RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

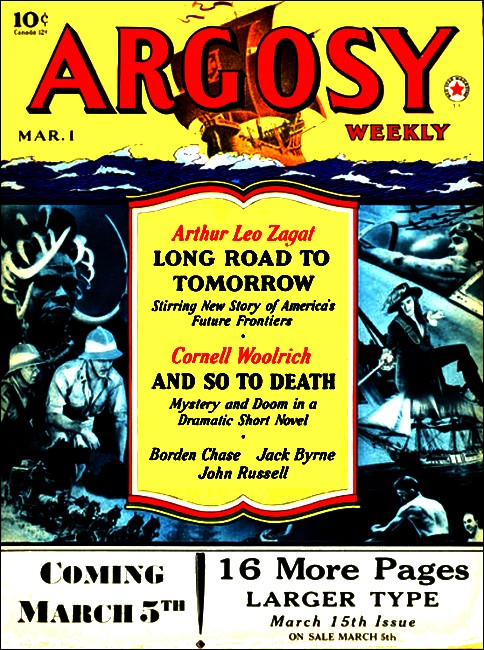

Argosy, Mar 1, 1941, with first part of "Long Road to Tomorrow"

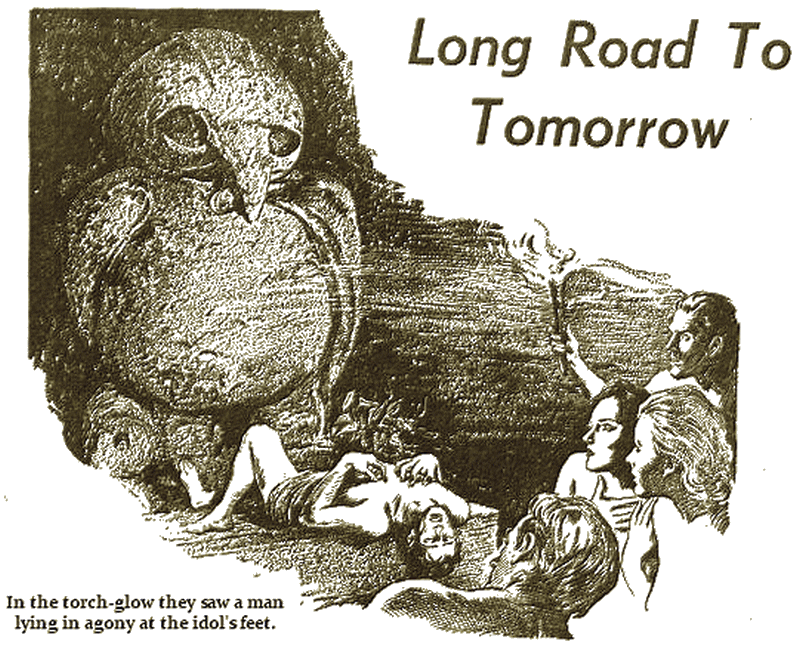

Headpiece from "Argosy," 1 March 1941

From:

A History of the Asiatic-African World

Hegemony,

Zafir Uscudan, Ph.D. (Bombay), LL.D. (Singapore) F.I.H.S., etc.

Third Edition, vol. 3, Chap. XXVII, pp 983 ff.

THE night before the Asafrics captured New York, completing their conquest of the Western Hemisphere and thus of the entire Occidental World, an attempt was made to evacuate several thousand children from the doomed city.

The motorcade was discovered by a Yellow airman who, in the report discovered by the writer among the charred archives unearthed beneath the ruins of the Empire State Building, claimed to have entirely destroyed it by machine-gun fire and a few judicious bombs.

He was mistaken, however, in that one truck of the hundreds escaped. Among its load of children between the ages of four and eight was a youngster then known as Richard (or Dick) Carr, the very individual celebrated in legend as Dikar.

The aged couple who were the only adults with the group contrived somehow to bring the children unobserved to an uninhabited mountain deep within the forested recreation area that at the time stretched for some miles along the west bank of the Hudson. No more ideal sanctuary than this height could have been found.

Not only did thick woods screen its surface from aerial reconnaissance, but quarrying operations had ringed its base with a precipitous cliff so that the only practicable approach was by a narrow viaduct of rock that the stoneworkers had left for their trucks.

Barely, however, had the party begun to orient itself when an Asafric platoon appeared on the plain below, with the evident intention of scouting the mountain. In this desperate emergency the two old people blew up the narrow ramp heretofore mentioned, burying under tons of riven boulders the green-uniformed soldiers—and themselves.

The children, afterward to be known as The Bunch, were now completely isolated from an inimical world. As to how they survived the primitive environment in which they found themselves we can only guess. Survive they did, for a dozen years later we find a band of youths bronzed, half-naked, and armed with only bows and arrows, descending on an Asafric motorized column to snatch from his chains the man called Norman Fenton.

THIS amazing foray is conceded to have been the first skirmish of the Great Uprising, but it was the capture of the Asafric stronghold at West Point, for which General Fenton's memoirs give full credit to Dikar and his Bunch, that set ablaze the fires of rebellion throughout a heretofore cowed American nation.

In preceding chapters we have seen how a ragtag and bobtail mob rallied around Norman Fenton at West Point, how the Second Continental Congress came into being here and elected Fenton President and Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of Liberation, how here was evolved the brilliant strategy with which Viceroy Yee Hashamoto found it so difficult to cope.

The reader doubtlessly recalls the essential elements of these tactics; the feinted raid on some sparsely garrisoned outpost, the real assault on the stronghold weakened by the dispatch of reinforcements to the point first threatened, the looting of the fortress of its guns, ammunition, all its portable munitions, the Americans' swift dispersal before the Asafric planes and tanks could return to annihilate them.

They split up into roving groups, well armed now and ferocious as only men can be who bear on their backs the scars of cruel whips, in their hearts the memory of homes in flames.

All across the continent these guerilla bands harassed Hashamoto's far-flung, thin lines. They ambushed and slew the small detachments through which he had maintained his subjection of his white slaves.

It is apparent how well Dikar and his brothers were fitted for such a campaign. Silent brown shadows never more than half-seen, they stalked men now instead of deer, and all the woodcraft they had learned on their Mountain, their tireless endurance, even their naive ignorance of fear, came to their aid in their new pursuit.

Is it any wonder that about the hidden campfires the tales of their prowess should grow to sagas of supernatural feats? Is it remarkable that it should be whispered that they were not flesh and blood at all but, risen out of long-forgotten graves, the same lean-flanked forest rangers who once seized Ticonderoga from the scarlet-garbed mercenaries of an earlier oppressor?

FROM the writings of Walt Bennet, Fenton's devoted aide,

we learn how tremendously the growing myth bolstered the

patriots' morale, but it does not appear that during that first

memorable winter the Bunch otherwise greatly influenced the

course of the Uprising to which they had given its great

Leader.

By the beginning of spring, the Asafrics, while still nominally in command of the entire country, had for all practical purposes been compelled to relinquish their hold on vast stretches of territory.

Save for the fortified strongholds to which they had retreated, they had virtually abandoned the great central plain north of the Panhandle of Texas, from the Rockies to the Missouri-Iowa-Minnesota border. East of the Mississippi they had fared somewhat better, but a map colored black where Hashamoto was still in full control would have shown two enormous patches of lighter hue.

The larger of these had spread northward from the Americans' first foothold at West Point to include virtually all New England, south to Georgia. New York City itself remained the Asafric Headquarters and a hundred-mile wide strip all along the seacoast lay under the shadow of their fleet's big guns. But the Americans commanded the central half of Pennsylvania, and Piedmont Virginia and the Carolinas to the western slope of the Blue Ridge Range.

On the other side of the Appalachians, Fenton's forces had retrieved the southern three-quarters of Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee as far east as the Cumberland River.

These latter two liberated regions approached each other most nearly in the neighborhood of the Great Smokies, and the strip separating them contained Norris Dam and other works at the head of the Tennessee Valley development.

If General Fenton could close this gap, not only would he cut in half the Asafric Army of the East, but he would be enabled to shut off the supply of electric energy to the industries of the deep South. This, in the last week of April, he moved to attempt.

But Viceroy Yee Hashamoto was fully aware of the strategic importance of this region, and he held the mile-high Smokies in force....

SINCE the day when the Asafric Planes first came into the sky over Wespoint, Dikar had heard their thunder many times. Many times he had heard the black eggs scream earthward out of the planes' opening bellies, heard the eggs burst in terrible sound.

But this was something even more terrible—a noise too great to hear. Dikar felt it rather, like an enormous hammer that never lifted but only got heavier and lighter and heavier again as it pounded him into the ground on which he lay face down.

The thunder was a hammer pounding him and a hammer somehow inside of him, pounding outward against the walls of his body till it seemed his body must burst like a bomb.

