RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

A Master of Fortune, 1898,

with "The Dear Insured"

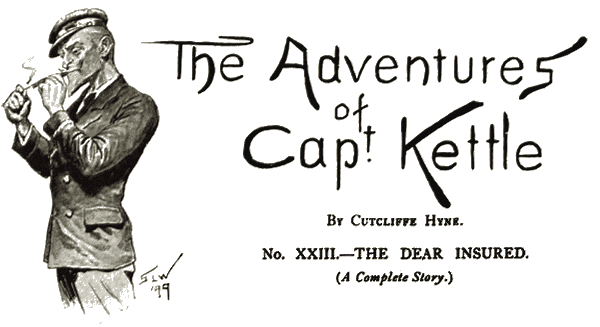

"HE isn't the 'dear deceased' yet by a very long chalk," said Captain Kettle.

"If he was," retorted Lupton with a dry smile, "my immediate interest in him would cease, and the Company would shrug its shoulders, and pay, and look pleasant. In the mean while he's, shall we say, 'the dear insured,' and a premium paying asset that the Company's told me off to keep an eye on."

"Do much business in your particular line?"

"Why yes, recently a good deal. It's got to be quite a fashionable industry of late to pick up some foolish young gentleman with expectations, insure his life for a big pile, knock him quietly on the head, and then come back home in a neat black suit to pocket the proceeds."

"Does this Mr.—" Kettle referred to the passenger list—"Hamilton's the rogue's name, isn't it?"

"No, he's the flat. Cranze is the—Dr—his friend who stands to draw the stamps."

"Does Mr. Hamilton know you?"

"Never seen me in his life."

"Does this thief Cranze?"

"Same."

"Then, sir, I'll tell you what's your ticket," said Kettle, who had got an eye to business. "Take a passage with me out to the Gulf and back, and keep an eye on the young gentleman yourself. You'll find it a bit cold in the Western Ocean at first, but once we get well in the Gulf Stream, and down toward New Orleans, I tell you you'll just enjoy life. It'll be a nice trip for you, and I'm sure I'll do my best to make things comfortable for you."

"I'm sure you would. Captain, but it can't be done at the price."

Kettle looked thoughtfully at the passenger list. "I could promise you a room to yourself. We're not very full up this run. In fact, Mr. Hamilton and Mr. Cranze are the only two names I've got down so far, and I may as well tell you we're not likely to have others. You see Birds are a very good line, but they lay themselves out more for cargo than passengers."

"So our local agent in Liverpool found out for us already, and that's mostly why I'm here. Don't you see, Captain, if the pair of them had started off to go tripping round the Mexican Gulf in one of the regular passenger boats, there would have been nothing suspicious about that. But when they book berths by you, why then it begins to look fishy at once."

Kettle turned on his companion with a sudden viciousness. "By James!" he snapped, "you better take care of your words, or there'll be a man in this smoke-room with a broken jaw. I allow no one to sling slights at either me or my ship. No, nor at the firm either that owns both of us. You needn't look round at the young lady behind the bar. She can't hear what we're saying across in this corner, and if even she could she's quite welcome to know how I think about the matter. By James, do you think you can speak to me as if I was a common railway director? I can tell you that, as Captain of a passenger boat, I've a very different social position."

"By James!" he snapped, "you

better take care of your words.

"My dear sir," said Lupton soothingly, "to insult you was the last thing in my mind. I quite know you've got a fine ship, and a new ship, and a ship to be congratulated on. I've seen her. In fact I was on board and all over her only this morning. But what I meant to point out was (although I seem to have put it clumsily) that Messrs. Bird have chosen to schedule you for the lesser frequented Gulf ports, finding, as you hint, that cargo pays them better than passengers."

"Well?"

"And naturally therefore anything that was done on the Flamingo would not have the same fierce light of publicity on it that would get on—say—one of the Royal Mail boats. You see they bustle about between busy ports crammed with passengers who are just at their wits' end for something to do. You know what a pack of passengers are. Give them a topic like this: Young man with expectations suddenly knocked overboard, nobody knows by whom; 'nother young man on boat drawing a heavy insurance from him; and they aren't long in putting two and two together."

"You seem to think it requires a pretty poor brain to run a steam-packet," said Kettle contemptuously. "How long would I be before I had that joker in irons?"

"If he did it as openly as I have said, you'd arrest him at once. But you must remember Cranze will have been thinking out his game for perhaps a year beforehand, till he can see absolutely no flaw in it, till he thinks, in fact, there's not the vaguest chance of being dropped on. If anything happens to Hamilton, his dear friend Cranze will be the last man to be suspected of it. And mark you, he's a clever chap. It isn't your clumsy, ignorant knave who turns insurance robber—and incidentally murderer."

"Still, I don't see how he'd be better off on my ship than he would be on the bigger passenger packets."

"Just because you won't have a crowd of passengers. Captain, a ship's like a woman; any breath of scandal damages her reputation, whether it's true and deserved or not. And a ship- captain's like a woman's husband; he'll put up with a lot to keep any trace of scandal away from her."

"That's the holy truth."

