RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

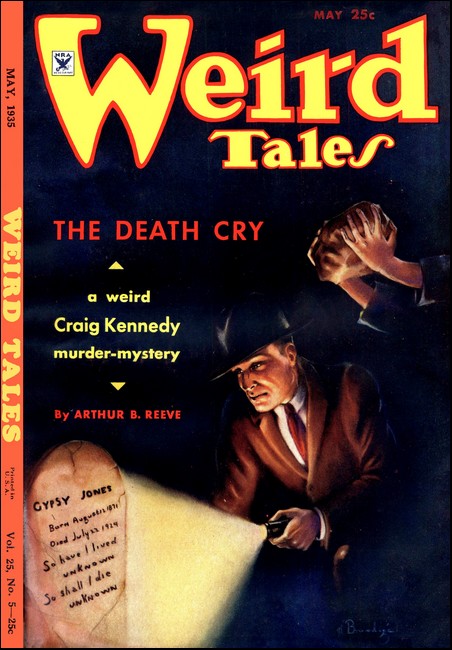

Weird Tales, May 1935, with "The Death Cry"

A sensational weird detective murder-mystery, featuring Craig Kennedy.

The name of Craig Kennedy is as well known to readers of detective fiction as is Sherlock Holmes. But never before have Kennedy's great deductive powers been employed in a murder mystery so weird and creepy as this unusual novelette. One after another, guests at the Three Pines Hotel are mysteriously murdered under circumstances suggesting vampirism; but the murders have a perfectly natural explanation. We challenge you to guess the solution of this baffling mystery before the author reveals it to you.

THE Three Pines Hotel stood high on the mountainside in the heart of the Catskills, a gaunt and rambling structure that loomed ghost-like and white in the night. Moonlight filtered weakly through the great pines that towered over it; and this moonlight—bluish haze in the night—gave the hotel a weird and forbidding aspect.

It was the third week of the summer season; yet from the hotel came no music or laughter, no animation or gayety such as in years past in summer seasons. The low structure with its several wings stood silent and grim in the night. Lights shone from a few of its windows, but the lights seemed lifeless; and over the great white rambling building a shroud of impenetrable silence seemed to hang. Encompassing this shroud of silence was the sense of some indefinable dread, stark and ominous and eery.

Craig Kennedy brought his roadster to an abrupt stop in front of the hotel.

The big wide veranda was lighted, but no one sat in any of the numerous chairs scattered over it. Lights came from the first-floor windows. On the second floor a window here and there was lighted, but most of them were dark.

Kennedy stepped out of his roadster and stood in the shadows of the trees along the road. For some time he remained immovable, his body tense and his eyes on the second-floor windows.

Suddenly he caught his breath. A window in the upper part of the building opened. It was the window of an unlighted room. The dull scraping of the frame going up broke the stillness of the night. In the moonlight Kennedy could see the white outline of the window as it went up slowly.

The long, dark form of a man—or was it a woman?—protruded far out the window. The hands went down to the ledge that ran along the front of the hotel beneath the second-floor windows. Someone walked out on the porch. The dark form darted back into the darkened room. The window thudded down.

Kennedy shrugged and walked across the road and up on the porch. The person who had come out on the porch was gone. Kennedy went directly into the lobby and up to the desk.

A tall, pale-faced man with the air and the voice and the clothes of a successful hotel clerk stood behind the desk.

"The manager of the hotel, Mr. Condon," said Kennedy. "I have an appointment with him."

The eyes of the clerk appraised Kennedy coldly. "You—you are Mr. Kennedy?"

Kennedy nodded.

"Ah—then, Mr. Kennedy, you may go right up into Mr. Condon's private office. He is waiting for you. First door, right."

Kennedy turned and started for the door to the right. He looked around the lobby. Everything about it bespoke luxury and comfort. A few people were sitting in chairs, staring silently at him. Their faces were set and drawn; they had little of the demeanor or ease of guests of an exclusive summer hotel.

KENNEDY opened the door to the manager's office. A young man,

not far past thirty, sat behind a desk. His face was frank and

pleasant-looking, though there were lines on it from worry and

lack of sleep.

"Kennedy!" he exclaimed as he got up quickly and rushed to meet him. "I'm glad you've come!"

Craig took his hand, smiled, then sat down on the desk.

"Yes, Condon, thanks! The head office of the hotel in the city asked me to get up here as quickly as I could. What's happened? Your place looks like a funeral parlor!"

"It will be a cemetery in another week if things don't change!" exclaimed Condon. "Did they tell you anything yet?"

"Only to get up here as quickly as I could and find out what was the trouble, cost what it might. No; they gave me no particular information. Said it would come better from you."

Condon sat down wearily.

"I guess maybe," he said, "it mightn't have got under my skin so much if it wasn't that this is my first year as manager. And it looks as if it will be my last."

"Oh, come now," broke in Kennedy. "There may be someone who wants this to be your last year."

Condon merely shook his head.

"I'll give you an idea of what has happened. The season opened with every prospect of a big summer. The hotel filled rapidly. Then on Thursday of the first week came the first intimation of what was to come. It was a trivial thing and I thought nothing of it at the time.

"Miss Worthington, an old maid, was awakened about three in the morning by the sound of someone in her room. Miss Worthington is very hysterical and she ran out in the hallway screaming, woke up all the other guests. We investigated but could find no evidence of anyone having been in her room. I put it down to a bad dream. But the following night George Branford, an old guest, complained that someone was in his room.

"Branford didn't make much of a scene, but he did tell the other people. Of course Miss Worthington talked about nothing but the man in her room. At first the guests took it as a joke. But when Branford told his story, people began to get puzzled. You know, Kennedy, how such things grow with the telling. In a few days Miss Worthington had been attacked—and Branford's life had been threatened, so it seemed.

"Well, five days passed and nothing happened. Then came that ungodly scream. I heard it. Everyone in the hotel heard it. I can't describe it. It was inhuman, terrifying. It lasted for a full minute. Coming as it did in the dead of night and waking everybody from sleep, it was nerve-racking in view of the nervous state of the guests already.

"This week, Kennedy, it came again! Philip Coulter, an old guest of the hotel, was awakened by someone moving in the dark. But when he turned on the lights he was the only person in the room. Yet on the bed-clothes there was blood! He felt his neck. There was blood there!

"Now, the strange part of all this. Coulter's door was locked and bolted from the inside. No key could have moved that night-bolt. His window was up only a few inches. There is a ledge along the front of the building. But this ledge is only a few inches wide, and round on the top. Only a bird could have walked this ledge. How that person entered Coulter's room is the greatest mystery of the whole thing."

Kennedy merely shrugged. It was obvious why they had said nothing at the city office. "I see. The scream and the attack on this man Coulter have driven away all your guests."

"All but eight," nodded Condon wearily. "Just eight left—and we are right in the middle of the season."

"You have checked up on all the guests?" suggested Kennedy. "You are sure none of them was behind these queer things?"

"We've checked every one and we've searched every inch of this hotel," Condon replied positively. "We have no idea where the scream comes from or who is behind it. Neither can we explain the blood on Coulter's bed-clothes. Frankly, we are completely stumped."

"Any queer guests?" queried Kennedy.

Condon smiled.

"You always have odd characters in a summer hotel. We have Madam Certi with us now."

"Madam Certi? Who is she?"

"A very fine old lady who talks with the dead. She claims to be a great spiritualist, but really is a very sweet and very fine old lady."

"I see," noted Kennedy dryly. "She is still here?"

"Yes; all the screams and other things have worried her very little."

"Any other peculiar guests?"

"Professor Mundo is a queer old character. Claims to be a great scientist."

"You have checked up on these two people?"

"In every detail, I'd say. They could have had nothing to do with the presence of someone in the different rooms or the screams."

"This scream," Kennedy remarked thoughtfully, "what do you make of it yourself? You're worldly-wise, Condon."

Condon actually shuddered. "It's the most ungodly thing, Kennedy, you ever heard! So damnably ungodly that if you once hear it, you'll never be able to forget it—or describe it."

Kennedy smiled and Condon flushed with resentment.

"You may laugh at me, Kennedy, but—" he checked himself. "I don't know what is behind all of it. But I am convinced an attempt was made to murder Coulter. How or by what means I don't know—unless someone was trying to choke him and he woke up."

Kennedy passed it by. "Let's get down to business, Condon. Where does this scream come from, in your opinion?"