Outside him and inside him was the thunder and Dikar was a part of the thunder, the thunder a part of Dikar. Dikar was one with the thunder, one with its terror.

Yet one thought remained with him, in spite of the hammers beating his body and his brain—the thought that somewhere near him lay Marilee.

He had caught her up in his arms when the sky suddenly darkened with the black planes and he'd half-jumped, half-fallen into this gully. She had pulled from his arms to lie beside him as the thunder of the Asafric guns pounded down on them from the smoking tops of the mountains.

Was Marilee still here beside him? Or had some bit of flying iron, some sharp arrow of splintered wood, taken her from him forever?

Dikar got hands under his great chest. The muscles of his broad shoulders tightened. The muscles in his arms bulged. His arms quivered, straightened, lifted the weight on his shoulders. He raised his face from the red earth, and he looked to where Marilee should be.

Dikar saw nothing but green brush, green leaves, beaten down as no storm had ever beat down the brush on the Mountain. He stared, a huge fear rising in him; and then he gave a choked cry. For now he saw a white sarong that clung to the graceful young body of a Girl. He saw an arm, a shoulder, rounded, silken- skinned. In the hollow of a beloved throat he saw a pulse fluttering.

Some gust of sound brushed aside a spray of quivering leaves and Dikar saw the firm little chin, the delicate oval of Marilee's face.

WITHIN the shadow of their long lashes, Marilee's gray

eyes were big with terror. They saw Dikar and into them came a

sudden smile.

A beam of sun was somehow in the thunder-shaking gully. It made little glints of red in the rippling cascade of brown and shining hair on which Marilee lay as on a bed. It made a shining in Dikar's blue eyes; and now the thunder that beat at Dikar was noise only, no longer terror.

Dikar smiled at Marilee, and he came up on his knees and looked over and past Marilee for the Boys and the Girls he had led so far from their Mountain.

The gully was narrow and its side steep, and it was filled by a tangle of bushes with long, thick leaves and great purple and white flowers like none Dikar had ever seen before. Peering into that thunder-tossed tangle, Dikar saw a little white bundle of fur, a long-eared rabbit crouched flat to the ground, its eyes glazed with terror. It crouched there right next to Franksmith, and did not fear him.

Franksmith's arm was flung out to one side and his hand clasped tight the hand of a black-haired Girl, Bessalton, Boss of the Girls. The sight of that brought a sudden warmth to Dikar's heart. Although most of the older Girls of the Bunch had found themselves mates, Bessalton had walked alone, since Tomball had died, and it was good that she would be alone no longer.

Past those two were more of the Bunch, flat to the ground, but even Dikar's sharp eyes could hardly make them out.

The Girls of the Bunch in their white sarongs were a little easier to see than the Boys who wore dappled fawn-skins that melted them into the shadows. All of them lay very still the way they'd fallen when they jumped into the gully, as still as the rabbit there by Franksmith.

The creatures of the woods lie very still when there is a danger too strong for them to fight and too swift for them to run from. This was a thing the Boys and the Girls had learned from the animals and the birds.

The gully was narrow and deep, and just as the leaf-roof of the Mountain's woods had hidden the Bunch from the Asafric planes, its thick brush tangle might hide them here. Dikar looked up to make sure that the green tangle was thick enough overhead—and his breath caught in his throat.

There was no hiding roof over him. The wind of the thunder had stripped the leaves and the great purple flowers from the branches of the brush and was stripping the very bark from the branches. Dikar could look right through what had been a safe covert. He could see clods of earth flying over the gully on the breast of the thunder-wind, and bits of wood that had been trees. And there were flying red fragments that could be human flesh.

NOT only the Bunch had been caught here when the black

planes came into the sky and the guns started to thunder from the

mountain-tops. Hundreds of other Americans had moved down into

this valley. From far away they had marched by night, slept by

day, to gather here in answer to the orders General Normanfenton

had sent out over the Secret Net.

Never before had so many Americans marched together. An Army, Dikar's friend Walt had called them. Never before had an army of Americans moved so far, so slowly, and this had worried Dikar, worried him all the more because till today the Asafrics had made not the least try to stop them.

Yesterday Walt had laughed when Dikar told him about his worry and begged him to tell Normanfenton to be careful.

"Hashamoto has no idea of what we're up to," Walt had said. "All the Shenandoah Valley down which we have come, and this northwest corner of North Carolina, was swept clear of his Blacks a month ago, and no white man or woman would betray us.

"We have one more night to march, my boy, and one more day to sleep. Tomorrow night, we'll surprise the Asafrics in their mountain stronghold while our friends in Tennessee storm the Cumberland Gap from the other. By sunrise, two days from now, the Smokies will be ours."

"The Smokies?" Dikar had repeated.

"Look." Walt had pointed, and Dikar had seen that what he'd thought a blue cloud low in the sky was really an up-tossing of the earth such as he'd never seen before. "Mountains," Walt had answered the question in Dikar's face, "so high that you could put your Mountain on top of one like itself, and another on top of those, and still not have them as high as the lowest of those. They're so high that there's always mist about their summits, and that's why the Indians called them the Smoking Mountains."

A shadow had darkened Walt's face. "General Fenton was telling me, only last night, how when he was very young he heard over the radio Franklin Roosevelt's speech dedicating a great National Park there, to the enjoyment and pleasure of our people for all time."

"For all time," he had repeated, bitterly, and then had said, "Up there is an Asafric army, Dikar, but its officers don't know we're anywhere within hundreds of miles of them."

He'd been so sure of that, it had been no use for Dikar to tell him about the tracks he'd seen in soft ground, of feet turned in at the toes the way the feet of the Blacks turn in. It had been no use for Dikar to tell him how the breeze had brought him, now and again in the past week, the smell of Blacks very near. Walt had been sure everything was all right, and Walt was lots smarter than Dikar. Hadn't Normanfenton picked Walt to be always close to him?

So the army had marched all last night. This morning, before the sun rose, they had found sleeping places in barns and houses, under bushes, in woods like this one where the Bunch had slept. Almost as good as the Bunch at hiding themselves were the other Americans. They had learned to be, this last winter.

But Dikar, lying by Marilee on a sweet-smelling bed of ferns, had not slept. Through the boughs of the tree over him he'd watched the sky grow pale with the coming dawn. He'd seen the red blush of sunrise touch the tops of the mountains, close now and so high his breath was taken away looking up and up. He'd seen the brightness spread up there.

And he had seen a black speck come into the sky from behind those mountain tops, and another, and another, while a distant low thunder of planes growled in his ears. Before he could cry out there had been a bright flash from the mountain top, and with that the first black egg had dropped screaming from the belly of the first black bird—

A burst of flame swept over Dikar's head, blinding him. The gully side heaved. Its green was cracked with earthy redness. It was all red earth and it was falling down upon him.

"Marilee!" Her name burst from his throat in a great shout he himself could not hear, and Dikar threw himself across his mate, just as the earth came down and buried them both.

THE blackness was a solid thing against Dikar's down-bent face. On Dikar's back was a terrible weight of dark earth, so that his straddled thighs, his thrust-down, aching arms, shook.

Dikar's chest heaved, desperately pulling in dank air out of the black space that was roofed by his back, walled by his arms, his thighs and the earth crushing against his sides.

"Dikar!" From the black space out of which Dikar's failing strength still held the earth came Marilee's cry. "Dikar. Where are you?"

"Here." Hard to talk as to breathe. "Right above you. You—all right?"

"All right, Dikar. My legs—I can't move my legs but—but I think that's because of the dirt on 'em. Oh Dikar!" A sob caught at her voice. "What are we goin' to do?"

"Do?" How long could he hold up this awful weight on his back hold it from crushing Marilee? "Get out of this." But how was he to get Marilee out of this living grave?

"It's movin', Dikar! The dirt's comin' in over me!"

"Just settlin', Marilee. I'm holdin' it."

"If I could only see you, Dikar. If I could only feel your arms around me, only once more."

Only once more! She knew he'd lied. "I'm holdin' it," he lied again, because he could not think what else to say. The earth was alive with movement, alive with its blind will to crush them. Dikar could hear the soft, dreadful rub of the earth as it moved in under him.

Where it moved, Marilee was talking, but not to Dikar. "Now I lay me down to sleep." She was saying the Now-I-Lay-Me the Old Ones taught the Bunch to say each night when Bedtime came. "I pray the Lord my soul to keep. An' if I die before I wake—"

"No," Dikar groaned into the dark. "No, Marilee. You're not goin'—to die." But the terrible weight of earth was growing, it was pressing the strength out of his arms and back.

