RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

A Master of Fortune, 1898,

with "The Fire And The Farm"

THE quartermaster knocked smartly, and came into the chart-house, and Captain Kettle's eyes snapped open from deep sleep to complete wakefulness.

"There's some sort of vessel on fire, sir, to loo'ard, about five miles off."

The shipmaster glanced up at the tell-tale compass above his head. "Officer of the watch has changed the course, I see. We're heading for it, eh?"

"Yes, sir. The second mate told me to say so."

"Quite right. Pass the word for the carpenter, and tell him to get port and starboard lifeboats ready for lowering in case they're wanted. I'll be on the bridge in a minute."

"Aye, aye, sir," said the quartermaster, and withdrew into the darkness outside.

Captain Owen Kettle's toilet was not of long duration. Like most master mariners who do business along those crowded steam lanes of the Western Ocean, he slept in most of his clothes when at sea as a regular habit, and in fact only stripped completely for the few moments which were occupied by his morning's tub. If needful, he could always go out on deck at a second's notice, and be ready to remain there for twenty-four hours. But in this instance there was no immediate hurry, and so he spent a full minute and a half over his toilet, and emerged with washed hands and face.

Sprucely brushed hair and beard, and his person attired in high rubber thigh-boots and leather-bound black oilskins.

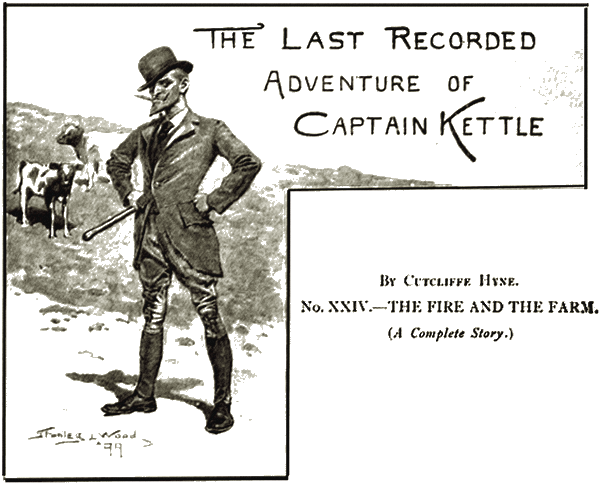

Kettle in his oilskins.

The night was black and thick with a drizzle of rain, and a heavy breeze snored through the Flamingo's scanty rigging. The second mate on the bridge was beating his fingerless woollen gloves against his ribs as a cure for cold fingers. The first mate and the third had already turned out, and were on the boatskids helping the carpenter with the housings, and overhauling davit falls. On that part of the horizon against which the Flamingo's bows sawed with great sweeping dives was a streaky, flickering yellow glow.

Kettle went on to an end of the bridge and peered ahead through the bridge binoculars. "A steamer," he commented, "and a big one too; and she's finely ablaze. Not much help we shall be able to give. It will be a case of taking off the crew, if they aren't already cooked before we get there." He looked over the side at the eddy of water that clung to the ship's flank. "I see you're shoving her along," he said to the second mate.

"I sent word down to the engine-room to give her all they knew the moment we raised the glow. I thought you wouldn't grudge the coal, sir."

"No, quite right. Hope there aren't too many of them to be picked off, or we shall make a tight fit on board here."

"Funny we should be carrying the biggest cargo the old boat's ever had packed into her. But we shall find room to house a few poor old sailormen. They won't mind much where they stow, as long as they're picked up out of the wet. B-r-r-rh!" shivered the second mate, "I shouldn't much fancy open-boat cruising in the Western Ocean this weather."

Captain Kettle stared on through the shiny brass binoculars. "Call all hands," he said quietly. "That's a big ship ahead of us, and she'll carry a lot of people. God send she's only an old tramp. At those lifeboats there!" he shouted. "Swing the davits outboard, and pass your painters forward. Hump yourselves, now."

"There's a lot of ice here, sir," came a grumbling voice out of the darkness, "and the boats are frozen on to the chocks. We've got to hammer it away before they'll hoist. The falls are that froze, too, that they'll not render—"

"You call yourself a mate and hold a master's ticket, and want to get a ship of your own!"—Kettle vaulted over the rail on to the top of the fiddley, and made for his second in command. "Here, my man, if your delicate fingers can't do this bit of a job, give me that marlinspike. By James! do you hear me? Give up the marlinspike. Did you never see a boat iced up before? Now then, carpenter. Are you worth your salt? Or am I to clear both ends in this boat by myself?"

So, by example and tongue. Captain Kettle got his boats swung outboard, and the Flamingo, with her engines working at an unusual strain, surged rapidly nearer and nearer to the blaze.

On shore a house on fire at any hour draws a crowd. At sea, in the bleak cold wastes of the water desert, even one other shipload of sympathizers is too often wished for vainly. Wind, cold, and breakdowns of machinery the sailor accepts with dull indifference; shipwrecks, strandings, and disease he looks forward to as part of an inevitable fate; but fire goes nearer to cowing him than all other disasters put together; and the sight of his fellow-seamen attacked by these same desolating flames arouses in him the warmest of his sympathy, and the full of his resourcefulness. Moreover, in Kettle's case, he had known the feel of a ship afire under his own feet, and so he could appreciate all the better the agony of these others.

But meanwhile, as the Flamingo made her way up wind against the charging seas, a fear was beginning to grip the little shipmaster by the heart that was deep enough to cause him a physical nausea.

The burning steamer ahead grew every minute more clear as they raced toward her. She was on fire forward, and she lay almost head-on toward them, keeping her stern to the seas, so that the wind would have no help in driving the flames aft, and making her more uninhabitable.

From a distance it had been hard to make out anything beyond great stacks of yellow flame, topped by inky, oily smoke, which drove in thick columns own the wind. As they drew nearer, and her size became more apparent, some one guessed her as a big cargo tramp from New Orleans with cotton that had overheated and fired, and Kettle took comfort from the suggestion and tried to believe that it might come true.

