RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Pearson's, October 1900, with "Diamond Cy"

The Derelict, Lewis, Scribner & Co.,

New York & London, 1901, with "Diamond Cy"

The Derelict, Lewis, Scribner & Co.,

New York & London, 1901, with "Diamond Cy"

"MY dear Purser," said Captain Clayton, "if I thought you were smuggling, or giving help to smuggling, I tell you candidly I'd send the Customs' people a hint at once."

"You weren't always so particular," suggested Mr. Horrocks.

"Some bits of history are better forgotten. And besides, I was only chief officer then. Now I'm in command, and the boat stands for more to me than, perhaps, you'd imagine; and, anyway, I'm very jealous of her chastity. We'll have no smuggling, please, Horrocks."

"Well," said the Purser rather crossly, "you know where I dined last night, and with whom?"

"You dined with me at the Adelphi."

"You and I weren't the only people at the table. You'd got ten of a party, hadn't you, to square up for when the bill came?"

Captain Clayton set his teeth. "Well, Horrocks, my wife likes entertaining, and so do her sisters."

"What I meant to suggest was, that your wife was there. It was she that gave me the first hint that there was some stuff somebody very much wished to be helped through the New York Customs, and, 'pon my life, I thought you knew all about it too, or I'd have kept my head shut. Mrs. Clayton said she stood to win a diamond crescent, if it came off. She said she'd seen the crescent, and it was a beauty, and she mentioned that she adored diamonds. She wears a good many, I've noticed."

"Yes," said Clayton shortly. "She got them when she was on the stage. You know that as well as I do. But she has to be content with what she's got, and I trust is content. My means don't run to diamonds. It's hard enough to keep to windward of ordinary expenses."

"You've got a fine notion of spreading yourself ashore. But if it was my wife, I'd get her that crescent the cheapest way. She intends to have it somehow."

"Look here, Horrocks. Will you kindly leave me to my own private thumbscrews?"

The Purser laughed. "That's snubbing me. Well, I took the risk with my eyes open. I guessed you'd tell me to mind my own business when I mentioned your wife, and that you'll mind yours. But you see, in a way it was made my business too, and I wanted you quite to know how we stood."

"Look here, you nuisance, will you shut up?"

"Yes. And now come and have a bit of cheap lunch. We'll consider we've tossed for it, and if s on me."

Perhaps it takes a very high-minded man to see black crime in smuggling diamonds into the United States, and one must confess that anyway Mr. Horrocks' conscience was easy about the matter. All pursers do it, or wink at it for a consideration, or help at it—if only they get the chance. As Mr. Horrocks put the matter to me: "It all depends on a tariff. If there's no duty on importing diamonds into New York, you may bring in all that you've money to buy, without declaring them, and nobody objects; but if some renegade Irishman, who's a member of Congress, gets paid to make a tariff which claps on a heavy ad valorem duty, why then, if you try to slip through the Customs, there are people who want to make out you are first cousin to a thief and a forger.

"Smuggling," he went on to say, "is mostly done for vulgar profit, and some people will say it is much like gambling on stocks and shares, or on a horse, where you take a big risk in the one hope of making a big return without earning it. You want brains and artfulness there if you're going to make anything like a habit of winning.

"Smuggling diamonds always strikes me as no more iniquitous and much more sporting. If you put your money on a horse or a gold mine, you stand either to lose it or to skin the other fellow. But your liability's limited. If you buy a stock of diamonds this side, with the intention of running them through free of duty, it's a different thing. You've got your work cut out for you right along. You've got some of the brightest intellects in the United States against you. And you've to manoeuvre like a chess player if you want to get round them. Remember the one-eyed man who tried to smuggle diamonds through in his hollow glass eye? They got him, first shot. It is no use trying to smuggle them in your boot heel, or to make your dog swallow them, or to have them stuck inside a real original Greek antique statue. These games only make the Customs tired, and they smell out the diamonds as though they were onions, and the result is you not only lose the original capital you've sunk in the venture, but you find yourself let in for further liability in the shape of fines, and costs, and so on.

"So you see the game's raised above the level of mere stock exchange or racecourse speculation into a very sporting enterprise indeed; and if you ask me, it's as much that as the mere profit of the thing which drags so many people into it. This is the way: a fellow gets a smart idea: he finds he owns a hollow tooth that's an ideal hiding-place, or it occurs to him that no Custom House officer would search a bottle of salts, and he goes into the smuggling business out of sheer pride to prove that his theory's right. And there's another thing. Diamonds have a fascination for some people, especially women, just as horses have for others. They love them for their own sakes alone, and will do a lot just for the chance of being near and handling them."