"Why, it usually——"

CONDON never finished the sentence. From somewhere in the

depths of that great hotel came a wailing cry. It started low and

dismal; a chanting wail, weird and unearthly. Then it increased

in volume until it was a screeching, hideous scream, like neither

human being nor animal.

All color fled from Condon's face. He raised himself in his chair, trembling. "My God!" he cried hoarsely. "Talk of the devil—there it is now!"

Kennedy with a leap was out of his own chair and out in the deserted lobby. The unearthly scream was dying away slowly. It was coming from somewhere on the second floor, apparently. Kennedy was up the stairs, two steps at a time.

A man was running down the hallway. Kennedy recognized him as the pale-faced clerk down at the desk. His eyes were wild and his lower lip was twitching.

"God, man!" he cried. "It came from Mr. Coulter's room!"

An old man, small and wizened, dressed in the uniform of a hotel porter, joined them. He looked at the clerk and at Kennedy a bit stupidly, then started for Coulter's room on a dog-trot.

Kennedy and the clerk followed. At room 256 the old man tried the door. It was locked. He shouted. No answer. The clerk fumbled nervously for his passkey but couldn't find it. Kennedy shoved him aside and tried the door with his shoulder. It didn't give. He backed away and threw his body against it. It crashed—and he catapulted into the room with it.

When Kennedy got to his feet he looked around. His body stiffened and a whispered oath escaped his lips.

Lying face down on the floor, his neck covered with blood, was a gray-haired man. The bed-clothes were still wrapped around his pajama-clad body.

Kennedy turned the body over.

The face of the man was blue and distorted as if he had died in either great pain or great fear.

That moment Condon came rushing into the room.

"Anything happen?" he was crying breathlessly.

"This old man," returned Kennedy, taking his hand off the heart, "has been murdered!"

"Murdered?" repeated Condon, aghast. "Mr. Coulter!"

KENNEDY lost no time getting into action. He sent Condon and the clerk to check up on every person in the hotel. Then he sent the old servant, whose name was Peter, to get the keys to the two suites adjoining that of the murdered man.

Next Kennedy made a rapid but thorough examination of the murder suite. The bedroom where the body of Coulter lay on the floor, with the bed-clothes still wrapped about his legs just as he had either crawled or been pulled out of the bed, was the second room of the suite. The other was smaller, apparently a study. There was a desk in it, a large number of books, and a couple of easy-chairs.

Quick investigation showed nothing that interested Kennedy much except that the windows of the study were locked. He turned back into the bedroom and noted that the door he had crashed had a night-bolt on it, and that the bolt had been slipped closed evidently when he crashed the door in.

The windows to the bedroom were up, but one look out of the windows convinced Kennedy that it would have been a physical impossibility for anyone to walk along the ledge below them. The ledge was less than two inches wide, and the top of it was round. The transom to the hall was closed. Apparently, a careful examination of the window, the door and the floor gave no clue as to how the murderer had entered the room.

Then Kennedy turned his attention to the dead man. He brushed some of the blood away from the jugular vein. Under the blood near the base of the throat he saw something that made the lines of his face tighten. There were two little holes—no larger than a pin-point and about half an inch apart. They were black, and apparently the blood on the dead man's throat had come from them.

For some moments Kennedy studied these little holes. Then he stood up, his eyes still staring at the face of the murdered man. His own face was hard and tense; two little lines formed around his mouth.

He looked at the broken door, at the night bolt that had been slipped on, and the closed transom; he turned his face slowly and studied the open windows. His lower lip was sucked in between his teeth. Suddenly it came out with a subdued flop.

He turned and walked deliberately back into the study.

SEEING the telephone, Kennedy put in a call for the sheriff of

the county. It was some minutes before he got him.

"Sheriff," Kennedy shot out in sharp staccato, "this is Craig Kennedy, of New York City. There's been a murder up at the Three Pines Hotel. Bring a couple of men with you. We'll need them. And the coroner. If you can't get the coroner right away, bring a good doctor along. And I can use a good fingerprint man if you have one available."

He hung up and walked back into the bedroom.

Condon was standing in the door; old Peter was with him.

"Have—have you found anything, Kennedy?" asked Condon hoarsely. "I have all the guests rounded up in the lobby downstairs."

"I've just called the sheriff, Condon," replied Kennedy. "He'll be over at once."

Condon's youthful face wore a positively frightened look which suddenly turned to consternation.

"The sheriff?" he repeated. "Man, isn't it enough to have this happen without broadcasting——"

"Condon," retorted Kennedy sternly, "this is murder—hotel business or no hotel business. Have you the keys to the adjoining rooms?"

"I suppose you're right," muttered Condon. "Here they are."

Kennedy turned to old Peter, whose mouth was gaping with terror, his eyes riveted on the body on the floor.

"Stay at this door, Peter," ordered Kennedy. "Condon, you and I are going to have a look at these rooms."

Old Peter muttered a protest which Kennedy ignored as he turned to the adjoining suite to the right.

It was a small room and had been vacant a week. There was no connecting door to the Coulter suite.

Examination netted nothing. The window was down and locked. There were no indications that anyone had been in the room since it had been vacated.

"That other suite to the left," explained Condon as Kennedy turned to it, "is occupied by a young married couple, Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Pilcher. They took it the first week of the season and remained. They're downstairs. You can go in—on your own responsibility."

"I'll take it," decided Kennedy.

The Pilcher suite was laid out in similar manner to the Coulter suite, a bedroom and a second room, in their case a lounging-room, feminine in every detail.

Kennedy examined the furniture carefully, then went over to the window. It was wide open. This window was next to the bedroom where Coulter had been murdered. He looked back. The transom of the hall door was open.

"What do you know about this couple?" asked Kennedy.

"Nothing more than that they have been guests since we opened, and appear to be very pleasant young people. They seem to have plenty of money and to be well-connected in the city."

Kennedy nodded but said nothing. He walked into the lounging-room. Two glasses half-filled with liquor were on a table by a chaise-longue; a cigarette was still smoldering in an ash-tray.

"The Pilchers were up here when the murder was committed," Kennedy remarked. "Did they hear anything?"

"I talked to both of them," Condon replied. "The first thing they heard was the scream."

Kennedy walked back into the bedroom. Over by the door he picked up a small piece of black leather. He looked at it, then smiled.

"That's interesting," he muttered. "Come back to Coulter's room."

Condon looked at the piece of leather, his face a blank. Then he followed Kennedy out of the room.

Old Peter was still guarding the death room, his body atremble and his face colorless. Kennedy walked deliberately over to the head of the bed and pointed down at the floor.

"I left that piece of leather on the floor for a reason," he said. "I'm glad I did, now. If you will look closely, you will see that this piece in my hand corresponds to the piece on the floor."

Condon looked down. Lying near the bed was a piece of black leather about an inch wide and perhaps an inch and a half long. A piece had been torn from one end of it, and the leather in Kennedy's hand corresponded to the part torn off.

Condon shook his head wearily. "I don't understand it. The door was locked and bolted from the inside. No chance to get through the windows. How did the murderer get in?"

"That," said Kennedy, "is what I'm figuring out."

"Simply couldn't be done," Condon asserted, "unless the murderer flew through the window."

"Oh," Kennedy retorted, "just exercise your imagination."

Condon was about to reply, but he no more than framed his lips. The scream of a woman out in the hallway sent both Kennedy and himself in a rush to the door.

HER hair down and streaming behind her, her face distorted

with fear, a tail woman, very tall and very slim, arms

outstretched, was running wildly.

"Miss Worthington!" Condon cried. "What's happened?"

"Oh—oh—oh!" she wailed. "I saw it! I saw it!"

"Saw what?" demanded Kennedy. "I saw it! A great big black thing! It came after me. Oh!"

"Miss Worthington," Condon soothed, "if you have seen anything or know anything, calm yourself. You must tell Mr. Kennedy. He's a detective."

"A detective!" The words came from the old maid's mouth in an awed whisper. "All right—I will tell, if I must. I was coming down from my room as you ordered and I passed Madam Certi's door—and it was there! I saw it! A great big black creature moving down the hall! I screamed—and it disappeared. I just ran and kept on screaming—and here I am!"

"You are here, all right, Miss Worthington," said Kennedy. "But what was this great black creature? Man or woman?"

"Oh—oh—oh!" She started to wail again. "I didn't stop to look. It was big and it was moving fast. That's all I saw. I wasn't stopping to see anything else!"

