RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Rajah of Monkey Island,"

Ward, Lock, Bowden & Co., London, 1892

"The Rajah of Monkey Island," Title Page

THE Rajah of Monkey Island is a young middy, and the account of his slave-dhow captures and the history of his rise to the commanding position of ruler of Monkey Island will be most fascinating to boys, who will be amused at Ugly-Mug, the Negro cook, and his humorous behaviour. The story is a trifle too long, but it is a very readable one for all that, and the Rajah is a very natural and engaging character.

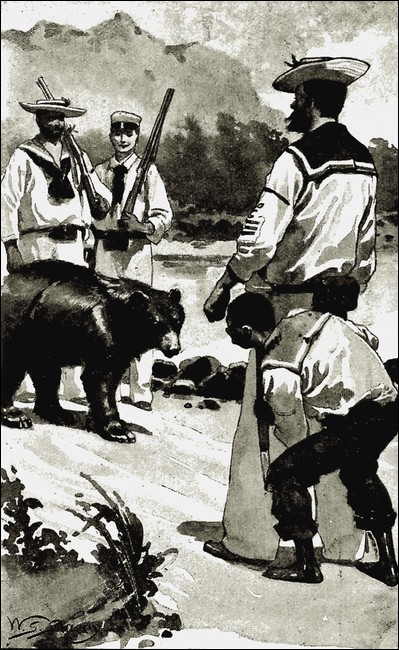

Frontispiece.

Hubert, seizing a tomahawk, cut away vigorously at the rigging.

IN the picturesque old Arab port of Muscat on a certain bright, hot morning in June lay at anchor H.M.S. Spiteful; but it could be seen at a glance that she was about to weigh her anchor and proceed to sea, for the blue peter was flying at the fore, and away to leeward was drifting on the sluggish breeze a filmy dissolving puff of white smoke which a few instants before had shot from the muzzle of one of the sloop's guns; whilst the sullen echoing reverberations of the discharge were still leaping from crag to crag, and from serrated peak to serrated peak of those grey and time-worn heights which frown down so majestically upon the glaring whitewashed town with its towering castle-like forts, and its exceedingly picturesque collection of shipping—the latter consisting largely of the unwieldy-looking, old-fashioned, high-pooped dhows which represent the Arab ships of commerce in these Eastern seas.

On board the Spiteful very busy indications of the excitement reigning throughout the ship were plainly observable. Officers and men were all hard at work getting the messenger rove and the capstan rigged; and from the broken observations which now and again dropped from the lips of the commander and his subordinates it was evident that some more than usually exciting adventure was anticipated which would break through the dull, monotonous routine of life upon the ocean wave.

I may as well let my readers into the secret at once. The commander of the Spiteful had received notice from a reliable source that a number of slavers were on their way northwards from the East Coast of Africa, and as the sloop had only quite lately arrived in the East Indies, and had never yet encountered any of the heartless and wicked traders who drive such a lucrative business by kidnapping and selling their helpless fellow-creatures, they were naturally desirous of doing something to aid in putting down such nefarious proceedings, and doubtless also visions of prize-money floated before their mental vision and made them doubly anxious to strike a deadly blow at this particular squadron of slavers, which, as the report went, were crammed with some hundreds of hapless Africans ruthlessly torn from their native villages in the great Dark Continent.

Volumes of grey smoke are pouring from the Spiteful's funnel, as the seamen and marines stamp sturdily round with the capstan and put their weight upon the bars; whilst the drums and fifes play a stirring march, to which the numerous feet keep rhythmical time as the cable comes in link by link at the hawse- hole. Now the anchor is torn from its resting-place on the ocean bed, and is quickly run up to the bows. The quartermasters are at the wheel, the commander and first-lieutenant are upon the bridge, the engines are turned ahead, the screw commences to revolve and lashes the green water into foam and spray, the Spiteful's nose is turned seawards, the picturesque town and the crevice-seamed heights which surround it begin to gradually recede from view, the leadsmen in the chains are chanting the soundings, the crew are busily at work catting and fishing the anchor, and the commander is alternately anxiously peering seawards through his spy-glass and carefully consulting the chart and the standard-compass.

As soon as the watch is called, the senior midshipman, Hubert Ashley, makes his appearance upon the quarter-deck, for it is his forenoon watch, and it will be his duty to superintend any work that the seamen are carrying out, to heave the log and ascertain the speed of the vessel, and write up the log-book. A bright, intelligent, good-looking boy is Hubert, with auburn hair and tawny eyes, tall and slight, but nevertheless wiry and strong for his age—being at the time of our story a little over sixteen.

Full of the enthusiasm and ardour of youth, and with all the natural and keen love of daring exploits and adventure which seems to be part of the inheritance of most boys of Anglo-Saxon blood, Hubert Ashley—in common with all his mess- mates—was anxiously looking forward to the time when the expected slavers should be reported to be in sight; more especially as he was the middy in charge of the first cutter, and therefore likely to be one of those detailed for duty when the time came.

At six bells (eleven o'clock) Hubert hove the log, and touching his cap to Mr. Archer, the officer of the watch, reported that the sloop's speed was eight knots.

"No more than that?" said the lieutenant interrogatively, as he glanced over the side into the seething, bubbling waters that were rushing past. "We must try and get a little more speed out of her, Mr. Ashley, or we shan't reach Ras Saukirah to- night."

"Is that where the commander expects to come across these slave-dhows, sir?" asked the middy.

"Yes," answered the lieutenant; "the present idea is that we should lie at anchor under shelter of the eastern side of the cape with our upper yards struck and topgallant masts housed, and keep the boats in readiness for intercepting the dhows when they put in an appearance."

"I suppose my cutter will be sure to be sent away on service, sir?" said Hubert, with flashing eyes, but some slight anxiety in his tone, which the lieutenant did not fail to notice.

"The first cutter will certainly form one of the flotilla, and I shall myself, most probably, be in command of the party in your boat. I cannot tell you more than this, Mr. Ashley; and I must warn you not to look upon this forthcoming expedition too much in the light of a spree, for these rascally Arabs often show fight, and are sometimes nasty fellows to deal with."

"But that is the spree, sir," answered the middy laughingly, and with the flash of excitement upon his brow. "It would be no fun at all if the Arabs surrendered without striking a blow!"

"Ah, young blood, young blood!" exclaimed Mr. Archer good- naturedly; "you'll think differently when you come to my age! Now pipe the sweepers, please, Mr. Ashley, and have those ropes at the bitts flemished down properly."

"Ay, ay, sir!" and the middy was soon once more busily immersed in his duties on the quarter-deck.

The engineers soon drove the sloop ahead at a much higher rate of speed, and keeping the bare arid Arabian coast in sight on the starboard hand, the Spiteful—with her top-gallant masts housed—slipped along through the blue waters at twelve knots an hour, and just as the westering sun began to near the horizon and flood the skies with gorgeous roseate tints melting away above into that "peculiar tint of yellow green" beloved of Coleridge, Ras Saukirah was sighted standing out in boldly cut purple outline against the flaming firmament, which latter mirrored itself beneath upon the slumbering, scarcely heaving ocean in a vast expanse of fiery but softer and more subdued colouring.

Not a dhow was visible upon the expanse of sea. The coast was forbidding-looking, uninhabitable, dark, and desolate. The ocean appeared at the moment to be a watery desert.

The sloop found safe anchorage, and all night the boats were kept in readiness for action, and a keen look-out was kept for passing vessels, for there was a glorious full moon—such a moon as is only seen in the tropics, making the night as light as day.

Nothing, however, rewarded the eager watchers on board the man-of-war, and they came to the conclusion, and truly, that the expected slave-dhows had been delayed by the calm, which had set in since the hour of sunset.

When the first pale streaks of dawn appeared in primrose tints a few degrees above the eastern horizon, and the short tropical twilight of early morning began to dim the brightness of the now sinking moon, Hubert Ashley—who was out of his hammock at a very early hour—could restrain his impatience no longer, and slinging his telescope behind his back, mounted the rigging as far as the crosstrees, in order that he might sweep the horizon to more advantage. For some time nothing rewarded the scrutiny, but at length some tiny white patches appeared in the field of the glass, which the middy felt convinced must be the sails of dhows making their way up the coast. They had a spectral appearance through the soft haze that pervaded the distance at that hour of the morning, and had only just come into sight around the rugged, precipitous, cliff-like escarpment of Ras Saukirah. Descending rapidly to the deck, the middy reported what he had seen to the commander—who had just come on deck—and the order was instantly given to man and arm boats. Like lightning the news spread throughout the ship that a squadron of dhows was approaching, running before the S.W. monsoon; and intense excitement prevailed both amongst the officers and the ship's company.

