RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

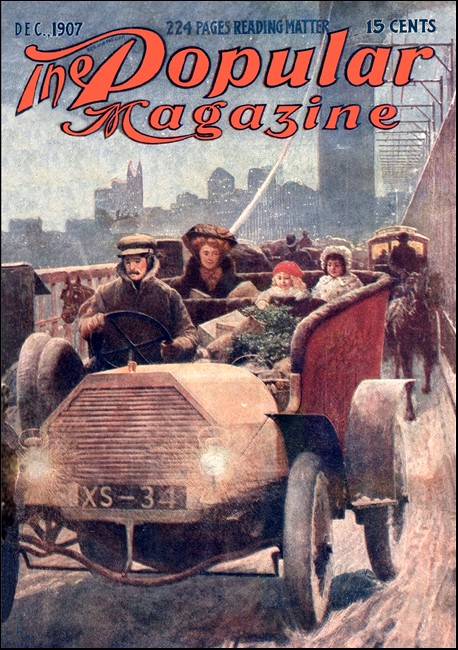

The Popular Magazine, December 1907

with "The Outlaw"

Magnanimity and generosity are hardly associated with the virtues of an outlaw on whose body, dead or alive, a price of ten thousand dollars is placed. But circumstances play havoc in the career of some, and a woman has not unfrequently proved the undoing of a good and "white" man. The good in the wont never dies and often, at the supreme moment, it manifests itself.

IN the beginning of it Lee Allan was not much out of the common; just a big, wire-muscled, care-free cowboy, with much skill in the taming of broncs, and with always a certain reckless light deep down in his hazel eyes—if only one knew enough to look for it. But there was nothing particularly reckless in his behavior, for all that. He rode and shot better than most men, and when he gambled he did not often lose; he was not given to brawling, and men liked him and knew him for a "square" man.

Then, quite unexpectedly, he fell in love. Always before, women bad been mere pleasant incidents which were not worth much worry or loss of sleep, so that just at first Lee didn't quite know what ailed him. With him, to love at all was to love much, and to foolishly place the woman high up on a pedestal and do homage as a man sometimes does believing that he has found the unfindable—a human being with no faults whatever. This is all very uplifting—until that disastrous time when comes disillusionment; then it is a toss-up whether the lesson is going to prove a blessing or a curse.

Lee Allan loved the girl as wholeheartedly as a man can—and for a time he held her fancy and was happy. He was straight and tall and good to look upon, and the reckless flicker just back of his eyes piqued her interest a bit.

She liked to look into them and speculate upon the real man of him, and to feel that she held complete mastery over his life. It flatters a girl to know that a man has stopped gambling for her sake, and that he is living soberly and virtuously simply because of her.

She even went so far as to think seriously of marrying him, and to give him a promise—with those mental reservations which play the mischief, sometimes. Lee, taking her at her word, and not knowing anything about her mental amendments, naturally thought the matter settled, and was filled with a great content—until some one told him to look out for Dick Ridgeman, the banker's son, and hinted complications in Lee's smooth little love-affair. Lee went straight to the girl, caught her lying to him, and started blindly out to find Dick Ridgeman.

He found him—a blase young fellow; his own match, so far as size and strength counted. Lee was just a primitive young man at heart, and he thought he was fighting for his own. They went at it savagely, with clenched teeth showing in that mirthless grin which speaks of rage and of muscles strung taut for combat. With bare fists, it was; a fair fight, with the weaker due to get soundly thrashed for his pains—until Dick Ridgeman reached backward with his right hand suggestively, when they stood free of each other for an instant. Then Lee drew his own gun and shot to kill before the other had quite brought his gun to the aiming point. It seems unnecessary to add that Lee Allan, the quickest and straightest shot in the county, succeeded in killing.

His first thought then was to see the girl and tell her; after that would be time to go—or to give himself up, he did not quite know which. The girl seemed, frightened and horrified when he told her, but she clung to him, and begged him to wait. She would get him a lunch before he started on his long ride—just a cup of coffee, in case he must ride farther and faster than he thought. If he loved her, she said, he would let her do so much for him.

Lee waited, and considered whether it were worth while running away at all; still, it was nice to be petted and waited upon, even if he had been unlucky enough to shoot a man; it showed that the girl really cared for him, after all. And to Lee that overtopped everything, just then; he had so lately been almost convinced that she did not care.

