RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Captain Kettle, K.C.B., 1903,

with "The Carthaginian State Reserve"

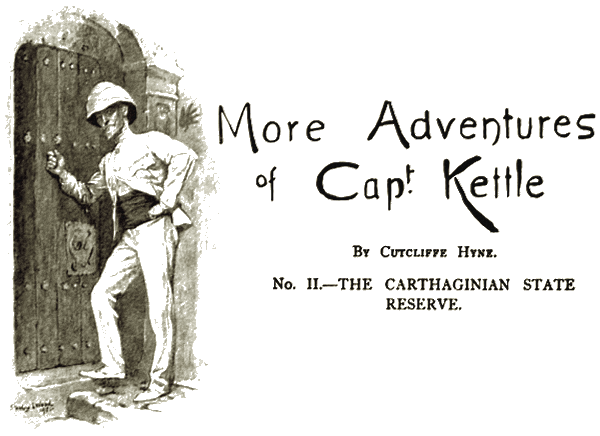

Rifle butts pounded against the iron-

studded door in the white-washed wall.

BY what particular process North Africa ejected Captain Kettle on to her shores at Tunis, the present writer has never been able to discover. He arrived by the afternoon train from Kairouan, which, as usual, gasped in an hour behind scheduled time. He travelled in a third-class carriage, which is in itself a finger mark to destitution in a European, and he was utterly divorced from luggage.

He was neat, of course, and clean, but his white drill clothes bore the marks of many careful mendings, and though his white canvas shoes were carefully pipe-clayed, they were frayed in places even past his skilful repairing. But his fierce little eye was as bright as ever, and his red torpedo beard was trimmed to its usual miracle of smartness.

He carried the appearance of a man newly returned from one of the Sahara caravan routes, where the day's ration of food is one handful of dates, and the water is scarce, and bitter, and alkaline. His waist was bound by the broad sash worn by camel drivers. His face was browned by outrageous suns. He was never a man who carried much flesh, but just then he was thinner than ever, and it seemed easy to read that it was the desiccating air of deserts which had left this mark upon him. But, as I say, that is only guesswork. Where he had been, what wild work he had been up to, are points carefully locked away, and no country is more competent than that part of North Africa between Lake Chad and the salt chotts south of Tunis to keep such secrets inviolate.

The city was plainly foreign to him, and for the moment almost alarming. He stepped out of the station precincts and narrowly escaped being run down by a jangling tram-car; French seemed the only language on exchange; and though there were dark faces and Arab draperies here and there, they had no air of being native to the streets. Electric arc lamps grizzled and glared overhead; and before the cafe affected by the soldier officers, a band played to an audience in uniform or rice-powder.

It was summer time, and after the tourist season; the crowds outside the cafes were almost entirely Latins; but there was one couple of sweating ship's officers there representing Great Britain, and these spotted him as a fellow countryman, and stared at him curiously, though with hospitality plainly lighting in their eyes.

But Kettle was in no mood for companionship then. He thirsted for whiskey, for good Christian whiskey with soda water, and (if Allah was very kind) ice. He had the aching thirst of the desert in the back of his throat, and the lust for a good hard smoke at a black cigar consumed him. But in his present state these things could only be given in charity, and he was not a man to take favours from anybody. He earned, or, at a pinch, might take; he would never beg.

He walked on to the French town, and passed through the Bab e Behira. A supercilious camel swung aside to give him passage. The smells of native Tunis came out warm and sour to greet him. He counted up the narrow streets which ran into the open space behind the gate like the sticks of a fan, picked out the one he wanted, and went along it at the increased pace of a man nearing a destination after long travel. He went up and up the steep cobbled lanes among the varying smells, past droning native cafes, and at last walked under the dark lid of a closed, unlit bazaar. Here for a moment he hesitated about his way, and asked a direction from a fez-capped nigger boy.

His knowledge of colloquial Arabic was enough to make an eye-glassed Frenchman who was passing turn and stare.

"Espion Anglais." this person muttered to himself, and pulled at a ridiculous beard that sprouted from the two corners of his chin. "The man's a Touareg he's asking for. Why should he want to meet with a Touareg here in Tunis? Espion Anglais! I will give information."

Now the eye-glassed man happened to be a journalist, and here was copy au moins, a scarce commodity in that hot, limp colony of Tunis. One would have thought that the English spy scare was a trifle overdone in North Africa, but at least it must be admitted that the journalist knew his business in a certain degree—seeing that he drew a livelihood from it. And anyway newspapers must be filled, and hard fact runs short sometimes, as even London and New York will admit.

