RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"The Story Without a Name,"

Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1924

"The Story Without a Name,"

Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1924

"The Story Without a Name,"

Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1924

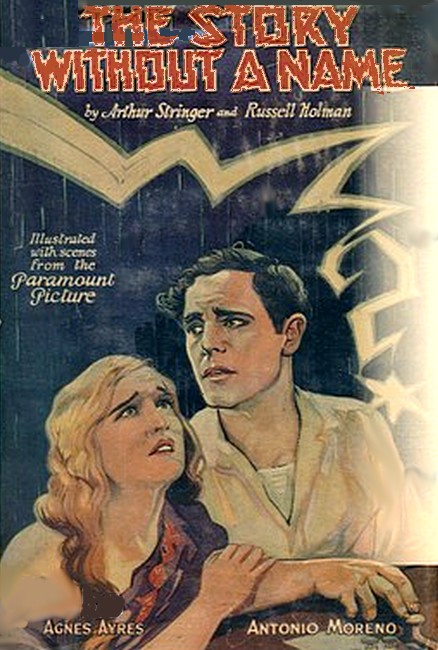

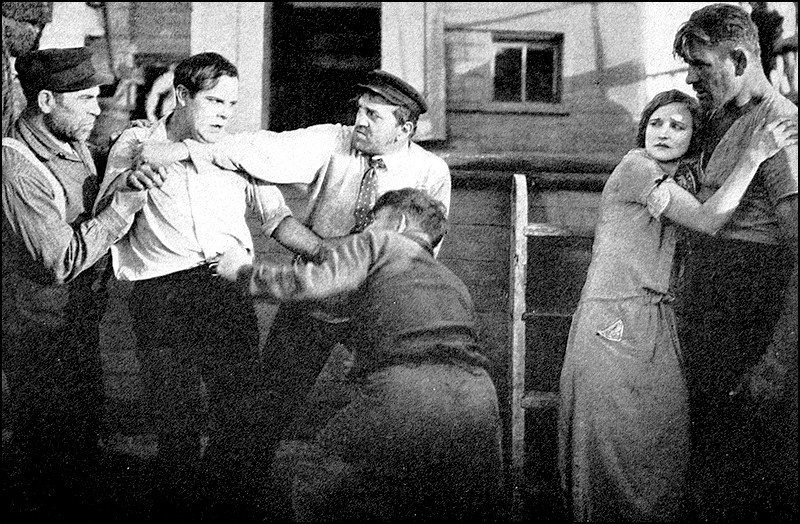

"The Story Without a Name," Film Poster, 1924

Antonio Moreno as Alan Holt and Agnes Ayres as Mary Walsworth.

THE peace of the lazy May afternoon was suddenly shattered by twin droning noises, growing steadily louder, as if two rival armies of bees were approaching at a breakneck pace. The drones increased into roars, roars that echoed through the woods lining the road, as two motor-cars approached, violating all known speed-laws and tearing up the rustic Maryland landscape in brown clouds of dust ballooning in their wakes.

The runabout was racing in the lead, but the big touring-car was pressing it closely, its glinting radiator-cap almost even with the left rear wheel of the other car. Down a little hill the cars swooped, both rising for an instant completely clear of the road as they struck the "thank-you-ma'am" at the bottom. Fifty yards farther on the touring-car had gained until it was exactly abreast of the runabout. They took the sharp turn to the left and plunged up the grade leading to the bridge, neck and neck.

And here came catastrophe.

For the turn and the bridge were evidently surprises to both drivers. It was a small wooden bridge spanning a ravine and a narrow stream running swiftly far below. A stout railing stretched along either side of the road, across the bridge and for some distance beyond. There was room for two cars on the bridge, provided they were driven carefully. But it had not been built for speed maniacs.

The brief thunder of the flying automobiles over the loose planks was followed by a splintering crash. And when the immediate dust cleared away, more dust could be observed a quarter of a mile down the road. But it was not so much dust as before, for only one car was scuffing it up. The hood and front wheels of the other hung suspended in mid-air over the ravine, the glass of the front lights and wind-shield was no more, and at first sight it seemed a flagrant violation of the laws of gravity that the car was there at all and not a twisted mass of metal at the bottom of the rock-studded ravine. Nor was it any less of a surprise to the man and the girl in the once trim red runabout to discover, after blinking and wiggling cautiously about a little, that they were alive and apparently in good health. To be sure, blood was trickling down their faces where small fragments of glass had penetrated the skin, but it was in both cases a negligible amount of blood, hardly more than the man had often caused to flow when he shaved too rapidly. It was not even sufficient blood to prevent the man, who was over fifty and wore the white summer uniform of a naval officer with an impressive amount of gold braid upon his epaulets, to address his first remark in a somewhat shaken voice to the girl.

"Well, Mary, I hope you're satisfied now!"

"I am!" was the wry response.

"I told you you'd break both of our necks some day. You've come pretty near doing it."

"I know," answered the girl, striving to compose her badly shaken nerves. "I was a fool, and it's all my fault!"

"It is, and you are," acknowledged her father, agreeing to both statements.

"But are you sure you're all right, dad?"

"I suppose so," grunted the still indignant naval man.

The girl's face was gradually losing its sheet-whiteness and recovering its accustomed brown and pink. She pushed deft fingers into her disheveled brown hair.

"We should, by rights, be dead," she said with meditative slowness. "But listen, dad, the motor's still turning over. Isn't that a miracle ?"

"It is," acknowledged her parent.

"And what the dickens kept us from going over the bank?" continued the preoccupied girl. "I had absolutely no control of the car. That great selfish brute simply swerved over into us and knocked us off the map. He hogged the road. And never even stopped to pick up our remains."

Anger flamed into her face a moment and then paled away. She leaned cautiously out of the open window of the car and uttered an exclamation.

"Look, dad, we broke that heavy log railing and a piece of it is jabbed in between our rear mud-guard and the side of the car. That's what's holding us. Isn't it a miracle? I believe if I shoved her into reverse, I could back out on the road again."

But Admiral Charles Pinckney Walsworth was in no mood to tempt fate a second time that afternoon.

"You'll do nothing of the kind!" he proclaimed in his sharpest quarterdeck voice. "We'll both get out of here. We'll get out this instant, before we drop into those rocks and bushes. You go first, and take it very easy."

Mary shrugged her shoulders slightly, but obeyed. Struggling briefly with the door, which had been somewhat battered, she opened it, and stepped gingerly out upon the running-board, tilted at a rakish slant, and so into the dusty underbrush and to the side of the road. Her father followed without mishap. By the time they had made this progress, a tall overalled figure, attracted by the crash, was approaching them rapidly. The newcomer proved to be a raw-boned farmer who, seeming a bit disappointed that Mary and her father were alive, mopped his face with a bandanna handkerchief and blandly asked: "Had a mishap?"

"Yes," snapped Admiral Walsworth. "Where's the nearest garage?"

"Latham is the closest," answered the farmer in a soft Maryland drawl.

"Is there a telephone anywhere around here?" asked the admiral. He felt rather ridiculous, his usually immaculate clothes splotched with dirt and grease, his face smeary with blood, and the absence of his cap revealing the sparseness of his graying hair. Admiral Walsworth prided himself always on his appearance.

"There's one over to my place, just down the road a piece," said the farmer, and rather reluctantly led the way.

Mary found that the crash had put kinks into her athletic young body. She even explored a bruise or two as she followed the two men down the road. She was not at all sure that everything was well in her upper rib region, where the steering wheel had dug sharply when the car came to its extemporaneous halt. And she had vague qualms that the cut over her eye, which she daubed furtively with her handkerchief, might leave a scar. This last would have been a calamity, for Mary Walsworth's was the sort of face which stood a distinct contribution to the world's store of beauty. But she resolved to confide neither of her wounds to her father, for the accident had been entirely her doing, she now freely admitted. She had induced the admiral to drop his work at the Navy Building and come with her for a spin into the country through the glorious May sunshine. She had resented the way the big brown touring-car had swung past them and then cut in so sharply that the mud-guards of the two machines grated. She had stepped on the gas, passed and cut in on the touring-car in turn, and flashed a mocking smile at its four male occupants in retaliation for the jeers they had lavished upon her. When the other car set out after her, Mary, her sporting blood aroused, had disregarded the restraining commands of her father and piled on more and more gas until—

"Call Latham 15—Hurley's Garage," advised the farmer when he had escorted them into his stuffy parlor and to the old-fashioned telephone placed against the wall.

Hurley's, two miles away, assured the admiral that they would send a car right out.

