RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Pearson's, November 1900, with "The Pirate"

The Derelict, Lewis, Scribner & Co.,

New York & London, 1901, with "The Pirate"

The Derelict, Lewis, Scribner & Co.,

New York & London, 1901, with "The Pirate"

CAPTAIN CLAYTON rather twitted Mr. Horrocks afterwards at the ease with which the man Cragie had managed to strike up an acquaintance with him; but looking at the matter impartially, one does not see very well how it could have been avoided. It is part of a purser's professional duty to know as many people as he can possibly get at, and be liked by the highest possible percentage of them. On a little matter like this often hangs a passenger's choice between two rival steamer lines.

A purser cannot consult his own feelings on this subject. He may hate to be a humbug, but he has no remedy as long as he remains in his firm's employ. In Mr. Horrock's case there were scores of persons who said "that fat Purser is a right good sort, and I like him no end," whom he would cheerfully have seen hanged. But he had to be civil and attentive and amusing to them, and swallow all trace of dislike.

In fact it was in a large measure for doing this that he drew his salary.

Cragie, too, knew his game, and played it like a man. He came up to the Purser when that worthy man had just looked in for his "morning" at down-town Delmonico's, and caught hold of his hand, and shook it heartily.

"I'm very pleased to meet you again, Mr. Horrocks," said he. "You'll have forgotten my name, but I'm Charles L. Cragie."

Mr. Horrocks returned the hand-shake. "Ah," he said, "Let me see-"

"Don't apologize," said Cragie. "You'll meet some five hundred fresh faces every trip, and I know it will be hard enough to remember them, let alone the names. But don't you recollect my winning that auction sweep on the run?"

If he had asked if the Purser did not recall him through his habit of taking pepper with his vegetables, it would have been equally to the point. But it was not Mr. Horrocks' habit, for reasons already laid out, to deny acquaintanceships, so he said, in his genial way: "Oh, of course; I've got you clearly enough now," and the pair of them fell very naturally into talk.

The Purser's description of the man showed insight. "The way this Cragie lowered whiskey sours," he said, in telling of him afterwards, "made me think that his next trip would be to the Keely Cure Institute; but he seemed to be a man well used to business in a small way, from the glib knack he'd got of bringing figures and prices into his ordinary chatter.

"Your big business man, or your swell, or your ordinary tourist, will take a drink and stand at the bar, and just talk about the weather, or people he's met; but fellows like this Cragie, who are as keen as knives on dollars, and not over-successful at catching them, can't help dragging money into the most ordinary conversations. They'll guess at the price of the prints behind the bar, and smack their lips over the figures, and they'll want to know how much the liquor cost a dozen before they've got a glass-full comfortably down their throats."

Mr. Horrocks still did not remember the man in the very least. But that was nothing strange. It is a physical impossibility for a purser to keep in mind all the tens of thousands of passengers with whom he comes in official contact. However, he made out incidentally that Cragie was a man who always took one of the best rooms on the boat in which he crossed, and ran up a heavy wine bill, and was over and back between Liverpool and New York some three or four times every year. It seemed, too, he had a way of sampling all the different lines, and so Mr. Horrocks took pains to point out to him that the way to secure comfort and attention was to stick to one boat, and get known and liked on her. If he did not quite understand, also, that the Town Line was the smartest on the North Atlantic Ferry, and the Ambleside was the pick of the Town Line's fleet, it was not the fault of the Ambleside's Purser.

But Cragie did not accept all this without demur.

"What I complain of about your Town boats," said he, "is that you're so unpunctual. You advertise you'll arrive on the 15th, say, and I cable to make my appointments accordingly; and then either you don't turn up till the 18th, and I miss a lot of business, or you have some fancy game of cutting a record and get in on the 14th, and I have a day loose on my hands, and naturally get a bit on the whiskey crawl. See what I mean?"

"Mr. Cragie, let me tell you, you never made a bigger mistake. You're thinking of the Blue Moon boats. We run like a train. We're always on schedule time."

"Well, I know the last time I crossed by one of your Town Line boats—it was the Glasgow, by the way—she set me down on the Liverpool stage a day and a half before time, and I can tell you it was a beastly nuisance. I'd nothing on earth to do for that time, and got on a deuce of a jamboree in consequence. Took me a matter of three days more to get straight again, and so I lost four-and-a-half days' business all through your fault."

"It might be an interesting case for the Courts, but I don't think you'd get compensation from our Company over that."

Mr. Cragie grinned. "Oh, I know my way about. But it's a fact she did come in sooner than I'd reckoned on, and I'd got a time-table from a tourist bureau to make sure of the date."

