RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Captain Kettle, K.C.B., 1903,

with "The Tail-Shaft"

IT speaks volumes for Captain Kettle's destitute and desperate condition that he should have accepted such a position at all. Indeed, to his peculiarly masterful mind, the degradation of it was more apparent than it would have been to a weaker man. But he had no choice. Walpole, the agent, was brutally frank upon the matter.

"My dear Captain," he said, "if you want the billet you must swallow the conditions. It's no particle of use your trying to stand on your dignity, and if you still intend to I must ask you to do it outside this office. I'm only an agent in the matter, and I've been bullied down the cable by the owners till the worry of it's brought on my old fever again. A white Englishman isn't intended by nature to be badgered to this extent during the summer months in Tunis."

"I'm sure I feel for you, sir," said the little sailor. "I know from my own experience that steamship owners can be very trying sometimes."

"Well, we won't discuss that, Captain. The question is, are you going out as skipper of this Ashville, or am I to wire around the Algerian ports to pick up some other man who holds a master's ticket? You must not think I'm cornered because just for the moment you're the only available skipper in Tunis. The boat is losing money, of course, by staying in harbor here, with her wages and grub bills, and all her other expenses running up, and I pressed that point forward, and only got snubbed for my pains. I'm to get a skipper who will consent to act under the mate, and if time is lost in finding such a man, it is no concern of mine. The owners seem to know what they are doing. I guess they've a notion they can trust the mate, and I don't blame them. You know as well as I do, Captain, the sort of pirate an out-of-a-job skipper at a place like Tunis generally is. It's seldom he's over-brimming with excellences."

Poor Kettle flushed painfully under the tan. "They're a set of drunken brutes for the most part, sir."

"No offence to you, Captain, of course, though I was told pointedly of one or two little games you've been up to since you've been in this colony, and I must say you've got a gallows-bad reputation among the French here."

"I think it's an Englishman's duty, sir, to keep his end up with foreigners wherever he may be."

"Yes," said Walpole ambiguously. "I fancy you're just the type of man that keeps up our dear country's reputation. Come now, Captain, about this Ashville?"

Kettle stared round the bare whitewashed walls of the office, and moved uneasily in his chair. "I suppose there's something wrong with the mate, too, or they'd have given him command, as they seem so fond of him? It's the usual thing, too, to promote the mate."

"Kelly, the mate, hasn't a master's certificate, and I should have thought you might have guessed that." Mr. Walpole fanned himself with a palm leaf, and spoke with growing irritation. "The late skipper came in here mad drunk, steamed his old packet up full speed across the lake, nearly washed away the walls of the dredged-out fairway, sank a lighter, and would have run down the quay, if only they hadn't mutinied in the engine-room and stopped her way for him."

"Well, I will say a man like that deserves to be fired."

"Oh, the owners weren't vindictive. They'd have taken Captain Carmichael on again. I had instructions to pay all fines and damages, and get him off to sea again as soon as possible. But I will give the French credit for knowing how to tackle a case like that. They know a bad man when they see one, and they keep a man of Carmichael's sort safe in jail. They gave him three years. It doesn't matter a sou to them how long the steamboat is tied up here eating her head off. They just won't give any clearance papers till they see there's a man on board holding a master's ticket."

"No, for that matter you must carry a man with a full certificate if the insurance policy isn't to be voided. The underwriters see to that."

Mr. Walpole started slightly. Was this little sailor hinting at something? Well, he was going to indulge in no confidence with a waif from a Tunisian slum. He tapped the writing table sharply with his fan. "Come, now, Captain, I'm a busy man, and we've wasted more than enough time already. The wages are £14 a month. Do you accept?"

"Yes, sir."

"And it's under the distinct understanding that you are under Kelly's orders."

"I give you my word for that, sir."

"I'm glad to have it. Not that it matters particularly. As you will find for yourself, Captain, Mr. Kelly is a big lump of a fellow, who could put you in his waistcoat pocket if you turned up awkward with him."

"I'd love to see him try it," said Kettle unpleasantly. "I'd like you to understand, sir, that I've tackled some of the ugliest toughs that ever carried a shut fist in my time, and size isn't a thing I take into account. If Mr. Kelly treats me respectfully, he'll find no officer more easy to get on with. But, by James, if he tries any handling games on me, he'll find his skipper a holy earthquake."

"Ts-ts," said Walpole, half to himself, "that's just the character I heard about you. Confound it, man, why do you want to take offence where none was intended? I only wanted to give you a civil hint. I'm sure that if you only do your duty quietly, you'll find Kelly quite pleasant and easy to get on with, and you'll have as nice a run out to Brazil as a man could wish for. The only thing I know wrong about Kelly is that he's half mad on the subject of some patent medicine, Kopke's-something-Cure it is, and rams its virtue down your throat on every possible occasion."

