RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

"The Court of St. Simon," Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1912

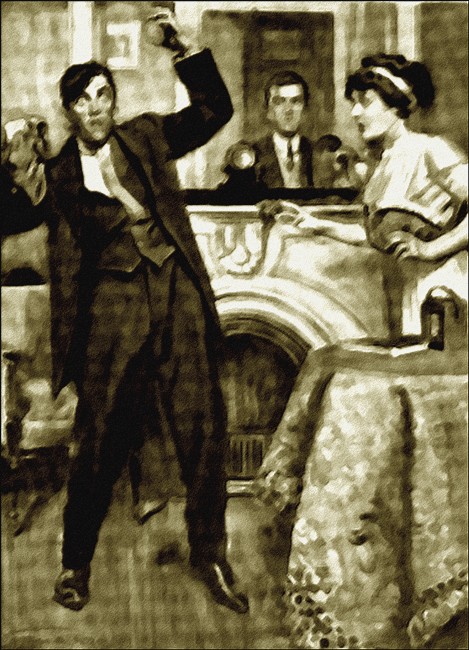

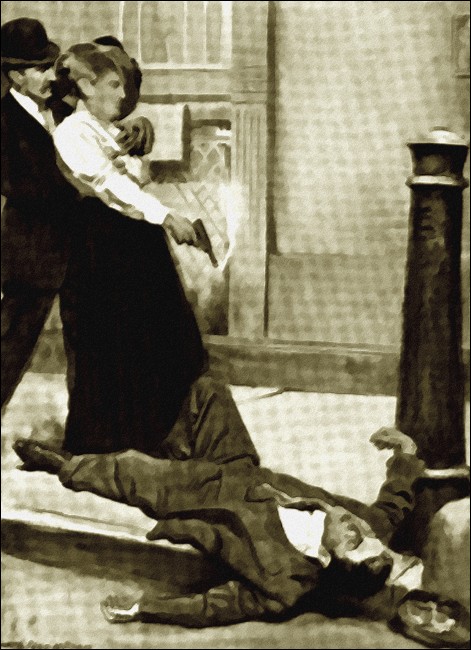

Frontispiece

"You had no right to come here," he said curtly.

THE boy was without doubt inclined towards affectation, yet there was also something of truth, a shadow of honest dejection, in the weariness of his restless eyes. Here, where pleasure had become a science, he sat among the midnight revellers, alone and unamused, flaunting his ennui with something of the self-consciousness to which his years entitled him.

"A type," one murmured, glancing in his direction. "Behold the young Frenchman, a man before he has left the nursery, a man in experience and evil knowledge, worn out with pleasure before he has had time to be young!"

A type beyond a doubt. Eugène d'Argminac—it was name which he had appropriated, for he was really an Englishman—was good-looking notwithstanding his pallid face, slim, and well-built. He was dressed in the somewhat extravagant mode affected by the young Frenchman of fashion, but with all that delicate, almost feminine care about details which excuses even foppishness. The droop of his white tie, the stones in his studs and links, his single ring, his soft-fronted white shirt, were all exactly in the fashion of the moment. But for his eyes, which were distinctly narrow and set too close together, and the unwholesome air of fatigue with which he looked out upon the gay scene from his table against the wall, he was a not unattractive figure.

It was the supper place of the moment—Paris has many such which appear and disappear in rapid succession. Every table was occupied save one or two in the best part of the room, reserved for any visitor of distinction who might appear unexpectedly. The usual attractions were in full swing. A Spanish girl, with black hair and a yellow gown covered with sequins, was dancing, a rose in her mouth. A busy orchestra found it harder work even than usual to make their music heard above the clamor of voices, the popping of corks, and the rattle of crockery. Toy balloons bearing the name of the restaurant were floating from every table. Every one who was not laughing seemed to be talking. The boy, who sat with a plate of biscuits and a bottle of champagne before him, neither of which he had as yet touched, beckoned to the presiding genius of the place.

"Monsieur Albert," he said gloomily, "it is finished here. One amuses one's self no longer. Already the world is prepared to move on to the next place. Mark my words, your reign is over."

The popular maître d'hôtel, a little staggered, for he was more used to compliments, extended his hands towards the over-crowded room; pointed, also, to the visitors waiting for tables, who thronged the doorway.

"But, Monsieur," he protested, "never has the rush been so great. Out there I dare not show myself. There are a dozen who wish tables —English, American, Russian. From all quarters of the world they come to my café. Finished! Mon Dieu! Monsieur cannot be serious."

The young man yawned. "You have the numbers, it is true, dear Albert," he admitted, "but the quality! Saw one ever such a rabble—Tourists, the bourgeoisie of the country towns, shop people from the boulevards, scarcely a person of distinction or interest. How can one amuse one's self among such?"

Monsieur Albert smiled tolerantly. "Monsieur is ennuyé this evening. Another time he will amuse himself well enough here. One cannot pick and choose one's clients, but there are many here of the distinguished world. Over in the corner there is a Russian Prince—he does not like to be talked about, but his name is in all the papers. Fourget, the great actor, sits behind with Mademoiselle Lalage, who created the part of Cléopâtre. The gentleman with the red ribbon in his buttonhole there is Monsieur d'Anvers, who wrote the play."

The boy half closed his eyes. "All the usual claptrap," he murmured. "A Russian prince, a dancer, a dramatist, and an actress. One meets them everywhere at every turn. These are blackberries upon the tree of life here, Albert. Show me, indeed, some one of real notoriety, some one out of the common; show me one single person not of this type."

Monsieur Albert's face was turned toward the door. He gave a sudden start. "But indeed, Monsieur, you may soon be gratified!" he exclaimed. "Wait but a little. I return."

It was Albert at his best who moved toward the entrance, Albert at his best who stood bowing before these two newcomers, who with his own hands removed the cloak from the girl's beautiful shoulders, who himself led the way to the best table the place afforded, moving backward most of the time, talking always in his most impressive manner. Even the young man who called himself Eugène d'Argminac lost for a moment his look of weariness. They were strangers to him, these two, and they were certainly people of marked and unusual distinction. He watched them as they settled themselves into their places. The man was apparently about forty years old, but his exact age it would have been hard to tell. He was inclined to be fair, with a great deal of deep brown hair carefully brushed back from his forehead. His mouth was strong and prominent, a trifle cruel and yet not sensual. There were little lines about his eyes as though he were short-sighted, and the eyeglass which hung from a ribbon about his neck was evidently not for ornament alone. His forehead was good, his face like his frame—long and thin. He looked like a man who had been an athlete and who was still possessed of great strength; a man of breeding, without a doubt. The girl was dark, colorless, as were so many young Parisiennes, powdered, indeed, almost to the dead whiteness of the ladies of Spain. Her eyes were soft and velvety, her eyebrows silken lines, her lips thin streaks of scarlet. A magnificent rope of pearls hung from her neck, and she carried a gold bag set with emeralds. She sat down, calmly contemplating herself through a tiny mirror, a powder puff in her other hand ready for use. Eugène d'Argminac yawned no longer in his corner. He waited almost eagerly for the moment when Albert at last, after a long consultation with a maître d'hôtel, a waiter and a wine steward, left their table. Then he leaned forward and summoned him.

"Monsieur Albert!" he cried.

Albert, with a little triumphant smile, obeyed the summons. "Voilà, Monsieur!" he declared. "There are two of my clients whom I think you will not call commonplace. They are different from the others, are they not?"

"Who are they?"

Monsieur Albert smiled. "If one knew their names, Monsieur, if one could tell who they were or what place they occupied in the world, they would perhaps lose something of their interest. Is it not so? Supposing, for instance, the gentleman were a wine merchant, and the lady a manikin!"

"You know very well that they are nothing of the sort," Eugène protested. "Tell me their names, tell me all you know about them."

Albert made a little gesture of despair. "If only one could tell!" he murmured. "The gentleman calls himself simply Monsieur Simon. He speaks of the lady as his sister. That, however, one is permitted to doubt. They have been coming here now for nearly five months."

"Monsieur Simon—but that is rubbish!" the boy exclaimed. "They are people of account, these. Even if they come here incognito they must have a name and standing elsewhere. You are so clever at these things, Albert. I thought that you made it a point to know the names and standing of most of your regular customers. Surely you have discovered something more about them?"

