RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

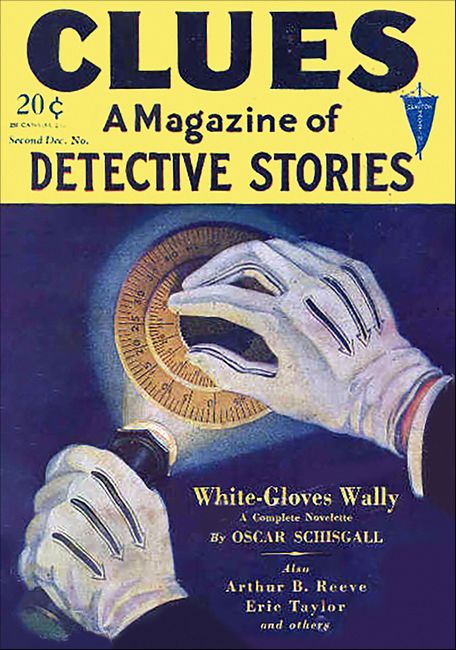

Clues, 25 December 1929, with "The Mystery of the Vault"

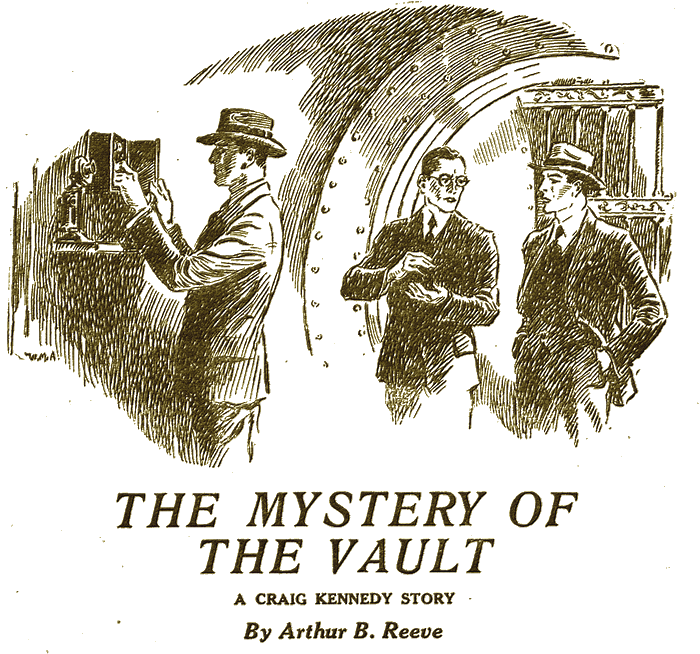

"Kennedy, the new vault, theft-proof in every way, has

been entered and robbed—without a clue being left!"

"KENNEDY, the impossible has happened; only Houdini come back to life or Einstein turned crook could have done it!"

Craig and I were seated beside the big double mahogany desk of James Gage, president of the Broad-Wall Trust Company, in his sumptuously furnished office with its thick carpets, easy chairs and general aspect of affluence.

"The impossible?" echoed Kennedy. "What do you mean?"

James Gage hitched his chair a bit closer, laid his hands on the edge of the desk, one over the other, and leaned forward as he lowered his voice. "The new vault of the Broad-Wall Trust Company has been entered and robbed—and there is apparently not a clue!"

I saw Kennedy drop his eyes from the face of the man to the hands on the desk edge. "Not a clue?" repeated Kennedy keenly, his eyes fixed on the hands as if in abstraction. "No idea how?"

"None of us has any idea," reiterated Gage positively rising and pacing the floor.

Kennedy's eyes shifted from the hands no longer on the desk edge to a photograph in a gold frame on the desk top. I knew that beautiful face. It was Ethel Wynne, late of the Follies, now Mrs. Gage.

"Of course, being the detective you are, you must be acquainted at least in a general way with the safeguards that are thrown about valuables nowadays."

Gage paused before Kennedy, who nodded.

