RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Country Gentleman, November 1925, with "Harvest Home"

"Craig Kennedy on the Farm,

Harper & Brothers, New York, 1925

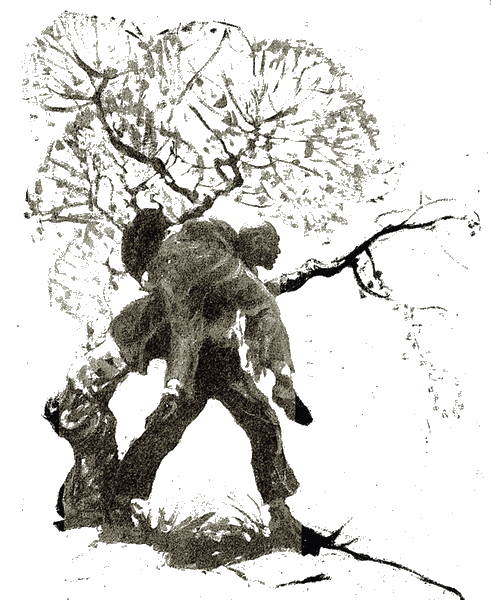

"CRAIG! Look at that fine apple tree—blasted!"

It was harvest time in New Jersey. Yet the tree, a splendid pound pippin, was dead, literally shriveled up. It must have happened suddenly too. On all its branches was dead fruit among the seared leaves—fruit which would have been perfect had it not been for this overwhelming blight. On the ground under the tree was a dead robin.

Everything about the tree was blasted, too, even the grass and the orchard flowers. There was a stillness, a remoteness about it that bespoke tragedy. It hung so heavy that the natural living things seemed to have absorbed it. Not a leaf stirred. Only the silence of sorrow and death was all about.

Kennedy had already seen it before I spoke. "I think, Walter, that must be where they found the body of Squire Duryea." He turned to Sam, the old negro who was driving us in the flivver from the railroad station to the Duryea place. "How did that happen, Sam? "

"Maybe you can tell, sah."

Sam paused and slowed up the car. There was every evidence of fear as well as of grief on Sam's face. Elemental by nature, he did not care who saw his emotions. The gray was tinting his woolly head, and his shoulders were slightly stooped, as with many who have worked long in the fields. But there was a dignity about Sam. He was a good soul, loyal, dependable. Sam had never read a copy of the Call nor had he ever heard of Marcus Garvey. He was of the old time and it had given him many commendable qualities.

Sam, as I have said, had met us at the station on this hurried summons out to Good Ground, and had driven us past the neat white cottages with their well-cared-for brilliant gardens of dahlias, chrysanthemums and cosmos to the Duryea place, marked by two simple brick pillars at the road entrance, then on uphill toward the house, through acreage that told of the close of a season—corn stacked in the fields, pumpkins turning yellow in the furrows, apples hanging heavy, ready to be picked.

"MAYBE you can tell us, sah," repeated Sam with a shake of the head and a shake in his voice. "I can't. It happened yesterday when the squire was away. I wouldn't let no one go near that 'ere tree las' night. Then he come back this mohnin'. That's whar I found the squire, dead, sah, right under that 'ere tree, not an hour after he come back, an' jest befo' Miss Duryea telephoned you, sah."

We had paused in this lane that ran by the orchard. Over in the corner of the orchard nearest us, as if standing in isolated grandeur, was this strangely-stricken tree.

A moment later we heard the crunch of steps down the driveway. I turned to look. A beautiful girl was advancing toward us. She seemed to be about twenty, not a day more. I thought the squire, if he had had anything to do in the raising of that girl, must have been an adept in culture other than agriculture.

She was of medium height, with a springiness in her step that seemed to add the quality of fairy lightness to her form. Her dark hair was bobbed and clustered in curls about her face. Her blue eyes were entrancing, with their little trick of looking steadfastly at one, with surprising candor and intelligence in their depths. She wore no hat, and her light-colored woolen dress in shades of tan and green made her a wood nymph.

"Little Doris Duryea!" exclaimed Kennedy, turning to meet her in admiration.