"There you are, then. Why don't you go to headquarters for what you want? We don't guarantee any time-table except our own: in fact, most of them are inaccurate. We give out a list of approximate departures and arrivals at the beginning of the year, but circumstances often arrive which make us modify them."

"I see. Your directors suddenly get up a notion they'd like to try and break a record with one of your boats for the sake of the extra advertisement, and so put more coal on board, and let the old time-table go hang. But where's one to find out about that?"

"At our own office right here in New York. Where else? They're always delighted to give any information to passengers."

"I see. And could they tell me the exact dates when you sail with the Ambleside, and when you arrive?"

"Of course. But I can do that myself if you want it. To-day is Friday. We pull out from here next Tuesday at 1.30 middle day, and put you in the London train at Liverpool at 3 o'clock in the afternoon of Wednesday week. Run you up to town in time for a theatre."

"Or breakfast the next morning, which?"

"Exactly as I have said."

"Will you bet on it? Will you bet you don't vary six hours on either side of that time?"

The Purser stared at the man curiously. His face was working with excitement. There seemed to be something out of balance here. Why should it matter to Mr. Cragie so vastly whether the Ambleside ran on schedule time or not?

"You seem very keen on it," said Mr. Horrocks. "By the way, I forgot to ask. Are you crossing by us?"

"No, I'm sorry, but you won't get there till too late for me. I must take to-morrow's boat. But about that bet. Is it on? Look here. I'll lay you five to three in thousand dollar bills you're not there within eight hours of the time you mentioned."

"I'm not a gambler," said the Purser, "and, moreover, I'm a man with very little loose cash. But I'll take you in hundreds."

Cragie's excitement grew. His face was white and sweating. He was bending up an ash-tray in his fingers till the barman took it away. "Look here," he snarled, "you're trying to get out of it. If your old boat's worth a copper for reliability, the money'd have been a cert to you, and you'd have snapped up the bet like winking."

The Purser tried to puzzle out what the man's motive might be in all this violence. Was this Cragie trying to fasten a quarrel on him? Mr. Horrocks had every intention of avoiding that. He was not a man who saw any amusement in a fracas with an ex-passenger in a public barroom. He was always majestically conscious of the reputation he had to keep up. So he gave a fat, easy laugh, and pretended not to see that there was anything wrong. "My dear Mr. Cragie," he said, "I have not the smallest idea of losing three hundred dollars to you, and your five is as good as earned for me if you persist in making the bet."

Mr. Horrocks gave a fat, easy laugh.

"Persist!" shouted the man. "This will show you whether I persist!" He lugged out a pocketbook and thumbed five hundred-dollar bills. He slammed them noisily down on to the counter. "Now!" he cried, "dare you take those, with the barman here for a witness?"

"Certainly, my dear sir." Mr. Horrocks doubled the notes neatly and slipped them into a pocket over one of his curves. "And if the Ambleside fails to get in at the time I said, why then I shall owe you eight hundred."

"You're beginning to see yourself paying it already."

"If I thought there was the smallest likelihood of that, you would not have noticed me pick up your money. I didn't want to bet with you, because I've been taught it's wrong to bet on a certainty, but as you insisted, well, I guess it's your funeral."

"Have another drink on that?"

"No, I should say we've both about had our load. Besides, I've to go back to the office again." So there they parted.

The Purser stumbled across Captain Clayton getting out of a Broadway cable-car half-an-hour afterwards, and it struck him that it would not be a bad thing to underwrite part of his risk So he told him about Cragie and his bet. "I suppose it's a safe enough thing. Captain?" said he.

Captain Clayton licked a leaf that was loose on the end of his cigar, and shut one eye thoughtfully. "Delays might happen, of course. And, on the other hand, old McDraw might by accident burn fifty tons of coal too much, and get her there before time, unless I gave him word to keep on the normal. And then there's Queenstown. It's a ticklish job getting off your mails at Queenstown, and time's very easily picked up there —or dropped. How much was it you said you stood to win over this little game, Horrocks?"

The Purser laughed. "Look here," he said, "I'm open to betting you two hundred to fifty you don't get her in on time. Here's two hundred."

Captain Clayton winked pleasantly, and put the notes in his pocket. "After all, why shouldn't I have a share? I'm the man who will really do the winning. You merely stand by to pouch the result."

"Well, don't lose, that's all. I don't want to pay Cragie."

"And I don't want to pay you. Which way are you going? Back to the office? Well, I'm just going in here to buy a tie, and then I'm off to the Fifth Avenue for a luncheon. So long."

