RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

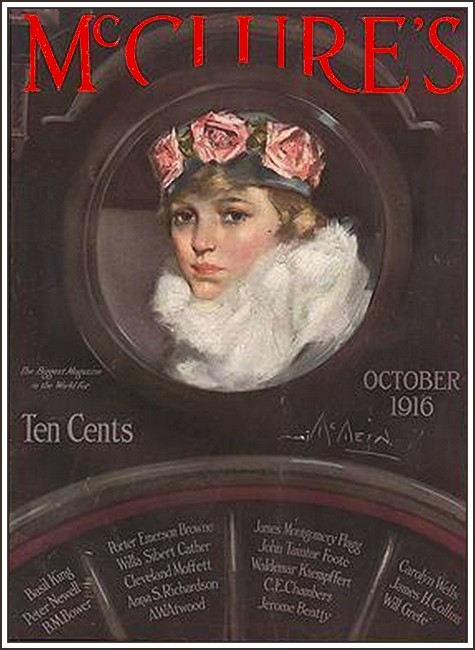

McClure's Magazine, October 1916, with "The Gun Runners"

THE Kid, riding up from the border one day when the sun was slanting well toward the West, glanced at Charlie Horne three different times, each time believing that Charlie was perfectly unconscious of the glance. The Kid had for an hour been so restless you would have thought the saddle he rode was hot, he shifted his position so often. He kept twisting his neck and looking behind him, and eying Charlie until at last speech that he meant as a concealment of his thoughts overcame his prudence.

"Say, I believe I'll take the trail around Granite Peak, Charlie; I—I seen something that looked kinda promisin', and I believe I'll go take another look."

Little Charlie Horne quirked his lips and waved his hand in generous acquiescence.

"Sure,Kid. You go to it. But listen: don't you be long, 'cause it's getting late, and it takes time to get into our hangout without leaving a trail others could follow."

"All right, I won't be long." The Kid made hasty promise, and straightway bore away toward the main trail from Dry Devils to Cobra, riding as if in a hurry. Charlie pulled up and thoughtfully watched him out of sight. This was the third time that the Kid had left him for a flimsy excuse, and had ridden off in the general direction of Dry Devils. Charlie did not understand why the Kid should be so secretive all at once—he who usually bubbled with speech upon any new adventure or clue.

When the Kid's bobbing hat-crown disappeared finally among the ridges, Charlie rode on slowly, keeping a close watch on all sides for some sign of the men they two were hunting—men who were breaking the law in various ways, the chief one being smuggling guns and ammunition into Mexico.

He knew they were doing it, and he knew they were using the wild country on the eastern edge of the Big Bend country for their work. The river guard knew it, too, and had told Charlie all that he had seen or surmised—the latter being much more extensive and much less important than what had been seen. Charlie and the Kid knew, too, that cattle had been stolen and run across the line within the past two weeks. A rancher named Dallam had lost a good many, and had strongly hinted that the rangers ought to do something about it.

What worried Charlie Horne just now was the fact that with all their riding and spying and trailing, they could not even guess at the identity of the men they were after, nor could they discover the method used to ship the forbidden goods across the line. They had done it somehow, Charlie knew. From a high pinnacle that overlooked a large stretch of the low land lying south of the Rio Grande (which was the Mexican boundary) he had seen, in the adobe-walled courtyard of a Mexican rancho, much activity among the peons and their masters. He had seen a burro train loaded and headed south. He knew the loads had been rifles—the glint of sun on steel had betrayed that much, though he had seen it only once or twice when a rifle had been turned so that a lever left unblued had reflected the sunlight.

But this had been six miles or so inside Mexico, and Charlie had no right to carry his investigations across the river—except as a pair of powerful glasses might bridge the distance for his eyes.

What he hoped to do was to catch the men who sent the guns over there. That was what he and Van Dillon and Bill Gillis had been sent down there to do, and what, so far, they had failed to do. It was not a pleasant thought, when Charlie looked back upon the long days they had spent riding these hills, skirting arroyos, lying in the shade of rocks with field glasses at their eyes and guns ready to their hands.

