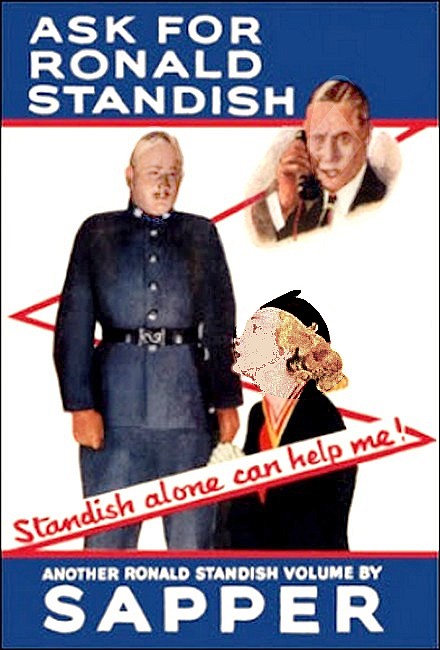

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"Ask for Ronald Standish," Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1936

with "The Music-Room"

'I'M afraid I must be terribly materialistic and dull, my dear Anne. I quite agree with you that the house ought to have a ghost, and if I could I'd order one from Harridges. But the prosaic fact remains that so far as I know we just aren't honoured.'

Sir John Crawsham smiled at the girl on his right and helped himself to a second glass of port.

'We've got, I believe, a secret passage of sorts,' he continued. 'I've never bothered to look for it myself, but the legend goes that Charles the First lay hidden in it for two or three days. The only trouble about that is, that if His Majesty had hidden in all the secret rooms he is reputed to have stayed in he'd never have had time to do anything else.'

'We must have a hunt for it one day, Uncle John,' sang out his nephew David from the other end of the table.

'With all the pleasure in the world, my dear boy. I've got a bit of doggerel about it somewhere, which I'll look up after dinner.'

'How long have you had the house, Sir John?' asked Ronald Standish.

'Two months. Incidentally, Standish, though I can't supply a ghost, I can put up a very strange story which is more or less in your line of country.'

'Really,' said Ronald. 'What is it?'

Sir John pushed the decanter to his left.

'It happened about forty years ago,' he began. 'At the time the house was empty; the tenants were abroad, the servants had either been dismissed or put on board wages. The keys were with the lodge-keeper, and two or three times a week he used to come up to open the windows and generally see that everything was all right. Well, one morning he arrived as usual and proceeded to unlock the doors of all the rooms, according to his ordinary routine. Until, to his great surprise, he came to the music-room and found that the key was missing. The door was locked but there was no key.

'He searched on the floor, thinking it might have fallen out of the keyhole; no sign of it. And so after a while he went outside, got a ladder, and climbed up to look through the mullioned windows. And there, lying in the middle of the floor, he saw the body of a man.

'The windows in that room are of the small diamond-paned type and are not easy to see through. But Jobson—that was the lodge-keeper's name—realised at once that something was badly amiss and got hold of the police, who proceeded to break open the door. And there an appalling sight confronted them.

'Stretched on his back in the middle of the room was a dead man. But it was the manner of his death that made the sight so terrible. The lower part of his face had literally been battered into a pulp; the assault must have been one of unbelievable ferocity. I say assault advisedly, since it was obvious at once that there could be no question of suicide or accident. It was murder, and a particularly brutal one at that. But when they'd got that far, they found things weren't so easy.

'From the doctor's examination it appeared that the man had been dead for about thirty-six hours. Jobson had not been to the house the preceding day, and so it was clear that the crime had been committed two nights before the body was found. But how had the murderer escaped? The door, as I've told you, was locked on the inside, which showed that the key had been deliberately taken from the outside and placed on the in. The windows were all bolted, and a very short examination proved that it was impossible to fasten them from outside the house. Therefore the murderer could not have escaped through a window and shut it after him. How, then, had he escaped?

