RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

A Master of Fortune, 1898,

with "The Wire-Milkers"

"LOOK here," said Sheriff, "you compel me to be brutal, but the fact is, they've had enough of you here in Lagos. So far as I can see, you've only got the choice of two things. You can have a free passage home to England as a Distressed Seaman by the next steamer, and you know what that means. The steamer gets paid a shilling a day, and grubs and berths you accordingly, and you earn your 'bacca money by bumming around the galley and helping the cook peel spuds. Or else, if you don't like that, you can do the sensible thing, and step into the billet I offer you."

"By James!" said Kettle, "who's going to turn me out of Lagos; tell me that, sir?"

"Don't get wrathful with me. I'm only telling you what you'll find out to be the square truth if you stay on long enough. The authorities here will be equal to handling you if you try to buck against them."

"But, sir, they have no right to touch me. This isn't French territory, or German, or any of those clamped-down places. The town's as English as Liverpool, and I'm a respectable man."

"The trouble of it is," said Sheriff drily, "they say you are not. There are a limited number of white men here in Lagos—perhaps two hundred all told—and their businesses and sources of income are all more or less visible to the naked eye. Yours aren't. In the language of the—Dr—well—the police court, you've no visible means of subsistence, and yet you always turn out neat, and spruce, and tidy; you've always got tobacco; and apparently you must have meals now and again, though I can't say you've got particularly fat on them."

"I've never been a rich man, sir. I've never earned high wages—only once as much as fifteen pounds a month—and there's the missis and the family to provide for; and, as a consequence, I've never had much to spend on myself. It would surprise a gentleman who's been wealthy like you, Mr. Sheriff, to see the way I can make half-a-crown spin out."

"It surprises me to see how you've made nothing at all spin out," said Sheriff; "and as for the Lagos authorities I was speaking about, it's done more; it's made them suspicious. Hang it, man, be reasonable; you must see they are bound to be suspicious."

Sheriff spread his hands helplessly. "That's no kind of answer," he said. "They won't let you continue to stay here in Lagos on an explanation like that. Come now, Kettle, be sensible: put yourself in the authorities' place. They've got a town to administer—a big town—that not thirty years ago was the most murderous, fanatical, rowdy dwelling of slave-traders on the West Coast of Africa. To-day, by dint of careful shepherding, they've reduced it to a city of quiet respectability, with a smaller crime rate than Birmingham; and in fact made it into a model town suitable for a story-book. You don't see the Government much, but you bet it's there, and you bet it isn't asleep. You can bet also that the nigger people here haven't quite forgotten the old days, and would like to be up to a bit of mischief every now and again, just for old association's sake, which of course the Government is quite aware of.

"Now there's nothing that can stir up niggers into ructions against a white man's government better than a white man, as has been proved tons of times already, and here are you already on the carpet quite equal to the job. I don't say you are up to mischief, nor does the Government, but you must see for yourself that they'd be fools if they didn't play for safety and ship you off out of harm's way."

"I must admit," said Kettle ruefully, "that there's sense in what you say, sir."

"Are you going to give a free and open explanation of your means of employment here in Lagos, and earn the right to stay on openly, or are you going to still stick to the mysterious?"

The little sailor frowned. "No, sir," he said; "as I told you before, I have my pride."

"Very-well, then. Now, are you going to be the Distressed Seaman, and be jeered at all the run home as you cadge round for your 'baccy money, or are you going to do the sensible thing, and step into this billet I've put in your way?"

"You corner me."

"I'm glad to hear it, and let me tell you it hasn't been for want of trying. Man, if I hadn't liked you, I would not have taken all this trouble to put a soft thing ready to your hand."

"I believe you want service out of me in return, sir," said Kettle stiffly.

Sheriff laughed. "You aren't the handiest man in the world to get on with, and if I hadn't been an easy-tempered chap I should have bidden you go to the deuce long enough ago. Of course, I want something out of you. A man who has just lost a fortune, and who is down on his luck like I am, can't afford to go in for pure philanthropy without any possible return. But, at the same time, I'm finding you a job at fifty pound a month with a fortnight's wages paid in advance, and I think you might be decently grateful. By your own telling, you never earned so much as four sovereigns a week before."