He had seen guns across the line, being hurried to their ultimate destination, and he had felt cheered a little by the actual evidence of gun-running. But that was two days ago and he had not discovered anything at all that would indicate that any gun-runners existed on his side the river.

It did not cheer Charlie Horne to feel that the Kid had been of very little help to him in the search. The Kid's mind was alert enough, and his youthful enthusiasm and bland assurance had more than once made up for his lack of discipline and experience. But when he took to mooning along the trail so absorbed in his own thoughts that Charlie, riding beside him, had to speak twice to gain his attention, he was not likely to see a clue if he fell over it. And when he took to slipping away from Charlie and riding off by himself without an excuse worthy the name, Charlie felt that he was worse than alone on the case.

Charlie did not believe there was anything to be learned by riding around past Granite Peak. Granite Peak was merely an arid, egg-shaped hill of granite planted squarely on the southern boundary of the settlement. At the blunt nose of the peak squatted a schoolhouse with its white-fenced, hard-packed yard and its flagpole and its staring windows all in a row. At the hill's other end squatted the little adobe village of Cobra—squalid and peopled with unwashed citizens who lounged along the dirty alleys when they were not sitting somewhere half asleep in the shade with cigarettes dangling from their loose lips and their overalled knees drawn up and clasped by their grimy hands. Connecting schoolhouse and village was a two-mile stretch of dusty wagon road, cut across in one place by the railroad that avoided Granite Peak as long as possible and finally was forced by other hills to snip out a few deep cuts for its roadbed near the Cobra end. On the other side of the hill lay the big hay and cattle ranch of Dallam and his sons.

Dusk came before the Kid arrived at the little, hidden cabin which had been the secret home of an outlaw but was now headquarters for the three rangers on duty at Cobra. He came in smiling fatuously to himself, and when Charlie asked him if he had stopped at the post-office for the mail the Kid replied absently that he forgot it. When he started to pour coffee into his plate instead of the tin cup alongside, Charlie felt that the time had come to speak upon a subject he would by choice have avoided.

"See that promising sight again, around Granite Peak, Van?" he began, helping himself to the beans.

"I dunno," the Kid replied absently, a vacant look in his eyes.

Charlie cleared his throat. It was going to be unpleasant, but he needed the Kid's help; besides, Bill Gillis would expect him to keep Van out of any foolishness while they two were there alone. "You didn't meet up with the school-ma'am, I suppose," he hinted, watching the Kid's face.

Van shot him a resentful glance and said nothing.

"Because," Charlie went on, "if you did I hope you didn't forget your business on account of meeting her. We've got to clean up this gun-running before Bill gets back, Kid, or we'll feel like thirty cents. We haven't got time to fool around with girls "

"Who said I been fooling around with any girls?" Van demanded crossly. "I guess I've pretty near held up my end of the work since we've been here. You kinda forget who it was that nabbed them opium smugglers, don't you? You ain't got any license to go throwing it into me about shirking my share of the work. You and Bill make me tired when you start preaching."

Charlie's cheek-bones showed the hot flush of anger, but he held his voice quiet. A heady youth was Van, impatient of criticism, afflicted with an exaggerated sense of his own manliness. But he was brave and true and generous-souled—just coltish, Charlie reminded himself before he spoke again.

"Well, you see, we get pretty tired ourselves before we start to preach. We've had these spasms of liking to be with girls, ourselves, and we know how they can play hob with a fellow's work. When we try to keep you from going wrong, Kid, we ain't doing it just to be bossing somebody, or—"

"I don't care what you do it for—it don't set well." The Kid had all the intolerance of a nineteen-year-old youth who is taking a man's place in the game of life.

"All right, if that's the way you look at it. I'm just trying to save you a jolt, Kid. Margy Wheeler is engaged to Fred Dallam. She ain't taking you seriously—she just likes to fool around with you when Fred ain't on hand to amuse her."

"That's my business," Van retorted rudely.

"Oh, I thought your business was to help land these gun-runners."

"How do you know she's engaged to Fred Dallam?" Van's anxiety betrayed him into asking. "I don't believe it, anyway. He ain't the kind a girl like her would get engaged to. Who told you?"