The Ambleside, thanks to Mr. Horrocks' personality and exertions, was always a popular boat, but that return trip she was exceptionally full. A great exhibition on the Continent of Europe was drawing Americans sightseers across the Atlantic, and berths were booked weeks beforehand. On the Ambleside their first-class passengers had overflowed into the second-class rooms, of course at unreduced fares, and, moreover, express freights were exceptionally good just then, and she was loaded down to her marks.

The dividends on the run would be princely, and Mr. Horrocks thought that, under the circumstances, the Board could scarcely avoid seeing what an excellent servant they had in him, and would raise his salary there and then by way of cementing his connection with the line.

Mr. Horrocks was badly in need of additional funds just then. The orphanage which he ran in a Cheshire village under the pseudonym of "Mr. Rocks" was draining his resources to the uttermost copper. In a moment of exceptional prosperity he had built on a new wing, opened it himself with a thrill of pompousness and pride, and then, with all his feelings of humanity aroused, bought and stole wretched waifs from the Liverpool slums to people it.

He had promised himself that the additional mouths should be filled somehow: and that he would make money to pay the increasing bills by getting hold of extra "pickings," or from increase of salary, which he felt that the Town S.S. Co. could not much longer withhold from him. But the pickings evaded his keen grasp, and, though surely no purser ever worked more diligently in a firm's interest, his salary remained stationary.

In this particular voyage, then, of the Ambleside, he saw possibilities of profit for the company and advertisement for the Line, and intended to push both to the furthest limit. Never should there be such a happy, contented crowd of passengers; never should the wine bills be so big; and if Rocks' Orphanage did not come by its due reward, well, Mr. Horrocks felt that Providence would scarcely be giving proper attention to its legitimate business.

But in an ocean voyage there are infinite possibilities, and it is the unforeseen which usually trips the modem mariner. With the high scientific appliances of these latter days, the sounding machines, the Thompson's compasses, and all the other perfect utensils of navigation, it is seldom that, on the known routes, a well-found liner is cast away, either through fog, current, or bitter gale. She is driven full speed ahead through whatever weather is sent down upon the seas, and, though her officers may suffer from strain and exposure, she runs between her ports with the regularity of a railway train. Her vital point is in the engine-room. No amount of outlay and care make boilers and steam-pipes and machinery absolutely infallible.

So it came to pass that on the morning of the fourth day out of New York, instead of the passengers being awakened by nimble bedroom stewards carrying biscuits and well-boiled tea, a sudden rump, bump, whizz of the engines brought them into sharp wakefulness. Then, for a second or two more, there was an uncanny grinding, which some half-dozen observers said reminded them of the crepitation of a broken bone, and then the engines stopped, and a new sound of waves slapping against the steamer's flanks took the place of the swish-h-h of rapid transit. The passengers turned out from their bedplaces, and began hurriedly to dress.

Then upon the scene appeared the burly form of the Purser, giving instructions to the stewards with tongue, elbow, and hand. The stewards, being human, were as much startled as everyone else, and wanted to go on deck and see for themselves what was the matter. But Mr. Horrocks soon brought them back to routine.

"Away with you, now, and see to your rooms. You can pass the word it's only a broken shaft, and we'll soon have that fixed up. Nothing in a broken shaft. And breakfast's at the usual time. No alteration in anything. Oh, yes, and it's fine weather on deck, but rather cold."

The stewards spread the placid message. Mr. Horrock's diagnosis was guess-work, of course, but it happened to be correct, and presently news was brought down to this effect. The passengers, after the first shock of alarm, were disposed to take things coolly enough, and the stout Purser went round from room to room paying early morning calls with easy familiarity. There was not the least occasion for alarm. Already a steamer had come up to their assistance, and arrangements were being made for towing. They might be a few days late in arriving, but as for safety, they stood a precious sight less chance of danger on the Ambleside than they did ashore with all those nasty cab-accidents, and gas explosions, and earthquakes knocking about.

The Purser found opportunity for going on deck presently and found the Ambleside looking much as usual, except that she sat down rather emphatically on her tail, and had her bows rather further out of the water than seemed quite necessary. McDraw, the Chief Engineer, came up from below about the same time, and trotted briskly towards the upper bridge ladder, exuding a thin stream of dirty water from his clothes as he ran.

Mr. Horrocks would have liked much to follow him, but he knew that on these occasions a purser, be he ever so magnificent, is apt to be snubbed by the executive. So he planted himself at a point where Captain Clayton could not fail to see him, and waited for an invitation. In the meanwhile he could clearly hear the old Chief make his report.

