RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

THE crack and grumble of the band had blared into silence, for it was very late, and the circus in the main tent was over. A few cowboys and bar tenders still lingered talking to the officials of the show; but men were going about with battered brass extinguishers on the end of long thin poles, painted red and white—like barbers' poles—extinguishing the kerosene lamps, which hung from the copper brailing-pins above.

In the menagerie tent, a huge erection of brown Pulamite sack-canvas which opened out of the central building, stood the forge, with its glowing braziers and litter of pincers, the red light playing upon the long aluminium hammers that American circus smiths use. Round about the warmth, although it was very hot, stood several of the staff, drinking rye whisky from a bottle which stood upon the fore-peak of an anvil. The tent resounded with savage vibrations from the lion-cages. The fretting of mangy wolves and jackals, restless in the pain of their captivity, mingled with the trumpet-rumble of the elephants who stood among the straw at the end of the place. Their brown figures rocked to and fro unceasingly.

Close to the group of men, a brown bear, with little pig-like eyes, paced regularly round its small and dirty cage, and the soft sound of its pads could be distinctly heard amid all the tumult of the prisoners, who year by year yelped away their miserable lives.

THE travelling circus and show of George Zachary, who in his day had been a 'bruiser' of repute, held first place in the western states of America. Zachary himself, a ponderous, evil-minded old fellow, was still popular with all the rascaldom of the West, from Seattle City to the Golden Gate. His circus and menagerie, with its magnificent animals, its clever riders and beast-tamers, its unrivalled collection of living travesties of the human form, was the great annual pleasure of half a hundred boom cities. His performers were known by name to every one; his own personality, as he drove about in his buggy, with its silver-plated wheels, was herald of greater joys than the advent of a rich candidate for the State Legislature, and many a young rancher in these maidless wilds felt his heart expand with excitement when he thought of the pretty circus girls who followed in the great Zachary's train.

The show had just arrived in Heron, a large agricultural centre, not far from Spanish Peaks. For three days the cumbrous wagons and caravans had poured into the town, and disappeared inside the high enclosure of brarah-wood which had been built for them. Three days before, the watchers had caught the first sight of the elephants coming far away through the plains of roil grass. An army of rough saddle-coloured men had been busy building the central rotunda, and painting it in great streaks of white and crimson, which shrivelled and blistered in the fierce sun. All the next day the anxious people of the town had seen the huge tents rise up above the fence, had heard the muffled noise of strange beasts, and noted with growing excitement the hum and rattle of the workmen, the busy activity of the encampment, and all the stir and movement of a great company. Then old Zachary, in his precious buggy, drawn by two grey St Paul stallions, had driven about the town, and shown himself in the liquor saloons, his fat hands blazing with rings. He had told of some new attractions since last year—a pretty girl, who did flying trapeze acts, a Bean-faced man with no ears, and a yellow creature from Penang of unmentionable deformity.

Intense interest was excited in the town, and on that evening the show had been crowded with people, a hot sweltering mass, who pushed and shouted and sang, till the animals had been excited to frenzy by the heat and clamour, and the whole staff of the show, from Zachary in his office to the stable-lads and negro grooms, were utterly tired out.

NOW the long day's work was over, and they were all preparing

to rest, and almost every one was seeking sleep but the little

group around the forge. The bandsmen were putting away their

instruments in the box seats on which they sat; the circus horses

were being rubbed down in the stables; and inside the menagerie

tent the engineer was raking out the fire of the engine attached

to the automatic organ, which all day long mingled its mechanical

music with the complaints of the animals.

The men who were standing round the forge were the heads of the various departments. There was the keeper of the elephants and camels, the keeper of the caged beasts, the stud groom, the smith, who was also the veterinary surgeon, the transport-master, the band-master, and the head clerk and business man, whose duty it was to make all the advertising arrangements. They were all lean, hard-featured men, with long hair and sombrero hats. All of them carried small nickel-plated revolvers in their belts, and their speech was the speech of the bar and gambling-saloon. One might have imagined the knot of men to be bandits plotting in the dim red light of the forge, where bars of iron were being kept at a white heat in case of a disturbance among the animals. The whole scene was Rembrandtesque, if one may say that a painter can create an atmosphere, and the shadowy animals all round added to it something incalculably grotesque. The men were waiting for Zachary and his son, who should give them their orders for the next day.