'Wait a moment!' Sir John laughed. 'I know what you're all going to say. Through the secret passage, of course. All I can tell you is that the most exhaustive search failed to reveal one. Short of actually pulling down the walls, they did everything they possibly could, so I gathered from the man who told me the yarn.'

'And no trace of any weapon was found?' remarked Ronald.

'Not a sign. But apparently, from the injuries sustained, it must have been something like a crowbar.'

'Was the dead man identified?' I asked.

'No. That was another strange feature of the case. He had no letters or papers on him, and his clothes proved to have been bought in a big ready-made shop in Birmingham. They found the assistant who had served him some weeks previously, but he was of no help. The man had paid on the spot and taken the clothes away with him. And that, I'm afraid, is all that I can do for you in the ghost line,' he finished with a smile.

'Did the police have no theory at all?' asked Ronald.

'They had a theory right enough,' said Sir John. 'Burglary was at the bottom of it; there is some vague rumour that a lot of old gold plate is hidden somewhere in the house. At any rate, the police believed that two men broke in to look for it, bringing with them a crowbar in case it should be necessary to smash down the walls. They then quarrelled, and one of them bashed the other in the face with it, killing him on the spot. And then somehow or other the murderer got away.'

Sir John pushed back his chair.

'After which gruesome contribution to the evening's hilarity,' he remarked, 'who is for a game of slosh?'

There were a dozen of us altogether in the house-party, and everyone knew everyone else fairly intimately. Our host, a good- looking man in the early fifties, was a bachelor, and his sister Mary Crawsham kept house for him. He was a man of considerable wealth, being one of the partners in Crawsham's Cable Works. The other two were his nephews, David and Michael, sons of the late Sir Wilfred Crawsham, John's elder brother. He had died of pneumonia five years previously, and when his will was read it was found that he had left his share of the business equally to his two sons, who were to be automatically taken into partnership with their uncle.

As a result, the two young men found themselves at a comparatively early age in the pleasant possession of a very large income. Wilfred's share had been considerably larger than his brother's, and so, even when it was split into two, each half was but little less than Sir John's portion. Fortunately, neither of them was of the type that is spoiled by wealth, and two nicer fellows it would have been hard to meet. David was the elder and quieter of the two! Michael—a harum-scarum youth, though quite shrewd when it came to business—spent most of his spare time proposing to Anne Horley, who had started the ghost conversation at dinner.

The party was by way of being a house warming. Though Sir John had actually had the house for two months, the decorators had only just moved out finally. Extra bathrooms had been installed and the whole place had been modernised. But the work had been done well and the atmosphere of the place had been kept—particularly on the ground floor, where, so far as was possible, everything was as it had been when the house was built.

And especially was this true of the room of the mysterious murder—the music-room, into which everyone had automatically trooped after dinner. It possessed a lofty ceiling from which there hung in the centre a large and immensely heavy chandelier. Personally, I thought it hideous, but I gathered it was genuine and valuable. It had been wired for electricity, but the main lighting effect came from lamps dotted about the room. A grand piano—Mary Crawsham was no mean performer—stood not far from the huge fire-place, on each side of which were inglenooks with their original panelling. The chairs, though in keeping, could be sat on without getting cramp; there was no carpet on the floor, but several valuable Persian rugs. Opposite the fire-place was the musicians' gallery, reached by an old oak staircase. Facing the door were the high windows, through which Jobson had peered nearly half a century ago and seen what lay in the room.

'The bloodstain is renewed every week, my dear,' said Sir John jocularly to one of the girls.

'But where exactly was the body, Uncle John?' cried Michael.

'From what I gather, right in the centre of the room. Of course, it was furnished very differently then, but there was a clear space in the middle and that was where he was lying.'

'What do you make of it, Ronald?' said David.

'Good Heavens! My dear fellow, don't ask me to solve the mystery,' laughed Standish. 'Things of that sort are hard enough, even when you've got all the clues red hot. But when they're forty years old—'

'Still, you must have some idea,' persisted Anne Horley.

