RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

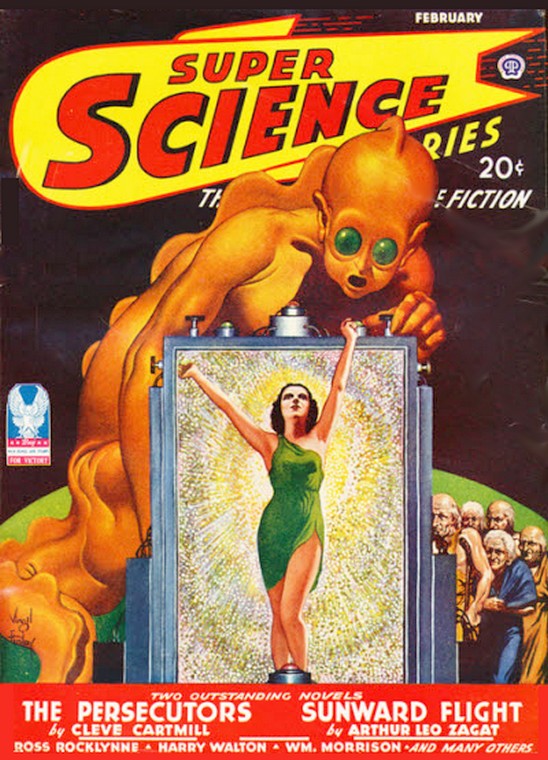

Super Science Stories, February 1943, with "Sunward Flight"

"Fear—the ancestral, abysmal fear of

the dark that no centuries of civilization

can quite expunge from Man's marrow—the crawling fear of things unseeable—

you will meet them in Sunward Flight. Are you big enough to take the trip?"

THE incessant noise of the crowd which had gathered on Whiteface Mountain rose to meet the roar of the furious combat over Lake Placid. An orange plane cut across the nose of a scarlet ship, escaping destruction by inches. The mask-helmeted and armored figures harnessed by aludur straps to the tip of each stubby wing leaned rigidly into the speed-gale. A woman screamed shrilly above the sound of the crowd. Princeton's Left Two caught the ball with a magnificent backstroke of his mallet and sent it whirring two miles back down the lake.

"That's polo, Toom Gillis," Rade Hallam shouted in my ear. "That's airpolo at the acme."

The dazzling play had averted a sure goal. The score was still Princeton—one, Rocketeer Training School—one, and the emerald flare that dropped from the referee's gyrocopter signaled that time had run out, that the extra chukker and the game would end at the next pause for score or out-of-bounds.

The helium-inflated ball, losing momentum, was beginning to rise to the level of the marker balloons. The R.T.S. goal-tender had come up-lake with the Red team's wild four-plane charge and not a machine was anywhere near the white sphere.

"No," my wife moaned, her fingers digging into my arm. "Not a tie, Toom."

"Look, Mona!" I flung out a pointing hand. "Look at that!"

Princeton's Number Two had looped over, was streaking across the sunset-flaming sky for the ball. It was clear away—No, by Saturn! A red plane—Three—appearing from nowhere, drove to fly off the orange.

The quarter-million humans packed on this hillside watched silently, breathlessly.

The two planes were long blurs, scarlet and orange, screaming toward a single apex. If either veered, he'd leave the other free to smash the ball down-lake for a Princeton score or back up-lake to where a Rocketeer forward was clear of the pack. If neither gave way they would collide—at four hundred miles per hour!

The nerve of one pilot must break.

Someone was pounding my back, voicelessly. The blows shook me, but I was not really aware of them. Mouth open, I was up there racing with those planes.

They were yards apart and neither had yet given signs of yielding. Suddenly the scarlet plane swerved—not left nor right but up! Up in an abrupt, incredible leap that let the orange pass far under.

And now the red plane dove for the ball—power-dove!

The cadet at its stick called gravity to aid the drive of his motor and outsped his equal-engined adversary by enough, in the quarter-mile still left, to regain the yardage his maneuver had cost him, and enough more to give his right wingman an eye-wink to catch the ball on his mallet-head and carry it down with him—steeply down to an inevitable crash!

"Antares!" I gasped. "That lad's a flyer."

Ten feet above the water the scarlet plane had pulled out of its dive. What's more, his harness straps denting his armor, the blood whirled from his brain by that terrific arc, Cadet Right Three still held the ball on his mallet.

The machine straightened, fled for the black and orange pylons towering from the upper margin of the long lake. Somehow that youngster on its wing had strength enough left, skill enough, to stroke the white sphere ahead, to stroke it again and again and send it skimming straight and true between the slim Princeton goals.

Rocket Cadets—two, Princeton—one, and the game was over.

IF someone had told me this morning that by mid-afternoon I

should be here in Adirondack Pleasure Park watching this

Intercollegiate Championship I'd have laughed in his face. The

Aldebaran was just in from Venus. As controlman I was due

to check her over, refuel her with hydrogen and oxygen and see to

her reprovisioning. Rade Hallam, her master rocketeer, was due to

make his report at the headquarters of the Interplanetary Board

of Control and get from the I.B.C.'s chartroom the latest dope on such

perils to astrogation as new meteor swarms, ether swirls and so

on. He had already started for there, but before I could leave

the home he shared with me and Mona, our radiophone had rung. It

was Rade.

"Stay there till I get back, Toom," he snapped, and shunted off.

He did not return till afternoon. I sensed at once a tension in him, a sternly repressed excitement.

"Well," I demanded, "what's it all about?"

Slender, erect, despite his graying hair and the thirteen stars that circled his Silver Sunburst, one for each year he'd conned the Spaceways, he looked at me almost as if he didn't see me.

"Snap out of it, Rade," I grinned. "Spill it."

"We're going to Placid to select a midshipman for the Aldebaran by the way the cadets shape up as they play."

"To select—Cygnus! Why can't you wait till their records come down to Newyork Spaceport next week? You're senior rocketeer of the fleet; you can have your pick. What's all the rush?"

His eyes, eagle-hooded in a gaunt, leather-skinned countenance, had rested for a moment on my face. "I can't explain." Then he had turned to Mona. "If you are coming with us, my dear, you had better hurry. We have just about enough time to make the start of the game."

FLOODLIGHTS came on to bathe the mountainside as the sunset

faded out of the sky. The crowd began to disperse from around us

as I worked my shoulders, trying to ease the ache in my back from

the pounding it had received.

"Oh, look here," someone said behind me. "I didn't realize I was hitting you." The speaker was heavy-jowled, heavily built, but sleek with good living. "I must apologize, Controlman."

"No apology necessary." He knew my grade by the single-starred Golden Sunburst on the black breast of my uniform. "I was plenty steamed up myself."

"It is kind of you to take it in that way, Mr.—"

"Gillis. Toom Gillis."

"Ah, yes. I have seen some fine reports on your work." The devil he had. "I am Gurd Bardin, Controlman." Leaping Leonids! He was Bardin of the I.B.C, one of the men who have absolute power over all ships traveling space and the men who con them. "If you are Gillis, I take it that this gentleman—" he gestured to Rade—"is Master Rocketeer Hallam."

"Correct," the latter acknowledged for himself, unsmiling.

"It is a pleasure to meet so famous a spaceman." Bardin's too-small eyes shifted to Mona. "This young lady—"

"Is my niece," Hallam said, "Mona Gillis."

As Mona acknowledged the introduction, I felt the cords in my neck grow taut. I do not usually resent men looking at my wife. Slimly graceful as a birch in her tight-fitting airsuit with its bright blue sash, hair a soft brown cloud about a pert-nosed, impudent small face, she is very pleasant to look at, and I am not selfish. But there was something in Bardin's gaze that rasped me.

A rumble of warming-up motors rose from the vast parking field at the base of Whiteface. "If you will excuse us, Mr. Bardin"—I interrupted some inanity he was addressing to Mona—"it is getting late and we shall be some time getting our plane out of that mess down there. We really ought to be moving along."

"But I was hoping for a chat with Master—Look here," Bardin interrupted himself. "Why don't you three join me aboard my stratoyacht, the Icarus, and hop over to Skyland and have dinner with me there?"

I blinked. From what I had heard of the resort atop Pikes Peak, dinner there was the experience of a lifetime—and one within reach only of the very rich. Mona's gray eyes lighted up.

"Thank you," Rade was saying. "We appreciate your invitation, sir, but we have promised to join friends at the Tavern of the Seven Pleiades."

Once more I blinked. Not only had we no such plans, but the Pleiades, as all the three peopled worlds know, is a tawdry dive hugging the boundary fence of Newyork Spaceport, a brawling hole in the wall not to be mentioned in the same breath with Skyland—except for one thing. Master rocketeer or grease-grimed tubeman, all who con the void are welcome there, but none other.

