RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Poliopolis and Polioland, 1900

James Macdonald Chaney

BUT few, even among the more intelligent, have any clear conception of the appearance and apparent movements of the heavenly bodies as seen from the North Pole. This is true, even of the simplest of these things, as the six months presence and absence of the sun.

In this narrative, great care has been exercised that all the statements of the positions, and real or apparent movements of the sun, moon, planets and stars, shall be astronomically correct. By this is meant that when it is stated that on a given date the moon appeared in one place and a certain planet in another, they were really in the very place in the heavens indicated at that hour.

Independence, Mo., Aug., 1900

J. M. C.

IT may seem like fiction, of an incredible character, to speak of a visit to the North Pole.

Ever since it was known that the earth is round, and that it revolves on its axis, men have been desirous of visiting the Polar regions. Many efforts have been made to reach it. Men skilled in science and navigation, backed and aided by men of wealth, have fitted out expeditions and spent weary months and years in a vain effort to accomplish that end. Some have never returned to tell of their success or failure. While they failed to reach the pole, yet their efforts were not fruitless. Many, and valuable discoveries were made. These acted as guides to aid those who should make subsequent efforts.

So marked were the failures of those who had every aid that science and wealth could afford, that a man, without either of these aids, who should seriously contemplate making an effort to reach that inaccessible region, would not be willing to make his purpose public.

But it may be asked, how could his purpose be kept secret? How could he keep from others, the knowledge of his preparations for such a work? Men are employed and paid good salaries, whose sole business is to discover such news and report for the daily paper. Do we not already know that soon we shall be able to send messages across the ocean without wires? Have we not now the knowledge that it is only a question of time when we shall hold communication with the inhabitants of Mars? That we shall soon cease to travel by the slow, dusty railroad, and voyage through the domain of the feathered tribe?

It has been said that the Wizard would not have invented the phonograph, but for the alertness of the newsmonger, the interviewer. It has been thus reported. His finances were inadequate for his needs. To obtain means to carry on his inventions, he sent a partner on a lecturing tour. Just before he started, the Wizard had been experimenting with the telephone. He attached a pin to the diaphragm and when one from the other end would talk, he held his chin to the end of the pin, and distinctly felt the pricks caused by the vibration of the diaphragm. He reported his experiment to his partner, telling him that these pricks were the result of sound waves, and if these could be caught and fixed, he believed they could be reproduced, and thus he would have a "talking" machine.

The partner started on his lecturing tour, having appointments in different cities. The first was in Buffalo. After the lecture, an interviewer made him a visit, to whom he told the Wizard's experiments, and what might result from it. In one of the dailies the next morning, on the first page were great headlines, announcing the most wonderful invention of the century, a veritable Talking Machine. Its wonderful possibilities were portrayed in a vivid and fascinating manner. The lecturer was besieged by a host of interviewers and capitalists. The poor fellow did not know what to do. He was not, however, long in determining. He cancelled all his appointments for lectures, hastened home, told the Wizard he must drop everything else, and perfect the talking machine. The great inventor had almost forgotten about his experiments with the diaphragm. He had not seriously contemplated making an effort in that direction, at least for a time. But he heeded the suggestion, went to work, and a crude phonograph was the result, since perfected so that it is, indeed a most wonderful machine.

But man is a bundle of inconsistencies. This is true of the newsmonger. While at one time they will convert a molehill into a mountain, at another, they seem unable to see a veritable mountain, though its peak penetrates the clouds. We see an illustration when Morse invented the electric telegraph, or rather, when he made practicable the discovery of that wonderful man of science, Prof. Henry. For a time, he could find no one to take an interest in his invention. He could demonstrate its wonderful possibilities, its vast utility, especially to the government in time of war. In a moment, news could be sent to great distances.

But Morse was almost driven to desperation in his vain efforts to induce the government to make an appropriation to test his apparatus between Washington City and Baltimore. When he had given up all hope of the passage of the bill by congress, to aid him, and had gone home, his hopes blasted, and at a late hour had sought repose in a sleepless bed, in the dead hours of night a sympathizing friend rang his door bell and made the announcement to him that, at the last hour, the bill granting him aid, had passed.

The wireless telegraph affords another illustration. It is difficult to calculate its possibilities and value. Mahlon Loomis, an American citizen, on the 30th of July, 1872, obtained letters patent for his wireless telegraph. He demonstrated its working for a distance of twenty miles. He sought government and private aid for putting it into practical use. "He met with jeers, rebuffs, and opposition alike from the scientist, the capitalist and especially the telegraph companies." He succeeded in demonstrating its practicability for a distance of four hundred miles. Yet Loomis and his inventions were forgotten until a young foreigner made a similar invention, and now the earth resounds with praises to Marconi, and his wonderful method of doing precisely what our own Loomis accomplished so many years ago.

It need not, then, be a matter of surprise that Gus Heins determined that the world should not know of his purpose to make an effort to reach the North Pole.

IT was while attending college at — in the year 18—, that I first met Gus Heins.

He was a machinist, skilled in the use of all kinds of tools, and kept a sort of general repair shop. It would be difficult to name a machine that Gus could not repair. He had a work bench by a large front window, and almost daily I could see him at work as I passed on my way to and from college. His general appearance was striking and pleasing. He was young, not more than 25. His height about five feet eight inches. His weight about 160 pounds. He had a round, full face, and a very pleasing countenance. He wore side whiskers cut rather high. His hair was light in color. My first visit to his shop was the day before Thanksgiving. One of my skates was in need of repairs. He received me with a smile, and when he had examined my skate, he said he could supply what was needed, but that I could not get it until Friday. This was a disappointment, as the ice was in a good condition for skating, and I wished to enjoy the sport on Thanksgiving day. The screw, used for tightening the skate was broken. The screw was right hand on one end and left hand on the other. He said it would not require much time to make it, but he was very busy at that time. But sympathizing with me in my disappointment, he said I should have the skate at 8 o'clock that evening. He said he did not work for people by lamplight, but in my case he would do so.

I thanked him, and at the hour appointed, I called and my skate was ready. I asked the charge. He said, "Oh, I shall not charge you anything for that. But some evening when you have leisure, I shall be greatly pleased if you will stop and give me some instruction about the lever, as I suppose you know all about it. I wish to fix a safety valve on a little engine, and I do not know how long the lever should be, nor how much weight to put on it to indicate a certain amount of pressure." I said, "All right; I will be here to-morrow night at seven thirty."

On Thanksgiving evening I was there at the hour named, and he gave me a hearty welcome. Adjoining his shop was another room, the door to which was open, and within was a bright light. Into this he led the way. It was his dining room, kitchen, bed room, and his sitting room. It was furnished in a plain but neat manner. On a table was a beautiful German student lamp, giving a flood of light. Neatly arranged around it, were pencils, paper, rulers, and a box of drawing instruments. A small bookcase was well filled with books, mostly of a scientific character. Among them I noticed two volumes of considerable size, "Lectures on Science and Art. Lardner." A hasty glance at these impressed me with the fact of their value to one eager for scientific knowledge.