Captain Kettle, however, went on his way through the narrow alleys unconscious of the attention he had received. He got out of these at length, and came upon a white dusty road leading toward the hospital and the outer walls, and lit bright by a luxurious African moon. Again it was evident that he guided himself by minute directions, well instilled. He wound unhesitatingly along his way, and presently stopped with confidence before a house.

According to Western ideas it was not an hospitable looking place. It presented to the passer-by a broad white slab of wall, level topped, and broken only by a door, which was small, low, and iron studded, after the style of a mediaeval castle. Kettle rapped upon it smartly with his knuckles, and, when this brought no response, set to pounding with the side of his shut fist. The house inside reverberated like a muffled drum. A man came presently to that summons, and after some scrapings of bolts the door swung inward. The man stood out in the moonlight, a dandified figure in red fez and mouse-coloured haik, and the first words he had ready for his lips were clearly not those of civility. But at the sight of a European—and such a truculent looking little European—he kept these back. "What does monsieur want?" he asked. "It is late for monsieur to be in this part of the city."

"Are you Mohammed Shabash?"

"I am sometimes called by that name."

"Then I have a message for you from your brother."

"Monsieur must have mistaken the name, or the house. I have no brother that monsieur can have met."

"Grant me patience! Do you think I've come all this way, and found the house, and found you, without knowing what I was about? Ali Akkerim is your brother's name, and I suppose you don't want me to shout it for all the street to hear? No? Then, by James, don't you keep me standing here like a cat on a doorstep any longer."

Kettle stepped inside, and the iron-knobbed door swung into place behind him, and was once more securely barred. The inside of the house was full of close heat, and the air was loaded with the heavy sweetness of attars. The house also gave up from its unseen recesses the silky rustle of garments; but Kettle affected to be deaf to these; he was well instructed in Moslem domestic etiquette by this time.

Mohammed led into the small cloistered courtyard at the back, in which was the usual orange tree hung with yellow fruit. There was a divan there in the moonlight under one of the arches, and Kettle noted as he stripped off his shoes, and sat among the cushions, that it was still warm from the impress of former occupants. He had evidently disturbed Mohammed Shabash from an evening's dalliance in the bosom of his family.

A low table in front of the divan held a jug of tepid syrup and a dish of cloying sweetmeats.

"Will you be satisfied?" said Mohammed Shabash with the usual formal hospitality.

"Thank you," said Kettle. "I've got a regular rasping hunger on me, and dessert will do for dunnage. But I wish I'd looked in before you sent away the joint. Where I come from lately they've got slim notions of what's a grown man's meal, and when you and I make our pile, my buck, out of what I've got to tell you, one of the first things I do after cabling home some cash to the Missis and the girls, is to have a skinful of solid beef and ale."

The master of the house stifled a yawn. "So you have been out there in the desert, have you, with the Touareg? They are savage peoples there. I have no interest for them!"

"You were born a Touareg, anyway."

"It cannot be denied. But fortunately I was taken in a razzia when a child, and brought here as an employee."

"As a slave, Ali said."

"The same thing. My master was an embroiderer, and I was brought up in the Souk e Sevadjin. I was lucky. My master had no sons, and in time the business came to me. I am enlightened. I have been to your Earl's Court for an exhibit, and also in Chicago. Oh, I am quite up to date. I do not work now. Others work for me, and in the tourist season I import embroideries direct from Hamburg and Bradford. Then I fray out a little thread here, dash in a little stain there, and you have the genuine antique which the tourists demand."

"I know the style."

"Then you must see, mister, how much you damage me by calling me a Touareg. I am no dam' savage. I am mos' civilize."

"You seem a queer nut anyway. You'd make that swashbuckling old Ali lift his eyebrows. But I don't like you any the worse for being a business man. It's a rare soft thing Ali and I are putting you on to, but it will cost a bit of think if we're going to pick out the plums for ourselves, and not have some French officials stepping in to find pensions that will take them home again. I say, did they keep this flat ginger pop on tap for you at Earl's Court?"

"No, mister. Whiskey soda. You like some? Of course." Mohammed Shabash clapped his hands and called out an order in his own tongue.

