RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

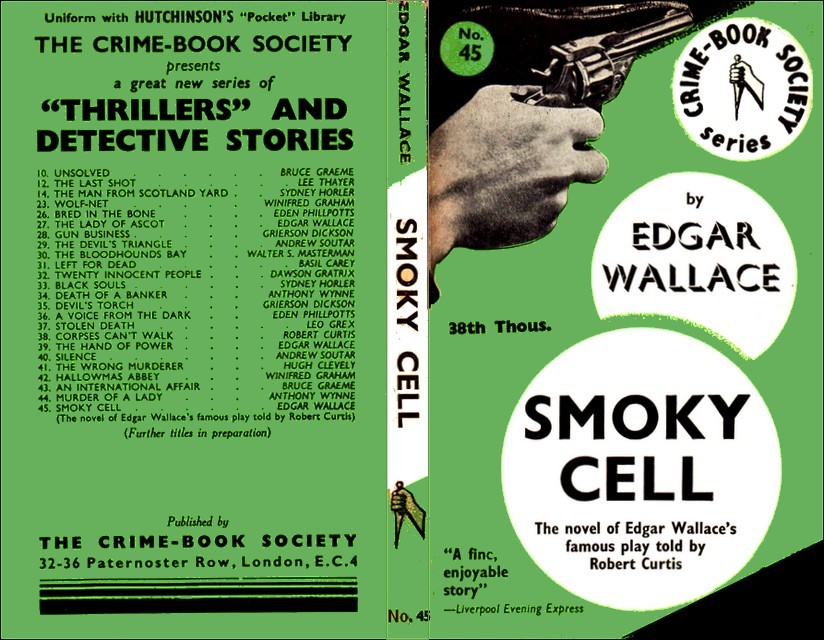

Smoky Cell, The Crime Book Society edition, London, no date.

JOSEPHINE BRADY placed the telephone receiver against an undeniably well-shaped ear and said: "Hallo!" with a pair of lips in close proximity to which only a telephone mouthpiece could have remained unmoved.

"Is that you, Miss Brady?"

The voice was rich and deep, like a well-oiled purr; and, as she heard it, a little pucker appeared between Josephine's eyebrows.

"Miss Brady speaking."

"Good evening. It's Mr. Schnitzer this end."

The pucker definitely deepened.

"Oh yes, Mr. Schnitzer?"

"I'm sorry to disturb you, Miss Brady," continued Schnitzer. "I guess a stenographer hears enough of her employer's voice during office hours and won't be smiling with pleasure to hear it now, eh?"

She did not know what to say to that, so she murmured:

"That's quite O.K., Mr. Schnitzer," as pleasantly as she could.

"The fact is, Miss Brady, I'm in a bit of a fix," he went on, "and I'm counting on you to get me out of it. There's some correspondence I couldn't handle at the office, and it's urgent to dispatch it by tonight's mail. I'd be grateful if you'd come along here."

"Where are you, Mr. Schnitzer?"

"I'm speaking from home."

"Oh!"

"You know my apartment on Lincoln Avenue, don't you?"

"Oh yes—of course—I know it, but I don't think—"

"Now listen," he interrupted. "I'm aware I'm suggesting something unusual, but this is big business, and I'm asking you to forget for the moment what the office hours are and to come along here and take down a couple of letters for me. You can't say I'm exacting as a general rule, but in a matter of urgency like this I expect my stenographer to show willing—"

Josephine recognized the crack of the whip and hastily interrupted.

"Of course, Mr. Schnitzer," she said. "I'll be pleased to come along. If it will be soon enough in an hour's time."

"Fine!" replied Schnitzer. "I'll send the car for you." Before Josephine could protest that she did not want the car, he had rung off, and as she replaced the receiver the deep pucker in her forehead was joined by several others. She was wondering.

She had been stenographer to John P. Schnitzer for three months, and during that time had gathered a certain amount of information about him beyond what was comprised in the single word "Financier" that stood beneath his name on the office door. Within five minutes of her starting work in the office, the snub-nosed girl with the colourless hair who sat at the adjoining desk had given her the first hint.

"Say, kid," she had said, "you're too darned pretty for this outfit," and, thereafter, further information gradually accrued. She remembered, when taxed with the question, that, when she had applied for the post, Mr. Schnitzer had made only the most perfunctory inquiries as to her qualifications as a stenographer—which was, perhaps, just as well—and that fact lent colour to the rumour that the qualities which John P. Schnitzer sought in a stenographer were not so much speed and accuracy as good looks and complaisance. But she had been in other offices—more than she cared to remember—and had learned from experience that in this respect Schnitzer did not stand alone. She had discovered that, provided a girl was a "sport", she could spell "reference" with two "f's" and quote cents instead of dollars and still get away with it, and Schnitzer's reputed possession of this common commercial characteristic did not unduly worry her. She was confident that she was capable of dealing with any situation that might arise in the office.

The snub-nosed girl left her in no doubt as to the situations with which she would almost certainly be called upon to deal. In due course, she prophesied, Josephine would be invited to go out to dinner with Schnitzer—which was all right, she said, as long as she took with her a boy friend with an outsize in biceps; but as a general rule the Schnitzers of modern life wouldn't stand for boy friends, and she would probably have to choose between going without her boy friends or going without her job. Of the two alternatives the snub-nosed girl was of the opinion that the latter would be preferable.

There was a likelihood, too, Josephine learned, of her being asked to go along one evening to Schnitzer's apartment and take down some letters which could not be handled at the office. She couldn't take a boy friend on that trip, of course, but she could take a portable typewriter, with which, correctly used, it might be possible to make a still nastier mess of even Schnitzer's face. But she didn't recommend the visit, even with a portable typewriter. Schnitzer, she said, had a swell apartment on Lincoln Avenue, but flowers died if you took them within a mile of it, and if Josephine valued her lily-white freshness she would keep outside the danger-zone. If a girl, she said, were seen with one foot on the bottom step of Schnitzer's apartment her reputation would look so bedraggled that no one would believe it hadn't been left out all night in the rain.

Josephine had been grateful for the warning and for the first few weeks had kept a wary eye on Schnitzer; but as time passed, and he showed no sign of lapsing from strictly business relations with her, she began to think that he was, perhaps, a much-maligned man. The snub-nosed girl, perhaps, had asked for an increase in salary and been refused.

And now, just when she was feeling secure, this telephone call! She suddenly remembered all the scraps of information she had gathered about Schnitzer, and when she had pieced them all together the picture they formed was not an attractive one. It was certainly not the likeness of a man whose apartment she would care to visit, even when armed with her portable typewriter. It looked as if Mr. Schnitzer were working to schedule, and that things would pan out much on the lines which her companion in the office had foretold. She said to herself very resolutely that she would not go.

But telling herself made no difference, because she knew very well that in an hour's time she would certainly be in Mr. Schnitzer's Lincoln Avenue apartment. Going without her job might be the lesser of two evils, but she just could not afford to allow herself any choice in the matter. She had vivid recollections of intervals that had occurred in the past between losing one post and finding another, and had no ambition again to plod along the pavements of the city in the company of hundreds of others in similar plight. She certainly had no real intention of losing her job without a struggle, for no better reason than that rumour held John P. Schnitzer to be not quite the gentleman he might be. He had never given her cause for the least complaint against him, and it would be foolish to throw away a good job on mere hearsay. Besides, she wasn't afraid of Schnitzer.

Nevertheless, while the big limousine bore her smoothly towards Lincoln Avenue, she was feeling far less at ease than she appeared as she lolled back against the cushions. There was something not altogether pleasant in being in Mr. Schnitzer's luxurious car. She thought of the flowers that died if they were taken within a mile of the house, and wondered if it were possible for Schnitzer's car to have become impregnated with the same unhealthy atmosphere; if, supposing he were all that rumour maintained, he might somehow have impressed his personality on his automobile.

Quite definitely she did not like the car, and its smooth, deep purr reminded her of Schnitzer's voice. And she did not like the diminutive Japanese chauffeur perched at the wheel, who kept glancing back at her over his shoulder and showing his white teeth in a knowing grin. She wondered why he was grinning and what he knew, and if, after all, she had not better tap the window and tell him to stop the car, and keep clear of the whole business. Once she actually did lean forward and gently rap on the glass; but all that happened was that the car moved a little faster and the monkey-faced chauffeur grinned at her more broadly than ever.

When eventually the car pulled up outside Schnitzer's impressive-looking residence, the chauffeur sprang from his seat and flung open the door of the car before Josephine had time to sit upright, and, as she got out, he waved a hand towards the house in a gesture which was more a command than an invitation. Just for a moment she thought of turning away from the steps of the house and darting off along the pavement, but she got the impression that if she showed the least sign of attempting to escape the monkey-faced chauffeur would spring at her. So she went, with as self-possessed an air as she could; muster, up the steps and rang the bell; and a few moments later she was in Schnitzer's library, and he was heaving himself from a low armchair to greet her.