Albert accepted a cigarette from the gold case of his patron, and leaned across the table. "Monsieur d'Argminac," he said, "I will admit that I have tried to discover who and what they are, these two people, seemingly so rich, certainly so distinguished. I have failed—I admit it—I have failed. We have people about the place, as you know, who are quite willing, for a consideration, to undertake a little espionage. For the sake of curiosity I had these two followed one night. The fellow was caught and beaten, beaten in the open streets by Monsieur there. Since then I have made no effort. Once or twice I have had visitors here who seemed about to claim acquaintance with the gentleman. Always he looks as though he wore a mask. He recognizes no one. I have tried questions, but never have I learned anything for my pains. At present I am content. They are good clients, they excite curiosity, it is a joy to look upon Mademoiselle. I keep my counsel."

"I should like to know them," D'Argminac remarked.

Monsieur Albert shook his head doubtfully. "They make no acquaintances," he said. "I have never seen them speak to a soul."

"Is Mademoiselle also as unapproachable?" D'Argminac asked.

"Absolutely," Albert replied. "And, Monsieur d'Argminac," he added under his breath, "let me have your attention for one moment. Here there are times, on gay nights like this, or towards the time when one leaves, when introductions are dispensed with. A man of fashion like yourself flirts always with the beautiful women. Forgive me if I drop a hint. There was a young man once who tried to flirt with Mademoiselle. He would have slipped a note into her hand. Monsieur observed him. It was all over in a moment, but he is a man of mighty strength. He threw the young gentleman across two tables, caught him up as you or I might a baby. Since then no one has looked at the young lady."

D'Argminac smiled. "Your story inspires me with fear, Albert," he declared. "I tremble and I obey. Nevertheless, the coming here of these two people pleases me. I shall remain a little longer. You have shown me some thing, at least, which it does not weary one to look at."

The monotonous round of gayety rose and fell. More women danced, a negro sang coon songs for the benefit of the Americans. Two Russian dancers, squatting almost on their haunches, went through their ungraceful evolutions. Monsieur Albert walked about, surveying the room with the air of an emperor. He laughed to himself as he thought of the words of his youthful client. Finished, indeed! The café was at the height of its prosperity. There was no such scene as this in all Paris. Suddenly, in the midst of his wanderings, he caught the eye of the patron whom he knew as Monsieur Simon, and obeyed in a moment his commanding summons. Eugène d'Argminac watched their whispered conversation eagerly. Somehow or other he began to believe that he himself was concerned in it. Assuredly Albert had once turned half round and glanced towards him. The face of Monsieur was wholly inscrutable. Only his lips moved, but once his eyes had looked in the direction which Albert had indicated. Eugène d'Argminac was delighted with himself and with the entire evening. After all, then, he was not absolutely past emotions. He had certainly felt his pulses beat a little quicker at the thought that he might be the subject of their conversation.

Presently Albert, leaving his patron with a most respectful bow, came hurrying across the room toward D'Argminac's table. "Monsieur d'Argminac," he announced, "you have indeed the good fortune. The gentleman in whom you are so much interested, and who so seldom asks questions concerning any one, has just been speaking to me about you."

"What did he say?"

"He asked me your name, who you were, why you sat there alone looking so bored and so weary."

"And you? What did you answer?" D'Argminac asked softly.

"I told him what I knew—that you were a young gentleman of fashion and perceptions who came here most evenings, but who was inclined to find the place dull. He said that he would like to know you. I am at liberty, if you will, to conduct you to his table."

Eugène d'Argminac rose slowly to his feet. For a moment he had hesitated. He could not refuse this invitation brought him so triumphantly, yet some part of his magnificent self-confidence seemed to have deserted him as he crossed the floor.

Albert performed the introduction with much ceremony.

"Monsieur," he said, "and Mademoiselle, I have the great honor to present to you Monsieur Eugène d'Argminac, one of my most esteemed clients."

D'Argminac smiled faintly. "Albert has many a better one," he said. "As a matter of fact, he is not pleased with me to-night, for I have told him that this place grows wearisome."

"You will take a glass of wine with us, Monsieur d'Argminac?" the man at the table asked. "Pray seat yourself."

D'Argminac drew a chair towards him. "With Mademoiselle's permission," he replied, bowing to her, "it will give me much pleasure to join you for a few minutes."

THE conversation was almost entirely confined to the two men. Mademoiselle murmured only a few words, and even then D'Argminac was puzzled. She spoke slowly and with much care. The words were correct so far as they went, yet something in their intonation made it very obvious that these two did not belong to the same social station, notwithstanding Albert's statement as to their relationship. For the rest, Mademoiselle took very little notice of this new acquaintance. She was entirely occupied in enjoying an excellent supper. Her two companions ate nothing.

"Our much respected friend Albert," remarked Monsieur Simon, "spoke of you as being the only one of its habitués who found this place wearisome. I must confess that I was interested. You are—pardon me—young, Monsieur d'Argminac, to have exhausted the gaieties of this wonderful city."

The boy felt for his as yet invisible moustache. The faint irony of the other's tone was entirely lost upon him.

"I am perhaps older than I look, Monsieur, Still, a year or two at these places is enough. They are all the same—the dance, the women, the music. There is nothing left."

"You have many friends in Paris?" Monsieur Simon asked.

"I am fairly well known here," the young man answered. "You wonder, perhaps, that I should care to come to such a place alone. It is simply a whim of mine. I have many acquaintances, at any rate."

"Your name is French," Monsieur Simon remarked, "but you are surely English, are you not?"

D'Argminac admitted the fact a little reluctantly. "I was educated in England at Eton, but I prefer the French people and their manner of living. After all, though," he added wearily, "I am not sure that it is any better here than anywhere else. I found London insupportable, but I am not sure that Paris is much better."

Monsieur Simon laughed softly. There was a cynical droop to his lips as he leaned forward and lit a cigarette.

"When one is weary of Paris at your age," he declared, "one must be possessed, indeed, of an original temperament."

"It is a curse," Eugène d'Argminac admitted gloomily. "If one seeks contentment, one should resign oneself to be commonplace."

"You still feel the desire for excitement, I suppose?"

"I would buy it, if I could, at any price."

"You have tried sport?" Monsieur Simon asked. "Polo, for instance, or hunting? Your English blood should serve you there."

D'Argminac shook his head. "Sport does not attract me in the least. I cannot play games, because they do not amuse me. I have driven an automobile for a month. It was a joy to me, but it passes."

"You are destined, perhaps, for one of the professions, or the diplomatic service? Sometimes the necessary work gives a stimulus to life."

"Very likely," D'Argminac assented. "I can only say that for my part I have never felt the slightest desire to take life seriously."

The eyes of Monsieur Simon twinkled. Again he smiled. Mademoiselle glanced at him a little curiously. It was strange to her that he should find so much to interest him in this sulky-looking boy.

"Yours is indeed a hard position," he declared, "but then you are doubtless a singular person. It is unusual, is it not, to find a solitary man at such a Temple of Venus?"

Eugène d'Argminac glanced towards Mademoiselle. It was an impulse which he could not repress. He remembered afterwards Albert's warning and trusted that his glance had been unobserved.

"With a companion," he said, "I bore myself most completely. Adventures —perhaps! One must have adventures in Paris to be in the fashion at all," he continued, feeling again for his moustache, "but there is a sameness about them all. One has a few moments of excitement and then a great revulsion, a complete disillusionment. I brought Mademoiselle Vincelly here, the other evening, from the Folies Bergères. She ate lobster with her fingers and demanded beer."

Mademoiselle for the first time smiled at him ever so faintly—not a particularly gracious smile, but at least it was something that she should take notice of his existence. "Mademoiselle Vincelly is, after all, a German," she declared. "There are very many beautiful young ladies in Paris."

"It is true, Mademoiselle," D'Argminac admitted. "I begin to fear that the fault is with myself. I have not the gift of susceptibility. I call it a gift because I think that it is the most delightful thing in the world," he added, with a little sigh, "to fall in love. When I was younger it was my favorite pastime."

Mademoiselle looked at him, and throwing her head back laughed frankly, showing all her wonderful white teeth, which gleamed like pearls. Her companion smiled, too, in quieter and subtler fashion. He had been right. It was amusing to listen to this strange youth.

"None of us should relinquish hope, my friend," he said, with gentle irony. "You are not too old, even now, to feel once more the gentle passion."

