RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

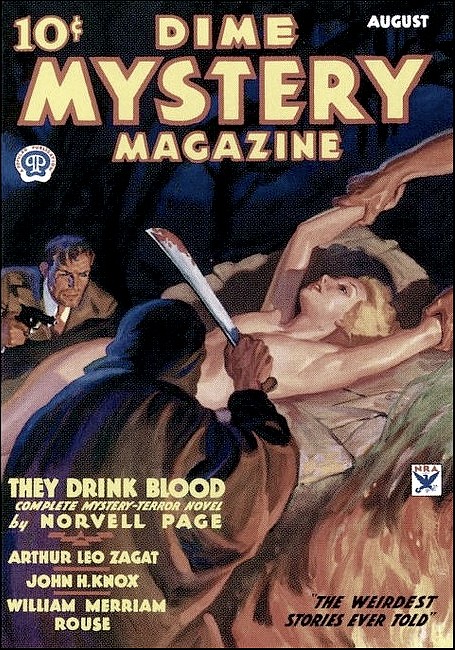

Dime Mystery Magazine, August 1934, with "Snake Drums, Booming"

From distant jungle lands came the crawling ugly menace which

was to reach out and trap Nell Carter in the heart of New York city.

DUSK, slowly creeping between drab facades, made a grimy canyon of the Harlem side-street, and lingering fingers of gray light quenched the radiance of street lamps to mere spots of brightness. Puzzled lines furrowed Nell Carter's piquant face as, long-legged, boyish, in the tailored lines of a tweed suit, she mounted a chalk-scrawled stoop.

"Queer," she muttered. "Wonder where everyone is."

Up and down the block other front steps were crowded with black, brown, and yellow tots, half-clothed and noisy; with slatternly Negro women, gossiping; with flashing-toothed bucks and pluck-browed high-yellow wenches. But there was no one in front of the shadowed vestibule Nell entered. No one. And in this neighborhood of crowded warrens that of custom spilled their teeming life into the open, that was altogether strange ...

Uneasily, the girl felt that in the inscrutable eyes watching her from those other stoops, the slitted, speculative eyes of an alien race, there lurked some furtive expectancy. Her own gray-irised glance sought the nimbus of Neon luminance hat marked Lenox Avenue, and she half turned as if to retreat. Tiny white teeth caught up the thin red line of her lower lip. "The supervisor said I was not to make any calls after dark," she muttered to herself, "that it wasn't safe for a white woman to be alone here at night ... Maybe I ought to take the subway and go home."

Nell's gloved hand tightened decisively around the leather-lined document case under her arm. "It's silly to be afraid," she told herself. "Half the people around here are on Relief; if I didn't come around with their food tickets every week they'd die like flies. They're human after all. Grateful. They wouldn't let anyone hurt me. And besides, it's my own fault that I'm so late. I can't let those six little Thompson children go hungry overnight, just because I've been trying to find out why my other clients suddenly can't get along on what the city gives them when it was plenty till a month or so ago."

The relief-worker's brow puckered as she was reminded of the worrying problem, and she opened the paint-peeled door almost mechanically. She couldn't understand. That starved look had reappeared on the faces of the children; again in the eyes of the adults was the same dumb misery that she had seen when she first began giving them relief. Something had gone wrong—dead wrong. She sighed. "If they'd only help me to help them. If they'd only talk. But they won't, they just get stony-faced and evasive when I question them. Scared-looking, too."

She strode down a long hall toward the narrow stairs she knew to be at the rear. What little light seeped in through the dirt-streaked glass panel in the entrance door served only to emphasize the dismal murk within, to bring into being eerie shadows that lurked in crannies and cloaked formless, intangible menace. As Nell passed each black pool she found herself fighting a scalp-tingling impression that it came alive behind her, that it slithered soundlessly after her.

Odors closed about her; stench of filth and eternally sunless dankness that was underlaid by the musky, other-racial fetor to which all her months of service in Harlem had not accustomed her. Disquiet stirred more and more queasily within her as she became aware of the uncanny hush that pervaded the tenement, the pall of soundlessness where accustomed pandemonium should reign. No shrill voices screamed from one open door to another, there was no scampering of childish feet, no boisterous singing and no brawling such as was the constant accompaniment of her daily round. The place seemed to quiver with silent fear.

Uncarpeted, splintered steps creaked under the social-worker's tread, her heels clicked loudly against wood. The Thompsons were on the top floor, Nell recalled, six children and two grown-ups in a two-room flat. There hadn't been a morsel of food in the place when she had made her first call, last week, and she had rushed back to the office and pleaded with Miss Bailey because of the emergency.

Still in that uncanny hush she passed the first landing, reached the second. It was almost pitch-dark here. Tiny feet scuttered past her and Nell gave vent to a little scream. She could never get quite used to the rats that infested these dwellings. Two dots of red glow were the rodent's eyes, watching her. Hinges creaked somewhere. A line of gray light widened as a door opened, slowly. A whisper reached her. "Oh, Miss Carter!"

NELL gasped, startled. She could see a black hand

silhouetted in the aperture. It beckoned to her, and the

whisper came again, urgently. "Miss Carter." She remembered

whose door this was, and the pounding of her heart

quieted. She moved nearer, and saw a familiar face peering

timorously out.

"I haven't your ticket today, Mr. Brown," she said. "It isn't due yet."

Eyes rolled whitely in a chocolate face overlaid with ashen tint. "Ah doan' want no ticket, missie. Ah wants to tell you sompin', I wants to tell you to go 'way from here."

"What do you mean?" Nell flared. "I don't understand you..."

The black's voice cringed, was entreating. "Please doan' get mad, Miss Carter. Ah doan' mean nothin' bad. Ut ain't good for you to be here jest now. You done been so good to us Ah doan' want nothin' to happen you."

The girl found courage in the other's fear. "Why, Mr. Brown. What could happen to me in this house? I'm taking care of every family here except the Thompsons, on the top floor, and I'm going up to see them now."

"The Thompsons!" A groan seemed wrenched from the man, and his lips were purple. "Oh Lawd-a-mussy! That's where....! Doan' go there, missie. Not there!"

Nell's scalp tightened under her jaunty little hat. "What's the matter with them? What's going on? Why shouldn't I go there?"