Hubert Ashley hastily armed himself with cutlass and revolver, and then proceeded to muster his cutter's crew and get the boat ready for service. Mr. Archer commanded in the first cutter, and the first lieutenant, who was in charge of the whole flotilla, took up his position in the steam pinnace, which was to tow two cutters and a gig out to sea, in order to intercept the rapidly approaching dhows.

In a very short space of time everything was in readiness, the hawsers were attached, and amid the cheers of their shipmates left on board the Spiteful, the little flotilla of boats glided away in the wake of the steam pinnace, which lashed the sea into foam with her twin screws as she made headway through the blue sparkling waters, making for the offing at a rapid pace.

"Do you think the fellows will fight, sir?" queried the impatient Hubert, as he buckled his cutlass belt more tightly around his waist.

"Impossible to say, my boy," answered Mr. Archer; "we don't even know yet that these dhows are the slavers we are in search of. They may possibly turn out to be peaceable traders after all, and in that case of course we cannot touch them."

The middy's face fell. "That would be a frightful sell, sir; but I don't think it's likely the slavers passed us in the night, do you?"

"No, I don't; because they nearly always keep in as close to the coast as possible, and invariably make this cape, Ras Saukirah. Their knowledge of the art of navigation is naturally very limited."

"Then I'm convinced these are the slavers, sir; you see if I'm not right!"

"The commander thinks they are, if that's any consolation to you, Master Spitfire!"

"Oh, I knew that, sir; I heard him tell the paymaster that the rupees would soon come tumbling in from the Admiralty, for that a large slave squadron was in sight."

"You youngsters won't get many rupees," observed the lieutenant laughingly; "I can promise you that."

"That's because the old admiral gets such a lot of the prize- money, I suppose," said the middy; "I think it's a horrid shame, when he does nothing to earn it."

"Wait till you become an admiral yourself, youngster; you'll talk differently then!"

The boats had now gained an offing, and the squadron of dhows was plainly visible. There were apparently four vessels, and their tall picturesque lateen sails were impelling them forward at a tremendous pace right into the jaws of the unseen British lion.

Suddenly, however, as Hubert was anxiously watching the approaching dhows, he noticed that they had with great promptitude altered course, and with sheets flattened aft, were steering in towards the Arabian shore to the westward of Ras Saukirah.

"They've seen us," said Mr. Archer decisively, "and are going to try and run themselves on shore. They must be slavers, or they would not be so anxious to avoid us."

"Hurrah!" shouted Hubert in his excitement; "I only hope we shall catch them up in time."

The Arab dhows, though unwieldy-looking vessels, are by no means slow sailers, especially when the breeze is light, for their towering lateen sails catch any flaws and puffs of wind that are wandering about on the bosom of the ocean. On this particular occasion, however, the slavers had to contend with a fast little steamer, which, though somewhat handicapped by the boats she was towing, was nevertheless soon observed to be perceptibly gaining upon the chase.

A most exciting race ensued, and as soon as practicable the little bow gun carried by the pinnace opened a galling fire upon the four dhows, in the hopes of disabling them before they could reach the shore. In this she was partially successful, for the heavy yard of one of them was shot away in the slings, and came down with a run, throwing the Arab crew on board into great confusion and no little trepidation.

"Cast off the hawsers, lads!" yelled the first lieutenant in stentorian tones. "First cutters board the disabled dhow, whilst we go in chase of the others."

"Ay, ay, sir!" sung out Mr. Archer in response. "Out with your oars, my men, and give way like fury!"

With an enthusiastic cheer Hubert's boat's crew responded to this appeal, and with a resolute, determined look upon their bronzed countenances, which boded ill for the Arabs when the time for boarding came, gave way vigorously with their twelve oars, and sent the cutter flying through the water at a prodigious pace in the direction of the disabled dhow, which was now rolling helplessly and hopelessly in the ground-swell. A perfect babel of shouts and cries arose from the numerous Arabs on board, which, mingling with the wails and shrieks of the imprisoned slaves pent up below, rose up to heaven in a hideous and almost deafening clamour.

"See that your weapons are ready to hand, lads," said the midshipman in low but determined tones, as he drew a pistol from his belt and cocked it; "these beggars are sure to show fight."

"We'll have to give 'em a lesson if they do, sir," observed the coxswain—a great, broad-shouldered, muscular fellow—loosening his cutlass in its sheath as he spoke. "First cutters to the fore, say I!"

"Ay, ay, that's the ticket," murmured some of the seamen with grim smiles; "up with her, lads!"

The cutter was now close to the dhow, but the Arab crew had evidently recovered from their panic, and were determined to oppose the seamen in their attempt to board, for the barrels of several antiquated-looking muskets were now seen to be protruding over the taffrail, and the next moment fiery jets of flame issued from their muzzles, followed by the ping-ping of bullets, which sang over the heads of those in the cutter, and pattered into the water just astern.

"The rascals!" ejaculated Mr. Archer, as he discharged a revolver at the audacious Arabs; "we're evidently going to have a warm reception."

Hubert was in the greatest delight at the turn affairs were taking, and intense excitement filled his youthful breast when he found himself, for the first time in his life, under fire. The whizz of the bullets caused him not the slightest tremor of fear. His eye and hand were as steady as those of Mr. Archer himself, who had frequently been under fire.

Just as the cutter was crashing alongside the dhow, a second volley was fired by the Arabs, and this time with more effect, for one of the bowmen received a bullet in the shoulder; and, to Hubert's inexpressible dismay and sorrow, Mr. Archer, with a death-like pallor upon his face, fell backwards into the stern- sheets with a groan, his sword falling from his helpless grasp.

"They've shot me!" he gasped faintly; "take command of the boat's crew, Mr. Ashley, and do the best you can."

THERE was no time for Hubert to exchange a word with his superior, for the cutter had now dashed alongside the slaver amid a shower of javelins, and it was imperatively necessary to board her at once. Pressing the wounded lieutenant's hand, therefore, the young middy called to his crew—with the exception of the boat-keepers—to follow him in a desperate attempt to scale the lofty side of the dhow, which was still rolling heavily in the ground-swell. Twice were the brave seamen repulsed by the enraged Arabs, who were furious at the idea of losing their ill-gotten cargo of African slaves, and their vessel; but the Englishmen's blood was now up, and after a furious hand-to-hand scrimmage, they at length forced their way over the bulwarks, and with our brave young hero leading them, leaped down upon the swarthy band of desperadoes that were opposing them, and fairly drove them from under the shelter of their protecting bulwarks.

But though dismayed at the turn affairs were taking, the slaver's crew still continued to fight desperately, and as they were active, muscular fellows, considerably outnumbered the bluejackets, and were fairly well armed, the Spiteful's men found their foes worthy of their steel.

During the mêlée Hubert caught sight of his coxswain desperately defending himself against three fierce-looking Arabs, who had singled him out for attack on account of his having killed one of their chiefs. The seaman, though a very powerful man, and an adept with his weapon, found it extremely difficult to cope with three such formidable adversaries, especially as all the barrels of his revolver had been discharged. Hubert was by nature a very unselfish, chivalric boy, always ready to aid those who had fallen into distress or trouble, and he at once dashed forward to the assistance of his trusty coxswain, who was already wounded in one leg by a sword-cut.

Levelling his revolver with steady aim, our hero shot the most formidable-looking of the Arab trio through the head, and then resolutely attacked one of the remaining ruffians with his cutlass; but here he met with more than his match, for the Arab was possessed of more physical strength than the young midshipman, and also was no mean swordsman; and before many passes had been exchanged, Hubert felt himself grazed by his swarthy opponent's weapon, which had passed clean through his clothes close to the region of the heart. By this time, however, some of the cutter's crew had observed what was going forward, and as most of the slaver's crew had now surrendered, they charged vigorously up and assisted Hubert and his coxswain to seize and disarm their fierce opponents.

A moment afterwards the coxswain came up and shook our hero vigorously by the hand.

"You saved my life, Mr. Ashley, and I'm jiggered if I know how to thank you enough. Those copper-coloured swabs were too much for me, I reckon!"

"Don't say anything about it, Dixon," returned the middy; "I know you'd do the same for me any day."