For all his wealth, Gurd Bardin could not set foot across its threshold.

I thought his nostrils pinched a little. I must have been mistaken, for he said, smilingly. "Some other time then." and ambled off to where a gleaming gyrocopter hovered, waiting on idling vanes for his signal.

"What was the idea, Rade?" I demanded as soon as the Icarus's tender had lifted out of earshot. "Why slap Bardin in the face with the Pleiades? Saturn! He was being damn nice to us."

"Curiously nice. Look you, Toom. Did it not occur to you as at variance with all you ever heard of Gurd Bardin that he should even mingle on equal terms with such a crowd as this, let alone put himself out to be genial to mere spacemen?"

My brow furrowed. "You mean that he is after—Look here, Rade! What's this secret you're nursing?"

"I told you that I cannot—What gave you the notion I have a secret?" Abruptly his eyes were trying to tell me something. "You've been scanning too many thriller filmags, Toom." My wrist chronometer—

Its many-dialed face glowed brighter in the brilliance of the floodlights than I'd ever seen it in the black dark.

"Fins, Rade." I managed what I hoped was a convincing chuckle, in spite of the chill little prickles that coursed my spine. "Lay off my filmags." That strange glow meant there was a listener-ray on us, picking up our every word. "Come on. Let's get started for the R.T.S. hangar before the cadets scatter."

STRAIGHT up out of the parking fields at Whiteface's base an

immense white shaft soared, brilliant as some columnar sun. From

this hub there radiated the broad, horizontal beams that mark and

illuminate the skylanes, each at its separate level, each its own

lambent hue.

The Northern Route was an icy blue, the Southern a warm, effulgent red. The sea-green Eastern lane was opposed by Westward's yellow of ripened wheat, while in between all the merging gradations of violet and purple, blue-green, green-yellow, yellow-red, sped to the minor compass points.

Along the spiraling spokes of this vast rainbow wheel the throngs streamed homeward—countless black midges in the vari-hued luminance. There were lumbering aerobuses and swift glider-trains, swank limouplanes, modest amphibians and racketing, rusted jalopies that should have been ruled off the traffic ways.

Close below our small but comfortably fitted amphibian, Lake Placid held a reflection of the darkling, ancient heights that encircle her, and in that brooding frame the shining glory of the modern sky.

"One thing," Rade Hallam remarked. "That final play of the game left us in no doubt as to which cadet to choose for the Albebaran's midshipman."

"Right," I agreed from my chair beside Mona's, aft in the little cabin. "Number Three is our man. I hope he's a senior."

"He is, Toom." Mona had her program open to the lineups. "Here's his name: Nat Marney, and his class is 2116, right enough."

"Good! That lad is smart as a whip, Rade. He has guts, too. The way he conceived that final play and executed it—He is far and away the best man on the team."

"No," Hallam disagreed. "The best man on the team, and for the ship, is Jan Lovett, Marney's right wingman. The pilot was magnificent, I grant you, but he had time to plan his play and accept its dangers. Lovett reacted instantaneously to a situation and a peril presented to him without warning. He had no time to think; he did the right thing instinctively, and the ability to do that is the quality a rocketeer needs most."

"I challenge that! If you analyze what the—"

"Hush, Toom," Mona interrupted. "Please hush. Listen."

Rade set our craft down, light as a kiss, on the lake's surface. It broke into a widening shimmer of liquid opalescence.

"Listen," Mona whispered again, her warm, soft hand stealing into mine.

We were roofed by an enormous rumble of motors, but here below an arboreal silence enfolded us. Somewhere there was the shrill, antiphonic chorus of cicadas and from beyond the low, black island that hid the R.T.S. hangar came the sound of young voices, singing the Rocketeer Cadet's Farewell Song:

All things end and so to ending come our golden college days.

Fading fast our youthful friendships, fading fast into the haze...

Now R.T.S. is nothing to me but a name. I've come up in the Craft the hard way, and myself have been case-hardened in the process, but an ache came into my throat as the minor, nostalgic strains floated across the jeweled water, and seemed to come into the cabin with me...

Soon we part, perhaps forever. Soon, oh brothers, we must part.

And the miles between will lengthen, swift as rocket's blazing dart.

Swift with spaceship's blazing dart.

The song was in the cabin. Rade Hallam was singing with those youngsters, low, and I think unaware, and it seemed to me that the lines which the years had marked on his gaunt, gray face smoothed out and that a peace came to him he had not known for a long, long time.

The refrain shifted to a more spirited cadence:

R.T.S. fore'er will bind us,

Brothers all.

And this pledge we leave behind us,

Each to all.

When you need us, we shall gather.

From the black void's farthest borders

We shall blast across the heavens

And shall rally to your call.

Brother! To your call we'll rally, one and all.

There was a bitterness in me that I was not, could never be, one of that fine brotherhood. We were silent a moment, and then the song began again:

All things end....

"Not us," Mona murmured. "Not the love that binds us, Toom. That will never end."

I turned to her. Her gray eyes smiled at me. She parted her lips to say something more—and vanished.

Not literally. My startled hands reached out and found her soft body in the blackness that had swallowed her, the darkness that blotted out the lake and the mountains and the rainbow sky, the absence of light so complete that it seemed to have weight against my eyes.

I could feel Mona, tensed in my arms, her heart beating against mine. I could smell the sweet perfume of her. I could taste the salt saliva of sudden fear on my tongue. I could hear Placid's little waves slapping the amphibian's hull, the R. T.S. seniors harmonizing their Farewell Song. Only my sight was gone. Panic struck at me. I'd gone blind—blind!

"What's happened?" Mona quavered. "Toom. What's happened to the light?"

I never heard, never shall hear again, words more welcome. As I relaxed, Hallam spoke, forward, as if to himself. "The queer thing is that I can't even see the glow from Toom's watch."

Queer indeed. Our coldlight tubes might have failed. Some black cloud might have blanketed our craft. But the less any other light, the brighter the chrono on my wrist should be glowing.

"Whatever it is, Rade, it's only right around us here or the cadets would not still be singing—That's the ticket!" My airman's sixth sense told me the amphibian had started to rise. "I was just going to suggest you lift us out of it."

"But I am not, Toom." Rade's voice was tight, strained. "I haven't touched the controls. We are being lifted by something outside the plane."

Mona whimpered a little at the back of her throat. A colloid pane scraped in its sash. Coolness came in from the window Hallam had opened, and the song of the cadets below.

"Yo-o-oh, Kaydets," he shouted. "To me, Kaydets. R.T.S. to—" A dull thud cut him off, the unmistakable dull thud of a body hitting the floor.

"Rade!" I cried. "Rade Hallam!" No answer, not even a groan. I released Mona, plunged forward. A stinging, fierce shock exploded in my brain.

I couldn't move. I couldn't utter a sound. I was frozen in a strange paralysis.

I still could hear. I heard the colloid Rade Hallam had opened scrape shut again. I heard the faint thrum of 'copter vanes, not ours, too far off. But I couldn't hear Mona.

That was the worst of it. No scream, no sound of struggle or fall came to me in that terrible dark as evidence that Mona was alive, that she was still in this plane.

I DID not need my airman's sense of changing altitudes to know

we were rising swiftly and more swiftly. My ears told me that.

The cadets' singing faded away beneath. The noises of the traffic

lanes beat at me—not from above though. From the left,

always from the left, and always a little above.

As the beams rayed out, spiraling from their white central shaft, we were spiraling too, threading the vacant reaches between them. That was a violation of the strictest law of the skylanes. Why did not some police plane, of the many that shepherded the home-flying swarms, intercept us?

It was unreasonable to suppose that they did not see us. Unless—I was fighting terror by forcing myself to think—unless we were as invisible to them as they were to us.

Nothing supernatural about that, I assured myself. Light is vibration, waves in the ether. I knew that sound waves could be blanked out, silenced by sound waves of the same frequency but opposite in phase. Why not light too?

How? How had this cloud of no-light been thrown about us? What of this strange, irresistible paralysis—A lurch of the deck threw me off my precarious balance, I sprawled, swore—heard myself swear!

I could speak aloud. I could thrust at the deck with hands suddenly alive again and shove myself up to my knees.

"Toom," Mona called out of the black.

"It's I, all right." I lurched aft to the sound of her voice.

"Oh. Toom! What has happened to us?"

"Mona." Her hands were icy as they met my groping ones. "Mona, honey. Are you all right?"

"Only scared." Small wonder. "But I'm worried—"

The craft lurched again, threw me across an arm of the chair beside hers. As I twisted, managed to fall into it, metal clanged ponderously somewhere outside, and the amphibian abruptly was steady, dead-feeling.