Presently the father and the son came towards the forge from the ring. George Zachary, the elder, was a large, fattish man, with shrewd, black eyes, and features which had been beaten out of shape in many wild fights. His son Maxwell was a florid young man full of blood, and with a sticky, purple complexion. He had dull grey eyes, reddish under the rims, and they were set very deeply in his head. He was a cruel-visaged creature and his voice was like the bellowing of a brazen bull.

The two men came slowly up the tent talking together. When they reached the group of subordinates and began to give them their orders, there could be no doubt that they had a thorough grip of their work, and were men cut out to organise and command. The old man made his points quietly and quickly, emphasising them with many admonitory wags of his forefinger. There were directions as to forage, the supply of meat for the carnivora, the hours of performances, the advisability of a procession of clowns and camels through the town, all the technical details of a vast and cumbrous organisation. The old man, a veritable Napoleon of the ring, seemed on excellent terms with his men, as he stood helping out his memory by a scrap of paper in his hand.

Whenever he made a joke or flung a ribald witticism among them, his son Maxwell gave a sudden bark of laughter, and rattled the money in his pockets.

This young man, one saw, had no emotions but the elemental desires and fears of the simple animal. Some characteristics from many of the animals about him seemed to have passed into him. There was something relentless and cruel in his aspect. It is exceedingly difficult to judge such a man. To say that his training and environment inevitably predestined him to cruelty, would be to deny that man is above his servants, the beasts, and can ever conquer his lower self. Yet, on the other hand, many of this man's brutalities were committed through ignorance and an utter lack of that half-memory which we call imagination. The soft clay of his brain was moulded by the lusts and impulses of the moment into the shape his passions desired. It is certain that, whatever the mainspring of his actions, Maxwell was a vulgar-minded rascal with an astonishing and almost physical delight in sheer devilish cruelty. No Spanish village boy burning live sparrows in an earthen pot was so callous a wretch as he, and this man, with the red of the sun-strength on his cheeks, had a morose delight in the pain of others, the shameful lust of a Nero, without the excuse of Nero's madness.

The old man, his father, was a hard and sensual rogue, without a care for any one but himself, and as greedy and unsavoury a rascal as ever shamed white hairs, but he was not an unnecessarily cruel man. The rough showmen were intelligences without pity, and hardened to suffering, but they did not take the pain of others as a sweet morsel in the mouth, a gleeful spectacle to gloat upon. In all that crowd of cosmopolitan blackguardism no one was so bad as the younger Zachary. It was visible in his eyes and hands, for this roughly-moulded, ungraceful man had fingers of great length, white fingers with corded knots, which gave them a certain resemblance to the claws of a preying beast.

He stood by his father for some minutes, waiting till all the directions had been given to the men, and then, turning, the two went out across the yard into a wooden bungalow, which had been run up for their accommodation, and in a room of which supper awaited them.

"The takings were forty dollars more than last time we opened," said Zachary, as they sat to the meal. "We shall have a fat month. All the sheep boys are in this town with their wages, and every holy boy of the lot 'll come round each night. I've fixed up the Sentinel with a box and lush free for the staff and their women, when they come in, and the boss is doing an article on the freaks. I saw a proof today in Olancho's saloon—all about the 'Whatisit,' and the Malay, and the Bean-faced Man. It'll wake the married women up, they like those blamed freaks, frightens them, and is as good as a dram. Oh, now I think of it, send a nigger to wash that 'Whatisit;' it's impossible to keep the little hog clean. I don't care what it's like in its cage at night, but I am not going to have it showing on the platform like it's been lately—enough to make you sick; nasty little brute."

"I will," said Maxwell, "first thing tomorrow; and that reminds me about that blasted dwarf; he said when we were leaving Denver, that the first chance he'd got he'd claim his freedom and be off. It doesn't matter here, because they'd laugh at him, but there's lots of places where there would be a big row if people knew."

