RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

A Master of Fortune, 1898,

with "The Derelict"

"HER cargo'll have shifted," said the third mate, "and when she got that list her people will have felt frightened and left her."

"She's a scary look to her, with her yard-arms spiking every other sea," said Captain Image, "and her decks like the side of a house. I shouldn't care to navigate a craft that preferred to lie down on her beam ends myself."

"Take this glass, sir, and you'll see the lee quarter-boat davit-tackles are overhauled. That means they got at least one boat in the water. To my mind she's derelict."

"Yard-arm tackles rigged and over-hauled, too," said Captain Image. "She'll have carried a big boat on the top of that house amidships, and that's gone, too. Well, I hope her crew have got to dry land somewhere, or been picked up, poor beggars. Nasty things, those old wind-jammers, Mr. Strake. Give me steam."

"But there's a pile of money in her still," said the third mate, following up his own thoughts. "She's an iron ship, and she'll be two thousand tons, good. Likely enough in the 'Frisco grain trade. Seems to me a new ship, too; anyway, she's got those humbugging patent tops'ls."

"And you're thinking she'd be a nice plum if we could pluck her in anywhere?" said Image, reading what was in his mind.

"Well, me lad, I know that as well as yon, and no one would be pleaseder to pocket £300. But the old M'poso's a mailboat, and because she's got about a quarter of a hundredweight of badly spelt letters on board, she can't do that sort of salvage work if there's no life-saving thrown in as an extra reason. Besides, we're behind time as it is, with smelling round for so much cargo, and though I shall draw my two and a-half per cent, on that, I shall have it all to pay away again, and more to boot, in fines for being late. No, I tell you it isn't all sheer profit and delight in being skipper on one of those West African coast boats. And there's another thing: the Chief was telling me only this morning that they've figured it very close on the coal. We only have what'll take us to Liverpool ourselves, without trying to pull a yawing, heavy, towing thing like that on behind us."

Strake drummed at the white rail of the bridge. He was a very young man, and he was very keen on getting the chance of distinguishing himself; and here, on the warm, windless swells abeam, the chance seemed to sit beckoning him. "I've been thinking, sir, if you can lend me half a dozen men, I could take her in somewhere myself."

"I'm as likely to lend you half a dozen angels. Look at the deck hands; look at the sickly trip this has been. We've had to put some of them on double tricks at the wheel already, and as for getting any painting done, or having the ship cleaned up a bit, why, I can see we shall go into Liverpool as dirty as a Geordie collier. Besides, Mr. Strake, I believe I've told you once or twice already that you're not much use yourself, but anyway you're the best that's left, and I'm having to stand watch and watch with you as it is. If the mate gets out of his bed between here and home, it'll be to go over the side, and the second mate's nearly as bad with that nasty blackwater fever only just off him; and there you are. Mr. Strake, if you have a penn'oth of brains stowed away anywhere, I wish to whiskers you'd show 'em sometimes."

"Old man's mad at losing a nice lump of salvage," thought Strake. "Natural, I guess." So he said quietly: "Ay, ay, sir," and walked away to the other end of the bridge.

Captain Image followed him half-way, but stopped irresolutely with his hand on the engine-room telegraph. On the fore main deck below him his old friend, Captain Owen Kettle, was leaning on the rail, staring wistfully at the derelict.

"Poor beggar," Image mused, "'tisn't hard to guess what he's thinking about. I wonder if I could fix it for him to take her home. It might set him on his legs again, and he's come low enough. Lord knows. If I hadn't given him a room in the first-class for old times' sake, he'd have had to go home, after his trouble on the West Coast, as a distressed seaman, and touch his cap to me when I passed. I've not done badly by him, but I shall have to pay for that room in the first-class out of my own pocket, and if he was to take that old wind-jammer in somewhere, he'd fork out, and very like give me a dash besides.

"Yes, I will say that about Kettle; he's honest as a barkeeper, and generous besides. He's a steamer sailor, of course, and has been most of these years, and how he'll do the white wings business again. Lord only knows. Forget he hasn't got engines till it's too late, and then drown himself probably. However, that's his palaver. Where we're going to scratch him up a crew from's the thing that bothers me. Well, we'll see." He leaned down over the bridge rail, and called.

Kettle looked up.

"Here a minute. Captain."

Poor Kettle's eye lit, and he came up the ladders with a boy's quickness.

Image nodded toward the deserted vessel. "Fine full-rigger, hasn't she been? What do you make her out for?"

"'Frisco grain ship. Stuff in bulk. And it's shifted."

"Looks that way. Have you forgotten all your 'mainsail haul' and the square-rig gymnastics?"

"I'm hard enough pushed now to remember even the theory-sums they taught at navigation school if I thought they would serve me."

"I know. And I'm as sorry for you. Captain, as I can hold. But you see, it's this: I'm short of sailormen; I've barely enough to steer and keep the decks clean; anyway I've none to spare."

"I don't ask for fancy goods," said Kettle eagerly. "Give me anything with hands on it—apes, niggers, stokers, what you like, and I'll soon teach them their dancing steps."