"My missus has gone t' town," explained the countryman, who was impressed, obviously, with the gold on Admiral Walsworth's shoulders, "or she'd make you a cup o' tea or something. You're welcome to sit here and wait for Hurley if you want to. He has t' pass this way."

"No, thank you," snapped the admiral. "But if there's some place where we can wash up a little—"

He sniffed when he discovered that the toilet facilities consisted of a basin filled with ice-cold water drawn from an outside pump. Mary made temporary repairs to her face and hands, answering their host's questions about the accident cheerfully enough, and the latter confined his conversation to her after that. The admiral followed her at the basin and even attempted to use the almost toothless comb that was offered him. Then he thanked the rustic rather bruskly and announced that they would return to the wrecked car and await their rescuer, and incidentally discover the whereabouts of his missing cap. For an admiral without his cap is like a ship without a rudder.

When the man from Hurley's rattled up in a dusty Ford touring-car some fifteen minutes later, he proved to be a husky, dark-haired young chap in brown overalls who pleased Mary at once with the manner in which he sized up the situation and took command of it.

She resented it, however, when, stepping on to the running-board of the car, she suggested, "The engine can be started. I think I can get in and back the car out," and the garage-man answered abruptly, "Keep out of the car, please. It may topple over into the ravine any minute."

Mary Walsworth was not used to being ordered around, and even the admiral bristled at the young man. The latter, ignoring them, produced a rope from the tonneau of his Ford and set about fastening it to the rear axle of the runabout. Looping the other end of the rope about the rear axle of his own car, he called sharply, "Stand clear, please," and swung in behind the steering wheel of the Ford. Admiral Walsworth, who had recovered his precious cap from underneath the injured machine, straightened up and shot a withering look at the mechanic's back, but obeyed. There was a splintering of wood and a screech of metal as the Ford started and a moment of uncertainty as to whether it possessed sufficient power to pull the larger car clear. But then the wedged-in log yielded, and the strange convoy was soon in the middle of the road.

"If you two will jump in with me," suggested the young man, mopping his perspiring face and obviously pleased that his plan had worked, "I'll take you and your car back to Latham. You're from Washington, aren't you?"

"Yes," Mary answered, "and we'd rather like to get back there. We both have dinner engagements. And Latham isn't on the railroad line, is it?"

"No," said the young man. He was a very nice-looking young man, Mary decided. Black, curly hair and brown eyes set in tanned face with a very square jaw. "But I can get another car and drive you in. It's only eighteen miles."

"That would be fine," said Mary with considerable relief. She knew the recriminations her short-tempered father would heap upon her if he was forced to miss a dinner engagement on account of her folly. Especially this engagement.

Arrived in Latham, a sleepy little one-street town as antiquated as if it were 1864 instead of 1924 and hundreds of miles from a railroad instead of less than an hour from either Baltimore or Washington, they drew up in front of Hurley's Garage, a surprisingly modern-looking establishment. Their arrival brought out the proprietor, a corpulent, elderly man, who inspected the wrecked runabout and said he could repair it in a week and seconded his assistant's idea that the latter drive the Walsworths into Washington. The young man in the brown overalls disappeared for about ten minutes, during which the admiral muttered impatient sea-going things under his breath.

"Alan's gone home to change his clothes," Hurley explained to Mary. "He lives just down the road. You can see his house from here."

"Then his name is Alan," Mary mused.

"Yes—Alan Holt. Mighty nice boy, too."

Holt was dressed in a neat brown suit and had slicked up his hair when he returned. Without a word he started backing out one of Hurley's touring-cars, and Mary, without consulting anybody, slipped into the front seat beside him, leaving the tonneau to her father.

"You're not such a slow driver yourself," Mary suggested slyly, after they had reeled off five miles or more and her companion showed no signs of speaking to her.

"You said you had a dinner engagement, Miss Walsworth," he reminded her. "And it's six now."

She started. "How did you know my name?"

He smiled. "I served in the Atlantic Fleet during the war. Your father came aboard our ship a couple of times. I was on a destroyer."

"What branch of the Navy were you in, Mr. Holt?"

It was his turn to be startled. But he guessed correctly that Hurley had been gossiping, as usual. "I was a junior lieutenant, engineering."

"But how do you happen now to be working in—" Then she blushed and caught herself.

"How do I happen to be working in a country garage?" He was not in the slightest perturbed. "Well, my father's dead, and my mother didn't want to leave Latham. I'm all she's got. And, besides, veterans can't be choosers where they work these days. can they? If my dad hadn't died, I'd probably have gone to Boston Tech and been an electrical engineer. And if it weren't for mother, I'd maybe have stuck in the Navy. But I'm satisfied."

Mary decided, from the way he unconsciously flexed his jaw and from the wistful look that flitted momentarily into his dark eyes, that he wasn't.

"Why do you say you're satisfied?" she finally asked.

"Because I'm working on something now," Alan explained after a little hesitation and with a slight backward look toward Admiral Walsworth, who was slumped gloomily and most unmilitarily in the comfortable back seat, "that may take me out of the garage."

"Really?" encouraged Mary. "An invention?" She suspected shrewdly that if this young man knew her father's name, he knew also that Admiral Walsworth was head of the Naval Consulting Board and was perhaps not without a hope to interest the naval man in some scheme or other. One or two young men had already sought to use Mary as a means of getting in touch with her crusty and quick-tempered parent, and she had resented it and taken pleasure in thwarting them. But this was such a frank, patently honest young man, even though the impersonal manner in which he addressed her and looked at her was not flattering.

"You've been reading in the papers about this 'death ray' that a chap from Europe claims to have invented?" asked Alan. "An electrically controlled device that will sink ships, kill people, and all that?"

Mary nodded.

"The thing is obviously a fake," Alan went on. "I know, because I've been working on something like it myself in my spare time ever since I came out of the service. Only mine is going to be a success. Don't smile. I can prove it. I've already done considerable with the miniature model I have in my work-shed at home. There are one or two things I have to perfect yet. Then I'm going to offer it to the government."

Mary was interested. Impractical as the thing sounded, here was not the wild-eyed, rattle-brained type of inventor. Alan's words carried conviction. She turned around to her father.

"Dad, Mr. Holt has invented something that ought to interest you. A 'death-ray' device for sinking ships and things by radio. Couldn't you let him make an appointment with you and talk it over?"

But Admiral Walsworth was chiefly interested at that moment in the fact that they were entering the suburbs of Washington and that he would in half an hour be in the presence of a charming dinner-companion.

"I've had exactly twenty 'death-ray' inventions offered me in the last seven months," he said ungraciously. Ever since this fool talk has been in the papers. None of them is worth anything. The thing is simply impossible."

Mine isn't, Alan snapped, keeping his eye on his business of steering but talking loud enough for the admiral to hear.

"I really wish you'd look Mr. Holt's invention over," pleaded Mary. Her father glanced at her sharply. Why was she taking such a sudden interest in this fellow, a mere garage employee, anyway?

"If Mr. Holt will deliver me at the Hotel Selfridge within ten minutes," scowled the admiral, "he can write me a letter about his scheme and ship the model to me, if he has any."

All right, Alan told him, and stepped on the gas.

They were soon dodging through the traffic in the heart of Washington. Crossing Pennsylvania Avenue, Alan located the quiet shady street upon which the Sel fridge, an aristocratic little menage, an abode of senators and other high officials, was located.

When the car had stopped before the door and Mary had alighted, she turned to their driver and said, smiling, "I surely hope father will see possibilities in your invention and tell you to come to Washington and demonstrate it before the Board. When you do, you must look me up."

"I will," Alan answered, and for the first time his face showed its awareness that for nearly three-quarters of an hour it had been very near to a very attractive girl.

A VERY dark brown head and a blond head were bent over a little black box mounted on a crude work-bench. The owner of the tousled blackish hair was manipulating the switch and the dial set in the face of the box and watching anxiously the thin black needle in the clock-like arrangement under the dial. Suddenly he uttered a low exclamation, and both heads were sharply raised and pointed across the room where a piece of tin mounted upon asbestos was nailed to the plain boarded wall. The dark-headed young man jumped up and hurried over to the tin. His serious, rather moody, tanned face broke into a smile as he looked at the black smudge that soiled the shining brightness of the tin.

"I got it that time, Don," he said to his blond companion, who was dressed in the uniform of a sergeant of Marines.

Don Powell slid over and inspected the tin.

"Say, you did at that," he exclaimed admiringly and a little awed. "Alan, you've got something real here.

