RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Flynn's, 28 Feb 1925, with "Hearing"

"The Fourteen Points," Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1925

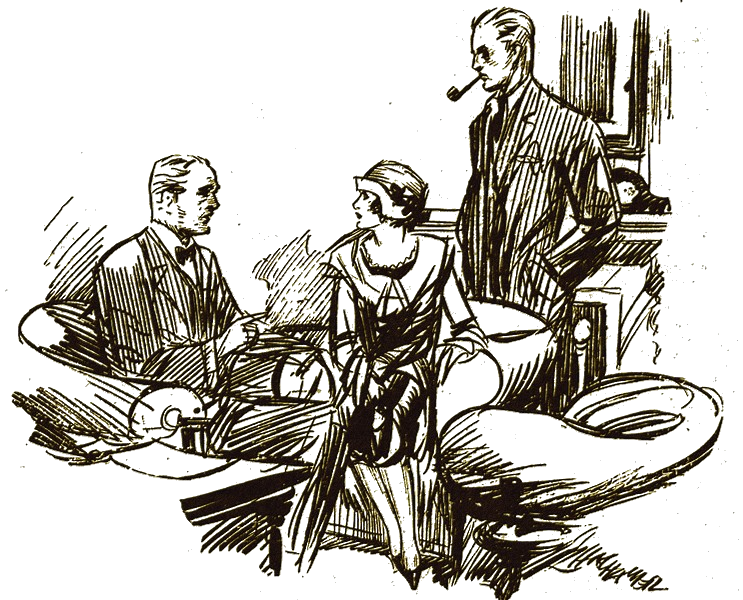

Illustration from "Los Angeles Times Sunday Magazine."

"You think you have been cheated, Miss Neely,

robbed of your share of the Gowdy money?"

"YOU think you have been cheated, Miss Neely, robbed of your share of the Gowdy money?" repeated Kennedy.

"Yes. When they read Uncle Jeremiah Gowdy's will, I found that my cousin, Jim Camp, was made the sole heir. And Uncle Jeremiah hated Jim Camp worse than he bated me—even after his favorite nephew, young Jerry Gowdy, died in France. I don't believe Uncle Jeremiah would have discriminated between Jim Camp and me. He disliked us both—but for different reasons."

"Why?" persisted Kennedy.

"Well, he hated me because I would grow up to be a woman. His life, he said, had been poisoned by a woman, so he hated us all. Jim Camp he called a slacker, a quitter, a coward."

"And of course," nodded Kennedy, "this Jim Camp whom you had never seen showed up to claim the fortune."

"Yes. Strange to say, Jim was at the funeral. He appeared just as silently as they say he once disappeared when he was cut off. Up to that time there was no suspicion by any of us of a new will. At least everyone thought the money would come naturally to Jim and to me, because of Young Jerry's death years ago. But after the funeral the will was read. You can imagine my surprise when I found that everything, even the house in Brooklyn, had been left to Jim Camp. I still can't think it is right."

"Is this will signed?" asked Craig. "Does it look all right?"

"Yes, it seems to be properly signed, and witnessed by Julia Crandall. You see, she was the nurse to Uncle Jeremiah when he died. I suppose they just had her because she happened to be there. The strange part of it is that Jim Camp fell madly in love with her. He gave her a whirlwind campaign, swept her off her feet, and before the week was out they were married. Julia Crandall is good-looking, spick and span, like most nurses. Probably that is one reason why Jim fell for her. I'd never seen Jim before, but he seems so careless of his appearance. I was quite charmed over her at first. She urged me to stay at the house, but I didn't. Now I'm glad I didn't I feel I have a perfect right to half of that money—and I am going to contest the will."

Nan Neely paused. "You see, what makes it difficult for me is that twenty thousand dollars seems so little to most lawyers to fight over—I mean lawyers who are any good. And I have nothing. But ten thousand dollars would go a long way in getting me the right teachers for my voice. Oh, if I only had it!"

The girl might be naïve. But there was nothing scheming or debasing about her. She merely expressed the yearning of an artistic temperament hampered by inexperience and lack of money.

"I can sing," she continued, eagerly. "I know it. But I have had no famous teachers, no chance. I don't want to go in as a chorus girl. Not many of our great artistes have been chorus girls. That seems to make a ragged voice. I want to study, be introduced to the musical world right."

Nan Neely's face might have been a model for divine inspiration. She had grayish-yellow eyes, large and well shaped, lashes black as night sweeping rosy cheeks that showed every evidence of the simple life. No paint was necessary for that blushing hue. A light-brown hair with Titian tints was made glowing from the afternoon sunshine sweeping over it through the window. There was character in her chin and mouth, but life's molding of these features had been determined by a buoyant, happy spirit which had eliminated all that was sad, grim, unlovely. I could see that Craig was favorably impressed with Nan, who was slender with the slenderness of youth, not that of emaciation which so many girls vouch for as style. There was no suggestion of boyishness; rather the delightful suggestion of fascinating womanhood.

"What was your uncle's reason for feeling so bitter toward you all?" retraced Kennedy.

"It's a long story. Perhaps I can tell you briefly. You see there were three of us, two nephews and a niece—young Jerry Gowdy, as everybody called him, who died, Jim Camp, and myself. Uncle Jeremiah always liked Jerry best. In fact, Jerry lived with him. I saw Uncle Jeremiah Gowdy several times, but he never asked me to visit him. He came West some time each year to see my mother. But when she died he lost interest entirely in me."

"What became of young Jerry?" I inquired. "I think you said he died in France."

