RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Pearson's, August 1900, with "The Derelict"

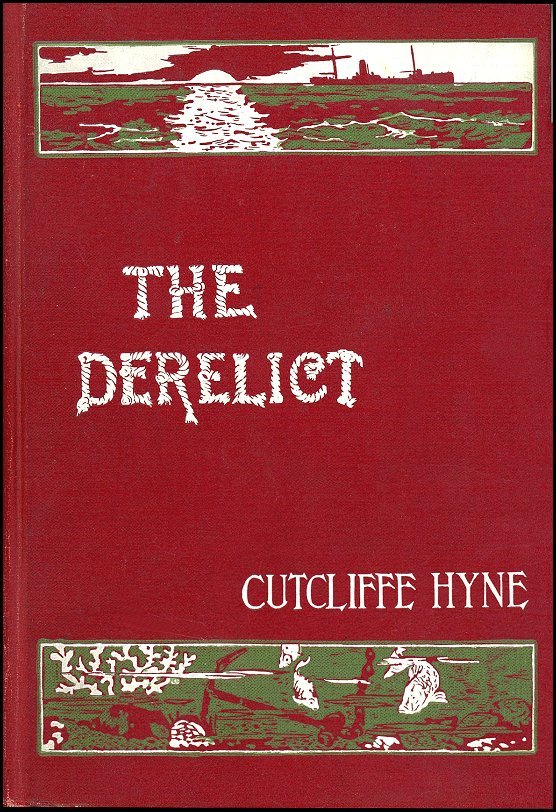

The Derelict, Lewis, Scribner & Co.,

New York & London, 1901, with "The Derelict"

The Derelict, Lewis, Scribner & Co.,

New York & London, 1901, with "The Derelict"

"YOU are my skipper now," said Mr. Horrocks, "and I've got to call you 'sir'."

"Of course, you must when we're on board here," said Clayton, the new captain of the Ambleside "Discipline's discipline, and neither you nor I, Purser, are big enough to override it. But I don't know that we shall be any the worse friends for that. True, when we were on the old Birmingham, you as Purser and I as chief mate, our relative positions were somewhat different, but now even if I have taken a step above you, we can still be friends."

The Purser laughed. "I don't see why not," he said. "The billet was a long time coming to you, but that shouldn't make you uppish."

Clayton shook his head.

"No, indeed," he replied, then after a pause, he added: "Horrocks, if you only knew how I have longed to find myself in command of a big liner, I believe even you'd be astonished. A chief officer's nobody, even if he is R.N.R.; a Captain's somebody; and I've had that drilled into me every hour I've been ashore since I was married. And, of course, there's increase of pay."

"Well," said the stout Purser drily, "I hope the berth comes up to your expectations. You've no watch to keep like you had when you were chief officer, but you'll find yourself voluntarily keeping both watches out of sheer nervousness. You'd no truck with passengers before, but you'll see presently what a joy and a blessing they can be when they are in the mood. A passenger who gave me a tract when he boarded the boat has been at me already about you.

"He said, did I think it safe to cross with a Captain who'd never commanded the boat before? Would you know the road? If you failed to find New York Harbor, would you at least strike Boston? He didn't want to be dumped down in St. Johns, as he'd heard was often the habit of new and inexperienced captains, because Newfoundland was foggy, and the smell of fish made him ill. And did I think you'd keep the engines from breaking down? He'd heard that young captains were very careless about engines; they left too much to the engineers."

"You'd better tell the old chief that."

"I did, but he seemed to see nothing funny in it. I said I was going to bring that passenger down to call on him in the engine-room, and leave a few tracts. He said if I did, he'd set on a greaser to tip a can of warm oil over him and spoil his clothes. And in the meanwhile he gave me a lecture on the inefficiencies of the mess-room steward. I'm afraid there's varra sma' sense o' humor about McDraw."

"They say he's the most careful engineer in the Western Ocean trade," said Clayton, with a sigh, "and that's principally what I care about. He won't press engines much, and so he's missed a lot of promotion, and was passed over for the newer boats, but he's never had a breakdown yet, and won't if grand-mothering his engines will do it."

"Well, that's a comforting thing for you to go upon as a groundwork, anyway."

"I want all the backing up I can get now. Purser. I'm never going to return to what I was. And if anything happens to the boat—"well, I'm not going back to shore to get sacked. You know what I mean."

"Pooh," said the stout man. "'All saved except the Skipper, who went down on the bridge,' is melodramatic and out of fashion. Our company isn't one of those mean Jew companies that just run tramps, and blacklist a skipper if a Dago pilot scrapes her over a sandbar. They stick by you honestly enough if you come foul of an accident just by luck, and not through any glaring fault of your own."

Captain Clayton laughed. "I've a sort of memory that you got Irishman's promotion for a bit of a mistake just recently. You used to be on the Birmingham which was the best they'd got. And now you're with me on the Ambleside which is the smallest boat on the line, and—well, I'm a lucky man to get such a right good purser."

"Thanks. You keep the old packet going nicely, with the blue ensign wagging out behind her, and I'll see she's popular and comfortable inside, and we'll soon work up the line to the Birmingham again, yes, and past her. I'm a man that's made it my business to be liked by passengers, and they'll come to whatever ship I'm on whenever they want to cross. You must do the same, sir. That's the way for us to get on in this trade, always supposing we handle the press ashore correctly."