"Little no longer, Mr. Kennedy." She forced the smile. "I heard the train whistle, and you didn't arrive at the house. Then I thought I might find you here. I knew you would have to pass this spot. Uncle just doted on that tree. It's famous in this part of Jersey. Duryea's pound pippin apple tree is known all over where harvest homes and interstate fairs are held. Uncle Theodore used to exhibit its fruit every year. Why, he intended to send some of it to the harvest home tonight at Good Ground. But look at it. It's all dead! There was even a dead bird under it—there—and the dog, his dog, Jerry—poor Jerry.... Sam buried him.... Why, the squire never even let anyone else pick and handle this fruit. Everyone knew it. He always did it himself."

Doris Duryea, an orphan, was the only child of the squire's brother. The squire and his wife had brought up Doris and lately she had been appointed teacher in the little country school out that way, between towns.

"Sam tells me he discovered it," prompted Kennedy.

"Yes." Doris answered slowly and doubtfully. "Sam saw something—last night. He came and told us. But he wouldn't tell what it was. I looked down the lane, but I didn't see anything. Uncle Theodore wasn't home. I thought Sam was sort of superstitious about something at first. He didn't want anyone to go down this way. I guess some of his feeling got into me. I kept away, went out the other drive."

"No, sah, Mr. Kennedy," emphasized Sam. "The old boy been in that tree. I knowed it then. I knows it now. And, sah, the squire he was down Trenton makin' some 'rangements for the big fair there, later—"

"He was in that, too, every year; always-rounded up the exhibits in this section of the state," explained Doris. "Really, Uncle Ted was the inspiration for the fine crops about Good Ground. He stimulated good-natured rivalry among the farmers. But none of them had his farming sense and his luck. They'll miss his advice and encouragement."

The girl's lips trembled with emotion. She was like a broken-hearted child. Craig touched her arm, but the sympathetic touch was too much for her. She broke down.

"I—I keep so quiet in the house. I don't want to make it harder for Aunt Mary. I—I'm afraid it will kill her. All she does is sit so still and straight in uncle's old Boston rocker."

FOR some moments I had been impatient to wander over to that apple tree. I wasn't superstitious in the least over Sam's remarks. But I was curious.

"Craig," I volunteered at length, "I'm going over to have a look."

Kennedy reached out quickly and caught my arm. "Don't, Walter—don't go."

I hesitated with a laugh. "What! You superstitious too?"

"No," he replied sententiously. "Not precisely."

"Then why can't I go?" I persisted "Sam was there this morning. He just said so."

"Yes," agreed Kennedy, "I know all that. But Sam is a negro. You are white. Wait until I say it is safe"

I am afraid I showed incredulity at Craig's caution. I know Doris, in surprise, quite felt her grief smothered by an unknown alarm.

We went on to the house to see Mrs. Duryea and the body of the unfortunate squire.

The Duryea place in Good Ground was between Hopewell and Blavenburg, one of the finest farms in the country. The squire had named it "Fourwinds."

Squire Duryea had made a profession of farming. He was never satisfied with just crops. They must be superlative crops. And he knew the old science of farming so well that could get them.

WE had been gunning there in the fall for quail and pheasant, even for rabbits when other game was not so plentiful. Genial, talkative and hospitable, everybody liked Squire Duryea. Cold winter mornings we had been up at his place, with the snow about and visitors coming in. As squire he had an office with a big wood stove in it, and a china cuspidor decorated with carnations, which sat on the zinc square under the stove. The squire was no drinking man himself, yet in the old days there was always a quart conveniently near, and he was a generous host. Such stories, such yarns, such kindly gossip! The simplicity of his way of living had been a relief to us. I never could get over the incongruity of that carnation cuspidor, a work of art from a pottery in Trenton.

Mary Duryea couldn't talk. There was just a compulsive pressure of a handclasp and a forlorn, helpless glance at Craig that conveyed better than words the absolute desolation through which she was passing. It seemed hardly possible that this woman was the active, bustling friend who had risen early to see the squire and his friends set out on their hunting trips. Without the squire she was like a flower without the sunshine.

It was a relief when a friend of the family led us into the big room, the formal parlor. Here they had taken the squire. Craig himself seemed stunned, muttered under his breath at the sight of his friend.

