RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

An RGL First Edition©

RGL e-Book Cover©

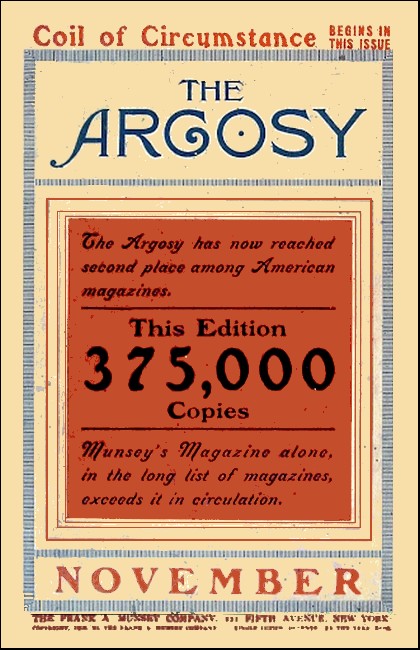

The Argosy, November 1903,

with "Miss Sherlock Holmes"

The mystery in a big department

store, and the strenuous fashion

in which the house detective solved it.

JASPER MARKLE, manager-in-chief of the big department store of Markle Brothers, sat in his private office, frowningly biting at the tip of his pen-holder, while he listened to the report of the dark-haired, keen-eyed little woman before him.

It was long after hours, and the hum and bustle which swept through the immense building all day, making it seem like nothing so much as a huge, buzzing hive, was stilled for the night. The only sound which came to them now was the echoing footfall of the night watchman as he made his rounds through the untenanted corridors.

The light from a shaded electric lamp above fell in a vivid circle upon the floor, embracing both the man and the woman, but leaving the rest of the room shadowy and indistinct.

The manager's office was on the first floor, an ornate little retreat, tastefully constructed of glass and polished wood, and furnished with the modern appliances of business—a roll-top desk, a typewriter's table at the side, a letterpress, some cabinets and file-cases, a couple of chairs for chance visitors.

Nor did the autocrat who held forth in this domain, and whose word was law throughout the entire big establishment, fail to accord with the character of his surroundings.

A man about fifty years of age he was, with a spare, well preserved figure, shrewd, cold eyes, a firm, thin-lipped mouth, and gray side-whiskers of formal cut. His attire was quiet, but modish and expensive.

"You are positive, then, Miss McCrea," he observed, when his companion had fully set forth the facts she had to offer, "that these annoying thefts are not the work of shoplifters?"

"Absolutely so," she replied, giving an emphatic little nod to her head. "During my whole three years here, I have never known the store to be more free from visitors of that class than it is at present. In fact, the only one of them that has got past the door in the last three weeks was Belle Dickson. I spotted her at the millinery counter last Friday, and put Emerson on to her; but she quickly realized that she was being watched, and made herself scarce.

"I have questioned, of course, whether a new and clever gang might not be conducting operations, and so have persistently dogged every stranger, but all in vain. It has only rendered me the more certain in my conclusions."

"Perhaps some one of our well-known customers has turned kleptomaniac?" suggested Markle.

"No, I have thought of that explanation, and it, too, seems wide of the mark. The pilfering is too regular and too selective to be accounted for in that way. We have no patron who visits us every day, rain or shine; and, moreover, a kleptomaniac would sequester whatever struck her fancy without regard to value. This thief, however, disdains anything except the costliest articles."

"Why are you so confident that the work is being done inside business hours?" queried the manager, branching off a little from his previous interrogations. "Might it not be possible that some shrewd band of crooks had found a way of entering the building after nightfall, and of successfully eluding the watchmen on their rounds?"

"Ah, but you forget, Mr. Markle, that our heaviest losses have occurred in the jewelry department, where everything of value is locked up at night; and there has certainly been no tampering with the safe. In addition to that, however, I will tell you that I myself spent four nights on guard last week, concealing myself so that no one could suspect my presence.

"The watchmen were alert and attentive to business, there was no sign of an intruder anywhere about the premises; yet nevertheless there was reported missing during the time four pieces of that three-hundred-dollar lace, a box of silk underwear, a dozen cut-glass tumblers, and a pearl necklace."

"You are confident, then," summed up her employer, "that the stealing must be carried out by some one on the inside?"

"My investigations force me to such a belief, Mr. Markle; and yet, in view of the precautions we take in regard to our employees, I must confess that that hypothesis also seems untenable. You know as well as I do that our people all come in and go out by the one entrance, that none of them can take a package or parcel out of the building without a written pass from yourself, and that, moreover, it would be practically impossible for one of the force, without quickly exciting suspicion, to rove about through the various departments, picking up whatever suited his fancy, as this thief has done."

Markle's frown grew deeper as he sat considering the girl's reply. His fingers drummed impatiently on the desk. Then he turned to her.

"Well, Miss McCrea," he said sharply, "I don't think I need tell you that I am bitterly disappointed. I asked you for a report on this matter, and all you are able to tell me is that it is inconceivable we should have been robbed, while every day is bringing us a story of increased depredations.

"Now, it strikes me that the matter is most emphatically up to you. Like every other firm, we expect and are willing to stand a certain percentage of loss from peculation; we figure on that in regulating our scale of prices.

"But when our losses of this character reach a total"—he consulted a little slip of paper lying on his desk—"a total of $10,000 in a period of less than two months, it is certainly time to adopt heroic measures of some sort. We assuredly cannot afford to pay a person to protect us, unless that person renders us some degree of protection.

"You have been with us three years now, Miss McCrea," he went on, silencing with uplifted hand the defense she was endeavoring to interpose, "and I am free to admit that your work up to this juncture has been in the main satisfactory; but I will tell you frankly that your continuance in your present position will depend solely upon your ability to check this pillage and discover the thief."

The woman's face paled at his words, and she had to bite her trembling lip for a full minute before she could sufficiently command her voice to make answer.

"How long a time will you give me in which to achieve results, Mr. Markle?" she asked huskily.

The superintendent thoughtfully stroked his chin.

"If you can't do it in three weeks," he finally announced decisively, "you can't do it at all. Let's see, to-day is Thursday, the seventh. On the twenty-eighth, Miss McCrea, I shall be ready to receive either a solution of this mystery or your resignation."

Having delivered himself of this ultimatum, Markle grimly held open the door for the other to depart, and then, banging down the lid of his desk, hurriedly left the building, struggling into his overcoat as he went.

The girl, only stopping to pull on her rubbers in the cloak-room, followed, but he was already out of sight when she reached the entrance.

"Ye're the last to leave again, Miss McCrea," observed old John, the watchman, as she passed out, "I'm thinkin' it's a cold dinner ye're gettin' pretty often these days."

"Still, a cold dinner is better than none at all, John," she retorted, albeit with a very sober sort of smile, reflecting as she spoke that the alternative she mentioned was by no means an improbability of the quite immediate future.

Three weeks Jasper Markle had given her, and she knew him well enough to understand that his words contained no empty threat. He was not a person to speak at random, or without duly weighing the consequences.

Three weeks to the minute would she have for her task, and that without question or interference; but not an hour, aye, not a second, over the allotted time.

The old watchman seemed almost to read her thoughts, and to sympathize with her.

"May the saints keep us all from that, ma'am," he interjected devoutly. "A good night to ye," and so closed the door behind her.

Within the shadow of the store's huge, arched portal, Miss McCrea lingered a moment, for all the world like a cat dreading to cross a muddy pavement. The evening was raw, damp and depressing, slushy and sloppy underfoot, and settling down overhead into a thin, foggy drizzle.

Along Sixth Avenue the wet asphalt was black and shiny, where the garish light fell upon it from the brilliant windows of restaurants and cafes. Under umbrellas, the nondescript crowds of pedestrians were pushing up and down the sidewalks, and in the center of the street the trolley cars, packed with moist and jostling humanity, were clanging wildly to and fro. Up above, the elevated trains roared and rumbled in their transit between the Battery and Harlem.