"A skipper on one of the bigger passenger lines would be just as keen as you could be not to have his ship mixed up with anything discreditable. But passengers are an impious lot. They are just bursting for want of a job, most of them; they revel in anything like an accident to break the monotony; and if they can spot a bit of foul play—or say they helped to spot it—why, there they are, supplied with one good solid never-stale yarn for all the rest of their natural lives. So you see they've every inducement to do a lot of ferreting that a ship's officers (with other work on hand) would not dream about."

Captain Kettle pulled thoughtfully at his neat red pointed beard. "You're putting the thing in a new light, sir, and I thank you for what you've said. I see my course plain before me. So soon as we have dropped the pilot, I shall go straight to this Mr. Cranze, and tell him that from information received I hear he's going to put Mr. Hamilton over the side. And then I shall say: 'Into irons you go, my man, so soon as ever Hamilton's missing.'"

Lupton laughed rather angrily. "And what would be the result of that, do you think?"

"Cranze will get mad. He'll probably talk a good deal, and that I shall allow within limits. But he'll not hit me. I'm not the kind of a man that other people see fit to raise their hands to."

"You don't look it. But, my good sir, don't you see that if you speak out like that, you'll probably scare the beggar off his game altogether?"

"And why not? Do you think my ship's a blessed detective novel that's to be run just for your amusement?"

Lupton tapped the table slowly with his fingers. "Now look here. Captain," he said, "there's a chance here of our putting a stop to a murderous game that's been going on too long, by catching a rogue red-handed. It's to our interest to get a conviction and make an example. It's to your interest to keep your ship free from a fuss."

"All the way."

"Quite so. My Company's prepared to buy your interest up."

"You must put it plainer than that."

"I'll put it as definitely as you like. I'll give you £20 to keep your eye on these men, and say nothing about what I've told you, but just watch. If you catch Cranze so clearly trying it on that the Courts give a conviction, the Company will pay you £200."

"It's a lot of money."

"My Company will find it a lot cheaper than paying out £20,000, and that's what Hamilton's insured for."

"Phew! I didn't know we were dealing with such big figures. Well, Mr. Cranze has got his inducements to murder the man, anyway."

"I told you that from the first. Now, Captain, are you going to take my check for that preliminary £20?"

"Hand it over," said Kettle. "I see no objections. And you may as well give me a bit of a letter about the balance."

"I'll do both," said Lupton, and took out his stylograph, and called a waiter to bring him hotel writing paper.

Now Captain Owen Kettle, once he had taken up this piece of employment, entered into it with a kind of chastened joy. The Life Insurance Company's agent had rather sneered at ship- captains as a class (so he considered), and though the man did his best to be outwardly civil, it was plain that he considered a mob of passengers the intellectual superiors of any master mariner. So Kettle intended to prove himself the "complete detective" out of sheer esprit de corps.

As he had surmised, Messrs. Hamilton and Cranze remained the Flamingo's only two passengers, and so he considered he might devote full attention to them without being remarkable. If he had been a steward making sure of his tips he could not have been more solicitous for their welfare; and to say he watched them like a cat is putting the thing feebly. Any man with an uneasy conscience must have grasped from the very first that the plot had been guessed at, and that this awkward little skipper, with his oppressive civilities, was merely waiting his chance to act as Nemesis.

But either Mr. Cranze had an easy mind, and Lupton had unjustly maligned him, or he was a fellow of the most brazen assurance. He refused to take the least vestige of a warning. He came on board with a dozen cases of champagne and four of liqueur brandy as a part of his personal luggage, and his first question to every official he came across was how much he would have to pay per bottle for corkage.

As he made these inquiries from a donkey-man, two deck hands, three mates, a trimmer, the third engineer, two stewards, and Captain Kettle himself, the answers he received were various, and some of them were profane. He seemed to take a delight in advertising his chronic drunkenness, and between-whiles he made a silly show of the fact that he carried a loaded revolver in his hip pocket. "Lots fellows do't now," he explained. "Never know who-you-may-meet. S' a mos' useful habit."

Now Captain Kettle, in his inmost heart, considered that Cranze was nerving himself up with drink to the committal of his horrid deed, and so he took a very natural precaution. Before they had dropped the Irish coast he had managed to borrow the revolver, unbeknown to its owner, and carefully extracted the powder from the cartridges, replacing the bullets for the sake of appearances. And as it happened, the chief engineer, who was a married man as well as a humorist, though working independently of his skipper, carried the matter still further. He, too, got hold of the weapon, and brazed up the breech-block immovably, so that it could not be surreptitiously reloaded. He said that his wife had instructed him to take no chances, and that meanwhile, as a fool's pendant, the revolver was as good as ever it had been.

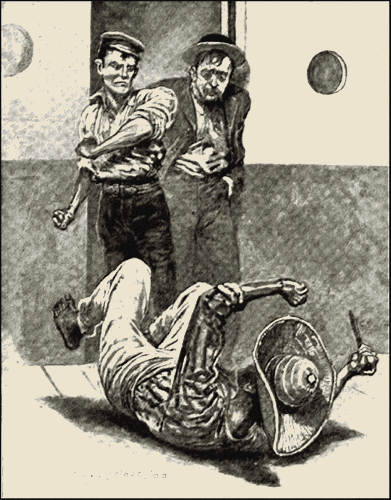

The revolver became the joke of the ship. Cranze kept up a steady soak on king's peg—putting in a good three fingers of the liqueur brandy before filling up the tumbler with champagne—and was naturally inclined to be argumentative. Any one of the ship's company who happened to be near him with a little time to spare would get up a discussion on any matter that came to his mind, work things gently to a climax, and then contradict Cranze flatly. Upon which, out would come the revolver, and down would go the humorist on his knees, pitifully begging for pardon and life, to the vast amusement of the onlookers.

