RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Captain Kettle, K.C.B., 1903,

with "A Diplomatic Exchange"

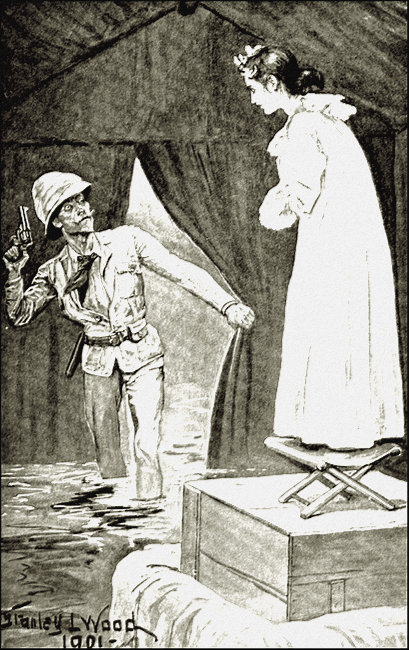

"I beg your pardon, ma'am," gasped Kettle.

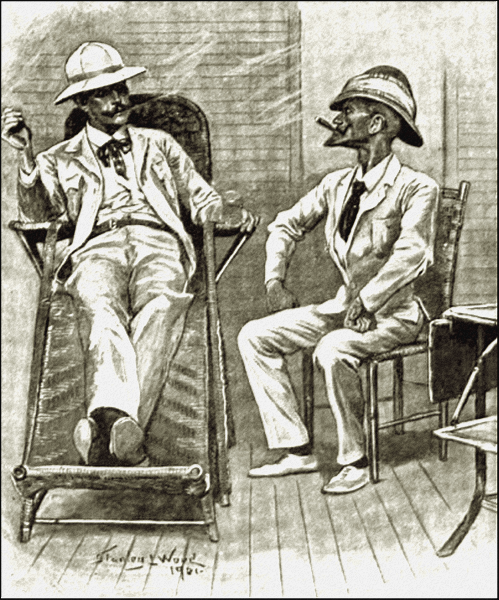

THE British Resident leaned forward in his long chair and tapped his empty glass with his cigarette case, "I can give you no official leave, sanction or encouragement; so please understand that very clearly."

"I had grasped that much, sir," said Captain Kettle, "before you had got through with ten words of your story. But am I to understand that the Government authorities of the-"

Again the Resident interrupted hurriedly. "We will name no names if you please, Captain. If, when it is absolutely necessary, you refer to the people in question as the Other Power, I shall understand you. I don't suppose any one is eavesdropping at the present moment, or naturally I should not be speaking at all. But one never can be certain about these things, and, if you please, I'd rather change the subject. Hang it, man," he added petulantly, "you know what's wanted: why make further palaver?"

The little sailor stroked his red torpedo beard. "Yes, sir, I know what's wanted well enough, and I'm always ready to do the British Government a good turn. I've a sincere affection for my country, and I'm sure the Government would be both surprised and gratified if they knew how many times I've stuck up for them already. But I can't afford to go into this matter purely for philanthropy and patriotism. This guano island speculation that I've been telling you about has dealt me a very severe blow financially. The difficulties of landing were enough to make you cry. The place was a regular graveyard of reefs. With the ghost of a bit of swell running, no boat could live among them, however cleverly you handled her. There was no fraud about the island; the guano deposits there had a richness beyond belief; but all I could do on the steamboat was to sit still and smell those riches from a distance, and watch my grub and wages' bills mount up. I composed a little poem, sir, on the subject, entitled 'So near, and yet so far.' It struck me as both original and chaste. If you'd care to hear it, I have a copy in my pocket."

"No, no, another time, Captain," said the Resident hurriedly, and Captain Kettle sighed. "Of course I knew you were not exactly in luck's way, or you wouldn't have stepped ashore on the Red Sea bank at such a God-forsaken hole as this. I have even omitted to ask, you'll observe, how you got separated from that steamer you chartered to work your guano deposits, and I may mention that over yonder at Aden they're wild with curiosity on the subject."

The Resident nodded out across the veranda to where the Red Sea danced and glimmered like a sheet of burnished blue metal under the deluge of sunshine. "Very active people over there at Aden," said the Resident meditatively, "and they've got a most annoying lot of gun-boats in harbor always ready to send round to make inquiries. Have a cigarette?"

"I thank you, sir, but I never use them."

"Stronger meat for you, eh? Well, if you prefer to stick to the cheroots, the box is beside you. You see I'm by no means harrying you. I'm sure I am very sorry for your misfortunes. Naturally you want to make as much out of this new thing that's put in your way as possible, and all I can say is, that what loot you can get depends on your own ingenuity."