"Someone has broken them all down! We have found bags of lead substituted for bags of gold, packages of brown paper in the place of banknotes, worthless envelopes where negotiable securities ought to be—thousands of shares of stock, even, missing—right out of the vault!" He paused a moment. "It is the most incredible case I have ever heard of, positively staggering. Someone has avoided the network of wires, has been able to defy the half dozen massive bolts on the ponderous doors of our vault, has penetrated the thick walls of steel and concrete—somehow—as if, well, as if he were some relativity thief in the fourth dimension! Before the police come into it, I feel that the least we ought to do is to let the depositors, the stockholders and the public know that we were instantly on the job the moment we discovered it. Therefore I sent for you."

Kennedy acknowledged the compliment but for the moment was silent as if doing a rapid calculation in elimination to decide where best to begin. I tried to reason it out. Here was a burglar-proof, fire-proof, bomb-proof, mob-proof, earthquake-proof vault with all the human, mechanical and electrical safeguards that modern science could devise. Yet it had been entered!

"Has a trusted employee gone wrong?" I suggested.

Gage shook his head. "No single employee could get in there alone for an instant. We have the double custody system. It takes at least two to get in."

"A conspiracy, then?" I suggested.

Gage shook his head as he turned back to Kennedy. "I am one of the two," he said quietly.

Just then the door opened. Gage wheeled about quickly. A woman, young, demure, dainty, chic, had entered. She stood hesitating, as if not quite knowing what to do inasmuch as we were there.

"You will excuse me—ah—Miss Croney?" greeted Gage quickly. "I'm rather busy now. Can't you come in later?"

"Surely," she smiled with a quick look at us. "I'm sorry."

I shot a glance at Kennedy's face and, following the direction of his eyes, I saw that he was gazing intently upon the pretty pink little finger tips, perfectly groomed, that grasped a small leather case. He turned to Gage as she left the room.

"The little manicure in the barber shop downstairs," explained Gage. "I have my nails done perhaps oftener than is absolutely necessary. But I believe in patronizing the tenants in our building and as I'm too busy to leave my office, Schwartz, the barber, sends her in here. I don't know how she got past my secretary unless it's because this news has disorganized all of us who know it—and the rest who don't but suspect something is in the wind."

I was wondering why Kennedy had looked at her so curiously. Might it be one of those many irrelevant things that one runs across in a case, or might it be pertinent? Somehow I could not get out of my mind that picture on the desk. There was something of the same daintiness and chicness about this girl as about the Follies beauty. Was Gage, like so many bankers, a connoisseur? Even if he were, did that have anything to do with it except as a personal matter which he himself alone must answer for? What would personal morality have to do with business morality, anyhow?

I turned as Kennedy asked some question about the company's system and Gage pressed a button under his desk by way of answer.

"Ask Mr. Ingraham to come in a moment," he directed the boy who answered, then added to Kennedy, "—the cashier. When I said we had the double custody system, I didn't mean that I was the one who had part of the combination of the outside doors, for instance. But we have what we call a 'custody trust'—a department for those who do not want to bother with their actual securities. It is a sort of vault within a vault where securities and other valuables are kept. The Broad-Wall handles everything for such customers. Ingraham and I have the combination for that inner vault. Ingraham and Walker, his assistant, have the outside combination for the big door. But it is that inside vault that has been robbed—which makes it all the more impossible to understand. Mr. Ingraham, this is Mr. Kennedy, of whom you have undoubtedly heard, and Walter Jameson of the 'Star.' You remember I spoke of getting Mr. Kennedy on the job?"

Ingraham nodded and shook hands. He was a quiet-spoken man, one who showed that he had long been accustomed to handling other people's money. "You can well imagine, Mr. Kennedy, the consternation we felt when we opened the vault this morning to get some papers for the Vanderdam estate and found such a condition as Mr. Gage has told you. Even yet we do not know the extent of the loss. It will take time to go over everything and check up—to say nothing of finding out how it happened."

Again I saw Kennedy looking at the hands of Ingraham, this time. Of what was he thinking? Had he something in mind like the matter of sensitiveness of finger tips that might actually feel the fall of the tumblers in a lock, feel when they were right and open a lock by the sense of touch? I had heard also of the microphone used in a similar way to enable the opening by the sense of hearing. Perhaps I was not on the trail of Craig's mind at all.

"Trace a robbery," he suggested abruptly, "supposing it possible, from the street to the securities, after nightfall."

