RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Flynn's, 7 Feb 1925, with "Smell"

"The Fourteen Points," Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1925

Illustration from "Los Angeles Times Sunday Magazine."

He bowed, leaned over and whispered some message to Kennedy.

"EVERY crime depends for its solution on one of the five senses—touch, taste, sight, feeling, or smell."

Craig Kennedy, tall and spare, leaned back in the big leather club chair, with an indolent smile on his lips. No one at that moment would have thought that his active mind was engrossed on an unusually gruesome murder mystery.

Yet I knew that he had spent many hours on a case for the prohibition director and that now, for relief, he had asked me to meet him in the exclusive All Night Club which carried on its roster some of the keenest men in the big city, men of high standing in the financial world, internationally famous artists, writers, and playwrights.

No vacuous mediocrity ever gained entrance to that huge lounging room. To be a habitué of the All Night Club meant that one must have appealed as a mighty fine fellow to practically the entire membership list. This was a club where the name of a new member was not decided on by any committee of three or five. It must be unanimously approved.

Craig had been asked to join some months ago, and to his reflected glory I felt I owed my admittance. It was a good thing for us. It meant a convenient place for us to meet any hour of the night, centrally located, and if one cared for the society of others, there was always some congenial soul hanging about the place.

Planned by one of the best known architects, built under conditions fostered by wealth and brains, there was nothing lacking so far as beauty and comfort were concerned. The rooms were large and lofty, furnished simply with the things that men know other men need and like, and not with the things a feminized world thinks men ought to like and need.

Kennedy was a popular member. To many, his startling, unusual profession gave a kick after the grueling competitive stress of the day's work. There was always a crowd near Kennedy, and this night was no different from others.

It had been a hot day. Many of the men were temporary bachelors, detained in the city by business responsibilities while their families were away. Among them were faces I saw frequently in the Star—people who were doing things of interest in the world. There was Chalmers Chandler, the famous playwright who had made a half million in royalties from his latest play; Larry Halpin, the middle-aged importer, reputed wealthy, retired, but whose activities in the way of pleasure drove him all over the country. There was Clarke, the banker and broker, whose fortune was long, but mercy scant when he had the market rigged right. There were others, a never-ending succession of them, coming and going. It was the uncertainty and surprise at the appearance of prominent men which was the chief charm of the club.

It had not been long with our little group of four or five in a corner before the discussion turned to crime and its detection. There is just enough devil in all of us to like to listen to such tales. The news of the world is, therefore, full of crime, because crime interests human beings.

"Oh, I say, Kennedy, you can't mean that!" There was good-natured raillery in his laugh as young Hewitt stood up, smoothed his fine mop of blond hair thoughtfully, and took a step or two nearer from the chair where he had been sitting apart. "No, Kennedy. That stuff about the five senses will not go here, with us. Now, for example, that Cronk case, which I understand you are interested in, dismisses that statement as too broad."

Craig half turned intently on Hewitt. He had been left half a million and had run it up to four times that in a couple of years. Hewitt was not one to be disregarded. His was an unusual grasp of the practical things of life and he merited the attention the older men of the club gave him at times.

"I am willing to wager with any of you," persisted Kennedy, "that when the Cronk case is solved it will be found that one of the senses is at the bottom of it."

"Now, Kennedy, when it comes to vision, for instance, most of us have seen something that wasn't just on the level. But that is hardly what could be called detection through one of the senses. It is sight, of course. But that's too broad, too obvious. We'd do nothing at all if we didn't have eyes and ears, tongues, noses, hands and feet, and so on." It was Larry Halpin who spoke. Larry wan a popular man about town and the club.

"You're right, Larry, as far as you go. What most of us think we see is only half, or less. We supply a good deal mentally for many a thing we see. Probably we give to deeds the impelling thoughts that would have prompted us to commit the same acts. We don't see straight. Very few do. That is the trouble with so much of our direct testimony. If I were on a jury and a man's life depended on such direct evidence alone, I would hold out for a long time. The right kind of circumstantial evidence is the best evidence."

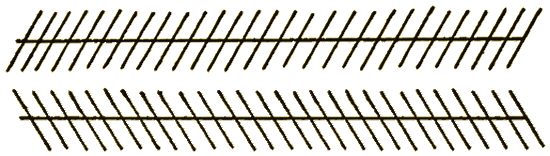

Kennedy had been drawing with a pencil on a piece of paper, two lines, with flanges of arrows at each end, turned inward on one line, outward on the other:

"Which is the longer line?" he asked.

"Why, this one, of course." Larry had put his finger on the line with the arrow heads turned inward.

Kennedy laughed. "Each line is exactly an inch. It's the arrow heads fool the eye. Now how far off, about, will these two lines meet?"

He had drawn two lines, one intersected by a series of short cross lines on a right-hand diagonal, the other with a diagonal to the left:

"About out here," indicated Hewitt on the table top.

Kennedy laughed again. "Never—unless you are one of the twelve men in the world who understand the Einstein theory and know where parallel lines meet. These lines are parallel. It's the cross lines fool you. So you don't want to be too sure of even your senses in this Cronk case, either. Maybe the cross lines will fool you!"

