RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Astounding Stories, February 1934, with "The Living Flame"

The "Oak Island Mystery" refers to stories of buried treasure and unexplained objects found on or near Oak Island in Nova Scotia. Since the 19th century, a number of attempts have been made to locate treasure and artifacts. Theories about artifacts present on the island range from pirate treasure, to Shakespearean manuscripts, to possibly the Holy Grail or the Ark of the Covenant, with the Grail and the Ark having been buried there by the Knights Templar. Various items have surfaced over the years that were found on the island, some of which have since been carbon-dated and found to be hundreds of years old. Although these items can be considered treasure in their own right, no significant main treasure site has ever been found. The site consists of digs by numerous people and groups of people. The original shaft, in an unknown location today, was dug by early explorers and known as "the money pit". "The curse" is said to have originated more than a century ago and states that seven men will die in the search for the treasure before it is found. To date, six men have died in their efforts to find the treasure. — Wikipedia.

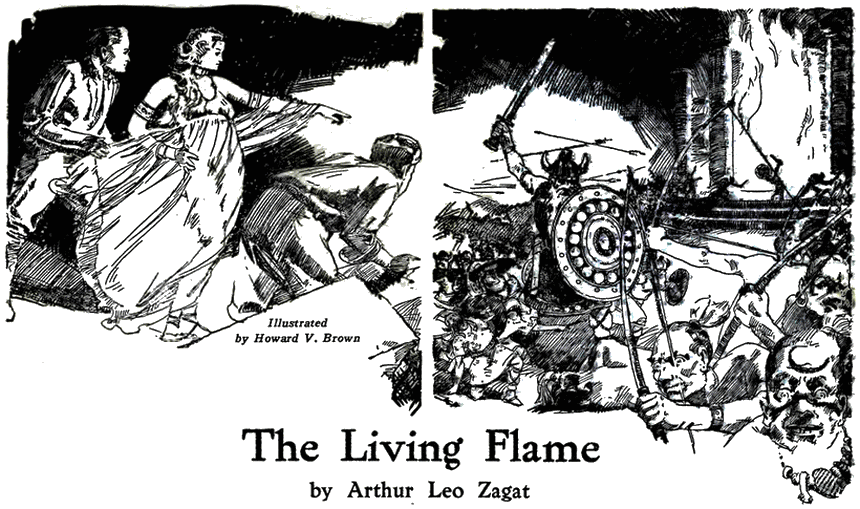

"See!" she cried. "With his great sword

he fights to drive them from the flame!"

Beneath the historic, sea-flooded shaft on Oak Island was war and flame!

THE pit in which black water heaved, somewhere beyond our camp fire's glow, was a challenge, and Eric Hadding and I were here to answer its defiance. It was of immemorial age, that was certain, for there were those along the shores of Mahone Bay whose families' occupation dated back three centuries, and they had no memory of when the hole had been dug.

They called it "Captain Kidd's Treasure Pit," and babbled of millions in gold and diamonds that it contained. It was not within reason that such was the thing's genesis, for no freebooter ever would have spent the weeks of labor involved in its fashioning, no pirate could have had the peculiar knowledge required by its strange fashioning, no buccaneer would have placed his hard-won loot beyond even his own reach.

They had warned us against the shaft, those weather-bitten Nova Scotians; whispered of a curse on any who tampered with it, shaken their heads in dire prophecy that we should never see the dawn if we persisted in passing the night on Oak Island. But we were returning empty-handed from a three months' cruise along the coast of the maritime provinces, sixty miles away was Halifax and the end of our journey, and this was our last chance at what we sought.

Eric, assistant professor of history in an old university, had conceived the idea of searching for traces of Viking visits to the coast of the New World, had persuaded me to accompany him on his quest, had set out eagerly, convinced that somewhere along that rock-bound littoral he would find proof of his hotly held theory of a Norse settlement antedating the Genoese by four hundred years. And the results had been nil. Nil, that is, until, stopping at Chester in Nova Scotia for provisions we had heard the strange story of the pit on Oak Island. Thirty years before, the tale ran, two strangers from the States had appeared with a mysterious map. They had hired men to dig, had taken them out to the tiny wooded island and set them to work under a dead oak from which hung a rusted chain.

Twenty feet down the excavators had struck a level, concrete floor. Breaking through this they had delved farther, struck another platform of concrete, and, widening their pit, had discovered they were in a concrete-lined shaft, circular, and some fifteen feet in diameter.

Persisting, they had burrowed a hundred feet into the earth when suddenly the sea broke in and ended their labors. But it was this sudden irruption of the ocean that had furnished the final outré touch to the strange construction. For it was not a natural fault in the rocky foundation of the islet that admitted the bay, but an artificial tunnel, concrete lined like the shaft itself.

Our decision was quickly made. We must examine this mysterious pit, must solve the question it posed. The oldsters who had spun the yarn shook their heads ominously. There was no luck in it; of those who had dug there, none had lived the year out, all had died inscrutable, violent deaths.

Hadding's only response, however, had been a firmer setting of his jaw, and a livid reddening of the birthmark on his bronzed chest, the stain like a closed fist whose darkening warned of his rising temper. We had boarded our little launch, the Njord, and foamed across Mahone Bay's sunset-carmined surface without another word.

I was restless, uneasy. Eric, squatted across the fire, brooded in silence, his shock of hair startlingly blond even in the flame's orange glare. He was seeing visions, his eyes slitted in that sea hawk's face of his, his columnar neck corded. There were queer rustlings among the dark trees and tiny plashings from the pit. Now and then, as a knot in the fire caught and flared, it seemed to me that something moved just beyond the sphere of invisibility hemming us in. At last I could stand inaction no longer.

"Bring the flashlight ashore, Eric? I've got a notion to take a look at that well before we turn in."

Hadding jerked his head to the ground at his left. "It's there. But you won't see much. Too dark."

"Right. I'll take a look-see, anyway. Coming along?"

"Might as well."

The ground about that strange well curbing was muddy, and the well head itself rotted and slimy. The water surface, about three feet down, sent back our light like a black mirror. I raised the flash to illumine the rough concrete of the shaft sides.

"Queer thing about that," I muttered. "Concrete was used in ancient Rome, but there is no record of its being known in America till the early nineteenth century."

Eric grunted. "The Norsemen used it sparingly, must have brought knowledge of it on their migration up from the south of Europe. Say!" A sudden excitement came into his voice. "What on earth's that? Move your light—over there on the wall."

I focused the beam where he had pointed, six inches below the top, just across.

"By God!" Eric exclaimed. "It is—sure enough—"

"What's the fuss?" I couldn't see anything but some rather deep scratches in the concrete, moss filled and standing out with surprising distinctness.

"Runes, man! Runes!" He was actually quivering.

"Ruins? This thing looks pretty well preserved to me."

"Ass! R-u-n-e-s. The ancient angular writing of the northern races, the Norsemen."

"Are you sure, Eric?" I quit my chaffing. "That would mean there were Vikings here, let's see—"

"A thousand years ago! Long before Columbus. Confirming the old, disputed legends. Man! This will put me top of the heap! It's the break I was hoping for when I proposed this trip."

"Can you read it?"

"And how! Studied under old Sotus Bugge himself. Shut up a minute and I'll translate it."

IT took Eric longer than a minute, muttering harsh, uncouth

sounds that I recognized as the primitive old Norse he had taught

me as a pastime on our long journey along the coast.

At last he exclaimed: "Got it! And it's damn queer stuff, too."

"Well, spit it out."

"Roughly, here's what it says: 'Rejected by Surtur—Spewed out by Njord—Hagen descends to seek Asgard—Who dares follow braves the Norns.'"

"Poetic, but it doesn't seem to mean much."

Eric's face was aglow, and there was a far-away look in his eyes. "It means a hell of a lot—tells a story that's been waiting ten centuries for me to come and read.

"Hagen died down there. The treasure is armor, my boy, weapons of a by-gone day about which we know very little. Bones, perhaps, that can be measured and may solve a thousand questions plaguing the archaeologist, the anthropologist, and the historian."

His jubilant voice boomed out, and there was a sudden reply from the deserted wood—a mocking laugh, shrill and unhuman. We whirled to it, and momentarily my beam caught a white shape among the trees. It vanished, and Eric leaped in pursuit. "Wait!" I yelled. "Wait for the light!"

