RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

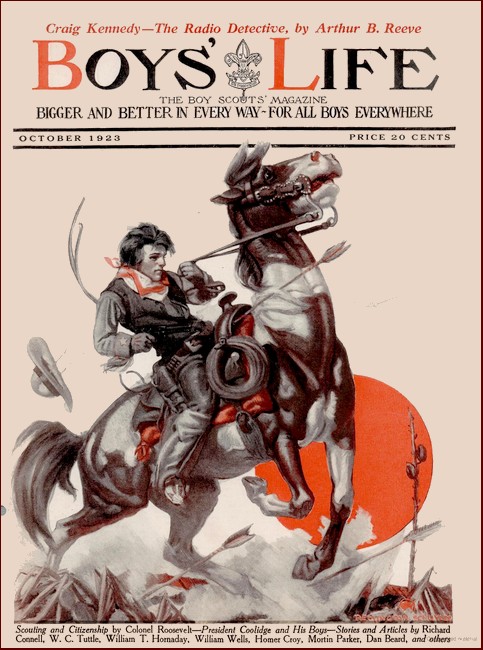

The Boy Scouts' Craig Kennedy, Harper & Brothers, 1925,

with "Craig Kennedy, Radio Detective"

Boys' Life's, October 1923,

with Part I of "Craig Kennedy, Radio Detective"

"THERE must be a thousand discharges for every bolt of lightning that hits a person."

Craig Kennedy and I seemed to be the only intrepid souls at the Nonowantuc Country Club out on the north shore of Long Island overlooking the Sound. The lightning had driven everyone indoors except ourselves.

Craig strode up and down the half-enclosed porch of the club. Out into the blackness of night and the fury of wind-driven rain he peered admiringly at turbulent Nature.

The water was overflowing the gutters of the roof, too much for the capacity of the leaders. It overflowed in miniature waterfalls, gathered with other streams on the sandy road, digging gullies. Not a living moving thing was visible.

"Fortunately, too," went on Craig, "of every hundred streaks of lightning, about ninety are from cloud to cloud, spill-over discharges, mostly horizontal, doing no damage whatever. About ten flashes in a hundred come vertically, that is, down to earth in a straight line. Some flashes come sideways and seem to be crooked, although there are really no flashes zigzagging like the teeth of a saw as artists generally depict lightning."

In the distance down the road the purr of a motor punctuated Craig's remarks. "What a night to be driving a flivver!" he exclaimed. "Only a crime or a death would get me out in this storm!"

A beautiful, awesome flash. Craig with his split-second watch was calculating approximately how far off it struck.

"The intense, straight flashes," he remarked, "are those to be feared—and it is a silly person who stands out in the open when such flashes are seen. He invites trouble, but the invitation isn't always accepted. Did you ever hear the ten commandments about lightning? No?

"Well, the first is, 'Don't stay out on a beach or in a field. Get under cover, if possible. If not, lie down. Don't remain standing.' Then the second: 'Don't stand under a tree. You are forming a part of the line of discharge since the body, particularly the skin if it is moist, is a better conductor than the trunk of the tree.' More people are killed by lightning in this way than in any other. 'Don't stand in a doorway or at a window near a chimney.' Lightning sometimes follows a current of air, particularly a column of rising warm air. And don't laugh at anyone's nervousness during a severe thunderstorm. There's good enough reason to be nervous..."

A dripping station wagon, curtains flapping in the wind, raced up the driveway of the club, interrupting the ten lightning commandments. It stopped with a quick jam of the brakes.

A small figure muffled in a yellow poncho jumped out, an excited collie barking at his heels. In two leaps the boy was on the porch.

With a jerk of his arm he uncovered his head, took a deep breath, as he shook the water off his hair and out of his eyes. He started for the door to the club, then stopped.

"What is it, Ken?" Craig stood and stared. "Anybody hurt?"

"Oh, Uncle Craig—you must come over—right away—to the Gerard house—"

I recognized young Ken Adams, or Craig Kennedy Adams, Craig's nephew, the son of his sister, Mrs. Walden Adams.

My curiosity brought me abreast of them just in time to receive a shower-bath from Laddie, shaking the water off his thick coat.

"What's the matter?"

"A hold-up at Gerards!... Sis and Mother were there... and I was over with Dick, I left Sis crying over her pearls... and Mother's lost her emeralds. Everybody's been frisked of something. Gee!" Ken's face glowed with excitement.

He was a month or so past fourteen, with a high forehead, big, sparkling brown eyes, ruddy, tanned cheeks, a fine firm mouth, a boy whose face and bearing showed initiative, courage, determination.

Craig laid his hand on Ken's shoulder. "Why didn't you telephone?"

"Couldn't. The crooks cut the telephone wires first. I left Dick trying to locate where they were snipped and took our station wagon, beat it with Laddie to you. Come back with me, please, Uncle Craig... Help Dick and me catch these hold-up men!"

Kennedy smiled at me as he slapped Ken good-naturedly on the back. Laddie was jumping about, too, as if he knew that stirring things were about to happen.

"I said only a crime or a death would get me out on a night like this," laughed Craig to me. "Well, Walter, it's a crime."

"I think it is a crime!" I laughed back with a nod out at the veritable cloud-burst.

"Oh, it's not so bad, Mr. Jameson," urged Ken. "It's fun!"

"What was going on at Gerard?" asked Craig. "A party?"

"Yes, the Radio Dance."

"Radio Dance?" repeated Kennedy, "You couldn't get anything over radio in this storm, could you?"

Ken spoke up quickly. "No, Uncle Craig, of course not. But Mr. Gerard, you know, wanted to celebrate the installation of the radio set—oh, it's a dandy, the latest thing.—so he let Vira Gerard invite all the crowd there to a dance....

"Dick Gerard and I had to go—but we hated it. Vira asked a couple of girls over—oh, they were all right—but most of the time they were dancing by themselves. We were watching the radio—" he paused with just a bit of disgust at mere dancing—"thinking what we could get over it besides jazz—how far we could receive—maybe London, you know."

He caught Craig's lips about to move and anticipated the injunction to get back to the subject. "When the storm came up," he added hastily, "it put the radio out. They used canned music. Then we could really get an idea of the parts of the set.... Uncle Craig, it's bully 1... Well, that was when I saw this masked man step in through the French window. First of all he fired one shot up through the porch ceiling, then the girl with him went right up to Ruth..."

"Girl?" I broke in in surprise.

"Yes—a girl."

"Call for Mr. Kennedy!" The club bell-hop appeared in the doorway.

"This is my official invitation to find the robbers, Walter."

Craig hurried in, leaving Laddie, whining and wet, nose to the space between door and sill, waiting and scratching with his paws on the door.

It was not many minutes before Ken was surrounded by admiring ladies of the club. This news was diverting. One must forget even the lightning when a hold-up had taken place so near.

"Oh, dear... dear me! Maybe they'll be here next! I'm going to get my little pistol I always put under my pillow nights after I've looked under the bed!" An excitable little old lady almost ran from the room.

Ken smiled as Craig nodded. "You see, Ken? She believes in preparedness, too!"

Kennedy had just returned from the telephone booth.

"It was my sister Coralie, as I thought. She got over in a closed car to the next estate to get me. The wire was still out of commission. She was worried over you, too, Ken," he nodded reproachfully, "until I told her you were here. I guess you didn't take time to tell your mother you were coming. All right, now. Wait till I get my rubber-coat and we'll be with you."

A FEW minutes later Craig and I were in the front seat while

Laddie and Ken huddled together in the rear of the flivver.

The roads were terrible. The rain beat almost directly in our faces and it was only with difficulty that we could see.

Only once were we passed on the shore road. Coming down at terrific speed from the harbor a yellow racer loomed up. There was a really dangerous crown to the road at this point. The racer seemed to hog the road and we were almost ditched as we pulled over.

That was the only car out. At last we came to the Gerard gate with its two huge wrought-iron eagles standing guard over the high brick piers.

Swinging perilously around the steep curves that led to the Gerard country house at Oldfield on the cliffs over the Sound, we suddenly saw the brilliantly lighted house before us.

Excitement was the order of the moment. Coralie Adams ran out to meet us. Even the rain failed to daunt her. She forgot also to scold Ken. Inside we were surrounded by a group of young people, some angry, others half in tears, most of the fellows disgusted with themselves.

Kennedy caught sight of his pretty niece. "Now tell me, Ruth. How did it happen?"

"Uncle Craig!" She said it with a sigh of relief as she lifted tear-filled eyes. "Grandmother's beautiful pearls are gone! I was dancing with East Evans.... I heard a shot.... We both turned. I saw a gun held by a girl—pointing right at us! The girl laughed a hard laugh at me. 'I've always wanted a string o' them beads!' she said. 'Hand 'em over!' 'Don't move there, bo!' she said to East. 'A fly can pump this gat off if he ain't careful. Stay right where you are, see? I'll have that diamond, if you don't mind!' Easton had to give that up, too."