"I was in my berth when it happened. She runs that sweetly there's vara sma' occasion for me to turn oot every watch. Besides, I've three good watch officers that I'd trust to tend her as weel as you or mysel'. It was my Senior Second's watch when it happened, an' he reports to me he heard the shaft break with a gr-reat noise, and that the bedplates buckled and knocked him over. She raced a bit before he could get her throttled down. But there's naething broken in the engine-room. They're graand engines, thanks to the care that's been given them. There was water coming in pretty free from the shaft tunnel, so I dropped down the slide door mysel' and cut it off. Ye mind that slide operates from the top platform?"

"Yes, yes," said Clayton. "But is the smash past repair? You carry a spare section of shafting; can't you fit that in? You say your engines are all sound. Can't the break be got at? Is it the tail shaft or where?

"Tail shaft or intermediate. I neither know, nor does it matter. The shaft tunnel's pairt an' parcel o' the broad Atlantic just noo, an' it's my belief that when the shaft went jimmy, it peeled off a square fathom or two of plating as remembrancer. Our future help cometh fra' the Lord, Captain, an' fra' yonder steamboat He has sent with a tow-rope sticking out of her rump. My engines do no more work till we've been through a dry dock."

"I see you're blowing off steam."

"All but what's wanted for ma bilge pumps. There's a good sup o' water come through into my engine-room before the shaft tunnel was shut off. But we're getting it under nicely. I shall set my chaps on to tallow down the main engines when they're cool."

"Very well," said Clayton shortly, "that will do," and as McDraw went down off the bridge, he beckoned the Purser up. "That old fool's philosophy jars on me a bit just now, Horrocks," he said.

"I don't think the philosophy is more than skin-deep, sir," said Horrocks. "His eyes were full of tears when he came down the ladder. Anything wrong with McDraw's engines goes very near to McDraw's best feelings. At a rough guess, I should say he feels this mess-up more than any of us, and that's saying a good deal, because, personally speaking, it seems I shall be due to pay $300 hard cash, not to mention handing back $500 I've pouched already. Heaven knows where I'm to find it."

"I shall owe you $250, too, and I'm afraid you'll have to wait for it. We're that hard up at home I hardly know how to turn. My wife, poor girl, and her sisters, are always dinning into me that I ought to make more, and I suppose they're right. But this job here doesn't look like doing it. Probably all the officers in the ship will get reduced or fired over this smash."

"Probably," said the Purser gloomily. "That's our Mr. William Arthur's way. He thinks that if you sack officers every time one of your boats has a smash, you don't have so many smashes."

"In a way he's right."

"Our Mr. William Arthur's a splendid man of business," said the Purser, with reluctant admiration. "He always makes a point of hanging somebody if anything goes wrong. Pity they don't try that game in the Navy."

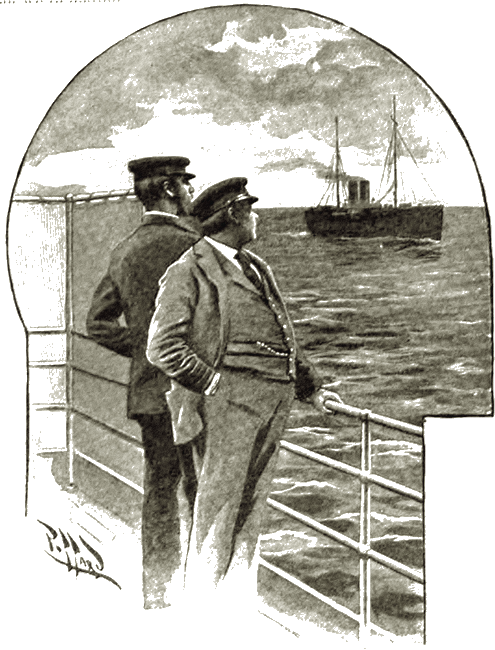

"You let the Navy alone, please, Mr. Horrocks," said Clayton, with sudden temper, and the Purser civilly said "Yes sir," and remembered too late that Clayton was an E.N.B. man, and absurdly touchy about the prestige of his service. "That steamboat that's coming up looks to me like an old tramp. Not likely to be of much use to us, sir."

"Two thousand five hundred tons," said Clayton, looking at the oncoming steamer, "and if she isn't exactly flying light, she's precious little cargo in her. Just enough coal to see her home, and not even enough over to fire the bogie in the forecastle. She'll offer to report us."

"She's precious little cargo in her."

"Then there'll be some big gambling amongst the under-writers when she does get in. I suppose with all this mob of passengers, we'll be worth a million."