Kettle shook his head gloomily. "It's very vague, sir, that. I'm sorry to be so pressing, but the fact is I've a wife and daughters to think about. They're on a little farm at home, and you know what farming is. We've a mortgage on the stock, and I did look to that guano spec, to pay it off. Guano seems so poetically appropriate to assist farming. But now that's failed, I've got to provide the interest on that mortgage somehow, and the rent, or there's my family turned adrift."

"Well, the job's waiting for you."

"What you offer, sir, is so very vague."

The Resident shrugged his shoulders with some impatience. "It's the best I can do. I can hand you a small sum of money to free you from your present embarrassments, and to start you off up-country, and after that I'm afraid I shall have to disown you officially and every other way. Even this small sum will have to come out of my private purse. And then there's the risk. I suppose it is that which scares you, and, indeed, I don't see why it should not."

The little sailor stiffened sharply out of his dejection, and sat upright in the chair. "The risk, sir," he said acidly, "you may leave out of the question. I'm the least easily frightened man on earth when once I meet with opposition, either from black men, or from white."

"The risk, sir," he said acidly,

"you may leave out of the question.

"Then," replied the Resident, with some dryness, "if the risk does not frighten you, and your needs are as great as you say, I should advise you to start off without further delay and get that loot. It's there right enough."

"You've not said that in so many words before. Are you sure?"

The Resident lowered his voice till it became almost a whisper, and leaned across to Captain Kettle's ear. "My agent saw the loads made tip. We've had our attention on the—er—the Other Power along this side of the Red Sea for some time, and have been watching them more narrowly than they've any idea of. They know to a certain extent that we've been keeping a brotherly eye on them, because they tried to brazen it out. The Governor there wrote to me for permission for a trading party to pass through our Somaliland territory to trade and shoot in the interior beyond. I wrote back very politely that I could not give permission, as the district was too dangerous for travellers."

"But that's not diplomacy, sir, is it? It's merely the truth. The Mad Mullah's 'out' just now, isn't he, and the country's alight?"

The Resident chuckled. "Diplomacy isn't necessarily all lies, Captain. Sometimes the truth is more convenient. It was no news to them about the Mad Mullah being 'out.' The trading party were simply taking up arms for that person to use against us. See?"

"Perfectly, sir. And so the Governor wrote back that you could go to blazes, and the expedition would trade as it jolly well liked?"

"Pooh!" said the Resident. "That's not diplomacy, my dear Captain. A letter like that might very well bring about war between England and—er—the Other Power at touchy times like these. No, the Governor wrote back most civilly, thanking me for my warning, and stating that he had refused the expedition his leave to start. But at the same time his polite Excellency gave that expedition a firm hint to start without leave, and away they went."

"Then I don't see," said Kettle doubtfully, "what's wrong with your sending some of your own troops to cut them off. I've no very high opinion of soldier officers, as I've mentioned frequently; but surely they are equal to a small job like that?"

"Oh, the soldiers could snaffle them easily enough if I chose, but if the beggars were caught officially, don't you see, they'd think of their own skins first, and let on that his Excellency the Governor had sent them, and then—well, then there would be a row. Let me tell you, Captain, there's enough fat in the fire already between Great Britain and—er—the Other Power, and I shouldn't be thanked for dropping in the extra handful which might well set half the world in a blaze. Come, man, you must see which way the cat jumps now. It's a case for nice diplomacy."

It was acting on these somewhat obscure hints and instructions, then, that Captain Owen Kettle found himself traversing a portion of British Somaliland, with the attendance of a party of forty-three armed natives. By daytime he had to evade the bands of the Mad Mullah, the local faction fights which are always set up in a disturbed country, and incidentally to keep out of the way of those tiny armies of British native troops which were doing their best to hammer the country into quietude again.

By night, when the lions sang their lullabies, he had personally to attend to the fires and the thorn zareba, as no amount of hard handling and hard language would make his Mohammedan following careful in this direction. Their theory was that if it was written that lions should devour them, this would surely come to pass. Wherefore it was entirely useless to stay awake on sentry-go, unless perchance they were encamped in the neighbourhood of a hill of red ants. The which was consistent, of course, but irritating to a non-fatalist leader. However, when it came to fighting, they showed up artistically enough to satisfy even such a connoisseur as Captain Kettle.

