RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Pearson's, December 1900, with "The Purser's Revenge"

The Derelict, Lewis, Scribner & Co., New York & London, 1901,

with "The Greatest Pianist" (originally "The Purser's Revenge")

The Derelict, Lewis, Scribner & Co., New York & London, 1901,

with "The Greatest Pianist" (originally "The Purser's Revenge")

"NEVER HEARD of him before, sir," said Mr. Horrocks, the Purser.

"Why, he's the greatest musician in the world," said Captain Clayton.

"Did he tell you so himself?" asked Mr. Horrocks, "or did you read that on one of his handbills?"

"Pooh, Janocky is not the man to advertise."

"Then he's the first theatrical I ever came across who didn't."

"I tell you the man's not a theatrical, Horrocks. He's a pianist, and the Leeds is honoured in having him for a passenger."

"Never knew any pro. yet bring either honour or profit to any boat," said the Purser stubbornly.

Mr. Horrocks was a fellow of infinite tact to passengers, but deep within his rotund exterior, and kept there solely for private consumption, was an assortment of very violent prejudices. And of all his strong dislikes, actors, actresses, musicians, and all those who made a livelihood by tickling the ears of the public held an easy first place.

Captain Clayton, however, who had married a wife from the stage, naturally looked upon the class from a different standpoint. He said rather sharply that they must take care that Janocky was given a good room.

"Certainly, sir. Of course, if you think a good deal of attention ought to be given him, the greatest compliment would be to let him have your room." Mr. Horrocks knew quite well that the Captain had let his own room to a Californian millionaire at an exorbitant fee, and would, as usual, take up his quarters in the chart-house; and, moreover. Captain Clayton was quite aware that his stout purser knew this.

"That's not convenient. He must have one of the best of the ordinary passengers' rooms."

"He shall, sir, you may depend upon me. I will see from his ticket what passage money was paid, and he shall have the best we ever do for the price."

Which, being interpreted, meant that Mr. Horrocks would give the pianist exactly the type of cabin he paid for, and no more. Indeed, if he had only paid for a single berth, the Purser was firmly determined that he should have a stable companion. The ship would be full enough to arrange this easily.

Captain Clayton knew that the Purser was practically supreme in these matters, and did not intend to give way, and made a mental note that Mr. Horrocks had not given up his habit of making repayment for value received. Some little while before, he had stopped the Purser from pocketing a commission which that worthy man considered a lawful perquisite. He now understood why at times it is advisable that shipmasters should wink at some of the habits of pursers.

"Of course, you'd like to have this Mr. John-what's his-name at your table, sir?"

"Yes," said Clayton, and sharply changed the conversation.

Now Mr. Horrocks explained his distaste for theatrical people as due to several things. As he viewed them, their excessive vanity gave him nausea; they always wanted better rooms than they were entitled to, and paid the lowest possible rates of fare; they sponged on the other passengers, and were always on the look-out to create scandals. And finally, he was bound to be civil to them, as they were always "in" with the gentlemen of the Press ashore, and, if they were not satisfied, had it in their power to get the boat a heavy adverse advertisement. As an inspirer of the Press himself, Mr. Horrocks thoroughly understood how this was managed.

Herr Janocky earned the Purser's detestation from the very first moment of meeting. The great pianist showed a vague, absent manner which Mr. Horrocks put down to unadulterated affectation. His pale face, which admirers went into raptures over, struck this critic as merely bilious. His Papuan-like mass of untidy hair seemed to the Purser (who was close-cropped himself) nothing more nor less than a display advertisement, and a very nasty one at that.

Herr Janocky, the great pianist.

Promptly also from the moment of their general recovery from sea-sickness —which took place after leaving Queenstown —thanks to Janocky, the first-class passengers of the Leeds were divided into two violently opposing cliques. A move had been made by an ardent spirit named Pitcairn towards getting up the usual concert in aid of the Sailors' Orphan home. The usual list of amateurs were available, and Pitcairn made up a pleasantly assorted programme. But he was a man with ambition. He wanted Janocky to "do a turn."

He mentioned this to Mr. Horrocks, and suggested that that great man should formulate the wishes of the passengers to the pianist.

"I'll see you in—-melted first. Go and ask him yourself. You aren't shy."

"Oh, but aren't I?"

"Never knew but one drummer yet who was, and he didn't come from Bradford. But if you are scared of Mop-head himself, go to White, his agent."

"Which might White be?"

"That little black chap with the clothes that fit too well, and the diamonds."

"Oh, I know. Or I might get the Skipper to ask him."

"Great thought," said Mr. Horrocks, "I'd do it."

"I will," said Pitcairn, and he did.