"This is good of you, Miss Brady," he purred in that smooth voice of his, as he took her hand.

Regarding him with eyes more critical than usual, Josephine agreed that it was good of her. As to whether it was equally good for her, she had her doubts. He fitted very well the picture of him, which she had pieced together. He was a powerfully built, prosperous-looking man in the early fifties, broad in the shoulders, black-haired and red-faced. According to her informant in the office, he had been born with the black hair, but had acquired the red face with considerable pleasure to himself and considerable profit to his wine merchant. He gave the impression that nature, when fashioning him, had tried to draw attention to too many points and had overdone the emphasis. His forehead was too low and his nose too long; his eyes were too small and his permanently out-thrust lower lip too full. As regards his girth, Josephine's desk-mate had said that there was no need to remark on the obvious.

"I guess you're feeling pretty sore with me, eh, Miss Brady?"

"Sore?" she echoed.

"Breaking in on your evening like this. I dare say you had a date with some nice young fellow—"

He was still holding her hand, and Josephine withdrew it sharply.

"Not at all," she said. "I was quite free this evening."

He regarded her from under lowered lids and half smiled.

"Lonely little girl, eh? Well, now, that's too bad. Chester County must be full of blind guys to leave a little girl like you sitting at home and knitting."

This, Josephine reflected, was no doubt all according to schedule. In a few moments he would probably try to kiss her. She wondered which would be the best spot to hit.

She took out her notebook, opened it, seated herself on a chair and glanced at him expectantly, her pencil poised.

"Yes, Mr. Schnitzer? Just a couple of letters, isn't it?"

"Sure," he replied. "But we don't have to hurry. There's plenty of time for the letters. Take a comfortable chair and have a cigarette."

"Thanks, but I'd rather get the letters done if you don't mind. I'm in rather a hurry; I want to get home as soon as possible—"

"Sure," he said again. "Of course you do, and I won't detain you five minutes longer than is necessary. But there's nothing against your having a cigarette while we're waiting."

He offered her his case.

"Genuine imported Egyptian," he told her. "I've never yet known a little girl who didn't fall for a genuine imported Egyptian."

She hesitated a moment and then took a cigarette, Schnitzer supplying her with a light.

"Thank you, Mr. Schnitzer," she said. "But what are we waiting for?"

"There's certain information I want from my agent on the coast before I can dictate the letters," he told her. "He's to speak to me on the 'phone, but he's not through yet. He'll be on the wire any minute now, and then we can go right ahead."

Josephine closed her notebook with a snap and got up from her chair.

"In that case, Mr. Schnitzer," she said firmly, "I'd better come back later."

She took a step forward, but Schnitzer, standing between her and the door, did not move.

"That's not very sociable. Miss Brady, is it?"

She shrugged a shoulder.

"I didn't understand on the telephone that this was to be a social call."

"No?" He smiled. "Well, there's no reason why it shouldn't turn that way, but you're making it difficult. It's kind of discouraging when a nice little girl thinks you're such poor company that she'd rather take a walk around the block than spend ten minutes with you while a 'phone call comes through." He laid a hand on her shoulder and urged her towards an armchair. "Sit down, my dear, and take off your hat and enjoy your cigarette, and I'll find you a glass of wine—"

Josephine spun round and faced him.

"Mr. Schnitzer, I came here to take down some letters, and if you're not ready to dictate them now I'd much rather go and come back when you are ready. I don't want a glass of wine."

"Maybe you don't," replied her employer. "But I'm telling you that you need one. You're looking pale, and paleness doesn't suit you. Pretty hair like yours needs a touch of colour to show it off. I guess lots of young fellows have told you you've got pretty hair, eh, honey?"

The next instant he had no cause to complain of her pallor. Her cheeks were crimson and her eyes blazing as she faced him defiantly.

"Please understand, Mr. Schnitzer," she began furiously, "that I didn't come here to discuss my hair, and if you've no letters to dictate—"

"Haven't I told you," interrupted Schnitzer plaintively, "that I'm waiting for my agent on the coast to come through on the wire? Come now, my dear, there's no call for you to be awkward about things. A nice little girl like you—"

"I'm going," she announced suddenly. Again she took a step forward, trying to brush past him, and this time he deliberately stepped in front of her. His smile had vanished and his mouth grew grim.

"Sure you're going—just as soon as I say so," he snapped. "But not before, Miss Brady. When I pay a girl twenty dollars a week, I guess she's going to do as I say or—" He stopped abruptly, and his smile returned.

"Forget it, my dear," he said. "I talk that way sometimes when things don't go just as I want them to, but it doesn't mean a thing. Still, there's no sense in you running away and walking round the block. That kind of hurt me. It looks like not trusting me, and if a girl can't trust John P. Schnitzer to treat her right, I'd like to know who she can trust. Well, forget it!"

He crossed to the heavy tapestry curtain that hung across the archway which led into an adjoining room, and beckoned her to him. She hesitated, and then, as he smiled at her reassuringly, crossed slowly to him. After all, there was no sense in losing her job if she could possibly keep it, and Schnitzer might be all right....

He pulled aside the curtain, switched on the light and drew her into the room.

Josephine glanced round. It was a dining-room, richly furnished, with a thick soft carpet and concealed lighting, rose-tinted, that gave it an air of warmth, softness, intimacy. The oval table in the centre was laid for dinner. Josephine noticed that places were laid for two.

"Sort of cosy, eh, honey?" purred Schnitzer.

She glanced at him quickly.

"I was expecting a friend to dinner," he went on to explain, "but he has let me down at the last minute. Still, as things have turned out, I guess I'm not feeling particularly sorry. What do you say, my dear, to a nice little dinner while we're waiting for my man to 'phone?"

"I'm sorry, Mr. Schnitzer," she began, "but I can't possibly—"

"I'm saying you can." The snap was back in his voice now.

"But I'd much rather not—"

"And I'm telling you you're going to." He was between her and the curtain, and his mouth was ugly. Job or no job, she must get out of this.

"Do you get my meaning?"

She nodded.

"Perfectly, thanks," she replied calmly. "And now see if you can get mine, will you? I'm not dining with you; I'm going—now. And I'm going because I don't believe there's any 'phone message to wait for or any letters to write, and that being so, I'd sooner eat peanuts on the sidewalk than stay here and dine with you."

His hand shot forward and gripped her arm. And then suddenly he seemed to check himself and stood rigid, listening. Josephine heard footsteps in the corridor. The door of the adjoining room was opened, and then came the sound of men's voices.

"Not here, boys. But he'll be somewhere around." Schnitzer's hand released her arm and he turned and went quickly between the parted curtains.

"Hallo, boys!" she heard him exclaim. "Glad to see you again—"

"Sure you are!" came the drawling reply. "Put your hands up, Schnitzer, and get over there by the arm-chair. I guess you'll be wanting something soft to fall on."

Josephine, scarcely daring to breathe, and with her heart thumping furiously, carefully drew the curtain an inch aside and peeped through the opening. She saw Schnitzer at the farther end of the room. His plump, white hands were held above his head, shaking violently; his face was a ghastly grey; his heavy lips were working, and his eyes staring, wide-open, at the two men standing just inside the door. One was a tall thin man with a face like a ferret's, and he had a gun held loosely in his hand. The other, who was not unlike Schnitzer in appearance, had his hands thrust deep in his pockets and was staring at the financier with an expression of sneering malevolence on his face.

"Say, boys, listen!" babbled Schnitzer. "You've got no cause—Perryfeld, I never did you any harm" The shorter man, whose name seemed to be Perryfeld, drew a hand from his pocket and made a gesture of impatience. He turned towards his companion and took the gun from his hand.

"I guess I've a better title than you to give him the works, Mike," he said, and turned again towards Schnitzer, gun in hand. "I reckon you should feel darned honoured, Schnitzer," he said. "I've taken the trouble to come here in person—at great inconvenience—to blow you to hell—"

"Perryfeld—for God's sake—listen—"

"Money talks," replied Perryfeld coolly, "and you're behind with your payments, Schnitzer. You've been dumb for so long now that I reckon the sooner you're dumb for good the better."

He raised his gun and deliberately pointed it at Schnitzer. Josephine released the curtain and crouched against the wall, her hands over her face.

There came a muffled report and she bit into her thumb to stop herself screaming.

"O.K., Perryfeld," drawled a voice. "We'd better be quitting."

The sound of the door being closed—footsteps in the corridor—and then silence. Josephine's hands left her face. With an effort she forced herself to part the curtains and look into the room. Schnitzer no longer stood where she had last seen him, but there was a huddled mass beside the armchair....