Captain Image pulled at his moustache. "The trouble of it is, we are short everywhere. It's been a sickly voyage, this. I couldn't let you have more than two out of the stokehold, and even if we take those, the old Chief will be fit to eat me. You could do nothing with that big vessel with only two beside yourself."

"Let me go round and see. I believe I can rake up enough hands somehow."

"Well, you must be quick about it," said Image. "I've wasted more than enough time already. I can only give you five minutes. Captain. Oh, by the way, there's a nigger stowaway from Sarry Leone you can take if you like. He's a stonemason or some such foolishness, and I don't mind having him drowned. If you hammer him enough, probably he'll learn how to put some weight on a brace."

"That stonemason's just the man I can use," said Kettle. "Get him for me. I'll never forget your kindness over this. Captain, and you may depend upon me to do the square thing by you if I get her home."

Captain Kettle ran off down the bridge and was quickly out of sight, and hard at his quest for volunteers. Captain Image waited a minute, and he turned to his third mate. "Now, me lad," he said, "I know you're disappointed; but with the other mates sick like they are, it's just impossible for me to let you go. If I did, the Company would sack me, and the dirty Board of Trade would probably take away my ticket. So you may as well do the kind, and help poor old Cappie Kettle. You see what he's come down to, through no fault of his own. You're young, and you're full to the coamings with confidence. I'm older, and I know that luck may very well get up and hit me, and I'll be wanting a helping hand myself It's a rotten, undependable trade, this sailoring. You might just call the carpenter, and get the cover off that smaller life-boat."

"You think he'll get a crew, then, sir, and not our deckhands?"

"Him? He'll get some things with legs and arms to them, if he has to whittle 'em out of kindling-wood. It's not that that'll stop Cappie Kettle now, me lad."

The third mate went off, sent for the carpenter, and started to get a lifeboat cleared and ready for launching. Captain Image fell to anxiously pacing the upper bridge, and presently Kettle came back to him.

"Well, Captain," he said, "I got a fine crew to volunteer, if you can see your way to let me have them. There's a fireman and a trimmer, both English; there's a third-class passenger—a Dago of some sort, I think he is, that was a ganger on the Congo railway—and there's Mr. Dayton-Philipps; and if you send me along your nigger stonemason, that'll make a good, strong ship's company."

"Dayton-Philipps!" said Image. "Why, he's an officer in the English Army, and he's been in command of Haussa troops on the Gold Coast, and he's been some sort of a Resident, or political thing up in one of those nigger towns at the back there. What's he want to go for?"

"Said he'd come for the fun of the thing."

Captain Image gave a grim laugh. "Well, I think he'll find all the fun he's any use for before he's ashore again. Extraordinary thing some people can't see they're well off when they've got a job ashore. Now, Mr. Strake, hurry with that boat and get her lowered away. You're to take charge and bring her back; and mind, you're not to leave the captain here and his gang aboard if the vessel's too badly wrecked to be safe."

He turned to Kettle. "Excuse my giving that last order, old man, but I know how keen you are, and I'm not going to let you go off to try and navigate a sieve. You're far too good a man to be drowned uselessly."

The word was "Hurry," now that the final decision had been given, and the davit tackles squeaked out as the lifeboat jerked down toward the water. She rode there at the end of her painter, and the three rowers and the third mate fended her off, while Kettle's crew of nondescripts scrambled unhandily down to take their places. The negro stowaway refused stubbornly to leave the steamer, and so was lowered ignominiously in a bowline, and then, as he still objected loudly that he came from Sa' Leone, and was a free British subject, some one crammed a bucket over his head, amidst the uproarious laughter of the onlookers.

Captain Kettle swung himself down the swaying Jacob's ladder, and the boat's painter was cast off; and under three oars she moved slowly off over the hot sun-kissed swells. Advice and farewells boomed like a thunderstorm from the steamer, and an animated frieze of faces and figures and waving head-gear decorated her rail.

Ahead of them, the quiet ship shouldered clumsily over the rollers, now gushing down till she dipped her martingale, now swooping up again, sending whole cataracts of water swirling along her waist.

The men in the boat regarded her with curious eyes as they drew nearer. Even the three rowers turned their heads, and were called to order therefor by the mate at the tiller. A red ensign was seized jack downward in her main rigging, the highest note of the sailorman's agony of distress. On its wooden case, in her starboard fore-rigging, a dioptric lens sent out the faint green glow of a lamp's light into the sunshine.

The third mate drew attention to this last "Lot of oil in that lamp," he said, "or it means they haven't deserted her very long. To my mind, it must have been in yesterday's breeze her cargo shifted, and scared her people into leaving her."

"We shall see," said Kettle, still staring intently ahead.

The boat was run up cannily alongside, and Kettle jumped into the main chains and clambered on board over the bulwarks. "Now, pass up my crew, Mr. Strake," said he.

"Well, Mr. Mate," said Kettle grimly, "I hope you'll decide she's seaworthy, because, whatever view you take of it, as I've got this far, here I'm going to stay."