Now Captain Clayton had no mean opinion of the position held by the commander of a crack Atlantic liner, especially if the letters E.N.E. stood after his name, and the corresponding blue ensign fluttered from the liner's poop-staff. Moreover, by reason of his own connection with the stage, he felt that if the request came from him, it was certain to be granted; and he said as much.

As a consequence, when, with a good deal of unnecessary offensiveness, Janocky refused flatly to play on anything so commonplace as a steamer's piano, for a mere steamer's audience. Captain Clayton felt the slight pretty keenly. "You should not have come to me with a request like that," said the pianist, by way of winding up his refusal. "You should have approached my agent."

As this little scene occurred in Pitcairn's hearing, a full account of it was quickly common property, and, as I say, the first-class passengers of the Leeds were forthwith split up into two strongly antagonistic bodies. About one-half of them chose to regard Janocky as a Heaven-sent artist, and as something more than human, and these quite approved of his attitude, said that the Captain ought to have known better than to make such a proposal to him, and that to ask him to play on an instrument like the saloon grand (which was not by his own favourite maker), and before an audience that tolerated comic songs and amateur recitations, was nothing short of a gratuitous insult. This party numbered in its ranks most of the ladies amongst the passengers, and as some slight reward for their adoration and loyalty, they prayed Janocky for autographs and locks of his hair and other keepsakes.

They found out that Janocky was a son of one of the oldest houses in Russia, and they raved about his high descent, his sublime art and his personal appearance rather more than was perhaps judicious in the face of such a strong opposition.

The other party, who had, perhaps, more humor about them, possessed an equal command of language. They described Janocky as a more-or-less-strongly-qualified mountebank, and analyzed his "antics" unkindly. They admitted that they might be Philistines, since, according to history, that nation had always held Jews at large in detestation—although Russian Jews are not particularly mentioned in the record. But at the same time they openly confessed their admiration for the pianist's advertising skill, and with mock solemnity formed a syndicate for taking over a certain patent medicine factory in the States, on condition that they could obtain the services of Janocky as manager, to push the sale of the company's pills.

It was into the ranks of this clique that Pitcairn endeavoured to enlist the active assistance of Mr. Horrocks; but that wily man, though the direction of his sympathies may be guessed, naturally could not become an open partisan.

"Look here," he said, "you go to commercial-travel Bradford goods in the States. Would you go and mortally offend one-half of your customers at the expense of the others? Not much. Well, I guess you may look upon the passengers here as my customers. Somebody's set them by the ears enough already without my chipping in to help."

"But we've got a great game on, and we want somebody in authority to bear a bit of a hand."

"I daresay you do. Suppose you think it would be a sort of poetical justice if one of the officers decorated Janocky's flowing locks with a fool's cap."

"That's about the idea."

The Purser laid a fat hand on Pitcairn's shoulder, "You go and try the Skipper, my son."

"Shy."

"Oh, get on! You know him well enough,"

"I've crossed with Clayton twenty-three times for the matter of that. In fact, I seem to know him a bit too well. If we were less intimate, he might see his way to being more civil. As it is, he snaps my head off when I so much as breathe the name of the great Janocky."

"Well," said the Purser, "if you've an ounce of sense you'll see which way the cat jumps, and you'll let things gently simmer down. If you go on, you'll probably get your fingers burned." With which he left Pitcairn, and made a mental note to watch the welfare of Herr Janocky with some tenderness. For the pianist's own personal feelings he did not care one rap. Once ashore he would be quite pleased to hear the man had been brought to derision; but the reputation of the Leeds was a matter which touched Mr. Horrocks intimately, and he did not intend that this should be smirched by any outrageous pranks on Janocky, which he felt sure that objectionable person would wrest round into an advertisement.

As he put it afterwards: "You see I knew the crowd. They were men, most of them, up to the neck in business ashore, and the time they were at sea was sheer holiday to them, and they'd go mad on anything that would help to fill in the time, and give them something to plan and think about. In fact, they were as ripe for mischief as any pack of school-boys,"

However, except that the nickname of The Pillmaker was given to Janocky, and bandied about delightedly by the opposition, no more active scheme of annoyance was invented ; and if it had not been for the injudicious adulation of the pianist's admirers, Mr. Horrocks was satisfied that the incident would have been allowed to drop. But to see the man openly adored by all the women passengers, and fawned on by a section of the men, was obviously a deliberate exasperation for those who were out of sympathy with him, and the Purser, though he carried an indifferent face, stood by anxiously on guard.

The Leeds was exactly in mid-Atlantic when the explosion came, and matters at once assumed a very serious complexion. The news spread amongst the first-class passengers like fire on a gunpowder train, but Mr. Horrocks did not hear it at once. He was arbitrating in the Third Class between two non-English speaking emigrants, each of whom accused the other of theft, and had patiently expended half-an-hour in the endeavour to arrive at a just settlement. But when a peremptory message came from Captain Clayton that he should go up to the chart-house at once, he adjourned his arbitration by clapping both emigrants in irons and ordering a thorough search of their effects. It is a recognized law on liners that the amount of attention received by each passenger from the officials varies directly in the ratio of the fares paid to the Company.