"We shall be delighted to go over the ground with you," answered Gage, now leading the way and talking as he went. "First there are the locked bronze doors from the street. They close some time after eight and no one of the tenants of the building or anyone to see them can get by without being observed."

We came to the flight of steps that led down to the vaults themselves. "Next there is another iron door," pointed out Gage, "leading to the stairs. At the foot of the stairs is a heavy barred steel door and a mirror placed at an angle so that a night watchman here can see in either direction."

Kennedy looked quickly about. I did the same. There, in the antechamber, I saw in a rack two shiny guns ready for emergency.

"At last," added Gage, "we come to the main door of the vault." He paused before the ponderous mechanism which now was swung open for the day's business. "The door of a modern vault is a very complex affair. This one contains several thousand different pieces, each ground accurately to the thousandth of an inch. It is over a foot thick, as you can see, and weighs perhaps ten tons. Yet a child can swing it on its specially designed and balanced hinges."

"H'm," mused Kennedy. "Four complicated locks to be picked—one of them of latest pattern shielded by impregnable armor." It seemed as if an idea flashed over him. He bent over and examined the time lock. It was in perfect order. "I recall a case where the time lock on a safe had been rendered inoperative and it was never discovered until after the robbery because no one ever tried to get in until the correct time. But this lock seems to be all right."

"To say nothing of the other locks inside," put in Gage "and a network of sensitive electric wires, the burglar alarms, concealed in the walls and floors, the location of which is not generally known."

We had passed the door, the last line of defense. There was a treasure house to make Croesus look like a cheap skate. Everywhere was money in every conceivable shape and form, as though a modern Midas had by his magic touch transformed everything beyond the wildest dreams of avarice.

"And the vault itself—the walls?" Kennedy tapped them.

"The body of this vault," answered Ingraham quickly, "is built up of steel plates bound together by screws from the inside of the vaults so that the screws cannot be reached from the outside. The plates themselves are of two classes, those of hard and those of softer steel, set alternately, so that they are both shock and drill proof. The steel of high tensile strength is used to resist the effect of explosives while the other has great resisting power against drilling. It will wear smooth the best drills and only unlimited time would suffice to get through that way.

"Then there is a layer of twisted steel bars added to the plates, another network to break any drill that may have survived the attack on the steel plates. That also adds to the power of resisting explosives In fact, the amount of explosive necessary and the shocks it would produce simply put that method out of the question. Why, where the outside plates come together to form the angles and corners massive angles of steel are welded over the joint. The result is a solid steel box, all embedded in a wall of rock concrete—impregnable—absolutely impregnable!"

He paused, then finished, "The door is the only possible chance, in my opinion. That is water-tight, gas-tight, ground to the minutest fraction of an inch, with seven steps in it. The most expert yeggman who ever lived would have no chance at that—unless he were a lock expert endowed with omniscience and unlimited time. So, you see why it is that we say that the impossible has happened!"

Inside the huge vault were various other protections, tiers of safety deposit boxes for which an elaborate system of safety had been built up, safes for various purposes, and in the far corner a vault within a vault, the vault of the "Custody Trust Department."

Gage opened it with Ingraham's aid, each knowing only part of the combination and neither being able to work it in such a way as to be seen by the other.

In this inner vault were rows and rows of fat packages tied with little belts of red tape. Gage picked up one and opened it. Instead of crinkly examples of engraving that represented a fortune, there was nothing inside but common brown paper!

"Just stuffed in merely to satisfy a casual glance that the envelope has not been tampered with," he explained. "Now, here's something else."

He opened a small, heavy money bag which he took from a little safe in one corner. We looked in, too. Instead of bright, gleaming gold pieces apparently salted away against the remote possibility of a panic when gold might be at a premium, there was a mass of dull dross lead!

"What do you make of it, Mr. Kennedy?" inquired Ingraham helplessly.

I felt that a plan was already forming in Kennedy's mind but he said nothing about it. Instead, he merely shook his head. "I shall have to do some outside work before I can even attempt to answer that, Mr. Ingraham."

I looked from Kennedy to Ingraham and Gage. Neither of them apparently even laid claim to having an explanation. As I learned afterwards, as Craig told me how he reasoned it out, only one idea was uppermost in his thoughts at that moment. Why had the robber been so careful on the surface to conceal his stealings? Clearly, he was not through. He had carried on his thefts for some time; not all at once. He intended evidently to come back. And surely the temptation of what remained still would be strong.