"All that," Clayton admitted. "I wonder," he said drearily, "will we be picked up? We're in the steam lane now, but the weather's not over clear, and we may drift out of it in a day."

"Every steamboat in the North Atlantic will be on the look-out for us, if we aren't picked up inside of a week. We're not a poor wind-jammer or an old tramp. We're far too valuable a plum to be neglected."

"Well, you can impress on the passengers that we shan't sink, whatever the weather is that comes, that's one comfort."

"And we shan't starve, notwithstanding the crowd on board, under a month and a week at full rations. That's the blessing of one of the Company's grand-motherly regulations about carrying extra stores. I used to think it a fool regulation before."

Captain Clayton was watching the other steamer, which was just being brought to a standstill alongside. "By Jove, Purser, but the skipper of that old water-pusher yonder handles her smartly. What steamer is that?"' he hailed.

"This is the Ambleside, Captain Clayton."

"Coronet, of Whitby, Captain Crump, New York to Liverpool in ballast. You're a goodish bit by the stem. Captain. Have you happened an accident? Can I give you a pluck in anywhere?"

"Broken shaft. But if you're going homewards you'll not have coal sufficient to tow us."

"Got coal enough to tow you to St. Petersburg, Captain," shouted the man, and was instantly checked by a companion who was with him on the tramp's bridge. The pair of them had some hasty talk, which could not be heard from the liner, and then in a grumbling tone, he sang out: "Well, anyway, I've enough coal to pull you into Queenstown, and I guess that'll be all you'll want. Now how much am I going to get for my salvage?"

"No use our going into that," Clayton hailed back. "Whatever bargain you and I made, the courts would be called in ashore to settle up the figure. If you think you can tow, the sooner you get started, the better for both parties. If not, there's a Blue Moon freight boat due here in about half-a-dozen hours. We're right on her track."

From the Ambleside they saw Captain Crump's companion seize him excitedly by the arm, and Captain Crump impatiently turn to listen to another conversation which was beyond their earshot. "Well, I've said I'm quite ready to tow you," he bawled at length. "Will you send me your rope? And say, I've a new thick wire that will most probably beat anything you've aboard there for towing. We'll want something that'll hold presently. I see the glass is falling, and there's a breeze coming away. We shall put a big strain on what we tow by."

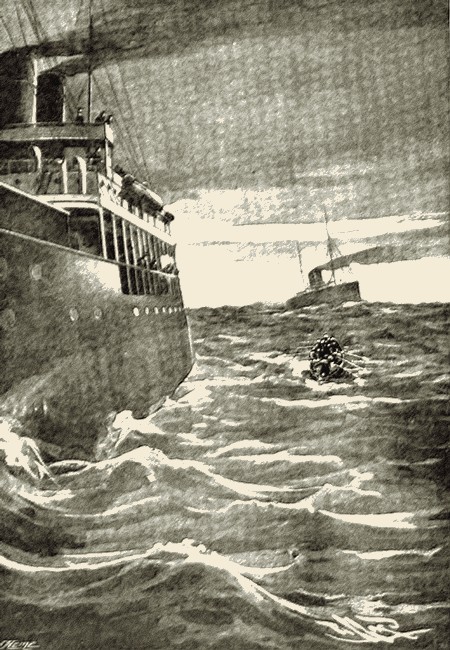

The tramp steamer began to bustle with ragged men and the yell of orders. The liner preserved her dignity even in this time of stress. With her abundant officers, there was at least one to look after each knot of working seamen, and as all were highly skilled specialists in their profession, each knew exactly what to do, and was ready at the least nod or gesture of a superior to do it.

The passengers had turned out by this time, and were watching anxiously. The lack of noise or bustle impressed them. They saw a lifeboat, maimed by a life-belted crew, drop from the davits and become the plaything of violent green waves. Oars straggled out from her sides, and she crept away over the shifting hill and dale of ocean, and the passengers felt comfortable and secure through contrast between their own case and that of the men who were carrying the line across to the rescuing steamer.

The lifeboat crept away over the shifting hill and dale of ocean.

Mr. Horrocks drew a happy parallel. "Looks small, doesn't she, that lifeboat? But let me tell you she's more tonnage than the packets that Columbus and the Pilgrim Fathers and those old people used to cross in. Let me tell you, too, you're still in luck's way for comfort here on the old Ambleside, even if she has chanced to stumble on a bit of an accident. If she'd been one of those light-plated foreign boats, or one of the other lines I could mention out of Liverpool—you'd all be swimming this minute, or drowned. It's only a stout-built boat like this that could have stood the shock she's had. But as it is, things'll go on just the same as usual, except that I'm afraid there won't be strawberries down on the menu every day for dessert. I'll own up frankly we may run a bit short of strawberries. But there's lashings of everything else —including breakfast, which is now ready. I say, good people, the gong's gone for breakfast. Am I going to eat it down there all by myself?"