The Doctor came in then, and they went round the ship for inspection, and, when that was over, Mr. Horrocks thought he would go and cheer them up in the smoke-room a bit, and let those that did not know it quite understand what lucky people they were to be on board of the Ambleside. But on the way there, the tract man once more waylaid him.

"Oh, Purser," said he, "did you read that booklet I gave you yesterday?"

"Haven't had a chance yet, Mr. Steinberg. And, besides, I lent it for the time being to the chief engineer, and he hasn't returned it."

"Ah," said he, and brought another from his pocket. "Then read that in the meantime. You'll find it will give you inward comfort. Oh, and wait a minute before you go. There's another point I want to ask your advice upon. I see by the route chart you supply, that the steam-lane we're on now differs from the homeward track."

"Well, Mr. Steinberg, I'm no navigator, but I believe that that's a bed-rock fact. The homeward route's about twenty or thirty miles away from where we are now."

"That's rather a long distance, isn't it?"—he tapped the Purser's arm confidentially—But I must tell you that I am a strong swimmer, and it is my intention to take one of the life-belts from my stateroom when I make the attempt."

"Thoughtful of you."

"Of course, if there is anything extra to pay for the life-belt, Purser, I should be pleased to settle it with you now."

Mr. Horrocks was beginning to think that Steinberg was one of those people who can do with a bit of care. "Not at all, my dear sir. The fees for life-belts are always the perquisite of your bedroom steward. Pay him before you start on your swim. When do you think of leaving us?"

The man looked at the Purser sharply. Mr. Horrocks bit the end of a cigar, and blew through it carefully. "Got a match?" he asked.

"No," said Steinberg, and dropped his suspicion. "When do I think of leaving this boat? Well, that I can't tell you. But I've got a notion in my mind that she isn't safe, and I want to swim off to one of the homegoing boats, and get back to England again. I've spoken about it to Levison. He says it's quite the proper thing to do. You see, I'm a life-governor of the Porter Mines, and it's due to myself that I should take care of myself."

I want to get back to England again.

"You are acting most naturally," said the Purser, and made a mental note that Mr. Steinberg should be watched with remarkable accuracy.

The intending suicide on Atlantic liners is a much more common personage than the general public suppose. The sea and its mystery have the effect of developing the latent madness in some folks into active mischief, and many a man who is sane enough, and entirely capable ashore, becomes on shipboard a wholly irresponsible maniac.

As it is practically impossible to guarantee that nobody shall jump overboard unless you keep the whole passenger list in irons, steamer officers are apt to take suicides as they come, and confine their energies to keeping details out of the papers as far as may be. But if they do gather a hint that a passenger is contemplating a jump over the side, they tell off men to watch him even at the risk of overworking several already fully-strained departments.

Steinberg tapped the Purser's arm confidentially. "Oh, I say, Mr. Horrocks, you won't mention what I've told you to the other passengers?"

"No, sir."

"Because, you see, if I gave a lead, they'd guess the reason, and all be trooping after me, and the other steamer we swam to might make a difficulty about taking in so large a crowd."

"Great Washington! What a head you must have to think out all these details! Now, myself, I should never have foreseen a complication like that."

He sniggered, "Well, to tell the truth, I oughtn't to claim all the credit. It was Levison's idea. Levison said: 'Look here, old man, go off on your swim if you think it advisable, but don't talk too much about it, or else the ship people will stop you.' 'Why should they?' said I. 'Why, don't you see, if you give a lead, all the other passengers would want to follow, and then the Captain would stop the lot of you? It would never do for him to go into New York with no passengers at all. It would ruin his credit.'"

"Cute man, Levison."

"Yes, isn't he?"

"Levison coming with you?"

"Oh, no. You see, he suffers from cold feet, and he thinks a twenty-mile swim might give him a chill."

"It would. But say—is Levison some relative or partner of yours? Is he sort of companioning you anyway?"

"Well, you know, not officially. But he's very anxious about me because I'm a life-governor of the Porter Mines, and so, of course, I've got to be taken care of. They're very much sought-after things, those life-governorships."

"Shouldn't wonder. Levison in that line of business at all?"

Mr. Steinberg drew himself up. "Rather not. He's merely a director, and that's a very different thing. He'll not be made a governor till there's another vacancy, and that's not likely to happen during his time. All the present life-governors of the Porter Mines are younger and more healthy men than Levison. He eats too much. I'm always telling him so. And, besides, he will drink champagne."

"You don't?"

"Always stick to port and lithia water, mixed half and half. You get all the fun of the port and none of the gout."

"Look here, Mr. Steinberg," said the Purser, wagging a thick finger at him, "you're a man of ideas, and I want to steal some of them. Where do you sit in the saloon? Oh, I remember; down at the end of the Doc's table. Well, will you do me a big favour and shift and I'll find you a seat at mine?"

"Purser," said he, rubbing his hands, "you honour me. I shall be delighted."

Mr. Horrocks left him there, slipped round some of the houses till he was out of sight, and gave the deck steward and quartermaster strict orders to keep an eye on the man and see he did not get over the side. And then he went down below and sent about a few other instructions that might be conducive to Mr. Steinberg's health and welfare.

