RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

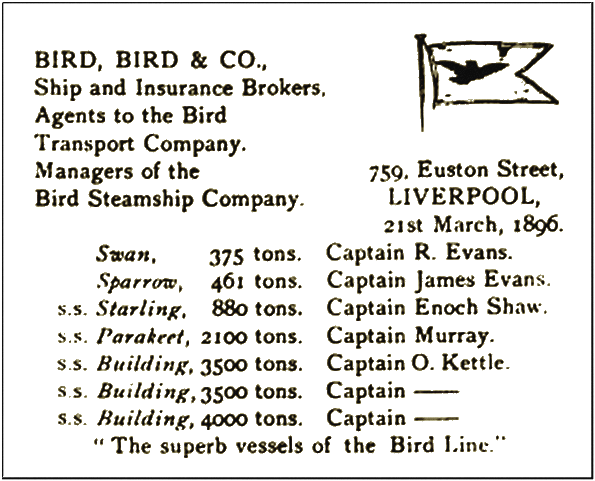

A Master of Fortune, 1898,

with "Dago Divers"

"I'M real glad to be able to call you 'Captain,' my lad," said Kettle, and Murray, in delight at his new promotion, wrung his old commander's hand again. "You've slaved hard enough as mate," Kettle went on, "though that's only what a man's got to do at sea nowadays if he wants promotion, and it'll probably amuse you to see Grain, who steps into your shoes, doing the work of four deck hands and an extra boatswain as well as his own. Grain was inclined to stoutness—he'll soon be thin again. As for you, you've sweated and slaved so much that your clothes hang on like you a slop-chest shirt on a stanchion just now. But you'll fill 'em out nicely by the time you get back to England again. Shouldn't wonder but what you turn out to be a regular fat man one of these days, my lad."

Murray stood back and looked humorously over Captain Kettle. The pair of them liked one another well, but the ties of discipline had kept them icily apart up to now. Murray's promotion put them on equal footing of grade now, and they were inclined to make the most of it for the short time they had together. "Running the Parakeet doesn't seem to have made you very plump. Skipper."

"Constitutional, I guess," said Kettle. "I don't believe the food's grown that'd make me carry flesh. I'm one of those men that was sent into the world with a whole shipload of bad luck to work through before I came across any of the soft things."

"If you ask me," said Murray, cheerfully, "you haven't much to grumble at now. Here am I kicking you out of the command of the Parakeet to be sure. And why? Because whilst you've been her old man you've made her pay about half what she originally cost per annum, and as out of that the firm's saved enough to build a new and bigger ship, they're naturally going to give her to you to scare up more fat dividends. Lord," said Murray, hitting his knee, "the chaps on board here will be calling me the 'old man' behind my back now."

"You'll get used to hearing the title," said Kettle grimly, "before you make your pile. You'll get married, I suppose, on the strength of the promotion? I saw a girl's photo nailed up in your room."

The new captain nodded. "Got engaged when I passed for my master's ticket. Arranged to be hitched so soon as I found a ship."

Kettle sighed drearily. "I was that way, my lad. I was married, and a kid had come before I was thirty. Not that I ever regretted it; by James! no. But for long enough I was never able to provide for the missus in the way I'd like, and I can tell you it was terrible gall to me to know that our set at the chapel looked down on her because she could only keep a poor home. Yes, my lad, you'll have a lot to go through."

"Well," said Murray, "I've got this promotion, and I'm not going to worry about dismals. I suppose you go straight home by mail from Aden here?"

"Hullo, haven't they told you?"

"My letter was only the dry, formal announcement that you were promoted to the new ship, and I was to take over the Parakeet."

"They don't waste their typewriter in the office. I suppose they thought I'd hand on my letter if I saw fit. Read through that," said Kettle, and handed across his news. This is how it ran: —

Dear Captain Kettle—

Having noted from your cables and reports you are making a good thing for us out of tramping the "Parakeet," we have pleasure in transferring you to our new boat, which is now building on the Clyde. She will be 3,500 tons, and we may take out passenger certificate, she being constructed on that specification. Your pay will be £21 (twenty-one pound) per month, with 2 1/2 per cent, commission as before. But for the present, till this new boat is finished, we want you to give over command of the "Parakeet" to Murray, and take on a new job. Our Mr. Alexander Bird has recently bought the wreck of the S.S. "Grecian," and we are sending out a steamer with divers and full equipment to get the salvage. We wish you to go on board this vessel to watch over our interests. We give you full control and have notified Captain Tazzuchi, at present in command, to this effect.