"Uncle Rade, Toom," Mona gasped. "He—"

"Is whole, hale and hearty," Rade said right above us in the lightless dark. "And not quite as bewildered as Mr. Gurd Bardin might think."

"Cygnus, Rade!" I protested. "You've got Bardin on the brain. What could he possibly have to do with this?"

"A great deal, Controlman Gillis." It was Gurd Bardin's own voice that answered me! "Everything, in fact." Light smashed my eyes, blinding.

I stood up, my hands fisting. The dazzle faded, but it was not Bardin I saw squeezing in through the hatch. It was a huge Martian, his seven-foot height stooped to our low ceil. I started for him, decided to halt.

The giant's lidless eyes peered at me out of his green-hued visage, with a mild, childlike interest, but he thrust his huge paw at me, and from it came a metallic, lethal glitter. He moved aside a little, uncovering the hatchway—and Bardin, standing apparently on air just outside, the deck cutting him off at the knees.

"I hope, Mr. Gillis," he smiled, "that your lovely wife was not too much startled by the unorthodox method by which I had Tala bring you here."

"Here," I repeated. "Where is here?"

"Some five miles above Mount Whiteface." Behind Bardin I now discerned another amphibian, much like our own, and beyond that a rivet-studded high wall of gleaming durasteel. "In the lifeplane bay of the Icarus."

"I'll be—" My tone perhaps, or the same unconscious movement that brought Rade's restraining hand to my arm, lifted Tala's paw again. The thing in it was a device of coils and insulated handle such as I had never before seen. Whatever the Martian held, it was undoubtedly a weapon, and was what had produced the frightful paralysis from which we had just been released.

"We turned down your invitation to come aboard, so you had us brought here anyway. Did anyone ever tell you there's a law in this hemisphere against abduction?"

"I think, Toom," Rade murmured. "Mr. Bardin has an idea he is above the law."

"Wrong, Master Hallam. Aboard the Icarus, I am the law."

"Interesting. But let us get to the point. What, Mr. Bardin, do you want of us?"

BARDIN stepped in over the hatch coaming. "What I want from

you is a very simple matter." I noticed that he was careful not

to get between us and the Martian's—shock-gun, I suppose,

is as good a name as any for it. "Suppose you answer for me the

question Controlman Gillis put to you on Whiteface, shortly

after I left you."

Rade's fingers drummed a tattoo on my biceps, but his face was inscrutable. "Since you heard him ask it, you must have heard my reply."

"What I heard was no reply. You did not deny having a secret. Discovering in some way that I had a listener-ray on you, you merely evaded admitting it. I want to know what it is. I want to know why the I. C. B. has been requested to release the Aldebaran from its regular Venus run and clear it for"—a satiric note crept into Bardin's tone—"'scientific exploration in Space.' I want to know why you are in such haste to complete your crew and so exacting in their qualifications."

He must have had listener-rays on us all day.

The black-eaved, small eyes were suddenly agate-hard, reptilian. "In short, my friend, I not only want, but intend to know what mission you were this morning asked to carry out by Hoi Tarsash."

My lips pursed to a soundless whistle. Hoi Tarsash was dean of Earth's delegation to the Supreme Council of the Triplanetary Federal Union. If he was concerned in this affair, it was big, something too big for me even to guess at.

"You seem to have a very efficient corps of spies," Rade Hallam murmured.

I shook off his hand, dropped into the seat beside Mona.

"My spies are efficient."

Tala's lidless gaze had followed me but he saw nothing to alarm him in the way I perched tensely on the edge of the durachrom chair, my right hand gripping its arm, my feet gathered under me.

"Unfortunately," Bardin continued, "the gaulite lining of Tarsash's consultation cubicle is opaque to the listener-ray."

"Unfortunately?"

"For you—unless you decide to tell me, of your free will, what passed between you."

A tiny muscle twitched under Rade's left eye; otherwise he was a black-uniformed, motionless statue.

"Think, Master Hallam. No one beside the five in this plane knows that you are aboard the Icarus, not even my crew. That, by the way, is why I have not yet had you taken from this plane. Once you have given me the information I require of you, you and your companions will be returned to the surface as secretly as you were brought here and not Hoi Tarsash nor anyone else will know you ever left it."

"In other words, I can safely betray the man who has trusted me."

"Precisely."

"And if I refuse?"

Bardin shrugged. "You are completely in my power, you and Toom Gillis and—" tiny light worms crawled in his eyes as they shifted meaningfully to Mona—"your lovely niece. I should regret, of course, but I am sure you understand me."

"Yes," Rade murmured, "I understand you perfectly." His face was a mask, but his hand, the one at the side toward me, closed into a fist.

At this signal my straightening legs pushed me up out of the chair. Keeping my grip on its arm, I whirled it around in front of me, swept it up and down again on Tala's lifting gun wrist.

Bone cracked. The glittering shock-gun arced from greenish fingers as I lunged forward and slammed my left fist into the throbbing spot at the base of the neck where the Martians' nerve system centers.

The giant's eyes glazed. He swayed, started to topple. I was spinning to help Rade who, in accord with the plan his fingers had telegraphed on my arm, had jumped for Bardin as I went for Tala—or should have. Dismayed, I saw him down on the deck, scrambling to hands and knees, saw Bardin diving out through the hatch. Hallam came erect, jammed against me in the narrow aperture. I saw that he grasped the shock-gun and pulled back to let him through—too late.

A durasteel door clanged across the bay.

"Got away," Rade panted as I leaped out and raced past him. "I've messed it, Toom. I—"

"It wasn't your fault, Uncle Rade." That was Mona, from the amphibian. "He couldn't help it, Toom. Bardin caught Tala's gun in midair, by the coils, luckily. Uncle wrenched it from his hand before he could reverse it, but Bardin tripped him and—"

"Okay," I grunted, reaching the door through which the man had escaped. "That's all gas through a rocket tube now." I dogged home its three ponderous clamps. "He's away, but he and his confounded crew will only need a torch and a couple of hours' time to get at us." I turned. "This bay's built and fitted like a spaceship airlock."

"Naturally, Toom." Hallam was bleak "If the Icarus should be pithed in the stratosphere, they'd have to use this as an airlock to give them time to get into the lifeplanes and batten them to retain normal air pressure. But—"

"Hold it, Rade. That gives me an idea." I scanned the durasteel-lined space about us, eagerly. "There ought to be..." It held still another amphibian beside ours and the one I had already seen, and the gyrotender—"There it is!"

What I looked for was in a far corner—a small compressed-air engine with a five-foot flywheel, a gleaming shaft slanting from it into the deck. "Look." I pointed to it. "Our troubles are over."

"You're right, Toom."

Rade understood me, of course. He would have thought of it himself, in another minute. There had to be an auxiliary gear in here to open the bay's portals if the main power unit failed. What's more, it had to be controllable from within the lifeplanes after they were loaded and hermetically battened, since the bay would lose all air the instant its great doors started to open.

BEFORE I could get back to them, Hallam and Mona were already in the plane that had been behind Bardin when I'd had that first startling sight of him. I climbed in after them.

"Hades!" I exclaimed. "What's all this?"

There was barely room for the three of us in the cabin, so filled was it with a welter of huge coil bus-bars, oddly shaped electronic bulbs. "Batten this hatch, Rade, while I see if I can make anything of this set-up."

Squeezing forward past Mona I was relieved when I found, above the standard flight controls, a panel of push-buttons, each labeled with a small etched plate. "Emergency Escape." I read the first to the left. "That's it, on the nail."

I thumbed the button thus marked, sank into the pilot's bucket seat. Somewhere behind me armatures clicked. Through the colloid on my left. I saw the air engine's flywheel waver, begin to spin.

"Check," I breathed, watching the wall of the bay split ahead of me, vertically from deck to rivet-studded ceil.

The others came up behind me as that rift widened. I let in the clutch, taxied to the opening, settled back to wait until it should be wide enough to let us through. Three yards, I estimated the plane would need, with its wings folded. Not much, but those huge leaves separated very slowly, sliding in their grooves.

Antares, they moved slowly!

I could feel the thumping of Mona's heart as she leaned against my back, watching. I could hear Hallam's deep breathing. I glanced down at my wrist. My chrono wasn't glowing.

"Look here, Rade," I said. "There's no listener-ray on us. Don't you think it's about time you let us in on this business?"

"Yes, Toom, I do." His hand pressed my shoulder. "But the secret is not mine. Look you, lad. This is no private feud between Bardin and Tarsash. It concerns—literally, not by any hyperbole—the peace, the happiness, the very lives of the peoples of the Earth, perhaps of the Three Worlds. We are fighting almost alone, almost hopelessly, to stave off a very—"

"Something's wrong," Mona broke in. "Something—Toom! Those doors have stopped moving."