With a little shudder at the dispiriting prospect, Miss McCrea drew her fur collar up about her throat, and gathering her skirts together in her hand, joined the plodding procession straggling up the thoroughfare.

There was a little restaurant two or three blocks away, she remembered, where one could get a decent meal at a fairly reasonable price; she did not possess the hardihood even to dream of obtaining dinner at so late an hour at the Harlem boarding-house where she lived.

Reaching the restaurant at last, and seated at a table, she leaned her head dejectedly upon her hand, and gave way to gloomy reflections.

Her continuance at Markles', it was evident, was conditioned solely upon her success in elucidating a problem which had already baffled her shrewdest efforts. It seemed almost hopeless to make any further attempt at a solution. She might as well hand in her resignation at once and be done with it.

Yet, what to do then? This was a question of no small moment.

It was absolutely necessary that she should earn her own livelihood, and she possessed neither skill nor experience in any kind of occupation save that upon which she was engaged. If she were discharged from Markle Brothers—for a resignation under the circumstances would be tantamount to a dismissal—how, shorn of her prestige and having to confess herself a failure, could she ask for a similar position with another house?

Janet McCrea had become associated with the big department store in the capacity of detective in rather a peculiar fashion.

She had in more prosperous days been one of the firm's regular and most lucrative patrons, and one day, while standing at the silk counter, had chanced to observe the woman next to her slip a bolt of costly goods underneath her cloak. Realizing that the woman would attempt an escape if she deemed her guilt suspected, Janet gave no hint of her discovery, but quietly kept on pricing fabrics, though all the time edging farther along the counter.

At last, satisfied that her neighbor could not overhear, she leaned forward and whispered to the salesman: "That woman in the big hat is a shoplifter!"

The clerk gave one quick glance of comprehension, then lifted his forefinger in a cabalistic signal to the floorwalker. Three minutes later the culprit was being conducted under guard to the manager's office; and upon subsequent investigation it was developed that she was one of the shrewdest and most dangerous characters known to the police.

A short time afterward, Miss McCrea by a similar display of vigilance was able to repeat her experience; and on this latter occasion Mr. Leopold Markle, the head of the firm, called on her in person to extend his thanks, and to compliment her upon her readiness of wit.

"If you ever should want a position, Miss McCrea," he remarked jocularly, "that of detective at our place will always be open to you."

Janet, of course, laughed too over the suggestion at the time; but a few months later, when, through the defalcation of a man to whom they had trusted all their funds, she found herself and her mother practically penniless upon the world, Mr. Markle's offer presented itself to her mind in the light of a life-preserver tossed to a drowning man.

After all, why not? It was imperative that she should turn her hand to something, and her education and temperament failed to fit her for most of the ordinary vocations which women take up.

She could not write, or paint, or teach, or embroider, and her heart quailed at the thought of being chained down to a desk in a business office. Here was an opportunity ready-made for her, exactly suited to her mental equipment, and giving her from the start a remuneration ample for her own and her mother's needs.

She hesitated no longer, but presenting herself at the Markles', stated her case, and requested the fulfilment of their promise. They were at first disposed to balk at such a novel proposition; but Janet was determined, and so skilfully parried all their objections that finally she persuaded them to accede.

Indeed, it turned out to be one of the luckiest strokes of business the house had ever made, for amply did she justify the assurances she had given of her powers. She had been almost a daily visitor to the store before, and only the department managers now recognized that her peregrinations about the establishment were for a different purpose.

Nor did the most astute and experienced "crooks" ewer suspect that the fashionably gowned, eminently aristocratic young woman who patronized the place so extensively was a "spotter." They only realized that some apparently intangible system of espionage existed at Markle Brothers', which, so sure as they attempted a questionable move, resulted in their being touched on the arm before they reached the door, and politely but firmly escorted to the manager's office.

Thus it happened that the emporium where she was employed gradually became known to the "talent" as a good place to shun, and accordingly Janet's position grew to be a veritable sinecure.

Indeed, for the past year her duties had been almost exclusively confined to the occasional "stalking" of some society woman who, overcome by a covetous mania, would attempt to carry off goods without attending to the formality of paying for them.

Then, all of a sudden, had begun this inexplicable series of thefts which selected for booty only the best and most expensive articles in stock, and which was not confined to one or two departments, but ravaged all alike.

She had taken up the case with eager interest, and had brought to bear upon it her keenest and most concentrated intelligence, watching every avenue of possible dishonesty with the vigilance of a terrier before a rat-hole, only to find in the end that she was as far away as ever from a satisfactory solution.

There seemed absolutely no loose end on which to commence work; strive as she might, she could unearth no clue pointing to either the identity of the thief or his method of procedure, while he, apparently rendered bolder by her ill success, was daily increasing the scope of his operations.

WHILE Janet sat in the restaurant, thus dolefully meditating over the situation, she was suddenly startled by the sound of a big, hearty voice at her elbow, and, turning, she saw standing by her side Billy Brueton, the manager of the furniture department at Markles'.

"Well, well, well," he exclaimed, "this is an unexpected pleasure. I was detained at the store to-night, and, finding it too late to go home, ran in here to get a bite to eat. But I never hoped for such a welcome surprise as meeting you here. Yon don't mind if I share your table with you, do you?"

Scarcely waiting for her permission, he slid himself into a vacant place on the opposite side of the board, and listened with ill-concealed disgust while Janet gave her modest order to the waiter who had just then come up.

"Tea and toast?" he commented scornfully, "Not on your life. Miss McCrea. This is one of those nights when a person should coal up on good old essentials, and not on sick-room slops. Look here, my dear young woman, you're looking a bit off color, like all the rest of us this sort of weather, and I'm going to prescribe for you. You are to be my guest, understand, and you've got to eat what I say, whether you want to or not."

Then, disregarding Janet's protests, he turned to the waiter.

"Here, Gaston," he said, "you bring us a good, thick sirloin steak with mushrooms, and make it rare, and some baked potatoes, and what other vegetables the lady wants. And bring us a couple of bottles of Bass' ale.

"There," he explained when the bowing attendant had taken himself off, "that is what one needs to put blood in the veins, and courage in the heart. It is a regular London night outside, and one ought consequently to eat a London dinner. 'When in Rome,' you know, Miss McCrea."

Janet was able to muster up a very fair imitation of a smile at his lively chatter. Indeed, her world had sensibly become less gray and somber since the advent of this persistent optimist.

It was impossible to help liking Billy Brueton. He was one of those big, masterful, jovial creatures who continually get their own way by an audacious impudence, which their unfailing good humor renders inoffensive. Yet he was the very antithesis of selfishness; there was nothing he would not do to help a person in trouble, and his unostentatious generosity made him the idol of all his associates.

A big, well-proportioned fellow, skin as clear and fresh as an athlete's in training; warm, gray eyes, and a sunny smile disclosing two rows of even, white teeth, he was the type of man women inevitably take to and admire.

Still, despite all the adulation he had received, there was nothing of the "matinée hero" about Brueton. He was as frank and sincere and unaffected as a boy. Janet on many occasions had been the recipient of thoughtful little courtesies at his hands, and she was not ungrateful.

The dinner question settled, he turned to her now with a touch of curiosity in his manner.

"How does it come that you are dining here. Miss McCrea?" he asked, "I fancied you live up Harlem-way somewhere?"

"I do," she replied; "but I also was late to-night. In fact, I have just left the store."

He glanced up at her quickly, with a look of aroused interest.

"Is that so? Then it's funny we didn't run across each other. I came straight from there here."

"Was Mr. Markle still in the building when you left?" she queried.

"Oh, no. He had gone fully five minutes ahead of me."

"Why, how strange!" she exclaimed in puzzled fashion, "He and I went out almost together; yet old John told me I was the last one to leave, and you know John would never be mistaken on that point."

Her words seemed for some unaccountable reason to occasion her companion a marked embarrassment. He flushed under her questioning gaze, and his fingers toyed nervously with the salt-cellar in front of him.