D'Argminac remained entirely unconscious of the fact that he was being skilfully exploited for the amusement of these two people. "Perhaps you are right," he agreed. "Very likely, even now, that will happen. All I can say is that I am here, I am willing, if it comes I should be glad. In the meantime, life remains insupportable. It is only the very old or the very young who are attracted by this sort of place. I hope that I am not conceited, but I need more to excite me. I do not think," he added, "that you, Monsieur, can find any real pleasure in sitting here among such a crowd, in floating toy balloons and listening to this babel. You find no excitement here. Tell me, am I not right?"

"To some extent you are," the older man confessed. "Still, so far as I am concerned, Mademoiselle my sister and I, we come here as a rest. If we seek excitement, we seek it elsewhere and in a different fashion."

D'Argminac tapped a cigarette upon the table preparatory to lighting it. "You have asked me a good many questions," he said slowly. "I have no secrets from you or any one who interests me. It is amusing, I think, to exchange confidences as regards life with people of one's own order whom one meets even so casually as we have met. You say that when you seek excitement you seek it elsewhere and in a different fashion. You look to me as though you would be critical. Tell me how and where you seek it!"

The man who was known as Monsieur Simon leaned back in his chair and looked at his questioner thoughtfully. D'Argminac returned his gaze almost eagerly. Already the boy had begun to feel the fascination of his manner. Whoever he might be, he was distinctly a remarkable man. There was strength in his face, domination in his tone, he had not a single bad feature. D'Argminac felt the mesmerism of a stronger and commanding nature.

"Is that a serious question?" Monsieur Simon asked.

"Absolutely," D'Argminac replied eagerly.

Monsieur Simon turned to his companion. "It is a challenge," he remarked. "Shall we show him? What do you say?"

The girl shrugged her shoulders. It was obvious that she disapproved. "You will do as you wish, I suppose. You do always the rash things."

"Very well, then," said Monsieur Simon, "you shall learn our secret, if you will. Presently we will show you how we two, Mademoiselle and I, escape for a little while from the sameness of a dull existence. You need not be afraid," he continued, smiling, "that you will be asked to gamble; you will not even need your pocket-book at all."

The boy flushed. It was absurd to be read like this! Notwithstanding his immense admiration for this distinguished couple, an admiration which would have rendered him, if necessary, a willing victim had they really had designs upon him, it was a fact that some such thought as Monsieur Simon's words indicated had been crossing his brain at that precise moment. His protest, however, was voluble and emphatic enough.

"No one could have associated such a thought with your charming offer, Monsieur," he declared, "certainly not I."

"You think that you dare trust yourself with us, then?"

"I shall be overjoyed to follow wherever you and Mademoiselle will lead," said the boy. "If you can show me anything new in this city," he added, smiling a little doubtfully, "I shall be glad as well as surprised."

"There is nothing new," Monsieur Simon admitted. "Some things, however, don't occur to one unless they are pointed out. At three o'clock, then, if it pleases you, we will leave this place together."

AT three o'clock precisely, Monsieur Simon and his companion, followed by the younger man, left the restaurant.

"My automobile is here if you and Mademoiselle will honor me," the latter remarked, as they stood upon the pavement.

Monsieur Simon shook his head. "If you do not mind," he said, "I will ask you to send yours away. It is better that you come with us."

The young man hesitated. "Do you mean send it away altogether? How about afterwards? Shall I not require it to take me home?"

"We will arrange that," said Monsieur Simon. "Come."

The younger man did as he was bidden, and the three entered a large and remarkably handsome car which was already waiting. Monsieur Simon said but a single word to the chauffeur as they stepped in. D'Argminac sank back in his easy-chair and looked around him with admiration. The upholstering was all white. A soft white rug was upon the floor, and many footstools. There was a table with some books and flowers, an electric shaded lamp.

"No wonder you prefer your own automobile," the boy declared. "Mine is no better than a taxicab compared with this."

Monsieur Simon smiled but said nothing. The car was turned swiftly round, and to D'Argminac's surprise they did not descend the hill. He was beginning now to feel slightly curious.

"We do not descend into Paris, then?" Monsieur Simon shook his head. "We make a call close by," he announced. "After that it is as may be. We shall see."

They drove at a great pace into a quarter of Paris utterly unknown to D'Argminac. Presently they turned off a broad but shabby boulevard into a narrow, ill-lit street, and almost immediately the car came to a standstill in front of a tall, gloomy-looking house. Monsieur Simon descended leisurely and assisted his companion to the pavement.

"We are arrived," he remarked, looking over his shoulder at the younger man. "Follow us, please." Monsieur Simon rang and almost immediately the door was opened from inside. They were now in a very dark courtyard, with another door fronting them. After a moment or two's delay this one also swung back and hey passed into the passage of the house. By the light of an oil lamp which hung down from the ceiling, D'Argminac could see that they seemed to have penetrated into some low-class apartment house. The floor was of uncovered stone, the walls were stained with damp. During the moment that they stood together in the passage, two or three men of villainous aspect came through a door from the interior and swaggered out. A girl in tawdry clothes, smoking a cigarette and shouting the words of a popular song, brushed past them and out into the street. Monsieur Simon drew a key from his pocket and unlocked the door at his right hand. They passed into a small apartment which differed from the rest of the place in that it was apparently clean and moderately well furnished. In the far corner was a desk, at which Monsieur Simon seated himself. He whispered for a moment to Mademoiselle Josephine, who nodded and passed out. Then he rang the bell.

"You had better take a seat by my side," he said to the boy. "It would be really easier for you to come to an understanding of things by listening to me than if I attempt to explain."

D'Argminac did as he was bidden, asking: "One smokes?"

"One smokes always," Monsieur Simon replied, pushing him some matches.

Then the door was opened. A short, pallid-faced Frenchman came hurrying in, carrying a sheaf of papers. He bowed respectfully to Monsieur Simon, but came to an abrupt standstill when he saw a stranger.

"A friend, Briane," said Monsieur Simon. "He is with us for an hour or two, at any rate. What is there to be done?"

"A brave choice, Monsieur," the man answered. "Pierre has just come in with two most excellent reports. Monsieur perhaps remembers the man Jean Henneguy, the thread manufacturer in the Porte St. Martin?"

"He has three black crosses against his name, I believe," Monsieur Simon remarked.

"He deserves more," the newcomer insisted. "We have indeed a long account against him. His workpeople are shockingly underpaid, his wife he illtreats, he gives nothing to the poor, and he binds his customers to him by a system of usury."

"I remember the fellow," Monsieur Simon declared. "There is no one better for our purpose if the circumstances are propitious."

"He visits to-night," Briane said, glancing at the sheaf of papers in his hand, "at number 121, Rue d'Enghin. It is arranged that he shall leave there at four o'clock. Mademoiselle Marquerite has promised that he shall be punctual. Here are some further particulars concerning the man, if you care to look them through."

Monsieur Simon nodded and glanced down a sheet of foolscap. "It is decided, Briane," he announced. "This one affair will be enough for this time. Bring some clothes here for my young friend."

Briane glanced at D'Argminac and nodded. "But certainly, Monsieur," he replied, hastily quitting the room.

Monsieur Simon rose to his feet. D'Argminac had promised himself that he would ask no questions, but it was difficult.

"We are going into a quarter of the city," the former remarked drily, "where our present attire would be a trifle conspicuous. My good friend Briane, the little stout gentleman who has just gone out, will bring you some clothes. I myself am about to change. In ten minutes I shall return. You are still anxious to go on?"

"By all means," answered D'Argminac. "In fact, I am becoming quite interested. I await you here, then?"

"If you please," Monsieur Simon replied.

Briane came in and deposited a bundle upon a chair. Faithful to his resolve, D'Argminac asked no questions. When he saw what was laid out for him, however, he stared. One by one he held up the garments in disgust. A worn black jacket with many buttons, black trousers, frayed and stained, no collar, but a red handkerchief, and a peaked cap.

"The costume of an apache," he exclaimed to himself. He was alone now and slowly he commenced to disrobe himself and don this unaccustomed attire. Notwithstanding his genuine desire for adventure, his fingers trembled as he fastened the last button of his coat and glanced at himself in the cracked mirror. Nothing was left of the elegant young man of fashion. The change of clothes, indeed, had a curious effect upon him; his face seemed to have become more vicious, he was aware that he looked the part for which he was cast.

The door opened. It was Mademoiselle who entered. D'Argminac gave a little start at the sight of her. She, too, was dressed in black. Her gown was ragged, her bodice torn, her head bare. She laughed at his wondering gaze.