She went slowly forward and paused beside the shapeless thing that had been John P. Schnitzer. She saw a small red stain slowly spreading on his shirt-front. She remembered screaming, and the room reeling round her, but remembered no more.

CAPTAIN "TRICKS" O'REGAN, of the Chester County Police, was a man of strong convictions, and not the least of these was a conviction that, since he was expected to provide the citizens of Chester County with the sense of security which made it possible for them to sleep comfortably at night, it was up to Chester County to provide him with an office in which he could work comfortably by day. And the outcome of this conviction was the large bright room which he occupied at Police Headquarters. With its high windows, dull silver radiators, substantial furniture, busily ticking tape machine, and glass-windowed service office, commonly termed the "glass-house", it suggested rather the sanctum of a prosperous stockbroker than a place devoted to the discomfort of criminals, in comparison with whom, as O'Regan put it, stockbrokers were the merest amateurs.

Sergeant Jackson sauntered from the glass-house and began to pace the room restlessly.

"I wish somebody would do something," he grumbled. "This place is getting on my nerves."

Sergeant Geissel, absorbed in watching the tape machine, glanced up and grinned.

"Good policemen shouldn't have nerves," he remarked sententiously. "And anyway, it'll never be as quiet as I want it." He crossed slowly to the window, looking down at the almost deserted street below. "Do you know, Jack," he went on, "I've a feeling that there is something doing."

"Ain't you always? And, say, everybody in the station-house is feeling that way tonight. A while ago I cracked a nut and the station sergeant jumped out of his chair."

"This nerve business must be catching," grinned Geissel.

There was silence for some minutes, the one man continuing his pacing, the other staring, broodingly and unseeing, through the window. Then:

"I wouldn't be on patrol for a whole lot of money," Geissel remarked quietly.

Jackson stopped short in his striding.

"Say, what's eatin' you, Geissel? It's not like you to get jumpy."

Before the older man could reply, the door burst open and a short, thick-set, square-shouldered man appeared.

"Hallo, Reil!" greeted Jackson. "What's the hurry?" Detective-Sergeant Reil, ignoring the question, asked: "Where's the Chief?"

"Down at the City Hall," Geissel told him. "Why? Anything wrong?"

The newcomer's naturally stern features looked grimmer.

"I should say there was! I got my third quitter in a month."

Jackson whistled.

"You don't say! A patrolman?"

"Yeah—a patrolman. Can you beat it? Found him like that." He gave a ludicrous caricature of a man shaking with fear. "Corner of Brandt and Washington Avenue—couldn't even hold up his motor-cycle."

"Who was he?" asked Geissel.

"Connor."

"You don't say!"

"The Chief's at the City Hall, is he? Well, where's the Lieutenant?"

"He's around somewhere," said Geissel. "Find him, Jack."

When his subordinate had disappeared, Geissel turned a grave face to the other.

"Connor, eh? Well...."

He shrugged his shoulders, walked across the room to the wall on which hung a wooden frame which displayed a number of police badges. He stood for several moments in gloomy contemplation.

Red's voice broke in on his thoughts.

"I ought to take a stick to him and beat him up!" he said savagely.

Geissel half turned, his left hand pointing towards the frame.

"There's your answer!" he said. "One-two-three-four-five-six-seven—" counting with outstretched forefinger.

"Yeah," Reil assented.

"Seven patrolmen found slumped on the sidewalk!" went on Geissel, fierce indignation in his tone. "Seven murders that don't seem to matter a damn to anybody! Has anyone gone to the chair? Has anyone even been pulled in? Why, the murderers, whoever they are, haven't even been inconvenienced! Only three quitters? I guess you're lucky—"

"What's the trouble?" It was a harsh, authoritative voice that asked the question.

Reil stiffened to attention and saluted smartly. Lieutenant Edwin Lavine was a stickler for military discipline amongst his subordinates. A man of medium height, the breadth of his shoulders and his general bearing were eloquent of a former athletic build. The years, however—he was well into middle age—had done their work, and his figure, once lithe and vigorous, now showed a suspicious fullness. Lavine may have assisted the years; his tastes were sybaritic; he was a man who did himself well, and if, as a result, his liver wreaked its vengeance upon his temper, it didn't much matter to anybody, for Lieutenant Lavine's temper had always been his weak point.

"Connor refused duty, sir," reported Reil tersely.

The Lieutenant made an impatient noise with his lips.

"Refused duty, has he?" he repeated between his teeth.

"Yes, sir. Can you imagine? And he's been twelve years a policeman!"

"Did he come in?"

"No, sir. I found him when I was making my first round."

"Where is he?"

"Outside, sir."

"Bring him in."

When the other had gone, Lavine stood thoughtfully for some moments, and his thick lips were curved in an ugly expression as he muttered to himself:

"Connor... yellow, eh?"

"I'm not so sure about that, sir," Geissel ventured to put in: and Lavine turned round on him with a snarl.

"What do you mean?"

"Well, I don't know that I'd call Connor yellow. He's the bird who got that Polak family out of their shack when it burned—you remember? No yellow guy would have done what Connor did then."

The other grunted.

"Here he is," he said as the door opened to admit Reil and a patrolman. "We'll hear what he has to say. Now, Connor," as the man advanced across the room and stood rigid in front of him, "what's the big idea? Refusing duty!"

Connor gulped. It was evident that he was labouring under strong emotion and making tremendous efforts to regain his self-control. At last:

"Well, Lieutenant—" he began, and gulped again.

Lavine snorted.

"'Well, Lieutenant'!" he mimicked. Then, turning fiercely upon the patrolman: "Say, what's the matter with you?" he stormed. "What sort of a policeman do you call yourself? Afraid of the dark, huh? You make me sick!"

His contemptuous tone stung the man into at least temporary mastery of his feelings. He drew himself up and spoke jerkily, but more calmly.

"It was this way, sir. I was up on Washington Pike—there ain't a house there in a mile, and I got scared, that's all. You see, a man came up to me—a stranger—and asked me what I was doing so far off my patrol." Lavine broke in sharply.

"Oh! You were off your patrol, were you?"

"Yeah—just a little way."

"And why?"

"I saw some men get out of a car about a hundred yards farther on—and I went up to see what it was all about. One of 'em came back to me."

"And you beat it, huh? Got yellow—just because a man asked you why you were off your patrol! I suppose you didn't ask him for his badge or anything? He might have been a Federal officer."

"He was a stranger to me," Connor muttered sullenly. The corners of the Police Lieutenant's mouth curved in a contemptuous grimace which gave him an evil expression. His eyes raked the unfortunate Connor with a scorn that stung.

"I suppose you haven't got a gun?" he said icily. "I say you haven't got a gun, have you, you poor yeller rat! You get right back, sister!"

The patrolman drew himself up, his eyes flashing.

"I'm not going back!"

"Oh, no?" Lavine turned to Reil. "Where did you find him?"

"On his way to the station, sir."

The Lieutenant surveyed Connor coldly for some moments before he spoke.

"Now listen, you! You'll go right back to your patrol—"

"I tell you I'll do nothing of the sort!" almost yelled Connor. He was furious now. "Three officers have been killed on that pike since the New Year. Shot down like dogs—for nothin'. Seven officers in three months! I got a wife and three kids—"

"Why, you're nothin' but a kid yourself—a poor, whining, snivelling kid—afraid of the dark—afraid—"

Connor took a step forward and pointed a shaking hand towards the frame on the opposite wall.

"I ain't havin' my badge in that frame and that's a fact!" His tone was openly defiant now.

Lavine's eyes glinted.

"You're not having your badge in that frame, aren't you?" he breathed, slowly and quietly. Then in sudden fury: "I'll say you're not, you rat!"

Taking a quick step forward, he seized the patrolman's badge and wrenched it from his coat.

"I'll say you're not," he repeated. "I'm dumping it in the ash-can and you're going inside, where you belong! I'll have that coat off your back and I'm going to give you a number in the penitentiary! That's what I'll do with you! And I'll tell you something else—"

"Tell me!"

Lavine broke off short and turned round sharply, to meet the scrutiny of a pair of cold steel-blue eyes, whose owner had come into the room unnoticed.

There were stories told in the underworld about the eyes of Captain Patrick John O'Regan; how, for instance, Jake Sullivan had gone to the chair simply because, when he was being questioned, he hadn't been able to stand the penetrating stare of O'Regan's eyes, and had come clean with all the details of his crime; and how Jim Woolmer, as tough a guy as ever worked a racket, suddenly jumped to his feet and shouted: "For God's sake, Captain, don't look at a fellow that way!" It was generally agreed by those who had had the misfortune to come beneath their scrutiny that they made a man feel it was no use lying because O'Regan already knew every little detail which the wrongdoer was trying to conceal. "Tricks" O'Regan, they called him, because he was plumb full of tricks and you never could tell for certain whether he was kidding or not. Usually, it was said, it was safe to assume that he was. However much the devotees of crime in Chester County might dislike the tall, broad-shouldered young man with the keen blue eyes and obstinate jaw, they had to hand it to him that he had been instrumental in seriously thinning their ranks, and that he had not reached the rank of police captain at the early age of thirty-two for nothing.