She nodded. "Yes, he was killed in France, in the second battle of the Marne. Young Jerry was mighty fine most of the time and died making a most self-sacrificing rescue of a buddy who had been wounded. They brought both of the men in, but it was too late. Jerry had lost too much blood, and he died. Uncle Jeremiah never forgave Jim Camp for not entering the army. Young Jerry enlisted before the draft, but Jim Camp evaded the service, proved himself a slacker by taking advantage of some technicality in the draft."

"There was a will then?" inquired Craig.

"At that time the first will had been made. Everything was left to young Jerry, the whole twenty thousand, on condition that Jerry would sign a pledge not to drink. I didn't think anything of that. If Uncle Jeremiah loved young Jerry so much and wanted him to have his money, it was right that he should have it. But there was a decided antipathy, a hatred in his heart, toward Jim Camp. After young Jerry's death the bitterness grew and I know there was never a reconciliation. But here is a new Gowdy will, leaving everything to Jim Camp. I don't believe it is legal. I mean, there is something wrong somewhere.

"When it comes to settling up the estate now, I feel like fighting. I have as much right to my half as Jim has to his. Neither should have it all. And it means my whole future—my happiness."

In her eagerness the girl had leaned forward and her eyes were glowing with the fervor of battle and hope for a musical career.

"How did you come to go to Mr. Jameson on the Star?" inquired Craig.

She thought a moment. "A neighbor of ours out on the Coast was married to man who seemed to be on the level. But she learned the facts. She wanted a divorce. Some one advised her to try her case in the newspapers. It made good story and the papers printed all the facts she gave them. She got her divorce, and at the same time the people were with her. Mr. Kennedy, I decided to do likewise. I am a stranger here in this big city. I thought I could tell my story to the people through the Star and it would help. It has helped, only differently from the way I expected. It led me to Mr. Jameson, and he brought me up here to you for help."

"Where has Jim Camp been all these years?"

"No one knows just where he really has been. But we all know he hasn't been near his uncle, even during his last illness. In fact, as I said, after young Jerry went to France, Uncle Jeremiah publicly disowned Jim. He was just indifferent to me and I was too proud to annoy him by any unwanted attentions. Possibly he may have hated me more, but he kept it to himself. It was as if I'd never lived."

"But what does Jim Camp say he did after he was disinherited?" I could not help interrupting.

"Disappeared. He says he has been out on the Coast part of the time. But he never bothered us in Los Angeles."

"From Los Angeles, eh?" smiled Craig, glancing at her appreciatively. "Why not the movies?"

There was a defiant little flash in those grayish-yellow eyes. "Possibly if you had lived in Los Angeles as I have you wouldn't be such an enthusiast about the movies for a girl. I know girls raised there, as beautiful as any star. But they just simply will not try the movies. Those movie stars may twinkle from afar—but they lack luster among some of us natives of the movie center. I want to sing. I have the voice. And I want to sing—right."

"You say Jeremiah Gowdy hated women?" repeated Craig, thoughtfully.

I could not imagine him hating Nan Neely if he ever had a good look at her and talked to her.

Her answer was so positive that it made Craig chuckle softly with amusement. "Did he hate women? He hated us so much that he wouldn't look at us any more than he could help. Why, I have heard him say the Turks were the only ones who understood women. 'They cover them up, lock them up, watch them. They're all of the devil!"

"Yes; but you say he visited your mother once a year. How did he feel toward her? Not that way, surely."

"N-no. She was his only surviving sister. That was one case where he hadn't allowed his heart to freeze. Until her death he saw her once a year. But he had no use for me, just the same. Mr. Kennedy, don't you think such a violent hatred of all women, good or bad, indicated a weakness, mentally, an incompetency of judgment?" Nan's big eyes were raised directly to Craig's.

Again Kennedy smiled. "A surprising lack of judgment." He paused. "But a broken heart might cause a bitterness so unreasoning that it might amount almost to an insanity. Sometimes, though, it isn't pure hatred, or even bitterness, really—only a mask that some wear through fear, fear of a repetition of blighted hopes and broken dreams."

Nan was silent over that. The romance of the idea stirred her sensitive soul. Perhaps she was thinking for the moment that maybe if she had been a trifle more persistent she might have broken through that wall of icy reserve barricading the way to her uncle's affections.

But there was, on second thought, nothing in her memory of him that even seemed to show it. She remembered and almost cowered again at those malignant glances, the threatening upraised cane if she ever so much as stumbled in his way in her play as a child on his yearly visits to her mother's.

"No, Mr. Kennedy," she said, decisively, "he was crazy over women, in no way competent to make a fair will, even toward one of the sex."

Kennedy said nothing at that. A moment later he resumed. "Are you sure, quite sure, you have told me all you know—or suspect—about this Gowdy will and the persons involved in it?" He eyed her closely. "Isn't there something else?"

Nan seemed to react to it, not as if she were conceal-: ing anything, but as if she were reluctant for some other reason. "Yes," she began, slowly, "there is something. Only I didn't say anything about it because I know how men are, lawyers and detectives and all that. They want facts, not feelings. And I have a—well, a feeling, T guess you'd call it, maybe an intuition. I wouldn't have said anything about it if you hadn't asked the question and looked at me that way."

Kennedy nodded encouragingly. "Let me hear it.. You might as well, now."