But as they closed with her, and came within earshot of her siren, which was sending frightened useless blares across the churning waters, there was no being blind to the true facts any longer. This was no cargo boat, but a passenger liner; outward bound, too, and populous. And as they came still nearer, they saw her after-decks black and wriggling with people, and Kettle got a glimpse of her structure and recognized the vessel herself.

"The Grosser Carl," he muttered, "out of Hamburg for New York. Next to no first-class, and she cuts rates for third and gets the bulk of the German emigrant traffic. She'll have six hundred on her this minute, and a hundred of a crew. Call it seven hundred all told, and there's hell waiting for them over yonder, and getting worse every minute. Oh, great James! I wonder what's going to be done. I couldn't pack seventy of them on the old Flam here, if I filled her to bursting."

He clapped the binoculars to his eyes again, and stared diligently round the rim of the night. If only he could catch a glimpse of some other liner hurrying along her route, then these people could be saved easily. He could drop his boats to take them till the other passenger ship came up. But the wide sea was empty of lights; the Flamingo and the Grosser Carl had the stage severely to themselves; and between them they had the making of an intolerable weight of destiny.

The second mate broke in upon his commander's brooding. "We shall have a nice bill for Lloyds this journey."

Kettle made no answer. He continued staring moodily at the spouting flames ahead. The second mate coughed. "Shall I be getting derricks rigged and the hatch covers off?"

Kettle turned on him with a sudden fierceness. "Do you know you're asking me to ruin myself?"

"But if we jettison cargo to make room for these poor beggars, sir, the insurance will pay."

"Pay your grandmother. You've got a lot to learn, my lad, before you're fit to take charge of a ship, if you don't know any more than that about the responsibility of the cargo."

"By Jove! that's awkward. Birds would look pretty blue if the bill was handed in to them."

"Birds!" said Kettle with contempt. "They aren't liable for sixpence. Supposing you were travelling by train, and there was some one else's portmanteau in the carriage, and you flung it out of the window into a river, who do you suppose would have to stand the racket?"

"Why, me. But then, sir, this is different."

"Not a bit. If we start in to jettison cargo, it means I'm a ruined man. Every ton that goes over the side I'll have to pay for."

"We can't leave those poor devils to frizzle," said the second mate awkwardly.

"Oh, no, of course we can't. They're a pack of unclean Dutchmen we never saw before, and should think ourselves too good to brush against if we met them in the street, but sentiment demands that we stay and pull them out of their mess, and cold necessity leaves me to foot the bill. You're young, and you're not married, my lad. I'm neither. I've worked like a horse all my life, mostly with bad luck. Lately luck's turned a bit. I've been able to make a trifle more, and save a few pounds out of my billets. And here and there, what with salvage and other things, I've come in the way of a plum. One way and another I've got nearly enough put by at home this minute to keep the missis and me and the girls to windward of the workhouse, even if I lost this present job with Birds, and didn't find another."

"Perhaps somebody else will pay for the cargo we have to put over the side, sir."

"It's pretty thin comfort when you've got a 'perhaps' of that size, and no other mortal stop between you and the workhouse. It's all very well doing these things in hot blood; but the reckoning's paid when you're cold, and they're cold, and with the Board of Trade standing-by like the devil in the background all ready to give you a kick when there's a spare place for a fresh foot." He slammed down the handle of the bridge-telegraph, and rang off the Flamingo's engines. He had been measuring distances all this time with his eye.

"But, of course, there's no other choice about the matter. There's the blessed cause of humanity to be looked after—humanity to these blessed Dutch emigrants that their own country doesn't want, and every other country would rather be without. Humanity to my poor old missis and the kids doesn't count. I shall get a sludgy paragraph in the papers for the Grosser Carl, headed 'Gallant Rescue,' with all the facts put upside down, and twelve months later there'll be another paragraph about a 'case of pitiful destitution.'"

"Oh, I say, sir, it won't be as bad as all that. Birds will see you through."

"Birds will do a fat lot. Birds sent me to work up a connection in the Mexican Gulf, and I've done it, and they've raised my screw two pound a month after four years' service. I jettison the customers' cargo, and probably sha'n't be able to pay for half of it. Customers will get mad, and give their business to other lines which don't run foul of blazing emigrant packets."

"Birds would never dare to fire you out for that."

"Oh, Lord, no! They'd say: 'We don't like the way you've taken to wear your back hair, Captain. And, besides, we want younger blood amongst our skippers. You'll find your check ready for you in the outer office. Mind the step!'"

"I'm awfully sorry, Skipper. If there's anything I can do, sir—"

Captain Kettle sighed, and looked drearily out at the blazing ship and the tumbled waste of sea on which she floated. But he felt that he had been showing weakness, and pulled himself together again smartly. "Yes, there is, my lad. I'm a disappointed man, and I've been talking a lot more than's dignified. You'll do me a real kindness if you'll forget all that's been said. Away with you on to the main deck, and get hatches off, and whip the top tier of that cargo over the side as fast as you can make the winches travel. If the old Flamingo is going to serve out free hospitality, by James! she shall do it full weight. By James! I'd give the beggars champagne and spring mattresses if I'd got 'em."

Meanwhile, those on the German emigrant steamer had seen the coming of the shabby little English trader with bumping hearts. Till then the crew, with (so to speak) their backs up against a wall, had fought the fire with diligence; but when the nearness of a potential rescuer was reported, they discovered for themselves at once that the fire was beyond control. They were joined by the stokehold gangs, and they made at once for the boats, overpowering any officer who happened to come between them and their desires. The limp, tottery, half-fed, wholly seasick emigrants they easily shoved aside, and these in their turn by sheer mass thrust back the small handful of first-class passengers, and away screamed out the davit tackles, as the boats were lowered full of madly frightened deck hands and grimy handlers of coal.

Panic had sapped every trace of their manhood. They had concern only for their own skins; for the miserables remaining on the Grosser Carl they had none. And if for a minute any of them permitted himself to think, he decided that in the Herr Gott's good time the English would send boats and fetch them off. The English had always a special gusto for this meddling rescue work.

