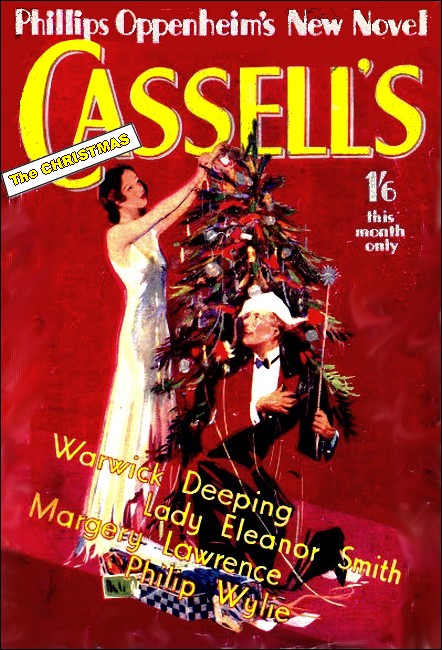

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

"The Ostrekoff Jewels," Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1932

His nostrils were quivering, his expression tense. He was engaged in a paroxysm of strained listening, his head a little on one side, his lips parted, his eyes almost glassy in their stare. A very human Anglo-American voice broke the silence, and the figure of a tall young man, broad-shouldered and powerful, emerged from the nearer of the great suite of rooms beyond.

"Trouble getting worse, Prince?" he asked anxiously.

The latter nodded, as he lowered his revolver and turned towards his questioner. The snapping of the tension brought with it a momentary relief. At least there were no footsteps upon the stairs—the thing he most dreaded—and, outside, the fitful rumbling of artillery seemed to be dying down, the rifle fire becoming more irregular.

"The madmen have won," he announced, with angry bitterness. "The only man who might have saved Russia has preferred to save his own skin. He's in the Baltic by now."

Another voice—there had been people who had called it the most beautiful voice in the world—came from the dim recesses beyond, and Catherine, Princess Ostrekoff, advanced slowly into the room. She was small as the men were large, but her figure was exquisite and her colouring notable. Her large hazel eyes, her golden yellow hair, had destroyed the illusions of a whole school of modern art, and driven more than one great painter crazy with his hopeless efforts at reproduction. For a moment, as she stood on the outskirts of obscurity, she seemed like an exquisite piece of tinted statuary. Her husband's grim face relaxed as he saw her. There were tears in his eyes, not for his own sake, but for hers.

"We have nothing to hope for," he acknowledged solemnly. "The so-called deliverer of the people has deserted us. The butchers are grabbing the power."

"What about the soldiers?" Wilfred Haven, the young American, asked.

"I had to shoot my own sergeant to escape from the barracks," was the terse reply. "They followed me into the street and sent half a dozen bullets after me—the cowards."

"Seems to me you were lucky to get away at all," Wilfred Haven observed.

The Prince shrugged his shoulders hopelessly.

"They are not hurrying," he confided. "Why should they? There is a cordon around the city and they know we cannot escape. They are only staying their hand to be early with the pillaging. They were tearing down the Museum as I passed. To-day Russia is paying for the sins of the world."

Catherine Ostrekoff was as brave a woman as any of her Tartar ancestresses, but she loved life. There were many things upon her conscience and she wished to live.

"Is there nowhere we could hide?" she asked piteously. "Why should this rabble wish for our blood? The Ostrekoffs have always been the friends of the people."

"Of the peasants—not of this scum," her husband reminded her. "Come and look—you can judge for yourselves."

The Prince secured the panelled door which he had been guarding by turning a huge gilded key in the lock, lowered a lamp, leaving the place almost in darkness, and cautiously pulled to one side the curtains covering the nearest of the high windows. He drew his wife tenderly towards him, checking her exclamation of horror with the light touch of his fingers upon her lips. Even Haven, a young New Yorker of a particularly masculine type, gasped as he looked down.

"Why, they're mad!" he cried. "This isn't a revolution—it's a herd of the devil's children broken loose. It's pandemonium!"

"The poison has been festering for generations and the sewer holes are open at last," the Prince muttered savagely. "They're crazy with vodka and brandy, with licence and the lust for blood. Look!"

Two men had met face to face in the middle of the street below. They were apparently strangers, both clad as ordinary wayfarers, except that one wore the short cloak affected by students of the university. Question and answer flashed between them, there was a gleam of uplifted steel, and one of the two, with a terrible shriek, which reached the ears of the three watchers at the window above the spitting of the guns and the dull sullen roar of human voices, threw up his arms and collapsed in a crumpled heap upon the road. His assailant only paused to withdraw his knife, wipe it on the other's clothes and kick the body out of the way. Then he broke into a fantastic dance in the middle of the street—the dance of a trained ballet performer, as he probably was—interpreting, with fiendish precision, in those moments of madness, the bestial passions of life.... Afterwards Wilfred Haven wondered more than once whether a touch of that same madness had not in those moments crept into the Tartar blood of the stern old aristocrat by his side. At any rate, he acted like a man possessed with some silent demon. He dropped on his knees and softly raised the window sash a couple of feet. A stinging blast of cold wind swept into the room. The Prince, for one, felt nothing of it, as cautiously his right hand, with its heavy burden, stole out of the window. He scarcely paused to take aim—in his youth he had been the champion revolver shot of the Russian Army—one single pressure of his finger upon the trigger and the mad career of the fantastic dancer below was over. The song died away on his lips, he spun around once, gripping at the air with frenzied hands, and collapsed even more completely than his late victim. The Prince closed the window.

"Justice has been achieved once to-night, at any rate," he muttered.

"It was well done," the Princess approved.

The three watchers, the Prince and Princess waiting for death, and the young man loath to leave them, lingered still at the window. The dark stream of human beings below were forming into little groups, for safety's sake. They surged here and there in the square and across the street, breaking the windows of many of the houses, and streaming in, to return often in disgust from a mansion which had been already sacked. From one of the lower windows of a tall, narrow house exactly opposite, which had been raided a few minutes before by a shouting and yelling mob, came suddenly a terrifying spectacle. The window was thrown open and a man leaned out, a shrieking woman in his clutches. He mocked at the crowd below, who rushed underneath the window and held out their arms. He shook his head.

"Nitchevo," he shouted. "Be patient, little brothers."

He drew back. The last thing to be seen was the lustful leer of the man as he disappeared. Then the window was closed and the lights went out in the room—the woman still shrieking. Wilfred Haven clenched his fists and turned towards the door.

"My God," he exclaimed, "I can't stand this!"

The Prince gripped his arm.

"Do not be a fool," he enjoined sharply. "You might as well try to save a woman from drowning underneath the falls of Niagara. That is going on in every house in the city—it would take an army to stop it."

"It is going on in every house in the city where the women are cowards enough to stay alive," the Princess observed, gazing contemplatively at the contents of a gold and onyx box which she had drawn from her bag. "It is well that Elisaveta is safe in Florence."

"It is well," the Prince echoed.

In the midst of the turmoil came the chiming of the great clock from the Cathedral. They all listened.

"Eleven," the Prince counted. "My young friend, we must part," he added, laying his hand for a moment upon Haven's shoulder.

The latter felt every fibre of his manhood revolt at the idea of leaving the house. The Princess had sunk into an easy-chair and was delicately touching her lips with the stick from her vanity case. She looked sideways at herself in the mirror. A faint whiff of perfume reached him where he stood. She was cool enough but hers was a very obvious gesture.

"It's damnable, this!" Haven exclaimed passionately. "Look here, Prince, let's try the Embassy. We can get there by the back way, all right, even if we have to sprint across the street."

Ostrekoff shook his head.

"The place is surrounded with spies," he said. "We shouldn't have one chance in a thousand. Besides, all your diplomatic privileges have been withdrawn, except the privilege of unmolested departure for yourselves, and that ends at midnight."

"I can't leave you here," the young man groaned.

The woman laughed at him. She used conversation as a camouflage.