The man who was at the bottom of the little game Mrs. Clayton wanted Mr. Horrocks to join in, was an old practitioner. He travelled for a Connecticut firm in England and the Continent, and his line was agricultural machinery, and he made a very good thing out of it. His tale was that none of the English firms could turn out a reaper and binder, or any other machine, either in price, weight, or effectiveness to compete with those produced by the American Trust, and apparently the tale had enough truth about it to be swallowed, and he was annexing the trade as fast as his works could fill the orders. He was one of the best-known passengers in the Western Ocean, and as he always took an expensive room, and ran up big wine bills, Mr. Horrocks made it his business to see that he liked him, and did most of his travelling on the ship on which he was Purser.

The man had got a surname stowed away somewhere, but no one ever heard it—at least on board ship. Even if he came on to a boatload of strangers, it slipped out before she was clear of the Mersey that he was Diamond Cy, and that was all the name he ever got. No one ever lengthened it out to Cyrus, and no one ever gave him the surname, much less a Mister. One could not possibly be anything but familiar with him.

Diamond Cy.

As the Purser described the man to me: "I've seen stiff, starched English, who would have made chilly corners on an iceberg, thaw down straight away when Cy chummed up with them. I even saw a bishop once drink champagne with him in the morning before luncheon, though you could tell all the time he was wondering why the blazes he did it. Common wasn't the word for him. He'd an accent you could take away and drive in as a railroad spike, he'd clothes like a music-hall comic, his hats and boots and linen were varnished till they shone like glass, and he'd diamonds all over him wherever they'd stick. He was a little meagre bit of a chap, about the build of a jockey, and I tell you he'd a way about him that no one could snub if he intended to be friendly.

"As a matter of fact, it was few enough people who ever tried the snubbing game. We always have our constant passengers between Liverpool and New York, and these get to know one another with an intimacy that would surprise those folks who only understand meeting one another every day in a train ashore."

Cy, as the stout Purser explained to me, was worried by no nice feelings. Let him have plenty of people staring at him, and talking to him, and valuing up his diamonds, and he was as happy as a brewer with a brand new baronetcy. Ashore he sold agricultural machinery for all he was worth. But on shipboard was his holiday, and he played at it a hundred and ten cents to the dollar. He felt that he was top of his own particular line, and he wouldn't have changed his billet to become second man anywhere.

"I often pity your Prince of Wales," Cy said to the Purser once, 'he's such a very poor taste for jewellery. Now if I were a man in his position I'd wear a band of brilliants round my hat at the very least. I'd set the fashion. Guess I hain't enough gall about me just now to hoe a new row like that, though I'll allow the idea's occurred to me, and I've been very much tempted more'n once. No, s'r, I could do with being King of Britain, but, if anything less was offered, I reckon I'd rather stay as what I am. I've got no use for being cramped like your Prince of Wales."

It was Cy, then, who offered the diamond crescent to Mrs. Clayton in return for a little help, and it was Cy who told Mr. Horrocks that there was a check for a nice round sum waiting all ready made out in his name, and the Purser knew that if he was going to make a run of diamonds through the New York Customs, it would not be for a mere nutshell full of stones. If Cy did anything at all it would be big, even if it was only for the sake of boasting about it afterwards.

Besides, rumour went about that Cy was retiring from the active pursuit of commercial travelling. He had been so successful that he had pulled together a competency, and was going to be made a director of the Trust, so that he could stay in one place and show off his diamond watch-chains and other decorations to a home audience. Eccentrics of his description meet with more general appreciation in the United States; in England people seem to lose the humor of them after the first look.

Of course there are one thousand ways in which a purser like Mr. Horrocks can help a little game of this sort, and Cy knew that well enough, and looked upon the check he offered just as so much money spent in insurance. It would have been all worked smoothly, too, if he had left the matter in Mr. Horrocks' hands. But the man was too loose-lipped. He had gabbled and boasted and promised to Mrs. Clayton, and insisted on having the Skipper bear a hand, and here was the Skipper unexpectedly cutting up rusty. The worst of it was from Mr. Horrocks' point of view, if a Captain takes that line, a purser is seriously handicapped; he dare not take the risk of being reported.

So on the whole Mr. Horrocks decided to keep out of the affair, and to give Cy notice to that effect.

He found him with some difficulty, and got him on one side with more. "Take the cinch from me," he said, "and leave those shiny goods of yours in the bank. Skipper's got his back up, and it's quite on the cards he'll give the office to the Customs himself. Wait till you're across next time, and have your flutter then."

"Shucks! Clayton's a white man. And besides, his wife'll have gotten him talked round by this. Guess she means having that crescent."

"Look here, Cy. Do you know Captain Clayton best, or do I? Remember he's new to command, and he's very high flown notions about the purity of the boat!" And so the Purser went on at him, and in the end came to the conclusion he had convinced him to a certain degree. Cy said he would not try to run his diamonds this trip. But at the same time he was perfectly convinced that the Purser was wrong about Captain Clayton, and said so with enough emphasis to ruffle Mr. Horrocks' dignity. He was a bit too authoritative for Mr. Horrocks' taste, was Diamond Cy when he'd been dining, and he had been dining that evening rather copiously.