'You flatter me, Anne. And I'm afraid that the only solution I can see might spoil it as well as solve it. Providing everything was exactly as Sir John told us—and you must remember it took place a long time ago—I think that the police theory is almost certainly correct as far as it goes.'

'But how could the man get away?'

'I am quite sure they knew how he got away, but that part has been allowed to drop so as to increase the mystery. Through the door.'

'But it was locked on the inside.'

Ronald smiled.

'I should say it would take a skilled man with the right implement five minutes at the very most to lock that door from the outside, the key being on the inside. Which brings us to an interesting point. Why should he have troubled to do so? He had just killed his pal; so his first instinct would be to get away as fast as he could. Why, therefore, did he delay even five minutes? Why not lock the door from the outside and put the key in his pocket? He can't have been concerned with staging a nice mystery for future owners of the house; his sole worry at the moment must have been to hop it as rapidly as possible.'

He lit a cigarette.

'You know, little things of that sort always annoy me until I can get, at any rate, a possible solution. Why do laundries invariably send back double-cuffed shirts with the holes for the links at least an inch apart? Why do otherwise sane people persist in believing that placing a poker upright in front of a fire causes it to draw up?'

'But of course it does,' cried Anne indignantly.

'Only, my angel, because at long last you leave the fire alone and cease to poke it.' He dodged a book thrown at his head, and continued. 'Why did that man take the trouble to do what he did? What was in his mind? What possible purpose did he think he was serving? That, to my mind, Sir John, is the really interesting part of your problem. But then I'm afraid I'm a base materialist.'

'Then you don't think there is a secret passage at all?' said Michael.

'I won't say that. But I think if there had been one leading out of this room, the police would have found it.'

'Well, I think you're quite wrong,' remarked Anne scornfully. 'In fact, you almost deserve to be addressed as my dear Watson. What happened is pathetically obvious to anyone except a half- wit. These two men came for the gold plate. They locked the door to ensure they should not be disturbed. Then they searched for the secret passage and found it. There it was, yawning in front of them. At the other end—wealth. On which bright thought Eustace—he's the murderer—sloshes Clarence in the meat trap, so as to get a double share, and legs it along the passage. He finds the gold, and suddenly gets all hit up with an idea. He will leave the house by the other end of the passage. So he goes back; shuts the secret door into this room, and hops it the other way. What about that, my children?'

'Bravo!' cried Ronald, amidst a general chorus of applause. 'It's an uncommonly good solution, Anne. It gets rid of my difficulty, and if there is a secret passage I wouldn't be at all surprised if you aren't right.'

'If! My poor child, what you lack is feminine intuition. Had women been in charge of this case it would have been solved thirty-nine years and eleven months ago. I despair of your sex. Come on, children: let's go and dance. I'm tired of ancient corpses.'

The party trooped out into the hall, and Ronald strolled along the wall under the musicians' gallery, tapping the panelling.

'All sounds solid enough, doesn't it?' he remarked. 'They certainly didn't go in for jerry-building in those days, Sir John.'

'You're right,' answered our host. 'Each one of these walls is about three feet thick. I was amazed when I saw the workmen doing some plumbing upstairs before we moved in.' He switched out the lights and we joined the others in the hall, where dancing to the wireless had already started. And as I stood idly watching by the fire-place, and sensing the comfortable wealth of it all, I found myself wishing that I was a partner in Crawsham's Cable Works. I said as much to David, who looked at me, so I thought, a little queerly.

'I wouldn't say it to everybody, Bob,' he remarked, 'but I confess I'm a trifle surprised at things. I'd heard all about the new house, but I did not expect anything quite like this. Crawsham's Cable Works, old boy, have not been entirely immune from the general slump, though we haven't been hit so hard as most people. But that is for your ears only.'

'He's probably landed a packet in gold mines,' I said.

