RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

Short Stories, 10 October 1936, with "Waters Under the Earth"

Short Stories, November 1951, with "Waters Under the Earth"

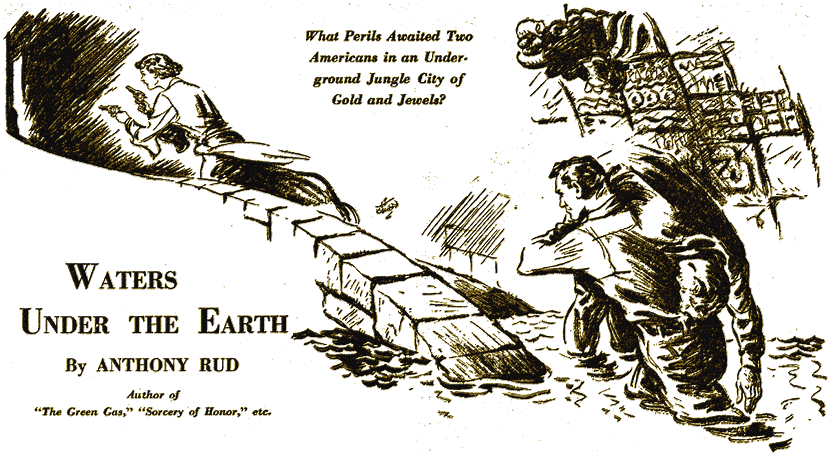

What Perils Awaited Two Americans in an

Underground Jungle City of Gold and Jewels?

THE rude pellet of lead from a gas-pipe gun had done something queer to the kneecap of his left leg. Though the wound had healed, Lawrence Gorman still limped.

He could do his share of ordinary work. But Gorman's work in Yucatan and Quintana Roo had been of the most special nature. When real stress came, the confounded patella slipped out of place. Then Gorman could do nothing but sit and swear.

In the bleak manner of this strange Americano, he made his decision. Monte and jungle had brought him all men ask of adventuring, then taken almost all away—leaving only vengeance, which was bitter in his mouth. That and moderate wealth, for which he had little use.

The Mayas, who worked the great cane and corn plantation around Chichen Itza, now leased by the Carnegie Foundation, respected and loved Gorman as a brother. The Spanish haciendados, who had been forced to give up the peonage systems on their great jeniquén plantations, respected—and hated him. Archaeologists, digging out more than sixty buried cities, fairly swarmed on his trail. Maya Gorman knew more about the old ruins than some of these men ever would learn. But he decided to leave Yucatan, and try American surgery on his injured left leg.

Maya Gorman had no white comrade now. He was lonely. There were scores of chicle-gatherers and untamed Sublevado Mayas sworn to kill him; and alone he could not face the weight of that undying hatred without deeper and deeper gloom of the spirit. He loved this strange, harsh land, centering about the Lake of Bitter Waters, but it seemed that his work was done. The proposal from a wise man in Mexico City that he take Mexican citizenship, and stay on to rule a province, made no appeal at all to a man as thoroughly American as Maya Gorman.

"At forty I feel old and useless," he quietly told the sorrowing Mayas of the Sh'Tol Brothers Lodge—the almost prehistoric secret society to which he belonged. "That may change. I may come back, provided my leg heals satisfactorily—and if I find a young and hopeful comrade with the world before him."

He did not speak the last part aloud.

"Remember us, O wise brother!" said Pedro Ek with husky emotion. Pedro raised the ritual mask from his face, the serpent mask which denoted his rank as commander of the chapter. His seamed face worked, but he said no more. He clasped the tall man's hand in the fashion Gorman had taught them. And that was farewell.

Perhaps the American, who had not set foot in the United States since a few-weeks after that spring day of 1919 when he had returned to Pensacola and resigned from the Naval Air Service, grew a little careless when the low, marshy shore of Yucatan faded away from him to southward. He kept his eyes forward, over the yellow, green, blue waters of the Gulf. He put his cartridge belt, his arm-pit sling, Colt revolver and Colt automatic pistol away in the battered tin trunk, and felt almost as light as a puffball—after fifteen years of wearing weapons constantly.

He was clad now in worn boots, a suit of buff pongee silk, white silk shirt, blue bow tie, and helmet of sola pith. His craggy features were clean shaven. His hair was well cut, though worn long to his ears, Indian fashion. It was streaked with gray if one examined closely, though at a few yards it still looked coal black.

With the deep-layered tan which never would fade, and the black eyes deep-set and narrowed from much looking at far horizons in a parched and sun-drenched land, he could have passed for a real Maya, except for his six feet of height and solid one hundred ninety pounds of bone and muscle Most Mayas scarcely reached his shoulder.

Leaving Progreso for New Orleans suddenly and secretly, Gorman had not been able to obtain passenger accommodations. He found one tub loaded below and on deck with sisal fiber in bales, and named El Tigrillo. That was satire. The little tiger-cat of Yucatan, who lives mostly in the tree-tops, is the jumpiest and most restless creature of the tropics. The freight tub pitched, tossed and seemingly leaped about when there was the slightest ripple on the Gulf.

Gorman was not a good sailor. He slept on deck, even through a two-day rainstorm. The weather did not matter, but his mal de mer was troublesome. He knew, of course, that several of the crew were Yucatan Indians, but paid them no attention. Huddled in his slicker, he concentrated on simply existing, until Louisiana was reached.

Tin trunk on one shoulder, limping a little, Gorman went ashore at the first moment he could descend the gangplank. The sights and smells and sounds of the river, and of the city beyond the levees, held his attention. He did not see the swarthy, stocky little man who lurked behind.

After a short walk he got a cab, stood his trunk on the running board, and directed the taximan to the best hotel. In due course the driver deposited him at the St. Charles, where Gorman registered. After bath, shave, and change of clothing, he was ready to explore the old city which he had known sixteen years before.

That evening he decided on a meal in the old French quarter, after a walk for appetite. He wondered if Papa Antoine's still did business; the old man, of course, being dead now. He was not to find out for several weeks.

On Cartridge Street a big yellow street car bumbled noisily past. Behind Gorman a squat figure flitted from shadow to shadow—and came swiftly while the noise of the car still blunted the quarry's jungle senses. Gorman kept on toward Canal Street, unsuspecting.

"Kukil Kan!" came the hoarse cry of triumphant vengeance, the name of the Serpent god, as the Sublevado Indian priest struck.

Gorman was conscious of searing agony at his left shoulder blade, an overpowering horror of pain that bore him down and smothered his senses as a poncho smothers a fire in grass. He pitched forward to the grass beside the sidewalk, twitched once, and lay still. From his back protruded the strange, wire-wound hilt of a knife.

IN the infirmary they discovered some odd things about Lawrence Gorman. In the first place, he had been stabbed through the lung with a long, keen, tapering blade apparently of glass.

In reality the blade was what Mayans call isltlé, which is a sort of volcanic glass, obsidian. The blade was an ancient sacrificial knife of the Toltec Chanes (ancestors of the Sublevado Mayas). It had been used by one of the ignorant but vengeful priests of these modern Ishmaels, the only branch of the Mayas unconquered by the Spaniards and the Mexicans in the great revolt of 1847.

Gorman's shoulder-blade had diverted the knife from its straight course to his heart. The first four inches of the ten-inch weapon had broken off in the wound, and had to be removed by a surgeon. They saved the knife to show him, in case he fooled them all and recovered.

Around the waist of this bronzed, hard muscled stranger, they found a money belt—and fifty thousand dollars in American bills! The doctors whistled at that, and immediately moved Gorman from the charity ward to the best private room they had. They would treat him skillfully and honestly, but he might as well pay for good accommodations as long as he lasted.

As long as quoted odds against a man are honest odds, the man has a chance.

Perhaps it is only one in one hundred, but it is there to be taken. Gorman took his. He grimly refused to die, and he showed them how a tough human body the consistency of caoutchouc could respond to the will to live.

Not that Gorman feared death any more. Not that he foresaw the adventure that awaited him. It was just sheer virility and inability to surrender.

In three weeks time he was sitting up, propped by pillows, and handling the broken glass knife which so nearly had reached his heart.

The fourth week he demanded a joint specialist, and told that eminent medico about his undependable patella. That meant an operation, but only local anaesthetic. Gorman smoked his own hand-rolled jacoosh—corn-husk cigarettes—and watched, giving no sign that he felt the half-dulled pain.