Ruth shivered and looked about fearfully, still, as if the automatic might reappear and go off merely for the telling about it.

"They came through that French window. We were the nearest and we got it first. There were two of them, a fellow and a girl. The man kept the crowd covered, then, while the girl made all the others give up. They seemed to know what they were after. They must have heard all about this Radio Dance. By that time, of course, the radio was out."

"Yes—jazzed," observed Craig. "Nature's jazz did it."

"I saw East move," broke in Ken. "That's when this girl frisked him. The man had all the others covered by that time. Then the girl saw Professor Vario—you know him, from the Radio Central Station at Rockledge? He started to move, too. 'Say, if you get fresh, I'll fill you full of lead—see?' the girl said. 'Now, freeze! Understand? Quick! I got another engagement, too, to-night. Come on—fork over!' They lined 'em all up along that wall and—"

"They took something from all of us," exclaimed Mrs. Adams, "my emeralds, Mrs. Gerard's diamond necklace—oh, they must have got away with a quarter of a million!"

"Yes, and when I moved, that girl switched the gun at Ruth, instead of me—but she kept her eyes on me! I was stalled!" It was Easton Evans speaking. "She talked like a gun-moll—but she had the hands of a lady!"

Kennedy was a mental electroscope for discovering stray currents of facts.

"There must be something new in order to catch criminals nowadays," Craig had once told one of the fellows in our class after we left college. "The old methods are all right—as far as they go. But criminals nowadays are keeping up with science."

"What a hobby!" our friend had exclaimed. "Never knew of anyone in our set ever taking up a thing like that!"

"It's just your set that needs it most. They're always being shaken down, blackmailed, victimized, until they—the wise ones—are the easiest marks of all!"

So in his casual way Kennedy had traveled to London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna where he had studied the amazing growth abroad of the new criminal science. It was not merely a hobby. He had absorbed about everything from the successors of the immortal Bertillon.

"Mrs. Gerard," queried Kennedy. "May I ask how many there were at the dance?"

"Twenty, including ourselves."

"That's strange," interrupted Easton. "When we were lined up against the wall I counted—sixteen. I thought it was funny—two of them holding up sixteen of us!"

"H'm," nodded Kennedy. "Who were out when the hold-up occurred?"

There was silence for a minute. Then a girl spoke.

"Oh, Mr. Kennedy, I might as well tell you. I was out with Glenn Buckley."

To my surprise it was Vira Gerard. She said it, too, with a certain amount of bravado. Mrs. Gerard colored and was silent. One could see that she was annoyed at Vira. Everyone turned toward Glenn.

"Yes," he nodded, without any show of nervousness, "we had gone over to the east wing of the house to telephone to the Parrs to come over. We couldn't seem to get the operator, tried several times. I thought the line was dead. Finally we decided the storm had put it out of business. We were coming back to the dance when we met Dick and Ken running toward the telephone. That was the first we heard about it, wasn't it, Vira?"

Glenn Buckley was a handsome chap about twenty-one, tall and slender, with dark hair and eyes, eyes that were restless for excitement.

Somehow I wondered if Vira and Glenn were telling the truth. Kennedy nodded, however, in seeming acceptance and it seemed to satisfy them. "Well, who else were out?" he persisted.

A rather pretty brown-eyed girl pushed her way through the crowd to Craig's side. "Hurry up, Jack Curtis—confess with me!"

A good-natured laugh came from the others gathered near. Craig turned with an encouraging smile. "And—you are—?"

The girl smiled mischievously. "Really, Mr. Kennedy, you don't know Rae Larue? Now, Glenn, and Jack Curtis—see—here is one man I don't know and you say I know every fellow in town and country!"

"Oh, I say, Rae, I was only kidding." This was from the chap addressed as Jack Curtis. "A lot of the people were worried over their cars when they saw the storm coming up so fast. I volunteered to go out, drive the open cars into the garage, raise the windows of the closed cars. Rae went with me. But the rain came before we finished. We had to wait." Rae interrupted. "Then the shouts and lights in the house scared us. We got wet but we just had to run back to see what was the trouble."

Again Kennedy nodded. By this time he had a pretty clear idea of entrances and exits of the various people. I followed him through the French door which the crooks had used. He was examining the porch and the steps with his electric bull's-eye. But there seemed to be nothing to indicate who they were or even in what direction they had gone. "Hey, Ken! Where are you, Ken?" I heard another boy, excited, down the broad veranda.

"That's young Dick Gerard," recognized Craig. "Let's see what he knows."

DICK GERARD, Ken's pal, was also about fourteen. His tawny

hair, so much of it, had been the cause of many battles. Those

frank blue eyes had issued challenges to many lads much older

than himself who had dared to insinuate that it was red. Very

fair of skin, with the usual freckles over the nose, long legs

and arms, with boyish awkwardness, he had with it all a smile of

such winning good nature that one just naturally liked Dick.

"Hello, Dick," greeted Kennedy. "Find anything?"

Dick was flattered. His face lighted with happiness as he saw Craig. "Mr. Kennedy! I'm glad you're here. You'll have to take this job. It's too big for us. I'm glad Ken found you at the Club. No, I haven't found anything—much."

The boy stopped abruptly, as his father came on the porch but an encouraging smile from Craig caused him to go on hastily. "I couldn't find any real clues. I guess I'm not much of a detective. But down at the garage there's a chauffeur from the next estate. He heard about the hold-up, came over to get the low-down. He told me he was going up to the station to meet the ten-thirty train just before the storm. He was nearly edged off the road by a big yellow racer coming down. He said he thought it turned up our road. Anyhow that must have been about ten minutes before the hold-up."

"I'm afraid, Richard, that's just backstairs gossip," commented Mr. Gerard, who was a corporation attorney. Dick lapsed into silence.

Craig said nothing but the frown on his face indicated that he felt this was no way to teach the young idea how to shoot, "A yellow racer?" he repeated.

"What ails that car?" put in Ken, undaunted by old Mr. Gerard's conservatism. "They almost dumped our flivver when we were coming back, only that was on the harbor road. Uncle Craig, do you suppose the crooks are driving that car?"

"Oh, anybody might hurry to-night," insisted Mr. Gerard. "The speed of the car doesn't amount to anything."

"Not an illogical deduction, though, Ken," encouraged Craig. "The fact of a strange, high-powered car hanging around, off the highway and the main country road, out here by Oldfield, coming up the harbor road, later, certainly does look suspicious."

"Maybe if we watch out for it, it will give us a clue," replied Ken with animation.

"I don't think you'll see it around here again," I remarked.

"No; perhaps not," Craig considered. "This is the first place robbed out here. There will be more—in other places."

Ruth and Professor Vario joined us, Ruth still grieving over the loss of her pearls. The Radio Central at Rockledge from which Vario came was some ten miles east along the shore of the Sound. The station covered an area of ten square miles, with twelve rows of 410-foot towers radiating for a mile and a half from the central station, without a doubt the largest radio plant of its kind in the world.

Professor Vario was handsome, dark and serious, with a cultured foreign appearance.

"You know," observed Craig to Vario, "there's no invention that has changed the character of crime quite like the automobile. The crook can strike and make a get-away in it. In less than an hour he may be in a town more than a dozen miles away. But fortunately, invention keeps pace with invention. We can also use automobiles for pursuit. Then there are the telephone and telegraph, and the radio."

"I wouldn't build up any false hopes about what the radio can do in catching criminals, especially such as these," observed Professor Vario with a shrug. "However, if you get the telephone working again, of course, I'll be glad to instruct the station."

With the two boys and myself Kennedy set to work to find the spot where the wires had been severed. We found it near the house and by shortening the line a bit Craig had the service restored.

He lost no time in spreading the alarm. First he called the sheriff, got his deputies at work looking for the yellow car, as well as alarming the garages of the country. His next move was to get the state troopers watching the ferries from the island. Then he called our friend Deputy O'Connor of the city force to watch the bridges. Lastly he took advantage of Professor Vario's offer to broadcast an alarm from the big Radio Central station.

It was late when we left Oldfield but there seemed to be nothing further to do but wait for some new clue to develop as a result of this alarm.

"Who was that mystery girl, with the bag, who gathered in the stuff with the hands of a lady and the voice of a gun-moll?" I queried as we were returning to the club far after midnight.

Kennedy shook his head. "It comes down to this, Walter— whether it is just another crime in the wave of crime that seems to have been hitting country places this summer—or is it a job pulled off with the assistance of some one at the dance?"