"I will have after I work it out some," agreed Alan Holt. "The focus is not nearly sharp enough. I'm afraid I'll never be able to do much just with a model run by storage batteries. If I only had a lot of money, or could get it, and could go into this thing right.

"Haven't you heard from the Navy yet?"

"No, I wrote to Admiral Walsworth over a month ago and haven't had a word from him. I guess he thinks I'm just another crank."

"If you could only get him down here and show him what you've just shown me—"

"A fine chance," Alan said somewhat bitterly.

Don Powell glanced at him sympathetically. Don, a sturdy young chap of twenty-two, a couple of years younger than Alan, was a native of Latham, and Alan's best friend. He was also the only person besides his mother whom Alan had taken into his confidence regarding the radio triangulating device he was working on in the little workshop he had built in the rear of the Holt home. Alan had always been interested in electricity. He had been one of the pioneers in radio, having constructed for himself a receiving and broadcasting outfit long before they came into general use and radio developed into the fad of the hour. Now he was quite sure he was on the track of the most important invention since wireless had been discovered—a device for triangulating radio rays, concentrating them into a single ray of such tremendous force that it would sink ships and set fire to cities. A thing so dreadful in its possibilities that at the first signs of success in perfecting it, an awesome fear had gripped Alan along with the feeling of exultation. It was almost like attempting to tamper with something superhuman.

He had been working on the triangulator now for nearly two years, He was so constantly at it that his eyes had become affected, and he was forced to wear tortoise-shelled glasses when he worked, giving himself a somewhat owlish look. "They make me look more like an honest-to-goodness inventor," Alan had assured his mother, half gaily, when she protested regarding possible inroads upon his health that his constant application to his workshop would cause. Mrs. Holt was of Quaker stock, and it was only because of Alan's assurance that his device, if successful, would not be used for destruction but to end all wars that she approved of it.

"Once I've got it in shape," he outlined his intentions to her, "I'll offer it to the Navy. If they take it, this country will be placed in a position where the rest of the world will be so afraid of us there'll never be another war involving us. And the United States will be able to prevent wars between other nations simply by threatening to jump in with the death ray and burn the offenders off the face of the earth."

But so far, despite three letters to Admiral Walsworth describing his device and his offer to come to Washington at any time and place his model and his own services at the disposal of the government, Alan had found his native country indifferent to the mighty asset with which he was altruistically seeking to present it. He realized that the invention was still far from being in a state of perfection, but it had demonstrated to him even now that he was on the right track at last. His recent experiment with the piece of tin had proved that all he needed was a refinement of the instrument that would permit a sharper and surer focus and the means to construct a real machine of many times the power and size of this one. He had worked it all out, just how this real machine was to be made. He even had blue-prints of it in the drawer of the old-fashioned bird's-eye-maple desk, that had been his father's, right here in his workshop. But what was the use? If his country didn't want it, he might as well quit. He wouldn't commercialize this death-dealing monster, peddle it surreptitiously among the representatives of foreign countries, as that fellow in the newspapers was doing, under any circumstances.

"The old man, of course, thinks you're just another one of these crank inventors who pester him," said Don Powell thoughtfully, referring thus disrespectfully to Admiral Charles Pinckney Walsworth, but feeling justified in doing so since he was on a forty-eight hour week-end leave and consequently outside the jurisdiction of the Washington Navy Yard. "Now if you could only break into the limelight like this death-ray chap in the newspapers, they'd pay some attention to you. A sergeant at the barracks who has been on orderly duty up at the Consulting Board was telling me on the q.t. that the big boys in the Navy have looked over this newspaper chap's 'death ray' and pronounced it the bunk. That makes them twice as skeptical as they might otherwise be of anything like it. But if you could manage to kick up a lot of talk about yours, they d feel they had to give it the once-over."

"Well, if they did," Alan said, confidently if a bit gloomily, "I could show them something that would open their eyes, even with this crude model."

Don's face suddenly brightened.

"There's a man named Waldron," he proposed, "a reporter from the Washington News who hangs around the barracks a lot after news. I tip him off sometimes, and we've become quite friends. Suppose I tell him about you. He might see a Sunday story in it, particularly because of the public interest that's been stirred up about this death-ray business. Perhaps he'd come down and talk to you. What do you say?"

"Oh, send him along if you like, Don," Alan replied. In spite of the successful outcome of the test of his machine he had just made, he was in a discouraged mood. "Meantime, phone your folks and tell them you're staying to chow with mother and me. And now let's go and wash up. Mother called us a half-hour ago."

Tom Waldron of the Washington News proved much easier to approach and more credulous than Admiral Walsworth, and three days later Dave Hurley summoned Alan, overalled and very greasy, from under the innards of an automobile with which he was tinkering, to confront a lean, sharp-eyed, middle-aged stranger.

"Holt?" asked the latter. "I'm Waldron of the News. Friend of Powell's."

Five minutes later Alan had secured a brief leave of absence from the garage and was pointing out the features of his mechanical obsession with carefully modulated enthusiasm to the reporter. A few deft adjustments, and he was repeating the experiment with the tin sheet which he had performed for Don.

The reporter took a few notes on scraps of paper which he had wadded in his pocket. "It's a story, all right," he admitted. "I'm not mechanic enough to write it from the technical angle, and probably you wouldn't want me to give away too much, anyway. But look for the News a week from Sunday. By the way, I understand you tried to get the Consulting Board people interested."

"Yes," answered Alan. "But I didn't get a tumble."

"Walsworth is a crab," said the reporter, "and rather stupid. But they may sit up and take notice when they read my story."

Alan wondered if this were just egotism on this rather cocky reporter's part. He even wondered if Waldron would ever write a story.

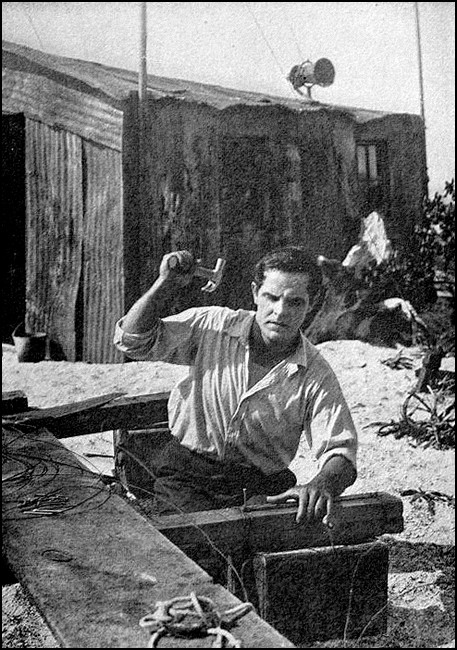

But ten days later the story appeared, even to the picture of Alan which he had reluctantly yielded to the newspaper-man, though he had refused to permit a photograph to be made of his invention. The story occupied a prominent place in the magazine section of the paper along with "Heiresses I Have Wooed and Won. By Count Boni de Merchante" and "Stage Favorite Reveals Beauty Secrets." Not a very dignified environment for a scientific discovery that might revolutionize the world, thought Alan, and he felt a vague resentment against Waldron, who had probably in his own mind classed Alan's invention with the bogus confessions of the French nobleman and the worthless beauty bromides of the theatrical celebrity. The story, Alan was convinced, would probably do more harm than good.

But at least it got action. For, three days later, Alan was again called from a repair job by his employer, and the interruption this time was caused by a dark, foreign-looking gentleman with waxed, authoritative mustache ends, a bamboo cane, and immaculate attire that fairly cried protests at being whirled over dusty country roads in the smart runabout car that stood at the curb outside the garage.

"Mr. Holt?" asked the stranger in a slightly foreign accent. "I should like ver' much to see you privately."

With a disapproving sniff Dave Hurley moved away.

"I understan' you have a radio invention, the stranger continued in a low voice. I have read of it in the paper. I am ver' much interested in radio. Perhaps you will show it to me. I can do you good maybe."

Alan did not particularly fancy the looks of this stranger, who announced his name as Christoff, was shifty as to eyes and slightly redolent with perfume. Nevertheless, since it was the noon hour anyway, the young man doffed his overalls, washed up and slid into the runabout with his visitor.

Out in Alan's workshop Christoff listened intently to all that Alan had to say about the death-ray machine. Pie darted sharp black eyes everywhere as young Holt shoved on the juice and repeated for the third time the tin-sheet experiment. Christoff, without asking permission, even laid hands upon the lever and the dial and himself manipulated them.' He further aroused Alan's suspicion by requesting that he remove the face of the black box and show the mechanism inside.