A deep booming laugh from Chalmers Chandler. He was a lovable type, cultured, a traveler all over the world, well read, observing. His plays were popular because they hurt no one, but appealed to the ideals of struggling humans. "Isn't that the case of Hinman's chauffeur you're talking about?" he asked as he sauntered across the floor.

"Yes. The papers are full of it," I explained. "It's mighty queer because there seem to be no clues. The police don't seem to have a thing, yet If they have, they're mighty reticent."

"Well, who did it, do you think? Hijackers? That is my impression," added Chandler. "How does that strike you, Kennedy? Don't you think these hijackers are responsible for most of the bootleg crimes nowadays?"

"Chalmers, I haven't figured that out, about hijackers, yet. But I think I'm on the way. When I find out, I'll tell."

"You can't pump anything out of Kennedy that way," I cautioned. "He'll talk when he gets something to talk about. Why, he refuses even to discuss this case with me. Usually he takes me into his confidence, at least to a degree. So far he has seemed to me to avoid it in this case. I'd like the story. So would the Star. Yet here we are at the club having this ridiculous argument. It's all interesting, and all that I don't mean ridiculous in that sense. But I would prefer, when there is some one to catch, to be out catching him."

It may have sounded a little more pointed than I had intended. However, Kennedy took it in good part, smiled again. "Very well. Why not do it? You have all your five senses—the compleat angler for criminals. Go to it. I'm sure the director would thank you."

The laugh was on me. "You're invited to try out some of those five senses, I take it, Jameson," laughed Larry Halpin, provokingly.

I subsided. Kennedy's offer was one that is always calculated to floor a critic in a mystery case.

Chandler was leaning back in an introspective attitude. Passing his hand slowly over his face, he remarked, thoughtfully, "It's drama—this Cronk case. There's drama in it, somewhere. Some one is going to make a name for himself with a hijacker drama. I would like to do it."

"The great American drama," added Hewitt, mischievously. "Hijackers vs. Bootleggers. Quite American, I'd say."

"What are the facts of the case—and what case is it?" A newcomer had joined us. It was General Tarns, whose reminiscences of two wars were the delight of the club.

"Why, this Cronk case," I took it upon myself to answer.

"What did he do? I haven't heard a thing about it. My boat just docked to-day. It must be interesting or you fellows wouldn't all be discussing it."

"It is interesting," returned Chandler. "At least, we're interested. Cronk was Hinman's—Percy Hinman's—chauffeur, and Kennedy had just informed us that every crime depends on one of the five senses for its solution. I should think that was enough to get us interested."

"Well," drawled the general, "it seems to me a great many crimes could be brought under the sense of touch. I have been touched so often that it's a crime. What did this Cronk do?"

"That's just it, General. We don't know just what he did. He seemed such a harmless, inoffensive sort of fellow, attended to his own affairs, apparently had no enemies. It wasn't what he did. It was what others did."

Kennedy nodded tolerantly at my assumption of knowing anything about the case. Again I subsided, determined to let the others do the telling, instructing Tarns.

"But what was it and when did they find out about it?" insisted the general with some asperity.

"Last night they found Hinman's car, a big blue Packard sedan, upholstered in whipcord, abandoned on a lonely Long Island road down Smithtown way. It was empty, too. But from what we hear, it couldn't have been empty when Cronk started out with it."

"No, it was not, Chandler. It had some of that one thousand cases unloaded at Nissequogue from that German tanker that steamed up Long Island sound last Saturday night, lightering off stuff by appointment at various places all along the shore."

"Now, Kennedy," bantered Chandler, "there might be something to your theory as to taste. Suppose there's some poor devil hasn't had a taste of anything for a long time, dry as a camel's tonsils. There might have been a crime committed."

"Yes, I was talking this evening to one of the Hinman girls—Gladys," informed young Hewitt. "They feel terribly about the whole affair. In spite of the notoriety it will bring them, though, they have acknowledged frankly the ownership of the stolen contraband stuff. They are going to make a fight to bring the criminal to justice. Gladys says her father feels responsible in a way for Crook. If he hadn't sent Cronk out for the stuff, she says, it wouldn't have happened."

"But," suggested Tarns, feeling out the facts of the case, "Cronk might have stolen the stuff, sold out his boss, Hinman, fled with a pocketful of money by this time."

"They found his body!" Kennedy cut in, slowly.

"Where? Near the car, as if there had been a fight? Was the car out of commission, too?"

"No; nothing as simple as that," I intervened. "They found his body in the cellar of the old fish-glue factory down there, along the road, not so very far away. He must have been murdered before he was taken there."

"Hijackers, I tell you, General," reiterated Chandler. "Don't you say? Nothing under the sun but those criminals. Picture that poor devil of a driver shooting along the dark road with the stuff piled in the back of the sedan, probably scared to death, scared at the possible appearance of revenuers, more scared of the very men who got him." Chandler was peering backward in thought, trying imaginatively to fill out the gaps.