A purser like Mr. Horrocks is pretty well harassed with work on the day of sailing, and so next morning he gave Master Cy little thought. Old hands do not seek much attention from the Purser when they come aboard. They know their names are ticked, and their bedroom stewards are waiting for them, and they are put down already for the best table places available; and so they just clap their hand baggage in their rooms and lock the door, and go off for a smoke till the bustle is over and the boat is down river.

As Mr. Horrocks said: "It's your tourist, or your theatrical, who wants what's set aside for his betters, and tries to turn the ship upside down to get it, and drains the Purser of his soothing powder. We'd an extra consignment of the tourist class that trip, including two lords and a member of Parliament, and a Jew chap who wrote novels and lectured upon them, and each seemed to think that the Atlantic Ferry was run for his especial benefit. So I had to let each see that I understood that this was so, and to tell him in confidence that the firm had given special instructions to see that he got extra attentions.

"'It's always better to tickle a fool than tease him,' is what our Mr. William Arthur is always rubbing into the Firm's Pursers, and there's no denying it's a splendid motto to work on. For instance, by blarneying that slobbery novelist, I got out of him that he had sneaked a free pass out of one of our agents —who ought to have known better—and had promised to write up the boat in one of the papers.

"Could I come to you, Mr. Horrocks, for my matter? Of course I want information about things which passengers usually do not see.'

"'You've just come to the right man, sir, for that,' I told him. 'There's lots of things I know about this trade that ought to be exposed in print, but it takes a man like you to write them up. Spicy things.' And so I got rid of him, and made a mental note to load him up with as much fiction as he'd carry, and to take care he didn't see anything through his own silly spectacles that was intended to be hid. Men like that novelist are the bane of a purser's life. They are always nosing around for 'articles,' and 'yarns,' and 'paragraphs,' and if you don't take care, and let them print everything they come across, they'd scare half the passengers off the Atlantic."

So what with one thing and another Mr. Horrocks was pretty well run to keeping his peace and getting his passengers stowed away, and he was none too pleased when a message came from the Captain to him in the saloon that Cy wanted to see him on deck.

If it had come from Cy alone (who ought to have known better) the Purser would have taken it for a joke, and refrained from going; but when Captain Clayton backed up the message by compliments and a request that meant an order, the Purser had no choice. So he smiled at the new batch of passengers who had come up to pester, and cursed at the back of his teeth, and went up the companion with the most rapid steps his portliness and dignity would permit of.

The matter happened in the days before the big boats came alongside the landing stage, and there was the tender grinding against the ship's side in the tideway, and Captain Clayton and doctor and first officer standing at the place of reception in full uniform. Captain Clayton had the knack of making passengers think that he felt lonely without a sword thumping against his hip, and if any of them did not notice the Ambleside's blue ensign, and find out what it was there for, it was not the

fault of her commander. "And after all," as the Purser used to remark, "What's the use of being E.N.E. if you don't let people know it? You get precious little out of the Reserve, except complacency."

However, there was Captain Clayton, but there was no Cy; so Mr. Horrocks went up sharply enough and said, "Yes, sir," in a tone calculated to suggest that he was a very busy man, and was much needed elsewhere.

"Sorry to call you away. Purser, but one of the passengers—"er —I forget his proper name—well, it's Diamond Cy—has had a big smash, and insists that you as an old friend should go and help him aboard. I sent the doctor to him, but he—er—wasn't amenable."

"Used most infernal language to me," said the doctor. "Told me he was too broke up to take any extra chances from a-"

"Very well, sir," said the Purser sharply, "I'll see to him," and away he went across the gangway on to the tender. Sure enough there was Cy on the deck laid out on a hospital stretcher, all covered up by a rug, looking very ill.

"Thank whiskers you've come. Purser," he gasped out. I'm all broke up into five-cent sections. Only held together by splints—oh!—and sticking plaster. For God's sake, old man, make them carry me gently to my room. The brutes nearly killed me when they brought me on this beastly tender. You had a broken leg yourself once. You told me about it. That's why I wouldn't let that butcher of a doctor help."

"Thank whiskers you've come. Purser," he gasped out.

"You've sent for just the right man," said Mr. Horrocks. "You shall be taken to your room as easy as a conjuring trick. You shut your eyes now, and put your money on the Purser. I'll have you wafted across in half a pig's whisper, and you shall never know what's happening. Wish I may break my own leg if you're hurt. There, shut your eyes, and from when I give the word you won't jolt against anything else till you touch your bed. Now, you bearers, both together, lift!"