"Doan' ask me. Doan' ask." A mask dropped suddenly over Brown's face, the stony, unreadable expression grown too familiar in the past weeks. "But that ain't no place for white folks."

"Rastus," a feminine voice shrilled from within. "You close that do' quick!" Terror quivered in the thin tones. "Close it or—"

The man's head twisted. "Hush up," he called, warningly. "Hol' yuhr tongue, Mamie." He turned back to Nell, his thick-lipped mouth twisting. "Please doan' go up there—Oh Lawd!"

He had slammed the door shut before Nell realized that the squealed exclamation was wrenched from his livid lips by a scraping, ominous sound from above—a sound like a bare foot rubbing furtively against wood. She was cold all over, but she forced herself around till she could stare with widened eyes up the dark ascent, Something bulked up there, black against black. It was coming down, slowly, step by step, coming toward her!

She was rigid. Her throat worked, but she could make no sound. The Thing neared, was on the landing. A stench folded around her, fetid, a scent that spoke somehow of mouldering human bodies cast unburied on the green-scummed bosom of a swamp. It was almost on her; she felt rather than saw its nearness, and fear was an icy stream in her veins.

The Thing slithered past, gliding uncannily. Against dim luminance from below Nell saw its shape, saw that it was a bent, wizened old man. From his gaunt, black face eyes fastened on her, momentarily, eyes that burned redly from deep-sunk pits. They seemed to sear her with hot evil, then they were gone and the twisted shape vanished into shadow. But it left the very atmosphere charged with a vibration of hate, of utter malevolence. Nell shuddered, swayed and caught at the door-jamb behind her for support.

For a moment she clung there, the floor heaving under her feet. Panic had her in its grip, fear of things unseen, of forces beyond the Known. Some weird thing from out the past of these people, some uncanny mystery from the steamy jungles of their ancestral Africa, was reaching out for the children of the Dark Continent who huddled, afraid, in this city tenement. This was no place for white folks. She must run, she must get away from it before it had her, too, in its slimy, reptilian grip! She pushed herself away from the wall, took one step toward the stairs that dropped down to light and safety....

And then she stopped. Her mouth twisted, wryly. She was being puerile, childish. She was in a jitter over nothing: a dark hallway, a scared Negro, a white-haired old Negro who wore no shoes. Were these things going to frighten her away from her job? If so, she might as well give it up. She turned and mounted higher.

She was still afraid; the pumping of her heart thumped in her ears. Thud. Thud. Thud. No—it wasn't her blood, it was a dull thudding from without, sourceless. Thud. Thud. Thud! The slow pound of a drum. Of a jungle drum! Vibrant as a snake's tongue....

Step by step Nell mounted, and step by step the thump of the tom-tom marked her climb. Thud. Thud. Thud. It was coming from above, from the lightless region to which she climbed. It was warning her, warning the white woman to keep away, to flee from mysteries forbidden to her race. Thud. Thud. Thud. It was all about her as she reached the topmost landing, was receiving her into the pound of its slow terror, was beating in every cell of her being.

Thud. Thud. It had halted in mid-beat! The silence was like a thunderclap.

Almost inaudible, a mumbling chant trailed out of darkness. It was coming from straight ahead of her, and for all its faintness something in its intonation sent tremors of fear rippling along her spine. She stared into the blackness, and gradually became aware that the veriest filament of light made an angle near the floor. And it was from just that point that that eerie sound was coming. Nell crept closer, some strange fascination conquering fear. Her hand slid along dirt-slimed wood, 'found a doorknob. It responded to the pressure of her cold fingers, turned. The door moved noiselessly, and the light-thread widened. A gap appeared, just enough for her to peer through.

Hazy twilight made the utterly bare room just visible. The walls were damp-smeared, faded wallpaper peeled away in long strips. The floor was age-gray, splintered. And on it squatted one whose toothless mouth mumbled the incantation she had heard.

Fingers of fear tightened at the girl's throat. This was the man, the very man, who had descended a moment before; and no one had passed her on the way up! His dull black face sloped back from thick, protruding lips to a wig of frizzed white wool that pressed low over goggle-like, sunken eyes. The enormously wide nose was so flat that it scarcely broke the simian, slanting line of his aboriginal profile. From under a scarlet robe, veiling his body, splayed black toes peeped out. And the sleeves of that robe flapped away from pink-palmed hands whose ebon fingers played with—a tiny wooden doll!

NELL'S eyes narrowed. A scarlet, woolen string had been wound around the curious figurine, and the strange being was unwinding it. Slowly, slowly, with infinite patience, the red thread came away, and there was something in the leisurely motion of his hands, in the weird syllables that blubbed from his monstrous mouth, that reeked evil.

A moan wrenched the girl's eyes away from this uncanny sight, a low moan pregnant with anguish. The sound had come from behind her—from where she knew the Thompsons' flat to be. It came again. Soundlessly she closed the door on the weird sight she was watching, and forced herself to that other door across the hall.

Her rap on its panels was loud, terribly loud. But there was no response from within. She knocked again. Even the moaning had stopped. For all the evidence of her senses the flat was deserted. But someone was there, someone ill, in distress. Someone who needed help! The door opened as she tried the knob.

A candle flickered on a dilapidated mantle. Its yellow beam lit a room hardly more furnished than the one she had just seen. A broken-legged chair, a kitchen table. A bed on which dirt-gray rags were tumbled, half-concealing a human form. The face that turned toward her from the pillow was skull-like; fever burned in its pain-ridden eyes. On the floor a semicircle of ragged children, squatted like so many brown monkeys, their cheeks hunger-hollow.

From the other side of the cot a woman, brown arms crossed over an ample bosom, exclaimed, "Who dat?"

Nell kept her voice steady. "Miss Carter. From the Home Relief. I've brought your tickets."

Mrs. Thompson came around the bed, reaching a hand whose boniness contrasted startlingly with the rotund curves of her kimonoed figure. "Gimme," she grunted. "Gimme."

"Wait a minute. I want to have a talk with you first." Nell had dispensed only emergency relief last week; on this visit she was supposed to probe more deeply into the family's affairs, discover what other aid they needed. Clothing? Medical care? Her expert eyes roved the children's faces. Good Lord, they couldn't have had much to eat since she was here! What had been done with the vouchers she had gone to so much trouble to obtain? Here was the old problem again!

