RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

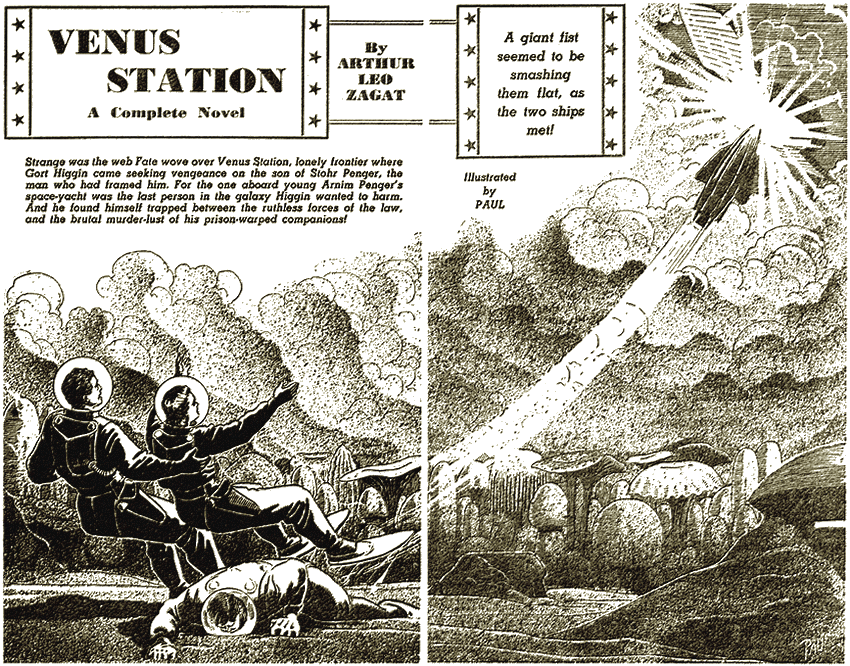

Science Fiction Stories, April 1943, with "Venus Station"

A giant fist seemed to be smashing the flat, as the two ships met!

Strange was the web Fate wove over Venus Station, lonely frontier where Gort Higgin came seeking vengeance on the son of Stohr Penger, the man who had framed him. For the one aboard young Arnim Penger's space-yacht was the last person in the galaxy Higgin wanted to harm. And he found himself trapped between the ruthless forces of the law and the brutal murder-lust of his prison-warped companions.

A SUDDEN metallic chatter, from the space-radio set, whirled Darl Rand to it. As he picked up the thin tape of magnetic alloy that flowed out of the set's side, Chris Haldane shoved up from the edge of his bunk and walked softly toward Darl.

"It's an all-station flash from the Interplanetary Control Board," Darl said.

"More grief, I'll bet."

Down the center of the gleaming tape a lustreless, wavering line was traced. To the uninitiated it would seem a mere flaw in the foil, but for the two staring at it every jog and dip was a letter formed by etheric impulses that had traveled some thirty million miles from their home planet, Q de I C B. That demanded instant attention from Earth's far-flung colonies, from all her spawn of space-ships weaving their web of commerce across the trackless void. Then; All ships and stations are warned to be on guard against—

Abruptly the teletape stopped moving, hung limp from the silent machine. In the hush, Haldane was suddenly aware of the incessant low burr of the motors that maintained within these windowless dural walls an approximation of terrestrial climate. Rand cursed under his breath, flicked open an inch-square slide in the instrument's side.

In the niche thus revealed, a miniature filament glowed steadily. "Circuits are okay," Darl grunted. "It's 'Nick' all right."

'Nick' was their private abbreviation of the polysyllabic label by which the Physicians tagged, but did not explain, the curious ionic disturbance that intermittently isolates Venus from all communication with the rest of the System. "Wonder what they're fussed about."

Till it lifted as, unpredictably as it had closed down, they were as effectually cut off as if the miracle of the Tau wave had never been discovered. "Magnetic Hurricane, d'you think?"

"I don't think so," Rand replied. "But if it is, young Arnim Penger's going to have something to worry about."

"Him and that space-yacht of his," Chris frowned.

"Just what will give if we tell those insects to go skim their own gliders?"

Rand shrugged. "Maybe nothing. Or maybe we'll find ourselves shifted to some stinking rock in the Asteroid Belt."

"I don't believe it! I don't believe even old man Stohr Penger would dare shunt you after you've upped the banta output seventeen per cent in the four years you've run Venus station, an' kept th' Weenies peaceful as Jupiter pups in th' bargain. He may be the Big Cheese of T.D.S., but he's still accountable to th' Board for how he runs th' concessions, an' they have a way of askin' embarassin' questions."

"Yes." Lines traced by wind and weather deepened in Rand's leathery countenance. "The I.C.B. has a way of asking questions. But Penger has his own way of answering them."

His calloused hands closed into fists at his sides. "Ever hear of a man named Gort Higgin, Chris?"

"Higgin? Isn't he th' traitor who was caught red-handed plottin' to hand over this very Station to Mars Interstellar?"

"The letter to Rustorn of Mitco that convicted him was forged. The perjured spaceman who swore to it did turn over a letter to Stohr Penger—a letter from Gort to Penger's wife, Coralee.

"Higgin was my friend, Chris. He told me the real story when they let me see him before they shipped him off to the Moon. And now Coralee Penger is dead, and the perjurer is floating somewhere in Space, his ship pithed by a meteorite. And Gort Higgin must be dead, too—or driven stark, raving mad by what they do to men in that pit of Hell called the Lunar Penal Colony."

Rand's lips twisted into a bitter grin, "If you spill a word of it to anyone, Chris Haldane, I shall most certainly break your neck. And now," he gestured to the clock that kept track of Earth-time for them, "get moving. You're due out to relieve young Fran."

"Okay, but you don't have to go official on me." He started across to the lockers on the other side of the austere room, flat muscles sliding under tawny akin. "Say! If that Penger party's got any females in it, I'm hidin' out till they leave."

His Chief didn't answer. Haldane shrugged, pulled on hip-boots of shiny black neoprene, stamped his feet down and buckled them about his waist. Rand stirred.

"Look, Chris," he said. "Soon as you take over from the kid, I want you to test the Curtain."

"Expect trouble?"

"No, the only reason I have is that my pet scar's itching." He thumbed the old ray burn that cut a purple swathe through the black hair matting his belly. "But I'd give a lot if 'Nick' had held off long enough to let the rest of that spacecast through."

AS Chris Haldane carefully shut the inner door of the Station Hut's entrance lock, oven heat started beads of sweat on his brow. From a shelf bracketed to one wall of the tiny foyer, he took a featherweight transparent globe and inserted his head into it. He zipped shut the hermetic closure to his coverall's neck, pulled a deep breath into his lungs, exhaled violently.

Then, satisfied, he twisted the latch of the outer door and went through.

He stopped short, gasping, realizing that he would never become wholly steeled to this first moment's contact with the world that lay around the Hut.

A dreamy, dim world it was, a world perpetually drowned in twilight. Literally drowned, for Venus' atmosphere is more water than air. This was as fair weather as the planet ever knows; a heavy drizzle sifted interminably down from a cloud-sky in which a Sun one-third again larger than Earth's glowed crimson. Out of the viscous, yellow mud a steamy fog rose to receive it, rose, swirled and eddied around half-seen shadow-shapes peopling the Compound. Closing them in was the encompassing loom of the jungle.

Chris stood motionless, peering into the obscurant mists, swearing softly to himself.

Fran Mellton should be here, eager for relief from his eight-hour tour of duty. Where—One of the shapes, magnified to spectral enormity by the fog, was moving this way—but its course changed. It was not Fran.