As we turned to pass out, Craig noted a telephone on the wall. "That, I suppose," he observed, "is to communicate with the outside in case anyone is shut up here?"

Ingraham nodded.

"I am going uptown," remarked Kennedy. "After I have been to my laboratory I shall want to come down here again. I shall find someone to let me in down here?"

"Certainly," answered Gage quickly. "You—you are not laying any plans to stay in the vault?"

"Of course not," hastened Kennedy.

"Yes; I gave you credit for that intelligence," smiled Gage. "You would be suffocated, you know."

"Surely. But will you do one thing to-night—have the time lock on the outside door left inoperative?"

Gage thought a moment. "It's an unprecedented thing, but—do that, In-graham."

Instead of leaving the building immediately after we parted from them, Kennedy looked about carefully keeping in mind the location of the vaults. We were passing the barber shop in the basement when his eye caught the trim figure of the little manicure, Miss Croney. She smiled at him and he caught my arm.

"Let's go in, Walter," he decided. "You can get a shave. As for me, time spent talking to a pretty girl is not wasted."

In a moment he was chatting with her across the little white table while I had the luck to obtain the proprietor, a middle-aged man, rather good looking, a man with those eyes that seem to bulge as if with exophthalmic goitre. I saw Kennedy taking us all in, the boss barber whom everyone called Schwartz, and all the other customers and barbers.

"I suppose you have some well-known people in a building like this, Miss Croney," Craig ventured. "Queer experiences, too."

"Yes," she answered apparently engrossed in her work, "but I like it. I take it all as it comes. It interests me. Do you know, you can read character in finger nails, just as well as in hands?"

"I suppose so," prompted Kennedy. "How, for instance?"

"Oh, I have quite a philosophy of finger tips. I have studied actual people, some men prominent in various ways."

"How about mine?" he asked, taking a sudden interest in her.

"Well, for instance, you have the scientific temperament, I would say. You'll pardon me—but it is usually known by one of the worst nails and cuticles the manicure encounters. See —a nail of ordinary size, rather discolored, the cuticle so erratic that it takes a great deal of skillful work to make it look beautiful."

"And our friend, James Gage?"

"He has a large, broad nail, the nail of a good liver, a good spender, a man of good nature."

"You know Mr. Ingraham?"

"He comes in once in a while. He has an aristocratic nail."

"How about Mr. Walker, his assistant?"

She looked up quickly. "You know them all, don't you?"

"Oh, slightly."

"They seldom come in here. Besides, I don't like to talk too much about my customers. You wouldn't appreciate my talking to them about you, would you?"

Kennedy turned the subject and as we left the shop he was unusually thoughtful. "A clever girl, that Miss Croney," he remarked to me. "Somehow, I'm thinking about another girl. It's surprising how much you learn by studying girls. Now, how can we get the low-down on Ethel Wynne Gage?"

"Drop by at the Star," I answered promptly. "If Burton, who does our Broadway stuff, is there he will know. He knows all the Follies and Gardens and Scandals, everything."

Burton was there, and it was not many minutes that he neglected the sheet of paper sticking in his typewriter before he had spilled enough to intrigue us.

It concerned the notorious afternoon dance and night club known as the Golden Glades. It was there that Gage had often gone with pretty Ethel Wynne of the Follies and it was there that she still was seen sometimes with her husband, sometimes with a friend.

"I see her with another girl often, Madeline Croney," he added, whereupon Kennedy's interest was suddenly aroused. "She's a manicure downtown. That might be just a cover for the daytime, for I often see her with Dave Wharton, the proprietor of the Golden Glades, sometimes the four of them, but more often just the three—Ethel Wynne, Gage and Wharton, at night; Ethel Wynne, Wharton and Madeline late afternoons. I hear the four, though, have sometimes made up a week-end party on a fast cruiser, the Sea Vamp, that Wharton owns."

Kennedy asked a few questions of Burton before we ran along. I was unable to decide whether Dave Wharton might be the "other man" to Ethel Wynne, or just the "boy friend" of Madeline Croney. However, there was not time to pursue the inquiry, for Kennedy's chief concern seemed to be his visit uptown to the laboratory and getting back again to the Trust Company before it was too late.