"The wages were quite to my taste from the beginning, sir; don't think me ungrateful there. But what I didn't like was going to sea without knowing beforehand what I was expected to do. I didn't like it at first, and I refused the job then; and if I take it now, being, as you say, cornered, you're not to understand that it's grown any the tastier to me."

"We shouldn't pay a skipper a big figure like that," said Sheriff drily, "if we didn't want something a bit more than, the ordinary out of him. You may take it you are getting fifteen pounds a month as standard pay, and the extra thirty-five for condescending to sail with sealed orders. But what I told you at first I repeat now: I've got a partner standing in with me over this business, and as he insists on the whole thing being kept absolutely dark till we're away at sea, I've no choice but to observe the conditions of partnership."

Some thirty minutes later than this, Mr. Sheriff got out of his 'rickshaw on the Marina and went into an office and inquired for Mr. White. One of the colored clerks (who, to do credit to his English education, affected to be utterly prostrated by the heat) replied with languor that Mr. White was upstairs; upon which Sheriff, mopping himself with a handkerchief, went up briskly.

White, a gorgeously handsome young Hebrew, read success from his face at once. "I can see you've hooked your man," said he. "That's good business; we couldn't have got another as good anywhere. Have a cocktail?"

"Don't mind if I do. It's been tough work persuading him. He's such a suspicious, conscientious little beggar. Shout for your boy to bring the cocktail, and when we're alone, I'll tell you about it."

"I'll fix up your drink myself, old man. Where's the swizzle- stick? Oh, here, behind the Angostura bottle. And there's a fresh lime for you—got a basket of them in this morning. Now you yarn whilst I play barmaid."

Mr. Sheriff tucked his feet on the arms of a long-chair and picked up a fan. He sketched in the account of his embassage with humorous phrase.

The Hebrew had been liberal with his cocktail. He said himself that he made them so beautifully that no one could resist a second; and so, with a sigh of gusto, Sheriff gulped down number two and put the glass on the floor. "No," he said; "no more. They're heavenly, I'll grant, but no more. We shall want very clear heads for what's in front of us, and I'm not going to fuddle mine for a commencement. I can tell you we have been very nearly wrecked already. It was only by the skin of my teeth I managed to collar Master Kettle. I only got him because I happened to know something about him."

"Did you threaten to get him into trouble over it? What's he done?"

"Oh, nothing of that sort. But the man's got the pride of an emperor, and it came to my knowledge he'd been making a living out of fishing in the lagoon, and I worked on that. Look out of that window; it's a bit glary with the sun full on, but do you see those rows of stakes the nets are made fast on? Well, one of those belongs to Captain Owen Kettle, and he works there after dark like a native, and dressed as one. You know he's been so long living naked up in the bush that his hide's nearly black, and he can speak all the nigger dialects. But I guessed he'd never own up that he'd come so low as to compete with nigger fishermen, and I fixed things so that he thought he'd have to tell white Lagos what was his trade, or clear out of the colony one-time. It was quite a neat bit of diplomacy."

"You have got a tongue in you," said White.

"When a man's as broke as I am, and as desperate, he does his best in talk to get what he wants. But look here, Mr. White, now we've got Kettle, I want to be off and see the thing over and finished as soon as possible. It's the first time I've been hard enough pushed to meddle with this kind of racket, and I can't say I find it so savory that I'm keen on lingering over it."

The Jew shrugged his shoulders. "We are going for money," he said. "Money is always hard to get, my boy, but it's nice, very nice, when you have it."

The Jew shrugged his shoulders.

Keen though Sheriff was to get this venture put to the trial, brimming with energy though he might be, it was quite out of the question that a start could be made at once. A small steamer they had already secured on charter, but she had to be manned, coaled, and provisioned, and all these things are not carried out as quickly in Lagos as they would be in Liverpool, even though there was a Kettle in command to do the driving. And, moreover, there were cablegrams to be sent, in tedious cypher, to London and elsewhere, to make the arrangements on which the success of the scheme would depend.