Zachary swore violently, and banged the table with his fist, the diamonds on his fingers sending out rapid scintillations of light which seemed as if they had been struck out of the wood by the impact of the blow. "Frighten the swine out of his life," he shouted; "half-kill him if you like. I bought that dwarf from Dr Cunliffe for two hundred dollars—he used to use him to wash out his bottles—and he's the best dwarf in the States. I wouldn't lose him for double the money; he's one of our big draws. I could get twenty dwarfs as small as he is, but his head is double the size of an ordinary man's, and the little cuss makes the women laugh till they cry from it. Punish him till he daren't open his mouth."

"I'll settle him, I'll put him to sleep in the 'Whatisit's' cage, that'll keep his mouth shut. I thrashed him with a tent peg all along the curve of his spine the other day, and I'll do it again. That's the worst of him, he got some education and that from the doctor, and he isn't loony like the rest of them. The 'Whatisit' can't do anything but slobber, and the Bean-faced Man is an idiot who doesn't care about anything as long as you give him plenty of meat and don't kick him. Then the others haven't got the spunk to say a word, seems to take it out of them being freaks like. It's only the dwarf that bothers. I believe he gets talking to the others as well. I won't let them be together after the show any more."

"That is the best way, we don't want any damned trade-unionism among our freaks. I should frighten that dwarf as soon as possible or we shall have some swab-mouthed parson coming in and asking him if he's happy and that."

"I'll see to it tonight later; I'm going to see Lotty for an hour first. She's staying at the hotel opposite."

The elder man frowned and drummed his fingers impatiently upon a plate. "I tell you it's no good," he said, "no good at all. You don't want a wife messing round and spoiling your fun. You wouldn't be worth half what you are now to me if you were married. However, I'm not the man to say, 'Do this' or 'Don't do this' to you. You must slide on your own rail; I only give you advice, and it's your own fault if you don't take it—you must make your own little hell for yourself, I don't care. But I tell you this for certain, Lotty won't marry you if you keep on till the Resurrection day. That girl isn't going to be tied down to a travelling showman. She costs me a hundred dollars a week, and she'll get that anywhere. She's a holy star, and she knows it. She's not going to stop in the West, she'll be in New York the winter, the boss turn in the city. You've asked her once already. It's all very well, my lad, but I've got no illusions about myself or about you neither. We can't cut no ice, we're good enough to run a big show and make our chips, but we aren't much prettier to look at than a buck nigger, and a big full-blooded girl like that, training every day of her life, 'll marry a straight man of steel and velvet who'll love her like she wants to be loved. Teeth of a Jew! D'ye think I've spent fifty years on the road all over the world not to know a man or woman when I see them. There's classes and classes, my boy. There's the 'Whatisit' with the blood of a frog and the brains of a maggot, and there's a big straight English cowboy with a little moustache and hair bleached yellow by the sun. What chance have you? Not a damn chance and that's true. Now look here, Max, you don't want a wife. You can buy plenty of love if you care about such, you stay quiet and run along with me and keep the buggy straight."

At the end of his oration, which he had delivered with all the glibness of the showman, making his points by a sudden snapping of the word to be emphasised, Zachary leant back and regarded his son with a satisfied smile. The young man listened carefully, nothing perturbed, and seemed to be weighing his father's words. He knew that his father had seen men and things, and knew affairs, and the mere accidents of everyday life had taught him an ungrudging respect for the old man's savoir vivre. When some dishonest trick was to be played, who was more fertile in resource than his father? When men were to be bullied or cajoled, who could storm or wheedle so well as he? At his side he had learnt all his own cunning, for he had had no other guide.

"It's like this, boss," he said, "just this. I mean to have that girl if I can get her. She wouldn't hear of anything but marriage. You may or may not be right about marriage being a bad egg; that I put away. I think you're right about a girl like that liking a handsome fellow better than me. Well, I'll ask her once more, tonight, and if she won't have me, well, she may go and rot. I'll not trouble her more. But some one 'll have to suffer and I lay to that."

"Right-on, Max," said the old man, "see Lotty again if you like, and do your best. She won't have you, but still try again. I wish you luck; let's have a bottle on it."

He picked up a long tandem horn which rested on a shelf by his chair, and blew a sounding blast that echoed on the night air and made all the dogs in the yard give tongue. It was his humour to summon his servants in this way; he liked the pomp and circumstance of it. A black boy came running at the sound.