The only reply was that unhuman laugh and the threshing of Hadding's big body. I plunged after him into a thicket of tangled underbrush, tripped over a trailing vine, slid through earth-odored loam. The sound of Eric's bull-like progress was fainter. I got to my feet, lost a moment searching for the torch, lost all trace of my friend's progress. Suddenly, from behind me, the laugh sounded again, and Eric's roar: "Stop!" I whirled, heard a splash, a thin shout, "Carl!" another heavier splash, and silence.

I was back in the clearing, but Eric was nowhere. Only a long, dragging rut in the mud showed where he had gone, and the tossing of the water in that infernal pool. Evidently whatever it was that had laughed had circled and dived into the well, and Eric, snatching at it, had slipped and plunged after. God! I knelt on the slimy edge of that shaft, holding my beam on the water. Eric would come up in a moment—he swam like a fish—he couldn't be drowned. The agitated surface subsided, and nothing showed. He may have hit his head against the stone, I thought. But why didn't his body rise?

There were iron rungs in the shaft wall, rusted through, pointed. He might be caught in one of those; there still might be a chance to save him. I stuck the torch under the topmost rung so that its beam was thrown straight down. Then I poised on the curb, was curving through the air—my finger tips cut icy water.

Down, down, down through blackness. Nothing but dark and the numbing chill of that water. No sign of Eric. Down, till hammers battered at my temples and knives turned in my breast. I must—turn back.

I couldn't.

I fought to hold my breath, fought till my eyes seemed forced from their sockets; instinctively, for I knew I must eventually gulp water and die. I didn't want to die, alone, in the dark. Was that light—far below? Light! Impossible! But there it was, a dim radiance to which the current swirled me down, faster and faster while I was nothing but one huge ache.

The light was all around me, green, illuminating shaft walls that slanted inward, funnel-like. I shot through the tip of that funnel, bumped against rock. A hand grasped my arm and pulled me from the icy water. I—could—breathe. Oblivion swept in.

Consciousness came back with the thunder of crashing waters. I opened my eyes. Eric was bending over me, his hair dark with wetness, his clothing dripping. His sun-black face was grim with anxiety. "Carl, old man!" he shouted above the tumult.

"You ape!" I gasped. "Why didn't you wait for the light? What was the idea of—"

He grinned relievedly. "From which I take it you're all right. Did you slip in, too?"

"Slip in, hell! Think I bat around blind like you? If you were going swimming, I wasn't going to be left behind."

"You jumped in after me? Nut!" Affectionately he added: "Of all the half-wit stunts!"

I STRUGGLED to my feet. We were at one end of a narrow but

comparatively high cavern. The astonishing light that pervaded it

came from everywhere and nowhere, a soft white radiance that had

no warmth. The air was fresh and sweet. Beside us, thundering

down through a hole in the roof, was the swirling current that

had brought us here. It crashed along the slanting terminal wall

of the cave in a self-scooped channel, plunged whirling and

hissing and foaming into a deep basin in the rock floor, and

rushed away, a wide and turbulent stream, to lose itself in the

dense forest of grotesque stalactites that blocked our view. On

either side of this underground river was a space and dry terrain

some ten feet wide.

Till now we had been shouting above the noise of the fall, but I discovered that I could pitch my voice under the clamor and be heard. "Eerie place, isn't it?"

"Everything seems luminescent, down here. Some form of radioactivity, maybe. And there is something else, Carl. I—it sounds silly—but I have an uncomfortable sensation of being watched."

I shook my head. "Nonsense! There couldn't be anything living down here."

"Nonsense, is it? It was something alive that dived into the pool before me, Carl."

A little chill ran up my spine. Then I grinned. "If it could get upstairs, we can."

"We'd better find the way damn quick. Before we get hungry and thirsty."

"Well," I said, "the way out isn't up that shaft."

"Devilish strong current down here, isn't it? Felt like the whole sea was on top of me. Which it was of course, coming in through the tunnel. How do you account for the fact that the well up there is filled in, spite of this hole at its bottom? That's a puzzler!"

"Easily. The outlet here is not as large as the inlet from the sea. It's like letting water into a sink bowl faster than the drain can carry it off, only in this instance the upper level will never rise above that of the sea."

Eric, however, was paying no attention to me. He was tensed, suddenly, watching intently. I followed the direction of his eyes, through the impenetrable ranks of the drip formation.

"What is it?" I grunted.

My friend's lips hardly moved. "Thought I saw something off there. Something moving. Keep quiet."

Now I, too, was aware of that indefatigable but unmistakable sensation of unseen eyes on me. I squirmed under it, staring in turn through the serried, crystalline columns that seemed so deserted. And then—

"Good God!" Eric groaned. "Do you see it, too, Carl, or am I batty?"

"I see it," I said grimly. "Guess we're both dreaming."

It was the final touch of unreality, that which appeared from behind a cloud-white, glowing pillar about twenty feet away on our side of the river: I pushed a fist across my eyes and looked again. But it was still there—a man. A big-headed, miniature-bodied man, not two feet tall.

He stood there on wee bent legs and grinned at us. And we stared back, unable still to believe we really saw him. He had a great hooked nose, surmounted by eyes that were twinkling black pin points. His hair was a dull black, coarse, and somehow animal-like even from this distance, and there was something feral, too, about his long, sharp chin.

It was what he wore, however, that held us staring, unable to move. This troll, this grinning dwarf, was helmeted, by all that was holy, with a conical, silvery casque to either side of which a golden wing clung, and his wee body was clad in a glittering coat of chain mail. Knee-length, the meshed, metallic fabric fell, belted and skirted, and below it his pipe-stem legs were covered by crisscross leggings of scarlet silk.

To complete the picture, a shield was strapped to his left arm, no bigger than an oversized dinner plate, and in his doll-sized hand he held aloft a three-foot spear.

We gazed pop-eyed at the toy-size warrior who grinned amiably at us. At last Eric grunted, straightened, and raised both hands above his head, palms outward. Understanding, I imitated him.

AT this immemorial sign of friendship the dwarf clanged his spear against his tiny shield and started into motion, trotting straight to us on those wee legs of his. About two feet away he paused, bowed, and said something in a high, shrill pipe.

Again an exclamation of astonishment escaped me, and I saw Eric's face light up as with an inward fire. For in a thin, child's voice the astounding gnome was speaking pure old Norse, the language of the Vikings, the language of the runes overhead. Eric replied in that booming voice of his.

I must have presented a ludicrous sight, standing there with open mouth, my eyes shifting from the tall form of my friend, gigantic seeming in contrast with the animated doll caparisoned in armor that might have been ravished from a museum.

As nearly as I could make out, the little man was demanding, politely but firmly, that we accompany him to some unnamed destination. Eric pressed for information, as to who and what he was, and as to where he wished to take us. His name was Arnulf, he said, but to all other questions he returned only the reply: "Later. When we arrive you shall learn."

At last Hadding turned to me. "What say, Carl? Do we accept his invitation?"

I hesitated. "He seems friendly enough, and we can't get into any much worse mess. But—"

"But what?" Eric's mouth was suddenly a thin, straight line. "Friendly or not, I'd go to the gates of hell with him. He talks the old Norse. The armor he's wearing, the casque, the brynnie, are authentic. I'll swear to that. They're miniatures of stuff I've seen dug up from mounds and Skaale ruins in Denmark and in Greenland. And you're wondering whether it's safe or not!" There was contempt in his voice. "Stay if you want. I'm going."

"Try and leave me behind." I grunted, holding my own temper in leash. "Just try."

Hadding gurgled an assent to the dwarf, and Arnulf bowed again. Then he turned and stalked off along the river bank, his dignity somewhat spoiled by his diminutive size. We followed in single file, twisting in and out among the translucent pillars of the drip formations, climbing over debris that were these same columns broken by some earth heaving in by-gone ages, always with that strange, cold, sourceless light about us and the roaring of the cataract in our ears.

We had progressed thus for what I judged to be about a half mile, when suddenly our guide halted, motioning to us to do the same, and appeared to be listening intently. Then he whirled to us and called out something I did not catch. Eric seized my shoulder, forced me down with him behind a huge, rounded fragment of stalagmite that was near by.

"What's up?" I exclaimed.