"It just looks that way, honey, because you are so—" I cut off. She was right. I could see, out there before me, the blue-black sky of the upper altitudes. I could see more stars, but the aperture through which I saw them was no longer widening.

I twisted to the side colloid. The little engine was lifeless. I saw why.

From the wall beside it to the compressed-air tank that powered it, a bright blue thread angled down. Bardin's men could not burn a gap through the durasteel wall in time to prevent our escape, but they'd had just enough time to pierce it with the needle flame of their blowtorch, and the tank just our side of it, and to bleed the tank of the stored air that should be whirling those shining spokes.

"Evidently," Rade Hallam remarked, dryly, "Gurd Bardin likes our company too well to permit us to leave."

The opening in the wall of the Icarus's lifeplane bay mocked us with its view of the gold-dusted, free sky, a view too narrow by barely six inches.

I SHOVED up, twisted, got to the cabin hatch and slapped open

its clamp.

"Toom!" Mona gasped, "there's almost no air out there now." Her eyes were round, frightened. "What do you think you can do?"

"I can gain the six inches we need." Normal air pressure in here, the tenuous atmosphere of five miles above the Adirondacks on the other side, the door was held shut as firmly as though it were still dogged. "If I can get to that engine, I can—"

"Spin the flywheel by hand," Rade Hallam comprehended. "That will do it." He shoved in between me and the door edge, got a purchase. "We need you too, Mona."

She was haggard as she found a handhold.

"Be ready to slam it again," I warned, "so you don't lose too much air." It would be touch and go. "All together now. Heave!"

Hallam's neck corded. The muscles across my back roped. The door gave. I lurched against Rade, broke his hold and half-jumped, half was blown out through the aperture.

The hatch slammed shut behind me. I didn't look back as I sprinted across the bay, but I guessed the look that must be on the master rocketeer's face.

He'd known as well as I that the two left behind would not be able to open the hatch again against a pressure three barely had overcome. He'd maneuvered to beat me out and I'd tricked him, not because of any puerile heroics but because since only one of us could escape from the Icarus, it must be he.

He'd given me only a hint of the momentous issue to which the secret he shared only with Hoi Tarsash was the key, but that hint was enough. At whatever cost, it must be put beyond Gurd Bardin's reach.

I had gripped the flywheel's spokes, was bearing down on them, before I had to let go of the breath with which I'd filled my lungs the instant the hatch was yielding. Mouth wide, I pulled in the fierce cold of the upper sky—but no air. The cold struck into me. The flywheel started to turn. The unendurable cold pierced me, and there was no air to breathe. I was climbing the gleaming spokes with my hands, spokes that were already so cold they burned my hands, but the wheel was moving faster, always a little faster, and I dared to look at the bay's great portals.

They were moving again in their grooves. They were sliding apart, minutely as yet, but sliding.

My laboring lungs were a torture in my chest. The momentum of the wheel's ponderous rim came to my aid and the wheel spun faster still. Something sputtered past me, white-hot, coruscant, spattering the farther half of the whirling wheel. Sparks!

My head twisted to their source—the wall. The slim blue flame no longer angled down to the tank. It was burning a red-rimmed slash in the durasteel wall, a slit that grew inexorably toward me. The flame groped toward me, and to keep the wheel spinning I must stay here till it found me.

Keep the wheel spinning. Keep the wheel spinning. It was a kind of song within my head that was bound by an iron band. Keep the wheel spinning. I flailed hands at the blurred gleam of the wheel and the sparks spattered my uniform now, burned through and stung my skin. The wheel was blurred and the sky was blurred and the waiting plane was blurred against the sky. The sparks stung—

That fierce pain in my shoulder was no spark. It was the flame itself. I winced from it, sprawled, and had no strength to push up again to the flywheel that above me slowed, slowed—spun no longer.

I had failed.

"Sorry," I muttered. "Sorry, Mona, I tried." I strained to make out the plane. It was a blurred, vague shape that to my failing vision seemed to drift away from me.

It leaped through the portal I'd widened just six inches. In an instant of sight restored, I saw its wings unfold, catch the thin air. The plane was a fine, free shape against the gold-spangled sky—and was gone.

MY head dropped to my arm. My weary eyes closed, but the sting

of sparks shocked them open again, and the heat on the back of my

head as the blue flame slid downward.

Instinct, I suppose, no conscious will, shoved my hands and knees against deck steel and started me crawling from the flame, but once I started crawling I crept on. I must have kept going because, when a rumbling thunder brought me out of the fog into which I had sunk, I was almost to the lip of the Icarus's hatch.

Or was I? Was I not still on Whiteface, the game not over yet? A plane soared out there, scarlet in the fan of light from behind me, and on its fuselage was painted a huge Three.

It vanished. Of course. I hadn't seen it. It had been a phantom evoked by my dying brain. It—Something thudded behind me.

Tala, recovered, dropped from the amphibian's hatch. He saw me, lurched toward me, one clawed paw dangling from his broken wrist, the other reaching out to grab me.

I knew what an enraged Martian can do to a man—better the lip of the hatch and a clean death. I had only to drag myself a foot forward and go over, go down and down in the way a spaceman should die. My hands crawled to the edge, folded over it. My arms—I hadn't the strength. The poloplane was out there again, but I knew now it was only delirium, for on the tip of its stubbed wing a helmeted figure leaned rigid against aludur straps into the speed-gale.

Only in delirium could a plane stall as that plane seemed to, and sideslip toward me so that the dream-player seemed to hang level with me, seemed to lean in and catch my wrists and swing me out into the sky.

An enormous black bulk loomed over me, whirled under, was beside, then above me again. My mind cleared and for an instant and I knew that Tala mercifully had hurled me over the lip of the Icarus's hatch, that I was spinning down.

Then I blanked out.

"DIDN'T I tell you this new Verill airfoil would let us pull

stunts which for centuries the physicists have taught couldn't be

done?" It was a pleasant, young voice. "Maybe you'll trust my

flight-dynamics now, old fruit."

"Trust you now?" someone else drawled. "If I didn't trust you before, would I have walked out to that wingtip on your say-so? Not that I didn't have a bad sec or two while you had us in that three-thousand foot spin. I thought my arms would pull out of their sockets, hang-in' on to our ruddy friend here. He wasn't much help."

It didn't make sense. I should be dead instead of hearing a couple of youngsters chaff one another about Verill airfoils and flight-dynamics.

"Look," I asked weakly, opening my eyes. "Are you a couple of blasted angels, or am I lying cramped on the deck of a cabin not big enough for one full-sized human, let alone three?"

"Well, Mr. Gillis." The one with the shock of carrot hair grinned down at me. "We're no angels, though Nat Marney here might qualify for a denizen of the other place. How're you feelin'?"

"Plenty sore all over, and this burned shoulder is giving me hell, but who am I to complain?" I liked this big kid who stood straddled over me in singlet and shorts, and athlete's flat muscles sliding under his freckle-sprinkled skin. I ought to like him, he'd just saved my life at the very real risk of his own. "If that's Nat Marney, I imagine you must be Jan Lovett."

"Correct, sir," he drawled as he bent to help me rise. That seared shoulder was bad.

"Nat, say hello to the man."

The black-haired chap at the controls turned, said, "How do you do, sir." Sharper-featured than Lovett, shorter and far less brawny, he seemed more the studious type, but the corners of his eyes were crinkled too, with long squinting into the sky winds. "It is an honor to have you aboard."

"Believe it or not, the pleasure's mine." It would be, I knew, the wrong thing to thank them for what they'd done. "How in Saturn did you two happen to pop up so opportunely?"

"Well, sir," Lovett's soft drawl answered me as Marney turned back to his controls, "it wasn't precisely happenstance. You see, Nat and I have been together all through coll an' Trainin' School an' so we were—well, knowin' we're going to bust up in a week we kind of couldn't take singin' the Farewell Song with the rest of the class. We were squat-tin' together, not sayin' anything, on the wing of old Three here, when suddenly we heard the old 'Yoh Kaydets' from overhead."

They couldn't see anything when they looked up, except a peculiar black blot against the red skylane, rising rapidly, but agreed that the shout had seemed to come from this. The R.T.S. rallying cry was not to be ignored. They tumbled into the plane's cabin and took off.

It had been easy at first to keep the odd patch of blackness in sight while they wrangled about what it was and what they could do about the cry for help that had come from within it. When the thing started spiraling up in the forbidden areas under the lane-lights, however, a police plane had started for them and they were compelled to make for the white central zone where a plane is permitted to rise.

They came out at the top in time to see the strange black cloud blotched against the lighted gap in the Icarus's hull, and then the hatch closed on it. Still curious, they hovered about, uncertain whether to hail the stratoyacht or descend.