Voices were coming from downstairs as of people entering the hotel, the sounds of heavy feet on the porch.

"The sheriff," Condon muttered, frowning. "If only we could have kept the authorities out of this!"

"Take Miss Worthington down with you," Kennedy ordered. "And Peter also. Tell the sheriff to send a man up at once to take charge of this room. I'll stay until he comes."

Condon, Miss Worthington and old Peter went downstairs and Kennedy went back to the room. He knelt down on the floor near the piece of leather. For some time he studied it; then he picked it up with his handkerchief, wrapped the linen around it carefully and put it in his pocket.

Again he knelt and studied the floor around the bed. He brushed back the nap of the rug in different spots. Finally he smiled grimly and got up.

A moment later two men entered. One was a short, heavy-set man, a deputy-sheriff. The other was tall, thin-faced and gray-haired; he had shell-blue eyes that gave him a soft, kindly look. He was carrying a small black leather bag.

"I am Doctor Greeley," the tall man announced to Kennedy. "Sheriff Blount asked me to help out on this case. The coroner is down at the other end of the county and can't be reached."

Nervously the other man added, "The sheriff sent me up to keep watch over the dead."

Kennedy's instructions were brief. He told the doctor to make as quick an examination of the dead man as possible in the hotel to determine the cause of death. He told the deputy to remain in the room and allow no one to enter.

Then Kennedy went downstairs.

SHERIFF BLOUNT was not the usually accepted type of country sheriff. He was young, an ex-service man, keen, alert and business-like. He wore a well-tailored suit and a soft gray hat.

Condon had given the sheriff the details of the murder by the time Kennedy got down.

"Doctor Greeley has told you why he is here, I suppose," Sheriff Blount greeted Kennedy cordially. "I have no fingerprint expert but I brought along powder and impression paper. I believe you must be an expert yourself, and I know the technique pretty well."

Kennedy smiled. Everything about this young sheriff pleased him. "That's all right. We can go over things and see what we find. There likely won't be any prints, but we might run into something."

"How was Coulter murdered really? Poison?"

"It looks very much that it was, Sheriff. Two little holes over the jugular vein indicate poison, and the face is blue. Doctor Greeley should be able to give a report soon."

Kennedy was looking at the lobby as he spoke. Huddled like sheep, with silent, drawn faces, the seven guests sat in chairs.

"I want you to see that no one leaves this hotel, Sheriff," he went on. "Naturally you are in charge of the case. I'll help you all I can in clearing up this mystery."

"You mean I'll help you." The sheriff was quick to appreciate Kennedy's tact.

Kennedy and the sheriff walked over to the guests in a half-circle in big easy-chairs. In the center sat Madam Certi, stout, gray-haired, almost queenly. Her round, fat little face with her small blue eyes looked kindly. Her eyes wandered from one guest to another in patronizing, motherly fashion.

Next to her, on her right, sat Professor Mundo, a little dried-up old man with a heavy head of iron-gray hair and a thin, twitching face. His gray eyes shifted rapidly from one to another. To her left sat George Branford, a typical New York broker, sleek, self-satisfied, with an outwardly frank, open face.

To the left of Branford were the Frederick Pilchers, the occupants of the suite next to the murdered man. Mrs. Pilcher was a girl somewhere in her late twenties, slim, graceful, with a cold, sharp face of the classical type rather than the frank open beauty of the outdoor girl. There was something in her, the movements of hands and head, that bespoke the stage.

Pilcher himself was small of body, and his face was weak. It was obvious he was largely under the influence of his wife.

At the left of Professor Mundo sat Burroughs Matthews, young and handsome and slightly bored by the whole proceedings. Next to him was Godfrey Nelson, a man somewhere in his fifties, with a full red face and heavy body. Money and success in business had left their mark on him.

Then at the right end of the half-circle, her hair still down and her face white, her lips still twitching, sat Miss Worthington. Her teeth were clicking and she kept her silence only by great effort.

Condon stood at the other end of the half-circle, and at his side was George McGuire, the pale-faced clerk. Old Peter paced back and forth behind them like a nervous animal in a cage.

"A murder has been committed in this hotel," began the sheriff quietly. "We shall have to ask each one of you to remain in the hotel until the investigation has been completed."

"I—I knew it was murder!" Miss Worthington let out a wail that might have been heard all over the hotel.

Burroughs Matthews smiled in his bored manner. Madam Certi gave a little gasp of fear. The others just stared in a helpless, grim manner.

"I knew some of us would be murdered!"

"The trains are still running," Matthews observed. "If you were so frightened, why didn't you leave?"

Miss Worthington promptly started to sob. Madam Certi gave Burroughs Matthews a reproving look.

"Mr. Kennedy will desire to question you," Blount went on.

"There will be no questions from me now," Kennedy cut in. "I want you all to go to your rooms and remain there. When I want any of you, I'll send for you."

"How long do we have to stay here?" Branford, the broker, rose. "I have to get back to New York tomorrow."

"Perhaps you may," returned the sheriff. "We'll see."

"I—I am willing to co-operate." Godfrey Nelson got up slowly, stammering. "But one man has been killed. Can we be safe if we go back to our rooms?"

"Well, you may remain in the lobby if you wish," Kennedy conceded. "One or the other."

"I won't go to my room alone!" wailed Miss Worthington. "Someone tried to kill me two weeks ago. I won't go alone!"

Matthews laughed. "Then take some brave man with you."

"A man—in my room!" Miss Worthington blushed very red and walked to the other end of the lobby and sat down.

Branford and Nelson started up the stairs slowly. Madam Certi rose, her fat little body wobbling.

"Ah, Mr. Kennedy," she gushed. "I have heard a great deal of you as a detective. I am so glad to be here in this crisis and to be able to help. You know I do many things not understood by the human mind. I know I can work with you."

"I have heard of you, Madam Certi," Kennedy replied quietly. "I am sure we will be able to work together."

The coldness of his tone was not lost on Madam Certi. For a fleeting second the sweet, kindly look on her face became a dark, animal-like scowl that passed as quickly as it came. She smiled sweetly and wobbled away.

Professor Mundo followed, walking with short, nervous strides. His eyes were on the floor, his thin face twisted.

Burroughs Matthews remained seated. "If there is any excitement to break the tedium, I hope you'll let us in on it, Kennedy."

"I shall. You may be sure of that."

Kennedy turned to Condon. "What became of old Peter as our backs were turned?"

"Why—he has disappeared." Condon looked helplessly about. "A queer old duck. Comes and goes like a ghost."

"Never mind, now," Kennedy bustled. "The sheriff and I are going to the cellar. Show us the cellar stairs."

"The cellar!" Condon gasped. "There—there isn't anything down there—I am sure."

"And I," Kennedy insisted coldly, "am sure there is!"

SLOWLY and carefully Kennedy and Sheriff Blount went down the stairs that led to the cellar. A worn electric bulb did not exactly flood the cellar with light. At the foot of the steps was a furnace on a clean cement floor. But beyond this under the different wings of the building the shadowy, yawning mouths of passageways loomed dark and sinister.

They had proceeded scarcely as far as the heater when Kennedy's body suddenly stiffened. Somewhere in the jet blackness of one of those shadowy passageways something was moving. There was the almost inaudible sound of feet.

Kennedy's automatic was out in an instant as he strode toward the shadowy part of the cellar.

"Go to the other side of the furnace and the coal bins, Blount!" he muttered. "And keep your eye peeled."

There was a swish of air. Something cracked the weak light bulb and plunged the whole cellar into deep darkness. A body was moving in that shadow. Another swish—and a guttural groan from Blount as he went down.

The same instant Kennedy's automatic blazed orange-red. He lunged forward, fairly diving into the dangerous darkness as with his other hand he whipped out his flashlight and sent a long streak of white light along the floor and walls.

The wavering streak of the flash revealed nothing, and he turned it back on Blount staggering to his feet, a thickening red trickle spreading down his forehead.

Whoever it was, whatever it was, had disappeared in the second before Craig could flash his light.

"What—hit—me?" gasped Blount.

"The person who missed me in the dark—just as I must have missed him in the dark, also," returned Kennedy.

"Person?" Blount tried weakly to laugh it off. "That was no person. It was a monster of some kind as near as I could make it out. Then something hit me."

Kennedy shook his head. "It was a very human person," he insisted, "a person who knows this cellar well and can move with the speed of a greyhound."