"Don't know," Hadding grunted. "He said to hide, quick. Didn't seem scared, though."

"I'm going to look." I was still uneasy, still distrusted the little man. Was this some trick to permit more of his fellows, perhaps, to catch us unawares, to overwhelm us by their very numbers? I got down low, poked my head cautiously beyond the shielding stone.

There was Arnulf, himself bent low behind another bit of rock. And beyond him—

There seemed no limit to the surprises this place held for us. Beyond the gnome's covert I saw another figure, almost stranger than Arnulf himself, certainly more fearsome.

This one was no dwarf, though rather stunted, and he was naked except for a breechclout. He moved silently, slinking toward us with a smooth, effortless stride, the stride of a savage. He had the high-cheek-boned head of an aborigine, flat-topped, with tiny squint eyes, thick, protruding lips, and long black hair. His skin was coppery, and seemed to have an oily film over it; there was a long bow in his hand and a quiver of arrows slung over one sinewy shoulder.

"Eric, look at this!" I whispered.

"My God, Carl. A Beathic!"

"A what?"

"A Beathic—Indian to you. One of the original race that peopled Nova Scotia before the white man came."

"What's this place? A sort of old men's home for obsolete races? Jumping Jehoshaphat, look at that!"

As the savage had come opposite Arnulf's covert, the little fellow leaped into view, spear poised, shield upraised. He sprang again, and before the Beathic had time to so much as give vent to a startled cry, the dwarf's tiny spear was transfixed in the savage's throat. The aborigine toppled, almost crushing his wee conqueror in his fall, and lay motionless.

"Lord, but he's spunky!" I exclaimed.

The little man clambered atop his victim and tugged at the protruding shaft of his spear. And suddenly there was a howling ring of savages about him, appearing apparently from nowhere. They encircled him, each with an arrow fixed in a taut bowstring, surrounded him with a bristling chevaux-de-frise. But the wee warrior looked up calmly, and there was neither surprise nor fear in his face.

One of the Beathics, distinguished from the rest by a horrific painted mask in yellow and glaring red, said something I could not make out, but he sounded like those little firecrackers one shoots in strings on the Fourth.

Arnulf's lip curled, and he replied: "The strangers are safely hidden, dogs, far away from here. Threaten me not, for the most devilish of your tortures will never wring their secret from me. And beware the vengeance of the Horder folk."

"Good boy!" Eric grunted. "He is trying to save us."

The Beathic leader contorted his features with what might have been intended for laughter. He spluttered something, and two of his fellows stripped the strings from their bows. Stepping forward, one of them lashed the little fellow's wrists behind his back, while the other hobbled his ankles so that he could just shuffle along. Arnulf bore all this in haughty silence, but every line of his tiny body breathed defiance.

"We can't let them do that," I jerked out. "Let's hop them, Eric."

"Wait! They're alert now, and outnumber us five to one. We'll follow them till we get a better chance."

THE painted-faced aborigine creaked another order, and the

group crowded around their captive. They started off, bearing

away from the stream. Arnulf did not have to be pushed,

apparently he had decided struggling would be useless, but the

savage band progressed slowly because of his lashed feet. They

made no effort to move quietly, apparently taking at its face

value Arnulf's assertion that we were nowhere near. Thus it was

easy for us to follow them unobserved, and we slid silently

through the dense clusters of translucent pillars, guiding

ourselves by the clatter they made.

We had not noticed that the cavern long since had widened, and it was some time that we progressed thus. Then a shout from the Beathic band, a shout clearly of triumph, was answered by a call from far ahead.

"We are done for now," I grunted reproachfully. "They're meeting others, maybe their main encampment, and we'll never get him away."

Hadding's brows were knitted. "Seemed to me like only one answering them, Carl. Let's get closer and see what's up."

We moved a little faster, but still cautiously, and I glimpsed the procession. They were filing down a steep decline, into what seemed a deep pit, from the center of which arose a monkey-like chattering. And suddenly a scream knifed through that chattering, a woman's scream. A woman's wail, hysterical, making-words in the old Norse. "Arnulf, they have you! Then the Great One—"

And then came the little warrior's voice, calm, soothing: "Nay, Lady Gerda, this slime have yet to face the wrath of the Great One. But how came—" The sound of a heavy hand on flesh cut the sentence short.

Arnulf was dripping words that were icicles of poison; cold, venomous: "Do that again, or lay one filthy finger on the Lady Gerda, and the Great One will flay all the Yotun folk with scorpion whips."

Whoops of derision, horrid rattling of savage laughter, answered him. "Yotun no fear Great One, no fear Horder folk. Take woman, take you, same way take pleasant land from little people. We Horder folk soon." Broken old Norse came in the spluttering, grating voice of the savage chieftain. "But you tell us first where strangers."

My eyes sought Eric's, two balls of blue flame.

"Carl," he whispered. "There's a woman in the power of those filthy creatures."

I shrugged. "They are all below the pit edge. It is safe to get closer, I think."

We were on our bellies, crawling, squirming along the ground to that pit edge. Little stones rattled under us. But they didn't hear us, absorbed as they were in baiting their prisoners. We were looking down at them, and they didn't see us.

There were eleven of the savages squatting on grimy haunches in a half circle about their prisoners, the ten that had captured Arnulf and another. The little fellow was lashed to the stump of a stalagmite, helpless, but there was no surrender in his face or in the erect posture of his tiny figure; defiance, rather. And, tied to another thin pillar of slimy rock, blue eyes flashing with anger, with repulsion, was the slim figure of a girl. I felt Eric's body quiver, pressed against mine, as he saw her. And my own throat went dry.

She was tall for a woman, tall almost as myself, and her long robe of white silk, tight pressed by its lashings, more than hinted at the perfect lines of her body. Her hair was spun gold, close helmeting her high-held head, and flowing to the ground in two arm-thick golden braids. There was a white austerity in her face, her nostrils flared indignation, and her red lips were compressed to a thin line of wrath.

That face did not present the fine chiseling of classic beauty, but its broad planes, its sturdy modeling, was to me far more attractive than the most perfect Grecian mask. There was intelligence in her high forehead and strength in the cast of her jaw, yet even now that countenance was somehow tenderly feminine.

There was an almost inaudible sound from Eric, a gasp, and I pulled back, twisting to look at him. He lay absolutely motionless, his gaze fixed on the girl's face, drinking it in. I saw another quiver run through him, and his big hands slowly clenched. I touched his shoulder. He started and dislodged a pebble that slithered down into the pit, its tiny rattle a roll of thunder to us.

A BEATHIC heard the noise, sprang to his feet, with a

guttural' exclamation, pointed and snatched for his bow.

"Come on!" Eric shouted, leaping down, straight down into the middle of that ugly band.

Somehow I found two fist-sized stones in my hand, found myself, with no conscious-volition, in mid-air, landing in a cluster of fetid, naked bodies. I flailed at a bestial head, felt bone crunch sickeningly under my fist, whirled to the next shrieking savage, and struck again. I heard Eric yelling something unintelligible, got a glimpse of him, red-eyed, mouth open in a bellow, blond hair streaming, huge fists rising and falling, bashing in a twisted, savage face.

We had come upon them so suddenly, so savagely, that three of them were down before a retaliatory blow was struck. But then they were fighting back.

A stinking form ducked under my smashing fist, closed with me, wrestling. The unclothed skin was sweat-covered, slippery. He snarled animal-like, and his teeth sank into my sleeve. My fist beat down on the back of his exposed neck; there was a snapping sound, and he fell away. There was a knee in my back, hands-clamped on my throat. I couldn't turn. I ducked forward sharply, and the garotter catapulted over my head, smashed against a rock.

Another shrieking Beathic had plunged at me, a sharp-pointed arrow in his hand, stabbing. My fist crashed into his face, and it exploded in a bloody smear. I whirled to meet the next attack. But there wasn't any. The pit was a shambles.

Eric grinned at me. "One got away, Carl. But the rest won't do any kidnaping for a long time. Good scrap!" There was a long, bleeding scratch across his cheek, and a mouse (#US for a black-eye bruise) over his right eye. Otherwise he was unhurt.