"You must," she insisted. "You are undertaking a marvellous task for us, as it is. I am afraid that you will have to face death many a time before it is over. As for us—Michael is a soldier, and I shall escape the ignominy of seeing the admirers of my youth slip into obscurity with the coming of the wrinkles. A Russian or a Frenchwoman, you know, my dear Wilfred, without an admirer, is a woman upon whom the sun has ceased to shine. Michael," she went on, turning to her husband, "take our young friend down to one of the back doors. He would lose himself in this prison. Remember, Wilfred," she added, turning back to him, "you will be a marked man all the way across Europe. As soon as they discover that the jewels have been taken from the bank, they will guess that it is you who have them. They are everything that is left. They will be Elisaveta's sole fortune. You will find her very beautiful and she has a wonderful character. If you succeed, you will deserve whatever she may choose to give you, and if she gives you what I hope, it will be with my blessing. Now I am going to rest for a time."

She held out both hands with an imperious gesture. He bent low and raised them to his lips, but he had not altogether concealed the moisture in his eyes.

"What a lover you will make, my dear Wilfred," she laughed, as she drew away. "You have the sensibility which our Russian men too often lack. See, I make you the mystic sign of the Tartars, the sign of the woman who sends her man to battle, the sign which she may make only to son or husband. It should take you safely to England."

Her beautiful white hand, the fingers of which were laden with the jewels which she had scorned to remove, flashed through the shadows up and down in strange circles and tangents. It finished with a final sweep, outstretched, firm and resolute—and it pointed towards the door.

The Prince led his young friend down the vast staircase almost in silence. The same thought was present in the minds of both of them. For generations this smooth marble surface had been pressed by the feet of queens and princesses, kings and ambassadors, the flower of the world's aristocracy. Now the whole place seemed abysmally empty, the stairs themselves slippery with dust, disfigured by the foul relics of an army of raiders with whom had departed practically the whole of the domestic staff. They passed through a labyrinth of passages, unheated, unlit, dank and mysterious. There were rooms full of broken furniture and china, a great kitchen with the remains of a carouse still littering in unsavoury disorder the large table. They came at last to a huge oaken door. The Prince paused before it.

"You have only to cross the street from here," he pointed out, "and you are at the Embassy.... Wilfred," he added, looking into the other's rugged but sensitive face, "both Catherine and I have grown very fond of you during these last few years. I cannot help feeling, however, that we are asking too much. You are not of our country and these are not your troubles. You will risk your life many times, I fear, before you find Elisaveta."

"If I do, what does it matter?" the young man protested light-heartedly. "I think you exaggerate the danger, sir. I do really. I have an Embassy bag, sealed with the good old U.S. stamp—I guess they won't interfere with that—waiting for me in a corner of the Embassy safe. And as for the chamois belt, they'll have to take my clothes away before they find that. I shall get away with them before midnight and when I am once across the frontier I should like to know who's going to interfere with us."

"Do your people know what is inside that belt and the Embassy bag?" the Prince asked.

Wilfred Haven coughed.

"There's no one left to trouble about such things," he explained. "Old Hayes, the Counsellor, is nominally in charge, and he's nothing to do with the diplomatic side of affairs at all. The others are juniors like me, only more so."

"Still, you know, if this comes out, you may be in trouble with your own people," the Prince reminded him wistfully. "It is an absolute contravention of diplomatic usage."

"What can that matter against such a mob as this?" the other scoffed. "Besides, I shall own up and resign as soon as we are safe. I was going to do that, anyway. I want to get into the war. I've had enough of diplomacy."

"You mean that?"

"Word of honour," was the terse but fervent reply.

There was an expression of great relief on Ostrekoff's worn face.

"You have taken a load off my mind," he confessed. "It would be very distressing, both to Catherine and me, if we thought that we had saved the fortunes of our house at the expense of your career."

"You don't need to worry," the young man assured him. "I'm going to be a soldier for the rest of the war, and after that—a banker for the remainder of my life."

The Prince smiled.

"Perhaps it was foolish ever to have imagined otherwise," he said, "when one remembers your father's amazing achievements. I do not wish you, however, Wilfred, to take your enterprise too lightly. If your train, for instance, is in any way delayed, and the news gets out that the Ostrekoff jewels have left Russia, you may find it exceedingly difficult to cross the frontier."

Haven smiled confidently.

"I'll get across, all right," he declared.

"Even when you have succeeded so far as that," Ostrekoff warned him, "remember that the jewels you are carrying are famous in every country of the world. To-morrow, when the bank is seized, as I know it will be, and they realise that the jewels are missing, there will be a hue and cry—not over all Russia but over all Europe. Every likely person who has left the country lately will be followed and watched."

"You don't need to worry for one moment," Wilfred Haven persisted. "The Embassy seals will get us over the frontier, and after that the thing's easy."

"Elisaveta's address is in the letter with the jewels," the Prince reminded him. "She is a very bad correspondent, I'm sorry to say, but the last time we heard from her she was in a studio in Florence. You will also find the address of her London bankers."

"There's only one thing that bothers me at all," Wilfred Haven remarked, after a moment's anxious pause. "Won't it make it all the worse for you and the Princess when they find that the jewels are gone?"

The Prince unbarred the door. The grip of his fingers brought tears to the eyes of his departing visitor.

"Nothing can make the position worse for either of us," was the grave reply. "I know that our death warrants were signed this afternoon. They will come for us when they have time. What they will find, however, will be our bodies. That is arranged."

Fifty yards down a side street, dominated by the gigantic, encircling wall of the Ostrekoff Palace, followed by one dash across the broader thoroughfare, and Wilfred Haven would have reached the comparative sanctity of the Embassy and his own quarters. He strode along at a rapid pace, his hands in his overcoat pockets, his hat pushed back on his head as though to disclose his Saxon nationality, his eyes everywhere on the lookout for danger. Ahead of him, the sky was red with the reflection of a hundred fires, the air he breathed was rank with the smell of burning wood and masonry. In the not very far distance, unseen men and women were screaming and shouting—a constant wave of discordant sound like the baying of an innumerable pack of hellhounds. He shivered as he pushed onwards, desperately anxious to escape from the hideous clamour. The rioting had been in progress for almost a week, but the horrors seemed to grow rather than lessen. Then, in the middle of the boulevard, within sight of his destination, he was brought to a sudden standstill. The blood seemed to rush to his head. Opposite to him was the tall, narrow house with the flaming windows, and from behind the lower one, where the lights had been extinguished, came floating out once more half-stifled moans of agony and appeal, the cry of that still tortured woman....

The broad boulevard, in the centre of which he stood and up and down which he glanced now with quick apprehension, was temporarily deserted. Every one seemed to have travelled southwards to where the skies grew redder every moment, whence came now long wafts of hot air and the increasing roar of voices. Every instinct of Haven's nature rejected and discarded those cautionary whispers of his brain. He traversed the remainder of the boulevard in a dozen strides. He sprang across the paved yard, mounted the steep flight of steps, and pushed his way past the front door, which had been half torn from its hinges and lay at a perilous angle upon its side. Here, in the main hall of the house, he paused for a moment, breathless. All around him were evidences of wild pillage. From the upper rooms came the clamour of shouting, drunken voices, the smashing of glasses, disorder and riot rampant, a nightmare of furious licence. A paralysing indecision tortured Wilfred Haven in those few moments. Once more his brain had begun to work. He was pledged to a great and dangerous undertaking. What right had he to imperil his faint chance of success by plunging into a fresh adventure? Ostrekoff had spoken the truth. There were a thousand women being maltreated that night. A torrent of human madness and brutality was flowing which no human being could stem. The perilous mission to which he was already committed was full enough of danger and romance for any man. Already from upstairs came the sound of the banging of doors. At any moment the mob might come sweeping down. No one man could stand up against it, and his life, for as much as it was worth, was pledged. Reluctantly he turned away. He had even taken a single step towards the street when, from the room on his right, only a few yards distant, came that same pitiful, irresistible cry for help, weaker now and fainter with a pitiful despair. Hesitation after that was no longer possible. He flung open the tottering door and pushed his way inside.