Craig was helping Blount to rise. "How are you?"

"All right—just groggy."

"Got to get you upstairs to Doctor Greeley right away." Kennedy advanced nevertheless, flashing his light on the walls.

The rock walls looked just as they had been left after the cellar was blasted. No cement had been put on them and no attempt had been made to smooth them over. Jagged rocks stuck out of the wall. Cracks appeared here and there.

"Come," Kennedy decided, "I've got to get you up to the doctor, pronto. Hulloa!"

His flashlight was playing on the floor where there was a thin covering of dust and dirt. Over at that end outlines of Kennedy's and Blount's footprints were visible. What Kennedy was looking at was another strange outline in the dust.

It was a round outline, more or less irregular. These outlines of strange-looking footprints came from a passage under the north wing. There were none on the smooth cement floor. But they went in on the other side, up the service stairs in the back—and were lost.

"Whoever made those prints disappeared quickly up those stairs," concluded Kennedy, "didn't stop or turn back. He just came, smashed the light, cracked your head and went! Come on, Sheriff, I must get you up to the doctor. This cellar will bear exploring, later."

BY the time they got up to the Coulter suite through the now

deserted lobby, Doctor Greeley had completed his examination of

the body, now on the bed and covered by a sheet. The doctor was

just closing his medicine bag.

Doctor Greeley squinted his eyes and looked at the sheriff.

"What's happened to you, Blount?"

"A ghost cracked me on the head in the cellar—a great big ghost that can run like hell!"

"Well, you come right over here under this light and let me have a look at you. H'm. A nasty blow. But I'll give you something to relieve the pain and then I'll dress it for you."

"By the way, Doctor," Kennedy nodded toward the bed, "what's the verdict?"

"The man died by poison that was injected into his veins," replied the doctor, working rapidly over the sheriff. "By what means it was injected, I do not know. It entered the jugular vein through two little holes that might have been made by some form of hypo-needle—and might not. He died almost instantly when the poison coursed through the blood stream."

"There was a struggle," Kennedy reconstructed, "and in the struggle Coulter was pulled off the bed. What caused the blood on his neck?"

"A series of very fine scratches, Kennedy. Very mysterious, those scratches. You have to look very closely to see them now. I didn't get them myself at first."

"I see," Craig nodded. "Just how can you connect those scratches with the two holes on the neck?"

"That, Kennedy," Greeley avoided, "is a matter for you to puzzle out. I am a doctor, not a detective."

Kennedy held up his hand and listened. An instant later he was out in the hall, past the door, where he scowled because the deputy sheriff was not there. An instant later he was in the Pilcher suite, where he had heard someone entering.

Standing in the lounge-room by a little escritoire was Mrs. Pilcher, her face pale and her lips quivering. She stared at Kennedy helplessly. All the cold cockiness she had displayed down in the lobby was gone.

"You are looking for something, Mrs. Pilcher?" inquired Kennedy courteously. "It was hardly necessary for you to wait until the deputy sheriff had been enticed away, then sneak through the halls to get it."

"I came to get some night-clothes! I don't intend to sleep in this room tonight!" She was quick with the excuse.

"Night-clothes—in the escritoire?"

Her cold thin face flushed angrily. But in her eyes there was a helpless stare, and she was stammering.

"I am afraid, Mrs. Pilcher," said Kennedy, "that I have already on my first visit to your room found what you are searching for to conceal."

Her face paled. "What—what do you mean?" she gasped.

Kennedy merely smiled. "I think you know."

Staring, with mouth gaping open, she gave a little cry of fear, then rushed out the door and down the hall.

"There you are, Blount," pronounced the doctor. "By the way, an old man who looks like a servant came with a message for your deputy. He asked me to watch. I almost forgot about it."

"Get hold of your deputy, Sheriff. Tell him not to leave his post even if he's blasted from it!" muttered Craig.

Condon, breathing heavily as if he had been running, came up the hall. "Madam Certi wants to see you in her rooms at once, Kennedy. It's important, she says, very important."

MADAM CERTI'S suite was in the south wing, overlooking the great mountain that rose in the rear of the hotel. It consisted of two rooms: a bedroom and a front room larger than in most suites.

This front room was filled with strange-looking furniture which Madam at her own expense moved up at the beginning of the summer in a small van. Odd-shaped chairs that rose only a few inches from the floor, teak tables weirdly shaped, black curtains that hung from the ceiling putting the room at all times in dark and shadow. At one end was a dais, somewhat like a throne of an ancient queen. Black curtains from the ceiling almost hid the throne chair.

Madam Certi, clothed in a long, flowing white robe, her head covered by a veil-like hood, met Kennedy and the sheriff at the door.

"Ah, Mr. Kennedy," she crooned in a soft whisper. "You have come to Madam Certi and it is well. For I will make the dead speak and when they speak you will learn much."

"So, you got me here to show me a little spiritualism," he smiled. "I thought it was something important."

An angry scowl flitted over the round, fat face of Certi. "I will show you," she reproved, "how Mr. Coulter was killed, because I have talked with him and he will appear to you."

"Talking with spirits won't get us anywhere," growled Blount. "Even a scientist like Professor Mundo might——"

"Ah, Professor Mundo," Madam Certi interrupted softly. "You wish to see him? He is here right now."

One of the curtains moved. The small wizened form of Professor Mundo appeared. His face was pale and he was trembling.

The lights went out. From the dais came the voice of Certi. "You will now see Madam Certi call the dead to speak! You will now see how Madam Certi can help you, Craig Kennedy!"

Silence, eery and oppressive. The voice of Madam Certi came in a low droning. Her words were incoherent.

Blount started toward the door. Kennedy's arm shot out, stopping him.

"Wait a minute!" Craig whispered. "It may all have some meaning."

Madam Certi's voice grew higher and plainer.

"Speak, departed one, speak, for there are those here who would know of thy death."

An effusion of amber rays fell upon the white-cloaked figure of Madam Certi. Then the rays dimmed. It was some light effect no doubt rigged up by Professor Mundo.

"Speak, spirit of John Coulter, speak!"

"She's crazy as hell," Blount muttered in disgust. "She——"

He didn't finish the sentence. As the light faded from Madam's face and figure, another light appeared to her right, at first just a soft glow; then as it grew stronger the outlines of a white face appeared in the light.

Blount gave a gasp of surprise. It certainly did strongly resemble the face of John Coulter, the murdered man.

"You are with friends, Mr. Coulter," she droned. "You may speak and tell them what you told me."

Coulter's face was vivid and ghastly. The lips actually began to move, as the light shimmered over the face.

"I was murdered." The voice was hollow, metallic, like a voice from a radio-drama telephone. "I was murdered by a fiend who kills through means more hideous than those of the Dark Ages." The voice died away in a groan.

"Speak on!" urged Madam Certi. "There are those who would avenge thy murder."

The lips of the ghastly vision moved again.

"Study well the marks on my neck and you will see——"

Even the voice of the dead was interrupted. Somewhere through the hallway the low wail of the death scream, the scream that had followed Coulter's death, broke the air. It rose to a high pitch, a weird, unearthly scream of death. It rang through the hotel, increasing in volume until it was an inhuman, terrifying screech.

The face of John Coulter disappeared. The light went out.

Kennedy made a leap for the door of the suite.

"Stay here, Blount! Don't let them escape!" he cried.

The door was locked. Kennedy fumbled, found the light-switch and flooded the apartment with light. The Madam was gone from the throne. Blount poked the curtain. Mundo was not there, either.

Outside, somewhere on the second floor, the weird, death-like scream was dying into a pitiful moan. A woman was yelling hysterically. Footsteps of men in the hall could be heard.

KENNEDY crashed the lock with a succession of slugs from his

automatic. As he leaped into the hall he looked back. "The head's

a wax figure, made up—lips move on wires!" shouted Blount,

who had torn aside another curtain.

Kennedy could hear people talking excitedly somewhere in the south wing. He strode down, swerved at the first turn. McGuire, the pale-faced clerk, and Condon were before a door. Old Peter came around a corner and joined them.

"It's Branford's room!" Condon muttered huskily as Kennedy strode up quickly.

McGuire was turning the lock with his pass-key. The door opened. No night-bolt had been shot this time.

Kennedy pushed the clerk unceremoniously aside and took a step into the room. The lights were out. His hand fumbled for the light-switch, found it, snapped it on.