"I know my duty as shipmaster, and I do it exactly."

The agent tapped Kettle gently on the knee with his palm-leaf fan. "The great thing for a ship-master to do is to find out his owners' wishes, and carry them through. If he does that, he gets extra pay, and perquisites, and promotion."

The agent clearly wished to convey some hint. But Captain Kettle refused to unbend. "I have been accustomed, sir, to have my owners' instructions given to me direct, either verbally or in writing. Of course, away from home an agent stands for the owner. If you have anything to say to me, sir, it shall have my best attention."

Mr. Walpole slammed his fan down on to the writing desk and took up a pen. "I have nothing further to add, Captain. If you will permit me to say so, you are a complete stranger to me, and your manner since you came into this office has not been such as to invite superfluous confidences."

Captain Kettle stood sharply to his feet, and swung on his cap. "I bid you good morning," he said, and walked out.

For a minute he stood there and hesitated, and his eye travelled over the new white French buildings which lined the street. The sight of them sickened him. Out beyond the town walls was a hill, irregular with the quaint monuments of a Moslem cemetery, and beyond again, under the aching blue of the sky, was Africa, full of a million possibilities.

There never was such a climate as that of Africa for breeding schemes full of the most brilliant promise. During his recent residences, both in French Tunis and in the native city above, he had been offered partnership in ten such schemes for every day. He had dabbled in several till he had arrived at the point which proved them barren. But to make money out of any of them was beyond the power of sorcery. How he had lived even on their meagre proceeds was a mystery.

Just then, too, money was for him a crying necessity. A mortgage pressed like some horrid incubus on the farm in Wharfedale, and the interest was long in arrears. It was only by courtesy that his wife and daughters had not been long since evicted. If it had not been for that, he would have tried again at some of these African ventures. But the risk of them was too great. From this steamer berth he could touch his advance wages at once, and these, if sent to England, would tide over present difficulties. It was only his pride and his own tastes which stood in the way. He cursed these sharply, and strode off down the tramway lines toward the coal dust and the quays.

The Ashville lay stern-on to the concrete wall, and a gang plank with a flimsy life-line gave passage over her counter. The little sailor stepped briskly; up, and stood for a minute on the poop, looking around him with vast disgust. On the hatch of the main deck below him, under a ragged temporary awning, four deck hands sprawled on the warm tarpaulins and wrangled drearily over some dirty cards. In the alleyway an engineer in pajamas discoursed music on a mouth-organ. On the bridge-deck above a couple of well-curved hammocks exuded the tobacco smoke of complacent idlers.

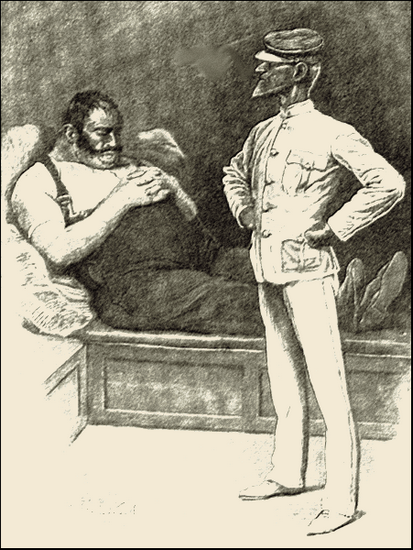

Kettle ran down the poop ladder, crossed the main deck, and went up to the chart-house with his quick, springy stride. The chart-house was closed by its wire mosquito door, and from within came heavy laboured snores. Captain Kettle stepped inside and beheld in singlet and trousers a man, enormously fat, asleep on the settee. He was packed with pillows almost to the sitting posture, and even with this relief his face was blue, and his breathing stertorous.

Captain Kettle stepped inside and beheld in singlet and

trousers a man, enormously fat, asleep on the settee.

The little sailor knew well the symptoms. "H'm," he commented. "You aren't built for this hot climate. And by that blue mug of yours your heart's bad, anyway. I guess waking you will be a kindness."

The sleeper opened his eyes at Kettle's touch, and shuddered flabbily.

"I suppose you're Mr. Kelly, the mate?"

"That's my name and grade." His voice was curiously high and weak.

"I'm Captain Kettle, that's just been appointed here as master in place of Captain Carmichael. I suppose the second mate must have been acting as mate while you've been temporarily in command, and I must say he's backed you up very badly. The packet's like a hog-pen to look at; some deckhands have got a card party on number four hatch; and a brace of dirty firemen are siesta-ing in hammocks on the bridge deck."