Alan's lips tightened and he glanced keenly at his presumptuous caller. "No," said Holt, "I'm not showing the inside of this thing to anybody. I hope and expect the machine will be the property of the United States Government some day, and so it's a secret."

"You would, I suppose," Christoff suggested suavely, "dispose of it elsewhere, if you could get your price, would you not?"

"No. If the government doesn't want it, I'll break it up."

"The government is, if you will permit me to say it, a leetle slow in seeing the value of things like this. And if they do see the value, Meester Holt, they do not pay ver' much."

"I'm an American, Mr. Christoff, and it's a matter of duty and principle to me."

Christoff shrugged his trim shoulders.

"I know. But you have offered your invention to the government. They are not interested. I am. I do not say that your machine will do what you think it will. Maybe not. It is ver' crude now. Enlarged, it might be a complete failure. However, I will take a chance—my partners and myself. I will give you five thousand dollars for this model and any plans for a regular size machine you may have. What do you say?"

Alan shook his head in the negative.

"Ten thousand?"

"No. I'm not interested in selling to private parties, I told you."

"You will reconsider, maybe."

The black eyes of the stranger had narrowed. His swarthy face bore a baffled and slightly sinister expression.

"I don't think so."

"Here is my card, with the address on it. You can get in touch with me any time."

Alan took the proffered card. Five minutes later he was saying good-by to the stranger at the gate of the Holt home. He walked thoughtfully back toward the house. But he did not go in at once to the lunch which his mother had waiting for him and to which he had not invited Christoff because he did not like him and was anxious to get rid of his vaguely disturbing company. He followed the path around the house to his workshop, entered, and, approaching his precious machine, removed from it the enfilading key, which was the prime secret of the invention and without which the mechanism was powerless. He could not at the time have told why he did it, but he knew it had something to do with the aura of suspicion which somehow surrounded this Christoff. Having slipped the key into his pocket, Alan went in to lunch.

Alan spent an hour in his workshop after dinner that night. When he had finished, he not only again placed the enfilading key in his pocket but, unscrewing the face of the container, disconnected some of the more important wiring and thrust the wires in his trousers pocket, along with the key. Then he replaced the front of the machine. He also made sure the door of the shed was securely padlocked. Then he laughed uneasily at himself and, wondering why he was such a fool, went to bed.

After breakfast the next morning, the same vague suspicion drew him out to the workshop for a hasty glance around before he left for the garage. There, he saw at a glance, his suspicion had been confirmed. The padlock had been smashed during the night. With a little cry of rage and fear, he bounded into the shed. Then his arms dropped to his side and he stood stunned. The death-ray model was gone. The black box had been unscrewed from its base on the work-bench and had vanished utterly. Even the tin-sheet had been removed from the wall opposite.

Christoff! He was at the bottom of this. Alan pulled the stranger's card from his pocket and glowered at it. Then he went grimly into the house and called the Washington Navy Yard. After five minutes the reply came over the wire that Sergeant Powell was at mess and couldn't be disturbed. Would Mr. Holt leave a message? Alan requested that Sergeant Powell call him at Hurley's Garage as soon as possible.

Don telephoned about noon, and Alan told him the news, repeating Christoff's address from the card to the Marine and asking that he look the suspected stranger up.

"That must be somewhere near the Hotel Self ridge," Don replied. "I'm off at noon to-day for a forty-eight. I'll look this bird up and see what I can do. I'll see you in Latham this afternoon."

When Don arrived at Hurley's Garage about four that Saturday afternoon, he drove up in the dirty Ford sedan owned by Tom Waldron of the News, and Waldron was in the front seat with him.

"It's the Selfridge, all right," Don told the eager Alan, "but they don't know anybody named Christoff there nor anybody answering your description of him." He turned to his traveling companion. "You've met Tom Waldron, of course, Alan. I tipped him off, and he wanted to come along."

"I want to apologize, Holt," said Waldron frankly, "at the rather flippant way I wrote up your invention. I'll admit I wasn't terribly impressed at the time. But I am now. If somebody's trying to steal it, there must be something in it. Particularly if the thief's the party I think it is."

"You know this man Christoff?" Alan asked

"I'm not sure. But I've a sneaking suspicion he's connected with Drakma's gang." When this apparently did not convey any startling enlightenment to the two Latham men, he asked in surprise, "Haven't you heard of Drakma? I thought everybody had heard of that fish, although nobody knows much about him. He's Washington's big mystery. Travels around in the best of society, has plenty of coin, entertains lavishly, knows all the senators and congressmen and diplomats! Where he gets his money and what he does for a living, people don't know. He's been several times suspected by the Secret Service of quietly appropriating government secrets. You remember the big hullabaloo there was in the paper about the Haitian treaty disappearance and again when the secret wheat code was stolen from the British Embassy? The insiders knew Drakma was suspected, in both cases. And he's also supposed to be the largest wholesale bootlegger in the United States. But nobody has been able to hang anything on to him. My paper's been after him for two years, and I've done a lot of investigating myself, both on assignment and privately. I've become acquainted with the faces of a number of people who, I think, are his operatives. Anything like your death-ray machine would be fine prey for Drakma. And this fellow Christoff of yours certainly wears a Drakma make-up. He's a Russian and very close to Drakma. Probably they read my story about your invention and went out to get it. Offered you money at first, though the chances are they never intended to pay you, and then stole it with the intention of selling it to some foreign government."

"But what can we do about it?" Alan asked.

Waldron shrugged his shoulders. "Nothing, I guess. Trying to get Drakma is like butting up against a stone wall. Two-thirds of Washington would say you were crazy if you even intimated he was crooked. Is your whole invention lost, now that the model is missing?"

"No," Alan admitted. "I can eventually construct another model. And I luckily had sense enough to pull some of it apart so it won't be much good to them!"

"Well, you should worry then," was Waldron's philosophic comment. "Meantime I'll phone the story of the theft in to my paper. They ought to give it the front page, and maybe that will bring you to the notice of the Navy people. I'll try to pull some wires there. I have a slight drag, and I'm really interested in this thing now. And I'll nose around among Drakma's people, too.

As predicted, Waldron landed the story of the theft of Alan's invention on the front page with a two-line scare-head. The result was surprising. It came in the form of a letter in a feminine hand addressed to Alan at Hurley's Garage. He wiped his greasy hands on his overalls and opened the dainty missive. He read :

"Dear Mr. Holt:

"I was so sorry to hear about the theft of your invention. I showed the newspaper story to my father, and he was interested at once. Yesterday a reporter from the News, a Mr. Waldron, came to the hotel for an interview with father and spoke about you and your death ray. I think you will hear from the Navy Department soon now, and I am very glad. You know it is quite characteristic to be more eager to get something when you know some one else is after it.

"Sincerely,

"Mary Walsworth."

Alan put the letter into his pocket thoughtfully. The attractive girl who had sat beside him on the trip to Washington over a month ago had been in his mind more than he would care to admit, even to himself. Mingled with his satisfaction that he was at last to get some recognition from her father was the thought that she still had sufficient interest in him to influence her to sit down and write to him.

True to Mary's forecast, the letter from the Navy Department arrived a few days later, couched in the stiff formal language of the Service and signed by Admiral Walsworth. It invited Alan to appear before the Consulting Board at eleven o'clock a week from the following Tuesday morning and submit his invention. It hoped by that time that he would have constructed a new model and be prepared to demonstrate it. Alan, who had spent two years building his first model, smiled grimly. But he could do it. He had to do it.

Over the quiet protest of his mother, he gave up his job at Hurley's and prepared to spend every minute possible of the next two weeks preparing for the ordeal—and big chance—of his life before the Naval bureaucrats at Washington.

"IF you will report here at ten o'clock: on Thursday morning," they had told Alan, "we will let you know our final verdict." And he had with difficulty restrained a sigh of utter mental and physical weariness and agreed. Indeed he had been through so much during the past two weeks in Washington that he had nearly lost interest in what that final verdict might be and was only concerned about cutting his way out through this seemingly interminable maze of bureaucratic red tape and getting back to the simple peace and quiet of Latham. Washington had only one attraction for him. She was blonde and lithe and had nearly lost her life in an automobile crash on the Baltimore Turnpike. And her name was Mary Walsworth.

Alan had seen much of Mary since meeting her again by accident that first day he had appeared before the Consulting Board, and, coming out of the Navy Building after the interview, had spied her, fresh and fragrant as apple-blossoms in cool summer white and smiling a welcome to him, sitting at the wheel of the repaired runabout at the curb. She was waiting for her father, she explained as she extended her hand in greeting.