A Purser like Mr. Horrocks does not have a lunatic next him at meals from choice, but it appeared to him that this one had got to be looked after. It came to his memory that the Porter Mines were a remarkably big concern, and if one of their life-governors got into the water off the Ambleside, there would be a nasty splash ashore, as well as in the Atlantic.

Such little episodes are apt to reflect discredit upon a steamship line, and directors are not in the habit of favouring pursers who are so unfortunate as to lose passengers under such circumstances. It therefore behooved him to exercise care in the present instance, not only for the passenger's sake but for his own as well.

It was not for himself as Mr. Horrocks, the Purser, that he feared. As that official, his wants were small, and his private income covered them easily. But he was a man with an alias; a man who led a double existence. Throughout all his life he had carried an infinite tenderness for those wretched children of the slums in which Liverpool is so prolific, and of late he had contrived to found an Institution in a village near Chester for their maintenance and relief. It pleased him to pose as a portly local philanthropist. Down there he was Mr. Rocks, of Rocks Orphanage, a somewhat pompous personage, who was very different from the affable Purser in the Town S.S. Co.'s employ.

It was lest the power to continue being Mr. Rocks should be taken away from him, that he was so anxious.

So he thought it useful to have Mr. Steinberg near him so as to be kept posted up in his latest views; and also, it was beginning to dawn on him, that Levison's conversation was bad for his morals. He could not quite decide whether persuading a cheerful lunatic to drown himself was actual murder, but considered that anyway it was something uncommonly near it, and stood by to trample on Mr. Levison's toes in a way that would have made that diplomatist nervous if only he could have known it.

They were mostly old travellers at the Purser's table, as was only natural, and knowing that they would soon guess what was up if he did not tell them, he affected the confidential, and let them know the delicate state of Steinberg's health, and so persuaded them all to bear a hand.

The Doctor got to hear about it from one of these, and came to Mr. Horrocks, and said he supposed he'd better take over Steinberg into his own charge, rather hinting that the Purser might find him above his capacity to deal with.

There was a smouldering enmity between Mr. Horrocks and Dr. O'Neill, and as the Purser detected in this proposal a scheme on the Doctor's part to make fees out of a profitable patient, he replied curtly enough that he felt himself quite competent to manage this dangerous passenger.

The men at the Purser's table entered into the spirit of the thing with zest. They were busy commercial men, all of them, who did, perhaps, their six crossings a year, and to whom an Atlantic voyage was holiday and time for relaxation. So they were quite open for a frolic.

But at the same time, the talk as a whole tended towards the gruesome. Steinberg, it seemed, had made a study from his youth up of the literature of Atlantic disaster, and as the others were willing to humor him they had the full history of all the accidents which actually had happened, which might have happened, and which could not possibly have happened since ever the seas were first poured out. They had some fine active liars amongst them at the Purser's table, and they competed for the palm with spirit.

"Yes, but look here," Steinberg would begin every now and again, "with inexperienced Captains like—"

And then Mr. Horrocks would say "S-s-sh!" and the table would cough, and Steinberg would collect himself, and wink at the Purser, and go on pleasantly. He only wanted a little humouring to keep him straight, and when someone suggested that it was cruel of the Purser to play with the fellow's infirmity, he bade the objector look at the other alternative. "I might have locked him up in his room, and then we'd have had a howling, scrabbling lunatic disturbing half the ship, and he would probably have ended up by choking himself painfully to death with the soap. Sounds a bit unlikely, doesn't it? But I knew that soap trick actually done once by a Third Class, and saw the beggar when he was stiff, and I can tell you he wasn't pleasant to look at."

And then Mr. Horrocks would say "S-s-sh!" and the table would cough.

But with all the badinage, there was one thing the diners at the Purser's table were quite solid on, and that was the strength of modern ships, and the Ambleside in particular. Short of trying to hit the Tuskar Rock out of the water, or having them rammed fairly on the broadside, you could not sink them they said.

"Remember how the 'What's-her-name' went ker-smash full speed into that iceberg?" said Van Sciach. "Lost a few feet off her bows, and a man that I know that was in the smoking-room got a poker hand so mixed up by the shock that he showed four queens, and won the biggest jack-pot of the voyage. But there was no serious damage done, except that she steamed into a port a day late, and the company had to stand another three meals gratis."

"Iceberg's nothing," said Bisbee. "Remember the Blue Cross boat working in for her wharf the other day in the East River? She'd a bit too much way on, and didn't answer her helm quick enough, and she sliced off the corner of that quay as though it was so much margarine. Did she sink? No, sir. Didn't crumple a plate. Scarcely so much as scratched her paint. 'N't that so, Horrocks?"

"Gospel," said the Purser. "The Lord help anything that gets in front of one of these packets when she's got a move on her."

"Yes, that's all right," said Steinberg, "But you've all missed out the thing that's going to make the biggest steamer smash of this century. How about an old wooden timber-ship, packed with lumber, dismasted, and lying square across your track, and just awash? Given it was an ordinarily black night with no moon out to shine on her, no mortal look-out could see her till she was hit, and then that's the time where the steamer's big momentum the Purser was telling us about would come in. She couldn't cut through that loosely packed mass of wood same as she could through ice or a granite wall, and it would just rasp off half her bottom before it was done with her, and then she'll sink before the crew had time to fight for the boats."