The bearers certainly showed abominable clumsiness; and then they had some trouble in clearing the alley-ways, so that the wounded man should not be jostled; and next, some timorous creature got the notion that Mr. Horrocks was bringing a small-pox patient on board, and he had to explain to most of the passengers individually that it was no such thing, and that a broken leg is not catching. Indeed, a Purser on one of these big boats requires a high coefficient of tact and placidity if he is to preserve his temper, and keep the peace, when she is getting started.

However they got Cy down to his room at last, though whilst they were shifting him from the stretcher to the settee he used language that would have made a Spanish inquisitor stop and think.

The man had a tongue in him, when he chose to use it, like the mate of a cargo tramp.

Mr. Horrocks could stand a good deal of this sort of thing, but felt it due to his position that he should draw the line somewhere. "You seem to have got it bad," he said stiffly, "in everywhere except your voice."

"Guess you'd loose off a bit if you'd your bone-ends grating together like mine. And where I'm not broke I'm bruised."

"I'll send the Doctor to you."

"If you do, I'll use language to that man that's calculated to wound. Guess I've only been practicing up to now. No, s'r, I've got no further use for doctors. I've been put to the torture sufficiently these last few hours to fill me up for the rest of my natural life, and, kill or cure, your ship's Doctor doesn't put his breath into this stateroom. Henry still bed-room steward here?"

"Yes."

"Henry's part of the boat. Henry'll fix me, with the help of that chap that's just gone out. He's a hospital attendant I brought along, and he can have the spare berth and sleep in here with me. Never thought I'd come down to not having a room to myself. I'll square up with you for his passage afterwards."

Mr. Horrocks dipped away then, and saw the hospital attendant in the alley-way outside. "Cy seems to have got it bad," he said.

"Yes, sir. Knocked down by a cab."

"Pretty full at the time."

"I think he was, in a manner of speaking, inebriated, sir."

"He was getting on that way when I saw him last night. You know you're to sleep in his room?"

"Yes, sir."

"That's first-class. So you meal in the first-class saloon. I'll tell the chief steward to put your name on a place."

"Begging pardon, sir, but I should be in a manner of speaking out of my element with the society. If you could make it second-class?"

"Certainly," said the Purser. "Very proper feeling on your part. I'll see to it."

Mr. Horrocks took a liking to that hospital attendant. As he explained it to me afterwards: "He saved me a lot of trouble by his sensible action. Wherever I'd put him in the first-class saloon I should have had some shirty passenger coming up to me and want to know what the devil I meant by giving him a flunkey as his dinner companion. 'They never do that on the Blue Moon line, or the German boats, and I don't think your directors would approve of it here if only they knew about it.' And mentioning that somebody paid full first-class fare for the poor beggar, and that therefore he was entitled to his full privileges, was no argument. Put him next somebody else, then. Put him next yourself if you're so keen on him,' was what they'd reply. There's no getting passengers to see the balance of things."

However, Mr. Horrocks had no time for moralizing then. Back he had to go to the saloon to get the passengers sorted and settled. The member of Parliament bombarded him with stilted abuse because he was put at the doctor's table, and the novelist offered to run him in as a character in one of his books if Mr. Horrocks put him next to a lord. He certainly did only have three people that day who wanted an assurance that their sheets were properly aired, but on the other hand he had no fewer than four different brands of clerical gentlemen, who wanted the loan of the saloon for daily prayers. Moreover, a record number of fools pestered him that day to guarantee them a smooth passage and no seasickness. "The Red Funnel boats do it, and why can't you?" "The German boat came across the other day with no one ill." "Can't the Captain go round some other way if this one's rough?" And fancy having to give a civil and soothing answer to each of them.

Indeed the Purser was about worn out by the time the smoke-room lights were switched off that night, and when a steward brought word that the Captain would like a chat with him in the bridge charthouse, he began to wish he had a billet ashore with only fourteen hours work a day. However, at sea, being tired does not come into the scheme.

"Sit down. Purser. Have you seen our friend Cy again? Do you think he's really hurt? Or is it a little game he's trying to have on?"

"If you heard him swear, sir, you'd believe he's genuine enough."

"Well, that may be. But anyway he's still sticking to his scheme of smuggling those diamonds into the States without paying duty."

"But he told me plainly, sir, that he'd given it up."

"Told you wrong then. Purser. You know the New York Customs have their men over in Liverpool, and they're hand in glove with our Customs. Now Master Cy is a pretty notorious person, and they've been having him pretty shrewdly watched. He's got the parcel on board here with him."

"Oh."

"Now you'll please understand, Mr. Horrocks, that no officer of this ship is to have any dealings with those gems otherwise than to assist the New York Custom House in performing its proper functions."

"You've mentioned that to me before."

"I know, when we were ashore. But our relations were slightly unofficial then, and I don't want any mistake. So I tell you now quite officially."

"Very good, sir. I quite understand."

"Then that's all, Purser. Good night."

"Good night, sir."