Lying on the floor, near the window, clad in pajamas, and with some bed-covers wound around his legs, was the body of George Branford. He lay partly on his side, his face toward them.

The face was blue and distorted, twisted out of shape, as if, like Coulter, Branford had died in some great pain or fear.

Kennedy walked over to the body and looked down at the neck. Blood was over it. He knelt down and brushed the blood away from the jugular vein. There, as in the case of Coulter, were two little black holes, no larger than a pinhead!

Kennedy got up. His face was set and hard. Lines played about his mouth. His eyes narrowed to slits.

Condon in the doorway was staring, terror-stricken, at Branford's body. McGuire, at his side, the color completely gone from his face, was fidgeting nervously. Old Peter had disappeared again.

"Whose is the next suite?" Kennedy waved his hand in the direction of the corner in the hall.

Condon wet his lips. "The Pilchers," he replied.

"You gave them a room next to Branford?"

"Yes. They requested it."

"And on the other side?"

"Empty."

Kennedy went to the window and looked out. It was the front of the hotel, still, although around a turn in the hall. He was about to say something as Sheriff Blount burst into the room.

"They're gone! They've disappeared!" Blount cried. "Not in their rooms—not anywhere in the hotel!"

"I'm not surprised," returned Kennedy quietly.

A woman suddenly flung open the door of her room far down the hall. Her hair was streaming and her teeth chattered, as her eyes were staring wild with fear.

It was Miss Worthington.

"Look! Look!" she cried in a crescendo. "It went through the lobby! Look—out the window!"

Kennedy turned to the window. The road that ran in front of the Three Pines was flooded with a soft moonlight that penetrated a bit through the trees that lined the road. A form, dark and moving with the swiftness of an animal, was disappearing into the trees.

Kennedy took one good look; then with a spring he was through the door of the room.

Miss Worthington, with the sight of the dead body of Branford lying on the floor, groaned and slumped into a swoon in the arms of Condon, who caught her.

"Check them all as far as you can, Sheriff," Kennedy called back over his shoulder as he ran. "Have them all in the lobby."

A matter of seconds and he was out and across the road in front of the hotel.

THE moonlight filtered through the great pines that covered the mountainside in fleeting, darting shafts of light. In places it cut through the trees with the brightness of day; in other places it failed to penetrate, and the darkness was jet-black and heavy.

Kennedy dashed through the trees. No sign of the form appeared. He came to a narrow path that wound in and out among the trees like a wriggling snake. He followed it.

It was taking him far down the mountain and out across a little plateau. Here and there the moon lighted his way; at other times he was plunging through a darkness so intense he could scarcely see the trees before him.

Blindly he followed the path. He had no idea whether the person he had seen disappear in the trees was in front of him or far to his right or left. He plunged on, his mind mystified at what he had seen from the window.

The person who had disappeared among the trees was no dark form or monster. Kennedy's one good look told him that. But what he had seen was even more puzzling than if it had been the dark form of some monster. The man who plunged into the pines was Burroughs Matthews!

Slowly in Kennedy's mind there had been forming a solution to the strange murders. But this solution was so weird, so terrifying that at first he had refused to give it credence. The sťance of Madam Certi had given him an inkling that it was true. And yet in this solution Burroughs Matthews had had no place. But now he was following the young man, who was rich and cultured and very much bored with life. Kennedy wondered vaguely where this chase was taking him.

Suddenly Kennedy stopped. He was in the darkness of the trees; but out in front of him was an open space, flooded brightly by the moonlight. An old stone fence was around the open space and the grass grew wild and high over the fence.

Inside the enclosure was a small mound. An old tombstone leaned grotesquely in the tall, wild grass.

Kneeling down by this tombstone was the slender, youthful form of Burroughs Matthews.

Kennedy remained in the darkness of the trees and watched. The young man was tugging at the tombstone. Then suddenly he stopped, took a piece of paper from his pocket and began writing on it. He made only a few notes. Then he jumped up suddenly, ran through the grass away from Kennedy, disappearing over the stone fence.

Had he heard something?

Kennedy did not follow him. For several minutes he remained standing in the shadow of the trees. Then he struck out into the open, leaped the stone fence and thrashed through the grass to the lone grave.

It was an old-fashioned round-topped tombstone with the grass swaying weirdly about it.

The inscription read:

GYPSY JONES

Born August 12, 1871

Died July 22, 1924

So have I lived unknown

So shall I die unknown

Kennedy studied the strange inscription. He took a pencil from his pocket and copied it in a notebook. He slipped the book back into his pocket and turned to retrace his steps.

Something was moving in the grass to his right. Instantly he went down flat on his stomach. He lay still, his body tense and ready for a spring. But only the silence of the night greeted him. The tall grass waved lazily in the soft breeze. A little to his right the old tombstone seemed to lean weirdly, loosened.

Somewhere in front of him he had seen the grass move. But now there was no sign of life there. Slowly he crawled forward on his stomach; it was difficult work in the grass. His automatic was ready but he wasn't firing blindly and giving the advantage of knowing where he was. He moved forward several yards flat on the ground.

Somewhere in front of him there came a harsh, inhuman laugh. Two cold hands with powerful fingers went around his throat. He felt fingernails tearing at his skin. He drew his legs under his body for one supreme lunge forward to throw off his strange attacker.

But he never got his legs under his body. From behind, what seemed in the darkness a form, huge and grotesque, loomed over him, poised in the air a second, then crashed down on his head, and he saw no more.

KENNEDY came to, later, with someone shaking his body

violently. He opened his eyes, but the pain in his head was too

great.

Someone was leaning over him. At first he could not recognize who it was. Then the outlines of a young and handsome face came to him. He blinked his eyes again. It was Burroughs Matthews!

"I came out for a quiet walk," said Matthews, "and I run right into excitement! Someone must have been trying hard to kill you, Kennedy. You have me to thank that they didn't."

"I don't know," Kennedy muttered as he struggled to his feet, "whether I should thank you—or arrest you as a material witness."

"Neither is very important right now," returned Matthews.

"Why were you trying to remove that tombstone—and why did you stop?"

"Just curiosity," Matthews answered in a bored manner. "I heard someone coming. So I started away. When I heard a struggle I came running back. The tombstone was gone. You were lying on the ground and some baffling-looking person in the dark was going over the fence. That's all. Come, I'll get you back to the hotel."

AS Kennedy and Matthews walked into the lobby of the hotel the four remaining guests were seated in a circle at the far end. Sheriff Blount and Condon were with them.

Mr. and Mrs. Pilcher sat close together on a small couch, their eyes on the floor. Mrs. Pilcher had lost much of her brazen attitude. She did not look up as Kennedy placed Matthews next to her.

Godfrey Nelson, his full, red face drawn and haggard, sat directly across from them. Miss Worthington, hysterical and crying softly to herself, sat near Condon. She insisted on his holding her hand, which the young manager did with a scowl.

"Burroughs Matthews is not to leave this hotel, Sheriff," indicated Kennedy. "Have one of your men with him all the time. I have something important to discuss with you and Condon now."

The Pilchers looked up at Matthews, surprised and puzzled. Godfrey Nelson stared at the young man. Even Miss Worthington stopped crying to look at him.

Matthews smiled and nonchalantly lighted a cigarette.

"Sweet man, you are," Matthews laughed dryly. "I save your life—and then you virtually place me under arrest!"

Kennedy said nothing. He turned and walked into Condon's private office with the young manager. Blount motioned to one of his men, whispered his orders, and followed them closely.

In the office Kennedy shut the door himself, then turned to the other two. "I want all the information you have about one Gypsy Jones buried down there on the plateau."

Condon looked blank at him. Sheriff Blount was puzzled.

"Gypsy Jones?" the sheriff repeated. "You mean that fellow who lived like a hermit on this mountain when the hotel was being built?"

"I imagine so," Kennedy encouraged. "There was a tombstone down there with his name on it, his dates and a queer inscription underneath. I followed Burroughs Matthews down there after the murder of Branford. Someone knocked me unconscious. When I came to, Matthews was there—the tombstone was missing."

"Missing!" Blount repeated, then wrinkled his forehead. "I don't remember a great deal about Gypsy Jones. I was pretty young when he died. But as a boy I can remember the strange old man who lived on this mountain like a hermit."

"Oh, I've heard of him," Condon put in. "Yes; he died the year the hotel was opened. I have heard of this Gypsy Jones. Why, Godfrey Nelson was a guest of the hotel the year that Gypsy Jones died. He was supposed to have known him."