It was a scene of wild confusion into which he stepped—a bourgeois-looking dining room it might have been, or the salle à manger of a pension. There were bottles, mostly empty, and glasses, mostly broken, upon a heavy sideboard which took up one wall of the apartment. In its centre was a long table laden with more empty bottles, plates and debris of various kinds, and—most tragical sight of all—in the far corner, nearer to the window, a girl, bound with stout cords to a heavy easy-chair. Her dark, almost black hair had become disordered as though in a struggle and there was a long stain of blood on her face. Her cheeks were ghastly pale, her already red-rimmed eyes were flaming with terror. Her once fashionable grey dress was torn and dishevelled. There was blood on her finger tips where she had been plucking at the cords.

"Brutes!" he cried. "Don't struggle. I'll have you out of that in a moment."

He added a word of reassurance in Russian whilst he searched his pockets for a knife. To his amazement she answered him, chokingly, but in unmistakable English.

"A knife? There, by the sideboard—hurry."

He followed the slight movement of her head. A rudely fashioned peasant's knife lay amongst the bottles, already wet and suggestively stained. He picked it up and, falling on his knees, hacked at the cords which bound her. All the time the pandemonium upstairs ebbed and flowed as the doors were opened or closed. The girl was free now from her shoulders to her waist. She had fallen a little on one side and was evidently struggling against unconsciousness. He attacked the thicker cord that bound her knees. Suddenly they heard the dreaded sound—heavy, stumbling footsteps on the stairs. Whoever she was, he thought afterwards, it must have been a fine impulse which prompted her whisper.

"Better go," she faltered. "The house is full of them—they will kill you."

He laughed scornfully. Life and death during those last few moments seemed to have lost their full significance. One more twist of the knife and she was free. He stood up. She too staggered to her feet, but at her first attempt sank back into the chair. Nevertheless, she was standing once more by his side when he turned to face the owner of the footsteps. The latter came blundering into the room, true to type, a large bestial-looking man, his cheeks flushed with drink, his eyes hungry with lust. He stopped short by the table, shouting and yelling wild Russian oaths, a whole string of them, as he saw the girl free from her bondage and Haven by her side. The latter acted on an inspiration that served him well. He wasted no breath in words, but, when he saw the newcomer's long hairy fingers groping towards his belt, he rushed in before he could reach his knife, struck up the hand with his right fist and got home with his left upon the chin. The man was of sturdy build, however, and although he was momentarily staggered, he held his ground and persisted in his efforts to reach his knife. Haven, ducking low, ran in once more, hit him under the jaw this time and sent his victim crashing into a pile of broken furniture.

"Come on," he shouted to the girl. "Here, I'll help you."

He passed an arm round her waist and drew her into the passage.

"Pull yourself together if you can," he implored. "They're coming down the upper stairs now. If they see us, heaven knows how we shall get away. We've only a few steps to go if you can stick it out."

She drew a long breath and one could almost see the nerves of her body quivering with the effort she was making as she struggled towards recovery. With the great smear of blood down one cheek, her torn clothes and swollen wrists, she was a veritable figure of tragedy.

"I am all right," she gasped. "Let us—get out of this filthy house. The air of the street will revive me."

They made their way, stumbling, down the passage and over the fallen front door, his heart sinking all the time at their slow progress. Then the terror broke upon them. Behind, the stairs creaked and groaned with the weight of the howling mob which had turned the corner and come suddenly into view. They had found drink, and they had found booty of a sort, but they wanted the girl. The place rang with their clamour. Some one had lit a torch and they realised that it was a stranger who was stealing off with her. They pushed one another so madly that the banisters gave way, and a dozen of them crashed on to the hard floor. One or two of them lay still, but the others picked themselves up and joined in the onward rush. Haven knowing enough Russian to apprehend the fury behind, pushed his companion impetuously towards the steps.

"Listen," he begged breathlessly, "turn to the left here—up the boulevard, you understand. Twenty yards only and then again to the left. Fifty yards down the street and there's an iron gate—back way to the American Embassy. Hide there in the garden till I come."

"And if you do not come?" she faltered.

He dodged a burning fragment of the banisters which fell at his feet, sending a shower of sparks into the air, and held up his arm to protect her from the stream of missiles beginning to come.

"If I don't come, it'll be because a dead man couldn't help, anyway," he rejoined swiftly. "You must bang at the doors then and perhaps they'll let you in. If you want to help me now—run."

She obeyed him, although her knees were trembling and her limbs quivering with fear. She tottered down the paved way towards the street, where the darkness hid her almost at once from sight. She became part of the gloom, a shadowy lost figure, staggering into obscurity....

Haven faced the angry crowd, now within a few yards of him.

"Get back, my friends," he shouted in Russian. "I am an American and I am not worth following. The girl is English. It pays to leave us alone."

They answered with a chorus of jeers and began to move stealthily towards him. A constant shower of missiles thrown by drunken hands he easily avoided, but a leaden weight, thrown by a man who seemed to be a blacksmith, passed within a few inches of his head and crashed into a dwarf lime tree. From the rear, a youth came running out of the room on the ground floor, shouting that Navokan, the shoemaker, who was to have had first converse with the girl, lay dead. There was a rumble of angry voices. Haven called to them again, seeking for peace, but no one wanted a parley. They wanted blood. They were stealing around him, those dark figures, and he knew that, if once he suffered himself to be surrounded, their fingers would be tearing at his throat. With a groan he drew the automatic pistol, which he had never yet discharged except at practice, from his pocket. He came of a Quaker family, but he had been brought up in manly fashion enough, though hating bloodshed. He stepped farther back, all the time gaining ground. He was almost in the road now. A piece of burning wood grazed his leg. He kicked it away, ignoring the pain.

"Don't you hear me, little brothers?" he cried. "Why should we fight—you and I? There are plenty of other women in the city—women of your own race too—whose arms are open for you."

No one took the slightest notice of his appeal. The missiles were coming faster—accompanied by a stream of oaths and terrible threats. They wanted the blood of this young man. They meant having it, and tearing his body to pieces afterwards. One of them, who had almost the appearance of a monk, in his long toga-like cloak, a giant brandishing a torch in one hand and a great knotted stick in the other, came blundering forward. He whirled the stick above his head ferociously and they all cheered him on. Wilfred Haven set his teeth. This was the end then. He shot his would-be aggressor through the chest, just as the blow was about to descend, never doubting but that the rest of them would be upon him like a pack of mad dogs as soon as they saw their leader fall. The effect of the shot, however, was in its way astounding. The man, who had felt the hot stab in his chest, stopped short and swayed upon his feet. A look of wild, almost pathetic surprise chased even the wolflike bestiality from his face. He staggered and fell face forward, rolled over once and lay quite still. Retreating slowly, Haven kept his gun outstretched, meaning to gain time for the girl and to sell his own life as dearly as possible. For the moment, however, a miracle seemed to have happened. He was completely ignored. The savage-looking mob seemed to have forgotten their lust for blood and pillage; they were gathered around the body of the dead man, weeping and lamenting like children. Every moment, Haven's eyes opened wider in amazement. Then he realised his good fortune and fled....

Incredible though it appeared to him, he passed out of the gate and along the boulevard without a single pursuer. A few yards down the cross street he caught up with the girl leaning against the high railings and partly unconscious. She tottered towards him and he half carried, half dragged her through the gate he had indicated, into the gardens. Inside, and behind the shadow of some shrubs, he paused for a moment to listen. The tumult in the centre of the city continued unabated, but nearer at hand everything seemed peaceful. He led her along a gravel path towards a formidable-looking door which he opened with a Yale key. As soon as they were both inside, he slammed and bolted it. For a time, at any rate, they were in safety.

"Well, what do you know about that?" he demanded of no one in particular as he leaned against the wall, recovering his breath.

She sank on to a divan with a little sob of relief. With one hand she pressed a fragment of torn handkerchief to her eyes; the other sought weakly for his. Wilfred Haven, who was not in the least used to holding a girl's hand, patted it awkwardly.

"Come, that's fine!" he exclaimed, drawing off his overcoat. "We're out of our troubles for the present, at any rate. I'll get you some tea or brandy in a few minutes and we'll decide what we can do for you."