"He'll be out in a few minutes," she invited. "If you've nothing more exciting to do, jump in and wait with me and I'll drop you at your hotel afterward."

Alan accepted, and in a twinkling he was sure he had not been foolish at all in keeping her face so constantly in his memory after that fateful crash at the Mill Bridge.

"Well, I see you've been bearding the lions in their den," she smiled. "How did you make out?"

"I don't know," he confessed. "They told me to leave my model. And I'm to come back next week."

"That sounds favorable," she encouraged. "I know father. He's very cautious. But he's just, too. If he didn't turn you down flat, it's a sure sign he is very much interested."

Alan did not tell her that Admiral Walsworth had been the most skeptical and supercilious of the officials who had questioned him. There seemed more important things to talk about. But five minutes more conversation with Mary, not altogether about inventions, and Alan saw, with regret, her father approaching. Nor did the frown and almost discourteous nod which the admiral shot Alan's way, as Mary explained that they would drop Mr. Holt at his hotel, escape the young man.

The conference with the Consulting Board proved only the first in a series. They questioned him until his brain was tired and his eyes were popping out. They brought electrical experts and had him rip his model apart and put it together again before their eyes. They took him out to the Aberdeen Proving Grounds and conducted experiments with high explosives. They disapproved of his leaving Washington even for a few hours to dash home and see his mother and accumulate fresh clothing, which, since he had expected to be away only a day or two, he badly needed. They kept insisting upon the most profound secrecy and issued orders to him so arbitrarily that he wondered if it were again war-time and he was back in the Navy. He even suspected that they had a Secret Service operative on his trail to see what he did in his few spare moments.

But now, he told himself grimly, as he waited in the anteroom outside Admiral Walsworth's office in the Navy Building, it would soon be over. He had definite assurance that he would be told that morning whether the government would condescend to dally further with the Holt Death Ray. This final conference had been set for ten o'clock, and it was now half past. But Alan had long since discovered that the promptness of Navy men varied inversely as the amount of gold braid on their shoulders, and Charles Pinckney Walsworth was an admiral.

Indeed it was eleven o'clock before the uniformed orderlies who stood near the door exchanged a warning growl, snapped to attention, and Admiral Walsworth strode in, erect and immaculate in his white summer uniform, and without a glance to right or left disappeared into his office. It was another ten minutes before a buzzer sounded and Alan stood before him.

"Good morning, Holt," boomed the admiral, without asking Alan to sit down. The Navy man pondered a moment. "Are you in a position to take up duty at once with this Department as a civilian employee?" he finally asked.

Alan nodded.

"In that case," the admiral continued, "the Department is prepared to conduct further experiments with the device which you have submitted. We have selected a site on government property in a secluded spot about twenty miles from here, near the Potomac, and will construct the two towers which you specify in your blue-prints and will supply the equipment and personnel necessary. You will construct a death ray machine there of the highest power possible and make the tests that will determine if the invention is really of any use to us. Upon your conclusive demonstration of its practicability, you will be paid a reasonable amount and royalties thereafter, the contract to be signed when the Department is convinced that the machine is a success. Is that satisfactory ?"

Alan nodded in approval, surprised at himself for not being more greatly thrilled.

"As I told you,,, he explained, "Em not concerned about making a fortune out of this thing. I hope I'm patriotic enough for that."

Admiral Walsworth regarded him quizzically. He was not used to altruistic inventors. Usually these chaps wanted the earth, believed the government was rolling in wealth, and tried to annex the Treasury on their way out. But Alan was different.

"Very well," said the bureaucrat. "Another thing—we wish these experiments to attract as little attention as possible. Consequently I do not wish to assign a large force of assistants to you. There are people, you know, who would not stop at unscrupulous means to get possession of such a thing as this, to dispose of elsewhere."

"Such as my friend Christoff," suggested Alan.

"Oh—that!" pooh-poohed the admiral. "I am not particularly impressed by the theft of your play model. He may not have had anything to do with it." Indeed, to Alan's irritation, Admiral Walsworth had on other occasions intimated that the stolen model had perhaps been young Holt's own idea of a way of securing publicity for his invention, even a frame-up between the youth and Waldron, a very smart newspaper man.

"One assistant would be enough, as far as I am concerned," offered Alan.

"Have you any one in your mind ?"

Alan thought. "Sergeant Donald Powell, of the Marine Corps, has worked with me some on the machine," he said. "He knows radio, and he's thoroughly trustworthy. He's on duty at the Washington Navy Yard now."

"Very well. I will assign Powell to you. Also a Marine to guard the towers. The material should be assembled in two or three days. You will then report there. It is about half a mile from Duryea, the nearest railway station, on a branch of the Atlantic Coast Line, near the Piney Ridge Golf Club. Meantime I will have you placed on the pay-roll, and you will start drawing a salary from to-day."

When Alan left the Navy Building after this momentous meeting with Mary Walsworth's father, Mary's runabout was again parked at the curb, and Mary was waiting patiently behind the wheel. But this time she was not waiting for her father. Indeed, she would have been very greatly disappointed had the admiral decided to shirk duty for the day and joined her. Her appointment was with Alan, and she was looking forward eagerly to crowning him, figuratively, with the laurel of a conqueror. For, in answer to her eager inquiries at breakfast, Admiral Walsworth had reluctantly yielded the information that the Navy had decided to "play with Holt's invention for a while." At her exclamation of exultation at this news, Walsworth had looked at her and testily remarked, "You're rather interested in this young fellow, aren't you?"

The vivid blush that stained her cheeks did not add to his peace of mind.

He regarded her sternly, "Now don't go and do something foolish," he warned. "Just because this chap happens to be well set up and good-looking, don't let him turn your head. He's only a garage mechanic, you know. A girl in your position can't afford to mix in with such people."

Mary was still flushed, but now anger was mingled with her blushes. "Alan is as good as gold," she asserted. "I've met his family, which consists of his mother and himself,,and she's the sweetest old lady you've ever seen. And a Virginia Latham, when it comes to considering ancestors, which doesn't mean a thing to me, is some pumpkins, as you know."

So—he's introduced you to his family?"

"Why, yes. We drove over there the other day."

"You know I don't approve of you running around with this garage fellow, don't you?"

But Mary Walsworth merely laughed. Her father was an old dear—at times. But he had always had more success managing a battle-ship than he had in managing his own daughter.

As soon as Alan appeared from the marble-and-concrete recesses of the Navy Building, Mary called out, "Hail the conquering hero!" And as he climbed, smiling in sympathy with her enthusiasm, into the low seat beside her, she continued: "I knew you would put it over, Alan! And now we'll go for a drive out into the country and you can tell me all about it."

"If you'll stop first at my hotel while I drop a line to my mother, I'll be more than glad to go," he agreed. Never, he felt, had Mary looked so charming, so utterly desirable.

When she had slid the car to a halt in front of the modest little hotel where he was stopping, he sprang out, with the promise that he wouldn't be a minute, and, not even waiting for the elevator, dashed up the stairs two steps at a time. Not even the pleasure of letting his mother know about his success could keep him long from Mary that day.

But as he bounded into the small hot room, he stopped suddenly and listened. Despite the commotion he had made in flinging the door open, he thought he had detected a scurrying noise from within the room. Now all was quiet, but a vague uneasiness gripped him. He had a feeling that he was not alone. He glanced alertly around, but could see nothing amiss. The cheap pine bureau, the white iron bed, the lone and slightly rickety chair, with the hot noonday sun pouring in—everything seemed quite as usual. He had about decided his suspicion was groundless when the slight sound of a human sneeze, with incomplete success stifled, came to his ears. He glided softly toward the bed, stood there an instant, then dropped swiftly to the floor and grabbed violently for the pair of huddled-up legs that met his lightning glance. Before their owner could struggle, Alan had yanked him out into the open and flung himself upon him.

It was Christoff.

The battle was short but fierce. Christoff was no longer the suave bargainer. He was a dark fighting animal that did not hesitate to try to sink his teeth into the sturdy arms that held him and kick and heave with a ferocity that almost unseated Alan. But the young inventor's attack had taken Christoff unawares and the grip the country boy had secured upon him thereby was too strong. Eventually the dark man's struggles calmed and Alan was able to rip a sheet from the bed and bind him fast. Then Alan rose, lurched and braced himself at the bed-post a moment to get his breath and balance back, and telephoned the house detective.