IN the morning there was no news of the yellow racer.

Deputy O'Connor had no report of it crossing any of the bridges. Nor had the state troopers any word of it crossing by any of the ferries from the island. It was therefore practically certain it was on Long Island yet, for it was a marked car that would not likely slip by without being picked up.

I had telephoned in to the Star a story of the radio robbery and already our news photographers had arrived. I knew that reporters from the other papers must be on the way, that it could not long remain the Star's exclusive story.

It was a good story for the Star. There is no doubt that people rather enjoy reading of the difficulties of the rich. The thrill of a venturesome hold-up, the romance of the missing jewels, many of them heirlooms that were priceless, the pretty girls and their escorts would provide a sensation for many thousands who would never own a pearl necklace.

Newspaper publicity is a necessary evil but I made up my mind to soften it as much as possible and save the Gerards and the others as much as I could, so I accompanied the camera men to act as a buffer between them and Mrs. Gerard.

I think she appreciated it. As for Vira, she fought shy of the cameras but seemed rather anxious to be with us, to talk to us.

"I scarcely understand that girl," I ventured to Craig aside, "unless it is that she wants to know how much we have found out."

Craig smiled non-oommitally but did not answer. Vira was coming toward us again, with her mother.

Suddenly I heard her exclaim. "Look! Ken: Why, Ken, what have you been doing?"

"I had a fight." Ken was quite frank about it. "Where's Dick? Is he back?"

Craig surveyed him and Ken grinned a sickly grin at us. "Whom were you fighting with, Ken?"

"Hank Hawkins—that mucker." He stopped.

"Why, he is much bigger than you," interrupted Vira..

"He doesn't think so now," Ken said it quietly but with the unconscious pride of victory in a good cause.

"Ken, why were you boys fighting? I wish Dick and you would be—less like savages." Mrs. Gerard was severe but there was a motherliness about her tone as she saw his plight.

"Dick wasn't in this, Mrs. Gerard. Don't think that. I'm glad he wasn't. If he had been, it would have been Dick instead of me." He checked himself, evidently didn't want to say too much.

I looked the boy over—a swollen eye that would be black before long, a cut over the lip, hair rumpled, dirty, coat minus a couple of buttons. He surveyed himself gloomily now but smiled hopefully at Mrs. Gerard as she said, "Come inside, Ken. I'll fix the buttons, clean, you up a little—before your mother sees you."

Ken nodded appreciatively at Mrs. Gerard. But I fancied he gave Vira a quick, somewhat troubled look.

"What was it all about, Ken?" Craig asked it aside and under his breath.

Ken swallowed hard, flushed a bit, finally answered, never lifting his eyes to Craig but closely watching the tracing of his foot on the porch. "Well—er—you see—it was this way, Uncle Craig. I needed more money than my allowance. I spent all that—on radio. I wanted to get some other things for it. So I tried to earn it. I heard Hank Hawkins made a dollar the other day working for the captain of that former sub-chaser's that's anchored in Die harbor. It gave me an idea. I could do the same. I rowed out to the boat. Hank was on it, all right, with some of the crew. They shouted to me, what I wanted, and I shouted back I wanted to earn some money, too."

Craig smiled, amused. After all the sons of millionaires are boys, too. The love of independence, the desire to earn and work for themselves makes them kin to all boys. "Well, did you earn it?"

Ken shook his head, disgusted. "No. Hank called me over and I came close to the chaser. They turned the hose on me from the deck."

"Who is this Hank Hawkins?" asked Kennedy.

"He's the son of Homan Hawkins, the banker," supplied Mrs. Gerard, with obvious disapproval. "Both Mr. Hawkins and Hank's mother are quite—well, sporty—always away somewhere. I believe they are on a cruise now, with some friends. Hank is a clever boy—but left too much to servants."

Kennedy nodded. "What did you do then. Ken?"

"Rowed back to shore, sat in the sun on the other side of the dock, and waited for Hank. He was a long time coming."

Kennedy laughed and urged the boy to go on. "Well, Hank came ashore at last in his skiff—and we had a rough and tumble. Hank doesn't fight fair. It took me a little longer to lick him—but I finally got him down and he was glad to—to beg off." Ken stopped again much as before. He was not going to say too much.

Mrs. Gerard was anxious to fix him up and he left, head thrust forward, chest out, his arms curved out slightly at his sides, fists still clenched.

"Great kid," I smiled as Mrs. Gerard shook her head with an amused tolerance. "I suppose he's progressing upward from the cave man, eh?"

Craig however was serious. "Yes... but that fight was over something else. Ken always looks me in the face when he's telling the whole truth, and he didn't look at me just now. He has something that worries him."

"I wonder if Vira is in it in some way?" I whispered. "I thought I saw him look strangely at her."

"That's what suggested it to me," was Craig's brief answer.

The butler appeared with word that Craig was wanted on the telephone.

"It was Easton Evans," he reported. "He's down at his laboratory boathouse. He has some news."

I KNEW that East Evans had been Ken's scoutmaster, that for a

couple of years they had been at Pine Bluff Camp during part of

the summer. Ken Adams was a bright boy but had been backward

about some things. The camp had made a man of him—90 per

cent, now in the arithmetic that he had flunked before—all

because it had taught him responsibility. Ken Adams this year had

won a cup for camp spirit, too. East Evans was much interested in

radio. So Ken was allowed the freedom of East's "laboratory" in

the old boathouse.

"Besides," considered Craig, "Easton can get the truth out of Ken if anyone can."

I realized now that Kennedy had great respect for Easton, for while Craig was at work establishing and carrying on a sort of "Craig Kennedy" laboratory for the Navy during the war, Easton, then a boy, was a patrol leader very active in organizing the auxiliary coast guard of the Boy Scouts. They had helped mobilize the boy power of the nation. Nothing much was ever said about it during the war, but in this work for the Navy Department the boys, especially those with Easton, had discovered an unbelievable number of suspicious radio installations, as well as many more that might have been at a moment's notice turned to use against the United States.

It was only a few minutes when the three of us were in Easton's wireless workshop. It was an old boathouse on the estate of his family where he had done some remarkable things with wireless.

Outside he had a big aerial from two poles. Craig looked with admiration at the completeness of the workshop inside, the hack saws, mitre saws, crosscut saws, frames, chisels, gouges, files, vises. There were drills, hand, breast, geared and twist, pliers with all sorts of noses. There were wire, copper, iron, aluminum, plain and insulated, of all sizes, flexible insulated wire cord, enough to supply a store. Fibre board and bakelite, porcelain insulators, tubing, sheet brass, sheet copper, everything at the very finger tips of the young inventor.

Easton Evans was a graduate last year of a famous engineering school, son of a well-known engineer, and himself an inventor with an aptitude for radio. He had worked on wireless transmission of photographs, a wireless dictograph, directed by Craig himself, a wireless telautograph and just now was installing some radio attachment to an airboat. The lower part, underneath the laboratory, of the boathouse had been converted into a hangar, where he housed his hydro-airplane, the Sea Scout.

"Well, broadcasting from the Radio Central did some good," he greeted Craig. "I've just picked up a radio fan up in the country who says he saw the yellow car over toward Smithtown."

"So, they are chasing all over the country," nodded Craig. "I expected it. Well get more." He was looking out of the window at the harbor. "I suppose you have observed a subchaser that's been anchored here a couple of days?"

"Yes," returned Evans slowly. "But not particularly, except that it seemed to be equipped with wireless. Naturally I always look for that. I don't see how a boat can be without it."

"Well, what's this mystery craft doing?" pursued Kennedy "Rum running?"

"Not likely."

"Well, what?"

"I'm sure I have no idea."

"Where does she lie?" Kennedy was over by the window.

"Why, she went out this morning, I think, just now."

Over by the window Craig managed to explain that Ken was holding back something about a scrap with Hank Hawkins. Easton nodded, went to work, puttering with some wireless apparatus. Ken watched.

"What makes you so quiet, Ken? Are you stalking a ghost?"

"No ghost—I hope—East."

"Too bad you couldn't have put on the gloves with young Hawkins and had a gallery to cheer. I should like to have seen the bout myself. Tell me, what was it about?"

Ken looked dubiously at Easton and then at us. "H Uncle Craig told you about the fight," he said reproachfully, "he probably told you the reason... I..."

Just then the telephone pealed loudly, and Easton answered. Ken's face showed relief at the diversion of cross-examining.

"All right. Mr. Kennedy! You're wanted. Somebody, a garage keeper at Smithtown, has been trying to locate you, and the Gerards told him you were here."

I was surprised at the look on Kennedy's face. "Wait for me. I'll be right over. I'm leaving now." Then he turned to us all quickly. "Shut up the place, Easton. I'm going to take you and Ken with me over to Smithtown. I may need you."