"Where the blazes is that cub?" Haldane muttered. He lipped between his teeth an inch-long metal tube that penetrated the helmet's surface in a tiny valved orifice, blew into this breath deftly controlled by his tongue-tip. No sound resulted that would be perceptible to the unaided Terrestrial ear, but the blurred shape veered again and came toward him.

It dwindled as its outlines firmed, becoming more nearly Haldane's own size. He heard the slop, slop of enormously splayed, webbed feet in the mud, discerned spindly, jointless legs, a pigeon-breasted torso whose dark, turtle-like skin dripped moisture, a head topped by a pointed and hairless scalp.

"Seewee, Toom," Chris made his whistle emit the greeting of one equal to another. "Seewee leet." The Venusian who halted before him acted as a sort of foreman over the workers in the Compound but among his own people he was a king and very proud.

"Seewee leet, Beess Haldane."

Toom's countenance, all great, goggling eyes and vast crescent mouth, was incapable of expression, but the striated gill-flaps that formed its cheeks pulsed in rhythm that betokened pleasure. "Leet seewee." The helmet's filter-membranes lowered Toom's voice a full octave but it was still painfully shrill.

"I am looking for Beess Mellton," Haldane used the whistle to tell him in his own language. "Have you seen him?"

"He has gone into the gweelen. Alone."

"Alone into the jungle!" This was against the strictest of the Station's rules. "How long ago was that?"

"Two reeleh." A little more than half an hour. "I wished to send Gree with him, but he refused. He had to do a very important thing, no doubt, and one that must not be known to us."

That was, Haldane knew, the nearest the Venusian would permit himself to unfavorable comment on a Terrestrian's acts.

"No doubt," he agreed, "but it should not have taken him more than one reeleh. It would perhaps be wise if we go and search for him."

"Eem. Beess." If Toom had considered Chris above him, he would have said, 'mee,' which means 'I obey you.' "I shall take Gree and search for Beess Mellton,"

"I'll go along."

THE extended soles of Haldane's boots carried him snowshoe-like over the quivering mud toward vague bulks that became huge piles of banta fibre awaiting baling and shipment to Earth. It was the rest period; only two or three Weenies were in evidence here, but Toom, halting, called one of them to him.

Gree was shorter than his chieftain, his tough skin lighter in hue, but he was just as innocent of any shred of clothing. Haldane had long ago got over any notion that this habitual nudeness stigmatised the Venusians as aboriginal. They were, in fact, infinitely more civilised than the fur-swathed dog-men of Jupiter. Their kreels, as they called their towns, were clean and orderly; their social organization highly complex; their laws stringently obeyed. Since the Venusian temperature never dropped below ninety, even during its two-Earthweek long night, and her people are monosexual, neither comfort nor modesty required them to cover themselves.

"Mee," Gree shrilled in acknowledgment of the king's inaudible order, and darted off in the mists. Toom's boneless fingers tugged at Haldane's sleeve. "Come, Beess. He will meet us where Beess Mellton went into the gweelen."

As they went on, the fog seemed to darken ahead of them. Chris spied a coppery gleam high overhead—the dripping, horizontal wires of the Curtain that encircled the Compound. Then he was at the edge of the jungle.

The Terrestrians call it that out of habit, but the gweelen is no such jungle as was ever seen on Earth. There were no trees, no looping vines, no rustling leaves. Immense fungi towered fifty, seventy-five, a hundred feet into the steaming air, trunks and thick branches grotesquely contorted. Instead of foliage there were the fringed umbrellas of monstrous toadstools; instead of underbrush, coiled, pallid stems and crumpled clumps of membranous stuff resembling diseased seaweed.

The colors of the gweelen were orange and purple, a sickly white and the gray-yellow of corruption, but never green. And in the gweelen a thick silence brooded always, relieved only by the eternal drip of moisture from its dark roof.

Gree appeared out of the haze. A cord of twisted banta now suspended from his neck—a two-foot, hollow cylinder out of the open top of which protruded the gum-blackened sharp points of a half-dozen throw-sticks. He handed a second, similar quiver to Toom, and then they were on the move again.

The Earthman could not make out how the natives knew which way Fran had gone. Not that the kid was an expert woodsman or had taken pains to conceal his route. It was the gweelen itself that had obliterated the traces of his passage. The stump of a branch Chris broke off in passing was sending out a new tentacle almost before the fragment reached the ground; a spore-ball burst and its spill of black dust turned scarlet at once with cilia of new growth to blot out his footmarks.

The light faded to a lurid semi-darkness. The Weenies went swiftly and Chris could only follow them. There was no sound save the soft thud of his own boots and the incessant patter of rain, and the three from the Station were the only sentient beings in this obscurity.

Then two! Abruptly there was only Toom, five paces ahead. Gree had silently vanished.

Before Haldane could get his whistle between his teeth, the remaining Venusian was concealed by a huge yellow bole. Chris shoved past this, was confronted by a clearing whose ground was clotted by a black-and-gray spotted low thicket of something resembling kelp.

Toom, too, had disappeared. Chris Haldane was alone in the gweelen.

Not quite alone. A vagrant beam of light glinted on vitrolene, deep in that thicket. It was the curved surface of a helmet, and the splotched, dark mass sprawled beneath it had a grim travesty of human shape.

Toom had kept his word. He'd found the cub of Venus Station. But—

Chris dropped flat! Through the space where he'd been, something whizzed, thudded into the yellow bole. Most of it was buried in the tough fungus, but the part that still protruded was the quivering shaft of a Venusian's poison-tipped throw-stick.

IN that same spurt of motion Chris Haldane had rolled under an eavelike excresence circling the saffron trunk a half-yard up from his base. He was shielded now from behind and above. "Nice," he muttered. "Lovely." Then his brow furrowed.

He'd realized, abruptly, that he'd not ducked down out of the throw-stick's path because of anything he'd heard or seen, even subconsciously. That he'd been thrown down by—by something not physical at all—as if some unseen guardian had tripped him to save him from the death that had taken Fran Mellton. Peering through the splotched kelp, Chris could make out the butt of a poison-tipped dart sticking out of the still, dark shape. Fran had walked into a trap; he, Haldane, was caught now; and Darl—sooner or later he would be lured out here to his death!

Chris's muscles tautened as an ear-piercing scream froze him!

Out there where it had come from, a slender, bluish stalk shook as though something had crashed violently into it. It split across, halfway up, and toppled. A shadow darted toward Haldane, met a dark form swooping down from above.

Toom's spindly legs bent to spring his weight as he landed. "Come out, Beess Haldane," he piped. "Safe now to come out,"

Chris expelled held breath. This might be a ruse, but if it were, cowering under the fungoid eave would merely delay the inevitable. "Safe now," the Venusian repeated. "There was only one."

Haldane pushed himself into the open, lifted erect. Poker-faced, he demanded, "Only one what?"

Toom pointed to where Gree looked down at something sprawled among the blue stalk's smashed fragments. The motionless body of another Venusian, smaller than any Chris had ever met with, lay there. The top of his skull was less definitely pointed; his limbs and torso were differently proportioned.

"A Neelah," Toom piped. "Of the people who live beyond the Great Hole."

VENUS is almost as large as Earth, but while Terra's seas cover nearly three-fourths of her surface, that of her sister planet is virtually all water. Only the one small patch of land on which Venus Station has been established rises above the steamy flood, an irregular circle some three hundred miles in diameter. The "Great Hole" to which Toom referred is an immensely deep canyon that cleaves almost completely across this island, about a hundred miles from the T.D.S. Compound.