"Bring a bottle of wine," he cried, and when the champagne came, the two men drank merrily together in the little room. "Boys 's better than girls," said the old man to himself, as Maxwell went out into the night.

WAKING the sleeping negro watchman, Maxwell passed out of the

heavy gates into the main street of the town. The night was

brilliant as a diamond, and still as a place under the sea. The

air was fresh, and full of a sweet pungency from the plains of

grass and wheat. The hotel where he was going was some hundred

yards away down the street, and as he approached, the musical

twanging of a banjo came through the lighted windows, the genial

rumpti-tum-tum promising merriment within. From where he

stood at the top of the long street he could see the prairie

rolling far away in blue-green waves under the moon. Behind, on

the lower slopes of the hill, clustered the wood and stone houses

of the town. There were few sounds save the banjo, or the

occasional grunting of a sleepless elephant in the enclosure

behind. As in all western cities, on either side of the road were

long rows of trees. To nearly every tree a horse was tethered.

The saloons and hotels are open all night in western America, and

the cowboys and fruit farmers ride into the towns after their

day's work is done, and stable their horses in this primitive

fashion. Sometimes they sleep beside them. Maxwell walked slowly

towards the inn, revolving dimly what he should say to the girl.

His sorry brain resented the necessity for the appeal which it

was trying to formulate. The very nature of the man revolted

against any lordship but his own will. To ask, to be suppliant,

was an unpleasant thing; in fact this vulgar rascal had even a

touch of pride, an emotion which perhaps dignified his

sordidness. It would, he thought, be so infinitely more

satisfactory to catch hold of Lotty and tell her that she had got

to marry him, and then make her sit on his knee and minister to

his entertainment. So he came uneasily up to the verandah of the

inn.

Lotty was sitting at the head of a table, with her arm round another girl. In a lounge chair, sat a beautiful young man with a banjo. He was a boy of some two-and-twenty years, with a brown clear-cut face and blue eyes, and Lotty and her friend were laughing at some anecdote he was telling them. Maxwell went into the room just as the young man rose to go. He noticed that the stranger, as he stood by Lotty making a farewell, was a handsome fellow, not unlike the type that old Zachary's words had conjured up.

Certainly the man and woman made a pair to be admired by any one who could appreciate a fine animal. Lotty was straight as a stalk of wheat, and as supple as an osier. Her gymnastic training kept her eyes clear, her skin cool, and her hair glossy. She wore a long, clinging tea-gown, which showed the noble curves of her figure, and in which, for all its lace and drapery, she looked more like a boy than a girl. A hardy, bold, and self-reliant creature you saw her to be, with a bitter tongue. A shrewish, but a clean-minded woman.

WHEN the youth had gone, and they could hear his spurs

clanking down the street and the noise of his awakened horse,

Lotty turned to the other girl, a circus-rider who lived with

her, and sent her to bed, saying that she would follow

immediately. Then she turned to Maxwell and stood looking at him

for a moment.

"I've been wanting a bit of talk with you," she said; "there's several things you've got to have out with me, you bloody-minded cur." Her strong hard hand opened and shut with gathering excitement, her head was bent forward and shook a little on its poise, her voice was quiet, but it had dropped a full octave in tone, and sounded like the distant tolling of a bell. Maxwell saw at once that he was to have no chance that night, but he resolved to see the thing out. He said nothing at all, but sat down in the chair just vacated by the young man with the banjo. He was in a state of considerable nervous tension at the sudden onslaught, but his mind was perfectly clear. He scowled nervously at her.