"Ay, that I would; and my missus and the bairns at home shall bless you some day for the good turn you've done me in this here scrimmage. You'll be an admiral one o' these fine days, Mr. Ashley, and much I should like to be the boatswain of your flagship."

"Now that the dhow is in our possession, we must see to poor Mr. Archer," said Hubert hurriedly; "I am afraid he was seriously wounded."

The lieutenant was found to be somewhat better, though very weak, and he desired the middy to ascertain how many slaves there were on board, and to find out what had become of the steam pinnace and the remaining boats.

The middy took the telescope from his superior's hand, and levelling it over the bulwarks in the direction which the remainder of the flotilla had taken, gazed long and fixedly across the water.

"Well," said Mr. Archer impatiently, "what do you see?"

"One of the dhows has run ashore in the surf, sir," answered Hubert excitedly; "she's broadside on now, and the seas are breaking over her. The slaves seem to be scrambling over the side and struggling through the surf in the direction of the beach. There seem to be a tremendous lot of them."

"I wish the pinnace had caught her up in time," said Mr. Archer, "for she would evidently have been a grand prize. How about the other two dhows, Mr. Ashley?"

"The flotilla has captured the others, sir, and the pinnace is towing them back."

"We shan't have done so badly then, after all. Man the cutter, Mr. Ashley, and get our prize in tow; for the sooner we get back to the Spiteful the better."

In a few minutes a hawser had been made fast, and the unwieldy dhow was being slowly towed in the direction of the Spiteful, which vessel had begun to steam slowly down from her anchorage in order to support the flotilla of boats if necessary. This was a fortunate circumstance, as the sun had now become very hot, and the bluejackets in the boats were somewhat fatigued with all their previous exertions, and found rowing in the heat, with a heavy vessel in tow, a very trying operation.

In half an hour's time all the sloop's boats were back again on board, and a council of the superior officers was held in order to decide what should be done with the Arab crews of the three captured slavers, and how the vessels themselves were to be disposed of. It seemed that the remaining boats of the flotilla had encountered very little opposition when boarding the other two slavers, and only three men had received slight wounds from spears whilst disarming some of the more turbulent of the Arabs. Altogether a hundred and thirty-two slaves had been captured, worth in prize-money £660; and in addition to this a sum of £750 would be due to the captors on account of the tonnage of the dhows, which measured collectively a hundred and fifty tons—so the boat's crews had done a pretty good morning's work.

The commander of the Spiteful, Captain Chetwynd, and the first lieutenant, Mr. Knowles, eventually came to the conclusion that it would be advisable to land the crews of the Arab slavers upon the mainland and let them shift for themselves, for they might give trouble if imprisoned on board the sloop, and the Admiralty did not sanction any mode of meting out punishment to these cruel kidnappers, so as to restrain them from carrying on their nefarious traffic.

As soon, therefore, as the ship's company had finished their dinner, the prisoners were transferred to the pinnace, which boat landed them in a little sheltered bay some distance to the eastward of the spot where the fourth dhow had gone ashore. This latter vessel was now observed through the telescope to have been completely broken up by the violence of the surf, and the tawny sands were strewn with scattered fragments of her hull and spars. Her crew and slaves had all fled into the interior.

With the three captured dhows in tow, H.M.S. Spiteful slowly steamed away in the direction of Aden.

ON arriving at Aden, the captured slaves were landed and handed over to the proper authorities, whose duty it was to see that they were returned to their homes in Africa or found suitable employment—according as they themselves wished. The dhows were broken up and sold for firewood, for fear that they should again fall into the hands of the predatory Arabs engaged in the slave-dealing trade. The Spiteful then once more tripped her anchor, and with a fair south-westerly breeze stood away for her cruising ground off the coast of Arabia, hoping to fall in with more slavers before the season for running the human cargoes should come to an end—which would be as soon as the south-west monsoon had finished blowing up the East African coast.

One night, when Hubert was keeping the middle watch, Mr. Knowles, the first lieutenant, who was doing duty for Mr. Archer whilst that wounded officer was in the sick list, called him up upon the bridge.

"Well, Mr. Ashley, our luck seems to have deserted us, doesn't it?"

"It does indeed, sir. Out of the seven dhows we boarded to- day, not one was a slaver. Don't you think the slaves might be stowed away somewhere below out of sight?"

"Their papers were regular. That is what we have to go by," said the lieutenant. "There is no end to the dodges of these rascally slave-hunting Arabs, and I have no doubt they hoodwink us now and again. It's a thousand pities we can't mete them out severe punishment when they are caught, for that would soon put a stop to it."

"To-morrow is our lucky day, sir,—Sunday; so perhaps we shall fall in with another fleet of slavers."

"Perhaps so!" said Mr. Knowles with a laugh; "but I'm thinking of asking the commander to let me go away for a separate cruise in the steam pinnace, when I should certainly very quickly make some captures. Should you like to come with me, Mr. Ashley? As you are the senior midshipman, I give you the first offer."

"There is nothing I should like better, sir," exclaimed Hubert, with flashing eyes; "it would be a real adventure, wouldn't it?"

"I expect there would be a good bit of reality in it," assented the lieutenant, with a smile; "no doubt we should get some hard knocks, and possibly give some in return; then we should exist principally on salt junk, biscuit, and cocoa; we should get our lovely pink-and-white complexions browned to the colour of an unripe blackberry; and perhaps run short of water, and have to fight our way to the springs ashore."

"I think it would be simply splendid fun," said the middy eagerly; "I don't mind what happens, so long as I can go. You will ask the commander for my services, sir, won't you?"

"I think it is very possible that I shall, Mr. Ashley, for I was extremely pleased with the way you behaved the other day in that affair with the slavers. Now you had better visit the look- outs forward, and see if the bow lights are burning."

A day or two after this conversation had taken place, just after the ship's company had been piped to supper, the marine sentry who was on duty outside the door of the commander's cabin came up to Hubert Ashley as the latter was about to descend the companion ladder, and saluted him.

"The commander wishes to see you in the cabin, sir," he said.

Our hero lost no time in obeying this summons, for he had a shrewd suspicion that it related to the first lieutenant's projected steam-pinnace expedition. Every night since that conversation upon the bridge, Hubert had been visited with vivid dreams in which slavers, buccaneers, and other freebooters of the seas played a prominent part, though they were all eventually vanquished and taken prisoner by a sixteen-year-old midshipman, with whose form and features our hero seemed to be strangely familiar.

On entering the cabin, cap in hand, Hubert found Captain Chetwynd engaged in earnest conversation with Mr. Knowles and the surgeon.

"Well, Mr. Ashley," he observed, turning to our young hero, "are you in favour of a boat expedition, or otherwise?"

"Rather a waste of time asking him that!" said the first lieutenant, with a loud laugh.

"I think Mr. Ashley looks too delicate to be detailed for such a service," put in the surgeon, slily glancing at the middy's lithe, active-looking figure and sun-embrowned countenance.

"Now, none of your larks, Joyce," said the commander; "you're always trying to poke fun at somebody."

"I think I can answer for Mr. Ashley," put in the first lieutenant, looking at our hero, "for I have already ascertained his views on this subject."

"I shall have to try you by court-martial then, Knowles, for tampering with my subordinate officers. Steward! bring some sherry and iced soda water."

"Now, Mr. Ashley, what's your answer?" queried the commander, as soon as the refreshment had been handed round.

"I'm quite in favour of the boat expedition, sir, if I am to take part in it," answered the midshipman, blushing at his own audacity.

The commander, however, only laughed heartily at the remark.

"You mustn't let him get into mischief, Knowles," he said, turning again to the first lieutenant; "he's sure to run his head into danger if you give him the opportunity."

"I'll do my best to restrain him within due bounds, sir," answered Mr. Knowles, with a smile; "but I'd sooner have a dozen chimpanzees and gorillas in my charge than one midshipman, and that's the fact."

"You see the estimation your genus is held in by one of Her Majesty's first lieutenants, Ashley," said Dr. Joyce with a wink; "I think you might find an opportunity to pay him out whilst you are away on this slave-hunting expedition."

"It is settled, then, that the steam pinnace shall leave on her separate cruise to-morrow," said Captain Chetwynd in business-like tones. "You'll see that all the stores and ammunition are got in readiness, Knowles, and I will give you your final instructions in the morning."

The first lieutenant bowed and withdrew.

"And you, Mr. Ashley, will go as midshipman of the boat," continued the commander, turning to our hero; "and I feel sure that you will do everything that lies in your power to assist Mr. Knowles in his arduous duties—for arduous they certainly will be. Send the gunner to me when you go on deck, please."