In one of the volumes were three lectures on the lever, and the different mechanical powers. These he had carefully studied, but he was still unable to solve the problem about which he wished me to tell him. I explained to him that in levers of all three kinds there are four things to be considered. These are the long arm, the short arm, the weight or resistance, and the power. Three of these must be given, then the fourth is easily found by proportion. In all kinds of levers, the long arm is from power to fulcrum. The short arm from weight to fulcrum. Let La stand for long arm, Sa for short arm, w for weight, and p for power. These must always be so arranged that La and p, will be the extremes or means; Sa and w in the same manner. I explained to him how easy it is to remember the proportion by noting that they spell lap saw. I drew diagrams of levers of all three kinds, and he had no difficulty in securing the unknown term, and did not make a mistake in getting the proportion correctly. But when he turned to the problem of the safety valve, he was unable to decide whether it is a lever of the second or third kind. I assured him that he could regard it as either; the result would be the same. He had a counterpoise of a known weight which he intended to use. He had also determined on the distance from the safety valve to the support of the lever, which would be the fulcrum. What he wished to ascertain, was the exact place on the lever where the counterpoise should be suspended to indicate a given pressure of the steam. He first tried it as a lever of the second kind regarding the counterpoise as the power, and the steam as the weight or resistance. He then tried it as a lever of the third kind, regarding the steam as the power. The place for the counterpoise was the same in both cases. He was greatly pleased and grateful for my suggestions.

DURING the Christmas holidays, I had plenty of leisure, and almost daily stopped to talk with my new friend, Gus. The front room, where he worked, might well be called a curiosity shop. He had tools used by every kind of mechanic of which I had knowledge. He did not have to take a second thought to know the exact location of any tool needed, nor of any material for which he might have use. He did not seem to be in a hurry, but it was marvelous how speedily he performed any work. His charges were moderate, yet he made money rapidly. He would take in, daily, anywhere from five to fifteen dollars. Among his most numerous and profitable customers were ladies with jewelry to repair. When he knew what was wanted—what specific end was to be accomplished, his inventive genius seemed to enable him to know, as if by instinct, the means by which it could be accomplished. I saw this illustrated in a manner that, to me, was very astonishing. An amateur astronomer, having a telescope with a four inch objective, and supplied with an equatorial movement, brought the instrument to him for some small repairs. I happened to be present when it was brought. Gus had no knowledge of telescopes, and had never seen an equatorial movement. He became very much interested in this attachment. Almost at sight, he comprehended the double movement for right ascension and declination. There were two graduated circles, one for right ascension, on which were marked the twenty four hours, the other for declination, on which were the three hundred and sixty degrees. The circle for right ascension was small, and could not be depended on for much less than fifteen minutes. The owner expressed the wish that he could read right ascension to a single minute. After a few minutes' examination, Gus, said: "I can fix a simple attachment that will enable you to read a single minute or less, with great accuracy." The owner promptly replied, "I will give you a ten dollar gold coin if you will make such an attachment." In less than a week the work was done. It would do not only what was promised, but would read down to two seconds. It was a marvel of simplicity. A heavy brass collar was fitted to the upper part of the equatorial movement, which could be made fast by a set screw. To this was fastened a quarter-inch brass rod, about twenty inches long, extending toward the object glass. On the end of this rod was an attachment having a nut in which a screw worked, having thirty-six threads to the inch. The end of this screw worked against a piece that was attached to the tube of the telescope. By turning the screw, the body of the telescope was moved away from it. The circumference of the circle in which that point would be moved would be 120 inches, or five inches for one hour. One turn of the screw would move the telescope over a space of 20 seconds. One-tenth of a revolution would move it over just two seconds.

From such feats of genius, I concluded that when Gus said he could accomplish a given work, he could do it.

He had many questions to propound in reference to specific gravity. He made many inquiries about the buoyant effort of air. I gave him the weight of air as about .31 grains per cubic inch, or 1.23 ounces per cubic foot. He had studied how a fish lowers itself in water, not by diving, but simply by changing its relative size, and thus increasing its relative weight.

His questions and conversations about balloons and fish greatly excited my curiosity. At last I asked him what he had on hand to accomplish. He replied that he would tell me under a promise of secrecy, which I readily promised.

He then told that it was his purpose to make an effort to reach the North Pole, by means of a balloon. He had carefully read all that he could find about attempts made to reach it by ships, and that all had failed, and he thought always would fail. He said that he had been thinking of it from boyhood, but had never mentioned it to anyone.

Upon hearing his statement, my emotions were of a mixed character. The first impression was that he was joking. But when he joked, there was a certain twinkle of his eye that was now wanting. His countenance had an intense expression of earnestness and determination. His gaze was fixed and his eyes seemed to be set. My next thought was that I was in the presence of a madman, a lunatic. After a silence that seemed long to me, I ventured to ask him if he really meant what he said. He assured me that his plans were arranged, and in some measure executed.

He said his father was a machinist, and had accumulated several thousand dollars, and had then gone to central Kansas and bought a large tract of land. On the land was a considerable quantity of good timber. The country was then in a prosperous condition, and he had put up a sawmill and had done well. The water supply for his engine was from a creek near by, but it was not to be depended on in case of dry weather. Therefore he concluded to sink a well in hope of a good supply of water. After he had struck rock about forty feet below the surface, he wrote to Gus, telling him what he had done, and requested him to send some iron tubing, four inches in diameter, and a drill for a three inch hole through the rock. As he sent the money, and urged him to send it immediately, Gus complied, but wrote to dissuade him from such an undertaking. But the old man persevered. He put down his four-inch tubing to the rock, and bored nearly a hundred feet through it. He had plenty of help, and drilled by means of a spring pole.

Instead of finding water, he came to some kind of a cave, and gas issued with considerable force from the top of the tubing. For this he was not prepared. He plugged the hole secure, and made an attachment by which the gas could be confined, or allowed to flow as needed.

The well supplied a quantity of gas sufficient to run his engine, and for all household purposes, including cooking and heating.

There came a succession of dry seasons, and the people became discouraged, and many moved away. All improvements stopped. Gus was the only child. His father and mother both died, and the property became his. It was about twelve miles from the railroad. His father always kept on hand a large supply of lumber, and at the time of his death there was a stock of about one hundred thousand feet, well stacked, and of every kind that would be called for, for fencing or building purposes.

Gus then took me into a back room, the existence of which I had not known. There he showed me a pattern of his intended balloon. It was about four feet in height, and two and a half or three feet in diameter. It was inflated, and capable of supporting a weight of nearly two pounds. He said he intended to devise some kind of a propeller, and a steering apparatus. The whole balloon was covered with small cords, about thirty-six in number. At the bottom was a metallic disk, about the size of a dollar. This was perforated with holes through each of which a cord was passed. About half of the cords terminated at the disk. The other half were carried down to a windlass, and there made fast. He illustrated the object of the cords and the windlass. When the balloon was floating more than a foot from the table, he wound a portion of the cord on the windlass, and the balloon began to descend, and soon rested on the table. He now slackened the cords, and at once it arose. Gus looked at me and laughing said, "That is my fish bladder."

I asked him about the engine to which he attached the safety valve. He showed it to me in one corner of the room. He used it to run a lathe.

He told me that his farm was rented to a trusty German and that after a few years he himself would remove to it, and there construct his balloon that was to carry him to the pole.

He made the startling disclosure that it was his desire that I should accompany him. Against this I made a sudden and vigorous protest. He said it would require several years for him to prepare for the voyage, and that perhaps by that time I would reconsider the matter.

AFTER leaving college, I traveled for several years for a hardware company, and did well. In the midst of a successful trip, I received an unexpected summons to return to headquarters. No explanation was given, and I was at a loss to conjecture the reason of my recall. To my great amazement, the company was going into the hands of a receiver. My employers were well satisfied with my work, and were sorry that I should be thrown out of employment. I greatly sympathized with them, but felt no special concern about myself, as I felt sure I would find no difficulty in securing another position.

