| • Chapter I • Chapter II • Chapter III • Chapter IV • Chapter V • Chapter VI • Chapter VII • Chapter VIII • Chapter IX |

• Chapter X • Chapter XI • Chapter XII • Chapter XIII • Chapter XIV • Chapter XV • Chapter XVI • Chapter XVII • Chapter XVIII |

• Chapter XIX • Chapter XX • Chapter XXI • Chapter XXII • Chapter XXIII • Chapter XXIV • Chapter XXV • Chapter XXVI • Chapter XXVII |

• Chapter XXVIII • Chapter XXIX • Chapter XXX • Chapter XXXI • Chapter XXXII • Chapter XXXIII • Chapter XXXIV • Chapter XXXV |

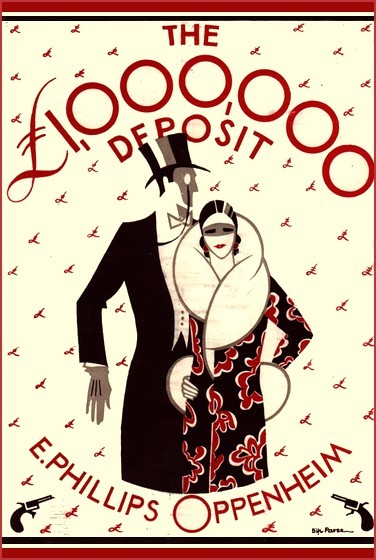

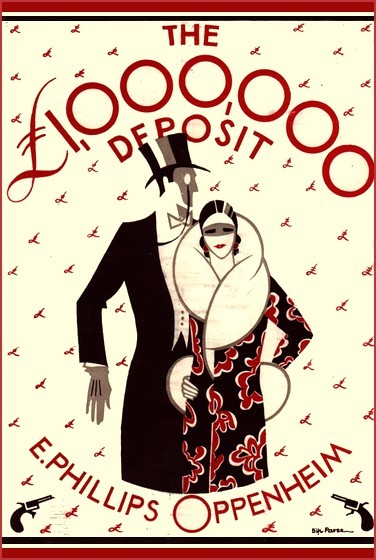

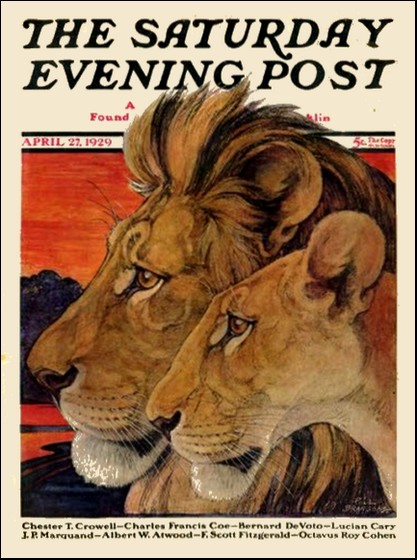

"The Saturday Evening Post" with Part 2 of "The Million-Dollar Deposit"

NED SWAYLES, the younger of the two men seated in an obscure corner of the cheap, odoriferous restaurant of which they were the only occupants, stretched out a long, shapely hand across the soiled tablecloth, and turned towards him the watch which he had detached from its chain. His protuberant knuckles, the prehensile, electric crawl of his fingers, had awakened a great many speculations at various times as to the nature of his occupation.

"Twenty minutes after nine," he muttered. "He surely is late."

His companion, a shock-headed, weedy-looking man, with a mass of black hair, unwholesome of appearance, untidily dressed, and apparently as nervous as his vis-à-vis, grunted assent as he drummed with restless fingers upon the table. He had been seated with his eyes fixed upon the door for the last ten minutes, starting eagerly whenever a passing shadow darkened the threshold, only to relapse into gloom again as the loiterer disappeared. The place was really little more than a shop with a back room dignified by the name of a restaurant. There were a few meals served there in the daytime, scarcely any at night. On a side table, underneath the meat covers, upon chipped and unsavoury dishes, reposed half a ham, the worst remains of a joint of beef, and a fragment of tinned tongue. A weary-looking salad was protected by a piece of muslin. There were no other signs of edibles, but the odour of past meals hung unappetisingly about the stuffy apartment. It was typical of many eating houses of its class, chiefly to be found in the neighbourhood of the great railway termini. The people who eat in them seem like the ghouls of disappointed travellers.

In the doorway, the only waiter—a disreputable object, half Italian, half cockney, with a shirt front which appeared to be tied on to him, and the clothes of his profession stained with the gravy of remorseless years—was struggling to get a breath of air. The heat of a long summer's day seemed to be reflected from the pavements outside, and the coolness of night mercilessly delayed. The heat stole into the unattractive little restaurant in gaseous waves. Swayles helped himself from a bottle of whisky which stood upon a table between the two men, and the liquid splashed on to the tablecloth from his unsteady handling. He drank it after the fashion of some of his country-people—neat, with a hastily filled tumbler of flat-looking water to follow.

"Say, if I'd known what sort of a job this was going to turn out," he whined, "I'd never have got myself stuck with it. I wouldn't care so much if it were in New York or Chicago. The bulls there know well enough that in eleven years I've never parked a gun. I've turned down every show where there hasn't been a slick get-away."

His companion dabbed once more at his moist forehead with a soiled handkerchief.

"Do you think I'd have been fool enough to be mixed up in it either?" he demanded, with feeble truculence. "I've known Thomas Ryde for fourteen years—a hard, keen little man, but one of the quietest-living, most respectable fellows I've ever worked for. Like a blooming machine, he's always been—never late for an appointment, never a glass too much, just plodding away, and saving money as though there were nothing else in the world worth a thought. I don't understand it even now. To think of him knowing how to grab hold of a gun even seems ridiculous. I've never seen him raise a little finger against any one."

Ned Swayles leaned across the table.

"When I took on the job," he confided hoarsely, "the first question I asked was whether it was to be a get-away affair, or a gunning business. I give you my word, Huneybell, that I've never touched a gunning job in my life. If they catch me, they catch me, and I'm ready to do my stretch. When we heard the footsteps in the passage, heard the door open, saw the light go up, and that old guy standing there gaping in at us, I was for the window, and a get-away quick as I could leg it. Ryde was standing just behind me. He didn't move—didn't say a word. Suddenly I saw his arm shoot out, saw the stab of flame, the old man spin round. My God! Do you know, Huneybell, I've lived in Chicago mostly since I was a kid, and I've never seen a man's light put out before."

Huneybell shivered in his place. The white agony of fear seemed carved into his twitching features.

"Why the hell doesn't he come?" he groaned. "Here, give me the whisky bottle."

He poured some into a glass, added water, and drank in long, feverish gulps. A huge bluebottle came droning around their table. The waiter abandoned his vain quest for air and lumbered up the room.

"Shall I serve the chops, sir?" he enquired. "Perhaps the other gentleman's not coming."

"Of course he's coming," was the angry reply. "He's certain to come. He'll be here directly."

"The chops will be burnt all up," the man warned them.

"Oh, God, bring them right along," the young American ordered. "Let's eat! Let's do something! Here, waiter, got any wine in this bum place?"

The man produced a battered wine card. Swayles glanced at it in disgust. His delicate forefinger pointed to the single printed line under the heading of "Champagne."

"What is it?" he demanded. "What mark?"

"It's champagne," was the cheerful reply. "Forgetta label. Very good wine."

"Bring a bottle," Swayles directed. "Take away this filthy whisky. Don't stop for wine glasses; bring tumblers."

The man shambled off, opening a door in the rear of the place which let in a hot wave of air from below, and a smell of greasy cooking.

"Say, this junk has got me scared, and that's a fact," the young man went on, fingering his flowing tie. "Your boss may have hopped it. I don't reckon he set about this job meaning to kill two men. Supposing he's made a clear get-away—if we get nabbed they won't know who did the shooting. I guess the law's the same over here as with us. If there's a gang, and one man's plugged, the lot have got to answer for it."

Huneybell left off burying his hands in his over-luxuriant hair, took one more long gulp of his whisky, and leaned back in his chair. Alcohol had accomplished something of its task. He was feeling more of a man.

"You're a nervous sort of chap for a Chicago thug," he scoffed. "I'm as scared as you are about the whole show, but I'm not worrying about Thomas Ryde. I'll tell you something about him, Guv'nor. What he says he's going to do, he does, and that's the end of it. He's what they call an 'organiser.' That's his job in life. What he says comes to pass and don't you forget it. I tell you that except for the shooting he'd got this affair cut and dried like a master."