"You've heard what's happened to Janocky?" demanded Clayton.

"No, sir," said the Purser formally. He was always formal with his Captain when he scented trouble.

Afterwards, when hard words had passed, and the matter had been settled up, they could drop their official relations again, and become intimates once more in the space of a sentence.

"Then, Mr. Horrocks, let me tell you it is your business to have heard. You are here to prevent trouble amongst the passengers. And as it is, this scandal is all over the ship now."

"Yes, sir."

"Well, if you don't know," said Clayton angrily, "what's happened is this-" But at that moment the door opened, and in came the pianist himself.

"I understand," he said, "that my agent, Mr. White, gave you some account of the outrage of which I was made a victim last night."

"He did," said Clayton.

"Zo! I have thought well to come and give you the tale myself, so that there can be no shirking of your responsibility through want of knowledge. It is not my usual custom to interfere with matters personally. My agent makes all arrangements for-"

"Let me hear your tale, sir," said the Captain sharply, "if you have one. I don't want a history of your habits. They fail to interest me."

The pianist turned his pale face to Mr. Horrocks. "Ah, you are the principal steward, is not that so?"

"No, sir, I have the honour of being Purser here."

"Zo! Is there a difference?"

Mr. Horrocks kept his temper with an effort. Captain Clayton came to the rescue of his dignity.

"If you were a gentleman, Mr. Janocky, as you claim to be, you would not be so offensive. Now get on with your tale, sir. Our time is valuable."

Janocky was not accustomed to being spoken to like this. Amongst those who fawned upon him and flattered him, it was his time that was looked upon as precious. But he was shrewd enough to see that this grave ship's captain, and this stout purser before him would not put up with too many airs and graces. So, with his pale brows clouded with pettish resentment, he got on with his story.

"I woke up last night," he said, "with the feel of someone snapping something on one of my wrists, and before I was thoroughly aroused, or could resist, something was snapped on to the other, and I found that I was imprisoned by handcuffs. The electric light was switched off, and there is no porthole to my cabin. It is the first time I have ever been given an inside room. On other lines the authorities have always seen that I have had one of the best cabins on the boat."

"This steamboat," said Clayton, "is run as a commercial speculation, not for charity. I feel convinced that the Purser has given you the exact class of room you paid for. If you wanted a better room you should have paid more."

Horrocks felt a pleasant glow, and made a mental comment that the outstanding account between him and Captain Clayton was thereby settled. Janocky looked sullen, and patted his mop of hair petulantly. He did not like this undeferential treatment. But a rap on the table, and a sharp, "Get along, sir," from Clayton, set him talking again. He was not a man of much nerve.

"I could see the fellow only dimly in the light which came from the door. He was of middle height. He had over his head and face and shoulders a towel with holes cut for his eyes, and when I attempted to speak he crammed a wooden gag into my mouth and tied it there with string behind my head. Then he took a razor from his pocket and opened it. I decided that he intended murder; here was some envier of my art!"

"He had over his head and face and shoulders

a towel with holes cut for his eyes."

Unconsciously the pianist warmed up to his tale. The dramatic instinct was overcoming the sense of resentment.

"But no, murder was not threatened. A worse injury was brandished against me. My art, the touch which Heaven has given me to enrapture multitudes, was made into a vulgar commercial counter. The assassin approached his razor to my wrists. Either he would cut the tendons, and rob the world forever of the sound of my playing, or I should write and sign a bond to ransom them by the payment of £10,000. With such an alternative, there was only one choice. I must make any sacrifice to preserve my art. So I wrote as he dictated, that on my honour as a gentleman I would pay him this money he demanded, at the close of my tour in America, and pay it, too, in such manner that he would never be detected. Then he went away, and I lay half fainting till next morning came, and with it a steward, who presently brought an evil-smelling mechanist, who filed the fetters from my wrists. That is all."

Pooh!" said Mr. Horrocks, "there's nothing binding in a scribble written like that. It's only one of the passengers having a rise out of you. You lay yourself open to this sort of thing, my good sir, with your confounded affectations. If you'd more sense of humor, you'd have seen through it for yourself."

"It is evident that you cannot appreciate my point of view," said Janocky. "I am a gentleman; therefore I shall do as I have promised. The money must be paid, and it rests on my honour to find a means of doing this so that the recipient shall not be discovered. It is quite possible you and other people might have acted differently under the circumstances. I cannot understand your codes. I do not wish to understand them. I am a gentleman."