"Did Coulter know this Gypsy Jones?"

Condon wet his lips and nodded. "Yes," he said at length. "Coulter knew him, I believe. So did Branford. Coulter, Branford and Nelson are our oldest guests. They've spent every summer here since the place opened."

"Get Godfrey Nelson in here," Kennedy ordered.

A FEW minutes later Nelson entered the room, his round, red

face a bit pale and his eyes roving anxiously.

"Tell us all you know about Gypsy Jones, Nelson," Kennedy demanded briskly. "All."

"Gypsy Jones?" Nelson repeated. He was sparring for time. His eyes met Kennedy's. "Why—why," he decided to surrender, "it was ten years ago he died. Yes, I knew him. A strange character. In fact, I was present at his death. People around here considered him insane. He lived in an old shack that has since been torn down. He was buried near the shack."

"Coulter and Branford knew him," prompted Kennedy.

"Why—yes; they knew him as I did."

"You were guests," prompted Kennedy again, "the first year."

"Yes, we three often tramped over the mountains. I think it was Branford who first ran across Gypsy Jones. Jones was an old man with a fine, intellectual face. We were convinced Gypsy Jones was not his real name, that he was a man of breeding and culture—perhaps a man with a past he was trying to forget."

"Did you learn his real name?" demanded Kennedy.

Nelson hesitated, then decided it was best to tell. "Yes—his real name was Sir Charles Wainwright. He was an Englishman."

"An Englishman? Why was he buried as Gypsy Jones—and on that lonely spot?"

Godfrey Nelson shook his head. "It was his last wish," he replied earnestly. "Coulter and I were with him just before he died. He was delirious and it was then that we heard his real name. But before he died he was himself again. He asked us if he had talked. We told him he had. Then he made us solemnly promise that he would be buried as Gypsy Jones and that his name would for ever remain a secret with us."

The breaking of a confidence to a dying man seemed to worry Nelson.

"When a man is dying," he went on, on the defensive, "a person respects his wishes. So he was buried there as he wished. Why, he dictated the inscription for his tombstone. The three of us respected the oath. I am talking now only because the law is forcing me to talk. What mystery was behind this poor man's life, I don't know. What that may have to do with these terrible murders, I can't conceive."

"It has very much to do," asserted Kennedy. "Coulter, Branford and you are, or should be, the only persons who knew the real identity of this man. And now someone is very anxious, for some reason, to see each of you die before you can tell."

Nelson paled and bit his lip. "You mean," he said weakly, "I am to die, also?"

"You," asserted Kennedy grimly, "are scheduled to die next. But if you do as I instruct, you have nothing to fear."

Nelson's lips twitched. His face was imploring.

"You," Kennedy instructed, "are to remain in this hotel. But you are not to go to your room alone, or any other room, under any circumstances. You are to remain down here in the lobby and Sheriff Blount will assign one of his best men to remain with you. If you fall asleep, there will be someone awake near you. You may go back into the lobby now."

Godfrey Nelson got up slowly and walked out of the room.

"But, Kennedy," the sheriff remonstrated, "how could a man like Gypsy Jones be connected in any way with these murders? He died ten years ago. He was half crazy and——"

"Three men knew who he was; two of these men are dead." Kennedy was positive. "If we're not careful the third will die."

"Yes, but that death scream——"

"I have a theory about that; it may seem fantastic and weird just now. Those two pieces of leather gave me my first hunch. I think it is going to take us back down into the cellar."

"Let's go, then, and get it over." The sheriff rubbed his sore head ruefully.

Kennedy shook his head. "I am not ready yet. First I must check up on some facts that have aroused my suspicions. To do that I must go to New York immediately."

KENNEDY'S roadster cut through the night with the speedometer registering better than seventy much of the time. He slumped in the seat wearily, his face set. For the first time since the attack near the lone grave he realized the strain.

Intermittently far behind him came the subdued roar of a powerful car.

He crossed the Hudson by the Peekskill Bridge. On this wide road he was shooting the gas to his motor. The illuminated dial of his wrist-watch gave two-thirty as the time when he hit the Bronx River Parkway.

Still, now and then, that subdued roar of a powerful car.

It was ten minutes to four when he pulled up before the granite, pillared and domed building on Center Street which was Police Headquarters.

He was there probably not more than twenty minutes, making requests for information in the morning, telephoning and checking up on an address he had taken from the register at the Three Pines.

He examined the automatic in his left coat-pocket, checked the ammunition in the clip, then did the same with the automatic in his shoulder-holster.

His plan of campaign set, Kennedy nodded to the officer at the main entrance, ran down the steps, and shot his roadster slithering uptown on the East Side, with little to hinder him but a few cruising night-hawk taxis.

Eyes on the mirror, he finally satisfied himself that he was not being followed. Only then did he turn, shoot across town to Second Avenue, finally pulling up at a corner in the upper forties.

No sign of life moving on the street. Across, an apartment house loomed. It was not a new building. There was, however, an air of exclusiveness about it, a look that set it apart from the cheaper tenements surrounding it.

For some time Kennedy studied the building. There was just one light from a window on the fifth floor. Perhaps someone had forgotten to switch off the light. Otherwise it was dark.

Finally, Kennedy crossed the street. A colored boy was dozing in a chair by the elevator.

Kennedy twirled a five-dollar bill in his hands. "Apartment 513," he said peremptorily, stepping into the car.

The colored boy was wide awake now. He looked greedily at the five-dollar note, then uncertainly at Kennedy. Casually Kennedy slipped his hand from his left coat pocket and turned up the left lapel of his coat. A shield which he wore by courtesy of the police commissioner, gleamed.

The colored boy swallowed hard, took the bill, shot the car upward to the fifth floor.

"Don't bang the door, Rastus," Kennedy admonished as the boy hesitated. "Shoot down—but keep awake, if I should ring."

"Yas, suh!" The boy was still pop-eyed over the shield.

The moment the elevator was gone, Kennedy, noting that 506 was before him, turned and walked quietly until he stopped before a door numbered 513.

He pressed the buzzer. There was no answer. He pressed again and listened again. Only the deep impressive silence of night.

He tried the door. It was locked, of course. With a quick look up and down the hall, he took a piece of steel from his pocket. It was only a matter of minutes before he sprung the lock, and the door opened.

A wall of darkness greeted him. With his hand on the automatic in his holster, Kennedy felt his way down a long narrow corridor. This was the Pullman type of apartment.

At the end he came out on a large room facing the street. Enough light feebly filtered in from the street to give a shadowy outline of the furniture.

Kennedy stood, his body rigid, right hand still gripping the automatic. His ears strained, but only an eery silence greeted him.

Then he walked over to the wall, felt along it until he came to the light-switch, turned it, and the room was flooded with light. A moment he stood, his body tense and ready for action, eyes and ears alert for any sound or movement.

It was the living-room of the apartment. From all indications it had not been used for some time. A coat of city dust covered tables, chairs and bookcases.

He went over to a bookcase, and glanced cursorily at the books. Suddenly his attention was drawn to a book out of the top of which stuck several pieces of paper. He removed it from the bookcase. The slips of paper showed that someone had the habit of marking places in the book in this manner. He opened to the marked places rapidly. Then he found another and still another book similarly marked.

All the markers were at descriptions of poisons!

Kennedy piled the books up on a chair and turned to the apartment for further investigation.

He turned into a room off the living-room, a small study, with a desk at the window also opening on the street. A letter-file on the desk was open, drawers were pulled out, papers, letters, documents were scattered about.

Someone had been there before him! He thought of the roar of the high-powered motor behind him on the road. He reached up to feel the electric light bulb. It was still hot. Someone had been there only minutes ago!

His left hand still on the bulb overhead and his right on the gun in his shoulder holster, a body came hurtling at him through the semi-darkness of the room.

He had turned and drawn with the speed of lightning. But the suddenness of the attack sent his shot wild as he felt thin arms encircling him with the insane power of a maniac. The impetus of the attack knocked the automatic from his hand. He might have reached for the other in his coat pocket, but he needed both arms to fight off the maniacal clutch of those wiry arms.

Together they went to the floor. Silently, grimly they struggled, each trying for a strangle hold. The body under Kennedy was slippery and quick as a cat. Kennedy's hands went to the person's neck. Once he had it he might either reach the gun on the floor with his right hand or the gun in his pocket with the left.