"I lost my pep from the moment he handed out the masks," Swayles confessed. "I sure didn't like the feel of them."

"Never again," Mr. Huneybell declared earnestly, "will I believe in these stories of slick American criminals. Mind you, I'm scared to death, but I'm going to hand it to the guv'nor that he ran that business almost as well as he reorganised the waste-stuff department. What about the get-away, Mr. Ned Swayles? Perhaps you like the way he managed that part of the business better? Ten miles in one car, eight miles in another, all of us separated, west, east, south, even north. Different numbers at every change, and different roads, and never a second to wait. Why, we scarcely knew where we were ourselves. He must have taken a week thinking that out, and, mark you, not a hitch, not a car stopped, not a word of suspicion, and here we are in London, and there isn't one of us who hasn't got an alibi in his trousers' pocket."

"It was a swell get-away," Mr. Ned Swayles admitted, "but if one of us comes a mucker, he drags the lot of us in. Where's your Mr. Thomas Ryde? That's what I want to know."

A shadow darkened the threshold. The two men leaned forward in their places. Huneybell breathed hard. Ned Swayles, from his deep-set eyes, flashed out the fires of welcome. A trim, rather short man, approaching early middle age, very neatly dressed in cool grey, with gold-rimmed, tight-fitting spectacles, Homburg hat, and carrying a carefully furled umbrella, walked precisely through the outer shop and entered what was apologetically called the "restaurant." He made his way at once to the only occupied table. The two men stared at him as though he were a longed-for vision. Something which was meant to be a greeting stuck in Swayles' throat; his companion stretched out his hand and upset his glass.

"Before you speak," the newcomer began, taking off his hat and hanging it upon a peg, "accept my apologies for this regrettable unpunctuality. For the second time since I initiated our little enterprise, things have not gone altogether according to plan. In Brighton, I had an intelligent chauffeur. At such a time, intelligence is not a quality one appreciates amongst those with whom one comes in contact. I thought it as well to get rid of him and come up by train."

Once again that expression of shivering fear whitened the face of the young American.

"Get rid of him!"

"Ah, not in that sense," Mr. Thomas Ryde protested. "The situation presented no threatening possibilities. He saw me off on a Channel steamer to Calais, or rather he thought he did, and I came up to town by train. Is it my fancy or do I find you two a little disturbed?"

Huneybell mopped his forehead but remained dumb. Ned Swayles groaned.

"See here, Mr. Ryde," he explained, "we're scared—Huneybell and I are—scared stiff. I asked you the question straight. Was it a gun job or was it not? You told me to quit that line of talk right off—swore you'd never parked an automatic in your life."

"My dear young friends, be reasonable," the newcomer urged. "Principles depart with the coming of necessity. What else was to be done? Who could have divined that that poor fool Rentoul would have stayed in his laboratory till the middle of the night, and then have blundered down upon us? There he stood, with his hand within a foot of the main electric alarm bell—a single touch, and you know what that would have meant. You must remember too, Huneybell, that, notwithstanding our masks, you and I are not altogether strangers at Boothroyds' Works."

"That's all right," Huneybell assented, "but what about poor old Michael?"

The slightest possible shrug of the shoulders. "Poor old Michael" apparently failed to evoke any sympathetic reaction.

"One regrets, of course," was the cool reply, "but he would have had the gates closed upon us in a minute if he hadn't been dealt with. By-the-by, does this somewhat unsavoury restaurant possess any attractions in the shape of food?"

"We ordered chops," Huneybell confided. "They've been keeping them waiting for you I don't know how long."

Thomas Ryde looked around him disparagingly.

"It is not the spot I should have chosen on a hot summer's evening," he observed, "to celebrate the termination of a successful enterprise. Still, so far as privacy is concerned, it has its points."

Luigi, who preferred to be called William, came tumbling in through the back door. He carried in the crook of his arm a chipped, japanned tray, upon which reposed a covered metal dish and some plates. In his other hand he carried the bottle of champagne. In cheerful and unembarrassed silence, he placed the dish upon the table and displayed its contents, distributed the plates, fetched from the cupboard an attenuated-looking bottle, containing a few tablespoonfuls of Worcestershire sauce, put salt and pepper in coarse utensils of battered glass within reach of his clients, and stood back to survey the result of his labours.

"You didn't order any veg.," he reminded them. "It wouldn't have been no good if you had, because we no got any."

Ned Swayles, described as of no occupation, who boasted an address in Riverside Drive, and was a well-known patron of one of New York's famous night clubs, gave vent to a little groan. Thomas Ryde, however, helped himself to the least repulsive of the chops, passed the other two to his companions, and commenced his meal. The waiter, with a flourish, opened the wine. Ned Swayles and Huneybell held out their glasses eagerly; Thomas Ryde shook his head.

"A larger tumbler," he directed, beckoning for the whisky bottle, "some ice, and Schweppes soda."

"No gotta ice," the waiter explained equably. "Soda water in syphons."

Thomas Ryde motioned him a little nearer.

"Opposite to us," he confided?"just across the road, as a matter of fact—is a public house where Schweppes soda water can easily be procured. Ice too—just one tumblerful of it—should present no difficulties."

He produced a ten-shilling note, and the waiter, after a moment's hesitation, disappeared with it. Ned Swayles gulped down his glass of champagne, and the tang of it, young and sour though it must have been, apparently gave him courage. He addressed himself earnestly to Ryde.

"Look here, Boss," he demanded, "what I want to know is, where am I on this deal? I opened the safe for you—a job not another lad in England could have done—and all we found was six thousand quid and a lot of musty old papers. According to you, the thing should have been worth a lot more. You guaranteed me—now, Boss, don't you go denying this, because I can be nasty if I try—you guaranteed me twenty-five grand."

"Quite correct," Mr. Ryde acknowledged. "Could I trouble you for the salt—just by your sleeve, there—Thanks. Twenty-five grand is, I believe, equivalent to five thousand pounds, Mr. Swayles. A good deal of money, but I must confess that you earned it. Your opening of that safe was without a doubt a masterpiece of scientific ingenuity."

"I'll agree I earned it all right," the young man affirmed anxiously, "but am I going to get it, Boss? That's what I want to know."

Mr. Ryde seemed a trifle hurt.

"My dear Mr. Swayles!" he remonstrated. "I can assure you that I am not a man who fails in his engagements."

"Well, where's it coming from?" the other persisted. "There was only six thousand in the safe altogether."

Mr. Thomas Ryde looked critically at his napkin and, finally deciding in its favour, wiped his lips with a corner of it.

"Following my usual custom, Mr. Swayles," he said, "of taking into my full confidence the members of any enterprise in which I am concerned, I will confess to you at once that we others were not out altogether for treasury notes. To tell you the truth, I did not expect to find much more than we did find in available cash. You may have noticed, however, that I removed a number of papers at the same time as the money. It is from them that we expect to derive our share of the booty. With the exception of one thousand pounds which we need for current expenses, the five thousand pounds is yours, according to arrangement. The papers are ours."

The American remained suspicious. The psychology of Mr. Thomas Ryde was a thing hidden from him. He had a vague idea that he was being talked at for some occult reason.

"Blast your papers," he muttered, with a little twist of the lips. "Let me see the five thou."

"A trifle impetuous surely, my young friend," was the gently reproving rejoinder. "However, since you insist?"

Mr. Ryde looked around to be sure that the waiter had not returned. Then he laid down his knife and fork, picked up the small black bag which he had deposited under the table, and handed across a packet.

"You will find there," he announced, "five thousand pounds, a considerable portion of which sum, being evidently intended for the purpose of wages, is in treasury notes which cannot be traced. The larger bank notes I should take with you to the States and part with them gradually."

The young man clutched at the parcel, cut the string, and looked inside. There seemed to be endless folds of treasury notes there, side by side with a thick roll of crisper white paper. He drew a deep sigh of relief and thrust the spoils of his enterprise into his pockets.

"Well, I'll say this for you, Boss," he admitted, "you've kept your word, and well up to time too."

"I always keep my word," Thomas Ryde assured him. "You earned your money, Mr. Swayles, and if," he added, with a slight smile at the corners of those straight lips, "you would like a testimonial, you can have it. I am not an expert in such matters, but your opening of that safe still seems to me a marvellous piece of scientific ingenuity."

The young man moistened his lips with his tongue. He had lost his distrust of the speaker but he still looked at him as though fascinated.