Kettle interposed hurriedly. "Excuse me, Mohammed, but don't bring out the ladies on my account. I am not asking you to do that amount of violence to your religious persuasion. A good square drink of the forbidden liquid will be quite enough."

"Oh, it is nothing. I am not prejudice. I am quite civilize. I will show you my women. I show them to the tourist on the quiet since my return from Chicago, and for money, you understand. But to you I will show them for nix. And I will join you in the whiskey and syphon. I drink it frequent. It is only accident you find that pigwash there instead. But we will not send it away. It will do for the women. I have fine women, fat and pleasant. You will not think of me as once a poor savage Touareg when you see my women."

"Well," said Kettle, "just as you like. I'm always ready to do the sociable when required. I see you've got an accordion down there. That's my favourite instrument, and there's many say that I'm no fool of a performer."

"I am most gratify."

"But I can't sing on an empty stomach. Did you say supper was coming on soon?"

"I will see what we can get, and I feel sure you will then play to us dance music, and my new wife shall step for us."

"I will even play for you dance music," said Kettle, with a sigh, "though, for reasons you would not appreciate, those tunes are very repugnant to me."

"What reasons? I like to learn."

"I am a stanch member of the Wharfedale Particular Methodists, and in a way was their founder, and we look upon dancing as only one degree short of blasphemy. Come now, Mohammed, you are evidently not much up on the Prophet just now. What do you say if you join our community? I could let you have all the points where we differ in a couple of days."

But if Mohammed was a lax follower of his own creed, he was not taking any conversion just then, however civilized such a performance might be, and he said so with a shudder, and some unnecessary warmth. It is probable that Captain Kettle would have flared up at having his offer on so tender a matter flung in his teeth; but at that precise moment a flabby eunuch brought in a row of old kybobs on a skewer, and Kettle was only mortal. He took the meat and held his tongue. To tell the truth the little sailor was near upon starving. Meat he had not touched for a month, and for the previous thirty hours not even so much as a date had come to his lips.

With these cold grilled lumps of mutton, however, inside him, and with a second good stiff whiskey and soda to keep them company, he was a different man. Three giggling, portly Tunisian women slopped in, with their toes tucked into varnished blue patent leather slippers four sizes too small for them, and two of them slouched on to the divan. The third stood before them panting expectantly. Captain Kettle, with a smothered groan, broke off from the hymn tune he was playing with such pleasant reminiscence, and squeezed out a profane jig with the full force of his instrument. He keenly felt the degradation of having to play such music for such an audience; but the needs of those at home held him by the heartstrings, and all depended on keeping this queer Mohammed Shabash in a reasonable temper.

The stout lady shuffled her absurd slippers, and swayed her body without any reference at all to the music, and her adoring husband was openly proud and delighted at her performance. The moonbeams threw a shadow of the dancer which wriggled like a grotesque toad on the flagstones of the courtyard.

The stout lady shuffled her absurd slippers, and

swayed her body without any reference to the music.

But exhaustion and the climate at length stopped the performance, and presently at a sign from their lord the ladies withdrew. Then Captain Kettle thought that the time had come to broach his business. "You have heard," he said, "of the treasury of Carthage?"

"Who has not? It has been looked for these five thousand years. First by the Romans, then by the Arabs and the other conquerors, now by these French. The French say they dig for archaeology; but it is not; they are hunting for treasury also. Still, there is no result. I do not believe there ever was a treasury; or if there was, it was emptied long before. I tell you I believe very little, mister. I am very civilize."

"Don't you be too knowing. Your brother Ali has learnt for an absolute fact that the thing was there. One of his mullahs found a whole account of it written out on some adobe bricks among one of those musty old ruins that lie peppered about the back country there."

"But still it may have been emptied. And, besides, who is to say where it is?"

"You don't seem very keen on putting together a pile in spite of your civilization. I've got a sketch plan here in my pocket. Three days' labour will prove whether the place is full or empty."

Mohammed Shabash stretched out his thin yellow fingers. "Mister, let me see."

Captain Kettle winked a knowing eye. "Better know where we stand first, my buck. This isn't all your pie. I've got a finger in it, and when my finger's in a pie, a large slice of it's got to be mine, or somebody will buy trouble."

Mohammed Shabash burst out into a querulous whine. "I declare to Allah I am a poor man. I demand that you give to me that which was sent by my brother Ali, my dear brother who lives free in the beyond, the only brother I have got."