"Quick, Dikar! It's comin' over my face." It was sliding in under his belly. "Quick! Before—"

Marilee's voice choked off. Dikar's arms let him down. Dikar's arms found Marilee's warm body. Earth, following down, crushed Dikar's body to Marilee's. Somehow his lips found hers.

All of a sudden the thunder was loud in Dikar's ears again, and he could breathe! "Dikar!" a near voice jabbered. "Dikar, man!" Dikar's head flung back and he blinked earth from his eyes as the voice cried, "Dikar, old fellah." There was light in Dikar's eyes again and upside down, in the light was a hollow- cheeked, earth-smudged face he knew.

The face of Walt, his friend.

"Thank God!" Walt gasped, his hands scraping earth away from around Dikar. "Thank God you're alive! When I saw the bank cave in on you—"

Dikar heaved up and was on his knees, and his tight-clenched arms brought Marilee up out of the red earth. She clung to him, and he could feel her quick breathing.

WALT was still jabbering, and now there were hurrays

around them. Dikar saw that it was Franksmith hurraying, and

Bessalton and pimply-faced Carlberger. And there were others of

the Bunch here too, and they were all red with earth, their hands

red and shapeless with earth.

"It fell on us, too," Franksmith burst out. "But not deep, and when we shoved up out, we saw Walt here diggin' with his hands so we came an' helped him."

Dikar wondered that he could hear them all so plain in spite of the thunder and then it came to him that the thunder was much less loud than it had been before. He looked up into the sky. There were no planes in it now.

"Bomb loads don't last forever," Walt answered Dikar's look, "and they'll have to fly so far back to get more that they'll hardly be able to return before nightfall. But the guns are still at it."

Bessalton and Alicekane took Marilee from Dikar's arms and started to clean the earth from her. "Walt!" Dikar went cold all over with a sudden thought. "Why're you here? Is Normanfenton—"

"The President's in a deep cave up ahead; I took him there." Walt's gray-blue uniform, from the stores they'd found at Wespoint, hung in rags about him. "What you said yesterday had me jittery." There was stiff hair on his face and the hair on his head was clotted.

He looked almost the way he'd looked when Dikar first found him, a starved Beast-man in the woods below the Mountain. "You were right, Dikar. The Asafrics laid a trap for us and we marched the army right into it."

"The army, Walt! All killed?"

"Many. Too many. But according to the reports I've been gathering, not nearly as many as we thought at first. Our men dispersed as soon as it began, found gullies like this one, caves, other shelter. Even those who could not find better cover than the woods were so scattered that each bomb or shell caught only two or three.

"We've lost only about six or seven hundred men. That still leaves us nearly five thousand effectives, but we can no longer count on surprising the Asafrics, so a frontal assault on those natural ramparts cannot possibly succeed."

Dikar didn't understand all Walt's words, but he knew what he meant. "Then we've given up. We're licked."

"Not quite." The back of Walt's hand scraped at the stiff hair on his chin. "There's still one slim chance. That's why Fenton sent me through that hell-fire to look for you."

"Why for me?"

"Because if anyone can make good that chance, it's you and your Bunch. Look!" Walt pointed up and up to where Dikar had seen the guns flash this morning. "You see that fold in the mountains, right there?"

"Yes." The flashes were still there, bright against the dark green of the high woods, and the thunder of the guns still rolled down from there. "Sure I do."

"That's Newfound Gap, the highest point on the highway that goes over these mountains. When the Smokies were made a National Park, the engineers built a wide, level place there where hundreds of cars could park while their passengers looked over the view.

"The Asafrics have emplaced their biggest guns there, monsters with a fifty-mile range, commanding not only all this valley, but the whole length of the highway up which we'd planned to steal tonight, to make our surprise attack."

"I know," Dikar broke in. "But now the Asafrics will be watchin' for us an' kill us all if we try it."

"Exactly. They have the range of every inch of it. On the other hand, if we can capture those guns we can still snatch victory from defeat. You see, Dikar, we could swing them around and shell the enemy out of the reaches between the Smokies and the Cumberland Plateau. That would make it possible for our Army of the Tennessee to break through, join up with us and clean up the rest of the enemy forces in the mountains."

"How're we goin' to capture those guns if we can't get up to 'em?"

"Look there to the left." Dikar's eyes went along the line of soaring, dark green peaks up from which drifted a blue-gray haze like smoke from hidden fires. "There. That's Clingman's Dome."

So high was the mountain Walt pointed to that, far above, a cloud blanked out its middle half and its top seemed a monstrous, impossible island floating in the sky.

"It rises a thousand feet above Newfound Gap," Walt was saying, "and there is another battery emplaced there, of automatic air-craft guns, like the archy you fired from the roof when we captured West Point. They're toys compared to the ones at the Gap, but they're placed just right to annihilate the crews of the big ones."

A chill prickle ran up and down Dikar's backbone, but he only said, very quiet, "All right, Walt. We'll go up there an'—"

"Wait!" Walt's voice was sharp. "Wait till I finish." Dikar had a queer feeling that his friend didn't want him to go up there with the Bunch. "General Fenton wants you to understand exactly what the job means."

"I don't care—"

"Listen, Dikar," Marilee's clear, sweet voice interrupted. "Listen to what Walt has to say." She was standing close to them, and the others of the Bunch were gathered around. The Boys' eyes were shining and eager but the Girls' eyes, watching Walt, were shadowed.

"A ridge, along which runs an automobile road, connects Newfound Gap, to the north-east of it, with Clingman's Dome. Its eastern slope, the one toward us, and the southern are comparatively gentle and easy to climb, and so are certainly carefully watched. The Dome's western side, however, is a steep cliff almost as unscalable as that around the base of your Mountain—"

"And you think they won't be watchin' that side. But they'd be crazy not to, if they know we're around."

"If they know our army is in the vicinity they'll certainly be on the alert. But suppose we pretend to withdraw? Suppose, now that the planes have left, we send numbers of men to expose themselves on roads visible from the mountain-tops, apparently fleeing from the valley—"

"The Asafrics will think there's lots more runnin' away, in the woods where they can't see 'em. An' they'll get a little careless—"

"Exactly. If the ruse should succeed it might barely be possible for a little band of men to reach the summit of Clingman's Dome unobserved under cover of the night.

"Might be, Dikar," Walt repeated. "But if you try it, you will be climbing in darkness along ledges so narrow that they will barely give you foothold, ledges clinging to the side of precipices that slant outward to push you off.

"Above you will be Blacks and their hearin' is as keen as an animal's. An exclamation, the clink of metal against rock, even a stone dislodged would warn them of your approach. If you're shot at and only wounded, if you make a single misstep, you will fall three thousand feet or more into what they call hereabouts a Rhododendron Hell, a tangled and trackless thicket."

Walt pulled in breath, put a hand on Dikar's arm. "The chances are a thousand to one against your ever reaching the top, my boy, and even if you do, the odds are almost as great that you'll die up there."

Again he stopped talking for a moment, lines cutting deep into his gaunt cheeks. "That's why General Fenton will not order you to make the try, but has sent me only to ask if you will?"

DIKAR looked up again at the misty island in the sky,

looked down at Walt. The sun was warm on his skin. The smells of

the woods were warm in his nostrils and he knew in that moment

how good life was.

He said slowly, "You know what my answer would be if I had to answer only for myself. But this is somethin' you ask of the Bunch, the Boys to climb up there an' the Girls to wait here below, wonderin' what is happenin' to us up there in the dark. And so I cannot answer, but only the Bunch can answer, in Council."

Dikar saw in Marilee's eyes that what he was saying was the right thing to say. He wet his lips and said, a little louder: "I call a Council. Right here an' now, I call a Council of the Bunch."

Walt pushed back out of the crowd, and the Bunch crowded in close. Dikar looked around him at the Boys and Girls whom the Old Ones had made him Boss of a long time ago. He thought of all their years on the Mountain, and how happy their life on the Mountain had been, and how he'd led them down off the Mountain because of his dream that in them was the hope of a new tomorrow for America.

In that moment between breath and breath, Dikar thought of all the Councils he had called on the Mountain, and all the Councils he'd called in the Far Land after he'd led the Bunch down off the Mountain. This was the strangest Council he'd ever called, here on this torn, red earth with the thunder of the Asafric guns rolling overhead, the Asafric shells bursting all around.

And then Dikar had taken his breath, and was talking again. "You have all heard Walt. You know what it is we are asked to do. You know what it means to America if we can do it, an' you know what it means to us if we fail. What answer do we give Walt to take back to the President of America?"

"What answer could we give?" Johnstone, black-haired, black- bearded, came back at once. "We do it, of course. What say, Boys? Am I right?"

"Right!" yelled Carlberger and Patmara and hook-nosed Abestein. "Right," yelled the Boys, every one of them, and then Franksmith, thin and tall and red-bearded, was saying: "Settled, Dikar. We do it. And you knew all the time that's what we'd say."