"There's only one I've known as cool a hand as you, Boss," he acknowledged, "and that was King Cole of West Chicago. Still, you oughtn't to have done that killing on us."

Mr. Thomas Ryde seemed mildly puzzled.

"I fail to understand your complaint," he protested. "Without the killing, we should probably all have been in prison by now and not one of us would have made a penny out of all the time and labour we have given to developing this little affair. Our careers, too, would have been ruined. I will leave you to judge of your other associates, but you must remember that Huneybell here and myself are no more criminals than they are."

"Gee, you're not criminals!" Ned Swayles gasped.

"By no means. I doubt whether either of us has ever previously committed an unlawful action. To have been convicted, therefore, would have been a very serious affair for us. We should have lost our position in society and at the end of our terms of penal servitude we should have been paupers. You will see, therefore, that I had no alternative but to insure against such a lamentable prospect."

The waiter came bustling back. He produced two bottles of Schweppes soda water, and a tumblerful of ice. Mr. Thomas Ryde indicated his approval and waved away his change from the ten-shilling note.

"I am very much obliged to you," he said. "I shall now be able to enjoy my supper."

The American filled his glass once more, drained it to the dregs, and rose to his feet. There was at last a slight flush of colour in his cheeks. He patted the very obvious protuberances which quite spoilt the shape of his well-cut suit of clothes.

"Well, I'm through, Boss," he pronounced. "I've worked in a few queer jobs in my time, but this one has the lot of them smothered."

Mr. Ryde nodded an affable farewell.

"Your boat sails at midnight," he reminded his departing associate.

"You needn't be afraid that I'll miss it," was the emphatic comment. "This old country is too full of surprises for me."

Huneybell, too, staggered to his feet. He was looking ghastly ill.

"You're not going?" Thomas Ryde queried.

"I shall die if I stay another five minutes," he gasped. "I can't eat, I can't drink any more—I'll go home and lie down."

Thomas Ryde adjusted his spectacles and stared at the speaker curiously. There was no sympathy in his observation—simply a slight expression of intolerant wonder.

"Just as you like," he agreed. "Keep your mouth shut and be at the office at ten o'clock to-morrow morning. You had better get into a taxi," he added, as he watched his departing employee stagger towards his hat.

"I shall be all right as soon as I get out of here," was the feverish response.

The two men left the place together, Ned Swayles' hand still caressing those exhilarating extensions of his pockets, Huneybell with black fear creeping like mortal sickness through his body. Mr. Thomas Ryde looked after them curiously for a moment. Then he selected the better cooked of the two remaining chops, mixed himself more whisky and soda, listening with obvious pleasure to the tinkle of ice in his glass, and continued his meal.

AT half-past eight precisely, on the eleventh evening after the sensational burglary at Boothroyds' Works, near Leeds, Mr. Thomas Ryde drove up to the Embankment entrance of the Milan Hotel and by a very complicated route succeeded in skirting the foyer, mounted three flights of stairs, traversed a long passage, mounted one more flight, and finding the door of apartment number 332 unlatched, as he had expected, passed rapidly through it and disappeared. Within three minutes, Mr. Huneybell, who had to some extent recovered his composure and his poise, descended from an omnibus at the corner of the Savoy Hill, and by exactly the same route reached the same destination. At twenty-seven minutes to nine, a tall young man of somewhat foreign appearance, of pale complexion, with eyes of a strange shade of greeny-brown and closely cropped dark hair, presented himself at the main reception offices of the Hotel and enquired for Doctor Hisedale. The clerk scribbled the number 332 upon a card and handed it to a page.

"The doctor is expecting you, Baron," he announced, with a bow. "The boy will take you to his room."

The tall young man followed his guide as directed. In the last corridor, he came face to face with a short, thickly built person of obvious transatlantic origin, who was just stepping out of the lift. The two men exchanged civilities.

"Mr. Hartley Wright, isn't it?" the tall young man asked, holding out his hand.

"Sure thing, Baron. Glad you haven't forgotten me," the other acknowledged, with a grin.

They made their way to apartment number 332, where their host was engaged in conversation with the two previous arrivals. He turned to greet them, a tall, lanky man, with grey hair and carefully trimmed grey moustache, the former cut so short that it gave his head the appearance of being shaven. He had very clear, but hard black eyes, effectually concealed behind heavy spectacles. His speech was slow, and his accent slightly guttural. No one could have mistaken him for anything but a German.

"Welcome, Baron," he said. "Welcome, my friend Hartley Wright. We are all here now, I think. Introductions," he concluded, with a ponderous attempt at levity, "are, I take it, unnecessary. You are all well acquainted."

The newcomers exchanged restrained greetings with their predecessors. A waiter entered with a tray of cocktails. They were drunk almost in silence and without any toasting. Mr. Thomas Ryde alone inclined his head towards his host. It was the only sign of good-fellowship.

"Dinner," the latter instructed the waiter, "can now be served. Will you take your places, gentlemen. Mr. Ryde, here upon my right; Mr. Hartley Wright upon my left; the Baron opposite; Mr. Huneybell in the remaining place. I have provided you only with simple fare."

"The simpler the better," Hartley Wright said tersely. "I'd sooner talk than dine."

"We must remember," Thomas Ryde pointed out, "that we are in England. A company of five men meeting to discuss a business project in an hotel sitting-room, who did not lunch or dine or drink, would give cause for comment. There seems to be a feeling amongst you all which it is not easy to understand. Let us shelve it for a moment. Let us play our parts as a little assembly of commercial magnates met to discuss an important proposition."

A waiter entered the room, wheeling forward a side table, upon which were set out caviare, hot toast and butter, and bottles of champagne. Doctor Hisedale showed his appreciation of his guest's suggestion, and attempted to play the part of genial host.

"Mr. Ryde has spoken sensibly," he declared. "We are met here for an important discussion, and presently let each man say what he has to say, but in the meantime let us eat and drink. The starved man argues ill."

The feast was served, but miracles do not happen, and the spirit of good-fellowship was not there. The five men ate and drank, and explored the stereotyped openings to general conversation. There were gloomy references to English politics, to the money rates in different capitals, to the stabilisation of the franc, and kindred subjects. Nobody was at his ease; everybody had the air of keeping back with difficulty what he really wished to say. Doctor Hisedale, after one or two efforts to inaugurate a general conversation, confined himself to discussing with the Baron de Brest the financial operations of several large German industrial concerns. Mr. Hartley K. Wright drank a great deal of wine and every now and then was heard muttering to himself. Mr. Huneybell at intervals ate voraciously and drank deeply but had also intervals of moody and nervous silence. When the coffee was served, the host beckoned the senior of the two waiters towards him.

"Place the cigars, cigarettes and liqueurs upon the table," he instructed. "Kindly see that we are not disturbed. If callers arrive, say that Doctor Hisedale is engaged in a business conference."

"Certainly, sir."

The maître d'hôtel and his underling took their leave. With the closing of the outside door, the atmosphere of tension came to an end. Mr. Hartley Wright was first in the field.

"See here, Doctor," he began, in a crude, unpleasant voice, "and you here, Thomas Ryde, let's get down to hard tacks on this. You've sprung a low deal on us—on me, at any rate. I, for one, never expected to be dragged into a high-class burglary, with a couple of murders thrown in. Neither did Huneybell, neither did Ned Swayles, who's never even handled a gun in his life. You're the man I'm talking at, Ryde; you're the man I blame. You made out that it was as simple as opening your aunt's workbox to get down there, and grab the Boothroyd formula. We all remember what your line of talk was—even if we stopped there was nothing to it. We weren't after money. Our lawyers would have pleaded business jealousy, and we should very likely have got off altogether. And now, look what you have let us in for."

"I have let you in for a sixth share of the Boothroyd formula," Ryde said, carefully clipping the end of a cigar—"a property which you could not have acquired by any other means."

"What's the good of a sixth share of anything," Huneybell intervened, shivering, "when day and night you think of those two dead men, and slink about expecting to be tapped on the shoulder and hauled off to prison?"

The Baron de Brest scowled across the table.

"I am entirely in sympathy with our friend from New York," he declared. "For a man in my position to have been dragged into a criminal affair like this is outrageous. If I had known that a single one of you was carrying a revolver that night, I should have gone straight home and had nothing more to do with the affair."

"The trouble of it is," Huneybell pointed out, his voice shaking nervously, "that when a party of men are engaged upon a burglarious enterprise as we were, if there's a man killed, it don't matter who fires the shot. We're all in it together."