The mate frowned. He was a young man; he was here in authority, and he had a great notion of making his authority felt. Captain Kettle was to him merely a down-on-his-luck free-passage nobody, and as the mate was large and lusty he did not anticipate trouble. So he remarked rather crabbedly that he was going to obey his orders, and went aft along the slanting deck.

It was clear that the vessel had been swept—badly swept. Ropes-ends streamed here and there and overboard in every direction, and everything movable had been carried away eternally by the sea. A goodly part of the starboard bulwarks had vanished, and the swells gushed in and out as they chose. But the hatch tarpaulins and companions were still in place; and though it was clear from the list (which was so great that they could not walk without holding on) that her cargo was badly shifted, there was no evidence so far that she was otherwise than sound.

The third mate led the way on to the poop, opened the companion doors and slide, and went below. Kettle followed. There was a cabin with state rooms off it, littered, but dry. Strake went down on his knees beneath the table, searching for something. "Lazaret hatch ought to be down here," he explained. "I want to see in there. Ah, it is."

He got his fingers in the ring and pulled it back. Then he whistled. "Half-full of water," he said. "I thought so from the way she floated. It's up to the beams down here. Likely enough she'll have started a plate somewhere. 'Fraid it's no go for you, Captain. Why, if a breeze was to come on, half the side of her might drop out, and she'd go down like a stone."

Now to Kettle's honor be it said (seeing what he had in his mind) he did not tackle the man as he knelt there peering into the lazaret. Instead he waited till he stood up again, and then made his statement coldly and deliberately.

"This ship's not too dangerous for me, and I choose to judge. And if she'll do for me, she's good enough for the crew I've got in your boat. Now I want them on deck, and at work without any more palaver."

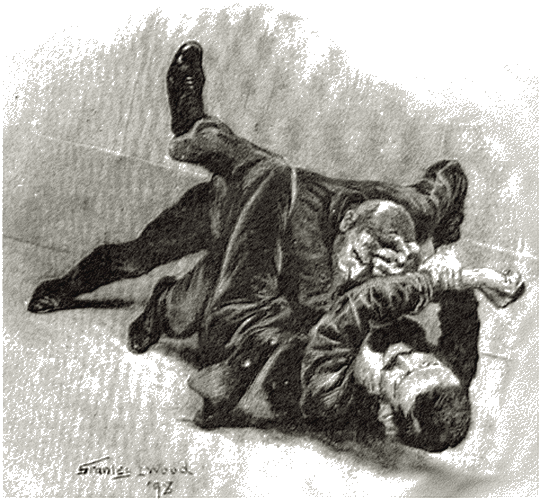

"Do you, by God!" said the mate, and then the pair of them closed without any further preliminaries. They were both of them well used to quick rough-and-tumbles, and they both of them knew that the man who gets the first grip in these wrestles usually wins, and instinctively each tried to act on that knowledge.

But if the third mate had bulk and strength, Kettle had science and abundant wiriness; and though the pair of them lost their footing on the sloping cabin floor at the first embrace, and wriggled over and under like a pair of eels, Captain Kettle got a thumb artistically fixed in the bigger man's windpipe, and held it there doggedly. The mate, growing more and more purple, hit out with savage force, but Kettle dodged the bull-like blows like the boxer he was, and the mate's efforts gradually relaxed.

Captain Kettle got a thumb artistically

fixed in the bigger man's windpipe.

But at this point they were interrupted. "That wobbly boat was making me sea-sick," said a voice, "so I came on board here. Hullo, you fellows!"

Kettle looked up. "Mr. Philipps," he said, "I wish you'd go and get the rest of our crew on deck out of the boat."

"But what are you two doing down there?"

"We disagreed over a question of judgment. He said this ship isn't safe, and I shouldn't have the chance to take her home. I say there's nothing wrong with her that can't be remedied, and home I'm going to take her, anyway. It might be the one chance in my life, sir, of getting a balance at the bank, and I'm not going to miss it."

"Ho!" said Dayton-Philipps.

"If you don't like to come, you needn't," said Kettle. "But I'm going to have the stonemason and the Dago, and those two coal-heavers. Perhaps you'd better go back. It will be wet, hard work here; no way the sort of job to suit a soldier."

Dayton-Philipps flushed slightly, and then he laughed. "I suppose that's intended to be nasty," he said. "Well, Captain, I shall have to prove to you that we soldiers are equal to a bit of manual labor sometimes. By the way, I don't want to interfere in a personal matter, but I'd take it as a favor if you wouldn't kill Strake quite. I rather like him."

"Anything to oblige," said Kettle, and took his thumb out of the third mate's windpipe. "And now, sir, as you've so to speak signed on for duty here, away with you on deck and get those four other beauties up out of the boat."

Dayton-Philipps touched his hat and grinned. "Ay, ay, sir," he said, and went back up the companion.

Shortly afterward he came to report the men on board, and Kettle addressed his late opponent. "Now, look here, young man, I don't want to have more trouble on deck before the hands. Have you had enough?"

