupation as in the other. But it never occurred to Captain Owen Kettle that people might criticise his actions from such an abstract standpoint, and if it had come to his knowledge the circumstance would not have ruffled him.

He was a man who cared nothing for blame from any one except an owner, and usually looked upon praise as an impertinence. He was a man doing his utmost to earn money for the present maintenance of his family and a chapel, and carrying with him the ultimate hope of returning to these, and enjoying moreover the agricultural ease of a moorland farm.

When he came to her, the submarine boat was practically finished, so far as the shore-going brain of O'Hagan could invent and design. Kettle looked her over, inside and out, with a critical eye. She was new to him, of course, entirely new, but all modern steamer sailors are, to a certain extent, engineers, and he took in her various points appreciatively.

O'Hagan escorted him round, fluttering with anxiety that he should like everything, bitter and caustic at all his objections. Here were the horizontal rudders, actuated automatically by an internal pendulum to prevent unpremeditated dives. In these sponsons were the vertical propellers to force her under water. The water ballast tanks were here and there, with independent ejector pumps to each. These were trimming tanks. There forward was the torpedo-room, and here was the store of spare Whiteheads. The main engines were aft, three sets of them, four cylinders to each, water-cooled, explosion gas-engines all. Here were the pumps for the water circulation. Here were petrol tanks. These were the carburettors, and did the Captain think spray carburettors would act pleasantly in a sea-way?

"Don't know, sir," said Kettle. "Outside my line. Steam's all I know. It's the first time I've struck these kerosene engines, and I must say they strike me as smelly. But do I understand you to say they've all to be started by hand?"

"Of course. Of course. Here's the starting gear. It's quite simple. If you understand anything about oil engines you'd know they must be started that way."

"I've just told you I didn't. But as a navigating officer I've got to point out if I telegraphed for 'full speed' on one of the engines, while you were grinding up one of your blessed handles, we'd either be into the next ship, or knocking a hole out of the ground if there was any handy."

"Not a bit of it, Captain. Once you are under weigh, the engines are kept running continuously. When you want the propellers, they are thrown into gear with these friction clutches. The same with the diving propellers on the sponsons."

"You've got a big head, sir," said the little sailor admiringly. "I never saw so much strong machinery tied up tight into tangled knots during all my going to sea. Whether you'll ever keep it in hand, James only knows. How do you go astern?"

"These three friction clutches here. I've provisionally protected twenty-three clutches in my time, but none of them have been taken up, and I've never been able to afford the full patents. You'll find the best of them here, and they are real nailers. Some people would have used gear wheels, but I take no chances. Good clutches are dead safe."

"H'm, I don't know. If you used helical bevels, I don't think they would have been stripped. However, it is a matter of opinion. You've only worm steering, I see. Pity you couldn't give us power for that, too," and away they went off into technicalities.

O'Hagan and Kettle alone appeared as officially connected with the building yard, and Burke and Miss Ffrench met them only under conditions of laboured secrecy. "I know, Captain," the girl said to him at the first of these mysterious gatherings, "a man like you will require no explanation of why we have to come together on the quiet like this."

She trusted that the little sailor would be ingenious enough to invent an explanation for himself, and he did it promptly.

He winked a sharp eye at her. "There's no man in England understands the Foreign Enlistment Act better than me, miss. You leave it to me, and I'll see we get the little packet snugly to sea. The English Customs people are always a bit too late when it comes to stopping anybody. I've slipped through their fingers over a job like this five times already."

Miss Ffrench bit her lip. "Then you have guessed already the flag you are asked to help."

Kettle smiled genially. He always had ah eye for a pretty girl. "Why, yes, miss. Now you put it that way, I can see it clearly enough. You're an American. I ought to have guessed it at once by your Irish accent. Well, I'm not much up on foreigners as a rule, but I'm glad it's no worse. I've known some very fine accordion players come out of America, and men that knew a good hymn tune when they heard one, too."

The first performance of the submarine boat at sea made up a story of unmitigated disaster. O' Hagan, her constructor, with the horrors of mal de mer always before him, flatly refused to budge from shore. The machinery was in charge of the only three engineers they could pick up, and these all proved themselves incompetent.

The antics of steam, and of steam machinery, they protested they carried at their fingers' ends; but these explosion engines were new to them, and after a first trial of their infirmities they were not disposed to make many further efforts toward understanding them. Besides, they were seasick, abominably so, and for that matter everybody else on board the little vessel was seasick also. Even that toughened veteran, Captain Kettle, suffered from this devastating ailment, and it was only by an effort of his tremendous will that he contrived to stick on at duty.