"Let us hope," Doctor Hisedale protested, "that the law does not go so far as that. Personally, I shall not allow myself to believe it. I should advise you to follow my example—put all these disconcerting thoughts behind and look to the future. Let us act wisely. We are met to come to a good decision on this point. We have been led into paying a much greater price than we intended for the Boothroyd formula, but the Boothroyd formula is after all ours. What are we going to do with it?"

"I guess you're right, Doctor," the American assented. "This fellow Ryde has done us dirt, but what we've met to decide about is how to dispose of the booty. What's your idea of its value, now?"

Mr. Thomas Ryde scribbled on the back of the menu.

"I will tell you what it is worth," he said. "In eleven years it has earned for the firm of Boothroyd profits amounting to twenty-two million pounds. That is two million a year. It should be worth five years' purchase—that is ten million. That is what it will be worth to the buyer, but we sellers shall never realise half as much. I suggest that we ask two million for it, or one million in hard cash."

The sound of the figures was stimulating. The little company of men began to throw off their depression.

"That's some money!" Mr. Hartley Wright admitted. "But we've got to get near to it. Now listen to me," he went on, leaning across the table. "I have a suggestion to make. I am well known in Wall Street and close to some of the leading financiers in the United States. Give me the formula and let me see what I can do. If the offer I am able to cable over isn't satisfactory, if I can't get what you think the thing's worth, then one of you others can have a try. What I say, though, is that there's no money worth speaking of anywhere else except in the States. Give me the formula, and I'll catch Saturday's boat."

Doctor Hisedale pursed out his thick, red lips.

"I shall say at once," he pronounced, "that without any personal bias I am against parting with the formula to any one man."

"Then how the hell are you going to dispose of it?" Mr. Hartley Wright demanded.

"I know of two manufacturing concerns in Germany," Doctor Hisedale replied impressively, "who would combine and buy the Boothroyd formula, provided they were convinced that it was genuine."

"Yes, and what money would you get?" the American sneered. "Listen here, boys. We've gone and mixed ourselves up in an ugly business. We need to make enough money out of it to keep us in good shape for the rest of our lives."

"That is more than a need; that is a necessity," Doctor Hisedale grunted. "But the sooner this is clearly understood the better. No one of us is going to dispose of the Boothroyd formula in the way suggested by our friend from the States here. No one is going around to make a deal on his own account. Business is business," he concluded significantly.

"If no one's going to trust any one else," the American demanded with savage emphasis, "how are we going to dispose of the damned thing at all?"

"Not, under any circumstances, in the way you are suggesting," Thomas Ryde intervened, knocking the ash from his cigar, and speaking with cold and convincing precision. "I put it to you, gentlemen, that our friend's idea is blatant, impossible, and highly dangerous. He forgets that if he approaches any financier in the United States during the next fortnight in the manner he proposes and endeavours to open a deal for the Boothroyd formula, he will probably spend the next night at Police Headquarters, waiting there for a report from Scotland Yard."

There was a brooding silence. The words of the last speaker were destructive enough but failed to convey the inspiration for further discussion.

"An American business man doesn't go blabbing his affairs all over the place," Hartley Wright ventured.

"America is the richest country in the world," Mr. Ryde continued calmly, "but that does not mean that Americans part with their money more readily than any other people. I need not remind you that it is not the millionaire who gives the biggest tips, or the richest man who heads the subscription list. Furthermore, the New York business men are the shrewdest in the world, and I do not believe that one of them would be content to buy a property in the dark for the price we shall want for it. You cannot sell the Boothroyd formula in that way, nor, I regret to add, would it be wise to attempt to take the initiative ourselves towards selling it anywhere at all for the next few months."

Mr. Huneybell's nervous fingers were plunged in his thick crop of black hair.

"After all we've been through," he bewailed, "do you mean that we can do nothing but sit still and wait indefinitely?"

Thomas Ryde splashed a little more of the liqueur brandy into his glass and swung it round thoughtfully.

"My friends," he expostulated, "you expect things made too easy for you. Remember that this is no ordinary division of plunder. I should say that each one of us here present possesses at the present moment the equivalent of approximately one hundred and seventy thousand pounds. Money like that cannot be snatched at."

"Show me the way to my share," the American groaned.

"On the other hand," Thomas Ryde went on, ignoring the interruption, "if one of us so much as stirs a finger, drops the merest hint as to where the Boothroyd formula is to be found, the whole game is up. I am quite aware that I am unpopular with every one of you because I took the only possible means of carrying through our enterprise successfully. We will not discuss the question further. We were out for a coup to make rich men of ourselves for the rest of our lives, and when unexpected trouble came, my idea was to deal with it in the only way it could be dealt with. I will admit," he continued; after smoking thoughtfully for a moment or two, "that it complicates the situation to some extent and makes it a little more difficult for us to realise our reward. I admit this frankly and I even impress it upon you. For the sake of our skins, I suggest to you all most earnestly that not one of us approach a single person directly or indirectly with reference to a purchase of the Boothroyd formula. Let us be content to wait. Believe me, one of two things will happen—either Boothroyds themselves will offer a huge reward for the return of the formula and no questions asked, or some other possible buyer—one of the great continental firms, perhaps—will begin secret enquiries here in London, knowing that the formula must be somewhere for sale. It will then be easy enough through a trusted third person to get in touch with our market. In plain words, gentlemen, let our buyers come to us. Don't let us go to them."

"And in the meantime we are to starve, I suppose," Huneybell muttered.

"There is no question of starvation for anybody," Thomas Ryde asserted swiftly. "You, Huneybell, for instance, have a very good job as town traveller in my small business. I pay you six pounds a week, and if things turn out as I expect, in less than a month's time I will be able to pay you eight. You are, I think, something like thirty-six years old. Have a little patience. Even a year should not be too long for you to wait to be made a rich man for the rest of your life.—You, Doctor Hisedale, are a scientist. What your income may be I do not know, but your laboratory at Notting Hill is famous, and one presumes that you do not occupy a suite of rooms like these on an inadequate income."

"I do not see what difference that makes," Doctor Hisedale protested. "I must live comfortably because it has been my custom, but all the time I need money for experiments."

"We will put it this way then," Thomas Ryde continued. "You are not in urgent need. In the cause of safety you can very well afford to wait for twelve months.... You, Baron de Brest, are, of course, in a different category altogether. You are a wealthy man at any time, and to wait will not inconvenience you."

"You make a great mistake, Mr. Ryde," De Brest assured him eagerly. "It is the wealthy man who needs money most. I have my Bank to keep supplied. I have profitable business offered to me every day, but business which needs money."

"Nevertheless," Thomas Ryde rejoined, "you can afford to wait.... As for you, Mr. Hartley Wright, I know nothing of your financial position but I understand that you have several valuable agencies, and I imagine that you are making a very reasonable income. Be content with it for a few months longer. Believe me, it is worth while. Even if that unfortunate little accident with Rentoul and the watchman had not occurred, it would still have been unwise for us to disclose our hand too precipitately. You can be sure, as soon as it leaks out that the Boothroyd formula was part of the proceeds of that burglary—and it will leak out before many weeks are past—there isn't one of the great firms in the world who won't be trying to get into touch with us."

There was a depressed and sullen silence. Thomas Ryde was in the unpopular position of one who has convinced his companions against their wills.

"How do you suppose," Doctor Hisedale asked presently, "it will become known that the Boothroyd formula has been stolen? The firm themselves are not likely to advertise the fact. There hasn't been a word in the papers up till now to even suggest such a thing."

Thomas Ryde smiled.

"I will tell you how it will get about," he said. "It will get about because Boothroyds will not be able to turn out their goods without the formula. The market will become flooded with indifferent material. It won't take the commercial world long to find out its source, especially as I have the handling of all their wastes and am, in fact, the sole London agent for their irregular goods. It certainly won't take the shrewd buyers much longer to find out the reason for it."

"They have a very clever chemist up there," Doctor Hisedale meditated—"a brother-in-law of Rentoul's, I believe he was."

"They have a very clever man indeed," Ryde agreed, "but remember what I told you when I brought you all into this enterprise. Old man Boothroyd—Lord Dutley when he died—was one of the narrowest and most pig-headed old men who ever breathed. He never trusted any one but Rentoul. Sir Matthew Parkinson, for instance, the Managing Director of Boothroyds to-day, knows no more about the proportions, the chemicals used, or any of the finer points of the manufacture than I do. Each department works separately, and it was the formula, and the formula only, which brought them together. Therefore, they are going to commence now a period of experimenting which will cost them millions and whatever measure of success they may attain, they will never turn out the Boothroyd art silks in the proper style until they get the formula back."