Nan was looking absently away. "Oh, it's only this. They say young Jerry and Jim looked a good deal alike. Young Jerry might have been a bit stouter than Jim in the old days, but then he was a couple of years older. Besides, Jim, too, may have taken on weight in more than five-years. I don't know. I never saw anything but their pictures and heard people talk about them. You see, it's this, Mr. Kennedy. If I didn't know young Jerry was dead, how would I ever know Jim Camp when I met him? There's enough alike about them even in the old pictures." She lowered her voice.

"Just what do you mean by that, Nan?" insisted Craig.

"I—I don't know." Her voice was low and there was a sort of tremble in it as if she felt her thoughts were being torn from her without her consent. Then she raised her eyes, decided to make a clean sweep of it. "I'm not a bit sure this is Jim Camp, really.... How do I know it is not—young Jerry?"

"Young Jerry?" Craig straightened up at that.

My mind was alert at it, too, eager to hear more of her feelings in the matter. I sensed in it a mighty sensational story for the Star about mistaken or concealed identities. Instantly its dramatic value loomed greater to me than its probability. My next impulse was to glean from her why she felt it, why there might be even a probability. If she were right, this was a far more interesting story than I had anticipated. That would have a kick in it.

"But, Nan," pursued Kennedy, evenly, "did you notice anything in the actions, the appearance of this Jim Camp to make you think it wasn't Jim Camp, but young Jerry?"

"Not exactly, except the slovenliness. But then that, may have been from the wild roving life he has led in the last few years. Or it may have been a pose. Maybe he isn't really slovenly. Julia Crandall is so—neat. Why did that appeal to Lira if he isn't that way himself? By opposites? I don't know."

"There's something else, isn't there?" asked Craig, with assurance.

"Y-yes. There is. I smelled his breath. He had been drinking the first time I met him. But in the old days, whatever they said about him, Jim Camp never drank. It was young Jerry did that. That was what rankled in the mind of Uncle Jeremiah. His favorite nephew would get drunk. But Jim, for whom he had no use, seemed to have too much sense for it. It was a galling thing to him."

"Does—er—Jim Camp drink since he married?" I asked.

"No. I don't think so. No, I have heard there has been a most wonderful change in Jim since his marriage. He may have learned to be wild and to drink since Uncle Jerry disowned him. But now Julia Crandall has him as docile as a lamb. He seems to think so much of her that he has curbed all that. And young Jerry had that reputation, too. He would go for weeks, leave it alone, then go back."

"H'm!" Kennedy was silent a few minutes as if debating whether to take up the case for the girl or to go on with plans we had had for a vacation. Finally he spoke. "Nan, I'll take up the case for you. If there has been wrong done, I would like to see it made right. And we need good singers."

I was pleased, but could not help putting in my word. "Suppose it is young Jerry. Then you'll lose all, anyhow."

"No, not necessarily. There's this other will. We'll break both, break one on the other, like a couple of sticks. Anyhow, I've lost everything this way. I've got a chance if I can shake either will. None, if I don't. I have everything to gain; nothing to lose."

"Very true," I agreed, still raising questions in my own mind for which I wanted her answers. "But why would young Jerry do it?"

"Oh, there might be reasons. Maybe he didn't want to be known as wild all his life. Maybe he didn't believe he could ever keep the pledge and the money according to the first will. He might have been afraid to lose it. A chance may have come to him, over there. Better to have us think he was dead. He might have recovered, been invalided out of the service. He might have kept in touch in some way with the real Jim Camp. Or Jim Camp might have died. Then he might see a chance to make a come-back, as some one else. Young Jerry might have decided to become Jim Camp, wipe out his black-sheep name with good behaviour under another name."

"And plant a will, forged, somehow?"

"Yes, maybe that. Then the unexpected may have happened—and he has fallen in love with Uncle Jeremiah's nurse. All the more he must make a come-back. Julia Crandall may have reformed him, one of those temporary spells. Maybe she reformed the wrong nephew!"

As I sat back and listened to her, some of the improbability seemed to vanish. It began to seem less chimerical. Why, the whole thing could have taken place, easily. No need even to wonder what had happened to the real Jim Camp who had evaded service. He might have been overcome in the keen struggle in the West, not fighting Indians on the prairies, but Indians of industry and finance.

"Now, Nan, let me tell you what I want you to do," began Kennedy to instruct, thoughtfully. "You have said that Julia Crandall, now your cousin's wife, asked you once to visit or stay in the house with her a short time. Please accept that invitation. It will give me a chance to study this Jim Camp. Humble yourself for your rights. Act as if you thought ten thousand dollars wasn't worth fighting for and you had given up all idea of contesting the will."

The girl nodded. "I can do that. I love to act—act and sing. When shall I begin to be friendly?"

"Right away. Call up Jim Camp. Tell him you have about decided to go back to California in a few days and thought you would like to go back at least good friends with your nearest relatives. Make him think that you have no quarrel now. If you do it right, it will pretty likely bring about an invitation from Julia to visit them. If they ask you, make your stay as agreeable and protracted as possible. It may be that things will break so that it will be short."

Nan's face flushed with eagerness. "If there is anything phony about this Jim Camp, do you think I'll be safe?"

"That, Nan, is what I want to arrange with you. Your cousin must know that you sing. I want you to bring it about so that they'll consent to a musicale, or some quiet evening party for you, before you go, something to speed the parting guest. You must play your cards well."

"But how will a musicale help me to protect myself?" she inquired timidly, puzzled.

"The musicale will not help you. But the sooner you can arrange it, the sooner I can be sure of this new will. It will be a means of my getting in the house to see you. Mr. Jameson and I can pose as musical friends, or some-. thing, in conference with you for the future. To make things seem more plausible you might confide in Julia that you may soon have some good news to tell her. She will suspect only one thing, a romance, and will probably encourage my coming to visit you."