"All right, Chandler, but will you tell me how the case of that poor chauffeur of the blue sedan full of rare wines and liqueurs smuggled in, who was killed on a lonely Long Island road and whose body was hidden, has anything to do with the senses, any more than with the circulation of blood?" It was Timothy Dodd, an old recluse as far as anything involving the ladies was concerned, but upon whom many men's clubs depended for his generosity of support. His was a mixture of sound reasoning and curious hobbies.

I nodded in accord with him this once. I was a little put out at what had seemed to me Kennedy's dilatory and lackadaisical method about this murder. Once or twice I had suspected he was getting tired of hunting criminals in the hot weather. Besides, I was jealous for his reputation in the hands of these keen kidders of the club. And always before, an unusual mystery like this would get under his skin. He would never seem to rest until it was solved. Why should he lie down now?

"That's it—a fact, not a theory," I chimed in. "Some one killed Cronk and hid his body in that place, of all places, apparently just because it was most convenient."

"You don't suppose, putting a little horse sense into this mystery," queried Timothy Dodd, "that anyone from that German tanker, knowing the value, could have stolen back the goods?"

"Not likely," I considered. "The stuff was delivered to some Italian bootleggers working in harmony with the tanker on shore. There were five of them. Their headquarters for the time were in an old deserted bungalow down close to the beach. That's where Cronk was to pick up the stuff for Hinman, and did."

I was busy building up a story as pretty as if I had been writing it. "Now suppose one of them had a hand in it. They'd have driven off the car, most likely. As it was, they might have gone on undiscovered, except for the attention called by this abandoned car, if a motorcycle state trooper on duty out near Smithtown hadn't seen a high-powered motor car speed into the main road from a little-traveled side road, after he had been called in on the case. His suspicions were aroused and he decided to investigate the few shacks along the beach near the end of that road. You know reports of rum running soon spread. Those who hate liquor hate so intensely that their ears are always open, and those who love it and have the money—well, I needn't say anything more. They say enough."

"I see. Ears and tongues!" exclaimed Hewitt. "Is that what you're driving at? What about Kennedy's theory and taste, though? From all accounts of this choice collection of wines and cordials, it must have been extra fine, worth a king's ransom, to have so many people after it. Some sense they displayed, in a way, after all, then!" Hewitt's sally was greeted with a laugh.

"That's right about rumor," agreed Kennedy, thoughtfully. "The gossip was that many bottles of fine wines and cordials had been taken ashore at Nissequogue from this German boat, along with a thousand or more cases of other, common, stuff, stored in one of those shacks. The revenuers got a tip from the gossip, whatever the motorcycle man may or may not have suspected."

"Yes," agreed Larry Halpin. "I heard something about that raid along the beach, too. They got the men, all right. And I, for one, wouldn't be surprised to hear that the same men who acted to deliver to Cronk his carload, as agents, were the ones who followed him up and got it away from him again as hijackers."

Kennedy nodded politely, then went on with the facts. "When they organized the raid on the shacks, there were six men, all told—two revenuers, two state troopers, and two special county officers. When they approached the beach they saw five men sitting on a sand pile in front of the suspected shack. In all they got over a hundred cases of stuff that hadn't yet been removed. But not a smell of the choice wines and cordials from France and Italy and Spain. If they had had a thousand cases in addition to that stuff of Hinman's, they must have been working fast to move all but a hundred cases before the following forenoon, down there."

"Did they put up much of a fight?" asked Chandler, always with a sense for the melodramatic.

"No. The raiders didn't give them a chance," returned Craig. "One of the men pulled a gat, but the troopers were expecting that and winged him in the forearm. He dropped it and they closed in. They got this chap so suddenly it took the breath away from the others. I don't believe they knew whether they were captured or surrendered. They've been questioned at Riverhead, but have shut up like clams."

"Is that the whole gang or just a part of it, do you think?" inquired Tarns.

Kennedy shrugged. "I believe there are a couple of Eagle boats cruising up and down the Sound now. But they haven't got the tanker, yet. Also they've tripled the number of revenue men on shore. It's hard to tell whether it will do much good. They just move from the south shore to the north shore of the island. You've got to keep the boats away from both shores."

"I see," nodded Chandler, always coining phrases. "Rum-runners and hijackers are the root of all evil."

"The thing that seems so ridiculous to me," I put in, "is where the murderer or the murderers hid the body. It seems to me that that old fish-glue factory was about as poor a place as they could have selected. There were much better places that were passed up. A hundred yards nearer, and away in from the road, is an old clay pit. There's a pool of water now at the bottom of the clay pit. The body could have been dropped in and would likely never have been found. Occasionally the glue factory is used and it just happened that they had determined to open it up the day after poor Cronk was dragged there and thrown in the cellar. But that old clay pit, and the kiln, even, further along a few feet from the glue factory, either would have been a safer place to hide a body. Then it would have been just a case of an abandoned car found on a road."

By this time the earnest voices in our comer of the lounge were arousing curiosity, to say nothing of the personnel of the party. Besides, General Tarns was back. Previous to prohibition, like many of the other members of the club, Tarns stocked up his locker in his room for the future dry spell. Our legal talent had worked out a way for the All Night Club to be a legitimate oasis. There was no lawbreaking, but occasionally the corks popped in spite of the Eighteenth Amendment.