There was a brief interlude of disjointed remarks, staccato-like exclamations piercing the blanket of an uneasy silence. De Brest moved to the sideboard, and came back with a cigar in his mouth.

"I do not like this business of waiting," he declared, "any more than the rest of you, but I think that there is much common sense in what Mr. Ryde has said. One has the stock markets, too," he added. "There should be money to be made there. We might arrange a pool to 'bear' the shares."

"Ryde may know what he's talking about," Hartley Wright acknowledged glumly, "but there's one point he hasn't touched upon which seems to me pretty important. You want us to wait for three, or even six months, Ryde? Who the hell's going to take charge of the formula for that time?"

"Ah!" Mr. Ryde murmured. "I imagined we would come to that."

"You bet," was the terse rejoinder. "You don't trust me; I don't trust you. I want to know what you're going to do with the formula before I stir out of this burg."

"The packet has been quite safe with me during the last ten days," Thomas Ryde pointed out.

"Yes, but you don't suppose we've been trusting you, do you?" the other snarled. "You must think we're some sort of mugs. It's cost us a fiver each a week to have you shadowed—but we've done it—Hisedale, the Baron and I between us. We've had a private bull lagging you since the day we arrived in London. You can put that in your pipe and smoke it. We're no more willing to trust you than you are to trust us. Now what are you going to do about it?"

"There is an old-fashioned way," Thomas Ryde suggested gently, his hands seeming to linger about his pocket, "of settling such a matter. The formula is in my possession at the present moment. Would you like to fight for it?"

A tense and ugly silence ensued. Thomas Ryde's chair was a little withdrawn from the table, and from behind his gold-rimmed spectacles, his eyes shone like diamonds. Perhaps none of the four men were utter cowards but there was not one of them to whom there did not come at that moment a little thrill of horrified memory, whose spine did not run cold at the thought of that still, emotionless figure dealing out death twice within the space of a few minutes with quiet and dexterous brutality.

"Damned silly line of talk that," Hartley Wright grumbled.

"It is not necessary for us to quarrel," De Brest insisted. "There is enough for all of us."

"Exactly my view," Thomas Ryde affirmed, in his even, penetrating tone. "You say that you have had me watched. You haven't, during these last ten days, noticed that I have been paying visits to financiers or manufacturers?"

"No one is accusing you of that, or anything else," Doctor Hisedale declared, in the voice of a would-be pacificator. "Your movements have been perfectly regular. At the same time, I must admit that the question of the disposal of the formula presents to me, as to my friend Mr. Hartley Wright, difficulties—very considerable difficulties. Many honest men have been tempted by the prospect of becoming a millionaire."

Thomas Ryde rose to his feet.

"Very well," he agreed, "let us accept the principle of mutual distrust. Meet me at two o'clock to-morrow afternoon in the smoke room of the Cannon Street Hotel, and I will put before you a plan for the safe custody of the formula which I think will be satisfactory to every one. At two o'clock in the smoke room of the Cannon Street Hotel."

"We'll hear the scheme at any rate," Hartley Wright conceded grudgingly. "I don't pledge my word to consent to it."

"You'll consent to whatever the others agree to," was the curt retort. "Gentlemen, I live some distance out and I am not accustomed to late hours. I shall take my leave. Doctor Hisedale, I thank you for your hospitality. In this atmosphere of mutual suspicion, to shake hands would be hypocrisy. Until two o'clock to-morrow in the smoke room of the Cannon Street Hotel."

With which Mr. Thomas Ryde, unruffled and tranquil, took his leave. The banquet was at an end.

ON the afternoon following Doctor Hisedale's somewhat peculiar dinner party at the Milan Hotel, Mr. Henry Hogg, Manager of the International Safe Deposit Company, Queen Victoria Street, returned from his luncheon just before half-past two, entered his office by the private way, and rang for his secretary.

"Any callers or telephone messages, Skinner?" he enquired.

"There are five gentlemen waiting to see you, sir," the young man announced.

Mr. Hogg was somewhat startled. Five prospective clients so early in the afternoon was, to say the least of it, unusual.

"Send them here," he directed, "in the order of their arrival."

"They all came together, sir."

Mr. Hogg was more surprised than ever. He leaned back in his chair and looked at his secretary over the top of his pince-nez.

"What sort of people are they?" he demanded.

The young man appeared vague. The answer to the question required a little more imagination than he possessed.

"Ordinary city gentlemen, they might be, sir," he reported. "One of them has the look of an artist. He is untidy about the head and kind of nervous in his manner, and I should say another was an American."

"Well, show them in," Mr. Hogg enjoined—"that is, if they all want to come in."

"I rather fancy that they do, sir," his subordinate confided. "They are all sitting close together and once, when the bell rang, they all got up. It seems as though they don't want to lose sight of one another."

Mr. Hogg, considerably intrigued, waved his secretary towards the door, drew the plan of vacant safes towards him, and settled himself down in his chair. Presently there were footsteps outside and the door was thrown open.

"The five gentlemen, sir," Skinner announced.

They filed in one by one, and from the first, they gave Mr. Hogg the idea of men who were filled with distrust of one another. Doctor Hisedale led the way. Mr. Thomas Ryde, with a small packet under his arm, came next; flanking him were Mr. Huneybell and Mr. Hartley Wright; and bringing up the rear was De Brest, half a head taller than any one of them.

"Gentlemen," the Manager of the International Safe Deposit Company said, rising to his feet, "I understand that you wish to see me on business. I am sorry that I have not five chairs to offer you. Will you kindly dispose of yourselves as well as you can. What can I do for you?"

Mr. Thomas Ryde disclosed himself as spokesman. He adjusted his gold-rimmed spectacles firmly upon his nose, selected the most comfortable chair, and crossed his neatly trousered legs.

"We are sorry to inflict such a visitation upon you, sir," he apologised, "but the fact of it is that we are all equally interested in the business which has brought us here. Unfortunately, too, we all appear to be inspired with a profound mistrust of one another. That is the reason why we are all surrounding your desk. My name is Thomas Ryde. The gentleman on my right is Doctor Hisedale, whose name is probably known to you. Doctor Hisedale is a very celebrated scientist. Next to him is Mr. Huneybell, my assistant in a small business. Behind him, the Baron Sigismund de Brest, the well known Dutch banker and financier, and the gentleman beyond, who has seated himself between me and the door, is Mr. Hartley K. Wright."

Mr. Hogg acknowledged the introductions in courteous fashion.

"If, as you say, you are here on business," he observed, "am I to understand that you all wish to rent a safe?"

"We require only one," Mr. Ryde replied—"the strongest and best that you are able to offer us."

The Manager smiled indulgently.

"You probably know all about us," he said. "We are the one company in the world who is able to offer its clients perfect security. Our safes are all precisely the same, and any one of them is better than the safe of any other make in the world. There is no power on earth which nature or science has yet evolved which could open one of them when it is finally closed. They are, to be brief, invulnerable. Our system of watchmen, robot and human, our electric alarms—"

"Quite so," Mr. Ryde interrupted politely. "We have considered your announcements and your specifications, and we are all agreed that you are able to offer perfect security. Our trouble, however, which I shall presently disclose, lies in another direction. Let me first, if I may, ask you a question. Is it necessary to divulge the nature of any packet we leave with you?"

"Not in the least," Mr. Hogg assured him. "The only thing concerning which I must satisfy myself is that its contents are not of an explosive character."

"It will be necessary to open the package to decide that—" Doctor Hisedale intervened.

"Not at all. I can decide by the weight."

"Very well then," Thomas Ryde continued. "Here is our difficulty. We have, with one other, whom you have not seen, and to whom we will allude as Mr. X., become partners in a certain enterprise. We are almost strangers to one another, for the enterprise demanded varied gifts. Hence our little association. We succeeded. The treasure of which we have become possessed is worth a fortune to each one, but it is not immediately realisable. A key to the fortune lies in the package which I am embracing—a fact which you have doubtless already surmised."

"It seemed to me highly probable," Mr. Hogg admitted.

"Do not think too hardly of us, sir, but the result of our labours is worth a million pounds, taking it at a very low valuation. Now, I ask you, is this mutual mistrust altogether inexplicable? Are there any four or five average men who could be brought together in any walk of life who would be willing to trust each other for the sixth part of a million pounds? I put the question to you for your consideration."