Yours truly,

p.p. Birdy Bird and Co.

To Captain O. Kettle,

(Isaac Bird.)

S.S. Parakeet, Bird Line, Aden.

"I see they have clapped me down on the bill heading for the Parakeet already," said Murray, "and you're shifted along in print for the new ship. Birds are getting on. But I've big doubts about three new boats all at one bite. One they might manage on a mortgage. But three? I don't think it. Old Ikey's too cautious."

"Messrs. Bird are your owners and mine," said Kettle significantly.

"Oh!" said the newly-made captain, "I'm not one of your old- fashioned sort that thinks an owner a little tin god."

"My view is," said Kettle, "that your owner pays you, and so is entitled to your respect so long as he is your owner. Besides that, whilst you are drawing pay, you're expected to carry out orders, whatever they may be, without question. But I don't think we'll talk any more about this, my lad. You're one of the newer school, I know, and you've got such a big notion of your own rights that we're not likely to agree. Besides, you've got to check my accounts and see I've left it all for you ship-shape, and I've to pull my bits of things together into a portmanteau. See you again before I go away, and we'll have a drop of whisky together to wish the Parakeet's new 'old man' a pile of luck."

At the edge of the harbor, Aden baked under the sun, but Kettle was not the man to filch his employer's time for unnecessary strolls ashore. The salvage steamer rolled at her anchor at the opposite side of the harbor, and Kettle and two portmanteaux were transhipped direct in one of the Parakeet's boats.

He was received on board by an affable Italian, who introduced himself as Captain Tazzuchi. The man spoke perfect English, and was hospitality personified. The little salvage steamer was barely 300 tons burden, and her accommodation was limited, but Tazzuchi put the best room in the ship at his guest's disposal, and said that anything that could act for his comfort should be done forthwith.

He was received on board by an affable Italian.

"Y'know, Captain," said Tazzuchi, "this is what you call a 'Dago' ship, and we serve out country wine as a regular ration. But I thought perhaps you'd like your own home ways best, and so I've ordered the ship's chandler ashore to send off a case of Scotch, and another of Chicago beef. Oh yes, and I sent also for some London pickles. I know how you English like your pickles."

In fact, all that a man could do in the way of outward attention Tazzuchi did, but somehow or other Captain Kettle got a suspicion of him from the very first moment of their meeting. Perhaps it was to some extent because the British mariner has always an instinctive and special distrust for the Latin nations; perhaps it was because the civility was a little unexpected and over- effusive. Putting himself in the Italian's place. Kettle certainly would not have gone out of his way to be pleasant to a foreigner who was sent practically to supersede him in a command.

But perhaps a second letter which he had received, giving him a more intimate list of the duties required, had something to do with this hostile feeling. It was from the same hand which had written the firm's formal letter, but it was couched in quite a different vein. Isaac Bird was evidently scared for his very commercial existence, and he thrust out his arms to Kettle on paper as his only savior. It seemed that Alexander Bird, the younger brother, had been running a little wild of late.

The wreck of the Grecian had been put up for auction; Alexander strolled into the room by accident, and bought at an exorbitant figure. He came and announced his purchase to Isaac, declaring it as an instance of his fine business instincts. Isaac set it down to whisky, and recriminations followed. Alexander in a huff said he would go out and over-look the salvage operations in person. Isaac opined that the firm might scrape to windward of bankruptcy by that means, and advised Alexander to take remarkable pains about keeping sober. But forthwith Alexander, still in his cups, "and at a music hall, too, a place he knows 'Isaac's' religious connection holds in profound horror," gets to brawling, and is next discovered in hospital with a broken thigh.

"I have found Alexander's department of the business very tangled," wrote Isaac, "when I began to go into his books the first day he was laid up, and the thought of this new complication drove me near crazy. Salvage is out of our line; Alexander should never have touched it. But there it is; money paid, and I've had to borrow; and engaging that Italian firm for the job was the best thing I could manage. What English firms wanted was out of all reason. I don't wonder at Lloyds selling wrecks for anything they will fetch. A pittance in cash is better than getting into the hands of these sharks" (sharks was heavily underscored). "And what guarantee have I that the firm will pocket even that pittance? How do I know that I shall see even the money outpaid again—let alone reasonable interest? None?"