Men came straggling over to our comer to join us, and when one fellow left, there was always another to take his place, perhaps two. Secretly, too, I knew these men would have liked nothing better than to make Kennedy out a theorist. I think men look at the detective profession much as women look on the stage and spiritualism. With very few exceptions, women think they would have made either great actresses or great mediums, if they had had half a chance. Every man feels he could give the greatest detective points if he would only take the trouble to get down to it. Here was a chance to get down to it.

"I'll tell you what we can do," breezed Chandler. "Theoretically we'll solve this case, sitting right here in the club. We can put our wits to work—not our senses. What about it, Kennedy? Then when we have it all logically constructed, I'll dress it up, put the old hokum in it, shove in the gags, and we've got a Broadway success!"

I never knew whether to take Chandler seriously or not, He was standing, with a sort of dramatic flourish, as he spoke: "Now, gentlemen, you are looking at a play similar to the 'Yellow Jacket,' a few years back. Your own imagination must do the work. Six club members in search of a plot, or something. There sits a fine-looking detective." He bowed deeply to Kennedy with the mock dignity of an announcer. "And his newspaper friend." He bowed toward me. "Murder, a fiendish, horrible, brutal murder has been committed. A man's body has been found in a fish-glue factory, some yards up the road from a blue Packard sedan, empty, empty as a hijacker's heart. Just visualize it. Where would you start?"

There was a pause. "You might have the senses come on the stage, Chalmers, one by one; make it allegorical," suggested Larry Halpin, maintaining an utterly serious face, to the amusement of the others. "Put every sense on the witness stand—or perhaps in the prisoner's dock. Bring 'cm on, handcuffed; try 'em, convict 'em, sentence 'cm, hang 'em!"

"No, no, Larry. Don't make a joke out of it," interposed Clarke. "I'm for good old deduction. Where would a detective be if he forgot and left his deduction locked up in the vault until morning with a time lock on it? That chauffeur's car was full of good cheer. Its selling price is high. What is more natural than to deduce that we must look for some one dispensing cheer? Look in the social register, go over the list of our friends, many of them living on Long Island, see what names haven't been giving parties lately, but have just sent out invitations. There's your man! Deduct! Find out where the cheer was needed. There you will find the murderer!"

"By jingo! I sent out invitations to a clam bake next week," exclaimed Hewitt. "Where'll I get my alibi? I'll have to hold you up, Clarke, and hijack one from you!"

"No, Clarke," cut in Dodd, "it's not who's going to give parties. It's who has been giving them. Whose cellar is depleted, must be stocked up, at any cost?"

"Exit plot number one," returned Kennedy, quietly. "Clarke, your deduction theory is non-alcoholic. It won't hold water. It is water."

Hewitt broke into the discussion again. "Do it by scientific evidence. This detective is a scientist. Science works better than the senses."

"I haven't said the senses were in conflict with science," amplified Kennedy.

"Gentlemen, catch a criminal for Chalmers," remonstrated Halpin. "Do it spectacularly. He wants to make another fortune. Make it a one-act play."

Larry tiptoed, holding his arm as if he were dragging a body and clamping his nose tightly with the thumb and first finger of the other hand.

"I have it! Smell the shoes of all the Long Islanders. The ones that smell of fish glue will be those of the murderer! The nose has it!"

"Just a moment," remonstrated Hewitt. "Has anybody advanced the theory that there's a woman in it? It's the case in almost every crime. Why, it's the rule. Cherchez la femme!"

Dodd scowled even at the mention of the sex. Chandler nodded with interest. "Had you thought about a woman, Kennedy?" he asked. "Or is it too much for the sense theory? We've got to have a woman lead in this play, you know."

Kennedy replied, slowly: "I always think of a woman in every case. There is a woman in the Cronk case."

"Cronk's woman?"

"No. Cronk was a married man, devoted to his family. No, not Cronk's girl. I'm afraid you'll have to fall back on one of my senses."

"The thing I have been thinking about," hastened Dodd, changing the subject, "is what became of the thousand cases. They certainly weren't ever in Hinman's blue sedan—and you tell us they captured only about a hundred, from the Italian bootleggers. Somebody got away with the others. Who was it? How?"

Kennedy took a moment to answer. "I have been out on Long Island all day, or nearly so. I think I have been on every road that had anything to do with this rum-running episode and poor Cronk. That stuff you were wondering about, Dodd, was loaded on two trucks. The trucks were held up along the turnpike by a bunch of fake revenue officers. The drivers tried to bribe them. They took the money—then the hijackers took the stuff—and the trucks, too."

"The same that held up Hinman's chauffeur?" asked Larry Halpin, quickly.

Kennedy shrugged.

"Who told you that?" I asked, eagerly, seeing now a story. "How did you find it?"

"A woman," returned Kennedy, with a smile at Chandler. "An Italian woman, who knew one of the men arrested. She heard I was interested in the case. She was afraid her lover would be held for the murder of Cronk, as well as for bootlegging. She told what the prisoners refused to tell."

"Didn't I tell you?" exclaimed Chandler. "Didn't I say, General, the murderers would be hijackers? That Italian woman puts drama in it. I'm beginning to get it. If we're going to get it right, we've got to have some conflict in the story, conflict of two women over one man, conflict of two men over one woman—something."