"What's happening?" O'Regan asked.

Lavine, almost reluctantly it seemed, drew himself up and saluted.

"Patrolman Connor refused duty, Chief. He got scared up on the Washington Pike."

O'Regan walked across the room, hung up his hat and coat and seated himself at his desk.

"Refused duty, eh?" he said at length. "Refused duty—in this happy land where nobody gets killed but policemen! Say, that's too bad!"

He shot a swift glance towards the patrolman—a glance keen yet understanding; a glance that took in every aspect of the situation. Connor had been an exemplary officer for twelve years, with never a bad mark against his name. Yet here he was, his face white, his mouth working nervously, his hands clenching and unclenching, quite obviously in the grip of some very powerful emotion—so powerful as to force him to commit the almost unforgivable offence of refusing duty and of disobeying his superior's commands. O'Regan's glance took in the significance of this immediately; it also embraced every detail of the patrolman's appearance.

The Police Captain pointed to the man's coat.

"You mustn't go out like that, Connor. Your coat's torn. Make a note, Geissel."

"I did that, Chief," explained Lavine complacently.

"I took off his badge—" holding up his right hand, which still held the symbol of Connor's office.

O'Regan held out his hand for the badge.

"On yes? Very interesting—very dramatic," was his quiet comment. "Now we will put it back." He suited the action to the words, pinning the badge on the bewildered policeman's coat. "Now then, Connor, just tell me all about it, will you? You were frightened?"

"Yes, sir."

O'Regan sat down at his desk, rested his elbows on the surface and looked up encouragingly at the other.

"Where?"

"Up by the meadow, sir, where Brandt crosses the Pike."

"Where Patrolman Leiter was killed?"

"Yes, sir," was the eager response. "You remember Leiter, Captain? I found him. He said that a man came up to him and asked him what he was doing off his patrol—and shot him. Just what this feller asked me tonight." The words came in a torrent.

"Oh, rats!" The contemptuous interjection came from Lavine. He would have said more, but the cold scrutiny of O'Regan's eyes kept him silent.

The Police Captain turned again to Connor.

"A man came up to you and asked you that, eh?"

"Yes, sir." His voice was tremulous as he went on: "You know, sir, there's a racket around here—a racket nobody understands. Chester County is full of killers."

Lavine's harsh laugh interrupted him.

"Killers, eh? Sure—they frighten policemen to death!"

Again O'Regan silenced him, this time with an imperious gesture.

"Let Connor tell me his story, please. Go on, Connor—I think I understand, my lad."

"Living in this county," continued the man, "is like living in a haunted house. There's always something behind you—something you can't see and you can't hear. You're walking all the time with a gun in your back."

"Uh-huh!" grunted O'Regan. "You only saw one man?"

"Four, sir. They got out of a car—near the meadow."

"Whose meadow is that?"

It was Lavine who answered.

"I guess that's Mr. Perryfeld's," he drawled.

"Thank you." Then, turning again to Connor: "And you got scared?"

The patrolman nodded.

"I certainly did, sir. You think I'm a poor yeller—"

O'Regan cut him short.

"No, no, no, I think nothing of the sort. You simply got scared. It is quite understandable. Personally I have never known what fear is, but I understand it exists—maybe one day I'll make its acquaintance. I've never been to the moon, but I know there is such a place." He sat for a moment or two in thought, his chin cupped in his right hand. Then he turned to Lavine. "Relieve Connor," he ordered. "Put him on the South patrol."

The Lieutenant looked his astonishment. He could hardly believe his ears. Here was a patrolman guilty of the most heinous offence in the police code, and the Chief was talking about "relieving" him! He could not have heard aright.

"Did you say 'relieve Connor', Chief?"

"Sure."

"But you'll be suspending him, won't you?" O'Regan rose, and flicked an invisible speck of dust from his jacket as he replied:

"No, I shall not be suspending him. Do you mind?"

"Very good, sir." Lavine's tone was sullen and the shrug of his shoulders almost offensive. Then, turning to Connor: "Come on, you," he ordered harshly.

"Just a moment." O'Regan held up a detaining hand. "Connor, you'd never seen these four men before, had you?"

"No, Chief. I didn't see 'em rightly, anyway. I told the Lieutenant what I thought."

"Yeh—what you thought!" snorted Lavine. "What do you think with?"

It was O'Regan who answered.

"His brains, which were so nearly blown out tonight." Then, tapping the man on the shoulder: "O.K., Connor."

Lavine and the patrolman paused as they reached the door, giving way to the man who was at that moment entering the room. Walking up to the desk at which O'Regan had again seated himself, the newcomer jerked his head in the direction of the departing pair.

"Trouble, sir?" he asked laconically.

O'Regan nodded. He liked the tall, fair-haired Lieutenant Spellman, his second-in-command at Police Headquarters, as much for his economy of words as for the integrity and loyalty which he had always displayed. He relied a great deal upon Spellman and the handsome-featured young lieutenant had proved that such reliance was never misplaced.

"Refused duty," O'Regan told him.

The other whistled.

"Another, eh? Where?"

"At the corner of Brandt and Washington."

"You've had three men bumped off on that same point," Spellman recalled.

"That's so—and all for the same reason—seeing people who thought they might be identified."

"And three other patrolmen have turned in their badges," went on the lieutenant reflectively. "It looks healthy for Chester County!"

O'Regan rose from his desk with a weary gesture and walked to the wall where hung the frame displaying the seven badges.

"Look at that, Spellman. Those badges belonged to seven men—seven living men, with beds to go to, seven men who went to the pictures at nights and played pinochle and wished they were Rockefeller. And they're dead! Last Thanksgiving they were alive, eating turkey and making dates with girls."

Spellman nodded grimly.

"It's certainly tough, Chief; but that's how it goes."

The Captain turned round sharply.

"Why should it?" he demanded. "What had these boys done to deserve death? They did nothing but patrol on their flat feet and watch out for citizen's homes. Seven policemen murdered in three months," he went on, half to himself. "And today I've been at the City Hall receiving the congratulations of the Citizens' League for keeping Chester County free of crime!" He gave a short, derisive laugh. "Maybe they don't think it's a crime to shoot policemen. Free of crime—no rackets, no hold-ups—and here, right here, is the biggest racket and the biggest hold-up this country has known. Isn't it marvellous?"

He turned round, to find Lavine, who had re-entered the office, standing by his desk.

"Don't you agree, Lavine? Isn't everything grand?"

"Why, yes, Chief. But then, we've got a pretty good class of people livin' around here."

"Uh-huh. That's so—and a pretty good class of policemen dying around here. Don't forget that, Lavine—"jerking his head towards the frame.

The Lieutenant shrugged.

"I guess we've still got a force good enough to deal with rackets," he said complacently.

O'Regan swung round on him, his eyes alight with the intensity of his emotion.

"So they have in Chicago!" he exclaimed. "So they have in New York—but the rackets go on. The people of Chicago pay a hundred million dollars a year for protection. There isn't a trade that hasn't a grand union attached to it—Butchers' Protection—Baker's Protection! You pay to be a member or you're bombed and your trucks thrown over in the street. If you squeal you're beaten, and if you fight you're bumped. You talk about a handful of Bolsheviks holding down a hundred million people—why, Russia's a girls' school after this country!"

"Oh, say," protested Lavine, "Chester's clean! There hasn't been a booze murder in years."

O'Regan raised his eyebrows.

"That's so. But there have been seven coppers and John Harvey since Thanksgiving!"

"Harvey?" Lavine wrinkled his forehead as if in an effort of recollection. "Oh yes, I remember—but there was a woman in that—"

"Nobody said so," put in Spellman from his desk in the far corner of the room.

"I got the low-down on it, see?" retorted Lavine.

"There was no woman concerned," O'Regan declared. "John Harvey was killed because he wouldn't pay blackmail. That's the racket. Somebody in Chester County is putting the dollar sign on fear." His right arm shot out in a minatory gesture to some invisible enemy. "I'm going to get that somebody into the Smoky Cell. If my badge goes into that frame I'll get him!"

"I wonder," said Spellman, "why these swell families never come to this office? What have they got to be scared about?"

"That's easy," O'Regan told him. "They're afraid that somebody will think they're squealing. And all the people who aren't calling are paying."

"Why?"