On my way to St. Louis, I had to wait a short time at Sedalia for a train on the main line. As I was standing on the platform, waiting for an opportunity to enter the car, among those getting off, was a gentleman whose gaze was fixed on me. I noticed it, and wondered what could be the cause, and tried to locate him, but could not. Soon he approached me, extended his hand and called my name. As I saw his smile, and heard his voice, I said, "Why, Gus Heins, is this you?" He, too, was on his way to St. Louis. He had seen me as the train stopped, and recognized me. It had been seven or eight years since we had last seen each other. On the way to St. Louis he gave me an account of his life on his farm. He had done something in the matter of farming, but his chief work had been in the construction of his balloon and in making preparations for his voyage northward. He thought he would be ready for trial trips in a few weeks. He insisted on my accompanying him home. I told him I was not then engaged in any work, and that I might make him a visit. He asked how about my going with him on his voyage? I told him I could not consider it. His business detained him in the city a few days, and I then accompanied him to his Kansas home. When we reached the station at― we found the German there waiting for us. He had a two- horse wagon for the freight, and his son had brought a buggy for Gus. We took charge of this, and the boy rode with his father.

The home of Gus was in the edge of the timber. He had but few neighbors, the nearest being about two miles distant. Most of the settlers were Germans. The farm house was comfortable, but well filled by the family of the German, consisting of a wife, three daughters, and five boys.

Gus had his home a few hundred yards distant, in a strange looking building. It was on sloping ground, and the back part extended into the timber. At a distance, the building looked like a three story barn, with great sheds on the sides. The central portion was more than forty feet

high, and about thirty-five in width. In depth it was about forty feet. On each side were shed-like projections about fifteen feet wide. Most of one side was taken up by a workshop, except the back part, which was the kitchen and dining room. On the other side were three rooms, one for two Germans helping Gus with the balloon, one for Gus's bed room, and one vacant, which I occupied.

For the construction of such a house, a vast amount of lumber was required, but he found it there all ready for use. Gus was a good cook, and had plenty to eat. The gas supply was still sufficient for all purposes. It was amusing to hear the wife of the German describing how very "conwenient" it was for cooking, and keeping the house warm in cold weather.

The balloon was practically finished, but had not yet been tested. He had laid a pipe so that it could be conveniently filled with gas. On the third day after my arrival, he turned the gas into the balloon. He could regulate the flow at pleasure. In a few minutes it showed signs of swelling. Fold after fold would swell up. There was some danger of things getting tangled. But the force at the house was on hand, and every string was kept in position, or soon placed there if there was any sign of tangling. It was about 11 o'clock when the gas was turned on, and by noon the monster had assumed an upright position. After filling, we tested its buoyant effort and found it required 785 pounds to balance it or to support its tendency to rise. Allowing 325 pounds for two passengers, and 200 pounds for the machinery and tackling, there would be left 260 pounds for provisions and the necessary buoyant effort.

One of his helpers had often expressed a desire to accompany Gus on his journey, but Gus had made him no definite promise. The man was about my size and weight. Gus was still hoping that I would change my mind, and make the trip with him. The most encouragement I could

give him was to tell him to wait and see how the machine would perform.

The balloon was about thirty-five feet in height, and about twenty-four feet in diameter in the widest part. The lower part of the neck of the balloon tapered down from about five feet from the bottom to a little less than one foot. The envelope of strings was a curiosity. One of his helpers had been a shoemaker in Germany, but had spent some years in sail making. There were 288 cords extending from the top of the balloon down nearly twenty-five feet. At that point, two cords became one. The splicing was done in an artistic manner, and the two cords combined had fewer strands than both separately. The cords were made of a species of linen thread, not much larger than coarse sewing thread, but so strong that I found it difficult to break a single strand. These were combined so the size of the cord was about three-sixteenths of an inch. Below the splice or fork, it was about four-sixteenths. Below this the cords were reduced from 144 to 72, in the same manner. Now the size was about three- eighths. Again they were reduced to 36, and the size nearly half an inch. The size and the number of the cords made it impracticable to arrange to pass them through a disk as did the cords in the small balloon. The windlass, around which these cords were wound, was a hollow cylinder, eight inches in diameter, and four feet long. The cords themselves occupied less than eighteen inches, and the extra length was to furnish a receptacle for gasoline. The windlass was double geared with cog wheels to gain power in turning it.

Gus had given much thought to the matter of propulsion. Some of his methods of reasoning seemed to be logical. One of these was that no better mode of propulsion in the air could be devised than that which Nature has provided for birds. He carefully watched them in their flight. He took measurements of their wings, and noted their shape. He examined the wing of a dove, and compared it with the wing of a large wild turkey. He estimated the area of the dove's wing as about twelve square inches, and the turkey's about ninety-six, the latter being eight times the former. He estimated the weight of the turkey as about forty times that of the dove. While the turkey was not capable of long continued flight, yet in addition to propulsion it had its weight to sustain in the air. With his balloon, there was no weight to sustain. It was simply a question of propulsion and the resistance of the atmosphere in a calm. It was specially in a calm that he would need it, as he felt sure of a current under all ordinary circumstances at some altitude. But sometimes he might wish to sail near the surface when there was no current, and would then need propulsion. He fixed on wings, patterned after those of the dove. The extreme length was ten feet. At the widest part, about four feet, and tapering to a point. For these he had made light steel bicycle tubes in three sections for a wing, about an inch and a quarter at the largest part, and tapering. The sections were made to telescope into each other about two inches. For the lower part were similar tubes, but smaller. A third tube, like the lower one was provided for the middle, running longitudinally. These were all firmly brazed together in shape. Between these were brazed small steel rods, like the spokes of the bicycle. The wings were covered with a thin material like the body of the balloon.

For giving necessary motion to the wings, he made a fine specimen of a gas engine, for which he claimed three horse power. The chief metal in its construction was aluminum. Its weight was about thirty-three pounds. The ends of the wings had a motion of nearly four feet, and with a possible velocity of 100 flaps per minute. It was so arranged that when necessary, the motion of one of the wings could be stopped.

Several days were required for properly adjusting the engine, wings and the windlass.

When the balloon was fairly balanced, the windlass was turned, and though the compression of the balloon seemed scarcely perceptible, yet it began to descend. The "fish bladder" was pronounced a perfect success. I had warned Gus that his windlass would probably prove a failure, because, in the large balloon, it seemed probable that more power would be required to compress the balloon than to lift the weight below. In that case, the windlass would simply pull the basket toward the balloon. But it worked all right.

The steering apparatus was about twelve feet long, with an average width of five feet. It was bounded by a continuous steel tube, light but strong. It had a middle section and was covered with the same material as the wings. In the middle of the end next to the balloon was a steel tube, extending to a brass collar, through which passed a steel tube which telescoped into another tube which extended several feet into the balloon. The latter tube was closed at the top and firmly fastened at the bottom of the balloon to a disk of brass about eight inches in diameter, and a quarter of an inch thick. On the opposite side of the brass collar was another steel tube extending some distance on which a weight could be suspended to balance the other end of the steering apparatus. The brass collar made its circular motion on steel balls.

When the steering apparatus was adjusted, it was interesting to see how readily it answered to the slightest pressure, the monster balloon turning even when a slight breeze was blowing through the building.

But I fear to weary the reader with a detailed description of minutiae. Only a few words more in reference to the basket, if basket it might be called. He had it made to order. It would be difficult to find a finer specimen of wicker work. It was somewhat oval in shape, fourteen feet long, three feet deep, four feet wide at the top, tapering to three feet at the bottom. Around the top was a light bicycle tube, an inch in diameter, but hidden from view by the wicker work around it. A similar, but smaller tube was at the bottom. Connecting the top and bottom tubes were six smaller ones, and two of a similar kind extending longitudinally on the bottom. All were hidden from view by the wicker work. Both the inside and outside were covered with thin, strong rubber cloth. A space of three feet on each end was appropriated to receptacles for food and whatever was to be carefully stowed away. These could be made air and water tight. The little engine had its resting place in the center of the basket, occupying not more than sixteen inches lengthwise.