Her eyes sought his, eyes of a wonderful deep blue, almost violet, eyes that were pathetically eloquent with gratitude.

"You have been wonderful," she told him. "Holy Maria, what I should have done without you!"

"That's all right," he declared hurriedly. "Somebody else would have chanced along, I expect. I say, you're in rather a mess," he went on, looking at her ruefully. "We haven't a woman in the house and I'm afraid most of the rooms upstairs are dismantled."

"If I could wash—"

He threw open the door of a large old-fashioned lavatory and bathroom opposite.

"No one uses this place," he told her. "Lock yourself in and I'll come and fetch you in twenty minutes' time. We're in a terrible muddle here because we're clearing out to-night, but the Russian servants always keep some tea going and there's plenty of wine or brandy. I'm going to leg it upstairs and get a drink myself, as fast as I can."

She smiled at him—a somewhat distorted gesture. Notwithstanding her ruined clothes and generally dishevelled appearance, there was no doubt about her beauty.

"I shall take anything that you give me, but do not be longer than twenty minutes, please," she begged, with a faint shiver. "Before you go, will you promise me something?"

"Well?"

"You spoke of clearing out. You are going away. You will not leave me in this city?"

He looked at her, thunderstruck. The possible consequence of his act of chivalry occurred to him for the first time.

"But—but, my dear young lady," he pointed out, "don't you understand we're quitting? We're off across the frontier to-night—unless they change their minds and throw us into prison instead."

She smiled at him once more through the closing door and this time it was by no means a distorted gesture.

"Across the frontier," she confided, "is just where I want to go."

Without a doubt the most thrilling moment of that hectic and amazing journey out of Russia arrived when Walter Pearson, a youth of twenty-two and the junior member of the Counsellor's staff, suddenly drew back from his place, half out of the window, and made a portentous announcement. He pointed to the line of lights in the distance towards which the train was lumbering.

"The frontier!"

John Hayes, the Counsellor and senior member of the little party, who was smoking a long cigar, was apparently the least interested. Rastall, the third secretary, the whole of whose personal belongings had been looted at the railway station before leaving, was still searching for fresh oaths and remained entirely indifferent. Wilfred Haven, who was conscious of the warm pressure of a chamois leather belt around his waist, and to whose left wrist was attached, by means of a chain, the Embassy bag by his side, shivered with excitement as he realised that the actual commencement of his great adventure was close at hand. What the girl felt was not easily discerned, but there was a vague shadow of apprehension in her eyes. She drew nearer to her companion.

"This is a terrible journey," she murmured. "If only we were safe on the other side!"

"I shouldn't worry," he answered reassuringly. "They aren't likely to turn you back. You've even got your passport, which is more than I expected."

"Passports are all very well for you," she said, "because you are foreigners and your passports have the diplomatic visas. The Russia even of these days, dare not offend you."

The Counsellor withdrew his cigar from his lips. He had been in a state of silent but simmering indignation for the last two hours.

"Well, I don't know, young lady," he objected. "I should say they'd done their best to get our backs up. Three hours we sat in this cattle truck before they let us start. Nothing to eat or drink upon the train, or anywhere else that I can discover, except what we brought ourselves. No sleeping accommodation, and one of the foulest crowds of fellow passengers I've ever seen in my life. My back's up already. I can tell you that. If ever this country gets a government again, she'll hear something from us. We may be running it rather fine, for we're the fag end of the show, but we've all got diplomatic passports and they don't call for this sort of treatment."

The girl sighed. She was wearing a neat, but shabby black dress and a worn fur coat, discarded garments of one of the Embassy typists. The only head covering they had been able to procure for her, however, was a boy's black beret, under which she seemed paler than ever. Her eyes were fixed almost in terror on that encircling row of twinkling lights.

"So long as they let us pass," she murmured. "Any country in the world, but never again Russia!"

"I think you'll find they'll be glad enough to get rid of us," Haven assured her. "If they're going on as they've begun, they won't want foreigners around."

The long train rumbled over a bridge, which was apparently in course of repair, and almost immediately came to a standstill. They were in what appeared to be a temporary station—a long shedlike building with a rude platform. A blaze of lights about a quarter of a mile farther down the line seemed to indicate the real whereabouts of the depot.

"What the mischief is this place?" John Hayes growled.

Haven let down the window to look out, but the rain had turned to sleet, and an icy wind set them all shivering. He pulled it promptly up again.

"Can't see anything anyhow," he announced. "No good worrying. Let's wait and see what happens."

On the other side of them, the outside corridor was thronged with a motley crowd of men and women of probably every nationality and class in the world, who passed up and down slowly and with infinite trouble, like dumb, suffering animals. Here and there was a person of better type, but upon the countenance of every one of them was the same expression of mute and expectant terror. They pressed white faces against the windows of the compartment, looking in with envy at the comparative comfort in which Wilfred Haven and his companions were seated. One or two even tried the handle of the locked door. The whole place seemed to be at their mercy, for there was apparently no train attendant nor any guard. Yet on the whole, except for a couple of fights amongst themselves, which amounted to little more than scuffles, they behaved in orderly enough fashion.

An hour passed without any sign of movement. Suddenly there was a stir. Every one in the corridor crowded backwards. From the lower end of the car came the sound of loud voices and heavy footsteps. The girl shivered.

"There's nothing to be afraid of," Haven whispered. "These men, after all, have a certain amount of authority. The sooner we get it over the better."

The footsteps and voices reached the next compartment. Presently there was a disturbance. The outside carriage door, opening on to the platform, was thrown open. They all gathered around the windows, and a shiver went through them. A small, thin man, with a mass of blond hair and a look of despair upon his face, was being led away, handcuffed, by one of the station police. A woman, left behind, was shrieking from the train window. The girl leaned back in her place and closed her eyes.

"I wonder more people do not go mad these days," she murmured.

Their own time had arrived. A man in some sort of a military uniform, with a red sash around it, stood over a station attendant whilst he unlocked their door. The mob of people had crept away from the corridor. In the background were two soldiers with rifles.

"Passports," the officer demanded.

Counsellor John Hayes, as became his position, took command of the situation.

"We are the last of the staff of the American Embassy in Petrograd," he announced. "Here is my passport. I am official Counsellor in Chief. One of these young men is my assistant, the other two are junior secretaries, the young woman is an English typist."

The man glanced casually at the passports and handed them back.

"What have you in those satchels?" he enquired, pointing to the Embassy bags, of which there were two others besides the one chained to Haven's wrist.

"Official papers belonging to the American Government," Hayes replied.

"You are not allowed to carry documents of any sort from the country," the official declared. "They must be sent in for inspection to the commandant."

"The documents we are carrying cannot be disturbed," John Hayes insisted. "The bags are sealed with the official stamp of the American Government, which is guaranteed immunity."

"Of that I am not sure," was the harsh rejoinder. "The Russia of to-day is a new country. We do not need foreigners here and you are welcome to go, but what you carry with you is another matter."

"Whatever form your new government may take," Hayes pointed out, "it would surely be folly to start by making an enemy of the United States."

The officer spat upon the floor. The gesture seemed to express his contempt for the United States and all other foreign countries.

"Your passports are in order," he conceded. "You are free to leave the country and stay out of it. As for your bags, however, that is different. All luggage must be examined."

"You can tell your superiors that we claim diplomatic privileges," Hayes directed a little pompously.

"Who cares what you claim?" was the scornful reply. "Those days have gone by. I shall report the presence of the bags. They will probably be confiscated."

He turned his back upon them. The two soldiers shouldered their rifles and the cavalcade moved on, the station attendant having locked the door. Hayes, with a twinkle in his eyes, pulled down the curtains and opened the bag nearest to him.

"In case of confiscation," he announced, "here are two bottles of the best Embassy champagne, ham and bread. The greater part of our troubles being over, I say—let's celebrate! What have you got in your bag, Wilfred?"

Wilfred Haven, with about three million pounds' worth of Ostrekoff jewels chained to his wrist and slung around his waist, hesitated for a moment before he answered.