Mr. Horrocks was tired enough, as I have said, and he was not long in getting turned in. But it was well on into the morning before he found any sleep. What was Cy's game? And could he have a finger in it, and touch his profit without getting burned? Mr. Horrocks felt that it was all very well for Clayton to be puritanical. As he put it to me: "The Skipper had lots to gain indirectly by being in with the Customs. And, besides, he'd other legitimate pickings.

"To be sure, he wasted a lot of time over lords and that class, out of sheer vanity (as I called it) at being able to say he knew them. But at the same time he mostly contrived to let his room each run for a tidy sum. You know, there's a type of passenger that takes a delight in saying: 'The Captain gave up his own cabin to me.' And likewise he naturally had the sense to make himself civil to that class of American millionaire that gives a Captain silver salvers and services of plate, which sell, if you go to the shop where they were bought, for very nearly what they cost.

"I won't say altogether, too, that his wasting of time over the folks with the titles was not capital well sunk, because the millionaire class love dearly to hear about them at second-hand —and hence the presents of salvers. But, anyway, what I mean to point out to you is that Captain Clayton had lots of pickings, whether he made the most of them or not, whereas I, as Purser, had precious few. It's annoying enough to see twenty-dollar bills going to chief stewards, and valuable scarf pins to captains, when it's really you that's managed all the passengers' comfort; and, of course, you'd have too much proper pride to accept them if they were offered; but that's one of the penalties of the position, and so you've got to use your wits to find dividends in other ways."

Mr. Horrocks had no time to look in on Cy till after

the Ambleside had left Queenstown, and when he did go

in, the invalid was inclined to be resentful at not being

called on before. However, the Purser was not fool enough

to apologize.

"You've got your language stop out too much for my taste," he told him. "But if you don't want me now, I can go right off to the smoke-room."

"Oh, I weaken. Sit down. Purser, and help yourself to rye. There's a bottle in my gripsack. Guess if you knew how mighty sick I was, you'd sling a bit more sympathy round. I'm feeling as if I couldn't take a pride in anything, not even in dress."

"Did you get robbed when you were knocked down? With all those diamond watch chains, and studs, and bootlaces —or is it braces-buckles —that you sport, you are worth looting as a general thing."

"No, I was lucky there. I suppose an honest man must have picked me up. I should like to have rewarded him. I've an affection for a man that's kind to my diamonds."

"Then you may prepare to love me, Cy. I came along here to give you another straight tip about that parcel of gems you want to smuggle into the States. You were a fool not to leave them behind in the bank as I advised you. But as it is, just be a wise man, and declare them and pay the duty. You'll find it cheapest."

Cy looked considerably upset. He said he had been a good deal shaken up by his accident, and naturally his nerves were not in the best order.

"Cute bluff of yours, Purser. But what's wrong with their being in the bank?"

"This. They've had a detective on you in Liverpool, and it is known you brought the diamonds on board here. Captain Clayton knows, anyway, and he's warned me officially not to help you. I should say it's just a moral certainty he lays information about you himself."

"Most natural thing for him to do if he's soured on the idea of standing in. No, sir, I don't blame the Captain any for fiddling out the tune for his own benefit. But, all the same, I don't think my great and glorious country is going to scoop a lump of duty out me this trip. Guess I'd feel real mean if I couldn't walk my little lot round them."

Mr. Horrocks shook both his sides in a pleasant laugh.

"Well, Purser, I don't mind owning to you that I have that parcel of stones right here in my baggage. When you saw me that night before we sailed, and gave me the cinch, I'd a mind to weaken and shove them in the bank next morning to wait over for another trip. But I guess I got a bit on the ra-ta that night, and after the accident I was too crumpled up to think of anything except how it hurt. So my trunks were packed by that hospital attendant with what was there in my room, and I'm taking it on trust that the diamonds are in the Saratoga under the settee you're sitting on. But, to tell the truth, I'd like to make sure."

"Anything I can do?"

If you would, old man. I know I can trust you. As for the hospital attendant, he may be all right, but I've only his word for that, and £10,000 worth of diamonds is a big temptation. Here are the keys."

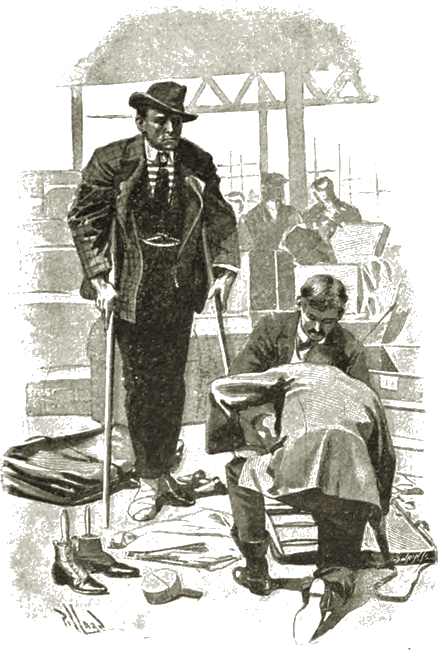

Mr. Horrocks pulled out the Saratoga, unlocked it, and threw back the lid.