"Skittles," said the Purser. "She'd cut through it like a box of matches."

Steinberg nodded his head. "So you say. But it's got to be proved. And it's my belief that the Ambleside will test it." He leaned forward and wagged his finger solemnly at the table. "Do you know, I've dreamed every night since I've been on board that she would smash into a timber-laden derelict this trip, and that's why I've been so anxious to leave her."

"Why be in such a hurry?" asked the Purser. "You'll find it much more comfortable to go off in one of the life-boats when the time comes. If you'll say which boat you'll choose, I'll see she's stored with a few bottles of port and a case of lithia water."

"And it'll be a sight more sociable," said Van Sciach, "than cruising in the Atlantic by yourself."

"Ah, but you haven't foreseen," said Steinberg, "like I did in my dream, what a rush there'll be for those boats."

"Guess you dreamed wrong all the way there, sir. This packet isn't German, nor is she French." He turned and grinned at Mr. Horrocks. "You can tell that by the grub. But, on the other hand, passengers hold an option on the life-boats. And if by chance they are wanted, Horrocks and the rest of the ship's company will see us all nicely tucked into the best, with a feeding-bottle and a clean pair of cuffs for each passenger, and then if they've time and there are boats left, they start fixing for themselves. But not before. That's American and English fashion, Mr. Steinberg, and don't you forget it. I guess it's pious thoughts like those that help down every meal that I have on these boats. Otherwise some of the grub might stick in my throat."

They switched off then to talk of food and accommodation on the Hamburg and Havre boats, and followed the general theory of the Western Ocean that those companies do treat their passengers considerably better than the English think needful. But Mr. Horrocks was not going to be drawn too much.

"All right," he said, "go by the Germans if you like them best. But please remember that we contract to feed and carry you all the way across, and they only guarantee to do it as far as they go. And I guess they save by now and again only going half-way."

"Gentlemen," said Bisbee, "the Purser! May nothing ever choke him!" Which toast they all drank very pleasantly.

Then happened one of those strange coincidences which look so unlikely, but which life is so constantly yielding up.

"I dreamed last night—" Steinberg was beginning again, but what he dreamed they had to guess. Probably everybody who had been within earshot of his previous talk did guess too, and got a bad shock to the nerves. On a sudden, all the glass and silver and crockery shot along the tables of the saloon as though it was alive; the paint shelled off from the deck above and fell in little flickering clouds; and from the night outside, and from all through the ship, there came noise enough to supply a battle.

For the moment the passengers were dazed, and made feeble grabs at their plates and glasses, or instinctively picked off the food that had fallen on to their clothes. But this was all the affair of a moment; and when that moment ended, there were screams, and yells, and shouts, and curses, and all the makings of a very ugly panic. All got out of their swivel chairs, and half of the people in the saloon commenced to rush for the companionways.

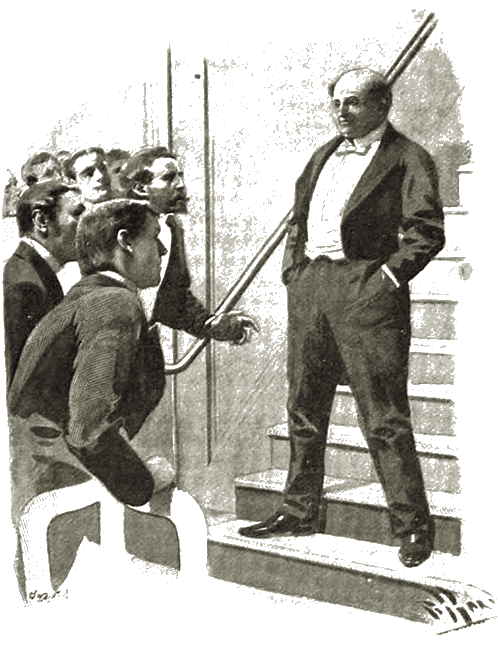

Now, at the first alarm, the Purser had instinctively turned his head, and was just in time to see Captain Clayton leave his chair as though the shock of the cascading dishes had shot him out, and disappear up the companion with the speed of the quick man in the pantomime. He had gone to take charge on deck, and Mr. Horrocks was left in command below. So the stout man strode smartly across, and got on the bottom step of the companion before the rush had fairly started, then put his hands in his pockets and cocked his big, good-humoured head on one side and laughed. He was full in the glare of the electric lights, and all the passengers looked up and saw his portly figure, as he intended they should; and the rush broke and presently stopped.

Then they began to ask questions.

"What's happened?" "Is there any immediate danger?" "How long before we sink?" "Shall I go to my room and get some things together?" "Are they sending up rockets yet—the Captain ought to be made to, if he hasn't." "Will the stewards provision the boats, or ought we to put stuff in our pockets?"

"What's happened?" "Is there any immediate danger?"

"My dear good people," said the Purser, "I'm sorry you've had a bit of a shock, but there's not the smallest danger, believe me. If there had been I should have been told officially long before this. But as things are, I do wish you'd go back to the tables."

"I want to go on deck first," said someone.

"I daresay. And there you'd stay for half an hour watching the rain, and then come down again to finish your dinner and complain that it was bitterly cold. Now, please do consider my feelings. When passengers complain about their meals I'm the man who's harrowed."