However, it is easy to decide on lowering boats, but not always so easy to carry it into safe fact if you are mad with scare, and there is no one whom you will listen to to give the necessary simple orders. And, as a consequence, one boat, chiefly manned by the coal interest, swamped alongside before it could be shoved clear; the forward davit fall of another jammed, and let it dangle vertically up and down when the after fall overhauled; and only one boat got away clear.

The reception which this small cargo of worthies met with surprised them. They pulled with terrified haste to the Flamingo, got under her lee, and clung desperately to the line which was thrown to them. But to the rail above them came the man who expected to be ruined by this night's work, and the pearls of speech which fell from his lips went home through even their thick hides.

Captain Kettle, being human, had greatly needed some one during the last half-hour to ease his feelings on—though he was not the man to own up to such a weakness, even to himself—and the boat came neatly to supply his want. It was long enough since he had found occasion for such an outburst, but the perfection of his early training stood him in good stead then. Every biting insult in his vocabulary, every lashing word that is used upon the seas, every gibe, national, personal, or professional, that a lifetime of hard language could teach, he poured out on that shivering boat's crew then.

They were Germans certainly, but being an English shipmaster, he had, of course, many a time sailed with a forecastle filled with their nationality, and had acquired the special art of adapting his abuse to the "Dutchman's" sensibilities, even as he had other harangues suited for Coolie or Dago mariners, or even for that rare sea-bird, the English sailorman. And as a final wind-up, after having made them writhe sufficiently, he ordered them to go back whence they came, and take a share in rescuing their fellows.

"Bud we shall trown," shouted back one speaker from the wildly jumping boat.

"Then drown, and be hanged to you," shouted Kettle. "I'm sure I don't care if you do. But I'm not going to have cowards like you dirtying my deck-planks." He cast off the line to which their boat rode under the steamer's heaving side. "You go and do your whack at getting the people off that packet, or, so help me James! none of you shall ever see your happy Dutchland again."

Meanwhile, so the irony of the fates ordered it, the two mates, each in charge of one of the Flamingo's lifeboats, were commanding crews made up entirely of Germans and Scandinavians, and pluckier and more careful sailormen could not have been wished for. The work was dangerous, and required more than ordinary nerve and endurance and skill. A heavy sea ran, and from its crests a spindrift blew which cut the face like whips, and numbed all parts of the body with its chill. The boats were tossed about like playthings, and required constant bailing to keep them from being waterlogged. But Kettle had brought the Flamingo to windward of the Grosser Carl, and each boat carried a line, so that the steam winches could help her with the return trips.

Getting a cargo was, however, the chief difficulty. All attempt at killing the fire was given up by this time. All vestige of order was swamped in unutterable panic. The people on board had given themselves up to wild, uncontrollable anarchy. If a boat had been brought alongside, they would have tumbled into her like sheep, till their numbers swamped her. They cursed the flames, cursed the sea, cursed their own brothers and sisters who jostled them. They were the sweepings from half-fed middle Europe, born with raw nerves; and under the sudden stress of danger, and the absence of some strong man to thrust discipline on them, they became practically maniacs. They were beyond speech, many of them. They yammered at the boats which came to their relief, with noises like those of scared beasts.

Now the Flamingo's boats were officered by two cool, profane mates, who had no nerves themselves, and did not see the use of nerves in other people. Neither of them spoke German, but (after the style of their island) presuming that some of those who listened would understand English, they made proclamation in their own tongue to the effect that the women were to be taken off first.

"Kids with them," added the second mate.

"And if any of you rats of men shove your way down here," said the chief mate, "before all the skirt is ferried across, you'll get knocked on the head, that's all. Savvy that belaying-pin I got in my fist? Now then, get some bowlines, and sway out the ladies."

As well might the order have been addressed to a flock of sheep. They heard what was said in an agonized silence. Then each poor soul there stretched out his arms or hers, and clamored to be saved—and—never mind the rest. And meanwhile the flames bit deeper and deeper into the fabric of the steamer, and the breath of them grew more searching, as the roaring gale blew them into strength.

"You ruddy Dutchmen," shouted the second mate. "It would serve you blooming well right if you were left to be frizzled up into one big sausage stew together. However, we'll see if kindness can't tame you a bit yet." He waited till the swirl of a sea swung his boat under one of the dangling davit falls, and caught hold of it, and climbed nimbly on board. Then he proceeded to clear a space by the primitive method of crashing his fist into every face within reach.

He proceeded to clear a space by crashing

his fist into every face within reach.

"Now then," he shouted, "if there are any sailormen here worth their salt, let them come and help. Am I to break up the whole of this ship's company by myself?"

Gradually, by ones and twos, the Grosser Carl's remaining officers and deck hands came shamefacedly toward this new nucleus of authority and order, and then the real work began. The emigrants, with sea sights and sea usage new to them, were still full of the unreasoning panic of cattle, and like cattle they were herded and handled, and their women and young cut out from the general mob. These last were got into the swaying, dancing boats as tenderly as might be, and the men were bidden to watch, and wait their turn. When they grew restive, as the scorching fire drew more near, they were beaten savagely; the Grosser Carl's crew, with the shame of their own panic still raw on them, knew no mercy; and the second mate of the Flamingo, who stood against a davit, insulted them all with impartial cheerfulness. He was a very apt pupil, this young man, of that master of ruling men at the expense of their feelings, Captain Owen Kettle.

Meanwhile the two lifeboats took one risky journey after another, being drawn up to their own ship by a chattering winch, discharging their draggled freight with dexterity and little ceremony, and then laboring back under oars for another. The light of the burning steamer turned a great sphere of night into day, and the heat from her made the sweat pour down the faces of the toiling men, though the gale still roared, and the icy spindrift still whipped and stung. On the Flamingo, Captain Kettle cast into the sea with a free hand what represented the savings of a lifetime, provision for his wife and children, and an old-age pension for himself.

The Grosser Carl had carried thirty first-class passengers, and these were crammed into the Flamingo's slender cabin accommodation, filling it to overflowing. The emigrants—Austrians, Bohemians, wild Poles, filthy, crawling Russian Jews, bestial Armenians, human debris which even soldier-coveting Middle Europe rejected—these were herded down into the holds, as rich cargo was dug out by the straining winches, and given to the thankless sea to make space for them.