"For the present, yes," said the third mate huskily. "But I hope we'll meet again some other day to have a bit of further talk."

"I am sure I shall be quite ready. No man ever accused me of refusing a scrap. But, me lad, just take one tip from me: don't you go and make Captain Image anxious by saying this ship isn't seaworthy, or he'll begin to ask questions, and he may get you to tell more than you're proud about."

"You can go and get drowned your own way. As far as I am concerned, no one will guess it's coming off till they see it in the papers."

"Thanks," said Kettle. "I knew you'd be nice about it."

The third mate went down to his boat, and the three rowers took her across to the M'poso, where she was hauled up to davits again. The steamer's siren boomed out farewells, as she got under way again, and Kettle with his own hands unbent the reversed ensign from the ship's main rigging, and ran it up to the peak and dipped it three times in salute.

He breathed more freely now. One chance and a host of unknown dangers lay ahead of him. But the dangers he disregarded. Dangers were nothing new to him. It was the chance which lured him on. Chances so seldom came in his way, that he intended to make this one into a certainty if the efforts of desperation could do it.

Alone of all the six men on the derelict, Captain Kettle had knowledge of the seaman's craft; but, for the present, thews and not seamanship were required. The vessel lay in pathetic helplessness on her side, liable to capsize in the first squall which came along, and their first effort must be to get her in proper trim whilst the calm continued. They knocked out the wedges with their heels, and got the tarpaulins off the main hatch; they pulled away the hatch covers, and saw beneath them smooth slopes of yellow grain.

As though they were an invitation to work, shovels were made fast along the coamings of the hatch. The six men took these, and with shouts dropped down upon the grain. And then began a period of Homeric toil. The fireman and the coal-trimmer set the pace, and with a fine contempt for the unhandiness of amateurs did not fail to give a display of their utmost. Kettle and Dayton-Philipps gamely kept level with them. The Italian ganger turned out to have his pride also, and did not lag, and only the free-born British subject from Sierra Leone endeavored to shirk his due proportion of the toil.

But high-minded theories as to the rights of man were regarded here as little as threats to lay information before a justice of the peace; and under the sledge-hammer arguments of shovel blows from whoever happened to be next to him, the unfortunate colored gentleman descended to the grade of nigger again (which he had repeatedly sworn never to do), and toiled and sweated equally with his betters.

The heat under the decks was stifling, and dust rose from the wheat in choking volumes, but the pace of the circling shovels was never allowed to slacken. They worked there stripped to trousers, and they understood, one and all, that they were working for their lives. A breeze had sprung up almost as soon as the M'poso had steamed away, and hourly it was freshening: the barometer in the cabin was registering a steady fall; the sky was banking up with heavy clouds.

Kettle had handled sheets and braces and hove the vessel to so as to steady her as they worked, but she still labored heavily in the sea, and beneath them they could hear the leaden swish of water in the floor of the hold beneath. Their labor was having its effect, and by infinitesimal gradations they were counteracting the list and getting the ship upright; but the wind was worsening, and it seemed to them also that the water was getting deeper under their feet, and that the vessel rode more sluggishly.

So far the well had not been sounded. It is no use getting alarming statistics to discourage one's self unnecessarily. But after night had fallen, and it was impossible to see to work in the gloomy hold any longer without lamps, Captain Kettle took the sounding-rod and found eight feet.

He mentioned this when he took down the lanterns into the hold, but he did not think it necessary to add that as the sounding had been taken with the well on the slant it was therefore considerably under the truth. Still he sent Dayton-Philipps and the trimmer on deck to take a spell at the pumps, and himself resumed his shovel-work alongside the others.

Straight away on through the night the six men stuck to their savage toil, the blood from their blistered hands reddening the shafts of the shovels. Every now and again one or another of them, choked with the dust, went to get a draft of lukewarm water from the scuttlebutt. But no one stayed over long on these excursions. The breeze had blown up into a gale. The night overhead-was starless and moonless, but every minute the black heaven was split by spurts of lightning, which showed the laboring, dishevelled ship set among great mountains of breaking seas.

The sight would have been bad from a well-manned, powerful steamboat; from the deck of the derelict it approached the terrific. With the seas constantly crashing on board of her, to have left the hatches open would have been, in her semi-waterlogged condition, to court swamping, and after midnight these were battened down, and the men with the shovels worked among the frightened, squeaking rats in the closed-in box of the hold. There were four on board the ship during that terrible night who openly owned to being cowed, and freely bewailed their insanity in ever being lured away from the M'poso. Dayton-Philipps had sufficient self-control to keep his feelings, whatever they were, unstated; but Kettle faced all difficulties with indomitable courage and a smiling face.

"I believe," said Dayton-Philipps to him once when they were taking a spell together at the clanking pumps, "you really glory in finding yourself in this beastly mess."

"I have got to earn out the salvage of this ship somehow," Kettle shouted back to him through the windy darkness, "and I don't much care what work comes between now and when I handle the check."