Down would go the humorist on his knees,

pitifully begging for pardon and life.

Pratt, the chief engineer, was the inventor of this game, but he openly renounced all patent rights. He said that everybody on board ought to take the stage in turn—he himself was quite content to retire on his early laurels. So all hands took pains to contradict Cranze and to cower with a fine show of dramatic fright before his spiked revolver.

All the Flamingo's company except one man, that is. Frivolity of this sort in no way suited the appetite of Captain Owen Kettle. He talked with Cranze with a certain dry cordiality. And at times he contradicted him. In fact the little sailor contradicted most passengers if he talked to them for long. He was a man with strong opinions, and he regarded tolerance as mere weakness. Moreover, Cranze's chronic soaking nauseated him. But at the same time, if his civility was scant, Cranze never lugged out the foolish weapon in his presence. There was a something in the shipmaster's eye which daunted him. The utmost height to which his resentment could reach with Captain Kettle was a folding of the arms and a scowl which was intended to be majestic, but which was frequently spoiled by a hiccough.

In pleasant contrast to this weak, contemptible knave was the man Hamilton, his dupe and prospective victim. For him Kettle formed a liking at once, though for the first days of the voyage it was little enough he saw of his actual presence. Hamilton was a bad sailor and a lover of warmth, and as the Western Ocean was just then in one of its cold and noisy moods, this passenger went shudderingly out of the cabin when meals came on, and returned shudderingly from the cold on deck as soon they were over.

But when the Flamingo began to make her southing, and the yellow tangles of weed floating in emerald waves bore evidence that they were steaming against the warm current of the Gulf Stream, then Hamilton came into view. He found a spot on the top of the fiddley under the lee of a tank where a chair could stand, and sat there in the glow of sun and boilers, and basked complacently.

He was a shy, nervous little man, and though Kettle had usually a fine contempt for all weakness, somehow his heart went out to this retiring passenger almost at first sight. Myself, I am inclined to think it was because he knew him to be hunted, knew him to be the object of a murderous conspiracy, and loathed most thoroughly the vulgar rogue who was his treacherous enemy. But Captain Kettle scouts the idea that he was stirred by any such feeble, womanish motives. Kettle was a poet himself, and with the kinship of species he felt the poetic fire glowing out from the person of this Mr. Hamilton. At least, so he says; and if he has deceived himself on the matter, which, from an outsider's point of view, seems likely, I am sure the error is quite unconscious. The little sailor may have his faults, as the index of these pages has shown; but untruthfulness has never been set down to his tally, and I am not going to accuse him of it now.

Still, it is a sure thing that talk on the subject of verse making did not come at once. Kettle was immensely sensitive about his accomplishment, and had writhed under brutal scoffs and polished ridicule at his poetry more times than he cared to count. With passengers especially he kept it scrupulously in the background, even as he did his talent for making sweet music on the accordion.

But somehow he and Hamilton, after a few days' acquaintance, seemed to glide into the subject imperceptibly. Mutual confidences followed in the course of nature. It seemed that Hamilton too, like Kettle, was a devotee of the stiller forms of verse.

"You see, Skipper," he said, "I've been a pretty bad lot, and I've made things hum most of my time, and so I suppose I get my hankerings after restfulness as the natural result of contrast."

"Same here, sir. Ashore I can respect myself, and in our chapel circle, though I say it myself, you'll find few more respected men. But at sea I shouldn't like to tell you what I've done; I shouldn't like to tell any one. If a saint has to come down and skipper the brutes we have to ship as sailormen nowadays, he'd wear out his halo flinging it at them. And when matters have been worst, and I've been bashing the hands about, or doing things to carry out an owner's order that I'd blush even to think of ashore, why then, sir, gentle verse, to tunes I know, seems to bubble up inside me like springs in a barren land."

"Well, I don't know about that," said Hamilton doubtfully, "but when I get thoroughly sick of myself, and wish I was dead, I sometimes stave off putting a shot through my silly head by getting a pencil and paper, and shifting my thoughts out of the beastly world I know, into—well, it's hard to explain. But I get sort of notions, don't you see, and they seem to run best in verse. I write 'em when the fit's on me, and I burn 'em when the fit's through; and you'll hardly think it, but I never told a living soul I ever did such a thing till I told you this minute. My set—I mean, I couldn't bear to be laughed at. But you seem to be a fellow that's been in much the same sort of box yourself."

"I don't know quite that. At any rate, I've never thought of shooting myself."

"Oh, I didn't mean to suggest we were alike at all in detail. I was only thinking we had both seen rough times. Lord forbid that any man should ever be half the fool that I have been." He sighed heavily.—"However, sufficient for the day. Look out over yonder; there's a bit of color for you."