"I caught this man under my bed. He was evidently trying to rob me," Alan explained to that burly, rather stupid worthy. "And I want him held and his record looked up." When he had delivered his captive over into the detective's charge and the two had departed.

Holt took a look around the room and discovered, to his relief, that Christoff had evidently been disturbed before he had a chance to steal anything. Alan thought he knew what the sinister visitor was after—the blueprints of the death-ray machine. Probably he had discovered that the model he had taken at Latham would not work and sought something more useful. But his visit would have been useless in any case, for the precious plans were resting at present safely in the big vault in Admiral Walsworth's office in the Navy Building. Alan had taken that precaution.

As Alan walked into the bathroom, bathed his face, combed his hair anew and adjusted his disheveled attire, he was very thoughtful. He had a feeling that these attempts to rifle his possessions went a trifle further than just Christoff. Waldron's talk about Mark Drakma had impressed him much more than it had Don Powell. Hostile, resourceful forces had been set in motion against him, he was convinced. Forces that appreciated the value of this death-ray device of his far more than did Admiral Walsworth and the Navy Department, who had reluctantly and conditionally accepted it that day. He wondered if he should confide his suspicions to the admiral, probably to be laughed at. At least he would say nothing to Mary about the encounter with the man under the bed. She would be waiting. He must hurry.

And when he joined her a few minutes later, he was unruffled and smiling, and she suspected nothing.

Mary wove the runabout expertly and rather more swiftly than the law allowed through the crowded Washington traffic. Policemen have weaknesses for pretty ladies, particularly pretty, merry-faced young ladies who look at them with such appealing innocence when they raise grim warning hands. The two in the car were mostly silent, Mary intent upon her driving, Alan intent upon Mary. Soon they were in the quiet suburbs and then in the cooler, even quieter semi-countryside.

They lunched at a country club where Mary often played golf and tennis amid a gay, sunburned crowd of white-clad young people, a score of congressmen, a senator or two, and at least one Cabinet officer, whose attempted dignity and pompous courtesy to the stout woman who accompanied him did not fit well with the hot unkempt sack suit and straggly beard he was wearing. Mary nodded to several of her friends, but, luckily, Alan thought, they did not join the admiral's daughter and her handsome, if somewhat tired and pale-looking escort.

After luncheon they resumed their ride and, as if by mutual consent, turned off the well-traveled macadam on to a country road which they had explored before, and in another half-hour were in a shadowy sylvan wilderness. Here Alan took matters into his own hands and maneuvered his foot over upon the brake. Mary smiled and turned the car to the side of the road. To the right of them was a dark woods, cut through near the road by a swift little stream that raced and gurgled over the rocks. That was the only sound, except for the peeping and scolding of birds and the drone of a mowing machine in a distant hay-field.

They sat in silence for a moment, entranced by the peaceful scene, and then Alan reached over and took Mary's unprotesting hand.

"I didn't want to say anything until I saw where I was coming out," he said quietly. "But now that things seem fairly set at last—I guess you know, Mary, that I've been thinking a good deal about you these last few weeks."

Her face was stained a trifle pink, but she turned and, looking steadily at him, nodded.

"And what does that mean?" she asked, a little unsteadily.

"It means I love you," he answered, also a little unsteadily, "And I'm wondering if it could work both ways. Could it?"

Waiting for Mary's father's verdict on his invention was child's play compared with this crucial suspense.

"Both ways, Alan," she laughed, and lifted her red lips for his kiss.

The racing stream seemed to chatter more merrily than ever.

"And whatever the outcome of my experiments with the machine, we belong to each other, always?" he asked anxiously, finally releasing her lips, but keeping his arm tightly around her.

"Of course," she agreed.

"I hope you'll never have any cause to regret saying that," he said soberly. "I've reason to believe there are going to be some rocky times ahead for me. I may be in danger. I may even have to fight. But no harm will come to you. I'll see to that." And he took her in his arms and kissed her again. And though, feeling a vague fear, she asked him the real significance of what he had said, he would not explain and wished he had not even thus obscurely voiced his uneasiness.

After a while she intimated an uneasiness of her own when she remarked as lightly as possible, "Of course there's going to be a fearful row when I tell father."

"I suppose so," replied Alan, grimly. He had become vaguely acquainted with Admiral Walsworth's social ambitions for his daughter. He had become more definitely acquainted with the admiral's disapproval of him as a suitor.

"He can never forget he's a Walsworth," the girl explained. "He's so fearfully intent upon my marrying a title or a million! But I can manage him—never fear!"

Alan was certain, at that moment, that Mary could and would manage anybody about as deftly as she did her swift little runabout.

"Besides," she went on, "you're going to be famous, you know. A mere Embassy attache or an oil-millionaire will seem very tame and common compared with the world-famous inventor, Alan Holt."

"I hope so," he said, with a smile and a shrug of derogation. "But I'm not looking for fame and money out of this thing. My folks are Quakers, you know, and I've inherited a lot of their beliefs. I had the very deuce of a time getting my mother to consent to my enlisting when the war came along. I finally convinced her that it was the one war that was right, the war to end war. Well, it didn't do that. But if my invention works, I'm firmly of the opinion it will make future wars simply impossible. And that's why I've devoted two years to it and am going through with it now."

She patted his hand. "You just leave this particular little war with my father up to me," she said, with a belligerent toss of her bobbed head.

THOUGH Washington is the favorite resort of American tourists and sight-seers, there is no city in the world which contains so much that does not meet the eye, not only the casual eye of the visitor but also the experienced eye of the oldest inhabitant, and even the shrewdly trained eye of the Secret Service itself. But if the last-named agency has failed to see, it is not because its operatives have neglected to look.

In Washington there is, of course, the personnel of government, the impressive administrative array headed by the president and ranging through Cabinet, senators and congressmen down the line. The movements of all these are like so many open books. They court publicity, with considerable success. There are, as well, the representatives of foreign governments. These, too, bask in the limelight and on the front pages of our newspapers. Their movements in the dark are few, far fewer than generally believed. There are the ordinary citizens of the capital city, voteless, for the most part working for the government short hours and on short pay, possessing slightly less energy and initiative than the privates in the army of business in other cities, but otherwise quite typical urban American products. And if the events of their, for the most part, eventless lives are not broadcast through press and camera, it is because they are not deemed of sufficient importance rather than because there is anything recondite about them.

But there is a fourth and more interesting stratum of life in Washington—that consisting of the workers in the dark.

Once in a blue moon there is an unusually penetrating government investigation and the curtain of mystery is slightly lifted. It reveals a midnight conference in the obscure but luxurious apartment of a beautiful woman, involving persons whose normal doings are sufficient to command head-lines in any newspaper in the land. It discloses a hundred-thousand-dollar bribe toted about in a suit-case by a millionaire's son and deposited secretly in a pocket where it will make the millionaire a multi-millionaire. It brings to light a corps of highly paid lobbyists conniving at stealing a fortune belonging to the people of America. It divulges knavery and thwarted knavery, illicit business and illicit love, thrilling mystery.

A prominent Washington hostess, who would promptly toss herself into the Potomac at the slightest breath of scandal involving her name, discovers that the count she has been making a lion of is a viper unawares, and, what is even worse, not even a count. An important diplomatic code is missing, and a bogus operative of the Secret Service is quietly handcuffed at his desk and transported across burning Kansas to Leavenworth while his erstwhile and authentic associates are despatched to the ends of the earth for the vanished document.

Yes, the most interesting people in Washington are the workers in the dark. They are of either sex, and they are of all nationalities and social positions.

On the same day that he had made the arrangement to have Alan Holt enter the employ of the Navy Department, Admiral Walsworth arrived at the door of his suite at the Hotel Selfridge about six o'clock in the evening. He was tired and warm, and the immediate prospect was for a cooling shower and, later, dinner alone, for Mary was otherwise engaged.

The admiral had drawn his key from his pocket when he found, to his surprise, that his door was already slightly ajar. He stood stock-still for a second. He was quite sure he had locked the door that morning. Then, deciding that some employee of the hotel must have entered the room duty-bound, he pushed the door farther open and went in.

There was a slight gasp from within, quickly suppressed, and answered by a suppressed gasp from the admiral. A tall, dark, strikingly beautiful woman attired in a tight-fitting and singularly becoming henna gown, with cloche hat to match, stood in the small foyer hall and was regarding him with lustrous black eyes wide with apprehension. Admiral Walsworth automatically removed his cap and awaited developments. No ordinary intruder this. She was too attractive, too distinguished-looking, and the Walsworths had always had an eye for a beautiful woman.