"All of a sudden," Jan continued, "from maybe fifty miles off, we saw that lifeplane bay start to open up again, but get stuck. Thinkin' maybe there was trouble aboard we sidled over to investigate, but before we were near enough to hail the Icarus a plane shot out and dropped away fast. About a mile down it started to circle, as if undecided on its course, so we sent it a call. What do we learn but that the pilot is R.T.S.'s most famous graduate, Rade Hallam, 'Eighty-three,' and that it was he who'd called the 'Yoh Kaydets.' He didn't explain, but asked us to slide upstairs and see what was what, so—"

"You spoke to Rade Hallam?" I broke in. "Where are—Where is he now?"

"Right out there, sir." Lovett pointed past me to the starboard colloid.

I turned eagerly, peered out, but Marney must have banked the poloplane just then, for all I saw was black ground, tipped up at a forty-five degree angle.

THE night-bound reaches were netted by the skylane's brilliant

lines of color, meeting, dispersing, meeting again. The Hudson

ran diagonally up across the black plane to where, at its top, it

vanished beneath the soaring towers and leaping arabesques of

Newyork. It slid away beneath and the amphibian I looked for slid

into the colloid's frame.

It winged smoothly on a parallel course to ours, not fifty yards off our starboard bow, and in its forward colloid I made out a small head canted in a familiar pert poise, a cloud of soft brown hair.

As though she heard my silent cry across the night, Mona turned.

"Would you care to speak to them, sir?" Lovett was holding a radio mike out to me. I grabbed it.

"Mona."

"Toom," came from the speaker disc over the pilot's head. "Toom, dear," and then a sob caught her throat.

"Steady, honey." My own throat was thick. "Steady. It's all over and done with. We're all safe away."

"Not yet, my boy." That was Rade Hallam. "Look to your port, up and astern."

I wheeled, stared. "I don't see anything, Rade."

"About thirty degrees west of north. In Leo."

"I—Yes, I see what you mean." It wasn't much, only a black blot flitting across the constellation of the Lion. "You think it's—"

"A plane from the Icarus, blacked out. Yes, Toom. Bardin's not done with us yet."

"Nice," I murmured. "Lovely. He can crash both our planes and no one will ever know why... Rade!" A new thought came. "The shock-gun. They don't have to crash us."

"No," Master Hallam agreed. "They don't have to crash us. They can paralyze us and take us back to the Icarus." His amphibian was lifting, was sliding off on its port wing. "Cadet Marney!" Abruptly there was crisp authority in the voice from the speaker-disc. "Hold your course and speed, regardless of me."

"Aye, sir," Marney snapped into the mike I'd handed to him. "I am holding course and speed." I no longer could see Rade's plane but I could hear the thunder of his propeller, right overhead, merging with our own.

Lovett was gaping at me, his mouth open to form a question.

"Cadet Marney—" Hallam's voice forestalled him—"at my word, 'now', off power and release your controls. Do you understand?"

"Aye, sir. At your word, 'now' I am to off power and release controls."

"Make it so. Now!"

There was no propeller thunder from either plane—and no light! Once more the utter blackness thumbed my eyes, and there was still terror in it—fear, the ancestral, abysmal fear of the dark that no centuries of civilization can quite expunge from Man's marrow, the crawling fear of things unseeable.

Somewhere in the voiceless black there was a whimper of fear in a youth's throat. Under my feet the deck slanted steeply forward.

"Hallam's blacked out our planes," I explained, "with a device on his own." The coils, of course, that crowded the cabin of the Icarus's amphibian. "He had grappled ours and is gliding both as a unit, down and away from where Bardin's men last glimpsed us." Groping for support, my hand brushed a naked arm and felt the cold sweat on it. "We could see them against the stars but we're below them and against the black ground. We're invisible."

"Smooth," Jan chuckled, but a quiver in his drawl gave away that chuckle as bravado. "A very smooth stunt, what I mean."

Marney was more practical, though his voice was thin with the horror of this sightlessness. "How can he keep us from crashing the skylanes, Mr. Gillis, when he can't see them?"

Rade saved me from having to confess I did not know the answer. "The forward colloid of this plane seems to be of some new material that makes visible the vibrations ordinarily incapable of affecting the human eye," he explained. "The infrared or ultra-violet—the violet it is. I can make out our antagonist's listener-rays, sweeping the sky, searching for us." The deck came level beneath me. "I can see the skylanes well enough to avoid being silhouetted against them and am winging silent on the helicopter vanes with which this plane is equipped, but those listener-rays are a danger we must avoid. There will be no more talk, please, till I give the word."

That was that. I sank to the deck, disposed myself to await what would come next in as much comfort as I could manage.

IT was not much. My shoulder was giving me hell, to say

nothing of the spark burns with which my skin was liberally

sprinkled. My bones ached with a fatigue they had not known since

I had fought the Aldebaran through a seven-hour meteor

swarm. And there was the weight of the blackness upon me, the

panic of claustrophobia shuddering in my veins.

I tried to forget all this by thinking about what had happened in the last couple of breathless hours. I tried to think. Exhaustion welled up into my skull and I slid away into a dream.

I was a bus-boy again in the Tavern of the Seven Pleiades, but crippled now and blind, and so nearly deaf that I could hear only dimly the stirring Song of the Spacemen....

Blast old Earth from under keel!

Set your course by the stars.

Spurn apace Sol's burning face,

Give....

"Mr. Gillis." Nick Raster had hold of my shoulder, one-armed, one-eyed, evil Nick Raster whom long ago I saw disintegrate into ashes on an island in the sky. "Mr. Gillis." His steel claws sank into my shoulder. "Wake up."

I was awake, but someone was still shaking me by the shoulder and I was still blind, still hearing dimly the chorus out of my dream....

Give Earth's greeting to Mars....

"Gemini!" Jan Lovett drawled. "I can't shake him awake."

"All right," I grunted, coming up to my feet. "I'm awake. What's up?"

"We're down, sir. Master Hallam has directed us to debark."

"Down! Where?"

"I'll be pithed if I know. This way, sir." The tiny poloplane had no hatch. You crawled out a colloid to debark from her, on to a wing. Still in utter darkness, I felt the coolness of the night wind on my face. The Song of the Spacemen had been no dream; the wind still brought it to me:

Say good-by to the Earthbound race

For back you may come nevermore...

I knew where I was—Newyork Spaceport, and by the direction from which that singing came, the Aldebaran's berth.

The Aldebaran is was. Coming off the wing, I felt underfoot the familiar planes of her capacious cargo-hold and then, abruptly, I stepped out of the black cloud that blanketed the hatch in her outer skin.

There in the hold, coldlight making an aureole of her hair, was Mona.

"Hello," she said, a little twisted grin on her face. "Hello, Toom." That was all, except for the way her hands took hold of mine and clung.

Still holding them, I turned to the youngsters. "These are the two heroes of this afternoon's game, honey. The big one's Jan Lovett; the little dark one, Nat Marney. My wife, boys."

I didn't mind the way they stared at her, open-eyed.

"It was a grand game," she told them, "and you both were marvelous."

A little to my surprise, the loquacious Lovett remained tongue-tied while Marney, who had been so taciturn in the plane, smiled and thanked her. "We played the best we knew how, ma'am, but we had to have the breaks to win. That Princeton team was good."

"But R.T.S. was—"

"Gangway." A green-skinned Martian lumbered in out of the black—it seemed to have a well-defined boundary. "Gangway, Bahss Toom." This was Atna, the Aldebaran's tubeman and her guardian when she was laid up in port and deserted by the rest of her crew. The black cloud was following him in!

We retreated before it, but it swallowed Atna. It stopped moving. Within it, the Aldebaran's hatch thudded shut.

The black cloud vanished.

Where it had been, the Icarus's lifeplane stood, wings folded. Rade Hallam climbed down out of it. His look found me. A smile flickered across his leathery countenance, like heat lightning, and then he turned to the cadets.

THEY had come to attention, heels together, backs ramrod

stiff, eyes wide with something very near adoration. Master

Rocketeer Hallam was a tradition, almost a legend of their

Craft.

"Your rescue of Controlman Gillis, gentlemen," he said, "was well done. My compliments."

Their faces shone, but his went bleak. "Your strict attention, Cadets," he rapped out. "I can arrange that you return to Training School, without untoward consequences from what you have done thus far tonight." Hoi Tarsash, I supposed, would take care of that. "I am, however, about to request you to do something important whose consequences I cannot foresee. I can give you only the assurance that to do as I ask would most likely result in your being barred from the spaceways for life, and not improbably, a terrible death."