A shoal of flying-fish got up out of the warm, shining water and ran away over the ripples like so many silver rats; yellow tangles of Gulf-weed swam in close squadron on the emerald sea; and on the western horizon screw-pile lighthouses stood up out of the water, marking the nearness of the low-lying Floridan beaches, and reminding one of mysterious Everglades beyond.

"A man, they tell me," said Hamilton, "can go into that country at the back there, and be a hermit, and live honestly on his own fish and fruit. I believe I'd like that life. I could go there, and be decent, and perhaps in time I should forget things."

"Don't you try it. The mosquitoes are shocking."

"There are worse devils than mosquitoes. Now I should have thought there was something about those Everglades that would have appealed to you, Skipper?"

"There isn't, and I've been there. You want a shot-gun in Florida to shoot callers with, not eatables. I've written verse there, and good verse, but it was the same old tale, sir, that brought it up to my fingers' ends. I'd been having trouble just then—yes, bad trouble. No, Mr. Hamilton, you go home, sir, to England and find a country place, and get on a farm, and watch the corn growing, and hear the birds sing, and get hold of the smells of the fields, and the colors of the trees, and then you'll enjoy life and turn out poetry you can be proud of."

"Doesn't appeal to me. You see you look upon the country with a countryman's eye."

"Me," said Kettle. "I'm seaport and sea bred and brought up, and all I know of fields and a farm is what I've seen from a railway- carriage window. No, I've had to work too hard for my living, and for a living for Mrs. Kettle and the youngsters, to have any time for that sort of enjoyment; but a man can't help knowing what he wants, sir, can he? And that's what I'm aiming at, and it's for that I'm scratching together every sixpence of money I can lay hands on."

But here a sudden outcry below broke in upon their talk. "That's Mr. Cranze," said Kettle. "He'll be going too far in one of his tantrums one of these days."

"I'm piously hoping the drunken brute will tumble overboard," Hamilton muttered; "it would save a lot of trouble for everybody. Eh, well," he said, "I suppose I'd better go and look after him," and got up and went below.

Captain Kettle sat where he was, musing. He had no fear that Cranze, the ship's butt and drunkard, would murder his man in broad, staring daylight, especially as, judging from the sounds, others of the ship's company were at present baiting him. But he did not see his way to earning that extra £200, which he would very much like to have fingered. To let this vulgar, drunken ruffian commit some overt act against Hamilton's life, without doing him actual damage, seemed an impossibility. He had taken far to great a fancy for Hamilton to allow him to be hurt. He was beginning to be mystified by the whole thing. The case was by no means so simple and straightforward as it had looked when Lupton put it to him in the hotel smoking-room ashore.

Had Cranze been any other passenger, he would have stopped his drunken riotings by taking away the drink, and by giving strict orders that the man was to be supplied with no further intoxicants. But Cranze sober might be dangerous, while Cranze tipsy was merely a figure of ridicule; so he submitted, very much against his grain, to having his ship made into a bear-garden, and anxiously awaited developments.

The Flamingo cleared the south of Florida, sighted the high land of Cuba, and stood across through the Yucatan channel to commence her peddling business in Honduras, and at some twenty ports she came to an anchor six miles off shore, and hooted with her siren till lighters came off through the surf and the shallows.

Machinery they sent ashore at these little-known stations, coal, powder, dress-goods, and pianos, receiving in return a varied assortment of hides, mahogany, dyewoods, and some parcels of ore. There was a small ferrying business done also between neighboring ports in unclean native passengers, who harbored on the foredeck, and complained of want of deference from the crew.

Hamilton appeared to extract some melancholy pleasure from it all, and Cranze remained unvaryingly drunk. Cranze passed insults to casual strangers who came on board and did not know his little ways, and the casual strangers (after the custom of their happy country) tried to knife him, but were always knocked over in the nick of time, by some member of the Flamingo's crew. Hamilton said there was a special providence which looks after drunkards of Cranze's type, and declined to interfere; and Cranze said he refused to be chided by a qualified teetotaller, and mixed himself further king's pegs.

The casual strangers tried to knife him, but

were always knocked over in the nick of time.

Messrs. Bird, Bird and Co., being of an economical turn of mind, did not fall into the error of overmanning their ships, and so as one of the mates chose to be knocked over by six months' old malarial fever, Captain Kettle had practically to do a mate's duty as well as his own. A mate in the mercantile marine is officially an officer and some fraction of a gentleman, but on tramp steamers and liners where cargo is of more account than passengers—even when they dine at half-past six, instead of at midday—a mate has to perform manual labors rather harder than that accomplished by any three regular deck hands.

I do not intend to imply that Kettle actually drove a winch, or acted as stevedore below, or sweated over bales as they swung up through a hatch, but he did work as gangway man, and serve at the tally desk, and oversee generally while the crew worked cargo; and his watch over the passengers was at this period of necessity relaxed. He tried hard to interest Hamilton in the mysteries of hold stowage, in order to keep him under his immediate eye. But Hamilton bluntly confessed to loathing anything that was at all useful, and so he perforce had to be left to pick his own position under the awnings, there to doze, and smoke cigarettes, and scribble on paper as the moods so seized him.