Nan smiled, and a few moments later left us in a great deal happier frame of mind than she had been in when first she was referred to me down at the Star office. At least there was a plan, although she had not the vaguest idea of what Kennedy purposed. Nor did I.

I TRIED to figure out the difficulty over the Gowdy will

myself after Nan Neely's departure. There was no use talking to

Kennedy. He would confide nothing, yet. But to me, as I thought

over what Nan had said, there was something mighty fishy about

this Jim Camp. I had tried so often to solve things in my own way

as a surprise for Kennedy that, in spite of my lack of success, I

was ready to try again. This time I felt I could almost figure it

out already, but I determined at the first opportunity to make

sure before I made Craig in any degree the partner of my

thoughts.

I felt the force of Nan's feeling. Was this really Jim Camp, after all? I had heard Craig ask Nan if she had seen anything different in Jim Camp from what she expected. That must have been his idea, too. But if weren't Jim Camp, who would he be? The most likely thing, then, was that he was the man Jim Camp so closely resembled, young Jerry Gowdy. But it was supposed that young Jerry had been killed in France. At least, as I found out later in the day, there was a little white marker in a cemetery in France with "Jeremiah Gowdy" on it. He couldn't be dead and here, too. Who, then was the unknown soldier? And had young Jerry been willing to let things go so that he could drop out over there, wipe out his past?

The more I looked into it, the more I was convinced that Jim Camp was none other than young Jerry, posing as his own cousin. His drinking had been evidence of his real identity. Rumors of his general lack of manners, his slovenliness, seemed to confirm it. That would be only a cover.

Along in the afternoon Nan called up. "It worked, Mr. Kennedy," she exclaimed in excitement. "When they thought was going back to Los Angeles without causing any trouble for them, their hospitality was amazing. I am leaving my hotel now to go to the Gowdy house. I'll explain your visit right away. You're a friend of mine from back home. I'll let you know when I can have the musicale."

Kennedy went out, but, since he did not ask me to accompany him, I decided he was doing a little sleuthing and took the opportunity to do some on my own. I sought to hunt up the past friends of Jim Camp's in the city, some of the boarding houses he had frequented. I found that there had been such a chap, but that was about all. He had been swallowed up completely. All that people knew was that they had heard he had gone West. I began to wonder what was really the significance, perhaps hidden to them, in "gone West."

THAT evening I found Craig with a number of bundles in our

quarters. He was not disposed to confide what had been his

intentions in his shopping tour, nor did I question him. All I

could think of was what an elusive chap this Jim Camp had been,

evading everybody for years, then seeming to be right on hand the

moment his uncle was dead—not only on hand, but married,

reformed, heir to twenty thousand dollars. It seemed like a fairy

tale to me.

Nan Neely dropped in to see us in the laboratory the next forenoon. She was apparently delighted at her reception at the Gowdy house.

"I'm going to have my party much sooner than I expected," she imparted.

"When?" asked Kennedy.

"To-night. Will you be ready? Good! I find that Julia has social ambitions in a small way and the prospect of this small legacy for Jim paves the way financially for her to indulge them."

"How did you get her to consent to it so soon?"

"Two reasons. I think they want to get rid of me, ship me east of Suez, and by flattery, too. I mentioned that I was going home after I had a chance to say farewell to some friends here. Then after she heard me sing, Julia was ready for the musicale idea. She has suggested only just a few of our most intimate friends. Of course you and Mr. Jameson come under that."

"May I have something to say about the program you arrange for to-night?" queried Craig. "I would advise you to keep the evening decidedly informal. For reasons that I can explain better when I see you there I would suggest a very patriotic program, something pertaining to the World War and the A.E.F."

"Fine!" exclaimed Nan. "When I select my songs I can sing something in the early part of the evening that will satisfy their simple operatic demands, some aria that will indicate the range and quality of my voice, and my ability to keep the tones pure. I want you to hear it, yourself. Then for encores I can sing some of the popular patriotic songs and we'll end up by singing the thing! our boys liked during their stay in France."

"That's splendid. Let gentle hints fall that you intend to make it a patriotic evening, perhaps even that you may have as an intermission to the music some games that you have played before and enjoyed. I can tell you about the games when I get there. You can say you think such an evening would be a nice bit of sentiment for the memory of the hero of the family."

There was vivacity, animation in Nan Neely as she planned with Craig. Her career meant everything to her. Here, she felt, was a legitimate chance to help herself on her way, in some manner to advance toward a fair division of the legacy.

It turned out to be one of those cool, snappy evenings in October when living is a joy. I was glad that weather caused no postponement of the affair. Already I had surmised the kind of thing it was to be—a little music, some better than ordinary, some popular songs, perhaps refreshments of a simple nature, with the surprise act, I hoped, sandwiched in somewhere in some manner. I was curious and a little peeved. I had not been taken wholly into their confidence. I felt that the next time I played the good Samaritan to a pretty girl I would make sure I was not entirely eliminated if I had to have it in writing.

"I have laid your clothes all out for you, Walter," informed Craig as we went up to our apartment after an early dinner. "They're on your bed."

It was said innocently enough, but the act was unusual. "Since when have you been playing valet to me?" I asked, in some doubt whether I was to be laughed at or with. "I deserve it. But it's an unprecedented kindness."

On my bed I discovered a most unusual array of apparel—not a thing that I had expected to find. My evening clothes, everything I usually wore to an entertainment in the evening, were still reposing in closet and drawers. And here was this stuff, this O.D.