There was a bit of a worried laugh at that, and a long lean Yankee drummer from the Doctor's table backed up Mr. Horrocks capitally.

"Yes, that's all very well, Purser, but you don't simmer some of us down like that. I had a glass of claret flung over my nice clean shirt, and what I want to know is, will your company pay the laundry bill?"

There was another laugh at that, and the passengers began to settle back in their places.

"Sir, I'd like to have your answer," said the drummer.

"If you forward your application in writing, it will receive full consideration within the next ten years," said the Purser, and the passengers roared.

It was poor enough wit, but their nerves were a bit raw just then, and anything tickled them. If the Purser could joke, surely the danger could not be great. Jennings, the chief steward, backed him up finely. He got his crew in hand again—they had been just as scared as everybody else—and they set about putting things shipshape on the tables.

"Ladies and gentlemen," said Mr. Horrocks, "there have been a lot of bottles spilt, and the boat is fined for being careless. If you'd kindly give your orders to the stewards?"

Half-a-dozen voices shouted out the obvious retort. "Better simplify matters and serve out champagne all round. That's what we take just now if there's going to be free wine." They were getting their coolness back finely now.

Van Sciach rubbed the Purser's fat shoulder as he was going back to his place. "It's a bad smash," he murmured, "isn't it? You can tell she's down by the head already. Look at the slant of the floor."

"I know no more than you. The Skipper will send if we're wanted. Don't let them talk about it here more than you can help."

"Oh, I'm not going to make a fool of myself," said Van Sciach.

Mr. Horrocks had given the wink to the chief steward to go and quieten down the Second Class passengers, and if the chief steward's methods were likely to be a trifle rough, well, so much the worse for the Second Class. The main thing was to keep them from stampeding. Anyway, if they complained ashore it would not matter seriously. Second Classes seldom amount to much, even with the newspaper men. As for the Thirds, well, any officer or quarter-master on deck would know enough to keep them from coming up till they were invited.

But the First saloon was the critical place from the Company's point of view, and the Purser knew he had his work cut out to keep them quiet, and at the same time pleased with themselves. But with his cool assurance, and his fine brazen affability, he shamed and humoured them out of any tendency to panic.

Presently a quartermaster came, and stood for a moment at the foot of the companionway nursing his cap and fingering a scrap of paper.

A steward was on to him in the instant. "The Purser, you want? He's there."

The fellow came across to Mr. Horrocks quickly enough. "The Captain sent this, sir."

Of course the saloon could not hear what he said; but it did not take much art to guess that the man had come down to deliver verdict as to whether the ship was to sink or swim, and they would have been more than human if they had stifled their curiosity. And as it was, the chatter snapped off as short as one might break a wine-glass stem.

It did not take the Purser long to read Clayton's scrawl.

"That was a derelict we hit, and it splayed old Harry. We smashed clean through her, and it looks as if she's smashed off half our bottom. Keep the passengers quiet. I've got boats swung out ready. But I'm not going to let them leave her while there's a chance she can swim. It's life and death for me, this, so keep them quiet and down below."

The note was not signed, and you may say it could have been more clearly put. But it told Mr. Horrocks what he was wanted to do, and he did it without another thought. Each of all that large mob of passengers was watching him with eyes that had a whole life behind them, and so there was no room for him to make a mistake. He knew words alone would not satisfy them. So he folded the paper and put it in his pocket-book, and delivered himself of a really good sigh of relief, right from the bottom of his ample waistcoat.

"Well, that's all right," he said. "There's no big damage done. But you may thank your stars, ladies and gentlemen, you're on a strong, well-found steamer, and have a Skipper like Captain Clayton. We've hit a derelict," he explained, and told them what that was, and how the whole thing had occurred, spinning out the yarn purposely. "And there's only one thing the Captain wants you to do," he finished up, "and that is to let him and the crew have the deck to themselves to-night. The men are working at getting things shipshape again, and it's a dark, rainy night, full of wind, and, if passengers were about outside, there's a chance they might get injured. Now, I should suggest that we get up a scratch concert right here in the saloon, and, if the ladies don't object, we'll break through the usual rule, and make it a smoking concert."

Steinberg, whom, to tell the truth, he had forgotten, tapped him on the arm.

"Purser," he murmured, "you'll excuse my staying, won't you? I think I'd like to be off now. I'll square up with my bedroom steward for that life-belt."

"Why so much hurry?" said Mr. Horrocks. "There isn't the least use in going just now." He shut his eyes and pretended to work out a sum. "No, not the least use. The Blue Cross homeward boat is the only one in this neighbourhood, and she isn't due for another eight hours yet. If you went off now you'd only have to wait about for her."

"Sure? You aren't humbugging me?"

"Mr. Steinberg," said the Purser stiffly, "it's my duty, as an officer of this boat, to give information to passengers when it's asked for. And I know my place too well to tell them anything that won't be of use to them."

"My dear Horrocks, believe me, I didn't mean to be in the least offensive."

"All right, then. Let's say no more about it."

"Only, you see, I know my scheme for leaving this steamer is a little out of the ordinary, and once or twice I've not been quite sure whether you liked it."

"My dear sir, your wishes are most natural."

"I really think so. You see, I dreamed of this collision every night since we left Liverpool, and here it is. And I dreamed of the horrible scramble there'll be for the boats when she sinks. So naturally I want to have swum a good distance away before the rush comes."