"I suppose there was nothing further for them to do. We've been in harbor here some time."

"That doesn't matter. By James, what's this second mate—that's been acting mate—made of? By James, doesn't he know enough to make work for the hands, even if there isn't work? I've seen hands turned to at chipping and burnishing chain cable if there was no other way of keeping idleness out of them. It strikes me as being about time that young man stepped back to his proper job again, and had you above him once more as mate, to show him what a mate's duties really are."

The fat man helped himself to a drink of water from the top of the wash-stand, to which he added some drops from a bottle bearing a patent medicine label, and then he turned round with a hand in his breeches pocket.

"I suppose Mr. Walpole, the agent," he said in his high, weak voice, "pointed out to you that the owners wished me to have practically the entire management on board here?"

"He did. But at the same time I was led to understand that, barring that you had the misfortune not to hold a master's ticket, you were perfectly competent for everything else in the way of duty."

"I see. And as it is?"

"As it is, I've seen for myself what sort of discipline you keep. You've no sort of command over your crew. If you wanted any of those hands to do anything, he'd have to wake up first, and then he'd think, and then nine to one he'd refuse."

"Oh," squeaked the fat man. "That's your idea? Well, different people have different ways of carrying on discipline. For myself I don't believe in hazing my hands. When there's work to do I see they do it; but when there isn't, I let them stand easy. I've no use for a burnished anchor or shined-up wire rigging. But when I want a man to do anything, don't you make any error about his doing it. The hands here know me. They take it as an axiom that I always cover them before I give an order."

"That's more than I should do."

"Well, Captain, I'll tell you in confidence that I've no use for a rough-and-tumble. My heart wouldn't stand it. And when you came in here, you looked like war, and so I took the liberty to make ready for you." He nodded down at his trousers pocket, and by a movement of the hand concealed there, showed the outline of a revolver which kept it company.

"Ah," said Kettle with a shrug, "if you contrived to hit me."

"I'm not without practice, Captain. I had to down one swine in the Bay not ten days ago for refusing duty. Got him in the hip bone in one shot. You can see the patch I've had to put on the cloth where the shot came through. The rest of the crew turned to like lambs when they saw him drop. There's some that clap a pistol to a man's head, there's some that shoot from inside a jacket pocket; but for real daunting effect I believe my way of loosing off from inside your trousers pocket beats anything that's ever been yet invented. They never know when you're laying for them; and as a consequence it smashes their nerve, and they just obey orders like so many school kids."

"Well, Mr. Mate, it appears I've misjudged you somewhat, and I'm open to apologize. Not that I think you could have fetched me with a down-wrist shot like that, before I could have blown daylight into you. I carry my own gun in the old-fashioned, respectable hip pocket, and practice has made me pretty nippy in pulling it. But, Mr. Kelly, I agree with you that yours is a good enough way of getting respect with a crew, and if under those circumstances it doesn't hurt your eye to see the old packet look like a hog-pen, I've nothing more to add. There, sir, that's for you, and I may say it's not my habit to apologize like that very frequently."

"I'm sure, Captain, you're treating me handsomely. I've whiskey here. I'll just order steam for you by your leave, and then we'll have a peg, if you don't mind, to our better and more pleasant acquaintance."

If Captain Kettle had taken to a certain extent the measure of the mate, Mr. Kelly had grasped with considerable accuracy the character of Captain Kettle, and formed his behaviour accordingly. The crew were turned to at the ordinary affairs of shipboard, and by the time the Ashville got her clearance papers and pilot, and cast off from the bollards on Tunis Harbor quay, the click of an iron discipline had spread itself fore and aft. She steamed dead slow down the putrid lake, between the festering walls of dredged-out filth, and reached Goleta and dropped her pilot, and then with the lift of clear green Mediterranean water beneath, drew away from that coast of many histories, and rolled off on her own mysterious errand.

The cabin food was good; the Captain's steward was a man of brain and taste; and when at last he had seen his vessel free of the land, and was able to go down for supper, Kettle had a second cut at the salt beef, and a third spoonful of the dry hash, and a fourth cup of the black well-boiled tea, and afterward said a new and elegant extempore grace with peculiar unction. It was many a weary month since he had tasted a meal which so entirely tickled his palate.

He was impressed, too, with his moral victory over the mate. He had never had an officer under him more observant of the dignity due to a ship's titular head, and, when it came to the point, he had seldom come across a mate, who, when he chose, could so satisfactorily drive a crew. Every morning the rising sun was greeted with the thump of holystones and the swish of hose and sand. The steamer began to carry with her always the cleanly odour of new-drying paint. So what with this pleasant scent in his nostrils, and the sight of gleaming brasswork and snowy decks, Kettle's senses were lulled with a kind of beatific, enjoyment.