The basket and the steering apparatus were always in the same direction.

He built a small railroad track extending about fifty yards from the building, on which was a small car on which the basket and balloon could be taken in or out.

It was necessary that I should make a trip to Kansas City, but I was determined to see Gus make a start, if I should be detained the whole summer. He gave me a list of things to purchase for him. I was absent about five days. During my absence, they had the balloon out on the car experimenting with it. It behaved nicely, and seemed to be all that Gus could desire. He was specially delighted with the "fish bladder." With one hand he could, almost instantly, stop its upward motion and cause it to hang suspended in the air when the wind was not blowing.

The gas engine was a success, and the wings seemed to act like those of a veritable bird. He could cause it to alight with the ease and grace of a wild goose settling down on the earth. He made several short flights of a few hundred yards. He and the sail maker made several trips. They could land the balloon on the car without much effort. I could not resist the temptation of taking a short ride. At first I had some emotion of fear, but it soon left me. The balloon did not seem to move as it rose. It seemed to remain motionless, and the earth seemed to be the moving body, moving away from us. It would be difficult to conceive of anything more delightful than a ride in such a balloon.

Gus proposed that we should take a night ride of some distance, to which I readily assented. We had a light aboard. We found no difficulty in navigating the air. We could go any direction at will, except in the face of a stiff breeze. We arose until our little aneroid indicated a height of one thousand feet. I do not know the distance traversed, but we were absent nearly three hours.

We learned from the newspapers that we had been seen. Men were ready to swear that they had seen an air ship. We made several night trips and were sighted in different parts of the state. Once we sailed directly over Kansas City, at an altitude of more than a thousand feet. The papers reported an air ship sighted, and told the direction it traveled.

I MADE up my mind definitely that I would accompany Gus on his trip. I argued that the whole journey, until our return would not occupy more than three weeks.

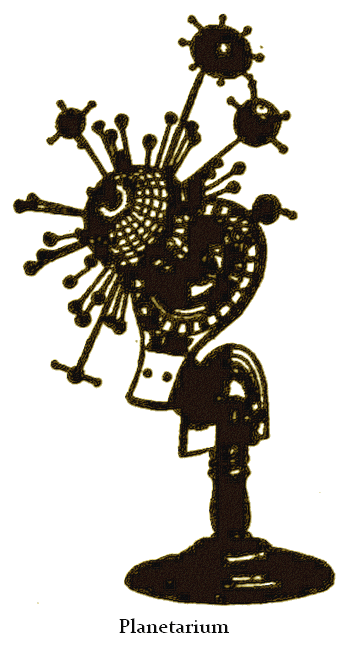

We fixed on the 18th of May for our departure. Everything was prepared. We had a supply of clothing for any emergency. Our food supply was for three months; the water for three weeks, feeling sure that it could be renewed. The cylinder of the windlass was filled with gasoline. Our supply of books was a Bible, a New Testament, both small, and Nautical almanacs for three years. We had two winchesters. Each carried two good watches. We had a mercurial and an alcohol thermometer, and a very fine aneroid barometer on which were marked elevations. We took with us a good binocular field glass. We had a sextant, and a little apparatus called a planetarium. The latter we saw advertised in a Kansas City paper. It claimed to possess divers merits, and gave promise of being useful on our journey. When it came, it seemed to be too complicated for our use, and the first impulse was not to be bothered with it on our journey. But the machine proved to be simple in its working beyond all expectation, and one of the most valuable things we could have taken, not only for our trip, but also after reaching Polioland. Its weight was only a few ounces, very convenient to handle, and it could tell us all we wished to know about the stars above us, and even the latitude in which we might be.

When we reached Polioland, it made plain to us the appearances and apparent motions of the sun, moon, planets and stars. Without its aid many of these things could not have been so thoroughly comprehended. There seemed to be no end to the uses to which we might put it.

It was a little after nine o'clock, p. m. when we began to make an ascent for our journey. The night was all that we could desire. We bade them all goodby, and Gus slackened the cords on the windlass, and we began to ascend with considerable velocity; or rather, the earth seemed thus to move away from us. By the light of a lantern, I watched the aneroid. The extent of our ascent would depend on finding the proper current. On the surface there was a slight breeze from the south, and it continued as we ascended. Gus stopped the ascent when we were about six hundred feet up. The moon, nearing the first quarter, was yet three or four hours high. Close to it was the giant planet, Jupiter, which seemed striving to rival the half moon in sending forth light. Saturn was near the meridian. Venus was not visible. The stars seemed brighter than I had ever seen them. In the extreme northeast, low down, was Capella. Castor and Pollux were preparing to retire below the horizon. Arcturus was almost overhead. The most beautiful among the fixed stars was Vega, in the northeastern sky. It was an easy matter to locate these by the Planetarium.

Gus took the matter of starting in a very matter of fact way. He did not seem to mind it any more than if going aboard a train of cars to take a journey of a few hundred miles. I confess I had some misgivings. Neither of us was in a talking humor. Gus kept his hand near the handle of the windlass. He also took charge of the steering apparatus. We did not have an opportunity to give it a test that night. The tail was to the south, and the current carried us toward the pole star. The gas engine was not started during the night.

About midnight, at the suggestion of Gus, I fixed for a nap. I was not sleepy, and did not think it. possible to get to sleep. But Gus assured me that I was sound asleep in less than ten minutes. It was five when I awakened. I told Gus to take a nap, but he said he had no disposition to sleep. But he made trial, and was as successful as I had been. He slept about four hours. Day was beginning to dawn before I awoke, and Gus had ascended to an elevation of 1200 feet. When Gus awoke, the sun was high up, and the earth looked beautiful. We could see forests, lakes, rivers, towns and even farm houses. When Gus awaked, he took the field glass, and said he could see a woman milking a cow. He saw another feeding young chickens. At our elevation, there was a considerable lowering of the temperature. The mercury fell to fifty degrees. Our motive in seeking a higher altitude, was that we should not be disturbed by things terrestrial. I know not whether we were sighted by any one.

We got out our lunch, at noon, and when I had finished, Gus had scarcely made a beginning. His eyes seemed to be more hungry than his stomach. He stood up, both hands holding his lunch. A large pocket knife, open, was between the fingers of his left hand, and his mouth partly opened, and his eyes greedily feeding on the landscape beneath. He presented a very interesting picture. I spoke to him and asked him why he did not eat? He seemed like one waking from a sleep. "This view," said he, "is worth all our expense and trouble." I stood up, and took turn about sight-seeing with the field glass. In the southeast we saw a large city and concluded that it was Omaha. Any effort to describe the grandeur of the scenery, the magnificence of the views, would be impossible to any one, and most certainly to me.

On this day we had occasion to try the steering apparatus, but it would not perform. When he would turn it to change our course, instead of doing this, the balloon and all would turn, and leave the steering sail just as it had been in reference to the wind. For a time, this bewildered and annoyed Gus. After thinking the matter over, I laughed and told him we ought to have known that it would thus act. I suggested to him to start the engine, and then he could steer. He did so, and we were astonished and delighted at its action. When the wings were flopping, he had no trouble in guiding in almost any direction save directly in the face of the wind. Even then, with a moderately strong wind, we could make some progress, but slow. Gus slackened the cords, and we rapidly ascended until the aneroid indicated an elevation of more than 4000 feet. There was not as much fall in the temperature as we had anticipated. There we found a current that carried us directly northward. This pleased Gus, and he said, if necessary, he would ascend ten thousand feet.