IT was perhaps a quarter of an hour when Kennedy's roadster

with us hanging all over it pulled up before the garage. A little

old man ran out to meet us. He was wildly excited.

"I got away and he don't know it!"

"Who doesn't know it?" asked Craig.

"The driver of the yellow racer. He tied me up late last night. I've been hours trying to get free." He rubbed his wrists still. "I wish I'd been like that fellow Houdini I saw once."

"Who are you?"

"Me? I'm Lenihan. I take care of the Jardine country place. The folks are in Europe, so the place is closed up. I live in a little lodge near the garage, up from the entrance gate."

"Then the yellow racer came there? Was it in the garage when you left?"

"Yes, yes. I'd like to catch him, too, trussing me up the way he did. He tied me to a chair ana then locked me in—but I got out. You can't keep a good man down!" His false teeth shook and chattered as he laughed.

"Hop aboard, Lenihan, I'll run you right over to the place."

"Got guns?"

"You bet. Hurry. What did the fellow look like?"

"Tough; one of these city taxi fellers and gun-men."

Kennedy frowned, puzzled at the identification.

Just inside the gate he stopped the car where the road bent around and we proceeded on the thick turf silently toward the lodge and garage. Kennedy circled them so that we could approach under cover of some bushes.

"Two doors—sliding—one padlocked—the other with the lock broken—but closed," he observed.

There was no sound, no sign of activity. Finally we emerged from our screen of bushes. Ken and East started for the door.

"Don't open it! Wait, boys," called Craig.

"Stop!"

Ken laughed with excitement. "Are you scared, Uncle Craig?"

"No, but they know I am after them. That's all."

Along the drive where the grass had evidently been cut had been left a long-handled, wooden rake. Craig took the rake and with the handle, standing several feet to one side, pushed at the sliding door, slowly opening it.

Bang—bang—bang—bang—bang—bang!

We could hear the fusillade of bullets clipping the trees down the drive.

A moment and Kennedy started forward toward the door.

"Craig!" I exclaimed. "Take your own advice!"

"There's no one in there now."

Sure enough he turned in the open doorway unharmed and we followed.

Inside the now empty garage we found an automatic fastened to a sort of cradle of timber, against the rear wall, and an arrangement of cord from the door, around the wall, back to the hair trigger.

"It makes a very serviceable set-gun," observed Craig. "You see, I was expected."

Kennedy was searching about inside the garage. On the floor I noticed some dark spots.

"Grease—new spots," I exclaimed.

"No, the tire tracks of the car are here—and here. Those spots are outside the tire marks, not between them. On both sides, too." Craig was on his knees examining. "Those tire tracks will be like the finger-prints of a criminal!" he cried. "You can identify a car by tire tracks, often. Every worn spot, bruise, imperfection in a tire is just like the loops and whorls and arches on your fingers. We can identify that car—if we can ever get up to it."

"But those spots..."

"Why, they came here to give the yellow racer a quick coat of camouflage—some of that rapid drying auto paint. You'll find it a gray racer, now!"

"Yes, yes; it was a wonderful car," volunteered Lenihan.

UNDER Kennedy's questioning it developed that Lenihan had had

a glimpse of it. He told that the yellow racer had been equipped

with wireless apparatus carried under the extra rear scat that

was closed down when driving. From his description we decided it

must have been one of those field sets that could send probably

up to twenty-five miles under good conditions.

"I wonder who operates it?" I asked, thinking back over last night. "Jack Curtis—what docs he know? Glenn Buckley—could he? I'm just considering possibilities."

"I don't know about Jack," answered Easton. "But of course it was Glenn who got the Gerards to put in the wireless outfit there. Finally he had Professor Vario from the Radio Central come to help him install it. At least that's what Glenn said. The truth is, of course, that Professor Vario really had to do all the work. Glenn just messes around with radio. He has acquired a vocabulary, the radio lingo, but that's about all. When it comes to doing anything, he's a child."

It came to this. The yellow racer, now the gray racer, and the gang were gone. This had been only one of the places used in an emergency. Where had they fled? Where next would they strike?

They let me drive back. Craig and Easton wanted Ken to talk about the fight.

"Fighting is bad business, Ken," began Easton casually after a bit. "You didn't have to wait on the beach for Hank. It wasn't exactly necessary."

"When a fellow turns a hose on you, and—" Ken stopped.

"And what?" urged Craig.

"Insults you," Ken finished hastily. "I'd lick him for that—and so would you, East."

"What did he say?"

"Called me a name." The answer sounded weak even to Ken.

It was Easton who added the last straw. "What did he call you, Ken? You showed more restraint than that in camp two years ago."

The boy sat silent, troubled. He hunched his shoulder up and bit his lip.

"Tell me, Ken. I want to be a true friend. Let me." Easton put his hand on Ken's shoulder. "Spill it, Ken. Come clean. Maybe we can help.

"Oh, East... it isn't about myself. That's why I act so stubborn over it."

"Is it about Vira?" cut in Craig quickly.

Ken startled. "Yes, Vira—and Ruth." He paused. "I had to fight to keep that mucker from telling lies on my sister."

"Lies?" Craig repeated. "Yes, lies—about Ruth. I don't believe him. That kid is everything that a scout should not be!"

"What did he say about the girls?" urged Craig.

Ken did not hesitate now that he had made the decision to make a clean breast of it.

"Hank Hawkins knew about the robbery, of course. He had heard of it. He wanted to find out more, pump me, and when I wouldn't tell he sneered at me and said,' Do you think it was an inside job?' It made me mad. I didn't like the way he said it and I asked him what he meant by that. Then he spilled that his father and mother had seen Vira. Rae, Glenn, Jack Curtis—and Ruth—at the races at Belmont Park. I s'pose... there wasn't anything wrong in that." He hesitated doubtfully.

"Well, Ken," encouraged Craig, "at least you see what evil does. You can't tell how far it may spread, where it will lead you next, what it will get you into."

"Anyhow," resumed Ken, "that's what I told him. 'What's wrong in that?' Then he hollered back at me, 'And they lost money, too—a lot of money—betting on the races. What was I to say? I shouted back,11 don't believe it!' 'Maybe,' he says, 'they needed some money to pay their racing debts.' Well, that was too much. I waded in to make him eat those words... He ate 'cm I No one is going to call my sister a thief—and get away with it! Those others might have bet—but I don't believe Ruth did!"

At last I had heard what I had expected, the truth about the fight. I knew there had been something Quixotic back of it. From what I heard, I could not help thinking of Hank Hawkins, "the kid who is everything a scout should not be," like the Artful Dodger in "Oliver Twist."

Hank's insinuations made me think of this story of his father and mother having seen the young people betting at the races at Belmont Park. "And they lost, too—a lot of money!" I thought of the Vira insinuation; also of his attempt to involve Ruth Adams with them. That was what had really made Ken fight—for his sister. But were all the others in it, too? Did they really lose? What might that attempt to copy sporty high life have started?

Ken volunteered: "Dick had heard it all from Hank before, too; so it wasn't new to me."

"Why didn't Dick tell?"

"No one asked him," came Ken's quick answer. "He wouldn't squeal on Vira, anyhow. Besides, his father always says: 'Little boys should be seen and not heard!'"

Kennedy shook his head. I knew why. It was more of Mr. Gerard's old-fashioned false philosophy about boys. Mrs. Gerard understood boys better. But Mr. Gerard had forgotten. A course in scoutmaster training would have done him good. Craig said nothing to lessen Ken's respect. Mr. Gerard was a fine man. I felt sure that before they got through Ken and Dick would teach the great corporation attorney something. "Where is Dick?" asked Kennedy. "Getting the goods on Hank Hawkins!"

"Goods? What goods? What do you mean?"

"Why, that's just it You see, Hank Hawkins has suddenly come into some money—money enough to buy a radio set up in the village that Dick had his eye on. And then we heard that he is looking at looker's flivver, second hand, for sale for $160. He says he's going to buy it, asked Mr. Tooker to hold it a couple of days, showed some money and gave a deposit of fifteen dollars on it... Now where did he get that money? That's what Dick wanted to find out."

"But where is Dick? Where would you look for him now?"

"At our camp, now, I s'pose, on the shore, where we sleep out almost every night."

"We must see Dick," decided Craig, waving to me to keep on the road back to Gerards'.

WE were not many minutes in returning to the Gerard place.

Reporters were all over it now. Belle Balcom, who wrote the

"sob-sister" stuff for the Star, complained to me that

these were very elusive young people. She could not find

them—Vira, Glenn, Ruth, Rae, Jack Curtis. They were all

keeping out of the way; their excuse was they didn't want their

names in the paper. I wondered whether it was a conspiracy of

silence.