Dikar saw Bessalton's hand start out to catch hold of Franksmith and then pull back inside her cloak of black hair, and he saw the look that had come into Bessalton's eyes. "Yes, Franksmith," Dikar said. "I knew what you Boys would say. But the Girls have full voice in the Council of the Bunch, an' I have not heard from 'em. What do the Girls say, Bessalton?"

Bessalton's hair was black as night in the deep woods, but her face was white as new snow with the sun on it. Her lips were gray as they moved and no sound came from them, and then words came from them.

"The Girls say there is only one answer to what is asked, Dikar. The Girls say that it must be done."

And the faces of all the Girls were white and drawn, their eyes dark with agony, but not one Girl spoke up to say that Bessalton did not talk for her.

DIKAR held tight to a knob of rock, just over his head. His weight was all on the ball of his right foot, clinging to a two-inch shelf of rock. His left leg swung free over emptiness.

If Dikar looked down, he would see the night-filled emptiness fall away from him, down and down to a black sough of wind in trees and brush. If Dikar looked down, he would let go. He would follow his look, down into the black depths.

The muscles of his neck tightened to keep his head from turning to look down. All his strength was in his neck, and there was no strength in him to move his left leg, which swung back and out over the awful depths.

For an endless time Dikar hung like that, between the depths and the overhang of the terrible cliff above him.

There was no moon, but when Dikar had climbed up out of the brush tangle that was so terribly far below now, when he'd climbed up above the black whisper of wind in the treetops, starlight had glimmered on the face of the high sheer cliff. Just enough light there had been for Dikar, climbing first, to find a ledge, a slope of earth, ledge again and slope of broken, rotted bits of stone.

Slowly, painfully, Dikar had led the Boys up the western face of Clingman's Dome. Ledge, and slope, ledge and slope again, they had climbed, starlight laying their shadows black on the glimmering rock. Slowly they'd climbed, hardly daring to breathe, almost not daring to move lest the next reach of hand or foot send some little stone rattling down the mountainside and give them away to the Asafrics above.

Death waiting above, death waiting below, Dikar had led the Boys up until this last ledge suddenly had narrowed to give hold only to the balls of his feet, and then had melted into an out- thrust of rock, like a rounded wall corner.

Dikar could see nothing beyond the outthrust of rock. Above him the cliff slanted outward, as if to push him off, and there was no foothold on it, only the one little knob which his right hand clutched. There was no way to go but back.

Before Dikar could get the Boys back to where there was a choice of path, the dawn would be here to show them to the Asafrics. To go back was to give up.

Holding on to the knob of rock, Dikar groped with his left hand along the rocky outthrust, around its bulge and he found a tiny crack into which his fingernails could catch. Pulling in breath, Dikar swung his left leg back, off the two-inch ledge, to get it around the bulge.

In that moment the pull of the black depths took hold of Dikar and his strength ran out of him. He hung against the side of the cliff, and along the ledge beyond him, the Boys waited, unable to help him.

THE cold of the high places lay icy against Dikar's skin.

To make the climb, the Boys had taken off their fawn-skins; they

wore only the little aprons of plaited twigs they'd worn on their

Mountain, and thrust into the belts of the aprons were long,

sharp knives sheathed by leather.

Rifles would have been too clumsy to carry on that climb. The little guns called revolvers would have been too heavy. Knives were better, anyway, for what they had to do at the end of the climb.

But this was the end of the climb, Dikar thought with a quick surge of fear. For slowly, surely, against his strength, against the tight cords in his neck, his head was turning!

For a moment Dikar kept his head from slanting down to look into the black depths. For a last, fleeting instant he looked, instead, into a velvet-black sky.

They were so close, the stars, that Dikar had only to reach out to touch them. They were the same stars that had been close and friendly when he'd gone up to the tall oak on the very top of his Mountain, to dream how some day he would lead the Bunch down off the Mountain to free America.

This was the end of his dream, this fall into the black depths.

No! Suddenly Dikar had strength to break the pull. His head snapped back to the cliff. His left leg swung against the outthrust of rock, groped around it. His toes found something, an edge of stone, slid over and found a hold, a place for his foot as far in as it would go with his thigh hard against the rocky bulge.

Dikar's weight went from right foot to left. The nails of his left hand pried into the crack. His right hand let go. Somehow Dikar was around the corner. He was safe on a wide, almost level shelf of rock. Held breath went out of him and he dropped to his knees, clammy with sweat in spite of the cold.

Dikar looked up. Above him, not twenty feet, was a wavering red glow of firelight and against the glow a sharp-edged black mass.

That was the top of Clingman's Dome. Up to it sloped clean rock on which bare feet would make no sound, an ascent that would be like a level road after what Dikar had climbed tonight.

Like a level road, but it was clean of brush or grass or even boulder to hide behind, and it was pale in the starlight. The smallest creature moving on it would stand out plain, and nothing could live in the sweep of gunfire from up there.

A FAINT rub of flesh on stone turned Dikar to the fold of

rock around which he'd come. A hand groped into sight. Dikar's

fingers grabbed its wrist, held tight. A bare foot crept around

the stone. Dikar had hold of that, was guiding it to firm hold.

Franksmith came around the rock corner into Dikar's arms.

Franksmith's pale face twitched and his gray lips started to

open, but Dikar's palm was on his mouth, stopping the words.

Dikar pointed to the glow of the Asafrics' fire above to show

Franksmith why it was not safe to speak.

And then another hand came around the rock-corner; Dikar helped Alfoster to safety. One by one they came around the bulge, Abestein, Louvance, Patmara, one by one, till Dikar was gesturing the sixteenth, Johnstone, to lie flat and silent on the rock beside the others.

Dikar was down on the rock, his fingers were on the hilt of the knife to make sure it was loose in its sheath. He was stealing up the starlit slope, the Boys following behind.

They made no more sound than the bat makes, flitting through the gray dusk, but in Dikar's ears the drum of his blood was so loud that he was sure the Asafrics must hear it, and where he crawled the stone was ruddy with firelight.

All of a sudden it was black with a shadow. Dikar froze. The shadow was thrown by a sort of low wall of rocks to which he'd come.

He waved for the Boys to come up into the shielding blackness, knew that they obeyed because he could see the blackness take them. He moved to the wall, was motionless again except for his head and shoulders, which lifted, very slowly. Dikar's eyes came above the top of the wall and his head stopped lifting.

The fire was a big pile of red-glowing logs in the middle of a broad space of level ground. The wall ran all around the edge of the space, but on Dikar's left it was broken by a gap through which he could see the beginning of the road to Newfound Gap. Near this a low stone house slept, door closed, windows glinting with reflection of the fire.

Beyond the fire, long and slim and black, the barrels of the eight anti-aircraft guns slanted up against a vast and empty sky. Then there was the long, low line of the wall.

Now something blotched the sharp line of the wall. It was the head and shoulders of a man. The firelight did not reach him, so he was just a black shape to Dikar, but the little hairs at the back of Dikar's neck bristled as his nose caught the smell of him.

The smell of Hashamoto's Black soldiers.

Dikar made out another, and another, and their backs were to him. Each leaned on the wall, peering down over it. Dikar saw that each held a rifle on the wall in front of him, his hands on it. There were twelve and they stood all along three sides of the wall, but there were none on this fourth side. As Walt had thought, they were sure that the terrible west side of the Dome would keep anyone from coming up here.

DIKAR'S lips twisted in a humorless smile. He beckoned

the Boys up to him. He let them get a glimpse of the Asafrics,

waved them down below the wall again, pointed to each of the

Boys, pointed for each in the direction of an Asafric. Nods told

him that they understood.

Dikar pulled his knife from its sheath, and drew a long breath. He came up straight, leaped the wall. He was running silent-footed across the space within. From the corner of his eye he saw the silent, shadowy shapes of the Boys running across the space, fanning out, the firelight glinting on the blades of their knives.

Dikar went past an archie, was close on top of the Asafric he'd picked for himself. His right arm swung up, down. The blade of his knife slid into flesh, scraped bone. Without a sound, the Black pitched over the wall.

Dikar's knife was crimson, but the firelight didn't make it so. A scream, like a trapped rabbit's shrilled in his ears. Dikar twisted to it, saw an Asafric wheeling around to Carlberger, saw the Asafric's rifle swinging like a club.

As Dikar leaped, there was a cracking sound. Carlberger, dropping, had a misshaped something where his head had been. The Asafric screamed again, eyes white in the shiny black round of his face, teeth white between thick, purplish lips. Dikar's knife sliced across the black throat. A new, bright light was all around Dikar as the Black fell.

The new light came from the door of the stone house, open now. It framed a squat yellow man in uniform of Asafric green, with undressed Blacks crowding behind him. The slant eyes saw Dikar in that same moment and the officer's revolver spoke. Dikar dropped, hit the ground with a thud.