"Nothing so sensible as you, sir."

Hayes was already cutting the ham, Pearson was twisting the wire of a champagne bottle. There was a gleam almost of greed in their faces. The cork popped and the glasses were filled. Hayes busied himself by laying slices of ham upon the bread. The girl whispered in Haven's ear.

"Tell me what you have in your bag."

He laughed at her, recovered as though by magic from his depression and fatigue. The tingle of the wine was in his throat, the golden sparkle of it was exhilarating; through all his veins the warm blood seemed to be flowing with a new vigour. He handed back the glass which he had emptied and Hayes replenished it.

"My love letters," he confided.

She made no comment. Her eyes studied the outline of the bag and a faint, incredulous smile parted her lips. Then she drank her wine, and, for the first time, a shade of colour crept into her cheeks.

"Well, that's done you good, anyway, young lady," the Counsellor remarked graciously. "By the by, I haven't heard your name yet."

"My name is Anna Kastellane," she confided.

He handed her over a carefully made sandwich.

"Now let's see what you can do to that, Miss Kastellane," he said.

She took it between her slim, delicate fingers and bit into it with an appetite which was near enough to voracity. She kept her back to the one uncovered window, turning away with a shudder from the sight of the white faces pressed against it. Hayes nodded sympathetically.

"There's nothing we can do about them, I'm afraid," he regretted. "I should say there were a thousand people upon this train—most of them hungry and thirsty—and the first station we come to, where there's any food, they'll wreck the place and get it. We shouldn't stand a chance. Besides, we're tightly locked in. If we wanted to give them anything, we'd have to wait till the doors were opened."

"I am hoping," Wilfred Haven said fervently, "that next time they are unlocked, we shall be free of this accursed country."

The girl ate her sandwich to the last crumb and drained the contents of her glass. Despite all her efforts, her eyes kept wandering towards the bag. She was watching the bulge as though fascinated. Haven could almost have fancied that through the worn leather she could see its dazzling contents.

"So many women have written you letters?" she reflected. "I am sorry."

He laughed light-heartedly.

"I've been in St. Petersburg for three years," he reminded her.

"They are all from one woman?" she persisted.

He passed up her glass to be refilled and offered her another sandwich.

"I will tell you their history," he promised, "the first night we drink a glass of wine together in a neutral country."

With groaning and creaking and jerking of couplings, which sent every one momentarily off his balance, the long train started again on its crawl westward. Walter Pearson, who was aching to see a game of football or baseball, and to whom the ladies and cafés of Petrograd had made no appeal compared with the glamour of Broadway, rose to his feet and waved his glass.

"Here's a long farewell to the foulest country on the earth," he cried.

The Counsellor, who had been looking out of the window, resumed his seat.

"A little premature, young man," he remarked. "That's only a temporary station we've been in—kind of rehearsal for the real thing. The frontier is on the other side of that great semicircle of lights."

Wilfred Haven groaned. The blow fell heavier upon him than upon his fellow worker.

"Are you sure about that, sir?" he asked eagerly. "Those two men certainly belonged to the customs and there was no doubt about the passport officer."

"Positive," was the uncompromising reply. "I've done this journey a great deal oftener than you youngsters, and I can assure you that we're still on Russian soil. When you hear the whistle blow and we leave the next station, you can shout yourselves hoarse."

Haven seemed to have lost his appetite. He laid down his roll and took a long gulp of the wine. The girl by his side watched him curiously.

"Why are you so anxious about the customs?" she teased him. "Love letters are not dutiable."

"I'm not afraid of the ordinary customs," he explained irritably. "The trouble of it is that the Russians are examining all outward-bound luggage and confiscating anything to which they take a fancy. My letters might be the commencement of a great scandal."

"Then this should certainly be a lesson to you," she admonished. "All love letters should be destroyed. Your behaviour to-night is teaching me a lesson. You shall not receive any love letters from me!"

He made no comment and she abandoned the subject, leaning back in her seat and drawing a little away from him. Nevertheless, even in her new position, she seldom took her eyes from the bag which was still chained to his wrist. Haven seemed to have forgotten her very existence. His eyes were fixed upon that growing semicircle of lights. Apprehension was fastening itself upon him. There seemed something sinister in their slow progress towards the station, the curved roof of which was already in view from the window. The attitude of the officials who had recently visited them was in itself disturbing. Law, order, etiquette, diplomatic privileges—none of these things, he felt, counted for a rap in this new world, which was being born in travail and with bloodshed. Violence was the only weapon its inhabitants understood or cared to understand.

Inside the covered station, pandemonium seemed to have merged into bedlam. People were all jammed together, struggling even for breathing room. The train crawled along by the side of the platform until they were almost out of the station again. Then, with the same series of convulsive jerks, it came to a standstill. They gazed out of the window at the seething mob in consternation.

"Where do they come from, these crowds, and where are they going to?" the girl cried.

No one knew. They might have been exiles trying to get back to join in the political cataclysm. They might have been refugees arrived so far and anxious to continue their journey. Men and women, old and young, children and invalids, they were herded together under the low-hanging oil lamps, some of them talking fiercely, others in stolid, suffering silence.

"Say, look at the three musketeers!" Walter Pearson called out.

They gazed in astonishment at the three gigantic figures who towered head and shoulders above the mob which surged around them. They wore long, semi-military overcoats, Cossack turbans and high boots clotted thickly with snow and mud, as though they had recently arrived from a journey. All the time it seemed to Wilfred as though by slow but powerful pressure they were drawing nearer to the railway carriage.

The attention of the little party was suddenly distracted. The officer who had entered their carriage at the last stopping place presented himself again, followed by one of the soldiers. There was a malicious grin upon his face.

"Open all bags," he ordered.

"I claim diplomatic privilege on behalf of myself and party," John Hayes declared. "The bags of which I am in charge contain only articles of no value, or Embassy papers with which I am not permitted to part."

The officer raised a whistle to his lips. The sound of groaning and shrieking came from the corridor as the advancing soldiers forced their way through the crowd.

"The Government of Russia recognises no diplomatic privileges," he insisted. "Your bags will be taken from you by force unless you open them."

The Counsellor shrugged his shoulders. All papers of importance had either been destroyed within the last few days or sent home a month before. One by one he unlocked his bags. They contained nothing but packets of worthless papers or articles of clothing and food.

"Do what you like with the rest of the things," he grumbled, "but if you take our food—especially that ham—it will mean war."

The official pushed the bags and their contents away from him contemptuously. He pointed to the satchel chained to Haven's wrist.

"Unlock that," he ordered.

Haven rose to his feet. His right fist was clenched and there was murder in his eyes. To fail so soon in his enterprise! It was incredible.

"I'll be damned if I do," he answered.

The official held up his hand and two of the soldiers pushed their way unceremoniously into the carriage. Haven looked at the naked points of their bayonets and made a rapid calculation. The situation seemed hopeless.

"The contents of this bag are not my property," he declared. "I have promised to defend them with my life and I shall do so. You can murder an American official, if you think it worth while," he added. "You'll get all the trouble that's coming to you in this world before any one has a chance of dealing with me. It's hell for the three of you, I say," he shouted in Russian.

His right hand jerked out of his overcoat pocket. With his elbow doubled into his side and his automatic held in a steady grip he stood for a brief period of madness, his finger upon the trigger, the gleaming barrel not more than a couple of yards from the Russian officer's heart.

"Don't be a fool," Hayes thundered out. "Are you mad, Haven?"