"Theirs not to reason why." Since my association with Craig those seemed to be general orders.

Gingerly I picked up these clothes. I knew they were not mine, yet they seemed to be about my size. Here was a captain's uniform and insignia. Had he been rifling one of these Army and Navy stores? Not being quite fully acquainted with the program, I did not hurry dressing. In fact, I had not started when the door opened and Craig walked in—officially.

Could I believe my eyes? Kennedy was saluting me. But somehow it didn't seem just right In fact, nothing seemed just right. Feebly my memory was stirring back to the days when those olive-drab ranks of men went stepping blithely by to entrain for camp or transport. But none of them looked just like Craig. His eyes gleamed with mischief.

"What's the matter? What's wrong with this picture?"

"What's wrong? Why—everything's wrong. It's a patriotic party, I suppose. But those clothes! You think it's a burlesque? You have on a lieutenant's suit, but, great guns! man, you're wearing cuff leggin's with it! Oh, boy! your Sam Browne belt is looped through the wrong shoulder. And when you came in you saluted with the left hand—and such a salute! Say, if a real soldier ever saw you he would give you the bum's rush."

"Never mind me. Get into your own togs. I hope you are right."

Now I began to see Kennedy's strategy. He expected to trap this alleged Jim Camp. If it were really young Jerry Gowdy returned and reformed, he would surely betray his familiarity with the American forces abroad when he surveyed Kennedy. He could not help it. His very amusement and knowledge, even though he said nothing, would amount to a betrayal.

I returned to an inspection of my own clothes with added zest. What was in my prize package? It was not long before I had on my captain's uniform. But with it I was expected to wear a private's cap, and on my arm the service chevrons had been inverted. The only thing I liked about the ensemble was my officer's boots. They made my feet look as nifty as ever.

"Stick me jes' as deep as you want to, but don't fasten that on me," I objected as Craig approached with a bayonet in a case to fasten to my felt. "I'm a captain.'"

"We may need it," he said, merely, going ahead fastening.

"Say, you don't think the party's going to get rough, do you?" I inquired.

"You never can tell. I may need to use it."

WE were a couple of strange gentlemen starting out for an

evening's fun. It was a very good thing, I felt, that we could go

in the car. If we had walked a block under the lights, with all

the ex-service men there were in New York, we would have been

mobbed.

I began to feel a thrill of excitement over the adventure itself, however, as we drove up to the Gowdy house. It was a very old frame-house, the kind one sees often in the older parts of Brooklyn. The boards were laid on vertically and the joinings seemed to be covered with strips of moulding to make them weather-proof. It was two stories high and had no basement. There was a little attic under the gabled roof and an extension seemed to have been added to the rear. A little side entrance led to the rooms in the rear. It was like an ugly duckling among the three-story-and-basement brownstone houses surrounding it.

Evidently Julia was reckless with lighting. Every room seemed lighted. I was glad the street was dark as we parked our car, locked it, and left it some distance up from the house. Craig rang the bell, and I was pleased when the door was opened by Nan herself.

But such a Nan—the sweetest little buddy of them all. She was attired as an ambulance driver and correctly.

"I hope you can sing," she imparted under her voice. "You'll have to help me out with the war songs. Jim says flatly he can't sing and nobody's going to make a fool of him." She glanced skeptically at us as she said it.

There was a suspicion racing through my mind, also. Just why wouldn't Jim Camp sing those songs the boys sang during the war? Was it that he feared to show that he knew them too well? I wondered if that was what Kennedy was thinking, also.

Nan was a lively little hostess. "We're just plain folks here, so make yourselves at home. I'll call Julia and Jim." Then she whispered. "If they seem very curious concerning you, Mr. Kennedy, play the part. I have let them think as they please about us." She impulsively pulled Craig nearer. "My heart is out in Los Angeles. An old friend is waiting for me!"

With a laugh she turned quickly and led us into the living room. "Julia, this is Mr. Kennedy—and Mr. Jameson."

I saw Jim Camp look up at us with interest. He seemed to be observing us both carefully. I held my breath with suspense. Except for the usual acknowledgments in meeting strangers he was decidedly reticent. If he had noticed anything wrong with our uniforms, he carefully kept it to himself. I began to think this man called Jim Camp must really be young Jerry Gowdy and that he was indeed a clever man. He was able to keep his thoughts to himself, and in these days when so many people talk themselves into jails and out of friendships, few are blessed with the cleverness of silence.

Right away Kennedy's attack through the sense of sight had failed, at least so far.

There was nothing very arresting in the appearance of Julia except that she possessed to an unusual extent that practical gentleness acquired in hospital training. To men of a certain type, particularly that exemplified in Jim Camp, a practical yet feeling wife is like an anchor. It holds him safe.

Her hair was dark, much of it, too, and fastened in graceful coils at the back of her head. She had a rather pale face lighted with brilliant dark eyes. Her other features kept her from being handsome. It was easily seen, too, that hers was the stronger will. Jim Camp seemed to feel that doing her bidding was the height of bliss. I watched them as a bachelor with interest and amusement.

Evidently old Jeremiah Gowdy had not believed much in improvements, but had clung to the old things. The room was heated by an old Baltimore heater, antiquated, but still glowing through the little isinglass windows. Over it was a dirty-white marble mantel. There was a nondescript Brussels carpet on the floor and a fancy suit, of furniture, walnut, and overstuffed. The room was lighted dimly by gas, old-fashioned gas, modernized very lately by one Welsbach burner. But Nan seemed at ease. Apparently the inconveniences and incongruities failed to disturb her brightness.