"I—I—" he stammered confusedly; then he caught himself together, "Perhaps, after all, I was mistaken. I thought it was Markle I saw going out; but it might have been some one else.

"Yes, that is undoubtedly what occurred," he repeated. "I mistook one of the other men for Markle. You know, in the dim light, and not noticing particularly, a fellow might easily be deceived."

It was certainly a plausible enough explanation; but the very eagerness of the man's manner, as he made it, struck Janet as absurdly over-anxious and strained. Why, she could not help asking herself, should Brueton be so assertive over a matter which at the most was of very slight importance?

Before, however, she had really formulated this doubting inquiry in her own mind, the waiter appeared with his array of smoking dishes, and thereupon the conversation was diverted to matters of more immediate interest.

Nor did her companion allow her an opportunity of returning to the subject throughout the course of the meal. Indeed, he rattled on so amusingly, and with such a fund of salient gossip about their various mutual acquaintances in the store, that she quite forgot for the time the little untoward incident which had momentarily excited her misgivings.

"Say, look here, Miss McCrea," said Brueton as they waxed confidential in their interchange of views and impressions, "what do you think of Seymour?"

"You mean the man in the jewelry department?" she returned, "Well, to tell you the truth, I like him least of anybody in the store."

"He is a surly, unsociable sort of a chap, isn't he?" agreed Billy, "But I guess he has cause to be soured against the world. Did you ever hear the story about him?"

"No," with feminine curiosity. "What is it?"

"Well, in the first place," rejoined Brueton, "Seymour isn't any more his name than it is mine—I forget now what his real handle is, although Phil Hartopp, a bookmaker friend of mine, told it to me once; but that doesn't make any difference, anyway. What I was going to tell you is, that he used to be the owner of one of the biggest jewelry stores in town, a bang-up, swell place over on Broadway.

"They say, in those days, he used to be a regular 'Sunny Jim,' genial and pleasant to every one, and furthermore was a model of all the business virtues, straight as a string, and his simple word a good deal better than most men's bonds.

"It seems, however, that he had a brother who was a plunger, one of those fellows that maintain a betting commissioner at the tracks, and who are constantly laboring to break up gambling in New York—by winning all the gamblers' money.

"From all accounts, brother must have been a pretty hard lot, although he did manage to keep his sporting career on the Q.T., and so retained a lucrative business clientele—he was agent for several large estates, I understand.

"Well, not to spin out a self-evident climax, the crash ultimately came, and Mr. Brother took his quiet little sneak for South America, leaving about eleven dollars' worth of assets for his creditors to divide up between them.

"One of the heaviest losers, as it turned out, was none other than Seymour, for he had very foolishly entrusted all his affairs to the financial genius of the family, and when it came to a pinch, that astute individual had entertained no more scruples against bilking him than he had any of the others. In short, Seymour was practically a bankrupt by the transaction.

"Talk about being wild. They say the man was little short of a maniac when he learned the truth. Nor could he be convinced that the money was all squandered, insisting that the fugitive would certainly be wise enough lo hold out a wad of it when he skipped. Accordingly, he took what few dollars he could scrape together out of I he wreck, and set off hot-foot in pursuit.

"Luck was against him, though. True, he did finally locate his brother in some out-of-the-way hole down in one of the banana republics, but he reached the place only to learn that his man had died of yellow fever the week before, and, if he had had any money with him, by that time it had, of course, disappeared. The authorities were regretful; but they were compelled to inform the Señor Americano that his esteemed relative had died intestate.

"There was nothing for the disappointed searcher to do but to traipse back home and try to get a fresh start in life—not an easy job either, let me tell you, when a man is over fifty, and settled in his ways.

"He hung around New York for a time without getting hold of anything, and, I guess, had a pretty hard road to travel. You see, his brother's flare-up had created considerable of a muss, and the jewelry merchants were just a little dubious about trusting another of the same name.

"At last the fellow took an alias; but still he didn't seem to catch on, until finally Markles picked him up, and when they opened their jewelry department placed him in charge.

"The strange part of the story, though, is that his experience seems to have changed his whole nature. Whereas he used to be genial and friendly, and exemplary in his habits, now he is morose and sullen, and, as for his conduct, he has become about as crazy over gambling as his brother ever was. There's not a night in the week that he isn't at it, and he rolls 'em high, too. I guess he thinks that is the only way he'll ever get back—"

"Wait a minute," interrupted Janet, whose eyes had been growing wider and wider with interest as the tale proceeded. "Do you think you could remember that name if you heard it again? It wasn't by any chance Van Dorn, was it?"

"By George," exclaimed Brueton, "that is just what it was! That is the very name Hartopp told me was Seymour's own—Theodore Van Dorn. But how did you guess it, Miss McCrea? Had you ever heard the story before?"

"I ought to know it," she replied bitterly, "My mother and I were among the long list of Cornelius Van Dorn's victims. We lost at his hands everything we had in the world."

"Oh, say, that's too bad," sympathized Billy. "I'm awfully sorry that I mentioned the affair. Had I supposed for a minute that you—"

"No," she broke in quickly, "Don't blame yourself unnecessarily. Indeed, I am very glad to have heard what you had to relate. Go on, and tell me interesting things about some of the others in the store. What of Mr. Elliott, for instance?"

Thus spurred on, Brueton plunged into a fresh series of anecdotes; but Janet, although she listened and laughed, seemed for the most part preoccupied and pensive, as though she were deliberating on something apart.

At length, while they were dawdling over their cheese and coffee, she turned to her companion with the abrupt question: "What salary does Mr. Seymour get, Mr. Brueton? Do you know?"

"The same as I do. Two hundred a month."

"And would that suffice to cover the card-playing he does?" Billy laughed.

"Why, often he will drop more than that in a single night." He paused reflectively, "By George, I never thought of that before," he added, "The fellow must have some outside source of revenue. I wonder—"

But Janet was not ready just yet to hear Mr. Brueton's speculations.

"Does Mr. Markle know of his gambling?" she probed.

"Lord, no! There is nothing the old man is more set against than that. He stands ready to bet any amount himself on anything that comes up; but he simply won't have a gambler in his employ. Why, if he thought—"

He interrupted himself suddenly, and a disconcerted look spread over his face.

"You're not thinking of giving him away, are you, Miss McCrea?" he questioned anxiously, "Because it would mean his getting the bounce sure, and I'd never forgive myself—"

"Have no fear, Mr. Brueton," she reassured him, "If Mr. Seymour is doing nothing more serious than gambling, he has little to apprehend at ray hands. I only want to learn where he gets the money to gamble with, and that"—she leaned forward and looked him squarely in the eyes—"you have got to help me find out."

Her own eyes were sparkling, her lips set in a firm, determined line. The atmosphere of depression had entirely vanished from her bearing, and she was alert and vigorous as she laid down her dictum.

Even in the astonishment which overcame him as he grasped her underlying meaning, Brueton found time to admire the delicate rose flush which tinged her olive cheek.

"Why," he gasped excitedly, "you must think then that these robberies at the store&mdaah;"

"Sh-h!" She laid her finger to her lips with quick warning, "Remember we are in a public place. There is no knowing who might overhear."

He sat pondering a moment over the light which had come to him through her words.

"Do you know," he finally announced emphatically, although lowering his voice in obedience to her injunction, "I shouldn't wonder a hit if you were right? More things have been reported missing from his department than from any other in the store, except mine. And his losses, of course, have footed up the most in value."

Again he fell silent, conjecturing upon possibilities; but presently he glanced up at her with a mystified expression on his face.

"How in the devil does he get the stuff out, though?" he asked.

"Ah," she returned, "that is what we shall have to find-out."

FOR a long time they sat discussing the pros and cons of the revelation which had just presented itself to them.

Brueton at first was inclined to be somewhat skeptical; but after talking over the situation with the girl, he was forced to agree that the thieving was the work of some one on the inside and, this point settled, there was no one in the establishment, as Janet pointed out, who possessed equal opportunities with Seymour for the exercise of a predatory activity.