"I hear you say it," commented Mr. Horrocks, and shrugged his plump shoulders.

"Could you recognize the man who came to your room?" asked Clayton.

"I could not. It was dark, and he was covered as to the face with a towel. He was short in height. That is all I know. It was so dark that I had to write on the paper by feel. The paper, too, was so thin that once the pencil went through it. But I wrote what was demanded, and I shall carry out my promise."

"Well," said Clayton, "I have heard your statement now, sir. May I ask if you have any proposal to make?"

Herr Janocky looked up at the roof of the charthouse with languid insolence. "I should say that if you cannot protect better the passengers who intrust themselves to your care, your Company should pay the blackmail which is levied."

"I will make a note of your suggestion. Is that all you have to say?"

"It is."

"Then don't let me detain you here any longer."

Actually this shipmaster was ordering about Janocky! The pianist gasped. His pale face almost flushed. But he went. There was a look about Captain Clayton of calm dignified command that sterner men than Herr Janocky had found embarrassing.

"He's rather a noxious animal," said Clayton, when the door closed, "isn't he?"

"Oh, I never made any secret of it to you that I mistrusted the whole breed of theatricals," Mr. Horrocks admitted.

Captain Clayton frowned, but he did not pursue that point for the present. "I've had this man's agent in to see me. He gave about the same tale with a few variations and additions. It seems a pretty bad case. Of course, they'll make out ashore that we are responsible for the whole thing."

"If I know anything about the New York papers, we're in for a hot time unless we can turn the tables on them. But, great Washington! I'd give something to have my knife into Mop-head."

"I can imagine it." Captain Clayton quite appreciated the depth of Janocky's insult in mistaking Mr. Horrocks for a steward. "Well, Purser, I think you're more capable of working out this affair than I am, and so I'll pass it over to you."

"Have I a free hand, sir?"

If you can prove definitely and publicly that Janocky is trying to get at us —and I've somehow a suspicion of that—you can cut his hair for him for anything I care."

"Very well, sir," said Mr. Horrocks, and left the chart-house, and forthwith sought the society of the pianist's agent.

White, the agent, was an American Jew by nationality, and sufficiently well-travelled to have a full idea of the dignity of a big Atlantic liner's purser. He expressed gratification when invited down in Mr. Horrocks' room, and regret that he and his principal should have ruffled Mr. Horrocks' ease. He was just the man to appreciate gratuitous champagne, and he was given champagne of an eminent vintage. The Purser had an infinite tact over these details.

He was just the man to appreciate gratuitous champagne.

"Janocky is Janocky," said White, "and plays his own game. But I guess you and I are just plain, downright business men, Purser, and we only work on bedrock facts."

"That's so," said Mr. Horrocks. "Now, I told Mr. Janocky, when he gave the Skipper and myself his yarn, that the bond he talked of wasn't worth a farthing, and he'd no more call to pay than I had. You're with me there?"

"Not one millimetre."

"You're not?"

"Not any, siree. Why, don't you see, the man with a towel was playing my game all along? I get paid by results. So it's to my interest to make the great name of Janocky just hum, and I don't care a red how I do it. Why should I? I'm not in this agenting business just for my health."

"You wouldn't be. Let me fill up your glass."

"Thanks. I'll even go further with you, and own up straight that it's me to a very large extent that's kept Janocky up to the sticking point. If we didn't take it seriously, it would lose him popularity at once. You see, we play a certain game. He's adapted for it by nature—hair, old family, pale face, live-for-Art, gentility, and all that-and I keep him up to it, hundred and ten cents to the dollar. But it's a difficult game, and it's easy broke down, and if there's one thing we couldn't stand more than another, it would be to be made ridiculous."

"Oh, I quite see that. But won't your man look a bit of a fool anteing up £10,000 when there's no earthly need for him to part with a farthing?"

"Nos'r. Who'll pay that money? Not the great Janocky! Not much! You see, between you and me, he's a Jew, and that nationality isn't fond of chucking away its hard cash." Mr. White shut one eye and looked appreciatively at his wine-glass. "Nos'r. But don't you see that his admirers in the States will hand round the hat and make up that £10,000 smiling? They'll just jump at the chance of proving their gratitude to the man who spared

to the world of music the tendons of Janocky's wrists. You know all about working the newspapers, don't you?"

"Some," said the Purser.

"So do I. That's why I'm Janocky's manager. An' I guess I'll fix this up as easy as falling off a cable-car."

"Have you any idea who the blackmailer is?"

"Nope. Reckon I'm satisfied enough with things as they are. I'm not the man, sir, to quarrel with a good advertisement. But if you want me to give a guess, I should say it was a woman who held him up. Four of them have proposed marriage to him on board already. And the odds are, it's one of these that's done it out of spite."