The country was, as I have said, in a state of considerable turmoil, and it was Kettle's object to thread his way as nicely as might be between the various centres of disturbance, so that he might arrive at his final destination with a force if possible undiminished. He had a constitutional distaste for avoiding a fight, but the needs of his wife and daughters at home were always at the back of his mind, and he did constant violence to his own appetites on their behalf.

But there is a limit to the forbearance of all men, and Captain Kettle's was reached when one day, on topping a rise, he saw in a pleasant valley immediately beneath him, a battle displayed in full working order. A small force was holding a village of wattled huts, a larger force was attacking with savage ferocity, wounded writhed here and there, twisted dead dotted the ground, a field gun coughed spasmodically, a hut burned, and a dazzling sun dished up the whole scene into the plainest possible view. Even then he had it in him (remembering those at home) to have retired quietly from the ridge. But a tall white man showed among those who defended the village, plainly leading them, and as the attack pressed more ferociously, the white man showed more, exposing himself with the utmost of recklessness, and doing prodigies of valour to inspirit his desponding troops.

That tall white man held Kettle's admiration, and clogged his retreating feet, and presently, when it was plain the village would be rushed by overwhelming numbers, the kinship of blood boiled within him so strong that the last taint of his prudence evaporated.

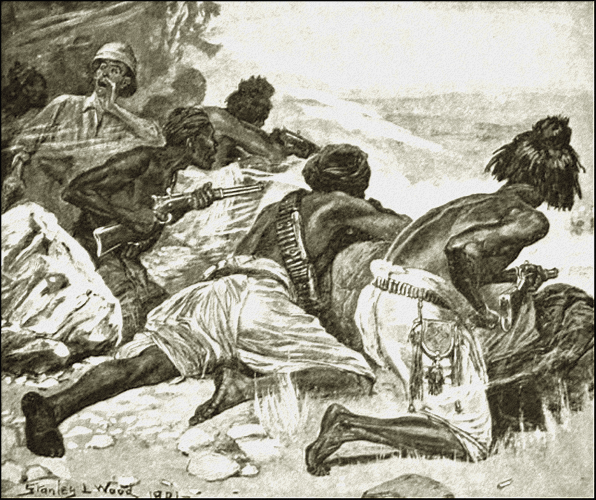

To give them their due, his native following were willing always for warfare, and he had little trouble in hustling them to cover along the brink of the ridge, and when the word was given, they loosed off their fire as fast as their dusky fingers could slip cartridges into the Remingtons.

When the word was given, they loosed off their fire as

fast as

their dusky fingers could slip cartridges into the

Remingtons.

The effect was sufficiently surprising. The attacking army in the valley below them halted in its advance, and began to make aimless little rushes to this side and to that. One of the panics so common to undisciplined troops had gripped them, soul and bones; and when one, more ingenious in his fright than the rest, hit upon a line of flight, they tailed in after him as fast as their toes could spurn the ground.

The tall white man of the village with his own hands helped with the gun to bedeck their departure, and he was engaged in firing a final shot, when Captain Kettle and his tail marched up to make his acquaintance.

"I trust, sir," said the little sailor, "that you will pardon my interference, but it struck me at the time I chipped in, that those beggars had about given you your bellyful."

"Don't mention it," said the tall man, laughing. "They'd have got us as sure as cooking if you hadn't helped. They were some of the Mad Mullah's crew, and regular devils for fighting. To tell the truth they've been chivvying us for three days, and have got all our truck, pretty nearly. It was all we could do to save this rotten little pop-gun here. Hayden's my name, by the way. You don't happen to have such a thing as a whiskey and soda among your loads, do you?"

"I'm travelling very light myself," said Kettle evasively, "and the whiskey was forgot to be put in. I'm sorry. I should have liked very much to have drunk your health."

Hayden stared. "Oh," he said, "I beg your pardon. I thought you were some swell come up here lion-shooting."

"I don't know, sir," said the little sailor with a flush, "that my personal status is any concern of yours."

"Of course it isn't, not a bit. Please believe that I didn't intend to be in the least rude. One's been up-country here so long among natives that one's forgotten how to speak ordinary civil English. Of course I'm infinitely obliged to you for saving me and some of Britain's dusky forces from being wiped out. But you see, being in command of this district, one has to fill up official forms and things, and I'm just now wondering as to what you might be up here after."

"Then, sir, you may enter under the heading of 'occupation' that I am 'engaged on urgent private affairs.' That's true, and it's diplomatic."

It was Hayden's turn to blush now. "You make things very awkward for me. You have just put me under a tremendous obligation, and so I can't possibly arrest you, which I rather believe it's my duty to do."