'Probably,' he agreed with a laugh. 'Don't think I'm accusing my reverend uncle of robbing the till. But this ain't a house: it's a ruddy mansion. However, I gather the shooting is excellent, so more power to his elbow. Which reminds me that it's an early start to-morrow, and I've got to see him on a spot of business. Night, night, Bob. That cup stuff is Aunt Mary's own hell-brew. I think she puts ink in it. As the road signs say—you have been warned.'

Which was the last time I saw David Crawsham alive.

Even now, after a considerable lapse of time, I can still feel the stunning shock of the tragedy that took place that night. Big Ben had sounded: National had closed down, and a general drift bedwards took place. Personally, I was asleep almost as soon as my head touched the pillow, only to awake a few seconds later, so it seemed to me, with the sound of a heavy crash reverberating in my ears. For a while I lay listening. Had I dreamed it? Then a door opened and footsteps went past my room. I switched on the light and looked at my watch: it was half-past two.

Another door opened and I heard voices. Then a shout in Sir John's voice. I got up and, slipping on a dressing-gown, went out. Below I could hear Sir John talking agitatedly to someone, and as Ronald came out of his room, one sentence came up distinctly.

'For God's sake keep the women away!'

I followed Ronald down the stairs: Sir John was standing outside the music-room in his dressing-gown, talking to the white-faced butler.

'Ring up the doctor at once, and the police,' he was saying, and then he saw us.

'What on earth has happened?' asked Ronald.

'David,' cried his uncle. 'The chandelier has fallen on him.'

'What?' shouted Ronald, and darted into the music-room.

In a welter of gold arms and shattered glass the chandelier lay in the centre of the floor, and underneath it sprawled a motionless figure in evening clothes.

'Lift it off him,' said Ronald quietly, and between us we heaved the thing clear. And a glance was sufficient to show that nothing could be done: David was dead. His shirt-front and collar were saturated with blood; his face was crushed almost beyond recognition. And one hand was nearly severed at the wrist, so deep was the cut in it.

'Poor devil,' muttered Ronald, covering up his face. 'Somebody had better break it gently to Michael. Keep everybody out, Bob. Ah! here is Michael.'

'What is it?' cried the younger brother. 'What's happened?'

'Steady, old man,' said Ronald. 'There's been a bad accident. The chandelier fell on David and crushed him.'

'He's dead?'

'Yes, Michael, I'm afraid he is. I wouldn't look if I were you; it'll do no good.'

'But in God's name how did it happen?' he cried wildly. 'What on earth was the old chap doing here at this time of night? He was with you when I went to bed, Uncle John.'

'I know he was,' said Sir John. 'We sat on talking over that tender for about half an hour, and then I went to bed, leaving him in my study. He said he would turn out the lights, and I can tell you no more. I fell asleep, until the frightful crash woke me up. I came down and found this. For some reason or other he must have been in here: he said something jokingly about the secret passage. And then this happened. Of all the incredible pieces of bad luck—'

Sir John was nearly distraught.

'I'll have that damned contractor ruined for this,' he went on. 'He should be sent to prison. Don't you agree, Standish?'

There was no answer and, glancing at Ronald, I saw that he was staring at the body with a look of perplexed amazement on his face.

'What's that?' he said, coming out of his reverie. 'The contractor. I agree; quite scandalous.'

He walked round and examined the top of the chandelier.

'Funny a chain wasn't used to hold it,' he remarked. 'Though this rope is obviously new, and should have been strong enough. What room is immediately above here, Sir John?'

'It's going to be my bedroom, but the fools put down the wrong flooring. I wanted parquet, so I made 'em take it up again. They're coming to do it next week.'

'I see,' said Ronald, and once again his eyes came back to the body with a look of absorbed interest in them. Then abruptly he left the room, and when I went into the hall, where the whole party were talking in hushed whispers, he was nowhere to be seen.

'It's that room, Mr. Leyton,' said Miss Crawsham to me between her sobs. 'There's tragedy in it; something devilish. I know it. Poor Michael! He's gone all to pieces. He adored his brother.'