"He's pretty far from home," Chris grunted,

"Yes, Beess," the Venusian agreed. "This is the only Neeleh that in my remembering has ever crossed to our gweelen."

"That's the second time you've said there's only one. What makes you so sure?"

The tiny orifices that served the Venusian for nostrils quivered. "If there were another near, we should smell him as we smelled this one."

"You smelled—So that is why Gree left the trail!"

"Yes, Beess, but we dared not speak aloud to warn you lest we also warn him that he was discovered. Gree made a circuit to come on him from behind—"

"While we held his attention. A good plan, Toom. But if I had not tripped just at that instant I would be as dead now as he is,"

"I did not forget, Beess Haldane, that you trusted yourself to me," Toom said with simple dignity. "Your escape was not a thing that happened without my will."

Haldane stared. "You! How did you throw me without being anywhere within reach of me?"

"How do your little black sticks, held in the hand, burn to nothingness a man or beast as far as one can see? How do you talk to the land in the sky from where you come? May not we have a knowledge, too, that is beyond your understanding?"

"You win," Chris grinned wryly. "Have you a knowledge, perhaps, that tells you what brought this Neeleh here?"

The other's gills pulsed thoughtfully. "That I have not. There was a war between us and the Neeleh once, but in the time of my father's father it was agreed that they should keep to their gweelen and we to ours; since then there has been peace. It is very strange that one of them should come now to hunt us or our friends."

"Tee Toom," Gree put in. "If I may speak?"

"Speak, son. What are thy thoughts?"

"These, my tee. When I came upon the Neeleh, he seemed not like one who hunts, but like one who is hunted and kills to save himself. There was no fierceness about him, only terror."

"Who would hunt him?—Neelah!" Toom stiffened, looked up at the jungle roof, above which the almost imperceptible vibration that had cut him off deepened to a distant thunder. "A typheen!"

"No, Toom." This, at least, was something Chris knew about. "It is not a storm. It is only a ship from our land beyond the sky." Arnim Penger's yacht, of course, entering the stratosphere to begin the descending circuit, about the planet, with which a space-pilot thirsty of fuel slows his craft to a speed safe for landing. "See. The thunder has ended already. Now we'd better carry Bees Mellton's body back to the Compound and do our talking there."

"Eem, Beess Mellton," the Weenie agreed. "Beess Rand is very wise in these matters. He will solve the riddle."

BUT Darl Rand had no more idea what it was about than they,

"Except that what Gree said about the way he acted it sounds as if this Neeleh were spying on the Compound," he mused. "He was caught at it by Fran and killed the cub to silence him."

Chris blinked. "Why should anyone spy on us? Mitco made peace long ago an' there's no other outfit buckin' T.D.S."

"Something's starting, Chris, out there in the jungle. I don't know what, but till I find out I'm closing down the Station."

He turned to Toom, "Veed tee," he whistled. "Friend king, I ask that you take all your people to your kreel, or at least out of the Compound."

The Venusian's gills pulsed once, stilled. "You do not trust us, Beess Rand?"

"I trust you and yours, veed tee, as I trust Beess Haldane here, but trouble threatens us and there is no need that you share it. Within our Curtain we shall be safe, and you in your kreel. That is best for all of us."

For a long moment Toom faced him, silent, motionless. Then, "Eem, Beess Rand. It shall be as you wish. Before a reeleh has passed the Compound shall be empty of me and mine."

He glided off, Gree following. "There goes four years' work," Haldane grunted. "You'll never trade another ounce of banta with Toom or his Weenies."

"Maybe not, but you know what the Regulations provide in a case like this. 'If hostilities with natives appear imminent, all Station grounds must at once be cleared of any but Syndicate personnel.'"

"Is that what it says?" Chris drawled, the taut lines about his mouth easing. "That gives me an idea. Penger an' his friends aren't Syndicate personnel, are they?"

"Got you." Darl chuckled. Death, however sudden or gruesome, is a hazard of the Outworlder's trade. If it comes—well, no one can live forever; it must be taken in stride. So Rand shut out of his mind the fungus-marred young body in the storage shed.

"'Nick's' still on, but they must be beneath it by now. We'll go in and break the bad news to them. But first we're switching on the Curtain."

They went around the corner of the Hut, slopped through mud to the entrance lock. Set into the wall beside its door was a frosted vitrolene screen, man-high and twice as wide. In its dural frame was a vertical row of pushbuttons, two white, the top one scarlet.

Darl thumbed the central button and a faint zizzing underlay the drip, drip of drizzle.

The sound came from an octagonal structure of vitrolene and dural atop the Hut. As Haldane looked up at this, the sound deepened, became a low burr.

"Set," he reported.

There was a click under the ball of Chris's thumb, and the red button stayed deep in its socket as he turned his back on it. For an instant nothing happened, then a single red filament threaded the reddish haze, curving, twenty yards above the Station's border, left and right as far as he could see, A sudden shower spattered, out there, ceased almost at once. The mists cleared away for a space either side of the line. The gweelen, better defined, seemed to have closed in on them.

That was all, but Chris Haldane knew that Venus Station was encircled now by an invisible wall of force-stress through which no living being, no missile, could penetrate. Nevid Onegir's Electronic Curtain!

"That's that," he sighed. "Now let's get inside an' inform Mr. Arnim Penger we're not receivin' this p.m."

FREEDOM from his helmet's confinement, the clear air within the Hut, were grateful. "Try 'Nick' first," Darl called to him as he flapped towards the radio. "If it's lifted, we'll have to report through to Terra right away."

Chris got hold of the sending key, rapped it. Waited. Tried again. "No soap." he grunted. "It's still nickin' away full force. What's that call?"

Rand was already fluttering the pages of a Call Book. "Penger," he muttered. "M... O... Here it is. Penger, Arnim. Y-C, for Yacht Comet."

"Comet, huh?" Haldane's wrist flexed, sending; Y-C, Y-C, Y-C De V-S. "Wouldn't be any oxygen out of my tanks if it had a hyperbolic orbit an' skidded clear out of th' System—Oke! They've got me."

The teletape had chattered into movement, the hills and valleys of the line tracing its center crisp now, clear-cut. V-S. he read. The impulses forming them were coming from thousands, not millions, of miles away. V-S De Y-C. Go ahead.

"How'll I put it, Darl?"

"This way." The corners of Rand's mouth twitched. "Y-C from V-S. Regret inform you hostilities with natives developing, therefore am required by section one-three-two, paragraph 8, Regulations I.B.C. to forbid you to land on Venus. Rand. Chief, Venus Station."

"Here's more, Darl." Chris read from the tape. "Am landing your field estimated forty-five minutes from now. Despite your solicitude, have no choice because out of fuel. Penger, Yacht Comet."

Rand's blunt jaw ridged with knotting muscles. "Send him this, Haldane. Ready?"

"Ready."

"Y-C from Rand, V-S. You may land for emergency refuelling but must blast off as soon as completed. Will await you landing field to expedite operation."

By the time Haldane got the message off, Darl was already out of the Hut. Haldane got his helmet on and hurried after him, but didn't catch up with his chief until the latter had reached the towering tanks at the other end of the Compound.

Something in Rand's posture, as he stood spraddle-legged before the one whose green paint indicated that it held oxygen, brought a quick, "What's up?" from the other Earth-man. Darl didn't answer in words. He merely pointed to the gage at which he stared.

Chris Haldane's nostrils flared. The needle on that gage stood at zero. The tank was empty and the nozzle of its outlet pipe was white with hoar-frost to show that it had been emptied within the hour.