"Oh," said Kettle stiffly, "don't let that stand in the way, sir. You may arrest me if you're able; but I've been bidden to use diplomacy over my present errand, and I'm going to use it now or know the reason why. So I must bid you now good afternoon."

The little sailor whistled his natives together, gave a direction to the headman, and set the caravan once more upon the march, himself waiting to act as rear guard. Hayden stood uncomfortably at his side, feeling to the full the embarrassment of the situation.

The long snaky line of the forty-three men, some with loads on their heads, all with rifles, at last got into swing, and Kettle fell in at their tail. "Good-by, sir," he said, as he stepped off.

"Good-by," said Hayden, thinking hard. "Much obliged to you. Fall back on me if you get into trouble further on." And with that he turned and set about giving orders for the burial of the dead and the tending of the wounded. But presently he made up his mind, and went to his fellow white man, who was doctor to the force. "Pat," he said, "look here; that little chap with the red torpedo beard isn't up here lion hunting, and he isn't up here exploring. He can only have one possible game, it seems to me, and that's mischief."

"Well, you can't shoot him out of common decency, after pulling us out of the fire the way he did.

"Quite so; but we can follow him up and spoil his game."

"Ye—es."

"We must He's on the make; you can see it in his eye. There's only one kind of commercial spec, that would pay in British Somaliland at the present moment, and that's taking arms and cartridges to the Mullah. The old scoundrel's got plenty of money, and he will pay handsomely if he's approached in the proper way."

"But the small chap hadn't got the arms with him—or at least very few."

"Oh, that's all right. The cargo couldn't be shipped on our sea-board. That'll come from the next territory, and he'll rendezvous with it at a fixed spot, and come into touch with the Mullah on the road, and make arrangements about price and delivery. You have to go through these preliminaries when dealing with Mad Mullahs, or otherwise, if you are found personally convoying the guns, they just shoot you, and collar the swag."

"Sweet lot."

"Aren't they? Well, get your invalids into hammocks, and away we go on our friend's trail. We'll deal tenderly with him because he's been nice to us—although to me personally he was most objectionable. But we must upset his little game, because that's duty."

Here then was a surprising result yielded up by Captain Kettle's attempt at diplomacy. A more experienced officer might by tact have discovered more of the truth, or by induction have guessed at it. But Hayden was merely an ordinary militia subaltern, with more adventurous spirit than brain, who was seconded from his regiment, and attached to a corps of native levies; and up-country in Somaliland he had learned more about rough-and-tumble rely-on-yourself fighting than about the exigencies of politics. That Kettle was in some way connected with arm-smuggling with the enemy he guessed quite correctly, but that the British Resident in one of the Coast towns could be the little sailor's backer was quite beyond his conception.

Captain Kettle on his part marched on with an equable mind. He had yielded to the impulse of saving a man of his own colour; but he had not truckled to him in the least; and had preserved his own independence and respect. Moreover, though the opportunity lay open to him, he had not lied about his business. But at the same time he felt that he had concealed it entirely, and plumed himself on his diplomatic skill in doing so.

His onward progress was not unattended with casualties. Like many another commander before him, he carried no stores of provender. His impedimenta consisted of rifles and ammunition. And following the innumerable precedents of other military expeditions who for various reasons have had to travel light, he lived upon the country. Of course Somaliland is not England, or even the United States; but even Somaliland at times objects to the comparative stranger who comes to live upon it, and being a primitive country, is apt to translate its protests into active measures.

There were times indeed when Kettle and his merry men had to retreat, and that hurriedly, with hunger gnawing at their belts, and despair sitting heavy upon their shoulders. There were other times also no less terrible, in the deserts, where they fought for the possession of some well, and were beaten off with swollen tongues and with leathern throats, to march on under the parching sun to the next water, or die by the way as seemed them best.

The original forty-three dwindled in this process, but the numbers of the company were kept up by those rough-and-ready means which are native to these countries of low civilization. The sentiment of loyalty there means loyalty only to the master for the time being, and a prisoner made one day might very well be fighting bravely against his former friends on the next. As to the question of arms, that adjusted itself. The Remington rifle is common currency in Eastern Soudan, Abyssinia and Somaliland. If a Remington was lost, the next new recruit used a spear or tree root, or whatever weapon offered till another Remington was recaptured. Such are the resources of a self-supporting force when under the command of a leader of Kettle's ingenuity.

His final exploit of capturing the expedition with the smuggled arms was brought off with an ease that was almost laughable. From information picked up from the villages through which it had passed, they had been on its trail for some days, and finally, coming to the edge of a forest belt, espied it in a fortified camp in the middle of a small open plain.