The more hardened of the passengers went down to breakfast; the more curious, and the few who were nervous, missed that meal and watched on whilst the Coronet steamed ahead, and tautened on the wire till the heavy liner surged along reluctantly in her wake. They were annoyed, many of them, at being made to miss some of their appointments in England and Europe; they were madly thrilled, some of them, at being on a steamer that had 'broken down" in mid-Atlantic, but none of them were in the least degree terrified, which speaks a good deal for the consistent teaching of Mr. Horrocks on the text of "Nothing could sink in the Ambleside."

Mr. Horrocks himself, however, was the uneasy man; and deep down in his massive breast there smouldered a suspicion that this mishap which had befallen the Ambleside had been invited in some considerable measure by his own thoughtless act. It was only a suspicion, to be sure, because he could not be certain that it was his acquaintance, Mr. Cragie, he had seen prompting the tramp steamer's skipper on her bridge.

The man had worn a peaked cap drawn down well over his eyes, and a muffler pulled up high above the collar of his coat. He was all but unrecognizable—"still, there was a something about him which tried hard to betray his identity, some small characteristic trait which could not be eliminated by disguise, and the Purser hung about the decks glaring through a pair of binoculars, trying to make suspicion into a certainty.

In lesser degree Clayton and McDraw also had the glimmerings of uneasy theories that the Ambleside had not come by her ailment merely by unaided chance; and though each had so slender a groundwork for the idea that he was afraid to share it for fear of ridicule, each hammered at his clue with a mind that was savagely eager for retaliation.

But it was the Purser who finally brought together the threads of suspicion into something that the three of them were pleased to consider certainty. Cold head gales and heavy seas made the towing tedious, and the weather bitter wet. But Mr. Horrocks exposed his portly form to the elements, though he had all a purser's preference for the warmth and comfort of the smoke-room and saloons, and sought across the tumbling seas for a sight of Cragie somewhere on the other steamer. And at last he was rewarded. Cragie appeared on the Coronet's poop, unmuffled and plain for all to see.

The day was thick with driving sleet, and except for the officers and men of the watch, the Ambleside's decks seemed deserted, and Mr. Horrocks was chilled and moist. But a glow went through him when he thought he saw a way of handing along those pocketed dollars to Rock's Orphanage after all, and he stepped briskly up to the chart house to lay his suggestion in the proper quarter.

He was bidden to come in in answer to his knocks and found there Captain Clayton in conference with his chief engineer.

'Well, Purser?"

"You remember that bet I told you about in New York, sir, with a person who said his name was Cragie?"

"Worse luck, yes."

'Well, Cragie excused himself from crossing with us, sir, because he said we should land in Liverpool too late for his business; said he'd have to take the Blue Moon boat, which sailed three days earlier."

"I remember."

"It seems Cragie lied. He's on that old tramp that's got hold of us ahead. You'll remember a man on the bridge prompting her skipper when he first hailed you? I'd my suspicions of him then. I've been watching for him ever since. He's been keeping very carefully out of the way. But just now I've seen him staring at us from the poop—gloating over his catch, I should say he was—and I'd swear to him anywhere."

"Yes?"

"What I want to know now, sir, is, first, why did Cragie force that bet on me, and second, why's he here?"

"Hear, hear," said Clayton, and thumped his fist on the chart-house table. "And what I want to know is, why's that tramp's skipper got more coal in his bunkers than's enough to carry him home? He's coming from New York, where steam coal's dear, to Liverpool, where it's cheap. It's contrary to reason that he should carry more back than would see him across. And there's another point. What did he bring along that hawser for that he's so keen on our using to tow with? It's brand-new, it's out of the way thick, and let me tell you it's an expensive length of rope. We're about as well fit out here on the Ambleside as any boat I was ever on. I'm denied nothing for her by the shore superintendent that my Chief Officer cares to indent for, but we don't carry a wire like that. And yet this rotten old tramp comes along with a coil in her boatswain's store all handy and useful.

"Both that and the coal are bang in the face of probability, but I'll not say they mightn't happen singly. There are amazing fools in this world. But when they come both together as they do here, it's clean past foolishness, and gets into a kind of superior wisdom that seems to spell something very like knavery. What do you say. Purser?"