A few other guests, friends of Julia, arrived, and I was glad to note that none of them seemed to have seen service overseas. I knew they hadn't, because they took our uniforms to be bona fide.

Somewhere Nan had found a pianist capable of accompanying her. When all the guests were assembled and chatting perfunctorily, Nan stood before us. "We're going to have a real old-time soldier night for my friends." She nodded toward us. "But not for worlds would I disappoint you about my singing. I am going to sing first the 'Mad Scene' from 'Lucia'; following that, 'Some Day He'll Come' from 'Madame Butterfly.'"

The girl was gracious and simple in her manner and really possessed a wonderful soprano. It needed more training, naturally, but there was the voice, feeling, and charm. Nan Neely had far to go once she started in her profession. No wonder she preferred a conservative, concert platform entrance into the musical world to the uncertain chorus-girl entrance. As the last notes of her second selection died away there was genuine applause. Even Julia conceded it.

Hardly had the enthusiasm subsided politely when Nan was singing with spirit the "Star-spangled Banner." In her uniform, her fervor was contagious, and I felt it as I stood up to join her in spite of my unfamiliarity with the people about me. But Jim held back. Never a note did he sing. At least, if he were young Jerry, he was clever enough not to betray himself through what he saw or what he said. His very aloofness now made me more certain he was the favorite nephew.

Nan was undiscouraged. She looked up brightly. "Let's have a good old-fashioned sing. Just the songs we all know."

She began with "Pack up your troubles in your old kit bag, and smile, smile, smile." Then she started, "Oh, how I hate to get up in the morning."

Everybody joined in and enjoyed it with the exception of Jim. Most of the time he was silent. At other times his lips were merely moving mechanically in the familiar choruses. It was the same with "Over there" and "Where do we go from here." Not a sound escaped his lips. Nan concluded for the moment with, "Hail, hail, the gang's all here."

I was watching Jim Camp closely now. He seemed tired. Sometimes his eyes were closed. I wondered what was the matter. I was surprised that Kennedy did not keep a closer watch and I wondered if covertly he saw what I saw. The man looked to me as if the old songs had sent him browsing back in memory's fields. Was he living over again the dangers, the thrills, and the hardships of the war? I was sure of it and felt a little sorry for him. But, then, why wasn't the man on the level? I began to think that the singing was not working any better than our appeal to his sense of sight in our outrageous uniforms.

In a pause, Kennedy pulled from his pocket a packet of French cigarettes that were smoked a great deal over there by our boys when they couldn't get the American brands that the war made famous. I hadn't smoked one for a long time, but I recognised the aroma of them the moment I took the first puff after Kennedy had offered them around.

Jim Camp took one lazily, only looking at it with mild curiosity. He lighted it casually and began smoking. Now I was interested. Common as these cigarettes were in France, they were uncommon here. In fact, Craig had had to get them from an importer on Broadway.

Jim Camp smoked that fag with about the same amount of appreciation as if it had been cornsilk. In fact, no one seemed to comment on them, not even Julia when she calmly helped herself to one. I could imagine that the others set it down merely as a vagary of Craig's taste. But at least I would have expected Jim to pull out a "Fat" or a "Camel" when he finished. He did nothing of the sort; in fact, nothing. Smell didn't work, either.

So far, with each test, there had been no response, nothing apparently to excite recollection of the service. Yet I was still unconvinced that this was Jim Camp himself. He was certainly acting just as young Jerry Gowdy would have acted, I believed, under the same circumstances. I had a feeling, comparable to Nan's now, that this Jim Camp was posing, trying to make us believe that he was never over there, whereas, according to my idea, he was in reality a sort of reverse on Enoch Arden—had come back and married a girl as another man.

A moment later Julia asked us into the dining room. There the table was spread with sandwiches and cakes. There was coffee. It was, after all, just an old-fashioned party.

"I know what to do," exclaimed Nan, catching a glance from Kennedy. "You men look lost. I can tell what is the matter. You need a little—smile."

Upstairs she ran, and a moment later returned with what I recognized as one of the packages Kennedy had sent to the apartment. As she unwrapped it I saw that it was a bottle of wine. But as she poured she carefully kept the label covered still.

"Now I want you to guess what this is," she cried. "It was given to me. I'll give you each a guess with your glass."

Some guessed port, others claret. In fact the crowd was banal. They showed how bootleggers can victimize the American public, selling them anything.

As a matter of fact, it was a light French wine used by the boys over there and very well liked in the many places where the drinking water was so impure that the drinking of this light French wine was almost a necessity. Kennedy guessed it right, but only after I had said I did not know and Jim Camp had hazarded that it was home-made elderberry.

There was amusement among them at that. But to me it showed merely that Jim Camp had exhibited another case of unusual ignorance for him. Either he was extremely cunning or an incredible boob. I was satisfied that my first surmise was correct. It looked almost to me as if he were going so far in his efforts to know nothing and to make mistakes, that he was ridiculous, no matter which man he was.

Well, I thought to myself, taste doesn't work, either.

"Maybe you don't care for that there French wine," now volunteered Jim. My hopes rose at his taking the initiative and doing anything at all—more especially this, as he added, opening the lower sideboard, "Perhaps you'd like a—an orange blossom?" He gave a hesitant glance at his wife as we descried a bottle of gin in the dark recesses under the sideboard.

Julia unbent. "There are plenty of oranges in that dish."