The movements of the submarine were disgusting. In a sea-way, when she was on the surface, her rolling and pitching and wallowing was intolerable. When she took a dive, as often as not she would commence matters by turning a complete somersault, stern over stem, rattling about her unfortunate crew like peas shaken in a drum.

The air for the gas engines and for breathing was officially supposed to come down two long flexible tubes, which towed outboard, and had their upper ends carried on the surface of the sea above, by means of highly ingenious floats. That is to say, in theory and on paper the floats were highly ingenious, but in practice they sometimes dragged under altogether, whereupon the explosions in the gas engines would weaken and cease, and the human manning of the craft would gasp and think the last minute of their life had then arrived.

Under such infernal conditions, then, was this first trial trip carried out, and nothing but Captain Kettle's venomous tongue and rough handling of each individual member of his crew held the horrible little craft at sea. He kept on repeating: "Wait till you are used to her, and then she will travel all right." And as is mentioned above, he induced his crew to "wait" by methods peculiarly his own.

But human endurance has its limits, and continued seasickness under these conditions is one of the most devastating of ailments. One by one the crew relapsed into an unconsciousness from which neither beating nor vituperation would extract them, and at last the unpleasant truth was forced into Kettle's aching head, that if he didn't want his unpleasant command to become a mere derelict, he must run back forthwith to harbor.

In his subsequent meeting with his employers, considerable temper was shown on all sides. O'Hagan, as inventor, held that the boat's construction was in every way correct, and that only bad handling made her unwieldy. Kettle, white-faced and ill, promptly went through that boat piecemeal, from her lubricators to her conning tower, and belarded each point with offensive criticism.

"You want pressure lubricators, any one but a shore-living drawing-office man, would have known that," and he threw sarcasm on the existing lubricators, and on a hundred other matters, in a way that made O' Hagan bubble with helpless profanity—"and don't you swear at me," he wound up. "I'm in your employ, I know, but I'm a man used to respect, and, by James, I'll have it! Besides, there's a lady present, and I value her opinion too highly to talk back at you in the way you deserve."

"And don't you swear at me," he wound up.

"I'm in your employ, I know, but I'm a man

used to respect, and, by James, I'll have it!

Burke tapped the table. "Yes, yes, yes, it's all very well, but while you're squabbling over these technicalities, it strikes me the police may be here to arrest us any minute. I've no immediate need for another spell of jail myself."

"How's that?"

"Why, the Captain here has sacked all his crew, or they've deserted, which amounts to the same thing, and perhaps you think they won't talk. I don't see how the Government can avoid getting to know."

"Talk," cried the bitter O'Hagan, "of course they'll talk, but as for the fool Government, you needn't be scared of them. You can bet your life they've known all about us from the first word start, and they've been too beastly contemptuous to stop us. You'd have to blow up half the British Empire before their muddy brains could understand there was anything wrong."

The man was very near blurting out dangerous truths, and Captain Kettle was beginning to get startled. Miss Ffrench took the situation firmly in hand.

"Gentlemen, please, this wrangle must stop. We have all had a bitter disappointment, and Captain Kettle has undergone much physical suffering. He is the only man who has seen our boat in practical work, and his views should certainly be received with deference. I know he did not mean all the warmth of language he used in his criticisms to be taken literally. But even he does not wholly condemn the boat. He only insists on modifications which his practical experience has shown are necessary, and I am sure Mr. O' Hagan's genius will see a dozen ways past these difficulties."

The little sailor pressed a hand against his aching head.

"Thank you, miss. It's good of you to back me up like that. But I don't think the job will suit me any further. I'm a poor man and I want money, but there's a bit too much temper shown against the British Government for my taste. Now, I'm not here to defend them; they've treated me pretty toughly one time and another; but when it comes to causing that Government pain (which it dawns upon me is what you're after), why, there I'm the wrong man to help. I'm a Britisher first, last and all the time, and it doesn't do for anybody to forget it."

The three conspirators did not dare to look at one another, but they all seemed struck with the same shiver. It was the girl who found presence of mind to promptly tackle the situation. Her voice was pleasantly sympathetic.

"My dear Captain Kettle, didn't you guess our real nationality for yourself? And I don't think, according to the latest evening paper, that America is at war with England."