And certainly the pall of tragedy brooded over the house. It was the suddenness of it; the stupid waste of a brilliant young life from such a miserable cause.

The doctor came, though we all knew it was merely a matter of form. I heard his report to Sir John.

'A terrible affair,' he said gravely. 'I must offer you my deepest sympathy. It is, of course, clear what happened: so clear that it is hardly necessary for me to say it. Your nephew was standing under the chandelier when the rope broke. He must have heard something and looked up. And the base of the chandelier struck him in the face. I am sure it will be a comfort to you to know, Sir John, that death must have been instantaneous. Of that I am certain. I shall, of course, wait for the police.'

And at that moment I felt a hand on my arm. Ronald was standing beside me.

'Come into the billiard-room, Bob,' he said in a low voice.

I followed him and threw a log on the dying fire. Then in some surprise I looked at him. Rarely had I seen him more serious.

'That doctor is a fool,' he said abruptly.

'Why? What makes you say so?' I asked, amazed. 'Don't you agree with him?'

For a space he walked up and down the room, his hands in the pockets of his dressing-gown. Then he halted in front of me.

'David's death was instantaneous all right; I agree there. But he wasn't standing underneath the chandelier when it fell.'

'What was he doing then?'

'He was lying on the floor.'

'Lying! What under the sun do you mean? Why was he lying on the floor?'

'Because,' he said quietly, 'he was dead already.'

I stared at him in complete bewilderment.

'How do you make that out?' I said at length.

'That very deep cut in his hand,' he answered. 'Had he received that at the same time as he received the blow in the face it would have bled profusely, just as his face did. Whereas, in actual fact, it hardly bled at all. There are some other scratches, too, obviously caused by breaking glass which show no signs of blood. And so I say, Bob, that without a shadow of doubt, David Crawsham was already dead when the chandelier fell on him.'

'Then what killed him?'

'I don't know,' said Ronald gravely. 'But it is a significant point that if you eliminate the chandelier, David's death is identical with that of the man forty years ago. Both found lying in the centre of the room with their faces bashed in.'

'Do you mean that you think there's something in the room?'

'I don't know what to think, Bob. If by something you mean some supernatural agency, I emphatically do not think. That wound was caused by a very material weapon, wielded by very material power.'

'You think it quite impossible that for some strange reason the wound in his wrist did not bleed? That all the blood that flowed came from his face?'

'I think it quite impossible, Bob, that those two wounds were administered simultaneously.'

'His face would have been hit first,' I pointed out.

'By the split fraction of a second. Damn it, man, his hand was almost severed from his arm. He ought to have bled there like a pig.'

'In that case what are you going to do about it?'

He again began to pace up and down the room.

'Look here, Bob,' he said at length, 'as I see it, there are two possible alternatives. The first is that somebody murdered David by hitting him in the face with some heavy weapon. He then placed the body on the floor under the chandelier and, going up above to the room without floor boards, deliberately cut the rope.'

'But the rope wasn't cut,' I cried. 'It was all frayed.'

'My dear man,' he answered irritably, 'use your common sense. Would any man be such a congenital fool as not to fray out the two ends after he'd cut the rope? The whole thing must appear to be an accident. The top end which I went and had a look at is frayed just like the bit on the chandelier. But that proved nothing. It's what you would expect to find if it was an accident or if it wasn't. That's the first alternative. The second is, I confess, a tough 'un to swallow. It is that something—don't ask me what—struck David in the face with sufficient force to kill him. He fell where we found him, and later the rope supporting the chandelier broke, and the thing crashed down on him.'

'But if something hit him, not wielded by a human agency, that something must still be in the room,' I cried.

'I told you it was a tough 'un,' he said. 'And the first isn't too easy either. The blow wasn't on the back of the head. He must have seen it coming; he must have seen the murderer winding himself up to deliver it. Can we seriously believe that he stood stock still waiting to be hit? It's a teaser, Bob, a regular teaser.'