While he was waiting, determined to tell her that he would not run, the sheriff walked in and arrested him. Lee had forgotten that the sheriff lived just around the corner—but it really made no difference, since he had meant to surrender, anyway. So he comforted the girl, and told her not to worry about him; he'd come out all right.

Rut he didn't. At the trial—and because it was the banker's son he had killed, the trial came very soon—he had his first real shock. The girl appeared as a witness, and she appeared for the prosecution.

Lee didn't quite understand, just at first. When she told the jury that she had been engaged to Dick Ridgeman, Lee stared at her incredulously. When she admitted—under question, it is true—that Lee had threatened to "fix Dick Ridgeman so he wouldn't bother anybody," he caught his breath. It was true, and not true. He remembered telling her that he would fix Ridgeman so he wouldn't want to bother her for a while, which was not quite the same. But when it came out that she herself bad sent word to the sheriff that he was with her, something went wrong in the heart of Lee Allan, and the world became full of a great, unnamable bitterness.

For all that, he sat quite still, and the reporter only transcribed that "the prisoner winced perceptibly once or twice, when Miss Mabel Thomas was giving her testimony, but otherwise he appeared quite unmoved." When a man received the crudest blow of his life, it speaks well for his fortitude if he only winces once or twice.

Even then, if they had given him justice—but they did not. He had killed the son of the Honorable John R. Ridgeman, the great man of Colton; and Lee Allan was just a well-meaning, hot-tempered, daredevil cow-puncher. They gave him ninety-nine years—convicting him of murder—and told him how fortunate he was, and how lenient were they, that he was not to be hanged.

That night Lee twisted two bars in his cell window and escaped, leaving a characteristically brief and comprehensive note behind. If you want to know the exact words, they were these:

Damn the law and the lawyers! It's all a rotten fake—and your jail ain't much better. It's me to the wild bunch. Lee Allan.

To the "wild bunch" he certainly went. The first reward for his capture was only a paltry thousand—because they did not yet know their man. But when a posse, after riding far and fast on his trail, turned back and suddenly found themselves ambushed in a narrow gulley when they emerged finally from the trap with every man of them painfully but not permanently crippled—Lee was certainly an artist with a gun—the reward jumped to five thousand, and the fugitive became a man of importance in the county.

A month later, when the sheriff and his deputy met him face to face in the Bad-lands, and the sheriff was brought back to the coroner's office by his badly frightened deputy who had a bullet-hole in the fleshy part of his right arm, the law awoke to the fact that it had a bad man to deal with; a very bad man, for whose body, dead or alive, five thousand dollars was not considered too high a price. The Honorable John R. Ridgeman doubled the amount, so that Lee Allan was worth just ten thousand dollars to the man who succeeded in capturing him.

After that he became alternately the hunted and the hunter. He must have had friends who stood by him—cowboys are a clannish lot—foe he never seemed to lack ammunition, and his rifle was remarkably accurate at long range, as more than one enterprising outlaw-trailer could testify, with the corroborative evidence of bullet-holes. More than that, he seemed always abreast of the news, and undoubtedly knew of the large reward.

For some months the Had-lands witnessed a desultory war at long range, and always with the same result. Men who regarded covetously the ten thousand went boldly out to slay and spare not; without exception, they returned more or less painfully wounded, and one or two were brought back to the coroner.

Lee Allan persisted in remaining distressingly alive, and in a year he had that part of the Had-lands practically to himself. It began to look very much as if the ten thousand must go begging indefinitely.

Two sheriffs had been disposed of, and the third was laughed at when he told his constituents that he would capture Lee Allan or be killed by him. He was two months in office, and had been kept very busy overhauling a gang of horse-thieves, so that the public waited curiously and a bit impatiently for the grand encounter, and speculated much upon the result. In the meantime, Lee Allan was left very much to himself, with not a soul lo shoot at—which must have been wearisome to the last degree.

Colton is not what one might call a large or important town, and at certain seasons of the year it is insufferably dull; at certain hours of those seasons it is even duller, which is the way of "cow-towns" in midsummer.

It was at such an hour that the Honorable John R. Ridgeman stood quite alone behind the cashier's wicket in his bank; for the bank was quite as small and unimportant as the town, ami there was little business transacted between shipping-seasons.

When the cashier went to his lunch, the Honorable John R. often took his place for an hour or so. He was doing some aimless figuring upon a blotter when a stranger opened the door and walked in composedly, bringing with him an indefinable atmosphere of the range-land.