As for me I fain would have looked away, but could not. The squire was burned, as it were, or, rather, blistered in spots all over his face and hands. What was this? What new kind of tree blight?

Kennedy examined the body carefully, closely taking into account the vesicles that had formed over the burns or blisters, whatever they were. Then upon a piece of clean gauze he wiped off some of the humor that oozed from a punctured vesicle.

As I watched, I wondered at the effect it was having on Craig. A grim, determined look was on his face.

"If it is what I suspect, there is some fiend about—or some fool!"

BACK again with Mrs. Duryea and Doris, Kennedy contrived to secure a quiet moment with them alone, away from the neighbors.

"Was there much rivalry hereabouts over that pound pippin tree?" he asked casually.

"Oh, yes," replied Doris. "All the folks were trying to beat the squire. They always tried—but didn't succeed."

"Who seemed to come nearest?"

Doris lowered her eyes. I fancied a slight flush on her face, but she answered without hesitation. "If I tell, Mr. Kennedy, please don't let that influence you. Our minister in the little church, Lionel Tapley, had the second best tree, I think." She paused a second, then added as if to account for him last night, "I was out with him calling and driving last night. His mother is helping Aunt Mary make the arrangements."

Did I begin to see the trend of Kennedy's questions, as he felt about for information? With no children of their own, Doris was the heir to the Duryea property. Might not the crime have been done for some other reason than pure jealousy over prize apples? A prize beauty, with a substantial dowry and an annual income, might be something to prompt a murder.

"Who else had trees?" continued Kennedy, for the time ignoring the lead opened by the last remark of Doris.

"Both our neighbors, Bob Winslow and Jake Cushman, on either side of us, had wonderful trees." The voice of Mrs. Duryea seemed to come from far away.

"Were any other pippin trees blighted?"

"Not another tree in the vicinity has been touched as far as we know, and we would know, now."

Kennedy was casually making other inquiries as to the friends of Doris. It seemed to interest him who called on her, who might be considered intimate. Doris was quite naive about it. She was popular and didn't seem to be aware of it. A debutante in the city could have had no larger following.

From her answers one could gather that of them all there were just three who kept her busy inventing means of dividing the leisure time which the school left her. It was pretty evident that she thought the most of Parson Tapley. But then there was his rival, Jake Cushman, a young farmer who had come up from Maryland with more ambition than either capital or farm lore, inheriting the large place next to Fourwinds.

The third whom she mentioned was the village druggist, Francis Mahoney, who, in addition to his studies in pharmacy, had taken a course in scientific farming and was selling in his shop many newfangled chemical and other devices to increase the yield of the soil. He had been led into the study through his chemistry, and knew something about the chemistry of the soil. Now he was trying to take advantage of his knowledge to eke out the precarious profits of his little drug business.

"I suppose you'll drive me down to the village, Sam."

Sam, feeling for the time being his importance locally as a member of the stricken household, was quite willing. But I noticed he departed by the other driveway from that past the blasted tree. Craig let him do it.

It was Craig, too, who broke the silence as the flivver rattled along toward town. He had evidently been reserving this question for the proper moment and had planned for the moment itself.

"Sam," he asked quickly but impressively, "what was it that made you say the old boy was in that tree?"

Sam's eyes opened wide. He had not expected that question. The shock of the sudden query was felt even in the steering wheel.

"Oh, he was there all right, Mr. Kennedy! I just knows it!" The answer came in a lowered tone. Sam was convinced; at least he wanted to convince us.

"But, why?" persisted Craig. "Surely you must have a reason."

Sam was shaking his head, in grave danger of running us off the road. "I knowed las' night. I knowed when I told Miss Doris to keep herself and Parson Tapley or whoever she was goin' out with away from that 'ere tree. I knowed better'n ever when I see Squire Duryea dead under it. Oh, I knowed! Heaven help us all!"

"But what did you know, Sam?"

"Ise a'most afeared to tell, Mr. Kennedy.... But las' night I was gazin' down the lane and when I looked down 'ere along by that pound pippin tree I a'most forgot how to run! It was a blaze of light, sah, like glory come. No flame, sah, you understand. Just a blaze of light—a pillar of fire by night. It was like a great ghost, sah! Then it was gone—and I run—oh, how I run! Only the old boy'd work tricks like that!"