"H'm! You weren't very up on the relationship five minutes ago. But there's no use trying that game on with me. Ali doesn't value you to the extent of a date stone. He told me so. He's sent you messages, and you've ignored them every time. He's not the man to forget a trifle like that. He gave me free leave to make use of you, or ignore you, exactly as I pleased, and I just come to you as being the only capitalist here in Tunis that I've got the name of. For myself," the little man added simply, "I've got my pockets full of fists just now, and it was a case of share or starve."

"How much do you want for your share? I will allow ten per cent."

"I will take just one-half, my buck embroiderer, on the one condition that you finance me through till we either grab the treasury, or make up our minds it isn't there."

Mohammed Shabash squatted back on his heels and raised a storm of expostulation. He was one of the smartest salesmen in the Souk e Sevadjin, and it stood to his honour not to accept an offer without haggling for a better bargain. But Captain Kettle sat placidly among the cushions of the divan and smoked without an attempt to abate his terms. "It's no use you trying your bazaar games on me," he said finally. "I know you aren't half ruined, and I've seen for myself that your family is in no immediate danger of starvation. My folks are, and they're the people I think of first. But blow off your steam if you find it a comfort."

It was late that night before the Touareg-Tunisian finally agreed to terms, and when Kettle said his prayers before turning in on the sleeping-mat, he gave thanks for victory over the infidel, and put up a petition for his subsequent conversion. "I prevailed over Ali, O Lord, to hear me at least with patience, and Ali has a hundred times more man in him to the square inch. Grant therefore, O Lord, that I gather this thing also into the fold."

But in the morning an unexpected trouble arose. Mohammed Shabash returned from the street of the embroiderers in a state of combined fury and fright. "What is this you have done to me?" he cried, with a gesture. "They say you are an English spy. The papers are full of it. They say you were inquiring last night in the Souk el Attarin for some one who was a Touareg, though in Allah's mercy the fools have not caught the name. Soldiers are in the bazaars asking who are Touaregs that the houses of all of them may be searched."

"Pff! Spy be hanged. I am no spy."

"That is no argument. They say you are: that is where the trouble lies. And if you are found here, there will be suspect for me."

"By James! if any of their silly red-legged soldiers come messing around me there will be trouble. By James, Mohammed, do they think because I'm new in from the back country I haven't got a gun? Why standing here in this half-window across the courtyard, even if they do smash in the door, I could drop every son of a dog that tries a rush before he gets through the archway. Don't you be afraid, my buck; your house shan't be raided while I'm in it."

Mohammed Shabash wrung his hands and danced in his absurd slippers. "You must not. It is strickly forbid to shoot or otherwise impede the soldiers. Besides, I am mos' civilize. I cannot afford to have my business disturbed by an emeute."

"Then do you call off your red-legged piou-pious."

"I cannot. You do not understand. There is great excitement always about spies. The Government approves. It promotes loyalty. Look, mister. I give you two choices; either you must go from my house and surrender, or you must go to my hide place. There is hurry to decide; they will be here presently in search."

The little sailor strongly objected to being harried by the officials of foreign Powers, and so it was considerably against his will he consented to seek seclusion; but Mohammed in his ecstasy of fright swore that if he resisted further, the whole story of the Carthaginian hoard should be made public. So the well-bucket in the courtyard was lowered a couple of yards and made fast; Kettle slid down to it by the rope, passing with difficulty through the upper aperture; but once under the coping-stone saw an opening in the wall, which, with a vigorous swing, he managed to reach. Here were sundry illicit stores, and among them he took his seat.

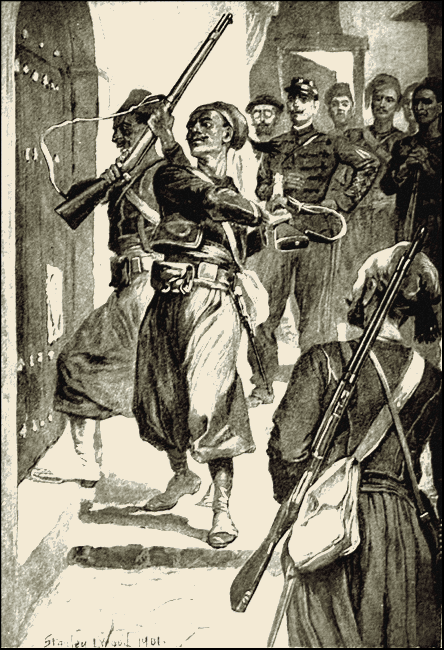

Once free of him the well-bucket whirred down the shaft and plunged into the water at its foot, and not five minutes afterward the genuineness of the scare was guaranteed very plainly. Rifle butts pounded against the iron-studded door in the white-washed wall, and when it was obsequiously opened, in rushed a squad of soldiery who spread about the house with ruthless industry.