THE Yellow officer yelled something and came out of the door, his revolver barking. A Black came out behind him, rifle to shoulder. Another, and another.

Dikar had dropped behind the iron bottom part of an archie in the eye-wink before the officer had shot. He saw a bronzed shape lunge for the Yellow, saw the Boy knocked down by a red streak from the rifle of one of the Blacks. There was something hard under Dikar—the rifle of the Asafric whose throat he'd cut. Dikar grabbed it up, saw the Blacks spreading out from the door of the little house, got the butt of the gun to his shoulder, sighting the Yellow officer, and pulled the trigger.

The officer dropped. "Rifles!" Dikar yelled. "Grab the rifles of the Asafrics you've killed." He brought down a Black, plain against the bright light from the house-door. A bullet spanged on the iron of the archy—another.

Then suddenly the bright light was gone. The door had slammed closed on the Blacks who'd dived back into the house.

"Hurray!" A clear, high voice cried. "Hurray, fellers. We've won," Louvance came out from behind an archy, and an instant later he was knocked down by a red streak from the dark wall of the stone house.

"Cover!" Dikar yelled. "Keep your cover! They're shootin' through holes in the wall of the house! They can see us an' shoot us, but we can't get at 'em. Hold your shooting till you have a mark."

All of a sudden it was quiet there on top of Clingman's Dome, so quiet that Dikar could hear the hard breathing of someone who'd been hurt. He saw that the breathing came from the first Boy who'd been shot.

But the Boy wasn't where he'd fallen when the Yellow officer had shot him. He'd dragged himself much nearer the house, and there was a dark, glistening path on the ground from where he had fallen.

Shots sounded dully inside the house, but the Boy hung against the wall, and he was doing something with his knife. He was cutting wires, Dikar saw, that ran up along the wall to the roof and then straight out from the roof, overhead, to a pole on the road to Newfound Gap.

More dull shot-sounds, but no red flashes. That meant they were coming from a hole in the wall right up against the Boy's body. The Boy slid down along the wall and lay still at its foot. But the wires hung loose now, cut through.

"WHAT—what did he do that for?" a sick-sounding voice asked, right behind Dikar. "What did he do that crazy thing for?"

Dikar looked back, saw that Johnstone had crawled to him in the black shadow of the wall that ran around this space. "Not crazy," Dikar said. "Not crazy at all. Don't you see what kind of wires those are?"

There was a queer sound in Johnstone's throat, and then, "Yeah. They're tel'phone wires—"

"To the Gap. He cut 'em to keep the Asafrics here from callin' for help from there. We can't get at 'em in that house, an' they can't get at us as long as we hide behind these big guns, but they could have held us here till soldiers from Newfound Gap came. Whoever that was, he could have laid still an' maybe been safe, but he gave his life to save the rest of us. It was a brave thing. Who was he?"

"Franksmith." Johnstone said, low-voiced.

Dikar thought of the way Bessalton's hand had come out to take hold of Franksmith. He thought of the look in Bessalton's eyes as her gray lips had made the words, "The Girls say it must be done."

"What do we do now, Dikar?" Johnstone was asking. "We're pretty safe as long as we stay behind these archies, but we can't shoot 'em at Newfound Gap unless we go out in front of 'em, an' we don't dare do that so long as there are any Asafrics left in that house."

"Right. So we've got to get 'em out of there." Dikar made up his mind. "Listen, Johnstone. You crawl back along the wall an' tell all the Boys to start shootin' at the house the minute I whistle."

Johnstone was gone and Dikar, crouched behind the archy, started counting. While he counted to twenty he carefully thought over all that Walt had told him about shooting off the archies. Then he made himself not think at all while he counted to thirty, to forty, only watch how a faint grayness was coming into the sky, how the stars were paling. But as he counted forty-five, Dikar thought about Marilee....

"Fifty," he counted and whistled, loud and shrill. The Boys' rifles crashed, their red fire streaking the night. Dikar darted out from behind the cover of the gun and jumped up into the little iron seat fastened to it, right in full view of the Asafrics in the house. He grabbed a wheel and turned it, and the gun started to move, but a bullet spanged on the gun's iron, another sang over his head, and a third fanned his cheek.

The gun was turning on its mount, but it was turning slowly, and Dikar was a fair mark from the stone house. He pulled at an iron stick which made the gun's barrel start coming down as it turned. Something plucked at his left arm, and something burned across his thigh. The gun had turned so that it was between Dikar and the little stone house, and its barrel was all the way down now, so that it pointed right at the little house.

Dikar pulled another little iron stick.

The archy jumped under Dikar. Thunder deafened Dikar, blinded him. The archy jumped again, and again. Dikar pulled the stick again. The little house wasn't there any more. All that was there was a few tumbled stones, and a big hole in the wall.

"All right, Boys!" Dikar yelled, and he was still so deaf that he couldn't hear himself yell. "All right. Gun crews to your places, quick! Aim down that road to Newfound Gap." Then quietly, as if he were falling asleep, he leaned sidewise and fell out of the little iron seat, fell smiling into the dark.

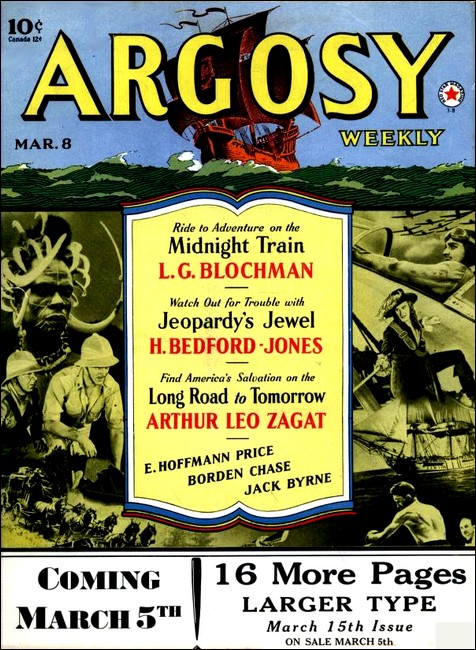

Argosy, 8 Mar 1941, with second part of "Long Road to Tomorrow"

IT is a dark time for America, with her land held by an alien tyrant and her people enslaved; but now each day the army of rebellion grows stronger. Led by Norman Fenton, President of America, this army has marched to the foot of the Great Smokies; the plan is to surprise and vanquish Yeb Hashamoto's Asafric army.

Only Dikar suspects that the Asafrics have arranged a trap. His suspicion is borne out with terrible effect. Suddenly the sky is black with Asafric planes; the bombs rain down on the trapped American army. After the endless moments of terror Dikar and Marilee arise from their hiding place to find that the havoc, though tragic, has not been disastrous. And now Walt Bennet comes to Dikar with a request from President Norman Fenton.

THE heavy guns of the Asafrics are emplaced on the

mountain slopes, commanding this valley where the Americans are

camped. In one spot, called Newfound Gap, a nest of lighter

guns—archies—is situated, and if the Americans can

capture this stronghold they will be able to make short work of

the other Asafric fortifications.

Only the agile, mountain-trained Bunch would have the slightest chance of scaling the cliffs of Newfound Gap, and the odds are a thousand to one against their succeeding. So Norman Fenton asks rather than commands that they undertake the perilous assault.

TO a man the Bunch agree to make the attempt. So Dikar leads them

up the bare, steep mountainside, where the least sound will

betray their presence to the Asafric soldiers. At last they reach

the Gap; they charge the Black soldiers, and the battle is

savage.

Dikar, having maneuvered an archie into position, blows the Asafric headquarters to fragments and so concludes the fight. But then, with victory in his hands, he topples suddenly from his gun-seat, to fall into blackness.

THE earth was springy under Dikar's running feet and its coolness was good to feel. The woods smells—the brown smell of the earth, the green smell of brush and leaves—were good in Dikar's nostrils. Best of all was the silver, happy sound of Marilee's laughter as she ran from him, hid just ahead by a green tangle of brush.

All of a sudden Marilee's laughter ended.

Dikar broke through the green curtain that hid Marilee. He stopped short. The brush had been cleared away here, so that he could see farther through the gray-brown tree-trunks than Marilee could have run, but there was no Marilee to be seen, not even the press of her feet on the moss.

Dikar stood very still, a muscle twitching in his cheek. A line of excited ants hurried through the moss near his feet, each carrying a white egg in its strong jaws. A green snake slid lithely out from behind a gnarled elbow of root, its tiny black eyes bright in its three-cornered, flat head. A bump on a stone was a warty toad, so still that it might be dead. A fly flitted too near it and the toad's tongue flicked out of, in again to its wide, ugly mouth. The fly was gone.