He did not stay long in the laboratory, but from a cabinet where he kept his various contrivances developed in his warfare of science against crime he took a queer little arrangement, somewhat like a simple coil of coated wire.

"To-night, Walter," he said as we returned downtown, "I shall probably have you scouting around the outside. I will provide some way so that you can keep in touch with me by calling up from pay stations or other phones."

It was nearing closing time when Kennedy was back again at the vaults and Gage directed his secretary to accompany Craig on a second visit to the custody vault which had been left open but under guard for him. As they passed down together through all the various safeguards, Craig remarked, "And yet all this did not protect!"

"No," observed the secretary, "the system has fallen down, somewhere."

"Who is this Walker?" inquired Kennedy casually.

"The assistant," replied the secretary. "Rather a clever fellow—always on the job."

"I wonder if he knows anything more than has been told," remarked Kennedy, apparently merely thinking out loud.

"Impossible," exclaimed the secretary catching the drift of the remark but not noticing as I did that Kennedy's mind was not really on it.

I had caught the fact that Craig was talking really to divert the attention of the secretary from what he was doing, for in the meantime, while he was taking down and putting back the wall telephone in the custody vault in an inconspicuous corner, he had actually closed the circuit cutting out the telephone but cutting in the peculiar little arrangement he had brought from the laboratory in such a way that, although it was exposed, it was not noticeable.

"Now, is there a little office upstairs that I may use?" Craig asked the secretary, sure that he had not comprehended the change that he had made.

The secretary nodded and a few moments later Kennedy was settled with a desk of his own, telephone, key to the door, able to come and go as he pleased in the building and acquainted with the switchboard that connected all the interior departments as well as the outside wires.

For another hour he was busy and I noted that it was a comparatively simple arrangement that he placed on the top of the desk. It consisted of nothing, apparently, but an ordinary electric buzzer with a relay and dry cells.

During the rest of the afternoon Kennedy stuck pretty close to his improvised office, getting acquainted with such of the employees of the building as he would find it necessary and useful to know at night, and instructing me what to do and how to keep in touch with him from the outside.

Nothing further developed around the Broad-Wall Trust Company during the day and as closing time approached Kennedy sought out James Gage to decide exactly how he might keep in touch with him during the evening, as well as with Ingraham and Walker. "I may need you at any time," he remarked, "and when I do I shall want you all quickly."

"Where?" asked Gage.

Kennedy thought a moment. "I can't say yet. But I shall depend on you to keep in touch with Ingraham and Walker."

"Very well, then. You'll find me at my club. I was going to the theater, but I shall cancel that. I'll instruct them to be on call, too. You may depend on it."

My own conjectures were considerably enlivened when I learned late in the afternoon on dropping in at the Star from Burton that he had just heard that the cruiser, Sea Vamp, always lying in readiness off Kip's Bay in the East River, had quietly slipped out in the Sound.

"Who's on it this trip?" I asked.

"No one but Dave Wharton. That's how I came to hear it. A couple of chaps with a Broadway racket dropped it in the course of a conversation and I immediately thought of you and Kennedy."

"What's it all about, do you think—Wharton alone? What's the racket?"

"Well, their racket is booze. Wharton's racket is night clubs. Maybe it's a little rum-running, or maybe it's something else. I thought you'd be interested.

"I am interested. So is Kennedy. Thanks awfully." I did not think it necessary to take Burton into my confidence to the extent of admitting to him that Kennedy was as usual as great an enigma to me as if I were not his most intimate friend.

It looked to me more like running to cover than rum-running. Kennedy was interested when I told him. But he did not appear to let it change his plans in any respect. Under his instructions I was in for a night on the streets of lower New York with the prosaic job of shadowing the outside of a building.

Hour after hour the evening sped by as Kennedy waited in the little improvised office, turning over and over in his mind the facts that he had collected.

On my part I determined to let nothing escape me. Once I called up. "Craig, a car has just driven up to the curb around the corner from the entrance."

"Did anyone enter the building?" he asked quickly. "No."

"Watch it, Walter; it may be important."