At the first glance the Honorable John passed him over casually as some small cattle-owner, perhaps wanting a loan. At the second, his mouth half-opened and his face became the color of stale dough. He reached out nervously for a revolver which lay always conveniently near, but the stranger laughed unpleasantly; the Honorable John drew back his hand guiltily and stared at him, quite frightened and helpless.

"I hear you've had a reward out for Lee Allan for quite a spell now," began the fellow nonchalantly. "And you stand good for half. Ten thousand dollars for him, dead or alive—that right?"

The Honorable John ran the tip of a nervous tongue along his dry lips, which even then refused him speech. He answered with a queer, convulsive little nod.

"Yuh had it up a long time; seems too bad yuh ain't had a chance to pay it out to some enterprising varmint. I've brought your man in—and he's just about as live as need be. Cough up that ten thousand, old-timer. Yuh won't have another chance—not in a thousand years."

The Honorable John "coughed up." That is, he began shoving bundles of bank-notes under the wicket, till Lee Allan stopped him impatiently.

"No, thank yuh. I'll take the gold."

"Eh—excuse me," mumbled the Honorable John quite humbly for so great a man, and went for the gold—but not alone. Lee Allan very calmly went with him to the vault, carrying his gun ready for instant use in his right hand. The Honorable John fairly trotted, so great was his anxiety to get that ten thousand.

Ten thousand dollars in gold is rather heavy—heavier, perhaps, than Lee had expected, though he did not say as much. He lifted the bags, slipped them into a larger one, which he took from his pocket, and smiled whimsically. The Honorable John could see nothing funny about it, for he was still facing the gun and all that it suggested; he still wore the stale-dough complexion, and his manner was ill at case.

"It's lucky yuh didn't make the offer twenty thousand," grinned Lee. "I'd 'a' had to make two trips after it—and by the looks, your nerves wouldn't stand for another visit, old-timer. Yuh needn't be scared. Yuh ought to be glad to see me—the way you've been mourning around over my absence. Do I look good to yuh ten thousand dollars' worth? Well, so long. Yuh likely won't meet me again for some time. This'll last a while; rent's cheap down in the Bad-lands, and a man don't blow much money there."

He had tied the loose top of the bag into a hard knot, working deftly with his left hand. Now he pushed the Honorable John R. Ridgeman into the vault, closed the door, and walked out of the bank as calmly as he had entered.

Outside, he walked quietly down a side street toward the river, where he had left a boat drawn up on the bank. His revolver he had slipped inside his trousers band, and the bag of gold he carried upon his left shoulder. Figuratively, he looked the whole world in the face, for he made not the slightest attempt at concealment.

A saloon-keeper, standing outside his empty saloon, saw him disappear around a corner, and stared incredulously. Surely, it was nothing more than a remarkable resemblance, he thought—though it would be hard to mistake that tall, straight-limbed figure or the proud set of his head. He stood looking at the corner and wondering if his eyes had tricked him.

Aside from that, no one saw him except a woman who came to the door of her shack to throw out a pan of water. Lee was passing within fifty feet of her, and as she stopped and stared, as had done the saloon-keeper, Lee looked up and smiled at her astonishment. Inwardly he said: "Lord, what a pair of feet!" The woman's feet were large, but one would scarcely expect an outlaw who had just claimed and received the reward upon his own head, to notice a woman's feet.

On the river-bank, half a dozen children were playing around the boat "Here! yuh better pile out uh that, kids," he commanded, but gently. They stood back and eyed him curiously while he placed the bag in the boat and thrust an oar into the soft clay bank. He was positive that the oldest boy recognized him, but he did not hurry. When the boat floated clear, he sat down and adjusted the oars, looked up at the staring group, and held the oars poised in air.

"Say, kids!" he called. "Yuh better run home and tell your dads that the Honorable John R. Ridgeman is shut up in his bank-vault, and I don't believe it's any too well ventilated. Hike along, before he uses up what air there is. And, say, tell that little tin sheriff uh yours that I'll leave him a note in this boat. Get a hustle on, now!"

He dipped the oars unconcernedly, threw his straight shoulders backward, and began to row deliberately but with strokes which sent the bow leaping over the water like a cat running through snow. His hat, dimpled in true cowboy fashion, was pushed back on his head, and his forehead was very white. As he watched the children scurry up the bank and race back to the town, he laughed; but in his eyes the old, daredevil light burned a steady flame, and deeper than the laugh sounded the note of bitterness that the last two years had bred.