"Swell!" I rubbed my aching throat. "Did you—"

Hadding, however, wasn't listening. He was striding over to the girl, to Lady Gerda. And she was watching him come. I blinked when I saw her expression. It wasn't gratitude, admiration alone that lighted it with an inward fire. It was as if the bonds about her were not there, the contorted barbaric bodies underfoot, myself, Arnulf, nonexistent. Only Eric mattered, striding toward her lithely. I saw his face, too. For them this might have been a trysting place appointed when the world began.

"Release me, stranger with the-black hair."

Arnulf's call pulled my eyes away from the couple. I got over to him, sawed him free with the edge of an arrowhead. He snatched the arrow from my hand, and, before I knew what he was up to, plunged it into the breast of an aborigine at my feet.

"That one still lived," he muttered, and looked around at the others.

I grabbed him. "You little devil!"

"Let him alone, Carl," Eric called. "He is right according to his lights. The Vikings left no living enemy on the field. Lord knows what the beasts would have done to our corpses if they had licked us."

I released the fierce little fellow.

"Wait here. I shall return." He scuttled up the pit side and was gone.

They didn't talk, Eric and the girl, just stood and looked at each other. It sounds inane, set down in black and white, but it was not in me to laugh as I saw them. Rather, I burned with a great envy.

Arnulf was back. He stood on the pit edge and called: "Come, now, if it please you, Lady Gerda. I have my shield and spear and can defend you and the strangers against all perils."

"The bantam would do it, too, if he could," I muttered to Eric, keeping my face straight. "There sure is plenty of guts tied up in that little package. By the way, aren't you going to introduce me to the lady?"

He jerked down out of the clouds with a start. In rather stilted Norse he said: "This is Carl, my companion and friend, Lady Gerda."

The corners of the girl's mouth lifted in a faint smile of acknowledgment. "We owe you much, Arnulf and I. But I shall leave it to the Great One to express fittingly the gratitude of the Horder folk."

"Hasten!" Arnulf shrilled. "Or the Yotuns will bar our passage."

We scrambled out of the pit. Although Eric seemed to have forgotten everything but the girl, a thousand questions trembled on my lips. But as we reached the top, a long horn blast sounded from the distance.

"Arnulf!" Lady Gerda exclaimed. "'Tis Rolf's horn. The Great One comes."

"The Great One comes," the dwarf repeated, and there was a lift in his thin voice, a curious awe.

Both turned in the direction of the hoarse sound.

The girl funneled her hand at her mouth, and called: "To me, Horder folk. To me."

Again the trumpet sounded, and close upon it a curious procession came in sight.

A HORDE of dwarfs, armored and helmeted, appeared and disappeared in the gaps between the columned drip formations. At their head was a little fellow whose coat of mail was of gold, whose casque was surmounted by a dragon's head worked in silver, and about whose neck hung, by a gold chain, a ram's horn mounted in a delicate filigree of gold and silver, incrusted with precious stones.

My eye, however, went to the figure just behind the trumpeter. He would have been tall even in the upper world, but here, among the tiny-statured gnomes, he towered colossal. A true Viking, gold armored, gold helmeted, a silver eagle for his crest that seemed poised for flight, so finely wrought it was.

His yellow hair fell in curls to his huge shoulders, framing a ruddy face in which piercing blue eyes were rimmed by fine wrinkles that told of gazing across stormy seas, framing a stern, sharp countenance in an aureate glow. Mouth and chin were hidden by a drooping mustache and a huge blond beard, yet, strangely enough, I felt that I had seen those rough-hewn lineaments somewhere before.

The Viking saw us, saw Gerda. He scowled and strode past the trumpeter, his great sword sweeping out of its scabbard. My feet shifted, and I tensed for flight.

But Gerda called: "Friends, O Hagen! They are friends. Put up your sword." She advanced to meet him.

They came together a little before us, and he bent to her. "Gerda, you are safe?" He kissed her on the forehead.

"Safe, Hagen, thanks to these whom you threaten with that great blade of yours."

"All Horder is up in arms, child. Word was brought to me that you were a captive of the Yotuns."

"And so I was, so Arnulf was. But these strangers, who come I know not whither, slew the savage band with their bare hands and rescued us. You must thank them, Hagen."

He glanced at us, but continued to speak with her: "How came they to take you, Gerda? Heimdal swore that you did not pass the gate."

"Nor did I, so far as I know. I was spinning in my jungfrúbúr, alone, when in an eye blink I was stifled under a crowd of odorous Yotuns—"

Eric's hand clamped on my shoulder, his voice was hoarse in my ear: "The jungfrúbúr; she said the jungfrúbúr."

"Shut up!" I grunted. "I want to hear this."

"—gagged, bound, blindfolded before I could call for help. They carried me off, nor could I tell anything of our road till the blinds and gag were removed and I found myself in yonder pit. They lashed me to a pillar, Hagen, with their foul hands." She shuddered. "They gibed at me, telling how they soon would bring you to join me."

Hadding was still whispering agitatedly: "She was alone in the jungfrúbúr, Carl. Isn't that what she said?"

"Yes." I shrugged. "But what's the excitement about that?"

"Don't you see? The jungfrúbúr is the house of the single women. She isn't married, then. She isn't his wife!"

Hagen's cheeks had flushed a dull red, and his eyes were troubled. "—must have found a new way into Horder. Heimdal says none but Arnulf has passed the gate, and Heimdal is to be trusted. Peril is afoot, Gerda; we must hasten back. They may even dare a surprise attack in force."

He straightened and turned to the gnomes, who had halted, resting their spears in a roughly military fashion. "Leif," he thundered, and a tiny warrior raised his shaft in salute. "Go in all haste with your hereder to assist Heimdal at the gate. Be alert, vigilant."

Leif bowed, shrilled a command, and, with disciplined haste, a hundred pygmies trotted off in the direction from which they had come, their little shields clanking against their mail.

"Haakon, Sverre!" The giant Northman's voice fairly crackled. "Speed to Horder-tun. Take my command to Harald to man and launch the dragon ships and guard the borders of the inner sea. Bid all the Horder folk to arm and stand ready for my next commands. Go by separate routes."

This order, too, was smartly executed. Further crisp commands came from the bearded Viking, with a certitude that showed him to be a master of the military art. In a few minutes the dwarf detachments had taken up their posts, flanking parties to right and left, a strong detail far behind, an advance guard in skirmish formation ahead, and the main force compactly surrounding Hagen, Gerda, and ourselves.

At a word from his towering chief, Rolf, the trumpeter, wound a call on his horn, and the army—it was no less—was on the move.

Hagen now turned to us. "I am somewhat lacking in courtesy to you," he boomed, "but other matters pressed. The gratitude of the Horder folk, and my own, shall be fittingly given when I have disposed of those insolent savages."

Eric bowed. "We merit no thanks." Somehow his voice had taken on a new sonorousness, his bearing a new dignity. "So short a struggle did not warm our blood."

"Spoken like a true Viking! And your appearance, too, is Norse of the pure blood, though I don't recognize your manner of dress. But your companion, he is short and dark—of the Gaedhill, no doubt. Great fighters they, too. I remember one battle we had with them at Dyfflin, when five thousand Viking souls were taken to Valhalla by the Valkyries before the field was won. Of what fylke are you? Egder, perhaps, or Raumer, where I have never been?"

Eric looked puzzled. "Neither am I Norse nor my friend Irish. We are Americans both."

It was Hagen's turn to wrinkle his brow. "Americans! I know no such nation. In the south, perchance?"

Hadding muttered an aside to me: "There's something queer here. We'll have to step carefully." Then aloud in the ancient language: "You have heard tell of Vinland and Markland?"

The other's face cleared at these appellations of fabled Viking settlements in the western hemisphere. "Good cause have I to know those names. It was somewhere near Markland that Njord spewed me out after Surtur had rejected me, somewhere near Markland I found what I thought was the way to Asgard, and descended, still weak from my wounds, seeking Odin's hall."

My scalp prickled. The man was talking as if it were he who had engraved the rune far above, yet that had been done a thousand years before. It wasn't possible that—

I saw the skin tighten along Eric's jaw. Had the same thought occurred to him? But Hagen was looking at him expectantly as we strode along.

"You have been long gone from the world," Hadding ventured, pumping him. "And many strange things have happened since."

The blue eyes under the golden helmet brooded. "Aye, long it is since I saw the sun—But we come to the gate," he broke off.