"Looks to me, sir, as if somebody must have figured out this breakdown to a tolerable certainty. It may be Crump, it may be Cragie, or it may be someone else, but I put my money on Cragie all the time. This Coronet's pace isn't anywhere equal to ours; she must have started at least two days ahead to meet us where she did, and yet, as we saw for ourselves, she came up out of the sea at the exact moment when we broke down, all ready and hungry to lick up the salvage. We're a big thing to go for."

"The fattest there's been floating about this Western Ocean this ten years," said Clayton.

"The only thing where the plan doesn't seem to hang together's here. If Crump and Cragie brought out the Coronet to pick. us up at a given spot in the N. Atlantic Ocean, how the blazes did they know we'd be kind enough to break down there? I'm no mechanic, but I should say you can't figure out the breaking moment of a shaft by a rule of three sum. What do you say, Mr. McDraw?'"

"I say, sirs, that I'm vara pleased to hear your theories," said the old man.

"Yes, yes," said Clayton testily. "But we haven't got at anything tangible so far."

"I was going to obsairve," said the Chief Engineer, "that I've theories o' my ain, scores of them, but till now I've kept them to mysel'. We're a cautious nation where I come frae, Captain Clayton, and no' wishfu' to be heckeled at for ower imagination."

"You've quite a reputation for it."

"Aweel, my chief second, that was on watch when the accident happened, put a tale into my ear about guncotton. Says he: 'Mr. McDraw, there was gun-cotton fired in that shaft tunnel to cause the break.' 'Stuff,' said I, not because I misbelieved him, seeing that he's a countryman o' my own, an' no gifted wi' imagination, but merely to hear his further arguments. 'I know what I talk about,' says he. 'When I was in the Chilian Navy I kenned fine the smell of fired guncotton an' its pheesical effects.' 'Then why,' said I, 'did I no catch the stench of it mysel'?' 'Because,' says he, 'when you came to the engine-room the shaft-tunnel was pouring out sea water like a six-foot sewer, and you were ower thronged wi' screwing down the slide door to think about a trifle o' bookay.'"

"It's beginning to fit together," said the Purser.

"But ye've no real evidence," said McDraw.

"But ye've no real evidence," said McDraw.

"We shall have to wait till the boat's dry-docked," said Clayton. "If there's been guncotton used, the marks should show plainly enough then."

"I'll no' think it," said McDraw. "Ye see it's this way. A sma' charge is all that's needed. Once you lift or depress a revolving shaft an inch or so out of the true, it does all the rest of the breaking for itself. It so to speak threshes round and devastates the surrounding scenery, if one may use a poetic seemily; and my notion is that when she's docked, we shall find that the hinder end of the boat has been bashed clean to jimmy."

"That seems to knock on the head all question of definite proof," said Clayton gloomily. "The most we seem to get at is what the Board will, call 'Negligence on the part of the Chief Engineer in not having the shaft-tunnel more carefully inspected.'"

"I'd thought of that same mysel',"' said McDraw drily, "and it made me chary about speaking about the matter, except as I am doing now without prejudice and among friends. Ye'll note I'm just talking to Clayton and Horrocks. In my formal report of the matter to Captain Clayton, I wrote what I knew and could see, not what I might guess. I'd in mind that the Town S.S. Company underwrite most of their boats' risk in their ain office, and will have to pay for most of the cost of salving us out of their ain pockets."

"Our Mr. William Arthur's bound to take it out of some of us if he has to fork up," said the Purser. "But at the same time if we can so contrive that there's no bill sent in for this bit of salvage, he'll be content not to ask too many questions. He's a splendid man of business. And he's not ungrateful; he'd certainly give us a rise all round if it came off."

"Well?" said Clayton.

"I'm quite satisfied with what we've found out as a start. Remember that Cragie didn't go into this business without quite convincing himself that he could carry it through without being dropped on. He's made one or two trifling mistakes which we've got hold of, and we flatter oursel's we've pieced together more or less of the whole yarn. We haven't done that yet. For instance, we haven't yet found out how the guncotton was worked. Was it put aboard in New York, with a clock-work 'devil' wound up to set it off at the right time? Hardly, I think. Has Cragie an accomplice in one of our greasers or stoke-hold hands who could slip the thing in place with a time-fuse at the right moment? Can't say. But I believe I know who can tell, and we'd do best to. go to the fountain head."

"Meaning Cragie?" said Clayton.

"Yes."

"But he wouldn't speak."

"He would if he was made."

Captain Clayton drew a long breath. "And we three call ourselves respectable men!"

"Yes," said Horrocks, "and I personally should continue to do so after this little event. I don't advocate putting Mr. Cragie to the question in the public streets. I should suggest a private room, a pair of irons, a handkerchief to stuff in his mouth, so that he couldn't squall, a fire lit in the grate, and a poker between the bars. I believe he'd 'weaken when he saw we meant business, and if he didn't—well, so much the worse for him. We should have to see it through."