The sheriff was not in town, and it was two hours before he was notified; it was three before he reached the place where was moored the boat. Three hours would carry the outlaw far toward his hide-out in that jumble of barren hills which was the Bad-lands, so the sheriff went about his investigation deliberately. Allan's message had been given him verbatim, and he looked first for the note. It was easily found, and his name, Bob Farrow, was scribbled upon the outside, so there could be no mistake. Also there was no mistaking the utter scorn of law in the few lines of the message, which was this:

Come on down and play tag with me—if you ain't afraid. Bring a possy along, so I can practise up shooting. If you come alone I won't shoot you. Ill just tie you to a tree and let you starve to death. You'll come a-running—I don't think!

Lee Allan.

Bob Farrow was not a coward. I le straightened so suddenly that the boat rocked under him and little waves licked along the sides like gray tongues. He gritted his teeth and swore.

"I'll go—and I'll go alone. Thinks he can bluff me, does he? He'll eat this note—or I don't come back."

"What does he say?" queried an old fellow, who had come up with the little crowd, from his shack down by the ferry.

The sheriff, every tone vibrant with contempt, read the note aloud.

The old man combed his beard thoughtfully: he had known Lee Allan long, and had liked him. "Better not tackle it alone, Bob," he said uneasily. "He'll git yuh, sure as you're born; and he'll do just what he says, too."

"Would you take a dare like that?" demanded the sheriff angrily. "Anyway, what am I sheriff for?"

"Yuh ain't sheriff to commit suicide," said the old man calmly. "I voted for yuh. Bob, and I hate to sec yuh tackle the job single-handed. Lee's desp'rate. He used to be as white a boy as you'll find—but he's got a price on his head; that'll change most anybody's temper, I reckon. Don't yuh go alone, Bob."

Farrow laughed shortly, read the note slowly through once more, and put it carefully away inside his memorandum-book. "I'll go play tag with him all right," he said grimly, "and I won't come back alone—I promise yuh that."

He mounted his horse and rode back to the ferry, meditating the insult and how he should avenge it. As the ferry swung out from shore, the old man stood on the edge of the bank, combing his rusty-red heard with his fingers and shaking his head ominously; the sheriff, looking at him, laughed.

"Yuh mustn't be too blame sure about Lee Allan winning out, old-timer," he shouted, a bit boastfully, and turned to discuss the hold-up with his friends.

Many warned him, and many begged to be taken along. But for every fresh applicant his refusal was tinged with a deeper annoyance. Why should they be so sure of his failure? It was man against man, both well armed and able to hit what they shot at. He could not sec where Allan would have any particular advantage, except that he was familiar with the battle-ground. On the other hand, he had given his promise not to shoot the sheriff—which he would doubtless regret. Farrow smiled to himself; he had not handicapped himself by a promise of any sort; he would certainly shoot on sight.

He went about his preparations calmly in the face of much-unheeded advice and remonstrance. To the men of Col-ton, the fact that any man was determined to go out alone to capture Lee Allan seemed proof that his mind was not right. They called him a fool privately, and wished him luck publicly, and let it go at that.

Next morning at sunrise the sheriff jogged down to the ferry, with a well-laden pack-pony ambling at the heels of his horse, and with a smile for the melancholy farewells of the early risers whom he met. The old man came out of his little shack on the far river-bank, and looked after him bodefully.

"See yuh later!" called the sheriff cheerfully, and laughed at the general air of gloom with which his levity was silently reproved.

Farrow looked back at the little town, sent a mute good-by to a certain girl who had cried, the night before, with her face hidden on his shoulder, and faced calmly the south.. He did not ride as though moments were very precious, for he was of the sort who can hold impatience in leash and hasten slowly. He had a "grub-stake" that would last him two weeks—longer, if he were put to the necessity—and ammunition a-plenty. With the town and the river behind him, his eye went appraisingly over his outfit and spoke satisfaction.

He settled into his saddle contentedly and slipped the reins between his fingers while he made a cigarette. Then he faced the rim of yellow-brown hills and went on with the leisurely dogtrot that carries a man far, between sun and sun, and does not fag his horse. And while he rode, that last, jeering line of the note chanted over and over in his brain, and fitted its taunting measure to the hoof-beats of his horse: "You'll come a-running—I don't think! You'll come a-running—I don't think!"—till the words whipped his resentment into a cold rage that held no place for mercy.