"No need talkin'. Gimme the tickuts an' go 'way."

Nell didn't resent that. The attitude was all too familiar and she knew how to meet it. But something else was troubling her. She sniffed. What was that pungent aroma—like aromatic leaves burning? Where were those wisps of smoke coming from, coiling greasily in the air? They seemed almost alive, almost like gray serpents twisting. Her eyes followed them. That was not shadow in the farther corner, where the candle-light did not reach, It was an old woman, haunched over a caldron suspended from a tripod of three sticks bound by a red cloth. The smoke was coming from that iron pot, and underneath it a little fire of splintered wood burned on a metal plate. Bits of scarlet cloth were twisted in the multitudinous tiny braids that bristled from the black crone's head, and her beady eyes glittered as they watched the intruder. From outside came the faraway honk of an automobile horn, the rumble of a passing truck, the murmurous voice of New York. Otherwise Nell might have been in some mountain hut in Haiti, some thatched kraal in faraway Dahomey. She stared incredulously, her skin prickling. And then her training came to her aid. Never show surprise, wonder, in dealing with your clients. Accept all that you see without comment. Be nonchalant, poised. She brought her eyes back to the Thompson woman.

"Yes, Mrs. Thompson. There is need to talk. You see," she managed a smile, "we want to help you all we can, not just hand out tickets."

The other's eyes were hostile.

"You kain't help us. No'un kin help us 'cept—"

WAS it the old woman's sudden movement that had halted

the sentence, the sharp hiss that came from her? Nell

ignored it. "Oh yes, we can help you," she urged gently.

"For instance, your husband seems to need a doctor. I'll

order one sent in tomorrow morning, and it won't cost you a

cent. What is the trouble with him anyway?"

"Nothin'. Ain't nothin' de matter a' doctor kin help."

The investigator abandoned the point, tried another angle of attack. "And then you don't seem to have been getting the right things for the children to eat. They look just as poorly as before. What did you get with your orders?"

The mother's mouth worked. "Got de right things. Ain't no 'un kin tell me whut my kids need to eat."

"I have no doubt. But perhaps you didn't get enough. Maybe I can tell you where to go to get more for the amount on your tickets. Your grocer may be cheating you—we sometimes catch one doing that. We don't want your babies to be hungry when the city gives you enough for them. We want them to grow up healthy and happy even if your husband hasn't any work. We want them to be strong men and women with straight bones and sturdy limbs. Don't you?"

"Sho do." The woman's voice broke, and a tear rolled down her brown cheek. "But—" her lips quivered—"but there don't seem to be no way. Not ef'n Ah is gwine save Pompey from—" Her hand went suddenly to her mouth, and fright widened her eves.

Nell realized something unintended had slipped out, pounced on it. "Mrs. Thompson," she said sternly. "I know what you've been doing. You haven't used the vouchers for food, you've given them to somebody because your husband is sick. Haven't you?"

"I—I—"

"You have! Who was it? This woman? This—" the word witch almost slipped out—"old lady?"

"Y-Yes." The monosyllable ripped from the 'Negress' tortured lips. Then she tossed her head defiantly. "Mam' Julie be a mamaloi from Haiti. She be the on'y one kin save Pompey from de bocor who make de death ouanga against him, de witch-doctor who unwin' de thread of his life. Ah's got to pay her an' Ah ain't got no money." Her choked voice rose at the end to a shriek.

Nell gasped. She had plunged into unexpected depths here, was touching incredible things. For an instant, inborn, unacknowledged terror ran riot within her, fear of Black Magic, of unreal, horrible things from the earth's beginnings.

"So that's what it is!" Her small fists clenched, her eyes flashed. "You've been giving your children's food to a witch. A witch! Great Heavens! And she's been selling the tickets to some grocer at half price. Well, it's going to stop—stop right now. Do you hear me?"

Mrs. Thompson's eyes were like a trapped animal's; they darted from Nell's irate face to the crone's darkly brooding countenance. "Ah kain't," she groaned. "Ah kain't stop now. We'll all die ef'n Ah does."

"It is going to stop," Nell repeated, her voice quivering. "I'm going out right now to call up the Children's Society and the Health Department. They'll clear out this mess, quick enough."

"No!" the mother screamed. "No! Doan' do thet. They'll take my chillun away from me. They'll take 'em away an' not let me see 'em no moah. Oh please doan'. Please." She thumped to her knees, clawed at the hem of Nell's skirt. "Please doan'." The youngsters were crying openly, sobbing and wailing in a harsh chorus of fear and grief.

THE white woman bent, put her hand on the mother's

shoulder. "I don't want to do it," she said, the anger gone

from her tones. "I don't want to take your children away.

But I shall have to, for their own good, unless you promise

me you'll stop this witch business. If you'll swear to use

the vouchers properly, if you'll let me send in a doctor

tomorrow to treat your husband and promise to do what he

says, I'll let you keep them."

Mrs. Thompson looked up at her, her dark face working in anguish. Words trembled on the pendulous lips. But from the corner where the crone still haunched an angry hiss came, sibilant, venomous. It pulled Nell's eyes to it. She saw quick movement among the rags cloaking the hag, saw something dart from them, a green flash that stopped, suddenly, and was an emerald snake, coiling! From its uplifted, diamond head a scarlet tongue flickered, and its face was shudderingly human, quiveringly demoniac.

The scene froze; a nightmare paralysis held Nell rigid Only her eyes were alive. They mirrored the shadowed room, the sick man on his filthy cot, the tortured woman kneeling at her feet; the black sorceress haunched over her caldron and the coiled reptile, its scales green-glowing, its darting tongue like a tiny flame. They saw, as through a mist, the half-circle of gray-faced, starved pickaninnies....

It was the silence, the close-lipped, brooding silence of the mamaloi, that was so terrible. If only the hag had spoken, if only those thrust-forward, wide lips had opened to pour forth entreaty, argument, invective, the white girl could have found words to combat her. But she squatted there on her haunches, a crouched, scarce-human threat, and mumbled strange cadences that never lifted to the level of hearing. And all the while her little fire flickered bluely, the gray smoke-coils drifted from her black-bellied pot and undulated heavily in mid-air, the green snake poised its affrighting head above its spiraled tail....