The grin he essayed didn't quite come off. "If Penger's tellin' the truth about bein' out of gas," he said softly, "We're goin' to have the Comet with us quite a while."

Darl Rand's voice, transposed by the filter-membranes, boomed in his ears. "Maybe that is precisely the idea."

"THIS," Chris Haldane said, "clears up one point, anyway. Evidently Fran heard or saw somethin' that tipped him off there was a prowler around, went off into the gweelen to tackle him, alone. But if you're right that the Neeleh gutted our oxygen to keep the Comet here, how'd he get wind she's comin'? More. Why, if they're workin' up an attack on th' Station, should they make sure there'll be extra Earthmen here to help us fight 'em off? It just don't make sense?"

Rand turned to him, sultry-eyed. "I've run into happenstances before, on the Out-Planets, that didn't seem to make sense. We're in for it, Chris."

"Well," Chris murmured. "We won't have long to wait. Here she comes."

He'd glimpsed a shadow drifting in the depths of the cloud-sky, a wraith more guessed at than seen. It darkened, broke through the glowering ceiling, was bathed by ruby light. Breath caught in Haldane's throat.

"Gad!" he whispered. "Is that somethin'!"

The rocket-tubes that had blasted her across thirty million miles of airless emptiness silent now, graceful wide wings unfolded out of a stellite hull that flamed crimson from bluntly-rounded nose to swallow-tailed stern, the space-yacht seemed fashioned from fire. Sentient, one felt her, endowed with a life not of Earth, nor of any other planet, but stemming out of the Sun direct, ultimate source of all life. Weary with the long journey that lay behind her and with infinite grace sinking to rest.

She just touched the mud of Venus Station at the end of a curve so nicely calculated, so deftly helmed, that with the last whisper of motion left to her she slid less than a hundred feet before she stopped—exactly in the center of the field.

"Beautiful!" was Darl Rand's grudging tribute.

A black circle, eight feet in diameter and flat at the bottom, traced itself on the yacht's flank. The section it demarked extruded itself from the stellite surface, swung slowly and ponderously aside on gargantuan hinges. In the aperture it had vacated, there appeared a figure bloated by a space-suit, its head a sphere similar to the Stationmen's helmets, save that it was composed of dural. Only its face-plate was vitrolene, so thick that the countenance within was a mere pallid blur.

"Which is Mr. Rand?" demanded a metallic, intonationless voice that issued from the chest of his apparition.

"I am." Darl stepped forward. "Who are you?"

"Penger. While your assistant refuels my ship, I wish you to send a message to Earth for me." Mechanical-sounding as it was, the voice held a stiff arrogance that brought a hot flush of resentment to Haldane's cheeks. "I seem to be able to raise no one but you on my own set. Something has apparently gone wrong with it."

"No, Mr. Penger," Rand drawled. "Nothing has gone wrong; no set will get a message off Venus as long as 'Nick' lasts."

"'Nick'?"

"The geoprismic devolution of the ionic balance of the troposphere, if you must know its full name. It cut us off, an hour or two ago, in the middle of an I.B.C spacecast whose full text I happen to be somewhat anxious to learn. May I see your teletape record, please?"

"I have none. I have been reading signals aurally."

"Then would you mind telling me what that flash said?"

"I wouldn't mind, Mr. Rand, if I had listened to it. Unfortunately, just as it began to come over, my main feed-line cut out, and since I was approaching your planet head-on at some ten miles per second, it seemed more advisable that I valve in the reserve tank to give me control. By the time I returned to the navigation cabin, the message had ended."

"I'll be—" Darl checked himself. "Look, mister," he resumed more calmly. "Didn't you realize that was a Q call from I C B? They're damned important. You didn't need more than one pair of hands to shunt a feed, did you?"

"No," Penger acknowledged. "But it happens that is all I possess."

"Are you trying to tell me that you flew from Earth alone? It can't be done!"

"So someone was rash enough to bet me, but it looks very much as if I've done it." A triumphant laugh grated from the 'phone concealed in the space-suit, mocking Darl's goggling eyes, Haldane's dropped jaw. "Since it appears that you can't radio confirmation, I shall want you to sign a written statement as to the day and time I landed here on Venus."

"Hold on." Chris was struck by a sudden thought. "Something's screwy here. T.D.S. Terra radioed us to prepare to receive Arnim Penger and a party of friends. What are you tryin' to put over on us?"

The dural helmet turned to him. "Nothing, Mr.—"

"Haldane's my name. Chris Haldane."

"I am putting nothing over on you, Mr. Haldane, as you will find if you inspect the Comet. The one I deceived was my father. He wouldn't have permitted me to make this little trip if he had suspected I intended to do it alone."

"If I know Stohr Penger, hell tan your bottom for even thinking of a fool stunt like that, when and if you get home," Darl growled.

"You see," he gestured to the green tank, "we've just learned that we're fresh out of oxygen. We can't refuel you till 'Nick' lifts and permits us to ask for a new supply so I rather imagine that you will be with us for quite awhile."

"No!" One of the steel-claws that served the space-suit for hands flew to the face-plate of the helmet in a curiously juvenile gesture of consternation. "I can't—I won't stay here."

"I'm afraid you have no choice," Darl clipped. "You can't fly a spaceship with empty tanks."

"I have some left. Maybe enough to blast me off into Space, from where I could radio Dad to have a tanker meet and refuel me on the fly." Penger whirled, vanished into the yacht's dark interior.

Rand stood motionless, gazing after him. "The damned brat," he growled.

"Yeah. But you've got to admit he's got guts—" Chris checked, turned towards the Compound's fog-veiled border, beyond the tanks.

"What's that?" he demanded, sharply. "What's that noise?"

THE sounds that came faintly to him from the depths of the gweelen would in a terrestrial countryside have been noticeable only by their absence. On this hushed planet they were startling.

"D'you hear it. Darl?"

"Yes."

It was a thin, shrill chorus such as the cicadas raise on an Earthly summer night; a myriad piping questions, a myriad tiny voices answering in uneven, runic rhythm. "What is it?" Chris asked again. "I've never heard anything like it on Venus."

"I have." There was a grimness in Rand's low response of which even the filter-membranes could not rob it. "When Gort Higgins and I were the cubs of the crew building this Station. Hearing it, we dropped our tools and grabbed for our Wellsen guns. It was the leeyas we heard, the war pipes of the Neeleh."

"But that was only twenty years ago," Haldane exclaimed. "Look. Was Toom kiddin' me when he said they haven't showed this side of the Great Hole since his grandfather's reign?"

"You forget that the Weenies mature when they're ten years old. Earth-years.

"Toom's grandfather was tee then, and since we hadn't set up the Curtain yet, if it weren't for the help he and his people gave us, we should all have been wiped out. Which would have been the best thing that could have happened to Gort Higgin and probably to the girl who became Coralee Penger."

"Don't tell me you had females with you."

"We had one, worse luck. Coralee's father's ship had been pithed by a meteorite and she was the only one who managed to escape from that wreck. We picked her up on our trip here, a couple hundred thousand miles out. Our craft remained here as a barracks for our work-party, so she had to stay here too. Gort fell for her hard and she—well, we thought she fell for him. But Stohr Penger came along on an inspection trip and took her to Earth with him. By the time Higgin wangled a furlough she was Penger's wife and a mother."

"Mr. Rand!" Penger's metallic voice interrupted. "Mr. Rand." He was back in the Comet's air-lock. "What's your velocity of escape here?"

Darl turned to him. "Barely less than Terra's, Mr. Penger. You'll have to hit better than six and a quarter miles per second to get free of Venus' gravity."