"It is a rapid transformation, is it not, Monsieur?" she demanded. "An hour ago we were of the great world. At this moment we are people of the street. You see, we go where the other things are not understood."

She walked to the mantelpiece and, taking up a cigarette, lit it. Then from a drawer she took out a long thin knife, tested its edge with her finger, and thrust it into the bosom of her gown. Afterwards she selected another one and passed it across to him. He accepted it without a word.

"Thank you," he said. "Do I do anything particular with this?"

"Use it if you are attacked," she answered drily. "The best advice I can give you is to show it often but to use it never."

Monsieur Simon appeared at the door. His costume was very nearly the same as D'Argminac's except that he wore a shabby overcoat.

"Come," he said.

They passed out into the courtyard. The door was slowly opened before them and they stepped into the street. A man slunk by them in the doorway, muttering a word as he passed. Monsieur Simon nodded. They entered the automobile. Monsieur Simon whispered an address to the driver and they tore away.

"Do you wish to ask any questions?" he inquired of the younger man.

"I am not in the least curious," said D'Argminac, with a yawn. "If there is anything you think I ought to know, pray tell me. Otherwise, I am well content to wait for this excitement which you have promised me. It is rather a long time coming."

Monsieur Simon smiled. "Perhaps you are right," he remarked. "Just stick to us, then, and act as seems reasonable."

Their ride this time was a short one. When it terminated they were still in an unsavory and unfamiliar part of the city. The automobile stopped at the corner of a street. The other two followed Monsieur Simon on to the pavement, and as soon as they had descended the car at once glided off.

"This way," Monsieur Simon directed. "Keep close to us, my young friend. The brethren of our craft around here are apt to be curious."

They passed a café being swept out by a yawning waiter; another, from behind the closed door of which came the sound of music. Then a row of silent, empty-looking houses. Close to the end of the street they slackened their pace. Four o'clock struck.

"Within five minutes," Monsieur Simon remarked, "a man will come out from that house opposite. When he comes, Mademoiselle will leave us. As for you, you had better follow me closely."

D'Argminac nodded. Almost at that moment the door of a house on the opposite side of the way was opened, and a man came down the steps and turned into the street. Mademoiselle Josephine crossed the road, laughing softly. The man stopped to watch her. She was wonderfully graceful even in her ragged clothes. She seemed about to pass him, but paused to shout a greeting. He caught a glimpse of her face in the gaslight and hurried after her. Monsieur Simon, making a slight detour, crossed the road a little higher up. Mademoiselle and the man were talking now, on the edge of the pavement. Monsieur Simon crept up behind and D'Argminac began to feel that it was coming. His heart was certainly beating faster. What was it that was going to happen! He caught a glimpse of Mademoiselle's face, white and provocative. The man, a coarse, burly brute, was leaning towards her. Monsieur Simon glanced up and down the street. Suddenly he crept up from behind and his arms went around the man's neck like a flash. Almost as he held him, the girl pushed something into his mouth. The man struggled in vain now to speak or cry out. Again the girl leaned toward him, and squirted something from a little bottle into his nostrils. Even from where he stood D'Argminac was conscious of a pungent, extraordinary odor.

"It is enough," Monsieur Simon said calmly. "Help me to support him, if you please," he added to D'Argminac. "Now into the car with him."

Silently and without warning the automobile had pulled up by the side of the pavement. Monsieur Simon, with an effort of marvelous strength, lifted the man in. The other two followed and the car was off once more. Monsieur Simon, with Mademoiselle Josephine and D'Argminac, occupied the front seat. The man whom they had garroted lay on the floor by their feet. His eyes were open and he was breathing heavily, but he seemed barely conscious.

"That is the man," Monsieur Simon remarked, looking down upon him—"Jean Henneguy. There is something in physiognomy, without a doubt. One cannot but remark upon the brutality of that face. Look with me, Josephine. The eyes are too close together, the forehead is too low, the nose is small and insignificant, the mouth is sensual. Can you see a single redeeming feature there? What do you say, Monsieur d'Argminac?"

D'Argminac, who was trembling slightly, did his best to speak with his customary drawl. "An ugly and repulsive person," he declared. "I never saw a worse face."

"I am afraid," said Monsieur Simon, "that his biographer has flattered his career rather than otherwise. It is a pity that such a man should be allowed to live. An absolutely humanitarian government would dispose of him in the quickest way. The world is too full of sentiment nowadays. You agree with me, I am sure, Monsieur d'Argminac?"

"Naturally," D'Argminac replied. "This man is no better than the insects on which we tread because the sight of them offends us."

Monsieur Simon nodded. "Sound, my young friend," he declared, "perfectly sound. Dear me, how fast we travel to-night! Once more we are arrived." To D'Argminac's surprise they were now in an entirely different quarter of Paris. The automobile had paused before the entrance to an old-fashioned white stone house. The door was opened and they passed into a small courtyard. Two servants, who seemed perfectly used to the situation, came swiftly out, picked up the body of the unconscious man, and carried him into the house. Monsieur Simon assisted Mademoiselle and motioned to D'Argminac to follow them.

"This," he explained, looking over his shoulder, "is our little hospital. If our friend who has gone in there before us has any money upon him, he will doubtless give us a small donation. We shall see."

Monsieur Simon led the way into a room the door of which was thrown open by a man-servant dressed in sombre black livery. D'Argminac could scarcely refrain from a little cry of surprise as he entered. The room was plainly but delightfully furnished. On a sideboard were various wines and liqueurs. Monsieur Simon opened a bottle of wine and filled three glasses.

"To the health of our distinguished visitor!" he remarked, bowing and raising his glass. "Mademoiselle and I drink your health, Eugène d'Argminac. Tell me, so far as we have gone at present, have we succeeded in amusing you?"

"The affair was interesting," D'Argminac admitted indifferently, "a trifle tame, though. One reads of such things without emotion every morning in the papers. There is nothing here really stimulating." Monsieur Simon smiled. "Ah, well," he said, "this is, perhaps, not one of our best nights, but it is not over yet! Ah, our friend recovers! Will you put on this, my friend?"

D'Argminac accepted his mask and adjusted it with a slight gesture of condescension. Monsieur Simon and Mademoiselle Josephine had already arranged theirs with deft swiftness. There was the sound of a voice close at hand, half terrified, half bullying. Some folding doors, which D'Argminac had not noticed, were suddenly rolled back from the further end of the apartment. Almost at the same time Monsieur Simon touched the knobs of the electric lights. The room was plunged into darkness.

THE smaller room, disclosed by the rolling back of the folding doors, was brilliantly illuminated, and from their darkened point of vantage seemed to D'Argminac to be something like the stage of a theatre. It was almost devoid of furniture, and the floor was covered with some sort of linoleum. There was a straight broad platform in the middle, on which the man whom they had brought there was sitting. By his side stood the person who was acting as jailer. A smaller man, with black, close-cropped hair, gold spectacles, and the air of a physician, came from the background. He leaned over to Monsieur Simon.

"The man is healthy," he announced. "Pulse and heart action are perfectly normal. He has two hundred and seventy francs, a gold watch, and some unimportant articles in his pocket."

Monsieur Simon sighed. "It is very little," he said. "Destroy everything except the money. Rather a bad case, I am afraid, doctor."

The other nodded. "I have heard of the fellow," he remarked. "He has a shocking reputation."

Their prisoner tried now to rise to his feet. His tie and collar were disarranged, his bulbous eyes were strained in the effort to see into the darkened room.

"Where am I?" he cried. "Is this a hospital? Has anything happened to me?"

Monsieur Simon spoke from the shadows. "Jean Henneguy," he said, "you are before the Court of St. Simon. Have you ever heard of it?"

"The Court of St. Simon," the man muttered angrily. "Is this some silly trick?"

Monsieur Simon sighed. "It is no trick," he said. "I will not explain our title, for I fancy that your reading, Jean Henneguy, has not extended to the ancient history of the world. Let me tell you simply that you are in the presence of those who amuse themselves in their spare moments by endeavoring to equate some of the miserable unfairnesses of life. It is not much that we can do, but here and there, Jean Henneguy, we take hold of a man as we have taken hold of you, whose life does not please us or his fellow men, and in our small way we do some trifling thing towards righting the balance."

"Is this a mad-house?" the man growled.