The Jew was the prime mover in all this cabling. He had abundance of money in his pocket, and he spent it lavishly, and he practically lived in the neighborhood of the telegraph office. He was as affable as could be; he drank cocktails and champagne with the telegraph staff whenever they were offered; but over the nature of his business he was as close as an oyster.

A breath of suspicion against the scheme would wreck it in an instant, and, as there was money to be made by carrying it through, the easy, lively, boisterous Mr. White was probably just then as cautious a man as there was in Africa.

But preparations were finished at last, and one morning, when the tide served, the little steamer cast off from her wharf below the Marina, and steered for the pass at the further side of the lagoon.

The bar was easy, and let her through with scarcely so much as a bit of spray to moisten the dry deck planks, and Sheriff pointed to the masts of a branch-boat which had struck the sand a week before, and had beaten her bottom out and sunk in ten minutes, and from these he drew good omens about this venture, and at the same time prettily complimented Kettle on his navigation.

But Kettle refused to be drawn into friendliness. He coldly commented that luck and not skill was at the bottom of these matters, and that if the bar had shifted, he himself could have put this steamer on the ground as handily as the other man had piled up the branch-boat. He refused to come below and have a drink, saying that his place was on the bridge till he learned from observation that either of the two mates was a man to be trusted. And, finally, he inquired, with acid formality, as to whether his employers wished the steamer brought to an anchor in the roads, or whether they would condescend to give him a course to steer.

Sheriff bade him curtly enough to "keep her going to the s'uth'ard," and then drew away his partner into the stifling little chart-house. "Now," he said, "you see how it is. Our little admiral up there is standing on his temper, and if he doesn't hear the plan of campaign, he's quite equal to making himself nasty."

"I don't mind telling him some, but I'm hanged if I'm going to tell him all. There are too many in the secret already, what with you and the two in London; and as I keep on telling you, if one whiff of a suspicion gets abroad, the whole thing's busted, and a trap will be set that you and I will be caught in for a certainty."

"Poof! We're at sea now, and no one can gossip beyond the walls of the ship. Besides Kettle is far too staunch to talk. He's the sort of man who can be as mum as the grave when he chooses. But if you persist in refusing to trust him, well, I tell you that the thought of what he may be up to makes me frightened."

"Now look here, my boy," said White, "you force me to remind you that I'm senior partner here, and to repeat that what I say on this matter's going to be done. I flatly refuse to trust this Kettle with the whole yarn. We've hired him at an exorbitant fee—bought him body and soul, in fact, as I've no doubt he very well understands—and to my mind he's engaged to do exactly as he's told, without asking questions. But as you seem set on it, I'll meet you here; he may be told a bit. Fetch him down."

But as Kettle refused to come below, on the chilly plea of business, the partner went out under the awnings of the upper bridge, where the handsome White, with boisterous, open-hearted friendliness, did his best to hustle the little sailor into quick good humor.

"Don't blame me, Skipper, or Sheriff here either, for the matter of that, for making all this mystery. We're just a couple of paid agents, and the bigger men at the back insisted that we should keep our mouths shut till the right time. There's nothing wrong with this caution, I'm sure you'll be the first to say. You see they couldn't tell from that distance what sort of man we should be able to pick up at Lagos. I guess they never so much as dreamed that we'd have the luck to persuade a chap like you to join."

"You are very polite, sir," said Kettle formally.

"Not a bit of it. I'm not the sort of boy to chuck civility away on an incompetent man. Now look here, Captain. We're on for making a big pile in a very short time, and you can stand in to finger your share if you'll, only take your whack of the work."

"There's no man living more capable of hard work than me, sir, and no man keener to make a competence. I've got a wife that I'd like to see a lot better off than I've ever been able to make her so far."

"I'm sure Mrs. Kettle deserves affluence, and please the pigs she shall have it."

"But it isn't every sovereign that might be put in her way," said the sailor meaningly, "that Mrs. Kettle would care to use."