Over Dikar's head a squirrel chrrred, scolding. Dikar grinned and his knees bent, straightened to send him flying upward. His hands, upflung, caught an oak's sturdy bough. His feet found hold on the bough. Dikar stood erect, was climbing the swaying ladder of leafy branches quick and sure as any squirrel. In the green heart of the tree, Marilee was curled on a branching fork, her gray eyes dancing.

Her hair was a silken glory about her, but only her skirt of plaited grasses, her breast-circlets of woven flowers, covered her brown loveliness. Legs astraddle on a bough beneath, Dikar plucked his mate from her perch and held her, arm-cradled, over empty space.

"I'm going to drop you," he growled, deep in his chest, "for thinkin' you could get away from me. Hey! Let go my beard."

She only pulled its golden hairs harder as she laughed. "Fins!" Dikar cried. "Fins! I won't drop you." He settled down in the fork where she had been, held Marilee nestling against him.

"Oh, Dikar." Marilee's voice lifted with happiness. "You jumped up here like you'd never been hurt. You're all well again, Dikar!"

"Didn't I tell you I was?"

"Yes, you did. But I couldn't believe it. I kept thinkin' how the doctor said, when you were carried down here to Norrisdam a month ago, that you wouldn't even be able to walk till the end of the summer."

"Aw! What do those fool doctors know? We got along pretty good without 'em, all the time we lived on our Mountain, didn't we? They don't know anythin'."

"Silly!" Marilee frowned. "Doctors are awful smart. They know a lot—"

"But they don't know as much as you do about the roots and grasses that heal hurts. If it hadn't been for you I'd be still layin' on that bed."

"I'll never forget how you looked, all bloody and torn with the Asafric bullets—"

"That first week must have been a bad time for you. I'm sorry you had such a bad time on account of me." He gathered her closer to him. "Let me show you how sorry I am, Marilee. Marilee." He bent his face to hers.

FOR a long time she would not untwine her arms from

around him, but at last she let him put her on the bough beside

him. He leaned back against the bark of the tree and she nestled

close against him.

"Ah," Marilee sighed, eyelids drooped, moist-red lips wistful. "This is grand, just you an' me alone together. It's like we were back in our tree on the tiptop of the Mountain, lookin' out at the Far Land an' wonderin' what was there."

A shadow stole over Dikar's face. "Maybe I shouldn't ever have led the Bunch down off the Mountain." This was the thought that had been bothering him. "Maybe I was wrong to do that. Look, Marilee. If I hadn't little Carlberger would be alive today, an' Louvance an'—"

"An' Normanfenton would be skin an' bones dried by the wind, Dikar, hangin' in chains from the top of the Empire State Buildin' in New York." Marilee pulled a leaf from a twig. "Walt would still be a Beast Man, dirty an' starvin' in the woods below our Mountain, or maybe the Asafrics would have caught him an' put him in one of their cages in which a man can neither stand up nor sit nor lie down.

"Johndawson—Oh! You know as well as I do that if you had not led the Bunch off the Mountain, there would not be anyone fightin' to make America free."

"We were free on our Mountain, Marilee. We lived our own happy life there, an' nobody bothered us."

"Yes." Marilee pulled little bits from the leaf, let them flutter from long, slim fingers. "Yes, Dikar. We were free. We were happy. We could not hear the whips of the Asafrics on the backs of white men an' women. We could not see the people herded in filth an' sufferin' inside the barbed wire of the concentration camps.

"We were not bein' driven by the guns an' the kicks of the Blacks to slave in factories an' mines, makin' things not for ourselves but our masters. All of those things and lots more, lots worse, were happenin' in the Far Land, but on our Mountain we lived the good life."

"We earned it, Marilee. We worked hard for it, all the years since the Old Ones brought us to the Mountain."

"An' gave us the Musts an' Must-Nots, the Law, by which we should live happy—then died so that we could live free. When the Asafric soldiers came to the Mountain, the Old Ones did not run away an' hide in the woods, did they? They went down off the Mountain to meet the Asafrics. They gave their lives gladly.

"The Old Ones had heard the voice," she went on, "that you yourself told me about in our tree on the tiptop of the Mountain. They had heard the Voice that came into a dark place under the ground where mothers huddled their little children to them while the thunder of bombs rumbled overhead. They'd heard it sayin': 'In these little children lies America's last, faint hope of—of a—'" Marilee hesitated, looked at Dikar, her brows knitting.

"'Of a tomorrow,'" Dikar helped her, "'when democracy, liberty, freedom,'" all of a sudden his voice was clear and certain, "'shall reconquer the green an' pleasant fields that tonight lie devastated.'"

"YOU do remember!" Marilee's face was alight again. "You

do remember the Voice you heard a long time ago in a dream. You

have not forgotten it."

"You have made me remember it, my sweet." Dikar knew now why Marilee had brought him up here into this tree that was so like the tree where he'd told her, first of all the Bunch, about his dream and the Voice in it. "I had forgotten. This morning, when for the first time since Clingman's Dome I came to Brekfes with the Bunch an' looked around the table, what I saw made me forget my dream."

"What you saw?"

Dikar's hands closed into fists, so tight their knuckles whitened. "Eight Boys only, Marilee, are left of the twenty-six I led down off the Mountain. Nine, countin' myself. The rest are dead an' buried."

"There was a smile on Franksmith's face when we buried him, Dikar. His body was all torn with the Asafric's bullets, but there was a happy, peaceful smile on his face. You know there was."

"There was no smile on Bessalton's face, this mornin'. There was no light in her eyes. She sat there, white an' silent, an' if Alicekane had not kept after her, she would not have eaten a bite."

"There are smiles, Dikar, on the faces of hundreds and hundreds of women, all across this land. They have hope now, but they would not have it if you had not led Franksmith an' Bessalton an' all the rest of the Bunch down from the Mountain. Did you do wrong, Dikar, when you did that?"

"No, Marilee; I did right. I did—"

Dikar broke off and his head canted, listening to a call from somewhere below. "Helloooo. Helloooo, Dikar." It was coming nearer. "Dikar. Where are you? Helloooo."

Dikar dropped down to the tree's lowest bough, pushed aside leaves from his face. "Here, Nedsmall." Bushes were threshing, down there. "Here I am." The toad hopped from his stone and the green snake flicked back behind its elbow of root. "What is it? What do you want?"

The bushes parted and Nedsmall came into sight. "Oh Dikar." He looked up and sunbeams danced on his freckle-dusted, impish face. "I been lookin' all over for you." He was the smallest of the Boys. "Walt sent word you're wanted at Headquarters. You're to meet him on top of the dam in half an hour."

"Dikar's wanted at Headquarters?" Marilee was alongside Dikar on the bough, the two standing there without using their hands to hold on, comfortable as if on the ground. "What for?"

"I wasn't told," Nedsmall shrugged. "But I know what I hope," He looked excited. 'I'm tired hangin' around here doin' nothin'. I hope they got another job for us to do."

Dikar heard Marilee's breath pull in. "All right, Nedsmall," he said. "Thanks for tellin' me." He watched the youngster run off.

"So soon," Marilee whispered. "Oh Dikar. Why couldn't they let me have you for myself a little while longer."

Dikar smiled at her, but there was no smile in his blue eyes. "You could have had me all for yourself, all the time, if we'd stayed on the Mountain. But I seem to remember your sayin' that it would have been wrong for us to have stayed there."

"I said that." Marilee laid her little hand on Dikar's arm and her fingers were icy cold, trembling. "An' I meant it. I was talkin' to the Boss of the Bunch then. Just now I'm thinkin' about my mate."

NORRISDAM was a white stone wall that men had built, joining one great hill to another. Its top was wide enough for ten men to walk abreast, and its bottom was so far below the top that men down there looked no bigger to Dikar than his thumb.

That was on one side. On the other side was water, a great lake of water stretching back between green, forested hills as far as Dikar could see. "The lake is as deep as the dam is high," Walt told Dikar as they walked along the top of the dam. "But before the dam was built there was only a little muddy river way down there on what is now the lake's bottom."

"Why was this dam built?" Dikar asked. "Why did they make the lake here?"

"Because the farm lands of eight states, from the mountains of Virginia to the Ohio River, were being washed away by the spring floods, and in the summer what soils the floods had not washed away was cracked and thirsty with drought, the crops yellow and dying.

"So engineers built this dam, and others like it. It was a great thing they did, Dikar. They harnessed the floods and the storms and gave the people of these states fertile fields and cheap power. They gave the people a better life."

"Men built mountains like this," Dikar's forehead was wrinkled, his eyes puzzled, "so that they could have a better life?"

"Exactly."

"They were smart enough an' strong enough to do that," Dikar said, as if to himself. He stared at Walt. "Then why couldn't they keep hold of the mountains they built? Why couldn't they go on making their life better and better? What happened to them?"