Jim opened a drawer and began fumbling for a sharp knife as Julia produced a large jar and a strainer for the juice. He tried one or two knives, laid them back as too dull.

"What's that, a knife you want?" cut in Kennedy. "I can't oblige you exactly, but try this." Craig had reached over and slipped the steel bayonet from the case on my belt and passed it to Jim Camp.

"Thanks." Camp took the pointed metal ordinarily effective for thrusting with force back of it, but entirely useless as far as cutting an orange is concerned. He took it without comment, too. His face was absolutely innocent of guile, it seemed, as with apparent good faith in Craig's offer he tried to cut the orange.

"It's quite dull, Mr. Kennedy." He held the bayonet up and felt along its edge lightly with his thumb. "You'd oughter get it ground!"

Craig looked at the man sharply, but his eyes never flickered. Yet Kennedy himself had taken that bayonet and sharpened the edge a bit to make it a cutting edge. There was nothing wrong about that to this Jim Camp—except that it was not sharp enough! If he knew that bayonets depended on thrust, not a razor-like edge for their efficiency, he never showed it.

Each one of these more or less silent little dramas that Craig was staging with the able assistance of Nan to make Jim Camp reveal himself was mighty interesting to me. To me each confirmed my idea that the man was really young Jerry Gowdy playing a game. No one could be so absolutely stupid as this man pretended.

Nan relieved the situation by getting a knife from the kitchen and finished by squeezing the oranges while Jim fixed up the "orange blossoms" with what seemed to me a practiced hand, and thereby, also, betrayed something.

Touch, too, had failed. So, I thought Craig had been going through all the senses in the hope of getting something on this Jim Camp. To me it looked equally as if Jim Camp were using every sense he possessed to defend himself against Kennedy. I was actually wondering what was becoming of Kennedy's theory of the senses and crime. I was thinking that if he were going positively to identify this man he didn't have many more senses left with which to experiment.

I caught sight of Craig in a quiet talk with Nan, and for precaution I engaged Jim and Julia in conversation. Out of the corner of my eye, from the animation of Nan's face, I could tell that Kennedy was framing the plans for some further test. He had been virtually defeated so far. The guests were dispersing now, about midnight, and I wondered what next he would do.

As he said good-night to Nan, there was a little searching glance that passed between them which might be taken for many things—an understanding look between lovers or a significant exchange of signals between conspirators. I knew which it was.

"Is it a failure—or just a mystery?" I asked as we climbed into the car.

"It's still a mystery, Walter." He seemed in no hurry as we drove along, almost purposeless. "I'm just dropping back to the laboratory for a small package. Then, about two in the morning, when all is quiet, I am coming back to the Gowdy house. I have left your bayonet there purposely. Nan is going to let us in without their knowing. If anything goes wrong the old bayonet will be as good an excuse as we can find. You must go with me. I may need help."

"Surely. If it's really young Jerry, he'll likely be able to shoot."

WE rode over to the city, uptown, and back, leisurely,

avoiding the night life in these opéra bouffe togs.

At last we were again approaching the Gowdy house. That part of Brooklyn was a quiet place in the middle of the night. There were few people travelling and everything we did seemed so conspicuous and noisy. Changing gears and jamming brakes sounded twice as loud as in the daytime.

Again we left the car a short distance from the house. That precaution had not been really necessary during our earlier visit, but neither of us knew just how this second visit would turn out.

Evidently Nan had been looking for us. As we walked quietly up the low stoop the front door opened noiselessly. We could just glimpse Nan's face peering at us, white and scared, in the doorway. Her finger was on her lips, adjuring silence.

"They sleep in the front room," she whispered. "My room is in the rear. Another room is between us and probably you can hide there. There's a queer arrangement in the front and middle rooms—a space between them which is divided by sliding doors. When they're closed, it makes two private bedrooms. No one is in the middle room now. Sometimes when Jim takes a notion to snore, Julia gets up in the night and leaves that room to sleep in the middle room. But no change has been made yet to-night. Jim's nose seems to be behaving." Nan laughed impishly, quite like any youngster appreciating the humor to be had from a loud snorer.

How we ever trod on those old stairs without giving the whole thing away is beyond my explanation. We had both our weight and the creaking old boards to contend with. I breathed a sigh of relief as I made out the opened door of the middle room from the hall. It was Unlighted and I slid into the dark room gratefully. I had no relish to be taken for a burglar in another man's house. I wanted to be where there was a window, some exit. Craig was right after me, and Nan followed.

"Did you unfasten the sliding doors?" whispered Craig.

"Yes; when they were still downstairs to-night after you left. I don't believe they would notice that the key had been turned. I heard Julia say she was so tired she was going right to sleep. Jim seemed just as dull."

"And you have the things ready I asked you?"

"Yes. They're under the bed. I couldn't find a fiat piece of iron. But I got a dishpan and an iron fork. Will that be all right?"

Kennedy nodded.

"It's the best I could do." I could see that Nan was actually trembling over the prospects of the next step.

For the first time now, under Craig's flashlight, I saw that he had brought down from the laboratory a little hand-siren that we had once had on a small motor boat. It was a simple enough thing to look at—but why in the name of sense bring a noise-maker like that when we were trying so hard to execute a silent house entry?

"What's the idea?" I whispered.

There was no answer at first. Had Kennedy thought of the neighbors? Had he considered the results of this tomfoolery? What was he to gain, anyway?

"Don't worry, Walter," he returned at length. "Nothing much can happen to us. I'm provided with a warrant. And I'm rather known at police headquarters." I smiled at the ironic answer.