In the first place, he was in charge of the jewelry department, where the stock contained articles of greater value, within less compass, than any other in the store. Secondly, he had hut one assistant, and was consequently exempt for a considerable portion of each day from any danger of espionage.

Third, it was a part of his duties to regulate the various clocks throughout the building, and as there was one of these in each department, and he was supposed to test each one at least once a week, he thus had free range to pick and choose where he would.

"Given the facts that he has had full chance to steal, if he so desired," succinctly summed up Miss McCrea, "and that he has been risking sums of money largely in excess of his known income, and," she added as, an afterthought, "that his brother's knavery would argue a vicious strain in the family, I do not well see how we can be blamed for regarding him with suspicion."

"Well, of course, as you say," admitted Brueton dubiously, "it looks mighty black against him, yet, for all that, I can't get it through my head that old Seymour would be up to such a game. I've got no more cause to like him than you have—he's as sulky and unpleasant to have around as a rainy Monday morning; but I have always sized him up for being on the square.

"Why, I remember, when Dave Thompson was fired—that young assistant cashier the old man caught knocking down, you know—and all of us were getting up a petition to try to have him taken back, Seymour flatly refused to sign it. 'No, sir,' he said, 'I have no sympathy for a thief—I don't care if it's only a postage stamp that he steals—and I'll not put myself in the position of countenancing or excusing any such person. Thompson may bitterly regret his wrong-doing, as you say, and he may have a widowed mother dependent on him for support; but those are matters he could have considered before he yielded to temptation. It is too late to urge them now.'"

"That merely confirms me in my opinion," asserted Janet indignantly, "No one but a rascal would make such a parade of probity; and no one but a thoroughly evil-hearted man could be so hard on a boy who had only erred through his youth and inexperience, and who was honestly repentant.

"But I must be getting home," she added, glancing at her watch, and hastily beginning to gather together her belongings, "You have entertained me so delightfully, Mr. Brueton, that I have not realized how rapidly the time is passing."

"Pshaw," interjected Brueton aggrievedly, "we were just getting 'down to cases.' What is the use of rushing off this way? As it happens, I have a couple of tickets to the theater in my pocket, and I was just thinking we might end up the evening there. We'll be in time for the second act, if we go right over."

"Oh, mother would have a 'conniption' fit if I were to stay out so late," objected Janet, albeit the temptation was strong. "Any time that I do not put in an appearance by half-past nine o'clock, she is immediately convinced that all manner of terrible things have befallen me."

"But that is easily arranged. We can telephone up to her, or even send a messenger boy with a note, if you'd rather."

"Ye—es, I suppose we could "—half-assenting—"but I hate to go anywhere, such a fright as I must look."

Mr. Brueton's extensive knowledge of the foibles of her sex, however, enabled him to reassure her on that score, and he performed the function so flatteringly that her face was suffused with blushes.

"Very well, then," she agreed, "if you'll just let me write a short note to mother."

The play was "The Great Ruby," and the two gazed and listened with enthralled interest while the exciting and intricate plot was gradually unfolded.

It will be remembered that the story hinges on the mysterious disappearance of a famous jewel. Which, while supposed to be stolen, has actually been concealed by its owner during a fit of somnambulism.

"That seems to me a little farfetched," commented Janet, as she chatted to her companion through the entr'acte, "I suppose there is such a thing as sleep-walking, and I know the same motive has been effectively employed in fiction and drama before; but I don't believe that in real life a somnambulist would carry out any such definite and ordered purpose as is here depicted. I fancy rather that the wanderings and the actions of people in that condition must be like the rest of our dreaming—hazy, disjointed, purposeless."

"Oh, I don't know," controverted Brueton eagerly, "There's Markle, for instance. That terrible experience of his several years ago strikes me as a direct refutation of your theory."

"What was that?"

"Haven't you ever heard the story? Why, it seems that one night he dreamed he could not sleep, but got out of bed, lighted the gas, and, wrapping himself in a dressing-gown, sat down to read a book. The dream was a particularly vivid one, and he could afterward recall each of its incidents as though they had actually occurred.

"Presently, however, another member of the family was awakened by an overpowering smell of gas in the house, and, tracing up the odor, found that it led to Markle's room. There the chief sat, just as he had pictured himself in his dream, in dressing-gown and slippers, and with the open book in his lap; but he was sound asleep. Nor was the gas lighted, for upon investigation it was discovered that, although he had turned the cock on full, he had used a match without any head.

"It was a mighty fortunate thing for Markle, I can tell you, that the mistake was detected in time, for the way that deadly vapor was pouring out of the pipe he would have been completely asphyxiated in less than an hour. As it was, I believe, they had to use pretty strenuous methods before they were able to bring him around.

"Why, is Mr. Markle a sleepwalker?" asked Janet in surprised tones.

"Is he? Hadn't you ever heard that about him before? Yes, indeed. He has to have a man tie him up in bed every night; won't go to sleep until he is sure everything is fast, and there's no danger of his taking one of his little midnight strolls."

Janet looked at her companion quizzically. "You're not joking?"

"No, on my honor "—earnestly, "It's the gospel truth, every word of it. You can ask any of the old-timers down at the store, if you don't believe me. Why are you so concerned about it, though? You speak as if it were a matter of vital importance?"

"Did I?"—carelessly, "I suppose it is because I am always interested in the strange or unusual. That is a rather pretty girl over in the right-hand box, don't you think?"

Billy scowled, as though annoyed at her abrupt turning of the subject; but before he could think of a suitable remark to readjust the conversation to its former channel, the curtain had risen on the next act, and he was perforce obliged to remain silent.

Moreover, by the time another opportunity had presented itself for discourse between them, he had evidently thought better about reverting to the topic; for, during the rest of the evening, he only touched on matters of immediate moment and of the slightest consequence—the trivial small-talk of ordinary social interchange.

One exception he made to this. On the way over to the L station he pointed out to her an unpretentious house, midway up the block on a quiet cross street.

"That is 'Tot' Barrison's," he explained, "One of the most exclusive gambling-houses in town. A man has pretty nearly got to be a steel magnate or a Western Senator to get in there; and there's no limit to the play, if a fellow wants to indulge in pyrotechnics. Barrison's, you know, is the joint where young Featherbone made his big losing a few weeks ago, and over which the papers have been making such a row."

"It doesn't look like much of a place from the outside," observed Janet disparagingly.

"Well, you know, it would hardly be good policy for them to shine up the front like a Broadway restaurant I'll promise you, though, that the inside is gaudy enough to suit anybody's taste. Why, there is one picture in the hall that cost $40,000 alone; and the fittings throughout are on a scale of sumptuous magnificence."

He paused, then—

"I suppose Seymour is over there now," he added rather pointedly.

"And when did Mr. Seymour get to be a 'steel magnate or a Western Senator'?" she quoted at him slyly.

"Oh, never fret about Seymour. As I told you, he'll roll 'em just as high as though he had millions. He—"

"And you?" she interrupted. "How did you gain the 'open sesame'? They were directly underneath a street lamp as she asked the question, and she saw a vexed flush steal over his face. He made no attempt at evasion, however, in his answer.

"I suppose you expect me to deny dropping in there occasionally," he smiled, speaking with the semblance of perfect frankness, "but I won't. I met Barrison when he was fixing up the place—we sold him his furniture down at the store, you know—and he invited me to come around whenever I felt like it. I never play myself, of course—can't afford to, in fact; but often I have a friend or so in town who wants to see 'the elephant,' and it's rather convenient to be able to take them in there. They can go home afterward and brag that they've been in the biggest gambling-house in New-York."

Plausible enough, again; if she could only have been satisfied that he was sincere.

"I see," she replied, nodding her head reflectively. Then, as though a sudden idea had presented itself to her: "Your frequent appearance there, then—say, every night or so—would create no particular comment?"

"None at all, I assure you." His eyes bore an amused gleam, as though her words distinctly tickled his risibility, "In fact, I might go there every night in the week, and no one would think anything of it."