"There," smiled Hewitt, "the murder's being solved—and not a sense in it, Kennedy."

"I quite agree with you."

Craig's subtlety did not go over their heads.

"But, Kennedy," remonstrated Chandler, "there's some sense in my putting a woman in this play—even if the woman in the case didn't show any sense—which I doubt."

"Bah!" This from Dodd, disgruntled.

"About this Italian woman," cut in Halpin, eager to help the playwright out. "She spoke for the bootleggers, not the hijackers, did she not? She—they didn't know the hijackers, did they?"

"That I am not at liberty to say. I turned her statement over to the proper authorities for what it was worth."

"Those men shouldn't be held for murder if they didn't do it," considered Hewitt.

"They're not, as far as I know," returned Kennedy.

"Just a moment, gentlemen," interrupted Chandler. "I want this play finished by you before you leave. You have left it up to these hijackers, without putting it on any one of them. Did they all do it—or was it done by one man?" He had turned to Craig.

It was thinly veiled that, under pretext of the play,

Chandler was quizzing Kennedy. I wondered how Kennedy was going to take it, how he would turn it off. Instead, he met it.

"Cronk was killed by one man. A terrific blow on the back of the head, a fractured skull, concussion of the brain, finished him. Probably he never knew what struck him. Yes, probably there were others involved in the hold-up of the trucks. But Cronk and the murderer were alone, miles away from it, when that deed was done. That is how I sense it to have been." Kennedy dwelt on the word.

"You said you were at the glue factory where they found the body. What kind of place is it? I think it might make a good set for my play. There ought to be realism enough in it to get over, quite the popular touch. Holds of ships, rooms of fallen ladies, glue factories, they're sure to claim the attention of the public of to-day."

Kennedy smiled at Chandler. "Well, it is lonesome enough, for one thing. Just a dirt road leading to it, with a footpath on one side made by the laborers and a ditch on the other toward the clay pit. The factory is really almost on the beach, just out of reach of the highest apogee tide. One smells it before one comes in sight of it. The laborers are not of the highest class. How could they be and work with a stench like that in their nostrils all day long? It smells within and it smells without. Most nauseating place I was ever in—and the cellar is the foulest place of all. Outside the building are bins to hold the fish not used immediately. Not used immediately may mean several days, and decomposition of fish waits on no man.

"Rubbish, scraps of dead fish in all stages of decay, old overalls, a general mess of filth, was the hiding place into which the body had been dragged, not just thrown. But a complaint had been made of the stench. The owners had been ordered by the county health authorities to clean up. Thus poor Cronk's body was spared that indignity for a longer time. But it was bad enough. There were no trees on this side of the road and the direct rays of the sun made it hot and putrid. Do you know, I felt so covered with slime and stench that I had to take a dip in the Sound to rid myself of the feeling."

"But did you find anything else?" It was asked almost simultaneously by Larry Halpin and young Hewitt.

Craig shrugged again and avoided answering. But I felt he must have something, else he would not have been now so apparently inactive.

"What about the clay pit?" asked General Tarns, more interested in the terrain than the odors.

"It was strange, just as Jameson says, to leave a body in a cellar, such a cellar, just because it was a cellar, and a little easier, perhaps, to get to than the pit. I was looking over the surrounding land in the hope of finding something more. It's true, the body would probably never have been found if he had flung it into the pit."

"Who was with you, may I ask?" put in Clarke. "Were you alone?"

Kennedy shook his head. "The sheriff and a deputy. They were unusually obliging, and wide awake, too. The eyes of those men and their memories for cars are remarkable. I said something about it. You see, since the last murder out there of an enforcement officer the city papers say things have quieted down and that the rum runners have gone elsewhere. It's only that the runners are more careful. And the law enforcers are keener, too. They notice every ear on the road, day or night, can tell you more about the make and trim of a car than a Broadway salesman. They know they never can tell nowadays how soon they may be asked questions or called to identify some particular car. And they've got a regular net of a secret organization, citizens who are good and tired of the antics of desperado rum runners and hijackers tearing up and down the roads, shooting up at night, a menace to every innocent automobile driver after dark."

Chandler fidgeted, a bit vexed at the turn of the conversation away from the drama as he saw it. Kennedy eyed him with a twinkle. "Aren't you satisfied with how your play is coming on?"

"No, I'm not. With all you fellows around, with your keen minds, I ought to get a little more imagination out of this crowd than I am getting. That woman ought to do more, much more. Hang the facts! Are you going to spoil a good story for the want of a few facts?"

"But you all crabbed your own game. I suggested the unusual, the senses, and immediately you reject it, because it is a now idea to you. Perhaps it's too obvious. You can't seem to use the very senses God gave you. And if you don't, will you tell me what else you've got that is any better? I'm afraid you may have to make up your last act as you think the case should be solved. That's the trouble with you playwrights. You can't see how to use what you've got already. Then you go off and make up something and alibi yourselves by calling it realism and shouting that fiction is truer than fact. Now, if you want a real mystery melodrama, I tell you again you can have it without moving from this corner. Only use one of the five senses. Count 'em—five!"