"No, miss, that's a fact. I fancy Spain's giving the States all the trouble they've any use for at present."

"Ssh! It's dangerous even to whisper these things, but as you've guessed half a secret, Captain, you may have the rest. So soon as your improvements are made, and the boat is in proper sea trim, we wish you to take her down to the coast of Spain and there begin her work."

"Well, I've no special objection to that. I've a poor opinion of all Dagos anyway. But if this is to be war, I'd like to have some sort of official guarantee it's all right. You must pardon me for bringing up these business matters, miss, but I must point out to you that to every fight there's an afterwards."

Miss Ffrench smiled brightly. "You are entirely right, Captain, and I will give you the best guarantee I can think of. I will come with you myself."

"And these other gentlemen?"

"Oh, of course," said Miss Ffrench, with a desperate gaiety, "they'll come, too, as my personal escort. Now, my dear Skipper, do go off to bed. You look worn out."

It was not at the next trial, or even at the next after this, that the submarine boat behaved with anything approaching efficiency. In fact, as a sea-going craft, she always hunted for disaster so hungrily that under no circumstances could she ever become popular as a mere vehicle. No one but a man as hard-up and desperate as Captain Owen Kettle would ever have consented to stay by her after so many damping experiences of her evil qualities. But the pay was there, at the rate of £30 a month, and it was paid each week with regularity, and the poor needy man could not afford to lose it.

Finally came the day when she was reluctantly passed as fit for sea, and was ready to start off on her murderous cruise. Sheltered behind one excuse and another, up till now his three employers had always stayed ashore, but Kettle showed plainly that he was not going without them, and so they had to come with him.

Miss Ffrench joined last. She had been waiting ashore to bring off the last telegraphic news of the warship they were going to destroy, but once she came, the engines were started, Kettle gave his orders, and the uncomfortable vessel wallowed out of the river and rolled and pitched her way to sea, running on the surface, with her full freeboard.

Kettle set a course, and handed himself below to the stuffy little box of a cabin. The girl sat wedged in one corner, pale, but resolute-looking.

"All going as you could wish, Captain?"

"Well, miss, as you see yourself, she isn't exactly the Cunard for comfort, but nothing's broken down yet, or offered to. My new chief thinks he knows all about gas engines, and says at the present rate of consumption we've got enough petrol in the tanks to carry us half round the world. I will say this—it's a wonderful fuel for close stowage and bad scent. Are you sure that Spanish warship will wait in Ferrol till we get down to her?"

"The ship will be there. I've got certain information."

"I can't say I particularly like blowing up these poor wretches of Dagos. Wouldn't smashing the propellers of their vessel do as well?"

"No. The blow must be a deadly one, or half of its effect will be lost. War is war, Captain, and the heavier you can hit, the sooner it can be ended."

Captain Kettle sighed. "I don't like to see a pretty young lady like you taking up a murdering job like this. I suppose," he added sympathetically, "the gentleman you were walking out with didn't behave as he ought to have done, and that's drove you to politics. I wish I could have come across him, miss. I'd have combed his hair for him. Yes, by James!"

The voyage which followed on was one of unmitigated discomfort. The seas, as if disliking this new intruder, displayed to it their roughest humor. The boat picked up a gale in the Channel's mouth, and carried it with her down to the Bay, where it was reinforced. Inside the evil-smelling, badly ventilated hull all suffered from nausea and from chronic headache. There were no formal meals. They ate sardines and biscuits with their fingers, and everything they touched mired them with oil. Even that ultra cleanly person, Captain Kettle himself, could not keep his hands and clothing unsoiled.

But there was no doubt about it that they were warmed up to the work ahead of them, and this alone kept them up to the abominable strain. At last, however, one afternoon they rounded Cape Ortegal, and with nightfall were round Cabo Prior, and then felt their way up to the entrance of Ferrol Harbour. They ran in with the conning tower just awash, and the air tubes in action, and tugging at their floats astern. Nearer and nearer they drew. Kettle held the spokes of the steering-wheel himself, and the girl stood beside him in the tower, white and panting with excitement.

Presently, out of the night ahead, the outline of a great battleship loomed out. The girl was gripped with such a fierce excitement that it almost choked her. "That's the one, Captain. Dive now—dive, please—dive. I order you to. Do you hear, I order you!"