ABSORBED in the conversation, I had not noticed that the roof

of the cavern had lifted, or we descended, so that instead of the

dense thicket of columns through which our march had begun there

were serried ranks of tall, conical stalagmites along the floor,

and above a vast ceiling of thick-crowded stone icicles. From far

to the left came the dim roar of the stream whose origin was in

the sea above. Ahead of us the gnomes were scrambling down a

steep declivity.

We followed, and suddenly were up against a high rock face, a grim, gray barrier of granite along which the Horder folk were ranging themselves in long files. Coming toward us I recognized Leif, commander of the hereder, or company, Hagen had dispatched ahead.

"All is quiet, Jarl Hagen," he shrilled in the very small voice of all the little men. "No one has attempted the gate save Haakon and Sverre, your messengers."

I looked for this gate of which they spoke, but the rock wall loomed vertically above us, rising higher and higher till it met the fringed roof of the cave. To left and right it stretched to a distance I could only guess at, and there was not the slightest break in its blank grimness.

"I'll be blessed if I can see any gate," I grunted to Eric. "There doesn't seem to be any way of going on."

Hagen advanced close to the cliff, however, and did a curious thing. He pulled the shield from his arm and placed it on the ground, concave side up, balancing it carefully on the pointed boss at the center of its outer face. Then he stepped back from it, arm's length, and tapped it with the flat of his sword.

The buckler, delicately balanced as it was, hardly dipped at his deft touch. But instantly a gong-like note welled from it, a deep, booming tone that did not die away, but swelled evenly till the whole cavern seemed to be filled with the sound.

"Carl! Look at that! Look at the rock!"

Eric's ejaculation pulled my eyes away from the vibrating shield. I saw that a section of the granite wall was sinking, slowly sinking, into the ground. Ten feet high, and five across, an aperture appeared, gaping black and forbidding. There was an earth-shaking thud, and the top of the dropping section was level with the ground. Across the opening an almost invisible gossamer curtain hung, a fine web that pulsated in slow undulations, rhythmically. There was something indescribably menacing about it, something obscenely alive.

"Good Lord!" I muttered to Eric. "What on earth is that?"

I spoke in English, but the girl must have sensed my meaning, for she said something in an undertone to Hagen, and, when he nodded in assent, picked up a rock fragment and tossed it against the web. There was a lightning-swift flash across the opening, a metallic clang. Along the cave floor at the base of the veil a long white line of powdered stone had suddenly appeared. I shuddered to think of that flashing knife slicing down through a human body.

"Pleasant trap, that!" I exclaimed. "Even if some one stole a shield and got the door open they wouldn't get far!"

At a gesture from Hagen, Rolf stood spraddle-legged in front of that devilish curtain and blew a fanfare on his ornate horn. From somewhere within another horn answered him.

"Open to the Great One!" he shrilled. "Open to the Jarl Hagen, O Heimdal, guardian of the gate." And from the darkness a thin voice came: "The gate opens to the Great One that he may enter his fylke or Horder."

The spidery web wavered and drew aside. Hagen advanced, with Gerda at his side, and we followed. Almost immediately we were in pitch darkness. No, not quite. Ahead there was a glimmer of light, a formless nimbus at first. It brightened and grew more definite in outline, and I realized with a start that the glow came from Hagen himself, from his face, his hands, his bare knees.

The patter of many little feet sounded from behind, and, turning, I saw that the army of dwarfs was following us; saw, too, that each of them was glowing with the same strange phosphorescence that made of their ruler an uncanny wraith.

By the light they emitted I saw that we were progressing through a narrow tunnel in virgin rock, an artificial tunnel, for the marks of tools were plain. And the millions of tons of stone and earth that were overhead seemed to weigh down upon me, to smother me by its very ponderousness. Out in the cavern there had been at least spaciousness; here I seemed to be in a living grave. Then the tunnel twisted, an oblong of light appeared ahead. Silhouetted against it were the forms of Hagen and Gerda. We were through.

I blinked, gasped. As far as the eye could reach, there stretched before me a rolling, grassy plain, checkered by planted fields. A dirt road began at our feet and wound to the middle distance where I could make out a cluster of tiny houses built of logs and thatch-roofed.

Beyond this a hill lifted, atop which were three structures that even from here appeared gigantic by contrast with the doll's village below them. To the left the glinting, green waves of a sea stretched to a misty horizon.

My first thought was that we had come out into the open, into some hidden land that the world had never discovered. Then I saw Eric looking up, and I followed the direction of his gaze, expecting to see the sun in a blue sky. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

Springing out from the cliff, five hundred feet or more above us, a great rocky dome arched up and away till it was lost in the same gray mists that limited the sea. We were still underground, in some vast bubble fashioned while the earth was yet a yeasty, seething mass. But grass and wheat needed the sun's radiance—the air was lucent with a soft white light—

"I can't understand it, Carl."

Hagen, who had stepped aside with us to permit the dwarf regiments to pass, boomed a command, and the tiny cohorts halted. "There is something wrong," he growled to the girl. "Where is the guard that should be at the inner gate? Where are the dragon ships?"

She had not time to reply when the light began to fade. A murmur passed through the ranks, a tremor of fear, and Hagen ripped out an oath: "By Thor! The flame—the flame darkens before its time!"

What he meant, I did not know, but there was something in his tone that sent a chill of dread coursing through me. An uncanny gray shadow seemed to be dropping over the land, the air was growing colder by the second. Thin screams came from the staring dwarfs, and Gerda's face paled.

"It cannot be," she whispered. "The flame—'tis life itself."

From somewhere in the ranks a voice shrieked: "The strangers are doing this! The strangers are darkening the flame!"

THE hysteria ran through the mob like wildfire. "They are

Yotuns! Spies! They darken the flame! Kill them! Kill! Kill!"

The formations broke, and the gnomes were seething all around us, their faces contorted with fear and hate, their spears an upraised, tossing sea.

I leaped backward to get the protection of the wall behind my back. Eric joined me, touching shoulders. A spear flashed through the air. Only a swerve of my head avoided its barb. Another struck the stone, wide of its mark. But in a few seconds they would fill the air with a storm of death.

"Stay them, Hagen! Stay them!" Gerda's scream cut through the tumult, and with it she leaped to us, was in front of us, arms outstretched, quivering. "Is this the gratitude of the Horder folk, that you would slay my saviors without a chance for defense?"

The spears could not reach us without harming the girl, and even in their frenzy the pygmies held back their arms. But the shrill cries kept on: "Slay the darkeners of the flame! Kill the Yotun spies!"

Hagen's bellow drowned them out. "Silence, Horder folk!" His great sword was out of its scabbard. "Mine is the right to vengeance on the darkeners of the flame!"

He twisted to us, and his face was black with wrath, his eyes bloodshot. "Stand aside, Gerda! Theirs was but a trick to pass the gate. Yotuns they are, and sorcerers who must die ere the flame dies. Their lives or ours—there is no choice!"

An animal-like squealing greeted this from the tossing, rabid mob: "Kill them, O Jarl, or we perish. See, the dark is upon us."

Hagen cast a swift look over his shoulder, and though the fierceness of his expression did not relax, a furtive fear peered from his eyes. The shadow had deepened to a murky twilight, the sea was a leaden gray, and all color had drained from the meadows. He twisted back to us and roared again: "Stand aside, woman, before it is too late!"

"My life before theirs," she replied, tossing her head. I heard a sob catch in her throat. "Is this Norse justice? I demand for them trial before the lagthing, or holmgang."

Her defiance checked the Viking. "No stranger may be heard before the lagthing. But trial by the sword may—"

"May be demanded only by a man of Horder, whether for himself or an outlander." This was little Rolf speaking.

"And am I not of the Horder folk, little man?" Gerda lashed out at him. "I demand holmgang for the strangers."

Hagen, however, was sure of himself again. "One of the Horder folk you are," he thundered. "But not a man. Stand aside!"

"Jarl Hagen! Jarl Hagen! I am a man of the Horder folk, and I demand holmgang for the strangers. I, Arnulf, herse of the outer marches."

The Viking threw up his hand. "They have gone mad. But holmgang it must be, having been demanded. Holmgang it must be by the law of Horder. I choose the yellow-haired one to fight for both, and by the one eye of Balder—"

He was interrupted by a shout from the outskirts of the throng: "Sverre comes! Sverre comes, Jarl Hagen, sorely wounded!"