At noon I took the zenith distance of the sun with the sextant and found it to be 25 degrees, which gave us a distance of 5 degrees from home, or nearly 350 miles.

For practical use we found the Planetarium far more convenient than the sextant. With the latter, we had to take the altitude of the sun at noon, that we might know its distance from the equator. But with the Planetarium, we could find our latitude, approximately, at any time of the day. It consists of a small globe, about three inches in diameter, having a piece of felt inserted for the ecliptic. A pin, about six inches long, on the end of which was a ball half an inch in diameter, represented the sun. A table accompanies it giving the right ascension of the sun throughout the year. The hours of right ascension are marked on the globe. You insert the pin in the felt ecliptic at the place of the sun's right ascension. On the lower part of the globe is a hand which points to the date of the month and day. Below that is another hand pointing to the hour of the day. When the hand was pointing to the correct hour of the day, and the Planetarium was held level and pointing toward the north, then loosen the nut for latitude, and move the globe in latitude until the shadow of the ball representing the sun falls directly around the base of the pin, then the hand for latitude points to the latitude of the place where you are.

Our dipping needle indicated some progress toward the north pole. We had fine weather, and a fine breeze all Tuesday afternoon and night. On Wednesday at noon our latitude was 53, a gain of eight degrees in 24 hours, or about 550 miles.

On Thursday at noon, latitude 63. During the whole of this afternoon we have been over a large body of water, which we suppose is Hudson's bay. The dipping needle indicates that we are rapidly approaching the magnetic pole. I was anxious to note our position when we reached it. The night was not favorable for observations, because of clouds which, though not dense, yet interfered with taking observations. In the south, I got a glimpse of Saturn, about 11 o'clock. It was about 8 degrees above the horizon. This would locate us about latitude 68. Just as the sun was rising, about 2 o'clock, the dipping needle was 90 degrees, showing that we were at the magnetic pole. The pole star was about 20 degrees from our zenith. Before sun rise, I saw Capella, and it was evident that it would not get below the horizon, at its northern point. Just as the sun was rising, we got a sight of Venus. She was several degrees south of the sun.

Before us, and around us was a scene not so inviting as it had been. There was a strange commingling of land and water. After passing the magnetic pole, we descended until within a few hundred feet of the surface. There was a good breeze, at that elevation, toward the north. At 10 o'clock the mercury indicated 60 degrees. Some distance ahead, Gus sighted an island appearing to be about ten miles in diameter. It was almost barren, but abounded with birds of some kind. He determined to make a stop, but I protested, fearing that some injury might result to our basket. But he insisted on stopping. When we reached the shore, we were not more than fifty feet from the ground. Gus selected a suitable place, and quietly dropped down until the basket was not more than a foot from the earth. He told me to jump out. I obeyed, and up went the balloon. But soon it descended a short distance from the place I was standing. I then held it until he got out, still holding the crank of the windlass. He tightened this until the balloon floated near the ground when he was out. It might have been safe to leave it in that condition, but we made it fast with cords. On our approach, the birds had flown. But in a short time many of them alighted at a little distance. They were wild geese, and several varieties of ducks. We had no difficulty in getting all we desired. It would have been no difficult matter to have gathered eggs by the wagon load. We had a regular picnic. Gus showed his adeptness in the culinary art. We remained on the island two hours. Before starting, I found that our latitude was about 73:30. There was scarcely a sign of a breeze near the surface, and Gus started up his engine. It performed admirably. We flew along at an altitude of about two hundred feet.

On some of the land over which we passed, there was a considerable amount of vegetation, as we thought some species of pine. In the waters, were great icebergs many of which were manifestly loose and floating. We slept by turns. Neither of us felt any special need of sleep, but found no difficulty in getting to sleep when we made the effort.

No night awaited us on that Friday. The sun, instead of sinking below the horizon, made a complete circle. At midnight it had a respectable altitude. At that hour we both were awake. Neither of us had ever seen a midnight sun. Neither seemed inclined to talk. Gus was peculiarly thoughtful. I watched him as he took his hand from his face. He had been brushing away a tear. I wondered what was the occasion of such emotion. In a few minutes he took out his new testament, and began to read. Fresh tears started. I said nothing. After reading some time in silence, deeply affected, he began to read aloud. It was at the 22nd verse of the 21st chapter of the book of Revelation. When he had read the 25th verse, which he did with great emphasis, he stopped a few moments and looked at the midnight sun. He preached me a little sermon on the relation between daylight and morality, and between darkness and sin. Then, doubling his fist, and bringing it down with force on his knee, he said, "Show me a place where there is perpetual light, and I will show you a place where there is no sin." After a short silence, he continued reading aloud.

When he read the 27th verse, he said, "There it is. If sin should try to enter, it would wait at the outskirts until darkness came, and finding that darkness would not come at all, it would skulk away to its own home of perpetual darkness."

Gus tried to draw a picture of the sun's path in the sky as it now appeared. He said the best way to describe it would be by a wagon wheel resting on the floor, but one side tilted so that it would be on

the floor and the opposite side up in the air.

We now found it difficult to keep track of the points of the compass, by observing the sun. To know which was north or south, we had to note carefully when it was at the highest or lowest point of its course. About nine p. m. we became bewildered. Gus said, "Get out your little machine. It may be that it will tell you." I replied, "No, it will do many things, but I suppose that is one of the things for which it is not adapted."

However, I took it out, and adjusted it to the time of day, and holding it level, I turned it around until the shadow of the sun was in the proper place around the pin where it was inserted in the felt ecliptic, at the same time adjusting the axis for latitude, and then I said "Yes, here it is." We were going considerably to the east of north. He then ascended until he found a current that would take us northward. Gus was loud in his praises of the "little machine."

The scenery around us was by no means inviting. The water, for the most part was in a solidified condition. Where there was land it was difficult to see it on account of hills and mountains of ice. From this view it was easy to understand why all efforts to reach the pole by land or water had proven failures. There may be seasons at long intervals, and points in some directions by means of which that end might be attained. Such a condition may occur once in a century, but could not be anticipated. To be successful under such circumstances, the opportunity must be improved when it comes.

At noon on Saturday, we estimated our distance from the pole at about 500 miles. The prospect was by no means inviting. We began making preparations for our return. Our hope was to reach home in the early days of June.

After we had discussed the matter of our return, assuming that our homeward journey would begin within a few days at the most, and possibly within a few hours, Gus raised the question, "Has it paid?" Whatever might be the outcome, I assured him that I was richly repaid for my trouble and time. Gus said, "It has cost me a great deal of time, labor and money; but it is the best investment of my life." But he said he felt no uneasiness on the money question, as he knew he could dispose of his "air ship" at a good profit on his return.

On Saturday night at midnight, the sun was perceptibly higher than on the preceding midnight.

On Sunday forenoon, Gus, holding the glass, said, "Water ahead." I took the glass, and there was no mistaking it.

There was a large body of water, and apparently free of ice, at least in large quantities.

About noon Gus cried, "Land ahead." It seems to fall to his lot to make all such discoveries. He handed the glass to me. I held it for a long time. I could distinctly see vegetation, and felt sure that I could see something resembling human habitations. After a good look, Gus said I was correct. There was the land, and it was inhabited.