"Then what did you do?"

"I run," he reiterated. "I run to the house. I meet Miss Doris and I know she gwinter mos' likely meet Pahson Tapley down 'ere by that 'ere tree like other nights. I tole her keep away from it till mohnin'. I never slep' a wink. It was only in daylight I have courage to go see what cause them lights.... The old tree was dead! And the dawg! And a bird! I warn the squire. But he would go. When he don't come back, I look. There he was, dead, next mohnin'. I run, I carry him, but I do it in a powerful hurry. Yes, sah! I don't want no ha'nts after me. Maybe tonight I pray too. I don't know." Sam repressed a shudder.

"The old tree was dead," said Sam. "I run. I carry the squire."

"LIGHTED up like glory come—no blaze," Kennedy repeated to himself. His brows knit in thought, but somehow I felt that the idea had given him a lead he had not had a moment before.

"Sam," he added, "do you know any young fellows here who were in the service who went overseas?"

"'Most all the young fellows was over, sah. Pahson Tapley he was a chaplain. Mr. Mahoney, the druggist, he was in the second battle of Yippers. He was with the Canadians. Oh, pret' nigh all our neighbors had a son or more in the ahmy."

"The second battle of Ypres? He was?" Kennedy seemed quite interested "Let's drive down to Mahoney's drug store. I want to see him."

We pulled up before a little frame store on a corner with a door with a fanlight and sidelights, one side of red, the other of blue.

Mahoney looked up from his counter as we entered. He was a rather handsome chap, three or four years older than Doris. Sam had come in with us to make us acquainted.

"Sam here tells me you had some great experiences over there," Kennedy plunged directly into his subject.

"Oh, I happened to be in a busy part of the scrap; that's all—not by preference."

"Did you ever get bumped by the gas?"

Mahoney thought a moment. "It didn't get me."

"I wonder if you are one of those fellows who kept things to remember the war by. You were in gas attacks after Ypres. Did you manage to keep your gas mask as a keepsake, by any chance?"

The druggist did not answer right away. A customer came in and he waited on her. She went out. Mahoney returned slowly.

"I'm wondering if you kept your gas mask," repeated Craig. "I want to use one, very much."

Mahoney was certainly very reticent. He was still looking searchingly at Kennedy when another customer entered. He was a studious-looking young man, yet rather handsome.

Evidently the newcomer had heard the question when Craig repeated it. "Why can't you lend the gentleman your old gas mask, Frank?" the newcomer suggested.

"Well, parson, it ain't so good."

So, I thought, the newcomer was Parson Tapley.

"Get it out," urged Kennedy. "I think I can fix it up."

From a cabinet in the back of the shop Mahoney produced the gas mask reluctantly.

THERE was one part where the fabric and rubber had deteriorated. Kennedy made a skillful attempt to repair it.

Mahoney watched closely. "I don't think I'd use it with a makeshift patch like that—if you think it's as dangerous as that. I suppose you had some idea of making a close examination of that pound pippin tree of Duryea's, maybe?"

Kennedy nodded, but kept right on patching.

"My advice would be to leave the thing alone, keep away from it."

"I suppose I might buy a pair of rubber gloves from you?" asked Craig.

Mahoney showed his stock and Craig selected a pair of gloves. "Now if you can find me an empty vial with a wide mouth.... Thank you.

"All right, Sam. Take me back to that tree."

Sam was plainly troubled. "Oh, Mr. Kennedy, look out for dat debbil! Ise afraid, sah!"

Kennedy smiled assuringly, but it seemed as if Sam purposely took a long time to drive us back.

Equipped with mask, gloves and vial as he left us in the flivver in the lane, Kennedy made his way to the dead pound pippin. I saw him closely examining the soil under the tree. There was a hole in the ground and he quickly leaned over, filled the vial with the soil from it, sealed it and started back. I must say I was relieved when he came back and removed the gloves and mask.

"NOW back to the drug store," he directed. "There's an analysis I want to make."

Behind the prescription counter Kennedy set up his temporary laboratory. First he took a flask with a rubber stopper. Through one hole in it was fitted a long funnel; through another ran a glass tube. The tube he connected with a large U-shaped drying tube filled with calcium chloride, which, in turn, he connected with a long open tube with an upturned end.