Hagen whirled. Staggering along the brown road was one of the tiny messengers he had dispatched to arouse Horder, his face a bloody mask, his spear a shattered stump, his shield gone, and arrows hanging from his mail, his legs, his arms. A way opened for him through the mob, and he reeled to Hagen's feet.

"The flame!" he gasped. "Yotuns—darkening it—hundreds of them—sunk dragon ships—Harald killed—Horder folk massacred—" A great gout of blood spurted from his mouth, drenching his tiny figure. "Hurry—or too late—" bubbled through it. He crumpled slowly to the ground, quivered, and lay still.

"Arnulf! The prisoners are yours to guard with your bereder!" Hagen snapped. "Your lives are forfeit if they escape. The rest of you follow me to save the flame." There was no mistaking the strength, the command in his voice, no denying it. "Forward! Forward, men of Horder!"

THE wild mob was an army again, was streaming across the gloomy landscape at the double quick in ranged hereders. And at their head was Jarl Hagen, a gigantic figure of vengeance, glowing in the now deep dusk with the uncanny luminescence of these strange people.

We stood staring after them, Eric and I, the Lady Gerda, Arnulf, and the hundred dwarfs of his company.

Hadding was the first to recover speech. "We thank you, Lady Gerda, for our lives."

She looked up at him, and her eyes were moist jewels. Her white hand was at her breast, and the slow blood mounted to her white cheeks. "I but paid my debt," she breathed. "Besides, I know you are no Yotun, no sorcerer."

Arnulf interrupted: "Your lives are not saved, strangers, but lengthened for a tiny space. Jarl Hagen's mastery of the sword assures that. Nevertheless, Lady Gerda, we must go at once to the Taarn, where the prisoners will be safe till Jarl Hagen returns for the holmgang, and where we can defend you with some chance of success should, Odin forfend, the Great One be defeated."

She nodded. "That will be best."

The herse piped an order to his command. They formed a hollow square about us with well-trained precision. Their spears were slanted outward, their shields upraised and overlapping edge to edge. With set faces and fierce eyes, they presented a truly formidable appearance. Arnulf pushed through the ranks to their head, snapped another command, and we were trotting along the road, fast as the pygmies' legs could move.

The progressive fading of light had ceased just on the point of complete darkness, but a pall of dread blanketed the countryside. So unreal, so nightmarish was the eerie luminescence that I seemed to be moving in a phantasy, and all emotion fled, so that I was conscious only of a stolid, uncurious acceptance of what was to come.

I had said nothing since we debauched from the gateway tunnel, could say nothing now. Nor was either of my full-size companions any more vocal, though I suspected their silence to proceed from a different cause. Even as they ran, their heads were turned to one another, as if loath to loose even the tie of sight.

A high tower appeared from behind an undulation of the plain; round, and fashioned of hewn-stone blocks. One or two slitted windows pierced the thick walls, and a heavy, iron-riveted door was ajar. It reminded me of something I had seen before—then I remembered. Longfellow's Round Tower at Newport! It was an exact counterpart. We made directly for it.

With the door closed, only a little light seeped into the lower room of the tower, just enough that I could make out Gerda and Eric very dimly. Through the wall we could hear the rattle of spears, and knew that Arnulf's men were drawn up without to guard us.

"Who are you?" The girl's voice broke the silence. "Whence do you come?"

"We come from the world above, my lady," Eric replied.

"The world above?" There was puzzlement in her tones, and something else. "Then there is a world other than Horder and the outer cavern; a world where all men are giants like you and Hagen and me, where there are other women, where there is a great round fire in a distant blue dome instead of a leaping flame."

"That there is. A beautiful world!" Eric's tone was tender, answering the yearning in Gerda's.

"I have dreamed of such a world, longed for it. But when I ask Hagen about it, he laughs bitterly and evades my questioning. 'Horder is your world, child,' he says. 'For always. Give up that silly dream of yours.'" A repressed sob roughened the richness of her voice. She paused a moment, went on: "And now you come from there, come as the flame is dying. Oh, Eric Hadding, will you take me with you when you return?"

"If ever we do return. We came hither, my lady, by a passage through which there is no way back."

"But there must be a way to the upper world. There is, I tell you. The Yotuns know it. Arnulf has brought me flowers he captured from them, and little animals such as we know not here in Horder, nor do they come from the outer cavern. The well by which Hagen came is forever blocked by the artifice of the Horder artisans, but there is another passage!"

A thrill of hope ran through me. "Did you hear that?" I cried. "Eric, there's a way out, and we'll find it!"

"How, Carl? We're prisoners here, and even if those fellows are pint size, we can hardly fight our way through them unarmed. Certainly not if we take the girl with us, and I'm not leaving her behind."

"I suppose not. You're hard hit."

He ignored that. "At any rate, I want to find out more about this set-up. I don't understand it, and I'm going to before I think about getting out." He turned to Gerda, cutting off any further argument from me. "What is this flame of which you all speak so reverently?"

"The living flame?" Awe crept into her voice. "The living flame that is life for Horder? It—But come, and perhaps I can show you."

She fumbled to the center of the round room, found a vertical ladder that sagged under our weight. We climbed through dimness to the tower top. A window here was slightly wider than that below. She peered through it.

"The flame still lives. But it is dim, dim."

FROM this height we could see over a low shoulder of the

hill. Beyond, not a half mile from us, there was what seemed a

pool of white fire above which leaped a lambent flame. There was

a colonnade of pillars about it, pillars that towered a hundred

feet from a circular platform to which broad steps rose, and in

the open space about it there was a confused, struggling mass.

Light glinted on the pygmies' shields, tossing in combat. I saw a

cloud of arrows rise from a clumped knot of Beathics. I could

make out Hagen's tall figure, surrounded by savages, his long

sword sweeping, sweeping in an almost rhythmic whirl of

destruction.

"See, the flame is but the height of a Horder man, and it should ride far above the columns. If it fall lower, Horder falls."

I could understand that. I realized that this was the sun of this strange world, that Hagen and his dwarfs were fighting for its protection as we should fight in desperation an enemy threatening to blot out our sun.

"But what is it, Gerda?" Eric pressed her. "How is it fed?"

"None feeds it, nor is it fire such as can be fed. Though it has no heat, it warms the land. Sometimes it sinks low as it does now through no external cause, and during that time of dark one may sink his body in its pool, and, doing so, gain eternal life. This all the folk have done before the oldest saga, and Hagen."

"Then—you mean—they live forever?"

"Forever, unless killed by wounds or accident."

"But that seems impossible."

"Eric, I shouldn't say that," I broke in. "Remember, we don't know the secret of life, or why it seems to have an inevitable end. The latest theory is that it is a form of energy, and that flame seems to be some radioactive emanation. Perhaps it so impregnates the tissues of those who bathe in it that their natural degeneration is halted, and if this is so, eternal life would naturally follow. Scientifically, such a theory is not an impossibility."

"God, Carl! Then it's the fountain of youth, the fabled fountain that was the goal of so many searchers in the early days." And then to Gerda: "Hagen—he has been here—how long?"

"So long memory can count not the time. He descended, the sagas say, through a well whence now plunges the stream that feeds the sea."

"But that must have been centuries ago."

"Centuries? I know not the word. But if it mean a time that is long, then it cannot be too long to measure the space Hagen has ruled Horder. The memory of the little folk is dim as to what was before that, save that they were driven from Horder by the Yotuns, and that it was Hagen who led them back to the pleasant land and drove the foul ones to exile in the outer cavern. The sagas say how the Great One taught them the ways of the Northland, that is but a name to any save Hagen himself; how he taught them to forge brynnies, and swords, and dragon ships, to erect houses, to till the land."

A faint howling came from outside, and Gerda darted back to the window. "Oh, the Horder folk are clustering about Hagen. They are gathering for a final attack. And they are so few, so pitifully few." She stared out, her hands tightening on the sill.

Eric rattled phrases to me: "Carl, it checks. Hagen said things that puzzled me out there, things that showed he still thinks in terms of the world as it was known to the Vikings a thousand years ago. You remember he spoke of fighting the Gaedhill—the Irish—at Dyfflin, which was the Norse name for Dublin. He wanted to know if I came from Egder or Raumer, districts of old Norway that lost those names long ago.