A child whimpered. Nell's eyes flicked to its face—and the spell was broken! The tot, no more than three, was big-bellied with famine, sunken-cheeked. She could almost see Death's finger trace his mark on the tiny brow. No! Not if Nell Carter could prevent it. "Well," she pushed out between clenched teeth. "Well, how about it? Do you promise?"

The woman's body quivered, jelly-like. Her lips moved soundlessly, and Nell knew that she prayed. From somewhere came a breath of cleaner air and the snake uncoiled, skittered back to its hiding place in the mamaloi's rags. The torture went out of the mother's eyes and a light came into them, a light that had not been there before. "Ah, promises," she said. "An' may de good Lawd he'p me keep mah promise." She sobbed. "Ah'll gib de vittles to mah chillun."

"Good woman!" Warmth swept through Nell's veins, exhilaration at her triumph. "Here are your tickets, then." She zipped open her document-case, fumbled within. "You sign here, remember...." Her voice was crisp, businesslike once more.

The black crone lifted to her feet. She upended the black caldron, spilling its contents on the stick-fire, quenching it. She glided across the room. From the corner of her eyes Nell watched her, saw her stop at the door. And now, suddenly, her sere face was contorted with hate—with something more fearful than hate. Her shaking, claw-like hand was upraised—and from between her twisting lips strange accents squealed. The meaning Nell could not fathom, but the syllables burned deep into her brain:

Aia bombaia bombe!

Lama Samana quana!

Evan vanta, à Vana docki!

No, the girl did not know the meaning of the sounds, but she knew that it was an invocation to obscene gods whose abode was in the foul morasses of some distant jungle, knew beyond doubt that the priestess of evil was crying malediction down upon her, was cursing her with an ancient curse.

The crone threw a pinch of green powder into the air—and vanished. But Nell shuddered as she realized that there were yet before her those long flights to the street, those long dark flights where shadows crawled—anything might happen!

THERE was light on the landing below Nell Carter when she left the Thompson apartment, a pin-point flame that danced and flickered at the tip of a fly-blackened bracket, serving only to make the shadows that lay in the door embrasures blacker still, Those shadows were like huge black beasts, lying in silent wait for her. She could almost see them breathe.

The girl hesitated, her hand on the grease-smudged banister. Should she turn back, send one of the children out for a policeman to escort her from the building? Her small mouth twisted in a mocking smile at the thought. She was getting as jittery, as superstitious, as the Negroes themselves. Afraid of the dark, like a five-year-old! And besides, if she did that, if she betrayed her trepidation now, all that she had gained in the recent conflict of wills would be lost. The witch-woman would regain ascendancy over the Thompsons, and the children would go hungry once more. She had to go ahead, alone. She had to.

The start was the hardest. Once in motion, running down step after step, the tattoo of her heels somehow comforting, courage seeped back to her. One flight was behind her. She whisked past the landing, started another. In moments now she would be out in clear, clean air, away from the gloom of this fear-filled house, away from its grisly, weird silence. And she would never again enter a Harlem tenement after sundown!

This next landing, just ahead! Why was it unlighted? Why was it so dark, so unearthly dark? What were those green spots of light that appeared so startlingly, that leaped up at her bringing blackness with them?

A bubbling shriek formed on Nell's lips—was never uttered! For the black was tangible, all about her, was a cold, clammy ebon jelly that swamped her, that bore her down, struggling, that flowed over her, weighty, choking, reaching its chill tentacles into her mouth, her nostrils.

She struck at it with her fists; they sank into the soft mass without effect. She kicked, frantically, frenziedly. The Thing gave way before her struggles with little, sucking noises, infinitely fearful. She could get no air, but grave-smell was in her nostrils and gigantic emerald orbs whirled before her eyes. Whirled dizzily, growing till they were world-size, cosmic-size—whirled till her brain was whirling too—till green evil took possession of her senses—of her very soul.... Somewhere a serpent hissed, sibilantly....

A DRUM thumped, muffled. Boom. Boom. Brrroom! Boom.

Boom. Brrroom! The savage sound beat into Nell's brain;

beat life, consciousness back into it. Boom. Brrroom! She

opened her eyes.

She could see neither drum nor drummer, though the muffled beats went on, slow, unending. She could see nothing but walls of stone, a floor of stone whereon lay the half-shell of a coconut, a little light floating on some liquid within it. Above was vaulted darkness; ahead of her the dim illumination was swallowed by darkness. From somewhere out there came the ominous drum-beat. Boom. Boom. Brroom! She was lying on something soft, and it was soothing to the weariness that ached dully in every fiber of her body. But there was a steel band around her wrist, a chain from it that arcked to a ring sunk deep in the stone wall beside her, that clanked as she moved! Nell sat up, her heart pounding, and screamed! The shrill sound echoed and re-echoed—and the unseen drum mocked her with its muffled unresonance. Boom. Boom. Brroom.

She screamed again, "Help! Help!" and again her voice was swallowed into echoing 'silence. She lifted to her feet, surged against the chain. The ring bit into her arm cruelly, jerked her back.

Wings fluttered, in the shadow to her left. Nell twisted to the sound. Something white was moving there, something white and small. The wind of her sudden motion flared the shell-light a bit, and she saw that it was a rooster, a white rooster, saw that a chain from a band around its ankle was fastened to a ring in the wall.

Boom. Boom. Brroom.

God Almighty!

Eyes were on her, eyes bored into her back. The girl, wild-eyed, swung around at the end of her tether. A bearded face stared at her from the other edge of the candle-light; a bearded face, long flat nose, glittering eyes. Horns! A goat! A white-skinned goat was chained to the wall as the rooster was, as she herself was chained! A goat!!

Boom. Boom. Brrroom.

Goat! Rooster! Girl! Icy fingers stroked Nell Carter's spine. White girl! White rooster! White goat! Where had she read of that combination, that somehow unholy, meaningful combination?

Brroom. Bom. Bom. Brroom. The drum cadence changed suddenly. BOOM! And stopped. Another sound slithered into the girl's consciousness, the padding sound of bare feet. It came from the long reach of shadows there ahead, came nearer, nearer. Horror was approaching.