With them was an eye-glassed French journalist with an absurd beard, busily taking notes. With them also was Mohammed Shabash, wailing at the damage done in one breath, cursing at the indignity shown to his women in the next, and at the end of each bar, blatantly protesting his unshakable loyalty to the mighty Government of France. And underneath in his dusty niche was Captain Owen Kettle fingering a revolver, and viciously wishing he could come across the individual who had arranged all this upheaval for his benefit.

But once the authorities had gone, there at the well-mouth appeared Mohammed Shabash as an eager ally. "Come up, mister. They have gone and will return no more. You are English, and the English I do not like. But I hate the French. I wish you were spy."

"If you hint at that again, my buck, I'll wring your dusky neck."

"I do not care. You are English, and I wish to give pain to French. There has come to my hand a plan of the Bizerta fortifications and all the cannons. I will give it to you, and so revenge will come to me, and my honour will be save."

"Anything to oblige," said the little sailor; "hand 'em over. But now let's get to business again."

By what devious methods Captain Owen Kettle was smuggled out of the city of Tunis and lodged in the stable of a well-camel at Marsa need not be here recounted in detail, as many excellent people in the bazaars would be thereby implicated. The spy craze was still running cheerily; in military circles there was abundant activity; and the journalist with the ridiculous beard had made himself so conspicuous, that a full description of his person had come to Captain Kettle, which that peppery little man had stored for future reference.

A night expedition from La Marsa up to the hill beside Cardinal Lavigerie's ugly white stucco cathedral came to Kettle as a surprise. He had expected to look down on the ruins of a vast city, bristling with walls and populous with broken columns. Algeria and Tunisia are thick with these, and there are many in the deserts beyond. But when instead his eye met ploughed fields and barren headlands he thought of the intricate plan in his pocket, and felt the taste of something very much like defeat.

But he was no man to accept a reverse from the first blow. He made his way down the steep hill-sides and found that the clear African moonlight from above had not shown him everything. Here and there were pits dug in the ground or galleries driven into the slopes. He explored one and got an idea; explored a couple more and established a certainty.

Carthage still existed underground, and out of sight of the sun. Carthage had been partly tapped by latter-day archaeologists, and probably mapped by them. When he came to think of it, this would be within Ali Akkerin's knowledge, seeing that that worthy brigand had received his reports from the place quite recently. The only trouble was, had the treasure been disturbed and carried away surreptitiously? That could only be found out by experiment.

He returned to Marsa, sent word of his need to Mohammed Shabash, and in a week had a copy of the French archaeologists' charts of the ancient Phoenician and Roman cities of Carthage. The charts had been difficult to procure; the spy mania still buzzed; and Captain Kettle was prayed to observe the most exquisite caution.

He pored over the plans, and soon found the points he wished for. The sketch of Ali Akkerim tallied in every particular. It was a great feather in the cap of the French archaeologists—if only they could have known. Then, armed with pick and shovel, with provender and wine for a week, he set off one night to commence work.

The moon had worn itself out, and the night was conveniently dark; and Captain Kettle stepped out upon his way, with an elated feeling that fortune was near to him. He had visions of chests of gems, of great stacks of gold and silver built up in portly crossbars; and always behind them he pictured Mrs. Kettle and her daughters, dressed in silks of the finest, and being looked up to as people of fortune by all the chapel circle.

He went up over the hill past the Roman amphitheatre, and down the steep slopes of the other side. He hit the road, and held along it for some time. Then, after finding his marks, he struck off toward the seaward side, and presently stepped down the inclined way which led to some abandoned excavations. Fortune and the French had been kind to him. Modern diggers had burrowed underground close to this very treasury; they had created a whole labyrinth of tunnellings; but by some marvellous luck they had halted conveniently short of the prize.