Still, with all that, on the rare occasions when the fierce-eyed little man offered to unbend, which even the strictest of ship-masters may do at times to an elderly and competent mate, Mr. Kelly maintained a respectful reserve. Walpole, the agent ashore, had hinted at instructions given by the vessel's owners, first to Captain Carmichael, and then to Kelly, and Kettle, who was earning the owners' pay, and so was full of loyalty to these owners, had a natural wish to know the trend of their instructions. He hinted and hinted to this effect, but the fat, blue-faced mate would never unbosom himself; and when finally he put his question with blunt openness, he was met with an equally blunt, though respectful refusal.

"My orders, sir," said Kelly, "were given to me in confidence, and you will see for yourself that without further orders, I cannot hand them on."

"Right," said Kettle, and reached for his accordion. "That clears my conscience, and if anything is done on this steamboat against owners' wishes, it's their funeral. My theory is, Mr. Kelly, that when a master's drawing pay, he's bound to carry out the orders of those that are paying him. But if lie gets no orders, he just does what he considers right and shipshape. We'll drop the subject now, please, and if you choose you may listen while I give some music."

The Ashville called in at Grand Canary and coaled at Las Palmas, and then running south about the island, stood across the greater ocean for Santos in Brazil, her first American port of call. The lips of Kelly, the mate, were more blue than ever, and his neck was thicker, and the veins of his forehead were more congested. A minute's exertion left him almost breathless. But he stuck to his work with a stolid pluck which Kettle could but' admire; and though at times fright at his own condition showed itself plainly in his eye, he never complained.

Kettle, with a sailor's fondness for drugs, had overhauled the ship's medicine chest as one of his first exercises on board, and himself had sampled many of its contents. More than once he had offered a dose to the mate, particularizing the mixture which he felt sure would do him good. But Kelly swore by Kopke's Competent Cure. He had come across it, so he said, in a moment of desperate need; had found from the advertisement that his complaint was one of the many which it made a specialty of curing; and had stuck to it ever since with the most encouraging results.

He was a dull man, the mate. He was a man pressed down by ill-health and the dread of sudden death. But there was one subject he could wax enthusiastic over, and that was the Competent Cure. He could quote the literature supplied with the bottles with fluent accuracy. He was as ardent in finding converts to Kopke as ever Kettle was in collecting adherents to the lonely creed of the Wharfedale Particular Methodist Chapel.

So matters went along, then, on the Ashville, even-gaited as one may say, till Teneriffe, which was the last land of the Canary Islands, had sunk four days beneath the sea, and then the accident occurred which made her voyage memorable. It arrived a bell after the watch had been changed at midnight, and announced its arrival with a crack, a crash, a bump and a jar, a noisy shiver of the vessel's fabric, a wild whirring of engines, all of which were scaring enough, and then a moment's absolute silence, which was the most awe-raising of the whole lot.

Captain Owen Kettle was lying on his bunk in neat pajamas, smoking a moist black Canary cigar, and wrestling with a reluctant rhyme. Three well-turned verses stood to his credit on the writing block in neatly pencilled lines. He had the sentiments of the fourth verse securely in his head; it tripped merrily to his favourite tune of "Greenland's Icy Mountains," but it was coy of delivering itself in exact metre. But at the alarm he slipped paper and pencil under the pillow of the bunk, and was outside the chart-house and on to the upper bridge well under five seconds.

Both mate and second mate were there already, the former almost choked with his hurry and his emotions. But to Kettle's trained intelligence there was no need for a special report. The quietude of the propeller, and a few light clouds of steam billowing up from the engine-room skylight, told him where the trouble had occurred, and the rush of water from somewhere below hinted at its gravity.

"She's by the stern already," gasped Kelly in his high, unnatural falsetto.

"An inch or so. But listen to that squeak. That's one of the engineers screwing down the watertight slide over the shaft tunnel. It'll be a section of shaft that's gone, but whether it's the tail or the intermediate has got to be seen. We shall have a sweet job mending it."

"Mending!" screamed Kelly. "There can be no question of repairs out here. It is out of all reason. Besides, she is settling down already. There is no chance of a tow either. We are out of all steamer tracks. I tell you she is settling down now—look. We must get the boats into the water and desert her before she swamps with us."