Three weeks more and he was hobbling. Another week and he moved back to a hotel. And there he got to work on a-discovery that thrilled him to the marrow. A discovery he had made in the infirmary, but which he had guarded and left unsolved while there. Probably no one in all the United States but himself could read the secret he had come upon, but he did not wish to take a chance.

With his room door locked and a chair under the knob, shades drawn at the windows, and electric light blazing, he took up the handle of the knife which so nearly had killed him. Six inches of the obsidian blade remained attached to the hilt and handle.

This latter portion was all in one, shaped almost like a spool, with room for a small hand to clasp its fingers between the butt and the hilt proper. On the butt end was a worn and half-effaced mask in yellow—the conventional representation of the Snake-god which appears everywhere in Mayan carving. The material of the mask was gold, of course, since that was commonest metal the Old Ones possessed.

The entire handle and hilt were built up of gold wire tightly wound. As Gorman had discovered, the outside layer of wire was hammered flat, and stained dark—no doubt with blood of ancient victims—so a casual glance did not reveal the nature of the metal.

Gorman carefully pried up the end, with the blade of a jackknife, and then slowly unwound the flattened wire.

Beneath was wire totally different in appearance. Red-yellow it gleamed under the light. After some searching and probing the American found the hidden end, and using far greater care now, slowly unwound the endless strand.

At irregular intervals, but averaging about six to the inch of fine gold wire, were tight drawn knots like fine nodules. Even hard-bitten Maya Gorman showed excitement in the tenseness of his body. This was the ancient Quiche knot writing, the historical and secret records made by the priests of the Old Ones!

Gorman knew that this would be something of supreme importance; and a hasty study of the first few inches revealed on the outside of the inner layer, without unwinding, had made him gasp. He did not know the whole intricate scheme of the knot-writing, but there were many of its arrangements he had studied out. And if he was not mistaken badly, this was the record of a succession of high priests, locating an inhli (a cenote, or underground pool of fresh water) used not for drinking purposes, but for the hiding of temple treasures!

It was two in the morning before Gorman coiled the precious wire, and wrapped it in a handkerchief, placing the wad in a pouch of his money belt.

"In the possession of the damned Sublevados—and they don't even suspect it!" he whispered grimly. "Now, if I can find me a partner—"

He stripped to the skin, donned the money belt, then pajamas, snicked out the light and climbed into bed. A second later he was up to throw high the window shade and open the window for air. But then he climbed back, to lie through another hour with open eyes, before the excitement faded sufficiently to let him sleep. Treasure! He did not feel so antiquated, after all!

GORMAN did not hurry. Down in Yucatan and Quintana Roo these months from March to June were lurid hell on earth. Ships one hundred miles at sea saw the glow in the sky at night, as though a whole continent was burning.

This was caused by the burning off of the corn and bean plantations of the north part of the peninsula, and then the burning of the thousands of square miles of jeniquén plantations past their bearing period. (The fiber is harvested the third and fifth years, and then the fields are burned.)

Added to the normal tropical heat, these fires raise the temperature of the whole country to a figure unbearable to white men. The archaeologists and consuls flee to the seashore.

Gorman went to Chicago, then New York. He allowed himself time for easy convalescence, seeing shows, eating well of almost forgotten foods, looking up a few men he had known in the Service.

They had all grown old, fat and settled. They remembered him with some difficulty; and the chat of old times, the course in navigation at Boston Tech, the gaining of wings at Pensacola, the convoy service later, all seemed far away and unreal now.

Gorman met no young men who even made him consider. There seemed to be a difference in them nowadays. They lacked vision. He heard nothing except relief jobs and loafing. Where had the old urge toward the far places vanished? These boys, some of whose families were in dire need, still had no genuine idea of trying to do anything!

Gloomier, more saturnine of countenance, Maya Gorman returned to New Orleans. He did not feel at home in the North, and thought possibly he might get himself a little citrus plot in Florida. One tiling was certain: he would not return to Yucatan alone, even if his breath-taking discovery did fit in with an urge he had felt for years—the search for the hidden. Unknown city from which the raiding Sublevado Indians came.

Then one night he found himself at the Arena. There was a mediocre card of three preliminary fights, a semi-final, and then a final between heavies—a second-rater going down, and a second-rater coming up.

Gorman sat unmoved through one four-round loving match, a bloody and earnest, if unskilled, decision bout of lightweights, then a one-sided technical kayo of a middleweight.

It seemed remarkable to Maya Gorman how hard men could try to damage each other with fists, and how little real impression they made. Even that one bout that was stopped because the poorer fighter was groggy and badly cut across his eyebrow, meant nothing. The loser would get a strip of court plaster, a rub-down, and be all ready to dive again inside a week.

Then in thirty seconds after the ring was cleared for the semi-final bout, announced as an eight-rounder to a decision between the Pride of Peoria, Illinois, one Billy Grecco, and Kid Chastang of Montgomery, Alabama, Maya Gorman was to lose for good and all both his gloom and his boredom.

He looked dull-eyed at Billy Grecco, 178 pounds, a swarthy, wide-smiling, well muscled light-heavy, probably experienced to judge by his rather battered features. Then—

Maya Gorman sat suddenly straighter. He stared. The name of Chastang had rung with ghostly familiarity in his ears. Now he knew why! Climbing through the ropes, straightening, rubbing his shoes in resin, smiling quietly out at the crowd in a momentary glance, was the reincarnation of a dead man!

Chastang! Here was blue-eyed, fair-haired Jack Chastang just as he had been at Pensacola! Just as he had been when he taught Gorman to fly! Just as probably had been when he crashed and sank, trying to strafe a sub off Queenstown!

Of course old Jack—let's see, he would have been about forty-eight now, if he'd Jived—was dead long ago, and his bones lost among the wreckage of torpedoed ships and bombed German U-boats... but could this be his son?

Gorman did not know whether or not his instructor had been married, or where he had lived. This extraordinary resemblance, though, could not be missed. When the name was the same, and unusual, it could mean nothing in the world but relationship.

All of a sudden Maya Gorman was a violent partisan. "Know anything about these scrappers?" he asked a red-nosed, bald-headed fat man next on his right.

"Oh, jest a couple dawgs, I reckon, suh," responded the latter with a grimace. "Grecco there done licked Tommy Loughran once. But that was a long time back. He ain't so good now. Good enough to take this ham-an'-beaner one-handed though."

"How much have you got that says so?" asked Gorman flatly. He held out a small roll of bills with a rubber band about them.

"Oh hell, I ain't much of a bettin' man... uh, but I'll risk twenty," decided the red-nosed individual, reaching for a bill-case. His rheumy eyes glinted with sudden greed.

"Want to make it fifty? The man next you can hold the stakes."

"Awright—but you got a bum hoss, strangeh."

"I'll back him," said Gorman tersely. He handed over the fifty, and promptly forgot all about the bet.

THE gong rang. Almost unnoticed, to judge by the noise and shuffling about in the audience, the two boxers came abruptly from their corners. They stopped, feinted, circled warily. Out came a jab, another—smack! smack! from Billy Grecco. Nothing but leather on leather.

Whizz! An overhand right, not a good punch. Kid Chastang missed, skipped back as a counter came, just missing his nose.

The audience was settling down now, though obviously they counted this bout in the bag from the start, and looked only for some blood-spilling and the savage attack from Billy Grecco which would bring the call for curtains. Hoots and derisive advice came from the loud-mouths. Maya Gorman was oblivious. He was seeing a blond, smiling youth he had known and loved with that hero-worship novice airmen gave to their aces, detailed back from the convoy lanes to teach dozens more. This was Jack Chastang—a younger Jack than even Gorman had known. He showed spirit, a willingness to trade punches when the still wary Billy Grecco bored in for a quick rib-tattoo followed by an almost instant clinch.

Chastang was fast. He lacked finish. At long range he broke even or better than that with the chunkier Grecco, but when the latter ducked and came in, the younger fighter took it in midsection. His own blows over Grecco's shoulder, smacking down on the kidneys, might mean something in a fifteen-rounder, but never could win a fight at eight rounds.

First round. There were two red patches the size of a man's palm on Chastang's ribs, as he came back to his corner and sank on the stool, arms along the ropes. No doubt about it; that had been Billy Grecco's round.