"But things in real life end so prosaically," returned Chandler, with artistic asperity. "I want a kick at the end, something that will send 'em home happy—and talking—so their friends will buy tickets to the show. That's the only advertising that counts."

"It's a case of the hijackers stealing all the kick," laughed Larry Halpin.

It was a remark that seemed to start other trains of thought. Kennedy caught it.

"I'll tell you what I'll do," resumed Kennedy. "Up-stairs, in my locker, in the room, I have some rare old cordials, probably like some of those stolen from Hinman's sedan. Ill blow the crowd. Maybe a shot of that cordial will stimulate the sluggish imagination and we can get a better play for Chalmers. Maybe the kick in the cordial will make up for the kick the hijackers stole, as Larry suggests."

General Tarns began expatiating on the merits of some of the stuff in his own locker, in comparison with Craig's.

"George," beckoned Kennedy to the boy, "get me a bottle of that French cordial I have upstairs." Craig selected a key on his ring, gave it to George as he whispered some directions. George bowed and departed eagerly. On an errand like this there was always a tip.

"There is a little history connected with this cordial," Craig leaned back lazily in his chair, slowly puffing at his cigarette, eyes upturned to the ceiling. "Years ago, before prohibition came along, I happened to be able to give a helping hand to a mighty fine Frenchman who was quite troubled over the loss of some trade secret which had been in his family for over two centuries. I located the chap who had stolen the key to it, here in America, and he was very grateful to me. He sent me these cordials from his own cellar when he heard the country was going dry. I have some here, the rest at home."

"Golly!" It was Hewitt's exclamation. "Think of having a whole sedan full of liqueurs stolen! Awful to think about—when you haven't had a charitable Frenchman in your past. I feel sorry for Hinman."

"Back to the Cronk case," exclaimed Clarke. "Well, you'll have a drink of genuine B. P. cordial, anyhow, soon, even if we didn't solve the mystery of Hinman's chauffeur to the satisfaction of Chandler."

George's beaming face appeared. "This bottle, Mr. Kennedy, makes me think of the old days. It was always good, but this is so much better, now, because it is harder to get."

"You said a mouthful, George," nodded Hewitt to the boy, who was a favorite of the club.

Halpin looked at the bottle narrowly. "This is like the stuff I used to import before prohibition. Much of it passed through my hands. I used to take some wonderful orders from this club alone. With the coming of dry times a big source of income dried up, too. Well, I was due to retire, anyhow, getting along in years, not many more years to play, if I was ever to do any playing."

Carefully George opened the bottle, almost reverently. Its aroma, heavy and sweet, seemed to permeate the air about us with a delightful reminiscent odor of other days. Into the little thin cordial glasses the yellow liquid was poured, shining, smooth, heavy like a scrap of old-gold velvet.

"This is a chartreuse," I observed, catching sight of the label. "No fake about that."

"But you'd be surprised how much of it is faked," Halpin pursued. "I found that out even in my business years ago. I learned to tell the difference."

"How do they fake it?" asked Hewitt.

"In the making. The best is distilled. You see, the makers of a cordial macerate various aromatic substances, such as seeds, leaves, roots, and barks of trees or plants with strong spirit and subsequently distill the infusion, generally in the presence of the whole or at least a part of the solid matter. Then they age it," Kennedy was speaking contemplatively. "This is distilled, and old, too."

"Of what do they make this? Can you tell?"

"What's the information for, Hewitt," asked Halpin. "Do you like this so much?"

"I sure do. Perhaps I like things better not quite so sweet. But you see I don't know much about drinking or drinks. I've been very busy," the young man added.

"Well, my bootlegger can help you out if you want to buy any cordials. Vermouth, benedictine, chartreuse, curaçao, kirsch, absinthe—he handles them all. Very secretive he is, but he manages to get me all I need. And you know the saying, Hewitt. When a man is willing to share his bootlegger with you he really cares for you!"

"It beats the devil," Clarke nodded, "how the stuff creeps in. No dearth of it anywhere. Crimes increase as the demand for it hangs on."

Hewitt was thanking Larry, but looking at Clarke out of the corner of his eye. One doesn't like to make a date for a bootlegger when one's prospective father-in-law is near—or perhaps one does with some other than Clarke. Halpin'a offer was ignored, at any rate for the time.

Chandler was still engrossed with his notes, scribbling over what he had written. Nothing seemed to suit him. It amused Craig.

Again the little glasses were filled.

"Excellent!" Clarke exclaimed.

"Marvelous!" admitted Chandler, bowing appreciatively.

"Fine!" added Larry, sipping slowly at his glass and seeming to roll each sip about in his mouth.

Kennedy held up his glass. Through the amber-colored liqueur the light filtered and glistened like the rays of the morning sun, golden, translucent in its sheen.

"Ah, it's not the taste alone; it's the bouquet," remarked Kennedy with the enthusiasm of the connoisseur. "That is not a drink. That is a perfume—fit for an empress. Most exquisite. Its age makes a drop of it priceless, nowadays."