Hubert remained in a feverish state of excitement until the time came for the pinnace to take her departure, but he was kept busily engaged in helping to prepare the boat for the forthcoming expedition—duties which would have been gladly undertaken by his middy mess-mates could they have thereby earned a right to form part of the crew.

"You're the luckiest fellow under the sun, Hubert," said his especial middy friend, Phil Paddon; "you always manage to get in for all the fighting sprees somehow. Now, look at me, I haven't been in one single scrimmage since the commission began. It's too bad, upon my word it is!"

"Perhaps your turn will come next, old chap," answered Hubert, putting his arm through his chum's; "I'm awfully sorry you're not coming in the pinnace too, for we should have a rare spree together."

"Couldn't you ask the skipper to let me go, too?" asked Paddon, his eyes lighting up with sudden excitement; "I really believe he'd do it for you, Hubert, for you're tremendously in his good books."

"That would be fearful cheek, Phil, when you come to think of it! It would be contrary to all the Queen's Regulations and Admiralty Instructions, as the paymaster would say! I tell you what I will do, though, I'll ask the first luff to put in a good word for you with the skipper; and he may be able to work the oracle."

"You're a brick, Hubert! Strike while the iron's hot, old fellow; there's the first lieutenant talking to the boatswain in the waist. You'll find me below in the gun-room after your confab with him;" and so saying Phil Paddon dived below by the adjacent companion ladder.

As soon as Mr. Knowles had done talking to the boatswain, our hero went up boldly and proffered his request.

"Quite out of the question, Mr. Ashley," said the first lieutenant; "the commander particularly desired me only to take one midshipman, so it would be useless to ask him. I think your friend Paddon a smart young fellow, nevertheless; and when a chance of active service occurs again, he shall not be forgotten. He may rely upon that."

"Good-bye, old fellow," said Paddon, with a mournful look upon his face, as he shook hands with our hero. "I feel somehow as if something was going to happen to you on this cruise, and that I ought to be in the pinnace too, to lend you a hand if anything unusual should turn up."

"Don't croak, there's a good chap!" exclaimed our hero, laughing in spite of himself at his chum's lugubrious countenance. "You may depend upon it I shall take care of myself, and at the worst I can only get a scratch from an Arab's spear or a touch of African fever."

But Paddon shook his head with a melancholy air.

"I only remembered just now a very rum dream I had last night, Hubert," he said, laying his hand on his chum's arm, and earnestly gazing into his frank tawny eyes. "I wish you could back out of this expedition, and ask the first lieutenant to get some one else in your place."

But Hubert's eyes flashed indignantly.

"Fancy giving it up on account of a stupid dream!" he exclaimed with considerable heat. "I'm not such a muff as all that, Phil; and I didn't know that you were superstitious. You're as bad as Dr. Joyce, who believes in the banshee!"

Phil Paddon did not seem to hear his friend's banter. He was looking meditatively on the deck, with a preoccupied expression upon his usually joyous countenance.

"I wish I had remembered the dream sooner," he muttered at length; "I'd have put a spoke in his wheel somehow. I saw the cruel, hungry-looking cannibals quite distinctly, and their horrid knives and flesh-pots; and Hubert, with his arms and legs bound, lying on the ground close to a roaring fire, which sent great sparks flying—"

He was interrupted in his soliloquy by a loud laugh from Hubert.

"I believe you're dreaming now, Phil, and want to take me into the land of Nod with you! Shall I give you a good shaking and wake you up?"

"You're going to take a picked crew with you, aren't you?" asked Paddon, ignoring his chum's remarks.

"Yes, we are."

"Is Dixon, your coxswain, to be one of them?"

"I'm glad to say he is, for his wound turned out to be a very slight affair after all."

"I'm awfully delighted he's going," responded Paddon thoughtfully; "he's as good as three other men as far as strength goes, and has got a head on his shoulders as well."

"You think he'll do for a good dry-nurse for me, I suppose!" said Hubert, with a fresh laugh. "But I must be off now, as it's nearly time for us to be shoving off."

"Good-bye, old chum!" exclaimed Paddon, wringing his friend's hand fervently; "take care of yourself, and don't forget me if the Fates should separate us."

"I'm not likely to forget such a jolly good friend as you are, Phil; and you may safely bet a month's pay that we shall meet again in a fortnight's time."

"I trust so," responded his friend, making an effort to look more cheerful; "and I hope you'll have good luck with the slavers, and earn a lot of prize-money for us."

"The first lieutenant wants you on the quarter-deck, sir," put in a quarter-master, coming up and touching his cap to our hero.

"Muster the boat's crew, if you please, Mr. Ashley," said the first lieutenant. "It's time we were off."

As Hubert was engaged in this duty, he caught a hasty glance of his chum, Phil Paddon, engaged in earnest conversation with Charlie Dixon, the coxswain, who was a general favourite with all the middies.

Ten minutes later, amid the cheers of their shipmates on board the Spiteful, the steam pinnace slowly gathered way, and steamed off in the direction of Socotra, in the neighbourhood of which island the sloop had been cruising for the last day or two.

HUBERT felt a strange sinking of the heart as the steam pinnace began to forge ahead at full speed, and leave the dashing little sloop rolling gently on the long undulating land-swell far behind. The Spiteful had been his ocean home for so long now that he had become quite attached to her, and he genuinely felt the parting with his chum, Paddon, even for a fortnight, although the excitement of preparing for the separate cruise in the pinnace had hitherto prevented his feelings from rising much to the surface.

As the middy gazed at the gradually fading vessel, lost in a somewhat sad reverie, he was roused by the first lieutenant's cheerful voice.

"The old hooker looks well under canvas, doesn't she, Mr. Ashley?"

"Yes, sir. I never saw her look better, and her sails stand out splendidly against the blue sky."

"There goes a parting gun!" exclaimed Mr. Knowles, shading his eyes with his hand as he gazed over the shimmering glare of sunlit water; "that's good-bye, good-luck, and a speedy reunion all in one."

As he spoke, a little puff of white smoke gushed from the muzzle of one of the sloop's forecastle guns, and slowly floated away to leeward as it mingled with the breath of the sea breeze. Then faint and subdued the sullen report came booming through the over-heated, palpitating atmosphere, and died echo-less away in the distance.

"Phil Paddon fired that gun, I know," exclaimed Hubert eagerly; "I heard him ask the gunner to let him do it."

"It's an especial farewell to you then," answered the lieutenant, with a smile; "would you like to fire a charge from our bow gun in response?"

"Oh, may I, sir? How awfully good of you!"

"Shove a cartridge into the twelve-pounder, and screw up the breech, Dixon," ordered the lieutenant.

Hubert sprang forward over the thwarts in the greatest delight, and as soon as the little ordnance had been loaded with a blank charge, he grasped the trigger line and fired it off.

"They'll hear that plain enough, sir," remarked Dixon; "these here Armstrong pets makes no end of a shindy when they're discharged—beats a sixty-four pounder in my opinion."

"Yes, they've heard it, no doubt," assented Hubert meditatively. "I expect Phil is up in the fore-rigging looking at us through a telescope."

"Take you a squint back in return, sir," said Dixon with a grin, as he handed up a large spy-glass; "you'll make him out through that little chap, or Pm a nigger born and bred."

Hubert laughed, and took a long look through the telescope, which was a remarkably powerful one.

"Yes, there's Phil as plain as possible!" he exclaimed; "he's half-way up the fore-rigging. I hope he isn't dreaming still, or he'll probably tumble overboard!"

"Mr. Paddon ain't much of a dreamer, is he?" asked Dixon, looking rather quizzically out of the corners of his eyes at our hero.

"Not generally," said the middy; "but he seems to have had some queer dreams last night. Didn't he tell you anything about it this morning, Dixon, when you were holding that mysterious conversation? I suppose you thought I didn't see you!"

The coxswain looked somewhat confused.

"Mr. Paddon was just saying good-bye to me, and wishing us a jolly cruise," he said, rather hesitatingly. "Bless your heart, Mr. Ashley, it wouldn't be of much account to stuff dreams down my throat, for I don't hold with them much; though I'm a bit superstitious now and again, like most sailors."

"The Spiteful is swinging her main-yard," shouted the first lieutenant from the stern-sheets at this juncture; "she'll soon be out of sight now."