"You say that's your business, Kid, so I'm done talking." Charlie got up and went outside, because he did not want to quarrel with Van, and there is a limit to what a man may endure in the way of impudence from a boy.

When he returned to the cabin, half an hour later. Van had the dishes washed and the floor swept, and was coaxing a cheery blaze from the smoldering brands in the fireplace. He looked up at Charlie and grinned shamefacedly, but he did not say anything, and presently Charlie went to bed and lay with the blanket pulled up to his ears and face turned to the wall. He wanted to think, and in this tiny cabin he took the only means at hand of being left undisturbed while the Kid was yet awake. But the Kid had persistence.

"Who told you Margery Wheeler's engaged?" he asked abruptly, his round blue eyes fixed upon the top of Charlie's head.

When Charlie did not reply. Van got up and stood by the bed, hands in pockets and face as long as its contour would permit. "You needn't go and git mad at me," he complained. "I'm doing all I can to git a line on them gun-runners. I'm doing as much as anybody's doing. What you want me to do, for gosh sake? Kill my horse riding him up 'n' down the river day and night? It's all mud and quicksand anyway, except at Obayas and the ford where the river guard stays. They git 'em across at one of them two places unless they use boats or else they don't run 'em from Cobra at all. I've got that much figured out, even if I don't know anything.

"Why don't the river guard git busy? What's he paid for? All I ever seen him do is to set on his horse and swap lies with Dallam's hay-haulers when they go across. You talk like it was all my fault that the whole country ain't under arrest. I can't ride outa your sight, by gosh, but you think I'm laying down on the job! You and Bill think, by gosh, that because I ain't gray-headed you've got to watch me and boss me around and preach to me or I'll make some fool break. You think I don't know anything. I've humored you fellows along and let you boss me, and you think, by gosh, that because I stand for it I like it! I'm just a Kid! I can't be trusted. I got to be tied to your coat tail or you think, by gosh—"

"Say," Charlie interrupted in a purposely weary tone, "change the needle and put on another record. I'm tired of that What-a-Brave-Boy-Am-I-By-Gosh."

The Kid choked, spluttered incoherently in his rage and went to bed, his egotism hurt much worse than if Charlie Lad come up fighting. Charlie had declined to take him seriously—and to be taken seriously is what a nineteen-year-old young man hungers for most.

BREAKFAST was eaten in silence. Charlie was still pondering the problem of the gun-runners, trying to guess at their probable method and identity. The Kid was still worried over the possible engagement of Margy Wheeler and wishing he knew where Charlie had gotten his information. The best way the Kid knew of finding out, since Charlie refused to tell him, was to ask Margy herself. And today was Saturday, and Margy would be free to ride wherever she pleased; somewhere south of Granite Peak, the Kid hoped. And since he and Charlie were riding "blind" anyway, there was as much chance of picking up some clue when he was with Margy as when he was alone or with Charlie.

Charlie Horne saddled and rode away without a word to Van about his plans, and let the Kid follow his own devices. He had intended to ride down to the river and search its bank for some trace of a boat landing, or some evidence of a blind trail leading into the hills. Also he had expected the Kid to mount and come with him without being told. But when he had negotiated the first hard scramble up a rocky gorge that led into a more open canon, and had stopped to breathe his horse and wait for Van, there was neither sight nor sound of that self-sufficient youth. Charlie sat there on his horse and waited while he rolled and lighted a cigarette. Then he gave a grunt and bore off to the east instead of the south. To the east he could make his way by various short-cuts to the end of Granite Peak where the Del Rio road passed the schoolhouse and wound down through the sand hills. If Van went the other way, past Cobra, Charlie would be ahead of him, and he could swing down to the river from there and have a word with the river guard. But his main object, just then, was to find out for himself what Van Dillon was up to. For that reason he rode circumspectly, keeping always out of sight in dry washes and little gullies that laced the hills together.

He came out upon the road to the river and waited behind a little ridge while Dallam's hay-haulers passed, delivering baled hay across the ford to the Mexican freighters that took it on down to feed the cavalry horses.