"Because they've got to pay if they want to live. That's the big racket. That's why no other racket can live around here. I've seen it coming for a long time. Capitalizing fear—that's a grand racket. No rent to pay, no samples to carry, no booze to run. Fear's worth money—big money. The fear of death! Spell, you'd sooner pay money than die, wouldn't you? I wouldn't, but you would. Death means nothing to me—the O'Regans have always been like that."

There was a simplicity about Tricks O'Regan's boastfulness which robbed it of all offence. It was perfectly true, as he said, that he did not know the meaning of fear, and his simple reiteration of this fact, which, made by any other man, would have been nauseating, gave added charm by reason of its naiveté and obvious honesty.

"But who's to kill 'em, Chief?" persisted Spellman. "There's no gang in town—never been a report of any strangers."

Tricks smiled.

"Suppose they don't live in town? Suppose they come just when they're wanted? Who could report? The patrolmen? What could they report? The arrival of suspicious-looking strangers, that's all." He paused for a moment and into his face came a look of grim sternness as he continued, a shade more slowly: "And the men who could have reported it are dead—seven of 'em! There isn't a patrolman working outside town who doesn't come off his beat looking like the last ashes of hell.... What is it, Geissel?"

The sergeant's head had appeared round the door of the glass-house.

"Murder up at 203A Lincoln Avenue, Chief," he reported tersely. "Guy named Schnitzer—John P. Schnitzer. Shot through the heart."

"Schnitzer, eh? Now who the deuce is Schnitzer?"

"He's that rich financier fellow," supplied Spellman. "We've had an eye on him for some time—all sorts of funny stories about him.... Girls," he added succinctly.

"That's right," Geissel agreed. "There's a girl in this. Byrne's on the wire—he's taken charge of the case—and they're pulling her in. Apparently she was there when it happened."

THE first impression that seeped back into Josephine's consciousness was of a continuous steady drone. It was rather soothing than otherwise, and for some time she listened to it without making the effort to speculate on what might be its cause. She felt terribly tired, and the least mental or physical exertion seemed too stupendous a task to be attempted. She had a vague idea that something unpleasant had occurred, and the longer she could postpone the moment when she would remember what it was the better. Her head was aching appallingly.

There came a strident screech. She recognized that, anyway; it was the screech of a motor klaxon. That steady, continuous hum, she supposed, was the sound of an engine. She imagined that she must be in a car. But whose car? And where was she going? She could remember getting into a car—oh, yes, of course—Mr. Schnitzer's car—with the funny little monkey-faced chauffeur. She was going to Mr. Schnitzer's apartment on Lincoln Avenue. There were some letters to be dictated which couldn't be done at the office. But she had an idea that she had already been to Mr. Schnitzer's apartment. She must have been there, because she remembered the room quite distinctly. But she hadn't taken down any letters; she was quite sure of that. It was all very muddling. She made a tremendous mental effort. There had been something about a curtain—a heavy tapestry curtain. She remembered standing close to it—pulling it aside ever so carefully—peeping through....

Memory returned with a rush: Mr. Schnitzer, terribly scared, with his hands above his head—the two men standing by the door—the muffled report—and then that horrible shapeless heap on the floor, with the red stain that was spreading....

She shuddered and tried to open her eyes, but her eyelids only fluttered feebly. She felt that she must open them. She must know at all costs where she was. She was in a car, of course—travelling very fast by the sound of it—and there was a smell of tobacco smoke; a cigar, she thought....

"She's coming round, Mike."

The voice cut sharply into her consciousness. She would know that voice anywhere—never be able to forget it.... "I guess I've a better title than you to give him the works."... The fat man with the gun, pointing it at Schnitzer.... Pennyfeld or Perryfeld or something like that....

She heard another voice, which she recognized as belonging to the thin man with a face like a ferret's.

"I'm all for the milk of human kindness, Perryfeld," said the voice. "You may as well do the job before she comes to."

"No hurry," grunted Perryfeld.

"If she comes round and sees the gun she'll yell, and she's got a voice that'll carry here to Police Headquarters and back again."

"I guess we ought to be grateful," replied Perryfeld. "If she hadn't let out that yell we'd not have known she was there. She's seen too much to be left lying about where the police can find her."

"Sure. We'll get the job done quick and leave her where the police won't find her."

"I'll do it in my own time," snapped Perryfeld. "If you're so darned keen on getting it done, why don't you do it yourself?"

"I'm driving, ain't I?"

There were several moments of silence, and then 'Perryfeld's voice came again:

"Say, Mike!"

"Hallo!"

"She's a swell kid!"

"Trust Schnitzer."

"Maybe there's no need, after all—"

"No need? Say, Perryfeld, what's bitten you? Not going all soft and lovesick, are you? You're right—she knows too much to be left to go squealing to the police, an' she's not going to be left. If you're looking for a swell kid to comfort you in your loneliness, you've got to keep on looking, because you haven't found her yet."

"Huh!" grunted Perryfeld.

"What I mean is, don't get toying with the idea of a honeymoon, because this kid's booked for a different sort of trip. She'd prefer it, I shouldn't wonder. Shut your eyes, sweetheart, and turn your head away, and let her have it."

Very cautiously Josephine opened her eyes—just wide enough to enable her to make out the shadowy figure of Perryfeld sitting on the opposite seat of the car. She watched the red tip of the cigar as he raised it to his mouth, and in the glow as he drew at it she caught a glimpse of his other hand resting on his knee. There was no gun in his hand yet, anyway. They meant, of course, to shoot her. She did not feel particularly frightened—not nearly so frightened as she had felt when she had seen Mr. Schnitzer standing with his hands above his head. If they intended shooting her, there was nothing that she could do to prevent them. Screaming wouldn't be of the least use; they were out in the country somewhere, travelling very fast, and nobody would hear her. Besides, if she started screaming they would certainly shoot....

She noticed that the car was slowing down. It stopped and she heard the man who had been driving get out of his seat. The door was opened and she could see the outline of his head and shoulders as he stood in the opening. Her heart began pounding. They were going' to do it now, she supposed. It would be of no use struggling; they'd only hurt her all the more if she struggled. She would just lie still and close her eyes.

"Say, what's the game?" inquired Perryfeld.

"I'm asking you," replied the man called Mike. "You've been playing it long enough, anyway, Perryfeld. Been holding her hand and stroking her hair, I shouldn't wonder, and I'm through with that sort of stuff—see? If you can't brace yourself up to do the job, then I'm doing it myself—"

Josephine saw a quick movement of Perryfeld's hand. There was a gun in it now. She had just caught the gleam of metal for an instant and she could make out his white hand grasping the butt.

"Get to hell out of this!" There was suddenly a rasping snarl in Perryfeld's voice. "Do the job yourself, will you? Like hell you will! Who's running this outfit, me or you? Not you, Alike Osier, and the sooner you lay hold of that fact, the better. Now then, back to the wheel and get going."

"Listen, Perryfeld, there's no sort of sense—"

"I'm telling you there's going to be no shooting—see? This is my show and I'm running it my way. If you don't like it, you can quit." The gun moved a few inches nearer. "But you'll quit my way. Get that?" Alike did not move.

"Listen," he said again. "You just can't afford it. All this blue eyes and golden hair stuff—it's not worth it. You can't chance letting this kid go blabbing to Tricks O'Regan—"

"She won't," snapped Perryfeld. "Not my way. I reckon she'd be more helpful to Tricks O'Regan dead than alive, and there's no sense in presenting him with an extra bit of evidence. You've got no foresight, Mike; that's your trouble—no brains, no imagination. If it hadn't been for me, Tricks O'Regan would have got you a dozen times, and you know it. O'Regan will get busy on the Schnitzer trail, but it won't lead him anywhere so long as this kid's still breathing. But if we stop her breathing... Sure, Mike, you've no brains. That'd be another trail for O'Regan, wouldn't it? And sooner or later the two trails would cross, and that's the spot where he'd find you and me standing."

Mike seemed to hesitate.

"I'm not saying you're not clever, Perryfeld—"

"Sure I'm clever."

"But we don't want her waking up and yelling just when we're passing a cop. There's no trusting women to keep quiet when you want them quiet. You'd best shove something in her mouth to damp it down a bit if she starts yelling. I'd feel kind of safer."

"O.K.," replied Perryfeld.

Josephine saw the flutter of a white handkerchief and realized that Perryfeld was folding it on his knees. She felt certain that if he started to tie it across her mouth she wouldn't be able to help screaming; and if she began screaming it was ten chances to one that Mike would shoot her. She saw Perryfeld lean forward, saw the white bandage approaching her mouth.

"It's all right, Mr. Perryfeld," she said quietly. "I'm not going to scream."

Perryfeld sat back suddenly in his seat.