"He doesn't deserve gentle treatment, certainly."

"The man's a common pirate, no less, and he must take what treatment he can get. We don't want vengeance so much as our own profit. I should say our best way would be to compound with him. He must guarantee not to take a penny in salvage from the company and we'll give him a promise not to prosecute."

"That seems all right," said Clayton. "And the bets are to be cancelled? I simply can't pay out that $250 for the moment."

"Well," said Mr. Horrocks, "I should say that the money which has been passed already should be retained by present holders by way of a fine."

"It seems to me," said McDraw, "you're going ahead ower fast. First catch your hare,"

"I can't afford to let him slip," said Mr. Horrocks. "You may think me a savage over what I've proposed, but I've my reasons for it."—"Any living creature can be a savage," he told himself, "when it is defending its young." And it seemed to him he had either to defeat Cragie, or be content to be mulcted and see Rocks' Orphanage suffer.

Indeed, in all this business which followed, the stout Purser was undoubtedly the moving spirit. It was he who waylaid Cragie in Liverpool, pretending to have known nothing of his having crossed by the Coronet, but letting the man suppose he took it for granted he was one of the last Blue Moon boat's passengers. It was he who callously betrayed the man with drink, lured him to a room in lodgings where no questions would be asked, left him in irons to become sober and nervous, and then brought up the Captain and Engineer to add to his informal court.

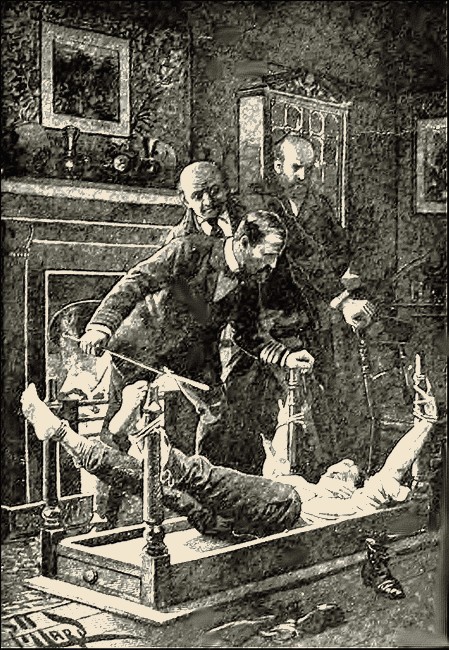

Cragie's boots were stripped off and the soles of his feet bared; a handkerchief was tied over his mouth so that he could not make outcry, and the poker was taken red-hot from the glow of the fire. The points of the count against him were recapitulated one by one, and he was invited to fill in some of the blanks. They did not want full confession from him; they did not want him to inculpate anybody else; but they desired a written assurance that he would not prefer any salvage claim against the Town S.S. Co. on account of their liner the Ambleside, and, failing that document, they were prepared to make a certain unpleasant union between the red-hot poker and part of his anatomy.

The poker was taken red-hot from the glow of the fire.

Now the exact manner of Mr. Cragie's subjugation is hidden from me, as Mr. Horrocks flatly refuses to dilate upon it. But that a full and satisfactory document was left behind when the man limped out of the room, I do know, and I have it also on good authority that the three who were left felt sick and shaken, and went out to the nearest licensed house for brandy.

As for Cragie, it does not seem that he deserves much pity. He was merely a vulgar pirate, the lineal business descendant of those broad-buckled, many-pistolled rascals that our grandparents used to hang in chains, when caught, with a coating of tar as a preservative. And really, on the other hand, Rocks' Orphanage, whatever be the value of the mixed motives of its founder and patron; is an institution which does a considerable amount of good.

The redoubtable Mr. William Arthur probably felt surprised when so fat a claim for salvage was limply withdrawn. But he expressed no regret, and he was too good a man of business to exhibit surprise. He even, on a hint being given him, forbore to ask unnecessary questions, but stuck to the steamer's dry routine, and discovered that her Captain, Purser, and Chief Engineer had behaved exceptionally well under very trying circumstances.

It was not the custom of the Firm to make promotions from boats which had met with bad luck; but the Ambleside would have to be laid up some time for repairs, and he did not intend to have any of the Firm's servants drawing pay for no work. So as a new boat had just being added to the line, they could go and run her. She was bigger than the Ambleside, and they were going to christen her the Leeds. Oh, yes, and pay would be in proportion to tonnage. Good morning!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.