Nell quivered as she stared past the faint light. Horror was approaching—was in the nimbus of pale luminance. It was staring at her with baleful eyes. Horror in the shape of a weazened black man, a scarlet turban hiding his white hair, scarlet robe draped about his age-bent form. The Thing on the stairs, the squatted sorcerer who unwound life from a tiny wooden doll, stood there in the flickering light of the shelled candle. And triumph edged the thick oval of his protruding lips!

A GREEN coil slid over his shoulder, around his neck. The

green snake lifted its diamond head and seemed to whisper

into the papaloi's ear! The chain clanked as Nell shrank back. And the sound roused fury in her. "You—let me go! Let me go at once! How dare you do this to me? How dare

you?" The evil smile on the black face deepened, became

more sinister. "I dare all. These are my precincts, not

yours. It is you who have intruded—you who must make

recompense."

Nell felt surprise at the preciseness of his utterance, the purity of his speech. Strange, utterly strange, coming from that barbarically bedecked ancient. It was more eerie, more uncanny, somehow, than everything else that had happened. But she straightened, tossed her head. "I have intruded! By trying to help your people, by trying to save them from their own folly?"

"By crossing the ancient gods!" The slow words dripped from him, coldly menacing. "By bringing your white philosophy, your white religion, into the domain of Legba and Dambella. By daring to deprive Ayida Oueddo, the serpent goddess, of her due!" At this last queer name the snake's head jerked, minutely, as if it had heard its own name spoken.

"I have no concern with your gods!" Nell retorted, eyes smarting with anger. "My clients can worship the devil himself for all I care. But when that worship takes the bread from the mouths of their children it is my concern, and all your tricks and mummery aren't going to keep me from fighting it."

The baleful glow crept back into the old man's eyes. "Tricks! Mummery! You know better than that, white woman, you have felt the night itself grow real about you and overwhelm you, who have looked deep into the eyes of Papa Agoué himself. How came you here? By tricks and mummery?"

"I—" The girl's mouth opened, and closed again. What was it that had overwhelmed her there on the stairs, that vast outpouring of black nothingness that was yet solid? What were those green eyes that had stared into hers and grown large, whirled large as the cosmos? She had sunk deep, deep, into their depths....

"Ah, you cannot answer me. But I know it. I, Vôduno of Vôdumnu. I, Ti Nebo, priest of the ancient rites, I know! And she knows—" his hand went up to stroke the snake's head that bowed to meet it—"the living incarnation of Ayida Quedda. She knows. But enough of this. You have tasted of the power of voodoo." He broke off, and suddenly his face was a stony, horrific mask from which tiny eyes glittered like black, hard marbles. "Have you heard, by chance, of the goat without horns?"

Something in the way he asked the question, in the slow, malevolent way the words dripped into the dim vault, struck new terror into Nell's heart. "The goat without horns!" What was there about the phrase that made it so infinitely, obscenely menacing? Nell, wordless, shook her head.

"You have not? But you can guess its meaning. Well—if you would not be the goat without horns this very night, listen to me, white woman, and obey!"

SHADOWS crawled behind Ti Nebo, black shadows that were alive. Fear was a living presence in the dim reaches of this stone chamber that was out of the world she knew, "What do you want of me?" Nell whispered. "What do you want?"

The ancient nodded slowly. "You are to go among us with ears that hear not, with eyes that see not. You are not to question what is done with the vouchers you bring. You are to open no door that is not opened to you. And you are to forget, utterly, what you see this night."

Ears that hear not! The meaning crawled snakelike into Nell's shrinking brain. Eyes that see not! And the alternative—the goat without horns! What, in the name of God, was the goat without horns? Frightened speculation beat at her bewildered brain. The horned goat stalked to the end of its chain, she saw that its blue eyes were fixed on the black priest. And she saw in those eyes, in those animal eyes, a brooding horror of things unseen, unguessable! Fear in the eyes of a goat!

What was it a goat could fear? Death? What does a beast know of death? Did that horned beast see something she could not see, some monstrous shape, some formless elemental hovering about the scarlet-robed papaloi around whose neck coiled a green snake with a half-human face? She shivered. It was cold, deathly cold. But the cold was within her.

Starving children grow cold before they die! Other eyes swam before her vision, piteous, entreating eyes watching a mother's hands for food that would never be given to them. Eyes of hungry children. A voice spoke; she was startled to hear that it was her own. "No! Never! You can kill me, do anything you want with me, but never while I live will I let those little children starve! Never!"

The snake arched above Ti Nebo's scarlet turban, a curve of emerald threat. And somehow the papaloi's visage took on the uncanny, half-human, wholly demoniac cast of the reptile's countenance, "You will live," his tones, suddenly deep, intoned. "You will live—and you will obey!"

And, on the word, he vanished! Nell tried to tell herself he had merely stepped back into shadow—but no pad, pad of the naked, splayed black feet came out of the darkness.

As if fascinated, the girl strained toward the tiny flickering flame in the coconut shell, stared at it, and shuddered. This was New York, she told herself, New York and not some mountain hut amid the tumbled crags of Haiti. Outside somewhere were automobiles, and traffic lights, and blue-uniformed policemen patroling. This was New York—but she knew that in this vaulted cellar—it must be the basement of the tenement she had entered, was it only an hour ago?—in this stonewalled enclave she was as far from the great metropolis as if some genie had transported her to the jungle depths of the Voodoo Isle.

The Voodoo Isle! From its dark mountains something had come across the seas, a foul something had come to this black Harlem, this gathering of dark-skinned races in the heart of white New York.

Voodoo! In Africa, in Haiti, in Jamaica, deep in the miasmic depths of the Dismal Swamp, in the night-shrouded mystery of the cotton-fields, in the mysterious, mangrove-screened bayous of the Mississippi's delta, wherever the children of its primeval votaries had been gathered to fulfill their toilsome destiny, the mysterious snake-worship had followed to take its toll. And now it had followed them once again, to the northern city where civilization had reached its flower. It was here, here in New York. And she, because she had threatened its reign, because she had snatched one victim from its coils, she was in its dread clutch. Black, slimy, mysterious ... she was its prisoner—she and the rooster and the goat. Great God! What were they going to do with her? What would happen next?

"You will live—and you will obey!" The voice of the weird priest of the weird religion rang in her ears. Nell sank to her knees and prayed to her white God, prayed for strength to withstand the horrors that were to come.