"Kindly walk up," said Kettle, with bitter hospitality, as fresh flocks of them were heaved up over the bulwarks. "Don't hesitate to grumble if the accommodation isn't exactly to your liking. We're most pleased to strike out cargo to provide you with an elegant parlor, and what's left I'm sure you'll be able to sit on and spoil. Oh, you filthy, long-haired cattle! Did none of you ever wash?"

Fiercely the Grosser Carl burned to the fanning of the gale, and like furies worked the men in the boats. The Grosser Carl's own boat joined the other two, once the ferrying was well under way. She had hung alongside after Kettle cast off her line, with her people madly clamoring to be taken on board; but as all they received for their pains was abuse and coal- lumps—mostly, by the way, from their own fellow-countrymen, who made up the majority of the Flamingo's crew—they were presently driven to help in the salving work through sheer scare at being left behind to drown unless they carried out the fierce little English Captain's orders.

The Flamingo's chief mate oversaw the dangerous ferrying, and though every soul that was transshipped might be said to have had ten narrow escapes in transit over that piece of tossing water, luck and good seamanship carried the day, and none was lost. And on the Grosser Carl the second mate, a stronger man, brazenly took entire command, and commended to the nether gods all who suggested ousting him from that position. "I don't care what your official post was on this ship before I came," said the second mate to several indignant officers. "You should have held on to it when you had it. I've never been a skipper before, but I'm skipper here now by sheer right of conquest, and I'm going to stay on at that till the blooming old ship's burnt out. If you bother me, I'll knock your silly nose into your watch-pocket. Turn-to there and pass down another batch of those squalling passengers into the boats. Don't you spill any of them overboard either, or, by the Big Mischief, I'll just step down and teach you handiness."

"I don't care what your official post was," said

the second mate to several indignant officers.

The second mate was almost fainting with the heat before he left the Grosser Carl, but he insisted on being the last man on board, and then guyed the whole performance with caustic gayety when he was dragged out of the water, into which he had been forced to jump, and was set to drain on the floor gratings of a boat.

The Grosser Carl had fallen away before the wind, and was spouting flame from stem-head to poop-staff by the time the last of the rescuers and the rescued were put on the Flamingo's deck, and on that travel-worn steamboat were some six hundred and fifty visitors that somehow or other had to be provided for.

The detail of famine now became of next importance. They were still five days' steam away from port, and their official provision supply was only calculated to last the Flamingos themselves for a little over that time. Things are cut pretty fine in these days of steam voyages to scheduled time. So there was no sentimental waiting to see the Grosser Carl finally burn out and sink. The boats were cast adrift, as the crews were too exhausted to hoist them in, and the Flamingo's nose was turned toward Liverpool. Pratt, the chief engineer, figured out to half a ton what coal he had remaining, and set the pace so as to run in with empty bunkers. They were cool now, all hands, from the excitement of the burning ship, and the objectionable prospect of semi-starvation made them regard their visitors less than ever in the light of men and brothers.

But, as it chanced, toward the evening of next day, a hurrying ocean greyhound overtook them in her race from New York toward the East, and the bunting talked out long sentences in the commercial code from the wire span between the Flamingo's masts. Fresh quartettes of flags flicked up on both steamers, were acknowledged, and were replaced by others; and when the liner drew up alongside, and stopped with reversed propellers, she had a loaded boat ready swung out in davits, which dropped in the water the moment she had lost her way. The bunting had told the pith of the tale.

When the two steamers' bridges were level, the liner's captain touched his cap, and a crowd of well-dressed passengers below him listened wonderingly. "Afternoon, Captain. Got 'em all?"

"Afternoon, Captain. Oh, we didn't lose any. But a few drowned their silly selves before we started to shepherd them."

"What ship was it? The French boat would be hardly due yet."

"No, the old Grosser Carl. She was astern of her time. Much obliged to you for the grub, Captain. We'd have been pretty hard pushed if we hadn't met you. I'm sending you a payment order. Sorry for spoiling your passage."

The liner captain looked at his watch.

"Can't be helped. It's in a good cause, I suppose, though the mischief of it is we were trying to pull down the record by an hour or so. The boat, there! Are you going to be all night with that bit of stuff?"

The cases of food were transshipped with frantic haste, and the boat returned. The greyhound leaped out into her stride again the moment she had hooked on, and shot ahead, dipping a smart blue ensign in salute. The Flamingo dipped a dirty red ensign and followed, and, before dark fell, once more had the ocean to herself.

The voyage home was not one of oppressive gayety. The first-class passengers, who were crammed into the narrow cabin found the quarters uncomfortable, and the little shipmaster's manner repellent. Urged by the precedent in such matters, they "made a purse" for him, and a presentation address. But as they merely collected some thirty-one pounds in paper promises, which, so far, have never been paid, their gratitude may be said to have had its economical side.

To the riffraff in the hold, for whose accommodation a poor man's fortune had been jettisoned, the thing "gratitude" was an unknown emotion. They plotted mischief amongst themselves, stole when the opportunity came to them, were unspeakably foul in their habits, and, when they gave the matter any consideration at all, decided that this fierce little captain with the red torpedo beard had taken them on board merely to fulfil some selfish purpose of his own. To the theorist who has sampled them only from a distance, these off-scourings of Middle Europe are downtrodden people with souls; to those who happen to know them personally, all their qualities seem to be conspicuously negative.

The Flamingo picked up the landmarks of the Southern Irish coast, and made her number to Lloyd's station on Brow Head, stood across for the Tuskar, and so on up St. George's Channel for Holyhead. She flew a pilot jack there, and off Point Lynus picked up a pilot, who, after the custom of his class, stepped up over the side with a hard felt hat on his head, and a complete wardrobe, and a selection of daily papers in his pocket.

"Well, pilot, what's the news?" said Kettle, as the man of narrow waters swung himself up on to the bridge, and his boat swirled away astern.

"You are," said the pilot. "The papers are just full of you, Captain, all of them, from the Shipping Telegraph to the London Times. The Cunard boat brought in the yarn. A pilot out of my schooner took her up."