At that moment and during the moments that followed, Wilfred Haven certainly thought that madness had enveloped him and that he had passed into the world of oblivion. What had happened wasn't possible. They must have killed him and this was the nightmare of resurrection. Nothing that had taken place was possible and yet there he was. The outside door of the compartment, against which he planted his back, had suddenly been opened, and he had fallen into the grasp of two of the huge men whom they had seen battling their way through the mass of people. He was between them now, their hairy overcoats pressed against him, the weight of their bodies all the time forcing him on. In front was the third man, swinging his arms to right and to left, clearing a way for him through that surging mass of humanity. A hundred pairs of curious eyes seemed to be looking at him with indifferent wonder. No one appeared to be greatly disturbed by the fact that this young foreigner was being dragged through their midst by three officials who were probably conducting him to the nearest wall. They gave way where they could and fell upon their neighbours with groans when they were pushed on one side. From the waiting train behind came a confused sound of shouting and over their heads the bullets whistled. A not unpleasant sense of impotence crept over him. He was entirely powerless, ready to accept what fate might come. His fingers were locked like mechanical things of steel around the handle of the bag which was still under his arm. He had concentrated so completely upon it that to him it was the only thing in life. He had long ago ceased his first struggles and was now even assisting his own progress. In the clutch of his captors, he passed through the great overheated waiting room, the doors of which were lying flat on the floor. Once under the outside shelter, they all four, Haven included, broke into a run and issued directly into the huge snow and wind-swept yard which, compared with the thronged station itself, was almost deserted. Exactly opposite the door a large automobile was waiting with flaring lights. Haven, notwithstanding his great strength, was literally thrown inside. Two of his three guardians mounted with him into the interior, the third took his place by the side of the immovable chauffeur, who appeared to be merely a mass of furs. In a few seconds they were off, bumping across the yard, out of the iron gates. They turned their backs upon the lights of the town and plunged into what seemed to be a long, evil-looking road, leading into impenetrable gloom. Haven, with the bag under his arm, and the snowflakes which drifted in through the half-opened window stinging his cheeks with their icy coldness, found breath at last to speak.

"Where the hell are you taking me?" he demanded.

The man opposite to him shook his head. The one by his side, however, answered at once in correct but guttural English.

"We are obeying orders," he announced. "There will be no danger for a quarter of an hour. American gentleman had better take a drink of this."

He produced a huge flask and filled a small silver cup full of brandy. Haven drank it to the last drop. After all, he could never be in a worse mess than he had been in on the railway train. The bag was still under his arm and neither of his two companions appeared to feel any curiosity concerning it.

"You are a brave man?" his neighbour asked.

"I don't think I am a coward."

The other was loosening his overcoat.

"Then rest tranquilly for a few minutes," he advised. "Rest is always good."

Haven leaned back in his seat and drew a long breath of relief. Somehow, his two companions, terrifying though they were externally, imbued him with a sense of confidence. He was beginning to feel a man again. The bag was there, still chained to his wrist. His fully charged automatic remained safely in his pocket. He could feel the warmth of the belt with every breath he drew. They were travelling at thirty or forty miles an hour across a great plain, a drear enough region in the daytime, he imagined, a black chaos now, with occasional pin pricks of light.

"Look out of the window ahead," his companion invited.

He obeyed, although the snowflakes stung his cheeks and the icy wind nearly sucked away his breath. Far away down the straight road, several miles ahead, was a huge electric-light standard, the unshaded globe of which was like a ball of white fire.

"Do you see the light?"

"I should be blind if I didn't."

"The frontier."

"Which way?" Haven asked quickly. "I don't know where we are. You can't mean that we shall be back in Russia."

The man by his side shook his head.

"No," he confided, "it will be Poland. Where the light flares, it is the end of Russian territory. There we shall be stopped for what we take out of the country. Just beyond, where the red light shines, are the Polish customs. Both are very dangerous to us."

"No way round, I suppose?"

"There is no way round," was the uncompromising reply. "The country for many miles here is a marsh. Under the lights are sentinels. The Russians will fire at us, we shall fire back at them. From the Poles, we have not, I think, so much to fear. They can use the telephone and have us stopped farther on in the country—if they can find out where we're going."

"By the by, where are we going?" Haven enquired.

His companion ignored his question. He had produced an automatic twice the size of Haven's and was crouching by the window, ready to open it.

"You have a gun," he muttered. "I felt it."

"Yes, I have a gun," Haven admitted. "I'm not sure whether I could hit much going at this pace."

"Keep in the bottom of the car. You take my place or Ivan's if we are wounded."

"I wish to God you'd tell me who you are and where we're going," Haven complained. "All the same, I'll take a chance."

They seemed to be nearing, if not a town, some sort of a settlement. The lights flashed past them. Suddenly they came within the arc of that great white circle of illumination. Haven caught a glimpse of men tumbling out in huge overcoats from a square white stone building at the side of the road. There was a challenge, unanswered—a shout—a shot—then a fusillade of shots. The side windows of the car were smashed to pieces and Haven felt his cheek cut by one of the flying fragments. All the time their own automatics were barking out. There was the swish of a bullet through both windows of the car, piercing the astrakhan turban of one of the kneeling men.... They were outside the circle of the white light now, travelling at a tremendous pace, swaying from side to side of the road, surrounded by a perfect tornado of snow thrown up by the wheels. The bullets from behind were coming more scantily. A single challenge reached them from underneath the red light. The men in the car withheld their fire and passed safely.

"Are either of the two in front hit?" Haven asked breathlessly.

His immediate companion let down the window and talked to the chauffeur for a moment. When he drew back there was a look of relief upon his heavy inexpressive features.

"It is good news," he announced. "Neither of them are touched. In a quarter of an hour we leave the main road. Once we have done that, no one will find us."

Haven lit a cigarette and addressed himself to his English-speaking friend.

"Now look here," he began firmly, "you're giving me a jolly good run for my money and I must admit that you got me out of a nasty hole at the railway depot, but who are you? How do you come to be mixed up in my affairs? For whom are you doing this?"

The man by his side was unexpectedly solemn. He lifted his hand in a salute. His companion, as though automatically, followed his example.

"We are Ostrekoff men," the former confided. "Three brothers. Alexis is my name, Ivan there, Paul outside. We have formed the bodyguard of His Highness since he became Chief of the Imperial Household. Before that we were rangers here on His Highness' estates in Poland and down in Georgia. Those days are over. Russia is a lost country. This is the last time we work for our master."

Haven felt a new and delightful sense of security. But for the dignity and aloofness of their own manners, he could have almost embraced his three companions.

"And where are you taking me now?" he asked.

Alexis suddenly sprang up, threw down the window and looked out. He talked rapidly to the driver and their speed diminished. Presently they turned abruptly to the right, continued for about a mile along a villainous wagon track, and stopped. There was no building to be seen, not a house anywhere in sight, nothing but a bare, barren plain. Then lights flashed out scarcely a dozen yards ahead of them, and, drawn up by the side of the road, they saw another and even larger automobile. Alexis waved his hand in triumph.

"Descend, Master," he begged Haven. "It is here we change."

"And afterwards?" Haven asked, as he buttoned his coat up to his throat.

"An hour's drive and then there will be safety. Wait till Paul has cleared the snow, then descend."

A spade had been produced and a way made clear. Quickly everything was transferred to the other car. Then they all turned their attention to the deserted one. On the right-hand side of the road was a drop of about twelve feet into the marshes. The driver turned the wheel, the three giants pushed. In a few seconds the great vehicle slid over and fell with a crash of breaking glass and splintering wood-work. With less than ten minutes' delay they were off along the new road, travelling more slowly now but also more smoothly. The three brothers were all inside, the other chauffeur having taken the front seat. Haven looked at them in amazement. Ivan, the shortest of the three, must have been six feet four, Paul was at least an inch taller, and the English-speaking Alexis, his immediate guardian, was little under seven feet.

"If you have been the Prince's men all your lives, what will you do when you leave me, now that the Prince and Princess are dead and the estates are broken up?" he asked them.

A moment before they had all been laughing and chatting volubly with the vivacity of children. Paul had been snapping his fingers and humming the tune of a Russian folk song. They were suddenly dumb.

"You will go back to Russia? You have wives and families perhaps?"

"We have wives and families," Alexis groaned, "but whether we shall ever see them again God only knows. It is a dunghill which we have left. There is no Russia."

"You don't believe in the new freedom then?" Haven asked.

"What does that mean to those of us who have served the Prince?" Alexis growled. "The people are mad. They have red poison."

"When we leave you," Paul confided in broken English, "we shall go south. In Georgia there may be hope. Around Moscow and in Petrograd we are known as the Ostrekoff men who have sometimes guarded the Tsar. There will be nothing but a prison or the wall there for us."