Mr. Horrocks pulled out the Saratoga,

unlocked it, and threw back the lid.

"Steady on," said Cy, "this isn't a game of hide-and-seek. There should be a pair of yellow-topped patent leather boots with lasts in them?"

"They're here."

"Take out the middle tongue of the last in the right boot."

"So?"

"That's it. Now screw out the ring at the top."

The Purser did that. There was a brass washer underneath the ring, but instead of a mere rod of mental beneath, there was a solid screw plug the size of the washer, and inside was chamois leather which rose up gently when the pressure was taken away from it.

"Good man, Cy. That's a brand-new and original kind of hiding-place, and I believe it's almost good enough to bluff a New York Customs' sharp."

"Pull 'em out, siree, and see my stock. There should be just sixty-three stones. I guess you'll know me for enough of an expert to take my word for it that there isn't a flaw in any of them."

Mr. Horrocks picked out an end of the chamois leather, and drew out a neat little case, wound up into cylinder form with silk. He undid this, and spread it out carefully on Cy's counterpane. A great blaze of cut diamonds twinkled and shimmered before him like some essence of rainbows.

"Aren't they things to say your prayers to. Purser? Guess you never saw a parcel of stones like that before. Look at the colour of them."

"They seem nice and white."

"White! They're blue Brazilian diamonds, every one of them. Why, they don't show yellow even on that shammy leather. None of your off-colour stones for me. I've a reputation to keep up, and I know how to pick diamonds that'll do it. Yes, sir. I've an eye for colour in stones that'd surprise most men that think themselves experts."

"All your sixty-three are here by my count."

"Then let's put 'em back again. T'aint over healthy letting this kind of real estate smell too much daylight aboard ship here. You never know who may come to pay a polite call, and think it more genteel to stay just in earshot outside the door. There you are. Valet my boot for me again. Purser, will you?"

Mr. Horrocks rolled up the diamonds in the chamois leather, served it round with the silk, and slipped it in place. He screwed in the plug, crammed down the middle tongue of the last into its place in the patent leather boot, and put it back in the Saratoga trunk, and then, with a sigh, he closed the lid.

"Now, Purser," said Cy, "you see how I'm fixed. The diamonds are here on board, and they've got to be run. The question is, who's going to do it? Would you like to have an invitation to dine ashore, after we get in, and take off a bag with you to dress at a hotel, and carry those boots in your bag?"

"It would be a big risk."

"No, sir. I don't think it. In fact I guess the risk is so small that the fee for porterage doesn't seem to me to foot up to more than £40."

Mr. Horrocks got up majestically and reached for his cap. "It seems to me," he said unpleasantly, "that you've made a mistake. I'm not a steward, Cy, to pick up your paltry tips. I took you for a gentleman, and I'm sorry I made a mistake. If people don't offer to deal reasonably and fairly with me, I don't do business with them at all."

"Say now, Purser, don't go and lose your hair over it. I offer a fair price, and if you don't choose to take it, there's an end of the trade."

"So far as I'm concerned."

"And all that's been said is in confidence."

"Of course. I know nothing about any diamonds except the half-pint or so you wear in sight; and as for lasts in patent leather boots, I never heard of such things."

"You're a white man right through, Horrocks," said Cy, and there the Purser left him. If Master Cy chose to be so injudicious as to run up against the Purser's dignity with so small a bribe, it was somewhat natural that the Purser should nourish a slightly vicious hope that Cy might be led to see the error of his ways. The boot with the hollow last was a very clever scheme no doubt, but the New York Customs officer had smelt out hiding places as canny before, and, moreover, this time they would start with the advantage of knowing almost for a certainty that illicit diamonds were in Cy's luggage somewhere, and so it was probable that they would go on searching till they found them.

However, Mr. Horrocks had little enough time to waste on Diamond Cy and his affairs for the rest of the trip. As he put it to me: "There was that Jew novel writer to be attended to. He was sick for the first two days, and I tried to get the Doctor to give him something that would keep him sick till we got to New York. But the Doctor, malicious old fool, wouldn't; laughed and said that what I was paid for was to keep passengers of this sort in talk; and that is just what I had to do. The nasty slobbering mouth of the fellow nearly made me sick, and the way in which he talked about himself, and his fame, and his books, was disgusting. But there was no doubt about his ability for mischief, and so I had to take my precautions.

"I sent word round amongst the stewards that I'd sack any man who yarned to him, with a 'Decline to report' on his discharge ticket, and I set myself to gain his affections. Lord! In two days the beast began to think that I regarded him as a long-lost brother, and I loaded him with enough stuff to go on advertising the Line for all his remaining days. He wanted to know about everything, and he was by no means a fool in his questioning; but I hadn't been handing over reports to newspaper men all my years without knowing exactly what to give them. with safety, and exactly what looks safe but can be distorted, and exactly what must be kept away from them at all hazards.