To storm and capture this by open assault was a feat impossible even for a man of such desperate reckless bravery as Captain Kettle, with so small a following behind him, although the following by this time, to give them their due, would have gone anywhere the little sailor led them. But inside the zareba in the plain were two hundred men at the very lowest computation, and although many of these were officially carriers, there were naturally plenty of weapons available, and the East African black is very adaptable in these cases. You may use him as a carrier for six days of the week, but this will make him act none the worse as a soldier on the seventh.

Captain Kettle halted his men inside the rim of the forest, and then, to prevent straggling, marched them half a mile back to make their bivouac. He issued orders to the headman to see that no one gave the alarm, and the headman (when Kettle's back was turned) translated this into a cheerful threat to crucify any one who made himself obnoxious in this way, head downward, over a slow fire. The which was quite in concord with the custom of the country and with all his friends' views.

So they set about their cooking quite unconcernedly, and watched the small white man who had led them go off to reconnoitre, placidly convinced that when they had eaten he would invite them to a fight that would be fully worth their attention. As has been hinted before, the Mohammedan negro of East Africa enjoys active warfare rather more than does the fighting Hausa of the Western Soudan, which is rather more than the average athletic Englishman enjoys a cricket or a football match.

Captain Kettle walked back to the edge of the forest growth, and taking his stand in the bush a yard off the path, where a fringe of orchids and creepers screened him from any possible watcher, set himself quietly to prospect the resources and defences of the party before him.

The zareba, he noted with disgust, was an uncommonly strong one. They were out of the range of that country where the camel thorn grows, and at first sight he had concluded that the fence was one which could easily be pulled to pieces. But closer observation showed that it was built by one who took no superfluous chances. Its bushes were all of spiny, spiky wood, which would tear a bare skin like so much glass, and, moreover, these were woven together with no amateur architecture. A stream watered the camp, so starvation tactics could not tire it out.

Kettle bit his teeth round the butt of a dead cheroot, and puzzled over the situation. What had to be done must be carried through quickly. It was no place or season for dilatory operations. That swiftly moving person, the Mad Mullah, was in the immediate neighbourhood, and it was well known that he had a scent for munitions of war surpassed by no nose in Africa.

Kettle stared at the encampment with the last of the afternoon sun, and stared on when the darkness of night had snapped down with its tropical suddenness. The lights of the cooking fires gave up the camp as a vivid picture.

Gradually a scheme for its conquest unfolded itself to him, and then by degrees all its details were thought out and perfected. He wished to take no risks, and so he hammered at his plan till absolutely no flaw showed itself, and then, and not before, did he go back to his own bivouac and issue orders.

The men were well fed and rested, and ready for the work. The ghosts of the forests, which always parade and do their mischief in the darkness, were not there that evening, because Captain Kettle said they were not, and when the scheme was explained to them, the black men set about carrying it into execution with chuckling glee.

It had occurred to Kettle that the stream which watered the camp in the plain was capable of manipulation. The forest which sheltered his bivouac lay on a furrowed hillside, and the stream ran here also. It had dug for itself a ravine, and by Kettle's direction this cut was now being dammed. It was no common dam his followers built, either, but one more after the fashion of a sluice-gate, which at a given notice might be thrown bodily down.

Below in the camp on the plain the stream dried up, but no one gave the phenomenon any special notice. Up in the woods men toiled through the hot damp night, tearing down branches, carrying turf and bush for the building of the dam. And behind its embankment the water in the ravine gathered and formed a quiet lake.

Three-quarters of the night through did this toil go on, and the negroes sniggered and gurgled in the darkness over their tragic joke; and then when a sufficiency of water had collected, and dawn threatened, Kettle led forty out toward the plain, and left the headman and two others to see to the breaking of the dam.

Punctually to its time the deluge welled out, swirling with its debris down the ravine, rushing through its old channel across the plain, and then brimming above the banks, and flooding the camp thigh deep, and sweeping the zareba hedge before it as though the stout interlaced bushes had been thistledown. The chilly surprise of it would have dampened the spirits of any troops; it daunted those inside the zareba beyond even Kettle's highest expectations.

When he and his company came splashing in behind the last wave of the destruction they had set loose, they met with no resistance. Not a rifle was fired against them, not a sword was lifted. There stood before them ranks of men dazed and dully submissive. If this sender of the waterspout wished to cut their throats, it was written that he did this thing; if he merely wished to take them into his own slavery, again, it was Allah's will. There was but one Prophet, and every man's fate was writ large upon his forehead. It was impious to deny the Prophet, or to struggle against decided fate.