In the meanwhile M. Max Camille, journalist, of the city of Tunis, was a man with vanishing credit. He had cried Espion Anglais! and had received much pleasant applause; several quite unlikely people had been arrested, and certain troops of the Republic saw more of the vie intime of native Tunis than falls to their general lot. On a very slender foundation of fact, M. Max Camille had built a very considerable superstructure round the person and the projects of this spy, and, having some acquaintance with another of the arts, had knocked off a very creditable sketch of the little Englishman, which was duly reproduced in his paper. But when after abundant search this same pernicious person was not forthcoming, and no one in Tunis in the least recollected to have seen him, then certain officers, under the irritation of Tunisian summer heat, called M. Camille not journalist, but liar, with the usual consequences.

A couple of harmless but soothing duels cleared the air somewhat. But in spite of his ridiculous beard M. Max Camille was no fool. He saw that his journalistic credit was ragged. It galled him to remember that he had been a fruit sec at home, and he was determined to mend matters, if energy could do that same. The fierce looking little Englishman had been in the Souk el Attarin, there was no doubt about that; and though his business as spy had only been guessed at in the first instance, this disappearance, in M. Camille's mind, went far to-ward proving it. All train and steamer exits had been watched. The man could not have got far away. It remained then to find this English spy, and cover himself with glory.

Money for bribes he had not got, but a North African journalist is not over scrupulous, and M. Camille had ways of putting the screw on some of the denizens of the bazaars which would not look well if bluntly set forth on paper. In two days he materialized Kettle into something more solid than a rumour. On the third day he learned that the man had gone to Marsa. On the fourth day he ran him to earth in the reeking camel stable aforesaid.

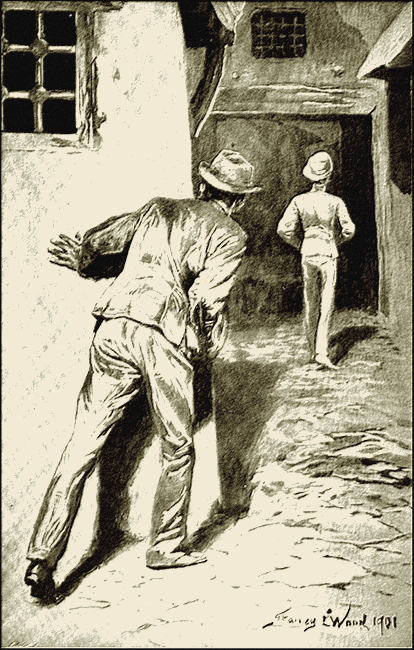

M. Camille said nothing about his find. He had been accused of turning up a mare's nest once. This time he would catch his man red-handed in his espionage before capturing and exposing him. The camel (of the stable) was employed during day hours in rotating a water-whim on an adjacent housetop, and in this dwelling M. Max Camille found quarters. He watched all Captain Kettle's movements with a jealous eye, and when under cover of night the little sailor went abroad, the journalist with stealthy footsteps and handy weapon invariably followed him.

He watched all Captain Kettle's movements with a jealous eye.

He could not quite make out why this spy should make for the site of vanished Carthage. No fortifications lay thereabouts. But because the thing was not understandable, that did not make it any the less suspicious, and M. Camille followed with an eager mind, and figured to himself Max Camille, the journalist, driving before him at pistol's mouth this accursed British spy whom all the troops of Tunis had failed to capture. It was a luscious picture.

Arrived then that last night of Kettle's stay in Marsa, when he took spade, pick and stores, and made for the burrow. M. Camille followed faithfully in the shadow behind. The Englishman walked quickly, treading the way with the assured gait of one who has very definite notions about his destination. He entered the mouth of one of the excavations, halted a moment inside to light a candle, and then held confidently on.

There were no superfluous tremors about M. Camille. He pulled a revolver from his pocket, held it ready, and stepped on softly in the other's wake.

The galleries twisted and turned; climbed up and then down; and grew high or crouched low with maddening uncertainty. The light of the candle ahead waxed and waned. The stuffy heat of the place was enough to choke one. But on and on the leader held his way, and with grim persistency M. Camille followed.