"Who says they proposed to him?"

"Oh, it's fact enough. Women do. He gets about five proposals a week on the average, some of them in writing, some verbally. I've both read and heard them. It's all part of the outfit."

"Like the hair and the gentility?"

"I suppose so," said the agent pleasantly. "Great thing is to find out what your public likes, and then give it them. We do that. Why, I calculate eighteen per cent, of our receipts at concerts comes from front seats taken by ladies who are in love with that 'elegant sweet Janocky.' Say, this is real nice wine,"

Mr. White was all affability and frankness, but when the Purser summed up results afterwards, he found he had got very little out of him. Moreover he was not in the least to be turned away from his plan of campaign. "Of course, it's a purely business matter," he confessed, "and has to be treated as such. Let alone I have my own percentage to look after, there's Janocky who wouldn't give way."

"Why I thought he was far too big a gentleman to tarnish his mind with the idea of vulgar finance; I understood he left all, business entirely in your hands."

"Oh, does he?"—Mr. White shut one sharp eye—"I know he lets on to that in public; it's all part of the game; but between you and me, the man's a Jew by birth, and he's as keen as most of his tribe. There are no flies on Janocky when it comes to raking in the cash."'

"I hate to have any boat I'm on mixed up with a thing like this."

"Natural, I guess. I'm sure you know. Purser, that I just hate to annoy you. But this racket's hard business with me, and one can't give way to sentiment about it."

"No," said Mr. Horrocks, "I suppose not. Well, what I must do, is to lay hands on that bond."

The agent laughed genially. "I wish you joy of your hunt. But, say, isn't it rather a big contract? The man or the woman who's savvy enough to think of such a piece of blackmailing, would have enough sand left over to hide their receipt pretty brightly."

"Oh, I don't say I'll stumble upon it without trouble."

"I should smile. Why, sir, you can't search the ship. You can't go and smell through all the trunks, and unstitch the soles off all the passengers' shoes, and examine their persons like they do the Kaffirs at Kimberley. That would make a worse scandal than leaving things as they are."

The bottle was empty, and Mr. Horrocks allowed his guest to depart then, and presently he himself went out for a tour in some of the passage-ways and cabins of the great liner, making exhaustive inquiries. He cast about here, there, and everywhere for a clue. He put questions right and left. He cross-examined half the stewards on the ship, and personally searched the great pianist's stateroom with a microscopical accuracy. And at last he got hold of a glimmer of suspicion, and worked on at it with grim, tireless persistence.

The purser did not err on the side of overscrupulousness in his methods; the occasion did not seem to him to demand too much niceness. To those of his intimates who talked on the subject, he said that he acted as ship's purser merely to earn his pay; but somewhere deep within his rotund exterior there was a strong love for the vessel on which he served, and a high regard for her chastity. Mr. Horrocks was a bachelor, but if he had possessed a wife he would naturally have been resentful against anyone who brought scandal against her. He told himself that all his affections were concentrated on the institution called "Rocks' Orphanage,"' of which he was sole patron and autocrat, and that he cared for nothing in the wide world beside. But when it came to the point, he showed he could be as jealous of the reputation of the Leeds as he had so often shown himself to be for his darling institution.

As a consequence, when the chance of revenge for the Janocky episode did come in his way, he was inclined to be vindictive. He might have called in the master-at-arms on board. He might have preferred a charge to the police ashore in New York, and given the culprit into their custody, and secured for him a spell of contemplation in the penitentiary; but he preferred his own to either of these methods.

White himself had pointed out that ridicule was the lash which Janocky dreaded most. Moreover, a great steamer line, like a pianist, lives and prospers to a great extent by the favour of the Press ashore, and Mr. Horrocks had a keen eye to the advertisement of the Town S.S. Co. The tale, if it came off as he intended, would be told humorously, but it would none, the less show to intending customers that the Town Company took a most fatherly care of all their passengers, and that on the S.S. Leeds in particular they were most keenly looked after. And finally, he had got in memory that Janocky had shown gratuitous offensiveness in that matter of his official dignity. Mr. Horrocks did not easily forgive anyone who mistook him for a steward.

With a grim appreciation of the dramatic fitness of things, Mr. Horrocks timed his exposure to take place when all the passengers were gathered together in the saloon on the occasion of the ship's concert.

As a general rule, the Purser took a very lukewarm interest in that usual incident of a transatlantic voyage, the ship's concert. The proceeds, by immemorial custom, went to the Sailors' Orphan Home, and people paid freely and cheerfully. As was natural, they only made outlay of a certain amount in charity during the voyage, and as a consequence, having paid up this at the concert, they invariably turned a deaf ear to the claims of that less-known institution. Rocks' Orphanage, however deftly its worthiness was urged.