"There isn't enough left in the tanks to accelerate to anywhere near that,"

"That's too bad." Rand's intonation showed that his regret was altogether sincere. "I'm sorrier than you are, but now that's settled. We've wasted enough time fooling around out here. Come on, let's get started to the Hut."

The space-suited figure stiffened. "I shall be quite comfortable here in my ship, thank you. I shall remain in it until I can leave."

"Wrong," Despite the insect-like shrilling that rang menacingly in his ears, Chris couldn't help grinning as Rand's syllables got hard, clipped. "Get this straight, right now. Your father may be president of Trans-Earth Development Syndicate, but I am Chief of Venus Station and as long as you're within its boundaries you will obey my orders without argument or delay. Understand?"

"I understand that you are being intolerably officious," Penger snapped back. "You can have no reason for objecting—"

"I not only can, but do have. This Station is, or soon will be, under attack by hostile natives; I'm going to have enough on my mind without having to worry about your safety alone out here. You will either obey my orders without question or use what fuel you have left to remove your ship from this Compound. There is plenty of room outside of the Curtain, where I'll have no responsibility for you."

"But—But I—"

"Do you know what hostile Weenies will do to an Earthman they catch alone? Has your father ever told you what a corpse looks like, after they and the jungle get through with it?"

Penger shrank against the side of the lock. Even through his 'phone his tones were choked. "Ill do as you say."

"Very well. Get your skids on, or you'll bog down in this mud. Make it snappy."

PENGER ducked inside once more, reappeared almost at once, his feet now fitted with the wide extension soles with which every space-suit is provided against the need for travel on the depthless snows of Jupiter Dr Mercury's half-molten lava. He jumped down. The three started off across the morass.

They did not speak, but the sound of the leeyas followed them and it seemed to Chris that it was perceptibly nearer. He glanced gratefully at the high red glow the wires traced against the jungle's ominous dark loom and tried to imagine what it must have been like here before the Curtain was up, listening to that shrill antiphonic threat close in. The Hut took form in the fog and then they were tramping into its entrance lock.

Darl closed the outer door. The fluortube came on to light up the cramped vestibule. "You can shuck out of that helmet now," Haldane told their unwelcome visitor, "and get some clean air into your lungs."

Unzipping his own headgear, he turned to lift it off and put it in its place on the shelf. A choked exclamation from Rand brought him around again.

Where the dural spheroid had been, he gaped now at a shock of ringlets black as the void of Interspace, the pale oval of a face across the bridge of whose tip-tilted little nose a handful of freckles was dusted and long-lashed gray eyes that met his with a sort of fear-filled challenge.

Darl's hoarse voice inanely stated the obvious. "You—you're not Arnim Penger."

"No. I'm Laola Penger."

CHRIS turned to the lock-door as Rand entered, his coverall dripping. "What's new, Darl?"

"Nothing." He pulled from his shoulder strap that slung to it a rectangular black box. "Funny thing, though. The gweelen's swarming with Neeleh, but not one showed near enough the Curtain for the Kappa beam to spot." He started to unbuckle the belt in which his Wellsen was holstered. "I can't make out why they haven't tried to come through, even once. They can't see it, and they shouldn't know about it, since we drove 'em back across the Great Hole before it was installed."

"Do you think our own Weenies could have tipped them off?"

"That's what it looks like, though I hate to think Toom's in cahoots with them. Well, whatever the answer is, you'd better get out there and start your sentry-go."

"Right!" Chris thrust his own Wellsen into its scabbard, sat down to pull on his boots. "You look dead-beat, fellah. You better take yourself a snooze."

"That's precisely what I intend to do, if Miss Penger will retreat into her cubby and give me a chance to dry off." He turned to the girl. "Can I rely on you to get me up the instant you get a buzz from Chris?"

Her fingers tightened on the tarpaulin to which she had retreated. "I'm not quite an imbecile, Mr. Rand." She jerked the canvas folds together in front of her, but from behind them came something very much like a stifled sob.

Darl looked dismayed but Chris chuckled, picking up his gun-belt and the black box as he rose. "Now you've gone an' hurt her feelin's," he drawled, ambling toward the exit. "You ought t' be more careful, y'know."

Rand caught up with him, put a hand on his arm. "Watch yourself, lad," he said, low-toned. "Looks and cute little ways—that gal's the image of Coralee Penger."

"But I'm no Gort Higgin," Haldane grinned. "Don't worry, she could be a Weenie for all the heart-throb she gives me. I'll buzz you if anything turns up."

"Do that, and be careful of your footing, guy. It's gotten pretty sloppy out."

"Sloppy" was a euphemism. The drizzle, through which Chris had started out on his search for Fran Mellton, had become a heavy downpour that made of the Compound a lake inch-deep in yellow, muddied water. The cloud canopy had lowered till it seemed to rest on top of the Hut, and the ruddy glow of Venus' days-long sunset had given place to a leaden dusk.

The sun itself, in the twenty hours since the Comet's landing, had lowered until, a gigantic, dull orb scarcely discernible, it silhouetted the tallest of the gweelen's macabre growths. Within the jungle the leeyas screeched, shrill and unending, defying sun and the pounding drum of the rain, menacing the aliens who'd dared to trespass on the planet.

CHRIS stopped short in his tracks, fingers closing on the butt of his Wellsen.

The shadow he was not quite sure he'd glimpsed in the torrential downpour darkened, and a thin, far-off cry pierced his helmet. "Beess," It broke into words. "Come quick, Beess!" A Venusian's shrill plea for help! "Quick, Beess, quick."

Chris threw a glance at the visiscreen, fixed in his mind the point on the Compound's margin where a light-spot bad suddenly bloomed, was off toward it on the run. His right hand drew his gun as he went, his left went to the black box slung from his shoulder, pressed the button that would release wireless impulses to actuate the alarm buzzer within the Hut.

Water drummed on his helmet, sloshed about his ankles. The gweelen was very near now, and backgrounded by it, a Venusian's dark form knelt; spidery arms flung out along the Curtain's invisible surface that was all that kept him from collapsing utterly, fish-mouth agape, as though still emitting its cry for help though sound no longer came from it.

Gree! It was Gree, his gills distended with pain, and in the jungle behind him the leeyas shrilled nearer and toppling stalks crashed as the pursuit closed in.

Chris tried to stop himself, slid in the mud, brought up against the wall that upheld the Weenie; solidity unseeable, impenetrable.

"All right," he gasped, thrusting himself back from it, "All right, fellow, I'll have you safe in a second," forgetting to get the whistle between his teeth, forgetting that Gree could neither hear nor understand him. Then, down on his knees in the mud, he had the black box in front of him, as though it were a camera with which he was taking the Venusian's picture. It was humming, between his left palm and the butt of the Wellsen he held in his right hand; it was emitting the complex series of etheric waves to which its coils were tuned.

Where Gree leaned against the Curtain there was a shimmer. Abruptly the Weenie was falling forward through the invisible barrier. "Pull your legs in," Chris whistled, imperatively. "Pull them in over the line."

Movement beyond caught his eye. A Neeleh's rounded head popped out from behind an orange bole. A tentacular arm flung up to hurl a throwstick.

The Wellsen jerked. Hissed. Head, arm, blazed brilliant, vanished. Where they had been a whorl of bluish smoke hung for an instant, was dissolved by the rain.

Gree had somehow writhed over the line. In Chris's hands the black box went lifeless. The Curtain was whole again and Haldane was free to spring to his feet and to twist the quivering Venusian.

The great round eyes were glazing, the gills barely palpitant, but from the crescent mouth came a whisper.