At dusk he camped in the very edge of the Bad-lands, and knew that the game began on the morrow, and that it was to be played out to the end—which was death, if he lost. For the other, death or shackles, as fate might determine. But Bob was not afraid of the outcome. Mis dreams had nothing to do with outlaws and their haunts; they were all about the girl who had cried upon his shoulder.

When he swung again into the saddle the sun was gilding all the hilltops, and the hollows were gloomy and chill with the night that had gone before. He felt, for the first time keenly, the magnitude of the task he had set himself. Somewhere in that bleak, barren jumble before him Lee Allan lurked and waited his coming; but where? The stony hillsides gave-no trace to follow; it must be an aimless quest, with the finding left to chance.

He rode warily, choosing instinctively the easiest path and watching like an Indian for sign of life among those silent pinnacles: stopping often to examine with field-glasses some far-off object that looked suspicious, and that turned out nothing more than blackened rock, grotesquely human in form.

At noon-something whined past him and spatted against a rock ten feet in front of his horse. He pulled up sharply and listened; the far-off crack of a rifle echoed mockingly among the rocks.

He turned and eyed the gaunt hills behind, but they held their secret in grim, unsmiling silence.

He swore aloud, got off his horse, and went and examined the rock that had been hit. He picked up a bit of flattened, steel-jacketed lead, and slipped it into his pocket. Then he looked again behind, searching with the glass, studied the sheer walls of the bluff, mounted his horse, and went imperturbably on. The game, he told himself, had begun.

Just at sundown another bullet sang plaintively and flicked up the yellow dust in the cow-trail he was following. He got off and hunted for it; found it, and put it with the other—and his fingers trembled slightly.

"I'll give him bullet for bullet—the cur!" he comforted himself.

He did not try very hard to discover the source of the shot. The outlaw was evidently using smokeless powder, and there were more than a thousand places within long range that might be his hiding-place. The rifle-crack told nothing, for the hills caught up the sound and distorted it with their echoes, as if they were in league with the outlaw and took pleasure in throwing the sheriff off the scent.

That night he sat with his back against a rock wall, with his rifle across his knees, and with his eyes wide open and his ears strained to catch the slightest sound—of sliding gravel, or the click of boot-heel upon rock. The stars rested their toes upon the jagged pinnacles and blinked down at the lonely, black hollows that lay sleeping beneath.

All night he sat there watching, and at day-dawn boiled his coffee, fried his bacon, and ate his breakfast moodily. After that he packed and saddled, and went on—heavy-eyed and savage with the world.

Half a mile, and a third bullet spatted significantly against a boulder ten feet from the trail. Unconsciously he noticed that the bullets always struck approximately ten feet from him; even in missing him, Lee Allan showed accurate marksmanship. With teeth grinding he got down and went after the bullet. A bit of paper, held in place upon the boulder by a stone, fluttered as if eager to claim his attention. He jerked it viciously loose, and read the laconic message:

Tag! You're IT.

He shook his fist impotently at the sullen, gray crags, and shouted curses that the rocks gave defiantly back to him, word for word. When he had calmed he went on doggedly.

When the rock-shadows were but narrow frills of shade, came another leaden reminder that he was watched, and he knew now the song it sang: "Tag! You're it!"

He searched for the bullet anxiously, feeling Lee Allan's scornful dark eyes following his every move. When he had found the bullet and dropped it with the others, he ate his lunch feverishly and went on, doubling, turning unexpectedly north and south and west, as he found opportunity, hoping to fool his enemy and throw him off the scent.

When the sun was setting redly came the fifth singing messenger ten feet before him. That night he sat as he had done the night before, with his back to a rock and the rifle across his knees, arid waited and watched, and strained his cars for faint sound in the chill, brooding silence of the wilderness. S That night there were no stars to keep watch with him; a cold wind crept down the rock-strewn gulches and chilled him as he sat, but he did not 'move; he did not dare. He only listened the harder, and peered into the black with eyes that ached with sleep-hunger, and waited for the dawn.

Late that afternoon, when the bullets he had gathered numbered seven and when the strain Upon nervous and physical endurance was too great longer to be borne, he fancied that there was movement among the huddle of black, scarred boulders across the narrow gulch. He raised his rifle and fired his first-shot. Half a minute, perhaps, he watched, dull-eyed and haggard, the place.