But on the present occasion Mr. Horrocks threw himself with ardour into the task of making the concert a success. The first movement towards holding it had been originally set on foot, as has been mentioned before, by Pitcairn, principally because that worthy man wanted to boast afterwards in Bradford that once he had been the Great Janocky's impresario. Once the chance of doing this had been taken away, Pitcairn's interest dropped, and when he decided that he "wasn't going to bother about it any more," no one else saw fit to put on his discarded mantle.

The Purser, however, by a little judicious raillery, soon brought up Pitcairn once more to the scratch, and when on the top of this he whispered a certain little secret into his ear, that amateur manager snapped his fingers with vast delight.

"No, really?" he said. "It's a bit too good to be true. Are you sure you've got him?"

"On toast," chuckled the Purser. "Don't breathe a word. You're the only man on the boat I've told. Even the Skipper doesn't know."

"Catch me letting on. I'll do my share; that concert shall hum. But you'll have to guarantee that the Great Janocky shall be there, and you'll have to get his signature."

"I'll work that through White, easy enough. He's a great man. White, when you know how to deal with him. So free and open. Keeps on telling you in confidence Janocky is a Jew."

They both grinned.

"Can we have the Second Classers into the concert?" asked Pitcairn.

"Well, it's against our usual rule. But I'll make an exception this time."

"You ought to," said Pitcairn. "The larger the audience the better Janocky performs. He says so himself."

Mr. Horrocks, however, on second thoughts approached Herr Janocky himself, and proved himself an accurate judge of human nature.

Where anyone else would have been suspicious, the pianist's vanity helped him easily into the trap. Herr Janocky promised not only to attend the concert and sit in the front row, so that seats near him might be charged at double figures, but also he consented to sign one of the programmes, so that the precious autograph might be put up to auction for the benefit of the fund. He was even so unsuspicious that he could not forego the opportunity of being offensive.

"Let me see," he said in his vague, absent way, "you told me you were Purser here, didn't you?"

"Quite correct, sir," said Mr. Horrocks.

"I somehow thought you were head steward. You couldn't take a message for me, could you, to my bed-room steward? I want my pillow-case changed. The one I have to put up with at present is coarse and full of holes."

"I somehow thought you were head steward."

"I am not here to be your messenger boy," said Mr. Horrocks furiously, and turned away. He was angry with himself for allowing this pianist to draw him, but really his own proper pride had to be considered.

However, when the evening of that day came, and with it the concert, he was able to take as complete a revenge as any man could desire. Pitcairn was the man who was running the concert, and nobody could mistake the fact. Pitcairn had crossed between Liverpool and New York so many times that he felt he had a proprietary interest in the North Atlantic and in all amusements carried on upon its waters, and he let everybody know it. The passengers did not mind. They are apt to be good-natured on little points like these. They were quite ready also to encore every item on the programme, not because of its merits especially, but through deference to the performer's feelings. In fact a pleasanter audience than the one on a first-rate Atlantic liner which assembles for the usual concert, it would be hard to discover.

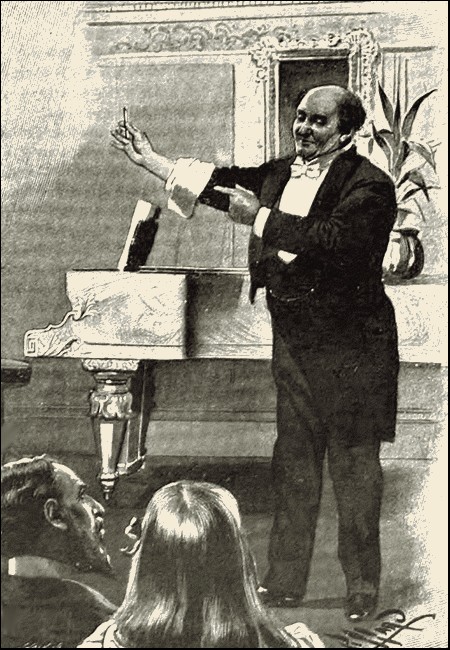

This concert, then, like all its thousand predecessors, went through its appointed course with friendly appreciation, and Pitcairn fussed about to keep himself thoroughly in evidence. But when the last song was sung, Pitcairn mounted the platform and made his final announcement.

"Ladies and gentlemen," he said, "Mr. Horrocks will now do a turn. His talents are too well known to you to need any introduction from me. He himself will explain what he is going to do. Ladies and gentlemen, I present to you the fairy Purser."

Whereupon, amid a chuckle of amused laughter, Pitcairn got down, and the burly form of Mr. Horrocks took his place.