"I see your point," the other murmured. "To put it baldly, you can't make up your minds who is to be trusted with the key."

"You are amazingly right," was the prompt assent.

"You could each have a key if you liked," was Mr. Hogg's tentative suggestion.

A little ripple of mirth, half cynical, half genuine, flickered across the five intent faces.

"Which of us, do you fancy, sir," Thomas Ryde asked, "would sleep peacefully in his bed with the full knowledge that four others possessed the key to our treasure chamber, and that even at that moment the safe might be empty? We are human beings, Mr. Hogg, and we have already spoken of our mistrust of one another. Your suggestion does nothing to solve our difficulty."

"Have you thought out any way of dealing with it yourselves?"

"Roughly, this is my idea," Thomas Ryde explained, taking a sheet of business note paper from a rack upon the table. "You give us a formal receipt for our deposit, and hold the key of the safe here yourself. The receipt then should be torn into six pieces, two of which come to me—one for Mr. X. and one for myself—my friends here take the other four, and you should deliver up the key only when the receipt in toto, pasted together, or still in pieces, should be handed to you in its entirety."

Mr. Hogg deliberated for a few moments.

"It would not be necessary then for all of you to present the portions of the receipt in person?"

"Certainly not," Thomas Ryde replied. "Circumstances might, in any case, render that impracticable. One of us might be dead, in the hospital, or—er—in any other form of confinement. The only point, so far as you are concerned, is that the six original fragments of paper must be produced and recognised by you as constituting the original receipt. You then hand over the key, and your responsibilities are at an end."

Mr. Hogg leaned back in his chair and dangled his pince-nez by its cord. He had already made up his mind that the contents of the package probably consisted of spurious bank notes, or of jewelry forming the proceeds of some cunningly devised burglary. His own responsibilities in the matter, however, were not onerous and the letting of a safe was not an everyday affair.

"This is the most unique proposition which has ever been made to me," he confided. "I should like to know a little more about you, gentleman. A packet worth a million pounds is no light charge."

"On behalf of myself and my associates," Thomas Ryde admitted, "I will be frank. We are a company of adventurers."

There was a murmur of irritated and angry dissent, which the self-appointed confessor ignored.

"But," he continued, "more or less honest adventurers. We have risked everything we have in the world to obtain the contents of that package. My name, as I have told you, is Thomas Ryde. I have a commission agent's business in connection with the sale of yarns and artificial silks near Moorgate Street Station. I also consider myself an expert accountant, and I have been engaged at various times to conduct a campaign of economy in the office departments of certain firms whose expenses have been out of proportion to their profits. Mr. Huneybell, the gentleman on my left, who obstinately refuses the ministrations of a barber, is my clerk and town traveller in the business to which I first alluded. Doctor Hisedale is a famous scientist who is over here making a few final experiments in a London laboratory before he joins a firm of German manufacturers. Mr. Hartley Wright here is an American man of affairs of good standing. Finally, there is the Baron de Brest, whose name and position in the banking world should be sufficient guarantee for us. We are not men of straw, Mr. Hogg."

"Can I see the package?" that gentleman enquired.

His friends formed a little semicircle round Thomas Ryde as he deposited his burden, wrapped in brown paper and sealed in many places, upon the table. Mr. Hogg felt the weight of it speculatively and listened for a moment. It was not nearly heavy enough for an infernal machine and, so far as he could gather, contained nothing but papers. He decided that his first surmise with regard to its contents was correct.

"Very well, gentlemen," he agreed. "Our charge for the rent of a safe for three months—we do not let them for a shorter period—will be fifty pounds. If you will hand over the money, I will prepare you the official receipt."

Thomas Ryde produced ten five-pound notes, made a memorandum of the disbursement in his diary, and glanced through the document approvingly. He then laid it upon the table and rose to his feet.

"I shall now ask this last service of you, sir," he said. "Tear that sheet, if you please, into six pieces. Give me two and every one else one."

Mr. Hogg occupied himself in the manner desired, placed each fragment of the mutilated receipt in an envelope, and handed them over.

"I don't mind admitting," he said good-humouredly, "that I have had some strange clients, but I think you gentlemen are the strangest of all. If you will follow me, we will now deposit your treasure."

He touched a bell, and, escorted by a couple of burly-looking officials, who had more the appearance of prison warders than custodians of a civil undertaking, the five men were piloted to the subterranean quarters of the building. They passed through door after door of solid steel, each with a different type of lock, until they found themselves in a square apartment, even the floor of which was of some tempered metal. The safes were built into the wall all around and each had a number in luminous letters painted above it. Mr. Hogg paused before number 14 and inserted the key in a small lock.

"Listen, gentlemen," he enjoined, looking around.

He turned the key once. There was a hideous jangling of bells.

"At the present moment," he continued, standing with the key still in his hand, "a purple light is showing in the main office and in my own room. Now once more."

He turned the key again. The bells ceased, but a long, shrill whistle rang through the whole place. The door of the safe opened, the packet was deposited, and pandemonium ceased.

"You may rest convinced now, gentlemen," Mr. Hogg assured them, as he led the way to the lift, "that your million-pound deposit is as safe as human beings can make it."

He escorted his unusual clients to the light of day and watched them linger for a moment upon the threshold of the entrance hall. They were apparently men of unusual habits, for they indulged in no form of leave-taking, but all melted away in different directions. Mr. Ryde hailed a passing taxicab, and the Baron followed his example. Huneybell joined a little group who were waiting at the next corner for a bus. Doctor Hisedale, after a few seconds' hesitation, proceeded on foot towards the Embankment. Mr. Hartley K. Wright lurched steadily towards the City. The partnership was momentarily dissolved. Each member of it breathed a trifle more freely when he thought of that roll of papers reposing in the grim inaccessibility of Safe Deposit Box number 14.

CHARLES PHILIP BOOTHROYD, second Baron Dutley, still odoriferous of bath salts and shaving soap, fresh from the careful hands of his valet, left his dressing room, descended the curving stairway of his pleasant little bachelor Mayfair residence, and entered the library where his recently announced visitor was awaiting him.

"Awfully sorry to keep you waiting, Sir Matthew," he apologised. "I didn't get back from the Club until eight—just before you arrived, as a matter of fact—and one always meets such a lot of fellows when one's been away—pretty well a year, too, this time."

Sir Matthew Parkinson shook hands but made no immediate reply. Pleasantly large though the room was, it seemed almost cramped when he loomed up from his place, a towering, dignified figure, somehow portentous notwithstanding his forced smile of welcome. He was a tall, broad-shouldered Yorkshireman, six feet four at least in height, erect, with a broad, benevolent face, little patches of side whiskers, black streaked with grey, and a mouth which had puzzled every physiognomist who had studied it. "A fine-looking man", they called him in Leeds and all through the county, as indeed he was. At the head of his dining table, on the back of a hunter, presiding in the Board Room of Boothroyds over a meeting of his fellow directors, at any of those public functions to which duty continually took him, every one realised that Sir Matthew Parkinson upheld with dignity and distinction the great position which he had attained as head of the famous house of Boothroyd. It was true that Charles, the son of old Boothroyd, who had been raised to the peerage in the last year of his life, was still the titular Chairman of the Company, but it was Sir Matthew who was the life and soul of the firm. Dutley was an athlete himself, but by the side of his visitor he seemed almost insignificant in stature and weak in physiognomy.

"What will you have?" the latter demanded hospitably, with his finger upon the bell. "I'm terribly sorry to have to push off, but I'd no idea you were in town, and I have to be in Grosvenor Street in a few minutes. As a matter of fact, I've scarcely seen my fiancée yet and I'm dining there to-night."

Sir Matthew looked a little dazed. It was obvious that he had expected a different sort of reception.

"I will drink a glass of sherry," he rejoined, "and I will be as brief as possible. Nevertheless, it is serious business we have to discuss—and not business to be hurried over either."

A footman entered, to whom Dutley gave an order. Then he helped himself to a cigarette, pushed the box towards his visitor, and leaned against the mantelpiece.

"How's Grace?" he enquired.

"Grace is well enough. Discontented as usual, but all young people seem to be getting that way nowadays. She sent you the usual messages."

"And what's this serious business that you want to talk about?" Dutley asked, with a grimace.

Sir Matthew looked at his host reprovingly.