His thin nostrils pinched, flared again. "The Aldebaran has no clearance from I.B.C and so may not leave this berth without rendering her officers and crew liable to Earthbinding. She is fully fueled, but only a quarter provisioned. She has not been inspected since her last flight and may very possibly develop a fatal flaw. Her crew-complement is twenty-one trained spacemen. To attempt to astrogate her with five, two of them novices to actual space, would be suicidal.

"I intend, gentlemen, to blast off for interspace within ten minutes, if you make that possible by volunteering to blast off with me."

He paused. It was very still in the vast, bare cargo-hold as his eyes studied the cadets' faces. Some flicker of expression, not quite a smile, told me he was satisfied with what he saw, and then there was once more the even, unemotional flow of his voice.

"This morning, I gave my pledge to a great and very wise man to speak of what passed between us to no one on Earth. I cannot, however, ask you to risk your careers, your lives, without explanation. Perhaps—" now he smiled, but the faint smile that touched his thin lips held bitterness—"it is quibbling to say that when the hatch of this spaceship closed on us, it somehow divorced us from Earth, yet that is the feeling of all spacemen. I feel justified, therefore, in making that quibble. That hatch may open again, however, at your word, to return you to Earth. I rest it on your honor as space cadets that if it should, what I say to you now will remain within the hull of the Aldebaran. I know that I can fully trust that it will."

The skin over my cheekbones was tight. Mona's lips were half parted and her breath seemed to hang upon them. Was it the coldlight that made Rade Hallam seem so haggard?

"As you all know," he began again, "for a hundred and forty years, since the War of the Three Worlds ended in the organization of the Triplanetary Federal Union, all humankind has lived under a government of, by and for the people. Venusians, Martians, Terrestrians alike, within the limits only of our obligation to interfere as little as possible with the happiness of others, we are free to pursue happiness, each in our own way.

"It must seem incredible to you, as it did to me until this morning, that any man should wish to change this. Yet there is such a man—"

"Gurd Bardin!" I could not help exclaiming. "That's what—" and then Rade's look silenced me.

"Yes, the man is Gurd Bardin. Ambition, lust for power, some biological urge, perhaps impels him to add his name to the long list—Yo Husoshima, Hitler, Napoleon, Genghis Khan and many more on our planet alone, to say nothing of the others—who have attempted to make themselves masters of their worlds, its people their slaves.

"This, by a lucky accident, Hoi Tarsash discovered. Bardin's conspiracy is only in its formative stage as yet; his adherents, though completely under his domination, still few. The whole thing could easily be crushed by decisive action, but when Tarsash took what he had learned to his colleagues on the Tri-Planet Council, he was met only with unbelief and derision.

"'Proof,' they demand of him. 'Bring us proof that this is true, and, if true, anything more than a madman's dream.' They say, as democratic parliaments have always said to those who warned them against a threat to democracy, 'In these civilized times, no man can make himself so strong that we need fear him.' And they will wait, as parliaments have always waited, until the man has made himself so strong that he cannot be stopped without widespread destruction, desolation, disaster."

Rade Hallam pulled in breath, let it seep slowly out between his thin, colorless lips. "They would wait, in the age-old pattern, till it is almost too late to stop Bardin, and there would be no hope of moving them before that, except for one thing.

"Like Napoleon's artillery, Hitler's planes and tanks, Husoshima's Flaming Death, scientific development has perfected for Bardin a weapon so terrible, so resistless, that if his possession of it can be proved to the Council they might be shocked into moving against him before he is ready to use it. We have no information as to what this weapon is, and only a vague idea where he is building it.

"This, gentlemen, is the mission with which Hoi Tarsash entrusted me this morning—to find that weapon and bring back to him incontrovertible proof of its existence.

"This is the mission, gentlemen, in which I ask you to join me. As soon as Gurd Bardin learns we are aboard the Aldebaran, he will mobilize the forces of the I.B.C to prevent our blasting off. We must leave at once, or not at all, and so I can give you only ten seconds to make your decision."

Jan Lovett started to speak.

"Wait!" Hallam snapped. "I insist that you take the full ten seconds before you reply."

Ten seconds to decide whether to gamble their careers and their lives against a man's word that the gamble was worth it. Ten short seconds—nine now by the sweeping hand of the clock on the cargo-hold wall.

Mona's hand, clasping mine, trembled a little... Eight seconds... Rade Hallam was a slender, expressionless figure, his gaunt countenance a mask, his brooding eyes on that inexorable second hand... Six seconds... Atna, a stoop-shouldered, ungainly hulk in the metal-fibred suit the workers from the red planet affect, watched Hallam out of lidless eyes that mirrored a doglike devotion... Three seconds... The coldlight twinkled on the satin-smooth, bronzed arms of the two cadets and that was the only movement in the great, empty cargo-hold.

But it seemed to me that something stirred here, inconceivably vast in numbers, in extent of space and time, waiting for what would be said here as the infinitely long ten seconds ended.

"Well, gentlemen," Master Rocketeer Hallam asked, "what is your decision?"

Nat Marney had not consulted Jan Lovett by so much as a glance, but we knew he spoke for both. "We are with you, sir. What are our orders?"

The corners of Rade's stern mouth twitched. "You will take your orders from Tubeman Atna for the present." Only his eyes gave them accolade. "Atna!" He turned to the Martian. "Take them to the fuel-hole and prepare to blast off in five minutes.—Controlman Gillis!"

"On deck."

"Ready ship for space, then report to me in the control cabin."

As I followed Atna and the two youngsters out of the hold, I heard Rade, his voice no longer the clipped, impersonal one of the master rocketeer but warm and affectionate—and regretful.

"Mona, dear, I should have liked to set you ashore, but I can afford neither the time nor the risk that Bardin might snatch you again."

"Set me ashore!" Her laugh was silvery, tinkling. "Leave me behind! Why, uncle, you should no more have thought of that than you did of asking Toom whether he wanted to go along."

"Toom—By Scorpio! It never occurred to me to put the choice to him."

"He would never have forgiven you if you had."

She knew me almost better than I knew myself, that gray-eyed wife of mine.

I WAS strapped into the controlman's chair, Master Rade Hallam clamped into the hammock spring-hung from the ceil of the Aldebaran's control cabin. His stratagem in concealing our arrival and entrance into the spaceship by use of the black cloud from Bardin's lifeplane had been completely successful. No light had shown out across the spaceport's tarmac. No one could know there was anyone beside Atna aboard.

They would know in an instant. "All set for blast-off," I reported. "Make it so, mister." Rade acknowledged. My hand closed on the handle of the switchbar before me. "Blast off!"

I shoved over the switchbar.

A gigantic, invisible weight forced me down on the chair's heavy springs. There was no breathing, no sight, no thought but that I must not let go the handle in my grip. Blood swelled my fingers, my body, as an acceleration of ten times gravity pressed consciousness from my darkening brain. Somewhere a bell rang, signal that we had attained the seven miles per second speed that would free us from Earth's pull to her center of mass. I held the switchbar an instant longer, released it.

The weight was gone. My head cleared and sight returned. In the central pentagon of the great six-fold viewscreen that filled the wall in front of me, I saw only the starry blackness of space to which the Aldebaran's nose was pointed. In four of the squares leafing out from that pentagon were only the stars; port, starboard, keel-ward and above—above with respect to the ship's own decks. In the lower, the sternward square, however, was a vast, concave bowl, night-filled except along one arc of its rim where the flaming colors of the sunrise were painted.

That bowl was the Earth from which we rushed; our only link to it as it rounded out to a hemisphere was a violet, diaphanous streamer, the glowing gases from the rocket tubes that sped us into the void.

The glowing steam, rather, heated to incandescence. Our fuel was hydrogen and oxygen, mixed one to two at the tube nozzles and ignited. Ignited and exploded, their product was water.

"Power off!" I heard Master Hallam's order.

"Power off," I signaled Atna in the fuel-hole.

The Aldebaran was in free fall.

Between us and our lavender wake, a black gap grew swiftly. We were leaving no trail by which our course might be traced.

"Well—" I grinned feebly, turning to Rade—"we're in for it."

"Yes, Toom, we're in for it. Gurd Bardin needs trump up no excuse now to set the Patrol on our tail."

IT WASN'T long before we knew Bardin had done just that. The

message came, a sputter of dots and dashes, from space-radio

speaker, the order to the I.B.C's far-flung watchdogs of the

spaceways.

T.S.S. ALDEBARAN IN UNAUTHORIZED FLIGHT. ARREST. PITH IF RESISTED.

But we were off the Venus and Mars routes by that time, where the Patrol keeps its eternal vigil against the pirates who nest in the Asteroid Belt. Even though our tubes were on again, building our speed up to an even twenty mile-second pace, it was a million-to-one chance we should be sighted.