We ascended several thousand feet, but found the current away from the pole. From that elevation we could see that the land was an island of considerable size, and had many towns or villages. We descended to within a few hundred feet of the ground. Here there was but a slight breeze.

At four o'clock, 90th meridian time, on Sunday afternoon, we were hovering over the largest city, apparently, on the island. This, we concluded, was very near the pole. We were now within less than a hundred feet of the ground.

Near the city was a large open space, and on this we determined to settle down. The gas engine had been in operation for some time. We knew not what fate awaited us. We had been seen by thousands of people, but none came to welcome us. Instead, they scampered off and gave us as wide a berth as possible. I held the glass, and Gus managed the balloon. I could see the people very distinctly, and saw they were greatly excited. I could see some of the men smoking, it seemed, cigars. In vain we waited hoping that some one would come to us. I suggested that we should deposit something on the ground, then ascend and see what they would do. But we were limited in our supplies for such a purpose. I wrapped a little salt in a piece of paper, tying it with a piece of red twine. I had a copy of a Kansas City paper about a week old. This might attract their attention. A few minutes before, Gus had filled and lighted his pipe. It was briar root, with trimmings that shone like silver, and was a handsome pipe and had not been in use but a few days. He had others, and consented that I might deposit it with the other articles. They were all placed on the ground in the sight of those who were watching us at a distance. We then ascended, and I watched to see the result. A crowd of boys made a rush for the place where the things had been deposited, followed by men at a more leisurely gait. A boy twelve or fourteen, secured the pipe. He hastily examined it, then ran to meet the men that were approaching. He gave the pipe to one of the men, who proved to be the boy's father. The latter examined it, then put the stem in his mouth, and it was still lighted, and he puffed away with manifest delight. This same man got hold of the newspaper, and holding it up, flourished it about toward us, making signs for us to descend. I told Gus what I had seen, and that we were all right. As we approached the ground, there was another scampering, but several remained. The man with the pipe was the first to greet us. As we afterwards learned, he held an office in the state.

THE man who greeted us was a fine specimen, and looked as if he might claim kin with Gus. He had light hair, blue eyes, and appeared to be about fifty years old. In a short time the crowd around us had increased to thousands. It is amazing to what an extent communication can be carried on between persons who know nothing of each other's language. It can be done by signs and gestures. By this method we were directed to get out of the balloon, make it fast, and go into the city. We were made to understand that no harm would come to our balloon. We did as directed. A guard was left with the balloon with assurance that nothing should be touched. We were then directed to accompany the man who had the pipe. As we were marching along, I told Gus that the man resembled him, and that we must call him Gustavus. As soon as I had pronounced that name, he turned around, pointed to himself, and said, nodding, "Yustavo, Yustavo." From this it appeared that that was his name. On the way to the town, we heard some one calling him "Yus" I said to Gus, "Who are these people, and whence came they?"

On being taken into the city, we were led to a stone building, having the general appearance of a prison. It had massive doors, and securely locked. A man soon appeared, with keys, and unlocked the outside door. As we entered, I asked Gus if it was a prison. He said nothing, simply shaking his head as if to mean, "I don't know."

We followed the motion of Yus, and ascended a flight of stairs. A man accompanied us with keys, who stopped before a heavy cumbrous door, to unlock it. A prison, sure, I thought. Yet the surroundings did not present the appearance of a jail. Besides, every one seemed to be delighted with our coming to their land. I do not think that my mind was ever more mystified, and that I thought of so many things in so short a time. So great was my mental agitation, that the perspiration dripped from my face. Gus seemed to take it coolly, as if nothing unusual was happening. When we got inside the room, and ascertained the object of our being taken there, I felt so exhausted that I wished some place to sit down. What I beheld on a table in the room created such a sudden revulsion in my emotions and feelings, that it had the effect of a tonic or stimulant. I forgot all about prisons and my former fears. Gould I believe my eyes? Was I waking or sleeping? Where was I, and what were these things on the table before me?

There, on the table, were divers kinds of astronomical apparatus. There was a fine Bitz telescope, three and a half inch objective, with one terrestrial, and three celestial eye pieces. There was a fine sextant, with a small telescope. Besides these, there were drawing instruments,

and several articles that a scientific explorer would find use for in his work. There were some books, including an English Nautical Almanac for 1846. Also several papers of 1845.

By sign language, Yus made us understand that these things were taken from the wreck of a boat, when he was a babe. As near as we could ascertain, this occurred in 1850 or 51. Yus took twelve little sticks, and by sign language made us understand that they represented men on the wreck. Nine of them he laid down, to show that they were dead when found. Three he stood upright, but indicated that, though alive, they were in a very enfeebled condition, and did not long survive.

Yus had taken us to this room to show us these things, in the hope that we could explain their use. I told Gus that we must, at once, show them the use of the telescope, as it was certain that they would be greatly interested in it, and by such means we should be able the more perfectly to ingratiate ourselves into their favor. By signs, Yus asked me the use of the telescope. I motioned to him to have it and the tripod taken down stairs. I followed with the terrestrial eye piece. I looked around for as distant a view as possible. I found something some three or four miles away. I adjusted the focus on the object, made the telescope fast, then showed Yus how to look through the small aperture. He was familiar with the scene on which it was focused. The terrestrial eye piece had a power of forty or fifty diameters. The object on which it was focused did not appear to be more than a few hundred feet distant. It showed up very distinctly. Yus looked through the glass, then looked outside, then through the glass, and outside again, then he looked at me, then to the telescope, and again at me, with an indescribable and curious expression, as if to say, "What sort of trickery is this you are working off on me?" He meditated, and again looked. Suddenly it seemed to flash on his mind that this was a wonderful instrument. There was a great crowd standing around. He began to address them. He did a vast amount of gesticulation, and they seemed to become very much excited. From the rush to him, it appeared that he had extended a general invitation to them to look for themselves. But he motioned most of them away, and called for a few of the more prominent looking of the crowd. We were kept there two hours, while scores or hundreds had an opportunity of taking a brief look.

Greatly to our relief, Yus directed that the telescope should be returned to its place. It was now about 7 o'clock, p. m., and we were tired and hungry. We made signs that we wished to return to the balloon. He made us understand that it was all safe, and that we must go with him. He led us some distance and stopped in front of a stone house with heavy walls which seemed to be characteristic of all the better class of houses in the city. The windows, to us, seemed very small. The house had two stories, and several rooms. The ceilings were quite low. Yus took us through several of the rooms to show us how they lived in Polioland. He took us to the kitchen. From nose and eyes we found that they were then engaged in cooking. The odor indicated something good for the palate. To our great astonishment, we found that the fuel used for cooking was some form of gas. This attracted our attention, and Yus noticed our curiosity. He then showed us the pipes through which the gas came, and indicated that the gas came from the earth. This delighted Gus beyond measure. He had wondered how he should be able to refill his balloon, in case he should empty it. Now that question was solved, and he said we must empty the balloon as soon as possible.

In a short time we were ushered into the dining room. There we found things so little dissimilar to what we had been accustomed to, that we felt no special surprise. The chairs had no backs. They were simply stools. The dishes were a species of white porcelain, and odd looking, but really beautiful. I suspected that these were not the ones in common use, judging from the way the boy examined them. The knives were steel blades, and had beautiful ivory handles. We afterwards found that ivory in Polioland was very abundant. They had no forks, at all like those to which we had been accustomed. It was something half way between a fork and a spoon. The handle was as long as that of a fork, but at the other end was something in the shape of a spoon that was almost flat. It had a slight concavity, and after a little use of it, I concluded that it was an excellent substitute for our fork. The bread offered us was leavened, rather dark, but palatable. The meat I took for beef, but found it was a species of venison. It was tender, well cooked, and delightful to the taste. At the table were Yus, his wife and four children—three girls and one boy. The oldest girl seemed to be past twenty. The next a girl about seventeen. Then the boy, about fifteen. The youngest a girl, about twelve. All had light colored hair, and blue eyes. I have no recollection of ever partaking of a meal that I relished and enjoyed more than that first meal in the home of our new Polio- land friend, Yus.