"These writing animals do catch hold of a tramp's skipper or an old deck-hand occasionally, and get to know about what goes on aboard the class of vessel that carries no passengers; but on the big liners it's another thing; and ifs an officer's chief duty to see that nothing leaks over into print that can do the boat or the Company that employs him harm."

Especially was this person desirous of knowing how diamonds were smuggled, and Mr. Horrocks gave him a lot of useful information on that subject which he piously hoped would tempt him to get credit for a consignment, and then find himself caught and in jail. It was one of the great draw-backs of Mr. Horrocks' professional life that he had to supply his smiles, and his jests, and his genialities free gratis to certain passengers whom he cordially wished at the bottom of the sea.

"I hear there's a celebrity called Diamond Cy on board," the novelist said to him one day. "Couldn't I get to see him?"

"Impossible, my dear boy," (Mr. Horrocks explained to me that he always called theatricals, acrobats, and authors, and that lot "dear" because he said "they seemed to expect it.") "Cy's all crumpled up and don't receive visitors. But I can give you his full particular history if you wish it."—And he did so.

"I was told privately that he's going to run a big lot of diamonds through the Customs this time."

"Very likely. There's mostly that yarn floating about any boat Cy decorates with his presence. But I should say it's never true. 'Tisn't his line, any more than it's mine or yours. A few blessed Dutchmen from Hatton Garden keep the monopoly of that trade in their own hands."

"H'm," said the novelist, but Mr. Horrocks did not think he was convinced, because he went on so quickly to other topics. So he looked in at Cy's room again that evening, and told him people were talking about him. "You'll be nabbed as sure as Heaven made little apples," said Mr. Horrocks, "if you don't cut your profits and declare your stuff in the usual way."But Cy was feeling grave and cantankerous, and the most he would do was to take an omen from the Fates.

"Is there a pool on the run to-day?" he asked.

"Certainly."

"Very well. Then will you buy for me the middle three numbers?"

"At what kind of price?"

"Bid till you get 'em. If I win either of those, or if any of the three numbers on either side of them pull it off, my luck's going to be clear. If not I may have to look out."

"Poor sort of way of making omens," said the Purser, and left him. He went to his room again after lunch. "Cy," he said, "you're a gloomy prophet. Those three middle numbers were run up to an extravagant figure, and you owe me £20 for them."

The sick man handed over the money, and Mr. Horrocks deposited it in a place of safety against his rotundity.

"And you haven't won with either of them. The pool was pulled off by 'Highest number and above.' We happened to make a record day's run."

"Well!" said Cy, "I never set much store on omens anyway. Guess they were all right for the Ancient Greeks, but I'm too modern for them. But I can't tell you what I shall do. It will all depend on the mood I'm in when we come within smell of East River mud again."

And that was all Mr. Horrocks could get out of him. Cy had turned very queer-tempered since his accident. Perhaps the fact of being shut up in his room with only the hospital attendant as company most of the time was a trifle trying for him after being used, as he was, to being stared at, and pointed at, and talked to as one of the celebrities of the North Atlantic. And, moreover, his hurts kept him down below all the time they were at sea.

However, when the Ambleside had passed Sandy Hook, and the New York Customs' officers came on board from their tug, and went down into the saloon to make the passengers sign their declarations, in hobbled Cy on his crutches, looking very shaken and white, but with all his diamond studs and watch-chains and tie-pins in full blaze. He lowered himself down into a chair with the help of the hospital assistant, and took up a blank declaration form and a pen.

"Hullo, Cy," said the Customs' officer at the end of the table. "You back again?"

"I'm too fond of my country and too proud of her bright, cute guardians," said Cy, "to leave her shores for long."

"No, I know your little ways. Brought back anything in my line? I'd like to see the colour of your money."

"Not a cent's worth," said Cy, and filled in his paper with blanks, and signed it.

"Better think again. You've a diamondiferous look about you."

"Guess I'm not going to declare wearing apparel I bought in the States, and those are about all the diamonds you'll find in my possession."

"Oh, don't let me press you any," said the Customs' man. "I was only chucking around a pleasant hint, and if there's a funeral to follow, I guess it won't be mine."

The Purser was called away then to the Second Class, but he took it for granted that Cy would be sensible and give in, and declare his merchandise. But no such thing. And as a consequence the Customs' people opened all his trunks when they got ashore to the shed, and gave them such a searching that of course the diamonds had to turn up at last. It was only natural that this should be so, because if you start with a more or less certain foreknowledge that the thing you want is there—and it seems that the fiction writer who had next cabin to Cy let the cat out of the bag, so Captain Clayton said—it is only a case of time before you find it.