I myself had thought so. If the car was standing ready at a moment's notice for someone to slip into, throw in the clutch and whirl away, it might be just another instance where a motor was one of the efficient criminal instruments. I wondered if perhaps the trail might lead to some gangster garage, dark, unpretentious, whence came cars often stolen and repainted, in which racketeers traveled on missions of plunder or revenge.

Suddenly in his office the little buzzer on Kennedy's desk gave a faint buzz, then louder. There was no mistake about it. It settled down next into a continuous buzz.

Quickly Kennedy called Gage at his club. "Come down—immediately. Bring Ingraham and Walker."

Craig waited for my next periodical call. It had always been his rule that the fewer people he took into his confidence the fewer weak links there would be in forging his chain of evidence.

At last I called. "Walter," he fairly shouted back to me, "has anyone entered the building from that car or any other?"

"No."

"Then watch the door! Don't let anyone at all out—no one! Understand? I am arranging to have someone there to support you in—"

"Craig!" I interrupted. "From where I am standing I can see a big black closed car which has just drawn up to the door. Three men have got out and are going into the building. The car is waiting."

"Very well. Then get over by the door—quick. There will be someone there to help you out if anything should happen. Play safe—until you hear something suspicious from inside. Then pull your gun—and, Walter, remember, in these quiet streets downtown a police whistle may be better even than a gun—at night!"

Kennedy had scarcely finished the call when his door was flung open after a hasty shuffle of three pairs of feet down the market floor of the corridor. He was on his feet, his hand on his gat.

"What is it—what's the matter?" cried James Gage, who was the first to enter. "Where are they? Where have you got them?" He had seen Craig's automatic and quickly assumed he was holding someone.

Kennedy laughed and motioned to the still buzzing announcer.

"What is it?" inquired Gage. "What does it mean?"

"Down there in the custody vault I have placed what is known as a selenium cell and a relay, attached to the telephone wire leading up here. Now that you are all here," he added, turning to Ingraham and Walker, "let me open that vault. You see, now, why I left that time-lock inoperative. Something is going on down there. Come on!" he added, dashing for the stairs.

"Selenium?" puffed Gage as he followed.

"Yes," called back Kennedy. "Hurry! It is a peculiar element, a poor conductor of electricity in the darkness, a good conductor in the light. I reasoned it out this way. Suppose someone should enter the vault. The first thing would be to switch on the lights. Light would act on the selenium cell, complete the circuit; then this buzzer would warn me."

It seemed incredible. Down below, hidden by impenetrable steel walls and doors, there was a light shining on that tiny selenium cell tucked away in the custody vault. Someone was there! It was weird, as if a phantom hand had reached through the cold steel and cement and turned on the lights!

One might have expected to see the heavy steel door open, perhaps the night watchman killed. But, no. The door was closed, just as Ingraham and Walker had left it; the night watchman was sitting there vigilantly on duty, more surprised than ever at seeing Gage and the rest at that time of night.

One after another, the heavy bolts were shot back as Ingraham and Walker worked the combination. Inside the big vault all was in darkness.

Next Gage and Ingraham began to work over the door of the smaller vault in the rear of the interior. Finally it, too, swung open.

There was burning a bright light!

What was it—an incandescent witness to man or devil? Unconsciously they drew back for an instant as the door swung noiselessly open. Yet no one was there, apparently.

"He must have escaped!" exclaimed Ingraham.

"Escaped?" rejected Walker looking at the thick walls and the doors. "It is impossible. It simply cannot be."

Kennedy was going over the interior of the vault carefully and quietly without a word. It seemed hopeless. No one could have got out. Yet someone must have got in. And there was no one there.

He had come to the small safe standing in the corner. He paused. "Come," he shouted, "give me a hand!"

Together they moved it. It rolled surprisingly easy on its well-oiled wheels.

"Look!" cried Kennedy who was nearest.

There in the smooth steel wall yawned a black hole, big enough for a man's body to wriggle through. The wall had been penetrated by a careful calculation which brought the hole just behind the safe. Then with a lever the intruder had been able to move the little safe back and forth to hide the entrance through which, night after night, the treasure house had been visited.

Without a moment's hesitation, Kennedy plunged into the hole, wriggling his way along and calling back from time to time as he progressed. "It runs into the basement of the building," he panted, "and ends back of a closet in the barber shop. One of you come through after me; the other two hurry around to the barber shop."