"How do they spell the name? Cuttle?"

"Well, I think it's 'Kattle' mostly, though one paper has it 'Kelly.'"

"Curse their cheek," said the little sailor, flushing. "I'd like to get hold of some of those blowsy editors that come smelling round the dock after yarns and drink, and wring their necks."

"Starboard a point," said the pilot, and when the quartermaster at the wheel had duly repeated the course, he turned to Kettle with some amusement. "Blowsy or not, they don't seem to have done you much harm this journey, Captain. Why, they're getting up subscriptions for you all round. Shouldn't wonder but what the Board of Trade even stands you a pair of binoculars."

"I'm not a blessed mendicant," said Kettle stiffly, "and as for the Board of Trade, they can stick their binoculars up their trousers." He walked to the other end of the bridge, and stood there chewing savagely at the butt end of his cigar.

"Rum bloke," commented the pilot to himself, though aloud he offered no comment, being a man whose business it was to keep on good terms with everybody. So he dropped his newspapers to one of the mates, and applied himself to the details of the pilotage.

Still, the pilot was right in saying that England was ringing with the news of Kettle's feat. The passengers of the Cunarder, with nothing much else to interest them, had come home thrilled and ringing with it. A smart New Yorker had got a "scoop" by slipping ashore at Queenstown and cabling a lavish account to the American Press Association, so that the first news reached London from the States. Followed Reuter's man and the Liverpool reporters on Prince's landing-stage, who came to glean copy as in the ordinary course of events, and they being spurred on by wires from London for full details, got down all the facts available, and imagined others. Parliament was not sitting, and there had been no newspaper sensation for a week, and, as a natural consequence, the papers came out next morning with accounts of the rescue varying from two columns to a page in length.

It is one of the most wonderful attributes of the modern Press that it can, at any time between midnight and publishing hours, collate and elaborate the biography of a man who hitherto has been entirely obscure, and considering the speed of the work, and the difficulties which hedge it in, these lightning life sketches are often surprisingly full of accuracies. But let the frillings in this case be fact or fiction, there was no doubt that Kettle and his crew had saved a shipload of panic-stricken foreign emigrants, and (to help point the moral) within the year, in an almost similar case, another shipload had been drowned through that same blind, helpless, hopeless panic. The pride of race bubbled through the British Daily Press in prosaic long primer and double-leaded bourgeois. There was no saying aloud, "We rejoice that an Englishman has done this thing, after having it proved to us that it was above the foreigner's strength." The newspaper man does not rhapsodize. But the sentiment was there all the same, and it was that which actuated the sudden wave of enthusiasm which thrilled the country.

The Flamingo was worked into dock, and a cheering crowd surged aboard of her in unrestrainable thousands. Strangers came up and wrung Kettle's unwilling hand, and dropped tears on his coat-sleeve; and when he swore at them, they only wept the more and smiled through the drops. It was magnificent, splendid, gorgeous. Here was a man! Who said that England would ever lose her proud place among the nations when she could still find men like Oliver Kelly—or Kattle—or Cuttle, or whatever this man was called, amongst her obscure merchant captains?

Strangers came up and wrung Kettle's unwilling hand.

Even Mr. Isaac Bird, managing owner, caught some of the general enthusiasm, and withheld, for the present, the unpleasant remarks which occurred to him as suitable, touching Kettle's neglect of the firm's interest in favor of a parcel of bankrupt foreigners. But Kettle himself had the subject well in mind. When all this absurd fuss was over, then would come the reckoning; and whilst the crowd was cheering him, he was figuring out the value of the jettisoned cargo, and whilst pompous Mr. Isaac was shaking him by the hand and making a neat speech for the ear of casual reporters, poor Kettle was conjuring up visions of the workhouse and pauper's corduroy.

But the Fates were moving now in a manner which was beyond his experience. The public, which had ignored his bare existence before for all of a lifetime, suddenly discovered that he was a hero, and that, too, without knowing half the facts. The Press, with its finger on the public's pulse, published Kettle literature in lavish columns. It gave twenty different "eye- witnesses' accounts" of the rescue. It gave long lists of "previous similar disasters." It drew long morals in leading articles. And finally, it took all the little man's affairs under its consideration, and settled them with a lordly hand.

"Who pays for the cargo Captain Kuttle threw overboard?" one paper headed an article; whilst another wrote perfervidly about "Cattle ruined for his bravery." Here was a new and striking side issue. Lloyds' were not responsible. Should the week's hero pay the bill himself out of his miserable savings? Certainly not. The owners of the Grosser Carl were the benefiting parties, and it was only just that they should take up the expense. So the entire Press wired off to the German firm, and next morning were able to publish a positive assurance that of course these grateful foreigners would reimburse all possible outlay.

The subject of finance once broached, it was naturally discovered that the hero toiled for a very meagre pittance, that he was getting on in years, and had a wife and family depending on him—and—promptly, there opened out the subscription lists. People were stirred, and they gave nicely, on the lower scale certainly, with shillings and guineas predominating; but the lists totalled up to £2,400, which to some people, of course, is gilded affluence.

Now Captain Kettle had endured all this publicity with a good deal of restiveness, and had used language to one or two interviewers who managed to ferret him out, which fairly startled them; but this last move for a public subscription made him furious. He spoke in the captain's room of the hostelry he used, of the degradation which was put on him, and various other master mariners who were present entirely agreed with him. "I might be a blessed missionary, or India-with-a-famine, the way they're treating me," he complained bitterly. "If they call a meeting to give me anything, I'll chuck the money in their faces, and let them know straight what I think. By James! do they suppose I've got no pride? Why can't they let me alone? If the Grosser Carl people pay up for that cargo, that's all I want."

But the eternal healer, Time, soothed matters down wonderfully. Captain Owen Kettle's week's outing in the daily papers ran its course with due thrills and headlines, and then the Press forgot him, and rushed on to the next sensation. By the time the subscription list had closed and been brought together, the Flamingo had sailed for her next slow round trip in the Mexican Gulf, and when her captain returned to find a curt, formal letter from a firm of bankers, stating that £2,400 had been placed to his credit in their establishment, he would have been more than human if he had refused it. And, as a point of fact, after consulting with Madam, his wife, he transformed it into houses in that terrace of narrow dwellings in Birkenhead which represented the rest of his savings.