"Want the Purser?" said a steward. "He's over there at the end of that table." And up came another quartermaster with a second note from Captain Clayton.

"Send stewards to provision boats. Keep passengers below. There's a bad sea running; it will he a poor chance."

"All right" said Mr. Horrocks. "Hand that to Mr. Jennings and ask him to attend to it for me. Now, you stewards, be quick and have those tables cleared, and then get out of the saloon."

Probably no man ever had much more keen curiosity to slip out on deck and see how things exactly were than Mr. Horrocks had just then; but he did not see his way to it. It was his duty to keep the passengers well in hand, and so far he had succeeded; but he did not flatter himself that they would keep good if he did not stay too to humor them.

It was not exactly that he dreaded getting drowned; that detail did not occur to him once. But, as most men's minds do on these occasions, Mr. Horrocks' thoughts went off to his orphanage in Cheshire. By an odd inversion of thought, the personal danger of Mr. Horrocks, the Purser, did not worry him in the least, but the thought that Mr. Rocks, of the Institution, might be cut off from his usefulness and glory, made him wince and curse luck and Captain Clayton under his breath with unbenevolent point and vigour.

It was Captain Clayton who made him nervous. It was a case, as Clayton said, of life and death to him, and certainly it was of professional life and death. Let him lose this boat, and he would never get another sea billet as long as he lived. The Firm would blacklist him to all eternity, and so for that matter would Lloyd's. And so, where an older captain, with more standing to fall back upon, would say, "Out boats, leave her," Mr. Horrocks knew that Clayton would hang on a lot longer than he ought to, and probably make a dreadful disaster of it.

It did not take much knowledge even for those below to see that the steamer was in a bad way. The floor listed till the after-end of the saloon stood up above the forward-end like a mountain back above a valley. The forecastle head must have been pretty nearly under water. They knew that everything must be holding by one slender bulkhead, and if that gave, down she would go like a stone. Then might come Steinberg's "terrible rush for the boats" unless Mr. Horrocks was careful, and the thought of the disgrace of that —from the professional point of view of a Purser—made him hot with foreboding.

However, when all was said and done, Captain Clayton was the man in supreme command, and in moments like these there was no room for argument. Sink or swim, the responsibility was the Captain's, and the Purser recognized his limitations and set himself to his task of keeping the passengers cool and satisfied to the best of his art. If word was given, he had all arrangements ready in his mind for drafting them out in batches for the boats without hurry, bustle, or panic; and, on the other hand, if the danger did not come to that climax, he was doing his best to keep them amused and satisfied, and to prevent them from making ugly demonstrations in the papers when they got ashore, which might do harm to the Town S.S. Company.

So whilst the executive on deck worked for the lives of all by shoring up the plates and stringers of the buckling bulkhead, Mr. Horrocks in the First saloon played the genial master of ceremonies, and organized a scratch concert in aid of the Sailors' Orphan Home.

The usual bed hour slipped by and was ignored. People think little of temporary rest when they expect shortly to be drowned. But when three o'clock passed, and there was no further message, Mr. Horrocks began to remember that to keep his passengers up any longer would be an open confession that the boat was in danger, and that presently they would see this, and, being very tired, would probably grow nervous and troublesome.

So in his pleasant way he announced that the evening was at an end, and the passengers went to their rooms; and although there was little undressing that night, there was no trouble, and no more questioning.

In Mr. Horrock's own words: "At an awkward time like this, First Class passengers are the most reasonable people imaginable, if only you treat them right. But, of course, they want a man over them who does understand how they should be handled. They take it for granted that the ship's officers are doing their best, and they don't handicap matters by interference—once they have simmered down. It's the Third Class crowd you can't trust, and to make sure of them at times like these, we clap on the hatches, and leave them shut up below to scrap and squall as they please. They can't expect too much individual attention on a £3 fare, with everything found."

The Purser got out on deck at last, and had a chance to see for himself how things were. A couple of big cargo lights were slung up forward to help the deck-hands at their work, and he went and stood in the glare of one of these so that Captain Clayton could see him. Presently he did this, and called for Mr. Horrocks to come to him on the upper bridge.

"She seems to be keeping afloat, sir," said the Purser.

"There's about twenty-five feet of her gone below the water-line forward, and everything depends on the bulkhead. She's full of water up to there. We shored it up from inside as well as we could, and with luck it may stand. But if a breeze springs up, or if we meet anything of a sea, she'll go to everlasting glory."

"I've kept my passengers quiet. Saw them all turned in before I came on deck."

"Good man. I suppose most skippers would have had them off boat-cruising before this."

The Purser said nothing. He knew his place, and was not going to take off any weight that belonged elsewhere on to his own shoulders.

Clayton deduced all this clearly enough. "Hang it," he blurted out, "a man does owe himself some consideration. I'm not going to leave my own women-kind to starve without a fight for it. If I take her in, there'll be nothing said."

"No, sir."

"Curse you, Horrocks, don't let off parrot answer like that. I tell you if I'd been on deck instead of at dinner it wouldn't have made any difference. The officers on the bridge, and the look-outs forward weren't looking ahead at all when it happened. And for why? Because out of the rain and the mist and the night there suddenly loomed out an old bark making straight for our broadside. She wasn't showing any lights, and they seemed all asleep aboard of her. Her people hardly woke to our whistle, and either they thought they'd clear us, or they were too much asleep to change her course. She crept on us like a big grey ghost, and if she'd hit us in the broadside, even with her slow pace, she'd have cut us almost in two.