Bringing the sloop once more into the field of the glass, Hubert saw that she was no longer hove-to, but had filled on the port tack and was standing away to the westward with a slow and majestic motion. Before long she was hull-down, then slowly her long tapering spars and filmy, indistinctly outlined canvas appeared to be absorbed in the violet blue of the Indian Ocean at the horizon's verge, and the pinnace seemed to be the only moving thing left within the great circle of sea, with the exception of some swooping snow-white gulls that followed in the foaming wake which the fast-revolving twin screws of the little steamer resolutely churned up.

As the Spiteful faded away from sight, the first lieutenant seized his spy-glass, and anxiously swept the horizon to the southward and eastward.

"Nothing in sight at present," he remarked; "but that is a state of affairs that won't last very long, I expect."

"Has the commander any news about slavers, sir?" asked Hubert.

"Nothing definite; but the interpreter found out from that batch we released the other day that more vessels were loading up with slaves on the coast of Africa, somewhere to the southward of Ras Hafoon."

"Then wouldn't it be a good plan to swoop down on them, sir, before they can make an offing from their port of departure?"

"A very good plan indeed, and we shall eventually make that part of the station our cruising ground, for we are to meet the Spiteful again in a fortnight's time at Brava; but before we turn our nose to the southward, I intend to try and make some captures off the island of Socotra."

"How far distant are we from the island, sir?"

"About thirty miles, I should say."

"Then we shall sight it this afternoon, sir?"

"Yes, undoubtedly, for the mountains there are very lofty. How is her head, helmsman?"

"W. by S. ½ S., sir," answered the man, who was perched up abaft all holding the tiller.

"Keep her on that course," said the lieutenant; "and let one man be stationed forward with a glass to keep a look-out for passing vessels."

"And now I should like to see what sort of a crew we've got, Mr. Ashley," he continued, turning to our hero; "I left it to you and the coxswain to pick them out, you know."

"Well, sir, first and foremost there's Charlie Dixon, the coxswain of my cutter. He's the strongest man in the ship, and a capital fellow all round; can cook, and carpenter, and sing a jolly good song."

"Oh! a first-rate fellow is Dixon," assented the lieutenant. "It isn't the first time we've been shipmates, and I hope it won't be the last. You couldn't have chosen a better man."

"Then there is my servant, Jack Hudson, the marine, sir; he's 6 feet 4 inches, and a deadly shot with a rifle."

"Humph!" observed Mr. Knowles as he looked with a doubtful smile at the Herculean marine, who was chatting with Dixon forward; "I should say an Arab couldn't fail to hit him with the most ancient blunderbuss that ever was made. However, he may do for spare ballast! Well, who's the next on the muster-roll?"

"Fred Morgan, sir; one of the smartest young seamen in the ship. He's captain of my gun, and a splendid hand with the singlesticks. He's talking now to the leading stoker."

"I like his look most decidedly. He's not only a very handsome fellow, but there's character in his face as well, which is a very unusual combination."

"He is a gentleman by birth, sir, I believe," said Hubert, sinking his voice. "Dixon told me about it, but I have never asked Morgan himself as to whether the story was true or not."

"What did Dixon say about it?"

"He only told me that it was all the talk on the lower deck about Morgan being a gentleman. The ship's company say that he was very badly treated by his parents; ran away to sea, and went to the West Indies in a sailing barque; but found the life so hard and rough that he took the first opportunity of engaging himself as ordinary seaman on board a man-of-war."

"It is quite possible the story is a true one," observed the lieutenant, eying Morgan attentively, "and I dare say it is a very sad one, for truth is often stranger than fiction."

"The remaining bluejacket on the list, sir, is Parker, the second captain of the foretop. You know how steady and reliable he is. Then there are the two stokers, the coxswain, and Ugly- Mug, the Krooman, who is to act as ship's cook and interpreter."

"Let him cook for the men by all means," said the lieutenant, with a slight shudder, "but let us enlist Dixon on our own behalf. I believe he can make an excellent sea-pie."

"You don't know how well Ugly-Mug can fry fish, sir," said Hubert with some surprise. "The last time we went for a night's seining, he turned us out such a jolly dish of fried mullet; and he can spin yarns like anything, only it's rather difficult to understand what he says."

"This muster-roll rather reminds me of the 'Hunting of the Snark,'" observed the lieutenant laughingly. "You remember how it recounts in that funniest of books:—

'The crew was complete; it included a boots,

A maker of bonnets and hoods;

A barrister brought to arrange their disputes,

And a broker to value their goods.

A billiard marker, whose skill was immense,

Might perhaps have won more than his share;

But a banker, engaged at enormous expense,

Had the whole of their cash in his care.'"

"Really, sir, you're most awfully uncomplimentary," exclaimed our hero, with a laugh. "I wonder if you class me as the boots or the billiard marker!"

"You can be the banker when we have made some prize-money, if you like," said the lieutenant; "and judging from the elaborate way your boots are polished up, it wouldn't be difficult to assign Jack Hudson his part in the 'New Hunting of the Snark.'"

"Naturally you will represent the bellman, sir!" observed Hubert, his eyes dancing with fun.

"I suppose so," assented the lieutenant; "but I shall content myself with only angrily tingling my bell every half-hour for the sake of recording the time."

"As you are the bellman, sir, you must listen to my quotation," said Hubert, with a mischievous look at his superior. "You can make any comments afterwards that you please.

'This was charming, no doubt, but they shortly found out

That the captain they trusted so well

Had only one notion for crossing the ocean,

And that was to tingle his bell.

He was thoughtful and grave—but the orders he gave

Were enough to bewilder a crew;

When he cried, "Steer to starboard, but keep her head

larboard,"

What on earth was the helmsman to do?

Then the bowsprit got mixed with the rudder sometimes,

A thing, as the bellman remarked,

That frequently happens in tropical climes,

When a vessel is, so to speak, "snarked."'"

"You young monkey!" exclaimed Mr. Knowles, very much tickled with the absurdity of his midshipman's retort; "you've torn my character into shreds and tatters, and the crew will probably mutiny!"

Sounds of suppressed laughter and giggling from abaft all attracted the lieutenant's and midshipman's attention at this moment, and turning round suddenly they saw, much to their astonishment, the stalwart bronzed steersman endeavouring vainly to stifle a fit of laughter by stuffing a huge red handkerchief into his mouth.

"For goodness' sake, man, have your laugh out," cried the lieutenant half angrily; "you're as purple in the face as an old turkey cock."

The coxswain willingly obeyed, and immediately burst into a loud series of guffaws, which mightily astonished the rest of the crew, who had not overheard their officers' conversation, ending up by shouting incoherently, "That was a good un, anyhow!"

"Are you off your chump, mate, or what?" asked Dixon. "Perhaps you finds the sun a bit hot on the back of your head there in the starn-sheets, and had better let me—"

"Sail on the starboard bow!" pealed at this minute from the look-out man who was stationed forward.

Intense excitement at once reigned fore and aft the pinnace, for the strange sail might very well prove to be a slaver.

"HOW does the sail bear?" shouted the lieutenant to the look-out man.

"About two points on the starboard bow, sir."

"I see her! I see her!" exclaimed Hubert, who had been straining his eyes in the hopes of getting a glimpse of the stranger. "Look just abaft the foremost awning stanchion."

"I've got her now," said Mr. Knowles, who was gazing through a telescope. "She is a large dhow, I can see that, and she is running free in the direction of Socotra."

"Do you think she is a slaver, sir?"

"It is quite impossible to say at present. Of course she may be a trader making for the island in the ordinary course of business."

"I doubt it, sir. You may depend upon it she has got no end of slaves stowed away on board."

"We shall soon know, for as soon as she has sighted us she will try and evade us if she is a slaver."

"She is carrying a press of sail," observed Hubert, as he glanced at the dhow through a spy-glass, "and has evidently got a stronger breeze over yonder than we have, judging from the way she is bowling along."

"There is no doubt about that," said Mr. Knowles, "and we must put all the pressure we can upon the engines. Keep her head E.S.E., coxswain."

"Ay, ay, sir!"

The pinnace now tore along at a very much increased rate of speed. The south-westerly breeze seemed to be momentarily increasing in strength, and ever and again the crest of a wave broke over the boat's weather bulwarks in a shower of spray.

"Dis put de galley fire out in less dan no time, I tink," observed Ugly-Mug, showing his white teeth in a wide grin; "and den how can dis chile boil de cocoa for ship company supper? De gale ob wind and de ship cook am neber de best ob friend; dat for sartin, God help 'em!"