"You've got a fine confidence. I'm not grumbling, mind, but it seems very unlikely we shall be still afloat to-morrow morning."

"We shall pull through, I tell you."

"Well," said Dayton-Philipps, "I suppose you are a man that's always met with success. I'm not. I've got blundering bad luck all along, and if there's a hole available, I get into it."

Captain Kettle laughed aloud into the storm. "Me!" he cried. "Me in luck! There's not been a man more bashed and kicked by luck between here and twenty years back. I suppose God thought it good for me, and He's kept me down to my bearings in bad luck ever since I first got my captain's ticket. But He's not cruel, Mr. Philipps, and He doesn't push a man beyond the end of his patience. My time's come at last. He's given me something to make up for all the weary waiting. He's sent me this derelict, and He only expects me to do my human best, and then He'll let me get her safely home."

"Good Heavens, Skipper, what are you talking about? Have you seen visions or something?"

"I'm a man, Mr. Philipps, that's always said my prayers regular all through life. I've asked for things, big things, many of them, and I'll not deny they've been mostly denied me. I seemed to know they'd be denied. But in the last week or so there's been a change. I've asked on, just as earnestly as I knew how, and I seemed to hear Him answer. It was hardly a voice, and yet it was like a voice; it appeared to come out of millions of miles of distance; and I heard it say: 'Captain, I do not forget the sparrows, and I have not forgotten you. I have tried you long enough. Presently you shall meet with your reward.'"

Dayton-Philipps stared. Was the man going mad?

"And that's what it is, sir, that makes me sure I shall bring this vessel into some port safely and pocket the salvage."

"Look here, Skipper," said Dayton-Philipps, "you are just fagged to death, and I'm the same. We've been working till our hands are raw as butcher's meat, and we're clean tired out, and we must go below and get a bit of sleep. If the ship swims, so much the better; if she sinks, we can't help it; anyway, we're both of us too beat to work any more. I shall be 'seeing things' myself next."

"Mr. Philipps," said the little sailor gravely, "I know you don't mean anything wrong, so I take no offence. But I'm a man convinced; I've heard the message I told you with my own understanding; and it isn't likely anything you can say will persuade me out of it. I can see you are tired out, as you say, so go you below and get a spell of sleep. But as for me, I've got another twenty hours' wakefulness in me yet, if needs be. This chance has mercifully been sent in my way, as I've said, but naturally it's expected of me that I do my human utmost as well to see it through."

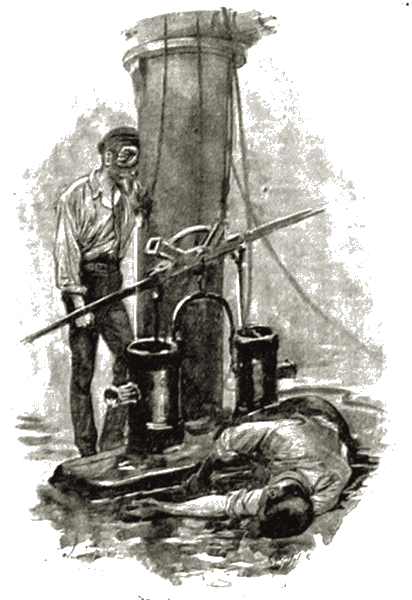

"If you stay on at this heart-breaking work, so do I," said Dayton-Philipps, and toiled gamely on at the pump. There he was still when day broke, sawing up and down like an automaton. But before the sun rose, utter weariness had done its work. His bleeding fingers loosed themselves from the break, his knees failed beneath him, and he fell in an unconscious stupor of sleep on to the wet planking of the deck. For half an hour more Kettle struggled on at the pump, doing double work; but even his flesh and blood had its breaking strain; and at last he could work no more.

He leaned dizzily up against the pump for a minute or so, and then with an effort he pulled his still unconscious companion away and laid him on the dry floor of a deck-house. There was a pannikin of cold stewed tea slung from a hook in there, and half a sea biscuit on one of the bunks. He ate and drank greedily, and then went out again along the streaming decks to work, so far as his single pair of hands could accomplish such a thing, at getting the huge derelict once more in sailing trim.

He leaned dizzily up against the pump.

The shovels meanwhile had been doing their work, and although the list was not entirely gone, the vessel at times (when a sea buttressed her up) floated almost upright. The gale was still blowing, but it had veered to the southward, and on the afternoon of that day Kettle called all hands on deck and got her under way again, and found to his joy that the coal-trimmer had some elementary notion of taking a wheel.

"I rate you as Mate," he said in his gratitude, "and you'll draw salvage pay according to your rank. I was going to make Mr. Philipps my officer, but—"

"Don't apologize," said Dayton-Philipps. "I don't know the name of one string from another, and I'm quite conscious of my deficiency. But just watch me put in another spell at those infernal pumps."