"Do you know, Kennedy," hastened Chandler, "I've seen some of it an exquisite green. This is yellow, golden, beautiful. What's the difference?"

"One difference is the percentage of alcohol. The green is about fifty-seven, the yellow forty-three. But it also is caused by the varying nature and quantity of the flavoring matters employed. This was made in France years ago. But since 1904, all the best chartreuse is made in Spain, I believe. It was during that year that the Carthusian monks, makers of the genuine Chartreuse, left France because of the Associations Law." It was Larry Halpin who answered, the facts of the business on the tip of his tongue, as of old.

"Oh, if I could only get a setting like this in my drama. The glamour of real chartreuse in dry days, good friends awaiting the coming in by some secret channels of their liqueurs, and end with a raid and a fight—and the murderer!" Chandler could not get his play out of his mind. The liqueur seemed only to increase his imaginative longing. "Then, there's another one, I used to like, Crème Yvette, wasn't it? Distilled violets! Ah, what a drink when one has a bedroom farce to finish!"

I was watching Kennedy's face. It seemed, as Chandler spoke, as if his nostrils dilated. I wondered at Kennedy for being even a bit suggestible.

"In the old days it was more appealing to me," resumed Kennedy, "this matter of drinking liqueurs. These rare cordials need an element to get the most out of them, that is aesthetic, elevating, calming. Now all the art of these things has gone for the drinker of to-day. Where before one could see the simply clad monks at work in the fields, in the distillery, busy to distraction, with pride and confidence in their ability, absorbed in their tasks, realizing that with the money obtained from the sales of their secret beverage they could carry on their beloved benevolences especially in the neighboring villages about their monastery. It was they who built the churches, the schools, the hospitals and orphanages, and maintained them."

In a rapt, almost detached voice Kennedy continued. "In the present time when drinking most cordials, one feels and knows he is a lawbreaker. Most of what one gets now one should not have, by all that is legal. Bootleg has made it so plebeian, common, ordinary, low. There is nothing much that is aesthetic about it any more. It is just drinking, drinking for the effect. Even when one feels the warm glow stealing down the throat, the senses charmed, quieted by the fragrance and taste, one cannot forget the evil conditions. We do not feel assured that the patient monks distilled it. We are wondering: Oh, this is something synthetic. Tastes like it; but not the same. Is it that it lacks the perfect bouquet, the spirit of the makers?"

"Great guns, Kennedy! Give me another glass!" General Tarns ejaculated it earnestly. "How soon again may I know I'll have the real thing? If you talk that way much more I'll clean forget the Cronk case. Just let me feel that warm glow stealing down my throat that you so gloriously described. Kennedy, you should have been a cordial salesman!"

There was a laugh at the general's enthusiasm, for he had a reputation as a conscientious two-handed drinker. I noticed, too, that when Craig had finished speaking everyone took a sip with renewed fervor and appreciation.

George had come up quietly beside Kennedy's chair. Not for the world would he have interrupted. He just stood there with his finger on the chair, drinking it in, waiting for Craig to finish. Then he bowed, leaned over, and whispered some message to Kennedy. Of its purport we could get no inkling from the faces of either. Kennedy's was motionless, expressionless. Only there was a stiffened restraint for a moment, a route hesitation, until Tarns spoke.

"I hope it wasn't to tell you your last bottle of Otard was broken," joshed Tarns.

Kennedy merely smiled and the smile flitted politely. He sipped at his cordial slowly, lightly. He raised the glass to his lips again, closed his eyes, and swallowed slowly. I don't know why we watched him so closely. In some way was conveyed to us a surcharge of feeling in that little group. I couldn't tell whether it was the effect of that forty-three-per-cent cordial, or some static, electric, mental force emanating from Kennedy. I felt it, we all felt it as we sipped slowly.

Suddenly Kennedy opened his eyes and spoke. "They have captured both the hijacker trucks, the trucks the hijackers stole with the stuff loaded on them—and the men that drove them off from the rum runners."

Somehow was conveyed the impression that Kennedy had not told all.

"Caught the hijackers themselves!" exclaimed Chandler, excitedly. "Where did they get them?"

"Oh, on a little farm back of Laurel Hill Cemetery. I expected they'd locate them—but sooner." Kennedy was speaking in a slow, matter-of-fact tone.

"Well, did the senses do it, make the arrest?" asked Larry Halpin, with a wink to us.

"Can it, Larry!" adjured Chandler, his interest fired at once. "I'm going to stick along with Kennedy to-night, so to speak. I believe if I have enough patience and he doesn't run off the track with this new and very interesting theory of the senses, I'll get the finale of the play before I leave him, some way or other."

Kennedy looked at Chandler with a glint of humor.

"That means, Chandler," I put in, too, "that if you for a moment think you're going to get a play out of it, I'll stick, also, and get my story!"

"I know why I'm going to stick," chuckled the general, his eyes significantly on the dwindling bottle.

"For the same reason that I have," added Larry. "For the sake of the cordial—and old times' sake."

Kennedy held up the bottle reflectively. "I must admit I'm glad you're not the last bottle I have. The general's regard for me can be satisfied. I expect to be assured of his friendship for some time to come."