Into the flask next Craig dropped some pure granulated zinc. Then he covered it with dilute sulphuric acid, poured in through the funnel tube.

"That forms hydrogen gas," he explained to me, "which passes through the drying tube and the ignition tube. Wait until the air is expelled from the tubes."

He lighted a match and touched it to the open, upturned end. The hydrogen, now escaping freely, was ignited with a pale blue flame. A moment later, with a sample of the soil from under the tree, he made a test with one of Mahoney's soil acid indicators. It was very acid. Then he added some of the soil to the mixture in the flask, pouring it in also through the funnel tube.

Almost immediately the pale bluish flame turned to bluish white and white fumes were formed. In the ignition tubes a sort of metallic deposit appeared.

Quickly Craig made one teat after another.

As he did so, I sniffed. There was a unmistakable odor as of garlic in the air.

"What is it?" I asked, mystified.

"Arseniureted hydrogen," he answered, still engaged in verifying his tests. "This is the Marsh test for arsenic."

"Arsenic, eh?" repeated Mahoney.

Kennedy glanced quickly at his face then back at his work.

"There's more than arsenic here," he said quietly. "This confirms my suspicion, gives me a clue."

Mahoney was silent.

Kennedy repeated the process, this time using some of the humor he had wiped from the burns and blisters on the body of the squire. Then he made another test before he seemed satisfied.

Hastily Kennedy composed a telegram and we paused at the local telegraph office long enough for him to get it off to Washington. Then he directed Sam to turn the flivver toward the Duryea place again.

On the driveway at Fourwinds stood a roadster. Doris had come out on the porch and I could see that the owner was condoling with her over her uncle's death. He was a type quite different from most of the local lads—tall, blond, erect, with a charm that most women would feel. Doris was no exception.

"Mr. Kennedy, Mr. Jameson, I would like you to meet Mr. Cushman. Everybody calls him Jake around here."

We shook hands.

"I've been urging Doris, quietly, to go through with the pantomime she has been teaching the children for the harvest home tonight," smiled Jake Cushman. "Poor little girl, she ought to do something to get her mind off this terrible thing. I offered to take her, keep her in the background—but, you know, the children are going to be terribly disappointed if she's not there to direct them through it."

"But, Mr. Kennedy, how can I go to the harvest home? Aunt Mary needs me more than ever—and I feel as if the bottom had dropped out of things."

Kennedy was considering for a moment. "Doris, I know all that. But who is your best friend?"

"Uncle Theodore," she whispered.

"Then for his sake, Doris, I think you ought to go through with all that you would have done for the children's pantomime. They'll be disappointed. I am sure the squire would not want the pantomime given up—and it depends on you."

I began to see Kennedy's purpose. He wanted Doris there so that he could observe the reactions of various people who would attend. It was there that he hoped to find who had killed Squire Duryea.

Her hands moved nervously. "All right—I'll go. You must not make it too difficult for me. But I must see Aunt Mary, see that it is all right, and that someone stays with her "

We entered the house. It was evident that the sympathy of Jake Cushman cheered Mrs. Duryea. When question was broached to her, she answered absently, "If Doris thinks she ought to go then I think it will be best,"

Doris turned. "All right, Jake, do the things for me you promised. Leave the costumes in the church. They are in the school."

"That's fine, Doris. I think that's the spirit." He bowed his way to his car.

"He's a nice young man," was Aunt Mary's comment.

"No nicer than Lionel Tapley and his mother." Doris had risen to the defense of the young minister.

"Perhaps not, Doris." Mrs. Duryea had never been quite so democratic as the squire. She was more exclusive and frankly admitted her social ambitions. "But Lionel Tapley is just a poor struggling country minister. Jake Cushman is a college man, has traveled—and the Cushman farm is a hundred acres."

"I know, Aunt Mary, but Uncle Theodore always liked Lionel. He said he was reliable—and he was a good judge of people."

THE harvest home was an annual event, looked forward to all summer. This year it was later than usual, due to the late ripening of the crops.

Women, some young and rosy, others in the dreaded forties, were flitting about tirelessly. At long rows of tables huge clothes-baskets were being unpacked. Snowy-white tablecloths were being brought out. Great bunches of fall flowers were being placed.