The list was of less account now, and the vessel was once more under command of her canvas. It was the leak which gave them most cause for anxiety. Likely enough it was caused by the mere wrenching away of a couple of rivets. But the steady inpour of water through the holes would soon have made the ship grow unmanageable and founder if it was not constantly attended to. Where the leak was they had not a notion. Probably it was deep down under the cargo of grain, and quite unget-at-able; but anyway it demanded a constant service at the pumps to keep it in check, and this the bone-weary crew were but feebly competent to give. They were running up into the latitude of the Bay, too, and might reasonably expect that "Biscay weather" would not take much from the violence of the existing gale.

However, the dreaded Bay, fickle as usual, saw fit to receive them at first with a smiling face. The gale eased to a plain smiling wind; the sullen black clouds dissolved away into fleckless blue, and a sun came out which peeled their arms and faces as they worked. During the afternoon they rose the brown sails of a Portuguese fishing schooner, and Kettle headed toward her.

Let his crew be as willing as they would, there was no doubt that this murderous work at the pumps could not be kept up for a voyage to England. If he could not get further reinforcements, he would have to take the ship into the nearest foreign port to barely save her from sinking. And then where would be his sighed-for salvage? Woefully thinned, he thought, or more probably whisked away altogether. Captain Kettle had a vast distrust for the shore foreigner over questions of law proceedings and money matters. So he made for the schooner, hove his own vessel to, and signalled that he wished to speak.

A boat was slopped into the water from the schooner's deck, and ten swarthy, ragged Portuguese fishermen crammed into her. A couple pushed at the oars, and they made their way perilously over the deep hill and dale of ocean with that easy familiarity which none but deep-sea fishermen can attain. They worked up alongside, caught a rope which was thrown them, and nimbly climbed over on to the decks.

Two or three of them had a working knowledge of English; their captain spoke it with fluent inaccuracy; and before any of them had gone aft to Kettle, who stood at the wheel, they heard the whole story of the ship being found derelict, and (very naturally) were anxious enough by some means or another to finger a share of the salvage. Even a ragged Portuguese baccalhao maker can have his ambitions for prosperity like other people.

Their leader made his proposal at once. "All right-a, Captain, I see how you want. We take charge now, and take-a you into Ferrol without you being at more trouble."

"Nothing of the kind," said Kettle. "I'm just wanting the loan of two or three hands to give my fellows a spell or two at that pump. We're a bit short-handed, that's all. But otherwise we're quite comfortable. I'll pay A.B.'s wages on Liverpool scale, and that's a lot more than you Dagos give amongst yourselves, and if the men work well I'll throw in a dash besides for 'bacca money.'"

"Ta-ta-ta," said the Portuguese, with a wave of his yellow fist. "It cannot be done, and I will not lend you men. It shall do as I say; we take-a you into Ferroll. Do not fear-a, captain; you shall have money for finding sheep; you shall have some of our salvage."

Dayton-Philipps, who was standing near, and knew the little sailor's views, looked for an outbreak. But Kettle held himself in, and still spoke to the man civilly.

"That's good English you talk," he said. "Do all your crowd understand the language?"

"No," said the fellow, readily enough, "that man does not, nor does him, nor him."

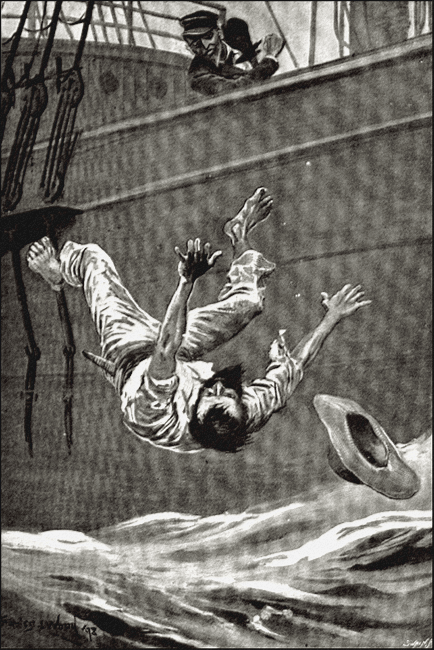

"Right—oh!" said Kettle. "Then, as those three man can't kick up a bobbery at the other end, they've just got to stay here and help work this vessel home. And as for the rest of you filthy, stinking, scale-covered cousins of apes, over the side you go before you're put. Thought you were going to steal my lawful salvage, did you, you crawling, yellow-faced—ah!"

The hot-tempered Portuguese was not a man to stand this tirade (as Kettle anticipated) unmoved. His fingers made a vengeful snatch toward the knife in his belt, but Kettle was ready for this, and caught it first and flung it overboard. Then with a clever heave he picked up the man and sent him after the knife.

He picked up the man and sent him after the knife.