He wriggled on through the tunnel. A moment later Walker followed. In-graham and Gage started around the other way.

All was dark in the barber shop. Not a soul was there. Apparently both Schwartz and his pretty manicure had long ago shut up the shop and left it. Who, then, had used it during the long, silent hours?

Kennedy switched on the lights. In a closet he disclosed two large bolt-studded tanks, with dials and stopcocks and tubes attached. He stooped and picked up a goose-necked instrument like a distorted double-U, with parallel tubes and nozzles at the end.

"What's that?" demanded Walker.

"This new cutter-burner, the improved oxyhydrogen blowpipe with which steel can be cut with scarcely more effort than slicing cheese with a knife. It's all the same to this thing—hard or soft, tempered, annealed, chrome, harveyized. It will cut cleanly through them all. It gives a temperature so high that if a cone of unconsumed gas, forced out under pressure, did not protect them, the nozzles themselves would be consumed!"

Walker looked at Kennedy aghast. "Robbery with this person must be an art as carefully planned as a promoter's strategy or a merchant's trade campaign!"

"It is! Night after night someone must have worked patiently, noiselessly with the cutter-burner. Carefully it must have been calculated to come out just back of the little safe. It looks as if someone must have had inside knowledge to do that and avoid the network of wires!"

Suddenly Ingraham, pale and excited, broke in on them. "Mr. Kennedy!" he cried. "There's been an attempt on Mr. Gage's life!"

"What?" asked Craig, still unruffled. "How did it happen?"

"We were going through the hall as you directed. As we reached the door to the street I turned. For a moment I thought Mr. Gage was going out on the street instead of—"

"Yes—instead of what?" Kennedy was thinking of me and my probable action under the circumstances.

"Instead of coming here with me. But it was a woman facing him—a woman and a man, at the door. She drew a pistol, a little ivory-handled pistol, and fired squarely at him. I saw my chance. Before she could fire again, I seized her arm and wrenched the gun from her." He handed the pistol, still warm, to Kennedy. "The man was not armed, I think. But with Mr. Gage wounded, they were two to one against me. Hurry!"

"A woman?" repeated Kennedy following quickly. "Who?"

"I think it was that Miss Croney, the little manicure in the barber shop. The man I couldn't see very well in the dark. But outside, on the street, there seemed to be another man, holding the door!"

Indeed there was. It was I. No one was going to get out until I saw Kennedy.

Kennedy hurried to James Gage who was weak with the shock and the loss of blood from an ugly wound in his left shoulder on the arm. He was bracing himself gamely against an angle of the now deserted cigar stand in the lobby.

Kennedy tore a strip from the shirt of the wounded banker, hastily improvising a tourniquet. "Here, Walter, twist that —tight," he directed as he opened the door and I stepped in. "It may stop the flow of blood, while I get help."

"Oh—it's nothing," groaned Gage.

Kennedy, with his own automatic in one hand and the little ivory revolver in the other, stood in the street door that was open. Outside I had been giving rapid blasts on my police whistle. The other doors were locked. Down the line of street doors that were locked a man was battering and storming at one.

"Let me out, I say! This is an outrage! Let me out!"

Shrinking into the corner was a girl.

"Come, Schwartz!" called Kennedy peremptorily. "Stop that noise—hands up—about face—now march into that corner with Miss Croney—straight ahead—and if you turn your face or move a muscle of your arms—I'll let you have the works—right in the back! Ingraham, Walker, someone, just watch Miss Croney. She's unarmed now—but don't let her take any poison or anything like that. Walter!"

"Yes, Craig!" I answered. "I've done the best I can with that tourniquet. I think I hear the police coming, around the corner."

"Good! Get the cars and the drivers you saw. Tell them to do it. We're perfectly able to take care of ourselves in here, now."

"All right!" I took his place at the unlocked door.

Craig turned toward the barber who was standing sullenly, his face in the corner. "Pop-eye Pete Schwartz," he said quickly, "I recognized you at once this forenoon in the barber shop. I thought you might have something to do with this affair but wasn't sure. You've been out of Dannemore a year now. I understood you had gone straight. But you couldn't keep straight, could you?"

"All was going straight—" The man was muttering something unintelligible, about "the girls."