Haldane bent close. "The Neeleh," he made out, "drove us—from our kreels. Killed many—Tee Toom sent me—tell you—Neeleh are led by—by—" The whisper died away, its last word inaudible.

"By whom, Gree?" Haldane demanded. "Who's leading them, fellow? You can't pass out till you tell me—"

"No use. Chris." Haldane hadn't noticed Rand come up. "He can't answer you. He's gone.

"But he's managed to tell us, even if he did die before he could get the words out. Look." Darl Rand pointed down at the form that lay so terribly still in the water-layered mud. "Look at the wound that killed him."

Chris Haldane looked, and his skin tightened, was an icy sheath for his body. "A ray-burn," he whispered. "It just glanced his side, but that was enough. That means—it has to mean—that the Neeleh are led by an Earthman!"

"Right," a new voice boomed, from behind them. "A hundred per cent right. No, my friends, don't go for your Wellsens. I've got you covered with mine!"

"HOLD it," Darl Rand's low injunction stopped Haldane. "He'll blast us both before you can turn."

"Lift your arms," rumbled the intruder who incredibly had penetrated the impenetrable Curtain. "Lift them." Chris saw that Darl obeyed, imitated him.

Heroics could accomplish nothing. But this thing was bard to take.

Water sloshed behind him and en arm slid around his side, sleeved in the dark, dripping fabric of a space-suit, to pluck with its ingenious metal hand his gun from its holsters. It vanished. The strap of the key to the Curtain slid down his arm. Sleeve and jointed hand reappeared, disarming Darl. Footfalls sloshed again, retreating.

"You can turn now, but take it slow. I don't want to have to burn you."

Complying, Haldane saw, spraddled on columnar legs three paces away, a form as tall as himself, burlier than Darl Rand. The fellow wore a space-suit, but instead of a dural headpiece he wore one of vitrolene.

It was splotched with gray-black fungus! It was Fran's helmet that Chris had ripped from the cub's shoulders and left out in the gweelen.

A steel claw touched it. "Sorry about this," its owner rumbled. "For more reasons than one. I had nothing against the cub in the first place, and in the second the Neeleh's finding the corpse of their tribesman have put them completely out of hand."

"Yeah," Chris growled. "That must break your heart."

The rain was dwindling, rapidly, so that he could make out the face inside the helmet; skin, dark with a stubble of beard, shrunk tight over a heavy-boned skull, eyes deep-sunk in sockets like black wells. There was no triumph in that cadaverous visage, but pain not wholly physical, and the hair that crowned it was pure white. "I know I've changed plenty, Darl." the man was saying, "since you saw me last, but I didn't think I'd changed so much that you don't know me."

Rand groaned. "Gort! Gort Higgin, by all that's—How in the name of the seven Pleiades did you get here?"

"Patched some spare coils and bulbs together to make a key to the Curtain." He jerked his chin at a crude box in the mud beside him. "I ought to know its combination if anyone does, seeing that I sweat blood setting it up."

"I don't mean that. You were condemned to the Lunar Penal Colony—Don't tell me you've been pardoned!"

"No. I haven't been pardoned. Not yet."

"But no one has ever escaped from the Moon."

"No one, till I figured how to do it. Loading the tri-monthly freighter with stellite, four of us stowed away, showed up after it blasted off and—silenced—the crew. Interspace is big, Darl. There's plenty of room to hide a ship in the void, especially when you've had a couple of weeks to get off the Spaceways before the I.B.C. patrol starts looking for you."

"Weeks! Don't the keepers check their prisoners—?"

"Not if the prisoners don't want to be checked. Not if they've drawn lots to see who shall go, and who shall stay behind to keep news of the others' going from reaching Earth until the ship they went in has had time to vanish."

An odd, tense shrillness that edged Higgin's voice, the throb, throb of the blue veins bulging his brew, abruptly reminded Chris of something that sent a cold shiver through him.

"Once they've condemned you to that hell-hole, they can't do anything more to you than kill you, and death's something you pray for."

"Death's something you pray for," Higgin repeated, his voice thinning even more, "unless you've got a reason to keep on living. Unless you've got an account to settle with a man who has robbed you of the woman you loved, and of the work that let you forget her for a little while, with the man who has branded you a traitor and sent you to burn in a living hell. Where's Arnim Penger, Darl? That's all I want from you. Where's Stohr Penger's son?"

BLOOD pounded in Haldane's wrists, but Rand's answer was even-toned, calm. "What do you want Arnim for, Gort? He never did anything to you."

"He's flesh and blood of Stohr Penger." The way he spat the name was a curse in itself. "What do I want him for?" he said more calmly. "Why, that should be as plain to you, Darl, as it was to the three convicts who escaped with me, when I explained to them why we must come here. Stohr Penger's powerful, and his son is the apple of his eye. He'd do anything to get him back, safe and sound, wouldn't he? He'd even wangle a full pardon for them and clear my name for me. You're my friend, Darl. You want my name cleared, don't you?"

"Of course, Gort."

"Then you'll help me. You'll hand Arnim Penger over to me."

"Why shouldn't I? I'm your friend and I hate Stohr Penger for what he did to you. Why shouldn't I want to help you clear your name by handing his brat over to you? The only trouble, Gort, is that I can't. He isn't here."

"You lie!" Higgin screamed, his Wellsen jabbing at Darl. "You're lying to me, Darl Rand!"

There was nothing in Rand's tone, in his stance, to show that he knew his life hung on the twitch of a trigger.

"You've known me a long time, Gort Higgin. Do you think I would lie to you?"

The searing blast did not leap from the gun in Gort Higgin's hand. Rand's calm tone, his complete assurance, held it suspended!

The moment ended and a puzzled voice was mumbling, "But I read the message, in the old T.D.S. code, telling you that he was coming to Venus. That's why I brought my ship here. And the Neeleh spies told me they saw his space-yacht land, that they even saw him—There it is!" Higgin's gun pointed past them, suddenly, toward the landing field that in this one brief instant of time between the ending of the storm and the rising from the mud of the vapors it had beaten down could be discerned from here. "The silver ship they saw—Damn you, Rand!" The Wellsen sliced back to pointblank aim at Darl. "You did lie—"

Chris left his feet in a lunging, low dive under the hiss of the ray gun, flung arms about legs and put all his strength of shoulders, torso, in a twisting tackle that rocked the legs.

Half-dazed at the impact, he scraped away enough mud to regain sight, made out a blurred, heaving mass that went still in that same moment, resolved itself into a sprawled, yellow mound and a mire-plastered form.

"You all right, boy?" It was Darl! "You still in one piece?"

"Seems as if; are you okay?"

Darl nodded. "You jolted him hard enough to make him miss, and then I pounded the Wellsen out of his grip with one fist and whaled the other at his jaw. That wasn't as dumb as it sounds, because it smashed his helmet and he started choking. Even then he gave me a battle. Gort always did have the strength of an ox." Rand turned to the recumbent Higgin. "Come en. Help me get him into the Hut before he drowns."

"He's got it coming to him."

"He's still my friend, Chris, in spite of what the hell he's been through has made of him."

Chris collected the guns and the two keys to the Curtain and caught up with Darl. For a moment they went along silently, then, trying to regain normalcy, Chris observed, "One good thing, we don't have to worry about that I.B.C. spacecast any more. It was the alarm for Higgin an' his friends."

"Probably." A rolling rumble blanketed Rand's last syllable. He glanced up. "Do you hear that, Chris?"

"Yeah. Wonder how th' I.B.C. patrol spotted that they're here so quick."

"They haven't. That wasn't a spaceship, passing over. Look at the sky."