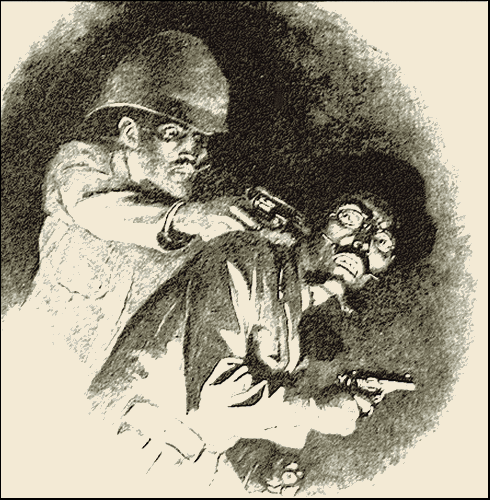

Then of a sudden, what was that? The candle stood by itself on the floor. He held ready his weapon. How could this perfidious—

A strong grip seized him by the collar, and a ring of cold metal was rammed into the back of his head. A voice said in French: "Drop that gun, you sacred pig, or I'll blow your back hair out through your whiskers!"

A strong grip seized him by the collar, and a ring

of cold metal was rammed into the back of his head.

It is scarcely to M. Max Camille's discredit that he threw down his weapon as though it burned him. There is something very persuasive in a revolver muzzle suddenly screwed into the nape of one's neck by a man with such a commanding voice as Captain Kettle's.

"Now march to the other side of that candle, and turn round to let's have a look at you. See you don't knock over the light, or I'll put some lead in you just as a safeguard."

M. Camille did as he was bidden.

"By James, the man with eyeglasses and the ridiculous beard. So it was you, you figure of fun, that set this spy-hunt on my heels, eh? Answer me."

M. Camille saw no reason to accuse himself unjustly. "I met monsieur in the Souk el Attarin, and monsieur asked to be directed to the house of a Touareg, surely a suspicious request in Tunis, seeing that the Touaregs are always making war on France. Enfin, the rumour seems to have been built up on that."

"I see. Modest of you. Bazaars have ears, but we don't say whose feet they walk about on. Well, my lad, you've poked your nose in where you are not wanted, and now you'll just have to stay till it's convenient to let you go."

"I'm afraid I do not exactly understand."

"My French," said Kettle grimly, "may not be first chop, but if you force me to start handling you, I'll guarantee you don't complain that I fail to make my meaning clear then. I'm here, my man, to dig up part of Carthage. I don't know whether you've done any navvying before, but I guarantee you'll be tolerably expert before I've done with you."

"But I don't agree-"

"I don't ask you to. But presently you'll be requested to work, and if you fail to do your whack, I shall argue with you in a style that will probably surprise your nerves."

It is better perhaps to pass lightly over the painful apprenticeship which M. Max had to serve before he became thoroughly acquainted with Captain Kettle's methods, and thought it best to submit to them. He resisted vehemently at first, and was belaboured with the haft of a shovel till he saw fit to delve. He tried to pass over his taskmaster when they desisted from labour, and supped, and lay down to rest, being deceived by the little man's snores; but promptly discovered that he slept weasel-like with one eye on watch. And there were other episodes.

But presently, when they settled down, there grew up between the two of them an understanding of one another's qualities which amounted almost to respect. Their hands were chafed to rawness on pick and shovel as they laboured to dig through the deposits of the ages, and the dust and the stuffy heat kept them in a state of approaching strangulation.

The debris they dug from their pit they stored in the galleries behind them, so that every basketful tended to constrict the already narrow air space. But Kettle, in a moment of expansion, had let out the secret of his quest, and had promised M. Camille a handsome present out of his abundance when it came to him, and the journalist, who was naturally a fellow of fine imagination, brightened the toil with brilliant pictures of the hoard which lay so close to them.

At intervals came Mohammed Shabash or one of his emissaries bearing provisions. Mohammed was mad with excitement at the thought of making his fortune, and very frightened lest there should be trouble with the French Government about realizing. As Mohammed kept repeating, he was "mos' civilize."

But with Mohammed Shabash, Kettle could not make a friendship. Kettle had liked the savage Ali; but the more polished product of Earl's Court and Chicago had something so kickable in his nature that he bitterly repented that even hunger should have forced him into a partnership with such a creature.

And in the meanwhile the work went on. Pick, pick, pick into caked ground that was almost as hard as virgin rock, and then scrape, scrape with the shovel at the dusty fragments so hardly won. Clay they threw out, and scraps of stone, and fragments of figured brick, and clots of tessellated pavement. M. Camille compared himself to a troglodyte, and mapped out a plan for an underground cafe chantant in a palace of original Carthage. Captain Kettle pictured to himself what hell must be really like, both for climate and situation, and stored up in his memory notes for a sermon on the subject when once more he got back to the pulpit of his chapel in Wharfedale.