"Oh, I beg pardon," hesitated the Lady in Henna in a deep rich voice. "This then is not the apartment of Yvonne Delgarde?"

A foreigner, he decided—French, probably.

"Madame is in the wrong room?" suggested the admiral, a far different admiral from the brusk, almost surly bureaucrat who had confronted Alan; a polite, almost obsequious and somewhat solicitous admiral.

"I was to have dinner with my cousin, Yvonne Delgarde," explained the strange lady in a rush of words to her full scarlet lips, and she came closer. "I was to meet her in the lobby. I waited—hours. Then I telephoned to her room—Room 33 they told me at the desk. A voice said, 'Come up, Claire.' I come. I find the door open, so I walk in. But Yvonne is not here. Then you come. I do not understand."

The admiral smiled.

"This is Room 23," he explained patiently. "You should have gone up another floor."

"Oh—how stupid of me," she said, apparently overcome with embarrassment. "Do you then know that 33 is the room of Yvonne Delgarde?"

"I have never heard of the lady," replied Admiral Walsworth. "But there are many others I've not had the honor of meeting."

"Yes?" absently agreed the attractive stranger, moving slowly toward the door. But she was smiling at him. "I shall go and seek her."

The Navy man was stroking his stubby mustache. He was meditating, at the same time, on how well henna-colored fabric went with lustrous eyes, especially lustrous brown-black eyes.

"Why don't you telephone Room 33 from here and see if your cousin is in," he suggested, pointing to the instrument on the stand just inside the living-room of his suite.

"If it is not too much trouble," she agreed, and turned and sank gracefully into the chair by the telephone. She jiggled the instrument and spoke briefly into it.

"She does not answer," the stranger smiled up at the admiral and replaced the telephone-receiver. "Oh, dear—it is ver' annoying."

Whereupon the officer participated in her pain over such a disappointment.

"I should esteem it a great pleasure if you would have dinner with me," he finally ventured, with his courtliest of bows.

The lovely lady rose, puckered her white forehead a little, and her slim hands went up to her bosom in a foreign gesture of surprise. But she smiled.

"I could not do that, I am afraid," she replied doubtfully. But her hesitation carried the implication that she would like to accept his invitation. And this gave him courage to renew it.

She studied him for a full moment, with her meditative and lustrous eyes. Then, with a little laugh, she yielded.

"It is terribly unconventional. And I do not know what my cousin will say when she comes. But you have been so nice—I will meet you in the lobby." And she left quickly.

Twenty minutes later, bathed and in a fresh uniform and feeling very well pleased with himself, Admiral Walsworth gave his arm to his vivid new acquaintance in the lobby of the Selfridge and escorted her out to a taxi-cab. If he set a rather rapid pace during their transit to the door and glanced once surreptitiously around the lobby to see how many people were observing his colorful companion and himself, it was only because he was an admiral and the soul of discretion and was very well known at the Selfridge. For the same reason he had esteemed it better to dine at a larger hostelry where they would not be so conspicuous. Not that this lady was not a perfect lady. But her high color, her rather bold black eyes, the caressing manner in which she smiled at him—one must be discreet.

Over the demi-tasse in the great, over-ornamented dining-room of the New Hilliard, Claire Lacasse said, fondling her own perfumed cigarette and rolling the smoke upon her lips, "I hav' always liked Naval men. Admiral Walsworth. My husban' was commander of a French destroyer sunk and killed by a Boche sousmarin off Madagascar. It was ver' sad. W e were just married. I came to America to forget."

The carefully plucked black lashes drooped, but in the next moment the late Commander Lacasse, if he ever existed, was forgotten and the conversation became more animated than ever.

Admiral Walsworth always said that it took a strikingly attractive woman to bring his social graces to their suavest point. His late wife, Mary's mother, a boyhood sweetheart whom he had married immediately upon graduation from Annapolis, had died two years after their marriage while he was on duty on an antiquated gunboat on a muddy Chinese river, leaving their year-old child to be brought up by her unmarried sister. Mary's mother had been a pretty, patient, mouse-like creature. During the few months of their married life that they had been together, she had worshiped her good-looking, rather dictatorial young husband flushed with his Academy honors, and accepted his word as law without question. He had loved her, but he had even then loved himself more and it had not been difficult, except upon rare occasions, to forget her. Mary had inherited her mother's looks and sweetness, but the positive qualities in her character came from him.

From the New Hilliard, an hour later, the admiral, after a brief and not too vehement protest upon her part, piloted his alluring companion to another taxicab, which whisked them out of Washington, across the river, and into Virginia. Three miles into the country the taxi halted in front of what was apparently a rambling old southern mansion overlooking the Potomac and set in the midst of rather carelessly kept rolling lawns. But the interior belied the sedateness of the outside setting. The proper knock at the door, a low conversation with the attendant, and his approving nod were required for entrance. Once inside, the din of jazz smote the ear as the Naval man and his escort entered the smoke-filled dining-room, where some forty or more couples sat around tables laden with tinkling cool glasses filled with colored liquids. It was a resort much favored by gold-braided gentlemen and strikingly if somewhat boldly dressed ladies.

Claire Lacasse danced divinely, Admiral Walsworth discovered. He himself was of the opinion that he danced rather better than he really did. Between dances they sipped the forbidden liquids and conversed. Their acquaintance had ripened fast, and their talk was much more intimate than it had been within the chaste, dignified walls of the New Hilliard.

She braced her smooth chin upon slender arms and hands and, leaning invitingly toward him, encouraged him out of narrowed, slightly slanting black eyes to talk. The admiral was garrulous, somewhat flushed of face, and was having the unofficial time of his official life.

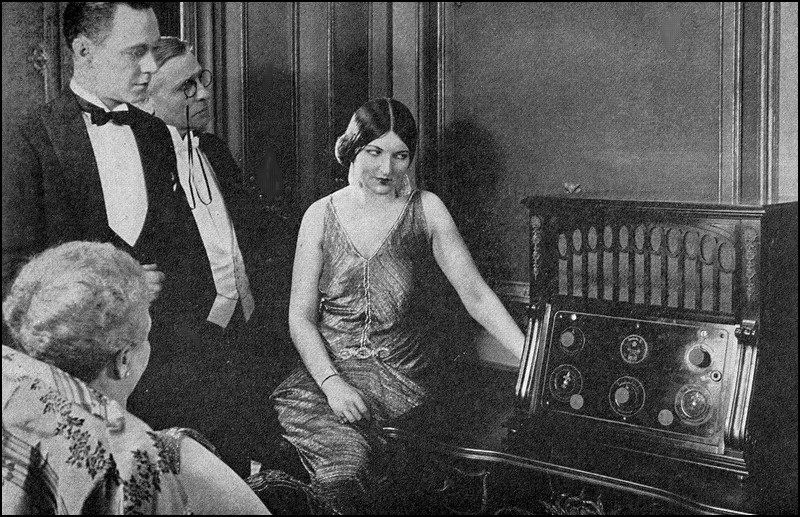

One of the features of the entertainment, provided while the orchestra rested, was the hodge-podge of music, comedy and bromidic monologue that proceeded from the loud-speaker pf a huge radio-set placed at one end of the room. The patrons of the resort, however, seemed to be interested in livelier and more personal forms of amusement. Only when the attendant at the radio tuned in on a western station and a simpering voice enunciating with exaggerated clarity started retailing bedtime stories about Percy Possum and Sally Skunk did the incongruity of the proceeding at such a time and place strike the audience's sense of the ridiculous, and loud cheers and laughter greeted that number.

Strangely enough, Admiral Walsworth's companion manifested considerable interest in radio.

"It is a ver' wonderful thing," she declared, and the admiral, for all the avidity with which he had been drinking in her every gesture, missed the shrewdly calculating look she shot at him. "And now I read," she went on, "in the journals of the latest radio invention—the 'death-ray.' I have understood, Admiral, that you are expert in the radio. Tell me, is there anything of importance in the 'death-ray'? It would be such an awful thing to destroy whole cities and thousands of innocent people."

Ordinarily the admiral might have been on his guard at such a question. But the questioner, in this case, was a pretty woman. And in the roseate glow cast by what he had eaten and imbibed, his usually close tongue was a bit loosened.

"I always believed there was something in this 'death-ray' business," he asserted.

"And your government?" asked the lady with the lustrous eyes.

"You must regard it as confidential, but we are working on something of the sort in my Department now," acknowledged the other.