I had never been to a harvest home before. I was hungry and enthralled. What is so heavenly as the odor of roast chicken and ham ascending and mingling with the spicy odor of a pine grove?

Kennedy, Doris and I looked about quietly, apart. The church stood at one end of the inclosure, a simple, stately, white-shingled edifice.

On the other side of the churchyard was the graveyard,with its old tombstones with queer epitaphs among large boxwoods, tall cedars, and, nearest us, the most perfect pine tree I had ever seen.

Doris left us to gather the children together for a final rehearsal.

There was great excitement over by the tables reserved for the prize fruit, vegetables and preserves, and other things. Here the farmers were gathered, debating, arguing and judging the merits of the many splendid exhibits.

Parson Tapley had won out, for the first time, with his pound pippin. Cushman was second and Winslow third. Kennedy and I watched them with interest. It was plainly to be seen that there was discordant feeling over the decision of the judges. Mahoney was openly critical. Cushman was quiet and so was Tapley. It was the only thing for them to do.

It was time for the pantomime. Doris herself represented Mother Ceres, goddess of the harvest, and each little child was a messenger sent out in the spring to plant and later, in the autumn, to garner the harvest. It was cleverly produced and Doris was delighted at the well-earned applause.

KENNEDY was waiting an opportunity to find Tapley alone. "It's great and I congratulate you and your people. I have a little favor to ask. When you make your address, toward the end, don't you think it would be nice to eulogize the squire? Make it tender and sympathetic. He was one of these folks. He loved them." The parson agreed.

The tables had begun to fill rapidly. At first I thought the food could not possibly be consumed, there was so much of it. But when one saw the appetites of the men who had been working in the fields most of the day one's opinion was reversed.

Prom where we sat I could see a little platform. Here the speeches were to be made and the band was to entertain.

The musicians were tuning up with all kinds of squeaks and squawks that elicited much applause and hilarity from the children. It was a pretty sight, the long rows of lights, the beautiful young girls; the flowers and the exhibits, and over all the pine-grove, a stately and benign intermediary with heaven.

Parson Tapley was sitting up with the musicians. Craig had caught sight of two men entering the grounds and had hurried over to them. They were strangers to me. They carried suitcases as if either they had come from a distance or were bringing more supplies or exhibits to the harvest festival. For a moment Craig pointed out all the people and points of interest to them, then left them beside the stately pine that had so impressed me at first.

EVERYBODY sang "America," gave the oath of allegiance to the flag and ended with the "Star-Spangled Banner." There was a prayer by a visiting clergyman, and then Parson Tapley stood forth to speak.

Parson Tapley was a rural preacher, young, gifted with enthusiasm and the rarer gift of making others enthusiastic.

His subject was God's wonderful bounty to us and our selfishness to Him and others about us. It is true he wandered far afield from his subject many times. The continuity of his speech suffered great gaps. But his enthusiastic patriotism was stirring and his faith in the Almighty impressive, and they cheered even when he stopped to take a little drink of water.

During a pause in his talk I saw someone pass a telegram to Kennedy. He read it slowly, thoughtfully, without betraying any idea of its contents.

Parson Tapley suddenly raised his hand reverently. "Neighbors, it seems while so many of us are gathered here the fitting thing to do is to say a few words about our great loss." He paused. "It is a terrible blow to this community, to the stricken wife and the sweet girl he loved so well.

"He expected to be with us. He was going to talk to you people. But do you know I believe he is with us. I feel his presence. How I can visualize him, our kindly squire, great, strong in body, eyes that were so honest and penetrating no crook or coward could face him. They had to kill him treacherously. Friends, I believe that man had served God so long and so well that his murderer will surely be caught.... I would like to be the one to catch him!"

THERE was a murmur at the militancy of the preacher, a human murmur. I heard Doris gasp. It was terrific for her.

"Can't you feel his handclasp, friend? Can't you hear his hearty laugh? Listen! Why, it seems as if I must expect him to walk up to this very "

I saw Kennedy raise his hand.

Parson Tapley could not finish. There was a flash of light, a sudden explosion and dense clouds of smoke from the pine tree.