Cy, of course, was in weak health, and cursed them with viperish tongue for keeping him standing round there with aches all over him, whilst they did their tedious search. He called them all the kinds of brute that occur in America, and would really have bluffed them out of their search if they had not been so entirely sure about it. In fact he stuck out gamely till the very end. But when the hollow last was found, and, the diamonds pulled out, he just broke down and crumpled up. It was quite pitiable to see him. He was crying, and sobbing, and laughing all in one, and at last the Custom House officers, out of sheer humanity, bundled him into a hack, hospital attendant and all, and told him to drive away to his hotel. They knew they could always find Cy when they wanted him, and meanwhile, of course, they held on to his unlucky parcel of diamonds.

Cy cursed them with viperish tongue for keeping

him standing round there with aches all over him.

Personally Mr. Horrocks did not pour out much unnecessary sorrow over Cy, because if you give a man a lot of sound advice, and he deliberately puts it aside and gets hurt, you naturally cannot help feeling that he should have paid more attention to your valuable words. And as for Captain Clayton, as Mr. Horrocks puts it: "He was being entertained at the Waldorf-Astoria by one of his lords and the M.P., and never gave a thought to anything as common as Cy and smuggling. He had a knack of doing quite the naval officer ashore, and you'd never have connected him with commerce. But from what came out afterwards, he might have had a bit more to do with Master Cy and his affairs than he chose to appear."

However, when the Ambleside had just about finished unloading, and they were beginning to work cargo in-board, a messenger came down with a note from Cy, inviting the Purser to dine with him at uptown Delmonico's. Of course, he went. Not only is the keeping on friendly terms with regular passengers one of a purser's professional assets, but Mr. Horrocks was a man who thoroughly appreciated a good dinner.

Ashore he practiced austerities for reasons of purse alone, and if he did violence to his palate by patronizing the baser kinds of restaurant, he solaced himself by the thought that the money so saved was more profitably employed in the up-keep of "Rock's Orphanage" an institution in which he was vitally interested.

But if Mr. Horrocks had pictured Cy as doing the honours on a couch packed with pillows, he was very decidedly mistaken. Cy was dancing about as full of activity as a be-decorated monkey, and the crutches were fantastically thrust out as ornaments amongst the flowers in the centre of the table. He had a lot more gentlemen of his own kidney in the room when Mr. Horrocks arrived, and they were roaring over a smart story in one of the evening papers. "How the brightest Custom House officers on earth bought a sell," it was headed. "All that glitters is not diamonds!" And a bit lower was: "Diamond Cy adds fresh laurels to his fame," and so on.

Cy was dancing about as full of activity as a be-decorated monkey.

The Purser looked through a paragraph or so. "Look here, Cy," he said, "were those diamonds you showed me duffers?"

"You bet," said Cy cheerfully. "Best paste that's made. Cost me a Croesus of a lot. Didn't they shine?"

"Splendidly."

"Those Customs' sharks sucked them down like rye. Say, Purser, weren't those toney tears of mine when I broke down at the—let's see, how does the paper put it—at the disgrace and ruin of discovery?"

"But I don't see yet how you-"

"Crutches, old man. Crutches with a hole up the middle of the shank, with the real brilliants dropped in, and set tight with glue. Crutches by themselves wouldn't have stood a cat's chance. But crutches, and an accident, and a hospital attendant do the thing together more in style. And then, when you plant a nice hollow last in a patent leather boot, why, there, I guess you load up the mind of any Customs' officer that walks with all it will carry. Nothing wrong in bringing paste brilliants inside the last of a patent leather boot. No duty on them. Don't have to declare them. Look here: the papers all say so. Lord! haven't they been rubbing it into the New York Customs in this evening's editions!"

"Well," said one of the others, "if you've done preening yourself like an absurd peacock, Cy, what's wrong with starting dinner? Guess well get to work seriously, drinking your honoured health later on."

So they fell to and proceeded to enjoy themselves. Diamond Cy was nothing if not gorgeous, and he had given Delmonico's a free hand. He felt he could afford it. He had smuggled in £10,000 worth of gems free of duty, which pleased him vastly, and he had set all New York laughing at his cuteness, which pleased him far more.

Mr. Horrocks would have liked much to have fingered a share of the profits for the benefit of "Rock's Orphanage," but as a matter of fact that dinner was all he got out of the business. But he had a vague notion that Captain Clayton somehow or other fared better. Clayton looked wise, and laughed when the Purser hinted at this latter, but he said nothing. He was not a man who cared to commit himself. But Mrs. Clayton got that diamond crescent, and wore it openly in Liverpool in the daytime, and one does not see how Clayton could afford to have bought it out of his ordinary pay as Captain.

Mr. Horrocks told me that he intends to get to the bottom of that matter yet; but up to the moment of going to press he has not done so, and this tale, therefore, as regards that point, must necessarily remain incomplete.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.