After supper, Yus took out his new pipe, and manifested his great appreciation of it. The bright metallic mounting greatly pleased his fancy. He and Gus took a smoke.

I took out my watch to see the time. Yus motioned to me to let him see it. He held it to his ear, and understood its use. He showed us a clock. It had no striking attachment. The wheels were made of wood. On the dial were 24 divisions instead of 12.

For the first time since we left on our trip I felt drowsy and inclined to sleep. I yawned. Gus caught the contagion. Yus noticed it, and imitating our yawning, smiling and nodding, he made a motion at reclining, as if to ask if we wished to go to bed. We nodded assent. He then led the way to a room in the second story. In the house and furniture there seemed to have been an unnecessary waste of material, as everything was so cumbersome. The room into which we were led, had two windows, rather diminutive. For these, curtains were provided that the room might be made as dark as desirable for a daylight sleep. As the rays of the sun poured through one of these windows, he said we had a room on the south side. I reminded him that the house had no other side except the one to the south. No north, no east, no west, for a house in Poliopolis. In any direction you might look, it was south. When we retired, it was 9 p.m. Sunday night. We drew down the heavy curtains, and all was darkness. We were in a state of blissful ignorance of all things terrestrial until awakened by a loud knocking. It was by Yus. He had raised the curtain, and by the amount of sunlight, we concluded it must be high time to get up. We had slept nine hours.

Judging from the preparations that we found for our morning ablution, we concluded that we were with a people with whom cleanliness was in high repute. There was a large, curiously wrought pitcher filled with water, and a large, neat porcelain washbowl. On a shelf near the table on which these were placed, was a pile of towels numbering two dozen.

When we entered the hall to go down stairs, we found the youngest girl there waiting for us. In a mechanical sort of way I said "good morning." I suppose she understood what I said, by instinct. She nodded assent. I held out my hand to her. She took hold of it, and thus we proceeded down stairs and into the dining room. The other members of the household seemed amused at our manner of entering the room. Her mother spoke to her, and I heard the word "Mauree." This, I concluded was the name of the little girl. Such was the case. It was the same as our familiar name "Mary," with a strong accent on the last syllable. That little girl proved to be a great treasure to me. I became her teacher, and she became mine. She tried to teach me the language of her people, and I taught her English. I suspect that I was the better teacher, as my pupil advanced far more rapidly than did hers. She had an excellent mind and a good memory.

It would be difficult to find a pupil more anxious and apt to learn. She would point to every article of apparel, to every piece of furniture, and to everything she got sight of, to have me give its name in English. When I would give her the name, she would repeat it over and over. She seemed never to forget a word once fixed in her mind. I may exaggerate, but I think that in one hundred minutes after breakfast, she had a vocabulary of one hundred words. Before dinner, Gus and I took a walk. When we returned, I was astonished to hear Marie say distinctly, "Good morning." For a moment I could not recollect having given her these words, but Gus reminded me that I spoke them to her as we came into the hall after getting up.

I shall now make a statement that is in no measure exaggerated, but which may seem incredible to the reader. It is this. Before sundown Marie and I could converse in English with great ease. Also, I taught her to read English. Our text book was the New Testament.

Her rapid progress in learning English, proved a great hindrance to our learning their language. She soon became our interpreter, and for a long time, conversation with others was carried on through her.

Gus found a turning lathe, and at my request made a wooden globe about five inches in diameter. On this, I marked the meridian lines, and parallels, and the divisions of the earth, and thus taught Marie geography. I taught her about the different nations inhabiting the different parts of the earth. I told her of the many efforts that had been made to reach Polioland, but had all failed. She was very much interested in my description of day and night in every part of the earth except at the poles. It was here that I found the Planetarium of great service. I could, by it, enable her to see the exact motion of the sun at any season of the year, and on any portion of the earth. By watching the long pin on which was the ball representing the sun, and also watching the hand that points to the hour of the day, she could tell just when the sun would set, or go out of sight, at any place. Also, when it would rise again.

Soon after our arrival, we made a device to enable us to point to any given meridian on the earth. Now we could explain it to Marie, and she was greatly interested in it. We got a flat, smooth stone, about two feet square. This we raised about two feet, making it level and fast. On each side we drove two small stakes, and fastened a piece across the top. From the center of this cross piece, we fastened a string, and tied a weight to the lower end, so that we had a plumb line. Our watches gave the time of the 90th meridian, very nearly that of St. Louis. On the shadow cast by the string at noon by our watches, we made a mark, and marked it 24, or the place of beginning. Thus we marked all the hours.

It required no little care on our part to keep track with the days, because our watches marked but 12 hours on the dial. It was necessary to note whether the time was a.m. or p.m.

OUR little Marie led us into a digression, and carried us nearly to the end of our first polar day. But it is difficult to know what method to pursue in giving an account of our experiences and observations. The upstairs room in the home of Yus was our abiding place during the whole period of our sojourn in Poliopolis. At one time, because of a misunderstanding, it seemed probable that I, at least, would be compelled to seek other quarters. But after explanations and a proper understanding of facts, the difficulties were amicably adjusted.

While there were other houses more costly and capacious than the home of Yus, yet we could not have found one more to our liking and comfort. He made us feel that our companionship was abundant compensation for any expense and trouble incurred for us.

Shortly after our arrival, we emptied the balloon, and Yus provided a safe repository for it. During our long sojourn, we filled it occasionally and made a few short excursions, Gus taking a few by turns for an aerial ride.

The inhabitants impressed us as being, for the most part, remarkable for their industry, sobriety, and freedom from those vices that degenerate and degrade humanity. They had made commendable progress in civilization, and were skilled in many of the arts. They were familiar with many of the metals. They had gold, silver, platinum, iron, copper, zinc and lead. There were vast deposits of coal of a very fine quality. It is doubtful if such deposits can be found in any other portion of the earth. This would indicate that in the earlier periods of the earth's history, vegetation abounded here as in no other part of the world. Ivory abounded in quantities sufficient to supply the needs of the whole world for a long period. It would be difficult to estimate the quantity that could be obtained. They utilized it for every conceivable purpose. A species of clay is found, useful for brick, from which they obtain large quantities of aluminum.

The island, or continent, in shape, is circular, extending about two degrees from the pole. It has an area of about 125,000 square miles. The population, we estimated at about one million, or probably a little more. For the most part, the people live in towns or villages. This is true of those whose chief work is agriculture. They so arrange it that their dwellings shall be as near together as possible. This results from their social peculiarities. During the long period of the absence of the sun, they have much leisure, and spend a great deal of it in a frolicsome, social way. An effort is made to have regular times for sleeping, but such rules are observed, for the most part, only by the younger portion of the family. The older ones eat and sleep when it suits them.

The soil is rich and productive, and the work of the agriculturist is not laborious. The country is well watered. There are four streams that might be called rivers. These, after meandering in different directions, unite and form one river which empties into the Arctic Ocean. They obtain their supply of gold on some of these streams. It is all obtained by what is known as placer mining, or washing the sand and separating the small grains of gold. They have frequent rains during the period of sunshine, but more frequent during the sun's absence. In the outer portions of the continent, snow abounds at certain seasons.