Kettle took steps to guard that there should be no reversal of this idea, by rounding up his prisoners under guard, and carefully depriving them of all utensils of defence; and then he began a search for the white man in command, who was the subject of that Other Power, and about whom the Resident had specifically given him information and instructions.

Pie had already in his own mind formed an opinion that either this individual was down with fever, or else was no small piece of a coward, or otherwise he would have shown fight, or at least have tried to put spirit into his men. A green canvas tent that showed dimly in the thinning night seemed to point to the white man's residence, and Kettle splashed toward it through the falling water, with a revolver muzzle against his shoulder in case of accidents.

The flap of the tent was pinned over with a thorn. He pulled it rudely open and stepped inside, with weapon ready to drop into instant use.

He went in with his fierce little face drawn and set, ready to meet sudden death or deal it out. A moment later he had rushed out of the tent blushing scarlet all over his body.

The canvas house was dark when he stepped inside, and at first he had seen nothing. He searched the gloom with his eyes, following them with a revolver muzzle. Then a little feminine scream fell upon his drawn nerves like salt on a cut. There was a camp bed at one side of the tent, and on that a packing-case, and on that a chair, and on that again, with a head en papillote pressed against the roof, a pretty little lady dressed in an elaborate robe de nuit.

"I'm sure I beg your pardon, ma'am," gasped Kettle, and made his exit in the condition described.

Here then was a complication. Here was a jape for fantastic fate to play against him. A man he could serve with any indignity the moment suggested; but a woman! He blushed afresh at the thought of his encounter.

But as he cooled, the memory of his own womenkind at home and their needs came back to him and forced him to take action, however distasteful the situation might be to him. He could speak the language of the Other Power with inaccurate fluency.

"Inside the tent there?" he hailed. "Will you tell me who is in command of, this outfit?"

"I am," came the astonishing reply.

"Are you alone in there?"

"Certainly, monsieur."

"Then I must ask you, madame, to refer me to your partner. Where shall I find him?"

"I have no partner; the cowards were all afraid to come. I am here by myself."

Kettle cursed beneath his breath. "By James!" he murmured; "was ever any man in such a dirty fix?" But the thing had to be faced. He continued doggedly: "Then, if there is no one else, I must see you. Please dress, madame, as soon as you are able."

"Is that abominable flood over?"

"Yes."

"If it had not been for the rainstorm and the flood you never would have got here. I would have fought you. G-r-r-r! Yes, I have taught my black creatures how to fight admirably; but the water vanquished me, and Heaven sent the water. Yes, it is Heaven alone which has made me yield."

Kettle modestly let the credit rest at that; but he repeated his request for an interview.

"In a minute, monsieur, when I have dressed. If you are in more hurry, you must come and help me find my clothes which I saved with difficulty, and which are in terrible confusion. Will you help?"

Again the little sailor grew pink. "Oh, no hurry, madame. Get your things ship-shape in your own good time."

"Well, monsieur, I will be ready in one minute, then."

It was a long minute. Indeed, chronologically, it was fully one hour and a half before madame in the freshest of tropical apparel, and beautifully coiffured and complexioned, stepped out into a well-aired morning world. The camp had been swept and garnished, the zareba rebuilt, fresh fires lighted in place of those that were swamped, with prisoners and guards hobnobbing over the breakfast-pots.

Madame's own body servant had been found and set to his usual employments, and Kettle presently saw himself sitting to a camp table under the shade of the tent-fly, and enjoying as chic a petit déjeuner as any man could wish for.

"I thought we could discuss terms better over our coffee," said the lady. "I confess to you freely, that the wet and the dark daunted me horribly. But here in the sunlight"—she flicked her eyes at him—"I do not think you will be very cruel to me."

"I must do what I came for," said Kettle, steeling himself.

"Ah, you English officers, you have no thought except for duty. To you a poor lady's feelings are of no concern. You are an English officer, is that not so?"

"I have been given this job by the British authorities," said Kettle, feeling that here was a case for diplomacy. "But I am free to confess I did not expect to find a lady in command of this expedition, or I would not have undertaken to raid it. Madame, you should not have come. It is no place for you up here. Whatever made you attempt it?"

Madame shrugged delicately. It was triste at home. She wanted a new sensation. Since her dear husband died, there had been so little to amuse her. To meddle with international politics seemed such a deliciously risky game. So chic. So new.

"You may be very thankful I caught you up when I did. If you got into that Mullah's dirty hands, you'd have regretted it once, and that for all the rest of your life."