There were several words erased here, and the writer went on with what was evidently considered a dramatic finish. "Hut stay," I say to myself, "you have Kettle. He is down in the Red Sea now, doing well. You had all along intended to promote him. Do it now, and set him to overlook this Italian salvage firm whilst the new boat is building. He is the one to see that Isaac Bird's foot doth not fall, for Captain O. Kettle is a godly man also."

The letter was shut off conventionally enough with the statement that the writer was Captain Kettle's truly, and ended in a post- scriptum tag to the effect that the envoy should still draw his two and a-half per cent, on net results. The actual figures had evidently not been conceded without a mental wrench, as the erasion beneath them showed, but there they stood in definite ink, and Kettle was not inclined to cavil at the process which deduced them.

However, although in his recent prosperity Kettle had assumed a hatred for risks, and bred a strong dislike for all those commercial adventures which lay beyond the ordinary rut and routine of trade, he took up his duties on the salvage steamer with a stout heart and cheerful estimate for the future. Ahead of him he had pleasant dreams of the big boat that was "building," and the increased monthly pay in store; and for the present, well, here was an owner's command, and of course that settled him firmly in the berth. He had been too long an obedient slave to ship-owners of every grade to have the least fancy for disputing the imperial will of Bird, Bird and Co.

Murray tooted his cheerful farewells on the Parakeet's siren as the little Italian salvage boat steamed out of the baking airs of Aden harbor, and ensigns were dipped with due formality. Tazzuchi was all hospitality. He invited Kettle to damage his palate with a black Italian "Virginia" cigar with a straw up the middle; he uncorked a bottle of the Scotch whisky with his own hand, splashed away the first wineglassful to get rid of the fusel oil, and put it ready for reference when his guest should feel a thirst; and he produced a couple of American pirated editions of English novels to give even intellect its dainty feast.

Kettle accepted it all with a dry civility. He had every expectation of upsetting this man's plans of robbery later on, and very possibly of coming into personal contact with him. But the ties of bread and salt did not disturb him. Though it was Tazzuchi who presented the Virginias and the novels, he took it for granted that Messrs. Bird, Bird and Co. had paid for them, and he was not averse to accepting a little luxury from the firm. The economical Isaac had cut down the commissariat on the Parakeet till a man had to be half-starved before he could stomach a meal.

The salvage steamer had a South of Europe leisureliness in her movements. Her utmost pace was nine knots, but, as eight was more economical for coal consumption, it was at that speed she moved. The wreck of the Grecian was out of the usual steam lane. She had, it appeared, got off her course in a fog, had run foul of a half-ebb reef which holed her in two compartments, and then been steered for the shore in the wild attempt to beach her before she sank. She had ceased floating, however, with some suddenness, and when the critical moment came not all of her people managed to scrape off with their lives in the boats. Those that stayed behind were incontinently drowned; those that got away found themselves in a gale (to which the fog gave place), and had so much trouble to keep afloat that they had no time left to make accurate determination of where their vessel sank; and when they were picked up could only give her whereabouts vaguely. However, they stated that the Grecian's mast-trucks remained above the water surface, and by these she could be found; and this fact was brought out strongly by the auctioneer who sold the wreck, and had due influence on the enterprising Alexander. "Masts!" said Alexander, who daily saw them bristling from a dock, "don't tell me you can miss masts anywhere."

But, as it chanced, it was only by a fluke that the salvage steamer stumbled across the wreck at all. She wandered for several days among an intensely dangerous archipelago, and many times over had narrow escapes from piling up her bones on one or other of those reefs with which the Red Sea in that quarter abounds. Tazzuchi navigated her in an ecstasy of nervousness, and Kettle (who regarded himself as a passenger for the time being) kept a private store of food and water-bottles handy, and saw that one of the quarter-boats was ready for hurried lowering. But nowhere did they see those mast-trucks. They did not sight so much as a scrap of floating wreckage.

There seemed, however, a good many dhow coasters dodging about in and among the reefs, and from these Kettle presently drew a deduction.

"Look here," he said to Tazzuchi one morning, "what price those gentry ashore having found the wreck already? I guess they aren't out here taking week-end trippers for sixpenny yachting cruises."

"No," said Tazzuchi, "and they aren't fishing; you can see that."