Clang! The fighters leaped up—but for several seconds Maya Gorman could not watch.

"You-u!" a man just in front of him was snarling. It was one of the reporters in the press row, and he had hold of Gorman's tense wrist. A fist was clenched at the end of that wrist, and it had been slogging the unoffending reporter between the shoulders. Something about the bleak concentration of this bronzed big man behind him, however, had kept the reporter from physical retaliation.

Gorman hastily apologized. The reporter shrugged, murmuring something about a guy who had to scrap the whole battle he watched, like poor, half-nuts Bat Nelson.... And then a minute later the reporter let out a yip, grabbed his portable, and hastily squeezed in farther down the row, leaving the seat in front of Maya Gorman vacant.

Sometime during the next round Gorman must have noticed the empty seat and climbed over, for he found himself between two growling men who hammered on their chatterboxes and scowled at him. He paid them no attention at all. He was concentrating all his strength of will—insisting telepathically and hypnotically that a slightly inferior fighter rise to the occasion and win!

A knockdown with a four-second count had given Grecco the second round by an even more definite margin. That had been an uppercut on the break-away from clinch, and it jarred Chastang. He looked dazed when he came back to his corner, and there was a trickle of blood from one corner of his mouth. A second emptied a bottle of water over his head, while another smacked a sponge into his mouth.

The minute of rest seemed to help. Chastang met his rushing opponent in the center of the ring, and sent in a straight left to the forehead. His right glove stopped Grecco's counter for the heart. There was a quick, furious rally, with Grecco boring in, and Chastang flinging four glancing uppercuts at the heavy-set fighter's lowered face.

But Grecco had a plan. He was herding the younger man back to a corner, and Chastang touched the ropes before he realized. Then he ducked this way, then in the opposite direction, and charged behind a barrage of rights and lefts. He fought his way out, getting in a jolting right to the forehead and two lefts to the midriff, as Grecco looked up to measure his man.

The intended haymaker slid by, just tipping Chastang's left cheek. And that split second the latter got home his first real marker of the fight. It was a right hook which started the claret from Grecco's left cheekbone and staggered him for an instant.

"They's resin on his gloves!" shouted Grecco distinctly above the growing tumult in the audience. That was untrue of course, just an alibi for the wallop. Resin takes off the skin, especially when a glove is twisted in landing. The referee paid no attention, save to snap something and make the two break from a clinch.

They broke, but now Grecco, possibly believing that he was being fouled, pulled one of the dirty tricks taught in most gyms. Momentarily he got his opponent between himself and the referee, then deliberately shot in two low blows which made Chastang wince and give ground.

Out there Maya Gorman cried out, a snarling, savage cry. And even the press line, on the side that could see, booed.

But the referee could do no more than guess. The fight went on, with Chastang giving ground, and palpably in trouble.

Clang! The gong saved him from a knockdown, possibly a kayo. He limped back to his corner, cheeks drawn with suffering. One of his seconds was vociferously claiming a foul, and the crowd booed. But the referee just looked bored, and waited.

"Stall him next round! Take your time!" came the free advice to Chastang from a press section suddenly friendly. But the young scrapper probably did not hear. He sat totally relaxed until the warning ten-second whistle which heralded the gong.

HE showed good recuperative power, and a shell defense which was a new one on Grecco. Half the round went by, clinch, break, duck, flurry, clinch, before the more experienced man could tap as much as a straight left past that turtle shell of gloves, elbows and arms.

Then the guard shifted, and Chastang led—only to miss and receive two counters in the mouth that shook him. He went back into the shell, but was battered back twice to the ropes. It looked like the end was coming now.

The excellent recuperative power of twenty-two showed itself. Chastang, after giving ground, clinching, and generally acting for thirty seconds like a beaten, wabbling man, snapped out of it and launched a furious attack!

It nearly succeeded in overwhelming the astonished Grecco, who took a thunking right to the midriff and a left hook to the jaw followed by three short punches to the middle, before he could untangle his ideas, guard, and get away from this fellow he had thought ripe for the quietus.

But then it was a ding-dong battle to the gong, with Chastang fading toward the last six seconds. His nose was bleeding when he came back to the corner. Over on the other side Billy Grecco glowered through a right eye swollen and angry, and spat forth something white—a tooth. He looked hurt and infuriated, and was just that. If he could do it, he'd kill Chastang next round!

For ten or twelve seconds, though, that fifth round was an example of anger thwarting ability. Grecco missed and missed, and began to breathe gustily. Then a bit of sense came back to him, and the next minute had almost no action. A lull had come, with Chastang looking arm-weary, ready to clinch, and Grecco deciding to wait for the next round for his kayo bid.

Decisions like that always are subject to change, though. Chastang tried a flurry of infighting, and came out second best. It was guessed by many in the audience to be his last bid for victory. Maya Gorman frowned as he saw the lad's shoulders droop, his whole attitude seeming to say. "I've done my best. Now I'll just hold him off the rest of the way." Which is just acknowledgment of defeat.

Grecco sensed that immediately. He waded in, but more craftily now, and Chastang found immediately that the chunkier fighter was not going to be balked again by mere turtle-shell covering up. Even to keep from sudden demolition, he had to fight.

Grecco came, a hurtling mass of hate. He charged in, boring deep with staccato punches that traveled only inches but held all the strength and snap of trained forearms and wrists.

Chastang evaded, sidestepping as if he had been a matador and Grecco a maddened bull. But the bull in this case could turn as swiftly, and fight with a mad lust of unleashed passion—still controlled by an experienced brain, however. Maya Gorman crowded forward until his eyes were level with the floor of the ring. His man—Jack's son—was not quite good enough, unless a miracle happened. He was being outgeneraled and outfought, though he had shown a willing spirit and considerable ability.

"Slip one through. Kid!" gritted Gorman, but no one could hear the words in that tone, of course.

Chastang threw a wild haymaker which missed by a foot. Grecco came in. He heeled a forbidden rabbit punch to the back of the younger fighter's neck, rammed Chastang's cheek with his elbow, and then brought up his knee in a clinch.

If the referee saw these fouls he made no sign, but the audience went crazy. Booing, yelling, they were all for Chastang—but it did not seem he could come up to scratch. Covering up, he was buffeted back, back, until the ropes touched him and went taut under the weight of the solid punches Grecco was serving into gloves, elbows and parts of the intervening body.

The ropes began to close on Chastang, to slip up on his shoulders, to break the muscles tension of his knees at the back.

It all happened in a split second. He ducked, and tried to charge through out of danger. A short hook found his chin and he spun sidewise, falling with one arm over the second rope. The referee herded Grecco toward a neutral corner. One... two... three...

Clang! The gong saved Chastang, but for what? His seconds had to lift him by the armpits and drag him to his chair. Once there he shivered, and seemed to catch hold of his dazed senses somewhat. But could he revive sufficiently in one short minute, so he could weather the burst of punches with which Grecco was sure to greet him in the next round?

While the seconds worked furiously, and Billy Grecco glared across from his battered countenance, impatient of every second given his beaten opponent, Maya Gorman worked his way toward Chastang's corner. Reporters tried to stop him, but he threw aside their hands with a brusque impatience that boded ill for any man who seriously interfered.

The warning ten-second whistle blew just as Gorman reached the corner. A flurry of seconds lifting chairs and climbing through the ropes. Gorman pushed them out of his way.'

"Chastang!" he called in a half-shout which made the dazed fighter turn his head a little.

"Lieutenant Jack Chastang died fighting."

That was all. No comparisons. But a shiver went through the young pugilist. He straightened. Now he got to his feet, and took three strides forward as a cannonball of muscled determination hurtled across the roped arena to meet and destroy him.

They met with exploding impacts of gloves on flesh. The crowd gasped. Chastang, instead of covering up, clinching, and trying to stall, had gone crazy and was wading in, slamming straight rights and lefts to Grecco's middle, forehead, jaw—and miraculously landing some of them as the older fighter was halted, and forced to employ his craft against the unexpected.

Grecco snarled. He suddenly bored in, arms working like trip-hammers, endeavoring to do again what he had done the previous round—only earlier, so there could be no question of the bell interrupting.

Then in a flash it happened. Chastang stepped back, then suddenly forward. His right fist came up almost from the floor. The uppercut smashed into Grecco's damaged face, lifted him three inches from the canvas—and set him down on the small of his back with a crash that shook the Arena!