Now on paper this house property was alleged by a sanguine agent to produce at the rate of £15 per annum apiece, and as there were thirty-six houses, this made an income—on paper—of well over £500 a year, the which is a very nice possession.

A thing, moreover, which Captain Kettle had prophesied had come to pass. The "trade connection" in the Mexican Gulf had been very seriously damaged. As was somewhat natural, the commercial gentry there did not relish having their valuable cargo pitched unceremoniously to Neptune, and preferred to send what they had by boats which did not contrive to meet burning emigrant liners. This, of course, was quite unreasonable of them, but one can only relate what happened.

And then the second part of the prophecy evolved itself naturally. Messrs. Bird discovered from the last indent handed them that more paint had been used over the Flamingo's fabric than they thought consistent with economy, and so they relieved Captain Kettle from the command, handed him their check for wages due—there was no commission to be added for such an unsatisfactory voyage as this last—and presented him gratis with their best wishes for his future welfare.

Kettle had thought of telling the truth in print, but the mysterious law of libel, which it is written that all mariners shall dread and never understand, scared him; and besides, he was still raw from his recent week's outing in the British Press. So he just went and gave his views to Mr. Isaac Bird personally and privately, threw the ink-bottle through the office window, pitched the box of business cigars into the fire, and generally pointed his remarks in a way that went straight to Mr. Bird's heart, and then prepared peacefully to take his departure.

He gave his views to Mr. Isaac Bird personally and privately.

"I shall not prosecute you for this—" said Mr. Isaac.

"I wish you dare. It would suit me finely to get into a police- court and be able to talk. I'd willingly pay my 'forty shillings and' for the chance. They'd give me the option fast enough."

"I say I shall not prosecute you because I have no time to bother with law. But I shall send your name round amongst the ship- owners, and with my word against you, you'll never get another command so long as the world stands."

"You knock-kneed little Jew," said Kettle truculently, "do you think I'm giving myself the luxury of letting out at a shipowner, after knuckling down to the breed through all of a weary life, unless I knew my ground? I've done with ships and the sea for always, and if you give me any more of your lip, I'll burn your office down and you in it."

"You seem pleased enough with yourself about something," said Mr. Isaac.

"I am," said Kettle exultantly. "I've chucked the sea for good. I've taken a farm in Wharfedale, and I'm going to it this very week."

"Then," said Mr. Isaac sardonically, "if you've taken a farm, don't let me wish you any further ill. Good-morning."

But Kettle was not to be damped out of conceit with his life's desire by a few ill-natured words. He gave Mr. Isaac Bird his final blessing, commenting on his ancestors, his personal appearance, his prospects of final salvation, and then pleasantly took his leave. He was too much occupied in the preliminaries of his new life to have much leisure just then for further cultivation of the gentle art of insult.

The farm he had rented lay in the Wharfe Valley above Skipton, and, though its acreage was large, a good deal was made up of mere moorland sheep pasture. Luckily he recognized that a poetical taste for a rural life might not necessarily imply the whole mystery of stock rearing and agriculture, and so he hired a capable foreman as philosopher and guide. And here I may say that his hobby by no means ruined him, as might reasonably be expected; for in the worst years he never dropped more than fifty or sixty pounds, and frequently he ran the place without loss, or even at a profit.

But though it is hard to confess that a man's ideal comes short of his expectations when put to the trial, I am free to confess that although he enjoyed it all, Kettle was not at his happiest when he was attending his crops or his sheep, or haggling with his fellow farmers on Mondays over fat beasts in Skipton market.

He had gone back to one of his more practiced tastes—if one calls it a taste—the cultivation of religion. The farm stood bleak and lonely on the slope of a hillside, and on both flanks of the dale were other lonely farms as far as the eye could see. There was no village. The nearest place of worship was four miles away, and that was merely a church. But in the valley beside the Wharfe was a small gray stone chapel, reared during some bygone day for the devotions of some forgotten sect. Kettle got this into his control.

He was by no means a rich man. The row of houses in Birkenhead were for the most part tenanted by the wives of mercantile marine engineers and officers, who were chronically laggard with their rent, and whom esprit de corps forbade him to press; and so, what with this deficit, and repairs and taxes, and one thing and another, it was rarely that half the projected £500 a year found its way into his banking account. But a tithe of whatever accrued to him was scrupulously set aside for the maintenance of the chapel.

He imported there the grim, narrow creed he had learned in South Shields, and threw open the door for congregations. He was entirely in earnest over it all, and vastly serious. Failing another minister, he himself took the services, and though, on occasion, some other brother was induced to preach, it was he himself who usually mounted the pulpit beneath the sounding- board. He purchased an American organ, and sent his eldest daughter weekly to take lessons in Skipton till she could play it. And Mrs. Kettle herself led the singing.

Still further, the chapel has its own collection of hymns, specially written, printed and dedicated to its service. The book is Captain Kettle's first published effort. Heaven and its author alone know under what wild circumstances most of those hymns were written.

The chapel started its new span of life with a congregation meagre enough, but Sunday by Sunday the number grew. They are mostly Nonconformists in the dales, and when once a man acquires a taste for dissent, he takes a sad delight in sampling his neighbors' variations of creed. Some came once and were not seen again. Others came and returned. They felt that this was the loneliest of all modern creeds; indeed, Kettle preached as much, and one can take a melancholy pride in splendid isolation.

I am not sure that Captain Kettle does not find the restfulness of his present life a trifle too accentuated at times, though this is only inevitable for one who has been so much a man of action. But at any rate he never makes complaint. He is a strong man, and he governs himself even as he governs his family and the chapel circle, with a strong, just hand. The farm is a model of neatness and order; paint is lavished in a way that makes dalesmen lift their eyebrows; and the routine of the household is as strict as that of a ship.