"I'm going to talk to you," said the girl quietly. "I'm going to tell you what I thought of you, and what I think of you now. I'll show you, you low devil, what a decent girl thinks of you. You've asked me to marry you twice, and you've come here to ask me again tonight. I would rather marry the lowest nigger in the show than you. Oh, fool and coward, you that dare lift your eyes to me, who am but a circus girl. Oh, coward! May God stab your black heart and let you die; you're too bad a man for me. I know all your wickedness and I'll see you in gaol yet for it. I know more than you may think I know, more than any one knows, saving the wretched creatures you have tortured. I've been among the freaks, and heard with my own ears what you do at night when you want amusement. Do ye never hear that tattooed Indian girl crying? I'll pray that the sound may run in your ears all your life long. You, a strong man with all the brain of a man, went to that little dumb thing, the 'Whatisit'—and kicked it to make it say something. You did, and said things to the dwarf that I hardly like to think of. Oh, and there's much more that I won't trouble to tell you about. When the fur dropped off the Tibetan cat and it couldn't be shown any more, how did you kill it? You know what you did, and curse you for a cruel hound. Sit down, don't come near me; I'm as strong as you, and I'll kill you if you touch me. Now listen here; you know what I think of you, and what every girl in the show thinks of you. You can't boss me like you do the men, who are afraid to say a word, and this is what I'm going to do. As long as I'm connected with this show of yours, if I hear that you have so much as laid a finger on any of those poor creatures in the museum, I'll go straight to the Sheriff and have you quodded before you can chew a fig. And more than that, I'll set a boy on to you, a man mind you, not a fat lump of wickedness like you, who'll break every separate bone you've got. Now you have heard me, and I'll waste no more time on you. If you have never heard before what a girl thinks of such a man as you, you have heard tonight. But remember, what I say I'll do, I will do with no fail; and if you ever dare speak another word to me beyond business matters, I'll strike you in the face."

"I'll kill you if you touch me."

She hissed the last words at him, trembling with hatred, and then with a swirl of skirts left the room.

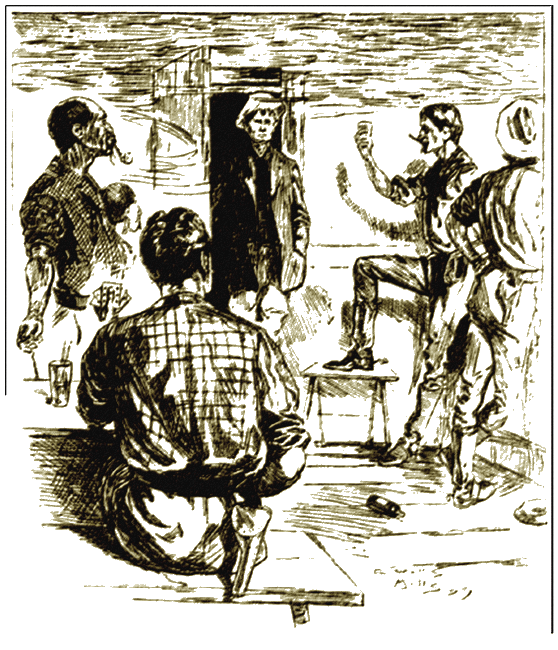

THE man sat motionless, hardly realising the full meaning of

the words he had heard. Bit by bit they percolated his

consciousness, and he understood. He showed no trace of passion

in his face, though his eye seemed a little inflamed, but walked

slowly into the bar saloon, and called for whisky. The room was

full of men playing poker and euchre, and he had perforce to stop

among them for some few minutes, and to answer inquiries about

his show. The scene was eminently picturesque, and Zachary paused

for a few minutes to join a circle of men who were playing draw

poker. A master of the game himself, he took the real pleasure of

the expert in watching the set faces of the players; and when,

after 'rise' had followed 'rise,' till a great pile of dollars

and greenbacks lay in the centre of the table, the cards were

thrown face upwards on the cloth, and he found then he had placed

the winning hand almost to a card, he turned with a satisfied air

to the long, roughly-constructed wooden counter. Some men were

throwing dice for drinks, and they recognised Zachary with a

respectful salute. Two Chinamen in a corner were haggling over

the sale of long, tapering-bladed knives with a young rancher

from Wilson settlement; and a tall, vigorous cowboy, with a touch

of Indian blood in the masterful curve of his nose, that

contrasted strangely with his fair, drooping moustache, was

testing the quality of the steel by whittling heavily at the

birchwood stick that he carried.

OLANCHO'S saloon was the favourite resort of Heron city, and

the white-coated bar tenders were hard pressed to keep up with

the demand for cocktails which they mixed and slung, with

unerring accuracy, to the shouting crowd of customers.

Olancho's saloon was the favourite resort of Heron city.