He had it! The gun on the floor was only six inches away. The body slipped out from under him with an incredible eeliness. His right hand had the gun—but his left was only gripping the floor.

He threw his body backward and made a dive in the darkness for the legs that must be there. The lunge through the dark for his unknown assailant was futile. There came a bang—and out in the hallway a dry, inhuman laugh. No other sound.

Kennedy was on his feet, his body against the door. It was the door that had banged shut. It did not give. His flashlight had been smashed in the scuffle. He felt along the wall for the switch, turned it, and flooded the little room with light. A closet door was open.

He smiled a cold, bitter smile as he saw the desk and floor covered with papers, scattered in every direction. That must have been the fifth-floor light he had seen. The intruder had been working as he entered, must have retreated into the closet, and catapulted himself out the instant Kennedy's back was turned.

As Kennedy wrenched at the closed door he realized there was a snap-lock on the other side. The outside apartment door banged. Should he shoot the lock and pursue?

His eye lighted on a burned piece of paper, a letterhead torn across the top. Gun in hand, he picked it up.

Engraved in old English across the top were the words:

SIR CHARLES WAINWRIGHT

42 Haversham Road

Whitehall

London,

England

The typed part had been burned in the little fireplace, along with other charred paper.

He turned to the lock, shot it open, and dashed down the hall, both guns in his hands. In the hall he thought for a moment. The assailant had just enough start to enable him to make a getaway down the fire-stairs.

He turned back and dashed to the front windows. The first rays of dawn were breaking. Down on the street he could make out a tall, thin form scurrying from the street door.

A cold, satisfied smile played over Kennedy's face. The form he had seen scurrying out and around the corner was none other than McGuire, the tall, pale-faced clerk at Three Pines!

He felt for the paper in his pocket, picked up the books on the chair, switched out the lights, and went out leisurely.

IT was forenoon when Kennedy got out of bed at his apartment on Riverside Drive.

His man, Parker, had three telegrams and notations of two telephone calls that had come in that morning.

Kennedy scanned the telegrams casually and stuffed them into his pocket. Then he called back twice on the telephone. Already, breakfast, still steaming, had arrived from the restaurant downstairs.

He was eating leisurely and Parker was busying himself about the diggings, when suddenly Parker stopped short.

"Oh, by the way, sir, begging your pardon, sir," Parker interjected apologetically, "Police Headquarters telephoned while you were in the bath and asked that you be informed they have arrested Madam Certi and a Professor Mundo and are having them held, sir. I made no notation and I forgot to tell you, sir."

Kennedy frowned.

"Stupid!" he exclaimed. "Headquarters is the last place I want Madam Certi and Professor Mundo held."

"And, sir, they said, I believe, that they arrested them at Madam Certi's apartment. I understood them to say they made the arrest at five this morning when Madam Certi and the professor entered the apartment."

"Hand me the telephone, Parker—I must have them released at once—no, it can wait. I shall be at headquarters several hours before I am able to drive back to Three Pines. You'll probably see me in the early morning hours, Parker. Tell people I am out of town, that's all. Use your discretion."

"Thank you, sir. Good-bye, sir," Parker bowed as Kennedy strode out to his roadster which had already been sent around from the garage, washed, greased, oiled and generally tuned up.

IT was about four when Kennedy swung into his roadster down at

Center Street and started back to the Three Pines Hotel in the

Catskill Mountains. When finally he left the city behind he kept

his car at an easy speed and appeared in no great hurry to get

back to the hotel.

His face no longer wore a puzzled look. In the rumble of the car were piled the books with their telltale slips of paper as markers. He had various strips of leather. And in his breast pocket was a voluminous sheaf of telegrams and radiograms.

Shortly past seven he parked his roadster in front of the Three Pines. Sheriff Blount was waiting on the veranda.

Ignoring the locked rumble seat and its precious evidence, Kennedy locked the car as the sheriff came down the steps.

"Madam Certi and Professor Mundo came back an hour ago," the sheriff announced, modulating his voice. "Someone drove them back from New York and they have gone directly to Madam Certi's room and have locked themselves in. Something queer is going on in there. Strange noises are coming from the room."

"Anything happen since I left?" Kennedy inquired.

"Happen? Plenty! Mrs. Pilcher tried to commit suicide. That's just one of the many things that have happened."

"Tried to commit suicide?" Kennedy repeated quickly.

"I don't understand it," Blount returned. "But, then, there isn't anything I do understand about this whole damned case. Yes; Mr. Pilcher came running wildly down the stairs about noon, shouting that his wife had taken poison. I got Doc Greeley up here and sure as hell she had taken some poison. The Doc was able to bring her around after pumping out her stomach. She's upstairs now and won't speak to anyone. Her husband's been acting queer ever since."

"What else happened?" Kennedy asked keenly.

"About everything you could think of," Blount answered wearily. "Old Peter came back and then disappeared again. And then that damned scream! It came again—right after Madam Certi and Professor Mundo came back and locked themselves in the room."

"The scream!" Kennedy exclaimed. "Who's been killed?"

"Nobody was killed. But the scream sent the old maid, Miss Worthington, into hysterics. Doc Greeley took her home with him. I hope Mrs. Greeley gets her quiet. She used to be a nurse, you know. I know what I'd do with her if I had my way—solitary and straitjacket!"

"Quite scientific, quite scientific," Kennedy ignored. "What about Godfrey Nelson? You gave my heart a jump when you mentioned that scream."

"Oh, Nelson has hardly stirred from his chair in the lobby. Just sits there like a man who is about to be electrocuted."

Kennedy by this time was walking into the lobby, Blount following, shoulders sagging a bit and face tired.

Godfrey Nelson was the only person except his guard in the lobby at the moment. He was sitting in a large easy-chair, his hands gripping the arms of the chair and his eyes staring first one way, then another.

"And my friend, McGuire, the clerk?" Kennedy asked, seeing no one behind the desk. "Has he come back yet?"

"Come back?" Blount exclaimed. "Where did he go?"

"On a rather long trip," Kennedy avoided dryly. "Is he in the hotel now?"

"I saw him a few minutes ago. Up in his room, I guess. He's not on duty at this hour."

"I see."

BURROUGHS MATTHEWS was walking down the stairs at the moment

with his usual bored nonchalance.

"Ah, there you are, Kennedy!" he greeted. "I say, Mrs. Pilcher has been asking for you. She wants very much to talk to you, refuses to talk to Sheriff Blount. It seems her conscience is troubling her. So, you see, Kennedy, I haven't run away yet—and we haven't found the tombstone either."

"When the time comes, Matthews," Kennedy retorted, "that block of brownstone may upset somebody as if it were thrown at them. Come on, Sheriff; we'll both go up and See what Mrs. Pilcher has to say."

Matthews shrugged and walked over to Nelson and sat down beside him. Kennedy and Blount ascended the wide stair.

Mrs. Pilcher was in bed. Her face wore a death-like pallor and her eyes were wild and glassy. Her husband sat near the bed. His thin face was turned to her and his eyes seemed to bore like gimlets. He looked up at Kennedy and Blount as they entered. But there was nothing friendly about his look.

Kennedy went over by the bed and stood by her.

"There is something—something I must tell you, Mr. Kennedy," she murmured. Her voice was weak and had a far-away note in it as she opened her eyes, then closed them again. "I wanted to die—so I wouldn't have to tell it—but they wouldn't let me—and now I have to tell...."

Her voice died away in a feeble moan. She looked at her husband. His eyes were flashing fire and hatred.

She shook her head as if to gather her thoughts. "Fred," she said to her husband, "we—I must tell!"

He rose stiffly, his' thin lips pressed tightly.

"Ethel!" His voice cut the air like a sharp knife.

She raised her head and body a little, gave a frightened scream, then fell back on the bed in a swoon.

Her husband turned to Kennedy and Blount. "I am sorry, gentlemen," he said in a smooth, oily voice, "but Mrs. Pilcher is still delirious. She doesn't know what she is doing."

Kennedy shot a withering look at Pilcher.

"Mrs. Pilcher doesn't need a doctor," he said curtly. "Mrs. Pilcher needs a friend right now!" He massaged her temples.

Kennedy turned as her eyelids fluttered, and walked out of the room. Blount hesitated, looked at the pale face of the woman, her breathing so low it could just be distinguished, then followed quickly.

"What do you make of it?" He jerked his head backward.

"She'll never talk as long as that husband is around, and we can't very well see her now without his being in the room."