"No, no!" Monsieur Simon declared soothingly. "You are mistaken. It is precisely what I say. Now listen, and tell me if you recognize yourself. You are Jean Henneguy, of the Porte St. Martin. You are a manufacturer of thread, you employ forty young girls, and your wage bill is the lowest in the district. Your income is perhaps a hundred thousand francs. You tell your wife that it is not fifty. You have friends here and friends there on whom you squander money; your wife is a neglected and broken-spirited woman. You have never been known to spend a centime except for your own gratification, you have never been known to assist a human being or to perform a single act of kindness. Your life is an offence to the community. It is a peculiar offence to us, Jean Henneguy, that on the night when we were so fortunate as to bring you here, you should have been carrying upon your person only the sum of two hundred and seventy francs."

The man began to bluster. "But this is imbecility!" he exclaimed. "It is a robbers' den this, then. You want my money, eh?"

"A little more than your money, Jean Henneguy," Monsieur Simon continued calmly. "It is not enough. If you had been found to-night with ten thousand or even five thousand francs about you, we might have considered such an offering. But two hundred and seventy francs and a gold watch, Jean Henneguy, against the whole list of your misdeeds, is a trifling matter indeed!"

The man was beginning to get uneasy. He was straining his eyes in the effort to see the faces of the men with whom he talked.

"Well, well," he said, "who you are, and how it is you know anything of me or my life, I don't understand. What matter! Am I a prisoner? I wish to go. If I am to be robbed, I may as well put up with it. Keep my money and let me go."

"It is not enough, Jean Henneguy," Monsieur Simon repeated regretfully. "This is a court of justice, but, alas! our powers are limited. We cannot compel you to give more than you have upon you. Even here payment can be exacted from you only up to the pitch of unconsciousness. No, you will not meet with justice to-night, Jean Henneguy, although it is our privilege to deal out some slight measure of punishment."

The man's eyes began to roll. "What do you mean?" he growled.

"Give him twelve lashes," Monsieur Simon ordered—"twenty if he shouts like that. The gag!"

The man's yell was abruptly stifled. The folding doors were slowly returning to their original place. Monsieur Simon strolled towards the switch of the electric lights and pressed it with his forefinger.

"You see, after all, my dear D'Argminac," he remarked, passing his cigarette case to the younger man, "that we are moralists. To judge from our costumes and our methods, people might, perhaps, call us hard names. That would be foolish, for we do not deserve them. Dear me, what a babel! I am afraid that there is still another sin to be charged up to our friend. I am really afraid that he is a coward."

From the inner room came a succession of half-stifled cries, pathetic sobbing, as though some animal were caught in a trap. The soft swish of a whip cut through the air, beating time moment for moment with those hysterical murmurs of agony. D'Argminac felt suddenly sick.

"You would like to come behind the scenes with me, no doubt, and see this creature punished?" Monsieur Simon suggested. "I am afraid he is but a poor subject. He cries all the time like a rabbit."

D'Argminac set his teeth. "Cannot we see from here?" he asked.

"Just as you like," Monsieur Simon replied carelessly. "I thought that perhaps you would prefer closer quarters."

He readjusted his mask, turned out the lights, touched a bell, and the folding doors once more rolled back. Henneguy was lying with his face downward, writhing upon the platform. They had drawn a sheet over him. He seemed still to be sobbing in a half-choked manner.

"Take away his gag," Monsieur Simon ordered. "Let us hear if he has anything to say."

They removed it and the sheet. The man's face was horrible. The perspiration was standing in great globules all over his forehead, a dull streak of color glowed across his livid cheeks.

"Pardon!" he begged. "Pardon, Messieurs! I will pay. I will give five hundred francs—five hundred francs—no, a thousand—if you will put me in a cab and send me home. I will ask no questions, I swear that I will do nothing. I will send the money wherever you will. I am not strong. I cannot stand this. I shall die—oh, my God, I shall die!"

Monsieur Simon listened with immovable face. The girl by his side laughed openly, her white teeth flashing in the dim light.

"It is a pity," Monsieur Simon remarked to D'Argminac, "that to-night we should have had to deal with a coward. Often we have men who, whatever their faults may be, possess courage. Not so this poor lump of flesh! How many lashes did we say?"

"Twelve, sir," answered the man who stood by the side of the platform.

"And how many has he had?"

"Eight, sir."

"You hear?" continued Monsieur Simon, addressing the man who lay writhing upon the platform. "You have four more lashes to receive, Jean Henneguy. Think of that, and remember that you are being punished now for the life you have led. Remember that a single good action committed by you during the last twelve years would have meant a lash the less. If one could learn a single favorable thing concerning you and your pig-like existence, you should be spared, but there has been nothing. You have eaten and drunk, you have fed out of the trough, you have satisfied every coarse appetite which your nature has begotten. You have shown kindness to none. You have not once stretched out your hand to help a poorer brother. It is an inadequate payment that you make to-night, but it is something. Proceed."

The man who was armed with the whip stepped forward. His victim struggled violently.

"Did I say a thousand francs?" he shrieked. "I will give five thousand to any hospital, to any charitable work you will. I will not say that I have been robbed—I swear it. Monsieur—you there whom I cannot see—listen, I pray you! Have mercy! For Heaven's sake, have mercy!"

Monsieur Simon seemed as though he had not heard a word. Turning to D'Argminac, "Perhaps," he suggested, "it would amuse you to wield for a moment the whip? If so, do not hesitate to step upon the platform. No? Then continue, Pierre."

The whip sang through the air. The gag was back in its place, but the man's frantic, half-stifled shriek was like the death cry of a dumb animal. D'Argminac turned and fled into the back portion of the room. Monsieur Simon, with a smile, followed him. The folding doors were closed, the lights shone once more out in the room.

"So, my young friend," he remarked pleasantly, "we have, I trust, succeeded. We have at least shaken that expression of weariness from your face. Once more you look as though life held things which counted. Pardon me, you will drink some wine?"

D'Argminac accepted the glass with shaking fingers. His face was livid, he was feeling horribly sick. "Can't we—can't I get away?" he begged.

"By all means," Monsieur Simon assented. "If it would amuse you to return here afterwards—"

"No!" D'Argminac interrupted. "No, I should like to go home at once! It doesn't matter about my clothes." "As you will," Monsieur Simon answered. "Your clothes shall be returned to your rooms. You will, perhaps, give us the pleasure of your company again before long. Mademoiselle my sister and I are always enchanted."

"I thank you," muttered D'Argminac.

They stood now upon the doorstep. The automobile was waiting. They all three entered.

"You are leaving him here?" D'Argminac whispered.

"But certainly," replied Monsieur Simon. "This is all part of a scheme, my young friend, a perfectly organized scheme. My people know exactly what to do with him."

"But won't he—don't they go to the police afterwards?" D'Argminac asked.

Monsieur Simon shrugged his shoulders. "To tell you the truth, some of them do, but their stories sound strangely, you know. They are drugged in a peculiar manner when they come, and we give them just a little more of the drug when they leave, and they are found practically where we picked them up, robbed, and, to all appearance, recovering from a drunken slumber. Their story, if they venture to tell it, doesn't sound very credible, and for the rest, I will bet you a hundred louis, if you will, Monsieur d'Argminac, that you shall set out tomorrow from your rooms and you shall search all Paris and you will find no trace of the house from which we started, or the hospital we have just left."

"But it is a risk, surely it is a risk!" exclaimed the young man. "There is always a chance that you might be recognized and discovered."

Monsieur Simon sighed. "You talk like a child," he murmured softly. "We came out to-night to try and stir your pulses a little. Is anything in life which creates emotion done without risk? It is all a matter of degree. You risk your life every time you cross the Boulevard. Yes, we chance something, of course, but not so much as you think. The Court of St. Simon is one of the jokes of the magistrates' rooms here. No one believes in it, of course. In a moment or two, Monsieur Eugène, we shall put you down at the corner of the Rue Galilee, and as a matter of form, I must request that your little adventure of to-night remains a secret."

"You trust me, then?"

Monsieur Simon smiled. "There was one who tried to talk," he remarked, "a year ago. He was brought to the hospital and he did not get off quite so lightly as our friend Jean Henneguy, who in a very short time will be found lying, badly beaten and robbed but alive, in the gutter of the street where we found him."

"Will you bring me with you again?" the boy asked. "You mean it?" Monsieur Simon replied.

"I mean it," D'Argminac asserted, though his voice, even when he had asked the question, trembled.

"We will see," Monsieur Simon answered. "We may come across one another again. Let it depend upon the humor we are in."