"Then I am going to ask you to do me a great favor, Mr. Brueton?" She spoke urgently.

"Anything at all. I shall be only too happy to be able to serve you."

"Will you find out for me what amount of money Seymour risks there, on an average, and also as nearly as possible the total of his losses and winnings?"

Brueton bit his lip.

"I hate to play the spy. Miss McCrea," he finally blurted out uncomfortably; "can't you get some one else to do the job for you? I suppose, of course, the interests of justice demand that all honest people should unite in tracking down a thief, and, from what you tell me, I am inclined to agree with you that Seymour is pretty close to being 'It.' Still, the fellow has never done anything to my hurt personally, and I'll swear I don't want to be the one that has to show him up."

"It is not only in the interests of justice that I ask you to do this, Mr. Brueton," she said in a low tone; "it is also in my interests. Mr. Markle has informed me that unless this mystery is cleared up within three weeks' time, my position will be considered vacant."

"Whe-ew!" whistled Billy Brueton. "That alters the complexion of things, doesn't it?"

They were standing at the door of her boarding-house now, and the young fellow with an impulsive gesture extended his hand.

"You may count on your information, Miss McCrea," he said heartily; "and," he added, "don't you get discouraged. We'll manage to save your job for you, somehow. You know two heads are better than one, even if one is a blockhead."

"Thank you so much, Mr. Brueton," answered Janet simply; but there was a warm smile on her lips, and a tender light in her eyes, as she bade him good-night.

Once inside the door, however, the smile vanished, and the light in her eye became a gleam of mocking triumph.

"I have him," she cried to herself, clenching her fists, "All I had to do was to-give him rope, and he was only too ready to hang himself.

"But I thought he was at least a man," she continued, with a derisive curl to her lip, "There was no need for him to come out and admit that he was the guilty man—although, if he had, I would have saved him.

"Yes, I would," she asseverated fiercely, "even if, thereby, I lost all hope of retaining my position I But he might have spared me his weak fictions about Seymour, and his still more pitiful attempt to cast suspicion at Mr. Markle. Faugh, he disgusts me!"

Yet—strange vagaries of a woman's disposition!—before she, fell asleep that night, her pillow was wet with many tears, and she was sobbing feebly to herself: "If only I could believe that it were not he! If only some other person might prove to be guilty!"

JANET MCCREA'S suddenly declared assumption that the real thief was none other than the man with whom she had passed the evening requires a few words of explanation.

It is true that women, for the most part, disdain those slow and toilsome processes by which the sterner sex is accustomed to reach its conclusions; but from the very slightest foothold, or sometimes from no foothold at all, will leap with one bound to the pinnacle of complete assurance.

Still, in the present case, Miss McCrea's deductions were not so illogical and unfounded as they might appear. Indeed, if one stops to think, it will be seen that exactly the same measure of prejudice which Billy Brueton had so shrewdly brought forth against Seymour could with equal justice be applied to himself.

Janet's suspicion of the young fellow, only partially aroused by the confusion he had manifested regarding the time of his departure from the store, had been rendered active by his inadvertent mention of a bookmaker as one of his intimates, and by his use of the "sporty" expressions with which he so plentifully interlarded his conversation.

Casting about for facts to support this hastily-formed inference of hers, she remembered that his department had almost equaled Seymour's in the extent of its losses; indeed, these two sections seemed to be the favorite stamping-ground of the thief.

Nor, moreover, did the jeweler have any advantage over him in the matter of free range of the building. If Seymour was privileged to visit every nook and corner by reason of his duty in regulating the clocks, Brueton was no less favored by another detail of the management.

It was the custom at Markles' to check up each department every night, both as to the amount of sales and the amount of goods returned. This was to prevent a salesman from swelling the record of his sales by urging customers to take out goods on approval, only to have them brought back on the following day.

The various managers assumed this duty in turn, for a period of three months each; and, as it happened, the function had been assigned to Brueton only a week before the free-booting which had so agitated the establishment first began to be reported.

This process of checking up gave the man engaged upon it, of course, an opportunity to visit every department in the store, and that, too, at an hour when the clerks were hurriedly getting stock in shape, so that they might leave on time, and were consequently less watchful than at other seasons.

Making up his report from the information thus gathered usually detained Brueton for a half or three-quarters of an hour after closing time; and, as Janet reflected, it would be very easy for him during this period to slip Out to a waiting confederate whatsoever he might have picked up on his tour of the establishment.

He could then walk past the lynx-like vision of old John, serene in his innocence of any contraband articles in his possession.

As she recalled the location of Brueton's desk in the furniture department, she realized how easy it would he for him thus to effect communication with an accomplice; for directly behind him was a window opening on a court at the rear of the building. All he would have to do was to open the sash, and by means of a string lower his booty to the person in waiting.

Yet it might even be that he had no associates in the affair. He might have discovered some other exit from the store save that by which all the employees were obliged to pass, and which John so zealously guarded.

And some color was given to this conjecture in her mind by the variance she had that evening noted between his own statement and that of John's in reference to the time of his departure from the place.

But these were matters which could not be definitely determined until she had had an opportunity thoroughly to investigate. What interested her now were the psychological, rather than the actual, proofs of the man's guilt.

"What," she asked herself, "is the first impulse of a criminal, when he finds the net of circumstance being drawn around him, or when for any reason he begins to imagine himself under suspicion? Why, naturally to delude his pursuers and to throw them off his track. And the easiest way to do this, of course, is to direct their suspicions toward some other person.

"That is just exactly what this man has attempted with me," she asserted conclusively, "Fearing that he had given himself away by his bungling explanation about leaving the store, he dragged in by the heels this story concerning Seymour. Then, afraid, perhaps, that I might follow up the clue too closely, he endeavored to palm off on me that ridiculous fling at Mr. Markle. And finally—oh, climax of generosity!—he told me not to be discouraged, and offered me his own valuable assistance!"

She laughed shortly, mirthlessly.

"He help me!" she mocked. "As well expect the fox to help the hound which is chasing him down to his own destruction. No, Mr. William Brueton, I will work out this case alone and single-handed, and I will demonstrate to my own mind by incontrovertible evidence that you, and no one else, are the thief!"

It will be noticed by the observant, however, that Miss McCrea made no mention of demonstrating that important fact to the mind of anybody else; and indeed, whenever the question presented itself to her of delivering up to justice this man she so firmly believed guilty, she perceptibly shrank from its contemplation.

She was determined to prove his knavery to her own satisfaction; as for the enlightenment of others—that, she weakly argued, was a matter for the future to settle.

Yes, it must be confessed that the case, as she built it up, looked dark against Billy Brueton. There were bat three points to be considered; these affirmed, his culpability was practically clinched.

First, did he gamble, and if so, was he now or had he been losing? That would supply a motive.

Second, had he a confederate, or did he possess a secret means of departure from the building? That would answer the pithy question he had propounded concerning Seymour, "How the devil does he get the stuff out?"

Third, if he was the thief, did he sequester the goods on his tour of the various departments just before closing time, or was it at some other season? That could only be determined by watching him, and to this end Miss McCrea felt that she could safely trust her own bright eyes.

Yet, with these facts undetermined, how, it may be wondered, could she be so confident that he was the thief? After all, the proofs against him were no stronger than those against Seymour.

If it should turn out that Brueton was hazarding more money than he could afford, so beyond question was the other man. If Brueton had free run of the different departments, so also had Seymour. If Brueton might have devised some scheme for conjuring the stolen goods out of the building, was it not fair to allow Seymour the same powers of invention?

As far as that goes, how could she be so thoroughly persuaded at this stage of the proceedings that Mr. Markle was not equally open to suspicion with either of them?

He had an unquestioned right to go to any part of his store, day or night, and, picking up whatever he pleased, carry it out of the building.

Why might he not exercise this right when under the stress of his peculiar affliction?

For aught that she could say to the contrary, he might have been doing so, hoarding up the goods in some magpie retreat, the very location of which he would in his waking state be supremely ignorant.