For a few minutes the excitement of the environment drove other thoughts from Maxwell's brain, but when he was in the long, empty street again, the girl's scornful words came back and stung him into frenzy. Never in his life had such biting words been said to him before, and they lashed him like a steel whip. He was not a man to be much influenced by invective—his life had inured him to that—but this invective was different. It was the contempt, the burning contempt, that hurt so much; and even in his rage he longed for the girl who had so angered him, for as she had spoken all her heart she had looked doubly desirable. He kept forcing himself to remember how beautiful she had looked, and in the remembrance he began to forget the force and point of her utterance. Then once more he felt the lash of her scorn, and it was the more unbearable because in his heart of hearts he knew how right she was, and he knew how dark and foul his cruelty had been. Her indictment was heavy enough, but he knew that she did not know everything—his foulest cruelties were hidden even from her. The Indian girl had not told Lotty all she could have told; and one wretched creature, who could not speak, had a heavier record against his torturer than any one could know.

What did it matter, he thought, about the freaks? They were not like other people. He revolved the whole circumstances in his mind, walking savagely up and down in front of the circus gates, an ugly, vulgar sight in the moonlight. Going through the circumstances as dispassionately as he was able, he came to the conclusion that his doings had been told to the girl by some one who had volunteered much of the information, and he was sure in himself that the informant must have been the dwarf of the show. Maxwell hated this little creature with the huge head and bitter leer. It had before now said some unpleasant things to him, things which made him wince; it had stirred up many of the other freaks to resent their captivity and ill-treatment. Maxwell, joying in the sense of power, had kept these poor creatures in a strict imprisonment. He had constituted himself their gaoler and their king, making their wants and happiness dependent on his will. They had all been powerless in his cruel hands. The only protests had come from the dwarf, whose malformation had not sapped his energy and brain. As Maxwell raged in the street, he felt a mad desire to be revenged on the girl.

She should suffer bitterly, he was determined. Yet as he thought, he could not devise any way in which to harm her. To spread lying reports about her character occurred to him at first, but he knew, on considering the plan, that nothing he could say would hurt her. Physical punishment was impossible; it seemed that he was entirely impotent. It came to him after a time that the girl's informant was at least in his power, and with the thought came the remembrance of his father's words at supper. Here, at any rate, he could work his vengeance. The piteous little atom of humanity who had betrayed him should suffer, and not only he but all the Children of Pain who were his creatures.

His mouth tightened, and his eyes contracted with the lust of cruelty, as he knocked at the gate of the enclosure. He passed through the yard, and, opening a side door with a key, entered the central rotunda, and walked across the tan of the ring.

THE only light in the big building came from the moonbeams

which struggled in from the windows near the roof. The place was

quite silent and ghostly, and the silence was intensified by the

fact that his footsteps made no sound on the soft floor. He

walked swiftly, making for the museum, which opened out of the

menagerie. There would be no one about at this hour, and he was

determined to vent his temper to the full upon the dwarf and his

companions.

The museum was a large tent, round which were grouped the caravans in which the freaks lived. At twelve at night each of them, by Maxwell's order, was shut in its dwelling till morning. Each freak had a caravan to itself, except the 'Whatisit,' who lay in a straw-covered cage, like a dog. During exhibition hours the wretched travesties of mankind showed themselves on platforms in front of their respective dwellings, and the middle of the tent was simply a large open space where the spectators stood. Over each caravan was a gaudily-daubed representation of its inmate.

Maxwell came into the menagerie, where, in the centre, the forge still glowed dully. The stagnant air of the place was full of the smell of the beasts. In the dark he could hear the fierce grinding of teeth upon a bone, and as he crossed to the entrance of the museum, the hummock of an elephant's shoulder showed, a dim, black mass. As he pulled aside the curtain of the museum, he came close to the cage of a great monkey, and he heard it laughing to itself over some memory.