Haldane looked. Luminance was again suffusing the Compound's vaporous ceiling, but it was not the ruddy glow that had pervaded it before. This was yellower in tinge and the vast, overarching cloud appeared to stir with a promise of enormous movement. "I see. You think there's a typheen brewin'?"

"You'll notice that the leeyas are dying down," said Darl. "They're seeking shelter."

"Swell! If you're right, they and Higgin's pals are goin' to be kept too busy for awhile lookin' out for their own precious skins to pester us. Meantime, the storm's pretty sure to break up th' 'Nick' an' let us get word out of what's goin' on. Our troubles are over, fellah."

"Maybe."

Another rumble of thunder seemed to confirm him.

THE Hut shuddered constantly, so that the reflections from the fluortubes quivered eerily on the gleaming walls. Pots chattered where Laola Penger bent over the little stellite stove of which she'd insisted on taking charge. For hours, now, the typheen had held Venus Station in its grip, tearing at it with almost solid wind, hurling at its island foundation the battering rams of unimaginable waves.

Chris Haldane prowled, tensely silent, about the windowless enclosure, from lock-door to that from behind which the conditioning-machine kept up its incessant low burr, and back again. He wondered how Darl Rand could sit so stolidly at his desk beside the radio-set, adding column after column of figures in the Station account book, swarthy face shadowed, expressionless. He stared at the gaunt form that lay motionless on Darl's bunk and envied the deep slumber of exhaustion into which Gort Higgin had dropped at once when they had succeeded in resuscitating him.

Darl had said something odd when Haldane had protested that it would be more merciful to let the man die than send him back to the Moon. "I'd agree with you except for one thing."

He'd refused to explain what he meant.

Chris started for the radio. Halted, He was being absurd. The "Nick" couldn't have lifted in the five minutes since the last time he'd tested it.

"Ouch!" Laola jerked a finger into her mouth. A muscle knotted in Chris's cheek. "Burn yourself?"

"Coralee!" A hoarse croak swung them both around. Higgin was shoving up in his bunk, the chain that tethered him to it clinking, and his skull-like countenance was alight with a strange and terrible joy. "I've had a dreadful nightmare, Coralee. I dreamed that you were—you...." His voice was slowing, was losing its glad ring. "But—it wasn't, it couldn't have been, a dream...."

"No. Gort." Darl was on his feet. "It was no dream, and this isn't Coralee." He was beckoning the girl to him. She left Chris's side, went slowly across the floor, the back of her hand at her lips. "Not Coralee, Gort, but her daughter Her daughter Laola."

"Laola." Higgin whispered, the light not quite faded from his countenance as he peered at his old friend and the daughter of his old love. "Not Coralee, but so like. So very like. Come nearer, my dear. Don't be afraid; I just want to see you clear, I—yes, you're the very image of—of your mother, as I last saw her right here in this very Hut. You wouldn't believe, would you, to look at me now that a girl like you could ever have loved me?"

This then, Chris realized, was why Rand had not let Higgin die, so that he could show him the woman he'd loved alive again in the daughter of the man who'd condemned him to hell.

"Of course I believe it," Laola was saying, infinite compassion in her low tones. "Mother told me., just before she died, how handsome you were, how strong and how good. She told me there must have been some mistake at your trial, that you could not possibly ever have been a traitor."

"She told you that!" Darl's broad back blocked his view now, but Chris didn't need to see Higgin's face to know what was in it. "Coralee knew—"

THE crackle of the radio cut across that glad cry.

"It's lifted!" Haldane exclaimed, springing to it. "The 'Nick's' lifted at last." He snatched at the teletape, watched the signals form on it. V-S, V-S, V-S. No signature. That was queer. Come in V-S. The line's crests and hollows very sharp, as though the sender were very near. V-S, V-S. come in V-S.

He grabbed the key, rapped out. De V-S. De V-S. Who are you? Go ahead.

Never mind who we are. Where's Gort Higgin?

"Looks like a message from your pals, Higgin," Chris drawled. "They want to know what's happened to you."

De V-S, he sent as he spoke; De V-S. Higgin our prisoner. "I'm goin' to throw a little bluff. I'm sendin' 'Advise you to come to Curtain unarmed and surrender. I.B.C. Patrol advised your presence. Will arrive shortly.'"

Laola and Darl were beside him, tensely watching the tape.

V-S, it chattered. Bull. We know patrol nor nobody off Venus can get your signals.

"Well," Chris shrugged, "it didn't hurt to try."

Higgin's double-cross don't get over. We're coming for Penger. Ta Ta V-S. We'll be seeing you.

The set was silent. "Now it's they who're bluffing," Rand grunted.

"No. Darl." Higgin, who'd evidently read the message aurally, called from his bunk. "No, they're not. They—

"Don't tell me you gave them the Curtain combination." Rand wheeled to him.

The tethered man's face was ashen. "No. I didn't. But—"

"But nothing. Without it, they can't get through the Curtain even if they have fifty Wellsens."

"They're not coming through, Darl, but over the Curtain. We had it all figured in case I was wrong thinking I remembered the key. They're going to plane their ship over the Curtain, and you can't stop them."

"Holy—"

"Only reason we didn't do it that way right off was because I talked them out of it, knowing you'd fight us if we did and they'd kill you. I thought I could sneak in, snatch Arnim—God above! It's not Arnim they'll snatch, but Laola."

Higgin sprang from the bunk, was dragged back by the chain that had been locked around his waist. "If that scum of the System ever lay hands on her—"

"Hold it." Chris interrupted. "Hold everythin', the two of you. There's no need rushin' around like a bunch of headless Mercs; we've got plenty of time to figure an out. Even a space-ship can't plane through a typheen, can it?"

Darl's response was quiet-toned and devastating, "No. But you might have noticed, if you hadn't been busy otherwise, that the Hut stopped shaking ten minutes ago. Which means—Okay, Chris, climb into your boots."

He was already pulling on his own. "Their Wellsens can burn into the Hut, but we'll keep them from getting this far. They've got to pass the outhouses from the landing field, and I know a couple that are ideal for an ambush."

"That's the ticket! Those bozos are in for a hot—Hey! What the devil are you in boots an' coverall for?"

"I'm going out there with you and Darl." Laola smiled at him, almost blithely, though white lines had drawn themselves around her mouth. "You wouldn't be in this mess if it weren't for me, and I'm not letting you go out there to fight for me while I skulk in here, safe."

"That's insane," Haldane protested. "It's—"

"A fool stunt only a female would pull? Well, I'm a female and I'm pulling it."

"The hell you are!" He started for her, was stopped short by the sudden threat of the Wellsen she'd snatched from the wall rack. "What—"

"111 meet you outside." She darted to the lock-door before he recovered from his amazement, was out through it.

It slammed shut. "Darl!" Chris heard behind him. "Darl!" Gort Higgin's voice, thin again but somehow differently from what it had been out on the Compound. "Let me loose. If you were ever my friend, unlock this chain so I can go out there and fight for her."

Fat chance, Chris thought as he fought with the door; his fingers clumsy. The convict's chain clinked as the portal yielded, but he had no time to hear Darl's refusal, and then the door shut off sound from inside the Hut.

The lock's other door banged closed in the same instant. The tiny vestibule was empty.

Chris's blood pounded in his veins as he twisted to the shelf on the side-wall and snatched a helmet from it. "Th' bantam," he murmured as he zipped it to his coverall. "She sure has what it takes."

Not waiting to test the filter membranes, he got urgent fingers on the handle of the outer door, jarred it open and lunged out—

Into a blinding burst of light that lanced his eyes with pain!

He locked his lids against the blaze. A hand laid itself on his arm. "Look," Laola whispered. "Open your eyes and look." He pried them open.