Their progress grew slower as the snow storm became denser. Sometimes the runners of the car became blocked and they had to stop while huge chunks of frozen ice were cut away. Haven, lulled into a curious sense of security, and worn out with the excitements of the day, began to doze. He woke from a fitful sleep to find Alexis rubbing the window clear with his coat sleeve. They had just passed between two great iron gates, with a lodge on each side, and were travelling up what appeared to be an avenue bordered with tall trees, ghostly white. At the end of about half a mile they pulled up in front of a square stone house of great size. Alexis sprang to the ground. The others tumbled out after him. Notwithstanding their height and weight, they all seemed to have the vitality and light-footedness of boys.

"We are arrived!" Alexis exclaimed. "American Master will be glad. There will be fire and food. It is a great journey we have made."

Strange-looking peasant servants opened the door and came out, bowing and curtseying. One, who seemed to have something of the dignity of Alexis and his brothers, and was evidently a sort of major-domo, led Haven across the stone hall to a great dining room, bare except for an enormous table and a score or more of fine oak chairs, all emblazoned with the Ostrekoff arms. The walls were panelled with some ancient wood which showed everywhere signs of decay. At the farther end was a musicians' gallery, empty and dilapidated. The place was marvellously heated by an immense stove, set in front of a fireplace, upon which an ox might easily have been roasted. Haven threw off his overcoat and stretched himself with a delightful sense of returning animation. He dipped his fingers in a porcelain bowl presented by Paul, passed them over his forehead, wiped his face and hands on fine linen offered by Ivan, and drank a glass of old vodka tendered by Alexis. In the background, the little company of servants were still peering and gesticulating.

"Where are we?" Haven enquired.

"It is the shooting lodge of an estate belonging to His Highness," Alexis explained. "Once there were bear here and His Highness would come for the shooting. Now the farmer and the farm hands live near by. The Master will be safe. We shall watch. There is food coming."

Haven flung the water once more over his eyes and conquered for a time his deadly sleepiness. He sank into the chair which Alexis had placed at the end of the table. Half a dozen servants had been running back and forth, but the place was now deserted. In front of him stood a huge brown dish full of some sort of stew. Alexis removed the cover. A deliciously appetising odour escaped with the steam which floated upwards toward the ceiling. There was a loaf of bread, and a great chunk of butter on one side; on the other, a bottle of whisky, a bottle of red wine of Hungarian growth, and a jug of water.

"American Master is served," Alexis announced.

Later on, in a room almost as large as the banquet hall, and on a bed the size of a tent, Haven slept like a log. Outside on the landing, with his back to the door, Alexis, with his gun on his knees, also ate his stew, smoked his pipe and watched through the night until he was relieved by Ivan. Downstairs, in the centre of the hall facing the front door, Paul too, with a rifle by his side, ate his stew and watched.

Morning dawned without visible signs of its coming. Huge banks of black clouds still held the earth in darkness. Haven sat up in bed with a shiver. Alexis was busy piling logs into the stove. He looked around with a cheerful smile.

"All day long it will snow," he announced. "It is good."

"The devil it is!" Haven grunted. "Why?"

Alexis stood up. He was dressed only in shirt and breeches and a huge mass of tousled hair almost covered his face. The eternal smile was there, however, at his lips.

"Our tracks here," he explained, "all buried—all lost. The car feet deep in the snow. No one will find."

"But who do you suppose is looking for us here?" Haven enquired.

Alexis drew a little nearer to the bedside. His expression became grave.

"Early this morning," he confided, "we had word by telephone that a body of Russian revolutionaries had crossed the frontier. They come by order of Starman, the peasant miller, the man who is now sacking Petrograd. They have special passports, with an appeal to the authorities here: they come in search of you—American Master."

"Good God!" Haven exclaimed. "What about pushing on?"

Alexis shook his head ponderously.

"Too much snow," he said. "Here they will not find us. We are hidden. The world is hidden. The road along which we travelled is part now of the marshes."

"But it is late in the season for snow like this," Haven pointed out. "It can't go on. Surely we should be safer if we got farther into the country and then made for one of the towns?"

"Safer here, American Master."

Haven considered the matter, frowning.

"What about telephoning to the nearest barracks?" he suggested. "Russian revolutionaries have no right this side of the frontier."

"Telephone went at five o'clock this morning," Alexis announced. "Either broken or cut ten minutes after we received our message. Paul has been out to examine. He thinks cut. What does it matter? We have food and wine and we are three who have broken up a mob. We shall protect young master. Those were our orders from His Highness. There is nothing else left to us in life."

The fire was roaring in the stove. Haven turned over in the bed. He felt the belt around his body, he patted the satchel chained to his wrist.

"I suppose you know best," he muttered drowsily and slept once more.

Haven awoke from an aftermath of sleep, marvellously refreshed and acutely aware of two strange happenings. The one was a positive blaze of sunshine, filling the crude, but stately apartment in which he lay with soft and almost unnatural illumination, and the other was the distinct crack of a rifle which seemed to him to come from immediately below his window. He slipped from his bed and peered out. Some forty yards away, from the centre of a circle of what, in the summer time, might have been turf, a youth in the costume of a Russian peasant, but wearing a grey military overcoat, was crawling on all fours. Under the trees of the avenue a little gathering of men were moving restlessly to and fro, talking and arguing together. Presently one of them emerged with a white handkerchief tied to the end of a stick. He paused to speak to his comrade, who was now limping back to shelter, and helped him for a few yards in his progress. Then he approached the house, waving his white flag vigorously, and came to a standstill about a dozen yards from the front door.

"Who will speak with me?" he called out.

Haven was on the point of completely opening the window, in order to hear better what was going on, when he felt a couple of mighty arms around his waist. He was drawn back by an invincible force.

"The master must not show himself," Alexis insisted. "It is for him they come, this rabble."

"Are these the men you spoke of?" Haven asked. "Who are they? Where do they come from?"

"They have crossed the frontier after you," was the grim reply. "They are Russian revolutionaries, men of Starman the miller."

"But they can't follow me here," Haven objected. "This is Poland."

Alexis shook his head.

"The great war wages," he said solemnly. "Men do strange things. There is Starman, and there is a little Jew who loves money, fighting for power in Petrograd. What does trouble with a sister country such as Poland mean to a country in the making, like Russia, when the laws are all upside down and an honest man does not know whom to call his master? It is money alone which counts and money which they must have."

Haven looked straight into the blue troubled eyes of the senior of his three guardians. How much did they know, he wondered? And, if they knew everything, how much did they fear?

"Why should they expect to find money here, Alexis?" he asked.

"The young American master knows," was the calm rejoinder.

Haven walked the length of the room and back again. The satchel was tucked securely under his arm.

"Who is talking to them below?" he enquired, as he neared the window again.

"It is Ivan," Alexis confided. "He is better at words and it is he who is on guard there. If only the snow had not suddenly stopped, they would never have reached us. If the young master would hear what Ivan says, he must remember always to keep himself invisible."

Alexis lifted the window sash a few more inches and Haven, kneeling down, listened.

"We tell no lies," he heard Ivan say. "We are not men who deal with anything but the truth. We are Russians as you are and we love our country as you do. But we have with us one who is in our charge—an American who carries with him papers belonging to his country. Him we shall conduct to safety, as we promised to our only and great master—the noble Prince Ostrekoff."

The man who stood feet deep in the snow chuckled. He had an evil face, a mouth like the mouth of a fox, narrow eyes and straight black hair almost reaching to his shoulders.

"You have no noble master," he jeered. "Michael Ostrekoff was sentenced to be shot yesterday in the fortress by order of the new Government. He chose to blow out his own brains. Wise man! There were many who would have been glad to kick the corpse of an Ostrekoff."

"Then the new Government may stew in hell before I stir a finger to help it," was Ivan's fierce reply. "Be he dead or alive, we carry out our master's orders. You have crossed the frontier and broken the law. Soon the Poles will be here to whip you and you will wish then that you'd stayed where you belong."