"Yes, I know. You had two girls and a boy. Well, I gave you the benefit of the doubt. But I didn't propose to let you or any one else get away with anything without getting caught. If you hadn't been so avaricious for yourself, if you had been contented with doing only what you were set to do, you might have made it much harder for me. But I figured out you were coming back."

Gage, in spite of the pain, was glaring savagely at both Schwartz and Madeline Croney.

For the moment it seemed as if every roundsman below the dead line was pouring into the hall from the street door.

"I know—two girls and a boy," Kennedy was saying. "Madeline, Ethel and Dave. Dave's in the liquor racket on Broadway. One of your girls went in the show business."

"Miss Croney" was sobbing convulsively at the sight of the massing of so many cops.

"Don't be too hard on father," she cried looking about wildly and avoiding the savage glare of Gage. "He—we were to make a big haul—but it was—to save the name of another."

She paused, startled, as a bright steel gleam told of the slipping by Kennedy of a pair of bracelets over the wrists of Pop-eye Pete Schwartz.

"There was someone," she was biting the words off contemptuously, "who was a million dollars or more short in his accounts—lost every dollar in this market. He could not return it—and it was only a matter of a few days when he would be discovered. Running away was out of the question. So, he devised a plan for retaining his good name and at the same time recouping his fortune. He got the idea when he discovered by chance who my sister really was—Ethel Wynne— Schwartz. It was to have the Trust Company robbed. Enough was there, where he could direct the robbers, to re-establish him and to pay them well for their trouble. Then, when the robbery was discovered, he said he would merely add to the loss what he had hypothecated—and make it the greatest robbery since the Manhattan Bank affair!

"He had heard about Pop-eye Pete, my father. So he came to him, put the plan up to him, begged him, threatened him. I told father he was a fool. We were happy—he had a good business—my sister had got in the Follies and was happily enough married. There was nothing they could get us for. But the man kept on. He knew the only vulnerable spot in the vault—knew how a cutter-burner could be used to reach it safely—had the whole plan worked out for making it seem like an inside job to the detectives—until the real way was discovered.

"I was installed as manicure, with my father as owner of the shop. Every night we worked. But it could not be for many hours, for fear someone might suspect why we kept the shop open so late when there were no customers downtown.

"At last the tunnel was complete. We did the trick. We were removing the traces of evidence, even. But the temptation was too great for my father. He wanted more! I told him that I suspected something—that I had read the hand of a man who came into the shop and that he was a scientific genius, that I suspected that man because I had seen him in an office upstairs—suspected that someone was not playing fair with us. It was no use. He took the chance. . In the midst of the final clean-up, we heard the bolts shooting back in the big vault. We crept through the hole and fled. But the outside street door was locked and guarded—by one of those very men who came to the shop. We were trapped, like rats. Who has done it? Who played false? Why?"

She paused in her rhetorical treble. Kennedy turned.

"Pop-eye Pete," he said gravely, "I knew you could not be the man higher up. I knew this must be made possible only through someone on the inside. Your daughter Madeline has been loyal to you. To save you, she has betrayed the real robber—an officer of the company who was leading a double life."

"Yes—double, all right!" There was a fury in it as of a woman scorned. "Ethel didn't have to play his game—against us! What difference did it make if he was ruined—to her? There's just as good fish to be caught on Broadway as he was and she could have caught 'em, again! I don't know whether you'll get her, too, on this. But I'm going to turn state's evidence! I'm sorry I didn't have a machine gun instead of that damned little thing—and get him!" She hissed out the words venomously.

"It's all a lie—blackmail!" muttered a hoarse voice.

"That will easily be shown by an examination of the books," ground out Kennedy. "I suppose I myself was picked out for the role of the boob detective because I happened to be available. I suppose the idea was that I was to fail to discover the actual bank robbers—at least I was to let the real robber escape. But I took this case with the determination to let no one, big or little, slip through my fingers. No one has slipped through them. My first clue came in the studying of fingers—a man's finger nails—the clue to his character."

Kennedy paused. I thought of the little manicure and her philosophy of finger tips. Craig had beaten the manicure at her own game.

"No one can tamper with money and passions, flout the moral law—and get away with it—long." Kennedy turned on 'his heel. "Come, Walter, I think the police and the district attorney can take care of James Gage now!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.