"If I promise not to scream there's no need to tie up my mouth, is there?"

"Huh!" grunted Perryfeld. "So you're awake, are you?"

"What did I tell you?" began Mike excitedly. "You'd much better have—"

Perryfeld silenced him with a gesture.

"Now listen, Miss Brady," he said. "You are Miss Brady, aren't you? You're Schnitzer's secretary?"

"I was," replied Josephine significantly.

"I guess we won't split hairs. You just listen to what I'm saying, because if you should happen to forget some little thing I'm telling you you'll be spared the trouble of remembering anything. You were in Schnitzer's apartment this evening, eh?"

"I went there to take down some letters," she explained. "Mr. Schnitzer came through on the wire and asked me to go, and sent his car for me—"

"The point is, you were there, and people knew you were there—the chauffeur, for instance—and, that being so, it's no kind of use pretending you weren't. If anyone asks you—the police, for instance—you'll say you were there—tell them just what you've told me. Got that?"

"Yes, Mr. Perryfeld."

The man scowled.

"Where were you, eh?"

"In the dining-room, behind the curtain."

"And when you were there behind the curtain, you saw something, eh?"

"Sure," she nodded.

"You don't have to beat about the bush, Miss Brady. What did you see?"

Josephine took a deep breath.

"I saw—saw you—shoot Mr. Schnitzer."

"Did you hell!" exclaimed Perryfeld. "Now listen, Miss Brady, and I'll tell you what you saw. You saw just nothing at all. Nothing, d'you hear? You heard voices, and you heard a gun go off, and when you went into the other room and found Schnitzer on the floor there was nobody else there. You didn't see me, nor Mike here, nor anybody. Is that clear?"

"Ye-es, Mr. Perryfeld."

"And my name isn't Perryfeld," he went on. "You don't know my name—see? You've never heard of a fellow called Perryfeld. If anyone should ask you, you just know nothing more than I've told you. You fainted—see? And the next thing you remember is finding yourself lying on the grass by the side of the road somewhere."

Josephine began to breathe more easily. After all, they weren't going to shoot her. They were going to dump her by the roadside.

"And don't go running away with the idea you can double-cross me," added Perryfeld, "because you can't do it. I'll know. I'd sure hate to see you all messed up like Schnitzer was, but if you try any funny business that's what's coming to you. Just say one word more than I've told you and you'll see. We'll be watching you. All the time. If Tricks O'Regan pulls you in, don't fancy I won't know what you're telling him, because I'll know every word you say; and if you say things I don't care about a dozen Tricks O'Regans aren't going to save you. Just remember, wherever you are, there's a gun not many inches away from you—even at Police Headquarters. If you don't think you can keep your mouth shut—"

"I can," she interrupted breathlessly. "You can trust me absolutely—on my word of honour—"

"Perhaps," interrupted Perryfeld. "But I'm not proposing to trust you. I'm keeping an eye on you all the time—and a gun. Any moment I want you I'll know where to get you. I suggest you bear that in mind, Miss Brady, or you'll be losing your good looks. And now you'd better get started; you've a longish walk in front of you."

She got hurriedly out of the car, and, as she did so, the man called Mike jumped into the driving-seat, and a moment later the high-powered car was roaring away.

For a time Josephine stood still, watching the tiny red glow of the rear-lamp as it grew fainter and fainter. She felt dazed, and her head was still throbbing painfully. So much had happened, and she couldn't remember anything very clearly. All that seemed to matter at the moment was that she had been terribly close to death and by some miracle had escaped. She might have been lying on the roadside now, looking like Schnitzer had looked. She shuddered, and glanced around her. She had not the slightest idea where she was, but she knew that at all costs she must get away quickly. Perryfeld might change his mind and come back But she must remember not to call him Perryfeld—even to herself. She didn't know his name, had never seen him, had seen nothing and nobody. The least little slip and that gun which was always within a few feet of her would go off. She knew that it had been no idle threat; things like that were common enough these days.

She turned and glanced back along the road. There was a glow in the sky in that direction, and that way lay home. She began walking, walked, faster and faster, and then broke into a run.

For some minutes she ran on, pausing now and then to recover her breath, but only for a few seconds. She had a feeling that all the time out here on the road she was being watched, that she must get back home quickly, that she wouldn't be safe until she was in her own room with the door shut and locked.

There came a blaze of light, and a powerful car, travelling fast towards the city, swept past her. She started violently. But it wasn't Perryfeld's. This was a light green car, and Perryfeld's had been black. But that meant nothing. There would be others besides Perryfeld.

Suddenly she halted abruptly, catching her breath. Twenty yards or so ahead the big green car had stopped, and a man was walking back towards her. She wanted to turn and run in the opposite direction, but remembered that she must not do that sort of thing. She must not let anyone guess that anything unusual had happened to her or that she was frightened. She must be quite natural and self-possessed if she didn't want to start people asking questions. She could be. She had been calm enough in the car with Perryfeld, and a gun only a foot away from her....

The man paused as he reached her.

"Anything wrong?" he inquired.

"Wrong?"

He nodded.

"Why should there be anything wrong?"

"I just wondered. I saw you running, and I thought you looked kind of worried."

She pressed a hand to her side.

"Stitch," she smiled. "I'm out of training. Too many cigarettes, I expect."

"Running far?"

"Home," she told him.

"And where's home?"

She mentioned her address and he smiled. She rather liked his smile.

"Some run!"

"Some runner," she laughed.

"Sure," he agreed. "But twenty miles is a longish way—"

"Twenty miles? You don't mean to say—"

"It can't be less," he told her. "Didn't you know?"

"No—at least—I didn't think it was quite so far. You see—"

She hesitated, and he smiled again.

"Think up something good," he advised. "I'm not easily kidded. It might save a whole lot of trouble if you told me the truth. Something's wrong. Girls don't go running twenty miles in court shoes and silk stockings just to get their weight down. What's the trouble?"

"Well, it isn't exactly any trouble," she told him, hesitating. "You see, I—I went out—with a friend—in his car—and he started getting a bit fresh, and because I wouldn't stand for that sort of thing he said he didn't see wasting petrol on carting a snowdrift around—"

"He dumped you?"

She nodded.

"Too bad," he smiled. "How's the stitch?"

"Oh, it's gone now, thanks."

"It'll come back," he warned her, "long before you've covered twenty miles. You'd better get aboard my bus and let me take you."

She hesitated, eyeing him keenly. She decided that he looked all right. Anyway, she'd never make the distance on foot, and she'd have to risk it.

"I expect you're right," she said.

They hardly spoke during the drive, and, as the car pulled up outside her house, she jumped quickly out and slammed the door.

"Thanks," she said. "I'm terribly grateful."

"Glad to have been useful," he said. "But I'd like to meet the guy that dumped you."

She smiled at that.

"I guess you wouldn't."

"If ever I do, I've a few kind words to say to him and I'd welcome the chance of saying them. What's his name?"

"Name?"

He nodded.

"In case I run across him."

"Smith," she told him. "Good night!"

She turned and hurried indoors, and a few moments later was in her room. Tossing her hat on to the table, she flung herself into an armchair. There, for a long time, she sat with her hands covering her face and her fingers pressed against her temples. She did not want to think, yet again and again she went over each scene of that evening of horror—the look on Schnitzer's face as he had remarked on her pretty hair; the touch of his hand as he grasped her arm; the huddled figure on the floor; Perryfeld's glowing cigar; the gun glinting in his hand; his voice dictating the terms on which she might remain alive; the stranger with the rather nice smile who had come to the rescue. She made an effort to dismiss it all from her mind. It was over now, anyway. She was back home, safe in her room.

She lighted a cigarette and forced herself to smile. There was nothing she could do, and it was no use worrying. Perryfeld couldn't be watching her now, anyway. There was no gun here within a few feet of her ready to go off. Perryfeld might only have said that to scare her. Probably the best thing she could do would be to ring up Police Headquarters and tell them everything. Perryfeld couldn't possibly know that she had done it.

She crossed to the telephone and stood beside it, hesitating. "Even at Police Headquarters," Perryfeld had said. That might, of course, have been bluff, but

She started violently as the telephone bell rang and her hand shook as she took up the receiver.

"Hallo!"

"Is that Miss Brady?"

"Yes."

"I must want to tell you, Miss Brady, you did very well tonight."

"Who-who's speaking?"

"Well, my name's of no consequence, but I guess you'll remember me. I drove you home."

"Oh!"

"That lie about the guy who dumped you because you wouldn't stand for petting—that was good. Mr. Smith, wasn't it? Much wiser to spin that yarn than tell the truth, Miss Brady. If you'd told me the truth I wouldn't have been surprised to hear a gun go off."