"Never mind the cocoa at present, old ebony-shanks," said Hudson, the marine, as he began overhauling his rifle; "we've got a boat-load of niggers to set free over yonder, and you'll find the bullets whizzing about your frizzed old noddle before very long."

The Krooman drew himself up angrily and defiantly.

"My golly!" he ejaculated, almost choking with rage, "what de impidence you speak ob nigger like dat, Mr. Lobster Marine? I tink black bery good colour, else why de Englishman always wear de black clo' when he get the chance? Dat I ask you."

"Had you there, mate, I think!" laughed Dixon; "after all, it ain't fair to make fun of Ugly-Mug's black skin, for he can't help what he was born with, can he?"

"Oh, I don't want to make fun of him," answered the marine lightly; "he's a decent chap enough, though with an onnatural look about the gills. I shouldn't advise him to call me sich a thing as a lobster agin though, or I may be under the painful necessity of pitching him overboard by the scruff of the neck."

Ugly-Mug, who was an athletic, muscular fellow, was about to make an angry rejoinder to this speech, when silence was enjoined by the first lieutenant, and an order was passed round to load the bow gun.

"Overhaul your rifles and cutlasses, lads!" said Hubert; "you may depend upon it we're in for a scrimmage."

"The sooner the better, sir," said Dixon, with a glance of approval at the middy; "and we're the lads will teach them thieving, kidnapping Arabs a thing or two, you bet your life!" And so saying the seaman drew his glittering cutlass from its sheath, and began testing its edge with his finger.

"That'll do," he said in a satisfied tone; "this here cutlash has seen some service in its time, and it'll see some more unless Charlie Dixon gets stowed away in Davy Jones's locker, and then he'll be out o' the running, and no mistake!"

"I'd back you against half a dozen Arabs, Dixon!" said the middy, glancing admiringly at his coxswain's wiry, muscular figure and long brawny arms. "I don't think they'd stand much chance against you!"

"Pretty good odds that, Mr. Ashley," answered the seaman grimly; "but I ain't yarning at all when I tell you that I'd sooner have to do with six Frenchmen than with six Arabs, and I'd a deal rather tackle a dozen Portugooses than six Frenchmen!"

The middy laughed.

"I don't suppose you ever had a set-to with a dozen Portuguese, had you, Dixon? It must have been glorious fun if you had!"

The coxswain winked, and looked mysterious.

"Once upon a time, sir, as the story books say, I did have a rough-and-tumble scrimmage with a good dozen of Portugooses! I think there was more of 'em than that, but I hadn't time to count the land-sharks. 'Twas at Goa the row came off, and it warn't no fault o' mine. But there, I mustn't be spinning yarns now, or I'll have the commanding officer a jumping down my throat, and that's a thing I ain't accustomed to, Mr. Ashley, as you know."

"All right, Dixon, I'll let you off now; but you must promise to tell me the story some other time."

"It's a mighty inconvenient thing to make promises, I've always found, Mr. Ashley; they're rocks that I give a wide berth to as a rule, for fear of broaching-to and getting wrecked upon 'em."

"Is the twelve-pounder loaded?" sung out Mr. Knowles at this juncture.

"She's all ready, sir," replied Dixon, "and all the rifles are loaded too."

Hubert now turned his attention once more to the chase, and was surprised to find how fast the pinnace had been overhauling the swiftly sailing dhow. The latter was still staggering along under two lofty lateen sails, and appeared to be holding tenaciously on the same course. She was evidently a large, well- found vessel, and there was no doubt that her crew must by this time have perceived that they were being chased by a man-of-war's boat. They made no attempt, however, to shorten sail, although the wind had risen to a single-reefed topsail breeze, which must have strained their canvas and cordage to its utmost capacity.

The grey serrated mountains of the island of Socotra had now risen above the horizon to the eastward, and several small fishing craft were observed cruising about in the neighbourhood of the land. The sun had begun to sink down towards the western horizon, and its powerful rays had abated much of their fierceness; but the near approach of evening was a source of anxiety to Mr. Knowles, who knew that as soon as the brief tropical twilight was merged into night, the dhow he was chasing would stand a very much better chance of escape.

"I'm afraid she's not within range yet," he said at length, "but I think you might try and throw a shot across her forefoot, Dixon."

A few moments later the little gun discharged its iron messenger, but the shot plunged into the waves a long way short of the dhow, and then ricochetted away in a different direction, throwing up miniature columns of water as it did so.

"It's no good. Belay firing!" ordered the disappointed lieutenant; "our shot are too precious to be thrown away."

The dhow still sailed sullenly on, the firing of the gun having produced no effect upon her crew. Every moment her speed was increasing as the breeze freshened, and her canvas still gave no signs of yielding to the blast.

Hubert turned impatiently to Mr. Knowles, his fingers toying with the handle of his dirk.

"I know quite well what you are going to say, Mr. Ashley," said the lieutenant, with a smile; "you wish to inform me that you think that the dhow is drawing away from us, eh?"

"Isn't it too bad, sir? It will be blowing half a gale soon, and she'll escape us to a certainty!"

"I intend to capture her, nevertheless," said Mr. Knowles in a resolute tone; "she may escape us for a time, but our prize she shall be, and before twenty-four hours have elapsed too."

"I am glad to hear you say that, sir," responded our hero in a relieved tone, "for I was afraid it was going to be a wild-goose chase. You feel sure that she is a slaver now, don't you?"

"No doubt about it, I should say. Ugly-Mug had better brew some cocoa now for the crew, so that they may have their supper in good time."

As the men joked and chatted over their evening meal, which was frequently interrupted by copious drenchings of spray from the rising sea, the sun descended to the horizon in a flaming background of crimson sky, above which were suspended vast purple bars of storm-charged clouds, the serrated edges of which glowed with a bronze-like radiance which gradually faded away into an ashen grey. To the eastward the bold purple masses of the lofty island of Socotra stood out prominently in the evening light; the reflection of the western glories illuminating the sky above the jagged topmost heights with a warm carmine glow, which momentarily grew fainter and fainter as the intenser lights diminished and paled before the onward march of the fast- approaching sombre twilight.

Like a spectral vessel manned by a ghostly crew, the great dhow glided swiftly along the southern coast of Socotra, which was now being wrapped in gloom, pursued at an ever-increasing distance by the pertinacious pinnace. At length a rocky projecting tongue of land, almost invisible in the fast-gathering darkness, swallowed up the tall lateen sails, and the dhow seemed to vanish mysteriously and unaccountably from sight.

As the pinnace neared the land the wind perceptibly fell, and the spirits of our friends rose in proportion.

"My only fear now," said the first lieutenant to our hero, "is that the captain of the dhow has friends in the island who will assist him in secreting his vessel. The inhabitants of Socotra are a set of piratical robbers, I know very well."

"Have you ever landed there, sir?"

"Yes, several times when I was out on this station previously. I did a good deal of surveying work here at one time, and consequently am well acquainted with the navigation. I have a very shrewd suspicion as to the spot that slaver will anchor in."

"Then we could cut her out under cover of the darkness!" exclaimed Hubert with great animation. "What a spree it will be, to be sure!"

"That is my intention at present, certainly," said Mr. Knowles, smiling at the middy's enthusiasm; "but, of course, circumstances may arise to prevent this plan being carried out. We must be prepared for any eventuality."

Night had now fallen upon the scene, and it was intensely dark. The pinnace was slowed down to half speed, and every light on board—with the exception of the one that illuminated the compass—was extinguished, whilst the stokers took necessary precautions to see that no tell-tale sparks were emitted from the funnel. Absolute silence prevailed, and the only sound that broke the stillness was the low throbbing of the screws and well-oiled machinery, and the hiss of the little vessel's stem as it cut its way through the phosphorescent waters. A twinkling light here and there betrayed the whereabouts of the land; but Mr. Knowles had taken bearings of some of the promontories, and consulted the chart before night fell, and knew exactly how near he could venture to the treacherous shore, having himself taken the tiller, and sent the coxswain forward to take a spell of rest.

As my readers may suppose, Hubert's nerves were wound up to an extreme tension by the exciting and adventurous incidents in which he had thus suddenly become involved, and which at any moment might develop with scarcely a moment's notice into a bloodthirsty hand-to-hand conflict with the cruel and savage members of a slaver's crew. In accordance with the first lieutenant's wishes, he was crouching down in the stern-sheets of the pinnace, within hearing of a whisper from his superior. The middy could hear his heart beating with suppressed excitement as he listened anxiously for the faintest sound that might indicate the proximity of the slaver's crew; one hand grasping the butt of a loaded revolver which was stuck into his belt, and the other nervously handling the hilt of a cutlass which Dixon had lent him, as a more serviceable weapon than a middy's dirk, which is more ornamental than useful.