"I guess every man on deck watched her with bulging eyes, and in the end she cleared us by so little that her foreyard scraped the rail stanchions off our after turtle back. It was at that precise moment that we flogged into the old timber drogher that's so precious nearly done for us. There's a nice healthy piece of luck for you! It seems as though the devil himself intended to sink us whether or no just then, and only got bilked by Providence and a firm of God-fearing Clydeside shipbuilders."

"It should like this to have happened to one of the other Lines."

"You've to take what's given you. By Jove! I very nearly had a mutiny here at first. The officers and the deckhands seemed to take it for granted I should leave her. Someone was even brute enough to remind me that there were 800 people on board of her, and that I was responsible for the lives of all of them, and looked like murdering the lot. But if she swims long enough, I'll surprise some of them yet, and if she doesn't—"

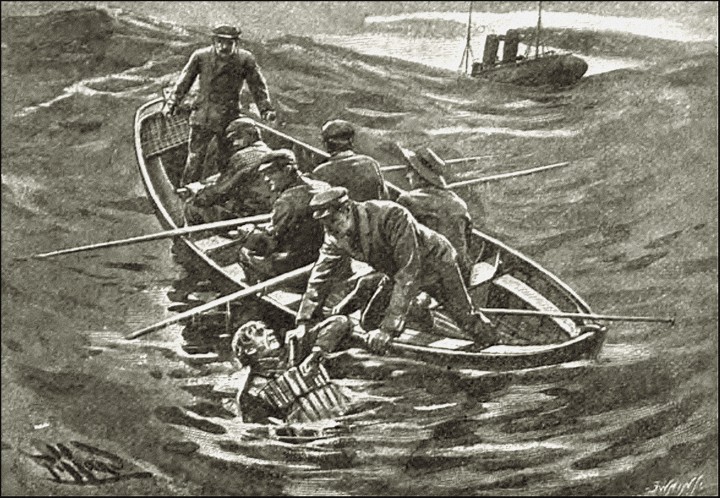

"Man overboard!" came a shout from one of the decks below.

"Away aft there."

"On the port quarter."

Captain Clayton ran over to the port side of the bridge. The Purser went at his heels.

"There he is, right in the glare of that light!"

"He's got a life-belt on!"

"He's swimming away from the ship!"

The Captain had given sharp orders to the fourth officer who was with him on the bridge, and the fourth officer had repeated them with prompt speed. Mr. Horrocks guessed on the instant who the man overboard was, when he heard the word "life-belt," but he said nothing. He did not particularly want to confess that Mr. Steinberg had been too sharp for him. A boat's crew came running up, and one of the slung-out life-boats screamed quickly down towards the water. She unhooked, shoved off, and the oars straddled out. An officer stood up at the tiller in the stem, a man stood up with a boat-hook forward. The seas hustled her about like a cork.

It was all done with discipline and precision. The chief officer ran down aft, caught sight of the man in the water, and directed the boat with a lusty voice. No one else shouted: they had been ordered to keep silence. The bowman jammed in his boat-hook shrewdly, and the swimmer protested as he was dragged in over the gunwale.

The swimmer as he was dragged in over the gunwale.

Then the boat came back alongside, hooked on, and was hauled up. "Smartly done," said Captain Clayton. "Pass that man below to the Doctor." And then he turned, keenly enough, to the carpenter, who had brought him a report from the holds.

Mr. Horrocks slipped away then, and Steinberg met him with a storm of reproaches. He was not a bit tamed by his swim. Most uncalled-for, he said, was the interference with his personal movements. But all he got out of the Purser was "Captain's orders, sir," and then was escorted down into one of the rooms aft, which was officially called the hospital, and which the Doctor used as his personal suite, the lucky dog.

The Ambleside's Doctor had his failings, or he would not have been aged fifty and still at sea; but he knew how to deal with a case like this. "Tut, tut," he said. "You've been swimming in the water at this temperature? Most injudicious, sir, unless you oiled your body first to keep out the cold, and I'll lay two sovereigns to a brick you forgot that."

"Tell, to tell the truth, I did," said Steinberg.

"Then it's lucky you came back to me, or you'd have had a chill for certainty, with pneumonia to follow. All people do who swim in the Atlantic at this time of the year if they aren't well rubbed with oil. Here, try one of my patent drinks, and see if that doesn't warm you."

Steinberg took it like a lamb, and in two minutes he was snoring.

"He'll stay like that," said the Doctor, "for twenty-five hours. You see my way of treating suicidal lunatics differs somewhat from yours. Purser. I like to make sure of them."

"Your beans," said Mr. Horrocks, and went forward again about his business. He felt very sore that the Doctor had scored over him in this matter of Mr. Steinberg.

They got steam on the Ambleside next morning, and went on towards New York at a slow half speed. The weather was not exactly kind to them; it blew fresh out of the northwest, and there was an ugly sea running, and it was the Purser's private impression that they risked foundering every mile they ran.