Reeling, Chastang found the ropes in a neutral corner, and managed to hang on. Grecco slumped over sidewise as the referee began counting—and was still down there when the fatal ten sounded.

"Good boy, Chastang!" yelled Maya Gorman, his voice breaking.

The fair-haired youth turned a one-sided grin in the direction of the voice. "See you—afterward—" he choked. Then as the referee caught hold of his right glove, holding it up momentarily, Chastang slipped to a heap on the canvas, unconscious.

The first man to reach him was Maya Gorman. He had found his new partner and meant to let no one interfere.

"YOU knew my Dad?" That was the first sentence from the swollen lips of young Jack Chastang, No mention of the unexpected victory, which had driven an audience so wild that it had scarcely calmed down enough to take an interest in the slugging finale of heavyweights.

"I did," said Gorman quietly. "He taught me to fly—and we all looked up to him as a man and a gentleman. I want to talk to you after your rub-down, and when you feel up to it. Here's my room number at the St. Charles. Come right along, and have midnight dinner with me

"Wait! I won't be long!" promised Jack. He grabbed Gorman's hand and squeezed it, then turned and flung himself on the table where he would get the ministrations of the negro swipe.

An hour later, compromising on a snack of sandwiches and beer sent to the hotel room, Gorman ate a little and then quietly told the blue-eyed battler all about his father the air fighter, whom Jack had not seen since he was five years of age.

It had turned out that the lad was motherless as well, having been put through high school by an aunt who now herself had suffered reverses and illness. Jack had been sending half his earnings from a dozen preliminary fights—of which he had won ten by kayos—to this aunt. The sums had been pitifully small.

"She'll faint when she gets two-fifty this time!" said Jack, and his bruised features cracked in a smile. "I'd only have got two hundred if I'd lost. You made me win! I—"

"And I hope to make you win a thousand times as much!" broke in Gorman. "I'm going to ask you to hang up your gloves, lad. I need a partner—and I'm prepared to do all the staking on a risky venture. If you say yes, you'll gamble six months to a year of time, perhaps much less. And you'll gamble your life in a wild country..."

A gleam had flashed into the blue eyes, but then Jack shook his head in regretful decision. "I just couldn't," he said sadly. "My aunt, you see. She's in bad health. Hell, you might as well know. The doc told me it was—cancer! No hope. But I've got to see that she wants nothing for the next few months, and—"

"And if you go with me," said Gorman, knots of muscle showing along his lean jaws, "a money order for five thousand will go tomorrow to your aunt! That will take care of her, won't it?"

"Lord yes!" breathed Jack Chastang. "But—but what am I to do for any important money like that? I've never been a crook, and don't aim to start now!"

There was an apologetic grin that went with that, which robbed the words of offense. The blue eyes stayed serious, though.

"The truth is, I hate the ring—not for the scrapping, but because every fight card seems to be crooked," he went on hastily. "My manager hasn't been here to congratulate me. I—I think he bet on Billy Grecco!"

"Well, that wouldn't be exactly crooked."

"No-o, but—well, let's talk about somep'n else. What can I do to be worth five grand? I spent two years peddling vegetables!" he ended with a likeable chuckle. "Anything at all to eat during the depression, you know."

Gorman nodded. Then, wasting no words, he spread the panorama of Yucatan before Jack Chastang, showing how that wild land was being brought into cultivation again after a lapse of centuries, and subdued to the welfare and will of man.

"The only remaining menaces are the Sublevado Indians," he went on. "They never have been tamed—simply because no one has been able to track down the hidden city or cities in which they dwell. Of course most of the ancient ruins, which easily could hide the few thousand Sublevados there probably are, are silted under and then overgrown with jungle. Men found only a few temple tops and pillars projecting at Chichen Itza, for instance, and that once was a metropolis of half a million souls! It would mean everything to Yucatan if a white man could find a way to the Sublevado city—and return alive!"

"You mean then a modern Mexican army would march in and crush them—like Italy's doing in Africa now? I don't know as I care a hell of a lot for that!" objected Jack slowly.

Gorman's features grew harsh. "The other Mayas were conquered," he said stonily. "Now they're prosperous, and ten times as contented as they ever were before. And besides—the Sublevados raided my ranch, burned it, killed twelve of my servants, and murdered my wife and baby!"

"Oh my Lord!" breathed Jack in quick sympathy.

"Oh, I took toll," said Gorman, his face paling beneath the tan. "It's not vengeance I'm after now, it's security for others, both Maya and white. And then there's one more thing. This will appeal to you. The Sublevados are ignorant now. They have in their possession an immense treasure of emeralds, sapphires, jade and gold—and they do not even know of this treasure!

"I intend to go with you and get it. Half will be yours!"

Jack was on his feet impulsively. "You really mean there's a chance for treasure?" he cried.

"I do. Look at this," said Gorman, and brought forth the knotted gold wire. Briefly he told the story of the Quiche knot writing, and how he had discovered this record of an unnamed temple of Kukil Kan and Tonatiuh (the sun god), the twin divinities of the ancient Mayas.

"The knots are a sort of shorthand, not an alphabet. That's why white men have had so much trouble reading them. I have got a good part of it, though there are some blanks. Just for you to read once, Jack Chastang, I've made a rather free translation. Here it is!" And he held forth a sheet of paper which Jack took, reading rapidly aloud:

In the shrine of the Serpent and the Sun God, (symbolised as the Eagle), follow the river of blood from the cuauhxicalli (gourd cup of the eagle) eighteen paces. Lift rocking stone. Descend (probably a stairway) to sacred inhli (now called a cenote: an underground pool of fresh water) where in the black waters are hidden the treasures of our priesthood, to wit:...

Jack looked up rather blankly. "It doesn't say what the treasures are!" he objected.

"The knots tell. I didn't write that down, with the record of what each priest added," said Gorman, "but it's all there in the knots. As near as I can come, translating old measures into those we use, there are about eight quarts of precious stones, chiefly emeralds and sapphires, with some large opals; many pieces of carved jade which may or may not be valuable; and something like half a ton of gold bullion and golden ornaments!"

Jack whistled, but then an objection came instantly to him.

"It doesn't say anything about where this is. Do the knots tell that?"

"Not a word," answered Gorman grimly. "It was a secret handed from one high priest to the next, I think. Then probably one of them died before he could tell, and no one ever thought to examine the hilt of the knife. Naturally there was no need to specify latitude and longitude."

"Then—how?" queried Jack, considerably deflated. "You said this was a secret city, and that nobody had found it."

"I think one rather eccentric white man knows. He and his family are paleontologists rather than archaeologists, and live the lives of hermits. I'll find out—if old Severn really does know. If not—well, we'll keep going till we find it ourselves, or lose interest—"

"Huh! The only way I'd lose interest in a thing like that, would be if I was good and dead!"

"Exactly!" said Maya Gorman grimly.

TEN days later, dressed in the seersucker suits and straws of casual tourists, they disembarked with bulging telescope bags at Progreso. Gorman knew the Mexican customs officials, and immediately pledged them to secrecy. No one was to know of Gorman's return. As soon as they were released, the bronzed man led the way by back streets to a part of the thriving port into which he had not penetrated. Of course there was always some risk of encountering an Indian who would recognize Gorman and spread the news, but that chance had to be taken.

Gorman procured mules, arms, ammunition and a pack of necessary provisions. The one pack mule would be heavily loaded at first, but time would lighten the burden.

Of necessity they stayed one night in the louse-ridden cuartel. Jack Chastang, who had never been away from the southeastern part of the United States, was spellbound at the throngs of native women crowding the narrow streets, scarf-like rebozos thrown about their shoulders, each bearing upon her upturned palm a shallow basket, going barefoot to market; at the strident-voiced water-sellers, delivering rainwater to their customers from hogsheads mounted on two wheels and drawn by mules; at the city bells which rang each evening (and any other time at all), clashing and clanging as though a thousand apes were banging together cymbals and dented dish-pans; at the overdressed, gallant caballeros who admired and ogled the señoritas; and at the scents of flowers banked in cultivated profusion beneath the blossoming trees at each of the thatched cottages of the native Indians.

Jack was breathing deeply. His blue eyes shone with the excitement of a first venture unhampered by money lack or the care of dependents. He knew that his dying aunt would get the best attention possible in such a case, from her old doctor and the black maid who had been with her for thirty years—staying even when not only wages but food itself was lacking.