He came into the tent, round which stood the silent caravans. The dwarf's house was at the end, and as he approached it he saw, with an evil satisfaction, that a light came from under the door, showing that his victim was still awake. He was walking swiftly forwards, when, within but a few yards of the steps of the caravan, something caught quickly at his ankles, and he fell heavily face downwards. He was motionless from the shock for a few seconds; and then, as he was pressing on his bruised wrists to raise his body weight, he was struck down again flat by the sudden impact of some heavy weight in the small of his back. With his mouth full of sawdust and earth, and his lips cut through and bleeding, he swore savagely in fear. His immediate thought, as he felt something spring upon him, was that one of the animals had escaped, and was attacking him, but the next thing that happened undeceived him. Two hands gripped his ankles, and rapidly bound them round with wire; a hard boss of wood was slipped into his mouth, and a handkerchief tied on it; and then he was turned upon his back, and saw shadowy figures about him. Somebody struck a match, and he saw a candle being lit in the bend of a fearful shadow, all velvet black. The light was raised, and he saw it was held by the Bean-faced Man. As the shadows played on the awful face, whose features were but tiny excrescences, and which was moulded into a great curve like a bean, he heard a deep and sudden laugh, like the sound of a stone dropped into a well. A white face that opened and shut its mouth like a fish floated round him, and hands were busy binding his wrists in a web of cutting wire. He was dragged some little distance by some one behind him whom he could not see, and then was lifted on to a chair, and bound in a sitting posture upon it. When he was fixed tight and still, a little figure ran round in front of him, and in the orange flicker of the candle he saw it was the dwarf, but half clothed in sleeping garments, through which the malformations of his body showed in all their terrible appeal. There was a grey glaze on his large, intelligent face. The air made by the figures which moved round Maxwell sent hot waves that beat upon his cheeks; and there was a scent of ammonia and blood—the true menagerie smell that the showman knows and loves. The dwarf gave a tiny shrill cry, and the doors of the caravans opened, and grey ghostly figures appeared creeping down the steps. It was exactly as if Maxwell were a fly in the centre of a huge web, and from all sides the spiders were creeping towards him. Soon he was surrounded by monstrous faces, all quivering and unstable in the light of the candle. He caught sight of them coming and going—the white man who opened and shut his mouth continually, the great cranium of the dwarf, the lantern-eyed man, a new importation from a surgical school, whose eyes were as large as eggs; they were all around him. The dwarf was the leading figure, and under his guidance the creatures were arranged round the chair in a semi-circle.

Surrounded by monstrous faces, all quivering in the unstable light.

A great stillness fell upon them. The only creature who moved was the 'Whatisit,' who was dancing up and down in a passion of pleasure at the sight of Maxwell so powerless. The little thing lolled out its tongue, and spluttered with triumph at its protector.

It behaved in exactly the same way in which one sometimes sees a tiny child behave when it is pleased, skipping about in a very ecstasy of joy. Then the dwarf stepped into the middle of the circle and spoke.

"My friends," he said, "our hour has come at last. This man has made our lives hell for months. Unhappy as each one of us must for ever be, we have tasted the bitterness of death at his hands. Because his body is straight and strong, he has had the power to torture us whom God has made in joke. Now it is our turn, and he has fallen into our trap. Is there any one among us who does not feel that he must suffer the penalty we have agreed upon?"

There was no sound in the group except the hysterical sobbing of the Fat Lady, who was a weak and tender-hearted creature, but even from her large heart came no protest, for she knew that the punishment must be. She was only sorry and frightened.

"No one disagrees," said the dwarf. "Listen, Maxwell Zachary, you devil of hell! You have been judged and found guilty, and this shall be your punishment: You shall be made even as we are. You shall be carved, and burnt into a freak; and if you die from it, 'twill be no great thing, and there will be one less bloody-minded villain on earth."

The muffled figure on the chair was quite still. They took it up at the dwarf's order, and carried it into the menagerie, placing it close to the glowing forge. They were a grotesque procession. In front, like some frenzied sacrificial priest, the 'Whatisit' danced backwards, and panting behind came the Fat Woman, her vast bulk heaving with pity. "The Lord He knows! the Lord He knows!" she said continually.

The entrance of so large a concourse of people disturbed the animals. A lion growled angrily, and the monkeys chattered in surprise. Maxwell could not move, though but a canvas wall kept him from safety and freedom. He thought all the time of Lotty.

The dwarf pushed some iron bars into the fire, and opened a case of knives.

He was a grotesque caricature of the surgeon with whom he had lived. He stood by the anvil, which was shoulder-high to him, and looked at the still figure in the chair.

When the work began, a great silence fell upon the place, the captive animals made no single sound, the Children of Pain were absolutely still, the quick, professional movements of the dwarf alone broke the stillness—a monster making a monster.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.