But all the damage was below the water line, where it did not show, and when passengers came out on deck again next morning, everything so far as they could see was just the same as it always had been. Of course boats were swung outboard, but they hung high above the awning deck, and did not show especially, and the newly filled water beakers, and the food in their lockers were also comfortably out of sight. The Purser organized athletic sports that day, and a deck quoit championship, and they had about the most exciting auction sweep on the run that he ever remembered playing auctioneer at.

Mr. Horrocks did also another thing that pleased him. He got hold of Levison and asked him to give £200 towards an institution known as "Rocks' Orphanage."

The man seemed a bit surprised at first, and was inclined to bully.

"Are you mad?" he asked.

"No, sir," said the Purser drily; "But Steinberg is. Do you want any further information?"

It seemed he did not, and he handed over the money at once, and kept out of the stout Purser's sight for the rest of the trip. Of course that was small enough fine for attempted murder, but Mr. Horrocks did not want to be too hard on the wretch—and have him refusing to give anything. He pictured to himself the good the money would do to Rocks' Orphanage, and the pleasure he himself would have (as Mr. Rocks, the philanthropist) in making the gift.

Thanks to the skill of Mr. Horrocks, the Ambleside's passengers were all a happy and contented family for the rest of the trip, and if they did come into New York three days overdue, they did not specially mind. The old boat had to be nursed delicately. She surged along with her nose in the water, and with her propeller racing as it did, she showed the pace of a dumb-barge. She carried three-quarters of her rudder in the air, and she sheered about more or less as she chose. But, what was most to the point, she kept afloat, and the other incidentals did not matter.

They got a tug to straighten her up a bit in the steering off Sandy Hook, and when they came up to the wharf, Clayton shoved her in stem first till she grounded, as there was not water enough to let her go in bows first at all.

They were long overdue, of course, and there was a lot of excitement ashore, and, in the words of Mr. Horrocks, "there were enough reporters on the wharf to populate an entire suburb in the hot place where they'll eventually go to when they die." But he was ready for these gentlemen of the nimble pencil, and he had the whole crew of them down below, and most of the champagne that was left in the ship was set on the table.

"Business first, certainly, gentlemen. But your first and obvious business is to drink to the health of our arrival," which they did to the tune of about a magnum apiece.

Afterwards, well, the Purser had got a nice compact yarn nicely typed out and duplicated, and that was all he had to tell. He refused to make any further statement, and those newspaper men would have been more than human if they had rejected all the ready-made copy.

Mr. Horrocks had made up a most thrilling story.

"Splendid ship. No real danger thanks to the masterly way in which Captain Clayton had handled her. Clayton thoroughly deserving the purse of £300 the passengers presented. Had it been a boat of any of the other Lines which sacrifice strength and construction to speed, undoubtedly all hands would have been drowned"

"But there's nothing about yourself here. Purser," said one of the newspaper men.

"Well, boys, if you will have it, there's just this paragraph more." And he distributed round the duplicated sheets.

"The passengers speak very highly of the kindness and attention they received from Mr. Eli Horrocks, the Purser, and we understand that there is a movement on foot to present him with a substantial testimonial."

"There," he said, "now you have that, and you have the general account, and you have the three 'Accounts from a Passenger,' which I wrote for you to take your choice from, and I guess you have as good a 'story' as any paper could want to print."

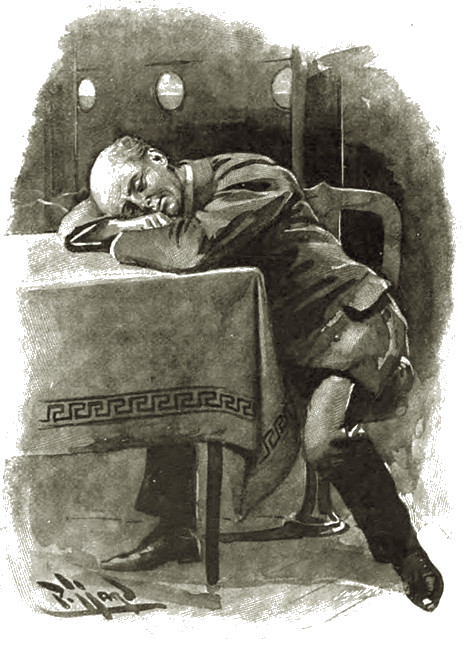

They went off satisfied with that, and Mr. Horrocks intended to go ashore and make his report to the office. But somehow his eyes got shut, and he went to sleep with his head on the saloon table, and there he stayed for eight solid hours.

The passengers were ashore now, and the ship's honour and credit had been cared for as tenderly as might be; and now that the strain was gone, there were a good many men on the Ambleside who were thoroughly worn out.

But there was a pleasant smile on the large plump face of Mr. Horrocks, the Purser, as he slept with his head on the First saloon table. He dreamed sweetly of the philanthropic triumphs of that good man Mr. Rocks, who was so much admired by the public in a certain Cheshire village, and who knew nothing whatever about the sea and steamboats.

He dreamed sweetly of the philanthropic

triumphs of that good man Mr. Rocks.

And a tear or two of pity and gladness found their way out through his eyelids and gleamed on his eyelashes as he pictured to himself the additional waifs from the slums who could be helped with the £200 which had been so skilfully extracted from Mr. Steinberg's friend, and would-be-murderer, Mr. Levison.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.