IN the darkness a drum was beating, thumping its savage rhythm, pounding its primeval cadence. From beyond the darkness it came, from beyond the flickering halo of light cast by the little flame floating within the shell that looked like half a blackened skull. Boom. Boomboom. Boom. Another joined it, and another. Pounding, booming sound reverberated within the vault, reverberated within Nell's aching brain. Boom. Boomboom. Boom.

Now that booming, that dreadful booming was loud; now it died down, drifting away, it seemed, so that it was a faint mutter of rolling thunder in the distance, of cadenced, rhythmic thunder. Now it was nearing again, louder, louder; boom, boomboom, boom; and with it other sounds were coming, the shuffling of many feet, the low chanting of many voices. Louder the boom of the drums, louder the chart of the singers; nearer, nearer, till Nell could distinguish words:

Papa Legba open de gate!

Papa Legba open de gate!

Papa Legba youah chillun come!

Papa Legba open de gate!

Over and over, over and over, boom of drum and chant of singers, till her own heart pounded in time with the pounding chant, thudded in time with the thudding words:

Papa Legba open de gate!

Papa Legba youah chillun come!

Papa Legba open de gate!

The gate to what? a fearsome voice whispered in the ear of the shuddering girl. The gate to what?

Shuffling feet, many shuffling feet, made whispering sound in the darkness, many feet shuffling in time to the pound of the drums, to the thump of the chant. Boom. Boom. Boomboom. Boom.

Papa Legba open de gate!

The fetid smell of close-packed bodies came to Nell; sweat-smell, toil-smell, jungle-smell underlying all. Somewhere out there in the blackness was a throng of unseen, swaying to the thud of the drums, intoning the mysterious unmusical chorus. Thud. Thud. Thudihud. Thud.

Then silence crashed. Quivering silence more dreadful than sound. Long silence in darkness that veiled what horrors? The girl strained at her chain, strove to pierce the gloom with aching, frightened eyes.

A single voice, a cracked female voice, squealing:

Ayida Ouedda, goddess of snakes,

Come to us, come, as the lightning breaks!

And lightning-glare ripped the darkness, flared blindingly! It vanished—but a picture persisted in the white woman's dazed eyes—a picture of a huge coiling serpent in mid-air, a serpent with a woman's face, black and eerily beautiful; and beneath it a sea of upturned black faces, of black hands raised imploring, beseechingly to the snake-woman.

Now light was growing in the darkness beyond; dim light, sourceless. The faint muttering of drumheads rubbed by black hands grew as the light grew. Space extended itself as brightening light revealed arch after stone arch progressing on and on—till far down at the other end Nell could see squatted forms, row upon row; shiny faces, black, and brown, and lighter tan; could see white eyes rolling, white teeth gleaming.

The drummers were nearer, here close to the shell-light, gigantic naked Negroes sweating as their black hands rubbed gray skins stretched taut over upright cylinders that were the drums. And such drums! Hollowed tree-trunks cut off, the wood age-blackened. The center one three feet tall, the others shorter, uneven. And around each cylinder a snake was carved, carved so lifelike that for an instant Nell thought they moved.

There was a long table here too, stretched across the space, a table covered by a white cloth. And on it a cone-like mound of cornmeal surmounted by an egg, a small wooden snake stretched horizontally atop an upright stick, a wooden bowl. And a long-bladed, cruel-edged knife....

The drums were talking, growling in forgotten accents a tale from out of vanished years, a tale of angry jungle gods demanding propitiation; a tale of long-buried threat, of reawakened fear.

To the left of the altar Ti Nebo stood, a figure of dread in his scarlet robe, his lurid turban. To the right, where the drummers were, stood the old crone Nell had fast seen bent over a black caldron. But age was somehow gone from her figure now. She stood erect, lithe, springy as Nell herself. From her shoulders, too, hung a scarlet robe.

THROUGH the muttering talk of the drums a hissing

sounded. Nell saw that the cheeks of the woman, of the

mamaloi, were puffing in and out, in and out, like

a pulsating bladder. It was she hissing, snakelike. A

sinuous wave rippled through her body, another. She was

turning, hissing and writhing, in serpentine fashion. A

scream aborted in the girl's throat as she saw beady eyes

glittering in the black face, saw a red tongue-tip darting

in and out, in and out, flickering as the snake's tongue

had flickered. The voodoo priestess was advancing now,

advancing in a curious glide, while still she hissed,

while still her little body undulated, while still her red

tongue flickered between her lips. She moved erect, yet

somehow it seemed she crawled—crawled on her belly

along the floor! The chained white bird was rigid, its red

comb erect, its little eyes fastened on the snake-face of

the coming mamaloi. Her black hands writhed out from her scarlet robes, as the green snake had writhed from her

rags. Her fingers touched the bright steel chain—and

it fell apart.

Faster the drums thumped, faster, faster. Staccato thumping, grandfather of jazz!

Black hands clutched the rigid bird, lifted it high in the air. The drums rumbled in triumph, and Ti Nebo's arms thrust above his turbaned head as the cock lifted. The sorcerer's voice was like ripping silk: "Ybo, the hour is come. The hour is come, Ybo. The hour of blood."

Was it from the drums that the soundless vibration came, the vibration that filled all space, the reverberant vibration that was a presence in the room? Was it from the snake drums, booming?

It was the drums that pounded, pounded, frenziedly in a tangled, quick, yet ordered rhythm as the mamaloi whirled, spun like a top, faster, faster, till she was a mazy whirl of scarlet at the apex of which was her black snake-face and the white, wing-beating shape of the sacrificial cock. And suddenly a black hand darted, reptilian, to the rooster's neck. A sudden twist, and the comb, the head was gone as still the priestess whirled. Blood spurted from the headless neck, spurted fountain-like....

Ti Nebo had seized the wooden bowl, had snatched the headless bird from the whirling woman's hands. The blood poured into the bowl ... wings beat feebly against the papaloi's arms.. .. The priestess collapsed, lay writhing on the stony floor ... the drums muttered into silence.

And Nell felt pent-up breath whistle from between her white lips. The warm smell of new-spilled blood was sweet in her nostrils, the jungle-rhythm of the drums was in her brain. A cry burst from her throat, a cry that had the very timber, the very sound of the shrill, exultant cries that burst from these other throats, the black throats of the staring, swaying crowd far back in the buried voodoo temple.