"So they said at the coast, but I didn't believe them. Monsieur my partner would not accompany me, so I came without him. It was so much more new to be alone. For a man there might have been danger, perhaps. For a lady, I do not think it. Monsieur the Mullah is a great general, and he will have his qualities like other men. I shall tell him that I am not British. When he hears that I have brought him up these arms, I figure to myself I shall have his admiration."

"If he were anything but a savage," said Kettle gallantly, "you would have it in all abundance. But the Mullah is the Mullah. If you don't know about his little ways, let me tell you some of the tales I have gathered about him as I came up-country." And forthwith he reeled out a string of fantastic African horrors which any man may collect for himself as he traverses that sultry land.

The lady heard him without a shudder, fanning herself prettily. Really she had a most comely face, and her clothes and her hair became her amazingly.

"But these poor Africans," she kept repeating, "consider their unfortunate personal appearance and their habits. Monsieur cannot compare me to these Africans. Nor would the Mullah."

"No, madame," Kettle would assure her grimly. "The Mullah would put you in quite another class. But I don't think you would like the result any the better for all that."

"It seems to me, monsieur, we are come to an impasse. May I hear what were your instructions with regard to me?"

"Shoot you, and bag the arms."

"How concise! And if I had been a man, you would have carried it out?"

"If you had fought. If not, there is the tree."

The lady delivered herself of a pleasurable little sigh. "It seems that I am wading in waters more deep than I thought. Indeed, I had only reckoned on the Mullah. The flood—and the pleasure of monsieur's society—were outside my calculation. Well, monsieur, I do not see how you could well hang me. If you would put my coffee cup upon the table? My arm is short. It seems I am so dependent."

"Of course I can't hang you; that's out of the question now. But what to do I can't see."

"It would be the truest gallantry if you could withdraw, and leave me to finish my journey, and test the chivalry of the Mullah."

"Out of the question, madame. And, besides, I take it you would have no wish to continue your journey without your cargo."

"Ah? So? It is the arms that attract you more than my poor self?"

"Madame," said Kettle simply, "those arms represent my wages, and the pay for my men, and I cannot afford to go back without them. We will, if you please, end this conference now till I see my way to decide upon the disposal of such a lady as yourself."

NOW in the meantime Hayden had been following up Captain

Kettle and his company with remarkable closeness, and

his advance scouts had even been in time to see Kettle's

headman and helpers knock down the dam which was used

with such strategical effect. The scouts had the sense

to drop down into cover, and return with their report

without giving the alarm, and Hayden then made a further

reconnaissance. As a result, he lay over that day where

he was, dug an earthwork for his gun with great quietness

during the ensuing night, at the edge of the open ground;

and then when morning rose, pretended for the first time to

discover that Kettle was in possession of the camp inside

the zareba, and went forward in person effusively to

greet him.

"Why, my dear chap," he said in return to the little sailor's dry salutations, "here was I thinking I'd stumbled across a nest of the Mullah's, or at any rate a nest of some joker who was smuggling in arms to that worthy man; and look, I've got all my ruffians nicely ambushed in the edge of the wood there ready to pour in a regular typhoon of lead, and my gun in an A1 Woolwich emplacement. Dandy kind of trap for you, wasn't it? Left Doctor Pat in charge, because I thought I recognized you here just at the last moment. Wouldn't have inconvenienced you for worlds. I say, who is the lady?"

If Kettle had not met Hayden already and taken his measure, he would have put a pistol to his head and ordered him to draw back his gun and men under pain of having his brains blown out. But each was fully aware that he had a coolly desperate man to deal with, and owned also that the other knew the fact. Kettle quite understood that Hayden would not give in, and that if he shot him, Doctor Pat had his orders to open fire at once, and told himself also that when the shells began to fall among the ammunition cases, the zareba would be no place to live in.

It did not take more than a breathing space to tot up all these points, and to decide that temporizing was the only alternative. Besides, there was to be faced the fact that he did not in the least know yet how to dispose of madame. So, by way of gaining further time for consideration, he introduced Hayden to her with all the formal politeness he could muster, and presently was standing by amazed at the result.

Himself he was a man immaculately neat in attire under whatever circumstances fortune might be using him, and he had all of a tidy man's contempt for squalor in clothes. Hayden was a very scarecrow. Bandages served him for boots, his puttees were frills of rag, his breeches and shirt were of a coarse native cloth, vilely tailored, coat he had none, his helmet was a mere sack of broken tinkling splinters of pith, and on his face there sprouted an unkempt beard which had never known scissors.