It was off one of the ports in the peninsula of Yucatan, toward the Bay of Campeachy, that Cranze chose to fall overboard. The name of the place was announced by some one when they brought up, and Cranze asked where it was. Kettle marked it off with a leg of the dividers on the chart. "Yucatan," said Cranze, "that's the ruined cities shop, isn't it?"—He shaded his unsteady eyes, and looked out at a clump of squalid huts just showing on the beach beyond some three miles of tumbling surf. "Gum! here's a ruined city all hot and waiting. Home of the ancient Aztecs, and colony of the Atlanteans, and all that. Skipper, I shall go ashore, and enlarge my mind."

"You can go if you like," said Kettle, "but remember, I steam away from here as soon as ever I get the cargo out of her, and I wait for no man. And mind not to get us upset in the surf going there. The water round here swarms with sharks, and I shouldn't like any of them to get indigestion."

"Seem trying to make yourself jolly ob-bub-jectable's morning," grumbled Cranze, and invited Hamilton to accompany him on shore forthwith. "Let's go and see the girls. Ruined cities should have ruined girls and ruined pubs to give us some ruined amusement. We been on this steamer too long, an' we want variety. V'riety's charming. Come along and see ruined v'riety."

Hamilton shrugged his shoulders. "Drunk as usual, are you? You silly owl, whatever ruined cities there may be, are a good fifty miles in the bush."

"'S all you know about it. I can see handsome majestic ruin over there on the beach, an' I'm going to see it 'out further delay. 'S a duty I owe to myself to enlarge the mind by studying the great monuments of the past."

"If you go ashore, you'll be marooned as safe as houses, and Lord knows when the next steamer will call. The place reeks of fever, and as your present state of health is distinctly rocky, you'll catch it, and be dead and out of the way inside a week easily. Look here, don't be an ass."

"Look here yourself. Are you a competent medicated practitioner?"

"Oh, go and get sober."

"Answer me. Are you competent medicated practitioner?"

"No, I'm not."

"Very well then. Don't you presume t'lecture me on state of my health. No reply, please. I don' wan' to be encumbered with your further acquaintance. I wish you a go' morning."

Hamilton looked at Captain Kettle under his brows. "Will you advise me," he said, "what I ought to do."

"I should say it would be healthier for you to let him have his own way."

"Thanks," said Hamilton, and turned away. "I'll act on that advice."

Now the next few movements of Mr. Cranze are wrapped in a certain degree of mystery. He worried a very busy third mate, and got tripped on the hard deck for his pains; he was ejected forcibly from the engineers' mess-room, where it was supposed he had designs on the whisky; and he was rescued by the carpenter from an irate half-breed Mosquito Indian, who seemed to have reasons for desiring his blood there and then on the spot. But how else he passed the time, and as to how he got over the side and into the water, there is no evidence to show.

There were theories that he had been put there by violence as a just act of retribution; there was an idea that he was trying to get into a lighter which lay alongside for a cast ashore, but saw two lighters, and got into the one which didn't exist; and there were other theories also, but they were mostly frivolous. But the very undoubted fact remained that he was there in the water, that there was an ugly sea running, that he couldn't swim, and that the place bristled with sharks.

A couple of life-buoys, one after the other, hit him accurately on the head, and the lighter cast off, and backed down to try and pick him up. He did not bring his head on to the surface again, but stuck up an occasional hand, and grasped with it frantically. And, meanwhile, there was great industry among the black triangular dorsal fins that advertised the movements of the sharks which owned them underneath the surface. Nobody on board the Flamingo had any particular love for Cranze, but all hands crowded to the rail and shivered and felt sick at the thought of seeing him gobbled up.

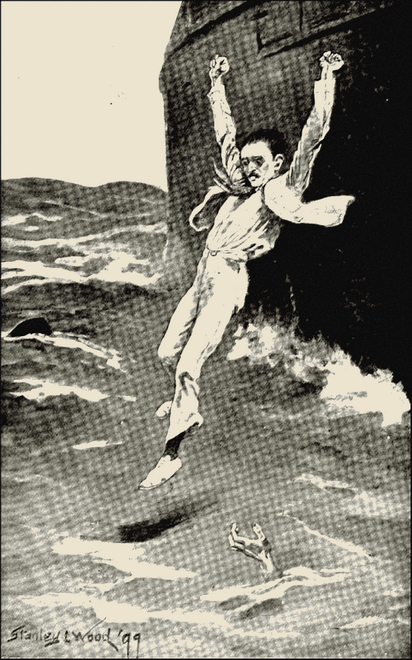

Then out of the middle of these spectators jumped the mild, delicate Hamilton, with a volley of bad language at his own foolishness, and lit on a nice sleek wave-crest, feet first in an explosion of spray. Away scurried the converging sharks' fins, and down shot Hamilton out of sight.

Then out jumped the mild, delicate Hamilton.

What followed came quickly. Kettle, with a tremendous flying leap, landed somehow on the deck of the lighter, with bones unbroken. He cast a bowline on to the end of the main sheet, and, watching his chance, hove the bight of it cleverly into Hamilton's grasp, and as Hamilton had come up with Cranze frenziedly clutching him round the neck, Kettle was able to draw his catch toward the lighter's side without further delay.