Maya Gorman naturally looked upon the blue-eyed youngster as a courageous and willing, but still callow reincarnation of

Lieutenant Jack Chastang; but before they had reached the second night's camp in the monte, young Jack began to emerge from his out-of-focus, inherited personality, as a distinct individual in his own right.

He proved a curious mixture of bigot and happy-go-lucky adventurer. He played an enormous Hohner harmonica, which he carried in one hip pocket; and Gorman heard some excellently rendered jazz for the first time from such an instrument. The harmonica would have to be muted soon, but Jack understood that.

He could tell stories, particularly of Alabama negroes, with excellent mimicry and a sharp but tolerant sense of humor. Except for one thing, Jack was wholly likeable—the material from which a good comrade for the long trail is made.

His glaring defect was a fault of his narrow upbringing, and the feeling of superiority almost invariably found in every blood-pure Alabama family able to trace ancestry back to the gory days of Sam Dale, William Weatherford, Andrew Jackson, and the massacres at Forts Mims and Sinquefield. He had a withering contempt for all Mexicans, lumping Indians, Spaniards, cholos and mestizos under the one derogatory term of Spiggoties.

The first time or two such a contemptuous reference came up, Gorman was shocked and disturbed. He knew only too well that Mexico holds all sorts, and Yucatan probably a huge percentage of the actual outlaw population; but he had learned that even the worst of them were not to be underrated either as enemies or friends. Maya Gorman was perhaps the best-loved and best-hated white man who ever had lived in Yucatan.

"Look here. Jack," he said, while they smoked jacoosh about their evening camp-fire of the third evening. "I want to show you something. First, I'll say that some Gormans of my particular tribe were early settlers at Old Hadley. I tell you that just because I know you, a Southerner, are proud of your lineage."

"Why, I wasn't—" began Jack, puzzled.

"No, you weren't snowing on me," nodded Gorman rather grimly, "but in a way you were without realizing it. Mexico is full of real men, and I don't want you to forget it. Look here!"

With that he opened his shirt at the neck, pulled down the cotton undershirt, and showed a curious crimson tattoo On his chest. It was somewhat different from the ordinary snake masks of temple carving, in that this serpent was two-headed. This was about four inches in length, as coiled, a bright red, and stood out in sharp contrast to white skin here little touched by sun.

"This is the emblem of the Sh'Tol Brothers Society, which dates back surely seven hundred years—probably much more. I am an elder, and certain of the Mayas are my friends and brothers."

"Oh, I'm sorry!" said Jack with instant contrition. "I—well, I've got a lot to learn—about infighting, I reckon!" He grinned and proffered his hand rather shamefacedly. Gorman took it, with no more words. From that moment dated their better mutual understanding, based upon themselves, rather than upon a tragedy of seventeen years before.

GORMAN, in mapping their southward course, aimed to reach Suchun, a deserted ruin, partially unearthed, of what once had been a great city. Here they could find water readily available from the ancient wells and cenotcs; and over the parched, calcareous soil of Yucatan, where there are no rushing rivers and few lakes, water remains the great problem of travel or residence.

"We'll make a long circuit around Merida, which is getting to be a cosmopolitan city now," said Gorman, starting next morning after breakfast, which ended with a deep draught of the sweet liquor they carried for drink en route. The two cans of this mixture of slightly fermented corn-honey-water beverage, which the Mexicans call posole, assuaged thirst far better than rain water—or than the extremely hard water to be found in most of the wells.

"A city out here!" exclaimed Jack, and shrugged. He gazed at the stunted mahoganies and umbrella oaks through which the tireless mules were starting.

"Merida was once called T'Ho. It always has been the capital of Yucatan. More than six hundred hot and palpitating Spanish hearts were fed in one week to the Sun God there."

"Ugh!" shivered Jack. "They were cruel. Are the Sublevados that sort now?"

"Yes, and it isn't cruelty, exactly," said Gorman soberly. "It's fanaticism mixed with religion. They have the deep-rooted notion that their gods have to be fed and that human hearts, torn fresh from victims, are the most acceptable victuals.

"That so-called calendar stone, which created such a furore a few years ago, was not a calendar at all. It was the mouth of Tonatiuh, the Sun god, sometimes called the 'cup of god' by the Mayas. That was where the human hearts were placed at each sacrifice. I think you'll see more than one of 'em. But when we locate the one mentioned in those Quiche knots—"

"The end of the rainbow!" chuckled Jack. "Oh well, I kinda hope we don't discover it too darned soon. D'you know, this is the first time I've ever felt real free in my whole life?"

All the while they had been traveling—by easy stages at first, so that Jack could get accustomed to one of the least comfortable inventions of man, a mule saddle—the peninsula was shuddering in the grip of a new terror. At Progreso it had not been much in evidence, though Gorman must have learned the tale in short order had he not chosen to remain incognito, and seem a mere tourist from the North.

The story was to reach them now, and with tragic force. They followed what probably was a deer trail through grass high enough to reach the eyes of the mules, a barren plateau with few trees, when at last they came to a downslope much like the rimrock cliff in western North America. And there below lay ruins, and a haze of 'smoke which looked as though it might have come from a campfire of Indians.

"Watch this. It may not be what it looks like," said Gorman. "Stay behind, and have your gun loose...."

With that he urged his mule to a shamble, and went to investigate. Because of the luxurious brakes, high grass and other scrub vegetation which covers everything, neither white man burdened himself with a rifle. An automatic for fast shooting, and a revolver for greater dependability in a pinch, were Maya Gorman's weapons. He was no trick shot with either, but at the snapshot distances of the monte he never missed a target the size of a man.

Now, with all senses alert, he rode slowly toward the source of smoke. Feet were disentangled from the stirrups, and he was ready to leap to the ground on either side. But the place was still—too still. He saw at once that here had been a village, probably Ulmeca Mayans, since here at the border of a small clearing, planted in maize, was a prayer stone of Hunal Ku—the deity placed above even the eagle and snake gods by this one tribe.

A shuttering of heavy, horrible wings came suddenly, and at least fifty black, fringe-winged turkey buzzards beat their way into the air. A half dozen scattered and mutilated native corpses lying near the ashes of the nás told of the interrupted, grisly feast.

"Gorman!" came the excited call of Jack Chastang, who had fallen forty yards in the rear, and could see nothing save the horrible scavengers beating their heavy bodies into the air.

"It's all right, come on. Nobody here—" answered Gorman, swinging to the ground.

That second he knew better. A bush moved, revealing a squat brown body naked to the waist. A bow twanged! The arrow sped straight and head-high in a flat trajectory, striking the wooden crupper of the mule saddle and glancing upward, narrowly missing Gorman's head!

In a flash he ducked, scrambled forward through the legs of the stolid mule, and came up like an acrobat, both short guns spouting flame!

The Indian in the bush, with a second arrow ready, let it go with a puerile force that sent it looping slowly to Gorman's feet. A red hole had appeared at the very center of his flat nose, and he sank back soundless into the grass.

GORMAN leapt to cover, and to intercept Jack. But then, though they exercised the greatest caution, stalking the whole vicinity of the ruined village, they found no more hostile Indians. Jack, his eyes wide with awe at sight of his first enemy killed in action, was silent—anxious only to anticipate the orders or suggestions of Maya Gorman.

The latter, once they were sure no more arrows would come winging from ambush, knelt down and made a careful examination of the dead brown man. The black eyes grew steadily more serious.

"This is incredible. Jack!" said Gorman at length. He shook his head. "Here we are, a good hundred and fifty miles from—well, from the place which I figured on making our headquarters in the search—and here is a Sublevado Indian, who belongs way down across the line of Quintana Root."

"Means little to me, except it's south somewhere," said Jack. "What happened? Was it a raid?"

Gorman nodded. He moved over to the other bodies, examining the pitiful fragments left by the scavenger birds and jaguars. Nothing much could be told from them, save that the dead were all males, and they had died with knives or other weapons in their hands. In the whole gutted village there was no sign of women or children.

"When the raid started, they took to the bush," said Gorman. "Come on. There's nothing we can do here."

A short distance further, and his guess was confirmed. The bodies of two native women and no less than fourteen brown children lay in a glade, providing the buzzards with another banquet. Jack turned green at the mouth corners and had to keep his eyes away.