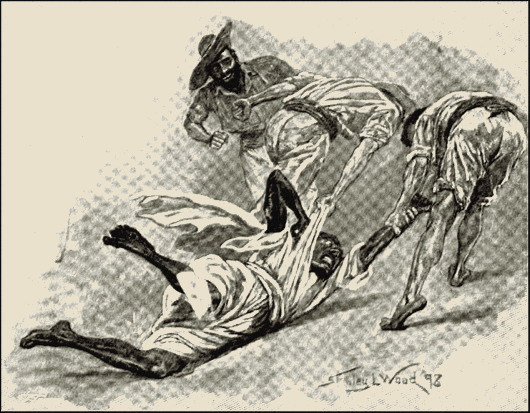

"Well, I give you the tip for what it's worth," said Kettle; and that afternoon the steamer was run up alongside a dhow, which tried desperately to escape. Her captain was dragged on board, and at that juncture Captain Kettle took upon himself to go below. He knew what would probably take place, and, though he disapproved of such methods strongly, he felt he could not interfere. He was in Bird, Bird and Co.'s employ, and what was being done would forward the firm's interest.

Her captain was dragged on board.

But presently came a noise of bellowing from the deck above, and then that was followed by shrill screams as the upper gamut of agony was reached. Kettle was prepared for rough handling, but at information gained by absolute torture he drew the line. It was clear that these cruel beggars of Italians were going too far.

"By James!" he muttered to himself, "owners or no owners, I can't stand this," and started hurriedly to go back to the deck. But before he reached the head of the companion-way the cries of pain ceased, and so he stood where he was on the stair, and waited. The engines rumbled, and the steamer once more gathered way. A clamor of barbaric voices reached him, which gradually died into quietude. It was clear they were leaving the dhow behind.

Captain Kettle drew a long breath. They would stick at little, these Dagos, in getting the salvage of the Grecian, and it seemed preposterous to suppose that once they gripped the specie in their own fingers they would ever give it up for the paltry pay which had been offered by Bird, Bird and Co. Their own poverty was aching. He saw it whenever he looked about the patched little steamer. He felt it whenever he sat down to one of their painfully frugal meals.

Still, though no man knew more bitterly than Kettle himself from past experience what poverty meant, and how it cut, the poverty of these Italians was no concern of his just then. They were paid servants of the owners exactly as he was, and it was his duty to see that they earned their hire. He took it that he was one against the whole ship's company, but the odds did not daunt him. On the contrary, something of his old fighting spirit, which had been of late hustled into the background by snug commercial prosperity, came back to him. And besides, he had always at his call that exquisite pride of race which has so many times given victory to the Anglo-Saxon over the Latin, when all reasonable balances should have made it go the other way.

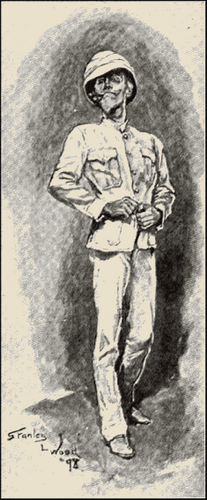

By a sort of instinct he buttoned up his trim white drill coat, and stepped out on deck. There would be no scuffle yet awhile. With the specie that would make the temptation still snugly stored on the sea-floor, the dirty, untidy Italians were still all affability. Indeed, as soon as he appeared, Tazzuchi himself stepped down off the upper bridge to give him the news.

Kettle buttoned up his trim white

drill coat, and stepped out on deck.

"How do you think those crafty imps have managed it?" he cried, with a gesture. "Why they dived down and cut off her masts below water level. The funnel was out of sight already. They just thought they were going to have the skimming of that wreck themselves. No wonder we couldn't pick her up."

"Cute beggars," said Kettle.

"I've bagged a pilot. If he takes us there straight, he gets backsheesh. If he doesn't, he eats more stick. I think," said Captain Tazzuchi, with a wide smile, "that he'll take us there the quickest road."

"Shouldn't wonder," said Kettle. "But don't be surprised if his friends come round and make things ugly. When those Red Sea niggers get their fingers in a wreck, they think's it's their wreck."

"Let them come. We were ready for this sort of entertainment when we sailed, and there are plenty of rifles and cartridges in the cabin. If there is any trouble, we shall shoot; and if we begin that game, we shall just imagine they are Abyssinians, and shoot to kill. The Italians have a big bill to pay with those jokers, anyway." He tapped Kettle on the shoulder. "And look at those two brass signal guns. Captain. If we break up some fire-bars for shot, they'll smash the side of any dhow in the Red Sea."