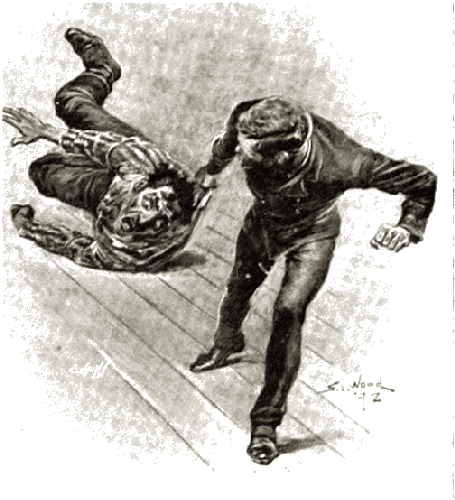

He tripped up one of the Portuguese who couldn't speak English, dragged him to the cabin companion, and toppled him down the ladder. Dayton-Philipps (surprised at himself for abetting such lawlessness) captured a second in like fashion, and the English fireman and coal-trimmer picked up the third and dropped him down an open hatchway on to the grain in the hold beneath.

He tripped up one of the Portuguese

and dragged him to the cabin companion.

But there were six of the fishermen left upon the deck, and these did not look upon the proceedings unmoved. They had been slow to act at first, but when the initial surprise was over, they were blazing with rage and eager to do murder. The Italian and the Sierra Leone nigger ran out of their way on to the forecastle head, and they came on, vainglorious in numbers, and armed with their deadly knives. But the two English roughs, the English gentleman, and the little English sailor, were all of them men well accustomed to take care of their own skins; the belaying pins out of the pinrail seemed to come by instinct into their hands, and not one of them got so much as a scratch.

It was all the affair of a minute. It does not do to let these little impromptu scrimmages simmer over long. In fact, the whole affair was decided in the first rush. The quartette of English went in, despising the "Dagos," and quite intending to clear them off the ship. The invaders were driven overboard by sheer weight of blows and prestige, and the victors leaned on the bulwark puffing and gasping, and watched them swim away to their boat through the clear water below.

"Ruddy Dagos," said the roughs.

"Set of blooming pirates," said Kettle.

But Dayton-Philipps seemed to view the situation from a different point. "I'm rather thinking we are the pirates. How about those three we've got on board? This sort of press-gang work isn't quite approved of nowadays, is it, Skipper?"

"They no speakee English," said Kettle drily. "You might have heard me ask that, sir, before I started to talk to that skipper to make him begin the show. And he did begin it, and that's the great point. If ever you've been in a police court, you'll always find the magistrate ask, 'Who began this trouble?' And when he finds out, that's the man he logs. No, those fishermen won't kick up a bobbery when they get back to happy Portugal again; and as for our own crowd here on board, they ain't likely to talk when they get ashore, and have money due to them."

"Well, I suppose there's reason in that, though I should have my doubts about the stonemason. He comes from Sierra Leone, remember, and they're great on the rights of man there."

"Quite so," said Kettle. "I'll see the stonemason gets packed off to sea again in a stokehold before he has a chance of stirring up the mud ashore. When the black man gets too pampered, he has to be brought low again with a rush, just to make him understand his place."

"I see," said Dayton-Phillips, and then he laughed.

"There's something that tickles you, sir?"

"I was thinking, Skipper, that for a man who believes he's being put in the way of a soft thing by direct guidance from on high, you're using up a tremendous lot of energy to make sure the Almighty's wishes don't miscarry. But still I don't understand much about these matters myself. And at present it occurs to me that I ought to be doing a spell at those infernal pumps, instead of chattering here."

The three captive Portuguese were brought up on deck and were quickly induced by the ordinary persuasive methods of the merchant service officer to forego their sulkiness and turn-to diligently at what work was required of them. But even with this help the heavy ship was still considerably undermanned, and the incessant labor at the pumps fell wearily on all hands. The Bay, true to its fickle nature, changed on them again. The sunshine was swamped by a driving gray mist of rain; the glass started on a steady fall; and before dark, Kettle snugged her down to single topsails, himself laying out on the foot-ropes with the Portuguese, as no others of his crew could manage to scramble aloft with so heavy a sea running.

The night worsened as it went on; the wind piled up steadily in violence; and the sea rose till the sodden vessel rode it with a very babel of shrieks, and groans, and complaining sounds. Toward morning, a terrific squall powdered up against them and hove her down, and a dull rumbling was heard in her bowels to let them know that once more her cargo had shifted.

For the moment, even Kettle thought that this time she was gone for good. She lost her way, and lay down like a log in the water, and the racing seas roared over her as though she had been a half-tide rock. By a miracle no one was washed overboard. But her people hung here and there to eyebolts and ropes, mere nerveless wisps of humanity, incapable under those teeming cataracts of waves to lift so much as a finger to help themselves.

Then to the impact of a heavier gasp of the squall, the topgallant masts went, and the small loss of top-weight seemed momentarily to ease her. Kettle seized upon the moment. He left the trimmer and one of the Portuguese at the wheel, and handed himself along the streaming decks and kicked and cuffed the rest of his crew into activity. He gave his orders, and the ship wore slowly round before the wind, and began to pay away on the other tack.

Great hills of sea deluged her in the process, and her people worked like mermen, half of their time submerged. But by degrees, as the vast rollers hit and shook her with their ponderous impact, she came upright again, and after a little while shook the grain level in her holds, and assumed her normal, angle of heel.