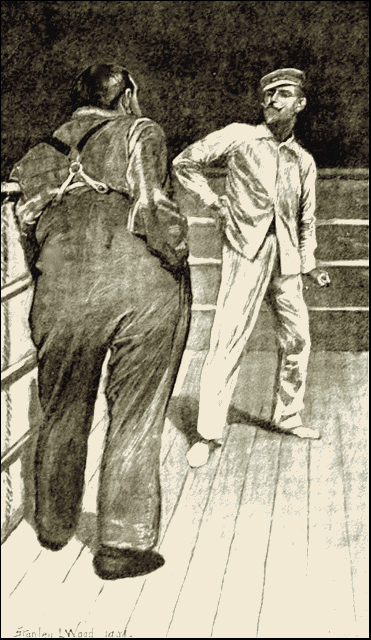

Captain Owen Kettle glared at the mate, and swung a hand round to his hip. The mate, with heaving chest, hung on the bridge-rail with one arm, and kept the other gripped on something in his breeches pocket. They were within an ace of some very rapid shooting.

Captain Owen Kettle glared at the mate,

and swung a hand round to his hip.

But Kelly was clever enough to appeal to the only plea which could have saved the peace. "You promised!" ne cried. "The final say of everything connected with this steamboat is to be mine, Captain. You passed your word, and if that's not all canting humbug that you've said about your chapel and your faith, you'll keep it."

Kettle slipped away the threatening hand, and crammed it out of temptation's way in his pajama pocket. "If you are acting just now on owners' instructions," he said pointedly, "you'd better tell me what they are, and I'll help to carry them out. I'm earning owners' pay, and am open to doing what they hire me for."

"I can tell you nothing. I dare tell you nothing. My last word is that the old packet is sinking, and there is no chance to repair her, and no chance of being picked up, and we must leave her in the boats. Ah! here's the chief. You'll see he'll confirm what I've said. There's no chance of repairs out here."

The old chief engineer came up to the bridge and made his report. The tail-shaft had cracked and parted. The engines had raced badly before they could be stopped, but had done themselves no serious damage. No one was hurt, although there had been some narrow escapes. He was blowing off steam now. "A tidy sup of water got into my engine-room before we could get the shaft tunnel cut off with the slide door," said the chief, with gloomy triumph. "I always said that the worm gear we have for shutting off shaft tunnels worked too slow, and I brought out a patent once for a quicker motion. But none of the firms I offered it to would take it up, and I lost my own bit o' capital by trying to run it myself, and that's why I'm here to-day instead of riding in a motor car of my own on shore. It's a fine satisfaction to me to be able to tell from my own experience—"

"Yes, yes, Mr. Brodie, that's all right. But what I want to know is, can we, in your opinion, repair her?"

"We-e-ll! if it's repairs at sea ye talk of, it would be very difficult—"

"There!" screamed Kelly, "I knew! We are wasting time. She is settling down under us. Captain Kettle, I remind you again of your promise, and bid you order me at once to get out the boats."

Old Brodie permitted himself to deliver a small whistle of surprise.

Kettle felt it due to his honour to explain. "Mr. Brodie, I wish you to understand that the mate is in virtual command, in accordance with an agreement which I made with Mr. Walpole, the agent, in Tunis. That is for your own information, and not for a court of inquiry, if ever we come to one. I never sailed in such a humiliating position before, and never shall have the chance again if ever we get ashore and this is looked into. The dirty business will cost me my ticket as sure as James. Mr. Kelly, you may get those blasted boats into the water as quick as you jimmy well please."

News of this kind quickly spreads. Out from the forecastle doors trotted deckhands, firemen and trimmers, each with a bag that was swollen with his scanty wardrobe. The officers, whose effects were insured, took care to provide for a new kit by bringing nothing.

The steamer fell off into the trough of a good strong Atlantic swell, and roared steam through the escapes as though her boilers pained her. The men climbed to the top of the fiddley and threw themselves at the boats. They ripped off the awnings, pitched out the falls, cut the gripes, kicked away the chocks, and then packed in their valueless bundles with care and thoughtfulness. Afterward, with a vast amount of getting in one another's way, they set about filling water breakers, and laying hold of victuals.

Except for the cook and the captain's steward, no one in the least seemed to know where anything was stored. The mess-room steward, who might have helped, had got at the second engineer's whiskey bottle, and had quickly reduced himself to such a state that he could contribute nothing but incoherencies and music. The other two were dazed, had not enough initiative to act without orders, and ran about from place to place, not knowing what to start on first. There was nobody to order, nobody to guide, nobody to drive.

The confusion was amazing, and notwithstanding the fact that there was not the smallest immediate danger of the vessel sinking beneath them, something very like a panic began to grow, and quickly spread. Captain Kettle, the nominal commander, did nothing to check it. He perched himself on a white painted rail of the upper bridge and smoked and waited. He had had his lawful authority rudely plucked from him by the mate, and, in his fierce little mind, it seemed to him only bare justice that the mate should take over the hard part of the command with the soft.