Under the black captive's guidance, the salvage steamer soon put a term to her search. For two more hours she threaded her way among surf which broke over unseen reefs, and swung round the capes of a rocky archipelago, and then the pilot gave his word and the engines were stopped and a rusty cable roared out till an anchor got its hold of the ground. A boat was lowered with air- pump already stepped amidships, and the boat's crew with eager hands assisted the diver to make his toilet.

"You chaps seem keen enough," said Kettle, as he watched the trail of air bubbles which showed the man's progress on the sea floor below.

"They have each got a stake in the venture."

"I bet they have," was Kettle's grim comment to himself.

The kidnapped skipper of the dhow, it seemed, had done his pilotage with a fine accuracy. The salvage steamer had been anchored in a good position, and between them two divers in two boats found the Grecian's wreck in half an hour. Indeed, they had made their first descent practically within hand-touch of her, but the water was full of a milky clay and very opaque, and sight below the surface was consequently limited.

They came up to the air for a quarter of an hour's spell and made their announcement, and then the copper helmets were clapped into place again, and once more like a pair of uncouth sea monsters they slowly and clumsily faded away into the depths. A gabble of excited Italian kept pace to the turning of the air-pumps, and of that language Kettle knew barely a score of words. Practically these people might have weaved any kind of plot noisily and under his very nose without his being any the wiser, and this possibility did little to quell his suspicions.

But still Tazzuchi was all outward frankness. "It's as well we brought out this little steamboat just to skim the wreck and survey her," he said. "If they'd waited to fit out a big salvage expedition, to raise her straight off, I reckon there wouldn't have been much left but iron plates and coal bunkers. These Red Sea niggers are pretty useful at looting, once they start. The beggars can dive pretty nearly as well and as long in their naked skins as their betters can in a proper diving suit."

Each time the divers came up from the opaque white water they brought more reports. Binnacles, whistle, wheels, and all movable deck fittings were gone already. The chart-house had been looted down to the bare boards. Hatches were off, both forward and aft, and already the cargo had begun to diminish. The black men of the district had been making good use of their time; and as the probabilities were that they would return in force to glean from this store which they considered legally theirs, it was advisable to collect as much as possible into the salvage steamer before any disturbances began.

News came from the cool mysterious water to the baking region of air above, almost at the second hour of the search, that the Grecian could never be refloated. In addition to the holes already made in two of her compartments, she had settled on a sharp jag of rock, which had pierced her in a third place aft. But at the same time this one piece of rock was the only solid spot in the neighborhood. All the rest of the sea floor was paved with pulpy white clay, and in this the unfortunate wreck had settled till already it was flush with her lower decks. There were evidences, too, that the ooze was creeping higher every day, so that all that remained was to strip her as quickly as might be before she was swallowed up for always.

Tazzuchi asked Captain Kettle for his opinion that night in the chart-house. "I'm to be guided by you, of course," he said, "but my idea is that we should go for the specie first thing, and let everything slide till that's snugly on board here. Birds gave £5,400 for the wreck, and there's £8,000 in cash down there in a room they built specially for it over the shaft-tunnel. If we can grab that, it will pay our expenses and commission and all the other actual outlay, and Birds will be out of the wood. Afterward, if we can weigh any more of the cargo, well, that will be all clear profit."

"Yes," thought Kettle, "you want those gold boxes in your hands, you blessed Dago, and then you'll begin to play your monkey tricks. I wonder if you think you're going to jam a knife into me by way of making things snug and safe?" But aloud he expressed agreement to Captain Tazzuchi's plan.

He felt that this was diplomacy, and though the diplomatic art was new and strange to him, he told himself that it was the correct weapon to use under the circumstances. He had risen out of his old grade of hole-and-corner shipmaster, where it had been his province to carry things through by rough blows and violent words. He was a Captain in a regular line—the Bird line—now, and (with a trifle of a sigh) he remembered that wild fights and scrimmages were beneath the dignity of his position.

Accordingly, as soon as dawn gave a waking light, the boats were put out again, and the divers were given orders to let the further survey of the vessel rest, and put all their efforts into getting the specie boxes on to the end of the salvage steamer's winch chain. They were quickly helmed and sent below, and presently an increased cloudiness in the water told him that they were actively at work. A lot of dhows were showing here and there amongst the reefs, obviously watching them, and Tazzuchi was beginning to get nervous.

"We're in for trouble, I'm afraid," he said to Kettle. "That rock on which she's settled astern has made a hole in her you could drive a cart through. I suppose it was a tight-fitting hole at first, but as she settled more and moved about, it's got enlarged same as the hole in a tin of beef does when you begin to waggle it with the can-opener."