This theory would certainly explain what had hitherto been one of the most puzzling phases of the thefts—that despite a rigid surveillance of the pawn-shops throughout the city, none of the stolen goods had so far been found "in soak."

And was it so utterly absurd as an hypothesis, after all? If the medical works are to be believed, stranger instances of somnambulistic extravagance than this are matters of authentic record.

Yes, it may readily be asked, why was Janet McCrea so incontrovertibly bent on proving Billy Brueton the Ethiopian in this particular woodpile?

Chiefly, it' must be known, for the very paradoxical reason that he above all others was the one she wished to see untainted by the slightest stigma of suspicion.

THE next evening at closing time Janet McCrea made her first move in the strategic campaign which she had planned to convince herself of the guilt of Billy Brueton.

Markle Brothers' store, it should be explained, occupied a ton-story building, fronting an entire block on Sixth Avenue, and running back from that thoroughfare a distance of between three and four hundred feet.

The furniture department filled the entire seventh floor, except for a certain restricted space set aside as a restaurant, and, as already described, the manager's desk was in the rear, directly beside a window opening upon a court below.

The eighth floor was devoted to shoes, the ninth to groceries, and the tenth was a sort of lumber-room, given up to the storage of surplus stock.

As the clocks throughout the store pointed to five, Janet stealthily made her way to this top loft, proceeding all unobserved up from the fifth floor by means of the seldom used staircase.

Arriving at her destination, she refrained from striking a light for fear the beams might be observed by some one about the establishment and cause an investigation; but, guided only by the faint illumination which crept in through the dingy windows, stumbled along through the narrow aisles, piled high on either side with boxes and cases of goods.

Thus she reached the back wall and took her stand by the center window, directly over that which, if her calculations were to prove true, was the one used by Brueton in removing his stolen plunder from the building.

The damp, heavy weather still continued, and from her lofty eyrie she could look out to where the lurid yellow glow of the lights over on Broadway was reflected against the leaden sky. Far down below her, the wet, shiny roofs of the houses to the roar of Markles' glistened as black and sleek as the backs of a school of porpoises just risen from the waves, and still farther down was the little patch of courtyard, gray and shadowy now in the mist and dusk of the evening.

There was still sufficient light, however, she decided, to enable her to make out the figure of a man, if one should appear in the enclosure, and also to detect the passing out to him of any goods from the store, if such an operation should be attempted.

Accordingly, she settled herself to her vigil with lively hopes of a successful outcome. The moments passed, and the lessening of the sounds which came up to her from below indicated the gradual cessation of work throughout the big emporium.

She heard the clerks in the grocery department directly underneath her tramping out, exchanging quips and badinage as they went, and then presently came the echoing footfalls of the watchman as he made his first round, extinguishing the lights, and seeing that everything was snug for the night.

There was only one elevator running now, and at length this, too, ceased its punctuated grind. The building was still.

Keenly alert as she was to the sounds which marked for her the passage of time, Janet nevertheless kept her eyes steadily glued to the paved square of court so far below her, and now that the moment had come when if anything were to occur developments must be expected, she leaned far out over the casement and fairly strained her eyes in her eager excitement as she searched its misty depths.

Ah! At last! The little gate in the high board fence which shut off the court from the street was cautiously opened, and a man slipped through.

He peered about for a moment as though to make sure that all was safe; and then, rapidly making his way across the yard, took his stand in the shadow of some empty boxes piled up there.

Owing to the altitude from which she was observing him, and also hindered by the gloom and fog of the evening, Janet could gain no very distinct idea of his appearance; yet the realization came to her as she watched him cross over from the gate, that there was something remarkably familiar to her in the fellow's walk and movements.

A project, born of this half recognition, came to her as she leaned out and strove vainly to penetrate the murky atmosphere.

Why not hurry down to the place where the man came in, and where he must eventually go out? Through the cracks in the fence she could watch her quarry as well or even better than from her present station; could see if Brueton should lower down a package to the waiting confederate, and in addition could catch a glimpse of the strangers face as he came through the gate—perhaps be able to follow him to the cache where he stored the stolen goods.

Without delay, she started to carry her new plan into effect.

As rapidly as possible, she threaded her way through the network of crowded aisles in the lumber-room, and when she had reached the door removed her shoes and fairly flew down the long succession of iron staircases.

At the seventh floor she paused a moment and peered cautiously around the partition to see if Brueton was still at work. A quick glance of astonished surprise broke from her lips.

The furniture department was utterly silent and deserted; the manager was not at his desk, nor, for that matter, anywhere else about the place.

"Ah," she swiftly reflected, "the interchange of loot has already been effected. While I was stumbling around in the upper loft, and was sneaking so softly down the stairway, Brueton has passed out his spoils to his accomplice and has then taken himself off. Through sheer carelessness I have lost the chance of clinching my evidence against him."

She could almost have cried in her disappointment as she sat down, foiled and baffled, on the top step of the landing and began slowly to pull on her shoes. But she had a strain of adaptability in her nature which induced her always to search for the best in any situation, and as she pondered a new idea broke upon her.

Perhaps it was not too late after all to extract some result from the circumstance. It was barely possible that the confederate at least might still be lingering in the courtyard, and that she might yet overhaul him and get the coveted glance at his features.

It would do no harm anyway to make sure before she began to weep over her spilt milk.

To decide with Janet was to act. She gathered up her skirts in her two hands, and, paying no attention now to the clattering of her footsteps, tore down the six remaining flights as though all the furies were in pursuit.

Attracted by the noise of her stoutly soled shoes upon the iron stairway, a man, who had almost reached the door, stopped and turned back to see who could be approaching at such a runaway gait.

Too late to avoid him, Janet saw the fellow and recognized, to her consternation, that it was none other than Billy Brueton.

A glance of startled alarm swept over his face as he, too, recognized her.

"Why, it is Miss McCrea!" he exclaimed, running forward a step or two to meet her, "What's the matter? Is the store on fire? Are you in any trouble?"

"No; everything is all right," she gasped, "only I am in a great hurry. Please don't stop me now; I haven't time to explain."

"But," he urged, catching step with her and hastening along at her side, "perhaps I may be able to help you."

"No, I thank you," she returned pantingly, "this is something I must attend to myself."

"Don't refuse my assistance, please, Miss McCrea," he persisted, "if I can be of any aid. I am always only too happy—"

His eagerness, however, only aroused her to anger. The thought flashed through her mind that possibly he might have fathomed the purpose of her headlong flight, and be now endeavoring to delay her.

She turned on him with impatient asperity.

"Mr. Brueton, I have told you twice already that I could not accept your assistance, nor could I stop now to explain my hurry. Is that sufficient or shall I have to express myself in still plainer terms?"

She stopped short, rendered a little contrite by the flush which showed on his good-humored face.

"Really, I thank you," she went on more kindly; "but this is not an occasion where any one can help."

"All right. Miss McCrea," responded Billy cheerily, quite appeased by her later words; "go your own gait, bow, and I'll see if I can't find some other way to serve you."

He lifted his hat; but she, scarcely halting to return his smile, was once more speeding toward the door. Out of it she scurried, around the corner, and then down the unfrequented cross-street on which opened the gate to the court.

Was she too late? Had this delay proved fatal to her hopes? By any fortunate chance, could the man still be lingering there after all this time?

Her thoughts and fears were running on as fast as her flying feet.

Reaching at last the high board fence which shut off the narrow enclosure from the street, she Breathlessly applied her eye to a convenient knot hole and took a quick survey of the situation.

Ah I Her strenuous efforts were not to go unrewarded after all. The man was still there, lurking in the shadow of the boxes.

The street, as it luckily happened, was quite deserted for the entire block, not even a policeman was in sight; so Janet had full opportunity to make a complete and uninterrupted inspection.

She could not see the man very well, it is true, for his figure for the most part was concealed by the bulky packing cases behind which he was crouching; but, as well as she could make out, he was stooping over examining something on the ground close by the wall.