"I guess I find every sovereign that comes to my fingers contains twenty useful shillings."

"I will take your word for it, sir. Mrs. Kettle prefers to know that the few she handles are cleanly come by."

Mr. White gritted his handsome teeth, shrugged his shoulders, and made as if he intended to go down off the bridge. But Sheriff stopped him. "We'd better have it out," Sheriff suggested; "as well now as later."

"Put it in your own words, then. I don't seem able to get started. You," he added significantly, "know as well as I do what to say."

"Very well. Now, look here, Kettle. This mystery game has gone on long enough, and you've got to be put on the ground floor, like the rest of us. Did you ever dabble in stocks?"

"No, sir."

"But you know what they are?"

"I've heard the minister I sit under ashore give his opinion from the pulpit on the Stock Exchange, and those who do business there. The minister of our chapel, sir, is a man I always agree with."

This was sufficiently unpromising, but Sheriff went doggedly on. "I see your way of looking at it: the whole crowd of stock operators are a gang of thieves that no decent man would care to touch?"

"That's much my notion."

"And they are quite unworthy of protection?"

"They can rob one another to their heart's content for all I care."

Sheriff smiled grimly. "That's what I wanted to hear you say, Captain. This cruise we are on now is not exactly a pleasure trip."

"I guessed that, of course, from the pay that was offered."

"What we are after is this: the Cape to England telegraph cable stops at several places on the road, and we want to get hold of one of the stations and work it for our own purposes for an hour or so. If we can do that, our partners in London will bring off a speculation in South African shares that will set the whole lot of us up for life."

"And who pays the piper? I mean where will the money for your profit come from?"

White was quicker than Sheriff to grasp the situation. "From inside the four walls of the Stock Exchange. S'elp me, Captain, you needn't pity them. There are lots of men there, my friends too, who would have played the game themselves if they had been sharp enough to think of it. We have to be pretty keen in the speculation business if we want to make money out of it."

Captain Kettle buttoned his coat, and stepped to the further end of the bridge with an elaborate show of disgust. "You are on the Stock Exchange yourself, sir?"

"Er—connected with it, Captain."

"I can quite understand our minister's opinion of stock gamblers now. Perhaps some day you may hear it for yourself. He's a great man for visiting—"

"By gad!" said White, "you insolent little blackguard, you dare to speak to me like that!"

"I use what words I choose," said Kettle, truculently. "I'd have said the same to your late King Solomon if I hadn't liked his ways; but if I was pocketing his pay, I should have carried out his orders all the same." He bent down to the voice hatch, and gave a bearing to the black quartermaster in the wheel-house below, and the little steamer, which had by this time left behind her the vessels transhipping cargo in the roads, canted off on a new course to the southward.

"I use what words I choose," said Kettle, truculently.

"Hullo," said Sheriff, "what's that mean? Where are you off to now?"

Kettle mentioned the name of a lonely island standing by itself in the Atlantic.

But Sheriff and the Jew were visibly startled. Mr. Sheriff mopped at a very damp forehead with his pocket handkerchief. "Have you heard anything then?" he asked, "or did you just guess?"

"I heard nothing before, or I should not have signed on for this trip, sir. But having come so far I'm going to earn out my pay. What's done will not be on my conscience. The shipmaster's blameless in these matters; it's the owner who drives him that earns his punishment in the hereafter; and that's sound theology."

"But how did you guess, man, how did you know where we were bound?"

"A shipmaster knows cable stations as well as he knows owners' agents' offices ashore. Any fool who had been told your game would have put his finger on that island at once. That's the loneliest place where the cable goes ashore all up and down the coast, and it isn't British, and what more could you want?"

With these meagre assurances, Messieurs Sheriff and White had to be content, as no others were forthcoming. Captain Kettle refused to be drawn into further talk upon the subject, and the pair went below to the stuffy little cabin more than a trifle disconsolate. "Well, here's the man you talked so big about," said White, bitterly. "As soon as we get out at sea, he shows himself in his true colors. Why, he's a blooming Methodist. But if he sells us when it comes to the point, and there's a chance of my getting nabbed, by gad I'll murder him like I would a rat."