By this time the men who had gone below for that purpose had returned with a good supply of coal, and a heavy fusillade of the black lumps kept the sharks at a distance, at any rate for the moment. Kettle heaved in smartly, and eager hands gripped the pair as they swirled up alongside, and there they were on the lighter's deck, spitting, dripping, and gasping. But here came an unexpected development. As soon as he had got back his wind, the mild Hamilton turned on his fellow passenger like a very fury, hitting, kicking, swearing, and almost gnashing with his teeth; and Cranze, stricken to a sudden soberness by his ducking, collected himself after the first surprise, and returned the blows with a murderous interest.

But one of the mates, who had followed his captain down on to the lighter to bear a hand, took a quick method of stopping the scuffle. He picked up a cargo-sling, slipped it round Cranze's waist, hooked on the winch chain, and passed the word to the deck above. Somebody alive to the jest turned on steam, and of a sudden Cranze was plucked aloft, and hung there under the derrick-sheave, struggling impotently, like some insane jumping- jack.

Amid the yells of laughter which followed, Hamilton laughed also, but rather hysterically. Kettle put a hand kindly on his wet shoulder. "Come on board again," he said. "If you lie down in your room for an hour or so, you'll be all right again then. You're a bit over-done. I shouldn't like you to make a fool of yourself."

"Make a fool of myself," was the bitter reply. "I've made a bigger fool of myself in the last three minutes than any other man could manage in a lifetime."

"I'll get you the Royal Humane Society's medal for that bit of a job, anyway."

"Give me a nice rope to hang myself with," said Hamilton ungraciously, "that would be more to the point. Here, for the Lord's sake let me be, or I shall go mad." He brushed aside all help, clambered up the steamer's high black side again, and went down to his room.

"That's the worst of these poetic natures," Kettle mused as he, too, got out of the lighter; "they're so highly strung."

Cranze, on being lowered down to deck again, and finding his tormentors too many to be retaliated upon, went below and changed, and then came up again and found solace in more king's pegs. He was not specially thankful to Hamilton for saving his life; said, in fact, that it was his plain duty to render such trifling assistance; and further stated that if Hamilton found his way over the side, he, Cranze, would not stir a finger to pull him back again.

He was very much annoyed at what he termed Hamilton's "unwarrantable attack," and still further annoyed at his journey up to the derrick's sheave in the cargo-sling, which he also laid to Hamilton's door. When any of the ship's company had a minute or so to spare, they came and gave Cranze good advice and spoke to him of his own unlovableness, and Cranze hurled brimstone back at them unceasingly, for king's peg in quantity always helped his vocabulary of swear-words.

Meanwhile the Flamingo steamed up and dropped cargo wherever it was consigned, and she abased herself to gather fresh cargo wherever any cargo offered. It was Captain Kettle who did the abasing, and he did not like the job at all; but he remembered that Birds paid him specifically for this among other things; and also that if he did not secure the cargo, some one else would steam along, and eat dirt, and snap it up; and so he pocketed his pride (and his commission) and did his duty. He called to mind that he was not the only man in the world who earned a living out of uncongenial employment. The creed of the South Shields chapel made a point of this: it preached that to every man, according to his strength, is the cross dealt out which he has to bear. And Captain Owen Kettle could not help being conscious of his own vast lustiness.

But one morning, before the Flamingo had finished with her calls on the ports of the Texan rivers, a matter happened on board of her which stirred the pulse of her being to a very different gait. The steward who brought Captain Kettle's early coffee coughed, and evidently wanted an invitation to speak.

"Well?' said Kettle.

"It's about Mr. Hamilton, sir. I can't find 'im anywheres."

"Have you searched the ship?"

"Hunofficially, sir."

"Well, get the other two stewards, and do it thoroughly."

The steward went out, and Captain Kettle lifted the coffee cup and drank a salutation to the dead. From that very moment he had a certain foreboding that the worst had happened. "Here's luck, my lad, wherever you now may be. That brute Cranze has got to windward of the pair of us, and your insurance money's due this minute. I only sent that steward to search the ship for form's sake. There was the link of poetry between you and me, lad; and that's closer than most people could guess at; and I know, as sure as if your ghost stood here to tell me, that you've gone. How, I've got to find out."

He put down the cup, and went to the bathroom for his morning's tub. "I'm to blame, I know," he mused on, "for not taking better care of you, and I'm not trying to excuse myself. You were so brimful of poetry that you hadn't room left for any thought of your own skin, like a chap such as I am is bound to have. Besides, you've been well-off all your time and you haven't learned to be suspicious. Well, what's done's done, and it can't be helped. But, my lad, I want you to look on while I hand in the bill. It'll do you good to see Cranze pay up the account."

Kettle went through his careful toilet, and then in his spruce white drill went out and walked briskly up and down the hurricane deck till the steward came with the report. His forebodings had not led him astray. Hamilton was not on board: the certain alternative was that he lay somewhere in the warm Gulf water astern, as a helpless dead body.

"Tell the Chief Officer," he said, "to get a pair of irons out of store and bring them down to Mr. Cranze's room. I'm going there now."

He found Cranze doctoring a very painful head with the early application of stimulant, and Cranze asked him what the devil he meant by not knocking at the door before opening it.