Walt shrugged with a bitter smile. "I don't know," he said. "The men who built the mountains were engineers. But the men who had the job of making the better life work and keep on working—they were statesmen." He started walking faster. "We haven't got time to talk about that now, Dikar. General Fenton's waiting for us."

They came to the end of the road along the dam's top and hurried across a wide, stone-paved field where hundreds of men in gray-blue uniforms were lounged. Dikar was thinking that maybe if people had taken time to talk about things like this before it was too late, things would be different now. But he didn't say the thought aloud, because they were going into the stone building that was called Headquarters here at Norrisdam.

NORMANFENTON stood looking out of a high, round-topped

window when Walt and Dikar came into his room. He seemed thinner

than the last time Dikar had seen him, at Wespoint, but he was

still very tall, and his long legs and long arms still looked as

if they'd been hitched on to his body in a hurry and not very

carefully.

But when Normanfenton turned and Dikar saw his face once more, Dikar forgot how clumsy his body was.

His great head, with its gray-threaded, straggly black beard, seemed somehow too big for that ungainly body. Gaunt cheeks were molded by bones very near the surface of the skin, and the skin was scribbled over with a tracery of wrinkles, fine as the threads of a spider-web. Under a broad and thoughtful forehead, eyes were deep-sunken and somber.

In Normanfenton's eyes was pain, and a dreadful tiredness, but in them there was also the soft light of a vision seen far off. Seeing Dikar, he smiled and his whole face seemed to brighten with a warm and tender welcome.

"Ah, my boy." His voice was not very loud, but it seemed to fill the big room as he held out a gnarled hand to take Dikar's strong, brown one. "I have not had the opportunity yet to thank you for what you and your—Bunch did up there on the roof of the Smokies."

"I—uh—" Dikar swallowed, shifted from one foot to the other. "It was nothing, Norman—Mr. President." He remembered just in time how he was supposed to talk to Normanfenton. "Anybody could have done the same thing."

"I don't agree. Perhaps others might have had the same will and courage, but you possess certain unique skills that none without your peculiar background can match. And it is of those particular skills that we have need again, or I should not have sent for you as soon as I heard that you had recovered from your wounds."

"What job do you want me to do?" Dikar asked. "Tell me."

The warm smile flickered in Normanfenton's eyes and then faded. "Captain Bennet." He looked at Walt. "Will you be good enough to send the guard outside beyond earshot and remain at the door yourself so that we can be absolutely certain there are no eavesdroppers?" Walt saluted and obeyed. "When we were on the Mountain together, Dikar," said the President, turning to him again, "I think I taught you something about maps. Am I right?"

"Yes. You taught me a little then an' Walt—Cap'n Bennet—has taught me a lot more since."

"Good. That will make my explanation easier. Look here." Normanfenton took Dikar's arm, led him to the wall to the left of the window. "This is a map of the southern quarter of the United States, Mexico and Central America."

It was a bigger map than any Dikar had ever seen, and he thought it a shame someone had stuck a lot of different colored pins into it. "I didn't think we would be concerned with that region for a long time yet," Normanfenton went on. "But I've had some news this morning—" He stopped, sighed. His fingers tightened on Dikar's arm. "Bad news, Dikar. Danger threatens our cause. A graver danger than ever before."

Normanfenton put his forefinger on the map. "I'm going to send you down there, my boy. It will be a miracle if you can get there. It will be a miracle if you can accomplish what I'm sending you to do. But the cause of freedom can be saved only by a miracle now."

IT WAS very quiet in the room, so quiet that as

Normanfenton stopped talking for a minute, Dikar could hear the

rustling of the ivy that grew thick on the wall outside, the lap,

lap of the lake's waters close to the bottom of that wall.

And the slow throb of the blood in his ears.

"Only by a miracle," Normanfenton sighed, "and so very many things can happen to prevent you from working that miracle. If what I'm going to tell you should leak out to the enemy—" The look of pain deepened in his face. "We must take every precaution that it shall not. You must repeat what you are about to hear to no one, Dikar. Not even to that lovely wife of yours. Do you understand?"

"I understand," Dikar said through cold lips, but he didn't. He was wondering why Normanfenton didn't want him to tell Marilee.

"Not that I don't trust her as much as I do you, but a single inadvertent remark—There are spies in camp here, my boy." The look of pain deepened on the Leader's face. "Matters have reached the enemy that only someone on my personal staff could have known. This matter must not."

He turned abruptly to the map. "Now that's understood, I'll explain what it's all about. First, perhaps, I had better tell you how things stand now."

Dikar moved to the other side of the President so that he could see better.

"After we took Newfound Gap," Normanfenton began, "we—" Dikar whirled away from him. Face suddenly white, he bounded to the window, leaned out.

He'd heard, from outside here, a sudden gasp, quickly cut off, and a threshing of leaves. Someone clinging to the vine to listen had missed his hold and grabbed for a better one to save himself from falling.

He hadn't saved himself! There was a splash from the water below. Dikar saw a blurred form deep under the lake's surface. Then he had vaulted the sill and he was plunging down into the icy waters of Norris Lake.

From:

A History of the Asiatic-African World Hegemony,

Zafir Uscudan, Ph.D. (Bombay), LL.D. (Singapore) F.I.H.S., etc.

Third Edition, vol. 3, Chap. XXVII, pp 988

...INSPIRED by the manner in which Dikar and his Bunch had, at fearful cost, used their woodland skills to breach the Asafrics' mountain breastworks and made possible the union of the two branches of his Eastern Army across the Tennessee Valley, General Norman Fenton resolved to attempt a similar junction between these forces and the rebel Americans who had gained virtual control of the central Mid-west.

To this ambitious project, Viceroy Yee Hashamoto's gunboat patrol of the Mississippi interposed a formidable obstacle. Following the pattern of the tactics by which the Great Uprising had grown from a mere rioting of a few disaffected slaves to the dignity of a major insurrection, President Fenton initiated simultaneous feints-in-force toward Chicago and New Orleans, contriving, through patriots posing as renegade Mudskins, to get word of these to Hashamoto.

The latter at once concentrated his strength on the threatened cities, setting up traps like the one at the Great Smoky Mountains that the Americans had escaped only through Dikar's brilliant exploit.

On May 23rd-24th, Fenton delivered his genuine assault against the weakened forces that had been left to hold Cairo, Illinois, and its vicinity. His stratagem was completely successful. The Mississippi was crossed, and penetration of the Ozark Plateau from the bridgehead thus established.

In the face of these repeated defeats, Yee Hashamoto still sedulously concealed from the Asiatic-African Confederation's Supreme Command at home any knowledge that he was in difficulty. To explain why, we must refer back to Chapter II of this History.

The reader will recall that here we discussed the characteristics that so well fitted the leaders of the Asafric Cabal for the program of world conquest on which they embarked when "Axis diplomacy", having invited them as allies into the arena of Weltpolitik, revealed to them the rotten beams behind the facade of vaunted white supremacy. We also pointed out a psychological weakness, the Oriental preoccupation with "Face."

HASHAMOTO had only to draw upon the Confederation's tremendous military resources to crush the American Uprising, even now. But by so doing, he must admit his own failure. He must admit that a slave whom he had paraded through the countryside, naked and in chains, had out-maneuvered, out-generaled him. He would "lose face." This was unthinkable.

It was also inevitable, unless he took strong measures at once. There were increasingly urgent demands from across the Pacific for explanation of why the flow of cargoes from his bailiwick was so materially dwindling, and the Viceroy was running out of excuses. With each victory, the numbers of the insurrectionists were growing as liberated slaves flocked to their standards. He could not very much longer keep his secret.

From this dilemma, Hashamoto saw one means of escape. The Asafrics' first incursion into the Western Hemisphere had been by way of South America. That continent was still docile. Hashamoto had two tank divisions guarding the Panama Canal, but no threat there was possible.

They were the reinforcements he needed. All he had to do was bring one of those divisions up through Central America and Mexico. Using Texas as a springboard, they could strike the Americans on their exposed southern flank, drive north through the Central Plain and then, facing westward, herd the insurrectionists toward the Rockies.

In the latter range would be waiting the West Coast troops that had so far maintained undisputed control over California and the Columbia River Valley. Caught between two fires, a full half of Fenton's forces would be destroyed.

Meanwhile, relieved of concern with the prairies, Hashamoto's present contingents would be equal to the task of annihilating the remaining rebels.

Viceroy Yee Hashamoto's wireless flashed the orders. Perhaps he was not aware that the Americans could intercept and decode the message. Perhaps he did not care. It was a good plan, and even if General Norman Fenton, in his headquarters at Norris Dam, knew about it, he was helpless to defeat it....