"May I know your name?" the young man asked. "They call you Monsieur Simon, but one knows—"

"Monsieur Simon is the name by which I am known at night. It is the name which belongs to our acquaintance. Descend here, if you please, Monsieur, and au revoir!"

Eugène d'Argminac was left standing at the comer of his street in the cool dawn-light. The automobile was already rushing on towards the Champs Elysées. Even here, through the stillness of the early morning, he fancied for a moment that he could hear the horrible cry of the beaten man. With a shiver he hurried into his apartments.

VALENTIN SIMON, Vicomte de Souspennier, leaned back in his chair upon the worn gray terrace of his chateau in the valley of the Seine, his coffee untasted, a cigarette burning idly between his fingers. His eyes were fixed upon that broad ribbon of white road which stretched from the horizon to the village beneath, straight as the hand of man could build it. It was the road from Paris, and a visitor was even then on his way to the chateau.

The chateau itself was old and rugged, the splendid remains of a fourteenth century fortress. Its interior was a veritable study in contrasts. Some of the rooms seemed to have been left untouched for hundreds of years. Others—the more habitable portion—showed with absolute ruthlessness the modernizing hand of science. On a corner of the round table where Valentin had recently lunched was a telephone instrument, brought out from the room beyond. Even as he watched he raised the receiver to his ear.

"It is the station-master at Neuilly?" he asked. "The mid-day express from Paris, it has arrived? Yes? My car has left, then. Ten minutes ago? Many thanks." He replaced the instrument and looked once more along the road. In his quiet country clothes he had certainly lost none of the distinction which had attracted the favorable notice of so well known a dandy as Eugène d'Argminac. Without a doubt, Valentin, Vicomte de Souspennier, was good to look upon. In his English-made tweeds his long, lithe frame, sinewy, without an ounce of fat, his easy carriage, his slim yet powerful shoulders, were even more noticeable. His face would have been colorless but for a slight tinge of brown; his clear eyes, his glossy brown hair, were trustworthy indices of his perfect physical condition. He looked, indeed, as much at home here, amidst his country surroundings, as in the Abbaye.

Soon a little cloud of dust in the road attracted his attention. He touched a bell by his side. "Monsieur Briane arrives," he told the footman who answered it. "See that fresh coffee be sent up, and liqueurs."

The man withdrew. The car, being driven at a great pace, was soon ascending the tortuous way leading from the village to the chateau, which was literally built upon a rock. Every now and then Valentin caught sight of it with its solitary occupant, flashing through an opening in the trees, climbing up the steep, almost precipitous drive.

Soon it came to a standstill below and Valentin leaned forward.

"Welcome, my friend Briane!" he exclaimed. "Come this way, up the steps. So! The man will take your coat. You are sure that you have lunched?"

"A thousand thanks, Monsieur, I lunched upon the train," the man replied. "With your permission!"

He sank into the seat indicated by Valentin. He, at least, fitted strangely with his surroundings. Everything in his face and general appearance seemed to denote the liver by night. His cheeks were pale and thin, his eyes deep sunken, his bony fingers stained with cigarette smoke. His clothes were Parisian, and one realized that he had with difficulty refrained from the silk hat. He helped himself a little eagerly to brandy and lit a cigarette.

"It is pleasant of you, my dear Briane, to pay me a visit in my country solitude," Valentin remarked, "but I very much fear that it is no ordinary business which has brought you from Paris so early in the day."

"It is no ordinary business, Monsieur," Briane admitted, nodding his head vigorously, "no ordinary business, indeed. What is it that I said to Mademoiselle Josephine only one week ago to-night? 'Monsieur,' I said, 'must do as he thinks best, but he acts too much upon the whim of a moment. It is enough for him that he wishes it and he brings to an assignation, whose secrecy is the very breath of our lives, the veriest strangers. The whim assails him and he invites. What is it that he does by this? He risks everything—everything!'"

Briane was puffing vigorously at his cigarette. His eyes were bright, his tone had been almost hysterical. Valentin regarded his companion gravely. "My indiscretions," he declared with a sigh, "are part of myself. I cannot help them, my dear friend. If I were to promise to be more careful in the future, it would be of no avail. The same thing would happen again, without a doubt. Now tell me, what is it that I have done?"

"A week ago to-night," Briane exclaimed, "you brought to the Rue Druot and to the hospital a young man whose acquaintance you made at the Abbaye only a few moments before. The young man you presented to me—it was your friend, it was enough! By chance, the very next day I met with him, late in the afternoon, at a little bar where I take my aperitif, close to the Elysées Palace. We drank together and we talked."

"Well, I hope you got on well with him, Briane?"

"He pleased me," admitted Briane, "in a way he pleased me. He seemed to me to possess something of the modern spirit. I sympathized with him. Notwithstanding his youth, and a certain immaturity of thought which one could not fail to observe, he was still superior in many ways to those others of his age whom one meets. We spoke together of what he had seen the night before."

Valentin smiled. "I should really like to know," he murmured, "exactly what that young man's impressions were."

"I can perhaps inform you," Briane continued drily. "He found the evening exceedingly interesting, but when he came to examine his sensations afterwards, he was conscious of a certain amount of disappointment. There was, he observed, nothing criminal in what had taken place; nothing, to use his own words, which was unmoral. What was done was deserved. It was, after all, only the inexorable law of justice."

"Dear me!" remarked Valentin. "Was this his point of view or yours?"

"We were, perhaps, agreed," confessed Briane, "on this matter. You know very well, Monsieur, that there are those of us whose aid you frequently seek, and under whose protection, indeed, you carry out your enterprises, who go further than you would dare."

Valentin knocked the ash from his cigarette. "Come," he said, "'dare' isn't quite the right word. I know that some of you in the Rue Druot, some of those who use the place, I mean, are criminals. I have not the slightest objection to making use of them where it is necessary. I have even found a certain thrill of interest from association with them. My direct connection with them, however, ceases at that point."

Briane spread out his hands. "'Dare' is not the word I should have used," he admitted. "Monsieur le Vicomte has reason in what he says. Still, to revert to our young friend Monsieur d'Argminac. Not unnaturally, you will say, his point of view was not without its appeal to me. He was a protegé of yours—it was enough! The night before last he came to the Rue Druot at my invitation."

"The night before last," Valentin said softly, "was the night of the outrage in the Place Ceinture." Briane nodded and glanced for a moment around.

"Monsieur le Vicomte," he whispered, "your young friend D'Argminac was present. It was I who arranged it."

There was a short silence. Valentin's face had become a shade sterner. "Why do you come to tell me this?" he asked coldly.

"It is because of that young imbecile," Briane continued. "All went well, but at the critical moment fear paralyzed him. He could not retreat, he could not even reach his automobile."

"You don't mean to say that he was arrested?" Valentin demanded.

"He was not arrested," answered Briane, "but when the gendarmes came he was held as a passer-by, asked many questions, none of which he seems to have been able to answer through sheer terror, and he will be called as a witness to-morrow in the court. This is what comes of taking strangers into our secrets!"

"My dear Briane," Valentin objected, "I think that you are a little unreasonable. I am quite willing to take the responsibility for bringing the boy to the Rue Druot and on to the hospital, but it seems to me that this is a very different thing which you have done. You know very well that I have no sympathy with such deeds as the deed of the night before last. If you choose to indulge in such and to invite your own audience, I take no responsibility. Why have you come to me?"

"Because," Briane replied, "it is my firm conviction that the young man means to tell everything, not only the events of the night before last, but of his meeting with you, his introduction to me, the Rue Druot and the hospital."

Valentin smoked silently for a moment. "Well," he finally said, "my opinion of you, Briane—my honest opinion—is that you are a consummate ass."

The man's eyes flashed angrily, but he said nothing.

"Having relieved my mind to that extent," Valentin continued, "may I ask what you think I can do in the matter?"

"You must see him," Briane declared. "To me his doors are closed. I have sent my name up in vain. He is confined to his room, his servants say, suffering from shock. Nevertheless, one of them is to be bought. I can have you admitted."

"But what do you gain by that?" asked Valentin. "What can I do even if I see him?"

Briane leaned forward in his chair. The flesh seemed drawn tightly over his cheekbones; underneath there were hollows. His eyes were dry and bright. "Monsieur le Vicomte," he said, "you have gifts, great gifts. You do not fully make use of them, but that is your own affair. You would say to that, perhaps, as you say to so many things, that it is not worth while. Still, you have a tongue, you have a manner, you have force, you have the magnetic persuasion which we lesser mortals lack. If you lay your finger upon his lips, he will not speak."