He watched Kelly carry his purple face about from place to place, squeaking, threatening, gasping for breath. The men took small enough notice of him. The other officers, seeing that there was something wrong in his relationship with the Captain, backed him up very half-heartedly, and in consequence there was chaos, which Kettle grimly enough set down as a compliment paid by justice to himself.

Then panic bit deeper, and one of the lifeboats filled with men, too maddened with their sheep-like scare to think of their utter lack of provisions and the thousand miles between them and the nearest land. They swung the davits outboard and lowered her. Other men leaped on to the tackles and swarmed down into her. Kelly rushed at them, beating furiously at their heads with the stock and trigger guard of his pistol.

"You fools!" he screamed, "you frightened fools! There are plenty of other boats." Then he gurgled, and then breath failed him, and he fell in a slack heap and twitched feebly.

It was at this point that Captain Owen Kettle interfered. He clapped a hand on to the bridge rail, and vaulted lightly over on to the fiddley. He went to the mate's side, and made a quick diagnosis. "Apoplectic," he said, "and any one could have guessed it was coming from the mere look of you. You knew it yourself, and what drugs could do, you did. But I guess you are booked past Kopke this trip. Here you, and you, take the mate down below to his room."

The two men he had spoken to turned with frightened scowls, and showed every inclination of disobeying their Captain's orders. (Kettle, be it remembered, was small to look at, and, so far, on board the Ashville, had not shown that he was otherwise than small in either power or ability.) But of a sudden these two men found themselves gripped by two very capable hands, and their heads were knocked violently together, and then furious attacks were made upon them with foot, fist and tongue, till out of sheer terror and pain they picked up poor Kelly, and carried him below as commanded.

Of a sudden these two men found themselves gripped by two very

capable hands, and their heads were knocked violently together.

"Hold on with all those boats," was Kettle's next order, and as the panic-stricken mob showed no inclination of listening to him, he picked up an axe and stove in one after another. "By James!" he shouted, "if any of you swine think you can navigate the South Atlantic on a ladder you may go, but otherwise you'll stay on this packet till I give you leave to quit."

One boat only reached the water and pushed off, and this was the unprovisioned, over-loaded life-boat which had left the davits before Captain Kettle interfered. Three men pulled at her oars. Two baled with boots and one with a bucket, and it was plain to see that the water gained on them.

Kettle hailed them. "Here, you in that starboard lifeboat! Come back here out of the wet. You dirty coal heavers, you no-sailors, your boat's swamping. Come back here before you drown."

"By crumbs," cried one of the lifeboat's crew, "the plug's out, that's why the bally boat's sinking. Here, give me a thole pin, and I'll whittle that down into shape."

Captain Kettle lifted an accurate pistol, and from his perch high above the boat, drove a bullet through her floorboards. "There's another hole for you. Now let me see any swine try to plug it and I'll drop him. Here, you at that steering oar, turn her head in to those falls, or, by James, I'll make a vacancy for a new coxswain. Give way there, you tailors!"

The boat drew in to the Ashville's side, hooked on, and Kettle sketched patterns over her crew with a revolver muzzle. The boat was lifted, baled, and hoisted up to the davits.

The stolid, elderly Mr. Brodie, seeing the way things were going, had lowered himself over the counter by a rope's end, had swung on to the rudder pendants, and from that unstable point of vantage had made a survey of the wreck. By the time the boats were inboard again and secured, he had made his way up to the bridge once more, and stood there exuding seawater, ready with his report.

"Well?" said Kettle, "could you see the damage plainly?"

"The water's as clear as gin. The tail-shaft's in two half way, and the outer end's just dropped clean out of her."

"Where's the propeller?"

"With the shank of the tail-shaft. I don't know what are the soundings here."

"About two miles, as near as might be," said Kettle grimly, "so we shan't anchor. We shall drift. If you want to know how long we shall drift, it will be just the time you take to get her under steam again. I see by Captain Carmichael's lists that she carries a spare section of shafting and a spare propeller. I want them shipped."

Brodie shook his head. "Contract too big."

"Not for me. If you don't see your way to making those repairs at sea, I'll show you how."

"Look here, Captain, I'm a fully qualified engineer, and I don't need teaching my business by anybody."

"My man," said Kettle acidly, "if I'd the Emperor of Germany on board here as an officer of mine, and he didn't do his job exactly as I wanted, I'd teach him, tough nut though he may think himself. Now you aren't the Emperor of Germany by a long fathom."