The Purser could make a good speech, and he knew it. He made a good speech then, pleasantly humorous, delicately pathetic. He put forward the claims of the Sailors' Orphan Home, thanked the audience for coming to the concert, thanked them for what they had subscribed already, and hoped that they would bid well for the programme that he was now about to offer for auction, and that he would be able to knock it down at a price worthy of the name that was written on it. The programme would be one to be preserved. It would carry memories with it. It would carry also the signature of the best known pianist of the day.

Mr. Horrocks, with an effort, got a finger and thumb into his waistcoat pocket and fumbled there. "H'm, lost my pencil," he said. "Mr. White, will you lend me yours?"

Mr. White, all smiles and diamonds and glitter, handed up a gold pencil case.

The Purser grasped it between the tips of a fat finger and thumb, and drew back his shirt cuff and sleeve to expose a bare and brawny arm, after the fashion of a conjurer. He cast down his eyes on White, and that person moved in his seat uneasily.

The Purser grasped it between the tips of a fat finger and thumb.

"Now before we go on to ask Herr Janocky to put his valued signature to the programme, I propose to show you another little matter that will interest you. I have here a gold pencil case given me by Mr. White. There is no deception, ladies and gentlemen; nothing up the sleeve; no palming. I haven't a cat's notion of sleight-of-hand, as Mr. Pitcairn or any other gentleman here who knows me will testify. But I can do one little conjuring trick just now. You all see this pencil case?"

"Yes, yes."

"Which belongs to Mr. White."

"But does it?"

"Mr. White, is that your pencil case?"

White cleared his throat and said in rather a strained voice that it was.

"Well and good." Mr. Horrocks laid the pencil case on the top of the piano. "Now, ladies and gentlemen, it will be fresh in your memory that Herr Janocky has been thrilling this boat with an account of how some ingenious person came to his room in the night, and offered him a choice between having his wrists hamstrung or paying up blackmail. It will not have escaped you that he chose to pay."

"Quite right of him," shouted someone.

"No doubt, no doubt. And so he entered into a bond to ante up £10,000, writing it out and signing it himself. He could not identify his visitor (so he says), and as a consequence you all lie under suspicion. So I thought it would be a fitting opportunity this evening to show who was the ingenious person who has caused so much excitement. Will any gentleman or lady oblige me by breaking up that pencil case?"

White stepped up.

"Other than Mr. White. Sit down again, sir. Great Washington, if you don't sit down I'll have you taken away and put in irons. Ah, I thought we should have peace and harmony again."

"You'd better open the pencil case yourself," said Pitcairn.

"Well, if the meeting wishes it," said Mr. Horrocks, and took up the pencil gingerly between his fingers. "You see, on close examination, those of you that are near enough, that the end is fastened with sealing wax. Now, I'll chip this off, and there you'll notice there's a little hollow inside stuffed with a roll of paper. Will someone oblige me with a pin?"

Mr. Horrocks held the pencil case at arm's length towards the audience, and picked at it clumsily with the pin. Every eye in that huge, gorgeous, sea dining-room hung on him unwinkingly. The eyes of Mr. White and Herr Janocky watched with something very nearly approaching terror in them.

The Purser worked with vast deliberation. "I must not tear anything," he explained. And by degrees the end of a little tightly rolled cylinder of paper showed itself, which at length he managed to grip with his stumpy fingers and pull out. He unfolded it with vast care, working with hands held far away from his round body, as a conjurer works before his audience, and in the end he pressed it out flat, and waved it towards Janocky.

"Do you recognize this?"

"Yes," said the pianist.

"Your handwriting?"

"Yes."

"The bond you gave to the fellow who called on you that night?"

'"Yes."

"Would the caller be the height and build of your friend Mr. White?"

"Yes."

"Very well," said Mr. Horrocks. "As to whether Mr. White really intended to extract his blackmail, or whether you really intended to pay him, or whether the whole business is merely one of your advertising dodges, you can settle between yourselves. I don't know, and I don't care. What I'm pleased about is that this boat leaves the court without a stain on her character, and that you, ladies and gentlemen, are cleared of the suspicion that there is a blackmailer among you. That's all I've got to say."

Pitcairn jumped on to the platform. "Ladies and gentlemen! With musical honours, and as loud as you like it. 'For he's a jolly good Purser.'"

Which chant they sang very heartily.

"Say!" cried a voice at the other end of the room, when the roar of song had ended, "there's a syndicate been formed on board here to acquire a certain pill factory in the States, provided we could get a certain party who's with us to-night as advertisement manager. Well, he didn't seem to chip into notion before, but now that we've seen his skill, I'm empowered to double our original offer. I should say that he'd be wise to close. Seems to me he'll find the States have rather soured on his piano playing for the present."

With which piece of bitter mockery the concert broke up.