"By gad I'll murder him like I would a rat."

"If he offers a scrimmage," said Sheriff, "you take my tip, and clear out. He's a regular glutton for a fight; I know he's armed; and he could shoot the buttons off your coat at twenty yards. No, Mr. White; make the best or the worst of Captain Kettle as you choose, but don't come to fisticuffs with him, or as sure as you are living now, you'll finish out on the under side then. And mind, I'm not talking by guess-work. I know."

"I shall not stick at much if this show's spoiled. Why, the money was as good as in our pockets, if he hadn't cut up awkward."

"Don't throw up the sponge till some one else does it for you. Look here, I know this man Kettle a lot better than you do. He wants the pay very badly. And when it comes to sticking up the cable station, you'll see him do the work of any ten like us. I tell you, he's a regular demon when it comes to a scuffle."

It was in this attitude, then, that the three principal members of the little steamer's complement voyaged down over those warm tropical seas which lay between Lagos and the isle of their hopes and fears. Two of them kept together, and perfected the detail of their plans for use in every contingency; but the other kept himself icily apart, and for an occupation, when the business of the ship did not require his eye, wrapped himself up in the labor of literary production. He even refused to partake of meals at the same table with his employers.

The island first appeared to them as a huddle of mountains sprouting out of the sea, which grew green as they came more near, and which finally showed great masses of foliage growing to the crown of the splintered heights, with a surf frilling the bays and capes at their foot. There was a town in the hug of one of these bays, and toward it the little steamer rolled as though she had been an ordinary legitimate trader. She brought up to an anchor in the jaws of the bay, half-way between the lighthouse and the rectangular white building on the further beach, and after due delay, a negro doctor, pulled up by a surf-boat full of other negroes, came off and gave her pratique.

The rectangular white building, standing in the sea breeze by itself away from the town beyond, was the cable station, but for the present they faced it with their backs. Kettle had seen it before; the other two acted as though it were the last thing to trouble their minds. There was no going ashore for any of them yet; indeed, the less they advertised their personal identity, the more chance there was of getting off untraced afterward.

Night fell with such suddenness that one could almost have imagined the sun was permanently extinguished. Round the rim of the bay lights began to kindle, and presently (when the wind came off the land) strains of music floated out to them.

"Some saint's day," Sheriff commented.

"St. Agatha's," said Kettle with a sigh.

"Hello, Kettle. I thought you were a straight-laced chapel goer. What have you to do with saints and their days?"

"I was told that one once, sir, and I can't help remembering it. You see the date is February 5th, and that's my eldest youngster's birthday."

Sheriff swore. "I wish you'd drop that sort of sentimental bosh, Skipper; especially now. I want to get this business over first, and then, when I go back with plenty in my pocket, I can begin to think of family pleasures and cares again. Come now, have you thought out what we can do with the steamer after we've finished our job here?"

"Run up with the coast and sink her, and then go ashore in the surf-boat at some place where the cable doesn't call, and leave that as soon as possible for somewhere else."

"It will be a big saving of necks," said Kettle drily. "Why sir, you've been a steamer-owner in your time, and you must know how we're fixed. You've given up your papers here, and you're known. You can't go into another port in the whole wide world without papers, and as far as forging a new set, why that's a thing that hasn't been done this thirty years outside a story-book."

Mr. White came up to hear. "I don't see that," he said.

"You fellows don't understand everything in Jerusalem," said Kettle, with a cheerful insult, and walked away. Captain Kettle regarded Sheriff as a gull, and pitied him accordingly; but White he recognized as principal knave, and disliked him accordingly.

But when the start was made for the raid, some hour and a half before the dawn, Kettle was not backward in fulfilling his paid- for task. Himself he saw a surf-boat lowered into the water and manned by black Krooboy paddlers; himself he saw his two employers down on the thwarts, and then followed them; and himself he sat beside the head-man who straddled in the stern sheets at the steering oar, and gave him minute directions.