When the four heavily-loaded wagons chuckled past, the horses kicking up a cloud of dust and the drivers gossiping cheerfully at the tops of their voices, Charlie took the trail and loped toward the schoolhouse, where he suspected that the Kid would presently appear. A quarter of a mile or so he rode, and then ducked behind another convenient ridge because, just around the bend, he heard voices, in which a girl's laugh was mingled. Margy Wheeler and the Kid, he told himself grimly, and waited, wondering the while how Van had managed to get here so soon.

Presently the two riders came slowly into sight (Charlie was off his horse by now, and was lying flat on his stomach behind a mesquite bush where he could look down upon the trail). Margy Wheeler it was—but the young man riding beside her was not the Kid.

"I expect he'll be coming along pretty soon," Margy Wheeler was saying. "I told him I thought maybe I'd go to Mineral Spring today—"

"Well, keep him at Mineral Spring—if you have to tie him!" the young man urged unsmilingly. "We'll know where he is then. We can't have him running around loose, and maybe come riding into the ranch just when—"

They passed, and Charlie craned his neck after them. Just when—what? He ran down to his horse, mounted and skirted the road carefully, trying to come again within hearing of the two; but before he had come up with them he saw the man, Fred Dallam, riding back alone in the direction of the ranch. Charlie was tempted to follow him; but since he had started out to discover what part the Kid was playing that day, he kept after the girl.

She came to the fork in the road where a branch led to the river and another turned down along Granite Peak toward Cobra, and pulled up there as though she were waiting for someone. On the river branch the dust was settling slowly behind the hay-haulers; the faint chuckle of the wagons rolling, rolling down a rocky slope came to Charlie's ears as he pulled up to see what Margy Wheeler was going to do next.

For ten minutes she did not do anything at all except amuse herself by separating her rein-ends and snapping them together with a pop that always made her pony jerk his head up and look around at her protestingly. Now and then she glanced expectantly down the trail toward Cobra and once she looked at her watch impatiently.

A cloud of dust rolled up along the Cobra trail. The girl stopped teasing her pony and stared down that way intently, and Charlie wormed in between two bushes that stood within ten feet of the trail. If it were Van coming, the more Charlie could see and hear the better for both them.

Van it was, galloping eagerly to meet Margy Wheeler. He slowed up when he neared her and his round, boyish face glowed with the pleasure there was for him in the meeting. Charlie, peering between the branches, felt an angry sympathy for the Kid.

Margy Wheeler made no pretense of being surprised there in the trail. She had an engaging frankness of manner that would have won the implicit faith of an older man than Van Dillon; Charlie had to admit that he did not blame the Kid so much.

"I was hanging around hoping you'd show up," was the way Margy began. "I'm going over to Mineral Spring, and I've got lunch for a dozen—Auntie Dallam is so terribly generous. Ham sandwiches that thick!" She spread her two gloved hands in exaggerated measurement' and laughed again and little Charlie Horne hated her because she had two dimples and a twinkle that was maddening.

"I sure wish I could go along," the Kid said longingly. "But I've got to ride down to the river. I just came around this way—"

"Ah-h—pul-lease!" (Charlie could have shaken her for tempting the Kid so with her confounded dimples.) "The river won't run away."

"I dunno—it was running pretty fast yesterday. I'll have to go some to keep up with it." The Kid's innocent blue eyes worshiped her humbly; but behind the worship a shamed doubt peered forth—the doubt which Charlie had deliberately planted in his mind. "Why can't Fred Dallam go with you?" he asked bluntly, boy-like.

"Fred Dallam" She of the dimples managed to inject a good deal of surprise, a little amusement and much reproach into the words. "Why, Van! Do you—would you rather he went?"

"Well, if you're engaged to him, I would." The Kid was eying her steadily, trying to read her mind. When she only looked at him and said nothing, he added: "Nobody likes to be made a fool of." Then, as she still said nothing but only smiled teasingly, he wet his lips and asked the question that had come to mean so much to him. "Are you, Margy?"

"Are I what?" She was teasing him just as she had teased her pony.

"Are you engaged to Fred Dallam?" The Kid, as has been explained before, had persistence.