The wind though still strong was dying, but the tornado had broken the eternal cloud-pall that brooded over Venus, had rifted colossal valleys between towering vapor mountains that changed ceaselessly in form, that rolled in upon themselves, merged, separated, seethed with swift transformations slow-seeming only because of the enormity of the masses they involved.

Unmasked at long last, the gigantic sun imbrued these awesome heights with color so vivid as to be almost unbearable; purple and orange and a deep, deep blue; or laid in their momentary ravines vast cerulean shadows that flamed instantly crimson...

Chris Haldane was dwarfed abruptly, abruptly his joys and sorrows, his ambitions and frustrations, were of less importance than the dancing of a dust mote in a flashlight's beam. This loss of significance, this sudden scaling of self against a cosmic rule, was beyond endurance. For relief from it, he fled to the human who shared it with him.

"Laola," he said her name. "Laola, girl," and could say no more because there was so much to be said and no words in which to say it.

"Chris." She came around to face him.

"I know what you and Darl think of me; I don't blame you. But will you let me tell you something now, something which may put a different light on it all?"

He searched her face again; there was nothing of the spoiled playgirl in her eyes now. "Yes," he answered. "Tell me."

"Arnim Penger is my half brother, Chris—but—" she hesitated. "But I've known him all my life; I know he's capable of being something fine if it can only be brought out. There's no risk I wouldn't take for that."

Chris blinked. "But what has all that to do with this madcap dash across space?"

"More than you realize. You see, Chris, Arnim has one quality which all his wildness has never touched; he's a man of his word; he's never broken it. No matter what the conditions were under which it was made, he's always come through.

"I got him very drunk one night, then tried to persuade him to do something for himself; it ended up in his betting me I didn't dare make the jump from Terra to Venus alone. You know the fantastic way a person's mind jumps from one thing to another when they're drunk?"

Chris whistled softly. "I think I'm beginning to get it; you bet him you could do this thing alone; if you won, he'd put himself under your direction."

"That's it—only, now I've just succeeded in being a nuisance to you and Mr. Rand in an emergency...."

Her hands were somehow in his and they were trembling as his were trembling—Thunder rumbled between them. Not thunder, but—

"The prison ship," Darl's voice boomed in Haldane's ears. "They're blasting off. They'll be here in minutes "

RAND was just stepping out of the Hut—Another helmeted figure followed him!

"Higgin!" Chris exclaimed. "You—you're nuts, Darl. You can't—"

"Since when are you telling me what I can or can't do?—Get going. We haven't much time left."

No use arguing. He was Chief of Venus Station, his command absolute. Chris started after him, still clinging to Laola's hand, Gort Higgin behind. They hurried along the Hut's wall, around its farther corner—

Darl stopped short. Haldane came alongside him, saw what had halted him, what was wrenching from him a sound half curse, half groan.

The paste-like mud was piled against this aide of the Hut to its roof. The mud, drifted like dune sand by the typheen's terrific pressure, had mounded over every one of the Station's smaller structures, had obliterated them. The Compound was a sea of gigantic yellow waves frozen motionless, and there was no place for them to lie in ambush, no cover that would hide them from the convicts' ship that, altitude gained now and tubes silent, planed to the attack.

"Pretty," Chris grunted. "What do we do now?"

"All that's left is to get back in the Hut and make a stand there."

"A lot of good that'll do us. Their Wellsen beams will bore through its walls like a hot iron through butter an' we won't even be able to see where they are, to fire back, Well die like rats—Look, Darl!" An idea struck him. "Why can't we make a dash for th' Comet an' blast off? Her lock's to leeward an' will be clear of mud. With th' fuel she's got left we could maybe hop her up through th' 'Nick' an' send an SOS, pray there's an I.B.C. patrol ship near enough—"

"No good. That's a prison-ship, remember, undoubtedly carries a couple of Tracy cannon. They'll blast us out of the sky with a million volts—"

"Maybe not. How about it, Gort? Have they—? Hey!"

Higgin wasn't behind them.

"Where—?"

Seventy-five yards away he was just reaching the crest of a mud-dune. "Th' dog's beatin' us to th' yacht!" Chris grabbed his Wellsen from its scabbard. "But I can stop—"

"No, you fool!" Darl's fist pounded the gun from Haldane's grip. "Don't you see that he's going to—"

A sudden shadow closed his throat. It flitted past, but he was staring up at the thing that cast it, at the black shape that was limned against the crimson sky.

Spread-winged, the hawk ship was still distant but it grew swiftly, sweeping across that stupendous sky. In moments now it would swoop down—

Not more than a mile off, it was huge now over the gweelen. It was slanting down to land—Enormous thunder blasted from it—Not from the convicts' craft but from the Compound. A silver shape leaped into the sun's blaze, a wingless projectile that trailed blue flame as it hurtled straight for the black vessel.

"The Comet!" Chris gasped. "By the rings of Saturn, it's th' Comet!"

And the two ships met.

A second sun blazed in the sky. A giant fist smashed girl and man flat. Silence crashed down and Laola was in Chris's arms and he was quivering.

"He saved us." It was as though someone else said that, but the words came from his lips. "Gort Higgin saved us. That's why he was running—"

"Exactly, you blasted young idiot," Darl boomed. "And if I hadn't jumped you, you'd have stopped him. I didn't know what he was up to, but I knew he'd thought of some way to save his daughter—Holy blithering apes," he caught himself. "Now I've done it! I ought to kick myself from here to Sirius—"

"Not because of me, Mr. Rand." Laola struggled up to a sitting posture. "In our last talk together. Mother told me that Gort Higgin was my father. I—She made me promise that I'd never let him know I knew." There were tears in her voice, but there was a strange joy in it too. "I—That was one reason I didn't care much what happened to me on my flight alone across Space, but now I know I was wrong. I understand them now, after these hours I've just lived through. After I've heard the leeyas...."

"They were very young," Darl Rand said softly as her voice trailed away. "And death, screeching in the jungle, was very near. They never saw each other again."

"Never!" Chris exclaimed. "But Higgin's letter, Darl, that you told me about—"

"Asked for news of the child he knew was his but had never set eyes on."

"Then when it was turned over to him, Stohr Penger must have learned—"

"No. It was written in such a way that only Coralee could understand its real meaning. Penger discovered only that there was some secret intimacy between his wife and Gort Higgin, but that was enough to make him do what he did."

"Look, Chris. Look there." The wind was gone and the clouds were rolling together again to blanket Venus Station, but there was still a patch of blue sky where Laola pointed. In this a wisp of vapor torn from the roiled masses was radiant with crimson light.

"It looks like a space-ship," she whispered. "Like the wraith of the Comet taking Gort Higgin to the sun."

CHRIS smiled suddenly. "Laola," he said. "I've been a heel about you. It's not your fault we're at different ends of the social ladder; you have courage, and you're human. If this were a popular romance, I suppose we'd be in each other's arms now."

There was something in her eyes that tugged at his heart. "We can make it a popular romance."

For an instant, the smile of her infected him, then he remembered Gort Higgin and remembered Venus Station.

"Uh-uh," he grinned. "I'm all-out for happy endings, and it just wouldn't work out that way with you and me.

"If we should ever meet again, well remember and be friends, kid."

She looked at him, the light gone from her eyes now. Then a different kind of smile crossed her face—the kind she knew he'd prefer seeing. She held out a mittened hand. "Thanks—pal—"

Very faintly in the hush, they heard from within the Hut the chatter of a radio message that could come only from outer Space—from Earth, thirty million miles away.

The 'Nick' had lifted at last.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.