Gorman made no comment, but he saw-that the other mothers and young girls had been carried away by the Sublevados, who must have come in considerable force. He failed to understand such daring on the part of the tribe whose movements always had been so completely veiled in secrecy that not even scouting airplanes had been able to discover their headquarters.

They went on; and that evening Gorman made for a bare knoll, from which he took a long survey of the surrounding country before descending to make camp. From now on he and Jack would not sleep near their camp-fires, but wait until dark and then hide their beds in the bush.

NEXT morning they broke camp, Gorman taciturn and Jack whistling thoughtfully to himself. They had ridden no more than half a mile south when an exclamation burst from the younger man's lips, and he pointed. There, dashing through the brush was a brown woman loaded down with two naked babies!

Gorman dismounted running, and left his mule for Jack to tend. Here was a chance to learn something first hand from an Indian, concerning the Sublevados and what had happened at the village!

Of course the tall American gained swiftly in the pursuit. The burdened squaw, seeing that she could not escape, hurriedly thrust her two babies into a bush, then turned and ran a short distance. When Gorman reached her, though, she had seated herself on the ground, face stoical, prepared for death.

"Amigo! Friend!" was his first word, with the accompaniment of uplifted palm. Then he spoke swiftly, first in Spanish, then, seeing she did not comprehend readily, in Mayan. He told her that he did not wish her harm; that her babies were safe, and that all he wanted to know was something about what had happened at her village.

It took time for the simplest thing to get across. Then the woman's face began to work strangely. She shrieked, beat her breast, and suddenly leapt up to waddle as fast as she could go to the spot where she had flung the little ones. Even then she crouched over them, unable to believe even when Gorman offered her food from the mule pack, and spoke soothingly.

In time Gorman did persuade her, but he got little for his pains. The woman knew there had been a sudden attack by the fierce Sublevados—led by someone they called the "dreaded Fire Priest"—but she had fled with the other women, then taken to her heels again when the raiders found the group of women and children. She thought that she alone had escaped, which possibly was the truth.

A half hour later Gorman returned, with a heavy pack on his shoulders, and without his mule. "I can walk just as fast, or straddle the pack mule once in a while," he said gruffly, when Jack asked him wonderingly what had become of the moth-eaten mount.

Jack blinked. A little later, looking down upon the heavily laden back of the tall man who now led the pack mule by hand, the blue-eyed ex-pugilist smiled a little and shook his head. In the sordid, flashy world of the ring in which he had moved for many months, there were few men indeed who would give up their means of locomotion in the wilderness to a fat, greasy Indian squaw with a couple of babies... just so she could reach the Merida mission....

It was an odd fact, but just then Gorman swore angrily aloud. He had just remembered a fifty dollar bet on a fight that he had failed utterly to collect!

FIVE days of slow travel passed. Jack Chastang moved in wonderland, insatiably asking questions. And Gorman, steeped in the lore of the ancients, could tell him tales of the old civilization which had long passed its prime and which decayed and fell to the ground half a century before the coming of the avaricious Spaniards.

The stories ranged all the way from the work of the old Mayan botanists, who developed maize from the seeds of wild grasses, to the architecture of the almost fearsome ruins—such as those the Rockefeller Foundation had uncovered at Loltun—which were the archetypes of the modern set-back skyscraper.

"Anywhere we go throughout the peninsula," said Gorman, "there are splendid roads in an excellent state of preservation.".

"Roads? I haven't seen any!" grinned Jack.

"Only a few of them have been uncovered. There is a layer of about six feet of sand and silt on top of them now, and all the jungle growths, of course. But the roads are there. They linked every square league in Yucatan and Quintana Roo. They are exactly the same binding material, foundation and surface as John L. McAdam invented for the white race something like seven hundred years later!"

"Huh! And they've slipped so far they just use knives and bows and arrows now, and live in those grass houses?" queried Jack. "The Mayas, I mean."

Gorman grimaced slightly, flexing his knee which still held a certain amount or stiffness—and probably always would.

"Some of the Sublevados have guns," he said. "Didn't you notice that two of those dead Ulmecas had been shot in the head?"

"No, I—I didn't look that close."

"They've slipped, all right. No one knows too much about the Sublevados, unless it's Professor Severn whom we're going to visit. He has hinted a couple of times to me that he made friends with that tribe. He's a crazy paleontologist—fossil-hunter—who brought his wife and three girl children out to live alone in the monte. They've taken over a building they dug out themselves, one that used to be a nunnery."

"Girls? Out here?" cried Jack.

"Yep. Oldest about twelve. Teaches them himself. I think it's terrible, but what can you do with a professor? His wife helped him, until she got yellow fever. Lost all her hair, and nearly died. I haven't seen them for about... hm... eight years, but I heard last summer they were still at the old place."

Jack looked dubious—and he would have been even more put out had he guessed the natural human mistake Gorman had made. He had neglected to add the eight years to the age of the children he had met long before; and even girls reared and educated in the monte do have a way of becoming women, given sufficient time....

"I don't hold much with girls. They just seem to make a lot of trouble," he said.

Gorman smiled sadly. At times now he could forget the hideous tragedy of his own life and love; but his whole attitude toward the Sublevado tribe was colored an uncompromising crimson by it. As far as he was concerned, even the Sublevados who had not been in that raid upon the Gorman rancho, were criminal fanatics all ready to repeat just such offenses whenever they got the opportunity.

One tale got a hearty laugh out of Jack. Gorman had been away from the North too long, and had not attended any motion pictures on his one trip. Thus when he started speculating aloud over the Fire Priest, he said the whole tribe of magicians were dangerous nuisances, if not worse. They had charge of the annual invocation to the rain god, as well as other rites, and exercised the power of life and death—usually death, with trimmings.

"They are known as H-men," said Gorman innocently.

"Wha-at? Oh, that's a joke, of course!" But when Jack found himself required to explain G-men to a companion who had never heard of such creatures, the younger man saw the ludicrous comparison, and could not stop chuckling for half an hour.

Every thought of humor left them then. They reached Pootun, which Gorman had visited twice. It consisted of ruins around which a Mexican family named Chablé had established a plantation, raising corn of course, but rotating with other crops, modern fashion.

The hacienda was a gutted ruin, only part of its plaster walls still standing. Of the village of Mayas who had worked the fields, not a ná remained. Complete desolation everywhere. Only a few whitened bones, picked by scavengers, suggested the fate of the haciendados and their forty or more employees.

"This is a sort of crusade," said Gorman grimly. "Just for loot they never would have come so far from home. And judging by the fact they visited this place earlier, they were going north at the time they struck that other village. That means they may be anywhere along our trail right now!

"How about this Severn family?" queried Jack soberly.

Gorman could only shake his head. Friendship with the Sublevados would mean mighty little when some fanatic soaked them in balché liquor, and urged them to kill all white men and Mayas who worked for them.

For three more days they struck southward, seeing no recent sign of the marauders. Two small villages lay in ruins, but after an examination, Gorman said these had been destroyed months earlier.

Conversation had died. In truth Gorman was wondering if he should not abandon the quest and place himself at the service of the Mexican authorities. He could not imagine why rurales had not come out with planes, and intercepted the Sublevados before they had achieved this country-wide waste of life and property.

Jack Chastang was an extremely thoughtful youth. He had said briefly once that it is one thing to look toward a venture, weighing chances and accepting them, and entirely another to wade through death and destruction where other adventurers in the wilderness had failed.

THEY reached the Lake of Bitter Waters. It is an interesting phenomenon, a lake of Epsom and other salts, but with a geyser of fresh water rising in the middle. A man may swim out and fill canteens or other receptacles, and surfer no ill effects from drinking. Save for using it to replenish their drinking supply, however, they paid it little attention. Beyond here, just a dozen miles lay the ruins where Professor Vernon Severn had made his home; and here they would encounter the first real test of luck.

Gorman could not wait. "This will be headquarters. Keep out of sight," he told his companion. "I'll be back in thirty-six hours at the latest. If I'm not—streak it for Merida."

"Meaning if you go alone and get killed, I'm to give up? The hell with you! I'm going along—all the way!" was Jack's firm retort. "So far I've had a nice ride; but if we're going to start something, believe me I intend to be in it!"