Where was Dick, anyhow? He was not about the house. No one had seen Dick come back since he left early in the morning. In fact, I fancied that for some reason there was a spirit of anxiety that brooded over things. Even the servants about the place seemed worried about it They loved the boy.

With Ken we hurried down to the Gerard shore on the bay. The estate stretched from the sound to the bay. Through a lane of beautiful old trees and past green lawns we followed to a sandy white beach.

Down along this shore the boys had their own camp, an army tent, two cots, with netting over them, camp-table, folding-chairs. In front was a fireplace they had built of beach stones, a huge pot and cooking utensils.

But there was no evidence of Dick about. The tent opening was flapping idly in the breeze.

"He isn't in the sail-boat, either," muttered Ken.

Up the shore we heard a yelp.

It was Laddie, Ken's collie, dripping wet, panting, tongue out.

As Laddie came up, he jumped up on Ken, tried to grab his coat in his teeth in his joy, and pulled it. Then he ran off a bit ahead, jumped and barked.

"Down, Laddie, charge!" ordered Ken.

But Laddie in his exuberance wouldn't. Again he pulled at Ken's coat. Again he ran ahead, jumping and barking.

"Just a minute, Ken," interposed Craig. "He has something to tell!"

Craig started after Laddie. With a yelp of delight as Craig followed him it seemed as if the dog were saying, "Attaboy! This man understands me!"

Along the shore, down the beach, Laddie scampered.

Kennedy paused. There were the prints of a boy's feet in the wet sand—also the tracks of a dog.

"Dick and Laddie!" exclaimed Ken. "But whose are these?" asked Kennedy. He was pointing to parallel tracks of the feet of a man and a girl.

We followed them, down to the water's edge, or where it had been. There were marks where a boat had been beached, marks left as the tide went out.

"Look!" exclaimed Ken keenly.

Here was a long scratch in the sand, as with a foot, and at the end two wings, as if to make of it an arrow—pointing west!

Then along the shore, further to the west, toward the city, we came on prints of the dog alone, going up, the other way.

"Laddie cannot talk but the tracks talk for him," cried Craig. "They took Laddie off with Dick... Laddie jumped overboard, either on his own or on Dick's order... came back to tell us!"

Craig considered a moment. "Ken—run up to the house, ask the cook if she has any paraffin—you know—the cakes they melt and pour over the tops of jelly in jelly glasses."

Ken took it at the scout's pace—running and walking alternately. It was uphill so he ran twelve and walked about twenty paces. He was back in less than five minutes, in an incredibly short time, reversing it, running twenty-five and walking twelve downhill, and not a bit blown by it.

Over the fire he had kindled, in the pot Craig melted all the paraffin. Then he hurried down the shore with the molten wax.

"I want to do this before the tide comes in. Those footprints in the wet sand are like molds."

He poured the wax into one print of the man's foot. The walls broke and caved. He chose another. This time it held and he picked up a sandy hut accurate reproduction of the sole of a man's shoe, even to the marks of the rubber heel.

Next he tried the prints of the girl. This proved easier, for he had selected one that was sharper and not dried out at all.

Ken was silent I glanced at him when he thought no one was looking. He was tracing with his tanned fingers one of the prints of his friend's foot There were tears gathering in the corners of Ken's eyes. He realized it, straightened, then leaned over quickly to Laddie and wiped his face on the dog's silky fur that was drying. He saw me looking as he turned with clenched fists. "Mr. Jameson, I believe Hank Hawkins knows something about this!"

Laddie saw us all straining our eyes scanning the water with nothing in sight. Suddenly Laddie sat down on his haunches and howled dismally, mournfully.

Ken gulped, as he patted the dog's head. "Uncle Craig, he's like me. He misses Dick."

A host of questions tumbled over each other in our anxious minds. Who was the head of this gang? Who were in it? Where were they now? Above all, where was Dick?

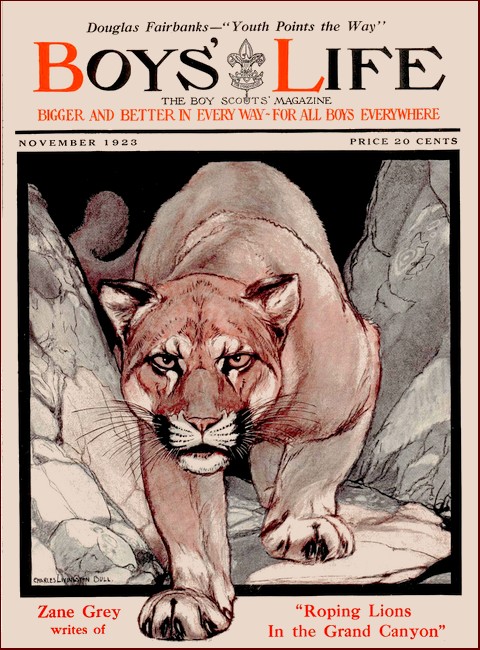

Boys' Life's, November 1923,

with Part II of "Craig Kennedy, Radio Detective"

OUT of breath, bare-headed, running frantically down the little path through the woods, a short cut to the beach from the house, Mrs. Gerard made her appearance. "Is it true, Mr. Kennedy, what Walker just told me?"

Her eyes were pleading for a denial. "It can't be! Why should they take Dick away?"

Her lips trembled pitifully. But her searching glance at Craig's face offered no encouragement. She sank down hopelessly on a big boulder on the beach and vainly strained her eyes seaward for some sight of Dick. Tears were now streaming down her cheeks.

Cupping her hands suddenly about her lips she called. "Dick! Dick!"

The cliffs in the back echoed it with a hollow, desolate sound. She clasped her hands, rose in desperation. "I can't stand it! Oh, my boy—my baby!"

She turned as she felt a light hand on her arm. Moving quietly over the sand Ken had come up to his pal's mother. "Mrs. Gerard," he said bravely, "I—I feel awful, too!" Then he straightened his slender shoulders as he involuntarily put his hand in hers. "I am going to get him back for you... Uncle Craig and I will get him!"

Laddie seemed to feel Ken's determination. He leaped about wildly. The intelligent animal seemed to fathom the trouble among his best friends. Laddie intended to help, too.

THERE are some beautiful things in this old world that make us

all nobler and more gentle, things tinged with the glow of the

spiritual. One of them is a mother's brave, sad smile when she

tries to keep her courage up in the illness, or death, or loss of

a beloved child. It was in such a rarely beautiful moment that

glowed the understanding heart of this mother. Never was an offer

of help such as that given by Ken more fully appreciated than

when Mrs. Gerard gave him that sweetly troubled smile and

squeezed his hand. Her boy was gone. She realized the value of

the boy before her.

Again she turned to Craig. "Mr. Kennedy, do you suppose it has anything to do with the disappearance of the jewels?"

"I wouldn't be surprised if your son had come upon some information that made his presence here dangerous to the gang," answered Craig, doing his best to reassure her.

"Do you suppose they will—take care of him?" she asked anxiously.

"There are a woman's footprints in the sand, too," I ventured. "She will probably have more thought for him than if he had been carried off just by men."

Her face lighted with a faint ray of hope. "You don't suppose they will try to keep him—teach him to steal?"

Ken drew himself up. "I know Dick would never be a thief. He is the whitest pal I ever knew. Those Fagins'll never win Dick!"

We could now hear the hum of a motor on the drive up by the house. "Maybe someone has some news," cried Mrs. Gerard.

Soon we caught sight of Craig's sister, Mrs. Adams, followed by the Gerard chauffeur, Walker, coming toward us. The two mothers exchanged a sympathetic greeting. There was a touch of compassion in Coralie Adams's manner.

"Walker just told me, Christine, about Dick. I am so sorry for you. Don't hesitate to call on us for help—no matter how big or how trivial a thing it is we can do... I came over for Ruth. Have you seen her?"

Craig spoke up. "She isn't here, Coralie."

"Well, where is Vira?" It recalled her own daughter to Mrs. Gerard. "I've been so upset over Dick I haven't thought of Vira. It's strange she isn't with me. Why doesn't she come to help me?"

"Mrs. Gerard," Walker touched his cap. "Miss Vira went out in her roadster. She was mighty nervous, I thought, ma'am, over something. She spoke sharply to me. It didn't seem like Miss Vira."

"When did she go?" asked Craig.

"Right after your first visit this morning, sir."

"Did Vira go alone?" questioned Mrs. Gerard.

"Yes, ma'am. Just a short time after she left Miss Ruth drove up in her little car. When she found that Miss Vira was gone she didn't wait long. She drove off, too. I thought she was nervous, too. I haven't seen them or the cars since."