Valentin leaned back in his chair. He looked over the smooth, sunny landscape, with its tall rows of elm trees, its river winding a way through the meadow-land—a broad thoroughfare of silver. He looked into the mists which rose faintly in the blue distance. He was a fool to have spoken to the boy, a fool to have taken him to the Rue Druot! The momentary attraction which had induced his interest had already faded away, but the regret remained. For some reason or other he felt, even at that moment, that for the rest of his life he would repent that careless invitation.

"I will go," he announced, throwing away his cigarette. "All the same, it is a bore."

EUGENE D'ARGMINAC had certainly succeeded in his quest for some new sensation, although the result did not appear to be altogether satisfactory. Wrapped in a rose-colored dressing-gown, he lay upon a deep sofa in his luxurious bedroom, with a pile of novels and newspapers beside him, a basket of peaches, a bottle of absinthe, and a half-empty box of cigarettes. The room was full of strange odors, burning essences, for which he seemed to have a special fondness, and every aperture through which fresh air could enter was closed. Nevertheless, although his immediate surroundings were exactly those most dear to him, it was very clear that he was far from content. As a matter of fact, he was almost prostrated with fear. At the slightest noise he twitched and started nervously. A footstep alarmed him.

"Gustave!" he exclaimed. "Gustave, how is it that you tread so loudly! Where are your slippers, you dolt, you clumsy idiot!"

There was no reply. D'Argminac turned his head and was suddenly speechless. This was not the pale, smooth-faced Gustave who came so leisurely across the room towards him. The boy clutched at the side of his couch. He could scarcely believe his eyes. It was the wonderful stranger of a few nights ago, Monsieur Simon, the man who had first turned the key in the door which had led into this land of strange terrors and delights!

"Monsieur Simon!" he gasped. "You!"

Valentin laid down his hat and stick. "Yes!" he assented shortly. "I had a visit this morning from our friend Briane. I thought that I had better come and see you."

D'Argminac shrank back upon his couch. His face was livid, his forehead damp, the lines under his eyes were almost purple. "You have seen Monsieur Briane?" he faltered. "He has told you everything?"

"He has told me everything," Valentin repeated. "It seems that you have gone a little further, my young friend, in your quest."

"It was Monsieur Briane," the boy muttered. Valentin frowned. "Briane gave you what you asked for," he reminded him sharply. "It is generally a mistake to give people what they ask for."

The boy's lips were slowly parted. "Monsieur Simon," he said hoarsely, "it was horrible! I saw the black figure come up behind, noiseless, creeping like an animal, holding on to the wall, bent double. And then the spring! I saw the knife flash, I heard that man's cry and the drip, drip, drip upon the pavement!"

He began to sob. Valentin looked at him as one might look upon some deformed object.

"Robert—the man who did it," he went on—"I had spoken to him only a minute before—I had taken a petit verre with him. He wiped his knife upon the tunic of the gendarme and leered at me across the street. Then he turned and ran, and all the others ran, and I—oh, my God, I couldn't!" the boy wound up.

Valentin sighed. "This is what comes of taking a nerveless parcel of insignificant humanity like you and treating it as though it were really flesh and blood," he murmured. "You had a beastly unwholesome craving to see crime. You've seen it and it has been too much for you. They tell me that there is some danger of your betraying those who gave you what you asked for."

"The man may die!" D'Argminac faltered.

"Die!" Valentin repeated contemptuously. "You knew quite well that life and death are phases only among these people. You knew that you were going to see an act of revenge—it may even have been justice. It is not your concern. It was bloodshed itself which you desired to see. You were gratified and now you whine like a sentimental puppy. Remember this. No one has made you the judge of my friend Briane or le beau Robert, or any of these others, any more than you have been made the guardian angel of the man at whom they struck. So far as you are concerned, these men have done no ill."

D'Argminac's fingers twitched as they played with the girdle of his dressing-gown. "I don't care what they've done," he muttered. "It isn't that."

Valentin shrugged his shoulders slightly. Then: "The object of my visit," he said, "is to impress this upon you, Eugène d'Argminac. If you are summoned before the magistrate to-morrow, you know nothing about that happening, about what went before or what came afterwards. There is no one concerned in it whom you can identify or whom you can remember to have seen before." D'Argminac listened intently. "No one I can identify, no one whom I can remember to have seen before," he repeated, after a pause. "I will try. But, Monsieur Simon, I am afraid. I suffer terribly from nerves. I do not like to go into any crowded place. I do not like to go into a court of justice. If I stand there, I shall scream. They bully one so, these lawyers. They will do what they will with me. I am terrified lest they should make me answer just as they please. This morning I am ill, Monsieur Simon, indeed I am ill."

He threw himself back upon the sofa with a groan.

Valentin looked around the room with an air of intense disgust.

"Of course you are ill, or think you are," he replied, "breathing an atmosphere like this! Why don't you send for a doctor to prescribe for you, open all the windows, and let in some fresh air?"

D'Argminac shook his head. "I catch cold so easily," he protested. "I like my rooms always warm. As for the doctor, I have sent for him many times, but he does me no good. I have my draught here and some absinthe. Monsieur Simon," he continued pitifully, "it is not that I wish to bring evil upon Monsieur Briane or the man—the man whom they call Robert, but in the court of justice I am helpless. I cannot breathe in a crowd—I shall faint, and when I recover I shall be so weak that I may say anything."

Valentin rose to his feet. His face was dark and menacing. He gripped the other'a shoulders and shook him. D'Argminac began to sob with terror.

"Listen," Valentin said, "I have done my errand. Before I go, let me assure you of this, though. The magistrate's room may have its fears for you, but there are more terrible things in the world. The friends of Monsieur Briane and le beau Robert number something like five thousand in this city, all bound together for purposes of self-protection. If by any single word you give away your knowledge of the affair that night, or mention our little excursion of the other evening, you will need to have exactly five thousand lives to avoid having your throat cut within a month."

"The police would protect me!" the boy muttered.

Valentin laughed scornfully. "The police! The poor fellow whom you saw killed in the Place Ceinture represented the police. They are none too anxious to have anything to do with Monsieur Briane's friends—let me tell you that. They know all about the house you visited with Mademoiselle and with me, but I don't think you will find them making any raids in that direction."

"I could leave the country!"

Valentin sighed. "Really," he said, "I gave you credit for more intelligence. I shall waste no more time upon you, but look me in the eyes, listen to what I am saying to you. Your cross-examination by the magistrate tomorrow will be only nominal. You saw nothing except a dark form steal up behind the gendarme, and you heard a cry. You were paralyzed with terror and you could not speak or move. You did not see the murderer's face. You were there because beyond the Place Ceinture there is a café which you had heard spoken of as a curiosity and worth a visit. Would you like me to repeat it?"

"I can remember it," the boy faltered. "But the magistrate will ask me more questions."

"I think not," Valentin replied. "Between you and me, I think that they are very well content to know as little as possible. Another arrest would mean more reprisals. I think you will find them willing to let things lie. Look at me. You believe what I say? You will obey?"

D'Argminac gazed up with fascinated eyes at the man who was standing over him. "I will do my best," he promised weakly.

Valentin moved away. He took up his hat and stick. He returned, however, to his former position and stood looking into the boy's face. There was a touch there of something feminine, something which seemed to denote an absence of virility, a superabundance of sensitiveness, which, after all, was perhaps a matter of inheritance. Valentin's expression softened; his tone, when he spoke, was kinder.

"My young friend," he said, "for my part I will say this. I regret exceedingly that a moment's idle curiosity should have induced me to make your acquaintance the other night in the Abbaye. Believe me, you are not suited for this life. Take my advice and chuck it all. Go back to England and try living in the open air for a few months. Here you are, after all, only affecting to be weary of a life over whose threshold you have not yet passed. How old are you?"

"Twenty-two," D'Argminac replied.

"Twenty-two!" Valentin repeated. "Haven't you a sister or a mother or some one who'll look after you?" "I have a sister," D'Argminac replied.

"Then go back to her," said Valentin, taking up his hat. "Make up your mind to try my prescription. Three months in England—in the country, mind—and try and fall in love with some nice girl. If you've any manhood in you, that ought to bring it out. And while you are here, break open your windows and let in the fresh air. Stop burning these beastly perfumes, take a cold bath now and go for a brisk walk in the Bois. Do you hear?"