The indigo sky was now strewn with most brilliant stars, and there was perceptibly a little more light than there had been in the earlier part of the night. The wind and sea had both very much gone down since sunset, and the reflections in the dark sea of the gorgeous orbs of heaven were beautiful beyond description as they flickered and danced in the trough of the phosphorus- crested waves.

"Creep forward, Mr. Ashley, and tell the coxswain to stand by to come to an anchor as silently as possible," whispered the lieutenant at length. "Tell the stokers, too, to be ready to shut off steam when I give them the word."

Hubert as silently as possible delivered these orders, and, as he regained the stern-sheets, saw that the first lieutenant was gradually putting the helm over, as if he wished to steer the pinnace in towards the coast.

"I wish this water was not so phosphorescent; it may betray us," the lieutenant muttered to himself.

The pinnace still glided on through the darkness at a reduced pace, and Hubert fancied that he could detect right ahead a huge barrier of lofty black cliffs beetling up in gloomy precipitous masses, and looming ominously out against the starlit sky.

Not a sound, however, came from the shore, and not a light was now visible. A mysterious silence reigned supreme, and the whole island seemed plunged in a Cimmerian darkness as profound as it was unaccountable.

Hubert felt an eerie feeling creeping over him, such as he had once experienced when crossing at midnight a churchyard that was reputed to be haunted.

"Shut off steam!" suddenly whispered Mr. Knowles.

Scarcely were the words out of his mouth than the pinnace bumped with terrific force into some obstruction ahead, which had the immediate effect of dismounting her bow gun; and the shock had not died away when a chorus of angry shouts and yells rose in a piercing and discordant clamour into the still night air. Then the sombre darkness was weirdly lit up by the ruddy death-flames that gushed simultaneously from several musket barrels.

THE flashes of the tell-tale muskets at once revealed to the astonished gaze of those on board the pinnace the great black outline of an immense dhow—doubtless the very one they had been so assiduously chasing all the afternoon.

Quite by chance Mr. Knowles had run the pinnace, stem-on, right into her; and it was evident that those on board the native vessel had been keeping a careful watch, and were prepared for an encounter with the Spiteful's men.

If any doubt had previously existed in the lieutenant's mind as to the character of the dhow, it was now rudely dispelled by the whizz of a hostile bullet past his ear.

Fortunately this first volley from the Arabs had been fired somewhat wildly, and most of the slugs passed harmlessly over the heads of the pinnace's crew.

"Hang on to her there forward!" thundered Mr. Knowles, as he levelled his revolver and fired several shots on board the dhow. "Stand by to board, my brave lads!"

The pinnace, however, had recoiled with bows somewhat stove in from the shock of the violent concussion, and it was necessary to give the engines several turns ahead in order to regain the dhow's quarter. Meanwhile a smart fire was kept upon both sides; Hudson, the marine, especially distinguishing himself by picking off an Arab every time he fired, in spite of the darkness that prevailed. Close beside him in the bows stood the black figure of Ugly-Mug, who was yelling like a distracted demon and waving a portentous-looking cutlass with vehement gestures over his head.

As for our hero, the sudden excitement had proved rather too much for his youthful nerves, and he had, within a few seconds of the sudden rencontre with the slaver, wildly fired away every charge in his revolver; only one of which took effect, wounding the Arab captain in his sword-arm.

With a crash the pinnace was now once more alongside her huge enemy, and as lanterns were now flashing on board both vessels, it was possible to see in a feeble, glimmering way what was going forward.

All the starboard quarter and waist of the dhow was black with a crowd of ferocious-looking Arabs and half-breeds, many of whom seemed to be well-armed, and therefore capable of offering a determined resistance to the pinnace's crew. Several had, however, been already rendered hors de combat by the fire from the pinnace. In spite of this circumstance the Arabs largely outnumbered their opponents, a fact which emboldened them to show a most defiant front to Her Majesty's jack tars.

And now arose the terrible din of a hand-to-hand conflict. Spear and scimitar clashed with the well-tempered cutlass; pistols and revolvers exchanged deadly shots with each other; clubbed rifles and muskets wielded by brawny arms were dealing ferocious resounding blows as they whirled and fell; and high above all this warlike clamour rose shrieks and yells of defiance, mingled with the heartrending moans and groans of the injured and dying.

Hubert had quite recovered his presence of mind by the time that the pinnace had once more dashed alongside the dhow, and, cutlass in hand, had rushed forward with great impetuosity to endeavour to cut his way through the swarthy threatening horde of fierce Arabs who resolutely lined their bulwarks. Close to the middy's side, Dixon pressed on, his sleeves rolled up to his elbows, and his death-dealing cutlass doing such havoc amongst the enemy that they already began to give way before him. In the bows of the pinnace the marine and Ugly-Mug were fighting side by side like the most devoted chums; the former dealing crushing blows with his clubbed rifle, which he swung around at the full reach of his immensely long arms, whilst the Krooman slashed away valiantly with a cutlass, although he was already wounded in the chest by an Arab spear.

Mr. Knowles, supported by Fred Morgan and Parker, endeavoured to force his way in over the high quarter of the slaver, but was twice repulsed by overpowering numbers; upon which he and his allies joined our hero and Dixon, who were fighting in the waist, and the four made a desperate and simultaneous rush forward, and in spite of the strenuous and fanatical resistance offered by the Arabs, succeeded in planting their feet firmly upon the slaver's bulwarks.

"Down with the ruffians!" yelled Dixon, as his cutlass flashed hither and thither amongst the retreating slaver's men; "there's some fighting in the copper-coloured sarpents still."

"That you may depend, mate," shouted Parker, who was now fighting at Dixon's side; "it ain't no child's play to cross swords with an Arab when his blood is up."

The marine and Ugly-Mug had now gained a footing on the dhow's forecastle, and were gradually driving their opponents in upon the flank of those who were still endeavouring to check the onset of Mr. Knowles and his followers. The coxswain of the pinnace and the stokers had remained in charge of the boat, according to the lieutenant's orders, and were now busily employed in lashing her securely alongside the Arab vessel.

Great confusion ensued amongst the main body of the slaver's crew when Hudson and the Krooman, showering their blows right and left, and driving their adversaries before them like a flock of sheep, descended like a whirlwind upon their disordered flank. This proved the critical point of the conflict, and Mr. Knowles and Hubert at once took advantage of the circumstance to make a desperate endeavour to end the fight, and in this they were fortunately aided by the death of the captain of the dhow. This intrepid individual, in spite of the wound he had received from the middy's revolver, had been resolutely fighting at the head of his men, but on perceiving Ugly-Mug amongst the boarding party, had detached himself from the main body of his followers and rushed to single out the Krooman as an object of special attack, doubtless taking that sable worthy for a spy. Ugly-Mug, however, remained perfectly cool and collected, for he perceived that his fiery antagonist was half-mad with rage at the turn affairs were taking, and seemed hardly responsible for what he was doing. This the crafty Krooman was well aware gave him a great advantage over his enemy, and he warily defended himself for some time against the Arab's wild and ferocious attacks; and then suddenly seizing a much-coveted opportunity, when his antagonist unwittingly laid himself open to a point, drove his cutlass with all his force into the other's naked breast. The cruel sharp blade had pierced the savage's heart, and without even the utterance of a groan he fell lifeless upon the deck, close to the spot where in silent horror and terrified confusion a hundred and fifty slaves were pent up on a temporary bamboo deck, amid the reeking filthiness of a dark confined space such as pigs could not long survive in.

The remaining Arabs lost heart when they saw their leader fall dead at the victorious Krooman's feet; threw down their weapons, and begged for mercy. This, of course, was at once granted them, for Mr. Knowles was averse to shedding blood, and only too willing to grant terms to a brave foe, however ignominious their calling. The Arabs were therefore seized, promptly disarmed, and put under a guard, who had orders to shoot the prisoners should they make the least attempt to recover the dhow or make their escape.

By the greatest good fortune not a single person upon the English side had been killed in this brief though fierce struggle. Several were suffering from slight wounds and blows and contusions, but Ugly-Mug's was the only one that gave any anxiety to his shipmates, for he had lost a considerable amount of blood during his severe single combat with the Arab captain. The wound, however, was now carefully dressed by Dixon, who had some knowledge of ambulance work; and it was pronounced by the cutter's coxswain to be nothing very serious.