"Well?"

"Didn't you hear the report they've just sung off from the boats? Oh, I forgot, you don't understand Italian. Well, the news is that the rock's acted as a can-opener to such fine effect that it's split a hole in the bottom of the strong room, and those gold boxes have toppled through."

"And buried themselves in the slime?"

"That's it. And Lord knows how many feet they've sunk. It's dreadful stuff to dig amongst—slides in on you as soon as you start to dig, and levels up. They'll have to brattice as they work. It'll be a big job."

All that day Kettle watched the sea with an anxious eye. In the two boats men ground at the air-pumps under the aching sunlight. From below the mud came up in white billows, which danced, and swirled, and eddied as the air bubbles from the divers' exhaust valves stirred it. And out beyond, in and among the reefs, and along the distant shore, which swung and shimmered in the heat haze, hungry dhows prowled like carrion birds temporarily driven away from a prey.

Tazzuchi and the chief engineer busied themselves in binding together fragments of fire-bars with iron wire. The Italian shipmaster had a great notion of the damage his signal-guns could do against a dhow, if they were provided with orthodox solid shot. As a point of fact they never came into action. As soon as the second night came down, and the darkness became fairly fixed in hue, there began to crackle out of the distance a desultory rifle fire from every quarter of the compass. It was not very heavy—at the outside there were not a score of weapons firing, and it could not be called accurate since not one bullet in twenty so much as hit the steamer; but it was annoying for all that, and as the marksmen and their vessels were completely swallowed up by the blackness of the night, it was impossible to repay their compliments in kind.

Morning showed the damage of one port window smashed, two panes gone from the engine-room skylight, and the air-pump in one of the boats alongside with a plunger neatly cut into two pieces. But there was a spare air-pump in store, and after dawn came, work went on as usual. The dhows came no nearer, neither did they go much further away. They pottered about just beyond rifle shot, and their numbers were slightly increased. Tazzuchi, full of enthusiasm for his artillery, tried a carefully aimed shot at one of the largest. But the explosion was quite outdone in noise by the cackle of laughter which followed it. So slow was the flight of the missile that the eye could trace it. So short was its journey, and so curved its trajectory, that it came very near to hitting one of the boats of the divers, and the men working there cried out in derision that they would catch cold by being wetted by the spray.

"Well," thought Kettle, "these are pretty cool hands for Dagos, anyway. I'm going to have a fine tough time of it when my part of the scuffle comes."

That night he had a still further taste of their quality. So soon as darkness fell, the dhows closed in again and recommenced their sniping. They kept under weigh, and so it did little enough good to aim back at the flashes. But Tazzuchi, with half a dozen keen spirits, got down into one of the boats with their rifles and knives, and a drum of paraffin, and pulled away silently into the blackness.

There was silence for quite half an hour, and the suspense on the anchored steamer was vivid enough to have shaken trained men. Yet these Italian artificers and merchant seamen seemed to take it as coolly as though such sorties were an everyday occurrence. But at the end of that time there was a splutter of shots, a few faint squeals, and then a bonfire lighted up away in the darkness.

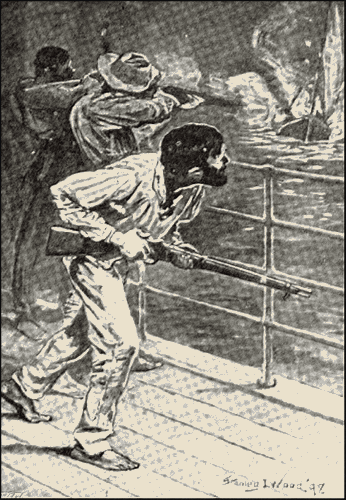

The blaze grew rapidly, and showed in its heart the outline of a dhow with human figures on it. With promptness every man on the steamer emptied his rifle at the mark, and continued the fusillade till the dhow was deserted. They had all done their spell of military service, and they chose to decide that these snipers were Abyssinians, and did their best toward squaring the national accounts.

Every man on the steamer emptied his rifle at the mark.

Tazzuchi and his friends returned in the boat, safe and jubilant, and for the rest of that night the little salvage steamer was left in quietude. With the next daybreak the divers and their attendants once more applied themselves to labor. Kettle, as he watched, was amazed to see the energy they put into it. Certainly they seemed keen enough to get the specie weighed, and on board. Whatever piratical plans they had got made up were evidently for afterward.