"Yes, I hear," D'Argminac answered. "I'll—I'll try."

Valentin nodded not unkindly and turned away.

"Above all," he said, as he looked back from the door, "remember those few words of warning of mine."

VALENTIN was dining with Mademoiselle Josephine a few nights later, at a restaurant in the Bois de Boulogne, a miniature palace of glass and gilt and flowers.

"To-morrow," he announced towards the end of the meal, "I go to England."

She started. Her black eyes were full of concern.

"But, Monsieur," she exclaimed, "it is sudden, this! To England?"

Valentin assented. "For several days," he said, "I have felt inclined to take a change. To tell you the truth, Josephine, the affair of the Place Ceinture and that wretched boy's connection with it disgusted me. There is something very sordid, after all, in the passions and weaknesses that go unbridled."

"So Monsieur goes to England," she murmured.

Valentin selected a cigarette with care and lit it. "I shall go," said he, "to a little village in Somersetshire where my sister lives. Such a queer place, Josephine! All the pasture-land is cut up into small fields with high hedges, and the roads are like the country lanes in Normandy—they lose themselves every moment. All the houses in the village are covered with creepers or honeysuckle or roses, and the peasants are not in the least like ours. They have plenty of money, and they do not save, save, save till they seem to grind the very blood and bone of their body into gold."

"I should like to go to England," she declared. Valentin shook his head. "You wouldn't care for it. As a matter of fact, you would dislike it exceedingly. It has occurred to me very often, Josephine, since you became my companion in these little adventures, that you are entirely ill-placed."

Her silky eyebrows drew close together. She looked at him jealously. "What do you mean? You want some one else?"

"Not I!" he assured her. "But you—well, when I found you, you certainly were what you professed to be—a gutter child—with no instincts in the world save the instincts of robbery and cupidity. No one had given you anything, every one had taken what they could. Naturally, therefore, you were one of those who seem born into the world to take from others."

Her face looked very white and set in the artificial light, her eyes were fixed steadfastly upon his. Her lips seemed to move, but she said nothing.

"When I found you," he continued, "you were recommended to me as an expert thief, a trustworthy guide to the backwaters of gutterdom. And withal, one who might be trusted by her friends. It was a true character, Josephine. You are indeed trustworthy."

She laughed, not in the least naturally, but still a laugh. "This amuses you?" she demanded.

"Naturally," he replied. "It is a resume of our relations. To-night it seems fitting that we should speak of them for a moment."

She leaned a little forward; something of the tigress zealously repressed flashed in her eyes. "You are going to leave me!" she cried.

He raised his eyebrows ever so slightly. She seemed to shrivel away back into her place.

"Ah, my God, what have I said!" she exclaimed. "I know very well that it is you who have the right to go when you will. There is nothing between us to hold."

"Our relations," he proceeded, looking at her thoughtfully, "have certainly been unique. The people who have seen us together in the cafés, in the restaurants, sometimes, even, on the race-course, can have had but one thought concerning us. It amuses me sometimes to reflect how wrong they are. And you, Josephine?"

She leaned back in her chair and laughed with all the abandon of the Frenchwoman. "A joke! A joke, indeed!"

"We have wandered from the subject, after all," he remarked. "We were speaking of you and your tendencies. I am not sure, even now, that you were not really meant to be the wife of some deserving young shopkeeper, to bring up his children, to sit with him on Sunday nights in the theatre, to eat your dinner four times a year in the country, to say your prayers, and live the estimable life."

"You mock me!" she muttered.

"No, I am in earnest."

There was a silence between them, a silence which lasted for several minutes. All the time she was watching him. Yes, there was a change in his face! There was something graver there, more thoughtful. Quick to study his every expression, she realized this, perhaps, more readily than any other person in the world could have done. A little of the sparkle had gone from his eyes, the curve of his lips lacked its accustomed cynicism. For a moment she wondered what it all could mean. He had the air of a man who has stopped to think. As she watched him, her heart sank.

"What your relations with my sex may have been before I came, Josephine," he went on, "I do not know. Since then I have always felt that you have respected a condition which I made. I have thought over this, Josephine. We make a jest of happiness in our wittier and saner moments, but after all it is there, and it is only the middle classes who really know how to seize it. Why shouldn't you start again, marry, live out the life which I honestly believe you were born for? Your dot is assured. I am not a rich man, but that is already deposited in your name."

"It is our farewell this, then," she gasped.

"Dear Josephine, yes," he replied, "chiefly," he added, lighting a cigarette, "for your sake. For myself, I am middle-aged, the fires of life have burned out in me, I have nothing to hope for."

She shook her head, but he continued, glancing away for a moment from her swimming eyes.

"You, on the other hand, have everything. When I found you, you called yourself a gutter brat. . I take some pride to myself that I have at least made you a striking and presentable figure in any society you care to frequent. Frankly, however, I do not consider the life which we have been leading, or rather that part of it which we have led together, advantageous for you. For me, whose life is finished, who must have amusement at any price, it is well enough, but you are young and I have noticed in you possibilities of other things. You have affections, I believe, although you do well to keep them so thoroughly under control. It is a great thing to have the power of caring. The next is to find some one worth caring about."

"Are you so sure that I have not found any one?" she murmured.

He shook his head. "It is my impression that you have not. You have spoken once or twice of an aunt who lives near Orleans, a worthy person, I should imagine. Take my advice, child. Go and pay her a visit, show her your bank-book. She will probably ask you to stay. There is no town in France where a young woman with your attractions, and a modest dowry, will not find eager suitors."

There was another short silence between them. The orchestra was playing some fragment of real harmony, and the room was hushed. The man's eyes passed over the heads of the people and rested on the waving green of the trees outside. The girl, too, turned her head away from the crowded restaurant with its brilliant groups of diners. There was a new pain at her heart, yet after all it was an old fear.

"It is for this, then," she said at last, "that you have asked me to dine with you to-night?"

"It is for this."

"Very well, pay your bill here and drive with me for a little time. Then I will tell you what I think."

They moved out into the perfumed twilight and took their places in the roomy automobile which presently came to the front.

"Tell the chauffeur," she begged, "to drive slowly in the Bois. One talks better so."

He nodded, and soon they were off. Bicycles with paper lanterns flitted about under the trees, merry groups of people sat before tables at the cheaper cafés, everywhere the air seemed full of music, of voices raised in laughter. Josephine sat looking steadfastly in front of her. For some few moments she was silent. Then she spoke.

"Listen," she began, "much of what you have said is true. I will tell you more. When you came, I was a wild cat. Perhaps no man wanted me. Certainly there was not one whose lips had ever touched mine. That is because I was ferocious, always in an evil temper, and I suppose my looks and my temperament went together. You wanted to make an experiment, and I suited your purpose. You established me in an apartment, you engaged masters to teach me, you sent me to the best dressmakers, you gave me jewels, gradually I became your companion. On the other hand, I suppose I was useful to you. I showed you the sort of life you wanted to know about, I took you where no one else would have dared to take you, you have learned from me as much of the underneath side of criminal life here as any one may know. You are tiring of it. Good God, I have been sick at heart of it since the first day I was able to live as a free woman! If your fancy for it has gone, so has mine long ago. I do not ask to be always your companion, I do not ask for your lips, for your love, even for the touch of your hands. Those things," she went on, leaning passionately towards him, "are for others worthier than I. Oh, I know that, for I have seen so much of you! I have seen the little things, I know that at heart you are what you profess to despise—a good man. I know that I am not worthy to touch you, and I know that there is nothing I have to hope for from you or from your affection. But if I could be—your servant—"

She stopped for a moment. The tears seemed to be in her throat as well as her eyes. She was shaking as though with cold. All the time she was watching him.

"I have had the most absurd ideas," she went on.

"If I could dress as a boy and go into whatever country you go, if I could be in the same town, even, I should expect so little. I want nothing more. Oh, you must understand!" she cried. "You must understand that you cut into my heart when you speak of a husband and children, and all those things. Do you suppose that one loves to order, even among my class? Do you suppose that after six months with you, even though your kisses have touched only my forehead, I could think of any other man?"

He moved a little in his seat. She clutched at his sleeve. "Do not be angry," she begged. "It is not that I expect anything more from you. I don't! I know that it would be useless. But I want to keep myself as I am, always, because I have known you. Is there anything wrong in that, anything to make you angry?"