It was now necessary to assemble and count the unfortunate slaves. These poor, ill-used, helpless creatures were at first very much terrified by the appearance upon the scene of their white rescuers; but the lieutenant was slightly acquainted with some of the African dialects, and addressed a few reassuring words to them, which quickly assuaged their terrors, and the elder ones of the party soon recovered confidence enough to tell their miserable tale, which was of the usual revolting type—a raid by the predatory Arabs upon an unoffending and peaceful village during the absence of the major part of the male population; the seizure of a number of the inhabitants, who were yoked to one another, and driven by forced marches to the coast, suffering grievously from the want of food and water, and from fatigue and the pain of the lash. Then followed the hurried embarkation at the mouth of some river, or in the unfrequented waters of a petty harbour or road-stead, and the putting to sea under cover of night, so as to avoid the cruisers which might be in the neighbourhood. Then began the awful subsequent torture of being pent up in the stifling hold of the ill-ventilated vessel, with scarcely room to move or air to breathe, and receiving the very smallest modicum of the wretchedest food and the dirtiest water from their cruel captors, with the chance of being thrown overboard to the sharks should disease break out amongst the miserable captives, which is only too often the case during these hideous enforced voyages.

Hubert had been very fortunate in this engagement with the slaver's crew, only having had one of his shoulders contused by a rather severe blow from the butt end of an Arab musket. Very soon after the engagement had terminated, an idea occurred to our hero, which the more he revolved it in his mind, the more practicable and yet full of possible adventures it seemed to be. The difficulty, it appeared to him, would be to obtain Mr. Knowles' consent.

"I'll tell Dixon, and see what he says," said the middy to himself; "there's nobody like that jolly old coxswain of mine for giving one advice about this sort of thing."

Dixon had just finished attending to Ugly-Mug's wound when Hubert sought him out, and the coxswain saw at once, by the eager expression on the boy's face, that he had something of importance to disclose.

"Well, Mr. Ashley, I'm right glad to see you looking so lively after the scrummage, for it was pretty hot work whilst it lasted; and I know as how you did your dooty well, for I kept one eye on you as long as I could. Them thieving sons of guns kept the other one pretty busy, I can assure you, for they was as muscular and ferocious a set of haythen as I've ever set eyes upon, and I've seen a good many of the land-sharks at one time and another."

"Oh, hang the land-sharks, Dixon!" exclaimed Hubert impatiently, and not very politely; "I've got an idea!"

"You don't say so, Mr. Ashley!" said the coxswain, with a quizzical look at the middy. "Well! that is something new, isn't it?"

"My idea is this," continued Hubert excitedly, and paying no attention to his coxswain's remark; "we've got a jolly fine dhow in our possession, a fast sailer and a good sea boat, and why shouldn't we make use of her to capture other slave-dhows? We could take a small prize crew on board and do no end of mischief, for the Arabs would never suspect that we were on the look-out for them. Do you twig now, Dixon, and don't you think it's a jolly good plan?"

The coxswain scratched his head, with a mingled look of mystification and perplexity, which lasted for some seconds, and then gradually merged itself into a broad smile.

"And who is to take command of this here craft, sir, if so be as the first lieutenant agrees to fit her out as a cruiser?"

"Why, I am, of course, Dixon; how awfully dense you are to-day! It's the hot sun, I suppose! And if you would like the post, I'll make you my boatswain. We'd make a ripping lot of prize-money; that you may be sure of, and get no end of kudos from the skipper when we fell in with the Spiteful again."

The coxswain laughed.

"Oh! that's the lay of the land, is it, sir? Let's see, how would it sound? Mr. Charles Dixon, boatswain of H.M.S.—What do you mean to call the little hooker, Mr. Ashley?"

"Oh, I think the Indian Chief would be a very good name," said Hubert, after a pause.

"Mr. Charles Dixon, boatswain of H.M.S. Indian Chief," said the coxswain, with a broad grin irradiating his bronzed, manly face. "Don't sound bad, does it, sir? I think I'll take the warrant, and try and keep things shipshape for you. It'll be a rum sort of a voyage, I take it: a sort of cruise of H.M.S. Pinafore, Mr. Ashley, eh?"

"I think I shall make Morgan boatswain," said our hero laughingly, "and enter you upon the ship's books as an ordinary seaman. You're not half respectful enough for a warrant officer, Dixon. Keep things ship-shape for me, indeed! that is a rich idea of yours, and no mistake!"

"What is a rich idea?" asked Mr. Knowles, coming up at this minute.

Hubert looked a little confused at this unexpected question. He soon, however, recovered himself, and thinking it best to make a bold plunge into the subject, lost no time in laying his project before the first lieutenant, taking care to expatiate freely upon the probable good results which would follow upon such unusual tactics.

For some moments the lieutenant made no response, but looked thoughtfully upon the deck.

"You have forgotten one thing, Mr. Ashley," he said at length; "there are 150 slaves on board the dhow, so it would be impossible for you to take her upon a separate cruise."

The middy's face fell.

"I had not thought of that, sir," he said reluctantly. "Can't we get rid of the slaves somehow?"

"I don't see my way at present. They must either be landed at the Seychelle Islands or Aden."

"But you don't disapprove of my plan, sir?" asked Hubert anxiously.

"By no means. On the contrary, I give you full credit for a novel and otherwise quite practicable scheme; but still at the same time you would find it very tantalizing to be without the aid of steam or oars, if you should have a head wind to contend with, and spy a possible prize to windward."

"Oh, we should manage somehow," responded the middy, with all the sanguine confidence of boyhood.

The lieutenant laughed, and the subject dropped, for it was necessary as far as possible to see to the comfort of the unfortunate slaves. It was resolved that both vessels should remain at anchor till dawn broke, when it would be necessary to take the dhow in tow, and steer for some neighbouring port.

It was about two o'clock in the morning before Hubert felt at liberty to roll himself up in a rug and throw himself down in the stern-sheets of the launch to try and get a little sleep, after the fatigue and excitement of the night's adventures.

The first glimmering of dawn was just faintly illuminating the eastern quarter of the heavens with a cold, pallid light, when the middy was awoke by a shake from Dixon.

"We've sighted the lights of a biggish craft out there in the offing, Mr. Ashley," he said. "I thought you'd like to know about it, though I'm main sorry to cut short such a nice caulk as you seem to have been having."

HUBERT, in spite of his previous fatigue, was on the alert in a moment, for he conjectured, and not unnaturally, that some fresh adventure might be developing; and his youthful imagination immediately conjured up in connection with the strange sail that Dixon had reported wild and phantom visions of a possible privateer or colossal slaver hovering about the lonely, rock-bound coast of Socotra.

When, however, day really broke, and the sun burst forth from its regal couch of russet and gold, and permeated the sea and sky with its life-giving beams, all the middy's castles in the air were rudely dissipated, for it was at once seen that the mysterious new arrival was no other than the Spiteful herself, which, ignorant of the proximity of her steam pinnace, had been cruising on and off the island for some hours, in the hopes of intercepting the very dhow which had been captured by Mr. Knowles, and of whose existence Captain Chetwynd had been made aware through communicating with a trading dhow on the previous evening.

Great, therefore, was the surprise of the sloop's officers and ship's company when they perceived the pinnace, with a large captured slaver in tow, standing out to intercept them. The Spiteful at once fired a gun and hove-to, to await the arrival of her boat and accompanying prize.

Our hero was in high delight at the turn affairs had taken, for he now saw a prospect of being allowed by the commander to go away on a separate cruise in the captured dhow.

"Do try and get leave for me, sir," he said beseechingly to the first lieutenant, with his cheeks all aglow; "you know you said that the idea was a good one."

"Did I?" asked Mr. Knowles mischievously; "perhaps I was a little precipitate, and did not weigh the dangers and difficulties sufficiently."

The middy's face fell, but there was no time to pursue the conversation, for they were new close alongside the Spiteful. The bulwarks of the dhow were black with the liberated slaves, gazing in an ecstasy of astonishment and wonder at the—to them—strange apparition of a large man-of- war, with her menacing guns frowning out of the row of open portholes.

The Spiteful's hammock-nettings and chains were crowded with bluejackets and marines, who raised a hearty cheer when the pinnace steamed alongside. Phil Paddon was waving his cap to our hero from the gangway with the greatest enthusiasm.