Walker dropped back, as Coralie Adams and Christine Gerard exchanged glances. Craig drew them aside and lowered his voice.

"Have you heard what Hank Hawkins told Ken about Ruth, Vira and Glenn? No?" He dropped his voice even lower so no one could hear and gossip. "It seems his mother and father saw them lose money betting on the races, at least that's what Hank says. He says they seemed worried over the losses, and then hinted to Ken, here, that the robbery was an inside job for that reason. That was what the fight was about, really. Ken wouldn't believe that Ruth could be so foolish. And I think it's something about it all that Dick was trying to find out."

"I am frantic!" exclaimed Mrs. Gerard. "As far as mine are concerned, better to lose the jewels a hundred times than—" She stopped. Even the sound of the words was ugly. "Oh, Vira!... I didn't think she was much more than a child until the other day." She was dabbing at her eyes with her lace handkerchief. "But she has been going to all sorts of dances and...."

"What sort of dances?"

"The cabarets in the city—and roadhouses out here."

Craig involuntarily elevated his eyebrows.

"Oh," she wailed, "it's not a question of morals—alone. After all, sometimes common sense and foolishness are fair equivalents for right and wrong."

Craig looked up quickly, genuinely surprised at this bit of modern worldly wisdom.

"I mean," she corrected, "when girls—and boys—do stupid, dangerous things trouble follows... if not at once, a bit later. I'm afraid this is a case of it." Kennedy was doing his best to soothe both mothers. "If we were only in the city," muttered Easton, "we could at least alarm the police—get the Bureau of Missing Persons."

Craig smiled patiently. "You forget the Radio Central at Rock Ledge—and the telephone. I can do all that here, too. I can call up and get the police of the country here by telephone. Besides, from Rock Ledge I can alarm the police of the world. Every ship, every amateur station on any wave length—the wireless of the world—are open to me there..."

"That's it!" cried Ken. "Let me go with you!"

"Broadcasting by the police for stolen cars, for missing people, in crimes of all sorts is getting to be a greater success, every day," added Craig, trying to infuse enthusiasm and hope.

"Yes," exclaimed Easton. "I'm a dub. In my own line, too! Never thought of Rock Ledge broadcasting station. Of course. Why, XYXZ can do it!"

WE left Mrs. Gerard and Ken's mother together in mutual

anxiety about their daughters.

On the way to Rock Ledge we passed the Hawkins estate. "I really wanted to quiz that young man," observed Craig, "to find out if possible just how much he knows."

As we neared the entrance drive we could see a flivver stalled near the gate.

"That's Hank, now," exclaimed Ken. "There he is tinkering with a tire." He smiled. "They're not demountable rims, anyhow!"

A hot, perspiring boy stood up as he heard our motor pull up. He was very blond, the type whose eyebrows and eyelashes and hair are all of the same lightish hue. His face was flushed from his work and now he scowled as he recognized Ken. "What're you hangin' 'round here for?" he demanded. "Can't a fellow look at you, Hank?" countered Ken. "Just because we had a fight doesn't say that I keep on holding anything against you. That's all done and settled."

"Settled?" Hank smiled diffidently. "Not if I know it."

"Don't be a kid, Hank. Forget it. That your new car?"

Hank's face nevertheless was sullen. "I can't say I blame you for keeping me off—if you can make money enough to get a flivver as good as this. What did they make you do for the money? Aren't they coming back? Isn't there a chance for a fellow?"

"None of your business, Ken Adams, see? I worked for that boat—the 'Scooter'—harder'n you ever worked."

There was a pause in the verbal hostilities.

"Heard any more about the Gerard robbery?" asked Craig, casually looking over his own motor. "What made you think it was an inside job?"

Hank looked at Ken scornfully. "Been peaching, eh?"

"Not exactly. I just told the folks what you said about Vira, Ruth and the rest, that they lost a good deal of money betting on the races and about the hold-up and paying for gambling debts."

"Well, is it so? Did they?"

Craig saw another fight brewing. "Well," he cut in, "it takes money to buy automobiles as well as pay gambling debts."

"Yes," shot back Hank as if prepared, "and I have money in the bank. I oughtn't to have trouble getting credit. Besides I paid my first instalment—and Dad will see that Tooker gets the rest when he comes home. There, that's where I got my money!"

All the time I couldn't help the feeling that Hank was precocious, that he was proving a mental alibi, that it was vain to seek the truth out of this boy in a hurry. There was more immediate business before us and Craig left Hank to a later time.

AT the great Rock Ledge station, we at length found ourselves

in a small room, quite plain except for the draperies that were

artistically arranged to hide the bare walls. There were a few

plants and flowers about, also. At one end stood a beautiful

reproducing piano. Some of the best known artists had played on

it actually. All had played on it through the perforated paper

rolls. There were phonographs of all the standard well-known

makes and an automatic organ. A small table with a silk-shaded

lamp added a touch of hominess. There were a few, not many, deep

easy chairs.

But the most important piece of furniture, the thing that impressed Ken more than anything else on his first visit to a broadcasting studio, was the cabinet containing little lamps and many switches with a great deal of wiring, comprising what is known as the modulating equipment. It was a wooden framework covered with copper screening to prevent the delicate apparatus from being disturbed by electrical and magnetic influences within the room itself. Various conductors connecting up the cabinet and the transmitter were sheathed in beautiful, bright and neatly woven copper sleeves or tubes for the same reason.

"There's the little transmitter, mounted on that portable stand," an attendant pointed out to Ken as the boy took it all in. "The radiophone transmitter, proper, is located in a little room under the roof over our heads. There are a couple of operators, for it contains all the elements of actual transmission. When this studio is to broadcast, it is connected by this switch over here with the radio station upstairs. Here's a wire telephone to it, too."

Kennedy hardly needed to be told the intricacies himself. It was an old story to him. He had seen it all often before, the radio telephone transmitter upstairs, which consisted of a cabinet closed in by iron grill-work to prevent damage to the delicate vacuum tubes, five of them for the normal operation. At the extreme end of a long operating desk or table was the transmitter. On the table were ordinary telephone instruments, radio apparatus, a receiving set with amplifiers, telephone head sets and a loud speaking device by which the operators could hear the speech or music rendered downstairs, only here actuated by the long-distance receiving set.

"Here's the thing you talk into, Ken, the phonetron, the 'dish-basin,' 'the barrel,' as some people call it."

The attendant was looking at his watch and at a schedule to determine other programs on the wave-length, and when it would be possible to broadcast the alarm.

Ken looked curiously at the little hole in the cylinder dangling from an adjustable stand in front of Craig.

"Is it about the right height?" asked the careful attendant "You prefer to stand? All right. How's that? Now, don't forget—talk directly into that little hole—good and loud. Keep up your voice, sir. About three inches away, from the transmitter. There. Now, wait until I tell you."

The minutes seemed an eternity. Would it never be possible for Kennedy to soar on wings of wireless to the rescue of Dick?

"All set?... Let's go!"

"Broadcasting a general alarm to all police departments and radio owners." Kennedy repeated it, then slowly went on: "Look out for Dick Gerard, fourteen years old, kidnapped some time this morning in a former sea patrol boat, 'The Scooter,' off Nonowantuc, Long Island. If you have any information either as to the boy or the boat please communicate with Craig Kennedy, the Nonowantuc Club, Nonowantuc, Long Island."

Slowly and distinctly Craig launched into a brief description of the sub-chaser followed by a detailed description of Dick, and ending with a repetition of his name and address at the Club.

Kennedy finished. There was a silence in the room. I looked about stupidly. Not that I could have expected anything else than silence. But it was weird, uncanny. Craig had spoken to a mute, invisible audience. Was it one, a hundred, a thousand, a hundred thousand? No one could do more than guess. Above all, would it reach the right one? Somewhere, someone had this information without doubt.

I could not get out of my mind an impression similar to one I had had in a motion-picture studio. I suppose in one case it is one-sided acting, pantomime; in the other one-sided speaking, monologue. The audience was somewhere else. Anyhow, the same motto applied to both: "Get it across!" It was a new art, scarcely a couple of years old then, an old story to Kennedy, perhaps, but full of interest to me as a reporter.

"Broadcasting as a business will settle down some day, I suppose. This Radio Central service is really a public service. But just now it's like the talking-machine companies selling you an instrument—and giving away records, if you can imagine that!"

We turned at the voice in the door. Professor Vario had just heard we were there and had come in. Kennedy and Easton nodded.

"Sometimes," went on Vario with a smile, "the radio is a temperamental thing—that is, if you can say inanimate things are temperamental. There's a natural depravity about it. But I think conditions are fine, just now. I mean to say that it has worked best when nobody was around to appreciate it and often not so good when it's on parade. The radiophone with its delicate tubes and controls sometimes lies down on the job at the wrong moment. But we don't have much trouble of that sort here."