Captain Kettle whipped the tumbler out of the passenger's shaking fingers, and emptied its contents into the wash-basin.

"I'm going to see you hanged shortly, you drunken beast," he said, "but in the mean while you may as well get sober for a change, and explain things up a bit."

Cranze swung his legs out of the bunk and sat up. He was feeling very tottery, and the painfulness of his head did not improve his temper. "Look here," he said, "I've had enough of your airs and graces. I've paid for my passage on this rubbishy old water- pusher of yours, and I'll trouble you to keep a civil tongue in your head, or I'll report you to your owners. You are like a railway guard, my man. After you have seen that your passengers have got their proper tickets, it's your duty to—"

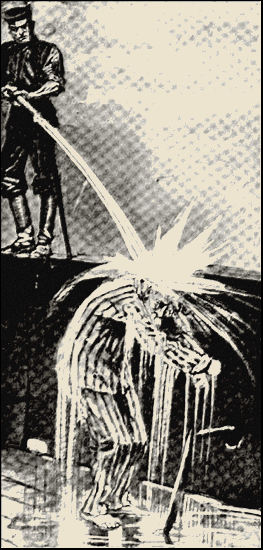

Mr. Cranze's connective remarks broke off here for the time being. He found himself suddenly plucked away from the bunk by a pair of iron hands, and hustled out through the state-room door. He was a tall man, and the hands thrust him from below, upward, and, though he struggled wildly and madly, all his efforts to have his own way were futile. Captain Owen Kettle had handled far too many really strong men in this fashion to even lose breath over a dram-drinking passenger. So Cranze found himself hurtled out on to the lower fore-deck, where somebody handcuffed him neatly to an iron stanchion, and presently a mariner, by Captain Kettle's orders, rigged a hose, and mounted on the iron bulwark above him, and let a three-inch stream of chilly brine slop steadily on to his head.

The situation, from an onlooker's point of view, was probably ludicrous enough, but what daunted the patient was that nobody seemed to take it as a joke. There were a dozen men of the crew who had drawn near to watch, and yesterday all these would have laughed contemptuously at each of his contortions. But now they are all stricken to a sudden solemnity.

"Spell-o," ordered Kettle. "Let's see if he's sober yet."

The man on the bulwarks let the stream from the hose flop overboard, where it ran out into a stream of bubbles which joined the wake.

Cranze gasped back his breath, and used it in a torrent of curses.

"Play on him again," said Kettle, and selected a good black before-breakfast cigar from his pocket. He lit it with care. The man on the bulwark shifted his shoulder for a better hold against the derrick-guy, and swung the limp hose in-board again. The water splashed down heavily on Cranze's head and shoulders, and the onlookers took stock of him without a trace of emotion. They had most of them seen the remedy applied to inebriates before, and so they watched Cranze make his gradual recovery with the eyes of experts.

The water splashed down heavily

on Cranze's head and shoulders.

"Spell-o," ordered Kettle some five minutes later, and once more the hose vomited sea water ungracefully into the sea. This time Cranze had the sense to hold his tongue till he was spoken to. He was very white about the face, except for his nose, which was red, and his eye had brightened up considerably. He was quite sober, and quite able to weigh any words that were dealt out to him.

"Now," said Kettle judicially, "what have you done with Mr. Hamilton?"

"Nothing."

"You deny all knowledge of how he got overboard?"

Cranze was visibly startled. "Of course I do. Is he overboard?"

"He can't be found on this ship. Therefore he is over the side. Therefore you put him there."

Cranze was still more startled. But he kept himself in hand. "Look here," he said, "what rot! What should I know about the fellow? I haven't seen him since last night."

"So you say. But I don't see why I should believe you. In fact, I don't."

"Well, you can suit yourself about that, but it's true enough. Why in the name of mischief should I want to meddle with the poor beggar? If you're thinking of the bit of a scrap we had yesterday, I'll own I was full at the time. And so must he have been. At least I don't know why else he should have set upon me like he did. At any rate that's not a thing a man would want to murder him for."

"No, I should say £20,000 is more in your line."

"What are you driving at?"

"You know quite well. You got that poor fellow insured just before this trip, you got him to make a will in your favor, and now you've committed a dirty, clumsy murder just to finger the dollars."

Cranze broke into uncanny hysterical laughter. "That chap insured; that chap make a will in my favor? Why, he hadn't a penny. It was me that paid for his passage. I'd been on the tear a bit, and the Jew fellow I went to about raising the wind did say something about insuring, I know, and made me sign a lot of law papers. They made out I was in such a chippy state of health that they'd not let me have any more money unless I came on some beastly dull sea voyage to recruit a bit, and one of the conditions was that one of the boys was to come along too and look after me."

"You'll look pretty foolish when you tell that thin tale to a jury."

"Then let me put something else on to the back of it. I'm not Cranze at all. I'm Hamilton. I've been in the papers a good deal just recently, because I'd been flinging my money around, and I didn't want to get stared at on board here. So Cranze and I swapped names, just to confuse people. It seems to have worked very well."