The boat was avoiding the bay altogether. She was making for the strip of sand in front of the cable station, and except when she was shouldered up on the back of a roller, the goal was out of sight all the time.

"There's a rare swell running, and it's a mighty bad beach to- night," Kettle commented. "I hope you gentlemen can swim, for the odds are you'll have to do it inside the next ten minutes."

"If we are spilt getting ashore," said White, "how do you say we'll get off again?"

"The Lord knows," said Kettle.

"Well, you're a cheerful companion, anyway."

"I wasn't paid for a yacht skippering job and asked to say nice things which weren't true. But if you don't fancy the prospect, go back and try a trade that's less risky. You mayn't like honest work, but it strikes me this kind of contract's out your weight anyway."

The Jew looked as if he would like to let loose his tongue, and perhaps handle a weapon, but his motto was "business first," and he could not afford to have an open fracas with Kettle then. So he swallowed his resentment, and said, "Get on," and clung dizzily on to his thwart.

As each roller passed tinder her, the surf-boat swooped higher and higher, and the laboring paddles seemed to give her less and less momentum. The head-man strained at the steering oar. The Krooboys had hard work to keep their perches on the gunwale.

At last the head-man shouted, and the paddles ceased. They were waiting for a smooth. Roller after roller swept under them, and the boat rode them dizzily, but kept her place just beyond the outer edge of the surf. From over his shoulder, the head-man watched the charging seas with animal intentness. Then with a sudden shriek he gave the word, and the paddles stabbed the water into spray. The heavy boat rushed forward again, and a great towering sea rushed after her. It reared her up, stern uppermost, and passed, leaving her half swamped by its foaming passage; and then came another sea, and the boat broached to and spilt. The Krooboys jumped like black frogs from either gunwale, and Kettle jumped also, and made his way easily to the sand, being used to this experience. But Sheriff was pulled on to the beach with difficulty, and the Jew was hauled there in a state verging on the unconscious. He looked at the fearsome surf, and shuddered openly. "How shall we get off again?" he gasped.

"More swimming," said Kettle tersely. "And perhaps not manage it at all. You'd better give up the game, and go off decently to- morrow morning from the Custom House wharf."

But Mr. White, whatever might be the list of his failings, was certainly possessed of dogged pluck, and as he had got that far with his enterprise, did not intend to desert it. He got rid of the sea-water that was within him, and resolutely led the way to the cable station, which loomed square and solid through the dusk. Sheriff followed, and Captain Kettle, with his hands in his pockets, brought up the rear. The Krooboys, according to their orders, stayed on the beach, brought in the boat, collected her furniture, and got all ready for relaunching.

White seemed to know the way as if he had been there before. He went up to the building, entered through an open door, and strode quietly in his rubber-soled shoes along a dark passage. At the end was a room in partial darkness, and a man who watched a spot of light which darted hither and back, and between whiles wrote upon paper. To him White went up, and clapped a cold revolver muzzle against the nape of his neck.

"Now," he said, "I want the loan of your instrument for about an hour. If you resist, you'll be shot. The noise of the shot will bring out the other men on the station, and they'll be killed also. There are plenty of us here, and we are well armed, and we intend to have our own way. If you are not anything short of a fool, you'll go and sit on that chair, and keep quiet till you're given leave to talk."

"I don't think I'll argue it with you," said the operator coolly. He got up and sat where he was told, and Kettle, according to arrangement, stood guard over him. "I suppose you malefactors know," he added, "that there are certain pains and penalties attached to this sort of amusement, and that you are bound to get caught quite soon, whether you shoot me or let me go?"

Nobody answered him. White had sat down at the instrument table, and was tapping out messages like a man well accustomed to the work.

"Of course with those black mask things over your faces I couldn't recognize you again, even if I was put in the box; but, my good chaps, your steamer's known, there's no getting over that. Much better clear out before any mischief's done, and own up you've made a mistake."

White turned on the man with a sudden fury. "If you don't keep your silly mouth shut, I'll have you throttled," he threatened, and after that the only noise that broke the silence was the tap-taptap-tap-tapping of the telegraph instrument.