The Aldebaran, half-a-million tons of durasteel, was an infinitesimal mite in the immensity of space.

The first Earthday out Hallam devoted to settling our routine. He put Mona in charge of the galley. Atna's division was, of course, the fuel-hole. Astrogation and all the other innumerable tasks about ship were to be shared between himself and me.

A single tubeman could not manipulate all the Aldebaran's innumerable valves and so the cadets were to alternate in aiding the Martian, the youngster free of that duty to help me or Rade, whichever needed help most.

"We'll have to make that do, Toom." He smiled wanly when the others had dispersed to their stations. "But it's going to be tough."

Tough was right. With a full crew there would be, aside from the galley-complement, three at the tubes, two in the control cabin and two on general duty for each watch, and there would be three watches. We had only five to do the work of twenty-one.

Sleep? We snatched twenty winks when we could; there was never time for forty. Eat? Mona tailed us about the decks practically forking food into our mouths. Rest? We forgot even the meaning of the word.

On the sixth day—I think it was the sixth; the Sun in space makes no neat black and white parcels of day and night and I'd lost all sense of time—Nat Marney was helping me check position.

"Alpha twenty-four point six." He repeated the readings I called from the starscope. "Beta eighty-nine point seventy-three. Gamma three point-forty-six." He looked up from the chart. "Right, sir."

"Make it so," I told him and then something in his dark face made me ask, "What's the matter? Aren't you really sure it clicks?"

"No, sir. I mean yes, sir. It clicks, all right, but—" He checked, turned away from me to stow the Mulvihall's Tables.

"But what?" I rasped. "What's eating you?"

"Well." He looked for all the world like a troubled twelve-year old caught in some dereliction. "It's our course, Mr. Gillis. Unless my reckoning is all wrong, the only planet in this quarter of space is Mercury."

Knotting small muscles ridged my jaw. "Your reckoning is correct. What of it?"

"Master Hallam can't be planning to land us on Mercury. We'd be crisped."

"Cadet Marney!" I had been thinking along the same lines, my uneasiness growing. Perhaps that was why my voice was thick, growling, as I demanded, "Do they teach you at R.T.S. it is part of a midshipman's duty to question his master's judgment?"

"No, sir, but you asked—"

"Marney!" I broke in. "You are insubordinate." My shoulders hunched forward and I glared at him narrow-lidded. "If we were not short-handed, I should brig you."

He paled a little, drew himself rigidly erect. "I am sorry, sir, if I appear to be, but may I suggest that you are unjust?"

"Unjust, am I?" I was moving toward him, stiff-kneed. "Why, you blasted whippersnapper." My fist rose. "I'll—"

"Mr. Gillis," Hallam's quiet voice said behind me, "if you can spare Marney for ten minutes, I should like him to go below and check the gravity grids."

"I can spare him," I growled, "plenty more than ten minutes... You heard, Marney. What are you waiting for?"

The cadet saluted smartly and exited.

I twisted to Rade. "You were right, down there on Placid. He's a hero in front of a crowd, but when the going really gets rough, he can't take it."

The master looked at me, a half-smile on his tired visage. He was more gaunt than ever, his eyes red-rimmed, and at the center of his brow were two deep, vertical lines of pain. "He is young, Toom, and for a lad's first trip into space, this is—" His bony hand made a small, eloquent gesture. "All our nerves are scraped raw. Look here. Why don't you take fifteen minutes or so and visit with Mona in the galley? She must be wondering by this time if she really has a husband aboard."

It wasn't till afterwards that I realized I had heard the cabin hatch open, behind me, when Marney first mentioned Mercury.

THAT blessed quarter-hour with Mona was the last I had for a

long time. The hours blurred and the days blurred to a

featureless grayness, and still our wake of glowing gases trailed

behind us across the black waste. Two million miles in each of

her days we laid Earth behind us and in the stern view-screen she

dwindled to a tiny ball in the heavens, to a star lost among the

myriads crowding the void.

I waited with mounting apprehension for the order to change course, but it did not come.

Twenty million miles out, the orb of Mercury was black against the blaze of the sun... Thirty million miles... The Aldebaran was triple-skinned against the absolute zero of interspace, but her hull was pierced by cargo-hold hatch and airlocks. Insulated though these were, they brought in to us the torrid heat that beat upon them. The ship became an oven, a breathless kiln.

Thirty-five million miles.

Surely by now we were safe to make for our real objective. Surely by now the I.B.C must have given up the hunt for us—A sputter from the space-radio broke in on my thoughts, giving the designation of a Patrol spaceship, its location ninety-five degrees of arc from us. Then:

NO TRACE OF T.S.S. ALDEBARAN. MAY WE RETURN TO STATION?

Faintly the answer came, very faintly:

KEEP SEARCHING... BARDIN, I.B.C

"They will never find us," I croaked. "Who would think us insane enough to drive so near the Sun?"

The eyes Rade turned to me were deep sunken in bluish hollows. "One man knows now where we must be, since the Patrol has not found us, but he dares not send them to search for us in this quadrant of space. They might find something he dares not let them see... Keep her as she is," he ended, relinquishing the chair to me.

Keep her as she was! Into the blaze of the Sun, into heat no human could long endure quiescent, let alone labor at building a weapon. The speculation against which for some time I had barred my mind entered it now.

Conning space as a master rocketeer saps not so much the body as the brain of a man. Rade Hallam's Silver Sunburst was ringed by thirteen stars, and before that he had served ten years as controlman. No spaceman in all the fleet has ever come within four years of matching that length of service, yet more than one rocketeer has been known to crack up, mentally, on the spaceways. The grueling flights through blackness are murderous. Not Rade, not Rade Hallam. Once more I closed my mind against the thought.

Forty million miles.

I HAD been inspecting the tiers of chemical trays that

cleansed our breathed air of carbon dioxide, restore life-giving

oxygen. Forcing reluctant legs to carry me down the companionway

toward the fuel-hole, I heard a fatigue-blurred but infinitely

sweet voice singing:

Behind the Moon, a million miles,

Lovely lady, I dream of thee....

I stopped short, the ache of weariness in my bones easing. Mona was singing our song, the song that I had heard her sing even before I first saw her, the song that was the refrain of our love. The mists cleared from my vision and I made out the rectangle of the galley hatch breaking the rivet-studded companionway bulkhead, here beside me.

...Black space is bridged by your mem'ried smiles,

And the stars bring your kisses to me....

Looking through the hatch, the heart drained out of me. Mona was not thinking of me as she sang that song. Jan Lovett was in there, slumped in a chair and she stroked his hair, standing over him and singing.

"Mr. Gillis!" There was urgency in the shout that pulled me around to the fuel-hole. "Mr. Gillis!" It was Marney, calling me from that hatch. By the sound of his voice there was trouble.

He ducked back in as I started on a stumbling run for him; he was bending over a greenish bulk sprawled on the deck plates as I entered.

"Atna has keeled over," he grunted. "And I can't find his pulse."

"Even a Newyork summer half kills him," I rumbled, staring down at the scarcely breathing Martian, "and this is a cavern in Hell. Fifty above is hot on Mars—Well, get him to the sick bay. Mona will bring him around."

As Nat carried him out, I pressed the heels of my hands against my throbbing temples. Mona... Lovett—That must wait. Atna has collapsed. I shall have to take over as tubeman.

How was Rade going to manage? Neither cadet was ripe for a trick at the switchbars, but Hallam could not con the ship without sleep.

A second's drowse, a meteor not glimpsed in time, and the Aldebaran would be pithed.

"Controlman Gillis," a metallic voice droned my name. "Gillis." It was the intra-ship communicator. As I got to the mike I was vaguely aware that Marney had returned, Lovett with him.

"Controlman Gillis on deck," I reported. "In the fuel-hole."

"I want you up here, Toom."

"Sorry, Rade. The heat's got Atna; I have to take over his division."

"Atna!" Hallam's ingress of breath was plainly audible. "But—"

"We can manage, sir." Lovett's eager voice was loud in my ear. "Nat and I know this hole by now; we can handle it."

"You can handle—" I checked as Rade's, "Controlman Gillis!" cut across my exclamation. "Turn the tubes over to Cadets Lovett and Marney, Gillis, and report to me at once."

"Very well, sir." I had no option except to yield, but, as I pounded into the control cabin, I protested, "Those cubs will wreck us, Rade. You can't do it."

"What do you make of this, Toom?" He seemed not to have heard me, so absorbed he was in the sternward view-screen. I reached him. "Five degrees gamma of Terra." He told me where to look.

A star was missing, out of Draco.

"I see. Thuban's blotted out."

"Has been for the last five minutes."

"So there's a meteor moving along the straight line between us, either away from, or following us."

"Following us." Rade's voice was so tense it thrummed. "And not a meteor. Take a look through the electelscope."