"What's striking me is, do the owners want her brought home again?"

"I fail to see why not. She's a valuable steamboat."

"Well, Captain, in your ear, I've a mind that that tail-shaft was as sound as a bell, and somebody's helped it in two with a few cakes of gun cotton."

"Nothing to do with me."

"Oh, of course, sir, if you understand the owners' wishes, I've nothing more to say."

"Mr. Brodie, I've asked for owners' instructions from two people, and they have both flatly refused to give any. Half an hour ago some one else was in command of this packet. But it seems that I'm skipper now, and by James, I'm going to be it, and act just as my conscience dictates. If they'd treated me openly they could have found no more obedient servant on all the seas. But I'll teach the beggars I'm not the man to be suspicious of."

Forthwith the Ashville became a very inferno of activity. Her crew worked with frantic energy, impelled thereto by the example and the fist of Captain Owen Kettle; and steam, and every mechanical device clever minds could contrive, seconded their efforts. The ponderous length of spare shafting was got out from below, and lay on the quarter deck, rusting under tropical sunlight. A great propeller was brought up and laid beside it.

Meanwhile clacking bilge pumps had cleared the engine-room of water, and opened valves had let water into the false bottom forward. But that did not bring her sufficiently by the head. The after hatches were pulled off, derricks rigged, and the rattling winches struck out cargo which was carried forward and built up on the forecastle head. The Ashville was taking out machinery—so her manifest said—and the machinery in its massive wooden cases made desperately heavy loads to carry along the reeling, uneven decks of the steamer.

But as her head was depressed, and her stern lifted higher, the vessel began to swing like a vane head to wind, and when at last her stem was almost buried in the seas, her sternpost was sufficiently lifted to show the shaft tunnel clear of the water.

Then began the heaviest labour of all. From the steamer's meagre spars, shears and a staging had to be erected over the stern, and tackles set up which could handle enormous weights. So far the work had been hurried on at full pressure under the glare of an equatorial sun by day and to the dazzle of arc lamps when the sea was covered by night.

The Ashville was provisioned only for the run between Las Palmas and Santos, and undue prolongation of the passage spelt starvation. Indeed, the slender Board of Trade "whack" had been halved from the very day of the smash. But when the shears were erected, the steamer bucked for three whole days over a ponderous swell, and work on repairs was entirely out of the question. There was nothing for it but to sit and wait, and watch starvation grow more unpleasantly near.

The crew at that time wished to repair the boats. But Kettle would not let them be touched. He had pinned his honour and his reputation on making good the damage, and bringing in his vessel under steam, and he knew that nothing short of desperation could bring this to pass. If, when it came to the final pinch, his crew saw any other way of escape, they would take it in spite of his pistol and all his teeth.

A calm came at last, and the gaunt, sun-scorched men attacked the work savagely. The ship's stores were slender, and the wrecked tunnel in which most of the work had to be done was desperately narrow. But they knew their trade, and toiled at it with skilled sinews. They removed the length of shaft next the tail-shaft from its bearings. They withdrew the broken section into the tunnel, handling the great masses of metal with tackle contrived as the occasion arose. Then they put the new length into the stern tube until its nose was just showing outside, and lowered the propeller into place. Next they jacked aft and home the tail-shaft, told off half a dozen men and an engineer to screw home the ponderous lock nuts, and even made a lignum vitae bush for the stern gland. After which the weary work of shifting cargo was again gone through, till she was once more in her ordinary trim.

Then Brodie descended to his engine-room, and "took a turn from her."

It would be flattering to say that the result was anywhere near perfection. There was a grating and a groaning, and a rumbling like a railway train going over an iron bridge. The whole steamer shuddered as though the operation pained her. But, as the old chief said, the main thing was, they did go round, and the propeller seemed inclined to stay where it was put, and he on his part was ready to guarantee seven knots when the forward tanks were emptied, and the cargo brought aft again, and the vessel's stern brought into trim.

A liking had sprung up between Kettle and Brodie during this fierce spell of labour, which led them into mutual civilities when once more the Ashville was moving steadily on toward her port in Brazil. Each, too, had a sailor's taste for drugs, and they discussed with much serious argument the virtues of Kopke's Competent Cure.

Kelly, the mate, had left behind him the wrappers of several bottles of this specific, and the two read these, and based upon them many ingenious theories. Kettle held that Kopke must have virtue, since it had obviously kept the mate alive long beyond his time. The engineer, strong in faith with an opposition patent medicine of his own, held, that though Kopke was good for the lungs and indigestion, it was valueless to succour a damaged heart. Each adduced the case of Kelly in support of his contentions.