An exultant cry! Oh God!

The blood-spattered priest whirled to her. There was triumph in his face! No! Please God, no! She was not as these. Not as these. Not yet! Nell's hand flew to her mouth, from which that cry had come, and her heart pounded.

"Our Father which are...." She murmured the childhood prayer. And suddenly she knew that these things she was witnessing were foul and horrible.

Triumph faded from the papaloi's face. He signed to the drummers. A new rhythm pounded on the quivering air.

"You will live—and you will obey," was what he had said. Obey that black-faced devotee of a religion of blood and fear?

Never!

But the drums were beating, and the scarlet-clad priest was sprinkling meal on the floor, sprinkling strange designs of intertwined circles, stars, tangled lines. The drums thudded, and the ranged congregation beyond were silent in a hush of expectancy. Nell saw them clearly.

Why! These were no savage votaries of a savage faith. These were her clients, the men and women she had fed and clothed, whom she had aided in their distress. There was Abe Johnson, there Mima Lewis, there Erasmus Jones. Hattie Carbo's eyes were white orbs glowing out of black and twitching face. And in the very front row, conflict evident in every line of his contorted, chocolate-brown countenance, was Rastus Brown. Rastus, the man who had warned her, defying his own fears, warned her to flee this house accursed.

The drums had called them here, the old drums and the old gods. The drums had called them here for their own undoing. And Nell knew, now, that the struggle in which she was engaged, the battle with the forces of ancient evil, was not for herself alone. She was fighting for them, for the bodies, the souls of the childlike, pitiable people who had been her wards these many weary months. If she failed, if the prophecy of the papaloi came true, and living, she obeyed his command to go among them unseeing, unhearing—then they were lost. Souls and bodies they were lost. For that to which she was to blind herself, to deafen herself, would be their exploitation by the unholy pair!

Iron entered Nell Carter's soul, iron of the old Crusaders, of the Puritans, of the missionaries who carry the Cross into distant, hostile lands. She would not fail, she could not fail.

And the drums boomed, softly, and the red-robed papaloi traced weird patterns with trailing corn-meal. The gory sorceress groveled before the uncanny altar, and something breathed in the room that was neither man nor beast.

And the horned goat watched her with its blue eyes in which fear lurked—and something else.

He knew!

TI NEBO was finished with his tracing of powdered designs. He moved slowly back to his post at the altar's left. The black crone lifted, stood swaying at the right. The tempo of the booming drums quickened, grew more ominous.

What horror was to confront her now Nell could not know, but she knew that the time of her supreme test was at hand.

The drums thumped and chanting voices took up the rhythm once again, chanting voices pounding:

Papa Legba open de gate!

Papa Legba open de gate!

Let her pass to de promised lan'!

Papa Legba open de gate!

Let her pass.... Nell's throat choked as she heard the change in the invocating: "Let her pass to de promised lan'." It was she they meant. Nell Carter, and the "promised land"—oh mockery—was the dim half-world ruled by the jungle gods!

Papa Legba open de gate!

As the drums thumped the eerie light dimmed, that hitherto had illumined the cavern. No, it did not dim, it drew in, its margins narrowed, till all she could see was the white clothed altar, and the statuesque, red-cloaked figures at its either end! These, and the crumpled heap of blood-spattered feathers that once had been a proud white cock.

Papa Legba open de gate!

A blue flame sprang into being, where was the central triangle of the design Ti Nebo had made. It ran swiftly along the powdery lines till the whole pattern was a tracing of eerie flame. Nell saw that the powder itself was not burning? that the fires above it almost touched it.

Let her pass to de promised lan'!

The mamaloi was moving. Her black hands reached for the wooden bowl, closed around it. She moved along the table, lifted the bowl to the priest's thick lips, He drank the still warm blood of the sacrificed cock!

Papa Legba open de gate, the moaning chorus intoned, and the drums beat their savage rhythm.

Nell was crouched now, her eyes, widened and aching, glued to the two servitors of pagan rites. They were coming toward her, two black-faced grotesques blood-robed, pacing toward her in measured cadence with the measured beat of the drums.

And before them a shadow moved, a shadow that was not theirs!

The edge of that shadow touched the hem of Nell's dress, blackness ran up her clothing like quicksilver, swallowed her form, her arms. She was in the center of a sphere of blackness, blackness absolute, and her being shrank to a tiny pinpoint of white light within that blackness.

Fear was in that blackness, and horror, Crawling things were in it; things that slithered the steamy earth before the human race began. Terrors were in it, terrors of the jungle night when man hid in his caves and his hollowed tree-trunks and shuddered till daylight came again. All the primitive fears of mankind were in it, the fears of little Man in a cosmos he did not understand. And the beat of the drums thumped through it, promising relief, promising safety from all the fears, all the terrors that stalked the night. "Bow to Damballa," they boomed their message. "Bow to Ayida, the serpent goddess, and she will guard you from harm."

At last the little white light began to grow, and the blackness retreated before it. And Nell Carter was herself again.

But she was no longer chained to the stone wall of the haumfort, the underground temple of voodoo. She was in the open space before the altar, and the weird blue fire was burning all about her, tracing the design the papaloi had made. It was burning all about her but there was no heat in its flame. She was crouched in that open space, and crouched on its haunches before her was the white goat.

Its blue eyes gazed into hers, and her gray ones gazed back, and it seemed to Nell that a current flowed between them. It seemed that something from within her was flowing out along that current and something from within him was returning to take its place.

All the while the booming of the drums was like thunder in that narrow place, like thunder in the mountains, like the voice of an angry god growling his wrath.

And cry formed in Nell Carter's throat, the blatting cry of a goat!

SHE fought against it, fought against the animal cry

tearing at her voice-cords, fought to keep it from bleating

forth submission to the dark power of voodoo.

Steely light flashed between the goat and her, darting light, and Nell knew a knife hovered above her, a knife in the hands of the ebony papaloi, a knife that in another instant would flash across the goat's throat and hers, spilling their blood to the glory of the jungle gods. Goat-bleat quivered on her lips. Her chin lifted as the goat's head lifted, she and the goat offered their throats to the stroke. Exultation clamored in the girl's veins, exultation that she had been chosen for the sacrifice, that her blood would mingle with goat's blood for Dambella to drink, for Ouedda....