"If I killed him," he muttered aloud, "I could sleep."

It had come to that, then; he must sleep. Killing Lee Allan was, after all, but the clearing away of an obstacle to his sleep. He became unreasoning, malignant. His clouded brain, strained to the limit hi those two days and nights, had place for but one idea—to kill.

He fired wildly at every rock, every stunted sage-bush that his distorted imagination could construe into the semblance of a man. He emptied the magazine ol his gun, and refilled it feverishly; emptied it again, while the fantastic peaks and cliffs and hollows barked jeering reply. Save for the echoes there was no sound, and he laughed gloatingly.

A bullet—the eighth—hummed close to his ear and kicked the dust under the very nose of his horse. It threw back its head nervously, and Bob, forgetting where he was and the precarious path he followed, jerked the reins savagely and dug deep with his spurs.

They went down together, sliding and rolling to the bottom of the gulley. The horse struggled wildly, gained his feet, and stood with the saddle hanging upon one side, eying his master curiously. After a time he took a tentative step or two, shook himself disgustedly, and began nibbling the scanty grass-growth. Up on the trail, the pack-pony gazed into the gulley and whinnied lonesome.

When Bob opened his eyes, it was to see where all the water came from. His head and face were dripping, and the first conscious thought was met by another dash of water in his face.

"How the dickens did yuh fall over that bank?" a voice questioned plaintively. "Yuh wasn't shot—and neither was your horse." The last words were spoken defensively.

Bob raised to an elbow and stared grimly at the man. The cold water seemed to have cleared his brain. "Hell!" he said, and lay back again. There did not seem anything else to say.

"Yes, and then some!" assented the other petulantly. "Do yuh know your leg is broke?"

"No matter," said Bob laconically. "I can starve just as long with a broken—"

"You was a fool to come," complained Allan. "Yuh might 'a' knowed you'd got the worst uh the deal."

Farrow looked at him. "I'm Valley County's little tin sheriff," he reminded. "And that ten thousand would come handy to start housekeeping with." He was holding himself steady with an effort. When he stopped speaking, his lips twitched with pain and weakness.

Allan stood irresolute, looking down on him with close-drawn brows. "Who—is she?" It was as if the words spoke themselves, against his will.

Farrow opened his eyes and looked at him squarely, challengingly. "Her name's—Mabel Thomas," he said defiantly. "We was going to be married in six weeks."

He saw Allan wince, and closed his eyes satisfied; if he had to die, he had at least struck one blow home, he thought.

Allan sat clown on a rock and rolled a cigarette with unsteady fingers. "I suppose," he said slowly, "yuh think a lot of her." He lit a match, held it to the cigarette, and took three puffs. "And yuh think she—likes you," he finished deliberately.

"I know it!" flashed Bob, forgetting for the moment his hurts, anxious only to wound the other.

Allan said nothing—but his cigarette went out many times before he finally threw it away. Bob sank into a stupor born of his great weariness, his hurt, and his loss of sleep. He was roused by a great wrenching pain, and struggled wildly.

"Lay still!" commanded the voice of Allan. "I just had it in place."

"What—"

"I'm trying to set your leg—if yuh'd keep your nerve. Can't yuh stand nothing, yuh lobster?"

Farrow lay still and clenched his teeth; he did not like having even Allan think him a coward. When it was over he was weak and giddy, and felt only vaguely that he was being moved, and that the new place was softer and more comfortable. After that was blank.

He opened his eyes to the sun of another day, and his nostrils to the smell of frying bacon. He discovered that he was lying between his own blankets—and with memory came wonder. He raised painfully to an elbow and discovered Allan sitting upon a rock beside a camp-fire, rolling a cigarette while he kept an eye upon the bacon, frying in the sheriff's frying-pan. Instinctively he reached toward his hip. Allan caught the movement—being an outlaw must breed wariness in a man—and he frowned.

"Better lay down," he said evenly. "I didn't think yuh was such a sneak—but I didn't take no chances. Yuh ain't got any more gun than a jack-rabbit, old-timer."

"I'm not a sneak. We ain't what you might call chums, Lee Allan."

"Sure not—thank the Lord! But we aint fighting each other just at the present time, either. It's 'king's ex,' old-timer—till further notice."

Bob Farrow lay back and did some rapid thinking. He had never known Lee Allan, save by reputation. He could not fathom the mystery of his mercy; he felt dazed and uneasy, and he watched the outlaw covertly.