Madame, as has been noted above, was immaculate—a fashion block, as it were, in the desert. Oil and water, thought Kettle, could have no more chance of blending. But lo, in a minute, the pair of them had strolled off together on mutual invitation, and to look at them they might have had a year's intimacy as the ground-work of their talk. The curse of Babel, indeed, put many hindrances, one would have thought, on their interchange of ideas, as madame spoke but little English and Hayden had no other speech; but the Volapuk of the eyes more than made up the difference. Kettle stared after them in their stroll with open-eyed amazement. "By James," he told himself, "the pair of them have gone and fallen in love with one another first bat-off, and that's what's the matter. By James, here's a go!"

In a minute, the pair of them had strolled

off together on mutual invitation.

It was truly an unlooked-for complication. Indeed, who would have thought that a British officer could possibly have an affair of this sort with a female smuggler of another nation, whom, had she been of a different sex, he would have blithely hanged or shot on sight. However, the vagaries of Cupid are beyond calculation, and presently when Doctor Pat (who gathered that there was to be no war) strolled up, he, after a very short study, pronounced that it was "a case," and volunteered that he never knew Hayden "to be one of that sort before." However, as he announced that if the lady hadn't been taken up he should have gone for her himself, his opinion could hardly be looked upon as unprejudiced.

The three of them that night, after madame had retired, held a council of war.

"I'm thinking," said Hayden, "that we've been out here on the warpath long enough. The Mullah seems quiet for the time being. We haven't heard of the old blackguard cutting up anybody for over a week now. I think we'd better march down to the coast for orders."

"What about me?" asked Kettle.

"Oh, you'll come, too, I'm sure, won't you?"

There are some invitations which amount to commands. Captain Kettle wished there to be no doubt about his independence of action. "I should like to see any one in this section of Africa make me move where I didn't intend going."

"Quite so," said Hayden placidly. "But I'm beginning to fancy that you and I are after the same job, though we didn't seem to tumble to it before. I've been talking to madame."

"I thought you were," said the little sailor, whereupon the Irish doctor roared.

"Pat," said his superior officer, with a crimson face, "I'll wring your nasty little neck for you if you don't shut up. Of course, it remains to be seen what is to become of the loot."

"Not at all," said Kettle. "That's mine. The Resident offered it to me if I could lay hands upon it."

"I suppose he thought it was a man's property," said Hayden pointedly.

"I'm not in the least responsible for his thoughts," said Kettle with open truculence. "It's those guns and those cartridges I came out here to get, and at present they're mine both by promise and by right of capture. Sirs, both, I wish you good night."

In these minds, then, the party of them set off on the return march back to the coast, and a brighter and more charming companion than madame could not have been found within all the marches of Africa. Twice they had to fight their way, and the lady showed so gallant a front as to win even the approbation of that connoisseur of battle, Captain Owen Kettle. Hayden remained openly the devout lover, and as for Doctor Pat, he warned both of his male white companions, in plain Irish, that if they fell professionally under his hands he should speedily make a vacancy for himself.

"We shan't be able to get married yet awhile," the lady said to Kettle, when they halted for their last camp before reaching the coast. "Cecil says"—it appeared that Cecil was the Christian name of Hayden—"that he has practically nothing beyond his pay. But I can't grumble at that, because, of course if he had means, he would never have been seconded from his regiment to come out here, and then I should never have met him at all. So we must remain engaged for a while till I can put together a little dot for myself."

"Then you have nothing, too, madame?"

"Oh, dear no. All my remaining cash was sunk in those guns and cartridges—your guns, Captain. But don't think I mind. You won them most fairly. And I have to thank you—and my petticoats—that I didn't get hanged into the bargain."

Captain Kettle sighed. He was thinking of his wife and daughters at home. But even for them he had some niceness as to how he earned the money which was necessary for their support, and there were places where he had to draw the line. Apparently one such had occurred here.

Next morning he was missing from the camp, and in his place was a letter addressed to the British Resident in the coast town which lay against the baking levels of the Red Sea below the hills.

Sir (it ran)—

I carried out your instructions with full diplomatic carefulness. Your Mr. Mullah will not get those rifles which I have annexed, as per verbal instructions. The Other Power has got its nose pulled. Had no opportunity to obliterate head of expedition as suggested, she proving to be a female. She having arranged to marry your Mr. Hayden when they get a small pile together, should be glad if you would tell her she may have rifles, etc., from me as a present, I having looted them honestly as per your instructions.

Sir, I have the honour to be

Yours truly,

O. Kettle (Master, retired).

H.E. the British Resident.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.