"I don't understand—"

"I guess you do," replied the voice. "The gentleman who took you for a car drive this evening told you something about telling the truth, didn't he? I guess he'll be glad to know you've not forgotten what he said to you." She drew in her breath sharply. So the man with the rather nice smile—Perryfeld had sent him—to test her out—see if she was to be trusted.

"What—why have you 'phoned?"

"Just to let you know we're watching over you, honey, and you've no cause to worry. Good night!"

She heard him cut off, and frowned thoughtfully as she replaced her own receiver. Then she turned suddenly, crossed to the door and turned the key in the lock.

LIEUTENANT SPELLMAN was standing by the tape machine, running the narrow strip of paper through his fingers, when Lavine came striding into the office. Just inside the door Lavine paused and stood for a few moments frowning across at him.

"I say, Spellman!"

"Hallo!"

"What's the great idea?"

Spellman continued scrutinizing the tape.

"Huh?"

"Leaving Mr. Perryfeld flat."

"I thought you were looking after him. Perryfeld's not my little brother."

Lavine made a gesture of impatience.

"There's no reason why you should always be so darned up-stage with him."

Spellman glanced across at him.

"And there's no reason, Lavine," he said, "why you should have people like that hanging around. Perryfeld pretty well lives here these days—when the Chief isn't about."

"What if he does?" demanded Lavine aggressively. "Have I got to ask you what friends I choose? Make a list of suitable acquaintances for a police lieutenant and get you to O.K. it, shall I? Like hell I will!"

Spellman, with a shrug, turned his attention again to the strip of paper in his hands.

"Make your own friends, Lavine," he said, "but keep them out of my way, that's all. We don't seem to mix well."

"Huh!" granted Lavine. "Grateful, aren't you?"

"For Perryfeld?" He shook his head. "Keep him Lavine. He's all yours."

"I was trying to give you a break."

"You've a kind heart."

"I was putting you near the money, anyway," said Lavine. "I suppose you don't want to be near the money, eh?"

Spellman grinned.

"I guess I'm near enough," he said. "I live next door to a bank."

"All right, leave it. If you feel like living on your pay, that's your affair. But you're a darned fool, Spellman."

"Sure I am," smiled the other. "And there's nearly a hundred million in these United States who are just the same kind of fools. They prefer to live on what they can earn honestly. Queer, isn't it? Kind of unnatural, eh, Lavine! A hundred millions who never take anything on the side and who'd hand you back your pocket-book if you dropped it. Never heard of those guys, have you? Well, I happen to be one of them. We don't get many write-ups, but we're there all the same."

"Sure you're there," sneered Lavine', "and you'll stay there—put! Still, if you're content—"

He stopped abruptly as the door opened and Perryfeld, smiling genially, came in.

"Ah, there you are, Mr. Spellman," he said amiably. "I thought I'd lost you."

"Mr. Spellman will show you round the report room, Mr. Perryfeld," said Lavine, and with a glance at Spellman went from the room.

Perryfeld jerked his cigar towards the tape machine. "Nothing much doing in your line just now in Chester County, eh, Mr. Spellman? Things have been sort of quiet lately, haven't they?"

"I guess they weren't quiet enough for Schnitzer last night, Mr. Perryfeld."

"Ah, yes—Schnitzer. I knew him slightly. There'll be a dame in that case somewhere, Mr. Spellman, from all I've heard of Schnitzer. Nothing else to keep you busy, eh?"

Spellman shook his head.

"We've had nothing in the way of excitement since the Harvey case."

"Too bad, that," said Perryfeld. "I was dining with him that night. He walked with me to the front gate, and he was going back indoors when he was shot. They never found the man."

"Men," corrected Spellman. "It was a machine-gun chopping."

"Sure, I remember. It sounded like a motor-cycle backfire. I was talking with the patrolman on the corner of the block when it happened."

"The patrolman was killed too," added Spellman. He crossed the room and pointed to the frame that hung on the wall. "See this, Mr. Perryfeld? These are the badges of every policeman who has been killed on duty this year." He waved a hand towards the second frame. "And all those since the Great War."

Perryfeld crossed and stared at the frames.

"Quite a few," he remarked.

"Yes, quite a few," agreed Spellman. "I'd like to be able to tell you, Mr. Perryfeld, that every killer who caused a badge to go in those frames went to the Smoky Cell, but they didn't."

"Smoky Cell? You mean the Death House?" Spellman nodded.

"Never heard it called the Smoky Cell before?"'

"No; it's a new phrase to me."

Spellman stared at him thoughtfully for some moments. Then:

"You've led a sheltered life, Mr. Perryfeld," he said. Perryfeld laughed easily and took a long draw at his cigar.

"Smoky Cell!" he chuckled. "Well, that's a nice picturesque way of putting it. Some of 'em made it, eh?"

"No, sir," said Spellman, with a frown. "None of them made it. Only one of those killers got even a life sentence, and five years later he was running a booze racket in Los Angeles. Such is life!"

Perryfeld turned away.

"Sure, that's the way things go in this wicked world, Spellman," he said, pulling out his cigarette-case and offering it. "Cigarette?"

"Thanks, but I don't smoke."

Perryfeld raised his eyebrows.

"You don't say! Married?"

"No, sir."

"But likely to be, eh?" chuckled Perryfeld. "Got your little love-nest all fixed, I guess."

"I have, sir."

Perryfeld nodded.

"Well, it's pretty tough, Spellman, trying to live on a lieutenant's pay. It's your funeral, of course, but I don't reckon it's doing right by the girl. Before you know where you are, along comes a little stranger, and then where are you?" He took his cigar from his mouth and stood gazing thoughtfully at the tip. "Listen, Spellman," he said, "if ever you find yourself in any kind of a jam maybe you'll come along and see me?" Spellman glanced at him quickly, and the hint of a smile appeared on his lips. Perryfeld continued to stare at his cigar.

"A thousand dollars one way or the other don't make any particular difference to me, Spellman."

"You're lucky. I seem to remember that you told me that once before."

"Maybe," said Perryfeld, with an airy wave of his hand. "I like you boys. You don't get the pay you ought, not by a darned sight."

"It'll keep me."

Perryfeld smiled.

"It'll keep you pretty short when there's two of you," he said. "Well, just remember what I've told you, that's all. You never know. Anything more to show me while I'm making the tour?"

"I think you've seen pretty well the whole outfit now, Mr. Perryfeld."

"You've got a racketeer fellow here, haven't you? Lavine was telling me—gave himself up, he said."

"Petersen?"

Perryfeld nodded.

"Yes, that was the name. He was trying to make the laundrymen pay for a new society, so Lavine was telling me. He had a bunch of hoodlums. Have you got 'em?"

"No—not yet."

"Huh!" grunted Perryfeld. "It beats me how these traders stand the rackets. It's blackmail and nothing more nor less. What sort of a fellow is this Petersen guy? I'd like to have a peek at him."

"Sorry, but that's against orders."

"Oh, say, there's no harm in letting me—"

As Lavine came into the room, Perryfeld turned to him. "Hullo, Edwin! I was just saying to Mr. Spellman I'd like to take a peek at that racketeer you've got inside."

"Sure," agreed Lavine readily. "He's no beauty, but you can have a look at him if you like."

"Petersen's in the dungeon, Lavine," said Spellman.

"Why? Has he been kicking up a fuss?"

"No."

"Then why put him there?"

Spellman shrugged his shoulders and went towards the door.

"I just thought I would—that's all."

"Got the key?"

"Yes," replied Spellman, tapping his pocket. "And I'm keeping it."

As Spellman closed the door behind him, Perryfeld jerked his cigar in his direction.

"Your boy friend's a bit fresh, Edwin."

Lavine nodded.

"He's young," he replied. "They get that way—"

"Means to get married and live on his pay."

"He'll change his mind about that when he's tried it for a while. They all start like that." He glanced hastily round the room. "Say, Perryfeld, I wanted to see you tomorrow."

Perryfeld turned away from him, strolled to the frame of badges and stared at it intently.

"That's O.K., Edwin," he said quietly. "Up at the Pike tomorrow at three."

"That'll suit me."

"I'll pick you up."

"O.K."

"How much will you be wanting?"

"If you could slip me a grand—"

"Sure thing."

He glanced round quickly as he heard the door open and saw Spellman waiting, his hand on the door-knob.

"Come right in, Miss Brady," said Spellman.

Josephine came in slowly. She was pale, and the dark circles around her eyes accentuated her pallor. Spellman, watching her closely, decided that she was frightened but determined to show no sign of her fright. Just inside the door she paused, looking swiftly round the room, and as her glance reached Perryfeld it became riveted on him, and Spellman saw her hands suddenly clench and her teeth show against her lower lip.

"No need to be scared, Miss Brady," he said. "The Chief wants to ask you a few questions, but you needn't let that worry you."