When the bacon was done they ate, not as comrades, but in stony silence. Allan did many things for the comfort of Bob, and refilled his coffee-cup twice, saying only: "Drink lots—yuh got a hard day ahead, with that game leg uh yours." At this Bob wondered more.

He watched Allan divide the pack, and tie a part behind the saddle of his horse—and thought it meant desertion in cold blood. He watched him bring a rude, newly made travail—such as Indians use to drag burdens—and fasten it to the pack-saddle on the pony; he did not quite know what to think of that; but leaned to the belief that Allan was a past master in refined cruelty, and meant to keep him with him, alive—for what purpose he could not guess. He made no protest, and fought to keep back the groans, when he was transferred to the travail, blankets and all.

The day dragged interminably to Farrow, though he dozed part of it away. The travail was not as excruciating a mode of travel as he had feared, though his leg hurt cruelly at times. The way seemed strange—he had no doubt they were penetrating farther into the 'wilderness; they wound through coulee-bottoms and narrow gulches, for the most part, on account of the travail, he could not help seeing that Allan was very careful, and made the trip as easy as possible.

That night, when they had eaten and the camp-fire of sage-brush was throwing fantastic lights and shadows upon them, his silence broke in a question.

"Allan, on the dead—what are you doing it for?"

"That's ray affair." said Allan shortly, and the conversation closed abruptly.

The next day, just after sundown, they stopped in the shelter of a hill that seemed familiar. Bob looked at it long, and studied deeply a new thought. Still, he did not say anything—then. He was weak and feverish, and he thought he might be mistaken.

Then Allan spoke quietly, in the undertone he most have learned in those two years of outlawry.

"It's pretty hard on yuh—but if yuh think you can stand it, we'll make a night move. It's that or lay over till to-morrow night—and yuh need care."

Bob caught his under lip sharply between his teeth to steady himself. Then: "I'm dead next to you now, partner," he said, a bit shakily. "You're taking me home. Don't yuh know the risk? If anybody gets sight of yuh—that ten thousand'll look like a gold-mine."

"I'm only going to take yuh as far as the ferry. I'll hold up that old red-whiskered rube and make him take care of yuh." Allan spoke roughly, but the roughness was not very deep, and Bob was not fooled. He stretched out a shaking hand and gripped the fingers of the other.

"You're a better man than I am," he said simply. "You're white. I didn't know yuh, or I wouldn't have come out here. You're—white—"

"No," Allan's tone was bitter. "I'm ten thousand dollars' worth of menace to the peace and dignity uh Montana! I'm a blot that the law'd be tickled to death to wipe off the earth. I ain't human. I'm just—an outlaw!" It was a cry for justice, and as such Bob read it.

"Look here," he began, after a silence. "You mustn't go any farther. I can manage alone. If you'll fix the bridle on the pony and let me have the reins, I can drive him. Or, anyway, he'll go straight home—straight to the ferry. He's dead gentle."

"Not on your life. I may be all that my reputation calls for—but I never quit a job till it's done. I started out to land you at the ferry."

Bob said no more for a time. Then: "I hate to have you ranging out in those God-forgotten hills; it ain't a fit life for a dog. I wish—"

"I'm through here," Allan confided simply. "I'm sick of plugging posses and raising particular hell by my high lonesome. I got that ten thousand to help me out. I'm going to drift, partner, soon as I see yuh at the ferry. I wanted to get yuh down here and have some fun with yuh, was why I wrote that note. That—that starving business was just a bluff; I wouldn't do that to a coyote. It was a josh. I knew yuh couldn't get me in a thousand years—but I knew I could deal you misery, and never touch you."

"You sure succeeded," Bob answered dryly, thinking of those sleepless nights and nightmare days.

"I can savvy a trick like that," he went on, after a minute. "You had a cinch, and you knew it. But what gets me is why you're doing this."

A flame leaped up from the fire and lighted Allan's face; his dark eyes glowed in the glare, then he moved back into the shadow. He got up and looked away toward the horses.

"We'd better be drifting, if we want to get to the ferry before daylight," he said.

He walked a few steps from the fire, stopped, then turned and came back. He stood a minute without speaking.

"You—said—she cared a lot," he said.

He went hurriedly back and brought up the horses, and lifted the travois-ends gently, so as not to hurt Farrow.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.