"Have you by chance looked at any of the letters I have written you since July?" he demanded.

Dutley was promptly apologetic.

"To tell you the truth, Sir Matthew," he confessed, "I haven't. When I left Abyssinia, which was in March, I wasn't at all sure how long it would take me to get clear of the country, or how I should come home. It depended what sort of a steamer I could catch, and it was just on the cards I might have had to go up to Khartoum to make some plans for next winter. We had a lot of sickness amongst the boys, too, crossing the desert, and that always throws you back. Anyhow, I sent home to say that they'd better hold all the letters. They'd only have missed me if they'd tried sending them on."

Sir Matthew was aghast.

"Great heavens!" he exclaimed. "Do you really mean to tell me that you haven't read a letter of mine for months?"

The young man pointed a little guiltily to the library table, upon which was stacked a huge pile of unopened correspondence.

"There they all are," he declared cheerfully. "Sorry if I've made a bloomer, but supposing I had read them, what difference could it make? If you've asked my advice about anything, my opinion wouldn't be worth a snap of the fingers. I'm only a figurehead in the concern anyway."

There was a brief silence, which even to Dutley seemed pregnant with sinister meaning. A log of wood broke off from the fire in the open grate. Taxicabs were all the time honking by. London seemed alive to the fact that this was the pleasant hour before dinner. The cocktails and sherry arrived and were duly served. Sir Matthew watched his glass filled but made no movement towards it. Dutley, on the other hand, drank off his cocktail and replenished his glass. The servants left the room.

"Come on," the younger man begged, with a glance at the clock. "Let's hear the worst."

"It is probably news to you," Sir Matthew confided slowly, "that there was a burglary at the Works three months ago."

"Heard something about it this afternoon," Dutley acknowledged. "The fellows at the Club were chaffing—seemed surprised that I could afford to buy them a drink. Got away with five thousand quid, didn't they?"

"They got away also," was the grave reply, "with something of far greater importance. They murdered poor old Rentoul, who was the only one of his chemists whom your father ever trusted, and they got away with Blunn's formula."

"I'm sorry about poor old Rentoul," Dutley said. "I remember the old boy quite well. What's Blunn's formula, though? It sounds familiar, but I can't exactly place it."

"It is the formula for the manufacture of artificial silk," Sir Matthew declared solemnly, "upon which your father built up the whole of his business—the formula which is responsible for the fortunes of the House of Boothroyd."

"The devil!" Dutley exclaimed, a little startled.

"The five or six thousand pounds," Sir Matthew went on, "wasn't worth thinking about. It didn't matter a snap of the fingers. The theft of those papers is nothing more nor less than a colossal disaster to the firm."

"But what on earth use is the formula to a gang of burglars?" Dutley demanded.

"They weren't ordinary burglars," was the portentous explanation. "It is my conviction that they came for the formula, and for nothing else. If they had been ordinary burglars, the Police would probably have had them before now. As it is, they haven't a single clue to work upon."

"Rotten!" Dutley murmured. "How are you getting on at the Works without the formula?"

"We aren't getting on," Sir Matthew groaned. "That's our trouble, as you'll find out when you read my letters. You'll have to try to grasp the situation, young man. It's serious enough, I can tell you. Your father, although I say it to his son, was one of the most obstinate men who ever breathed. He built up great works here and in Switzerland, in Germany and in France, in Italy, on the strength of a single extremely complicated formula. On the day of his death?"

"Yes, I remember that," Dutley interrupted, with a covert glance towards the clock. "He called you in, and me, and Stephenson, and Watherspoon. We all promised that the formula should be kept in the safe, and never copied."

"And we kept our word, worse luck!" Sir Matthew regretted bitterly. "Now we are paying for humouring a dying man's whim. Without the formula, we have been hopelessly at sea. Fortunately it doesn't matter quite so much abroad where we are mostly making by-products. Up in Marlingthorpe we're in the hell of a mess. We have been manufacturing on guesswork, and guessing wrong all the time. Our chemists have been working night and day. We've spent thousands on experiments and we're no nearer the real thing. Making silk indeed! We're making muck. We're nowhere near the right thing. Do you know what our shares stand at in the market to-day?"

"As a matter of fact, I do," the young man rejoined. "The Stock Exchange news came up when I was waiting on the tape to see whether Reggie Fulford had won the Guards' Steeplechase. About eighty, aren't they?"

"Yes, somewhere about that. Do you know what they're worth?"

"Don't know that I do," Dutley admitted. "Those Stock Exchange fellows generally hit it off about right though, don't they?"

"If the world knew the truth," Sir Matthew confided impressively, "they're worth somewhere about forty, and at that they'd be a speculation. I wouldn't buy them myself at the price."

All the light-hearted good nature faded from Charles Dutley's face. He set down his glass and stared at the speaker. There was no doubt about Sir Matthew's being in earnest. The fist of his great right hand was clenched so tightly that the veins stood out in deep blue cords as he banged the arm of his chair. In his excitement, the Yorkshire accent of his youth forced its way to the surface.

"Listen, lad," he continued, "we've sent out already five hundred thousand pounds' worth of rotten stock, and God knows the trouble it's going to lead us into. We've five hundred thousand pounds' worth more in the warehouse, and at the present moment our machinery, which is running at a cost of over five thousand pounds a day, is turning out material which, instead of being fit to sell at a fifteen to twenty per cent. profit is only fit for the cesspool."

There was another silence. Sir Matthew was breathing heavily. He took out his lavender-scented white cambric handkerchief and wiped his forehead. A pale streak had crept into Dutley's cheeks underneath the dark coat of sunburn. The words were there still, lingering in the air, words of hideous import, which might spell approaching ruin.

"My God, Sir Matthew," he exclaimed, "and I hadn't an idea!"

"How the hell could you have," Sir Matthew pointed out, "if you go and bury yourself in these outlandish countries, shooting animals which have never done you any harm, and never even taking the trouble to have your letters sent after you? What did it matter to you? You've been content with your princely income and your life of sport. Old Stephenson's on a trip round the world. Watherspoon is past his job, and all the time I've had to bear this alone. Every morning I've had to inspect the muck that's come out of the Works and pretend it's all right."

"Are there any signs," Dutley enquired, "of any one else having got hold of the formula?"

"That's the first sensible question you've asked," was the gruff response. "We've lost in round figures pretty well half a million in making filthy stock since the formula went, but there's no other firm that I can hear of who's improved its manufacture, or who's making the stuff we used to make. That's where there's a gleam of hope for us. We've got to get the formula back even if we pay for it."

"Why not offer a big reward?" Dutley suggested.

Sir Matthew scoffed.

"Ask the Police," he rejoined. "Any one who can lay his hands on that formula is likely enough to stand his trial for murder. Besides, we've managed to keep the thing secret so far. If the merest rumour of it gets round the Stock Exchange there'll be such a slump in Boothroyds as the City has never seen."

There was a discreet knock at the door. A servant presented himself.

"Mr. Ronald Bessiter has telephoned from Grosvenor Street, my lord. I was to remind you that they were expecting you there for dinner. It's already twenty minutes to nine."

Dutley nodded, and dismissed the man.

"When can I see you to-morrow, Sir Matthew?" he asked anxiously.

"As early as possible. I don't suppose you can help any more than any other man could, but I must have some one to share the responsibility. What about quite early—say eight o'clock?"

"Suit me all right," Dutley assented. "Come round here and have a spot of bacon and eggs. I'm sorry to have to hurry away. I'd cancel the dinner, only it's with my prospective father-in-law, and I expect I shall get it in the neck as it is. Burdett will look after you—get you another glass of sherry if you'll have it."

The young man took swift leave of his visitor, and Sir Matthew rose heavily to his feet. He lingered for a moment on his way to the door, his eyes fixed upon that enormous, still unopened heap of correspondence. He was by no means a visionary, but there seemed to him something a little allegorical in that sublime indifference to passing events which such an accumulated mass denoted. He thought of old Boothroyd, seated at his desk at half-past eight every morning, an envelope opener in his hand. One—two—three. Private letters on the left, business letters on the right, envelopes and circular appeals into the waste-paper basket.... The butler entered the room quietly.

"I have called a taxi for you, Sir Matthew," he announced. "May I offer you another glass of sherry?"

Sir Matthew pulled himself together.

"No thanks. Tell his lordship that I shall be here punctually at eight o'clock to-morrow morning," he said, as he took his departure.

"WHAT made you so late, Charles?" Lucille Bessiter asked her fiancé, as he sat on the arm of her chair about a quarter of an hour later.