Dayton-Philipps struggled up and, hit Kettle on the shoulder. "How's that, umpire?" he bawled. "My faith, you are a clever, sailor."

Captain Kettle touched his hat. "God bore a hand there, sir," he shouted through the wind. "If I'd tried to straighten her up like that without outside help, every man here would have been fish-chop this minute."

Even Dayton-Philipps, sceptical though he might be, began to think there was "something in it" as the voyage went on. To begin with, the leak stopped. They did not know how it had happened, and they did not very much care. Kettle had his theories. Anyway it stopped. To go on with, although they were buffeted with every kind of evil weather, all their mischances were speedily rectified. In a heavy sea, all their unstable cargo surged about as though it had been liquid, but it always shifted back again before she quite capsized. The mizzen-mast went bodily overboard in one black rain-squall because they were too short-handed to get sail off it in time, but they found that the vessel sailed almost as well as a brig, and was much easier for a weak crew to manage.

All hands got covered with salt-water boils. All hands, with the exception of Kettle—who remained, as usual, neat—grew gaunt, bearded, dirty, and unkempt. They were grimed with sea-salt, they were flayed with violent suns; but by dint of hard schooling they were becoming handy sailormen, all of them, and even the negro stonemason learned to obey an order without first thinking over its justice till he earned a premonitory hiding.

In the throat of the English Channel a blundering steamship did her best to run them down, and actually rasped sides with the sailing-vessel as she tore past into the night; but nobody made an attempt to jump for safety on to her decks, nobody even took the trouble to swear at her with any thing like heartfelt profanity.

"It's a blooming Flying Dutchman we're on," said the coal-trimmer who acted as mate. "There's no killing the old beast. Only hope she gets us ashore somehow, and doesn't stay fooling about at sea forever just to get into risks. I want to get off her. She's too blooming lucky to be quite wholesome somehow."

Kettle had intended to make a Channel port, but a gale hustled him north round Land's End, "and you see," he said to Dayton-Philipps, "what I get for not being sufficiently trustful. The old girl's papers are made out to Cardiff, and here we are pushed round into the Bristol Channel. By James! look, there's a tug making up to us. Thing like that makes you feel homey, doesn't it, sir?"

The little spattering tug wheeled up within hail, tossing like a cork on the brown waves of the estuary, and the skipper in the green pulpit between the paddle-boxes waved a hand cheerily.

"Seem to have found some dirty weather, Captain," he bawled. "Want a pull into Cardiff or Newport?"

"Cardiff. What price?"

"Say £100."

"I wasn't asking to buy the tug. You're putting a pretty fancy figure on her for that new lick of paint you've got on your rails."

"I'll take £80."

"Oh, I can sail her in myself if you're going to be funny. She's as handy as a pilot-boat, brig rigged like this, and my crew know her fine. I'll give you £20 into Cardiff, and you're to dock me for that."

"Twenty wicked people. Now look here, Captain, you don't look very prosperous with that vessel of yours, and will probably have the sack from owners for mishandling her when you get ashore, and I don't want to embitter your remaining years in the workus, so I'll pull you in for fifty quid."

"£20, old bottle nose."

"Come now, Captain, thirty. I'm not here for sport. I've got to make my living."

"My man," said Kettle, "I'll meet you and make it £25, and I'll see you in Aden before I give a penny more. You can take that, or sheer off."

"Throw us your blooming rope," said the tug skipper.

"There, sir," said Kettle sotto voce to Dayton-Philipps, "you see the marvellousness of it? God has stood by me to the very end. I've saved at least £10 over that towage, and, by James! I've seen times when a ship mauled about like this would have been bled for four times the amount before a tug would pluck her in."

"Then we are out of the wood now?"

"We'll get the canvas off her, and then you can go below and shave. You can sleep in a shore bed this night, if you choose, sir, and to-morrow we'll see about fingering the salvage. There'll be no trouble there now; we shall just have to ask for a check and Lloyds will pay it, and then you and the hands will take your share, and I—by James! Mr. Philipps, I shall be a rich man over this business. I shouldn't be a bit surprised but what I finger a snug £500 as my share. Oh, sir, Heaven's been very good to me over this, and I know it, and I'm grateful. My wife will be grateful too. I wish you could come to our chapel some day and see her."

"You deserve your luck, Captain, if ever a man did in this world, and, by Jove! we'll celebrate it. We've been living on pig's food for long enough. We'll find the best hotel in Cardiff, and we'll get the best dinner the chef there can produce . I want you to be my guest at that."

"You deserve your luck, Captain."

"I must ask you to excuse me," said Kettle. "I've received a good deal just lately, and I'm thankful, and I want to say so. If you don't mind, I'd rather say it alone."

"I understand, Skipper. You're a heap better man than I am, and if you don't mind, I'd like to shake hands with you. Thanks. We may not meet again, but I shall never forget you and what we've seen on this murderous old wreck of a ship. Hullo, there's Cardiff not twenty minutes ahead. Well, I must go below and clean up after you've docked her."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.