"Well," said Kettle, at last, "I wish the poor chap could have spoken before he died, just to tell us. Besides, I think it was only due to Kopke that he should know. But as it was, the mate never got out another word after the apoplexy struck him."

The engineer scratched his nose with a black thumbnail. "If Mr. Mate could have talked, Skipper, I think he might have handed on as a last gasp those owners' instructions that you were so keen on getting."

"There's no telling. When a man's pegging out, it's quite a gamble what he talks about. Some think of their wives, some of kids, some of the last ra-ta they had ashore."

"Then I guarantee Kelly would have fetched up those owners' instructions. He had a wife ashore, and kids. I knew 'em. And his last little ra-ta on the mud was his own bankruptcy. I don't know the owners' instructions, mind you, but I can make a hard guess at them, and they would all have connection with those other three things you mentioned.

"I'm just dead certain that he and Carmichael were set on to see this ship never got to Santos at all. Carmichael weakened, and took to the whiskey, and got into trouble at Tunis, as you know. Poor old blue-faced Kelly hung on. I've had my suspicions all along. I'd more suspicions when that shaft went. I heard gun cotton then, I smelt it, too, and I swear the shaft wouldn't have parted if it was treated fairly."

"Is there anything to prove that?"

"No, everything was blown conveniently away. But wait a minute. What were those cases filled with that you struck out of No. 4 hold?"

"Machinery. I thought of that myself. But you're wrong. They weren't filled with bricks or anything like that. Two or three of the cases broke, and I saw the machinery for myself."

"So did I. But here's where the expert comes in, Skipper. They were looms and spinning frames, and old ones at that. They were only fit for scrap. They weren't worth more than two-and-six a hundredweight. Now, play on that."

"I don't want to," said the little sailor. "I've had my suspicions all along. Mr. Walpole, the agent in Tunis, let me see there was something wrong, but he wouldn't say what it was. Kelly was the same. And there are these other things. But I'm accustomed to being trusted, and I was not trusted here. Let an owner trust me, and I serve that man faithfully so long as I've hands, or wind, or tongue left to me. But if I'm sent on board with somebody else in authority over me, and that somebody else is removed, well, then they may look out. I just play the game of simple honesty."

"I'd do the same if I were in your shoes. It's time somebody made owners like those sit up. But there's one other thing. They'll fire you by cable in Santos. I don't know whether it matters to you?"

"It matters everything. I must have employment. I must. I've a wife and daughters on the farm at home in tremendous difficulties. But I don't think I shall lose my present job over this. My duty is to the owners first, of course—when I know what that duty is—but after them there's the British Consul to go to, and the next people to him are the underwriters. I don't think they'll fire me, Mr. Brodie. And finally, there's this—"

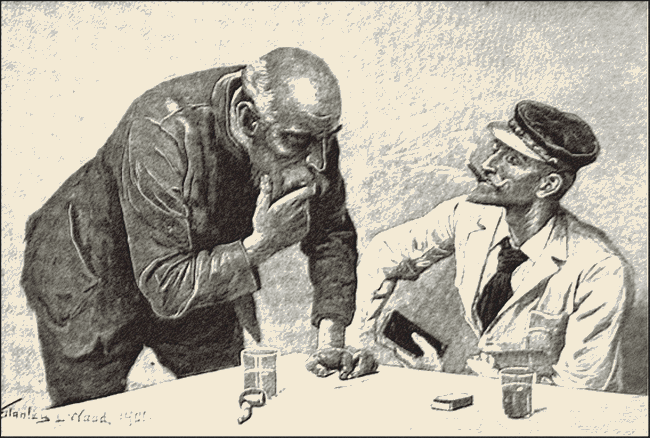

He took a small scrap of paper from his pocket-book, and laid it on the chart-table. Brodie leaned over and read it.

Captain Kettle took a small scrap of paper from his pocket-book,

and laid it on the chart-table. Brodie leaned over and read

it.

"We promise to pay to Captain Carmichael £6,000 for the loss of his clothes and effects if the "Ashville" fails to come into port."

And the signature was that of the steamer's owners.

"I found it," said Kettle, "in Norie's 'Epitome' on the bookshelf up there. Carmichael must have been pretty drunk to leave such hanging evidence as that loose in an everyday book. But with that ready to hand over to a Consul, I don't think the firm will fire me, eh, Mr. Brodie?"

"By the Lord, Skipper, but you're a great man. If ever I get that tunnel-slide patent of mine floated, I'll take you into partnership. You've got what's better than ordinary brains. You've got diplomacy. You can make trouble where any ordinary man couldn't see a cat's chance of it. By goats, you can!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.