But when day after day passed, and still none of the treasure was brought to the surface, he began to modify this original opinion. Tazzuchi—translating the divers' reports—said that the cause of the delay was the softness of the sea-floor. The heavy chests had sunk deep into the ooze, and directly a spadeful of the horrible slime was dug away, more slid in to fill the gap. Of course this might be true; but there was only Tazzuchi's word for it. The sea was too consistently opaque to give one a chance of seeing down from above the surface.

Now as suspicion had got so deep a hold on Captain Kettle's mind, he began to cudgel his brain for some new method by which the Italians could serve their purpose. He put himself supposititiously in Tazzuchi's place, and made piratical theories by the score. Most of them he had to dismiss after examination as impracticable, others he eliminated by natural selection; and finally one stood out as practicable beyond all the rest.

For one thing it did not want many participants; only the actual divers and Tazzuchi himself. For another, it would not brand the whole gang of them as criminals and pirates, but (properly managed) would make them rich without any advertised stigma or stain. In simple words, the method was this: the gold boxes must be removed from their original site, and hidden elsewhere under the water close at hand. The friendly slime would bury them snugly out of sight. The old report of "un-get-at-able" would be adhered to, and finally the steamer would give up further salvage operations as hopeless (after fishing up some useless cargo out of the holds as a conscience salve) and steam away to port. There Tazzuchi and his friends would either desert or get themselves dismissed, charter a small vessel of their own, and go back for the plunder; and with £8,000 in clear hard cash to divide, live prosperously (from an Italian standpoint) ever afterward.

Kettle felt an unimaginative man's complacency in ferreting out such a dramatic scheme, and began to think next upon the somewhat important detail of how to get proofs before he commenced to frustrate it. Chance seemed to make Tazzuchi play into his hand. The air-pump which had been damaged by the rifle bullet had been mended by the steamer's engineers, and as there were two or three spare diving dresses on the ship. Captain Tazzuchi expressed his intention of making a descent in person to inspect progress.

"I didn't do it before, because I didn't want to make the men break time, but I can go down now without interrupting their work. Will you come off in the boat with me. Captain, and hand my lifeline?"

"I'll borrow one of those spare dresses and share the pump with you," said Kettle.

Tazzuchi was visibly startled. "What do you mean?"

"I mean that the pump will give air for two, and I'm coming down with you."

"But you know nothing about diving, and you might have an accident, and I should be responsible."

"Oh, I'll risk that! You must nursery-maid me a bit."

Tazzuchi lowered his voice. "To tell the truth, I'm going to pay a surprise visit. I want to make sure those chaps below are doing the square thing. If they aren't, and I catch them, there'll be a row, and they'll use their knives."

"H'm!" said Kettle, "I've got no use for your local weapon as a general thing. I find a gun handiest. But at a pinch like this I'll borrow a knife of you, and if it comes to any one cutting my air-tube you'll find I can use it pretty mischievously."

"I wish you wouldn't insist upon this," said Tazzuchi persuasively.

"I'm going to, anyway."

"I'm going down merely because it's my duty."

"That's the very same reason that's taking me. Captain. I must ask you not to make any more objections. I'm a man that never changes his mind, once it's made up."

Whereupon Tazzuchi shrugged his shoulders, and gave way.

"Now," thought Kettle to himself, "that man's made up his mind to kill me if he gets the glimmer of a chance, and, as I'm not going to get wiped out this journey, he'll do with a lot of watching."

It has been the present writer's business at one time and another to point out that Captain Owen Kettle is a man of iron nerve; but I cannot call to mind any instance where his indomitable courage was more severely tried than in this voluntary descent in the diving dress. The world beneath the waters was strange and dangerous to him; his companion was a man against whom he held the blackest suspicion; the men at the pump (whose language he did not understand) might any moment cut off his supply, and leave him to drown like a puppy under a bucket. The circumstances combined were enough to daunt a Bayard.

But Kettle felt that the men in the boat, who helped to adjust his stiff rubber dress, were regarding him with more than ordinary curiosity, and, for his own pride's sake, he preserved an unruffled face. He even tried a rude jest in their own tongue before they made fast the helmet on his head, and the cackle of their laughter was the last sound he heard before the metal dome closed the audible world away from him.

They hung the weights over his chest and back, and Tazzuchi signed to him to descend. Kettle hitched round the sheath-knife to the front of his belt, and signed with politeness, "After you."