Margy wrinkled her nose at him. "A person would think you hoped so," she parried. "I'm not going to answer such silly questions. Fred Dallam!" Again she managed to inject a good deal of meaning into her tone. "You come along with me or I'll think you want me to be engaged to Fred Dallam."

"Well, are you engaged to him?"

Charlie came near laughing aloud at the Kid's unshakable determination to have his answer. It was that doggedness that bade fair to make a splendid ranger of Van Dillon, but it was not a quality that appealed to Margy Wheeler in the least. Her very real exasperation tickled Charlie Horne, knowing how much she wanted the Kid to go with her—and why!

"For pity's sake, Van Dillon! How many times must I tell you—"

"Just once," Van cut in stubbornly. "You ain't told me once yet."

"You come along with me and don't be silly."

"Well, are you?" asked the Kid again, and little Charlie Horne clapped his hand over his mouth and dug his boot-toes into the sand to keep from shouting in his glee. But last night the Kid's persistence had not pleased him so much.

Evidently the young woman had very strict ideas upon the subject of lying point-blank.

"Catch me and maybe I'll tell you!" she cried suddenly, wheeling her pony and striking him sharply with her quirt.

This was a new move, and it took the Kid by surprise. She was fifty yards away before he started after her, and he yelled to her to look out or that pony would stub his toe and fall down. She kept on, however, looking back and laughing at the Kid who was sure to catch her before she had gone far and who might forget, in the zest of the chase, to ask again the question she dreaded to answer.

CHARLIE HORNE backed out of the bush and squatted on his boot-heels, watching the two until they were hidden in the cloud of dust they kicked out of the trail. Of course the girl would have her way and take the Kid to Mineral Spring—she was shrewd enough to run in that direction now, and judging from what Charlie had seen and heard, he thought she would manage to keep him there. He stood up and watched the dust cloud roll on down the trail and then turned his attention to his own affairs. The Kid had fallen into the trap—whatever it was. Margy Wheeler would keep him away from the ranch

Why? What was the sudden objection to having Van Dillon ride home with the girl? Why didn't Fred Dallam want him in the neighborhood that day?

Granite Peak, as we have explained, was merely a huge, egg-shaped mound of granite, barren as rock can be; jagged and forbidding like most of the volcanic upheavals in the Southwest. Charlie mounted and rode close to the southern wall where the broken slope promised a fair foothold; cached his horse in a brushy hollow, hung his spurs over the saddle-horn, took his carbine from its boot and began to climb.

At the top he sank down breathless and perspiring in a sheltered nook where he would not be seen from below. The little uneven valley to the north lay spread before him, Dallam's ranch in the foreground, five hundred feet below. He took his field glasses from their case, adjusted the focus and began a slow, critical survey of the ranch from the stables and corrals to the farthest pasture fence.

A little world in itself it looked, absorbed in its own peaceful pursuits. Besides the adobe ranch house with its vine-covered porch and high, white-curtained windows, a bareheaded woman was kneeling, prodding with an old fork at the roots of some plants that looked like "bachelor buttons" just coming into quaint bloom. A yellow hen squeezed through a wide space in the paling fence and came toward her, stopping now and then with one foot uplifted, to watch the woman with perky, sidelong glances. The woman rose stiffly, spied the hen and flapped her apron at it, and the hen went fluttering here and there, trying to find the place where it came through the fence.

He turned the glasses upon the corrals and saw four calves lying asleep under a shed, at peace with their world. A few pigs rooted boredly outside. Along the trail beyond the buildings where the road was fenced into a lane, a man was jogging townward in a spring wagon drawn by a pair of high-hipped work horses. Nothing, absolutely nothing to excite curiosity or suspicion.