"America was a strange word to him, but Vinland and Markland were familiar—the appellations of Norse settlements on this coast whose traces have vanished for centuries. I thought it all was a matter of tradition, though he talked as if they were personal experiences. Now I realize they were."

"But that would mean he is a thousand years old."

"Exactly! Miraculous, but all the evidence points to its being true. And the Horder folk, the dwarfs, must be older still. Carl, in every northern land there are legends of the little folk, dwellers underground, trolls, elves, gnomes, leprechauns; they have many names, but their qualities, their appearance, is always the same. Perhaps these are the last remnant of the little folk, this Horder cavern their last retreat."

"And the savages?"

"They, too, are eternal. They were in possession of this land when Hagen came down the shaft; undoubtedly they, too, bathed in the glowing pool. I remember now that the being I chased up above also seemed to glow in the dark."

"Then they do visit the upper world."

"Yes! That, too, checks. They know the way out. We'll find it and get back, taking Gerda with us."

I stirred uneasily. "Eric, you're in love with her." I could speak bluntly to this friend of years.

"I am, Carl," he admitted. "When we return to the normal world, I hope to persuade her to become my wife."

"But look, Eric; she, too, must be—ancient. Apparently twenty, but really—who knows—a thousand years old, perhaps."

His hand dropped from my arm where it had been, and he took a slow step backward. "My God!" he groaned. "No!"

"Yes, Eric. She must have come here before the shaft was closed, since she knows of no other passage. And that was—at least three hundred years ago to our definite knowledge."

Even in the vague light I could see the stricken look on his countenance.

"But—but she is so young, so beautiful."

"Held that way eternally by the flame. And if you should marry her, she will remain twenty while you grow wrinkled and old; twenty when you are bent and toothless and cackling with senility. Forget your love for her, old man. It's unthinkable!"

"But, Carl—"

"They're winning." There was a hysterical edge to the triumph in Gerda's cry. "Oh, come here quickly! Look! They are defeating the Yotuns, are driving them from the flame."

WE swung to the lookout. It was true. The dwarfs had forced a

way between the savages and the flame. In a thin line, shields

overlapping to form an iron wall, they were pressing steadily

forward against a chaotic but still desperately fighting mass of

Yotuns. Hagen was battling just ahead of the pygmies, bellowing

in a berserk rage, his sword making a blurred ring of steel about

him.

The Beathics broke and were a shrieking, gabbling, defeated mob across the darkened land. Fast as they might, the Horder warriors pursued them, shrilling victory, but the longer-legged savages outdistanced them easily.

Hagen alone could reach them, his helmet gone, his shield discarded, his long curls streaming back of his great head, he harried the aborigines, thrusting, hacking at their fleeing backs, strewing them in a long trail of writhing, bloody bodies.

"Wonder why they don't make for the gate!" Eric exclaimed.

"Arnulf's men would cut them off here, and there is a guard on the other side of the tunnel."

"They're not scattering; they seem to have a definite objective. They're making for the sea. But there are no boats there; are they going to throw themselves in to drown?"

"So it appears. Why don't they surrender?"

"No use. Norsemen take no prisoners. You remember Arnulf back there."

"Eric! They didn't come in through the gate. They have some other way. Look! What's that long, dark mass humping out of the water just offshore?"

"Looks like a whale, but that's impossible. Jumping Jupiter! They're diving into the water right alongside it!"

The last remaining savage vanished beneath the surface, and Hagen, straddle-legged on the shore, howled in baffled rage. Then suddenly the dark mass was moving. It slid slowly away from the bank, sinking, was gone under the heaving waters.

"Like a submarine," I grunted. Then a thought struck me, and I addressed the girl in my halting version of the old Norse:

"Lady Gerda, how deep are those waters?"

"Twice the height of Hagen at their deepest."

"And it is fed by the river in the outer cavern?"

"That is so."

"Eric! That's how they got in! That's a diving bell, dry inside. They dived under the barrier wall with the stream's current, built the thing just inside, unobserved, and used it for their raids, first to capture Gerda and lure the bulk of the army outside, then to make their attack on those left behind and on the flame."

"He comes!" Gerda was leaning far out of the casement. "He comes! Hagen comes! Oh, he is bleeding, wounded! I must tend his hurts." She came in, vanished down the ladder.

We found Gerda binding Hagen's wounds with strips torn from the hem of her robe. He glowered when he saw us, but continued talking to her. "—found that the foul ones were filling the pool of the flame with earth and stones, quenching it. 'Twill be but short work to restore its full power. But they have slain ten bereder of men, and all the dragon ships are sunk. The ships can be replaced, but the men—"

He made a weary gesture of his hand.

"You have saved Horder; console yourself with that." She patted the last bandage in place.

"They fought bravely and well, my little warriors." His face softened. "Truly they have not forgotten what I taught them so long ago, when first we drove the Yotuns from this pleasant land.

"Arnulf!" he called.

"Here, Great One!"

"There will be a thing at the skaale, and a feast to follow. Bid all be prepared. Send the word forth."

"It shall be done, Jarl Hagen. What of the prisoners?"

"The Yotun spies? Yourself have demanded a holmgang for them. Well, we shall hold it at the thing. 'Twill not take long, and will whet our palates for the feast. Meantime, keep them here."

He went off, Gerda with him.

Arnulf motioned us back within the tower. "You will have a chance to prove what you can do against the Great One himself. The Yotuns are easy prey; even we Horder folk can spill their brains."

FOR an hour we had watched through the slit-like aperture as the light grew brighter, till now it was again as bright without as day would have been above. Evidently the flame had not been irreparably damaged. Eric squatted in a corner, brooding, and I kept silent, sensing his emotional turmoil. I had said my say, another word from me and he might, through sheer obduracy, make the decision I dreaded.

And it was doubtful whether there would be any decision for him to make. The holmgang was ahead of us, the deadly sword combat by which he was to prove our innocence, battle for our release. Either he or Hagen must die; that was the heroic rule of the ordeal. Hadding had been on the fencing team at the U, but would he be able to hold his own against Hagen, skilled in the arts of war, taller, more powerful? True, Hagen must be fatigued, weakened by his wounds. But these had been merely superficial, and doubtless the bath of the flame had endowed him with a supernormal recuperative power.

The door jarred open, and Arnulf's thin voice said: "All is prepared. Come!" We rose and moved out into the open. The Lilliputian company closed about us in their hollow square, and once more we were marching across those paradoxically green fields in the earth's bowels.

We climbed the hill, arrived at the largest building on its summit. This was a great edifice solidly constructed of huge timbers. The long side wall was windowless, but near one end there was a tall door, over which a well-carved simulacrum of a dragon's head watched us with beady eyes of some black, semiprecious stone.

Rolf stood before the door in full panoply. As we neared, he blew his horn, and the great door swung open. He wheeled and strutted through. We followed.

"Wait here," he said, and disappeared through a leather-curtained doorway.

We were in a small chamber. "This is the forstua," Eric said. "The entrance vestibule to the skaale."

"And what on earth is a skaale?" We were both trying to keep our thoughts from the ordeal ahead, the test of whether we were to live or die.

"The town hall of a Viking village, where the local assembly, the thing met, and where their great feasts were held. I've lectured on them many times, but I never thought I should stand in one. Next to this room is another small one, the kleve, a sort of armory, and they both open into the great meeting hall."

"What—" But Rolf was through the curtain again, staggering under the weight of a sword longer than he was tall. "The Great One sends you a blade to match his own. But mail he has not to fit you, so he has doffed his own."

Eric took the weapon from him, made it whistle through the air. "'Tis of true balance," he said calmly. "I am ready."

"Your thrall will be permitted to watch the combat. Arnulf, conduct him within."

"Good luck, old man!" I gripped Eric's hand, then turned to follow Arnulf. Though I was heavy-hearted with apprehension, a certain pride of race made me assume a nonchalant, carefree swagger. I wasn't going to let these little fellows know how scared I was.

I entered one end of a great, oblong hall, lighted by fires along the center of the floor, their smoke escaping through a blackened hole in the high roof. The dark walls were hung with shields, weapons, smudged tapestries, and all around them were long, low benches, broken at the middle of each side, and the rear, by raised platforms on which were high chairs. The benches were crowded with tiny warriors, each plainly showing the marks of the battle with the Beathics.