After a second of somber reflection Gorman's harsh features cracked in a smile. "I was kinda hoping you'd say that, Jack," he admitted. "I oughtn't ever have brought you here—but now you are in the middle of it—"

"I'm taking my chances, compadre!" grinned Jack. He was immensely more cheerful when they started out on foot at nightfall, carrying only water, charqui and firearms. The other parts of equipment they cached carefully, leaving the mules to forage free. Since these intelligent animals had learned long ago to follow their noses to fresh water, one sight of them swimming out in the lake for a drink relieved any worry regarding their safety.

Bright moonlight and a refreshing breeze made this added travel bearable. Maya Gorman was less sure of directions, however, for night in the monte makes all objects and even directions seem strange.

"I could swear we'd turned around and were going north again," Jack whispered once.

Gorman at once halted, and took a careful sight by the moon—which was difficult now, since it was almost overhead. Then he shook his head. "I think we're still right. In another two miles we'll know, for beside the nunnery at Severn's city there's a pyramid which shows for quite a distance."

Before that sight could meet their eyes, though, Gorman suddenly caught his companion's arm. "Look!" he said in an almost inaudible voice.

They were at the edge of one of the treeless glades which occur constantly through the monte, patches where the calcareous soil thins out and bedrock comes to the surface, refusing the roots of all vegetation. Following Maya Gorman's pointing finger, Jack saw a charred skeleton of something hanging in the burnt treetops straight across the open glade.

"An airplane—crashed!" whispered Jack.

"Yes, the rurales were on the job," said Gorman grimly. "No chance, of course, but let's see. Oh my heavens!"

With a feeling of sickness rising in his throat he saw a dozen or more black things in front of him. They were dead buzzards!

"Stay back! I think I know what this must be!" commanded the elder sternly. And this time Jack was only too glad to obey. Pistol in hand, he waited, listening but not caring to look any closer.

Gorman found what he suspected. A sort of trail led from the other side of the glade; and lying there were three partially dismembered corpses. Through the brush on either side were more—he did not care to find out how many.

With the greatest care he entered the trail, examining every trailer and vine. Then he exclaimed grimly, cutting off a length of dead fiber, to which was attached a small thorn. He took it back to show Jack.

"Those were rurales, to judge by the remnants of their uniforms," he said. "For some reason they were in distress, or the plane was. It tried to land, and found that glade too small.

"When it fell, they all rushed into that trail, probably to try to save their comrade. And that too-plain path was a Sublevado thorn trap. Look at this, but handle it with extreme care. They kill several foxes, hang them up tec decay, and then stud every inch of their bodies with these thorns, like ticks.

"After a few days they remove the thorns, and then fix them with springy saplings and fiber everywhere along a path which their enemies may be induced to follow. Well—one prick, which a man will scarcely notice, will kill him horribly in about twenty minutes!

"Not only that. His whole body will bloat and be poisoned. Therefore the dead buzzards."

"I—don't wonder any more—why you hate them," said Jack slowly. He flung the thorn from him into the brush. "Is there any way forward where—we won't encounter thorns?"

"Yes, only it won't be a path or trail, from now on."

Gorman made Jack follow in single file. With greatest care he pushed a way through the thickets of the monte, wishing now for a machete such as is carried by every chiclero.

IT WAS slow travel, though an occasional glade helped. And Gorman heard a faint, mellow sound which he had to call to Jack's attention. When they had stopped stock-still they both heard it thrice more.

"It's the tunkul. Temple gong. That means we're right near—and that the rurales are not bothering. Probably all dead. I don't like it. Don't like it at all. How can their place be so damn near Severn's?"

"Maybe they've moved in there," Jack suggested.

Another quarter hour, and above the trees of the monte they could see the flat-topped pyramid of which Gorman had spoken. In the moonlight it would have passed unnoted save for the searching scrutiny they maintained.

The intervening half mile they covered as stealthily as Indians, but there was no alarm, and they saw no signs of the Sublevados. Also, when they reached cover some eighty yards from the small white building which Gorman knew to be the excavated nunnery in which Severn and his family lived, there was no light anywhere, no sound. Only moonlight shining brightly on the piles of ancient ruins. Gorman noted that several more queer bits of architecture had been recovered from the monte, which must have been a herculean job for one man.

The nunnery was at the bottom of a shallow gulch, the gulch being the excavation. It was a building about fifty feet long by thirty wide. Eight years before when Gorman had first entered it there had been one door, several air vents in the roof, but no windows. Now one of the heavy blocks of stone had been removed from each of the four walls to make a window; but there were no frames and no glass.

Gorman felt a disheartened certainty that he was not going to find the Severn family alive in their home. Of course they might have finished their work during the year that had elapsed since hearing they were still in the nunnery; but a crankish hermit like Vernon Severn was not apt to consider his job done while there yet was a breath in his lungs.

Taking a chance in the open moonlight, Gorman led the way to the doorless doorway, pistol in hand. But a whispered exclamation left his lips as he hustled Jack inside.

"Listen!" he whispered.

For ten minutes they stood there in the dark, able to hear or see nothing save the pale oblong of doorway through which they had entered. The place smelled of charred wood, however.

Clicking a new battery into his tiny flashlight, Gorman chanced a view of the interior. There once had been rude partitions of saplings and thatch, dividing the interior into four rooms. There had been home-made furniture of a rude sort.

Now there was nothing but ashes and char—and at one side the reconstructed skeleton of some prehistoric beast like a baby dinosaur, raising his long neck and sightless skull to peer at them.

The Sublevados had turned upon their old friend, and destroyed his workshop and home. Severn had worked for many years as a combined archaeologist and paleontologist—the latter science being his chief interest—attempting to establish some queer theory in respect to a similarity in fossil remains and culture between Yucatan and the Azores Islands. He had called the Azores "the last mountain tops of Atlantis." Gorman had just smiled at him; for the Mayans had stirring historical legends of their own, showing a vast immigration southward from what is now Florida. Gorman believed, without going into the matter as a student, that the Mayas (or Chanes) had a common ancestry with the Seminole and other Muskogee Indians of the southern part of North America,

"Can't keep a light going. Nothing we can do till morning," whispered Gorman. "Let's make ourselves comfortable as possible over here in a corner. Now you sleep a while, and I'll waken you for your watch."

With an exhausted sigh Jack sank down on the cold stone floor, pillowing his head on his arms. In three minutes he slept. Gorman sat with his back to the wall, somberly pondering the vengeance he hoped to bring upon this tribe of murderers. Jack and he, Gorman, had no right to pursue their quest of treasure. Let them once determine the hideout of the Sublevados, and it was plain duty to take the information to the Mexican authorities.

"They're right close here somewhere," he reflected. "More than likely in the underground workings of this very city. Maybe Severn uncovered too much. We'll have to be able to say how to get at 'cm, though. Ten thousand rurales could never break down into these piles of masonry, unless they had at least one passage in."

At that moment came the mellow, all-pervasive sound of the tunkul—one stroke this time to herald the first streaking of dawn in the east. Gorman held his breath and his heart thudded. That gong was not very near. The sound came to his ears through the masonry; he was sure of that.

"That settles it; they're underground here! I won't sleep now."

Oddly enough the quivering sound had not awakened Jack. So after a moment Gorman arose, stretched his cramped legs, and tiptoed over to the doorway, but he could not see any sign of dawn as yet, and realized that the Sublevado priest who had given the signal for that stroke of the tunkul must have been stationed on some high place—probably the flat-topped pyramid.

An hour passed. Gray light came, then a tinge of orange red. Gorman had not sat down, but gradually had receded from the open doorway. Now he could see his way about the char-strewn floor of the ancient nunnery, and made a preliminary examination.

Over in one corner where probably there had been a bed, lay the charred, headless body of a woman. No doubt Mrs. Severn.

"So old and withered by illness she didn't appeal to them. She was lucky," said Gorman hoarsely, half-aloud.

"Eh? What's that? Is it time for me—oh hell!" came Jack's hurried whisper as he aroused. "You didn't sleep!"

"An old codger doesn't need much sleep," Gorman whispered back. "Get up, but make no noise." He went on, looking for the bodies of Professor Severn and his three daughters, but they were not in sight. Jack was silent, his young spirits depressed by this smiling land of horror into which he had come so happily. He watched as Maya Gorman reached a square of stone floor which had been back in the primitive kitchen.