Only two men in that darkened room knew what message was being dispatched, and these were White and the dispossessed operator. The one worked with cool, steady industry, and the other listened with strained intentness. Sheriff was outside the door keeping guard on the rest of the house. But Kettle, from his station behind the operator's chair, listened with a strange disquietude. He had been told that the object of the raid was to arrange a stock exchange robbery, and to this he had tacitly agreed. According to his narrow creed (as gathered from the South Shields chapel) none but rogues and thieves dealt in stocks and shares, and if these chose to rob one another, an honest man might well look on non-interferent. But what guarantee had he that this robbery was not planned to draw plunder from the outside public as well? The pledged word of Mr. White. And that was worth? He smiled disdainfully when he thought of the slenderness of its value.

Tap-taptap-tap-tap-taptap, said the tantalizing instrument, going steadily on with its hidden speech.

The stifling heat of the room seemed to get more oppressive. The mystery of the thing beat against Kettle's brain.

Of course he could not read the deposed operator's thoughts, though he could see easily that the man was reading the messages which White was so glibly sending off. But it was clear that the man's agitation was growing; growing, too, out of all proportion to the coolness he had shown when his room was first invaded. At last an exclamation was forced from him, almost, as it seemed, involuntarily. "Oh, you ghastly scoundrel," he murmured, and on that Kettle spoke. He could not stand the mystery any longer.

"Tell me," he said, "exactly what message that man's sending."

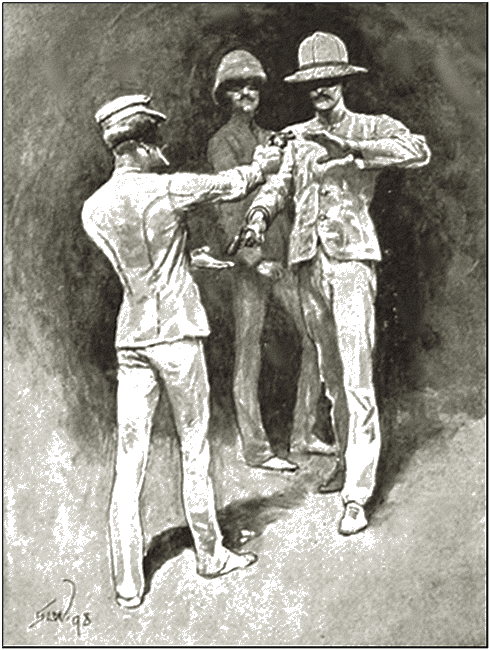

"But I forbid you to do any such thing," said White, and reached for his revolver. But before his fingers touched it, he looked up and saw Kettle's weapon covering him.

"You put that down," came the crisp order, and White obeyed it nervously enough.

"And now go and stand in the middle of the room till I give you leave to shift."

White did this also. He grasped the fact that Captain Kettle was not in a mood to be trifled with.

"Now, Mr. Telegraph Clerk, as you understand this tack-hammer language, and as I could see you've been following all the messages that's been sent, just tell me the whole lot of it, please, as near as you can remember."

"He called up London first, and gave what sounded like a registered address, and sent the word 'coruscate.' That's probably code; anyway I don't know what it meant. Then he called the Cape, and sent a message to the Governor. He hadn't got to the end, and there was no signature, but it was evidently intended to make them believe that it was sent from the Colonial Office at home."

"Well," said Kettle, "what was the message?"

"Good Lord, man, he's directing the Governor to declare war on the Transvaal. You know there's been trouble with them lately, and they'll believe that it comes from the right place. If this is some stock-jobbing plant—"

"It is."

"Then, by heavens, it'll be carried through unless you let me stop it at once. The thing's plausible enough—"

But here White recovered from his temporary scare, and cut in with a fine show of authority. "S'help me, Kettle, you're making a pretty mess of things. You make me knock off in the middle of a message, and they'll not know what's up at the other end if I don't go on. Look at that mirror."

"I see the spot of light winking about."

"That's the operator at the next station calling me."