Quietly he was preparing—something. Gently the sliding doors were opened, wide enough for us to get a glimpse of the sleepers in the waving street light, into the front room. Jim was not snoring yet. Julia had both eyes closed in a deep slumber.

Carefully Craig looked all about to be sure everything was ready as he wanted it. Then he signalled to step back into the shadow of the middle room.

He took the siren, muffled it in the folds of a bath towel from the rack. Nan did the same with hand towels partly over both dishpan and iron fork.

"Are you ready?"

"Yes!"

He turned the siren handle briskly. Muffled, it sounded the signal of danger. It moaned, rising ever higher to a crescendo of alarm, then falling, as of a motor boat or car coming.

Nan with the pan and fork also muffled had set up a resonant clatter.

I did not need to ask as I listened and looked at the three of us crouching in the darkness. I saw it now. It was brought back to me as yesterday. Just as the men in France would set up such an unearthly racket with sirens, tin pans, old iron, anything that would ring, vibrate, so were Craig and Nan arousing the stillness of the night. Over in France it could mean only one thing: "Gas! Put on your gas masks!"

The best part of Craig's serenade was its suddenness, the muffled clamor—the just as startling silence that followed—and complete darkness. I saw it all, the psychic preparation of the evening, then this shock to the unconscious mind, an actual taking advantage, turning to account of failure.

Was that a sound we heard in the front bedroom? Over each other's shoulders we peered. Some one was moving silently about, groping timidly, uncertain. Some one else was regularly breathing in sleep.

Whoever was moving so slowly was going toward the other door, the hall door in the front bedroom. Kennedy made sure his flashlight was still working and handy. The breathing continued, a little louder, perhaps, as if the person had been disturbed and in the disturbance had assumed a position difficult for respiration.

Breathlessly we tiptoed into the hall and stood by the other door.

The door knob rattled weakly, futilely, uncertain. Another effort brought no better result. Kennedy quickly flung the door wide open. There was the dim outline of the sleepwalker, as it were.

For just a fraction of a second, shaded, he swung the flashlight.

It was Julia Crandall!

She was not awake, by any means. Her face depicted terror, horror. One hand she held over her mouth and nostrils as if to shut off something, the other over her eyes. What did this apparition mean? We weren't after Julia Crandall. We were after Jim Camp!

"What's it mean, Craig?" I half whispered.

Kennedy motioned silence. We watched him go forward to her.

"You've been in these gas attacks before, nurse?" Softly, subtly his voice sounded. "This is my first!"

"Yes... many times.... Oh! I know them!" Julia murmured, hoarsely. Her voice sounded in guttural tones. She was not herself. Her hands now were fluttering aimlessly. "The gas mask, lieutenant, where is it?"

"Over here."

"Oh, it's awful these days up here in the receiving station, so near the front! We're always fighting the gas. Please—please get me my mask! Where is it?... It's frightful, all these wounded, suffering boys—and then those fellows gassed—dying! Hear them? Haven't they gone through enough—without this?"

"Let's get out of it now! Come this way. The masks... over here!" Kennedy had been thinking quick. "Did that Gowdy chap die yet?"

"Yes." A shiver. "He was telling me about leaving an uncle and two cousins back in the States. He'd been the heir in the will, supposes now that his cousins Jim and Nan will get his uncle's money. Oh, he said everything so cooly I could hardly realize he'd been wounded beyond help. Yes, his strength finally ebbed—and he died." There was another shudder. "Oh, get me my mask, before it is too late." She was clutching her throat. "I feel almost suffocating!"

In the darkness, listening to the terrified girl, I was piecing it together now by sheer logic. This whole experience had been so vivid in her memory ever since, was so indelibly associated with the sound of the siren, that when she heard it in her sleep she was living it all over again.

The semi-conscious girl seemed reassured for the instant, took a step with Kennedy.

Like a flash it filtered into my mind. She had been gassed, too, the night Jerry Gowdy died. That was why she was so frightened now. I imagined that when she was lying sick and helpless she had made up her mind to meet Jim Camp. When she got well she had gone back to nursing privately, had looked up old Jeremiah Gowdy, found he was ill, needed a nurse. Old Gowdy was dying. He was easy in her hands. But she had had to work quickly. She had found the will, copied it, changed the name, got him to sign it, Perhaps he never, knew what it was. Then she had made a grand hunt by telegraph for Jim Camp, and had located him. She hadn't wanted the girl to cut in. But Nan had heard, too. Julia had played Jim Camp, made him fall father, married him.

"Oh, where are those masks? I'm choking!"

There was only a snore from the front room. Jim was sleeping throughout it all. It meant nothing to Jim.

"Then—it's Julia—not Jim!" Nan was whispering. "He hasn't reacted to the call, at all, It's the nurse!"

Kennedy bent over, nodded to Nan. By his manner I knew that he had made an instantaneous revision of judgment, that he had been as surprised as we. The nurse had responded, not Camp. Yet I could not help wondering if be had unconsciously felt just an inkling of something like this before. He seemed so prepared for the emergency. He was like a good football player, ready to take advantage of a fumble, any break in the game.

"Yes," he muttered. "When you set a trap you don't always know just what game you'll catch—but if you're a good trapper you'll catch something you want!"

"Where am I?" Julia had opened her eyes wide, staring in surprise and fear. "What was that noise?" She was now thoroughly awake and angry.

Kennedy took her arm now, not quite gently. "That noise. It was the gas alarm you heard in your sleep. Sight, smell, touch, taste failed—but hearing has given Nan Neely her case to contest the will!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.