He kept lighting matches, the tiny flame of each creating, a sort of hazy, yellow sphere of radiance in the fog.

"He is evidently appraising his loot for the night, and is rearranging it into parcels more convenient for him to carry," decided Janet shrewdly, "If he could only be arrested now, with the goods actually on him, there would be no difficulty about proving his guilt."

She questioned for a moment whether it were not the wiser plan to summon a policeman and have the arrest made then and there; but, although the temptation was great, she finally concluded to refrain, arguing that the man, if arrested, might refuse to disclose the hiding place of the great mass of goods already stolen, or even, what she considered of much greater importance, the identity of his associate.

No, she determined, it would be vastly preferable to let this fellow, probably nothing more than a tool at the best, go for the present, only trying to snatch a glimpse at his features, or, if possible, follow him to the store-house where he disposed of his booty. Then, through the evidence thus acquired, she would be in a position to lay a trap for the catching of bigger game.

Indeed, by the time she had definitely arrived at this conclusion, no other course was left open to her, for there was still no policeman anywhere in sight, and the man was manifestly preparing to take his departure.

He peered out cautiously from behind his shelter of boxes, and, crooking his arm around a large bundle which he picked up, began cautiously stealing toward the exit.

Janet ran back a few paces down the street, and then came on again in a slow, unconcerned saunter, endeavoring to so time herself that she should meet the intruder face to face just when he opened the gate.

Her plan worked to a mathematical perfection. She was not more than a yard away when the gate swung back on its hinges; and with on air of jaunty nonchalance the fellow stepped forth into the full glare of the electric light on a nearby lamp-post.

Janet bent eagerly forward to make her swift scrutiny of his lineaments; but when she actually saw the man's face she was so stricken with amazement that she stopped short in her tracks, hardly able to believe the evidence of her own senses.

For instead of the burly figure and the low-browed, sullen visage of the professional thief whom she had expected to behold, the light revealed a sharp, clear-cut profile, the formal side-whiskers, and the immaculate attire of Jasper Markle.

He gave a little start as he recognized Janet, but instantly recovered himself.

"Ah, Miss McCrea," he said with bland inquiry, "just going home? You are late to-night, are you not?"

For a moment Janet wavered between a desire equally strong to cry and to laugh; the outcome was so disappointing to all her high flown hopes, and yet to have pictured Jasper Markle in the role of a burglar was so irresistibly ludicrous.

Then the appeal to her risibilities gained' the upper hand and she began laughing—almost hysterically, it must be confessed, in her reaction from the strain of excitement under which she had been laboring.

Mr. Markle gazed at her in grave surprise.

"Will you kindly explain, Miss McCrea?" he broke in drily, "I see nothing so remarkably mirth-provoking in our happening to meet casually on the street.

"Oh, you don't understand, Mr. Markle," she exclaimed, sobered by the offense so manifest in his tone. "You see, I took you for the thief."

He glanced sharply at her, and a quick frown gathered behind the bow of his gold-rimmed glasses. Was it of annoyance over her mistaken surmise?

"Yes," went on Janet, not noticing his momentary perturbation, "I saw you lurking there in the shadow of the building, and thought you were a burglar trying to effect an entrance."

She deemed it unnecessary at this time to explain the full scope of her suspicions.

"Oh," he rejoined in a mollified tone, and laughing, too, although not very heartily, "Well, I don't know that I can blame you; my actions must have appeared a little questionable to any one who did not understand them. I assure you, though "—with mock solemnity—"my intentions were not in the least nefarious.

"You see," he continued, "one of the porters told me this morning that a leaky water-pipe was undermining our rear wall; but I forgot about it until after I had started home. Then I returned to make an examination, so that, if necessary, repairs could he commenced at once.

"My bundle"—patting the bulky parcel under his arm—"is some things I happened to be taking home from the store.

"You are fully satisfied now, I hope," he concluded with a quizzical smile, "that it is not your duty to give me in charge?"

"Quite so," she answered; "and although I don't wish you any bad luck. Mr. Markle, I must say that for my own sake I am sorry you didn't turn out to be the thief."

Then she bade him good-night and turned back toward Sixth Avenue with the mystery apparently still as far from solution as ever.

Jasper Markle stood watching her until she had rounded the corner, and while he did so there rested on his lips just the suspicion of a faint, cynical smile.

THE following noon Brueton halted Janet as she was passing through his department on her way out from lunch, and, drawing her aside with an air of great secrecy, asked her if she would come to his desk after closing time that evening, as he had information of the greatest moment to impart to her.

She of course acquiesced, but all the rest of the afternoon she kept puzzling her brains over the invitation, wondering what it could possibly be that he had to tell her.

Once, indeed, the conception did come to her mind that having discovered how hot she was upon his trail, he might be luring her there in order to put her out of the way. All sorts of tragic possibilities flitted through her brain, and she was strongly tempted for the moment to forego such a hazardous appointment.

But a little common sense reflection soon dissipated all these melodramatic fancies.

In the first place, she could not conceive of Billy Brueton hurting a fly; and in the second, even though he were the most murderous scoundrel unhanged, she did not see how he possibly could have any opportunity to do her harm.

Nor, it may be added, when she actually appeared at the tryst, did he display any of the characteristics of the heavy villain who has lured an unsuspecting maiden to her doom.

True, he was smoking a cigarette when she entered; but us he threw it away immediately upon her arrival, this ought not to be allowed to count against him. No, it must be confessed, he neither frowned nor stamped up and down the floor, nor ejaculated "Ha!" at her from between his clenched teeth.

On the other hand, he was distinctly joyous and elated, bubbling over with importance at the nature of the tidings he had to offer.

"Do you know," he said impressively, when greetings had been exchanged, and they were settled down to a confidential talk, "I really believe I've got this thing straightened out for you? Talk about Sherlock Holmes, and Le Coq, and the rest of that bunch! Why, they aren't in it when your Uncle William comes out on the track."

"But what have you discovered?" demanded Janet, impatiently interrupting this vainglorious apostrophe.

"Don't be in a hurry," chided Billy, "Just give me my head a minute. Miss McCrea, and let me take the hurdles my own way, and you'll find that I'll come out ahead at the wire. You know I told you I'd back myself to scheme out some plan to help you on this deal, and my old noddle has been working overtime ever since to try to make good.

"First thing I did was to go over to 'Tot' Barrison's last night, and get confidential and chummy with the 'main squeeze' himself. You must understand. Tot thinks he's an art critic for fair; so I talked old masters to him till I was pretty near blue in the face. What I didn't pretend to know about Murillo and Velasquez and Tintoretto and that push isn't down in the books.

"Well, he came right up to the bait, and when I saw I had him fixed, I switched off on to the subject of high-rollers, and remarked casually that Seymour was about as game as any I ever saw around there.

"'Yes,' said Tot, 'he plays high enough, and he loses sufficiently frequent to satisfy almost any gambling-house keeper; but to tell you the truth, I don't like to have the fellow coming to my place.'

"'Why not?' said I. 'He seems to be a pretty stout loser. I don't believe he's the kind that would put up a squeal, if he happened to get stung.'

"'Oh, its not that that I'm afraid of,' said Tot; 'but I can't understand where the fellow gets his money from. I understand he is only on salary in some department store down town; yet he'll drop from two to ten thousand dollars here in an evening, and when he goes out gives a check for what he owes, as cool as a cucumber. I'm scared that there'll be a big scandal about him some day, and I'll get mixed up in it.'

"'By the way,' he added, 'you're in the same store he is, aren't you? Don't you know where he gets his paws on all this coin he is handling?'

"'Not me,' said I. You see I was playing to get information, not to give any away. 'I've have enough to do, looking to see where mine is coming from, without bothering my head about other people's methods. Are Seymour's checks always good?' I asked.

"'As good as old wheat in the mill. Here's one of 'em now,' and he fished out of his vest pocket for me a cheek for $5,000, signed by Seymour and made out on the Bank of Nicaragua.