"Yes," said Kettle, "it's worked so well that I don't think you'll get a jury to believe that either. As you don't seem inclined to make a clean breast of it, you can now retire to your room, and be restored to your personal comforts. I can't hand you over to the police without inconvenience to myself till we get to New Orleans, so I shall keep you in irons till we reach there. Steward—where's a steward? Ah, here you are. See this man is kept in his room, and see he has no more liquor. I make you responsible for him."

"Yes, sir," said the steward.

Continuously the dividends of Bird, Bird and Co. outweighed every other consideration, and the Flamingo dodged on with her halting voyage. At the first place he put in at, Kettle sent off an extravagant cablegram of recent happenings to the representative of the Insurance Company in England. It was not the cotton season, and the Texan ports yielded the steamer little, but she had a ton or so of cargo for almost every one of them, and she delivered it with neatness, and clamored for cargo in return. She was "working up a connection." She swung round the Gulf till she came to where logs borne by the Mississippi stick out from the white sand, and she wasted a little time, and steamed past the nearest outlet of the delta, because Captain Kettle did not personally know its pilotage. He was getting a very safe and cautious navigator in these latter days of his prosperity.

So she made for the Port Eads pass, picked up a pilot from the station by the lighthouse, and steamed cautiously up to the quarantine station, dodging the sandbars. Her one remaining passenger had passed from an active nuisance to a close and unheard prisoner, and his presence was almost forgotten by every one on board, except Kettle and the steward who looked after him. The merchant seaman of these latter days has to pay such a strict attention to business, that he has no time whatever for extraneous musings.

The Flamingo got a clean bill from the doctor at the quarantine station, and emerged triumphantly from the cluster of craft doing penance, and, with a fresh pilot, steamed on up the yellow river, past the white sugar-mills, and the heavy cypresses behind the banks. And in due time the pilot brought her up to New Orleans, and, with his glasses on the bridge, Kettle saw his acquaintance, Mr. Lupton, waiting for him on the levee.

He got his steamer berthed in the crowded tier, and Mr. Lupton pushed on board over the first gang-plank. But Kettle waved the man aside till he saw his vessel finally moored. And then he took him into the chart-house and shut the door.

"You seem to have got my cable," he said. "It was a very expensive one, but I thought the occasion needed it."

His visitor tapped Kettle confidentially on the knee. "You'll find my office will deal most liberally with you, Captain. But I can tell you I'm pretty excited to hear your full yarn."

"I'm afraid you won't like it," said Kettle. "The man's obviously dead, and, fancy it or not, I don't see how your office can avoid paying the full amount. However, here's the way I've logged it down"—and he went off into detailed narration.

The New Orleans heat smote upon the chart-house roof, and the air outside clattered with the talk of negroes. Already hatches were off, and the winch chains sang as they struck out cargo, and from the levee alongside, and from New Orleans below and beyond, came tangles of smells which are peculiarly their own. A steward brought in tea, and it stood on the chart-table untasted, and at last Kettle finished, and Lupton put a question.

"It's easy to tell," he said, "if they did swap names. What was the man that went overboard like?"

"Little dark fellow, short sighted. He was a poet, too."

"That's not Hamilton, anyway, but it might be Cranze. Is your prisoner tall?"

"Tall and puffy. Red-haired and a spotty face."

"That's Hamilton, all the way. By Jove! Skipper, we've saved our bacon. His yarn's quite true. They did change names. Hamilton's a rich young ass that's been painting England red these last three years."

"But, tell me, what did the little chap go overboard for?"

"Got there himself. Uneasy conscience, I suppose. He seems to have been a poor sort of assassin anyway. Why, when that drunken fool tumbled overboard amongst the sharks, he didn't leave him to be eaten or drowned, is more than I can understand. He'd have got his money as easy as picking it up off the floor, if he'd only had the sense to keep quiet."

"If you ask me," said Kettle, "it was sheer nobility of character. I had a good deal of talk with that young gentleman, sir. He was a splendid fellow. He had a true poetical soul."

Mr. Lupton winked sceptically. "He managed to play the part of a thorough-paced young blackguard at home pretty successfully. He was warned off the turf. He was kicked out of his club for card- sharping. He was—well, he's dead now, anyway, and we won't say any more about him, except that he's been stone-broke these last three years, and has been living on his wits and helping to fleece other flats. But he was only the tool, anyway. There is a bigger and more capable scoundrel at the back of it all, and, thanks to the scare you seem to have rubbed into that spotty- faced young mug you've got locked up down below, I think we can get the principal by the heels very nicely this journey. If you don't mind, I'll go and see this latest victim now, before he's had time to get rid of his fright."

Captain Kettle showed his visitor courteously down to the temporary jail, and then returned to the chart-house and sipped his tea.

"His name may really have been Cranze, but he was a poet, poor lad," he mused, thinking of the dead. "That's why he couldn't do the dirty work. But I sha'n't tell Lupton that reason. He'd only laugh—and—that poetry ought to be a bit of a secret between the lad and me. Poor, poor fellow! I think I'll be able to write a few lines about him myself after I've been ashore to see the agent, just as a bit of an epitaph. As to this spotty- faced waster who swapped names with him, I almost have it in me to wish we'd left him to be chopped by those sharks. He'd his money to his credit anyway—and what's money compared with poetry?"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.