Fruit trees of several varieties are found. They have apples, cherries, plums, and some other varieties. Grapes also abound. In the matter of cereals they are well supplied. They have a species of maize, the stalks of which do not reach a height of more than five feet. The ears are small, and the grains are compact and hard. When ground, it makes an excellent, nutritious food. They have a species of wheat the grain of which resembles ours, but the stalk is more like that of barley. The forest trees are, for the most part, different species of evergreens. Some of them become very large. The growth of vegetation, during the period of sunlight is amazing. From planting to maturing maize does not require more than six weeks. The same rapid growth characterizes all kinds of vegetation. During our sojourn we saw forest trees that measured more than one hundred feet in circumference. I measured the height of one of these, and found it to be 367 feet.

Among the animals are several varieties of deer. Some of these have been domesticated, and are made useful in divers ways. They have several varieties of animals belonging to the class of sheep or goats. On some of these the wool is very long, and almost straight. Their dogs, about the head, resemble the wolf, but the body is larger and more compact than that of the wolf. They are intelligent and affectionate in their disposition, and are useful. Neither cats, rats nor mice are found there.

Birds of many varieties abound, but they are not remarkable for beauty of plumage. Some remain there the whole year, but most of them come after the sun rises, and depart when it goes down. The water fowl are most abundant and afford an inexhaustible supply of food, eggs and feathers. They do not wantonly or needlessly destroy the birds. They take only what can be profitably used.

The migratory birds seldom appear until the sun has risen, nor do they tarry long after its disappearance. There are several varieties of wild beasts, having a very fine quality of fur. Occasionally a polar bear is seen on the outer portions of the continent. His appearance affords great pleasure to the young men. A company is soon formed and the sport begins. The skin of a polar bear is highly esteemed. The hair is white, long and very thick. A bear skin is sufficient to cover a room of small size. A bear of good size will weigh 1,500 pounds.

Fish abound in the waters. More than a month before sunrise, the salmon begin to ascend the streams. It would be difficult to exaggerate their numbers. Often, so abundant are they, that a spear thrown at random into the water will strike a fish. Water fowl grow fat from the abundance of such food. At all seasons, in daylight, and when the sun has set, excellent fish, of several varieties may be secured without effort. So abundant are they that fishing ceases to be a sport.

One of the greatest blessings to the Arctic continent is the abundant supply of natural gas. It has been utilized for about half a century. They are lavish in its use when needed, but are not wasteful of it. The cost for household purposes is nominal. On certain occasions, in different parts of the country, for several hours together, the consumption of gas seems prodigious. It was during some national festival, or public occasion that this would occur. Even then, the flow of gas and the duration of it, was governed by those in authority. In some cases, the pressure was sufficient to throw the gas more than a hundred feet into the air. The pipes were about four inches in diameter. At any time the scene was magnificent, but especially when clouds were above. For miles around, the space would be brilliantly lighted, and the light visible at great distances. The flow would continue for a few hours.

THE present inhabitants of Polioland are, for the most part, descendants of a large number of refugees who fled to this region some three or four hundred years ago. Some fled from religious persecutions, and some from political. There is a tradition that at that time there was a connection between the northern part of Europe or Asia, and the Arctic continent. Some claim that it was land connection. But it is more probable that it was by means of the waters being frozen over, and giving them a safe and easy passage. There is a well founded tradition that such was the condition of things at an early period in the 19th century. From the statements of some of the oldest citizens, it was during or near the year 1816. The tradition is that the intense cold began during the absence of the sun, and was so great that all the waters around the continent were frozen to a thickness of two or three feet. During the whole succeeding period of sunshine, the cold continued so that scarce no crops were raised except in a small region immediately around Poliopolis. There was much suffering for the want of a sufficient supply of food. Thus, for a period of about eighteen months, it was an easy matter to pass from Polioland to the continent of Europe or Asia. During that period there were many accessions to the inhabitants from the old continents. Also, great numbers of the aborigines left the country. These latter were Lapps or Esquimo, who never did assimilate with the emigrants, and who had no liking for the ways of civilization. Those left on the continent had their dwelling places near the ocean, and as far as possible from Poliopolis. The ancestors of Yus, so he claimed, were among those who migrated in the first part of the century. The people are thoroughly civilized, and are interested in education, although not very much progress has been made save in the elementary principles. In the arts they have made commendable progress, being able to reduce and cast the metals, and were skillful in the use of tools. I imagine they were not very far behind our ancestors of a hundred years ago.

The religion of the Polianders is a mixture. A certain class have religious peculiarities that would seem to ally them with the papists. But in some things they differ from them, notably in the matter of baptism. They not only immerse, but do it repeatedly. The religion of the larger and more intelligent portion of the people is manifestly of Protestant origin. The individual churches seem in a measure to be independent, yet they have state assemblies to which delegates are sent. They keep one- seventh of the time as a Sabbath, but that which corresponds with our Tuesday. It is not surprising that they should become confused in attempting to keep trace of anything like our 24 hour day, or the days of the week, seeing that one day with them is six months of continued sunshine.

The climate of Polioland, and especially of Poliopolis, is without a parallel in the known world. There is a region, immediately around the pole, from ten to twenty miles across, where the mercury never reaches zero. The cold increases as you recede from the pole. On the coast, about 150 miles from the pole, the mercury, during the absence of the sun, gets far below zero. Also snow is abundant there, but rarely seen in Poliopolis.

The barometer indicates a far denser atmosphere at the pole than we are accustomed to. The aneroid which, at Kansas City, would vary from 28 to 30, at the pole will show as high as 34 inches.

The relatively high temperature, and the electrical phenomena at the pole are difficult to account for. Possibly the axis of the ocean of atmosphere may have something to do with them. At the equator, the surface of the earth, by reason of the earth's rotation, moves at the rate of nearly a thousand miles per hour. As the air is so mobile, we might suppose that it would be left behind, and that the earth would go much faster. If this were so, a bird that should hover in the air for a few moments, would find itself at a considerable distance from the point where it left the earth. The whole ocean of air rotates with the earth. While it is an intensely mobile fluid, yet it keeps up with the earth as if it were a solid, and firmly attached to the earth. Not only so, but in some measure it seems to defy the law of centrifugal motion, by which it should be piled up in a great protuberance at the region of the equator. In defiance of that law it rises at the equator, then pursues its journey northward until it reaches a half way station, then descends to the surface and moves on toward the pole. It is at the pole that it seems to accumulate the greatest mass. Having approached the pole from every direction, it finds a stopping place, and an axis of its own around which it must rotate. Here it has a twofold motion: rotary and upward. The currents from every direction seem so nearly to balance each other, that there is no perceptible disturbance. But there must be a vast amount of friction. Whatever may be the philosophy of the conditions, yet it is probable that this rotary motion of the atmosphere around its axis, has something to do with the strange meteorological peculiarities of the region around Poliopolis, both in respect to temperature and electrical displays.

THE government of Polioland is somewhat peculiar. There are, nominally, the usual three departments. What might be called the lower house of the legislature, is composed of members elected by the taxpayers of the state. With the upper house, it is different. For this the sole qualification is the possession of a specified amount of wealth. This is determined by the amount of taxes paid. It is argued that those who pay most of the revenue should have a voice in the manner of its expenditure.

From the members of the upper house one is chosen to be at the head of affairs, or practically the President of the state. Here, also, wealth is the qualification. The office belonged to the member of the upper house who paid the largest amount of taxes. He held the position so long as he possessed the qualification. While the ratio of the two houses was variable, yet usually it was three or four to one, in favor of the lower house.