A hysterical voice screeched, somewhere: "Papa Legba! Papa Legba open de gate for me and not de white. Not de white, Papa Legba! Not de white!"

Nell's eyes flicked to the shock of the sound. A woman was hurtling across the space beyond which black rows watched, a girl whose hands clawed sleazy fabric from ivory breasts; breasts round and palpitant and hard-nippled. Nell saw her corded, stretched neck; her head, thrown back, strained back as Nell's own was strained; saw froth flying from her red-lipped, screaming mouth; saw eyes that were black flame.

"I am de goat widout horns," the girl shrilled. Wiry hair writhed like tiny snakes around: her frenzied face. Silk ripped—and the bounding Negress was a lithe, naked thing of the jungle, a wild, unhuman thing hurled toward the knife of sacrifice by a power outside itself. "I—I am de goat!"

Wrath, red wrath exploded in Nell at this blasphemy. She—she was the appointed one, the one the gods had honored! This—

"Not de white, Papa Legba. Not de white! I'm de goat!"

Wrath vanished as the crazed virago's words penetrated. She—she was Nell Carter! She was the white! White! Oh God! She remembered now.

The spell was broken. The white girl lifted from her crouch, lifted and screamed with white lips, "No! God help me! What am I doing? No!"

A growl behind her, a ferocious growl of baffled rage, twisted her around. Ti Nebo, his aboriginal visage contorted with fury, leaped for her, his thirsty blade sweeping in a long arc. Nell sprang to meet him. Her little hand clutched his knife-wrist, her other joined it, and she clung, swaying, to keep the cruel steel from her flesh.

He clawed her, ripped long weals in the skin of her cheek. The furrows seared like living flame. She shrieked in anguish—shrieked, but held her grip.

There were shouts behind her, the pound of running feet. The papaloi jerked, almost tore from her grasp, lifted her from the floor, but she held on. Frantically, desperately, she held to the grip on the skinny black wrist that the knife might not reach her.

The onrushing throng was almost upon her. She felt their hot breath, heard the thunder of their coming. In seconds now they would be upon her, would tear the profaner of their mysteries to bits.

They would kill her, but at least they would not have swayed her to their will.

A black form loomed at her side. A hoarse voice shouted. Fists lifted. This was the end!

But the fists crashed into the grimacing, terrible face of the sorcerer! His arm tore from her grasp, his wizened form sprawled across the altar, crashed with it to the floor. An arm swung around her waist, lifted her. The hoarse voice shouted in her ear, "Miss Carter, it's all right. It's all right, Miss Carter."

She twisted, saw the face of her rescuer. It was Rastus Brown!

SOMEONE plunged at them, and Brown's clenched hand

crashed into a swart face. Maelstrom of fighting. Voices

shrieked, "Kill her! Kill de white!" Other voices screamed,

"Let her through!"

Animal growls all about her. Snarls, and the howls of wounded men. Smack of fists on flesh. Black faces, brown faces, yellow faces, teeth bared, eyes rolling. Blood-lust in rolling white eyes. Maelstrom of fighting.

But in Nell's heart joy leaped. A carol of joy in her throat.

Some, at least, of her wards had remembered. Some, at least, were safe from the spell of voodoo. Her long lone fight had not been in vain!

"It's all right, Miss Carter. All right." Good voice, brave voice of Rastus Brown in her ears as they forged through the mêlée. Brave Rastus Brown, chocolate-faced, level-eyed, with gratitude in his soul for the white girl who had brought food to him and his when he was starving, clothed them when they were naked.

And others too, remembered. A phalanx was forming around her, a fighting triangle of fighting men, and they were moving faster now toward the door she could see far back in that cellar, a cellar that was no longer a haumfort but a basement beneath a Harlem flat.

Faster and faster they moved. They crashed the door, poured up the steps. They were in the vestibule. And suddenly there was silence.

A policeman was framed in the doorway, his nightstick gripped in his hand, his white face peering into the gloom. "What's goin' on here?" he roared. "What's all the yellin'?"

"Oh Lawdy," someone groaned in the crowd. "De cops! Now we—git it."

Nell jerked away from Rastus Brown's arm, pushed to the front. "Nothing, officer," she said lightly. "I'm late with my food tickets and the boys were all waiting down here in the hall for me. Were they making too much noise?"

"An' who're you?"

"Nell Carter, from the Home Relief." She was in the shadow; she hoped he could not see that she was hatless, her suit in rags. She hoped he could not see the livid weals on her cheek.

"From the Home Relief! Hell, Lady, you shouldn't be going around here at night."

"I have to bring their tickets to them, Officer. And besides, nobody would harm me here. The boys will look out for me. Won't you?"

"Yas'm," they chorused from the darkness around her. "Nobody ain't gwine hurt you w'ile we's aroun'."

The cop grinned in the light of the street-lamp. "I guess they wouldn't at that. They know which side their bread is buttered. Good-night."

"Good-night, Officer."

Nell watched the policeman stroll down the stoop, then she turned to the crowd. "Thank you, men. But why did you let me go through all that? Why didn't you get me out of there long ago?"

"We was scared o' the voodoo man," Brown's voice answered. "But when we saw as how he didn't have no power over you we wasn't ascared no more."

The smile vanished from Nell's tones. She was very grim. "He had no power over me because I didn't let him have, because I knew his tricks were all mummery and fraud. And if you believe that, if you hold on to that thought, he'll never have any more power over you. Remember that, will you?"

"Yes'm, we sho' will. He was a fakir, sho' 'nuff. We ain't gwine give him no moah uv ouah food tickuts. You-all needn't be scared o' that."

"All right. Now good-night."

"Good-night, Missie Carter. De good Lord bless you."

WEARILY Nell Carter descended the stoop into the street.

She had won. But a queer thought slid through her tired

brain. "Was he a fakir?" it asked. "What of the man dying

upstairs, because he was unwinding a string from a little

wooden doll made in the man's image? What was it that

overwhelmed you on the stairs? What was the shadow that

crawled over you and engulfed you so that all there was

left of you was a tiny, shining light no bigger than the

point of a pin?"

Music on Seventh Avenue was like the beat of jungle drums, serpent drums, booming....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.