Karsdale's remarkable application of electronics to optics that in the space of a tube no larger than a man's arm reduces the apparent distance of an object to one-tenth the actual, was already switched in, but the thing that obscured Thuban must have moved since Rade focused it. I twirled thumbscrews until I got it clear again.

No, it was not a meteor. Silhouetted against it was a spaceship, slimmer than any craft I had ever seen. Wasplike, she seemed, and, like us, she was in a quadrant of space where no craft ought to be.

Doped with the poisons of fatigue, still shaken by what I had glimpsed in the galley, I forgot I was not on watch. I grabbed the mike, hailed the stranger. "Ship ahoy! What ship is that?"

Her reply was a bolt that lightninged, blue and vicious, across the void to pith the Aldebaran!

THE Sun, that so nearly had sapped the life from us, now saved

our lives. It dazzled the wasp ship's gunner and, though his shot

whizzed by too close for comfort, it missed.

Violet dust against black velvet, the stranger's rocket-flare spewed from her tubes now, to make a wake matching our own. She had been sneaking up on us, hopeful to take us unaware. Well, she had almost succeeded. By the 'scope's range-finder, she was within a hundred thousand miles of us, which in the scale of space is a small distance indeed—especially when one is stalked by death.

She spat another bolt at us, better aimed, but, watching for the flash, Hallam flung the Aldebaran portwise and slipped it. Those high-potential charges travel only half as fast as light, and so he'd had a full second to estimate its trajectory and avoid it. He would not have as long for the next; the attacker was closing in fast.

Rade shunted in all our stern tubes, dodged the third bolt. Our relative-speed indicator, set on Polaris, showed that we'd leaped to forty miles a second, the Aldebaran's limit.

It was not enough. The killer craft was pulling up on us fast. Her master, however, seemed to have made up his mind to expend no more bolts till he was near enough to be sure of a hit. Every one of those whirling bits of ionic disruption drained five hundred thousand kilofarads from his condensers and, huge though they might be, they were not inexhaustible.

"She's doing forty-five mile-seconds, Rade," I reported from the relative-speed indicator that I had set to our pursuer. "I didn't know there was a ship ever built could accelerate to that and maintain it."

"There was one." I realized with a sort of shock it was the first time he had spoken. "You are looking at the Wanderer."

"The Wanderer," I echoed the word, not the calm matter-of-factness of his tone. "I don't recall—"

"Bardin's one great philanthropy, supposedly." Rade chuckled. "Strap me in, please."

I passed the blast-off straps around his chest and thighs as he went on. "He had her built, at staggering expense, as a floating laboratory, to study the cause and course of ether swirls. She blasted off for her trial flight three years ago, and never has been reported since."

"Her loss was faked." His meaning dawned on me. "Bardin has been using her as his contact with wherever in space he is building those mysterious weapons of his."

"Obviously. She probably makes Earth-port in one of the great deserts, is loaded there from his big airfreighter tramps. Look you. She was probably a day or two out on her Earthward journey when we blasted off. Bardin would be overheard radioing her to turn and chase us, and had to wait till she made her grounding."

"All of which," I observed, "is very interesting, but it doesn't alter the fact that her speed beats our best by at least five mile-seconds and that she is using it to overtake us and pith us."

"Perhaps," Rade Hallam said softly, "we can do something about that." I had the impression that he had come to some decision. "Pass the order to Mona to strap Atna in his bunk, and herself in a blast-off hammock."

I complied. Mona acknowledged, started to ask a question.

I cut her off, turned back to Hallam with blood pounding in my temples. "Look, Rade. I don't know what you are up to, but I'd better get down to the fuel-hole and take over."

"What for?" he wanted to know. "The youngsters have done all right so far, haven't they?"

"Aye," I admitted, grudgingly. "I guess they have." I had to; not even Atna could have responded to Rade's signals more instantly. "But—"

"I am satisfied with their performance," he broke in coldly, "and I may need you here. Get into your own hammock, Mr. Gillis. At once."

I should have been content, I suppose, as I complied. These preparations indicated Hallam expected the Aldebaran to be tossed around. Anyone in the fuel-hole would take a licking, since tubemen must be free to move around. I should have been content, but I was not.

Whether I was or not would make little difference when the Wanderer had closed to a distance at which we'd have no time to dodge the bolt that would rip the Aldebaran stem to stern, gut her of air and leave her a durasteel coffin to drift eternally in space. Clamped in the hammock, I looked at the viewscreen to see how much she had gained.

"Cygnus!" I gasped. "Where's the Wanderer gone to?" Only whirling stars showed in the astern leaf. "She—" The Sun sliced down into it, blazing.

The Sun was behind us! It couldn't be—but there it was, and there was the Wanderer in the central pentagon. The Sun was behind us and the Wanderer was ahead, visibly swelling in size, fairly leaping at us!

That meant—leaping Leonids! It meant that Rade had put the Aldebaran clear about, that he was hurling her, forty miles a second, at the wasp ship, herself rushing toward us at forty-five. Deliberately, he was closing the gap between us and our enemy by five thousand miles a minute.

It was sheer madness. Unless—

"Bardin's aboard her," I voiced my sudden inspiration. "You're going to ram her and take him to Sheol with us. Well, that's one way of making sure he'll never be tyrant of the Three Worlds."

"It would be," Rade agreed, "but—"

I hit the ceil as the Aldebaran crash-dove to avoid the bolt a startled gunner had flung at us. Hallam brought her to even keel again, was once more catapulting her at the destroyer. "But," he continued, unperturbed, "I should be very much surprised if he has risked his precious neck aboard her."

I gave up trying to think what he was about. A stern chase is proverbially a long chase, and in a long chase some miracle might have happened to save us. He was throwing away the chance of that miracle to make a magnificent but futile gesture.

Magnificent it was. Never in all the long history of space-flight has a craft been handled as Rade Hallam handled the Aldebaran.

He danced that half-million tons of durasteel like a flitter-moth, there in the void. He flung her at the wasp ship, dodged a bolt, streaked for the Wanderer again. He played the switchbars as though they were the keys of a piano. He ducked and leaped and wove, and every chance he got hurtled, like a bat out of hell, for the killer-craft Gurd Bardin had dispatched to murder us.

Mad it might be, but it was splendid.

INEXORABLY the distance separating us shortened... Fifty

thousand miles... Forty... Ten thousand—Abruptly I realized

that for a long minute no bolts had spat at us from the slim wasp

ship.

"He's used up his condenser charge," Rade grunted, and slung the Aldebaran at the Wanderer, head on across the void.

I ought to be scared, I told myself. I ought to be numb with fright. That is death ahead, waiting for us.

Not waiting, leaping to embrace us. Bardin's killers matched daring with Rade Hallam's daring, courage with his courage—madness with his madness. They streaked head on to meet us, to crash us, there, forty million miles from the planet that had given us birth. They could have turned, easily could have fled us, but they leaped to meet us.

Across my mind there trailed the thought of Mona, brown-haired, gray-eyed, nose pert-tipped and mouth red and sweet. In minutes, Mona would die too. An hour ago it would not have been so dreadful to die, knowing that in death we still would not be parted, but I had heard her sing, in this past hour, had seen her, through a galley hatch....

The bitterness in my breast was not because I was to die so soon.

A hundred miles only separated us from the Wanderer... fifty... She filled the central viewscreen—shot down out of it!

We had leaped up over the catapulting wasp ship. It was Rade Hallam who in the ultimate instant had lost nerve!

Sun-glare blazed out of the middle pentagon. The middle! Rade had back-looped the Aldebaran, was hurling her back toward the Sun. Antares! The Wanderer was in our keel screen! Rade was holding the Aldebaran over her, right over her. He was holding the Wanderer in the fierce down-blast of our under-keel rocket tubes, oxygen and hydrogen mixed one to one and ignited. He'd made a gigantic blow torch of our keel tubes, just such a torch as had sliced the Icarus's durasteel wall, and in that awful blast he held the ship Gurd Bardin had dispatched to murder us.

I saw the Wanderer flare to a red horror. I saw her blaze white as the blaze of the Sun. I saw her slim, graceful shape blur and melt in upon itself. In the Aldebaran's keel-screen I saw a glowing cinder, a bit of slag without shape or form or life.

Only one craft died there in space, forty-two million miles from Earth.

I ROLLED out of the hammock, clutched at the back of the

controlman's chair. "By Saturn, Rade," I gasped. "If I hadn't

seen you do it, I would not have believed it could be done."

He turned to stare at me, gray-lipped, nerves twitching under his gray skin. "It wasn't easy. Toom. It wasn't easy at all. But it would not have been possible if it had not been for those youngsters in the fuel-hole."