Immediately below him, too close to the hill for him to see unless he moved his position, voices rose in desultory talk. The rattle and clank of a hay-baler told that work was going on; pressing the harvest of the broad meadowland into bales of fragrant hay that brought better prices from the Mexicans than it did in the Texas market. Charlie knew all about that. He had frequently talked with the haulers, easygoing fellows with twinkling eyes and a joke always on the tips of their tongues; old-time range riders whom age or accident had shelved to the high spring-seat of a hay wagon to drive four or six, as the load might warrant, down to the ford and a mile or so beyond; chewing and shouting back and forth and giving no thought of the morrow—Charlie knew them, every one. And right down here below him was the baling crew that kept the haulers supplied with wired, hard-packed squares of secate—which is the Mexican word for hay. For the life of him, Charlie could not see why Fred Dallam should be so anxious to ensure the Kid's absence from the ranch that day. So far as he could see there was nothing unusual going on—and he had to admit to himself that when he climbed the peak he had expected to see something besides every-day ranch work going on at Dallam's.

But Charlie Horne was a thorough young man, and since he had exerted himself to climb Granite Peak he would not go down without having seen all there was to be seen. He let himself down into a fissure from where he could see the baling crew at work.

INSIDE a large corral of adobe that had for one side of it the bare, seamed side of the bluff, stood the press beside a long stack of hay. From the fissure Charlie could look down on the men, and into the baler itself. He settled himself with his back against wall of the fissure and his feet braced against the opposite side and proceeded to watch the process of baling hay. It looked simple enough to Charlie, up there in the shade and more or less at his ease. A Mexican crew this was, and for greasers Charlie considered that they showed a great deal of industry—especially since they were working without a boss. Fred Dallam probably had charge of the work, but it was plain that he could safely leave them without much fear of their shirking.

Whatever questionable business might take place at the Dallam ranch, Charlie had no clue to it. Just now it was very quiet, very peaceful. Now and then a laugh arose, or a snatch of song. Charlie began to feel that his climb had been labor wasted.

Then, idly watching the hay press at work, he leaned forward and stared down into the corral. One bale, two bales—a good half-dozen were pressed and tied with wire and dragged to the pile where the haulers loaded their wagons, before Charlie moved any part of him but his eyelids. "Well, what do you know about that!" he muttered at last, with a little, satisfied smile twitching at the corners of his lips. He leaned forward and watched another bale come out of the press, and then began a cautious retreat from his hiding place.

He reached his horse, mounted and rode down the side toward Cobra, rounded the end of the peak nearest the town, hid his horse in another clump of bushes and began to make his way back toward the corral, keeping under cover of rocks and bushes, and taking advantage of every little gully and every dry wash.

The hay-baler was still at work, the voices of the men still chattered good-naturedly above the clank of the press. Charlie stood close to the corral wall where it joined the bluff and listened for a minute, searched with his eyes for foothold above him, and with his carbine held in his right hand he climbed up and over.

By the positions of the men at their work he knew none of them would be facing this way—he had made sure of that while he was up on the peak—so that he had not much fear of being seen too soon. Still it was a ticklish moment for him while he was pulling himself to the top of the wall and getting his legs over, ready to jump down inside. But he had the haystack between himself and the crew as soon as he was on the ground inside, and the man on the stack had been looking down on the other way at the baler, and had not seen him. No one saw him, in fact, until he stepped around the end of the haystack with his rifle looking their way menacingly.

"PUT up your hands, boys," he said, by way of announcing his presence, and grinned at the way their jaws dropped when they whirled and faced him. "I'm a State Ranger."

His eyes went coldly over the group, and wherever they rested for a second or two, there a man turned a shade more sallow and lifted his trembling hands higher. The last to feel the weight of his glance was the man who had been tying the bales with wire. Charlie looked at him so hard the fellow's knees bent under him. Texas Ranger—only too well they knew what that meant.

"You wire and tie these men," Charlie commanded sharply. "Turn around, the rest of you, and back up here. Farther—over this way. Stop there. You next the baler, take down your hands and put them behind you. You with the wire, see if you can do as well as you done on the hay—Never mind the long ends—take a turn or two around his middle and give it a tie.... That's right—fine; now the next one, same way. Good.... Number five, put yours behind you. Put—your—hands—behind you! ... I thought you would. Tie him, you—here, give that wire an extra twist.... That's the way.

"Now, you with the wire, take a piece of it and back up here to me...."

"Oh, seņor, please—"

"Would you rather get shot? I thought not! Put your hands back here. All right—fine and dandy. Stand still, all of you—the show ain't quite over yet."