She turned to him and nodded; then once again her glance went back to Perryfeld. He was smiling at her genially, and as she went towards the chair which Spellman had pulled forward for her he came to meet her.

"Why, it's Miss Brady," he said, taking her hand and shaking it warmly. "How d'you do, Miss Brady?" Josephine withdrew her hand hastily, and Spellman frowned.

"Is Mr. Perryfeld a friend of yours, Miss Brady?" he asked.

"Sure I'm a friend of hers," said Perryfeld hastily. "We're old friends—eh, Miss Brady?"

Josephine stared at him in bewilderment. What was Perryfeld doing here—at Police Headquarters? And why was he suddenly claiming friendship? Perhaps he had known that she would be called in and questioned this morning and had risked coming there himself to make sure that she should say nothing....

"You remember me. Miss Brady, don't you?" said Perryfeld, and the look in his eyes told her closely what her answer must be.

"Oh yes!—I think so," she stammered. "Yes, of course I do, Mr. Perryfeld."

"Sure you do," he said. "Mr. Schnitzer introduced me to you, didn't he?" The smile left his face and he sighed heavily. "A bad shock for you, I'm afraid, Miss Brady. Poor Schnitzer! You'd never have thought a man like him had an enemy in the world. And you were there when it happened, weren't you?"

"You don't have to answer questions from Mr. Perryfeld, Miss Brady," said Spellman quietly. "And you don't have to ask them, Perryfeld. If there are any questions to be put to Miss Brady, the Chief will put them."

Perryfeld gave a shrug.

"I'm only saying what's in the papers, Mr. Spellman," he said. "No harm meant. The reports all say Schnitzer's stenographer was there when the shooting happened." He turned to Josephine again and patted her shoulder. "You've no cause to worry, my dear," he said. "You just tell them the simple truth and stick to it, and the police aren't going to hurt you. That's so, eh, Mr. Spellman?"

Spellman nodded.

"All you've got to remember," continued Perryfeld, "is not to try any funny business. Funny business don't pay, Miss Brady. The people who get into trouble when they come to Police Headquarters are the ones that try funny business."

"It's no use keeping Miss Brady hanging around, Spellman," said Lavine. "There's no knowing when the Chief will be in. I'll ask her a few questions and then she can go—"

"The Chief wants to see Miss Brady himself, Lavine."

"Of course he does—who wouldn't?" smiled Perryfeld. "But the Chief's not here, Mr. Spellman, and this is no sort of place to keep a lady hanging around. It'd get on anyone's nerves who isn't accustomed to it. It gets on mine sometimes. I guess I'll take Miss Brady and give her a cup of coffee and a cigarette—"

"Oh no—please—I'd rather not," interrupted Josephine hastily. "I'd much rather stay—I mean, I don't fancy a coffee just now, thanks, Mr. Perryfeld—"

"Well, you're not arrested, you know," said Perryfeld, "and if you'd care to take a bit of a stroll until the Chief arrives there's no reason why you shouldn't." Instinctively she moved closer to Spellman.

"Thanks, but I'd rather wait here," she said.

Perryfeld went to her and laid a hand on her shoulder. "Listen, Miss Brady," he said, and as he smiled at her she saw that ugly look in his eyes again, "there's no sense in staying here and getting yourself all worked up. You just come along with me like a sensible girl."

The door opened and O'Regan strode in.

JUST for an instant O'Regan paused, and his glance swept from Perryfeld to Josephine and back to Perryfeld; then he strode in his desk, tossed aside his hat and sat down.

"This is Miss Brady, Chief," said Spellman. "She was at Schnitzer's place last night when the shooting happened."

Josephine glanced up and found a pair of steely-blue eyes surveying her. She tried to smile, but the effort was not much of a success, and her glance wavered and fell. She would have to be terribly careful, she decided, if Captain O'Regan started asking her questions. With those eyes staring at her, it wouldn't be easy to tell a lie and get away with it. Perhaps, after all, it would be wiser to tell him the truth. If only she dared! If only she could pluck up the courage to tell him the truth now, while Perryfeld was there on the spot! She was at Police Headquarters, and was perfectly safe, and she might never have a chance like this again to get out of the tangle. She had only to say, "Captain O'Regan, it was Perryfeld who killed Mr. Schnitzer; I saw him do it," and the whole wretched business would be over and done with.

She took a hesitating step forward, glancing nervously, as she did so, at Perryfeld. He was watching her, with a smile on his face; as their glances met she saw his hand move towards the side pocket of his coat, saw also the ugly look in his eyes, and hesitated. Always a gun not many feet away from her, he had said—even at Police Headquarters. He had got his gun on her now, and if she said one word...

"I'd better be asking Miss Brady a few questions, eh, Chief?" said Lavine. "I guess she can't tell us much, and there's no need to take up your time."

O'Regan glanced at him, frowning.

"I'll question Miss Brady myself," he said shortly. Then, nodding towards Perryfeld: "Who's this?"

"This is Mr. Perryfeld, Chief," said Lavine. "We've been showing him around. He's anxious to meet you—"

"Sure I am," interrupted Perryfeld, smiling genially. "I've heard of you, Captain."

O'Regan's face was unsmiling as he glanced across at him.

"Quite a lot of people in Chester County have," he said.

"I've always been anxious to meet you."

"Quite a lot of people aren't, Mr. Perryfeld."

"I'll tell the world they're not," laughed Perryfeld; "but I'm not one of them. From all I've heard, you're a swell fellow, Captain—"

"Put that testimonial in writing," interrupted O'Regan, "and I'll frame it and hang it in the office." He turned to Spellman. "Show Mr. Perryfeld the way out, Spell, will you?"

"Say, what's the hurry, Captain?" said Perryfeld. "I'd like a bit of a talk with you—"

"You might not. And I'm busy now, anyway. I want to talk to Miss Brady alone."

Spellman went to the door and opened it, but Perryfeld made no move.

"If you've no objection, Captain," he said, "I'd be interested to stay right here and listen. I've never been present at a grilling, and I'd welcome the chance of seeing how it's done."

"Never been grilled yourself, eh, Mr. Perryfeld? Too bad! But keep hoping. You may get your chance one day. Lieutenant Spellman's waiting to shut the door behind you."

"O.K., Captain," replied Perryfeld. "I'll be along again some other day. Glad to have met you."

With a glance at Josephine he followed Spellman out, and Lavine closed the door behind them.

"Miss Brady was at Schnitzer's place last night, Chief," he said again, "but she didn't see—"

"Didn't I say I'd question Miss Brady myself, Lavine?"

"Sure. But I'm just telling you—"

"And I said 'alone'," added O'Regan.

"Oh, all right," said Lavine, with a shrug, and slammed the door behind him.

O'Regan glanced across at Josephine and waved a hand towards the chair on the opposite side of his desk.

"Sit down, Miss Brady, won't you?" he invited.

She went slowly forward and seated herself, aware all the time of the keen scrutiny of O'Regan's eyes. She could not bring herself to look at him. She sat with downcast eyes, her hands clasped together in her lap, dreading the moment when he would speak and she would somehow have to answer him. She felt that it would be useless trying to deceive him, that he would know at once that she was not telling the truth; yet even here, alone with him in his office, she would never dare to tell him the whole truth. Perryfeld's visit just when she was brought to Police Headquarters had not been a coincidence. He had come with some set purpose, and she had not the least doubt as to what his purpose had been. He had not trusted her, and had meant to be there on the spot to see that she kept her promise to him and to carry out his threat if she failed him. He had even tried to stay in the room while she was questioned, and the fact that O'Regan had refused to allow this did not reassure her. Perryfeld was not far away. He would somehow get to know exactly what she told O'Regan, and if she told him the truth she would never be allowed to reach home again. Outside in the street someone would be waiting for her....

"Well, Miss Brady?"

She forced herself to look up, and saw O'Regan smiling at her.

"How are the toes?"

"Toes?"

"The toes I danced on at the Social Club the other evening. Don't tell me you've forgotten."

She smiled.

"No, Captain O'Regan, of course I haven't. I remember perfectly."

"The evil that men do lives after them, eh? I guess I left you plenty of souvenirs. I intended sending you a new pair of dance shoes, but I didn't have your address. When it comes to dancing, sitting-out is my strong point. Not feeling sore with me?"

"Not now," she said.

"But you were?"

She nodded.

"I thought you might have told me that I was dancing with the famous Captain Tricks O'Regan. I had no idea. I only found out when I saw your photograph in the newspaper and recognized you. You said your name was Smith—"

"I did," he admitted. "But when a police officer goes dancing he doesn't advertise his profession. It doesn't pay—professionally. Besides, there's a prejudice amongst young ladies against a policeman's footwork, and he'd get no partners."