Everywhere else but here, the fire which had consumed the interior of the nunnery had left ashes and litter. Here was none of that—but something else even more shivery. Over a space more than a yard square, there appeared to be a covering of smooth, brown-red linoleum. Gorman said as much, and added:

"Only, it isn't linoleum, or thick varnish. It's human blood. Now, why would it be spilled there in the exact form of a square? Quite as though someone had applied it with a brush?"

JACK had nothing to offer, except scraping away some of the hard-dried blood with his knife. There appeared to be nothing more than plain stone blocks underneath.

Gorman shrugged and turned away, peering, cautiously from one of the open windows, then another. He saw nothing, heard nothing. Somewhere underground here must be a considerable number of Sublevado Mayas. He could think of no plan that offered a chance of success—none greater than hiding here, watching, until such time as another raiding party left or returned. Then, a swift trip to tell the authorities. Later, perhaps, the treasure search—

"Chief!" whispered Jack, who had been scraping away with his knife, and now had it vertical with an inch of its blade in a crack. "You were telling me about these underground cisterns, these cenotes—"

Something like a smothered groan burst from Gorman. "Kid, you've hit it! What a dumbbell I was!" he whispered, tiptoeing hastily back. "Mrs. Severn had to get drinking, cooking, and washing water somewhere! I didn't notice, the time I was here—except I remember now they didn't haul it from a distance.

"And there would be no reason to paint this part of the floor with blood, unless this kitchen well or cenote—which once served the nunnery, of course—had some connection with the main workings!"

Commanding Jack again, and asking him to keep cautious watch, Gorman went down on his knees. The younger man looked a trifle disappointed, but Gorman explained that from his work in Sh'Tol he had learned a good deal about Mayan glyphs—the carvings and mosaics—pictures and intricate geometrical figures—by which they recorded history or gave directions for entering chambers, and the like.

"Even the stone door to a temple bath at Atl, for instance," he explained, "one used by even the commonest of some sixty priests, had glyphs to tell how it opened."

As he was whispering, he ran his fingers over the entire surface. Of course the Sublevados would have puttied in any revealing sunken carvings, but now he had the hint he expected to find the secret soon. This, of course, was a well in common use by the ancient nuns—and by Mrs. Severn, too. It could not be really difficult.

Except for the blood, hardened like thick paint, it was not. Gorman dug out one curious hole with his knife, saw what it was—the open mouth of a snake, with bifurcated tongue broken off at the ends, and hollows on each side of the tongue where a man could put thumb and one finger.

Then he was supposed to lift; and Gorman did just that, after he had knifed through the dried film, around the irregular outline of the snake mask.

There was nothing at all mysterious here—though he expected to encounter mystery later. There were three masks, the outer one squared to fit the other blocks of the floor. Instead of being anything from two feet to five feet thick, like the other blocks of the floor probably were, these concentric masks came out finally and showed themselves a mere three inches thick. Even at that, the outer one would have made too great a weight for a woman to lift.

Listening intently, then cautiously flashing the small beam of flashlight, they saw that this was not a well, but an exceedingly steep flight of steps carved out of the bedrock. Each step, intended for feet much smaller than those of Jack or Maya Gorman, was no more than eight inches deep.

In the center, the steps were worn rounded, until they were half that depth. And the flight descended at an angle of sixty degrees into blackness!

Gorman went first, descending sidewise. It was not hard, and would have been simplicity itself for anyone barefoot. He counted the steps... twenty-eight... thirty... thirty-two... and up to thirty-six. Then he halted, listened, heard nothing but a faint murmuring sound which he recognized as water flowing. He flashed the tiny light.

There were about twelve more steps, and then what looked to be a chamber of whitish rock, with a black pool or flume of water at one side. Jack was coming down now, so Gorman hastened. At the bottom he waited, straining his ears. But no sound other than the faint swish of water moving against rock, came to him.

"Now we've got just this to do," whispered Gorman, when Jack was at his side. "We'll try to explore far enough to be sure of a way into the subterranean city. I'm sure now that at least some of the Sublevados are, there—though they may have another city somewhere. Probably have. But we can't fight a whole tribe single-handed. Once we've got the way in, we go hotfoot for the rurales!"

"I suppose," agreed Jack in a disappointed tone. "Oh-h!" he added, clenching Gorman's arm in a fierce grip.

There was no need for words. Above them came the clattering sound of a thin stone settling into place. The square hole of pale light above the stairway suddenly was reduced to a fraction of its size, and in the irregular outline of a snake mask!

Impulsively Gorman started for the stairs, but he was too late. The second stone was fitted, and immediately the third and last. They were in blank darkness! Some of the Sublevados had found the stairway well open, and had closed it—no doubt would seal it again!

The two adventurers were bottled up in the tunnels and mysterious mazes of this underground city of the Mayas!

"COME!" whispered Gorman, flashing his feeble light. There was no need of explanation now. Only one thing mattered—to get a possible hiding place somewhere. There was certain to be a search for the man or men who had cut through the blood seal and used this stairway, probably in defiance of the orders of the priests.

The water ran in a sort of flume which curved sharply. They took a hasty drink, then followed the rather narrow manway at the side. Above them the rock ceiling arched low, making them crouch. They went upstream, and the ascent was slight. They travelled as silently as possible, hugging the incurving wall, and as yet heard no sound of searchers. Then suddenly came a noise of slapping waters that brought them both to a halt, pistols ready.

Nothing happened! Yet when Gorman snapped on the flash which he had instinctively extinguished, the flow of water in the flume had halted. It was just as deep as before, but stationary. Somewhere one of those flood-gates had been closed!

Cold perspiration was on the foreheads of both men as they went on. Gorman, knowing a good deal about the water systems of these ancient cities, wondered if they simply were going to be caught where they were, and drowned by rising water.

He hurried along perhaps twenty paces further, then came to an abrupt halt. The passage apparently ended, with the flume disappearing in solid rock, and a narrow white partition facing them—a partition covered with queer glyphs, and bearing in its center a beautifully carved snake mask with jade eyes which glinted horrible mockery at them!

"It's a door—if I can open it!" said Gorman hoarsely.

He dropped to his knees, to read the glyphs. Unlike any other Oriental or Occidental writing, these do not begin in any stated place, and are not read backward, left to right, or vertically. Often a fish in low relief is the "akchek" or guide, in front of its nose being a geometrical figure as simple as a triangle or spiral, or as complicated as the maze of the Minotaur. The reader uses this as a sort of mental stencil, and follows the highly colored pictures in this fashion.

"The water—is rising!" said Jack in a stifled voice. A moment more and it was not necessary to say anything. It came to wet the soles of their boots.

Gorman wiped the perspiration out of his eyes. He had found the fish, and followed the simple diagram. Some of it eluded him, and he seemed unable to think. Certainly-one of these symbols, that of a lurid red stork, was right. And could this thing probably meant for a jaguar be the other half of the combination?

Desperately he pressed both of them. The stork grated inward a matter of four inches! But nothing happened!

Hastily he went back over the glyphs, those whose meaning he could decipher. The water came up steadily, impassively.

"Oh, the deer!" he ground out.

This tiny glyph had one slightly projecting horn. He pressed it. No go. And then, fumbling away, he happened to pull it in his own direction. Silently the white panel or door started downward into the floor.

"Jump it quick!" bade Gorman huskily. "It will come back!"

Jack obeyed, when the barrier reached a yard from the floor. Then Gorman followed. But the door went no further either up or down. Something seemed to have gone wrong with the counterweights or hydraulic mechanism which controlled it!

On the other side the water had risen almost to the top of the white rock panel. Gorman tugged fiercely, almost unreasoningly, to raise it. Why he should save the rest of these workings from flood was not clear even in his own mind, so terrific had been the strain of the past ten minutes.

Then in desperation he shoved down!

The heavy white panel went a distance of a foot, and water splashed over. But then with a magnificent disdain of the flood rising and clamoring to break through, the panel went swiftly up to its original position, closing the section of tunnel!

It was not completely water-tight, perhaps. Thin trickles came through near the base. But it attested the almost unbelievable skill of the ancients who, working with chisels of nephrite only, could fashion such masonry for the ages.

Gorman turned, and blinked in complete astonishment. There was a vast pool here, a cenote, with carved images seated about the rim. Before each image was what looked to be a small, flickering fire, a teocalli or votive fire, always tended day and night.