Never once did the little sailor's faith in Ali Akkerim's instructions fail. "The top half of what it said is correct," he would repeat, "as we've seen for ourselves. The archaeological chaps have rooted up the buildings round the treasury just as the plan marks them. And if we go on long enough we shall come to the bottom of the street where the door is. But by James! talk of dynamite. This dried mud is hard enough to chip bits off dynamite!"

Their constant labour, however, at last met with its reward. They bottomed their shaft and came upon a cobbled pavement. Another half day's work, and they cleared the wall of the treasury itself, a wall built of stone in massive blocks. Camille, full of haste now, was for attacking it forthwith, and quarrying a passage to the glittering wealth within. Kettle, more practical, showed that the polished granite was almost as hard as their pick, and that it was as likely as not a dozen feet in thickness. A doorway lay further on down the street. They must burrow a way to it.

They did this, with infinite pain and weariness, coming upon layers of charred wood now, compressed to the hardness of coal, and in the end were confronted with the door itself, a massive structure of bronze.

Here at any rate there appeared a check. But to their surprise the metal had so perished under the ages that they were quickly able to batter a passage. They scrambled with one another to be first through the opening. They found themselves in a vast chamber, pillared and vaulted. In it were stored red earthenware jars, each of the bigness of a man. The candles, burning with feebleness in the foul air, showed the place but dimly.

Each peered into the jars nearest to him. They were empty except for a little dust. They ran along the rows, searching, searching, and found always dust, but never metal, never gems.

Kettle threw over one of the jars, and it fell and splintered. "Just my luck. The place has been looted already."

M. Max Camille, the man of superficial reading, leaned down and fingered the dust. "I don't think so," he said slowly. "No, look there. That's a grain of corn. Ah, it has crumbled. But there's another. And look, another. Monsieur, we are in the Treasury of Carthage, and those jars contained the treasure, which has never been tampered with from the day it was stored till we arrived. The only error we made was to imagine that the State reserve would be coin or jewels. Naturally it would be corn. But I am afraid what is left would fetch little in the cereal market to-day."

"Just my luck," said Kettle. "Here, let's get out of this."

They climbed to the surface again and sat down on the ground facing the sea.

Kettle snuffed luxuriously at the incoming sea-breeze. "Good smell, hasn't it, after you've been away from it for long? It's a decent old puddle."

The Frenchman shrugged. "Each to his taste. For myself I always associate the sea with ships, and ships with purgatory May I take it that monsieur has now dispensed with my services?"

"Yes, you may go when you please. You don't get the bit of a plum I promised you, and I am sorry. You worked like a man. But I don't advise you to start off on that spy racket again, with me as a subject."

M. Camille laughed. "Monsieur has cured me of any desire in that direction. Monsieur is such a risque tout. But for this latter performance I should counsel a quiet tongue. It is strictly forbid to dig unauthorized among the ruins. And I am equally involved with monsieur."

"I'm not likely to brag about it. Besides, I shall be off to sea again presently. That's my proper place. I don't seem to turn up successes on shore anyway."

"Of course there is monsieur's partner, a native, I understand. It would be very inconvenient to me if he talked about the matter."

"Yes, I'd forgotten him. Well, we'll tell him we resign all claim to the loot, and let him come and look at it for himself and get his own share of the disappointment. He's a man who's earned my dislike. But as for talking, you needn't be afraid. He's far too careful of his own skin."

"Then good-by, monsieur. I am glad that you have forgiven that little misunderstanding about the spy trouble."

Captain Kettle winked. "That's all right," he said. "I've had my score against that already. Look, here's a draft of the letter which I forwarded under the cover of one to my wife."

He pulled a paper from his pocketbook, and lit a match. This is what M. Camille read:

To the General Manager

War Dept., Govt. Offices,

London, Eng.

Sir—

Enclosed please find plan of forts, harbor's, etc., at Bizerta. Have come across these here, and am sending them because French took me for a spy, which I am not. If they had not worried me should not have sent them. I understand your Intelligence Deptartment is very inferior, so these will probably come as news to you. I am not asking for any pay, for, although a poor man, I have my pride. But, if there is any pay going, you might send it to Wharfedale Particular Methodist Chapel, Craggetts, via Skipton-in-Craven, for general maintenance account.

Yours truly,

O. Kettle (Master)

"Sacred blue!" said M. Max Camille.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.