Kettle would have preferred to run closer. He knew the difficulty of steering a straight course under water, and had the order been given by one of his male employers he probably would have neglected it and followed his own opinion. He was never a man who cared for much interference.

But with Miss Ffrench it was different. To begin with she was a lady, and there was the item that he liked her. He issued short, crisp orders, and the boat rocked and sank, and he steered as well as he could by gyroscope and compass. A Whitehead torpedo was in its tube forward, and Burke, with his one sound eye glaring murder, crouched in the narrow nose of the boat beside it, ready on the word to start its engines and send it forth to devastate. Captain Kettle in the tower calculated his distances and watched the dial of the log. They were only eight hundred yards away now. He would give the order to fire at one hundred and fifty.

Then softly there came to him the sound of some of the cylinders of one of the engines "cutting out," a sound which by this time he had got by heart. Then that engine—the port engine—stopped, and he had the pleasing knowledge that, in spite of a hard-ported helm, the boat was beginning to turn round in a circle.

He used all the encouraging language he could command down the voice tube, and as this had no effect, he left the useless wheel and went himself to the engines.

A very tired, white-faced engineer pointed to the damage with a spanner. "Ball-tap's jammed in the carburettor, and I can't bash it clear from outside. Take me a couple of hours to get it pulled down and fixed up right again."

"Where's O'Hagan?"

"Drugged silly, as per usual. He's-By George, Captain, look at that! There are those two air tubes fouled and sucked under. Get us up quick out of this, or we shall stay down here for good and suffocate. There, you see, the other engines were beginning to stop before I cut off the gas. Now we shall have to sweat those blessed ballast tanks empty with the hand-pump. Who wouldn't sell a works ashore and come to sea in a submarine!"

The boat was pumped ignominiously back to the surface in this manner then, and arrived there to find itself in the middle of a blaze of radiance projected from a warship's searchlight. When the hatch was taken off, and the white strained faces came out gasping for breath, a couple of smart white picket boats steamed up, and their officers and crews had the appearance of a storming party.

But with the arrival into the light of Miss Ffrench this attitude was changed. A beautifully blushing young English sub-lieutenant saluted, and presented Captain somebody or other's compliments, and wouldn't the lady and her friends come on board and sup.

There are some invitations which it is ungracious to refuse, and others which it is unsafe to decline. Captain Kettle, sick with disgust at finding he had been tricked into an attempt at torpedoing a British ship, was going to blurt out that they were pirates and could only come on board to be hung. But the girl interrupted him. "Please let me speak. It is the last thing I shall ever ask. And I will explain to you afterward. Just say nothing now."

So she pleasantly accepted the sub-lieutenant's offer, and while the crew of them got into his picket boat, the other picket boat took over the submarine for examination.

"We thought you were a whale," said their pink-cheeked host, "that had got touched up by somebody's propeller. I can tell you you made no end of a swirl. Nasty, stuffy things those under-water boats I should think, aren't they? Here we are at our ladder. Just excuse me a moment while I go and report to the skipper, will you?"

With dry mouths and strained faces they watched that young officer tread briskly along the lit white decks, and speak to his superior officer; and as the pair of them talked, the crew of the submarine overheard scraps here and there—possibly because they were intended to overhear them. "Meant for us sure enough, sir Whitehead ready in the tube. Saw it myself when she lifted Couldn't be rough, you know, sir, because of the lady. Devilish good-looking."

the crew of the submarine overheard scraps here and

there—

possibly because they were intended to overhear

them.

"Great thing is not to make martyrs of them, you see. So we'll just ignore the whole thing. Pass the word to the chief engineer to go and pick up all the tips he can from their infernal machine, and then scuttle her."

"Men might talk ashore."

"I'll stop all leave if necessary. Here, come along and introduce me to the lady."

So presently Captain Kettle, with the dazed O'Hagan, Burke the one-eyed, a defiant Miss Ffrench, and a very grimy crew, found themselves surrounded by affable naval officers, who talked on the most ordinary of topics, and utterly refused to accept the idea that there had been anything like tragedy even in the air.

There had been no damage done really, and Captain Kettle had earned good wages, but he was wondering as he drank whiskey and soda in that war-ship's hospitable wardroom, whether he could ever forgive the injury done him by comely Miss Ffrench.

But he felt grimly pleased at the conspirators' punishment. Nothing could have wounded them more deeply than the knowledge that everything practical about their painfully made boat would henceforward be the property of the hated British Navy.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.