"A man I simply couldn't send away came to see me at the last moment," he explained—"old Sir Matthew Parkinson who runs our show up in Yorkshire. I'm terribly sorry. I'm afraid your mother's angry with me."

"She'll get over it," Lucille predicted. "I didn't know they ever bothered you about the business."

"They don't, as a rule," he admitted. "This was something rather exceptional. I say, who is the tall young fellow, looks like a foreigner, who was talking to you so earnestly when I came in? He's been glowering at me ever since."

"That is a very important person," she confided. "His name is the Baron de Brest, and he's a Dutch financier and banker. He's a client of the firm, or going to become one."

"Is he?" Dutley muttered. "Well, I don't like the fellow."

Lucille arched her fine eyebrows.

"Why, you don't know him!"

"And I hope I never shall."

The girl laughed, but her frown deepened a little.

"You certainly will," she said. "During your extremely protracted and tactless absence, he has been my chief consoler."

"Well, he's out of a job," Dutley declared.

Lucille eyed her fiancé speculatively.

"You take a good deal for granted."

"Too much?"

"That depends. What are you doing to-morrow morning?"

He indulged in a little grimace.

"Interviewing Sir Matthew, and opening my letters."

"I'll come and go through them for you," she promised. "I've always wondered what the correspondence of a millionaire was like."

"I'm not quite so sure that Charles is a millionaire," her brother, a very smart young man and a shining light on the Stock Exchange, remarked. "His shares dropped a quarter this afternoon, and finished weak. You will probably read to-morrow morning in the financial column of the Times that it was due to profit-taking, but one never knows. They may have heard that you're back, Charles, and that you're thinking of going into the business."

"If I should consider doing such a thing," Dutley observed, with dignity, "there would probably be a boom in the shares, not a fall. I don't think, Lucille," he complained, "that your family supports my interests strongly enough."

"Can't say that for the head of the firm," Mr. Bessiter remarked, from the other end of the room. "There was a little chap, an occasional client of ours, in a few days ago, talked of opening a 'bear' account against Boothroyds from the first of the month. I strongly advised him to do nothing of the sort—told him, in fact, we wouldn't consider it on a margin. He left without doing business. That's what I call supporting the credit of the family."

Mrs. Bessiter, good-hearted, charming, a very distinguished figure in her world, and a very popular woman, broke off in her conversation with a well-known diplomat.

"I'm not quite sure about Charles ever belonging to the family," she intervened. "These long absences in barbarous countries are very dangerous things. I think that Lucille is becoming dissatisfied, and I am not sure that I blame her. I am quite convinced, although she is my own daughter, that she is the sort of girl who requires a stay-at-home fiancé."

"Lucky for me, I've often thought," her husband reflected, "that I was a home bird myself."

"A most uncalled-for speech," was his wife's severe retort. "If I go to Cannes, even for a month, I come back in three weeks."

The announcement of dinner interrupted the badinage. Dutley found himself between his fiancée, and a grave-faced, bespectacled, elderly gentleman, whose name he had not caught.

"Couldn't get my numbers right to-night," Mrs. Bessiter apologised, from the end of the table. "Anyway, I thought that Charles, if he had the faintest sense of duty, would neglect his other neighbour to talk to Lucille, so I didn't worry about getting another woman."

"I regret," the elderly gentleman said, with a courteous inclination of the head, "that I am to be neglected, because I find much pleasure and interest in meeting Lord Dutley. I am, in a sense, a competitor of your firm's," he added.

"Is that so?" Dutley murmured politely. "I am afraid I didn't catch your name."

"My name is Hisedale—Doctor Hisedale. I am connected with the German company of Meyers of Offenbach. Just now, however, I am over here to make experiments at a friend's laboratory. Yours is the envied firm of the world, Lord Dutley."

"I'm afraid that I don't know as much about it as I ought to," was the frank reply. "I only went into the business for a year or two. I chucked it for the war, and never went back again."

"You are still Managing Director, though, I understand."

"Well, I am Chairman of the Directors," Dutley acknowledged. "That is simply because of my holding of shares. I turn up once a year, and address the shareholders."

"Amidst scenes of wild excitement," Lucille put in, "when the dividend is large enough. When it isn't, they boo."

"Boothroyds' dividend," Doctor Hisedale said, with a smile, "is usually large enough to satisfy the most exacting shareholder. We look upon your people, sir," he continued, "as the most favoured in the world. You—or rather the chemists whom your illustrious father was clever enough to discover—have inaugurated a new industry. We all grope in the darkness whilst you triumph."

Dutley sipped his champagne. It seemed an odd co-incidence that he should have a conversation of this sort forced upon him.

"I wish I knew more about it," he confessed. "You should come up and have a look at our Works, and meet Sir Matthew Parkinson, Doctor."

The latter smiled—a thin smile of derision.

"I have met your Sir Matthew Parkinson," he confided. "I do not fancy that if I visited your Works I should learn very much. He is one of those magnificent Yorkshiremen who knows how to keep his mouth very tightly closed. Indeed, why not? In Germany we work, too, with locked doors. The preservation of our secrets is the measure of our commercial success."

Lucille leaned forward with a little pout.

"Do you know that you are poaching, Doctor Hisedale?" she complained. "This is my fiancé, whom I have not seen for many months until this morning."

"I apologise," the scientist said solemnly, turning to his neighbour on the other side. "You will take pity on me, Mrs. Saunderson. You will tell me what theatres a foreigner who has not many friends in England should visit."

Lucille laughed softly up at her companion.

"Poor dear!" she murmured. "How all this talk of business does bore you, doesn't it? And what a good thing it is you don't have to earn your own living."

"Supposing I had to," he speculated.

"You may have some gift for stuffing wild animals. They tell me that is quite a profession. Or perhaps, if you are as good with a shotgun as they say you are with a rifle, you could earn a little by going about to country houses in the season, shooting their game for them. Otherwise, old dear, I'm afraid your chances would be a little vague. Passionately attached though I am to you, I am not at all sure that I would entrust myself, with my love of creature comforts, to your efforts."

Dutley laid down his knife and fork.

"I knew it," he groaned. "You're marrying me for my money."

"Of course I'm marrying you for your money," she agreed. "You'll never be able to take care of it unless you have some one like me to do it for you. Nevertheless, it may have occurred to you sometimes, in your moments of bloated arrogance, that I am rather well off myself."

"That is good news," he declared. "I sha'n't have to make you an allowance, or settlements, or anything of that sort."

"Oh, won't you?" she scoffed. "Dad will see to that, I can promise you. Dad, how much do you think Charles ought to settle on me? We thought of going in to see the lawyers together next week."

Mr. Bessiter knew his daughter well, but he was a man of some dignity, with the gift of reticence, and he was a little shocked.

"These things, my dear," he told her, "are not discussed at even a friendly dinner table."

"Snubbed," she sighed, under her breath. "Nevertheless, I warn you, that I shall insist upon settlements."

"We'll go into it and see how much I have to settle," Dutley promised her. "I don't like that little chap going to your father's office and wanting to open a 'bear' account against us. My knowledge of Stock Exchange affairs is limited, but I imagine that he's laying the odds against our prosperity, or something of the sort."

"Admirably put," Baron de Brest declared, from the other side of the table, with a little bow. "Lord Dutley will end by being a business man, I am sure."

Doctor Hisedale's florid eyebrows were slightly contracted.

"Did I understand," he asked, "that some man has been imprudent enough to suggest opening a 'bear' account against Boothroyds?"

"Happened only a few days ago," Dutley assured him. "What with that, and the quarter drop in my shares, owing to profit-taking, whatever that may mean, I am not sure that I shall be able to afford to get married this year."

"We get married before Christmas," Lucille said firmly, "or not at all. I have arrived at that dangerous age between flapperdom and young womanhood when I need a guiding hand, constant attentions, and flowers every morning. A lover in Abyssinia is not of the slightest use to me."

"Almost as bad," her mother mused, "as a husband who is in the City all day."

"How modern our elders get!" Lucille sighed.

"Baron," Mrs. Bessiter continued, with a glance at the frown on his face, "I really am afraid that you must be shocked at my daughter's levity. When you discuss us in your own country, please don't believe that all our young women are like this. They are not, I can assure you. Lucille was always, unfortunately, brought up with her brothers, and you know what that means—either a touch of the hoyden, or a step in front of her generation."

"Something ought to be done about Mother," Lucille declared.