From far up the hall came a low moan, a moan as of pain.

"Madam Certi!" Blount muttered with a scowl. "That's been going on ever since she came back."

The moaning suddenly ceased. Someone was talking in a low, chanting voice. The voice stopped and the moan resumed.

"Talking with the dead!" Kennedy exclaimed. "It won't get us anywhere to disturb her now."

He looked at his wrist-watch. "First we're going out to the car. You're going to help me carry some stuff into Condon's office where I can lock it up. Then I'll take you down-cellar and solve the weird part of these murders!"

CONDON'S private office was empty when Kennedy and Blount entered, their arms full, from the car.

"Condon is up in his room," Blount explained. "He went up just before you came back. He is fagged out."

"Just as well." Kennedy closed the door and locked it on the inside. "We have the office to ourselves. I can explain certain things that I want to tell you."

Kennedy laid the books on the desk and took the sheaf of telegrams and radiograms from his pocket.

"I found out, Blount," he began, "that Gypsy Jones who lies buried out there is going to figure as the key to this case."

Kennedy selected one radiogram in particular.

"I found out, for one thing," he went on, "that the Wainwright estate in England is a very large one. The last heir died in London. The money is now looking for someone to go to."

"The Wainwright estate?" Blount inquired, puzzled.

"Yes. It seems that Sir Charles Wainwright, the chap buried out there as Gypsy Jones, left his ancestral home when he was a young man. He had some trouble with his family over his escapades and changed his name. His estrangement and all preyed on his mind—finally drove him to lead the life of a hermit up in these mountains."

Kennedy paused. Blount was all ears.

"But," Kennedy added impressively, "before he started to lead that life, he had married under the name of Jones in New York. To this marriage was born a son. That son is now living in New York. Under the law this son would inherit the entire Wainwright estate if he could establish the fact that his father, this Gypsy Jones, was Sir Charles Wainwright. That son has no suspicion, even, who his father really was!"

The sheriff framed his lips for a low whistle.

"There is, however, a certain other collateral heir to this vast estate who, if the identity of Gypsy Jones is never known, will inherit the fortune. Thus you have the reason why someone is frantically busy to murder the three men who could swear that Gypsy Jones was really Sir Charles Wainwright. This person happens to be right in this hotel!"

Kennedy spread out the telegrams before Blount.

"The whole story can be found in these telegrams and radiograms. I had Police Headquarters wireless Scotland Yard for the complete information. They got a prompt answer. Those books I took out of an apartment of the person who has murdered two people and hopes to murder the third."

Blount fumbled the messages nervously.

"Yes," Kennedy repeated, "the moment Godfrey Nelson leaves that chair and goes upstairs, he will be a dead man!"

"Phew!" Blount was reading the messages, trying to digest them. "Then you know what that scream is?"

"We'll find out about that weird part of it all in the cellar," Kennedy nodded. "I've had a hunch all along what it was. But it wasn't until I read a couple of volumes in the Police Academy up the street from headquarters that I was convinced."

Impatiently Kennedy slipped the books and other stuff into the safe, shoved the telegrams in his pocket, unlocked the door and then locked it again.

"Better have your automatic ready, Sheriff," he said ominously as they approached the cellar stairs; "you might have to use it down here any moment. Be prepared for some fast work!"

"O.K., Kennedy!" said the sheriff, grimly following as Kennedy opened the door.

THE cellar under the north wing of the hotel was brightly

lighted now with a hundred-power lamp. Sheriff Blount had put it

down there during the day.

The stone walls of the cellar, left exactly as they had been blasted out of the side of the mountains, loomed ruggedly in the brilliant light, a wall of jagged rocks. Here and there large cracks appeared in the rock, and at several different places dampness seeped through.

The dusty floor of the cellar was covered with footprints this time, none now distinguishable from the others in the mass. Old pieces of broken furniture strewed the floor, and boxes with an accumulation of dust were piled against the wall.

Kennedy moved swiftly along the east wall of the cellar, his face tense, his automatic in his right hand.

Blount followed, a look of bewilderment on his face as Kennedy gave up trying to study the footprints and started tapping the wall with an old stick. The taps echoed sharp and clear through the cellar.

Suddenly he stopped. He stepped back and surveyed the wall. On his face was a puzzled look.

"It's there," he said, "somewhere in that wall!"

Blount looked at him. "What's there?" he demanded.

Kennedy said nothing. He just surveyed the cellar wall. To the right in the direction of the main cellar old boxes were piled against the wall. To the left the jagged rocks extended to another cross-corridor of the cellar about twenty feet.

"Hidden very well;" he muttered to himself. "Better than I had expected."

Blount now merely looked. Kennedy picked up a rock to tap the wall. Then he got down on his knees and started tapping the wall from the bottom.

He stopped. The clear sharp taps on the rock had a hollow sound. He got up and tapped the wall clear to the top.

"It's here all right!" he cried. "Give me a hand, Blount."

Blount started toward the wall to do so, then stopped suddenly. His body froze in his tracks, his face lost all color. Even Kennedy paled a bit and took an involuntary step backward.

From somewhere beyond that jagged wall of rock there came the wailing unearthly scream, the scream that had followed the murders of both Coulter and Branford.

At first it was low and indistinct and far away; then it increased in volume, a screeching, blood-freezing scream, inhuman, piercing, weird enough to set on edge with terror the nerves of the most intrepid human being. Then it died away into a mournful, sad moan; died away, it seemed, into the very bowels of the earth.

For seconds after it ceased, a deep, oppressive silence hung over the cellar. Blount stared at the wall, his eyes wild and his face a death-like gray. Kennedy wet his lips and in spite of himself gave a quick, nervous laugh.

"We've found it, all right," he said slowly. "Now we'll have to find out how to get on the other side of this wall."

"Good God, man," groaned Blount, "you're not going there?"

"As soon as I can find a way," returned Kennedy.

He was tearing at the jagged rocks. He loosed a rock and then some dirt. He paused. That did not seem very practical. A moment and he began moving some large but comparatively light wooden crates piled up alongside the wall. Back of them was a huge piece of slate-rock. He pried at it with a stick, and the slate swung outward on hinges. A dark, yawning opening was revealed that led to a cave-like room back of the rock wall.

"Be ready for anything, Blount!" Kennedy cautioned. "This thing was evidently built for a cold-room in the summer and a root-cellar in the winter—without a doubt overlooked when the new hotel syndicate took over the hotel. Now—watch out!"

A gust of dank musty air came from the yawning hole. There was something fetid, mephitic, bestial in it. Black as jet, the yawning cavern opened in front of Kennedy and Blount.

Kennedy turned slightly to see that the sheriff was following close behind. Then he deliberately stepped forward into the darkened hole and disappeared in the blackness.

KENNEDY walked straight ahead some ten feet before he stopped. The darkness was so intense that he could see absolutely nothing. Inside the dungeon-like room, the air was warm and there was an odor of either animal or human presence, the odor mixed with the dank, heavy air of the underground cavern.

He threw the white beam of his flashlight around in the darkness. It fell on a jagged rock wall and then on an old table. He flashed it on the other side of the cave. Another wall, and near the wall an old couch.

He threw the light back on the table. There was a candle-stub on the table. He took a step over to it and lighted it. At first the flame of the candle flickered weakly; then it gained strength and cast a wavering light around the dungeon.

Sheriff Blount was standing near the entrance, where the light from the now brightly-lighted cellar died away into the darkness of the cave. Blount walked closer to Kennedy.

"What is this?" he asked. "There is a bed!"

Kennedy was examining a bottle that stood on the table. He pulled the cork, poured out a bit on the table-top, and smelled it carefully.

"I thought so!" he exclaimed to himself. "It's all working out. That's the poison marked in the books."

He examined the cave closely. The rock floor was damp and there was considerable straw scattered over it. Suddenly he reached down and pulled something heavy out of the darkness under the couch. It was a large, flat rock.

"Our tombstone!" he cried. "The murderer hid it here!"

He studied it under the light, especially the wording of the inscription.

"Sir Charles was romantic," he smiled grimly. "He wanted to die unknown and unsung. But he wanted the world to know that he died unknown and unsung."

"Yes. What do you make of this room?" Blount was not romantic. "It still leaves a great deal to be solved about those strange murders."

"It won't; not when we've found the thing we came here for," Kennedy replied. "That bottle of poison tells a great deal. I think the floor will tell more."