'Well, old man,' I remarked. 'I have the greatest respect for your judgement, but I can't help thinking that in this case you're wrong. Who could possibly want to murder David? And though I realise the force of your argument about the wound in his wrist, it's surely easier to accept the doctor's solution than either of yours.'

'Very much easier,' he agreed shortly, and led the way back into the hall. The police had arrived and were taking notes in readiness for the inquest; the doctor had already left. The women had all gone back to their rooms. Only the men, with the exception of Michael, still stood about aimlessly.

I wondered if Ronald was going to say to the police what he had said to me, but he did not mention it. He gave his name, as I did mine—but as they obviously agreed with the doctor that the whole thing was an accident, the proceedings were merely a matter of routine.

At length they departed, having carried David's body to his room. And after a while we drifted away. The first streaks of dawn were beginning to show, and for a time I stood by the window smoking. And when at last I lay down it was not with any thought of sleeping. But finally I did doze off, to awake in a muck sweat from a nightmare in which some huge black object had come rushing at me out of space in the music-room.

The result of the inquest was a foregone conclusion. The building contractor produced figures to prove that the rope which had been used was strong enough to carry a weight twice as great as that of the chandelier, and that therefore he could not be held to blame for what must evidently have been a hidden flaw.

And so a verdict of accidental death was brought in, and in due course David Crawsham was buried. Only his aunt remained unconvinced, maintaining that there was a malevolent spirit in the room who had cut the rope deliberately. And Ronald. He did not say anything; on the face of it he acquiesced with the coroner's finding. But I knew he was convinced in his own mind that the verdict was wrong. And often during the months that followed I would find him with knitted brows staring into vacancy as he puffed at his pipe. But at last in the stress of other work he forgot it, until one day Michael caught Anne at the right moment and they became engaged. Which was the cause of our being again invited by Sir John to a party to celebrate the event.

The guests, save for ourselves and Anne, were all different from those who had been there when the tragedy occurred, and somewhat naturally no mention was made of it. The music-room was in general use, but there was one alteration. The chandelier had been removed.

'My sister insisted on it,' said Sir John to me. 'And I think she was right. A pity though in some ways; of its type it was very fine.'

'Have you got any farther with finding the secret passage?' I asked.

He shook his head.

'No. Since the poor boy's death I haven't given the matter a second thought. What a ghastly night that was. I believe I've still got the paper somewhere,' he said vaguely.

But one thing was clear; whatever Sir John had done, Ronald was giving it several second thoughts. Returning to the scene of the accident had brought the whole matter back to his mind, and I could see he was still as dissatisfied as ever.

'Not that it cuts any ice practically,' as he said. 'For good or ill, David was killed by the chandelier falling on him, and by no possible means could that verdict be shaken. Moreover, it would be a grave mistake to try and shake it now; the only result would be to upset Sir John and his sister, and lay oneself open to a severe rap on the knuckles for not having spoken at the time. But I'd give a lot, Bob, to know the truth about that night.'

'Well, you're never likely to, old man,' I answered, 'so I'd give up worrying.'

Which was where I went down to the bottom of the class; though even now the thing seems impossible. And yet it happened—happened the very evening I left. Ronald, who had stayed on, told me about it when he got back to London. Told me in short, clipped sentences with many pauses in between. Rarely have I seen him more savagely angry.

'I'm not a rich man, Bob, but I'd give ten thousand pounds to bring that swine to the gallows... Who?... Sir John Crawsham... He murdered David and, but for the grace of God, he'd have got Michael... There's only one thing to be said in his favour, if it can be regarded in that light; it was, I think, the cleverest scheme I have ever come across.

'We were all sitting in the hall after dinner last night, and the conversation turned on the secret passage. After a while, Sir John was prevailed on by Michael to go and get the paper on which the clues were supposed to be written, and Anne and Michael went into the music-room and started to try to solve it. I was playing bridge and could not go with them, and I'd have liked to.

'Suddenly, I heard Michael give a shout of triumph, and by the mercy of Allah I was dummy. Otherwise—'

He bit at his pipe angrily.