During the next ten minutes Admiral Walsworth made several attempts to turn the conversation to channels more personal than wireless and more suitable to the intimate occasion. He failed to notice the gentle pertinacity with which Madame Lacasse kept recurring to that subject. As he was helping her into a summoned taxi an hour later and the cool midnight air had cleared his head somewhat, he wondered for an instant just how much he had told her and if he had really been as indiscreet as all that. But he consoled himself with the thought that, like all pretty women, she would forget everything of a technical nature that he had imparted to her.

He dropped her in front of her home, a quiet little brownstone residence on a quiet little street. Turning shy and slightly coquettish, she dissuaded him from following her farther.

"This is such a quiet neighborhood. One must be careful of the appearances."

"But I shall see you again? I may call very soon?" he begged.

She hesitated. "You are a ver' nice man to have rescued me to-night, Admiral. Yes, I will dine with you again. And you may come to see me here, but I would prefer a third person present when you come. I am alone here, you see. My servant comes only by the day. I must be ver' careful."

His face expressed disappointment and surprise at her sudden retreat into propriety.

She noticed it.

"You have a daughter, did I not hear you say? Why do you not bring her?"

He did not fancy introducing Mary to this gorgeous creature. There would be too much to explain, and he had a feeling that Mary would not fancy Claire Lacasse. But he said, "Maybe I will," and then, deciding that under the circumstances it would be unwise to go through with the fonder good night he had anticipated, left her.

When the door had closed behind him, Madame Lacasse stood quite still in her lighted foyer hall and smiled to herself. It was not a nice smile. Her almond-tinted, almost Oriental face bore somehow a resemblance to a cobra that is about to strike. She had succeeded! He was so gullible! And his daughter—probably she was just like him, and she might prove of even greater value than the father.

The lady with the almond-tinted face went to the telephone and called a number, a private number.

Admiral Walsworth saw Claire Lacasse many times during the next few days, but it was a full week later that he induced Mary to accompany him to the French woman's house for tea.

Madame was charmingly dressed and mannered. She made a special effort to be nice to Mary, who, knowing her father's weakness for pictorially striking women, understood readily his acquaintance with this newest one, but did not quite apprehend why she, Mary, had been invited to spoil their tete-a-tete. She did not at the time connect her presence there with the turn the conversation took toward radio nor did she notice the adroit manner in which madame had manipulated their polite talk into that channel.

Their hostess seemed to have an intimate knowledge of Alan Holt's triangulating machine, a knowledge that was not consistent with the secrecy with which that device and its developments were supposed to be surrounded. Madame was aware, for instance, that a large tower and a smaller auxiliary tower had been constructed in the Piney Ridge section and the inventor installed there and already put to work. She appeared quite cognizant of the importance of the experiments under way. Moreover, Mary's ordinarily close-mouthed father was in no wise loath to impart still more knowledge. It made Mary uneasy.

Claire Lacasse turned to her and smiled in friendly fashion.

"You, of course, know about this terrible 'death-ray' invention, Miss Walsworth? I am so interested. My poor husband was expert in the French Navy in the wireless. He talked about it all the time. I had to learn much about the science in, what you call ? the self-defense."

"Yes, I know something about it. But it's supposed to be a secret, I rather thought," replied Mary, with a sharp glance at her father, which he completely missed or ignored.

"This Meester Holt, he must be a ver' remarkable young man," Claire continued.

"He is," Mary agreed.

"For a garage mechanic he is a very brainy chap," chimed in the admiral, and this time he returned Mary's sharp glance. Madame missed nothing. She was alert—and amused. So, the daughter liked this Holt and the father disapproved. Bien!

"Some time, if it is permitted," Madame suggested cautiously and in the manner of an innocent girl asking her father to take her to the circus, "I should like to visit the towers and see this awful thing. I should be so thrilled."

Mary almost gasped. This French woman certainly possessed her due amount of nerve.

Even the Admiral was taken aback, cautiously as his hostess's request had been worded.

"I am afraid that would be impossible," he said, almost apologetically. "These experiments are being conducted in strict secrecy, and I must ask you on your word of honor not to tell a soul that I have even mentioned them to you. As for visiting the station, there are only about five people in the world permitted to do that. It's under strict guard."

"Not even Miss Walsworth is permitted?" asked the French woman, and Mary wondered if the look Claire flashed at her was not slightly malicious. Had the admiral confided to this woman the friendship between Alan and herself? Her father must be very deeply infatuated.

"Certainly not," replied Admiral Walsworth, and Mary comprehended that this was intended for her as well as Claire.

On their way home in the runabout, the Admiral asked, "Well, how do you like her?"

"Not a great deal," Mary answered, indifferently.

"But isn't she strikingly beautiful?"

"Oh, yes."

At dinner that evening at the Selfridge, Mary said seriously to her father. "Dad, I suppose it's rather impertinent for me to say this, but I wish you'd be more careful in what you tell Madame Lacasse about Alan's work. She seemed abnormally keen to find out about it. Has it occurred to you to be at all suspicious of her?"

"Nonsense," snapped the admiral, and bristled so fiercely that Mary considered it wise to drop the subject.

TO outward appearances there could not be the slightest aspersion cast upon the legitimacy of the manifold and bustling activities carried on by the firm of Drakma and Company in their palatial suite of offices on the sixth floor of a Washington business building rivaling the finest of the government edifices in its concrete-and-marble architectural perfection. One stepped out of the velvety-running elevator beside a desk labeled "Information" and presided over by a dignified, white-haired old gentleman who looked as if he had once been at least a senator. A muffled buzz issued from the four lines of clerks and typists stretching back toward the executive offices in the rear of the suite near the great plate-glass windows.

If such information was necessary, the dignified old gentleman or any of the clerks or typists could have told you with considerable pride that Drakma and Company owned outright and operated some ten large sugar and tobacco plantations in the West Indies, financed many other plantations and kindred enterprises on a profit-sharing basis, exported and imported many millions of dollars' worth of commodities annually in their own steamers and sailing vessels, had recently acquired two extremely prolific oil wells in Mexico and another in Baku, and were indeed the capital city's largest business concern. If you expressed surprise that such a business was located in Washington instead of New York, the logical center, the old gentleman or the young clerk would either have bristled with local pride or ventured the belief that their president, Mark Drakma, was rumored to be interested, in some obscure manner, in politics.

That was everything the old gentleman and the clerks and all but very few other living people knew about the machinations of Mark Drakma and the maze of wires, overhead and underground, that centered in his elaborately manicured fingers.

True, there was the matter of the slim dark lady with the black flashing pools of eyes, the always fashionably attired, always in-a-hurry lady who even now opened the little swinging gate behind which the distinguished old sentinel was stationed and swept down the aisle of clerks to the office of Mark Drakma, with her smooth chin in the air and without a look to right or left. The old gentleman's professional smile of greeting died on his thin white lips and was reborn as a quizzical frown directed at the shapely back of the visitor. The orders from Mr. Drakma were to admit the lady always without question, and his employer was a man who was always obeyed in the same manner.

The lady opened the door upon the spacious, thickly carpeted office with the shades of the oversized windows pulled against the sun so that the room was many degrees cooler than the blazing Washington June afternoon outside. A few original paintings in eminently good taste ., adorned the wall, and a few pieces of commodiously upholstered furniture tempted the business wayfarer to rest a while. But, like all wise executives, Mark Drakma had for his personal callers a very hard, plain chair beside his desk, a chair that said politely, "Business only. And please hurry." The desk of Drakma, in the coolest corner of the room, was low, glass-topped, and very broad, and its shiny top surface was practically empty. In the next coolest corner was what looked like the juvenile offspring of the great Drakma desk. This was where Drakma's homely, close-lipped secretary did her work. Miss Cooley was a being apart from the other employees of Drakma and Company, by request of her employer.

The heavy-set man with the thick jowls and small dark eyes was dressed immaculately in black. Except for the red rose in his buttonhole, he resembled a somewhat sinister undertaker whose clientele consists exclusively of millionaires. He was setting down figures on an under-sized memorandum pad and scowling slightly, but his bull-like head shot up with amazing speed for such a sluggish-looking body as the door opened and the mysterious lady entered.

"Ah, Claire," he said with genuine pleasure. His heavy body even rose solicitously at her approach.

Claire Lacasse made a careless gesture of greeting with her slim fingers and, without waiting for his assistance, pulled the smallest of the upholstered chairs up to his desk, ignoring the uncomfortable chair that was already there.

Mark Drakma's manner changed. His eyes narrowed and he said briefly, "Well?"