"IT'S a good plan"—there was deep worry in

Normanfenton's voice—"that of Hashamoto's." Dikar shivered

a little. The fawn-skin draped over his left shoulder and around

his brown, strong body was still chilly-wet from the lake, though

he'd been listening so long that the water had dried from his

thighs and his legs.

"We will be helpless against his tanks, once they reach Texas. Here." The General's bony finger rested on the map, just above where the blue that meant water took a big bite out of the bottom of the United States. "They've got to be stopped before they get this far, and that's what I'm putting up to you."

"To me!" Dikar gasped. "How can I stop 'em?"

Dikar could swim like a fish, but he'd been blinded by the splash of his own wild dive out of the window and before he could see again, the spy who had been listening under it had swum too far under water to be seen.

"My only hope, son," Normanfenton answered him, "that they can be stopped rests on you."

The funny thing was that though some of the Boys and Girls of the Bunch had been in swimming where the woods came down to the shore on the other side of Norris Lake, none of them had seen any stranger come up out of it. Dikar had sent the Bunch to see if they could pick up the spy's trail and had returned to Normanfenton.

Now he said, "But Normanfenton, how do we have any chance of stoppin' two divisions of Asafrics? There's only nine Boys left in the Bunch—"

"I said you, my boy, not your Bunch. What has to be done can be done by you alone, or it cannot be done at all."

The listener could have heard only that Normanfenton was going to send Dikar somewhere that must be kept a secret even from Marilee, and now there were soldiers in a little boat out on the lake to make sure no one climbed the ivy again.

"Why should anything be easier for me to do alone than with help?" Dikar asked.

"Please stop breaking in on me like that, young man." Normanfenton's tired smile took away the hurt of the sharp words. "Give me a chance to explain. One man can do what is to be done as well as nine or ninety.

"To get to where I am sending you, you will have to steal through the enemy's lines, through six hundred miles of territory held and patrolled by his troops. Capture will mean a particularly horrible death for you, for me the end of my last hope of checkmating Hashamoto.

"You will need every atom of your skill in moving silently and unseen, and any companion you take with you would only increase your peril."

"All right." Dikar shrugged. "Where am I goin', an' what am I to do there?"

Normanfenton turned back to the map. "You see how Mexico and then Central America narrow," his finger moved downward on the many-colored sheet pinned to the wall, "curving around the Gulf of Mexico to here, where the Panama Canal cuts through it."

"The Panama—That's where the tanks are comin' from!"

"That's where they will be coming from, according to the messages we've intercepted, about three or four weeks from now."

"Three or four weeks! What are they waitin' for?"

"Divisions of tanks cannot move at a moment's notice, my boy, like your Bunch. They've got to accumulate supplies of fuel, munitions, food, to sustain them on the march. Their machinery must be repaired, put in perfect order.

"There are innumerable details to be taken care of to prepare them for a long campaign, even more than usual for these divisions, which have been somewhat disorganized by their idleness. And all this, Dikar, must be done surreptitiously, lest the officers of vessels passing through the Canal observe the unusual activity and report it to the Asafric Supreme Command.

"Viceroy Hashamoto fears his own home government more than he does us," Normanfenton sighed. "And rightly."

"But if it's goin' to take 'em so long to get started an' we already know what they're up to, couldn't we get ready in that time to meet an' fight 'em?"

"Meet them where? They will have all Texas to spread out over, and we have no way of anticipating where they will choose to strike. Fight them how?

"In a battle of movement, tanks can be fought only by tanks, Dikar, and we have none. We have nothing that would give us the slightest chance against them unless—an' that's the whole crux of my plan—unless they can be taken by surprise, unprepared for action, their crews unsuspecting an enemy anywhere near.

"Now," the General went on, "all of this isthmus, except for some narrow stretches along its coast and along a few short, unconnected stretches of railway, remains pretty much the same as it was when Columbus first saw it.

"Where the Sierra Madre range does not thrust its crags to the sky, a thick and well-nigh impenetrable tropic growth bars travel. There is only one practicable route by which it can be traversed, the Pan-American Highway, a broad concrete road that was completed just a year before the invasion. Since Hashamoto does not dare requisition transports to convey his tanks by water, that is the way they must come."

Normanfenton's finger started moving back up on the map. "This way, Dikar, skirting the inward base of the mountains that join the Andes to the Rockies. Through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras.

"And here," the finger paused just before it would have crossed a line that zig-zagged across the picture of narrow land, the colors different each side of it, "as they approach Gautemala's Mexican border, is where they must be stopped, if they're to be stopped anywhere."

"Why there?" Dikar goggled. "Why just where the land's widest of all?" Beside where the general's finger rested a kind of bump stuck out into the water-blue. "I—I can't make out why you should pick that place."

"I'm picking it precisely because the land is widest here, because here the highway passes along the base of the Yucatan peninsula." Normanfenton pointed to the big bump. "Wilderness as the rest of the isthmus is, it is a tamed, gentle region compared to the primordial jungle of Yucatan. And, son, when the Asafric hordes overran Texas and Louisiana and Mississippi, a large number of Americans fled across the Gulf of Mexico to this green hell in Yucatan.

"Many of the boats that carried them were sunk by the guns of the enemy fleet. Many were wrecked by a hurricane. But some reached the shores of Yucatan and Campeche and Quintana Roo, and their passengers found sanctuary in the interior.

"What became of them we do not know. The sisal that was Yucatan's only crop was of no use to the Asafric, and so they did not bother to conquer that region. The underground wireless of the Secret Net never received a response from that green mystery. The jungle swallowed the refugees; they vanished."

DIKAR scratched his head. "You don't know how many there

are. You don't know if they're still alive in there. You don't

know anythin' about them. But you expect—"

"I know this about them," Normanfenton broke in. "I know that they were Americans once and that whatever they have become, whatever the jungle has done to them, if they still live they are still Americans.

"I'm gambling on that, Dikar. I'm gambling my hopes that the Cause I lead may still be saved, if you can reach them and tell them that their countrymen are fighting for freedom and are in danger."

"They'll come out of their jungles, when the Asafric tanks pass by—"

"And stop them." A thrill came into Normanfenton's deep voice, and as he turned to Dikar, he seemed suddenly taller in his faded, gray-blue uniform. "Stop them dead, there in the shadow of the Sierra Madre. Unless they do, we fail. I cannot believe God means to let us fail. I cannot believe that needing a miracle now, He will not help us work that miracle."

He spread wide his gnarled hands, bony and bulging with an old man's net of veins under yellowing, transparent skin. "I send you alone on a long, long road, Dikar, every inch of which will be fraught with peril of death for you.

"I send you into a steamy jungle to find men who for all I know may have turned into savages. I send you to ask them, for the sake of an ideal which almost surely they have forgotten, to attack trained soldiers who have conquered the world.

"By all the laws of reason it is a mad project, foredoomed to failure. I put my faith in that God who created men to be free, that it will succeed. And it must."

...Dikar walked slowly back across the top of Norrisdam. The hushed gray of dusk, sifting down through the tree-clad hills to veil the lake with darkling mist, was answered by a gray hush within him.

Dikar's eyes burned with long looking at the maps that Normanfenton had showed him, hundreds of maps picturing every yard of the way he was to go. Dikar's head throbbed, full to bursting with all that Normanfenton had told him, with all the hundreds of things Dikar must not forget.

Dikar's heart ached with knowing that tonight, for the first time since he could remember, he must leave Marilee without telling her where he was going.

Tonight he was going to leave the Bunch that he'd been Boss of so long. Without a word of goodbye, he was going to slip away into the dark and he had as much hope of coming back to them as—as this twig, shooting over the dam's spillway and down into the foaming flood below, had of ever going back up the River to the woods.

Like that twig, Dikar was being carried along by a rushing river, far and far from the woods he'd loved, far from the Mountain that was his home.

TO Dikar's left and right, along the sides of the

clearing into which he'd come were the little houses that Walt

had called log-cabins when he'd brought the Bunch here to show

them where they were to live. At the other end a great fire sent

its leaping, orange light up into the spreading branches of a

tall oak.

Down the middle of the open space a long table ran, the Girls bustling around it as they set it for supper. The firelight danced on the Girls' smooth, brown arms, on the thighs peeping briefly through the lustrous cloaks of their hair. Almost as tall as Dikar, but black-haired and bearded, Johnstone talked with Alfoster. Nearer the fire, Patmara and Abestein and Henfield threw little stones at a mark they had blazed on the oak.

The clearing was filled with happy laughter, friendly chatter, but beyond the fire the woods were black and the sunset wind made a rushing sound in the treetops.

"Dikar!"

Marilee had seen him. She was coming toward him, her hands held out to him, her body slim and straight. Every graceful line of her, every movement was a song swelling in Dikar's throat, an ache in his arms.