The house is unique, too, in Wharfedale for the variety of its contents. Desperately poor though Kettle might be on many of his returns from his unsuccessful ventures, he never came back to his wife without some present from a foreign clime as a tangible proof of his remembrance, and because these were usually mere curiosities, without intrinsic value, they often evaded the pawn- shop in those years of dire distress, when more negotiable articles passed irretrievably away from the family possession. And with them too, in stiff, decorous frames, are those certificates and testimonials which a master mariner always collects, together with photographs of gratuitously small general interest.

But one might turn the house upside down without finding so carnal an instrument as a revolver, and when I suggested to Kettle once that we might go outside and have a little pistol practice, he glared at me, and I thought he would have sworn. However, he let me know stiffly enough that whatever circumstances might have made him at sea, he had always been a very different man ashore in England, and there the matter dropped.

But speaking of mementoes, there is one link with the past that Mrs. Kettle, poor woman, never ceases to regret the loss of. "Such a beautiful gold watch," she says it was too, "with the Emperor's and the Captain's names engraved together on the back, and just a nice mention of the Gross of Carl." As it happened, I saw the letter with which it was returned. It ran like this:—

The Flamingo was worked into dock, and a cheering crowd surged aboard of her in unrestrainable thousands. Strangers came up and wrung Kettle's unwilling hand, and dropped tears on his coat-sleeve; and when he swore at them, they only wept the more and smiled through the drops. It was magnificent, splendid, gorgeous. Here was a man! Who said that England would ever lose her proud place among the nations when she could still find men like Oliver Kelly—or Kattle—or Cuttle, or whatever this man was called, amongst her obscure merchant captains?

Even Mr. Isaac Bird, managing owner, caught some of the general enthusiasm, and withheld, for the present, the unpleasant remarks which occurred to him as suitable, touching Kettle's neglect of the firm's interest in favor of a parcel of bankrupt foreigners. But Kettle himself had the subject well in mind. When all this absurd fuss was over, then would come the reckoning; and whilst the crowd was cheering him, he was figuring out the value of the jettisoned cargo, and whilst pompous Mr. Isaac was shaking him by the hand and making a neat speech for the ear of casual reporters, poor Kettle was conjuring up visions of the workhouse and pauper's corduroy.

But the Fates were moving now in a manner which was beyond his experience. The public, which had ignored his bare existence before for all of a lifetime, suddenly discovered that he was a hero, and that, too, without knowing half the facts. The Press, with its finger on the public's pulse, published Kettle literature in lavish columns. It gave twenty different "eye- witnesses' accounts" of the rescue. It gave long lists of "previous similar disasters." It drew long morals in leading articles. And finally, it took all the little man's affairs under its consideration, and settled them with a lordly hand.

"Who pays for the cargo Captain Kuttle threw overboard?" one paper headed an article; whilst another wrote perfervidly about "Cattle ruined for his bravery." Here was a new and striking side issue. Lloyds' were not responsible. Should the week's hero pay the bill himself out of his miserable savings? Certainly not. The owners of the Grosser Carl were the benefiting parties, and it was only just that they should take up the expense. So the entire Press wired off to the German firm, and next morning were able to publish a positive assurance that of course these grateful foreigners would reimburse all possible outlay.

The subject of finance once broached, it was naturally discovered that the hero toiled for a very meagre pittance, that he was getting on in years, and had a wife and family depending on him—and—promptly, there opened out the subscription lists. People were stirred, and they gave nicely, on the lower scale certainly, with shillings and guineas predominating; but the lists totalled up to £2,400, which to some people, of course, is gilded affluence.

Now Captain Kettle had endured all this publicity with a good deal of restiveness, and had used language to one or two interviewers who managed to ferret him out, which fairly startled them; but this last move for a public subscription made him furious. He spoke in the captain's room of the hostelry he used, of the degradation which was put on him, and various other master mariners who were present entirely agreed with him. "I might be a blessed missionary, or India-with-a-famine, the way they're treating me," he complained bitterly. "If they call a meeting to give me anything, I'll chuck the money in their faces, and let them know straight what I think. By James! do they suppose I've got no pride? Why can't they let me alone? If the Grosser Carl people pay up for that cargo, that's all I want."

But the eternal healer, Time, soothed matters down wonderfully. Captain Owen Kettle's week's outing in the daily papers ran its course with due thrills and headlines, and then the Press forgot him, and rushed on to the next sensation. By the time the subscription list had closed and been brought together, the Flamingo had sailed for her next slow round trip in the Mexican Gulf, and when her captain returned to find a curt, formal letter from a firm of bankers, stating that £2,400 had been placed to his credit in their establishment, he would have been more than human if he had refused it. And, as a point of fact, after consulting with Madam, his wife, he transformed it into houses in that terrace of narrow dwellings in Birkenhead which represented the rest of his savings.

Now on paper this house property was alleged by a sanguine agent to produce at the rate of £15 per annum apiece, and as there were thirty-six houses, this made an income—on paper—of well over £500 a year, the which is a very nice possession.

A thing, moreover, which Captain Kettle had prophesied had come to pass. The "trade connection" in the Mexican Gulf had been very seriously damaged. As was somewhat natural, the commercial gentry there did not relish having their valuable cargo pitched unceremoniously to Neptune, and preferred to send what they had by boats which did not contrive to meet burning emigrant liners. This, of course, was quite unreasonable of them, but one can only relate what happened.

And then the second part of the prophecy evolved itself naturally. Messrs. Bird discovered from the last indent handed them that more paint had been used over the Flamingo's fabric than they thought consistent with economy, and so they relieved Captain Kettle from the command, handed him their check for wages due—there was no commission to be added for such an unsatisfactory voyage as this last—and presented him gratis with their best wishes for his future welfare.

Kettle had thought of telling the truth in print, but the mysterious law of libel, which it is written that all mariners shall dread and never understand, scared him; and besides, he was still raw from his recent week's outing in the British Press. So he just went and gave his views to Mr. Isaac Bird personally and privately, threw the ink-bottle through the office window, pitched the box of business cigars into the fire, and generally pointed his remarks in a way that went straight to Mr. Bird's heart, and then prepared peacefully to take his departure.

"I shall not prosecute you for this—" said Mr. Isaac.