"STEP on the gas, Uncle Craig! Let her out a bit!" Ken urged

as we started back in Craig's car from the Radio Central at Rock

Ledge. "There isn't much traffic."

"All right, Ken. I want to get back to get the answers to my radio appeal."

Craig indulged Ken's intense desire for a burst of speed and we were soon whizzing along the turnpike back to the Club. I enjoyed the look of supreme satisfaction on the boy's face as the wind whipped the color to his cheeks and his blue eyes sparkled with that ancient desire to win as we passed one after another of the few cars on the road.

Suddenly Ken yelled. "Stop! Stop! Up that road! Didn't you see?"

Craig jammed on the brakes at the expense of brakebands and tires. "What's the matter?"

Ken laughed with excitement. "Did you see that road we just passed? I think I saw Vira's roadster down there."

"Yes?" Craig had a wholesome opinion of Ken's keen sense of observation. He shot into reverse and back we went to the little side road of loose brown soil and sand, not much better than a lane.

"Yes—it is! I know it! That's her license number. Dick and I have seen that car so much I remember it. Let's go down there and see Vira, see who's with her. She might know something of Dick."

"If we go down there," Craig said slowly, "Vira and whoever is with her are going to shut right up." He looked at the boy. "Ken, I'm going to let you play detective. Use your eyes and ears, now—not your tongue!"

Ken turned seriously down the lane and we returned to the club. Among a load of mail for Craig was a telegram:

YOUR MESSAGE WAS GOOD AND CLEAR. BUT WHY DID YOU SUDDENLY STOP WHEN YOU BEGAN TO TELL US YOUR OWN SUSPICIONS AND CLUES?

P.S. I DON'T APPROVE OF PHONOGRAPH SELECTIONS IN RADIO BROADCASTING ANYHOW. I CAN BUY RECORDS.

K 903—DEER PARK, LONG ISLAND.

"I like your radio fraternity," I commented. "They certainly do take an interest in one another and go out of the way to show it. And they're brutally frank."

Easton laughed. "You should see my mail! If they don't like a thing they almost take it as a personal insult."

"There's a catch in it somewhere," considered Craig seriously. "What does he mean? I didn't stop. I went right on to the end. And the phonograph record. That must have been interference!"

We had scarcely finished lunch at a secluded end of the porch when Ken hurried in, hot, tired, but with the zeal of one bearing news.

"Was Vira alone?" demanded Easton.

"With Glenn at first. They were both so anxious they could hardly sit still."

"Did you find out what was the matter?" asked Craig.

"I didn't ask, directly, of course. But I asked 'em other questions that might lead to it. They told me little boys shouldn't be so inquisitive. But, say, when I told Vira about Dick, she was wild. She cried as if her heart would break."

"What did you do then, Ken?" Craig prompted.

"I sneaked around back and came into a little rear entry where I could hear the voices of Vira and Glenn. Then I heard my sister Ruth drive up."

"Ruth!" exclaimed Easton.

"Yes. They expected her, too."

"How do you know that?"

"Oh, by what they said. 'Did you get it, Ruth?' they both asked together. 'Will he give it to you?'"

"Who? What?" asked Kennedy.

Ken shrugged, disappointed. "I didn't have time to find out. Ruth laughed and said, 'Yes.' When they heard that, Vira and Glenn took a few steps, dancing steps, on the floor, they were so happy. But they were all broken up about Dick. I couldn't overhear what it was that Ruth came to tell them about. Another car drove up. Rae Larue and Jack Curtis jumped out and then Ruth and Vira made me sick. They shut up like clams, wouldn't say a thing about what I was there to hear."

"Is that all, Ken?" asked Craig.

"Well, they all seemed uncomfortable there. I heard Rae say to Ruth that she liked the tea room because it was so quiet—no reporters, no photographers, no Uncle Craig to ask questions! They seemed glad, too, that there was a wireless. I saw Jack Curtis draw a curtain in front of a very complete set, with the loud speaker. He adjusted and tuned and twirled knobs, watching the dials and indicators until at last he had it. He seemed just to be seeing if it was working. Anyhow it was right after that they saw me listening—and I beat it."

"You did mighty well, Ken," encouraged Craig, then to us he added: "These dance places, cabarets, roadhouses have given a new twist to the case."

A boy appeared with an anonymous telegram from someone on a cruiser, or other motor-boat with a wireless, cruising along the north shore.

The burden of his message was that he had seen a boat answering the description of the Scooter putting into the harbor west of Eaton's Light, headed toward the "Binnacle," an inn on the shore of the inner harbor.

Craig decided to investigate this tip.

The Binnacle down along the shore was a queer old roadhouse furnished like a huge cabin to suggest an old clipper ship. Outside it displayed the usual sign: "Radio Concerts Daily." There was wireless at the Binnacle and broadcasted music. An orchestra in New York was broadcasting.

"There are other harbors inside those two headlands, you know," urged Easton, "one to the west, Lloyd's, and Duck Harbor to the east."

Suddenly, through the windows, the orchestra in New York seemed interrupted to us... Buzz-Oz... Buzz-Oz-Oz...

A shade of annoyance passed over Eastern's face. B-z-z... dot—dash—dot—dot—dash. Easton scowled intently. By habit he was reading the Morse.

"Did you get that?" he exclaimed.

Kennedy nodded. "Yes... Paging Miss Vira Gerard... Meet me at the Binnacle to-night in the Radio Room.... No name." The dots and dashes ceased. B-zzzzzzz... buzz... buzz... The orchestra was on again.

"The radio room, eh?" muttered Craig. "Let's look about."

Casually, like ordinary curiosity seekers, Kennedy and the rest of us mounted some steps to the second floor. Down the hall through a door ajar we could see a deserted private dining room. Kennedy walked in.

As he looked about as interested as if he planned to give a banquet there, Craig opened a cedar chest between two closet doors. He beckoned to Easton.

"A radio frequency amplifier," exclaimed Easton, "all wired up, too!"

Craig hastily closed the chest upon the complete paraphernalia, thought a moment, then stood up on the chest, running his finger along the picture moulding that circuited the room. He blew the dust from his fingers and wiped them on his handkerchief. . "About forty feet of wire placed behind the picture moulding about the room where it's out of sight... The receiving outfit in a cedar chest where no one can see it... Humph!"

In his interest Easton took another look in the chest. "Here's a camera," he whispered.

Kennedy turned it up. The number "5" showed. Deftly Craig unloaded it and dropped the roll of film into his pocket and the box back in the chest.

"That's all very interesting," he remarked under his voice, "and there's something mighty mysterious about this place and that hidden radio set, but just shut up that chest again, Easton, before we have fifteen men on a couple of dead men's chests!"

FROM the radio room a splendid view of the bay, through the

headlands and out into the Sound, could be had. Ken was looking

out of the window. Only the harbor in front of us could be seen.

The two harbors on either side were across necks of land with

hills.

Ken was thinking only of Dick. "Uncle Craig!" he suddenly exclaimed in an excited whisper. "There's a yacht tender—coming up to the dock! It looks familiar, like the tender the 'Scooter' carried. It is, too. Two sailors in it, one at the engine, the other at the wheel—and a boy with them! I'll bet—it's Dick! They're taking him ashore!"

Just for a fraction of an instant Kennedy looked. What were they doing that for? Was the chase on water getting too hot? Had it been to throw us off?

"Hurry!" he ordered. "Let's get down there to that dock—not along the road; they'll see us. Take it along that path in the shrubbery. We'll get them!"

Quickly and unobserved we got out of the Binnacle, crept down the path to cut them off, get Dick.

They had come just up to the dock. One sailor was on the float, the other still at the engine. There was a shout and an oath from the men, hardened, husky old salts.

Dick had leaped overboard the moment their attention was relaxed in docking the tender!

We stopped short, watching Dick as he struck out diagonally down toward the shore. Dick was a good swimmer, too. Hand over hand he was making a swift crawl for it.

The sailor on the dock started down to the shore while the man in the tender spun his engine and shot out to intercept Dick or at least cut him off and force him to land.

Instead of down the dock we turned along the sea wall bulkhead from which the dock jutted out, keeping between the boy and the sailor ashore.

The tender put in, beached, and the other sailor leaped out just as the boy, wet and bedraggled, struggled up the sand.

"Dick! Oh, Dick!" called Ken.

But Dick had time for no more than to see and hear. The sailor was too close to him. He started to run in the only direction possible, away from us.

Easton turned to grapple the man from the dock, who was pursuing. It had been three of us to two of them. Now as Craig and I pressed on after the sailor and Dick, it was two to one. It looked easy.