It was too much for the overwrought nerves of Doris. She faltered, calling "Uncle Theodore!"

There was a flash of light, a sudden explosion. It was

too much for Doris. She faltered, calling "Uncle Theodore!"

In the back, several of the women were in hysterics. Mahoney glared contemptuously at people who were so suggestible.

Kennedy had stepped forward.

"Maybe you know," he began slowly, "that at the time of the Armistice in 1918, American chemists had what was then thought to be the perfect killing gas." He cleared his throat. "There are three qualities that the ideal killing gas must have. First it must be invisible. The early chlorine gas tinged the atmosphere. You could see it coming. There is no surprise in anything you can see.

"Second, a perfect killing gas should be a little heavier than air. It should sink into dugouts and trenches and civilian cellars.

"Third, it should not merely burn. It should poison. It is not enough that it should poison and kill at once if breathed. Gas masks might protect the lungs. But suppose a gas poisoned wherever it settled on the skin, a poison that penetrated the system and in that way brought almost certain death?....

"Such a gas was Lewisite, an elaboration of mustard gas."

Kennedy paused. I have found traces of something like mustard gas at that pound pippin tree. I have found traces of something like Lewisite. But it was neither. It was more. It is an elaboration of both. Since 1918 we have made some progress. Research has given us gases even more deadly—supergases!

"A supergas, a gas fatal to all cell life, not only animal but vegetable, a gas beyond even mustard gas and Lewisite.

"We have come in this supergas near to death-in-the-absolute. This gas goes down, not up. It is heavy and it stays. It strikes terror not merely for armies and navies but for every civilian, man, woman or child, in the remotest spot over which an airplane may fly—everywhere!"

"All right," interrupted Mahoney. "But what about Sam? Why didn't it get him?"

Kennedy turned. "To an extent, some people are naturally immune to some of the poisonous gases. I imagine you know that." He was speaking slowly. "You may know that our army has made systematic examination of susceptibility. There's a resistant class—some 20 per cent of the white men tried, no less than 80 per cent of the negroes. Negroes are pretty well immune to sunburn—and gases. Pigmentation may be the reason. I don't know. Besides, Sam had nearly a day's advantage over the tree and the grass, the bird and the dog."

There came another flash from the foot of the pine tree.

Kennedy turned suddenly.

Cushman stood, dazed, looking ahead without seeing, just staring at the drifting smoke, frozen.

Kennedy slapped him on the back. "What's the matter? Are you gassed?"

Cushman jumped, terrified, as smoke drifted a little nearer in his direction.

"That thing over there under the pine is not mustard gas. It's not the dreadful Lewisite. There's no arsenic in it. It's not the supergas, the improvement on Lewisite. There's no white phosphorus in that smoke. It's not the absolute gas of death! It's just a couple of newspaper photographers up from Philadelphia to take pictures of the people affected by sorrow for the old squire!"

Kennedy had reached into his pocket, pulled out and unfolded the telegram.

"This was a plot to get the squire, who always picked the fruit of that pound pippin himself. Everybody knew that. There was a bomb placed in the earth under that tree so that the moment he stepped on it it would explode."

Kennedy was waving the yellow telegram as he spoke. "You needed capital to develop your hundred acres—and you were sure you would land Doris, with the help of Mrs. Duryea, who liked you and feared young ministers as good providers. The squire penetrated you. He had a high regard for Parson Tapley.... But even the squire didn't know the thing that is in this telegram. I made this inquiry because, from what I found, there was just one place in the country in which this thing could have originated. Read that!"

With bulging eyes the debonair Cushman read the telegram from Washington.

JACOB CUSHMAN DISMISSED JANUARY FOR CAUSE EDGEWOOD ARSENAL. HAND GRENADE OF SUPERGAS NOT ACCOUNTED FOR. NO EVIDENCE YET HE WAS RESPONSIBLE.

"There's evidence now that you are responsible. You are the only man in the world who could have stolen a white phosphorus Lewisite supergas bomb," ground out Kennedy as he signaled a couple of men to seize Cushman, who gazed wildly about for a chance to bolt.

Tapley had come up, and was supporting Doris with his arm.

Kennedy smiled. "Parson, the squire's judgment was correct. You have brought the harvest home!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.