Now, at the hint of Mr. Horrocks, Captain Clayton had discovered that the duties of navigation would keep him all that evening on the bridge; but when the lights were switched off for the night, and the passengers had turned in, the Purser went to the chart-room and laughingly told what had happened. He was very pleased with himself, and made no effort to conceal his satisfaction. Indeed, Clayton was equally pleased, and congratulated him cordially on his success. "But I want to know how it was done," he asked. "How did you work up to it?"

"That's my secret," said Mr. Horrocks grudgingly.

"But mayn't I share it?" asked the Captain.

"Well, I haven't told another soul on board and don't mean to. The result was quite enough to give them. It spoils a trick to tell how it's done. But I suppose you're Skipper. Well, you see it was this way. I examined the handcuffs which were filed off Mop-head's wrists: no result from them: then I went myself and searched his room; found nothing. Then I called a muster of all the stewards who serve that alley-way, asking them to look for any relics—key of handcuffs, you know, that towel with the eye-holes in it, or, in fact, anything suspicious. An hour afterwards his bedroom steward brought me the gag that had been used in Mop-head's mouth.

"I can't say I' saw anything special in it at first. It was just wood and string. But presently I noticed that the string had got two different colored strands in it, green and white."

The Purser paused gloatingly, so Clayton laughed again and said: "Oh, go on."

"Well, I had another muster of stewards and exhibited the string. Had they seen any more like that? Yes, one of them had swept up two bits from White's floor. Where were they? Flung overboard naturally. But the steward was sure it was the same string, white with a green strand.

"Now that wasn't much to go on, of course, but it gave me a tip. I'd had my eye on Master White before; so I got an opiate from the doctor, and slipped it into his bedside tea next morning, and let the steward take it in as usual. I'd Mr. White laid out and sleeping like a corpse in ten minutes.

"I waited till he was sound off, and then I paid a morning call, and I guess I went through his traps as thoroughly as any professional burglar could have done it. Not a bit of luck. There was no bond, or anything like one.

"So I went through his effects a second time.

"Now you'll have noticed what a very smart, overdressed man he is. Too much shine everywhere, too many diamonds; things all too new and glittering. But in his waist-coat pocket was a gold pencil case that was out of keeping with his general gorgeousness. It was scratched, and newly scratched, all at one end. The top had been off—"it struck me it had been wrenched off with a pocket knife, and it was fastened on again with red sealing-wax. The edges of the wax were new and shiny, not dull like they get if they had been carried in your pocket for a day or two. And then I looked at his pocket knife, and one blade was nicely jagged."

"Good man, Horrocks."

"Pure deduction," said the Purser, rubbing his fat hands. "So I whipped off the top, and there was paper inside. I pulled it out: it was the bond right enough, signed Janocky.

"Now, it wouldn't do to own up that I'd loaded an opiate into a passenger's morning tea and searched his traps, so I put back the bond again, mended up the pencil case, and stowed it back in the pocket of his waistcoat. It had struck me that this sort of person likes the bright light of publicity on some of his doings, and, as I hadn't been spared much, I didn't see why I should be gentle on my part. So I worked up that busy ass, Pitcairn, into getting the concert going again, and when it was over I 'found' the bond inside White's pencil before all the passengers. I think most of them enjoyed it."

"Bravo! You're a great man, Horrocks."

"I don't know about that. But I'll bet I've made a slump in Janocky shares in the States for a bit. Perhaps it'll teach him to be a bit more civil to the next purser he meets. And, what's more, I can work the Press for a pretty good ad. for the boat."

Mr. Horrocks was right about that last aspiration. When the passengers got through the weariness of the New York Customs House, and reached their hotels, they were able to read in ten papers all about "Janocky's latest advertising dodge." "How they pamper their passengers on the Leeds," and a spirited eulogy of "The brightest Purser on the Atlantic Ferry.'

Mr. Horrocks had a fine art in handling the Press when he possessed good material.

But the incident had a more far-reaching effect than the stout Purser dreamed of at the time. There was on board the Leeds a little, unobtrusive man, whom no one honoured with much attention, but who watched matters that befell around him with a keen and kindly eye. His keenness had in recent years made him a millionaire. His kindliness prompted him to make inquiries concerning the work which was done by the remarkable institution. Rocks' Orphanage. His wealth enabled him, by the mere penning of a check, to endow the place with an opulence to which even its founder's dreams had never aspired.

His one proviso was that Mr. Horrocks should settle ashore and manage the Orphanage himself. And so the Western Ocean ferry is the poorer for the loss of its most popular and capable Purser, and the name of Horrocks no longer appears on requisitions and passenger-lists.

But in a certain Mr. Rocks, a personage of majestic port and somewhat pompous mien, old passengers think they sometimes trace a resemblance to one who, for a space of days, they were once proud to acknowledge as a friend.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.