"'Does that cover all his losses to you?' I said.

"He only laughed and looked wise, and when I pressed him to find out how much Seymour had lost altogether, he would only answer, 'That'd be telling.'

"Finally, however, after I'd joshed and jollied him for pretty near an hour, he did let out to me that, being sort of afraid of Seymour, he had kept a record of his play from the first, and he showed me the figures. Taking the whole period, winnings and losses together, Seymour, as I figure it, is just about $10,000 to the bad.

"Now, having discovered this. Miss McCrea, I began to put two and two together, for the amount, you will see, just about tallies with the value of the goods that have been stolen out of the store. I know that Seymour doesn't gamble anywhere else except at Barrison's, so consequently the money lost there is not winnings that he has made at other places.

"Furthermore, it is a well known fact that the man didn't have a cent to his name when Markle picked him up and put him in charge down here; and we both realize that his salary isn't furnishing him the wherewithal for his extravagance. Therefore, since he must have some outside source of revenue, and the only possible source as far as I can see is by robbing the store, Seymour beyond any question must be the robber.

"I reasoned this far, and then it struck me that I wasn't reaching any remarkably startling conclusions; for, if you will remember, we both arrived at practically the same inference the other night over in the restaurant.

"The question which kept stumping me was the same one that stumped us then: 'How the dickens does he get the stuff out?'

"Well, I went home and I puzzled and bothered my head over the thing all night, and still I didn't see how it was possible for him to do it. I studied over it at my breakfast, and all the way down to the store next morning, and still I was hopelessly muddled; and then along came a little incident which made the whole graft to me as plain as daylight."

"Yes," said Janet, leaning forward interestedly. "Go on."

"Well, about ten o'clock, when everything had got to running smoothly for the day, and I was here at ray desk, figuring on an order I was getting ready to send out, in came Seymour.

"'Brueton,' he said, 'I am going to take that clock of yours down to my department to regulate it, and if I don't find time to fix it to-day I'll take it home with me this evening, and have it back here for you early in the morning.'

"That's what he always says, and heretofore I've never paid any attention to it; but this time it set me thinking.

"' That fellow claims to regulate our clocks for us at night,' I said to myself, 'and they are always brought back to us in good condition in the morning; yet how in the world does he ever find time to do the work when he spends every night of his life over at Tot Barrison's.'

"Then the whole scheme came to me, and I saw how easily Mr. Foxy Grandpa had worked us. Oh, I tell you we have been the prize package of lobsters, if any gang ever was."

"But I still don't understand," broke in Janet perplexedly, "How did the regulating of the clocks assist him in getting his plunder out of the store?"

"Why, don't you see?" said Billy.

"It's as plain as the nose on your face. He takes my clock down to his workshop, and, being an extraordinarily skilful mechanic, he fixes it up in short order. Then, while his assistant is out of the way, he hides it somewhere about his diggings, and fills up an empty box with the stuff he has managed to steal.

"Last of all, he gets a pass from the chief to take home a clock to regulate during the evening, and with this he slides the stolen goods past old John as slick as a whistle. Of course John never thinks of looking in the box to see whether the clock is really there or not."

"Oh, I see," ejaculated Janet, a sudden comprehension breaking in upon her, "It is wonderfully simple, when one comes to think about it."

"Isn't it? Easy as rolling off a log; and no one who isn't on to Seymour's habits would ever think of suspecting him.

"You see," he continued, "what clinches the case again him, and makes suspicion certainty, is the fact that the thefts always occur in each department on the day that its clock is being regulated. I confirmed this as to my own department as soon as my suspicions of his method were aroused, and afterward by a little quiet inquiry learned that the same was true of all the other deportments.

"For instance, this evening in looking over my stock I find that a valuable teakwood taboret is missing; you'll probably get a report of the loss tomorrow morning. Now, I have not the slightest doubt that that taboret went out of the store this evening in my clock-box, while all the time the clock which belongs there is safely reposing in some out-of-the-way corner down in the jewelry department.

"So all you've got to do now, Miss McCrea," he concluded, rising from his desk as if to terminate the interview, "is to nail our friend Seymour the next time he leaves the store with a clock-box under his arm. What do you think of me as a detective, anyway?"

"Think of you?" repeated Janet, "Why, I think you are just splendid. The clever way you have worked this thing out simply throws me into the depths of humiliation. Here I have been addling my brains over the problem for nearly two months, and you sail in and solve it in a single evening. Why, it is enough to make me hide my diminished head forever."

"Oh, now. Miss McCrea," protested Billy, flushing modestly under her praise, "It wasn't really any great show of cuteness on my part. It was simply a bit of luck. All there was to it was that I happened to know Seymour's habits. Given that as a starting point, and anybody could have worked out the combination."

"No," she insisted, "I won't have you belittling your prowess. You have accomplished a great piece of detective work, and you should have your full share of the glory. I intend to see—"

"Hold on a minute," broken in Brueton earnestly. "I want to ask that my part in this business remain an inviolate secret between you and me. If there is any credit due me for the little I have been able to accomplish, I prefer not to claim it.

"Really, Miss McCrea, I don't. I have my own reasons for it, and I think they are good ones; so I tell you frankly and candidly that it will be the biggest kind of a favor to me if you just keep my name out of the whole transaction. Let it, as I say, be a secret between us two."

He was so evidently sincere in his request, so manifestly averse to receiving any of the laurels, that after some demur Janet ultimately assented to his wish, and promised him his name should not be mentioned.

"I can only then extend my own most heartfelt thanks, Mr. Brueton," she said warmly; "and even you cannot realize how grateful those thanks are. The clearing up of this affair means more to me in many ways than anybody else can imagine."

And, indeed, it did; for it removed utterly from her mind the suspicions which had rankled there against Billy Brueton; and she had wanted so much to believe him innocent, had so longed to feel that she could truly trust and respect him.

He accompanied her home; and as they journeyed together on the crowded elevated trains, and sauntered side by side through the jostling Harlem streets, her heart was singing a paean of gladness and thanksgiving.

True, woman-like, she pilloried herself for the unjust doubts she had entertained concerning him, and consequently endeavored to offer recompense by displaying to him the very tenderest and sweetest side of her nature; but nevertheless the world all of a sudden seemed very glad and good to her.

The weather had completely changed, and there was a foretaste of spring in the air. In the gathering dusk a baby moon and a few pale stars were beginning to show against the cloudless sky.

All nature seemed happy, peaceful, and at rest; for, with Janet, the doubts and suspicions which had so tormented her were stilled at last, and she knew that Billy Brueton was all right.

EARLY the next morning Janet McCrea started in on a busy day. In fact, she began operations at the breakfast table, and her first objective point seemed to be the reduction of young Mr. Blair, who sat across from her, to the pitch of absolute imbecility.

This youth had for some time past been in the most violent throes of "puppy-love," the object upon whom he had centered his callow affection being none other than Janet herself.

She fully recognized the symptoms of his malady, and had hitherto treated him with an amused toleration, well knowing that in time he would recover and would then thank her for having refused the tender of his bleeding heart; but this morning, for purposes of her own, she adopted totally different tactics.

Indeed, she openly coquetted with him. Across the board "soft eyes looked love to eyes which spoke again;" and over the matutinal coffee and eggs she plied a whole battery of feminine wiles.

So shameless, in fact, was her flirtation that the old maids about the table sniffed at her in a chorus of scandalized horror, and Blair fast lapsed into a state of fatuous idiocy.

"Won't you escort me down-town, Mr. Blair?" she observed, with timid, appealing girlishness as they rose from the meal together. "One has such a dreadful time in those crowded cars unless one has a man along to act as protector."

Blair straightened up to fully an inch more than his normal height, and swelled out his narrow chest until he looked like a diminutive pouter pigeon.

He never stopped to think that Miss McCrea had gone forth every morning since he had known her alone and unattended. He only heard the call of shrinking femininity to his masculine chivalry, and he was only too ready to respond.