The high seat at my right, flanked by pillars supporting a canopy of green satin, was occupied by Jarl Hagen, resplendent in a scarlet costume of richly embroidered silk. Opposite was Gerda, her white robe seeming to glow in the flickering firelight. The chair at the opposite end of the hall was vacant, and to this Arnulf conducted me.

I had barely seated myself when Rolf appeared. His omnipresent horn hawked, and then Eric was coming in, poised, confident, smiling a little. At the same time Hagen descended from his dais, drawing his weapon from its jeweled scabbard.

"Hear! Thing of the Horder folk!" Rolf's proclamation was a thread of sound in the expectant hush. "Eric Hadding, outlander, being accused as a Yotun spy by Hagen the Great One. Arnulf of the Outer Cavern has demanded trial by holmgang on his behalf. Jarl Hagen, do you persist in your accusation?"

The deep bellow of the Viking was oddly loud by contrast: "I do, and I am ready to prove my charge by my body and my sword."

"Eric Hadding, do you, on behalf of yourself and your thrall, deny that you are Yotuns and spies?"

"I do, and I am ready to prove my innocence by my body and my sword."

"Let the holmgang proceed to the death of accuser or accused. To the death of accused's thrall if the accuser be victorious."

ROLF stepped back. In a silence that was absolute, the two

tall, blond men approached each other with long, lithe strides.

They came within reach, and Hagen's sword lashed out, snakelike

in its swift strike. I caught my breath, but Eric was ready; the

stroke slid along his blade, the two hilts clashed. The duelists

stood there for a moment, straining, statue-like. Then the swords

disengaged, and they were in a whirl of action.

So swiftly did they feint, and parry, and strike, and parry once more, that it was difficult to follow the combat, impossible to describe it. The hall filled with a ringing clangor of metallic sound—the whirring swords were a blur of flashing steel. Hagen leaped in and out, Eric swayed and countered. Gerda leaned forward in her high seat, white faced, her lower lip caught under pearly teeth. Steel rasped and rang—the combatants' stertorous breathing rose loud in a sullen lull in the tumult—for a moment the weapons were engaged again in a straining deadlock—Hagen's wrist twisted, his blade flashed away, flashed again—slid past Eric's steel and caught in Hadding's shirt, ripping it from his torso, but never touching the bared flesh.

Eric jumped back. Sweat glistened on his skin, darkly tanned save where the odd-shaped birthmark showed red and distinct. Hagen swayed on tiptoe—sprang in again—catlike for all his bulk. The gleaming line of his sword slithered past Eric's hasty guard—the point was at his throat! And stopped there, just pressing the skin, while Hagen, suddenly immobile, stared at his opponent's chest.

So startled was Eric that he, too, froze, and Hagen ripped out chokingly: "Halt! Halt the holmgang!"

Eric blinked, coming out of the shadow of death. Then he smiled tauntingly. "What woman's whim stays the sword of Horder's champion?"

The other's face was livid. He pointed a trembling finger at Hadding's chest, at his birthmark. "That—that closed hand—is it painted there to mock me?"

Wonderingly, Eric responded. "Painted? No. It has stained my skin from birth. My father had it!"

"Your father!" Hagen gasped. He tore at the silk covering his own breast, ripped it away. "Look!"

On his bared skin, darkly purple, was a closed fist. A murmur ran through the hall, a curious shrilling of surprise.

Hagen looked down at it, looked again at Eric's. They were identical, save for the color. "This mark was branded on me by the Slavs when I was their prisoner. I returned to find my wife with child, she saw this, and when my son came from her womb he had the same stain on his infant skin. Soon after I sailed away to that last battle in the upper world I ever fought. Who are you? In Odin's name, who are you?"

"Not your son, Hagen. My father lives, and I know you are not he. Nor his father, who had the same stain, for I saw him buried. And his father's grave I have seen. But that one came from the Northland. Jarl Hagen, how long have you been here?"

The Viking's face twisted as if in agony. "How long? So long that I have lost track of time. So long that my bones should have been dirt, and grown into a tall tree, and rotted earth again were it not for the eternal life gained from the living flame. So long that I am weary of life and curse the day I bathed in the pool."

"A thousand years, Hagen?"

"Years?" He stood there, trembling, fumbling for thought. "Once that word had meaning for me. Aye. Perhaps a thousand years—I do not know. It may be."

"And do you think in all that time the face of the upper world has not changed? Do you think the son you left behind has not died, and his son, and his son's son, for generation upon generation?"

"Aye!" Hagen whispered. "I had not thought. It must be so." Then his voice rang out: "But that mark, that mark!"

"This mark is the sign of your blood, indelibly stamped on the fruit of your loins to the thirteenth generation."

IT took time for that to sink in, while Hagen stood there gray-faced, and the thronged hall was so quiet that the gnawing of a mouse beneath a bench grated loudly through the silence. My own brain reeled as I tried to realize that here in front of me, both living, stood two men whose births were a thousand years apart, yet in whose veins flowed the same blood.

And suddenly, gazing at them, I knew why Hagen's lineaments were familiar to me. Barring the beard and mustache, they were Eric's, Eric's in every feature. Somehow that made the thing real to me.

A long shudder went through the Norseman's body. Hagen's mouth worked, and then his booming tones rang through the hall. "Men of the Horder thing, I withdraw my charge against Eric Hadding and his thrall. None of my blood could be a Yotun spy!"

A great cheer went up. I started from my seat to where the two blond giants were clasping hands in a greeting across the ages, but Gerda reached them first.

"I'm so glad, so glad!" she cried, and her arms were around them, ancestor and descendant. She kissed Hagen, tears streaming from her eyes. "So glad for you, dear brother!" She twisted to Eric, kissed him. "And for you, dear savior!"

Hadding pulled his hand from Hagen's grip, and Gerda was folded in his embrace. She quivered closer. I heard his hoarse tones: "And I am so glad that I have found you, Gerda! Say you will never leave me again."

"Never, dear heart!" They were oblivious of their surroundings, of the cheering mob of mailed pygmies, of the thousand-year-old Jarl Hagen. I was suddenly cold.

"Good God, Eric! You can't do that," I choked. "You can't! She's ancient. Your ancestor! You can't!"

He looked up at me with bleak eyes, but he still held her tightly clasped. "What can I do, Carl? It's—it's beyond my strength to give her up."

In my distress I turned to the smiling Norseman. "Jarl Hagen, you must not permit this!"

He started. "Why should I forbid it?"

"How can these two mate—with such a gulf of years between them? It's unthinkable, horrible!"

Surprisingly, he threw his head back and roared with laughter. I gazed at him astounded. At last his mirth subsided. "But that is not true. Their years march together."

"She is your sister, ancient as you!"

He shook his head, amusement still crinkling, at the corners of his eyes, "Nay! She is my sister only by right of affection. And she has not the gift of eternal life, has never bathed in the flame."

"I do not understand."

"The Lady Gerda was a babe, a yearling, when first I saw her. Arnulf brought her to me. He had seen her in the hands of a Yotun savage, brought from the upper world with sundry other small animals by the passage they know, but whose secret we have never learned. He took her from them, and ever since she has lived here with us, the only female in all Horder land, beloved by all and loving all, but never one of us. As an infant, we would not bathe her in the flame to stay her as a puling babe, and afterward she would not."

"I knew it, Carl, I knew it." Eric's voice pealed out exultant. "She's coming back with us, coming back to the sun and the blue sky, I'll make up to her for all the lost years she has spent in this cavern."

"Coming back?" All my joy at this sudden turn of events drained away. "How? The only ones who know are the Yotuns, and we'll never get it out of them."

"We don't have to." His eyes danced. "I've figured it out."

"What!"

"Listen, Carl! The Horder folk are undoubtedly familiar with every inch of this inner cave, and they patrol the outer one, so that if the passage were there they would have found it. There's only one place left where it could be."

"Where's that?"

"Somewhere between. You remember we decided that they came into Horder through the entrance channel of the river. The dwarfs have never been under there, and it's plenty long enough to have an outlet to the upper air, judging by the length of the tunnel at the gate. I'll stake my life it's in there. And if they can get at it, we can, the same way—with a diving bell."

"Let's go!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.