"We waste breath," the man in the snow declared, with signs of wicked temper in his expression and tone. "Give up the young American and what he carries with him, or we will set fire to the house and massacre every one within it."

Ivan laughed, and when he laughed it was as though the timbers of the house behind were creaking and the boughs of the trees swaying in sympathy. It was a roar of mirth which set even the muscles of Haven's mouth twitching and which brought a grin to the face of his guardian.

"We in this house are the Prince's men on Polish land, in which country our master is also a noble of great account," was the sturdy reply. "If you move a finger against us, those of you whom we do not kill will hang from the trees in the avenue when the Poles arrive. Get back over the frontier if you want to save your skins."

Ivan, with a gesture of contempt, turned around and strode back into the house. The emissary of the marauding band made his difficult way to the shelter of the avenue. The conference was at an end.

Alexis rolled a cigarette of black tobacco, which he emptied into the palm of his hand from a horn box.

"A little fighting," he grunted, "will be good for the muscles."

Haven moved into the anteroom, broke the ice in the zinc bath and, hanging his belt carefully in front of him, stripped and washed.

"The worst of fighting nowadays, Alexis," he remarked, as he crossed to the front of the stove, rubbing himself vigorously, "is that it all consists of little spits of fire, a pain in the chest, a hospital and a coffin."

Alexis nodded gloomily.

"Nevertheless," he argued, "there is also a thrill when the finger caresses the trigger and the eye works from the brain. Paul, Ivan and I, when we were striplings, before the master called us to his personal service, were rangers on his shooting land. We knew where to find wild boar and bears and we could smell the wolves whenever the wind moved. We learnt to shoot in the dark or in the light. Even if the battle comes to us that way, we are better than other men, American Master."

Haven, who had secured his belt and was completing his toilet, glanced out of the window.

"Well, it seems to me we shall soon learn something about a new method of fighting," he said. "You see how they are spreading out, Alexis? What about the back of the house?"

Alexis smiled contemptuously.

"The back of the house," he confided, "is solid stone for twenty feet high with neither foothold nor fingerhold for any human being. There is not a door or a window in the whole wall. Remember we are close to the frontier, young Master, and amongst a troublesome race. When this house was built it was a castle. There was fighting all the time. Even to-day the doors are a foot thick and to reach the lower windows one must climb. These men ask for the cemetery."

"There are only four of us to shoot," Haven reflected, a little dubiously.

"There are six other rangers within the house," Alexis told him. "Besides, there are two who have gone off to Irtsch to report to the Commandant that there is a raid of the Russian revolutionaries. They are men like us who can pick out the white of a bear's eye. Have no fear. It is not from such danger as this that you will suffer. Young Master would like to try his skill with a rifle, perhaps?"

Haven shivered. After all, these black crawling figures, scum of the earth though they might be, were human beings.

"I don't want to kill for the sake of killing," he objected.

"It may be that you will have to kill to save your own life," Alexis replied. "There are more of them than I thought and they all seem to have come armed. I think that Paul and Ivan will be shooting directly. I shall fetch rifles."

Almost as he spoke, three shots rang out from the lower part of the house. The three foremost figures in the line of invaders sank slowly into their bed of snow. Alexis scarcely glanced out of the window.

"I shall fetch rifles," he repeated. "Soon they will have had enough. After all, they have small chance of hurting us, and for them it is suicide."

Apparently the forward centre of the semicircle had had enough already, for no one hurried up to take the places of the fallen men. On the extreme right, however, nearer the opening from the avenue of trees, half a dozen of the invaders were almost flush with the house. Haven hurried into the anteroom and, opening the window a few inches, took careful aim at the man below with his automatic. The first time he missed. At the second discharge, the Russian, who had stopped with a start at the sound of the first shot, threw up his arms and collapsed. Haven heard the boards creak behind him and turned quickly around. Alexis was crawling like a bear on three legs across the floor, with the butts of two rifles under his free arm. He peered over the sill.

"Good!" he approved. "That was the dangerous spot. Still, one should not miss. It gives confidence. Watch, Master."

The muzzle of his rifle stole downwards. There were three men below, all of different heights, all closing in upon the angle of the house. Alexis' rifle spat out and the first one fell. The second one followed him in a matter of seconds. A bullet from the third sped through the window only a few inches above Alexis' head and buried itself in the wall. The man who had fired the shot and who had moved a step on one side in order to get a better aim never fired another. The sunlight which flashed upon his yellow hair showed the look of sudden bewilderment in his face, the opening mouth and the staring eyes. His rifle fell from his hands, he clutched at his chest, coughing, staggered backwards a few yards and disappeared in the snow.

"Well, well!" Alexis murmured. "They had better have gone to be food for the Austrian bullets. They would have lived longer. If these men had known that it was the Prince's rangers whom they faced," he added, with the happy self-complacency of a child, "they would never have ventured near the house."

The semicircle was broken and the attackers had withdrawn to the shelter of the avenue. Haven and his companion moved back to the front room. A fat, smiling woman, with heavily braided brown hair and face redolent of soap and sunshine, was busy setting out upon a table a huge bowl of coffee, a loaf of bread, some butter, and a great dish of fried bacon. Haven hastened to complete his toilet.

"Sit down, Alexis," he invited.

The man looked at him in round-eyed surprise. He was already standing at attention behind the high-backed chair which he had placed at the table.

"American Master will eat," he said quietly.

A fantastic week! Haven was never able to take real count of it or to realise the swiftly passing days. He seemed to be always tumbling into bed or called to the table to eat enormous dishes of stew—stew composed of bear's meat, hare, rabbit and birds which he judged to be pheasants. There was a great stock of crude red wine always on hand, of which he drank sparingly, and a small stock of whisky and brandy, both of the best. The besiegers who were camped in the avenue appeared to have lost their enterprise. All the time Alexis was walking from room to room, making ceaseless perambulations of the house, continually on the watch for an attack which never came. Only once Haven heard the crack of his rifle, and, hastening to the window, saw a dark splotch which he knew to be the figure of a man lying at the extreme end of the avenue. Alexis beamed at him with all the joy of a contented child.

"They are mad to face the rifle of the Prince's ranger in chief. Does Little Master know what I would do, if I missed one of those pigs? I think that the shame would kill me. It is like burying one's weapon in the hay and shooting the stack."

"You seem to have scared them off pretty well," Haven remarked.

"They wait till the night," Alexis explained contemptuously. "They think they will have a better chance. Ivan there has fixed up a searchlight from the dynamo. If ever they venture to come, we'll turn it on them and shoot them like frightened rabbits."

But there was to be no night attack upon the Prince's shooting box. Just before the coming of dusk on the sixth day, Alexis, who was standing on duty outside the door of the great dining room, made hasty and, for him, unceremonious entrance. He had laid down his rifle, a sign that it was not an attack he feared, and with a gesture of apology he drew aside the curtain, turned out the lights and threw open the window. Haven, hastening to his side, was conscious of a medley of distant sounds. Through the trees of the avenue came red flashes of flame, there was the thud of horses' hoofs, hoarse unintelligible cries, the crackle of Maxims and the yell of dying men—a battle going on, there in the avenue and in the road beyond, between the besiegers of the shooting box and a new force. Alexis watched long and anxiously. Then he closed the window.

"It is a massacre," he announced. "A company of Polish cavalry with Maxims in motor wagons."

"Bravo!" Wilfred Haven exclaimed. "Now perhaps I shall be able to make a move."

There was no answering gleam of satisfaction on Alexis' face. He walked the room restlessly for a moment; then, saluting, withdrew. Presently he reëntered.

"Little Master will come this way," he invited.

"What's wrong?" Haven enquired, as he rose to his feet.

Alexis explained his fears as they crossed the stone-flagged hall.

"This Russian mob," he confided—"this spawn of the revolutionaries from Petrograd—they will, without a doubt, tell the soldiers who have fallen upon them of the presence here of Little Master, of their own mission, and for what reason he is guarded by the Prince's men."

"I can't see that that matters so much," Haven observed.

Alexis shook his head gravely.