A shot whizzed over our heads, another pinged in the sand. Along the road back of us, on the shore from the dock, came the sudden hum and roar of a motor, cut-out open.

"The gray racer!" gasped Ken, as we ran.

It stopped, engine still turning over. Other shots fell about us, but wide. I took one hasty look over my shoulder as we ran. Two strong-arm men had leaped out of the racer. I thought. Now it was four to three, just a bit against us. I prayed that they had emptied their guns, but they were too careful for that.

An instant and the two thugs had toppled Easton overboard in the water at the sea wall as the sailor released himself. It was now four of them against two of us, not counting Ken.

Fearless of shots Kennedy pressed on and I followed.

Suddenly there was what sounded like a volley back of us. I turned. It was the gray racer, back-firing.

Off the road it swooped, careening madly over the sand, until it hit on the hard sand where the tide had left it wet. Then with rapidly gathering speed it bore down at terrific racing pace. Kennedy stopped short, drew his automatic and I did the same. I think we got one of them in the arm, but unfortunately it wasn't the driver. On he sped past. I turned toward the sailor ahead with my last shot. He had caught up with Dick running exhausted in his wet clothes. As I raised my gat, he swung the boy about as a shield between him and me. I moved my arm and sent the bullet crashing after the racer endeavoring to puncture a rear tire. The bullet caromed off the gray body as it sped on.

Slowing up an instant the gray car picked up the sailor with Dick pinioned to him, then with gathering speed made for a point where the road again approached the beach.

I turned with Craig and ran back, but only in time to see the other sailor shoving off the tender and circling away a couple of hundred feet out to sea.

"THAT Radio Room is some kind of den with all that secret

installation—for somebody," remarked Kennedy.

"Who is it?" asked Easton, drying out in the sun. "We'd better go up and find out."

Kennedy shook his head. "They wouldn't tell. And they would tip off the gang. We'd get nothing. No. We've just simply got to hear what is said in this Radio Room to-night at the Binnacle."

"How?" Ken asked it eagerly. I think he hoped that Craig would detail him for more detective work.

"My wireless dictograph!" exclaimed Easton. "Can't we use that?"

"Your wireless dictograph?" repeated Craig. "Bully! Just the thing. We can't be there. There's no place to which we could string a dictograph wire without being seen, either. Where is the little mechanical eavesdropper?"

"In my laboratory." Easton's face fell.

But Craig looked at his watch. It took only an instant for him to calculate that there was still time to install it. We were soon on the way back to Nonowantuc.

Easton Evans had done some remarkable things with wireless and he had a wonderful equipment in his boathouse-laboratory. But all the equipment in the world would not have availed him without the hard work he had done, the study, and that spark of inventive genius inherited from his famous father.

"So this is the latest form of the Evans Wireless Dictograph?" complimented Craig, picking up the familiar little round black vulcanized transmitter of the dictograph like that which he had used so many times before on wired machines. "Did you find that my last suggestion about the hook-up worked better, Easton?"

"Much better." Easton was packing the parts as he hastily enumerated them, his sending set, batteries, coils of wire, small portable antenna. The receiving set he left in the laboratory.

UP the road on the way back, passing the Club, we met

Professor Vario going in the other direction. He waved.

"I was coming down to see you, Evans," he explained as we pulled up a moment. "I had a new device of my own I wanted to show you. But, of course, if you're going somewhere..."

"Yes," replied Easton. "I would have liked to see it. What is it?"

"Well, you know so many amateurs have difficulty in finding the wave length of the broadcasting stations," returned Vario hurriedly, with the pride of an inventor himself, "that I have concluded that some simple method of tuning and calibrating the set would clear things up, especially for those who are some distance away from the sending stations. They have weak signals to begin with and must listen in on very nearly the proper tune if they are to get any signals at all."

"I see," nodded Easton, interested but anxious to get along. "For that purpose a wave-meter is needed, eh? It's something for the radio like a pitch pipe for a piano tuner."

"Exactly. Mine is simply a calibrated oscillating circuit and is one of the simplest circuits to build.

"I'll be glad to show it to you, Evans, some other time when you have leisure."

"And I want to see it, too. So long." As we sped along back toward the Binnacle, Easton added, "I didn't want to offend him. Vario's the best radio trouble-finder in the world. If there's anything wrong, hell set it right."

With his usual assurance, Craig sought out the manager of the roadhouse and in a few confident words informed him that he was a representative of the Board of Underwriters come to look over the radio installation as it affected the insurance of the inn to see whether it conformed to the regulations and if any changes were necessary to make it do so.

So we got on the flat part of the roof of the Binnacle to make an inspection of the aerial, the ground, lightning switch and so on.

"Now, we'll have to work quick," urged Craig.

Already he had selected and carried up to the roof the apparatus. First he fished with a line down the chimney until he located which flue it was that went down to the Radio Room below. Then, dangling down, he lowered the dictograph transmitter until it must have hung about a foot from the floor of the hearth back of an iron grill-work which I now recalled under the mantel of the old-fashioned room below. Meanwhile on the flat roof, Easton had been busy placing the sending set.

We pulled up again near the Club. There was a message there from Ken's mother inquiring about him.

"Walter, I think you'd better take Ken to her in the car," decided Craig. "I have a few things to do. I'll see you at our rooms. And you, Easton?"

"I think I'd better go make sure that the receiving end of that dictograph in the laboratory will work right for to-night."

Ken was loathe to leave. "I wonder where Dick is?" he repeated sadly. "Where's the gray racer?"

"Well," reassured Craig, "wherever Dick is, it is not where the gray racer is. Of that you may be pretty sure."

"But they carried him off in it, Uncle Craig."

"And we saw them. Yes. That's just why Dick is probably not with the racer yet. Think a moment, Ken. They knew we knew he was on that boat. So what did they do? They planned to transfer him to land. Now it is reversed. It wouldn't surprise me if he was back on that boat, now."

"But how could they get hold of the boat?"

"How? The racer had a wireless field outfit. The boat has its wireless, has it not?"

IT was some time before I rejoined Kennedy at the Country

Club. Then I found that he had been developing the roll of film

from the camera at the Binnacle.

"What do you see there?" he asked, holding up the strip.

I turned toward the light and looked carefully. "A boat. Looks like one of those scout patrols built for the Government during the war. Why! It must be this 'Scooter'!"

Craig smiled. "This camera was autographic, by the way. The name is written under it, and the date."

"But by whom? Whose writing is it?"

"That's something to find out later. Never mind it now. What is that shore line, do you think? Do you recognize it? Take my magnifying glass."

I studied it intently a few minutes. "It looks like the shore there at the Binnacle."

"That's what I thought. I wanted your opinion. Now look at the next, with the same shore line."

"Why, that's Ruth, Vira, Glenn!" I exclaimed.

"And that other girl is Rae Larue. That fellow back of them is Jack Curtis. I'm going to keep these very carefully—that boat, the shore, the young folks—and the handwriting."

Kennedy said no more and we kept rather quiet until evening when Craig and I rejoined Easton at his laboratory.

Carefully and deftly Easton had begun to tune up his wireless dictograph. He had it arranged so that two or even more could listen in, mindful of the legal requirements for evidence that must be corroborated.

It was rather difficult at first to get the fine adjustment but at last he got it. He looked over at Kennedy and smiled. "Get that?" Craig nodded, and Easton adjusted again.

We all listened for several minutes. Then, at last, we could hear a noise like footsteps. Easton smiled quietly. The dictograph was working!

Through the high resistance phones of the headpiece we now heard voices almost as if from the old-time phonograph. We strained our attention to recognize them. None of us did so and I doubt if Ken could have helped us in that either.

They were men's voices, men of a low cunning apparently, a breed of crooks used by clever criminals who plan and plot and leave the dirty work to such dapper gun-men.

"Did you see the boy yet?"

I started at the words. Did they mean Dick?

"No," came the other voice. "I'm going to see him later, at the house. I guess he's got the info, all right."

It couldn't have been Dick, then. Were we going to hear the plans for another robbery?

"What's it to be? Another dance, a little porch-climbing, a second-story job, what? That last shindig had a kick in it!"

"Naw. The next place is closed up. Ought to be quiet."

"Say, bo, are they sure of this kid that's the gay cat for us?" There was just a trace of anxiety in the tone.

"Yeh—the Chief has him right, see? He'll eat out of his hand. And that lad knows all the rich guys out here, what they have, where they keep it, what their habits are, everything. Say, he is a dozen gossipy old maids rolled into one boy—better than a sewing circle. Funny part is, he's welcome in all their houses. Most of them never know how soon they might need favors from his father!"

"His old man's a banker, ain't he?"

"Sure; and a sporty one, too. Did you know what the Chief has found out?"

"Naw. What?"