'I got up and went to the door of the music-room; Michael was standing in the right-hand inglenook, his hands on the panelling above his head, with Sir John beside him.

'"He's got it," cried Anne triumphantly, and there came a loud click. And then, Bob, number two solution flashed into my brain and I acted mechanically. I think some outside power made me move; I don't profess to say. I got to Michael, collared him round the knees and hurled him sideways, just as the panel slid open and out "something" whizzed over our heads.'

'Good God!' I muttered. 'What was it?'

'The most wickedly efficient death-trap I have ever seen. As the door opened, it operated a catch in the roof of the passage behind it. As soon as the catch was withdrawn, a jagged mass of iron weighing over sixty pounds was released, and, swinging like a pendulum on the end of a chain, hurtled through the opening at a height of about five feet from the ground. Anyone standing in the opening would have taken it in the lower part of the face, and literally been hit for six.

'We stood there white and shaking, watching the thing swing backwards and forwards. As it grew slower we were able to check it, and as it finally came to rest, the door shut. The room was normal again...

'I won't bore you, Bob, with a description of the mechanism. That it was of great age was clear; it had been installed when the house was built. Anyway, that's not the interesting point; that began to come in on me gradually. I suppose I was a fool; one is at times. But for a while the blinding significance of the thing didn't strike me. Then suddenly I knew... Involuntarily, I looked at Sir John; and he was staring at me... For a second our eyes held; then he looked away... But in that second he knew that I knew...'

Ronald rose and helped himself to a drink.

'I may be dense,' I remarked, 'but I still don't quite see. It is clear that that is the thing that killed David, but even then there's no proof that Sir John was aware of it. From what you tell me, the door shut of its own accord.'

'As you say, that is the thing that killed David. As it killed that man forty years ago. And it lifted the body through the air with the force of the blow, and deposited it in the centre of the room. So much is obvious; the rest is surmise.

'Let us go back a little, Bob, and put a hypothetical case. And let us see how it fits in. A certain man—we will call him Robinson—was senior partner in a business. But though the senior, he drew but little more money from it than his two nephews. Which galled him.

'One day, Robinson happened to hear of a certain house—it is more than likely he got hold of some old document—which contained a very peculiar feature. It was for sale, and little by little a singularly devilish scheme began to mature in his mind. He studied it from every angle; he tested it link by link; and he found it perfect.

'He gave a house-warming party, where he enlarged upon an unsolved murder that had taken place years before. And late that night, after everyone else had gone to bed, he sat up with his elder nephew. After a while he turned the conversation to the secret passage, and they both went into the music-room to look for it. Robinson, in spite of his statements to the contrary, knew, of course, where it was. And very skilfully, by a hint here and a hint there, he let his nephew discover it, as he thought, for himself. With the result we know.

'Had it failed, Robinson's whole plan would have failed. But no suspicion would have attached to him. He knew nothing about this infernal device. It did not fail; there in the centre of the floor was one of his partners dead. Robinson's third had become a half.

'Quietly he goes upstairs and gets into pyjamas. Then he cuts the rope of the chandelier. You see, the essence of his scheme was that the death trap should not be discovered; he wanted to use it just once more. For the whole is much better than a half. I've told you how he did it; fortunately without success.'

'But can't you go to the police, man?' I cried.

'What am I to say to 'em? What proof can I give them now that David was dead before the chandelier fell on him? Exhumation won't supply it; this isn't a poison case. I merely lay myself open to thundering damages for libel. Why, if I knew it, didn't I speak at the time?'

'How I wish you had!'

'Robinson would still have got off. Even if the chandelier hadn't killed David, it had fallen accidentally, and he knew nothing about the other thing.'

'I suppose it isn't possible that it did fall accidentally, and that Sir John did know nothing about the other thing?'

Ronald gave a short laugh.

'Perfectly possible, if you will answer me one question. Who replaced the weight in position?'

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.