Up in the light Craig held the bottle. He filled the glasses of those who cared for more. Then he took it, held it gently to his nostrils.

"Ah!" It was long drawn out. "Some perfume! Just smell that bouquet, that aroma."

Everybody sniffed, paused, held for a second the delight of the intake of breath through the nostrils. There were renewed murmurs of approval. They rhapsodized over the aroma.

"How about it, Larry? Like it?" asked Craig. "Do you ever get anything like that that's synthetic?"

Larry Halpin raised his hand protestingly. "I love it. But my regard depends on my taste and other things. I? I can't smell a thing. It's congenital with me. I like the stuff, love it—but I can't smell it." He smiled deprecatingly at us as if nature had cheated him in bestowing gifts upon him.

I felt a sense of sympathetic curiosity.

"H'm!" Kennedy considered. "So!" He paused a full minute. "Can't smell a thing." Again he paused, as if running back over something in his mind. "Larry Halpin, retired, once importer of wines and cordials. People thought you got wealthy out of it, Larry. They didn't realize how prohibition had knocked out your income. But I know now how you secretly adjusted yourself to it, how, as head of a syndicate, you organized an underground rum-running system of importation of the stuff from Quebec. Then the rum fleet knocked that."

Larry Halpin stood a little apart from the rest of us. Unconsciously we had dropped away from him as Kennedy focused attention on him. Defiantly he glared at Kennedy.

"When you start something, Kennedy, be sure you can go through with it and finish it—or there's likely to be an awful come-back. You'll have to back up those insinuations. You can't convict a man just because he can't smell."

"I'm not worrying about any come-back, Halpin. The deputy out in Suffolk identifies your Sunbeam, seen on the same road where they later found the blue Packard sedan, not long before the time this murder must have taken place. They've noticed it about taking an active interest in what's doing at the ports on both shores of the island. That was a bit suspicious, considering the profits you made importing wines and liquors before prohibition."

"The rum fleet means nothing to me, Kennedy. I've never bought a case from them," growled Halpin.

"Probably," agreed Craig. "You smuggle it in from Canada. But these rum runners from Rum Row were cutting into your border bootleg profits frightfully. It had to be stopped. I have the facts from your agents. There's no honor among rum runners. A syndicate was formed, and you were at the head of it, to organize the hijackers."

Halpin took a step forward as if to controvert it, but Kennedy raised his band. "Just a moment, Larry. Hear me out. Besides, Percy Hinman had been one of your chief customers, in fact carried with him many other customers, here in this club, in the Rock Club out on Long Island, and others. When the German system was tried, of bringing the stuff by an old tanker to these shores and lightering it in, Percy Hinman canceled a large order. So did others. They could get it cheaper, delivered almost at their doors.

"It must be broken up, if the Quebec ring was to survive. One way was to tip off the revenue men, ashore and on the boats. If they did not get them, then the hijackers, to seize the stuff. So, in effect, you turned hijacker, promoted hijacking. It was up to them to get the trucks. But there was Cronk in Hinman's car. It would never do to let him get through your line. Some one must stop Cronk. You did it. But Cronk knew you. Therefore he must be put out of the way. You did that, too."

Chandler was leaning forward in his chair, his play forgotten in the daze of surprise and horror that one of his club mates should be charged with the brutal crime.

"The very idea of the fish-glue factory touched your fancy as being repellant, keeping folks, prying folks, away. Only a man without a sense of smell would have gone in that place and overturned the refuse as you did when you concealed poor Cronk's body. The workmen themselves, used to inhaling the stuff every day, wondered how the murderer could have done it. It seemed to have been done so deliberately and thoroughly. Why, it would have turned any other man's stomach not accustomed to it to do what you did. So! You're the man without a sense of smell! Well—you're wanted!"

General Tarns, playing nervously with his thin-stemmed glass, twirling it again and again, was muttering: "Thought they'd take Kennedy into camp, eh? The five senses! Then the sense of smell was the solution, after all!"

Kennedy still met the defiant stare of Halpin. "It's no use. You'd know it if you knew what I know. It's the message George brought me from headquarters. They've found the Sunbeam—and Hinman's stolen cordials with it!"

Larry Halpin seemed now to wilt back into the leather chair behind him, his hands before a colorless face. He seemed to shrink.

"Sorry, men," cried Kennedy, brusquely. "Sorry to have this happen here. But it's the only place I was sure to meet him this evening. George, you may tell that Central Office man to step in—the fellow that brought the message. He can take you downtown, Larry, with the bracelets, if you pull any rough stuff."

Chandler was fondling the almost empty cordial bottle, as if getting ready to introduce it as a prop in his stage set.

"By the way, Chalmers," smiled Kennedy, "George is not merely careless. He is stupid. That bottle he brought wasn't the cordial I wanted, not the one I told him."

Chandler shrugged. "But you caught your man just the same."

Kennedy nodded. It wasn't worth arguing.

"That's not the point, Chandler, to me," I jumped in. "He proved his case—that crime detection depends on the senses—or the lack of them!"

"Yes, by golly!" broke in Tarns, in his jovial voice. "Yes! Convicted him on the sense of smell—and he couldn't smell a damned thing!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.