Tazzuchi did not argue the matter. He lifted his clumsy lead- soled feet over the side of the boat, got on the ladder, and climbed down out of sight. Kettle followed. The chill of the water crept up and closed over his head; the steady throb- throb of the air-pump beat against his skull; and a little shiver took him in one small spot between the shoulder blades, because he knew that it was there that an Italian, if he can manage it, always plants a knife in his enemy.

He reached the end of the ladder and slid down a rope. He felt curiously corky and insecure, but still when he reached the bottom he sank up to his knees in impalpable mud. He could foggily see Tazzuchi a few paces away waiting for him, and he went up to him at once. If the men in the boat, acting on orders, cut his air-tube, he wanted to be in a position to cut Captain Tazzuchi's also with promptness.

However, everything went peacefully just then. The Italian set off down a track in the slime, and Kettle waded laboriously after him. It was terrible work making a passage through that white glutinous ooze, but they came to the wreck directly, and, working round her rusty flank, stood beside a great shallow pit, where two weird-looking gray sea-monsters showed in dim outline through the dense fog of the water.

Kettle waded laboriously after him.

Sound does not carry down there in that quiet world, and the two new-comers stood for long enough before the two workers observed them. But one chanced to look up and see them watching and jogged the other with his spade, and then both frantically beckoned the visitors to come down into the pit. Tazzuchi led, and Kettle followed, wallowing down the slopes of slime, and there at the bottom, in the dim, milky light, one of the professional divers slipped a shovel into his hand and thrust it downward, till it jarred against something solid underfoot.

It was clear they had come upon the gold boxes, and they wished to impress upon the visitors, in underwater dumb show, that the find had only been made that very minute. It was a strange enough performance. Half-seen hands snapped red fingers in triumph. Ponderously booted feet did a dance of ecstasy in three feet of gluey mud. And meanwhile, Kettle, with a hand on the haft of his knife, edged away from this uncanny demonstration, lest some one should slit his air-tube before he could prevent it.

He had seen what he wanted; he had no reason to wait longer; and besides, being a novice at diving, his lungs were half burst already in the effort to get breath, and his head was singing like a tea-urn. The gold boxes were there, and if they were not brought to the surface, and carried honestly to Suez, the matter would have to be fought out above in God's open air, and not in that horrible choking quagmire of slime and cruel water. And so, still guarding himself cannily, he got back again to the boat, and almost had it in him to shake hands with the men who eased him of that intolerable helmet.

Now far be it from me to raise even a suspicion that Captain Owen Kettle resented the fact that he had been robbed of a scuffle when the little salvage steamer actually did bring up in Suez harbor with the specie honestly locked in one of her staterooms. But that he was violently angry he admits himself without qualification. He says he kicked himself for being such a bad judge of men.

The Parakeet was in when they arrived, rebunkering for the run home, and Murray came off as fast as a crew could drive his boat to inquire the news.

He saw Tazzuchi on the deck and accosted him with a vigorous handshake, and a "Hullo, Fizzhookey, old man, how goes it? Who'd have thought of seeing you here? Howdy, Captain Kettle. Had good fishing?"

"Do you know Captain Tazzuchi?"

"Somewhat. Why, we were both boys on the Conway together."

"You're making some mistake. Captain Tazzuchi is an Italian."

"Oh, am I?" said Tazzuchi. "Not much of the Dago about me except the name."

"Well, you never told me that before."

"You never asked me, that I know of. I speak about enough of the lingo to carry on duty with, and I serve on an Italian ship because I couldn't get a skipper's billet on anything else. But I'm as English as either of you, and as English as Birds—or more English than Birds, seeing that they come from somewhere near Jerusalem. Great Scot, Captain Kettle, can't you tell a Dago yet for sure? Where have you been all your days?"

Murray laughed. "Well, come across and discuss it in the Parakeet. I've got a case of champagne on board to wet my new ticket."

"Stay half a minute," said Tazzuchi, "we'll just get those boxes of gold down into your boat, Murray, and ferry them across. I sha'n't be sorry to have them out of my responsibility. They're too big a temptation to leave handy for the crew there is on board here."

"Phew!" said Kettle, "it's hot here in Suez. Great James! to think of the way I've been sweating about this blame' ship without a scrap of need of it. Here, hurry up with the lucre- boxes. I want to get across to the old Parakeet and wash the taste of a lot of things out of my mouth."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.