He shifted his rifle to the hollow of his arm and went down the line behind them, gleaning what weapons they had. Then he took a length of baling wire and wired them all together, a loop around the neck, a twist or two that held it like a collar; a foot of space and a loop around another neck with a couple of twists. Six in a row, one behind the other—and when he had finished, little Charlie Horne backed off and surveyed his work with a grin of approval.

"I sure ought to take out a patent on that neck-yokin' with wire," he told them quizzically. "Don't hurt yuh, does it?"

"No, seņor," quavered the hindmost one who, being farthest from the dreaded Texano, found courage to use his voice. "Still, if out on the collar of the shirt...."

"Why, sure!" Charlie went down the line, pulling sweaty shirt collars up to protect grimy necks from chafing with the wire. He had no desire to be more cruel than he must, and he told them so good-humoredly.

He was fumbling with the collar of the man in front when something—it may have been a flickering, a sidelong glance of the fellow's eyes—warned Charlie. He wheeled suddenly and faced the gate, his hand dropping to his gun, and saw Fred Dallam standing there. At the same instant Fred fired, and the bullet pinged past his face, it was so close. Charlie fired from the hip before Fred had time to aim again, and his shot went true. Fred dropped his gun and wobbled a minute before he sagged to the ground, one hand going up to his shoulder.

The six Mexicans exclaimed under their breaths, naming a saint or two supplicatingly. After that they stood very, very still, lest this terrible little man turn upon them in anger. Charlie went over to the fallen man, lifted him and, grunting with the weight, dragged him into the shade of the wall. He carried loose hay and strewed it hurriedly for a bed, got him upon it and raised his head upon an improvised pillow.

"That's all I can do for you right now, hombre" he said regretfully. "You ain't hurt as bad as you might be, at that. I can tell by your color, which is healthy, considering. I'll have to tie you up—but I'll be back with a doctor just as quick as I can make the trip to town and back."

Whereupon he marshaled his six yoked Mexicans and drove them before him at a trot toward Cobra. By a short cut it was not more than a mile—and such was his driving ability that he had them panting up the street to the jail in no more than half an hour or so. In another ten minutes he had found the doctor and started back with him.

"Hey, where yuh goin'?" shouted a voice from out a cloud of dust just where the road forked outside the town. "I'd like a little help with these here fellers, Charlie. I've been herdin' 'em along alone—and it ain't any snap!" The Kid, his round face purple with heat and excitement, rode out from behind a string of four-horse wagons and stared after the doctor's machine.

"Go on, doc. I'll be with yuh soon as I can," yelled Charlie, and jumped. He landed like a cat, on his feet; ran a rod before he could stop himself and returned to the Kid, who was marching three men ahead of him, while a fourth one, looking scared to death, drove the head wagon. The hay-haulers, Charlie saw when he gave them a second glance.

"What d' yuh think, Charlie?" the Kid began excitedly, "I found out how the guns was gittin' acrost! I was riding along behind the last hay wagon and a bale bounded off the top of the load and busted wide open—and say! There was four guns in the middle of the bale!"

"Uh-huh," Charlie grunted. "I saw how the baling crew was packing rifles in the middle of every bale—had their press-board fixed to leave the center hollow, so they could stick in the rifles and press a full flake on top—you know carbines is just the right size. I just now throwed 'em in jail. How'd you turn the trick, Kid?"

"Me?" The Kid pursed up his lips, his round eyes fixed upon his prisoners. Why, I just made 'em git off and walk—I took away their guns and made 'em hitch the leaders of every team to the wagon in front till they was all strung out like this—and then I took the scaredest one and made him drive the hull outfit in. And just to keep him thinkin' about me, I sent a bullet over his head once in a while."

THAT night, when the two could sit down once more for a comfortable smoke and talk the thing over, the Kid looked at Charlie queerly for a minute.

"Say," he began in a boyish, off-hand way to hide his deeper feelings, "I don't give a darn whether she's engaged to Fred Dallam or not. Serves her right if she is! She lied to me. She ain't the kinda girl I thought she was."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.