"I wish you dare. It would suit me finely to get into a police- court and be able to talk. I'd willingly pay my 'forty shillings and' for the chance. They'd give me the option fast enough."

"I say I shall not prosecute you because I have no time to bother with law. But I shall send your name round amongst the ship- owners, and with my word against you, you'll never get another command so long as the world stands."

"You knock-kneed little Jew," said Kettle truculently, "do you think I'm giving myself the luxury of letting out at a shipowner, after knuckling down to the breed through all of a weary life, unless I knew my ground? I've done with ships and the sea for always, and if you give me any more of your lip, I'll burn your office down and you in it."

"You seem pleased enough with yourself about something," said Mr. Isaac.

"I am," said Kettle exultantly. "I've chucked the sea for good. I've taken a farm in Wharfedale, and I'm going to it this very week."

"Then," said Mr. Isaac sardonically, "if you've taken a farm, don't let me wish you any further ill. Good-morning."

But Kettle was not to be damped out of conceit with his life's desire by a few ill-natured words. He gave Mr. Isaac Bird his final blessing, commenting on his ancestors, his personal appearance, his prospects of final salvation, and then pleasantly took his leave. He was too much occupied in the preliminaries of his new life to have much leisure just then for further cultivation of the gentle art of insult.

The farm he had rented lay in the Wharfe Valley above Skipton, and, though its acreage was large, a good deal was made up of mere moorland sheep pasture. Luckily he recognized that a poetical taste for a rural life might not necessarily imply the whole mystery of stock rearing and agriculture, and so he hired a capable foreman as philosopher and guide. And here I may say that his hobby by no means ruined him, as might reasonably be expected; for in the worst years he never dropped more than fifty or sixty pounds, and frequently he ran the place without loss, or even at a profit.

But though it is hard to confess that a man's ideal comes short of his expectations when put to the trial, I am free to confess that although he enjoyed it all, Kettle was not at his happiest when he was attending his crops or his sheep, or haggling with his fellow farmers on Mondays over fat beasts in Skipton market.

He had gone back to one of his more practiced tastes—if one calls it a taste—the cultivation of religion. The farm stood bleak and lonely on the slope of a hillside, and on both flanks of the dale were other lonely farms as far as the eye could see. There was no village. The nearest place of worship was four miles away, and that was merely a church. But in the valley beside the Wharfe was a small gray stone chapel, reared during some bygone day for the devotions of some forgotten sect. Kettle got this into his control.

He was by no means a rich man. The row of houses in Birkenhead were for the most part tenanted by the wives of mercantile marine engineers and officers, who were chronically laggard with their rent, and whom esprit de corps forbade him to press; and so, what with this deficit, and repairs and taxes, and one thing and another, it was rarely that half the projected £500 a year found its way into his banking account. But a tithe of whatever accrued to him was scrupulously set aside for the maintenance of the chapel.

He imported there the grim, narrow creed he had learned in South Shields, and threw open the door for congregations. He was entirely in earnest over it all, and vastly serious. Failing another minister, he himself took the services, and though, on occasion, some other brother was induced to preach, it was he himself who usually mounted the pulpit beneath the sounding- board. He purchased an American organ, and sent his eldest daughter weekly to take lessons in Skipton till she could play it. And Mrs. Kettle herself led the singing.

Still further, the chapel has its own collection of hymns, specially written, printed and dedicated to its service. The book is Captain Kettle's first published effort. Heaven and its author alone know under what wild circumstances most of those hymns were written.

The chapel started its new span of life with a congregation meagre enough, but Sunday by Sunday the number grew. They are mostly Nonconformists in the dales, and when once a man acquires a taste for dissent, he takes a sad delight in sampling his neighbors' variations of creed. Some came once and were not seen again. Others came and returned. They felt that this was the loneliest of all modern creeds; indeed, Kettle preached as much, and one can take a melancholy pride in splendid isolation.

I am not sure that Captain Kettle does not find the restfulness of his present life a trifle too accentuated at times, though this is only inevitable for one who has been so much a man of action. But at any rate he never makes complaint. He is a strong man, and he governs himself even as he governs his family and the chapel circle, with a strong, just hand. The farm is a model of neatness and order; paint is lavished in a way that makes dalesmen lift their eyebrows; and the routine of the household is as strict as that of a ship.

The house is unique, too, in Wharfedale for the variety of its contents. Desperately poor though Kettle might be on many of his returns from his unsuccessful ventures, he never came back to his wife without some present from a foreign clime as a tangible proof of his remembrance, and because these were usually mere curiosities, without intrinsic value, they often evaded the pawn- shop in those years of dire distress, when more negotiable articles passed irretrievably away from the family possession. And with them too, in stiff, decorous frames, are those certificates and testimonials which a master mariner always collects, together with photographs of gratuitously small general interest.

But one might turn the house upside down without finding so carnal an instrument as a revolver, and when I suggested to Kettle once that we might go outside and have a little pistol practice, he glared at me, and I thought he would have sworn. However, he let me know stiffly enough that whatever circumstances might have made him at sea, he had always been a very different man ashore in England, and there the matter dropped.

But speaking of mementoes, there is one link with the past that Mrs. Kettle, poor woman, never ceases to regret the loss of. "Such a beautiful gold watch," she says it was too, "with the Emperor's and the Captain's names engraved together on the back, and just a nice mention of the Gross of Carl." As it happened, I saw the letter with which it was returned. It ran like this:—

To His Majesty the German Emperor

Berlin, S.S. Flamingo

Germany. Liverpool.

Sir,

I am in receipt of watch sent by your agent, the German ambassador in London, which I return herewith. It is not my custom to accept presents from people I don't know, especially if I have talked about them. I have talked about you, not liking several things you've done, especially telegraphing about Dr. Jameson. Sir, you should remember that man was down when you sent your wire and couldn't hit back. Some of the things I have said about German deck hands you needn't take too much notice about. They aren't so bad as they might be if properly handled. But they want handling. Likewise learning English.

My wife wants to keep your photo, so I send you one of hers in return, so there shall be no robbery. She has written her name over it, same as yours.

Yours truly,

O. Kettle (Master).

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.