"But is it true what this gentleman's been telling me?"

"I suppose it is, more or less. But what of that? What did you lose your temper for like this? You knew quite well what we came here for."

"I knew you came to steal money from stockbrokers. I knew nothing about going to try and run my country in for a war."

"Poof, that's nothing. The war would not hurt you and me. Besides, it must go on now. I've cabled my partner in London to be a bear in Kaffirs for all he's worth. We must smash all the instruments here so they can't contradict the news, and then be off."

"Your partner can be a bear or any other kind of beast, in any sort of niggers he chooses, but I'm not going to let you run England into war at any price."

"Pah, my good man, what does that matter to you? What's England ever done for you?"

"I live there," said Kettle, "when I'm at home, and as I've lived everywhere else in the world, I'm naturally a bit more fond of the old shop than if I'd never gone away from her beach. No, Mr. White, England's never done anything special for me that I could, so to speak, put my finger on, but—ah would you!"

White, in desperation, had made a grab at the revolver lying on the instrument table, but with a quick rush Kettle possessed himself of it, and Mr. White found himself again looking down the muzzle of Captain Kettle's weapon.

Mr. White found himself again looking down

the muzzle of Captain Kettle's weapon.

But a moment later the aim was changed. Sheriff, hearing the whispered talk, had come in through the doorway to see what it was about, and promptly found himself favored in his turn.

"Shift your pistol to muzzle end, and bring it here."

Sheriff obeyed the order promptly. He had seen enough of Captain Kettle's usefulness as a marksman not to dispute his wishes.

"Did you know that we came here to stir up a war between our folks at home and the Transvaal?"

"I suppose so."

"And smash up the telegraph instruments afterward, so that it could not be contradicted till it was well under way?"

"That would have been necessary."

"And you remember what you told me on that steamboat? Oh! you liar!" said Kettle, and Sheriff winced.

"I'm so beastly hard up," he said.

Captain Kettle might have commented on his own poverty, but he did not do this. Instead, he said: "Now we'll go back to the ship, and of course you'll have to scuttle her just as if you'd brought off your game here successfully. Run England in for a bloody war, would you, just for some filthy money? By James! no. Come, march. And you, Mr. Telegraph Clerk, get under weigh with that deaf and dumb alphabet of yours, and ring up the Cape, and tell them what's been sent is all a joke, and there's to be no war at all."

"I'll do that, you may lay your heart on it," said the operator. "But Mr. I-don't-know-what-your-name-is, look here. Hadn't you better stay? I'll see things are put all right. But if you go off with those two sharks, it might be dangerous."

"Thank you, kindly, sir," said Kettle; "but I'm a man that's been accustomed to look after myself all the world over, and I'm not likely to get hurt now. Those two may be sharks, as you say, but I'm not altogether a simple little lamb myself."

"I shall be a bit uneasy for you. You're a good soul whoever you may be, and I'd like to do something for you if I could."

"Then, sir," said Kettle, "just keep quiet, here, and get on with your work contradicting that wire, and don't send for any of those little Portuguese soldiers with guns to see us off. It's a bad beach, and we mayn't get off first try, and if they started to annoy us whilst we were at work, I might have to shoot some of them, which would be a trouble."

"I'll see to that," said the operator. "We'll just shake hands if you don't mind, before you go. There's more man to the cubic inch about you than in any other fellow I've come across for a long time. I've no club at home now, or I'd ask you to look me up. But I dare say we shall meet again some time. So long."

"Good-by, sir," said Kettle, and shook the operator by the hand. Then he turned, and drove the other two raiders before him out of the house, and down to the beach, and, with the Krooboys, applied himself to launching the surf-boat through the breakers.

"Good-by, sir," said Kettle

"Run the old shop into a war, would you?" he soliloquized to two very limp, unconscious figures, as the Krooboys got the surf-boat afloat after the third upset. "It's queer what some men will do for money." And then, a minute later, he muttered to himself: "By James! look at that dawn coming up behind the island there; yellow as a lemon. Now, that is fine. I can make a bit of poetry out of that."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.